Submitted:

16 October 2023

Posted:

18 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

- YouTube shorts

- Videos without voice

- Duplicate content

- Videos classified as mere advertisements.

Statistical analysis

Results

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusions

Funding Disclosure

Data Availability

References

- Stats, I.W. WORLD INTERNET USAGE AND POPULATION STATISTICS Available online:. Available online: https://internetworldstats.com/stats.htm (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Trend, I. Internet trend, SNS. Available online: http://www.internettrend.co.kr/trendForward.tsp (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Statista. Number of YouTube users worldwide from 2019 to 2028. Available online: https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1144088/youtube-users-in-the-world (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Viralblog.com. YouTube Statistics. Available online: http://www.viralblog.com/research-cases/youtube-statistics/ (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- WARC. Ad spend on YouTube forecast to reach $30.4bn in 2023, growth to accelerate next year. Available online: https://www.warc.com/content/paywall/article/warc-curated-datapoints/ad-spend-on-youtube-forecast-to-reach-304bn-in-2023-growth-to-accelerate-next-year/en-gb/151404? (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Madathil, K.C.; Rivera-Rodriguez, A.J.; Greenstein, J.S.; Gramopadhye, A.K. Healthcare information on YouTube: a systematic review. Health informatics journal 2015, 21, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, A.; Langille, M.; Hughes, S.; Rose, C.; Leddin, D.; Veldhuyzen van Zanten, S. A systematic review of patient inflammatory bowel disease information resources on the World Wide Web. Am J Gastroenterol 2007, 102, 2070–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.G.; Singh, S.; Singh, P.P. YouTube for information on rheumatoid arthritis--a wakeup call? J Rheumatol 2012, 39, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayranci, F.; Buyuk, S.K.; Kahveci, K. Are YouTube™ videos a reliable source of information about genioplasty? J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021, 122, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, E.; Campbell, C.; Grammatopoulos, E.; DiBiase, A.T.; Sherriff, M.; Cobourne, M.T. YouTube™ as an information resource for orthognathic surgery. J Orthod 2017, 44, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özdal Zincir, Ö.; Bozkurt, A.P.; Gaş, S. Potential Patient Education of YouTube Videos Related to Wisdom Tooth Surgical Removal. J Craniofac Surg 2019, 30, e481–e484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezici, Y.L.; Gediz, M.; Dindaroğlu, F. Is YouTube an adequate patient resource about orthodontic retention? A cross-sectional analysis of content and quality. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2022, 161, e72–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topsakal, K.G.; Duran, G.S.; Görgülü, S.; Eser Misir, S. Is YouTube(TM) an adequate source of oral hygiene education for orthodontic patients? Int J Dent Hyg 2022, 20, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.; Doong, J.; Trang, T.; Joo, S.; Chien, A.L. YouTube Videos on Botulinum Toxin A for Wrinkles: A Useful Resource for Patient Education. Dermatol Surg 2017, 43, 1466–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, M.N.; Karaca, S. Evaluating the accuracy and quality of the information in kyphosis videos shared on YouTube. Spine 2018, 43, E1334–E1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esen, E.; Aslan, M.; Sonbahar, B.Ç.; Kerimoğlu, R.S. YouTube English videos as a source of information on breast self-examination. Breast cancer research and treatment 2019, 173, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atci, A.G. Quality and reliability of the information on YouTube Videos about Botox injection on spasticity. Romanian Neurosurgery 2019, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M.A.; Akyol, H. Quality of information available on YouTube videos pertaining to thyroid cancer. Journal of Cancer Education 2020, 35, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charnock, D. The Dıscern Handbook. University of Oxford and The British Library. Radcliffe Medical Press Ltd Abingdon, Oxon Erişim adresi: http://www discern org uk/discern pdf, Erişim tarihi 1998, 27, 2022.

- Kunze, K.N.; Cohn, M.R.; Wakefield, C.; Hamati, F.; LaPrade, R.F.; Forsythe, B.; Yanke, A.B.; Chahla, J. YouTube as a source of information about the posterior cruciate ligament: a content-quality and reliability analysis. Arthroscopy, sports medicine, and rehabilitation 2019, 1, e109–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuru, T.; Erken, H.Y. Evaluation of the quality and reliability of YouTube videos on rotator cuff tears. Cureus 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silberg, W.M.; Lundberg, G.D.; Musacchio, R.A. Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the Internet: Caveant lector et viewor--Let the reader and viewer beware. Jama 1997, 277, 1244–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Assessment | Criteria | Description | Annotation | |

| Reliability | Creator credibility | Responsibility | Can you identify who created the site or who the representative or entity is that can take overall responsibility for the information the site provides? | 1. information about accountability should be available within one click from the home page. 2. make it easy to find liability on the homepage. 3. recognize not only individual names but also corporate names and organizations such as hospitals. 4. even if there is no specific mention of liability, it is acceptable if the name of the representative, organization, company, hospital, etc. can be identified. |

| Authorities | Is the entity operating the site a physician or health care provider, or a health care professional or organization as defined by applicable law? |

1. determine if the person or entity is a healthcare professional. If the liability is no, it is automatically no. If the organization is a business, mark yes if the primary purpose is to provide medical information or no if the primary purpose is to sell certain drugs, etc. |

||

| Openness | Is the contact information, such as an email address or phone number, for the website's creator or person in charge, displayed in a recognizable way? | 1. the contact information, such as email or phone number, must be available on the main page or in a single link. If it's more than one link, it's a no, even if you have contact information. | ||

| Clarity of sponsorship | Ads | If you have ads, are you mentioning that they're ads or labeling them in a way that clearly identifies them as such? |

1. check Yes if the ad is displayed as a separate box, pop-up, banner, etc. that can be easily identified. 2. judge only the main homepage of the site. |

|

| Information Delivery Formats | The creation date | Is the last updated date of the health information provided on the site clearly stated? |

1. a program that simply displays the current date or time is a "no". There must be a statement about when it was updated or modified |

|

| Purpose | Is there any mention of the site's introduction or purpose? |

1. it is acceptable to have only one of the following: an introduction to the site (including a description) or the purpose of the site. 2. a mention of it must be visible within one click from the homepage. |

||

| Complementarity | Is there any mention that the information provided on the site is meant to supplement, not replace, the care of a physician? | |||

| Format evaluation | Author credibility | Verify authorship | Does the webpage content list an author or creator? | 1. Give credit to the source or author of the article. If the article is taken from another source, it should be acknowledged with a citation. 2. Acknowledge that you have reviewed the material. 3. Even if the information is available elsewhere, it should only be recognized if it is clearly stated on the webpage. |

| Authority | Does the content of the webpage indicate that the author or reviewer of the webpage is a physician or other health care professional as defined by applicable law? | 1. It is also recognized if it was edited. 2. If the webpage specifically states the qualifications of the practitioner, doctor, etc. or creates a link to a webpage that displays the qualifications. |

||

| Openness | Does the content of the webpage list the author's phone number or email address? | 1. it is acceptable to list the contact information of the author as well as the person whose content is quoted and posted on the Internet. 2. except when a formal webmaster's email is provided that is not related to the author or the person quoted. 3. must be specified on the webpage. Bulletin boards are not recognized. |

||

| Information Delivery Formats | Creation date | Does the webpage content indicate the date the information was created/completed? | 1. must be displayed on that page, regardless of the homepage. 2. except when simply displaying the current time, date, etc. |

|

| Source | Do you provide sources or references in your webpage content? | 1. If there is a citation or reference anywhere in the text, it is recognized. 2. Even if only part of the text is marked with a citation, it is recognized. |

||

| Content evaluation | Scientific soundness | Scientific Soundness The overall content of the medical information you evaluated is consistent with the following? 1. well-established information found in medical textbooks or equivalent (5) 2. information that is not fully established orthodoxy but has sufficient clinical evidence (4) 3. some (less than 20% of the information) is controversial, but has some evidence (3) 4. substantial (>20% of the information), controversial, unsound information with weak evidence (2) 5. information that has been shown to be a medical error (1) 6. information that cannot be verified (0) |

||

| Harmfulness (1) | Is the content of the webpage harmful to the general public? | 1. focuses on harmfulness rather than content fault. | ||

| Harmfulness (2) | Is there anything on the webpage that explicitly encourages harmful behavior? | 2. recognize only when the content is deemed by the evaluator to be very clearly harmful. | ||

| Harmfulness (3) | Does the content of the webpage include anything that could lead to unnecessary health behaviors or waste? | 1. is a direct recommendation to purchase an item or service. 2. It is considered wasteful if it recommends a specific treatment that is not objective or not medically necessary at all. 3. Various factors can be listed in the process of treatment, so if any of them are present, it is judged as 'present'. |

||

| benefits | Is the webpage content informative overall? | |||

| balance | Does the webpage provide a balanced presentation of different treatment options? | 1. at least two treatments are presented, including at least one essential treatment (unless there is only one essential treatment), and if the essential treatment is ambiguous, at least one comparative explanation is acceptable. | ||

| Commercial | Is there any advertising in the content of the webpage? | look for content that is independent of formalities such as banners. | ||

| Benefits and risks of diagnosis and treatment | Are you explaining the pros and cons of a diagnosis or treatment method? | acknowledge the existence of a single pro or con statement. |

| Score | Global Score Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Poor quality, poor flow of the video, most information missing, not helpful for patients |

| 2 | Generally poor quality and poor flow, some information listed but many important topics with limited use to patients |

| 3 | Moderate quality, suboptimal flow, some important information is adequately discussed, but other information is poorly discussed, so somewhat useful for patients |

| 4 | Good quality, generally good flow, most relevant information is covered, is useful for patients |

| 5 | Excellent quality and flow, very useful for patients |

| Korean letters | Pronunciation | Translation to English |

|---|---|---|

| 안검하수 수술 | Angeomhasu susul | Ptosis surgery |

| 안검하수 병원 | Angeomhasu byeongwon | Ptosis hospital |

| 안검하수 진단 | Angeomhasu jindan | Ptosis diagnosis |

| 눈처짐 수술 | Nuncheojim susul | Droopy eyelid surgery |

| 눈처짐 병원 | Nuncheojim byeongwon | Droopy eyelid hospital |

| 눈처짐 진단 | Nuncheojim jindan | Droopy eyelid diagnosis |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Views | 54 | 1040804 | 79019.5 (191360.8) |

| Length (second) | 88 | 3074 | 437.5 (376.94) |

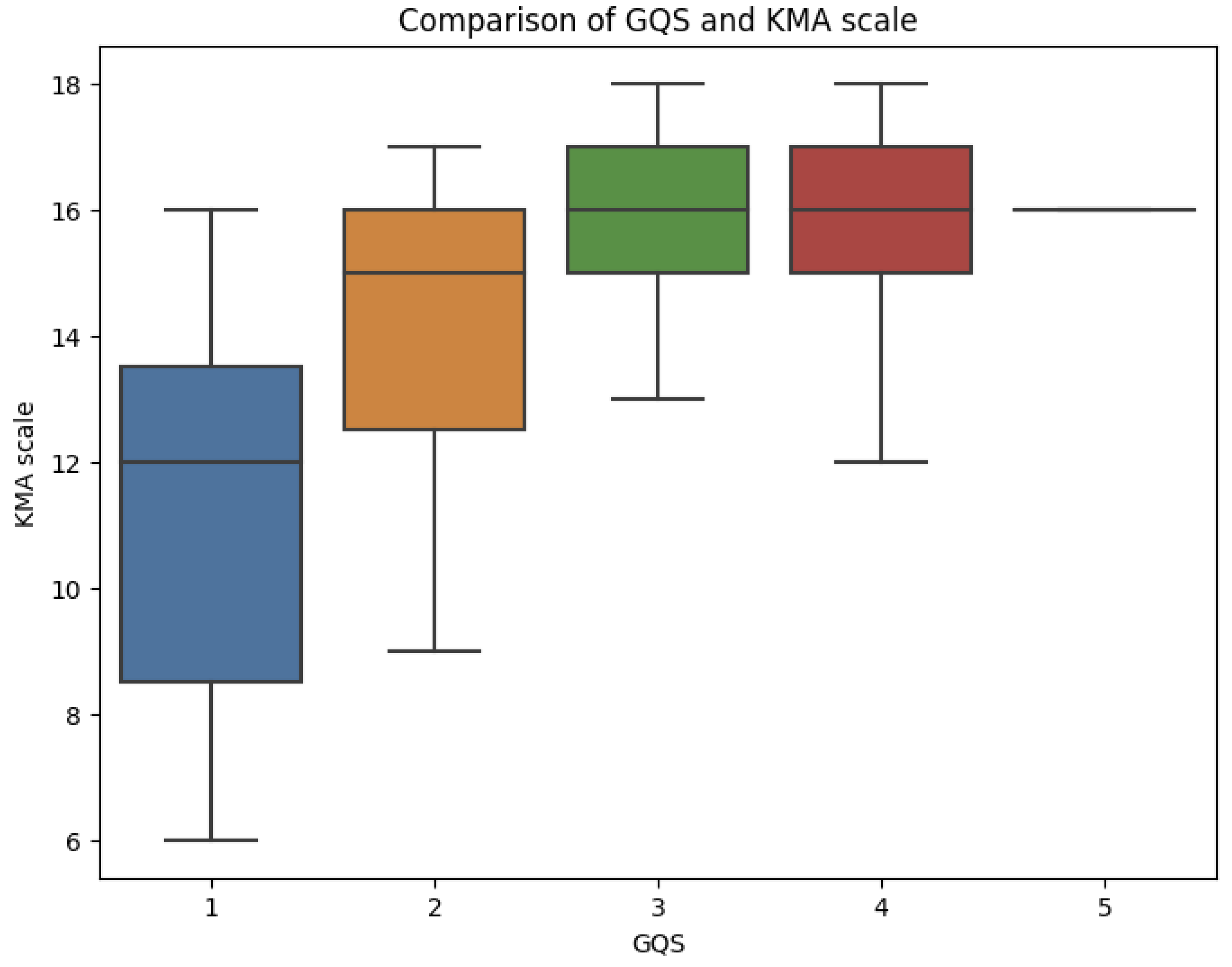

| GQS | 1 | 5 | 2.7 (0.96) |

| KMA scale | 6 | 18 | 14.8 (2.43) |

| South Korean certified medical service providers (N) |

Health care providers (N) |

GQS | KMA scale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ptosis Surgery | 10 (50%) | 18 (90%) | 3.25 +- 0.85 | 16.3 +- 1.22 |

| Ptosis Hospital | 9 (45%) | 17 (85%) | 3.15 +- 0.88 | 15.75 +- 1.83 |

| Ptosis Diagnosis | 5 (25%) | 17 (85%) | 2.8 +- 0.89 | 15.4 +- 2.14 |

| Droopy eyelid Surgery | 2 (10%) | 18 (90%) | 2.8 +- 0.95 | 14.4 +- 2.84 |

| Droopy eyelid Hospital | 3 (15%) | 19 (95%) | 2.45 +- 0.89 | 14.85 +- 2.03 |

| Droopy eyelid Diagnosis | 1 (5%) | 17 (85%) | 2.25 +- 0.91 | 13.8 +- 2.44 |

| Source of Upload | N |

|---|---|

| Plastic surgeon | 39 |

| Ophthalmologist | 20 |

| Dermatologist | 5 |

| Other medical professionals | 11 |

| Physical therapist | 1 |

| Non-professional | 3 |

| GQS | KMA scale | |

|---|---|---|

| South Korean certified medical service providers | 2.93 +- 1.03 | 15.27 +- 2.09 |

| Uncertified creator | 2.66 +- 0.95 | 14.67 +- 2.51 |

| P-value | 0.32 | 0.40 |

| Specialists(Ophthalmologists, Plastic surgeons) | 3.12 +- 0.66 | 15.47 +- 1.74 |

| Non-specialists(general practitioners, dermatologists, and family medicine practitioners) | 1.53 +- 0.64 | 13.33 +- 2.47 |

| P-value | 0.036 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).