1. Introduction

Tourism nowadays represents a rapidly developing area [

1], demanding a diverse offer of recreational, educational, sports and other activities of a similar nature associated with the secondary offer ensuring and supporting these activities. Reduced airline prices have allowed adventurous travellers to explore more unique sites with geological heritage and rich history. As a result, exotic destinations are now within reach for those seeking new and exciting experiences. Improved accessibility also provides opportunities for tourism and industry [2-4]. Geotourism, which primarily focuses on the geological and geomorphological features of the landscape, has been one of the fastest-growing market segments within the tourism industry during the last decade [5-7]. It is assumed that geotourism will continue to proliferate on a global scale. At the same time, it is necessary to highlight the importance of increasing the quality of knowledge, awareness and understanding of the need for protection and geoconservation. Geotourism generally deals with the theories and practical aspects of managing geotourism sites with high geological value [

8].

A geopark represents geographical territories that include sites representing geological heritage and are part of a holistic concept involving conservation, education and sustainable development [

9]. UNESCO defines a geopark as "an area containing one or more places of scientific importance from a geological point of view, but also from the point of view of its archaeological, economic or cultural distinctiveness of European or global importance." A differently worded definition speaks of an area with a significant geological heritage, with a comprehensive and robust management structure, where the strategy of sustainable economic development is established [

10]. Another definition presented by the Global Geopark Network (GGN) states that "a geopark must include a certain number of phenomena of uniform importance due to their scientific value, rarity, artistic and educational value, which can be part of archaeological, ecological, historical or cultural potential." [

11]

Geoparks, as a sustainable tourism product with their values and functions, are the answer to minimizing the negative impacts of tourism. The growing tendency to create and support geoparks requires a clearly defined management structure reflecting its needs.

The basic idea of geopark is the sustainability strategy in each territory. Geopark refers to protecting natural and cultural resources in a specific location. The main benefits of geoparks, according to Pásková (2009), are the following: an increase in the interest of residents and visitors in the values of inanimate nature, an increase in the quality of life of residents of rural locations, a combination of landscape diversity protection, the preservation of territory uniqueness with an appropriate presentation and interpretation of (not only) inanimate nature. She further points to the sustainable use of geological heritage for regional development, the role of the local community in sustainable tourism, the certification of geoguides and the marking of tourist trails, the connection of geology with the ecological and cultural values of the territory and mentions the support of local identity. She further emphasizes that the region's economic development is directly proportional to the development of these activities, which have a tradition in the given territory and are adapted to local conditions. She argues that preserving local traditions, culture, and crafts can be achieved through this approach. [

12]. Geoparks serve as a tool for the sustainability of tourism. Defined by the principles of sustainability, it is possible to easily define the pillars on which the sustainable development of geoparks stands, such as the protection of geological heritage, economic development, and community development. This effect is mainly achieved through geotourism and educational activities [

13]. EGN defines a geopark as: "a territory with clearly defined boundaries, with a sufficient size to enable economic development primarily through tourism. Geological sites must be of special importance regarding their scientific quality, rarity, aesthetics, and educational value. The individual locations are related to geology and archaeology, ecology, history and culture and form a theme park." [

14] UNESCO (2017) summarizes the essential criteria and assumptions the member and candidate global geoparks must meet. These criteria should be met by all geoparks if we modify some of the formulations according to the level of the given geoparks. The concept of geoparks still arouses misunderstanding and inconsistencies among the public. It is often considered only a geological park or a new category of legislatively protected territory, which speaks of a misconception. Geoparks in most countries are not defined by legislation; they are created based on the voluntariness of local actors and only cooperate with state-protected territories. It also follows that, although geological heritage is the basis for the establishment of a geopark, it is not an ordinary geological park but rather a platform connecting nature and people, which also confirms the motto of the UNESCO global geoparks program: "Celebrating the Earth's heritage, preserving local communities" [

15]. Geoparks should create development strategies that make full use of their possibilities and, at the same time, do not disturb the geological and other heritage. However, Hose and Vasiljević (2012, p. 31) point out that: "the interplay between the use of geological resources, geoscientific research, geoconservation and geotourism can be considered more complex than many authors acknowledge." [

16] A geopark cannot succeed without the support of the local community since it depends on local actors' initiative and voluntary declaration. [17, 18]. Pásková (2009, p. 15) aptly describes the geopark as "a creative link between the landscape and its inhabitants and visitors, between its ancient past and distant future, between science and play" [

12]. A geopark is a special place where natural heritage is interpreted through socio-cultural means, bringing geoscience and sustainable development closer to people. [

19]. This definition distinguishes it from world heritage monuments, whose goal is to preserve the monument in its current state with minimal possible changes [

20]. Farsani, Coelho and Costa (2011) highlight the contradiction of global geoparks, which are established internationally but managed locally [

21]. On the contrary, Henriques and Brilha (2017) consider this their essence and state that individual geoparks can best fulfil global sustainability goals by linking global challenges and local actions [

19]. However, the declaration of a global geopark must not cause the local community to be left out of decision-making because of increasing the territory's attractiveness. Halim and Ishak (2017) state that geoparks should be exclusively rural regions. Although this is the case in most cases, several functioning geoparks exist in the urban environment, e.g., the Hong Kong Geopark or the English Riviera Geopark [

17].

Destination management focuses on the development of the destination, considering the needs of all stakeholders, and the main task is to promote cooperation and coordination between them [

22]. The diversity of tourism services, especially the competitive structure in destinations and the need to share resources and cooperate with others, have prompted the study of cooperation in tourism destinations. Service providers must cooperate to offer integrated solutions for tourists. Doing so increases the value and integration in the destination and the exchange of experiences to generate interest [23, 24]. Destination management prefers the development of a rational mindset that favors cooperation over competition and sees this as the overall success of the destination.

2. Materials and Methods

Before exploring this topic in depth, it is essential to define the fundamental terms: geotourism, geopark, and management. It is necessary to explain the principles of geotourism as a modern direction of contemporary tourism to understand the concept of creating geoparks in general. Precious sources of information were articles from foreign professional sources that discussed the functioning of geoparks in the EGN and GGN networks around the world. The way geoparks work in these networks represented much inspiration and was the basis for creating four functional management areas and their activities. Considering the functions of the geopark, it was necessary to select appropriate management (management areas) according to the subject of management or management area. Each management area has its specifics, which must be considered for management to be effective. The definition of management areas subsequently represented a springboard for creating a questionnaire for Slovak geoparks in the Network of Geoparks of the Slovak Republic. This general questionnaire was created to gain insight into the strategic management areas in these geoparks. The questions were grouped according to the subject area of management, from general ones that described the legal form and organizational structure to specific areas of management such as marketing management, personnel management and the like.

The Management Selection method for geoparks, the essence of which is the multi-criteria analysis method, represented a suitable way to work towards specific results. This method is also described by various authors, e.g., Kubišová in the field of operational research, as well as authors dealing with management and the decision-making process in management, such as Fiala and the collective, Žáček (2015), Fotr J. and Dědina J. in the book Managerial Decisions from 1993 [

25,

26]. Specifically, Fiala [

25] and the collective stated the theoretical basis of multi-criteria decision-making: "multi-criteria decision-making tasks are those decision-making tasks whose consequences of the decision are assessed according to several criteria. If the set of admissible variants is finite, then we speak of the task of multi-criteria evaluation of variants. However, if the set of admissible variants is defined by a set of conditions that the decision alternatives must meet, it is a task of multi-criteria programming." (Fiala et al., 1994, p. 16) [

25].

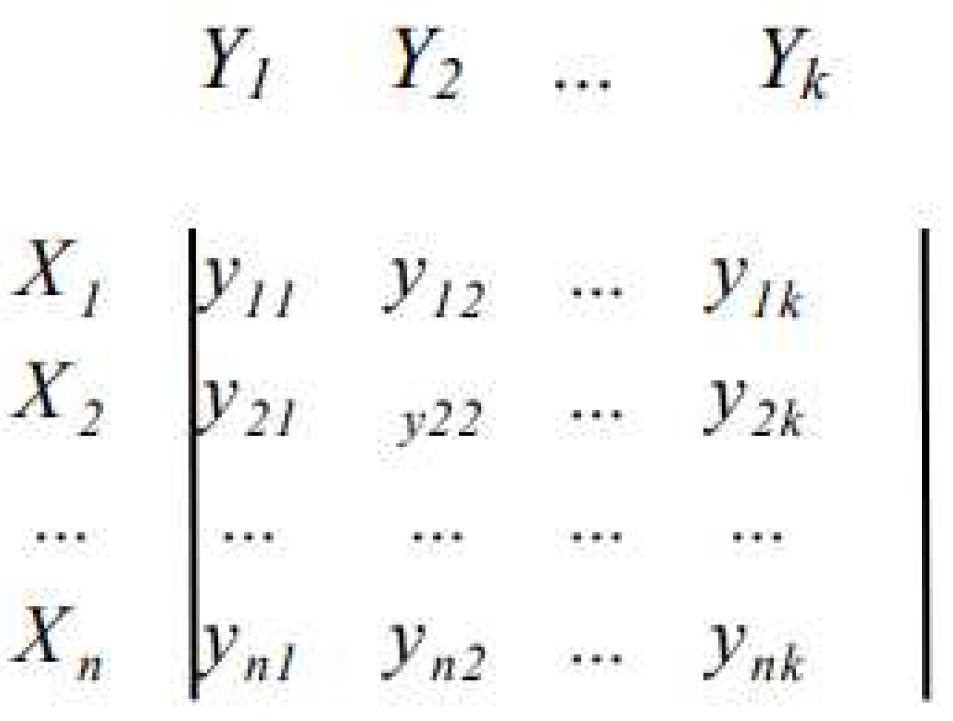

In cases of multi-criteria negotiation, a set X is determined, representing the decision variants Y= {Y1, Y2,...., Yn}. These variants are evaluated according to established criteria X1, X2,..., Xk. Each variant Yi, i=1, 2,…, n is described by a vector named according to the determined criteria of criterion values (xi1, xi2...., xik). The mathematical model of multi-criteria decision-making shows the so-called criterion matrix. In this matrix, in the i-th column is the vector of the variant Yi criterion values, and the individual criteria are displayed horizontally [

27].

The matrix of multi-criteria decision-making in mathematical expression looks as follows:

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Multi-criteria decision matrix [

27].

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Multi-criteria decision matrix [

27].

The method applies to various research areas and is very suitable for the qualitative nature of research in management and decision-making processes in general. The essence is the creation of a management selection matrix that will point out the suitability of the specified variants for specific established criteria. This analysis required the following procedure:

Determination of evaluation criteria that are based on the essential functions of the geopark and represent the points of view used in decision-making

Defining the quantification of the evaluation criteria

Determining the scales of measuring individual criteria according to the geopark's functional areas

Determination of criteria variants

Evaluation of the decision matrix by the method of selecting the dominant variant/dominant variants

When building a multi-criteria matrix, three types of values are available, namely:

Nominal scales divide a set of variants into two or more groups, the usefulness of which is expressed simply from the point of view of a specific criterion (e.g., 1 – meets, 0 – does not meet).

Ordinal scales represent the number of points or scale intervals corresponding to the number of assessed variants. The numbers assigned to the individual variants only determine the order of the variants according to some criterion but do not express their mutual ratio (size of preference). The resulting order of the variants is determined according to the total or average number of points obtained.

Cardinal scales make it possible to express not only the order of variants but also the mutual ratio of their usefulness (we consider the most favorable value for each criterion to be 100%, and the usefulness of the others is expressed as a proportionally lower percentage). [27-29]

The essence of the evaluation process is the section of the suitable variant for the established criteria. The classification of variants aims to divide the variants into several classes, which Jablonský stated as follows, and at the same time, he states that when comparing two variants, the following variants can occur:

An ideal variant (achieves all the best possible values)

A basal variant (reaches the minimum values, is the opposite of the ideal variant)

A dominated variant is when one can find a variant that is better or at least equally good in all criteria.

A non-dominated variant for which the previous statement does not apply is the so-called non-dominated, a variant for which no variant dominates it according to all criteria; there are usually several non-dominated variants [27-29].

Compiling criteria in individual management areas was necessary during the selection method. The categories of these areas are based on the functions that the geopark must fulfil. The basis for determining specific criteria was the study of foreign professional and scientific articles that dealt with the functioning of geoparks in the EGN and GGN (UGG) networks. They depicted how important geoparks function, their activities and functions, the description of which was contributed by influential experts and authors in the field of geoparks, such as José Brilha, N.T. Farsani, R.K. Dowling, D. Newsome, C. Coelho, C. Costa, P.J. Mc Keever, N. Zouros, I. Valiakos and others [3,6,7,9,19,30-43]. The supporting element in the analysis, but also the determination of criteria for the creation of a new management model, was the form used in the process of accepting and evaluating geoparks into the Global Geoparks Network, currently called UNESCO Global Geopark, entitled "Self-Evaluation Checklist for aspiring UNESCO Global Geoparks (aUGGp )" [

44], based on which the criteria were adopted.

Four criterion areas consisting of partial criteria were chosen. These four areas were based on essential functions and depicted four areas of activities and activities requiring effective managemeng. They represented the area of protection and geoconservation, which includes creating a protection strategy, specific activities ensuring protection and geoconservation, and activities related to research and creating valuable educational materials. The second field of criteria was Geotourism, which includes the creation of geotourism sites and routes, the creation of geotourism infrastructure, the operation of information points, the design and implementation of projects in this area, the creation of modern geotourism programs for various target groups. The third group consisted of activities aimed at education, the creation of educational goals, educational programs, cooperation with educational institutions, and offering educational activities for geopark residents. The fourth criterion, the Development of the territory, consisted of activities such as promoting the territory, cooperation and coordination with local entrepreneurs, developing the territory through projects, increasing employment and improving the territory's infrastructure. The choice of criteria was conditioned by the creation of suitable variants, where different types of management were grouped. After the criterion evaluation of the geopark activities, it was necessary to define the quantification of the criteria, that is, to express it numerically for better processability.

In the selection method of suitable management for geoparks, it is necessary to create two matching matrices; the task of the first one is to search for an ideal and dedicated type of usable management for geoparks. In this case, we do not assign a degree of importance to the criteria but only choose the nominal values 0 and 1 and, thus, whether the given management meets or does not meet the set criteria. Suppose it is impossible to find an ideal variant suitable for managing the geopark. In that case, we will subsequently create an identical selection matrix, which, based on assigning weights to individual criteria, will determine which type of management or which combination of management suits the geopark and its management environment. For the evaluation process, a scale of values 0 and 1 was chosen (confirming the suitability for the given criterion and rejecting it for the given criterion), while the value 0 means that the given variant of management is not suitable, and the value 1 means that the type of management is suitable for the criterion. The group of criteria in individual areas was determined during the research in no order of importance; the authoritative information for us was whether a specific management variant was suitable for a given criterion. Determining the variants represented the determination of different types of management. The essence consisted of obtaining points for individual management variants; the maximum possible number obtained represented the total sum of the criteria established for the evaluation selection matrix. The essence of this method is to determine the most suitable variant of management for a given area or a combination of management for different areas of management. There is also the possibility that several variants are suitable for one criterion; one variant does not exclude the other. The task of this matrix is to find the ideal variant of suitable management for the geopark. The ideal variant confirms values in all criteria, i.e., values.

Suppose the first matrix needs to show us the ideal variant suitable for managing the environment of the geopark. In that case, it is necessary to continue creating a second identical matrix by expanding it by adding the weights of individual criteria, which will help identify a unique management model suitable for the given environment. The scales express the importance of individual criteria according to the system of evaluating geoparks in the Global Geoparks Network. The first selection matrix with a nominal expression of values was the basis for recalculating the weights for criteria and variants. Adding weights to the second matrix will help display the most suitable management types for the geopark. The weights were determined based on a point evaluation process, adapted to the established criteria of this selection method, inspired by the geoparks evaluation process in EGN and GGN networks. The method of selecting the dominant variant or dominant variants was used to evaluate the matrix, which represents the filtering of variants and, subsequently, the selection of variants, which can be a grouping of different types of management. The result is the selection of management, which will subsequently create a suitable management model for the geopark.

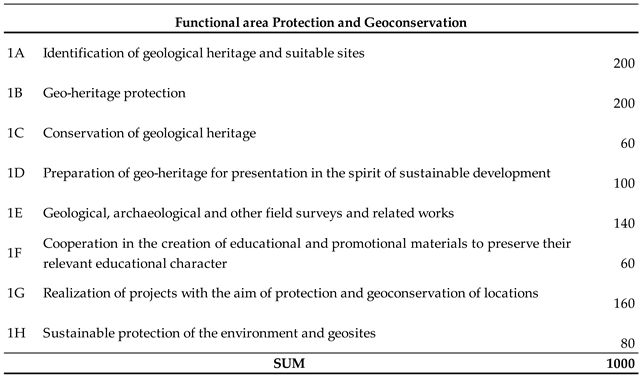

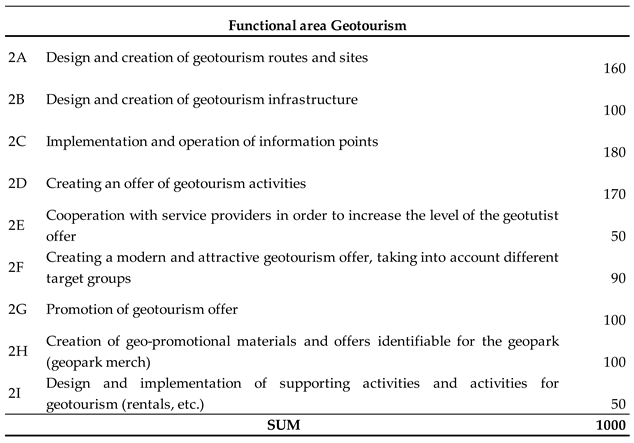

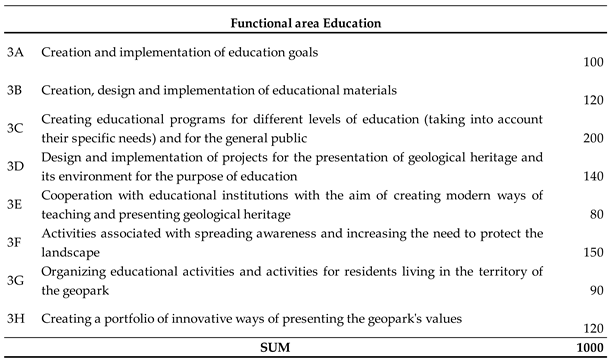

When creating the matrix, four areas of criteria were determined in a vertical line, namely:

Criterion decision area 1 - Protection and geoconservation, contains eight criteria ranging from 1A to 1H

Criterion decision area 2 - Geotourism, contains nine criteria ranging from 2A to 2I

Criterion decision area 3 - Education, contains eight criteria ranging from 3A to 3H

Criterion decision area 4 - Territorial development, contains six criteria ranging from 4A to 4F

When choosing the variants, 21 management variants were determined in the matrix indicated by the designation V1 to V21 in a horizontal line. The types of management were chosen according to whether they were related to the activity of the geoparks or at least partially affected it.

The selection matrix effectively deals with choosing variants evaluated according to several criteria. A significant positive of this method is the multi-criteria nature of decision-making problems, the non-additivity of the criteria, the suitability of use for a mixed set of criteria and its usability in evaluating qualitative data. It is necessary to point out the fact that although the creation of the selection method was based on professional articles in the field of geoparks functioning, the sources still need to indicate a specific management model or management structure in the geopark. The authors analysed activity, activities, and case studies, but none specified a management model generally suitable for geoparks. It is desirable to deal with the issue of management from this point of view and to define the model and structure of management, which is also the goal of this method and article.

3. Results

The primary purpose of a geopark is to safeguard the environment and natural features of the area, which involves promoting geoconservation and protection and facilitating scientific research within the geopark. Scientific research cannot be excluded from the function of a geopark because it is necessary to know what values the given territory offers, in what way they need to be protected, and, at the same time, presented to preserve their original value as much as possible. Another critical function is education and raising society's awareness of the need for nature protection. Education is understood for all age categories of visitors; the lower the age category is addressed, the more effectively the information will be processed. Education in early childhood fundamentally influences a person and affects his future behaviour in adulthood. This fact is crucial for raising awareness of society in any field. Marketing is an integral part of geopark functions due to the presentation of the territory and visibility. Even in the case of the functioning of all other areas in geopark, which would fulfil their functions, effective marketing and promotion are necessary to ensure the overall prosperity of a geopark. Obtaining funds for geopark's functioning in the Slovak Republic requires considerable effort in managing finances. In our current situation, the geopark must find ways to obtain funding for operations without direct state support independently. This process is very lengthy and greatly hinders the development of the geopark. Considerable attention must be paid to fundraising since it affects the geopark's plans, functioning, and existence. The goal of every creative activity is to achieve efficiency and fulfil goals. In this case, achieving such an outcome depends solely on having a skilled workforce. Personnel coverage and partnerships participating in the achievement of goals, the selection of workers and people involved in the activity of the geopark influence the overall result of functioning with their personality, experience, qualities, enthusiasm, and status.

Determination of criteria according to functional areas in geopark management

Definition of partial activities (areas) in the decision-making process of the geopark according to the functions that the geopark must fulfil (individual criteria were chosen based on the activities resulting from the four essential functions of the geopark):

Table 1.

Scoring of the Protection and Geoconservation Criterion area [author].

Table 1.

Scoring of the Protection and Geoconservation Criterion area [author].

Table 2.

Scoring of the Geotourism criterion area [authors].

Table 2.

Scoring of the Geotourism criterion area [authors].

Table 3.

Scoring of the Education criterion area [authors].

Table 3.

Scoring of the Education criterion area [authors].

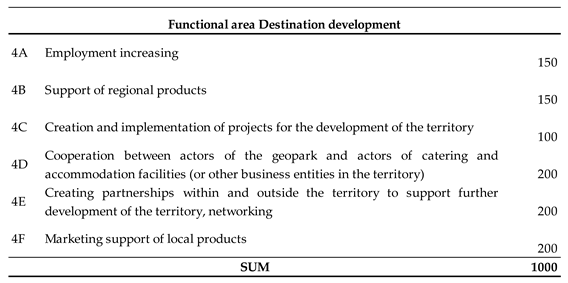

Table 4.

Scoring of the criterion area Development of the area [authors].

Table 4.

Scoring of the criterion area Development of the area [authors].

Considering the diverse structure of activities, the following variants of standard types of management, which are commonly used in companies and organizations, were determined (the types of management, that is, the variants, were chosen according to whether they were related to the activity of geoparks, or at least partially affected it):

V1 Strategic management

V2 Operational (operational) management

V3 Sales management

V4 Business management

V5 Marketing management

V6 PR management (Public Relations)

V7 Supplier management

V8 Procurement management

V9 Financial management

V10 Personnel management

V11 Information technology management

V12 Scientific and research management

V13 Engineering management

V14 Project management

V15 Risk management

V16 Quality management

V17 Management of opportunities

V18 Design management

V19 Educational management

V20 Destination management

V21 Cooperative management

Determining individual measurement scales according to the functional areas of a geopark

When determining the measurement scale, we need to determine whether we evaluate the mutual connection between the individual criteria and whether they have a particular value of importance or order within the criteria. In our evaluation case, we will not consider these features and give them any relevance or weight from the management's point of view. We will evaluate the specified criteria independently. From the point of view of determining the scale of measurement, we have available for the selection decision-making method a nominal scale of values, which represents the division of a set of variants into two or more groups, the usefulness of which is expressed simply from the point of view of a specific criterion (e.g. 1 – meets, 0 – does not meet). The decision-making matrix for selecting suitable management in geoparks by applying a nominal scale in the decision-making process represents a simple and effective way of selecting the type of management in connection with the established criteria. The results in individual criterion areas (4) may differ from each other because a different type of management is suitable for each specific management area.

The first selection matrix with nominal values

By inserting nominal values into the selection matrix of geopark management in a multi-criteria decision-making process, a set of values is created that reflects the suitability of the used variant. In this case, the goal is to find an ideal variant of a suitable type of management for the management of geoparks. For us, the ideal variant is if the set of all values for the given management variant represents a value of 1 - it satisfies. The goal of this matrix is to get a comprehensive view of the suitability of different types of management; while using the matrix, we are looking for an ideal type of management that exclusively represents all the needs and specifics of the geopark.

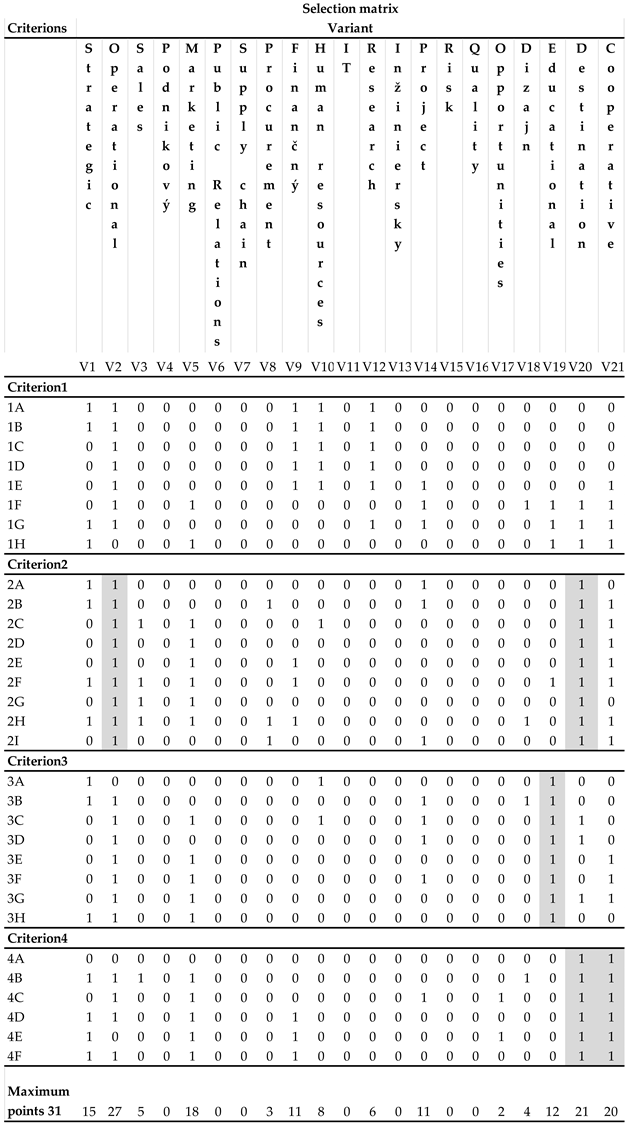

Table 5.

Geopark management selection matrix with nominal values [authors].

Table 5.

Geopark management selection matrix with nominal values [authors].

Evaluation of the selection matrix with nominal values

The nominal values in the selection matrix led us to the following conclusions. Within all the evaluation criteria for the management variant from V1 to V21, it was found that there is no ideal type of management that would satisfy all criteria. By evaluating individual criterion areas separately, the matrix pointed out that there are ideal management variants. As a separate entity, none of the selected variants existed for criterion 1, protection and geo-conservation. Criterion area 2 Geotourism received the ideal variant V2, which represents management from a time point of view, so it is necessary to focus on creating operational plans for individual sub-criteria to fulfil sub-goals. Operational management here does not present a specific type of management from the subject's point of view but from the point of view of time. However, this information is also helpful because it represents the need to create short-term plans. Criterion 2 received one more ideal variant, namely V20, representing destination management closely related to regional development. This output confirms that creating strategies and managing the territory as a destination is critical for geotourism. By evaluating the results of criterion area 3 Education, the values clearly and undoubtedly logically choose variant V19, i.e. educational management. For criterion area 4, territorial development, V20 Destination Management and V21 Cooperative Management are clear favourites and ideal variants.

Partial results for individual criterion areas (assessed separately) confirmed the ideal variants. This output is valuable in creating sub-strategies and plans and indicates how it is appropriate to manage the given area. However, in a comprehensive evaluation of the areas, it is necessary to approach the areas as a whole because the failure to meet the goals in one area represents the inefficiency of the whole. As part of the overall assessment, it should be noted that the matrix did not show any suitable dedicated and only type of management that would meet all the criteria.

Based on the findings, it is necessary to establish a further procedure that will lead to the selection of management or a variation of management that would represent a suitable management method. The next step is the creation of a second management selection matrix, which, based on the supplemented weights of the individual criteria, will point to a combination of suitable variants. The total number of points of individual variants in the selection matrix tells us there is no ideal type of management, meaning that the geopark must find a suitable management structure for effective management and performance of functions in each area. For this, it is necessary to use the model of the second selection matrix.

The second selection matrix with the assignment of weights

The selection through a selection matrix with nominal values showed that the ideal and reserved management type does not exist or is not suitable for the management of geoparks. Therefore, it is necessary to determine which management type would more closely determine the characteristics of suitable management. Based on the selection matrix, it is necessary to find a suitable method of further selection to determine the importance (weight) of a specific type of management for a particular criterion. The next step is to create an identical selection matrix, with the difference that we set weights for individual criteria to arrive at values reflecting the importance of a specific type of management. The criteria and variants will remain original; we will assign points to the criteria, the basis of which is the evaluation process used in the entry process of geoparks into the Global Geoparks Network. Based on this scoring system, points will be assigned to individual criteria, which will be converted into weights. The individual criterion areas have the same sum of points since all management areas must be functional when managing geoparks. The assignment of weights was carried out to express the importance of individual activities in functional areas and affected the overall result of individual criteria. The following tables show the scoring assigned to the criteria in the functional areas of Protection and Geoconservation, Geotourism, Education and Development of the Territory.

The recalculation of nominal values by weights created the following model of the second selection matrix.

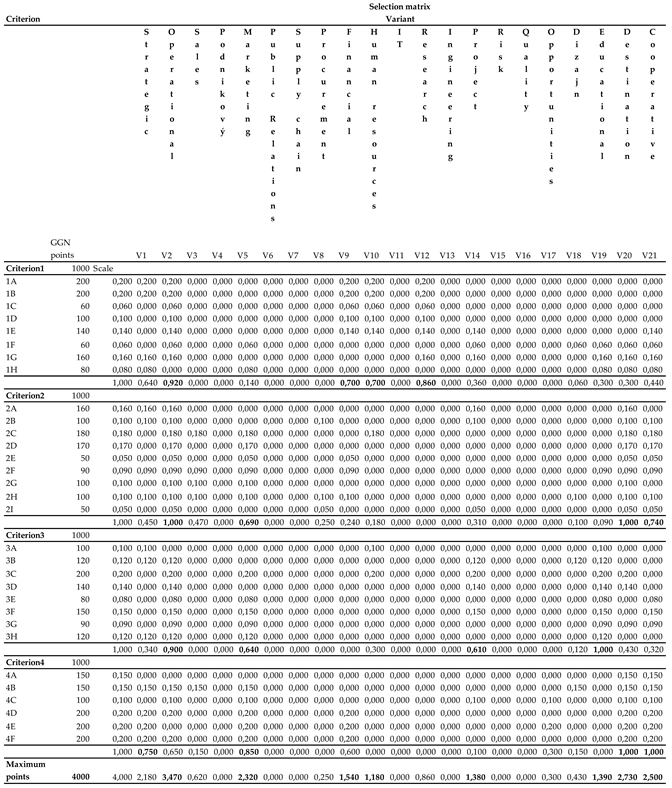

Table 6.

Second selection matrix of geoparks management [authors].

Table 6.

Second selection matrix of geoparks management [authors].

Evaluation of the second selection matrix with determination of weights

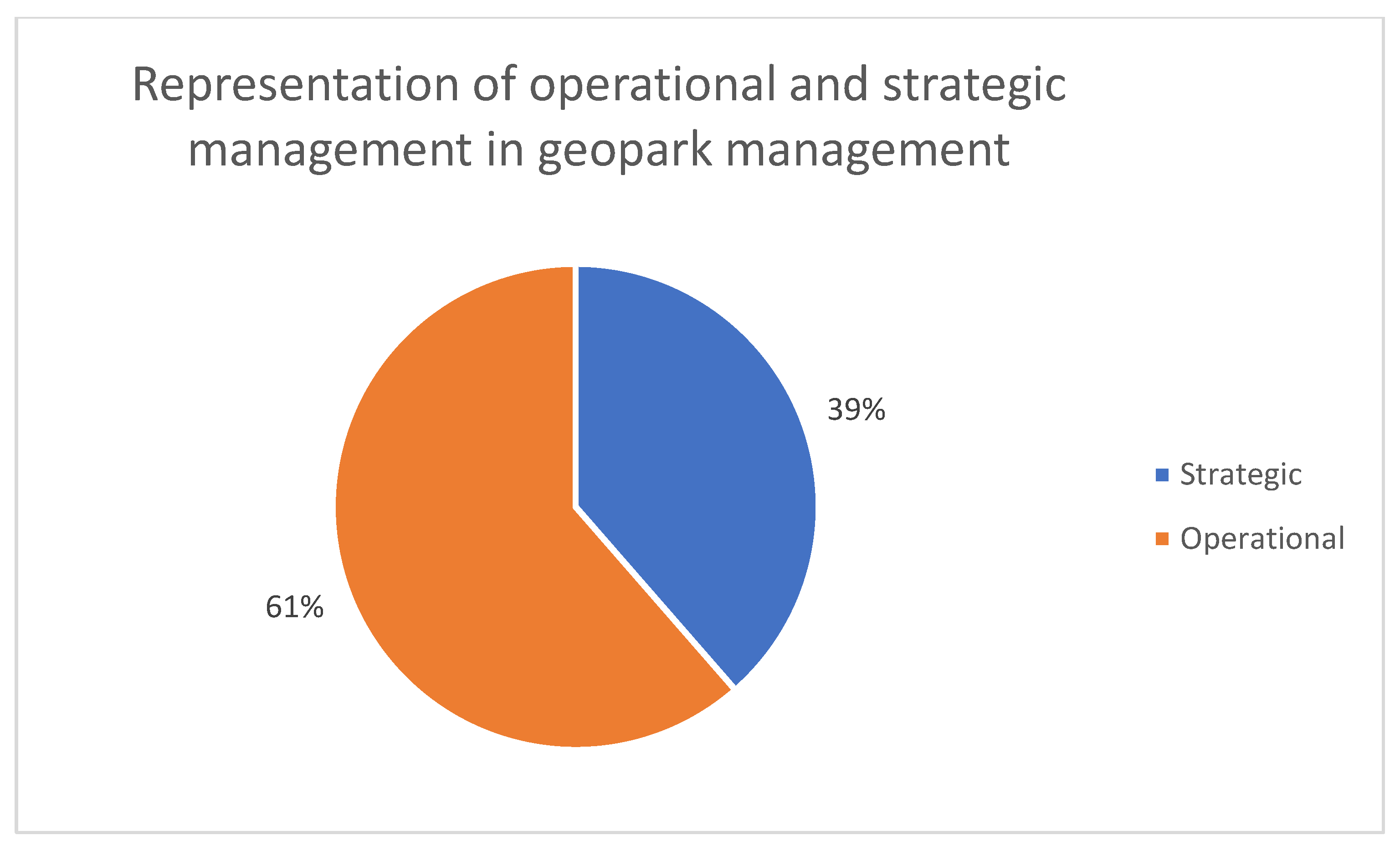

From the evaluation of the matrix as a whole, it is necessary to focus on operational planning and management because this ensures specific activities that, step by step, fulfil the plan of strategic goals. The result does not mean the geopark should not engage in long-term planning. However, the advantage here is that the strategies are determined and elaborated, and clear goals are set that the geopark should cover strategically in the given territory. Strategic issues are addressed in conceptual and strategic materials and documents of international importance, which were mentioned in previous chapters dealing with analysing the state of the issue in the conditions of the Slovak Republic. These materials are the basis for long-term strategic management, on which geoparks are oriented. However, no "help" is mentioned anywhere: what, when and how to plan, manage or implement. The outputs from the second selection matrix clearly define the need to direct attention to solving the question of how to manage and plan sub-goals and thus use the specifics of operational management. The following graph also shows this fact, which represents strategic and operational management.

Figure 2.

Ratio of strategic and operational management in the geopark [authors].

Figure 2.

Ratio of strategic and operational management in the geopark [authors].

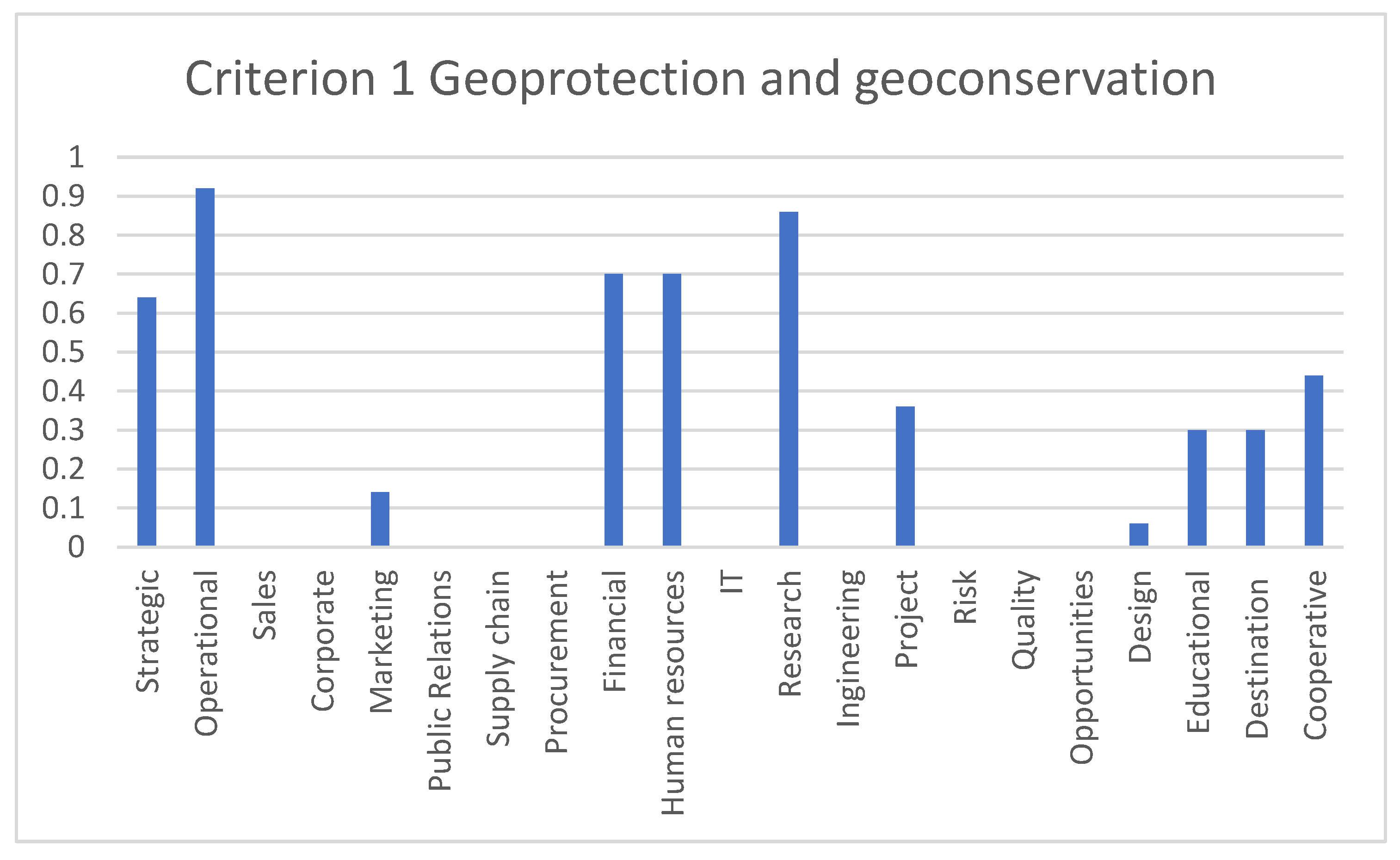

The assignment of weights created a different results structure than the first matrix. Specific types of management crystallized differently in each criterion area. The essence of the matrix evaluation was to find the highest values, but the results of individual criterion areas are also worth mentioning. The three highest values in each area were considered. Notably, in the first area of criteria K1, none of the variants came out clearly; it did not equal the value of 1. Apart from variants V1 and V2, which point to time management, which has already been evaluated, variants V9 Financial Management showed the highest values, and V10 Personnel Management, equally represented with a value of 0.70. The highest value of 0.86 of this criterion was obtained by the variant V12 Scientific-research management, which logically follows from the function of this area. It is necessary to orientate to the greatest possible extent. It follows from the values that it is necessary to concentrate on managing scientific and research activities and to focus on high-quality and professional personnel, which must be adequately evaluated. The financial side is characterized by high demands, which implies the need for high-quality financial management with a clear vision and a plan to cover activities with finances. The mentioned values and composition of individual variants for this area are expressed in the following bar chart.

Figure 3.

The result of the Protection and geoconservation criterion area selection [authors].

Figure 3.

The result of the Protection and geoconservation criterion area selection [authors].

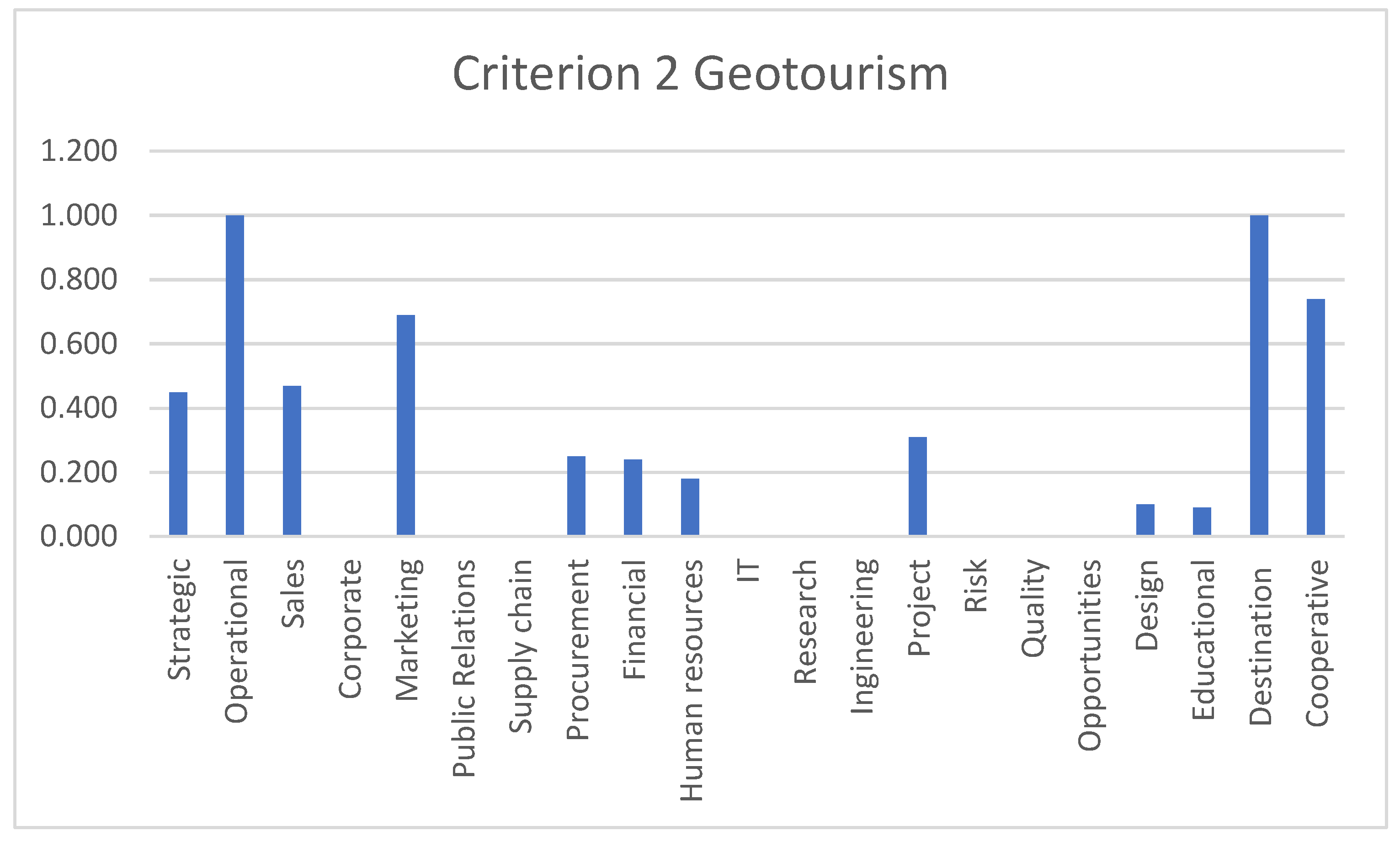

Geotourism as criterion area 2 speaks about the need to apply variants in management, namely V20 Destination Management, V21 Cooperation Management and V5 Marketing Management. Variant V20 achieved the highest value with a value equal to 1, i.e., the highest possible, followed by variant V21 with a value of 0.74 and then V5 with a value of 0.69. If we take this criterion separately, it is necessary to manage the area of geotourism as a destination, of course, with effective cooperative management, which in this case is also crucial to maintaining relationships and support for geotourism activities and activities. An integral part is support in the form of marketing, which is currently a very modern and effective tool for achieving goals in any sector. The values and associated management variants of this area are shown in the following graph.

Figure 4.

The result of the selection of the Geotourism criterion area [authors].

Figure 4.

The result of the selection of the Geotourism criterion area [authors].

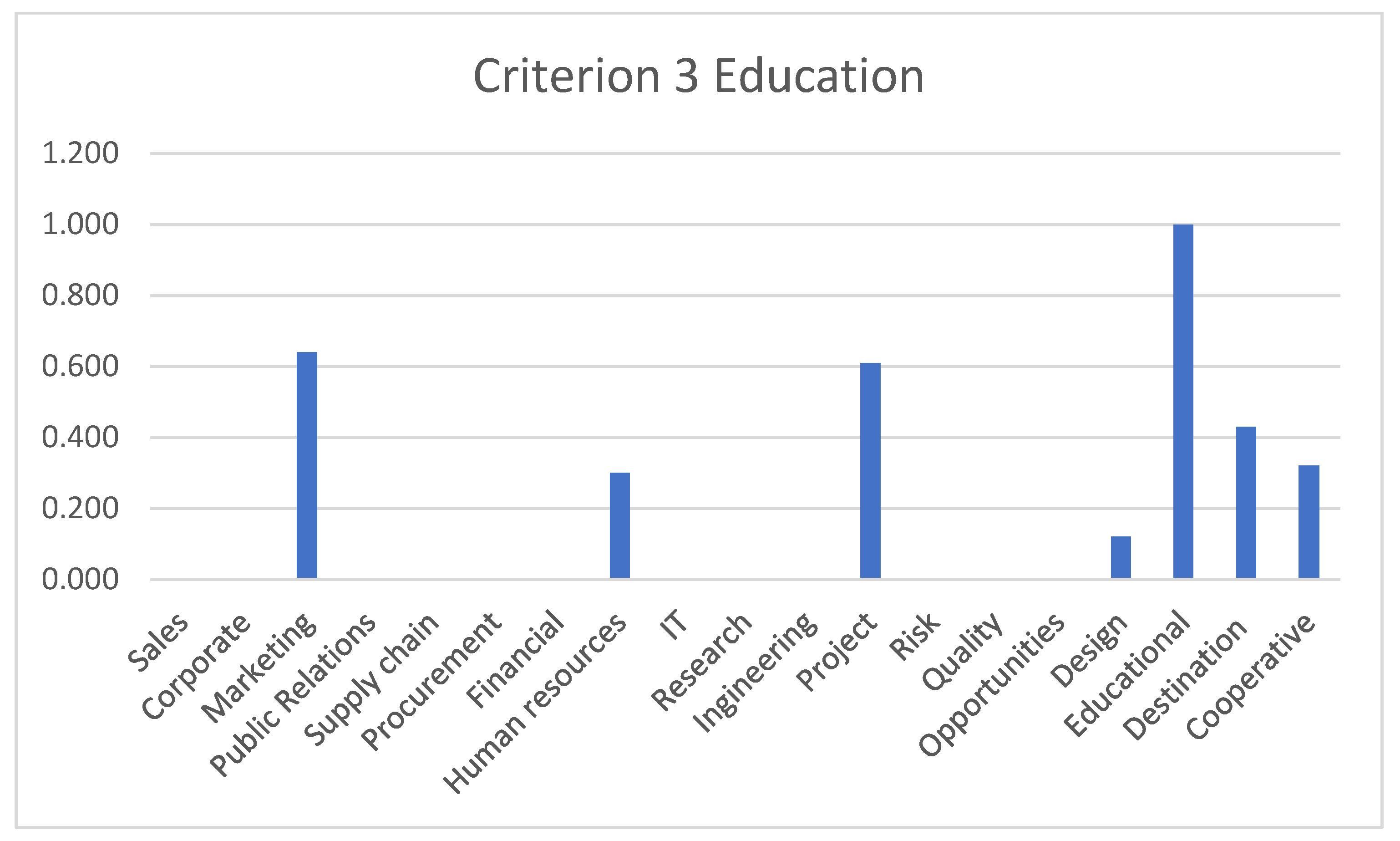

The broad scope of educational activities and activities requires quality management and planning, management coverage and structure. The results point to three variants of the most significant representation in management. Variant V19 Educational management reached a value of 1, which was logically expected based on the function of this area. Variant V14 Project management represents a value of 0.61. Project management is essential in this area because of obtaining funds to implement educational programs and activities. High-quality project management will ensure participation in national and international projects and educational programs and help cover financial resources. As in the Geotourism criterion, the need to manage marketing and marketing activities is also apparent. With sophisticated marketing management and high-quality plans, a communication strategy for addressing target groups will ensure the desired result of arousing interest in knowledge of the territory's heritage. The value of the V5 Marketing management variant is 0.64. The following chart shows the management structure in the field of education.

Figure 5.

Selection result of the Education criterion area [authors]

Figure 5.

Selection result of the Education criterion area [authors]

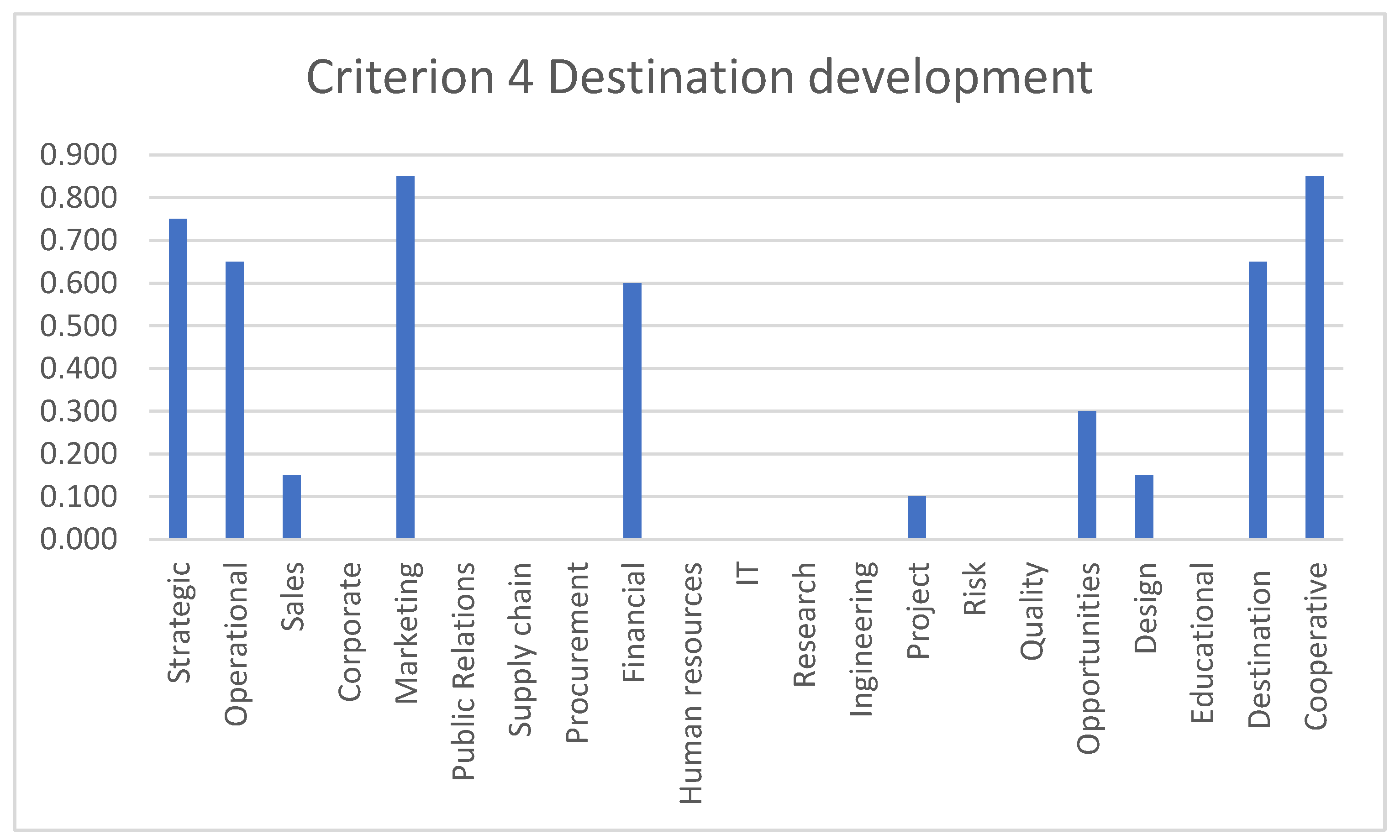

The last criterion area, K4 Territorial development, is defined by the following variants as suitable for management. Variants in this area have a solid and dominant presence, also indicated by the values.

The following chart shows the representation of individual variants for the Territorial Development Area. Variant V20 Destination management and V21 Cooperative management reach the maximum level, i.e., a value of 1. The third dominant variant, V5 Marketing management, with a value of 0.85, is also not far behind and confirms the findings from previous areas that marketing in the geopark has a key and supporting function and needs to be devoted to its attention at all levels of management, including it in the creation of plans and in achieving goals can have a strategic value. Criterion K4, the development of the territory, requires a form of destination management that meets all the necessary attributes.

Figure 6.

The result of the selection of the Development of the territory criterion area [authors].

Figure 6.

The result of the selection of the Development of the territory criterion area [authors].

Integrated Geopark Management Model

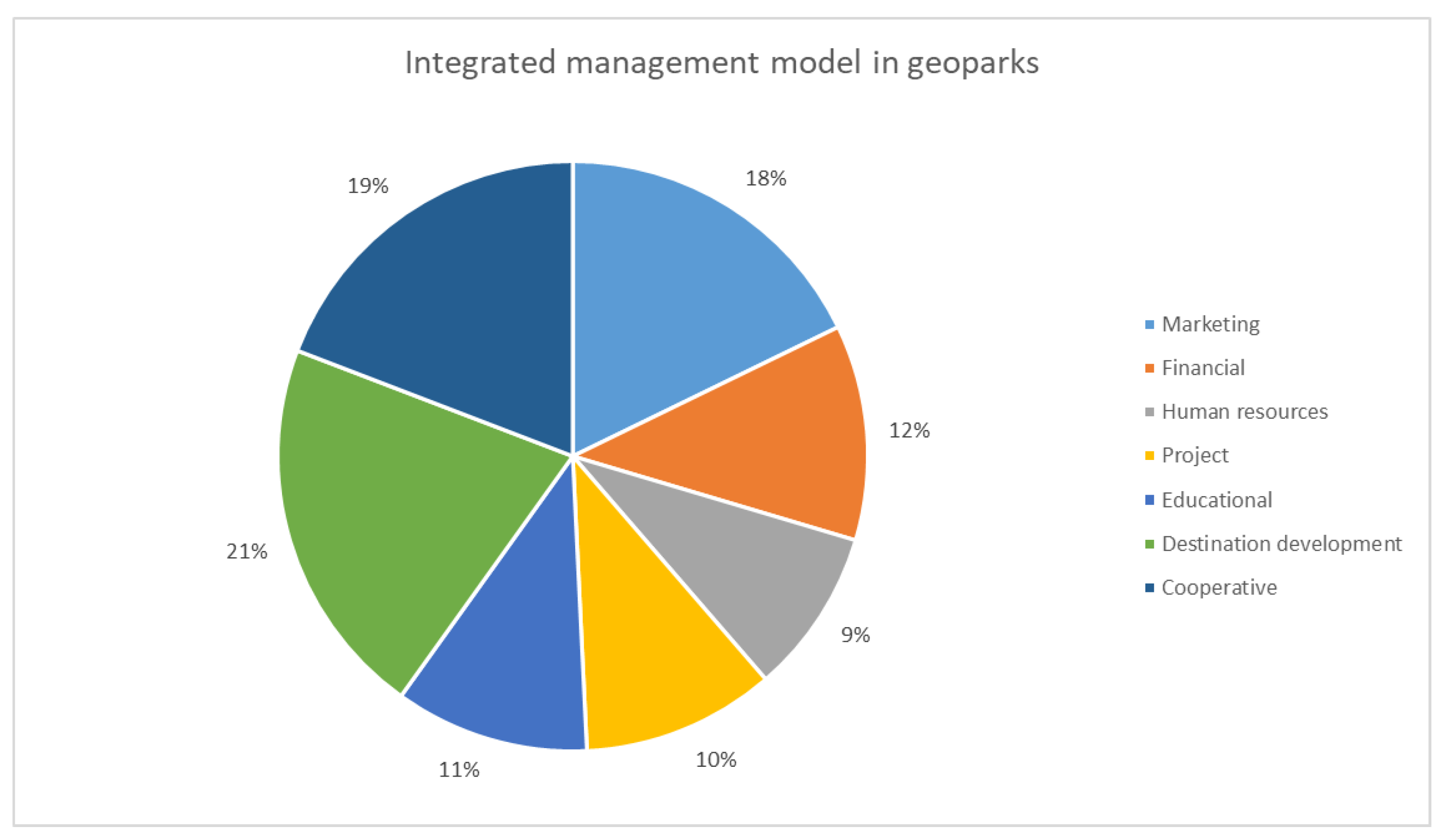

The conclusions resulting from the selection method were the basis for creating a suitable management model applicable to the management environment of geoparks. Defining the criteria of functional areas and management variants created a selection of suitable variants. For the geopark management in the selection matrix, several types of management were suitable in different degrees. It is, therefore, desirable for a clear structure to select the most dominant ones, which will be the way of management. The management structure and its requirements are taught by the following model, compiled from the most dominant management. When we talk about geoparks, geotourism or sustainability, there is integration. This concept will also describe the created model, the essence of which is the connection of parts into a single whole, consolidation, wholeness, unification, and grouping of individual types of management into one functional unit. For the geopark, this means focusing on more types of management for individual activities. The theoretical basis is the so-called integrated management model. In practice, the geopark must provide quality professionals who would apply these management methods depending on needs which currently need to be solved. Quality and well-founded staff means quality and efficient management. The specific results of the selection matrix are shown in the following pie chart, which combines key management into an extended integrated whole.

Values were selected from the final values of the second selection matrix, where variants with values higher than ¼ of the total value of the sum of weights in all criterion areas were selected. Variants with a value higher than one were chosen for the resulting integrated model of the management structure because these represent a dominance higher than 25%.

The model showed the following management structure in the composition of variants related to marketing management, finance, project management, destination management, education, and personnel issues. The management structure reflects the needs of the geopark. It shows the areas on which management should focus to achieve the desired goals — underestimating any area of management results in a reduction in the quality of activity, inefficiency, or even the inability to achieve any of the goals.

Figure 7.

Integrated extended model of geopark management structure [authors]

Figure 7.

Integrated extended model of geopark management structure [authors]

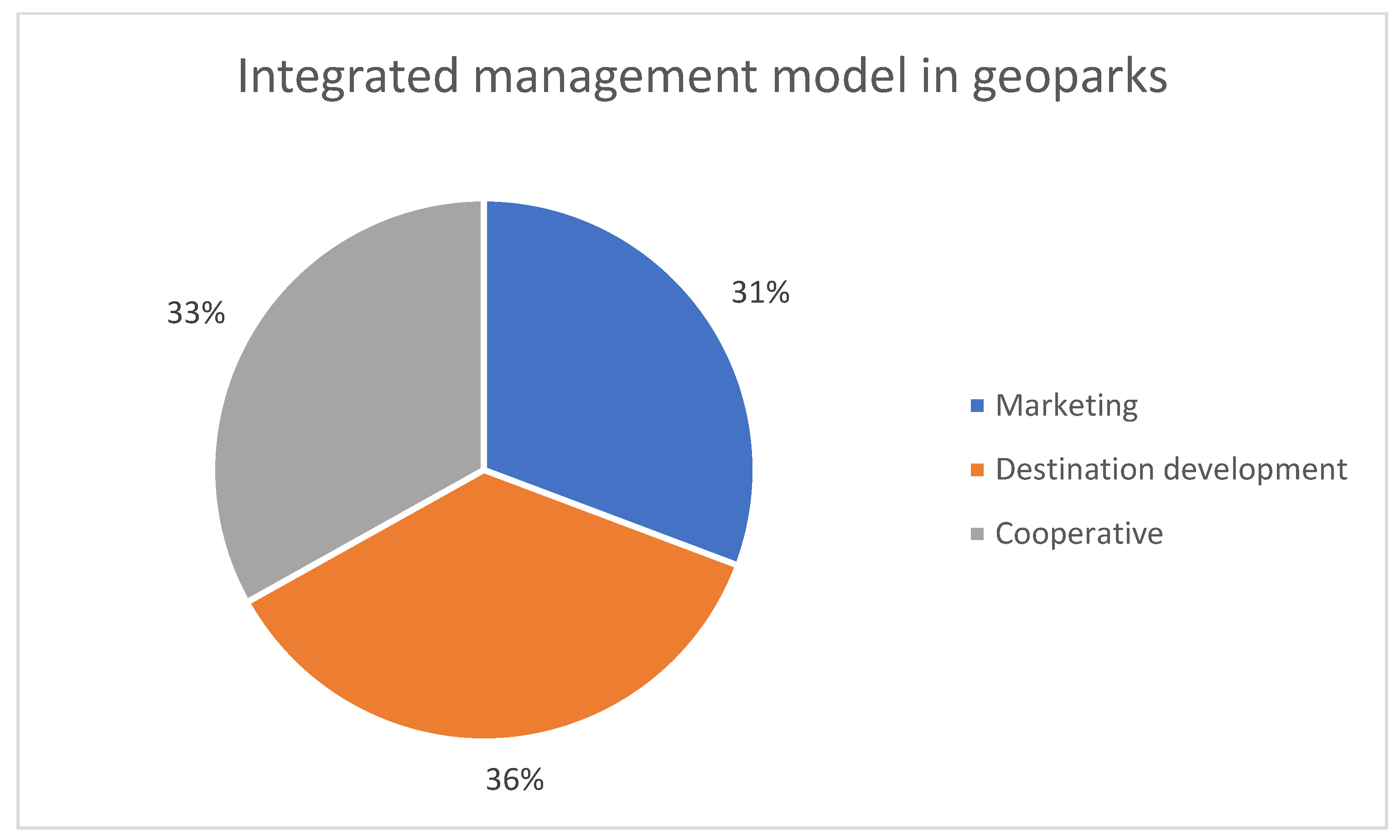

In short, this model shows the three most dominant variants. These managements' ratios were balanced, almost identical, with minor deviations. The geopark management needs to be ensured: 36% by destination management, 33% by cooperative management and 31% by marketing management. The following graph shows the management model cleaned of previous sub-managements.

Figure 8.

Integrated model of geopark management structure [authors]

Figure 8.

Integrated model of geopark management structure [authors]

Even though the nature and behaviour of a geopark are in some ways similar to a business and corporate management, with the difference that the business generates profit and thus prospers, the geopark, on the other hand, shows prosperity in the form of cooperation, not competition, by creating purposeful partnerships, ensuring the protection and development of the territory. This model confirmed the need to manage the geopark as a destination that brings profit to the territory in the form of increasing the standard of living and awareness of the population, improving, and protecting the environment, a strategy of sustainability and the overall added value of the geopark for the territory where it is located. From the confirmed conclusions and the created model, geoparks can draw knowledge and create a direction in management. The positive aspect of the model is its universality, which means that it can be used by changing and adapting the criteria to different forms of tourism, considering their specificities.

The article aimed to create a valuable whole that comprehensively presents the management of geoparks and the following benefits in both theoretical and practical terms.

The theoretical contributions of the work include the following:

Analysis of management areas in geoparks - defines geopark functions and categorizes them into four functional areas. It defines the essence and goals of these areas and highlights what is crucial for management.

Defining the management environment in which the geopark is located and the attributes related to it defines the components of the management environment of the geopark, defines the properties of the environment in which the geopark is located, and names the entities entering into relations with the geopark, their position and purpose in this environment.

Creation of a selection method for the decision-making process in geoparks: defining activities in the geopark from the point of view of functional areas in the form of criteria and their relationship to individual types of management, depicting possible variants of management in the geopark.

Creation of a general model of the management structure for geoparks: defining key management variants and their relative position.

The practical benefits of the article are as follows:

The categorization of functional areas and the analysis of individual activities for creating operational plans and sub-goals can be used.

It is possible to use the established criterion areas and their criteria in creating sub-plans according to the criteria in the selection matrix.

Using the selection method and its universal model in decision-making processes in any field is possible.

The conclusions of the selection method and the direction of a suitable management method in individual areas can be used further.

The selection method may be used in other tourism sectors (e.g. mining tourism) by choosing adequately adapted criteria to the specifics of the given area.