Submitted:

14 October 2023

Posted:

17 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

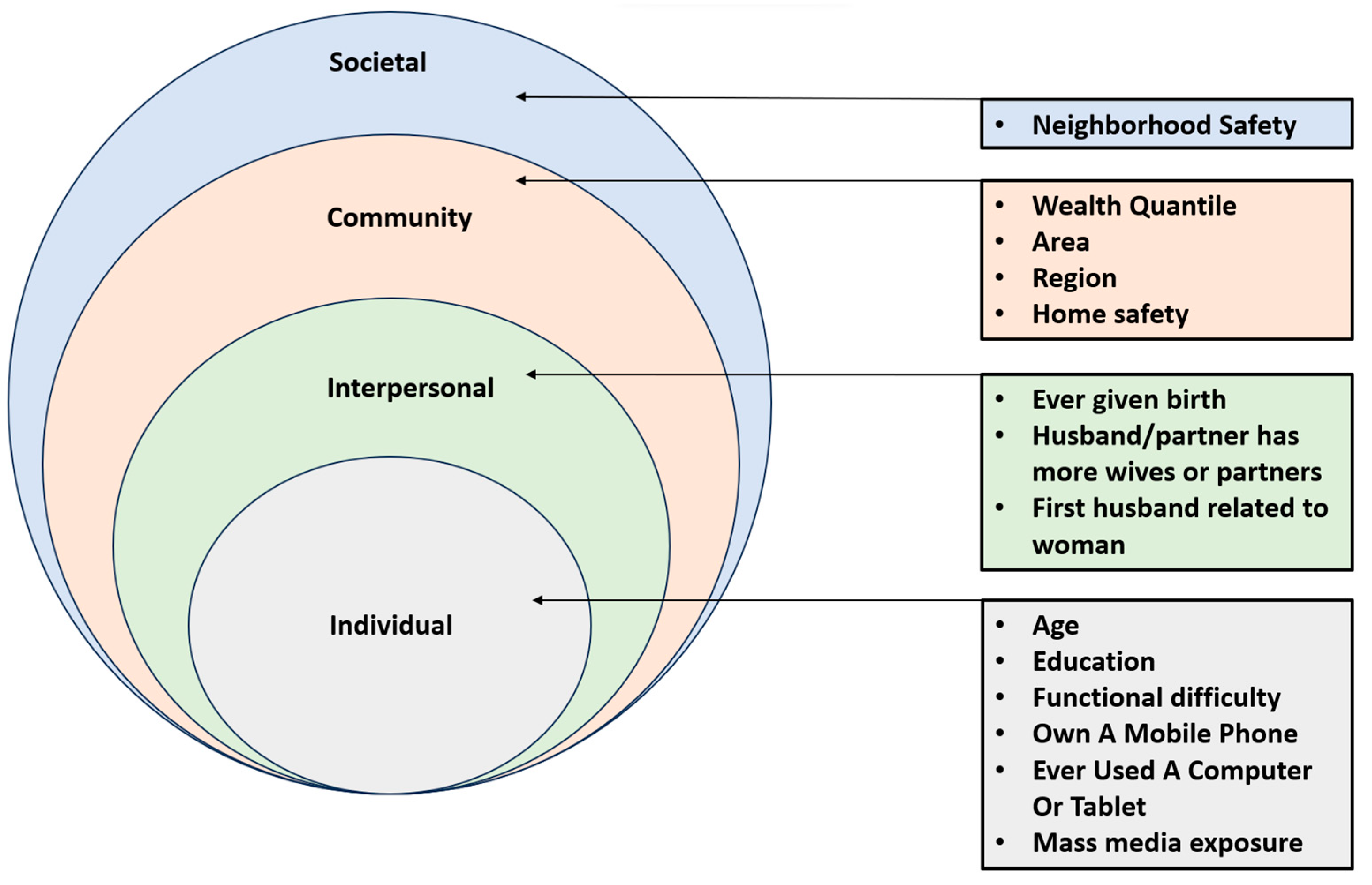

1.2. Theoretical framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Survey

2.2. Study Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

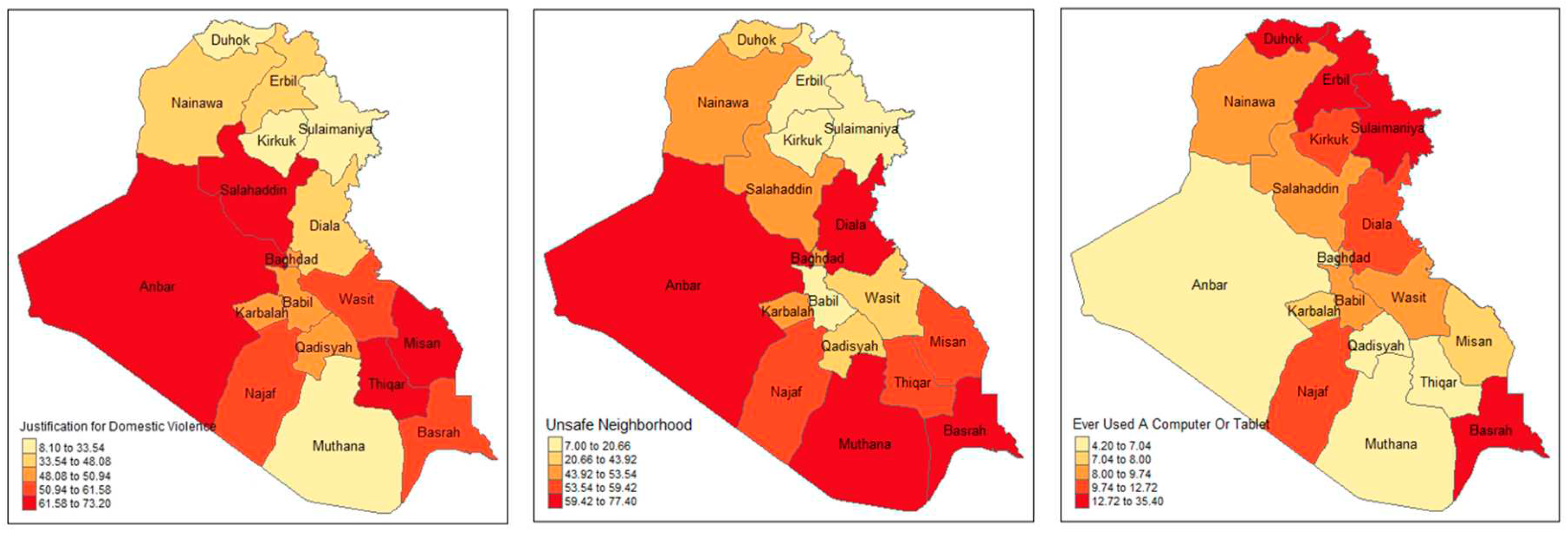

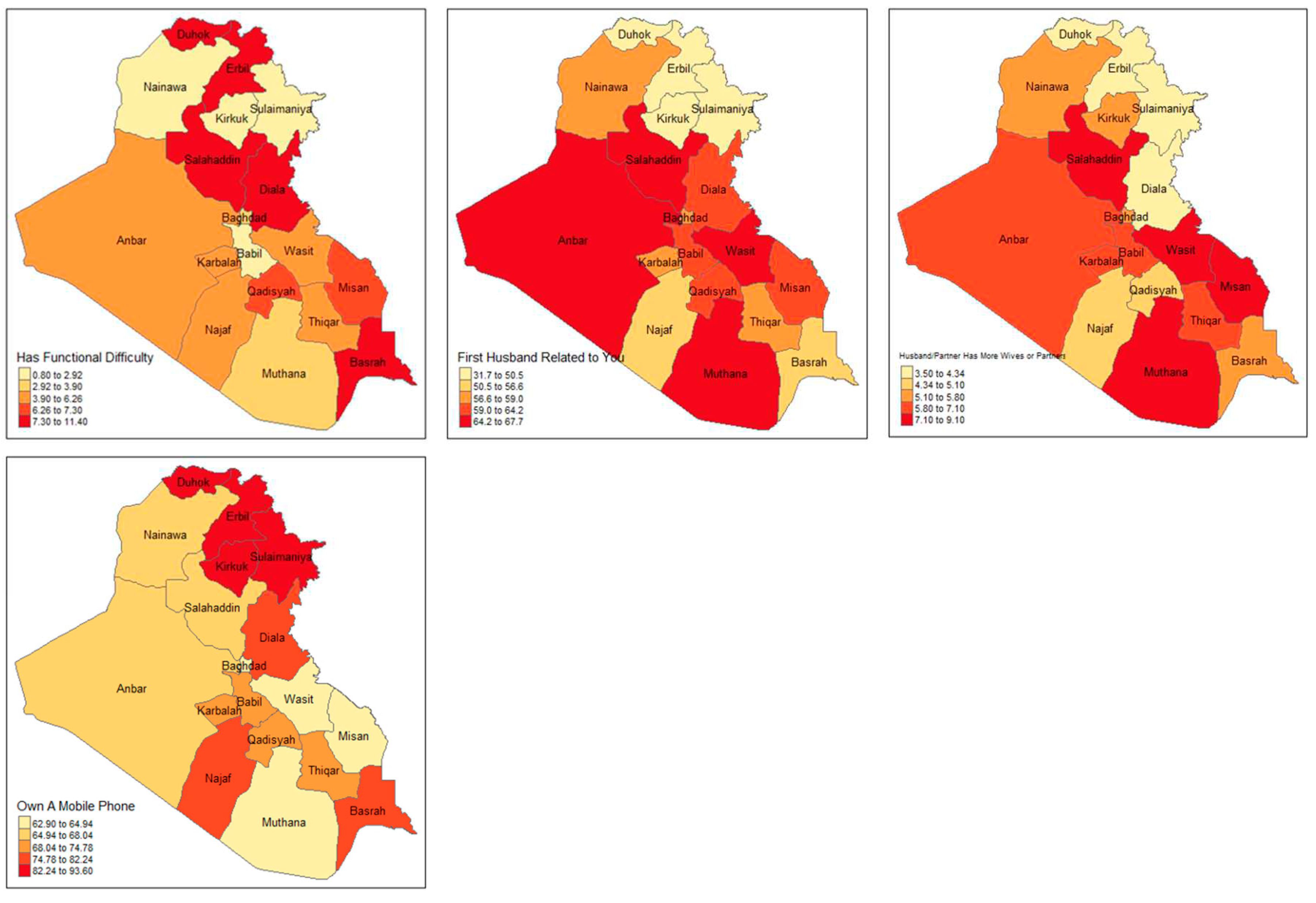

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Logistic Regression Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emberti Gialloreti, L.; et al. Supporting Iraqi Kurdistan Health Authorities in Post-conflict Recovery: The Development of a Health Monitoring System. Front Public Health 2020, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, W. Social Determinants of Health in Countries in Conflict: A Perspective From the Eastern Mediterranean. 2008; Available from: https://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/dsa955.pdf.

- Murthy, R.S.; Lakshminarayana, R. Mental health consequences of war: a brief review of research findings. World Psychiatry 2006, 5, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Green, P.; Ward, T. The Transformation of Violence in Iraq. British journal of criminology 2009, 49, 609–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, J.; Hagan, J. , Crimes of Terror, Counterterrorism, and the Unanticipated Consequences of a Militarized Incapacitation Strategy in Iraq. Social Forces 2018, 97, 309–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congressional Research Service, C. Iraq: Politics, Governance, and Human Rights. 2012; Available from: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA584675.pdf.

- Cordesman, A.H.; et al. , Iraq in crisis. 2014, Center for Strategic and International Studies ; Rowman & Littlefield: Washington, DC, Lanham, MD.

- World Health Organization, W. First gender-based violence strategic plan launched in Iraq. 2022; Available from: https://www.emro.who.int/fr/iraq/news/first-gender-based-violence-strategic-plan-launched-in-iraq.html.

- United Nations, U. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Resolution adopted by the United Nations general assembly on . 2015; Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda. 25 September.

- United Nations, U. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.. 2015; Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

- United Nations, U. Iraq: Prevalence Data on Different Forms of Violence against Women:. 2023.

- United Nations Population Fund, U. , IRAQ Scorecard on Gender-based violence. n.d.

- Iraq Ministry of Planning, I. Planning publishes new statistics and percentages for (11) files related to women and the family in Iraq. 2021; Available from: https://www.ina.iq/144902--11-.html.

- Al-Tawil, N.G. , Association of violence against women with religion and culture in Erbil Iraq: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Atrushi, H.H.; et al. , Intimate partner violence against women in the Erbil city of the Kurdistan region, Iraq. BMC Womens Health 2013, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elghossain, T.; et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence against women in the Arab world: a systematic review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2019, 19, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tappis, H.; et al. Domestic violence among Iraqi refugees in Syria. Health Care Women Int 2012, 33, 285–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Garg, S. Addressing domestic violence against women: an unfinished agenda. Indian J Community Med, 2008, 33, 73–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakovec-Felser, Z. Domestic Violence and Abuse in Intimate Relationship from Public Health Perspective. Health Psychol Res 2014, 2, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour Organization, I. Database of national labour, social security and related human rights legislation: raq (232) > Criminal and penal law (5). 2012; Available from: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_lang=en&p_isn=57206&p_country=IRQ&p_count=232&p_classification=01.04&p_classcount=5.

- Equity Now, E. Discriminatory Laws: Iraq – Penal Code No. 111 Of 1969. 2021; Available from: https://www.equalitynow.org/discriminatory_law/iraq_-_penal_code_no_111_of_1969/#:~:text=The%20Law%3A-,Article%2041%20of%20the%20Iraqi%20Penal%20Code%20No.,while%20exercising%20a%20legal%20right.

- Rueve, M.E.; Welton, R.S. Violence and mental illness. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2008, 5, 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno, C.; et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet 2006, 368, 1260–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, J.; Biswas, R.K. Married Women's Attitude toward Intimate Partner Violence Is Influenced by Exposure to Media: A Population-Based Spatial Study in Bangladesh. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardinha, L.; Catalán, H.E.N. Attitudes towards domestic violence in 49 low- and middle-income countries: A gendered analysis of prevalence and country-level correlates. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0206101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; La Ferrara, E.; Orozco, V. Entertainment, Education, and Attitudes Toward Domestic Violence. AEA papers and proceedings 2019, 109, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delara, M. Mental Health Consequences and Risk Factors of Physical Intimate Partner Violence. Mental Health in Family Medicine 2016, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, J.M. , Intimate Partner Violence as a Risk Factor for Mental Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Family Violence 1999, 14, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayeh, E. The role of empowering women and achieving gender equality to the sustainable development of Ethiopia. Pacific Science Review B: Humanities and Social Sciences 2016, 2, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwamba, E.; et al. Strengthening women's empowerment and gender equality in fragile contexts towards peaceful and inclusive societies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Campbell Syst Rev 2022, 18, e1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidu, A.A.; et al. Mass Media Exposure and Women's Household Decision-Making Capacity in 30 Sub-Saharan African Countries: Analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys. Front Psychol 2020, 11, 581614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, P.; Ward, T. The Transformation of Violence in Iraq. British Journal of Criminology 2009, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson Center, W. Violence Against Women Permeates All Aspects of Life in Iraq. 2022 [cited 2023; Available from: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/violence-against-women-permeates-all-aspects-life-iraq.

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The ecology of developmental processes. 1998.

- Tekkas Kerman, K.; Betrus, P. Violence Against Women in Turkey: A Social Ecological Framework of Determinants and Prevention Strategies. Trauma Violence Abuse 2020, 21, 510–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamdouh, H.M.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors for spousal violence among women attending health care centres in Alexandria, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J 2012, 18, 1118–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, M.; et al. Cross-disciplinary intersections between public health and economics in intimate partner violence research. SSM Popul Health 2021, 14, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Children’s Fund, U. , Iraq: Monitoring the situation of children and women: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2018, 2019. 2019.

- Lansford, J.E.; et al. Attitudes justifying domestic violence predict endorsement of corporal punishment and physical and psychological aggression towards children: a study in 25 low- and middle-income countries. J Pediatr 2014, 164, 1208–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, J.; Biswas, R.K. , Married Women’s Attitude toward Intimate Partner Violence Is Influenced by Exposure to Media: A Population-Based Spatial Study in Bangladesh. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 3447. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, E.; Llewellyn, G. Exposure of Women With and Without Disabilities to Violence and Discrimination: Evidence from Cross-sectional National Surveys in 29 Middle- and Low-Income Countries. J Interpers Violence 2023, 38, 7215–7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, S.; Kotsadam, A. Resources and domestic violence in sub-Saharan Africa. Unpublished manuscript, 2013.

- Riley, A.; et al. Intimate partner violence against women with disability and associated mental health concerns: a cross-sectional survey in Mumbai. India. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, R.; et al. Intimate partner violence against women with disability and associated mental health concerns: a cross-sectional survey in Mumbai. India. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056475. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, T.; et al. Prevalence and Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women With Disabilities in Bangladesh: Results of an Explanatory Sequential Mixed-Method Study. Journal of interpersonal violence 2014, 29, 3105–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, A.; et al. Intimate partner violence against women with disability and associated mental health concerns: a cross-sectional survey in Mumbai, India. BMJ open 2022, 12, e056475–e056475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Population Fund, U. Snapshot | Women with disabilities in Iraq. 2021; Available from: https://iraq.unfpa.org/en/resources/snapshot-women-disabilities-iraq#:~:text=In%20Iraq%2C%2010%25%20of%20the,violence%20and%20reproductive%20health%20services.

- Arënliu, A.; Kelmendi, K.; Bërxulli, D. Socio-demographic associates of tolerant attitudes toward intimate partner violence against women in Kosovo. The Social Science Journal 2021, 58, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainiddinov, H. Contextual Factors Associated With Women's Attitudes Toward Intimate Partner Violence in Tajikistan: Findings From the 2012 and 2017 Demographic and Health Surveys. Violence Against Women 2023, 29, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahinkorah, B.O. Polygyny and intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from 16 cross-sectional demographic and health surveys. SSM - Population Health 2021, 13, 100729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.; et al. Is consanguineous marriage related to spousal violence in India? Evidence from the National Family Health Survey, 2015-16. J Biosoc Sci 2022, 54, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.; et al. Is consanguineous marriage related to spousal violence in India? Evidence from the National Family Health Survey, 2015–16. Journal of Biosocial Science 2022, 54, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, N.; Agadjanian, V. Polygyny and Intimate Partner Violence in Mozambique. Journal of Family Issues 2020, 41, 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, N.B.; Atteraya, M.S. , Polygyny and intimate partner violence (IPV) among Ethiopian women. Global Social Welfare 2021, 8, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arënliu, A.; Kelmendi, K.; Bërxulli, D. Socio-demographic associates of tolerant attitudes toward intimate partner violence against women in Kosovo. The Social Science Journal 2019, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainiddinov, H. Contextual Factors Associated With Women's Attitudes Toward Intimate Partner Violence in Tajikistan: Findings From the 2012 and 2017 Demographic and Health Surveys. Violence Against Women 2022, 29, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenkorang, E.Y.; et al. Factors Influencing Domestic and Marital Violence against Women in Ghana. Journal of Family Violence 2013, 28, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson Center, W. How the Kurds Got Their Way. 2023; Available from: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/how-the-kurds-got-their-way.

- Pinchevsky, G.M.; Wright, E.M. The Impact of Neighborhoods on Intimate Partner Violence and Victimization. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 2012, 13, 112–132. [Google Scholar]

- Creating Safe And Healthy Neighborhoods With Place-Based Violence Interventions. Health Affairs 2019, 38, 1687–1694. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libertun de Duren, N.R. Erratum to "Investigating the links between violence in public and private spaces: A qualitative study of neighborhood upgrading programs and domestic violence in La Paz, Bolivia" [World Development Perspectives 19 (2020) 100231]. World Dev Perspect 2021, 22, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, J. Favela: Four decades of living on the edge in Rio de Janeiro. 2010: Oxford University Press.

- Capili, B. Cross-Sectional Studies. Am J Nurs 2021, 121, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domestic violence acceptance |

Domestic violence acceptance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Total | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | P-Value | |||

| 10029 | 51.6% | 9414 | 48.4% | 19443 | 100% | ||||

| Individual | Age | 15-19 | 533 | 5.31% | 641 | 7% | 1174 | 6.0% | <0.001 |

| 20-24 | 1406 | 14.02% | 1424 | 15% | 2830 | 14.6% | |||

| 25-29 | 1933 | 19.27% | 1721 | 18% | 3654 | 18.8% | |||

| 30-34 | 1774 | 17.69% | 1662 | 18% | 3436 | 17.7% | |||

| 35-39 | 1719 | 17.14% | 1561 | 17% | 3280 | 16.9% | |||

| 40-44 | 1457 | 14.53% | 1323 | 14% | 2780 | 14.3% | |||

| 45-49 | 1207 | 12.04% | 1082 | 11% | 2289 | 11.8% | |||

| Education | Pre-primary or none | 1268 | 12.64% | 2151 | 22.8% | 3419 | 17.46% | <0.001 | |

| Primary | 3893 | 38.82% | 4822 | 51.2% | 8715 | 44.51% | |||

| Lower secondary | 1995 | 19.89% | 1479 | 15.7% | 3474 | 17.74% | |||

| Upper secondary + | 2873 | 28.65% | 962 | 10.2% | 3835 | 19.59% | |||

| Ever used a computer or a tablet | Yes | 1578 | 15.73% | 430 | 4.57% | 2008 | 10.26% | <0.001 | |

| No | 8432 | 84.08% | 8984 | 95.43% | 17416 | 88.95% | |||

| Own a mobile phone | Yes | 8134 | 81.10% | 5953 | 63.24% | 14087 | 71.95% | <0.001 | |

| No | 1892 | 18.87% | 3460 | 36.75% | 5352 | 27.34% | |||

| Functional difficulties | Yes | 400 | 3.99% | 605 | 6.43% | 1005 | 5.13% | <0.001 | |

| No | 9424 | 93.97% | 8563 | 90.96% | 17987 | 91.87% | |||

| Mass Media Exposure | Yes | 9172 | 91.5% | 8576 | 91.1% | 17886 | 91.3% | .415 | |

| No | 854 | 8.5% | 833 | 8.9% | 1702 | 8.7% | |||

| Interpersonal | Ever given birth | Yes | 8980 | 89.54% | 8473 | 90.00% | 17453 | 89.14% | 0.286 |

| No | 1049 | 10.46% | 941 | 10.00% | 1990 | 10.16% | |||

| First husband related to you | Yes | 5078 | 50.63% | 5944 | 63.14% | 11022 | 56.30% | <0.001 | |

| No | 4945 | 49.31% | 3468 | 36.84% | 8413 | 42.97% | |||

| Husband/Partner Has More Wives or Partners | Yes | 448 | 4.47% | 668 | 7.10% | 1116 | 5.70% | <0.001 | |

| No | 9563 | 95.35% | 8737 | 92.81% | 18300 | 93.47% | |||

| Community | Wealth Quantile | Poorest | 1511 | 15.07% | 3052 | 32.42% | 4563 | 23.31% | <0.001 |

| Second | 1809 | 18.04% | 2350 | 24.96% | 4159 | 21.24% | |||

| Middle | 2035 | 20.29% | 1846 | 19.61% | 3881 | 19.82% | |||

| Fourth | 2247 | 22.41% | 1348 | 14.32% | 3595 | 18.36% | |||

| Richest | 2427 | 24.20% | 818 | 8.69% | 3245 | 16.57% | |||

| Area | Urban | 7463 | 74.41% | 5352 | 56.85% | 12815 | 65.45% | <0.001 | |

| Rural | 2566 | 25.59% | 4062 | 43.15% | 6628 | 33.85% | |||

| Region | Kurdistan | 1841 | 18.36% | 573 | 6.09% | 2414 | 12.33% | <0.001 | |

| South/Central Iraq | 8188 | 81.64% | 8841 | 93.91% | 17029 | 86.98% | |||

| Home Safety | Yes | 7107 | 70.9% | 6156 | 65.4% | 13364 | 68.2% | <0.001 | |

| No | 2920 | 29.1% | 3256 | 34.6% | 6229 | 31.8% | |||

| Societal | Neighborhood Safety | Yes | 5716 | 56.99% | 4621 | 49.09% | 10337 | 52.80% | <0.001 |

| No | 4313 | 43.01% | 4793 | 50.91% | 9106 | 46.51% | |||

| 95% CI | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | aOR | Lower | Upper | ||

| Individual | Age Ref= (15-19) | 0.19 | |||

| 20-24 | 0.97 | 0.81 | 1.15 | ||

| 25-29 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 1.05 | ||

| 30-34 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 1.09 | ||

| 35-39 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 1.02 | ||

| 40-44 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 1.03 | ||

| 45-49 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 1.04 | ||

| Education (ref=Preprimary or non) | <0.001 | ||||

| Primary | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.94 | ||

| Lower Secondary | 0.62 | 0.55 | 0.69 | ||

| Upper Secondary+ | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.45 | ||

| Own A Mobile Phone (ref=no) | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.50 | <0.001 | |

| Ever Used A Computer Or Tablet (ref=no) | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.38 | <0.001 | |

| Functional difficulty (ref=no) | 1.60 | 1.40 | 1.83 | <0.001 | |

| Interpersonal | Husband/partner has more wives or partners (ref=no) | 1.51 | 1.33 | 1.72 | <0.001 |

| First husband related to the women (ref=no) | 1.45 | 1.36 | 1.54 | <0.001 | |

| Community | Wealth Quantile (ref=poorest) | <0.001 | |||

| Second | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.91 | ||

| Middle | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.75 | ||

| Fourth | 0.54 | 0.48 | 0.60 | ||

| Richest | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.54 | ||

| Region south central Iraq (ref= Kurdistan) | 2.00 | 1.77 | 2.27 | <0.001 | |

| Area Rural (ref=Urban) | 1.20 | 1.15 | 1.33 | <0.001 | |

| Home Safety (ref=yes) | 0.93 | 0.86 | 1.01 | 0.075 | |

| Societal | Neighborhood Safety (ref=yes) | 1.22 | 1.13 | 1.31 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).