1. Introduction

We are currently in a digital age, with a rampant evolution in new technologies, which are increasingly present in our daily lives. The internet is since then a tool that is part of the routine of individuals, especially in the younger generation (Patrão et al., 2015). Kimberly Young and Mark Griffiths were the first authors to explore the impact that new technologies would have on society, eventually developing the concept of Internet Addiction (Griffiths, 2000; Young, 1996).

According to Young (1999), Internet addiction encompasses a variety of online behaviors that when not able to be regulated are considered pathological such as compulsion to shop or play online games (in which money is invested), excessive surfing of web pages, online video game addiction, and cybersex/pornography.

Having said that, Young (1999) developed an instrument entitled Internet Addiction Test (IAT) consisting of a set of questions such as: “Do you feel worried about the Internet?”; “Do you stay online longer than you initially intended?”; “Do you feel restless, depressed or irritable when you try to cut down or stop using the Internet?”, among others, with the purpose of assessing Internet addiction. According to Young’s (1999) criteria subjects when answering affirmatively to five or more of these questions would be considered dependent users. For Young (1996) and Griffiths (2000), Internet addiction would involve not only spending many hours online, but also compromising the normal functioning of the subject in society, namely uncontrolled and unconscious interactions. However, it should be noted that moderate and controlled internet use does not present significant risks for individuals, since it allows for remote socialization and the creation or strengthening of new relationships (APA, 2013; Griffiths, 2000; Young, 1996).

Research on online addiction has grown internationally and nationally in recent years. The studies already conducted alert to the incidence of cases of young people at risk of online addiction, which implies the continuous and deeper study of explanatory variables of this phenomenon (Patrão, et al., 2016).

A conducted in a partnership between APAV (Portuguese Association for Victim Support) and Geração Cordão to assess online risk behaviours and the impact of internet use on mental health in a sample of young Portuguese through the data presented descriptive and inferential statistics can be concluded which characteristics are associated with a risk profile of technology and internet use in this sample. Young people who present an online and smartphone addiction have as most prevalent characteristics (Patrão et al., 2023):

Young people between 16 and 21 years old, male, attending high school;

No physical exercise;

School performance—students with negative grades;

No loving relationship;

Began online activity at age 8;

Uses screens at night (falls asleep with technology; sleeps with technology at night);

More than six hours per day online;

Makes meals/snacks when is online;

Takes time away from other offline activities to spend more time online (being on the Internet takes time away from: being with family, socializing, studying, to sleep, to date, exercising, to do playful activities);

Sends and receives nudes;

Practices sexting;

Plays online games;

Presents changes in sleep and mood cyberbullying—victim and/or aggressor;

Has more episodes of online discomfort;

Does not talk to anyone when faced with situations of online discomfort;

Phubbing—victim or phubber;

Ghosting—victim and ghost;

Low empathy;

Perception of parenting style—permissive.

In addition to the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) developed by Young (1998b), several instruments allow us to study Internet addiction, such as:

The Internet Addiction Questionnaire (IAQ) (Nyikos et al., 2001) comprised 30 items.

The Internet Addiction Scale (IAS) (Nichols & Nicki, 2004) comprises 31 items.

The Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire (PIUQ) (Demetrovics et al., 2008) consists of 58 items.

The Adolescent Pathological Internet Use Scale (APIUS) (Lei & Yang, 2007) consists of 11 items.

The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS) (Meerkerk et al., 2009) consists of 178 items.

However, in a literature review by Laconi et al. (2014), the most used instrument in studies on this subject is the Internet Addiction Test, with 1096 citations, adding that it is also the most used instrument in different countries. Consulting Scopus reveals that the article containing this instrument has 2911 citations.

It should be noted that this instrument has been adapted to the Portuguese population (Pontes et al., 2014). These are the reasons that led us to choose the IAT.

Therefore, the existence of an instrument to screen for Internet addiction becomes increasingly relevant in clinical practice, so as to prevent online risk behaviors and the impact of Internet use on mental health.

Having said this, that the aim of this study to adapt and evaluate a shortened version of the IAT (Internet Addiction Test) scale completed by young people aged 12 years and older in relation to their online behaviors and risk of online addiction. The psychometric qualities of the reduced version—Screening IAT—young people are presented in order to validate its use in the early detection of online addiction. The following research hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 1: The reduced version of the IAT scale has good psychometric qualities.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

This study involved the voluntary participation of 3021 individuals, and the questionnaire was completed by young people aged between 12 and 25 years old. The study procedures were carried out following the Helsinki Declaration. The ISPA—Instituto Universitário Ethics Committee and the Portuguese Ministry of Education approved the study. Concerning students under 18, their parents signed the informed consent form, giving them permission to participate in the study. It should be noted that contact with these participants was made through their school, which was included in the Geração Cordão program. As for the participants aged over 18, it was they who signed the informed consent form. Therefore, the sampling process was the non-probabilistic, convenient, and intentional snowball type (Trochim 2000).

The online questionnaire contained information about the objective of the study, as well as the confidentiality of the answers. The online questionnaire was composed of sociodemographic questions in order to characterize the sample and the instrument we propose to validate for the Portuguese population. Data collection took place from 2021 to 2022.

2.2. Participants

The sample in this study consisted of 3021 participants, aged between 12 and 25, with an average age of 15 (SD = 3.03). Of these participants, 55.9% were female, and 44.1% were male. For educational qualifications (56.2%) have junior high school, (37.8%) have high school, and (5.9%) have college.

2.3. Data Analysis Procedure

Once the data were collected and the database was created in SPSS Statistics 29 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY., USA), the metric qualities of the one used in this study were tested. The first step was to divide the sample into three parts (20%, 40% and 40%). This decision was made because, when an instrument is to be adapted or reduced, the sample must be large enough to be divided into three parts (Marôco, 2021): with 20% of the sample an exploratory factor analysis must be carried out; with 40% a confirmatory factor analysis; with the remaining 40% another confirmatory factor analysis. The data from approximately 20% of the sample (600 participants) were used to test factor validity by performing an exploratory factor analysis, which aims at discovering and analysing the structure of a set of interrelated variables to build a measurement scale for (intrinsic) factors that somehow (more or less explicitly) control the original variables (Marôco, 2021).

The other two parts (1200 and 1221 participants) were then tested for validity by performing a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for each of the groups using AMOS 29 for Windows software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The procedure followed a logic of “model generation” (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1993), considering in the analysis of their fit, in an interactive way, the results obtained: for the chi-square (χ2) ≤ 5; for the Tucker Lewis index (TLI)> 0.90; for the goodness of fit index (GFI)> 0.90; for the comparative fit index (CFI)> 0.90; for the root mean square error approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.08; and for the root mean square residual (RMSR), a smaller value corresponds to a better adjustment (McCallum et al., 1996). Obtaining a good fit for both measurement models becomes essential to establish the convergent validity of each model and verify the risks associated with common variance methods (Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, when Cronbach’s alpha value is above 0.70, AVE values greater than 0.40 are acceptable, indicating good convergent validity (Hair et al., 2011).The invariance analysis between the two groups randomly selected from the whole sample was also performed. Then, its internal consistency was tested by calculating Cronbach’s alpha and, finally, the sensitivity study by calculating measures of central tendency such as the median, asymmetry and kurtosis, as well as the minimum and maximum for each item.

The effect of sociodemographic variables on Internet addiction was also tested. A Student’s t-test for independent samples was used for gender, and a parametric ANOVA One Way test was used for schooling. The association between age and Internet addiction was studied using Pearson’s correlations. We then created Internet addiction scores and tested whether gender and schooling were independent of Internet addiction.

2.3. Instrument

The instrument used in this study is a reduced version of the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) developed by Young (2011) and adapted to the Portuguese population by Pontes et al. (2014). The initial instrument is composed of 20 items, measured on a 6-point Likert scale (‘does not apply’ (0), ‘rarely’ (1), ‘occasionally’ (2), ‘frequently’ (3), ‘often’ (4), and ‘always’ (5). Only seven items were used in this study, considering the items that presented higher factor weights both in the Portuguese version and subsequent studies. The following items were used: 1, 8, 13, 15, 18, 19 and 20. In this study, they were numbered between 1 and 7 (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Items of the short version of the instrument.

Table 1.

Items of the short version of the instrument.

| Numbering in the 20-item scale |

Numbering on the 7-item scale |

How often… |

| 1 |

1 |

Do you find that you stay on-line longer than you intended? |

| 8 |

2 |

Does your job performance or productivity suffer because of the Internet? |

| 13 |

3 |

Do you snap, yell, or act annoyed if someone bothers you while you are on-line? |

| 15 |

4 |

Do you feel preoccupied with the Internet when off-line, or fantasize about being on-line? |

| 18 |

5 |

Do you try to hide how long you’ve been on-line? |

| 19 |

6 |

Do you choose to spend more time on-line over going out with others? |

| 20 |

7 |

Do you feel depressed, moody, or nervous when you are off-line, which goes away once you are back on-line? |

3. Results

3.1. Validity, reliability and sensitivity of the instrument

To perform the factorial analysis, the total sample was randomly divided into three samples. In the first sample 600 participants were extracted, in the second 1200 participants and in the third 1221 participants.

An exploratory factor analysis was performed with the first sample. The initial exploratory factor analysis showed that the scale is composed of a single factor (unidimensional), with a KMO of 0.86, which can be considered good (Sharma, 1996), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at p < 0.001, being acceptable values to continue the analysis, as well as an indicator that the data are from a multivariate normal population (Pestana & Gageiro, 2003). The factor structure of this scale is based on a factor that explains 51% of the total variability of the scale. All items had factor weights above 0.50 (

Table 2). As for internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83.

Table 2.

Item Loadings.

| |

How often… |

Loadings |

| 1 |

Do you find that you stay on-line longer than you intended? |

0.55 |

| 2 |

Does your job performance or productivity suffer because of the Internet? |

0.68 |

| 3 |

Do you snap, yell, or act annoyed if someone bothers you while you are on-line? |

0.73 |

| 4 |

Do you feel preoccupied with the Internet when off-line, or fantasize about being on-line? |

0.76 |

| 5 |

Do you try to hide how long you’ve been on-line? |

0.71 |

| 6 |

Do you choose to spend more time on-line over going out with others? |

0.71 |

| 7 |

Do you feel depressed, moody, or nervous when you are off-line, which goes away once you are back on-line? |

0.83 |

In the subsequent confirmatory factor analysis, carried out with a sample of 1200 participants, the adjustment indexes obtained proved to be adequate (χ2/gl = 2.93; GFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.040; SRMR = 0.029). The internal consistency presents a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84. It also shows good construct reliability with a value of 0.85 and convergent validity with a value of 0.45.

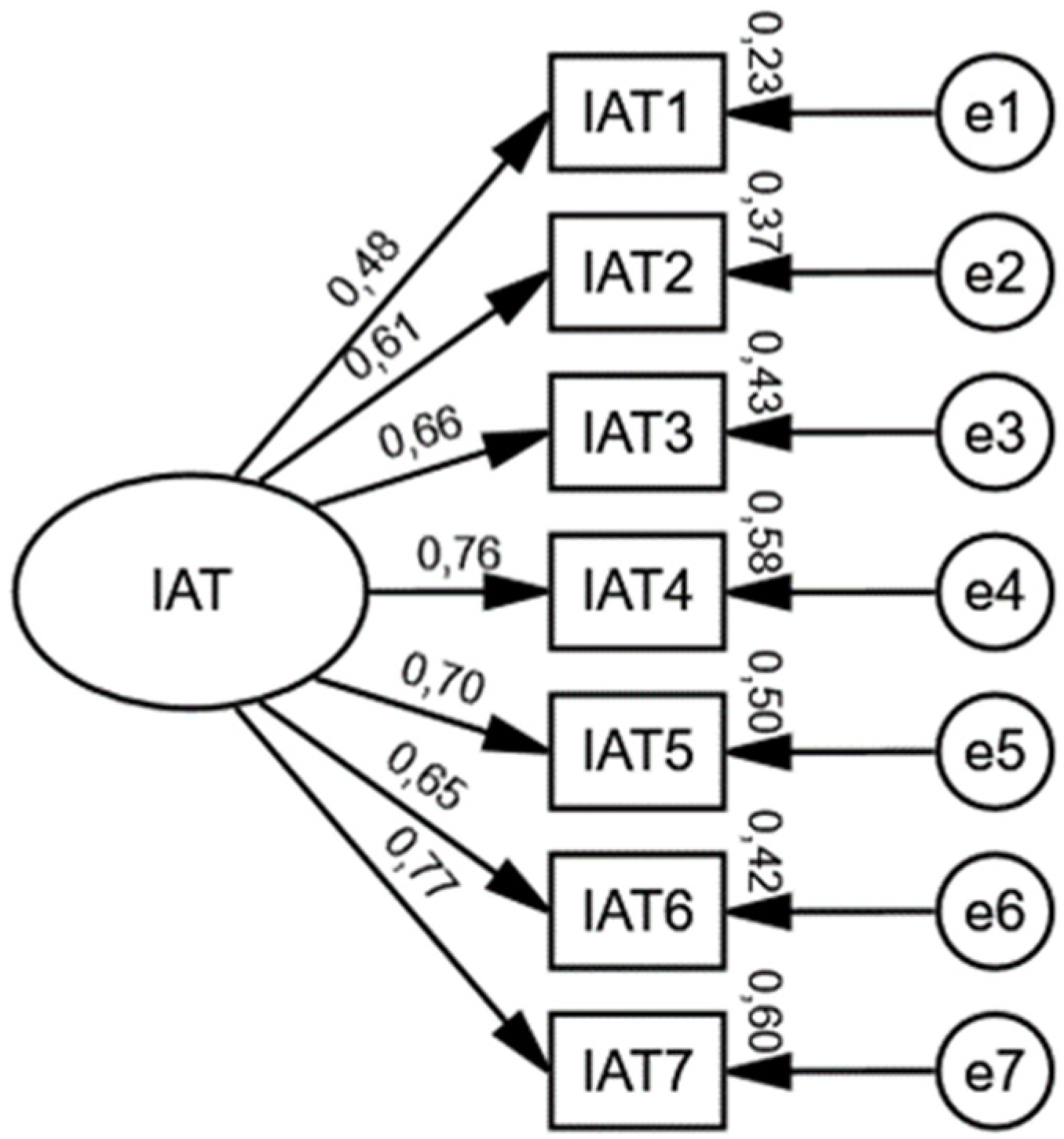

Figure 1 shows the factorial weights, as well as the individual reliability of each of the items of the sample with 1200 participants.

Figure 1.

Factorial weights and individual reliability of each of the items of the sample with 1200 participants.

Figure 1.

Factorial weights and individual reliability of each of the items of the sample with 1200 participants.

Concomitantly, in the confirmatory factor analysis, carried out with a sample of 1221 participants, the adjustment indexes obtained were adequate (χ2/gl = 2.97; GFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.040; SRMR = 0.025). It also shows good construct reliability with a value of 0.82 and convergent validity with a value of 0.40.

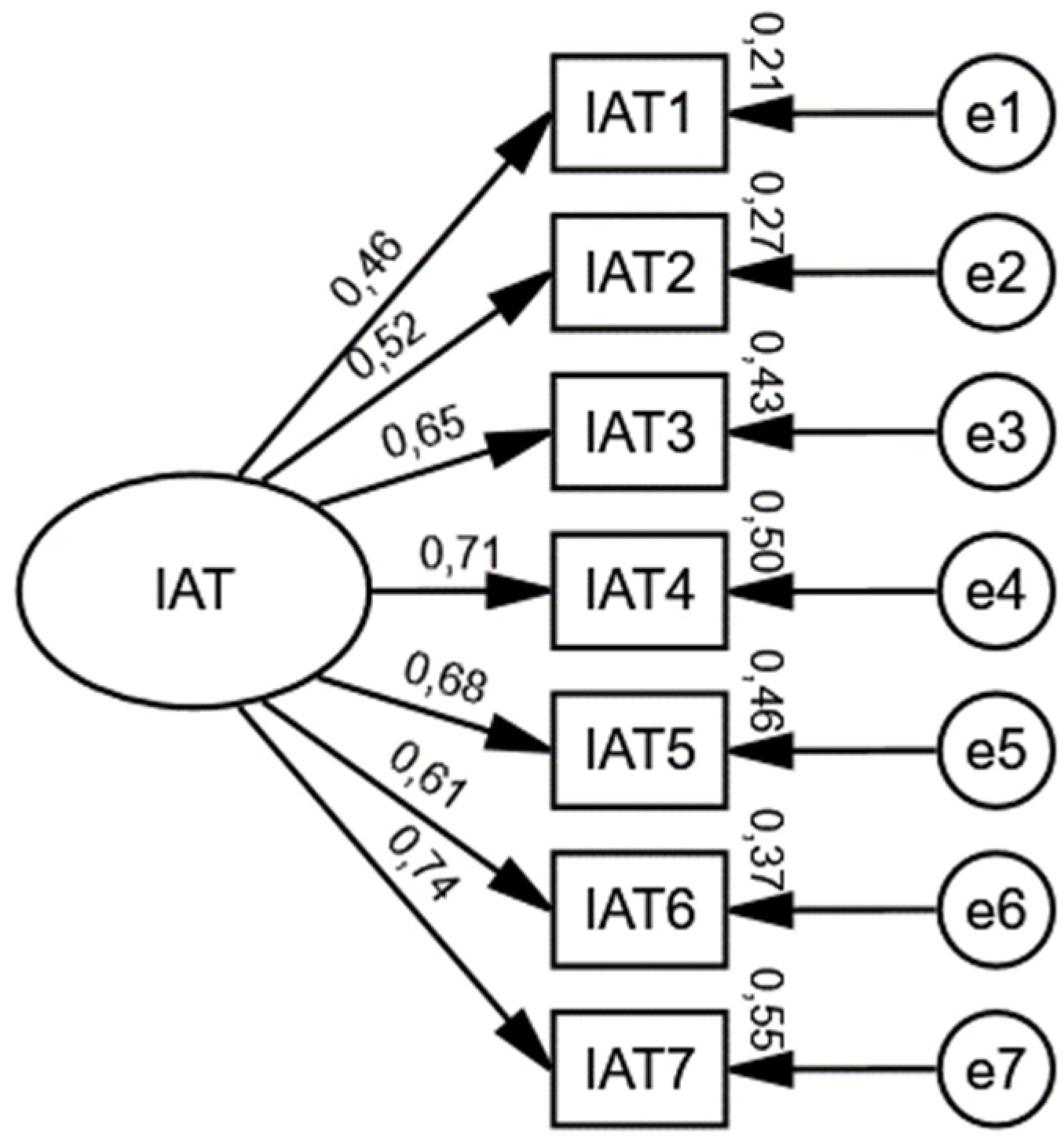

Figure 2 presents the factorial weights and the individual reliability of each item of the sample with 1221 participants.

Figure 2.

Factorial weights and individual reliability of each of the items of the sample with 1221 participants.

Figure 2.

Factorial weights and individual reliability of each of the items of the sample with 1221 participants.

Next, the invariance of the Internet Addiction Test model in boys and girls was tested and assessed by comparing the free model (with factor weights and variances/covariances of the free factors) with the construct model in which factor weights and variances/covariances of both groups were fixed. The significance of both models was measured using the Chi-square test described by Marôco (2021). The restricted model, with factorial weights and variances/covariances fixed between the two groups, did not show a significantly worse fit than the model with free parameters (∆χ 2λ(6) = 18.12; p = 0. 229), which indicates us the invariance of the measurement model of the Internet Ad-diction Test between boys and girls. We also found that the intercepts are in-variant (∆χ 2i(7) = 10.768; p = .149), which indicates that we are looking at a model with strong invariance.

The scale’s internal consistency was tested among the 3021 participants, obtaining a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83.

Concerning item sensitivity, it was found that none of the items has a median close to one of the extremes, all items have responses in all points, and their absolute values of skewness and kurtosis are below 3 and 8, respectively (

Table 3), which indicates that they do not grossly violate normality (Kline, 2011).

Table 3.

Measurement of central tendency, skewness and kurtosis of the items.

Table 3.

Measurement of central tendency, skewness and kurtosis of the items.

| |

Median |

Skewness |

Std. Error of Skewness |

Kurtosis |

Std. Error of Kurtosis |

Minimum |

Maximum |

|

| Do you find that you stay on-line longer than you intended? |

3.00 |

-0.282 |

0.045 |

-0.548 |

0.089 |

0 |

5 |

|

| Does your job performance or productivity suffer because of the Internet? |

2.00 |

0.652 |

0.045 |

0.062 |

0.089 |

0 |

5 |

|

| Do you snap, yell, or act annoyed if someone bothers you while you are on-line? |

1.00 |

1.106 |

0.045 |

1.067 |

0.089 |

0 |

5 |

|

| Do you feel preoccupied with the Internet when off-line, or fantasize about being on-line? |

1.00 |

1.265 |

0.045 |

1.983 |

0.089 |

0 |

5 |

|

| Do you try to hide how long you’ve been on-line? |

1.00 |

1.090 |

0.045 |

0.990 |

0.089 |

0 |

5 |

|

| Do you choose to spend more time on-line over going out with others? |

1.00 |

1.034 |

0.045 |

0.765 |

0.089 |

0 |

5 |

|

| Do you feel depressed, moody, or nervous when you are off-line, which goes away once you are back on-line? |

1.00 |

1.249 |

0.045 |

1.679 |

0.089 |

0 |

5 |

|

3.2. Prevalence of Internet addiction in the sample

According to Young (1998b), the IAT instrument, composed of 20 items, distinguished three types of users according to the different levels of Internet use. To this end, she created three cut-off points: 20-39 = average user; 40-69 = a person who has frequent problems due to their internet use; 70-100 = internet addicts. Halley et al. (2014) used the same cut-off points in their adaptation to the Portuguese population. However, as the reduced version proposed in this study is composed of only seven items, the proposed cut-off points are 0-11 = low risk of addiction; 12-19 = moderate risk of addiction; 20-35 = high risk of addiction.

According to the cut-off criteria proposed by us, 1710 (56.6%) of the participants in this study showed a low risk of Internet addiction, 1051 (34.8%) a moderate risk of Internet addiction and 260 (8.6%) a high risk of Internet addiction.

3.3. Effect of socio-demographic variables on Internet Addiction

Finally, the effect of socio-demographic variables on Internet Addiction was tested. A Student’s t-test for independent samples was used for gender. Female participants were found to have higher levels of internet addiction than male participants (

Table 4). However, these differences are not statistically significant (t (3019) = 0.90; p = 0.364; d = 0.03).

The One Way ANOVA parametric test was used for level of education. The participants with junior high school education revealed higher levels of Internet addiction, followed by those with high school education and, finally, those attending college (

Table 4). Nevertheless, these differences are not statistically significant (F (3, 3018) = 0.51; p = 0.600).

Table 4.

Effect of socio-demographic variables on Internet Addition.

Table 4.

Effect of socio-demographic variables on Internet Addition.

| Variable |

Mean |

SD |

| Gender |

Female |

11.34 |

5.70 |

| Male |

11.14 |

6.00 |

| Education |

Junior high school |

11.32 |

6.28 |

| High School |

11.20 |

5.24 |

| College |

10.88 |

4.97 |

Table 5.

Correlation between Age and Internet Addiction.

Table 5.

Correlation between Age and Internet Addiction.

| |

Age |

Internet Addiction |

| Age |

Pearson Correlation |

-- |

|

| N |

3021 |

|

| Internet Addiction |

Pearson Correlation |

-,036*

|

-- |

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

,046 |

|

| N |

3021 |

3021 |

The results show that age is negatively and significantly associated with Internet addiction (r = −0.036; p = 0.046), which means that younger participants show greater Internet addiction (

Table 5).

It was then tested whether sociodemographic variables were independent of internet addiction. To this end, the chi-squared test of independence was used.

The percentage of female participants with low risk of Internet addiction is similar to the percentage of males, as well as for the moderate risk of Internet addiction. However, the percentage of participants with a high risk of Internet addiction is higher in female participants when compared with male participants (

Table 6). The chi-squared test (ꭓ2 (2) = 1.18; p = 0.555; V = 0.02) suggested that the two variables are independent.

Table 6.

Gender x IAT crosstab.

Table 6.

Gender x IAT crosstab.

| |

Gender |

Total |

| Female |

Male |

|

| IAT |

Low risk of addiction |

961 |

749 |

1710 |

| 56,9% |

56,3% |

56,6% |

| Moderate risk of addition |

577 |

474 |

1051 |

| 34,1% |

35,6% |

34,8% |

| High risk of addiction |

152 |

108 |

260 |

| 9,0% |

8,1% |

8,6% |

| Total |

1690 |

1331 |

3021 |

| 100,0% |

100,0% |

100,0% |

When testing the independence between the risk of Internet addiction and the level of the school, it was found that these variables are not independent (ꭓ2 (4) = 16.07; p = 0.003; V = 0.07) that are the youngsters attending university who have a higher percentage of low risk of Internet addiction. However, they have the lowest percentage of moderate and high risk of internet addiction. The participants that are in secondary school are the ones that have a higher percentage of moderate risk of Internet addiction. As for the high risk of Internet addiction, the participants in primary schools are revealed to have a higher percentage (

Table 7).

Table 7.

Education x IAT crosstab.

Table 7.

Education x IAT crosstab.

| |

Education |

Total |

| Junior high School |

High School |

College |

| IAT |

Low risk of addiction |

945 |

651 |

114 |

1710 |

| 55,6% |

57,0% |

63,7% |

56,6% |

| Moderate risk of addition |

580 |

416 |

55 |

1051 |

| 34,1% |

36,4% |

30,7% |

34,8% |

| High risk of addiction |

174 |

76 |

10 |

260 |

| 10,2% |

6,6% |

5,6% |

8,6% |

| Total |

1699 |

1143 |

179 |

3021 |

| 100,0% |

100,0% |

100,0% |

100,0% |

4. Discussion

The main objective of this study was to validate a reduced version of the instrument developed by Young (2011) and adapted for the Portuguese population by Halley et al. (2014), consisting of 20 items. This instrument measures internet addiction. The version proposed in this article is a reduced version, composed of 7 items, which will be applied to young people attending primary schools, secondary school and higher education. We chose the items that are consistent with the general criteria of Internet addiction (e.g., tolerance, mood change, interpersonal conflict) and that, in addition, both in the version adapted to the Portuguese population and in subsequent studies, presented higher factor weights. This selection was reinforced by the assessment performed by one of the researchers of this study in her clinical practice, who detected these items as the most relevant.

As previously mentioned, the sample of this study is composed of 3021. For scale validation, the sample was divided into three parts. An exploratory factor analysis was performed with 600 participants and obtained a good KMO value (Sharma, 1996), total variance explained greater than 0.50 and all items having factor weights greater than 0.50.

The other parts into which the sample was divided consisted of 1200 and 1221 participants. Two one-factor confirmatory factor analyses were carried out with these two samples. The adjustment indexes obtained are all adequate (McCallum et al., 1996). They show good construct reliability, although convergent validity is slightly below 0.50. However, when Cronbach’s alpha value is above 0.70, AVE values greater than 0.40 are acceptable, indicating good convergent validity (Hair et al., 2011).

Finally, we randomly divided the whole sample into two parts to perform a gender invariance analysis, which confirmed that we are in front of a model with strong invariance.

Regarding the internal consistency, the scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83, which can be considered good (Bryman and Cramer, 2003). All items showed a good sensitivity, which indicates that they can discriminate subjects.

The effect of sociodemographic variables oninternet addiction shows us that female participants revealed a higher internet addiction than male participants, which may be related to the social networks consumption profile, associated with the female gender, and more normalised, as it is a source of contact with the other, of socialisation. These results align with some authors, such as Laconi et al. (2015), who found that girls are more likely to experience online addiction than boys. However, boys may experience more problems with online games, while girls prefer social networks (Andreassen et al., 2016).

Concerning the level of education, the participants who are in primary schools are the ones who have higher levels of Internet addiction.This result is related with self-control of behaviour and emotions difficulties during the youth development. Throughout school career and the different demands and challenges, an increasing learning curve of self-control of behaviour and emotions can be expected.

Concerning age, there was a negative and significant correlation between age and Internet addiction. These results are in line with the study carried out by Karacic and Oreskovic (2017), who tells us that the age at which they found the highest internet addiction was among young people aged between 15 and 16 (our sample is composed of participants aged between 12 and 25).

The main limitation of this study is the fact that it is a self-report instrument and that we are dealing with participants over 12 years of age, since in this area of Internet addiction, from a clinical point of view, young people tend to perceive that contact, and acceptable use of technology has been made, without assessing the impact on their daily functioning (e.g., impact on sleep routines, eating, studying). It should be noted that young people at this age are often unaware of their dependence on the internet.

Another limitation of this study was the small number of sociodemographic questions included in the questionnaire. As in previous studies, among other questions, it would have been interesting to ask about the frequency and duration of time spent on the internet.

Another suggestion is to recommend that parents read the “Practical guide to the healthy use of technology” developed by the project of Geração Cordão (Patrão, 2021).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of the metric qualities of this instrument indicate that it may be used in future empirical studies and clinical and educational settings to assess the risk of online addiction. Thus, we have a shorter instrument available, which is very important for the population for which it is intended since we know that young people often need more time to answer very long instructions. For this young population, the instrument to which they must respond must be short.

Furthermore in its reduced version, this instrument is useful as a screening to test, for a quick and efficient detection of situations of moderate risk to allow a preventive intervention with the young person, the family and the school context.

References

- (Andreassen et al., 2016) Andreassen, Cecilie Schou, Joël Billieux, Mark D. Griffiths, Daria J. Kuss, Zsolt Demetrovics, Elvis Mazzoni, & Ståle Pallesen. 2016. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30 (2), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000160. [CrossRef]

- (APA, 2013) American Psychiatric Association [APA]. 2013. Diagnostic and sta-tistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- 3(Bryman and Cramer, 2003) Bryman, Alan, and Duncan Cramer. 2003. Análise de dados em ciências sociais. Introdução às técnicas utilizando o SPSS para windows, 3rd ed. Oeiras: Celta.

- (Demetrovics et al., 2008) Demetrovics, Zsolt, Beatrix Szeredi, and Sándor Rozsa. 2008. The three-factor model of Internet addiction: The development of the Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire. Behavior Research Methods, 40(2), 563–574.

- (Griffiths, 2000) Griffiths, Mark D. 2000. Internet addiction-time to be taken seriously?. Addiction Research, 8(5), 413-418. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066350009005587. [CrossRef]

- (Hair et al., 2011) Hair, J., Ringle, C. and Sarstedt, M. 2011. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19, 139-151. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202. [CrossRef]

- (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 1993) Jöreskog, Karl G., and Dag Sörbom. 1993. LISREL8: Structural Equation Modelling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Chicago: Scientific Software International.

- (Karacic and Oreskovic, 2017) Karacic, Silvana, and Stjepan Oreskovic. 2017. Internet Addiction Through the Phase of Adolescence: A Questionnaire Study. JMIR Ment Health, 4(2):e11. DOI: 10.2196/mental.5537. [CrossRef]

- (Kline, 2011) Kline, Rex B. 2011. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- (Laconi et al., 2015) Laconi, Stéphanie, Nathalie Tricard, & Henri Chabrol. 2015. Differences between specific and generalized problematic Internet uses according to gender, age, time spent online and psychopathological symptoms. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.006. [CrossRef]

- (Laconi et al., 2014) Laconi, Stéphanie, Rachel Florence Rodgers, and Henri Chabrol. 2014. The measurement of Internet addiction: A critical review of existing scales and their psychometric properties. Computers in Human Behavior, 41, 190-202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.026. [CrossRef]

- (Lei and Yang, 2007) Lei, Li, and Yang Yang. 2007. The development and validation of adolescent pathological Internet use scale. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 39(4), 688–696.

- (Marôco, 2021) Marôco, João (2021). Análise Estatística com o SPSS Statistics. 8ª edição. Pêro Pinheiro: ReportNumber, Lda.

- (McCallum et al., 1996) McCallum, R.; Browne, M.; Sugawara, H. 1996. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structural modelling. Psychological Methods, 1, 130–149.

- (Meerkerk et al., 2009) Meerkerk, Gert-Jan, Regina J. J. M. Van Den Eijnden, Ad A. Vermulst, & Henk F. L. Garretsen. 2009. The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS): Some psychometric properties. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 12(1), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- (Nichols and Nicki, 2004) Nichols, Laura A., and Richard Nicki. 2004. Development of a psychometrically sound Internet Addiction Scale: A preliminary step. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18, 381–384. [CrossRef]

- (Nyikos et al. 2001) Nyikos, Eva, Beatrix Szeredi, and Zsolt Demetrovics 2001. A new behavioral addiction: The personality psychological correlates of Internet use. Pszichoterapia, 10, 168–182.

- (Patrão 2021) Patrão, Ivone. 2021. Guia Prático para um Uso Saudável da Tecnologia, Geração Cordão. Pactor, Lisboa. https://m.pactor.pt/en/catalogue/teaching-education-sciences/education/pack-guia-pratico-para-um-uso-saudavel-da-tecnologia-geracao-cordao/.

- (Patrão et al., 2023) Patrão, Ivone, Borges, Inês, Estrela, R., & Moreira, Ana. 2023. Comportamentos Online de Risco, Cibersegurança e Saúde Mental numa Amostra de Jovens Portugueses. Relatório parceria Geração Cordão/APAV (www.geracaocordao.com; www.apav.pt).

- (Patrão et al., 2015) Patrão, Ivone, Machado, M., Fernandes, P., & Leal, Isabel. 2015. Jovens e Internet: Relação entre o bem-estar, isolamento social e funcionamento familiar. In Mata, Lurdes, Peixoto, Francisco, Morgado, José, Silva, José, & Monteiro, Vera (org.), Atas do 13º Congresso de Psicologia e Educação (pp. 241-249). Lisboa: ISPA-IU.

- (Patrão et al., 2016) Patrão, Ivone, Reis, J., Madeira, L., Paulino, M., Barandas, R., Sampaio, D., Moura, B., Gonçalves, J., Carmenates, S. 2016. Avaliação e intervenção terapêutica na utilização problemática da internet (UPI) em jovens: revisão da literatura. Revista de Psicologia da Criança e do Adolescente, 7(1-2), 221-242. http://hdl.handle.net/11067/3514.

- (Pestana and Gageiro, 2003) Pestana, Maria Helena, and Gageiro, João Nunes. 2003. Análise de Dados para Ciências Sociais – A complementaridade do SPSS (3ª ed.). Lisboa: Edições Sílabo.

- (Podsakoff et al., 2003) Podsakoff, Phillip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong Y. Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879–903. [CrossRef]

- (Pontes et al. 2014) Pontes, Halley M., Patrão, Ivone M., & Griffiths, Mark D. 2014. Portuguese validation of the Internet Addiction Test: An empirical study. Journal of behavioral addictions, 3(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.3.2014.2.4. [CrossRef]

- (Sharma, 1996) Sharma, Subhash. 1996. Applied Multivariate Techniques. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

- (Trochim, 2000) Trochim, William. 2000. The Research Methods Knowledge Base, 2nd ed. Cincinnati: Atomic Dog Publishing.

- (Young, 1996) Young, Kimberly S. 1996. Psychology of computer use: Addictive use of the Internet: A case that breaks the stereotype. Psychological Reports, 79, 899-902. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1996.79.3.899. [CrossRef]

- (Young, 1998b)Young, Kimberly S. 1998b. Caught in the Net: How to recognize the signs of Internet addiction. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- (Young, 1999) Young, Kimberly S. 1999. Caught in the Net: How to recognize the signs of Internet addiction and a winning strategy for recovery. New York: Wiley.

- (Young, 2011)Young, Kimberly S. 2011. Clinical assessment of internet-addicted cli ents. In K. Young & C. Abreu (Eds.), Internet addiction: A handbook and guide to evaluation and treatment (pp. 19–34). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).