1. Introduction

The symmetry of the face, the shape of the nose, the eyes, the teeth, and the tissues around the teeth, such as the gums, lips, and cheeks, have historically been seen to be the most significant aspects [1]. Dental appearance involves the gingival display and location of the upper lip in addition to the color, size, shape, and placing of the teeth. Therefore, despite having a healthy dentition, excessive gingival display can often damage and worsen a patient's oral and facial

esthetics [2] .

The health of adolescents and young adults,

particularly females, is significantly impacted by oral and facial aesthetics,

which affects how they see their bodies and their sense of self [3]. Oral characteristics have a significant

influence on these young people' bio-psychosocial behavior [4]. Oro-facial characteristics have a considerable

effect on how people portray themselves, how their oral health is affected, and

how they interact with others on a social level [3,4].

This is especially true for women. In contrast to those with oral diseases, who

display a poor body image and a higher level of isolation, females with

superior oro-facial esthetics are viewed as more attractive and have a better

social influence [5]. It has been asserted

that facial features, particularly oral aesthetics, have the potential to

affect how young females perceive themselves, particularly during the period of

life when there is a lot of social and affective interaction, despite the lack

of reliable evidence that this can have a long-term negative impact on

psychosocial wellbeing [6].

Physical beauty is a significant social

relationship component for young women. Thus, aesthetic changes to the face may

be recognized by oneself and may have an impact on one's quality of life [7]. For instance, among young adults in Finland,

improving dental appearance and attitudes about malocclusion were the main

drivers for orthodontic treatment [8].

Teenagers in a Brazilian research who had undergone orthodontic treatment

reported better oral health outcomes when they could smile, laugh, and display

their teeth without feeling self-conscious [9].

As an esthetic smile becomes a more important part

of what it means to be beautiful, more people are being encouraged to seek

corrective and cosmetic operations. The attractiveness and aesthetics of a

smile depend on a number of factors [10].

Esthetic perception can vary depending on cultural, socioeconomic,

environmental, and personal factors like experience and education level [11]. Previous research has indicated that people

find a smile to be more attractive when there is less gingival display (GD),

with dental professionals being more critical of gingival presentation than

laypeople [12]. The optimal GD is between 1

and 3 mm, according to research by numerous authors. While there are numerous

factors that can affect how appealing a smile seems, excessive GD (EGD), also

known as a gummy smile, is one of the primary problems associated with an

unsatisfactory dental smile and is regarded as a crucial element in smile

analysis [13]. EGD is defined as a full,

vivacious smile with an excess of more than 2-4 mm of gingival show. This may

be more noticeable if the lips are hypermobile. At least 50% of patients have

some form of GD in a typical smile. Up to 76% of all patients, nevertheless,

could exhibit exaggerated or forced smile patterns [14,15].

The gingival margin of the anterior central incisors and the inferior border of

the upper lip should be separated by 1-2 mm in a "normal" smile. In

contrast, an excessive gingiva-to-lip distance of 4 mm or more is seen as

"unattractive" by both laypeople and general dentists [16,17].

Gingival enlargements, bony maxillary excess,

insufficient maxillary lip length, hypermobile upper lip, and excessive bone in

the maxilla are just a few of the possible etiologies for EGD. The therapeutic

approach should therefore be centered on the main etiology or the combination

of etiologies found in each case [13-17]. During a dynamic smile, the upper lip

should move somewhere between 4-6 millimeters from rest. Lip translation from

the relaxed posture to the largest smile position, used in clinical examination,

can detect hypermobile upper lips [18]. One

treatment option to address this excessive translation is lip repositioning

surgery (LRS), a predictable surgical procedure [17].

In order to start improving a patient's smile, dental professionals must first

accurately diagnose the etiology before undertaking any kind of treatment. Lip

repositioning surgery is a cosmetic operation that reduces the elevator pull

muscles, which lift the upper lip, to remedy a gummy smile [18]. In order to maintain the top lip near to your

teeth and reduce the amount of exposed gum, the surgery limits how high the

upper lip can rise when you smile. Under local anesthetic, the procedure

entails making two incisions beneath the point where your gums and upper lip

converge. Between these two incisions, a flap of gum tissue is excised, and the

upper and lower parts are stitched together [19].

Only 3–4 days are normally required for recovery time. LRS often has a very low

risk of infection, bleeding, and pain compared to other surgical procedures [20]. Bruising, swelling, and soreness can occur in

some people, but these adverse effects are typically mild. Scars are typically

concealed in the mouth. Few case papers have recently discussed the modified

LRS procedure, although several have recently documented the standard LRS

technique for treating the EGD [13-20].

The perception of facial and dental esthetic has

been studied using a variety of methods [21].

Patients receiving orthodontic or prosthodontic treatment frequently report

their perceptions of orofacial attractiveness using the orofacial esthetic

questionnaire (OEQ) [22]. The OEQ is utilized

in the current study to investigate and assess how patients who underwent LRS

with traditional and modified techniques felt about their own oral and facial

aesthetics at different points after their surgery. The null hypothesis asserts

that there are no variations between the patients' perceptions of their face

and oral esthetics at the various postoperative intervals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) and

Institutional Committee of Research Ethics of King Saud University in Riyadh,

Saudi Arabia, approved the study for ethical considerations (permission number:

E-18-113207). The 2013 revision of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration was followed

when conducting the study. Prior to their enrolment, all participants provided

their informed permission.

2.2. Selection and Calculation of Sample Sizes

The G Power software determined the final sample

size of 200 patients with a confidence level of 95% and a moderate effect size,

with 100 patients in each of the control and test groups.

2.3. Subjects, Study Design, and Setting

A sample of 200 young Saudi female adult patients

who wished to have lip repositioning surgery to reduce their excessive gingival

presentation were solicited to participate in the study and were subsequently

recruited from July 2014 to April 2016. The present study is an extension of

the previously published randomized controlled trial [17].

The communication was tailored to each participant

after selecting an appropriate target population for the study and included all

pertinent information regarding the measures and associated clinical parameters

of the suggested surgical procedures, as well as the study's objectives,

design, risks, and potential benefits. The principal investigator made contact

with the study's intended audience and requested their participation.

The consenting participants were split into two

equal groups (control and test) at random. Patients who participated in the

test group underwent LRS utilizing the modified approach, while participants in

the control group underwent LRS using the traditional/conventional procedure.

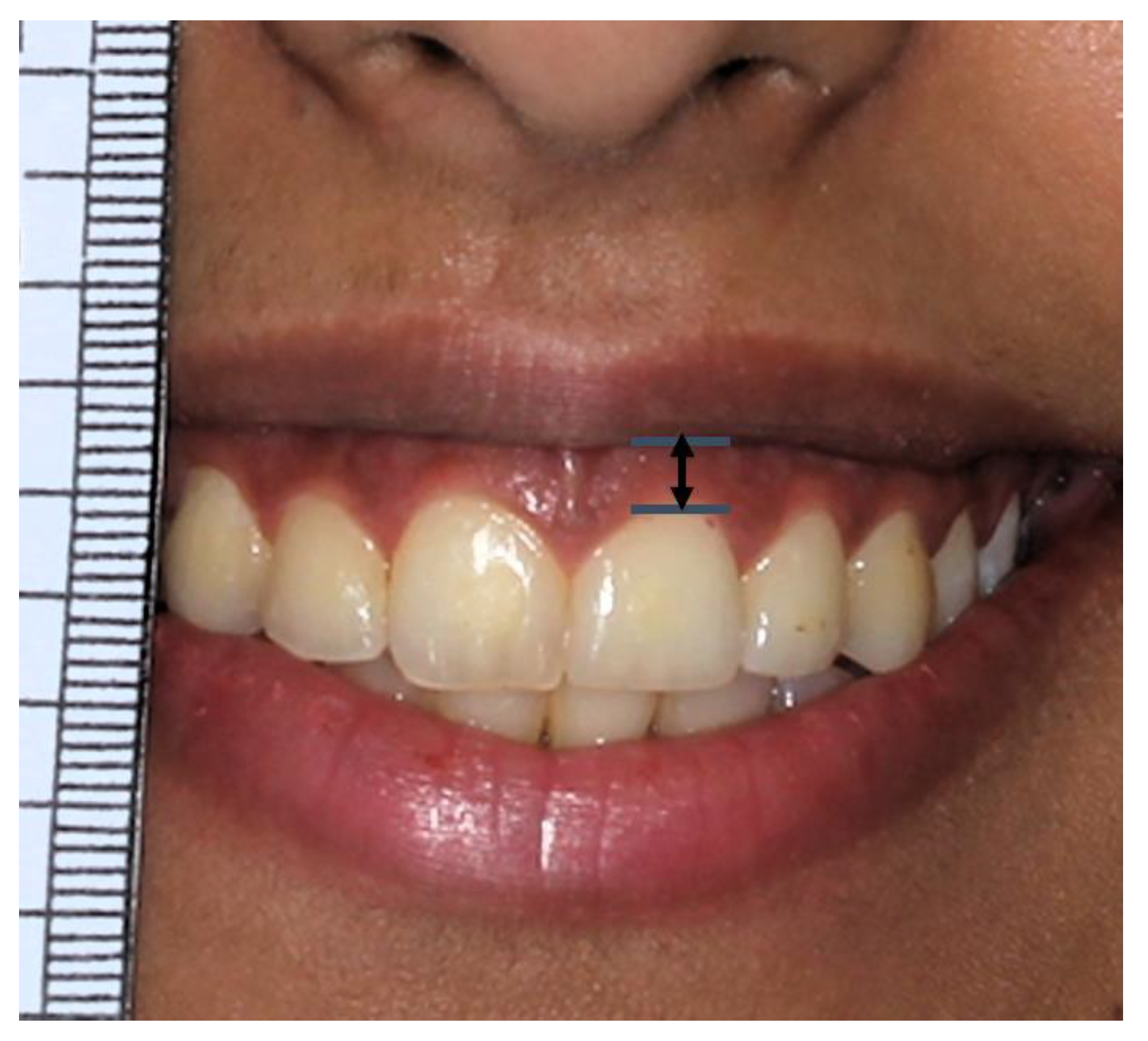

While the patient was smiling the widest, the gingival display above the right

central incisor of the maxilla was measured in millimeters (

Figure 1). The measurements were made in

millimeters (mm) at four different time intervals: baseline, one month, six

months, and one year.

2.4. Oral-Facial Esthetic Questionnaire (OEQ)

The answers of the subjects were recorded using the

OEQ (

Table 1) [22,23].

The scale, which of eight questions, was designed to measure participants'

opinions of their own face and oral aesthetics at four time points.

The questionnaire termed OEQ evaluated the orofacial esthetics. Its reliability and validity were assessed while it was being developed for prosthodontic and orthodontic patients. There are eight

questions in this instrument. Participants are questioned about how they feel

about the way their face, mouth, teeth, and artificial teeth look. The

participants gave their feedback on a scale of 0 to 10 (with 0 denoting

"very dissatisfied" and 10 denoting "very satisfied"), or

if they didn’t want to give feedback, they checked the "not

applicable" box. Seven esthetic elements were mentioned in the OEQ items

(face, facial profile, mouth, teeth in rows, tooth shape/form, tooth color,

gum). The summative score for these seven components ranged from 0 to 70 (the

maximum score was achieved when the patient was entirely satisfied). An eighth

OEQ item described how the patient felt about orofacial esthetics overall.

2.5. Follow-Up Appointments

The following follow-up appointments were scheduled: Baseline: Before the procedure, 1 month after the procedure, 6 months after the procedure, and 1 year after the procedure. At each of the many follow-up appointments after the LRS, OEQ were given to the participants. Patients answered each of the eight questions on a Likert scale with a maximum score of 10, where a higher score indicates better esthetics (0=very dissatisfied to 10=very satisfied).

2.6. Data Analyses

The summary results of the OEQ questions and participant sociodemographic data were examined for central tendency (means) and variability (standard deviation; SD). Student T-Tests were employed in the statistical program for social sciences (SPSS, version 21.0, Chicago, Illinois, USA) to make sure that both (Test and Control groups) were compared and could be evaluated for statistically significant differences. The Independent Samples T-Test was used to compare the gingival display between the Test and Control group at various dates. In 193 (96.5%) of the subjects, all eight questions on the Oral-Facial-Esthetic scale were answered. Only 7 (3.5%) of the participants didn't participate and didn't finish the survey, so they weren't included in the analysis of the survey items.

3. Results

All 200 of the participating patients' GD data were documented. However, 7 (3.5%) of the total patients were unable to take part in the study's orofacial esthetic evaluation questionnaire portion and record their responses.

Table 2 compares the means of the GD measured in millimeters (mm) for the control and test groups of the involved patients at four different time points. Non-significant differences (P>0.05) were seen between the control and test groups at the baseline, one-month, and six-month measurements. The GDs for the control (3.77+1.76mm) and test (2.48+0.86mm) groups, however, exhibited a significant difference at a one-year follow-up (P=0.000).

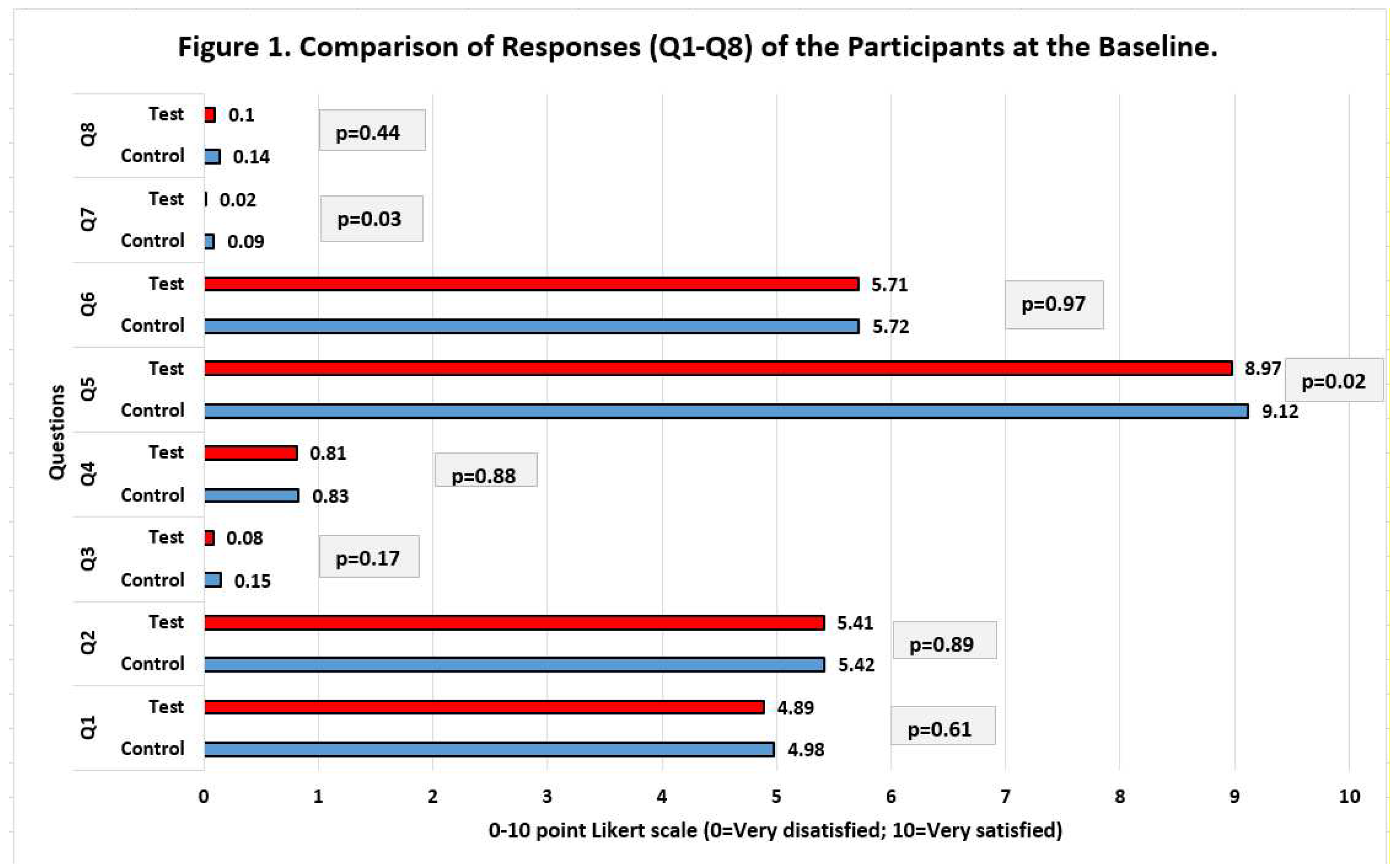

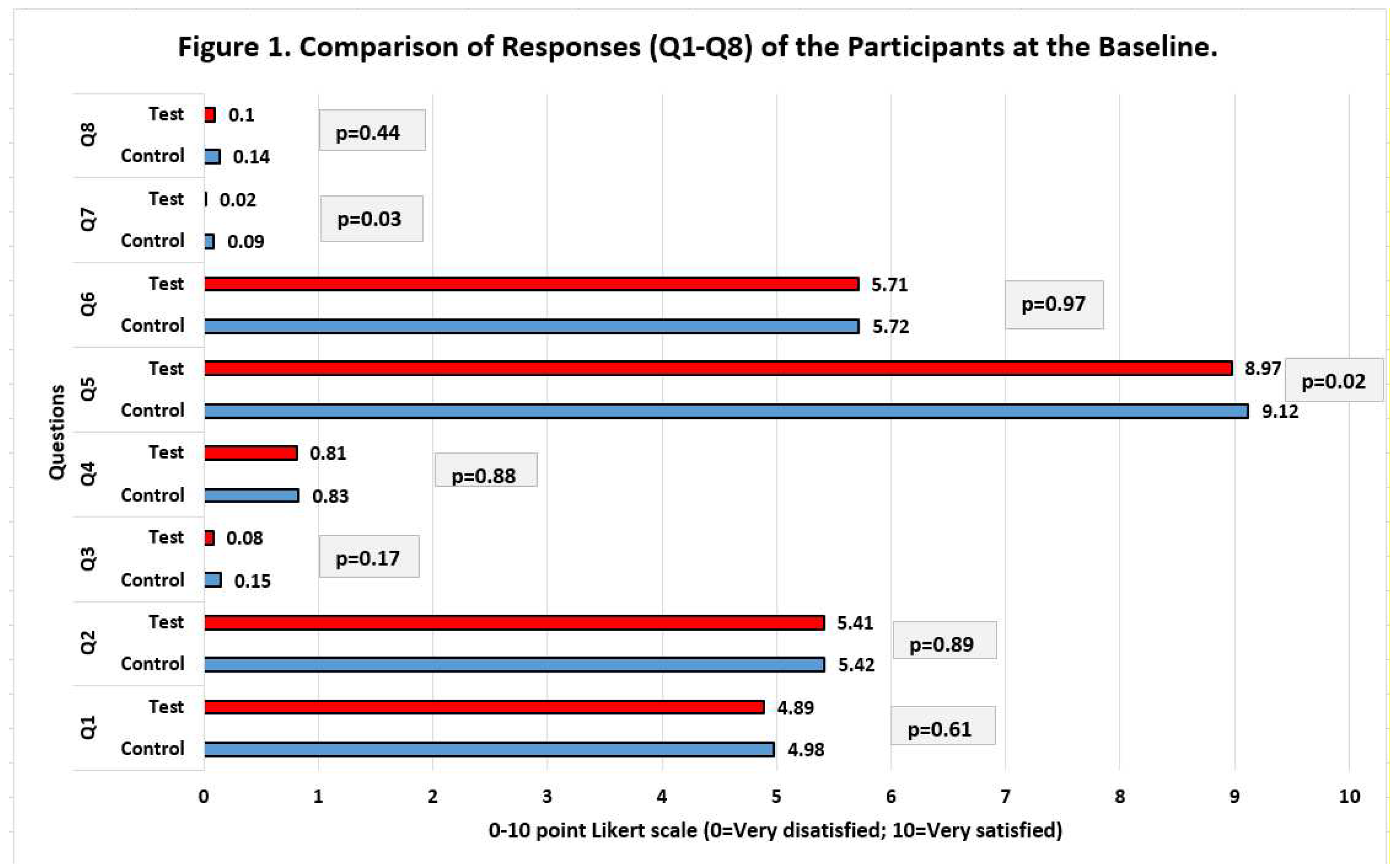

The baseline data for participant responses to the eight questions of the OEQ are shown in Figure 1 on a Likert scale. Patients in the control and test groups responded in very identical ways. It was clear from the participants' responses that nearly all of them were unhappy with their mouth's appearance (smile, lips, visible teeth) (Question 3), appearance of their teeth (Question 4), appearance of their gums (Question 7), and overall appearance of their mouth, gums, and teeth (Question 8).

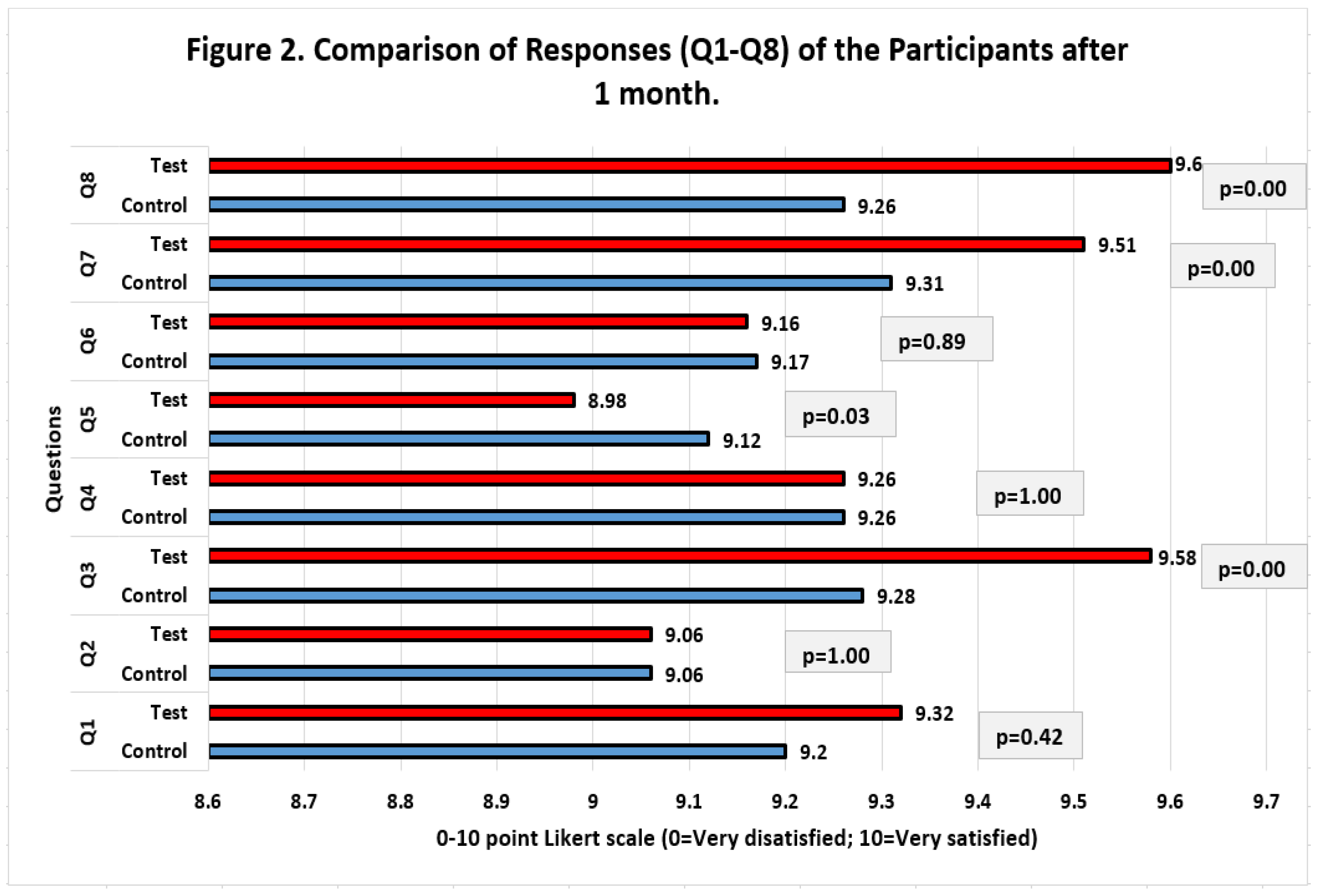

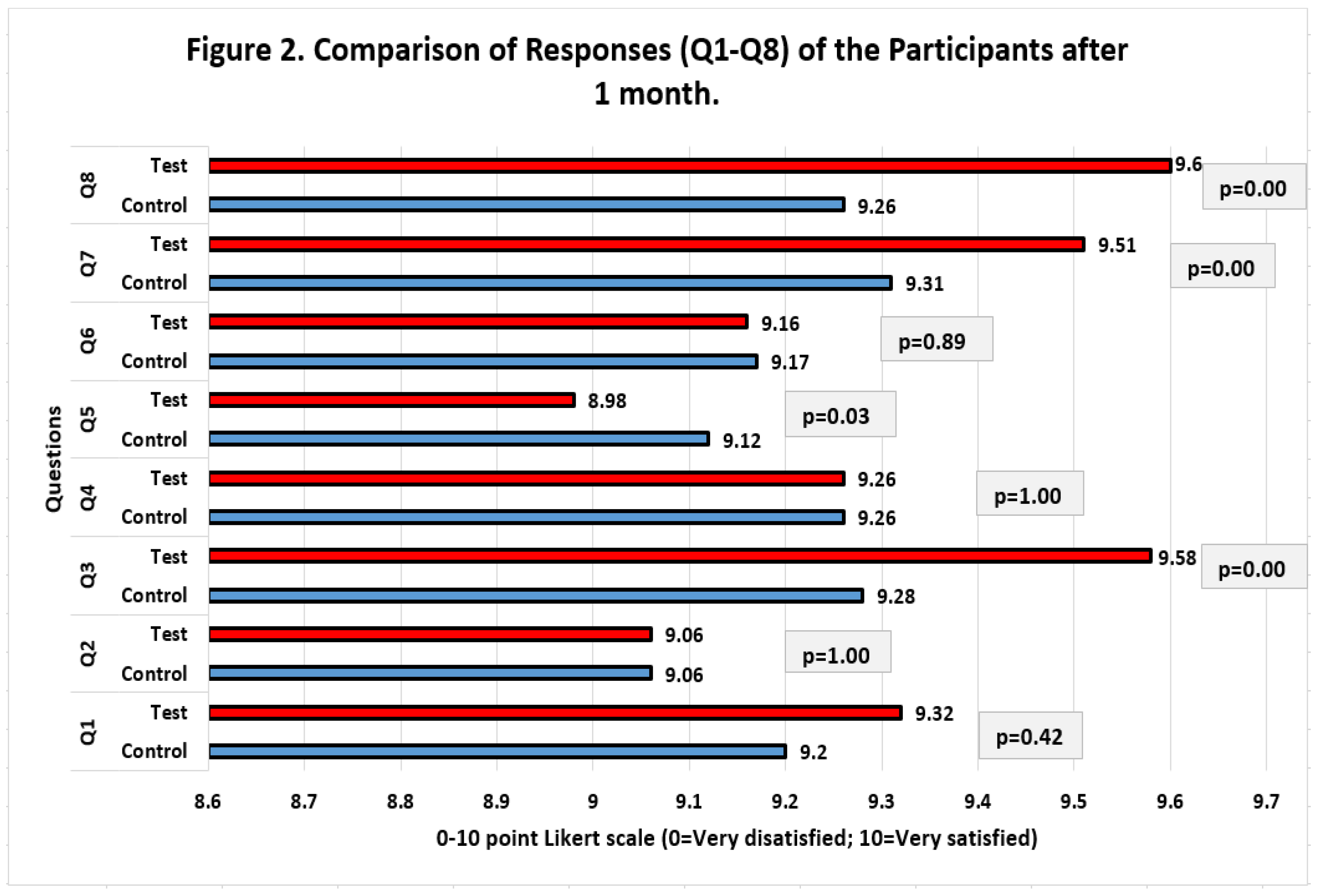

The statistics from the participant replies to the eight questions of the OEQ at the 1-month follow-up are shown in Figure 2. Regarding the participants' rating of the responses given by the patients in the control and test groups using the Likert scaling set, they were practically identical. Although comparisons for questions 3, 5, 7 and 8 revealed statistical differences (P 0.05), the largest difference in response values was just 0.34 between the control (9.26) and test (9.6) group responses. Overall, the test and control group participants' replies indicated a significant increase in the patient's level of satisfaction compared to the data gathered at the baseline.

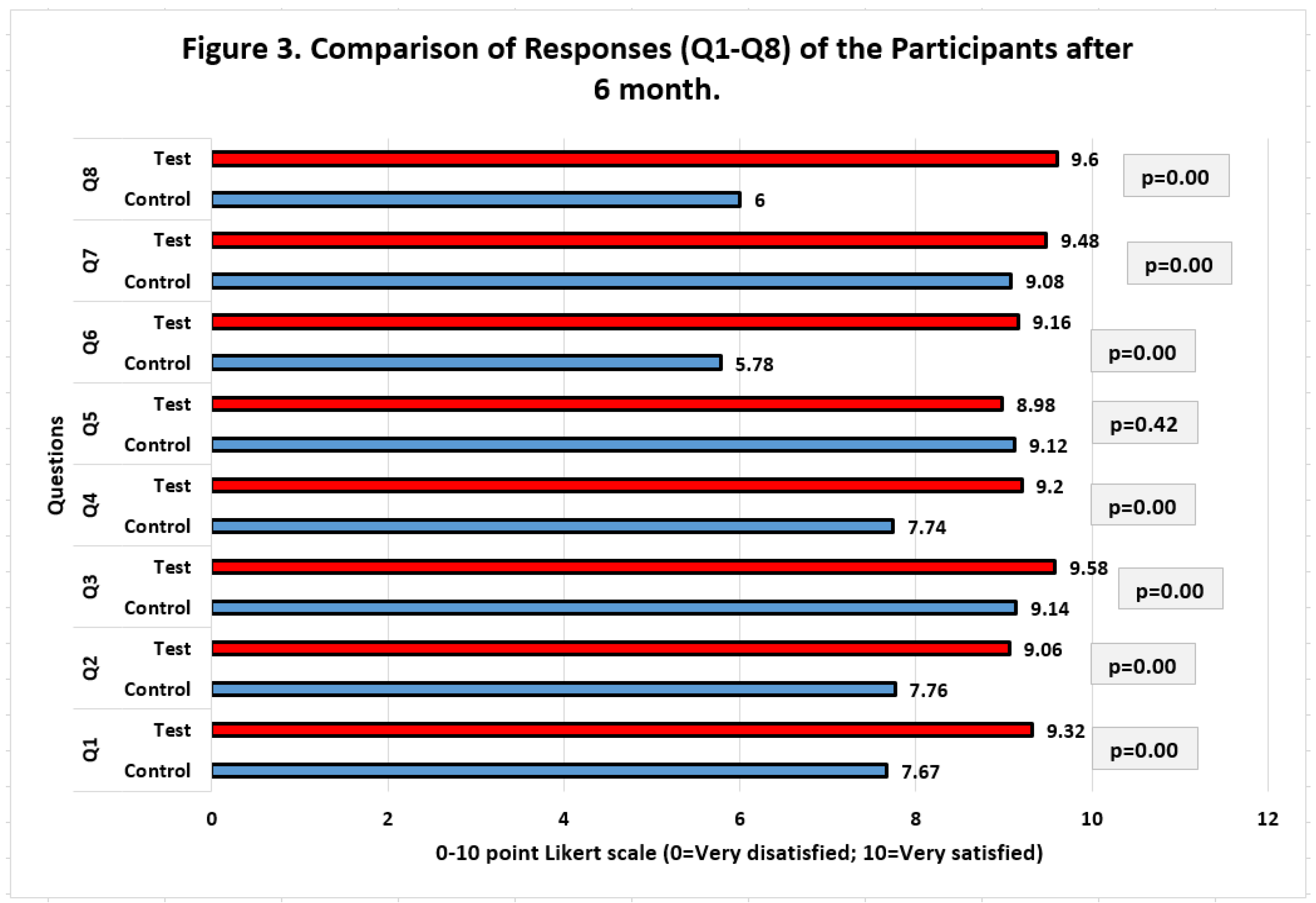

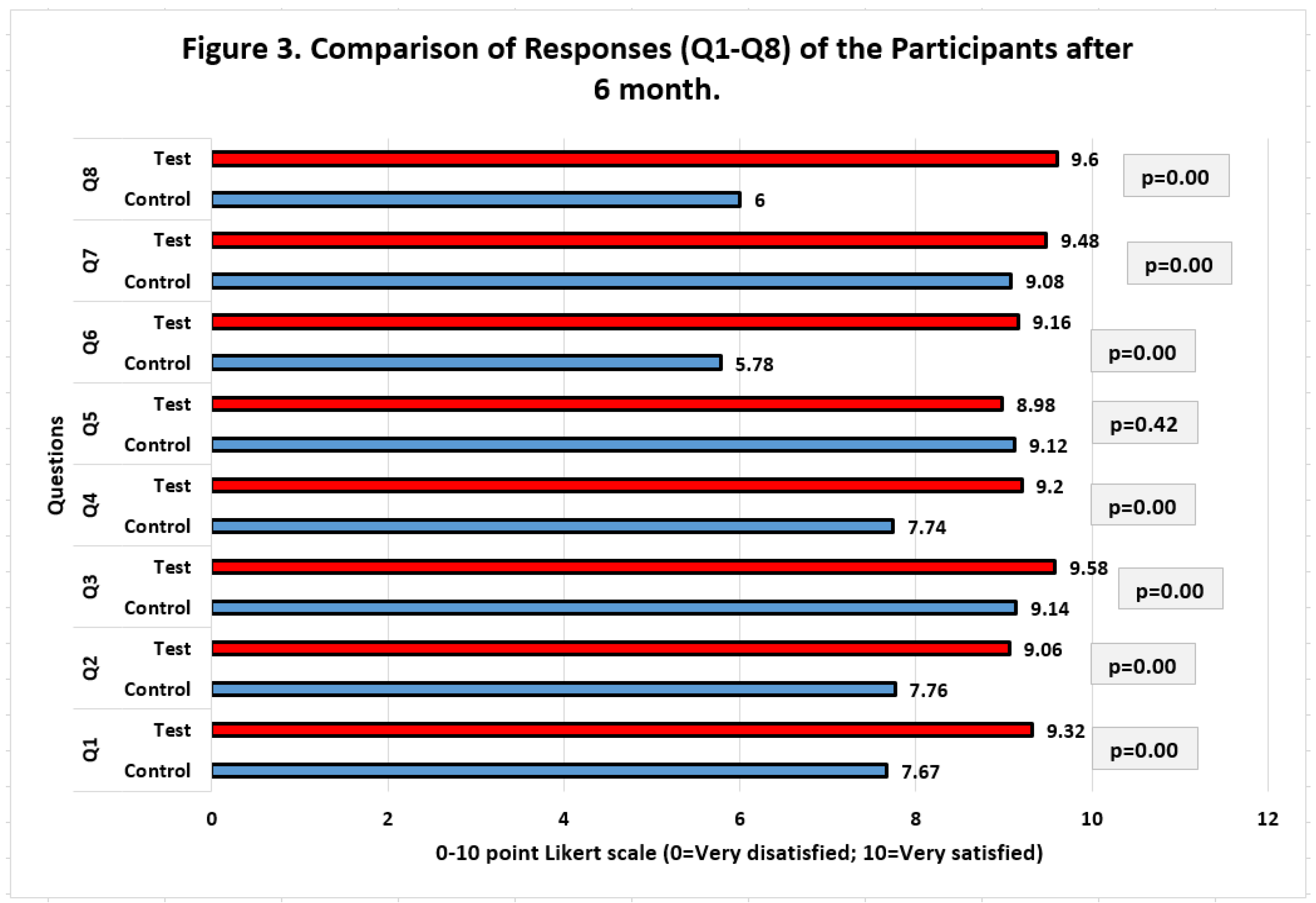

Figure 3 presents the results from the participant responses to the eight questions of the OEQ recorded using the Likert scale at the 6-month follow-up. With the exception of question #5 (P=0.42), the values of the patient replies in the control and test groups indicated significant differences (P0.05) for all of the questions at the 6-month follow-up. The test group and control group's replies varied most (3.6) and least (0.14), respectively, for questions 8 and 5, respectively. Overall, the test group maintained a higher level of patient satisfaction when compared to the total replies from the control group, according to the values of the responses provided by the test and control group members.

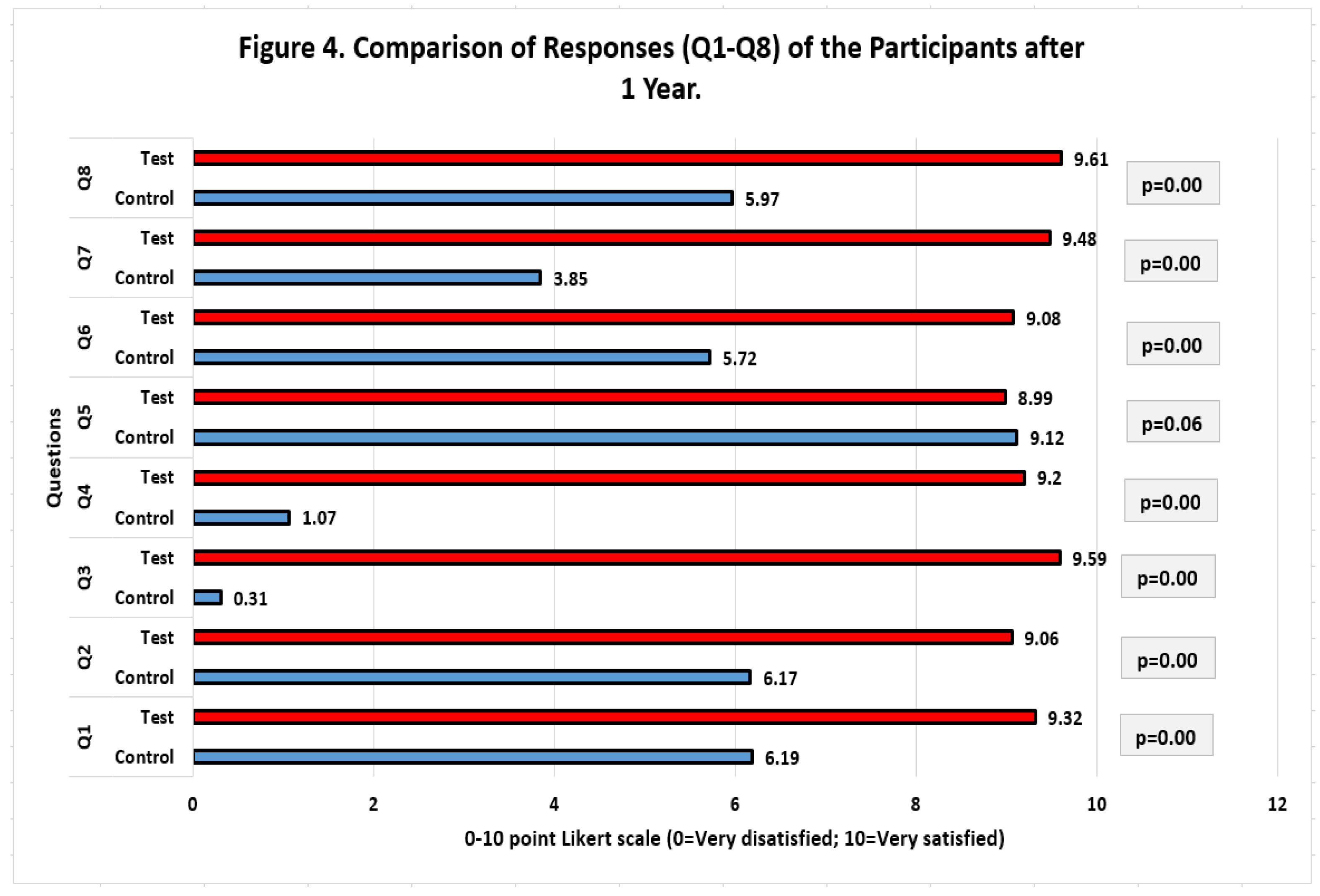

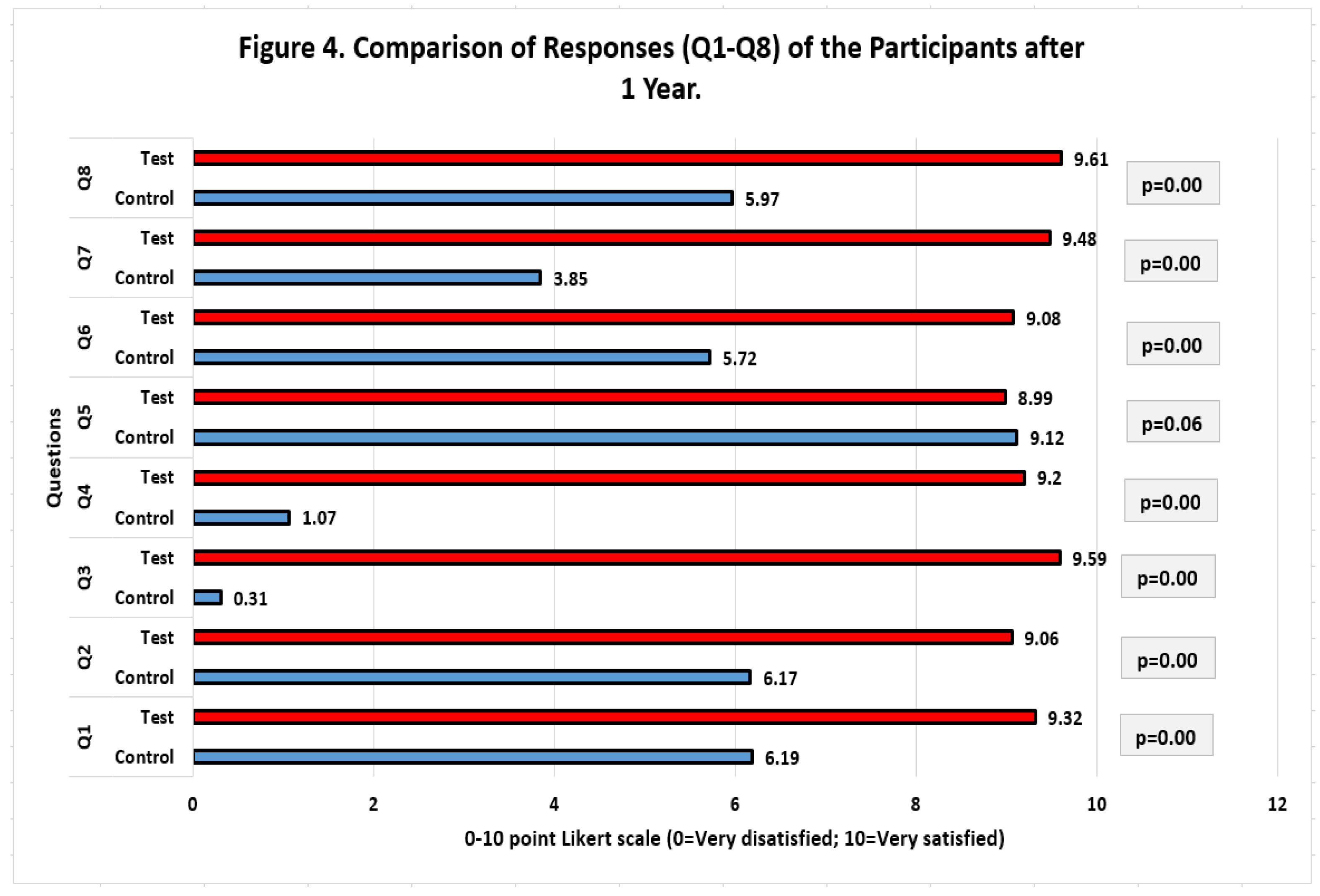

Figure 4 shows the results from the participant responses to the eight questions of the OEQ evaluation recorded using the Likert scale at the 1-year follow-up. There were significant differences between the patient response values in the control and test groups at the 1-year follow-up for all questions, with the exception of question #5 (P=0.06), which is understandable given that the surgical technique used in the study will not affect the shape of the teeth (Q5). Participants' replies revealed that patients in the test group category who underwent the LRS with the changed approach were more satisfied. The test group's participating patients' average satisfaction score was higher than 9, indicating a high level of satisfaction. Patients in the control group scored their satisfaction less favorably, with certain questions (Q3) receiving scores as low as 0.31.

Table 3 compares the overall responses (Q1-Q8) for the Test and Control groups at various times using an Independent Samples T-Test. The test group's perception of oral and facial esthetics, as judged by the study participants, was found to be significantly higher for the test group than for the control group at different time points. At the 1-year follow-up, the mean difference was 4.46, which was the greatest (P=0.000). This proved that patients in the test group who received LRS with the modified approach had greater long-term patient satisfaction levels than those in the control group who got LRS using the standard technique.

4. Discussion

The orofacial esthetics questionnaire (OEQ) can be used to measure orofacial esthetics, which is a dimension of oral health-related quality of life, a comprehensive and significant notion to characterize how people view their oral health [22-24]. The present study expands the scope of the scale's original use for prosthodontic or orthodontics patients by evaluating the orofacial esthetics of periodontal patients who underwent lip repositioning surgery (LRS) to treat an excessively gummy smile.

The success of the majority of dental procedures performed on patients includes not only restoring the stomatognathic system's lost functions but also enhancing the face's attractiveness and harmony with the rest of the body [

25]. Research and clinical observations revealed that patients' perceptions of facial esthetic characteristics frequently differed from professionals' perceptions [

26]. Nevertheless, it is difficult to quantify because it depends on a number of variables, including age, gender, educational attainment, culture, and the method of measurement [

25,

26]. The patient's satisfaction with orofacial esthetic appearance and the impact of its impairment, influencing the patient's psychosocial quality of life, are used to assess the patient's self-perception of orofacial appearance [21-26]. Orofacial esthetics evaluations can be performed at many points in time, including before and after dental work has been done [

23]. The Orofacial Esthetic questionnaire (OEQ) was utilized in this study as the study tool to assess how the participating patients felt about their orofacial look. The successful use of OEQ in previous studies with similar objectives has been reported in literature [22-28]. In order to assess the overall satisfaction of the participating patients with their esthetic appearance prior to the LRS, after 1 month, after 6 months, and after 1 year following the surgery, the patients' satisfaction regarding their orofacial condition was targeted in all the questions asked.

When time and resources are limited, the OEQ is a quick and easy to use questionnaire that can be used to assess the face and oral esthetics of dental patients [

27]. The OEQ is a practical and time-saving tool for epidemiological studies, national health surveys, and ordinary dentistry practice where a multi-item OEQ questionnaire is not viable due to a larger patient sample size [

28]. This is because of its concision and simplicity of use. In the past, sophisticated multi-item surveys were employed more frequently than single-item surveys, which were thought to be less accurate, valid, and comprehensive [

27,

28]. Currently, this pattern is changing among practitioner researchers, who now favor the use of single-item questionnaires, particularly in clinical settings because they take less time, are easier for respondents to complete, and are less expensive to collect data from [

29]. Multi-item instruments may be more discriminating and better suited for complex constructs, but they can take longer and may result in answer errors. This offers an opportunity that is both conceptually appealing and practical and may be used in extensive epidemiological studies, clinical trials, and ordinary dental care, all of which would enhance the field of evidence-based dental practice [29-31].

The results of the present study demonstrated advancements in the clinical characteristics of the excessive gingival display in the test group by demonstrating lower scores than the control group for the assessed gingival display at various time points. The gingival display at the 1-year follow-up was excellent, demonstrating that there had been no relapse in the test group, and it was much lower than that of the control group. According to the responses that the participating patients recorded, the psychological impact was likewise strong, with the test group participants expressing significantly higher levels of satisfaction than the participants in the control group. According to the findings of the current study, the results of lip repositioning surgery with a modified method were stable even after a year of follow-up, and the participants who underwent this surgery were pleased with the results. Thus the null hypothesis of no variations between the patients' perceptions of their face and oral esthetics at the various postoperative intervals with the two lip repositioning techniques was rejected. The current surgical technique (Modified Lip Repositioning Surgery) employed can therefore be considered less invasive, more conservative, and can be adopted for the treatment of excessive gingival display, which is also supported by prior literature [14-17]. This is in comparison to other treatment modalities for the excessive gingival display [

13,

32,

33].

Numerous practitioners experimented with a variety of methods to treat their patients' annoying gummy smile issues, including lip repositioning, cosmetic crown lengthening, gingival depigmentation, a combined strategy for a gummy smile makeover and micro-autologous fat transplantation, orthognathic surgery that necessitates general anesthesia, and aggressive bony osteosynthesis [32-34]. In comparison to orthognathic surgery, lip repositioning surgery offers a cautious and less aggressive surgical approach and has showed predictive results in the treatment of EGD [14-17]. The current study discovered that at one year following the modified lip repositioning operation, the LRS could result in an overall EGD reduction of 2.88 mm. These findings are somewhat in line with earlier research that showed an average decline of 2.71 to 3.4 mm [

35] at six months and 2.10 mm [

36] at a year. However, the unique aspect of this study was how it contrasted the standard lip repositioning approach with the previously unreported modified technique. And two crucial findings of the current investigation are the direct comparison of the EGD at various time points following the two surgical methods and the considerable improvement of EGD with the modified LRS.

Within the constraints of this investigation, and based on the overall evidence derived from the findings, the LRS is more effective at treating EGD while also generating greater patient satisfaction levels. Due to the gender selection, the results of this study should be evaluated with care. Female patients make up the majority of the research group, which is consistent with several studies in the field of cosmetic dentistry because women are more conscious of their oral and facial looks than men are, and they also place greater importance on aesthetics [

37]. Young people made up the majority of the patients that participated and received LRS for the current study in terms of average age. The aesthetic requirements of people at this age and the fact that the EGD condition tends to gradually improve with age because of decreasing muscle tone resulting in lower lip mobility may be related to this [

38]. To obtain more substantial and definitive results regarding the outcome, long-term stability, and the patient's response and happiness with the improved LRS approach, additional carefully planned clinical trials are nonetheless required.

5. Conclusions

Within the limitations of the current study, it can be concluded as;

The excessive gingival display improved significantly at one year follow up with the modified lip repositioning surgical technique as compared to the conventional/classic lip repositioning technique.

According to the participating patient’s responses recorded, the satisfaction level of the patients with the outcomes of the modified lip repositioning surgery was significantly higher as compared to the patients who underwent lip repositioning surgery with conventional technique.

The oral and facial esthetic scale used in the study is a promising instrument for the assessment of oral and facial aesthetics and can be used in future studies with similar objectives.

Funding

This research was funded by R.N.A.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The College of Dentistry Research Center, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia's institutional review board (IRB) and institutional committee of research ethics both accepted the project's project activities (Approval number. E-18-113207). The 2013 revision of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration was followed when conducting the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available on request from corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Miss Elma Lusay, Helen Garcia, and Marina Luma deserve special thanks for their invaluable support in setting up participant visits, carrying out blinding, and gathering data. Additionally, this acknowledges Prof. Syed Rashid Habib's invaluable assistance with data modification, analysis, and final paper review. The College of Dentistry Research Center (CDRC) and the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, are also acknowledged by the author for their contributions to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Runte C, Dirksen D. Symmetry and Aesthetics in Dentistry. Symmetry. 2021; 13(9):1741. [CrossRef]

- Bhuvaneswaran, M. Principles of smile design. J Conserv Dent. 2010 Oct;13(4):225-32. [CrossRef]

- Militi A, Sicari F, Portelli M, Merlo EM, Terranova A, Frisone F, Nucera R, Alibrandi A, Settineri S. Psychological and Social Effects of Oral Health and Dental Aesthetic in Adolescence and Early Adulthood: An Observational Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Aug 27;18(17):9022. [CrossRef]

- Ellakany, P. , Fouda, S.M., Alghamdi, M. et al. Factors affecting dental self-confidence and satisfaction with dental appearance among adolescents in Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. BMC Oral Health 21, 149 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Rajeh, MT. Gender Differences in Oral Health Knowledge and Practices Among Adults in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2022 Aug 4;14:235-244. [CrossRef]

- Alhammadi, Maged & Halboub, Esam & Al-Mashraqi, Abeer & Al-Homoud, Mona & Wafi, Sharifah & Zakari, Areeg & Mashali, Wedad. (2018). Perception of facial, dental, and smile esthetics by dental students: Alhammadi et al.. Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry. 30. [CrossRef]

- Mafra AL, Silva CSA, Varella MAC, Valentova JV. The contrasting effects of body image and self-esteem in the makeup usage. PLoS One. 2022 Mar 25;17(3):e0265197. [CrossRef]

- Svedström-Oristo, Anna-Liisa & Pietilä, Terttu & Pietilä, Ilpo & Vahlberg, Tero & Alanen, Pentti & Varrela, Juha. (2009). Acceptability of Dental Appearance in a Group of Finnish 16-to 25-Year-Olds. The Angle orthodontist. 79. 479-83. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira LV, Colussi PRG, Piardi CC, Rösing CK, Muniz FWMG. Self-Perception of Teeth Alignment and Colour in Adolescents: A Cross-sectional Study. Int Dent J. 2022 Jun;72(3):288-295. [CrossRef]

- Pham TAV, Nguyen PA. Morphological features of smile attractiveness and related factors influence perception and gingival aesthetic parameters. Int Dent J. 2022 Feb;72(1):67-75. [CrossRef]

- Althagafi, N. Esthetic Smile Perception Among Dental Students at Different Educational Levels. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2021 ;13:163-172. 7 May. [CrossRef]

- Negruțiu BM, Moldovan AF, Staniș CE, Pusta CTJ, Moca AE, Vaida LL, Romanec C, Luchian I, Zetu IN, Todor BI. The Influence of Gingival Exposure on Smile Attractiveness as Perceived by Dentists and Laypersons. Medicina. 2022; 58(9):1265. [CrossRef]

- Brizuela M, Ines D. Excessive Gingival Display. [Updated 2023 Mar 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470437/.

- Gaddale R, Desai SR, Mudda JA, Karthikeyan I. Lip repositioning. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014 Mar;18(2):254-8. [CrossRef]

- Rao AG, Koganti VP, Prabhakar AK, Soni S. Modified lip repositioning: A surgical approach to treat the gummy smile. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015 May-Jun;19(3):356-9. [CrossRef]

- Sheth T, Shah S, Shah M, Shah E. Lip reposition surgery: A new call in periodontics. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013 Jul;4(3):378-81. [CrossRef]

- AlJasser RN. A Modified Approach in Lip Repositioning Surgery for Excessive Gingival Display to Minimize Post-Surgical Relapse: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023 Feb 14;13(4):716. [CrossRef]

- Vardimon AD, Shpack N, Wasserstein A, Skyllouriotou M, Strauss M, Geron S, Sadan N, Levartovsky S, Sarig R. Upper Lip Horizontal Line: Characteristics of a Dynamic Facial Line. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Sep 13;17(18):6672. [CrossRef]

- Dayakar MM, Gupta S, Shivananda H. Lip repositioning: An alternative cosmetic treatment for gummy smile. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014 Jul;18(4):520-3. [CrossRef]

- Flórez PRB, Guzmán JA, Orozco Páez J. Laser-Assisted Lip Repositioning Surgery: A Modification to The Conventional Technique. J Lasers Med Sci. 2022 ;13:e22. 16 May. [CrossRef]

- Alhajj MN, Ariffin Z, Celebić A, Alkheraif AA, Amran AG, Ismail IA. Perception of orofacial appearance among laypersons with diverse social and demographic status. PLoS One. 2020 Sep 17;15(9):e0239232. [CrossRef]

- Prica N, Čelebić A, Kovačić I, Petričević N. Assessment of Orofacial Esthetics among Different Specialists in Dental Medicine: A pilot study. Acta Stomatol Croat. 2022 Jun;56(2):169-175. [CrossRef]

- Mursid, Saraventi & Maharani, Diah & Kusdhany, Lindawati. (2020). Measuring Patient’s Orofacial Estheticsin in Prosthodontics: A Scoping Review of a Current Instrument. The Open Dentistry Journal. 14. 161-170. [CrossRef]

- John MT, Larsson P, Nilner K, Bandyopadhyay D, List T. Validation of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale in the general population. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012 Nov 19;10:135. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.Y.N. , Liu, P.P. & Wong, M.C.M. Patients’ satisfaction with dental care: a qualitative study to develop a satisfaction instrument. BMC Oral Health 18, 15 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Fabi S, Alexiades M, Chatrath V, Colucci L, Sherber N, Heydenrych I, Jagdeo J, Dayan S, Swift A, Chantrey J, Stevens WG, Sangha S. Facial Aesthetic Priorities and Concerns: A Physician and Patient Perception Global Survey. Aesthet Surg J. 2022 Mar 15;42(4):NP218-NP229. [CrossRef]

- Andela, Stephanie & Lamprecht, Ragna & John, Mike & Pattanaik, Swaha & Reissmann, Daniel. (2021). Development of a one-item version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale. Clinical Oral Investigations. 26. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Simancas-Pallares M, John MT, Prodduturu S, Rush WA, Enstad CJ, Lenton P. Development, validity and reliability of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale - Spanish version. J Prosthodont Res. 2018 Oct;62(4):456-461. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R.A. , Pineault, L. & Hong, YH. Normalizing the Use of Single-Item Measures: Validation of the Single-Item Compendium for Organizational Psychology. J Bus Psychol 37, 639–673 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Verster JC, Sandalova E, Garssen J, Bruce G. The Use of Single-Item Ratings Versus Traditional Multiple-Item Questionnaires to Assess Mood and Health. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2021; 11(1):183-198. [CrossRef]

- Ponto, J. Understanding and Evaluating Survey Research. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2015, 6, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silberberg, N.; Goldstein, M.; Smidt, A. Excessive gingival display--etiology, diagnosis, and treatment modalities. Quintessence Int. 2009, 40, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tatakis DN, Silva CO. Contemporary treatment techniques for excessive gingival display caused by altered passive eruption or lip hypermobility. J Dent. 2023 Sep 18;138:104711. [CrossRef]

- Mossaad, Aida M.; Abdelrahman, Mostapha A.; Kotb, Amr M.1; Alolayan, Albraa B.; Elsayed, Shadia Abdel-Hameed2,. Gummy Smile Management Using Diode Laser Gingivectomy Versus Botulinum Toxin Injection - A Prospective Study. Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery 11(1):p 70-74, Jan–Jun 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik OK, El-Nahass HE, Shipman P, Looney SW, Cutler CW, Brunner M. Lip repositioning for the treatment of excess gingival display: a systematic review. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2018;30:101–12. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah WA, Khalil HS, Alhindi MM, Marzook H. Modifying gummy smile: a minimally invasive approach. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2014;15:821–6. [CrossRef]

- Rajeh, MT. Gender Differences in Oral Health Knowledge and Practices Among Adults in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2022 Aug 4;14:235-244. [CrossRef]

- Swift A, Liew S, Weinkle S, Garcia JK, Silberberg MB. The Facial Aging Process From the "Inside Out". Aesthet Surg J. 2021 Sep 14;41(10):1107-1119. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).