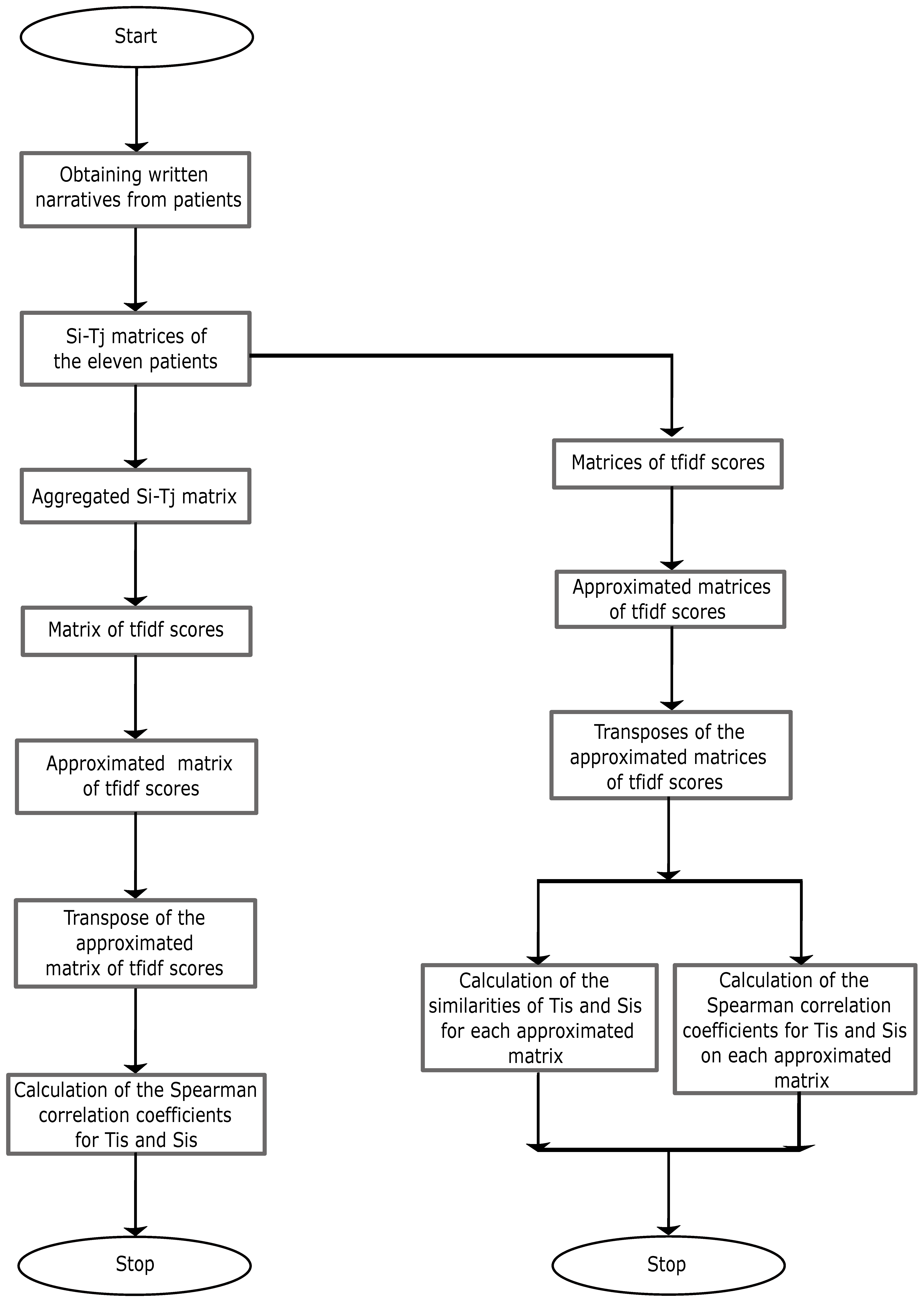

1. Introduction

Clinical depression is undoubtedly experienced as a life experience. Life as we perceive it is a chronology of life events/ moments that are subject to interpretations. Interpretations generate mood states. The fact that at least the initial moment of a person’s life cannot be influenced, postponed, canceled or retold suggests that life as a whole must be accepted. In exogenous depression, the functionality of the individual is affected by non-acceptance of life events/experiences with a traumatizing effect.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is defined as a mental disorder [

1] or as a mood disorder [

2]. To be diagnosed with MDD, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) an individual must have five of the following symptoms: persistently low or depressed mood, anhedonia, feelings of guilt or worthlessness, lack of energy, poor concentration, appetite changes, psychomotor retardation or agitation, sleep disturbances, suicidal thoughts. One of the five symptoms must be depressed mood or anhedonia [

3].

The prevalence of depression in different age groups has reached alarming levels. A recent study shows that 34% of adolescents aged 10-19 years are at risk of developing clinical depression [

4]. Another meta-analysis involving 72.878 older adults demonstrated that 28.4% of them screened positive for depression [

5]. The association of MDD with morbidity and mortality [

6] makes these values even more worrying.

The clearest and most visible effects of MDD, interpreted as associations, are dysfunctions and abnormalities at the level of the brain. Recent studies have shown that these abnormalities are due to the impairment of complex neuroregulatory systems and neuronal circuits [

3,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Other studies highlight the connection between chemical imbalance in the brain and mood disorders [

12,

13].

How does MDD manifest at mental level? An important characteristic of MDD is reduced emotional reactivity to sad contexts [

14]. Self-compassion is often used as an adaptive emotion regulation strategy, especially by patients with high levels of depressed mood [

15]. High levels of suppression of positive or negative emotions are associated with MDD symptoms [

16]. The posibility of emotional regulation in MDD medicated patients is preserved, depending on the severity of the symptoms [

17].

Other psychiatric comorbidities of MDD are: dystimia, anxiety disorders, agoraphobia, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, stress disorder, alcohol dependence, psychotic disorder, antisocial personality, suicidal risk [

18,

19,

20,

21].

The factors that favorise the onset of MDD are those that engage significant consumption of psychological resources, distancing the individual from his/her own universe of ideals, psychological experiences, and skills (UIPS), where he/she functions best. The specialized literature suggests the presence of four categories of contributing factors [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]:

The key role in interpreting the interaction environment and internal stimuli, in managing an altered UIPS as well as in the consumption of psychological resources is played by a structure that we call the interpreter of the person.

Exogenous depression, is typically amplified by experiencing and validating feelings of lack of ideals or rejection. While the human body and mind shape our offer of life and experiences, the interaction environment either integrates or rejects this offer. On the other hand, a period of life devoid of specific experiences, especially during childhood, can later be reclaimed and generate behaviours and attitudes rejected by the interaction environment. Additionally, individuals who assume non-specific roles can exhibit behaviours also rejected by others.

The lives of the patients diagnosed with major depression (MD) are primarily affected by experiencing predominant states of sadness and anxiety. We consider that the persistence of anxiety can be explained by the inability of patients to maintain UIPS intact. What can we say about the state of sadness? The functionality of the human body and mind is energetically conditioned. A functional mind processes and compares internal and/or external stimuli using a dispositional background ensured by the feeling of usefulness and by a network of ideals. Why is a functional network of ideals important? Firstly, such a network ensures a coherent behavioural perspective oriented towards achieving the principal ideal. Essentially, a functional network of ideals assures a genuine anchoring of the person’s present in the future. Secondly, the network of ideals sustains the feeling of usefulness and functions as a genuine energy battery. At the same time, the presence of the feeling of usefulness conditions the existence of the network of ideals. The entire dispositional background is an essential energy resource that ensures the normal functioning of the mind.

The network of ideals remains functional as long as the principal ideal remains active. The deactivation of the central ideal as a result of a traumatic event leads to the collapse of the entire network of ideals, which implies:

In the absence of the capacity of the other ideals to transform into a central ideal, the only solution for the normal functioning of the mind remains the maintenance of the activation of the old network of ideals. This way, the present amputated from the future perspective is continuously compared to an unaltered past that perpetuates the experiencing of sadness.

A life affected by depression must have a purpose. The purpose can either focus on the individual and/or on the interaction environment. In our opinion, depression is a life test in which the ability to accept reality and to change one’s attitude is tested.

Major depression experienced by middle-aged adults is often a treatment-resistant depression. Treatment resistance is determined not only by the deficiencies recorded at the level of the biological construct but also by the life history marked by losses, stress, and traumas, which deplete the psychological resources of the patient. Generally, the mature adult age is the age when one begins to experience health deterioration [

27,

28], painful separations, social isolation [

22,

29,

30], the reclaiming of a wasted past, the specific effects of inadequate manifestations of childhood traumas [

31,

32,

33,

34], and so on.

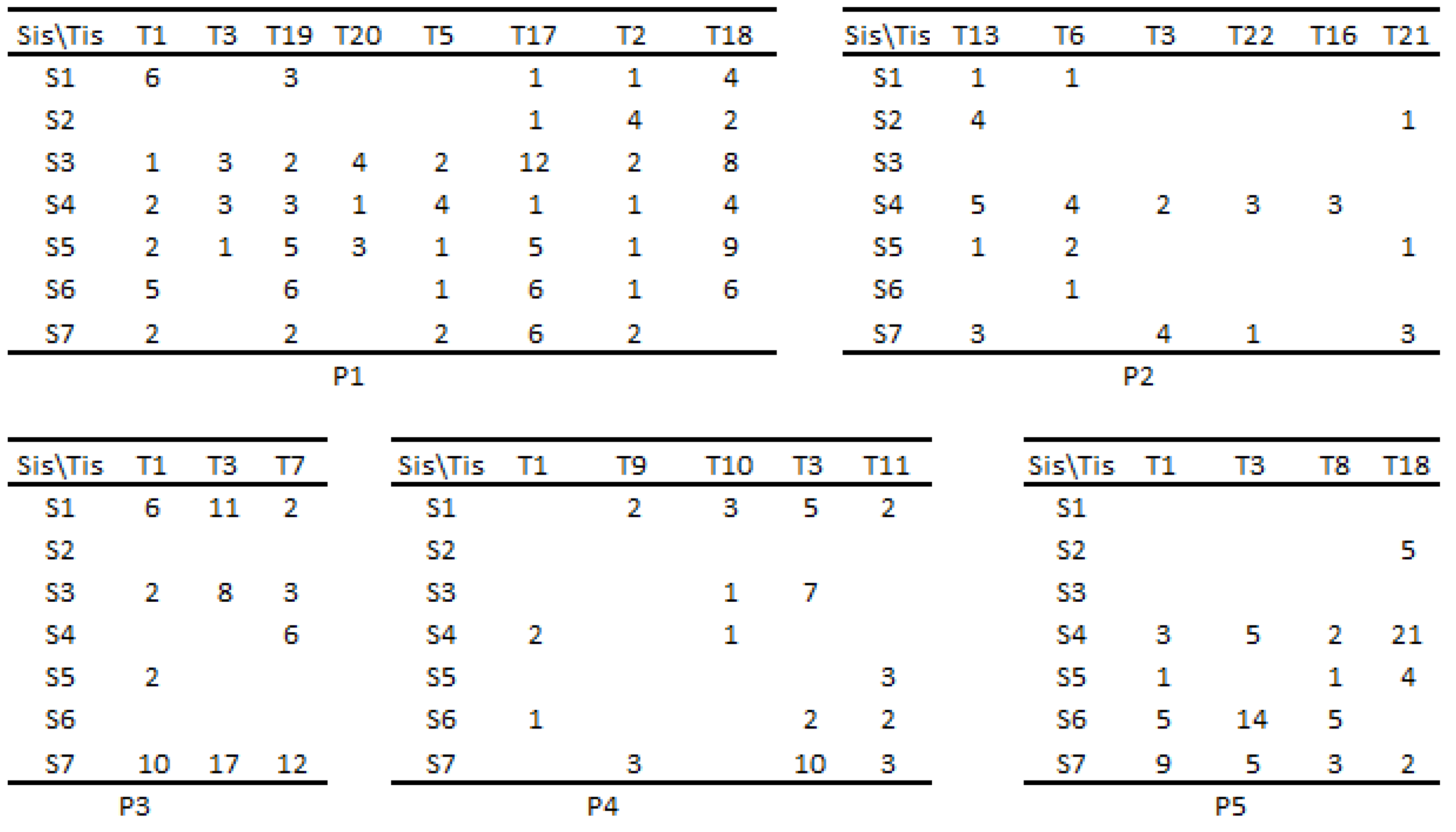

The behaviour of a middle - aged adult diagnosed with major recurrent depression is determined by dysfunctional beliefs that cause the activation of certain life themes and the manifestation of specific symptoms. The profound fixation of these beliefs causes the stabilization of both life themes and symptoms experienced in illness. Moreover, one of the reasons we focused our attention on middle-aged adults is that, in these cases, the symptoms and life themes are clear and characterized by their stability and persistence over time. Understanding the relationships between symptoms and life themes can aid the psychotherapeutic process in relativizing these beliefs.

What do we aim for? As mentioned above, symptoms and life themes are relatively stable in major recurrent depression diagnosed in middle-aged adults. They have a specific pattern of manifestation for each patient (Pi). In our opinion, these patterns should highlight:

the relationships between symptoms and life themes, starting with identifying symptoms and life themes and continuing with the ranking of the importance of symptoms on each life theme. At the level of the group of patients, this analysis can be achieved by aggregating the symptoms and life themes identified in each patient. Thus, at this level, we could have a clear picture of the representation of each life theme by the most relevant symptom. Another analysis, relevant at the level of the group of patients, is the ranking of the similarities of life themes in relation to different symptoms or groups of symptoms. Here, the relevance of the information provided by this ranking is truly important. The association, not in a statistical sense, of the dysfunctional symptom with the most similar life theme indicates the most dysfunctional symptom - life theme pair. The best combination should be sought between a symptom and the most dissimilar life theme. We consider this information useful for group psychotherapies.

-

associations, statistically treated, both between symptoms and between life themes. The analysis of these associations is relevant when it is conducted at patient level. These associations must be analyzed in close connection with the similarities/ dissimilarities of the symptoms/life themes. For example, strong and significant positive associations between dissimilar symptoms can indicate the presence of syndromes.

Using the concept of transitivity from mathematics (if A & B and B & C, then A & C), we can identify dysfunctional cycles of symptoms/life themes. These cycles signal simultaneous and multiple associations between symptoms or between life themes.

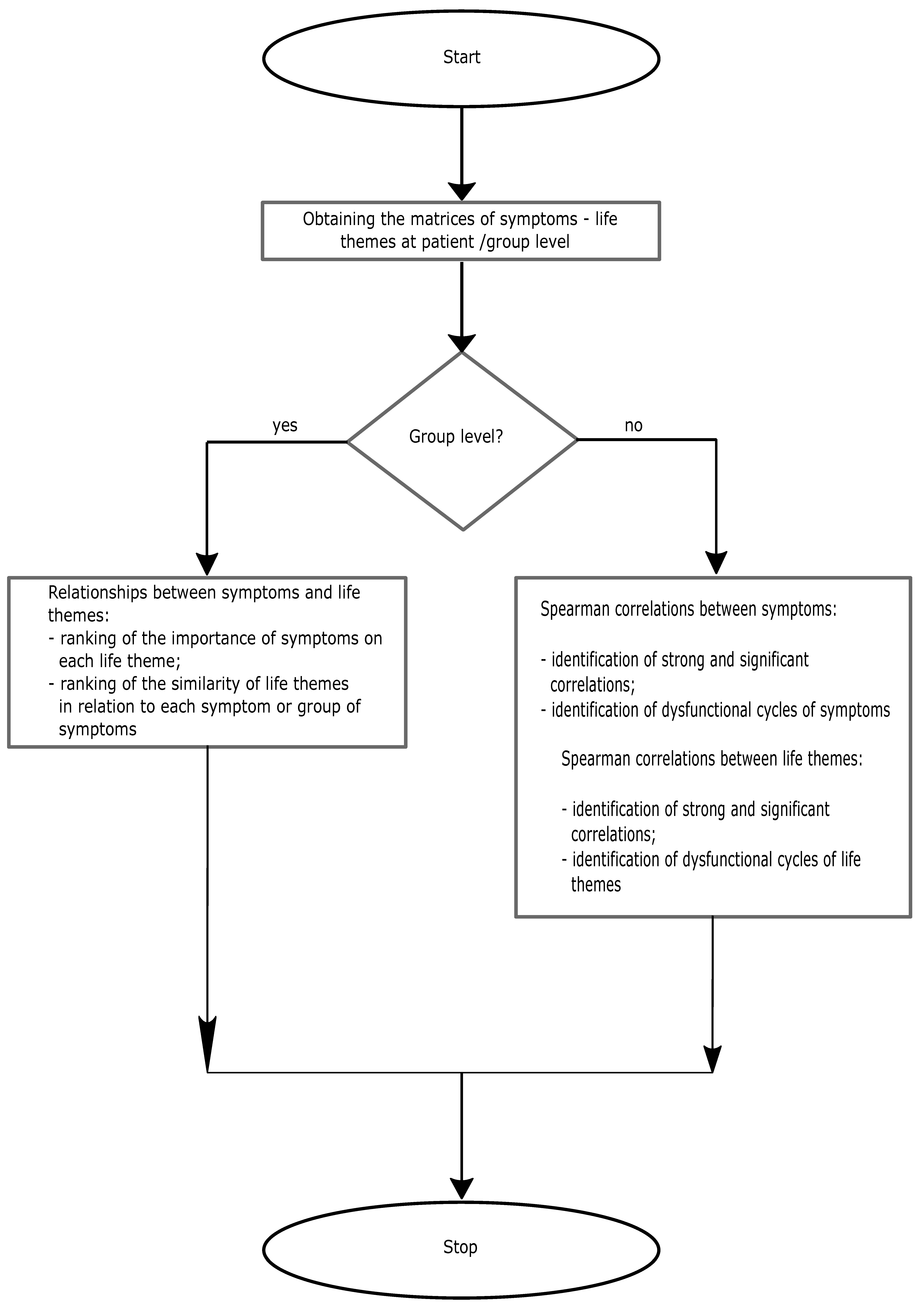

In conclusion, our research is an exploratory one, aimed at evaluating the aspects presented in

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of the research

Figure 1.

Block diagram of the research

4. Discussion

The life of an individual is unique, just as the lives of patients affected by clinical depression are. The uniqueness of life in exogenous depression is subjectively determined by perceived vulnerabilities, the experiencing and anticipation of the feelings of loss and rejection, and the interpretations given to an unfavorable backdrop of reality. From an objective standpoint, the experiencing of clinical depression is determined by changes occurring at neuronal level and transformations that generate symptoms (cellular activity− proto-emotions− emotions−symptoms).

Every moment in life is filled with psychological experiences, which suggests the presence of associations between symptoms and life themes [

43,

44]. The greater the degree of psychological impairment, the greater the stability and persistence of these associations.

Dysfunctional life themes significantly impact the life of depressed patients. These themes are the subject of a rich specialized literature [

37,

38,

39]. On a subjective level, patients with clinical depression experience widespread feelings of unhappiness. This generalization may be due to the intrusion of life themes related to unhappiness into the space of happiness [

40,

41,

42].

The analysis of Tis and life themes on the group of investigated patients presents interesting aspects. Thus, unusual presence of Tis in happiness, unhappiness, or daily theme suggests:

− inadequate presence of T3 and T6 in happiness theme that suggests the expansion of unhappiness into the space of happiness;

− inadequate presence of T11 and T17 in unhappiness theme that suggests the expansion of nostalgia into the space of happiness and alteration of the meaning of life themes through the severe expansion of existential anxiety;

− inadequate presence of T12 and T21 in daily theme that suggests the alteration of the meaning of daily themes through the severe expansion of existential anxiety;

− presence of T4 in daily theme that suggests the expansion of the obsession of loss into the daily space of reflection;

− presence of T5 in happiness theme that suggests dissapointment;

− presence of T7 in unhappiness theme that signals the obsession with failure;

− presence of T16 in daily theme that signals the need for self awareness;

− presence of T25 in daily theme that suggests the need to escape from everyday life;

− presence of T26 in unhappiness and daily themes that signals the humiliation obsession.

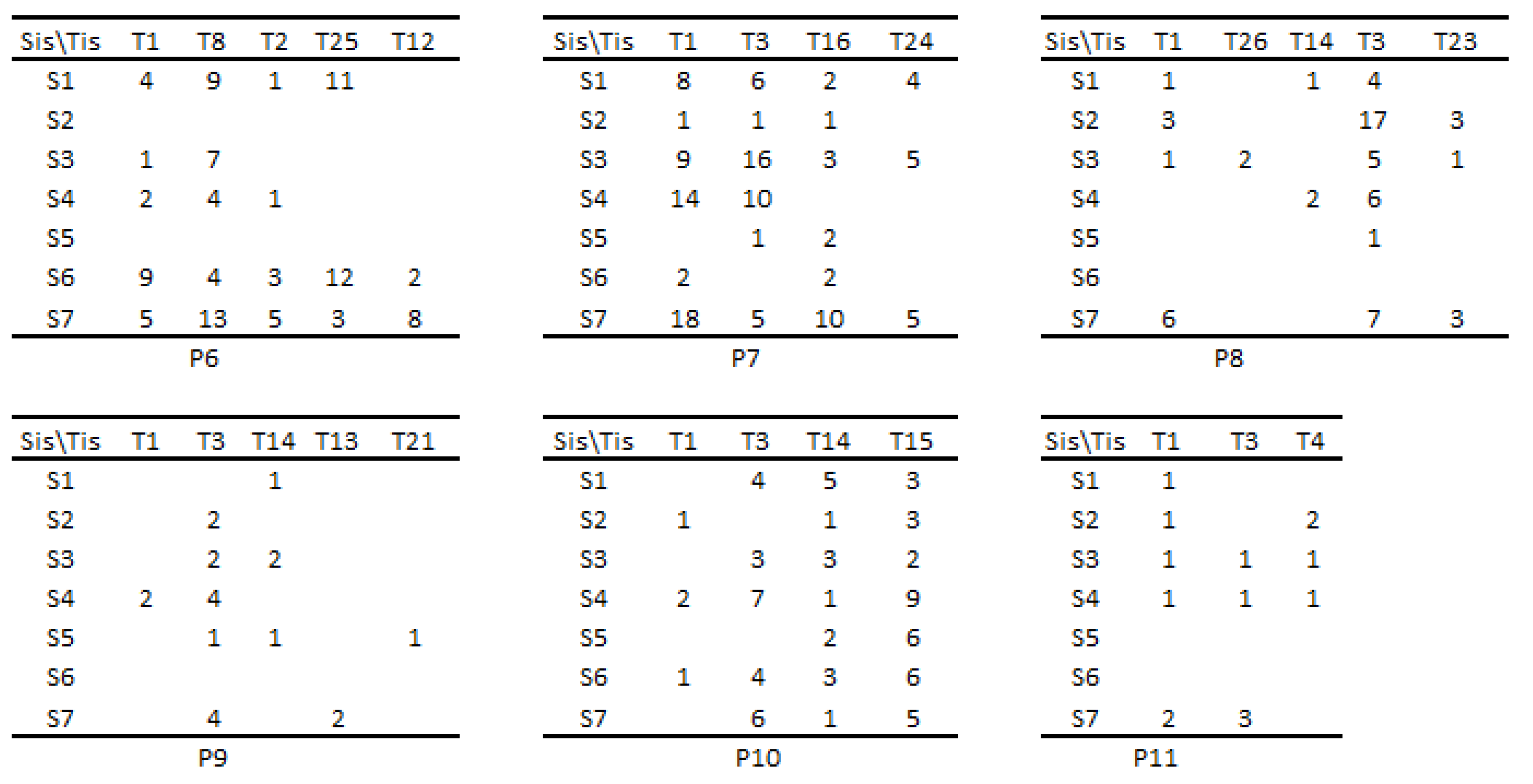

At the level of the group of patients, the most invoked symptom is sadness, followed by anxiety, regret, fury, low self-esteem, apathy, and fatigue. The specialized literature confirms this hierarchy for sadness and anxiety [

45,

46,

47]. On the other hand, the twenty six Tis can be most easily discriminated in relation to S6, S2, and S5. S6 is the most important symptom in 13 out of the 26 Tis (T1, T7, T8, T9, T10, T11, T12, T14, T16, T17, T19, T24, T25), S2 is the most important symptom in 8 out of the 26 Tis (T2, T3, T4, T13, T15, T18, T21, T23), and S5 is the most important symptom in 5 out of the 26 Tis (T5, T6, T20, T22, T26). For this reason, the base of representation for the twenty six Tis is given by S6, S2, and S5. The semantic space is defined by this representation base.

Let us analyze the importance of the most frequently mentioned symptoms, S7 and S1. The lowest tfidf scores are recorded for S7 in T1, T3, T7, T14, T15, T16, T17, and T18. These scores are a direct consequence of the presence of symptom S7 in 21 out of the 26 Tis and the low frequencies recorded in Tis (except for T1, T2, T3, T7, T8, T12, and T16, where S7 records high frequencies). Although we would expect S1 to precede S7 in terms of the lowest tfidf scores, this is not the case. This effect is due to the distribution of scores recorded by S1 across Tis. The lowest score for S1 is recorded in T13. The high frequencies recorded by S1 in T3, T1, T8, and T25 result in high tfidf scores.

Although S2 is invoked in only 12 Tis, the low frequencies recorded throughout the Tis make this symptom the least important for 8 Tis.

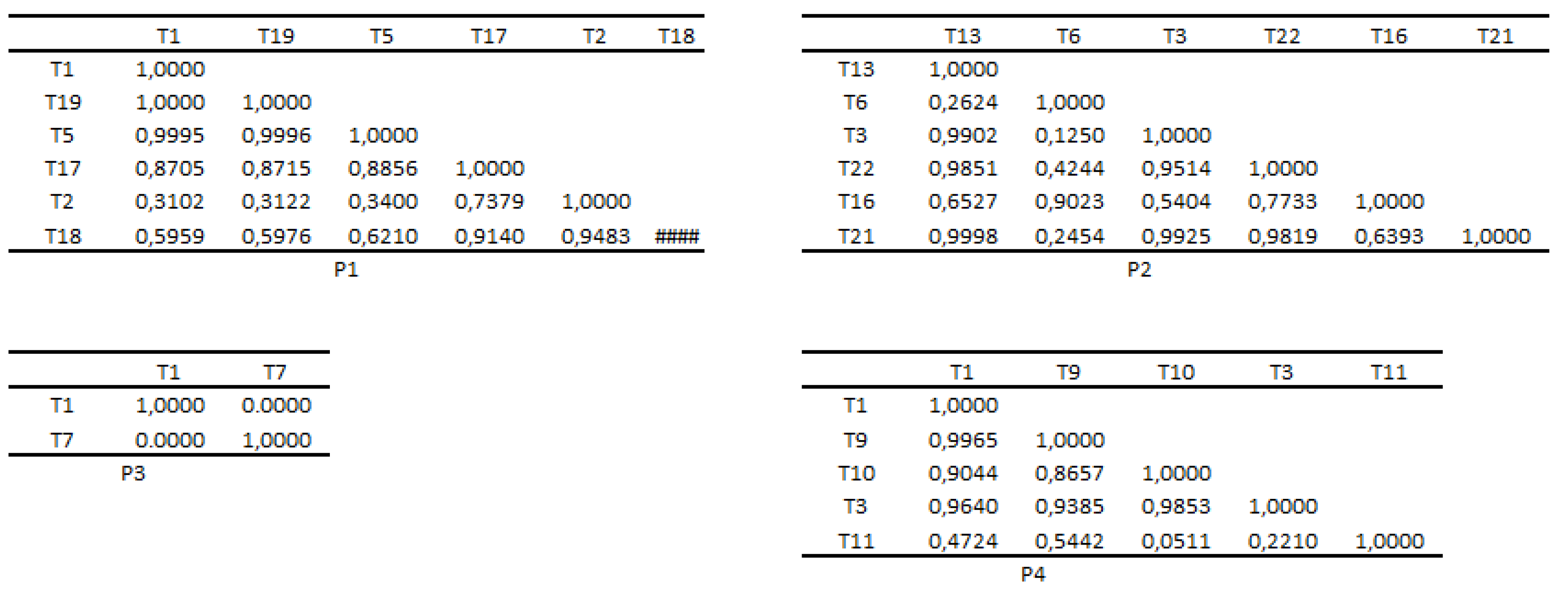

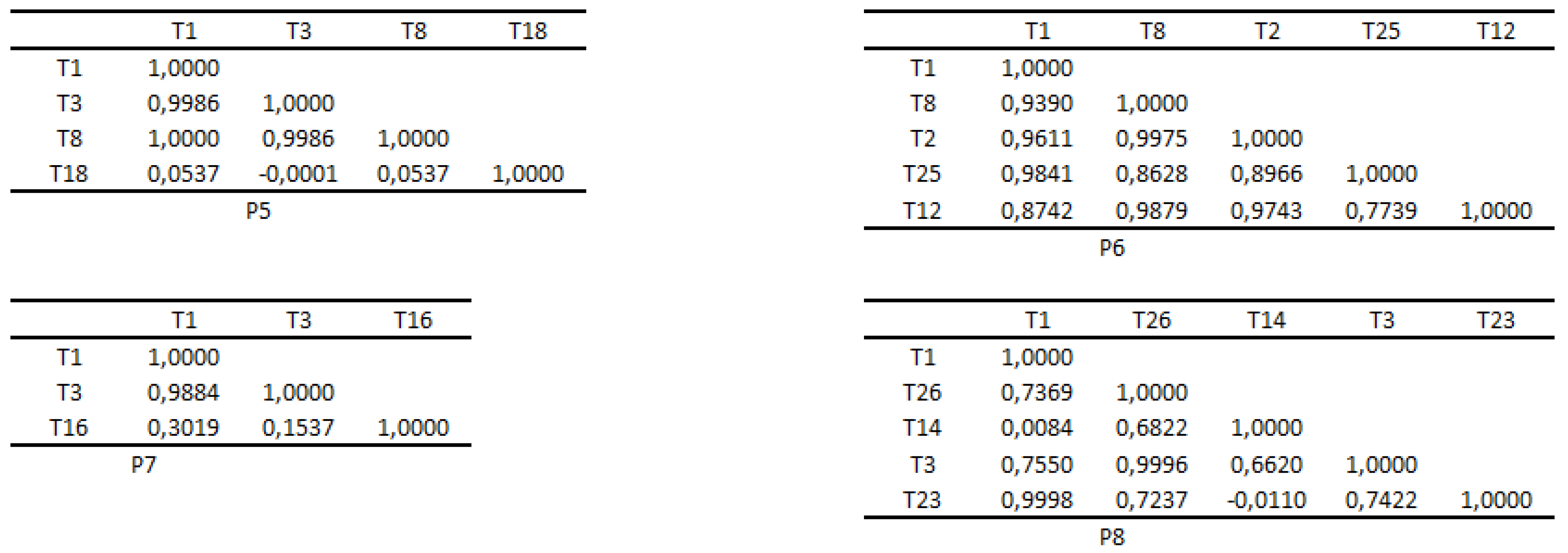

The cosine similarities presented in

Table 8 are a direct consequence of the representations of Sis and Tis in the semantic space. Naturally, the highest number of similarities with Tis (18) is recorded by S6 & S2 & S5. Following closely are S3 and S4 with the same number of similarities (16). The highest similarity was recorded between S3 and T26. This is due to their identical representations in the semantic space. Since Sis represents morbid experiences, the similarities presented in the table indicate dysfunctional pairs (Si,Tis) at the level of the group of patients. The table also highlights the presence of dissimilarities, for example between S3 and T9. We consider that the information provided by the table could be useful in symptom-focused group psychotherapy that should only take into account the dissimilar pairs (Sis,Tis). The effects of the similar pairs (Si,Tis) manifest in the perpetuation and accentuation of dysfunctional symptoms.

At the level of the group of patients, the premise of the simultaneous activation of happiness, unhappiness, and daily themes was tested by identifying strong and significant positive associations between Tis that belong to the three life themes. The correlations presented below confirmed this premise. There are many more such correlations in

Table A2.

T1−T2, =1.0000, p=0.0004; T2−T12, =0.8214, p=0.0341; T1−T12, =0.8214, p=0.0341; T2−T16, =1.0000, p=0.0004; T1−T16, =1,0000 p=0.0004; T2−T21, =1.0000, p=0.0004; T1−T21, =1.0000, p=0.0004; T2−T24, =0.9643, p=0.0028; T1−T24, =0.9643, p=0.0028; T2−T25, =0.8929, p=0.0123; T1−T25, =0.8929, p=0.0123; T1−T3, =0.8571, p=0.0238; T3−T21, =0.8571, p=0.0238; T3−T16,=0.8571, p=0.0238; T1−T7, =1.0000, p=0.0004; T7−T12, =0.8214, p=0.0341; T7−T16, =1.0000, p=0.0004; T7−T21,=1.0000, p=0.0004; T7−T24,=0.9643, p=0.0028; T7−T25, =0.8929, p=0.0123; T1−T8, =1.0000, p=0.0004;

T8−T12, =0.8214, p=0.0341; T8−T16, =1.0000, p=0.0004; T8−T21, =1.0000, p=0.0004; T8−T24, =0.9643, p=0.0028; T8−T25, =0.8929, p=0.0123

Other strong and significant correlations highlight associations between life subthemes within the same theme. Also, this table signals the presence of weak and negative correlations.

What can we say about the premise of the simultaneous activations of Tis at patient level? The

Table 9Table 10 indicate the following aspects:

for P1, the following significant associations were identified: T1 - T19, similarity=1.0000, =1.0000 and p=0.0008; T1 - T5, similarity=0.9995, =0.7818 and p=0.0468; T19 - T5, similarity=0.9996, =0.7818 and p=0.0468; T5 - T17, similarity=0.8856, =0.9636 and p=0.0032; T17 - T18, similarity=0.9140, =0.7818 and p=0.0492; T2 - T18, similarity=0.9483, =0.9636 and p=0.004. All these associations suggest a high probability of the manifestation of the dysfunctional subthematic cycle T1 - T19 - T5.

for P2, the following significant associations were identified: T13 - T3, similarity=0.9902, =0.9643 and p=0.0028; T13 - T22, similarity=0.9851, =1.0000 and p=0.0004; T13 - T21, similarity=0.9998, =0.9643 and p=0.0028; T6 - T16, similarity=0.9023, =0.9286 and p=0.0067; T3 - T22, similarity=0.9514, =0.9643 and p=0.0028; T3 - T21, similarity=0.9925, =1.0000 and p=0.0004; T22 - T21, similarity=0.9819, =0.9643 and p=0.0028. These associations suggest a high probability of the manifestation of the dysfunctional subthematic cycles, T3 - T13 - T21 and T3 - T13 - T21 - T22. Additionally, these cycles associate the happiness, unhappiness, and daily themes.

for P4, the absence of the daily life theme suggests his inability to escape suffering through everyday life, which signifies a severe impairment due to illness. Significant subtheme associations are: T1 - T9, similarity=0.9965, =0.9643 and p=0.0028; T1 - T10, similarity=0.9044, =0.7857 and p=0.0480; T1 - T3, similarity=0.9640, =0.7857 and p=0.0480; T10 - T3, similarity=0.9853, =1.0000 and p=0.0004. The results indicate a high probability of the manifestation of the dysfunctional subthematic cycle T1-T3-T10.

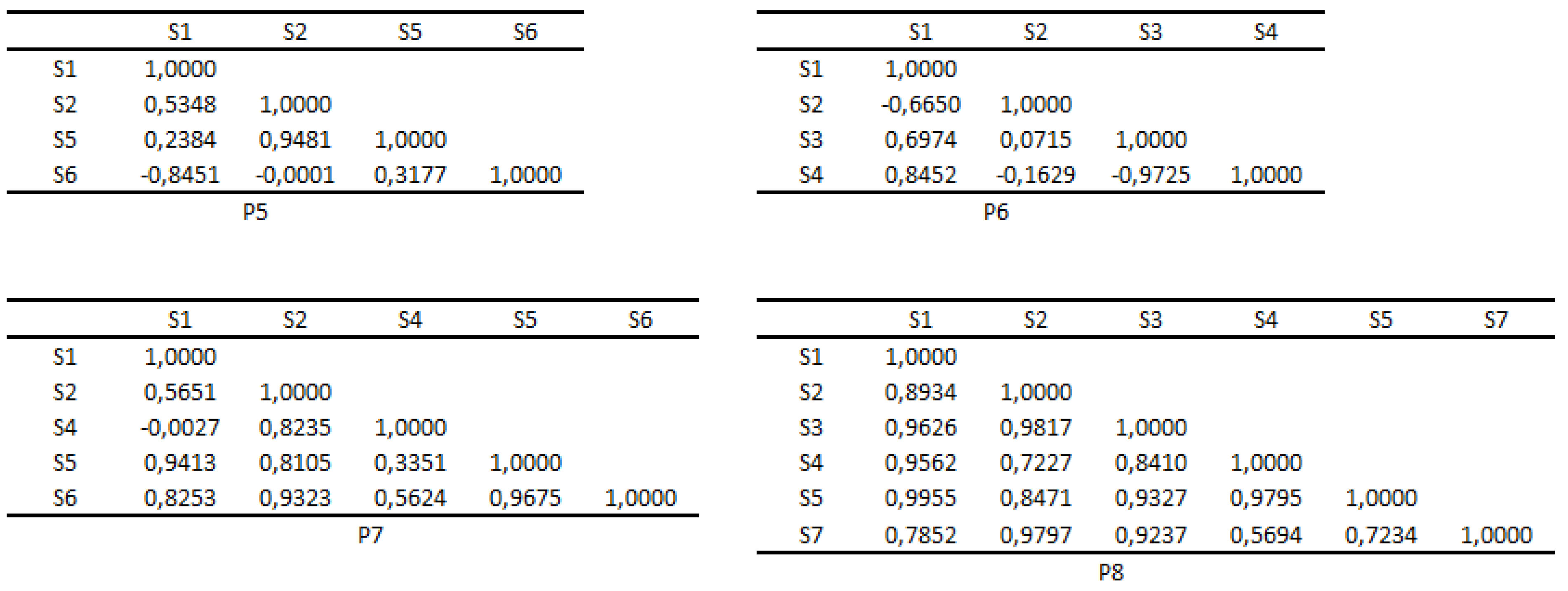

for P5, a significant association T1 - T8, similarity=1.0000, =1.0000 and p=0.0024 was identified.

for P6, a significant association T1 - T8, similarity=0.9390, =0.8846 and p=0.0119 was identified.

for P7, a significant association T1 - T3, similarity=0.9884, =0.8545 and p=0.0222 was identified.

for P8, a significant association T3 - T26, similarity=0.9996, =0.9643 and p=0.0028 was identified.

for P9, two significant associations T1 - T21, similarity=0.9991, =0.9643 and p=0.0028; T3-T13, similarity=0.9256, =0.8929 and p=0.0123 were identified.

for P10, a significant association T14 - T15, similarity=0.9801, =0.9636 and p=0.004 was identified..

In conclusion, at patient level, the possibility of simultaneous associations of more than two Tis, and also of the themes of happiness, unhappiness and everyday life is confirmed. Additionally, there are no significant positive associations between dissimilar Tis.

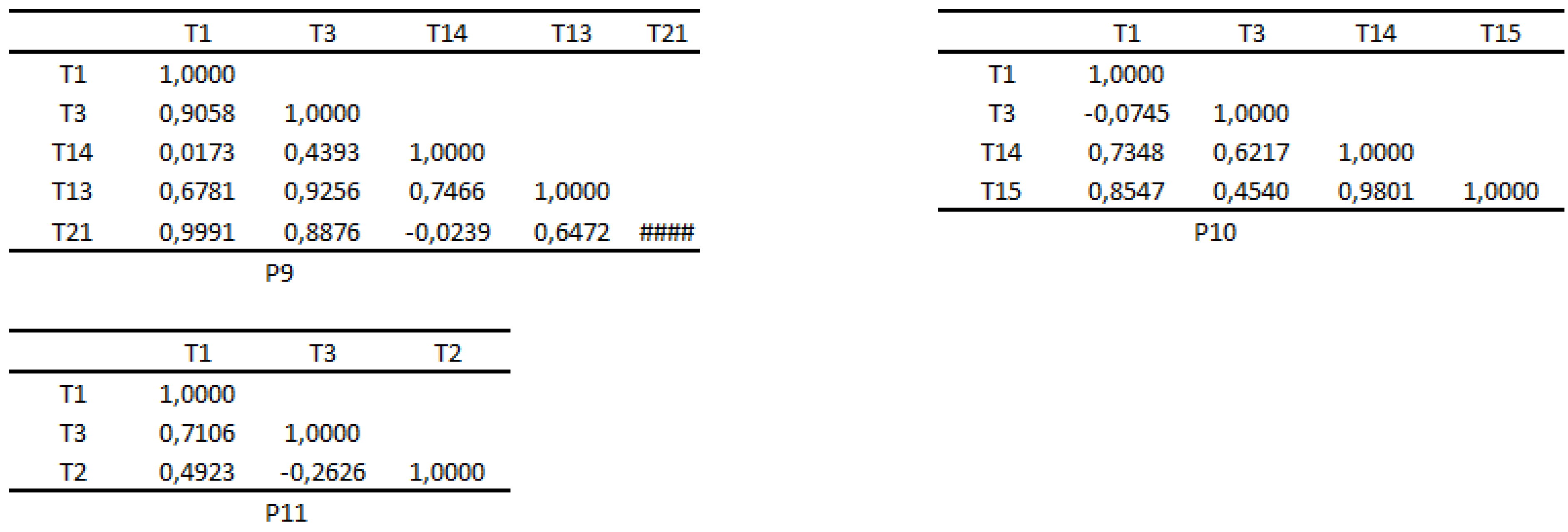

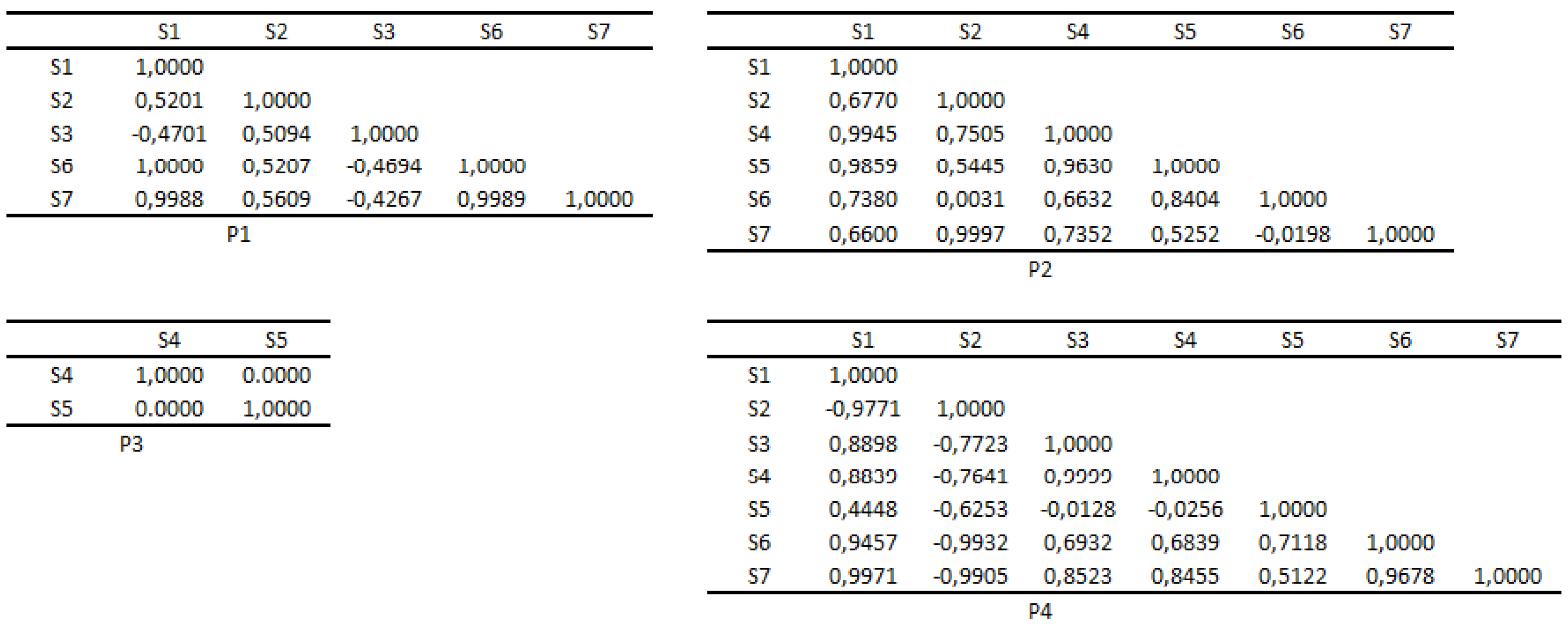

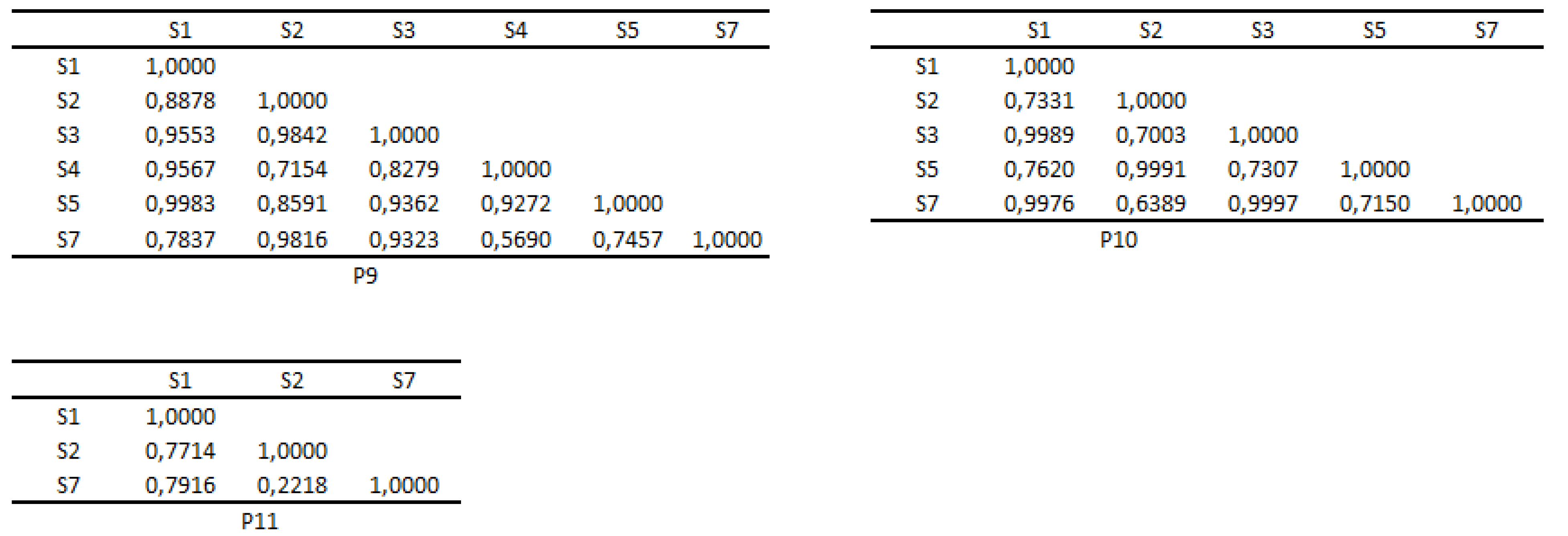

At patient level, the combined analysis of similarities and correlations between Sis yields the following conclusions:

-

for P1, there are four significant correlations: S1-S6, similarity=1.0000, =1.0000, p=0.0001; S1-S7, similarity=0.9988, =1.0000, p=0.0001; S6-S7, similarity=0.9989,

=1.0000, p=0.0001; S2-S3, similarity=0.5094, =0.7831, p=0.0264. These data indicate a very high probability of the manifestation of the dysfunctional symptomatic cycle S1-S6-S7.

for P2, there are four significant correlations: S1-S4, similarity=0.9945, =0.9429, p=0.0167; S1-S5, similarity=0.9859, =1.0000, p=0.0028; S4-S5, similarity=0.963, =0.9429, p=0.0167; S2-S7, similarity=0.9997, =1.0000, p=0.0028. These data indicate a very high probability of the manifestation of the dysfunctional symptomatic cycle S1-S4-S5. Additionally, with a high probability, the patient simultaneously experiences S2 and S3.

for P4, there are four significant correlations: S1-S2, disimilarity=−0.9771, =−1.0000, p=0.0167; S1-S7, similarity=0.9971, =1.0000, p=0.0167; S2-S7, disimilarity=−0.9905, =−1.0000, p=0.0167; S3-S4, similarity=0.9999, =1.0000, p=0.0167. These data indicate, with a high probability, the patient’s tendency to experience S7 in a pure (undistorted) manner and in combination with S1. Additionally, the patient shows a tendency to experience S2 in a pure manner, and to experience S3 and S4 in a combined manner.

for P8, there are two significant correlations: S1-S5, similarity=0.9955, =1.0000, p=0.0167; S2-S3, similarity=0.9817, =1.0000, p=0.0167. These data indicate, with a very high probability, the simultaneous experiencing of S1 and S5, as well as of S2 and S3.

for P9, there are two significant correlations: S1-S5, similarity=0.9983, =1.0000, p=0.0167; S2-S3, similarity=0.9842, =1.0000, p=0.0167. These data indicate, with a very high probability, the simultaneous experiencing of S1 and S5, as well as of S2 and S3.

To summarise, at the level of Sis and the analyzed patients, we can conclude that there are no significant positive associations between dissimilar Sis. Additionally, there is a possibility of the manifestation of dysfunctional symptomatic cycles, as well as the pure (undistorted) and combined experiencing of Sis.

Clearly, a larger number of patients yields greater consistency to the findings. Our intention was to describe, through a computational approach, the specific manner of manifestation of the relationship between symptoms and life themes at the level of patient/group of patients. We consider that our findings can be useful in the patient psychotherapy. In the long run, our concerns aim to assess the specific effect of the associations of dissimilarities on the quality of the life of patients, and to identify patterns of heightened or diluted experience as a result of these associations.