Submitted:

17 October 2023

Posted:

18 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- To define the features of ASD.

- To review and compare experiences in the use of drama in people diagnosed with ASD.

- To justify the proposal to apply all kinds of theatrical techniques to people with ASD based on scientific evidence.

Problem Statement

2. Methods

- -

- theater AND intervention AND autism

- -

- dramatic art AND autism

- -

- theater AND autism spectrum

- -

- theater AND asperger

- -

- teatro Y intervención Y autismo

- -

- arte dramático Y autismo

- -

- teatro Y espectro autista

- -

- asperger Y teatro

- -

- without the words (training/assistant/public/teachers)

- -

- exact wording (autism spectrum)

3. Results

| Authors and year | Type of intervention | Sessions/Duration | Sample | Results | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beadle-Brown et al. [23] | Multisensory capsule improvisation games | 10 45-min sessions, 1 weekly/10 weeks |

22 individuals with ASD (7-12 years old) |

Development of social interaction, communication, and imagination. | 0.8 |

| Blanco et al. [30] | Weekend extracurricular theater workshop | 6 of 1 h and 30 min 1 fortnightly/12 weeks |

7 individuals with Asperger’s (14-18 years old) |

Increased social skills, sense of belonging to a group, improved self-esteem, empathy and listening skills. | NR |

| Calafat-Selma et al. [31] | Extracurricular theater | 27 50-min sessions, 2 weekly/16 weeks |

2 individuals with ASD and 7 with intellectual disability | Improvements in speech, relationship and play. Adaptation level without significant improvement. |

NR |

| Corbett et al. [33] | Theatrical intervention program | 38 2-hour sessions, 4 weekly/12 weeks |

8 individuals with ASD and 8 normotypical individuals (6-17 years old) |

Improved social-emotional functioning. | NR |

| Corbett et al. [20] | Summer camp | 10 4-hour sessions, 5 weekly/2 weeks |

11 individuals with ASD and Asperger’s (8-17 years old) |

Increased active participation with peers. Improved facial identification and memory. |

NR |

| Corbett et al. [32] | Weekend theater workshop | 10 4-hour sessions, 1 weekly/10 weeks |

30 individuals with ASD and 30 normotypical individuals (8-14 years old) |

Decrease in stress and anxiety. | NR |

| Corbett et al. [34] | Weekend theater workshop for young people | 10 4-hour sessions, 1 weekly/10 weeks |

77 individuals with ASD (8-16 years old) |

Improvements in theory of mind, facial memory and cooperative gameplay. | NR |

| Fein [21] | Theater workshop, at summer camp | NR | Individuals with ASD (11-18 years old) |

Improved personal relationships. | NR |

| Fernández-Aguayo and Pino-Juste [27] | Theatrical exercises in an early care center | 16 1-hour and 10-min sessions, 1 weekly/16 weeks |

9 ASD/social communication disorder/cognitive deficiency (3-4 years old) |

Increased communication. Improved identification and representation of emotions. Ability to develop conversations. |

NR |

| Godfrey and Haythorne [7] | Dramatherapy program in various contexts | NR | 42 family members, educators and teachers of students with ASD | Increased confidence, self-esteem, social skills, communication skills, creativity and imagination. | NR |

| Goldstein et al. [12] | Musical theater in a special education center | 40 sessions throughout the school year | 36 individuals with ASD (3-12 years old) |

Improved social relations and behavioral skills. | NR |

| Guli et al. [35] | Creative theater workshop | 12 2-hour session, 1 weekly/12 weeks 16 1.5-hour sessions, 2 weekly/8 weeks |

11 individuals with ASD, 2 with nonverbal learning disability and 5 with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (8-14 years old) |

Improved interpersonal relationships. Increased empathy and self-control. |

NR |

| Kempe and Tissot [6] | Intervention program in a special education center | 13 1-hour and 40-min sessions over 20 weeks |

10 individuals with learning difficulties and 2 with ASD (18-19 years old) |

Increase in social skills. Development of creative skills. |

NR |

| Lerner et al. [22] | Sociodramatic intervention based on improvisation in a summer program | 29 5-hour sessions, 1 daily/6 weeks |

17 individuals with Asperger’s and high-functioning individuals with ASD (11-17 years old) |

Improved social skills. | NR |

| Lewis and Banerjee [25] | Storytelling in drama therapy at a special education school | 12 60-min sessions, 10 group and 2 individual sessions/12 weeks |

3 individuals with ASD (12-14 years old) |

Increased security, confidence, self-esteem, insight and empathy. | NR |

| Madriz et al. [14] | Theater workshop for young people | 95 1.5-hour sessions, 1 weekly/95 weeks |

8 individuals with ASD (12-22 years old) |

Increased emotional expression and assertive communication. | NR |

| Mandelberg et al. [40] | Social skills program | 12 1-hour sessions, 1 weekly/12 weeks |

24 high-functioning individuals with ASD and normotypical peers (6-11 years old) |

Reduction of conflicts in the game. Improved emotional management. |

NR |

| Martín [28] | Shadow theater in an early care center | 30 50-min sessions, 3 weekly/10 weeks |

1 individual with ASD (6 years old) |

Improved communicative intent and emotional state. Increased body awareness. |

NR |

| Massa et al. [15] | Theatrical production | 2 months | 2 individuals with ASD, 1 with anxiety disorder (18-29 years old) |

Reduction of autism stigma. | NR |

| May [36] | Comedy and clown workshops | NR | 5 individuals with ASD and 4 normotypical individuals (13-16 years old) |

Myth of autistic humorlessness debunked. | NR |

| Mehling et al. [37] | Extracurricular theater workshop | 10 1-hour sessions, 1 weekly/10 weeks |

14 individuals with ASD (10-13 years old) |

Improved social interaction, pragmatic language, and facial emotional recognition. | NR |

| Mpella et al. [13] | Theater program as part of the school’s physical education program | 16 45-min sessions, 2 weekly/8 weeks |

6 individuals with ASD and 132 normotypical peers in their respective classrooms (9-11 years old). |

Improved cooperation, attention and empathy. Reduction of anxiety and repetitiveness. |

NR |

| Dyer [24] | Dramatherapy in elementary school | 8 45-min sessions, 1 weekly/8 weeks |

3 individuals with ASD and 3-5 normotypical individuals (5-11 years old) |

Increased confidence and self-esteem. Improved turn-taking and skills to work effectively alone and with others. |

NR |

| O’Sullivan [8] | Weekend dramatherapy workshop | 10 90-min sessions, 1 weekly/10 weeks |

12 individuals with Asperger’s (9-11 years old) |

High levels of activity and interest. Emotional and physical collapse of a participant. |

NR |

| Pimpas [29] | Social skills training program | 1 45-min session, 1 weekly/1 year |

1 individual with ASD (9 years old) |

Correct display of emotions and affections. Greater expressiveness. |

NR |

| Sandoval and Hernández [38] | Theater and digital fabrication workshop | 16 1.5-hour sessions, 1 weekly/16 weeks |

10 individuals with ASD (12-20 years old) |

Improvements in the expression of emotions and teamwork. | NR |

| Trowsdale and Hayhow [26] | Psychophysical theater during school hours in a special education center | 1 1-hour session, 1 weekly/5 years |

Variety of students with learning difficulties, ASD among others (3-11 years old) |

Improved communication and socialization skills. New collaboration skills. |

NR |

| Villanueva-Bonilla et al. [11] | Social role play | 25 60-min sessions, 2 weekly/13 weeks |

3 individuals with ASD (8-10 years old) |

Positive changes in identification, understanding and emotional expression. | NR |

| Wilmer-Barbrook [39] | Dramatherapy | 36 1.5-hour sessions, 1 weekly/36 weeks |

8 individuals with Asperger’s (16-24 years old) |

Increased confidence, self-esteem, social skills, emotional expression, and communication skills. | NR |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Section and topic | Item | Checklist item | Location where item is reported |

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | 4 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | 5-12 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | 11-12 |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | 14 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organizations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | 13 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | 13 |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and, if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 14 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and, if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 14 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g. for all measures, time points, analyses) and, if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | NA |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | NA | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and, if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | NA |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | NA |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing to the planned groups for each synthesis). | NA |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics or data conversions. | NA | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | NA | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | NA | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, metaregression). | NA | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | NA | |

| Assessment of information bias | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | NA |

| Deficiency assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | NA |

| RESULTS | |||

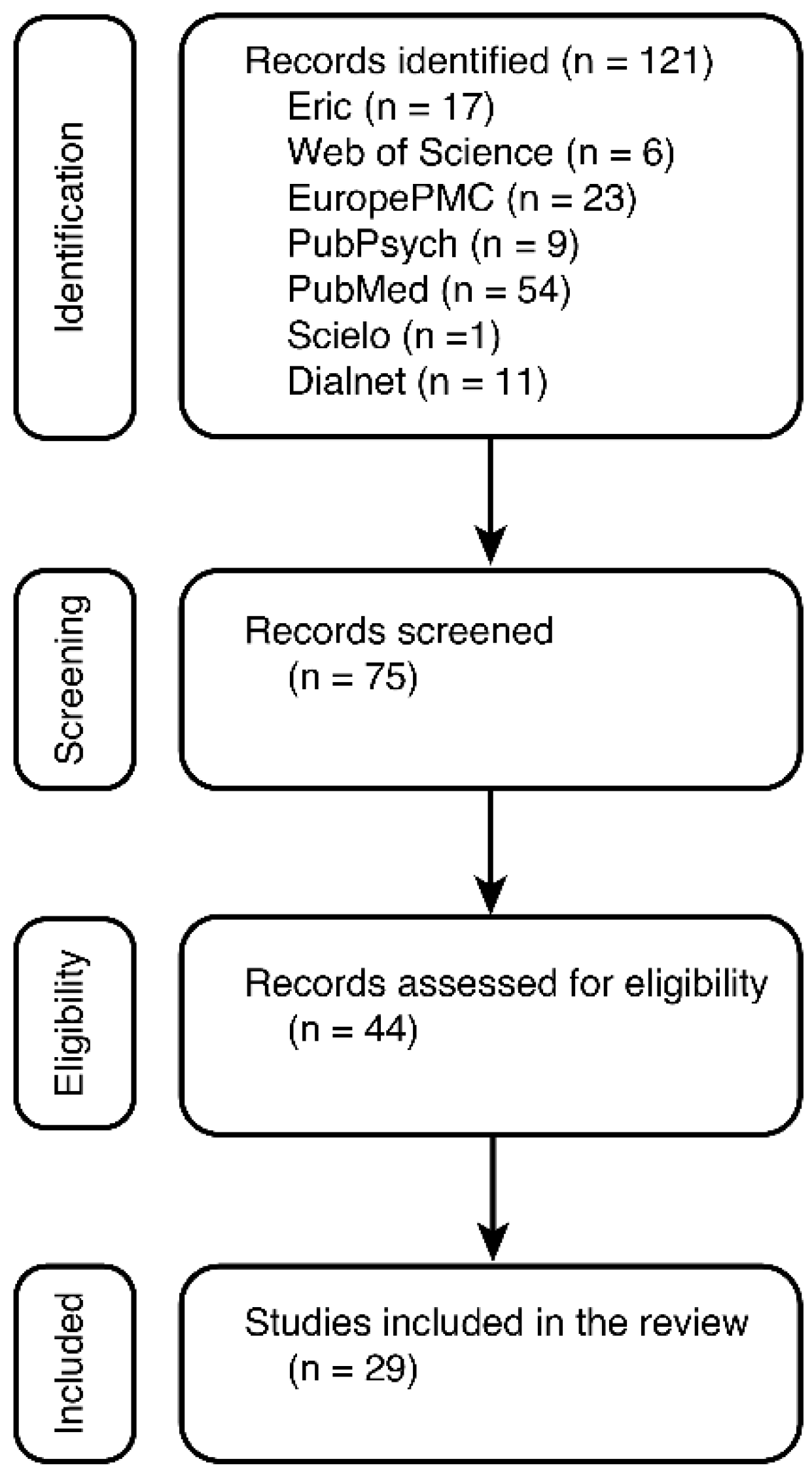

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | 34 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria but were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | NA | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | 31-33 |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | NA |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study, (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | NA |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarize the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | NA |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | NA | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | NA | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | NA | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | NA |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | NA |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | 18-22 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | 21 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | 21 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | 21-22 | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | NA |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | NA | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | NA | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or nonfinancial support for the review and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | 22 |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | 22 |

| Availability of data, code, and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms, data extracted from included studies, data used for all analyses, analytic code, any other materials used in the review. | NA |

References

- Asociación Americana De Psiquiatría. Manual de Diagnóstico y Estadística de Trastornos Mentales, 5th ed.; Editorial Médica Panamericana: Arlington, Estados Unidos, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Merrell, K.W.; Gimpel, G.A. Social Skills of Children and Adolescents: Conceptualization, Assessment, Treatmented.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, US, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ares, D.A.; Bermudez, L.M.; Chinchill, R.H. Neurodidáctica y estrategias de aprendizaje para la inclusión. Desarrollo de competencias comunicativas en niños y niñas con riesgo biológico y/o social. Rev. Educ. Inclusiva 2017, 9, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- López-Vázquez, A.R. Aprender a ver teatro, empezar a hacer teatro. Prim. Not., Rev. Lit. 2008, 233, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kempe, A.; Tissot, C. The use of drama to teach social skills in a special school setting for students with autism. Support Learn. 2012, 27, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, E.; Haythorne, D. Benefits of dramatherapy for autism spectrum disorder: A qualitative analysis of feedback from parents and teachers of clients attending roundabout dramatherapy sessions in schools. Dramatherapy 2013, 35, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, C. Drama and Autism. In Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders, Volkmar, F.R., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Conn, C. Play and Friendship in Inclusive Autism Education: Supporting Learning and Developmented; Routledge: Abingdon Oxon, NY, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, M.A.E.; de Oliveira, R.F.T. A arteterapia no tratamento do transtorno do espectro autista (TEA). Rev. Cient. Univ. 2016, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva-Bonilla, C.; Bonilla-Santos, J.; Ríos-Gallardo, Á.M.; Solovieva, Y. Desarrollando habilidades emocionales, neurocognitivas y sociales en niños con autismo. Evaluación e intervención en juego de roles sociales. Rev. Mex. Neurocienc. 2018, 19, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, T.R.; Lerner, M.D.; Paterson, S.; Jaeggi, L.; Toub, T.S.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Golinkof, R. Stakeholder perceptions of the effects of a public school-based theatre program for children with ASD. J. Learn. Through Arts 2019, 15, n1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpella, M.; Evaggelinou, C.; Koidou, E.; Tsigilis, N. The effects of a theatrical play programme on social skills development for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2019, 33, 828–845. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez, L.M.M.; Poveda, A.S.; Rojas, V.G.; Ares, P.A. Teatro para convivir: Investigación-acción para el desarrollo de habilidades sociales en jóvenes costarricenses con trastorno del espectro autista. Rev. Esp. Discapac. 2019, 7, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, A.; DeNigris, D.; Gillespie-Lynch, K. Theatre as a tool to reduce autism stigma? evaluating ’Beyond Spectrums’. Res. Drama Educ. J. Appl. Theatre Perform. 2020, 25, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavista-Rof, C.; Mora-Giral, M. Prevención y tratamiento de los trastornos mentales a través del teatro: Una revisión. Rev. Psicol. Clín. Con Niños Adolesc. 2019, 6, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, C. Improvisational theatre and occupational therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2021, 68, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, T.R. Correlations among social-cognitive skills in adolescents involved in acting or arts classes. Mind Brain Educ. 2011, 5, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, B.A.; Swain, D.M.; Coke, C.; Simon, D.; Newsom, C.; Houchins-Juarez, N.; Jenson, A.; Wang, L.; Song, Y. Improvement in social deficits in autism spectrum disorders using a theatre-based, peer-mediated intervention. Autism Res. 2014, 7, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fein, E. Making meaningful worlds: Role-playing subcultures and the autism spectrum. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 2015, 39, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, M.D.; Mikami, A.Y.; Levine, K. Socio-dramatic affective-relational intervention for adolescents with asperger syndrome & high functioning autism: Pilot study. Autism 2011, 15, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beadle-Brown, J.; Wilkinson, D.; Richardson, L.; Shaughnessy, N.; Trimingham, M.; Leigh, J.; Whelton, B.; Himmerich, J. Imagining autism: Feasibility of a drama-based intervention on the social, communicative and imaginative behaviour of children with autism. Autism 2018, 22, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, N. Behold the tree: An exploration of the social integration of boys on the autistic spectrum in a mainstream primary school through a dramatherapy intervention. Dramatherapy 2017, 38, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.; Banerjee, S. An investigation of the therapeutic potential of stories in dramatherapy with young people with autistic spectrum disorder. Dramatherapy 2013, 35, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowsdale, J.; Hayhow, R. Psycho-physical theatre practice as embodied learning for young people with learning disabilities. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2015, 19, 1022–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Aguayo, S.; Pino-Juste, M. Trastornos del desarrollo y dramatización: Descripción de una experiencia teatral en un centro de Atención Temprana. In Atención Temprana y Educación Familiar, IV Congreso Internacional; Buceta, M.J., Crespo, J.M., Eds.; Servicio de Publicaciones e Intercambio Científico de la Universidade de Santiago de Compostela: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2015; pp. 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, L.M. Intervención de teatro de sombras en un caso con necesidades educativas especiales por trastorno de espectro autista. Rev. Educ. Univ. Granada 2018, 25, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimpas, I. A psychological perspective to dramatic reality: A path for emotional awareness in autism. Dramatherapy 2013, 35, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.B.; Barreiros, J.M.R.; Sanmamed, M.G. El teatro como herramienta socializadora para personas con Asperger. Rev. Esp. Orientac. Psicopedag. 2016, 27, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafat-Selma, M.; Sanz-Cervera, P.; Tárraga-Mínguez, R. El teatro como herramienta de intervención en alumnos con trastorno del espectro autista y discapacidad intelectual. Rev. Educ. Inclusiva 2016, 9, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, B.A.; Blain, S.D.; Ioannou, S.; Balser, M. Changes in anxiety following a randomized control trial of a theatre-based intervention for youth with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2017, 21, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, B.A.; Gunther, J.R.; Comins, D.; Price, J.; Ryan, N.; Simon, D.; Schupp, C.W.; Rios, T. Brief report: Twiheatre as therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2011, 41, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, B.A.; Ioannou, S.; Key, A.P.; Coke, C.; Muscatello, R.; Vandekar, S.; Muse, I. Treatment effects in social cognition and behavior following a theater-based intervention for youth with autism. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2019, 44, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guli, L.A.; Semrud-Clikeman, M.; Lerner, M.D.; Britton, N. Social competence intervention program (SCIP): A pilot study of a creative drama program for youth with social difficulties. Arts Psychother. 2013, 40, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, S. Autism and comedy: Using theatre workshops to explore humour with adolescents on the spectrum. Res. Drama Educ. J. Appl. Theatre Perform. 2017, 22, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, M.H.; Tassé, M.J.; Root, R. Shakespeare and autism: An exploratory evaluation of the Hunter Heartbeat Method. Res. Pract. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 4, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda, A.S.; Montoya, D.H. Digital fabrication and theater: Developing social skills in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 615786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmer-Barbrook, C. Adolescence, Asperger’s and acting: Can dramatherapy improve social and communication skills for young people with Asperger’s syndrome? Dramatherapy 2013, 35, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelberg, J.; Frankel, F.; Cunningham, T.; Gorospe, C.; Laugeson, E.A. Long-term outcomes of parent-assisted social skills intervention for high-functioning children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2014, 18, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).