Introduction

Currently, interest in materials from the NASICON family is increasing due to the possibility of their use as structural materials, for example, as electrode materials in sodium-ion batteries (NIB) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Replacing lithium-ion batteries (LIB) with NIB will create an inexpensive technology for the production of current sources [

7,

8,

9,

10]. The key components of NIB are cathode materials, which mainly determine the final energy density and cost of the battery [

8,

9]. However, sodium-containing cathode materials in NIBs generate lower energy densities than LIBs because Na+ ions have a large ionic radius [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a technology for producing more efficient sodium-containing cathode materials for NIB [

9,

14,

15,

16].

Many polycrystals from the NASICON family are considered potential structural materials for creating NIB electrodes [

17,

18,

19]. Among this family, we can highlight Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3, which is an ionic conductor and a promising material for creating a NIB cathode [

2,

20]. The interest of researchers in Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 was aroused due to its structural features and superionic conductivity in the γ-phase [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. It was found that Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 has three phases (α, β, γ) and two phase transitions: α→β and β→γ. The anionic structure of this compound is a fragment of a three-dimensional rhombohedral framework {[Fe

2(PO

4)]

3-}

3∞. (called the “Japanese lantern”, formed by the junction of FeO

6 octahedra and PO

4 tetrahedra through the vertices) [

26,

27]. The presence of polyanion polyhedra leads to the formation of a crystalline framework with empty cavities of two types (M(1)) and (M(2)). These structures are characterized by the statistical filling of positions (M(1)) and (M(2)) with sodium cations [

26,

27]. Ionic conductivity is ensured due to the presence in the crystal frame of large cavities (M(1) and M(2)) forming “conduction channels” and the anionic sublattice of the crystal [

26,

27].

It should be noted that the structure of the three-dimensional rhombohedral crystalline frame of α- Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 at room temperature is ordered and monoclinically distorted (space group). After the phase transitions α→β and β→γ, a gradual increase in the symmetry of the crystal occurs (space group R = 3c) with simultaneous disordering of the cation sublattice and a uniform distribution of sodium cations over extensive cavities of the M(1) and M(2) types [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

For Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3, probabilistic paths for the diffusion of sodium cations in Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3, through the channels of the crystallographic framework were established [

25]. The relationship between phase transitions and the redistribution of sodium cations in the structure of Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3, is discussed in [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. A feature of the structure of the low-temperature α- Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3, phase is the presence of superstructural distortions and dipole ordering of the antiferroelectric type (AFE) [

23,

26]. Using Raman spectroscopy in α- Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3, bands due to vibrations of the phosphate anion and various ions were discovered [

20,

29].

At room temperature, the most thermosensitive modes are those located in the low-frequency range 100-400 cm-1, near 500 cm-1, and the modes corresponding to the stretching of the valence bond of the unit (PO4) lie in the frequency range 970-1200 cm-1. These data allow us to conclude that despite the “rigidity” of the anionic crystalline framework, we can talk about a certain degree of its “elasticity” due to the ability of the link (PO4) to shift and stretch.

Although the ionic conductivity of α-Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 is low, this phase is characterized by structural stability and thermal stability, which can contribute to small volumetric changes during the intercalation/deintercalation of Na ions in NIB. Therefore, α- Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3, is considered as a promising cathode material for NIB. However, so far cathode materials from α-Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 polycrystals synthesized by the solid-phase method in NIA generate a small specific capacity of 61 mAh g

−1 and are reduced to 57 mAh g

−1 after 500 cycles at a voltage of 2.5 V [

2]. Therefore, it is necessary to improve the conductive and electrochemical properties of α-Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3, by modifying its structure.

It was found that, depending on the technological regime of the synthesis of polycrystals, the α- Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 structure can be obtained in different modifications. It is known that Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 can crystallize both in the monoclinic C2/m and in the orthorhombic modification with sp. gr. 3R ̅cH [

2,

22,

24,

30]. It is likely that the formation of various forms of low-symmetry α- Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 crystals depends on the thermodynamic conditions of crystallization. These data allow us to assert that the structure of Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 is very sensitive to deformation, therefore they can form their crystal structures in one or another polymorphic modification.

It has already been shown that the synthesis of α- Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 under the influence of hydrostatic pressure partially increases the ionic conductivity of this compound as a result of partial removal of the monoclinic distortion of the crystalline framework during crystallization [

26,

27,

28].

The fact of an increase in the specific discharge capacity in NIA when using α-Na3Fe2(PO4)3, synthesized by hot pressing as a cathode material, was reported in [

28,

29,

30,

31]. In all likelihood, this is due to the fact that polycrystals with higher conductivity slightly accelerate the intercalation/deintercalation process during electrochemical processes in NIB. Another important factor in improving the quality of Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3, cathode material is the use of various synthesis methods. Thus, Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3, synthesized by the sol-gel method made it possible to increase the initial specific discharge capacity to 92.5 mAh g

–1 in NIB due to the porosity of the structure of the cathode material [

29,

30,

31,

32].

The sintering method under the influence of radiant energy of optical radiation has been tested for the production of a number of optical and HTSC ceramic materials but has not yet been tested for the production of orthophosphate polycrystals. The essence of the method of crucibleless zone melting by optical heating is given in [

33].

The results obtained during the synthesis of optical material under the influence of optical radiation (visible light) show that the structure and conductive properties of the sample are improved [

34]. Certain compositions of bismuth-containing HTSC ceramics prepared from glass phases synthesized under the action of optical radiation show that the structure and critical parameters of the samples are improved [

32,

33,

34,

35].

In this regard, the synthesis of Na3Fe2(PO4)3 by the melt method under the influence of optical radiation is of interest, because in this case, the thermodynamic conditions of synthesis differ significantly from the solid-phase method. To clarify the influence of thermodynamic factors during the synthesis of Na3Fe2(PO4)3 on the structure and conductive properties of this material, further study of the relationship between synthesis modes, structure, and conductive properties is necessary.

The work aims to study the structural features and conductive properties of Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals obtained by solid-phase synthesis and the melt method using concentrated optical radiation.

3. Results obtained and their discussion

Structural parameters of samples The synthesized samples had a light burgundy color and were ceramic tablets with a diameter of 10 mm and a thickness of 1.5 mm. The structural parameters of the resulting polycrystalline Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

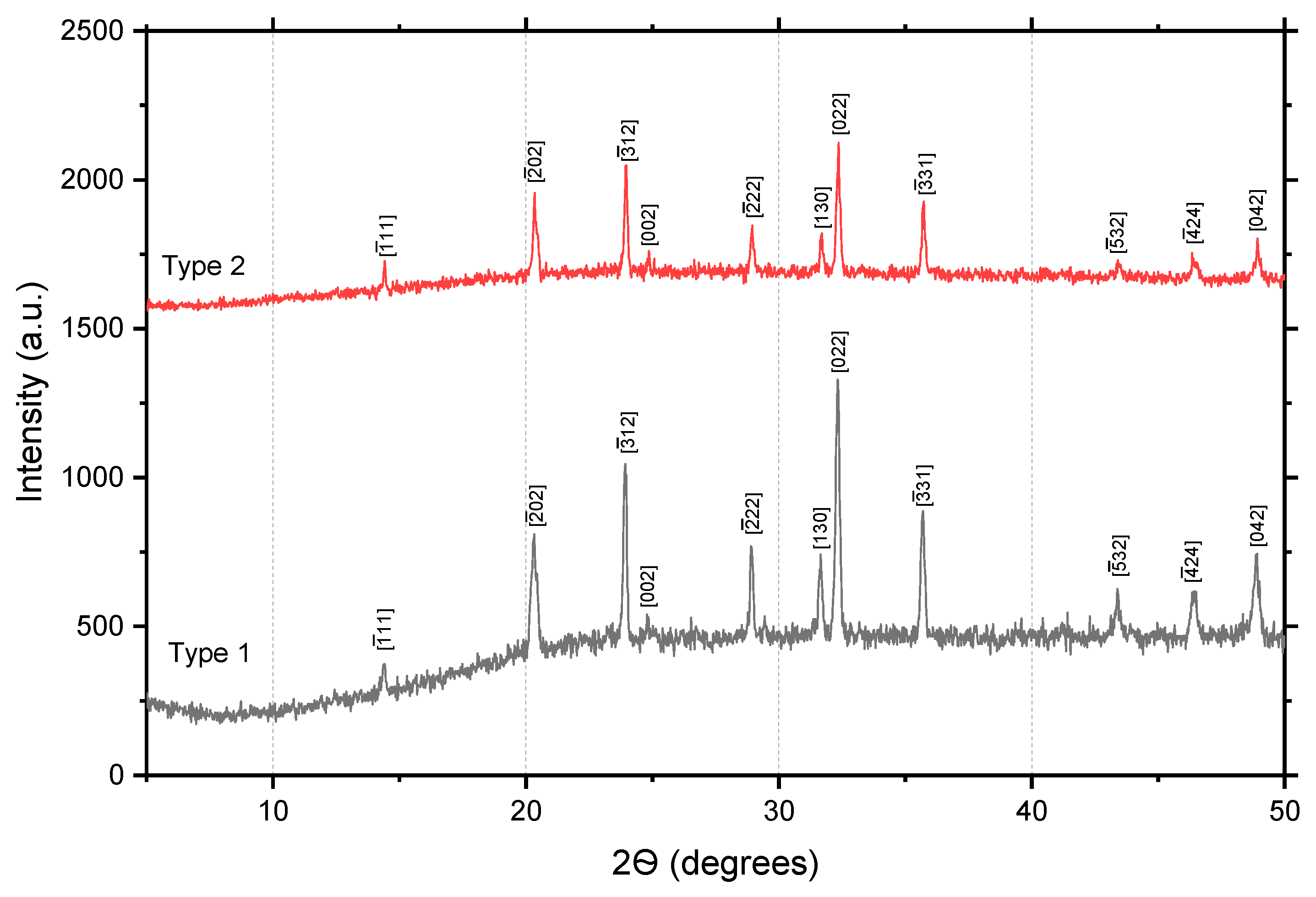

3 samples were studied by powder X-ray methods, using a diffractometer, and also using a Hitachi TM3030 scanning electron microscope with a Bruker microanalysis system. In

Figure 1 X-ray diffraction patterns of Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 samples of both types are presented.

The diffraction patterns of both polycrystals clearly show peaks at the corresponding X-ray scanning angles, but the intensity of the peaks of the type 2 sample is twice as high as that of type 1. This data indicates that the crystallites in type 2 polycrystals are better formed and more textured than in type 1 samples. The structural parameters of the samples were determined by analyzing the main peaks from the angular values using the Origin program. The calculated structural parameters of the samples are given in

Table 2.

Given in the

Table 2, the unit cell parameters for Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 polycrystals are comparable with the literature data of other authors [

2,

24,

28] and the data for a single crystal [

22] given in

Table 2. According to [

28], the monoclinic distortion of Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 polycrystals is associated with deformations of the anion and cation sublattices of the crystal frame, leading to compensated dipole orderings of the ASE type. It should be noted that the unit cell parameter b for a type 1 polycrystal is slightly increased; on the contrary, the parameters c and angle β are slightly reduced compared to the parameters of a type 2 sample. These changes in the structural parameters of Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 polycrystals may be associated with additional deformations of the dipole moments of unit cells caused by different thermodynamic synthesis conditions. According to the tabular data, monoclinic distortions of unit cells in samples of type 1 are less than in type 2.

Obviously, the nature of the primary firing plays a key role in the sample manufacturing process. For samples of type 1, the process of phase formation during primary firing occurred through heat transfer in the smooth heating mode of a muffle furnace. On the contrary, the phase formation of type 2 samples occurred under highly temperature-gradient conditions, because The sample was heated by intense radiation of powerful quantum pulses onto the surface of the sample. Therefore, under these conditions, a large temperature gradient will be created between the surface of the sample and its subsequent layers in the volume. Under such conditions, a cooling process occurs. Taking into account that the duration of the melting and cooling processes occurred for a short time, these factors could lead to the emergence of significant gradients of mechanical stress on the surface and in the volume of the sample.

Thus, the melt process and the transition from a liquid melt to a solid glassy state occurs under clearly nonequilibrium thermodynamic conditions. Apparently, despite the secondary annealing of the sample at a moderate temperature, residual deformations remain in the polycrystal after firing. The presence of residual deformations in a type 2 sample may be the reason for a partial decrease in monoclinic distortion.

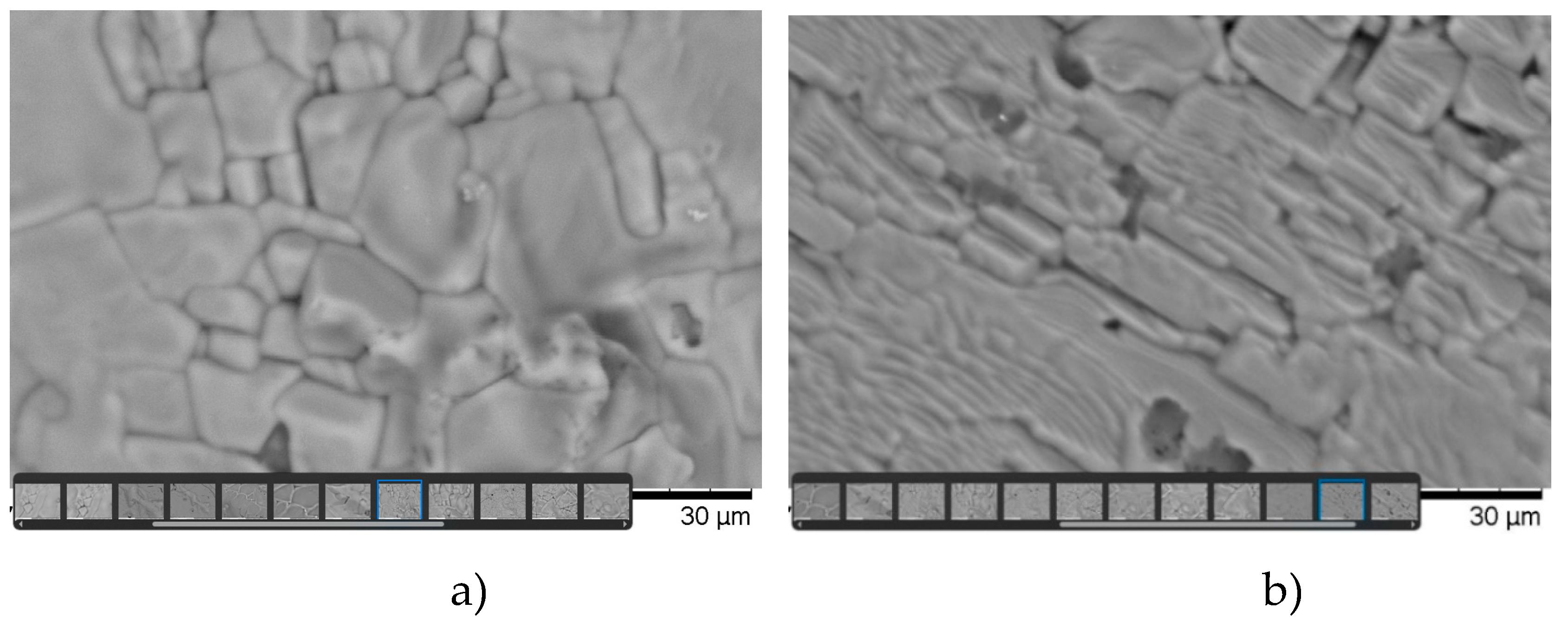

The study of the microstructure and elemental analysis of the synthesized samples made it possible to determine the distinctive features of the structure and composition of each sample. Data on the microstructures of polycrystals of the first and second types are shown in

Figure 2 a and b.

Based on microstructural and X-ray phase analysis, it can be concluded that the texture of type 2 polycrystals is significantly higher than that of type 1 samples. The crystallites of polycrystals of type 2 have a clear ordered-directional character, in contrast to samples of type 1, which are characterized by the absence of directional order in the arrangement of crystallites. It is obvious that nonequilibrium temperature-gradient conditions create such deformations that remain during the crystallization process (during the secondary firing of the sample) and affect the formation of the direction of crystallites in the polycrystal. We can talk about the influence on the sample of mechanical pressure created by a “chemical press” (similar to the pressure created by a hydraulic press). From this point of view, such an effect cannot be achieved under equilibrium temperature firing conditions (when firing type 1 samples). Also, type 1 samples are characterized by a noticeably pronounced heterogeneity of crystallites in size and the unevenness of their distribution over the surface of the sample.

Microstructures of polycrystals, it can be concluded that type 2 samples have a higher degree of crystallinity and texture than type 1 samples.

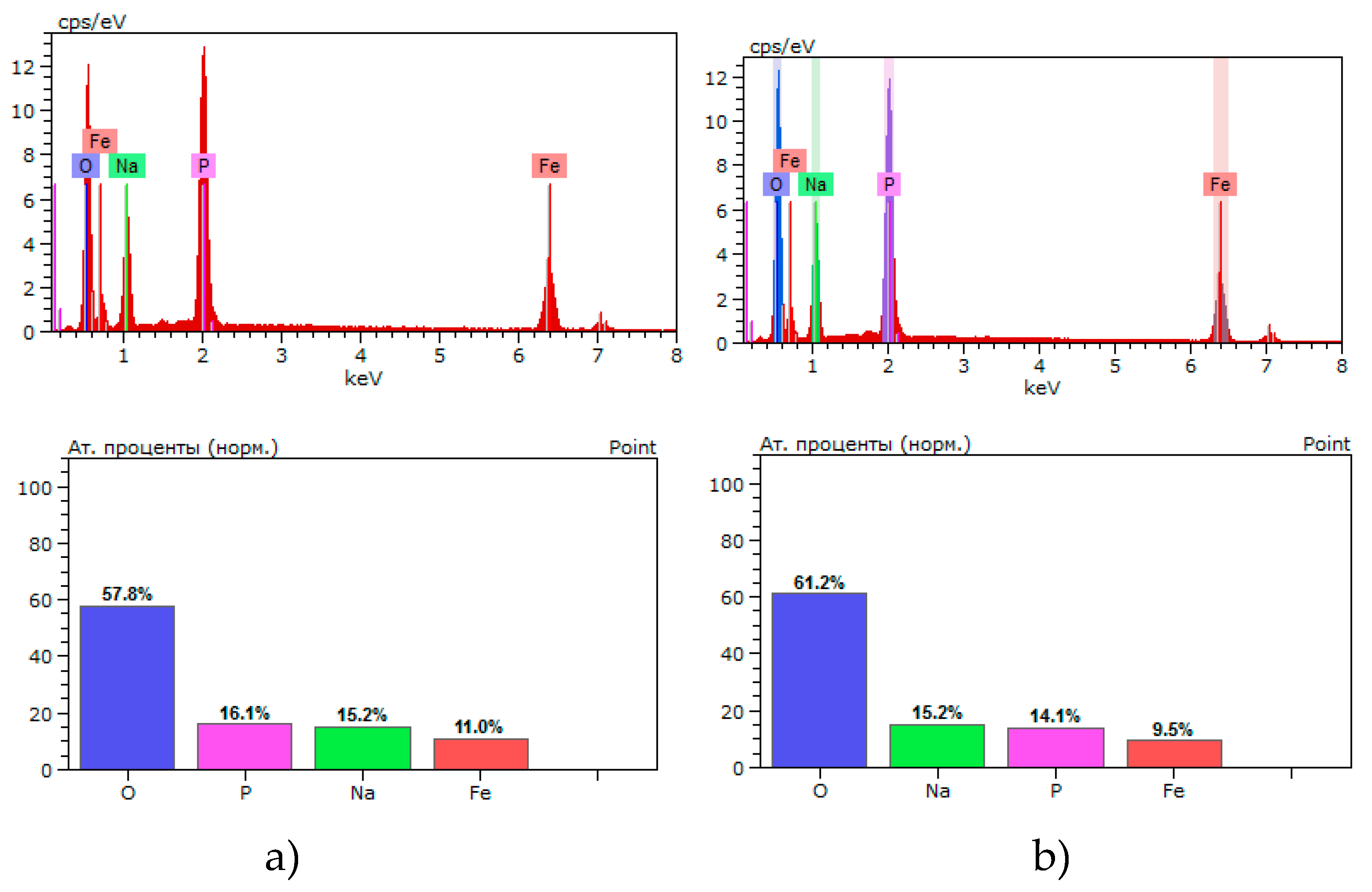

According to the elemental composition of polycrystals, a violation of the stoichiometric ratio of atoms is observed. The results of the elemental composition of polycrystals are shown in

Figure 2 and Table 3. Table 3. Values of the elemental composition of Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 polycrystals of types 1 and 2

Figure 3.

Percentage of elemental composition for Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals obtained by the solid-phase method: a) sample 1 type; melt method b) type 2 sample.

Figure 3.

Percentage of elemental composition for Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals obtained by the solid-phase method: a) sample 1 type; melt method b) type 2 sample.

Table 3.

Average values of the elemental composition of amorphous precursors (Аtom %).

Table 3.

Average values of the elemental composition of amorphous precursors (Аtom %).

| Composition |

Атoм % |

О |

Р |

Fe |

Na |

Na3Fe2(PO4)3 1-st type

Na3Fe2(PO4)3 2-nd type |

atom % |

61,20 |

15,20 |

9,50 |

15,20 |

| norm % |

61,18 |

15.22 |

9.51 |

15.22 |

| fact % |

- 0.0003 |

+ 0.0013 |

+ 0.01 |

+0.0013 |

| Na3Fe2(PO4)3 type - 2 |

norm % |

57,80 |

16,10 |

11,00 |

15,20 |

| fact % |

57,76 |

16,06 |

11,00 |

15,18 |

| Atom % |

- 0.0006 |

- 0.002 |

0 |

- 0.0013 |

Analysis of the results of studying the elemental composition of polycrystals of types 1 and 2 shows that there are minimal or no deviations from the norm in the content of Fe cations. In the case of type 1 samples, the content of Na and P, Fe cations turned out to be slightly higher relative to the stoichiometric composition. On the contrary, for type 2 samples the content of Na and P cations turned out to be lower than for the stoichiometric composition. Moreover, there is a slight lack of oxygen in samples of both types. The lack of Na and P cations in type 2 samples can be explained by the fact that under extreme temperature-gradient conditions of material synthesis, a small amount of fusible elements can evaporate. On the contrary, in samples of type 1 during solid-phase synthesis an excess of these elements is observed. Note that these minor changes in individual elements do not generally affect the formation of the Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 phase, and polycrystals of both types, which is confirmed by X-ray phase analysis of the sample (see

Figure 1).

Ionic conductivity of Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals

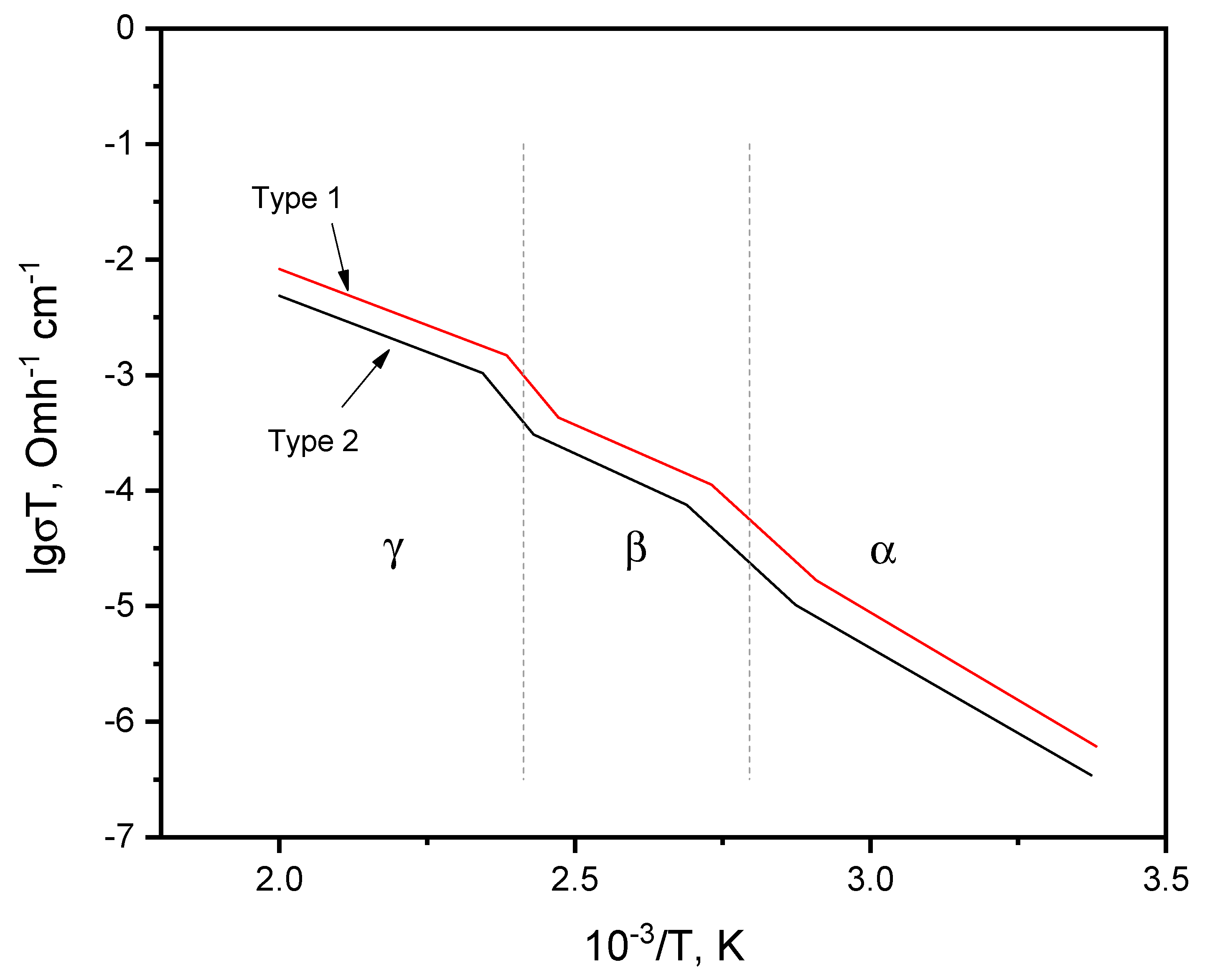

The ionic conductivity of the synthesized polycrystals was determined by the impedance method in the temperature range of 290 – 570 K. Silver paste was used as electrode material. The temperature dependence of the ionic conductivity of Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals of two types is presented in Figure 3. The temperature dependences of the conductivity of Na3Fe2(PO4)3 ionic polycrystals of both types obey the Arrhenius law and are characterized by three linear sections (in log σ(1/T) coordinates), corresponding to the three phases α, β, γ, respectively. These phases are separated by inclined “steps”, because phase transitions of polycrystals are usually blurred in the temperature dependences of conductivity. The reason for this is the isotropic orientation of crystallites in a polycrystal. Nevertheless.

Figure 3.

Temperature dependences of the ionic conductivity of Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals obtained by solid-phase (type 1) and melt (type 2) methods.

Figure 3.

Temperature dependences of the ionic conductivity of Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals obtained by solid-phase (type 1) and melt (type 2) methods.

The temperature corresponding to the middle of the “step” is usually taken as the phase transition temperature (usually, the TC transition temperature established in this way for polycrystals coincides with the phase transition temperature established on single crystals). From Figure 3 it can be seen that the conductivities of type -2 samples are higher than the conductivities of type -1 samples throughout the entire temperature range. To carry out a comparative analysis of the conductive properties of the samples, additional processing of the experimental data was required. The parameters of conductivity and temperature of phase transitions were determined for samples of two types. Calculation data for ionic conductivity and phase transition temperatures are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameters of ionic conductivity and phase transition temperatures for Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals obtained by solid-phase (type 1) and melt (type 2) methods.

Table 3.

Parameters of ionic conductivity and phase transition temperatures for Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals obtained by solid-phase (type 1) and melt (type 2) methods.

| Parameter |

Phases |

Na3Fe2(PO4)3

|

|

1 тип

|

2 тип

|

| Ionic conductivity σ, (Om∙ сm)–1

|

α (295К) |

3.8·10–7

|

4.5·10–7

|

| β (373К) |

5.6·10–5

|

6.7·10–5

|

| γ (573 К) |

8.8·10–3

|

10.5·10–3

|

| Activation energy ΔЕ, eV |

α |

0.63 |

0.62 |

| β |

0.46 |

0.45 |

| γ |

0.39 |

0.39 |

| Temperatures of phase transitions, К) |

α→β |

Тα→β=368 |

Тα→β=368 |

| β→ γ |

Тβ→γ=418 |

Тβ→γ=418 |

From Table 3 it can be seen that for Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals of both types, similar ionic conductivity parameters have been established, however, the ionic conductivity of samples of the first type is lower than that of the second. Although the activation energies and phase transition temperatures of both samples are identical, this is probably due to the similarity of the compositions and structures of the samples. Apparently, the reason for the higher ionic conductivity of the sample of the second type is the presence in it of a higher deformation of the crystal structure, associated with more significant changes in the parameters of the structures with angular displacement β, than in the sample of the 1st type. It is possible that these structural changes may partially reduce the strong monoclinic distortions of the α-Na3Fe2(PO4)3 crystalline framework and lead to an increase in conductivity.

In [

28], a slight increase in conductivity was also observed in a sample synthesized under the influence of hydrostatic pressure. Although in this case the increase in conductivity is associated with all-round compressive deformation of the sample, it also leads to a partial decrease in the monoclinic distortion of the anionic crystal frame, and therefore an increase in the “conductivity window” between the M(1) and M(2) cavities in the conductivity channel.

It should be noted that in the solid solution system Na

3Fe

2(1-x)Sc

2x(PO

4)

3 (0<x<0.06) an increase in conductivity was observed [

36]. The thing is. that the replacement of M-iron cations (r

Fe=0.54) with scandium atoms (r

Sc=0.82) in Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 also leads to local tensile deformations of the crystalline framework, due to the difference in the ionic radii of the replaced elements. These deformations partially reduce the monoclinic distortion of the crystalline framework of the solid solution and partially increase the ionic conductivity it. This type of deformation occurs due to the action of a “chemical press” (local tensile deformation of the crystalline framework). From these results, it follows that the crystalline framework of Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 is very “elastic”, mainly due to the presence of polyhedron units (PO4) in the anionic framework, which is confirmed by spectroscopic data from [

29].

The results obtained can be explained by the fact that the Na

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 polycrystals of the first type were formed under more equilibrium thermodynamic conditions, therefore the anionic crystal frame underwent relatively less deformation during synthesis than when the polycrystal was synthesized under the influence of optical radiation or when synthesized under the influence of hydrostatic pressure. Probably, the reason for the ambiguity of the resulting crystal structures during synthesis is the thermodynamic factor, which influences both the degree of deformation of polycrystal structures (i.e., the mechanical stresses present in the structure) and the degree of “openness” of the “conductivity window” between M(1)- and M(2) - cavities in the conduction channel. [

12,

13].

Of course, the technology for producing polycrystals of the second type, obtained by the melt method under the influence of optical radiation, is of practical interest, because This technology makes it possible to increase the conductivity of samples, which does not exclude an increase in capacitive properties during electrochemical processes in NIB. therefore, it can be used to create cathode materials of other compositions for scientific research. This technology deserves further research because... can be effective and used in the creation of cathode materials of various compositions for scientific research.

Conclusions

Based on the presented experimental results and analysis of the structural conductive properties of Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals obtained using different technological methods, the following conclusions can be drawn:

1) Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals prepared by solid-phase methods have a monoclinic-distorted system (space group at room temperature T = 295 K). It has been established that relatively equilibrium thermodynamic conditions for the synthesis of polycrystals (type 1 samples) contribute to the formation of a monoclinic-distorted crystal structure in them. However, the synthesis of Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals in a regime of sharply gradient temperatures (in nonequilibrium thermodynamic conditions) by the melt method under the influence of optical radiation (type 2 samples) leads to the creation of more noticeable shear and angular deformations in the structure of the crystalline framework, which contribute to the partial removal of monoclinic distortions.

2) It is concluded that the crystalline framework of Na3Fe2(PO4)3 is “elastic”, therefore the structure of the polycrystal is very sensitive to external nonequilibrium thermodynamic, mechanical, and chemical influences. The texture of polycrystals obtained by the solid-phase method of samples (type 1 samples) is less ordered than in samples obtained by the melt method under the influence of optical radiation (type 2 samples).

3) It has been established that samples of both types have similar conductive parameters, but the ionic conductivity of samples of the second type is slightly higher than that of the first. It is concluded that the reason for the higher ionic conductivity of samples of the second type is the presence of more pronounced shear and angular deformations of the crystalline framework, which can partially weaken the strong monoclinic distortions of the α-Na3Fe2(PO4)3 crystal structure and lead to a greater openness of the “conductivity window” in the conduction channel.

4) The technology for producing Na3Fe2(PO4)3 polycrystals by the melt method under the influence of optical radiation can be used to create other compositions of cathode materials to improve the processes of intercalation and deintercalation in NIB.