1. A brief history of the Yamato region and Nara’s ancient capital city

The Nara (奈良) prefecture is an administrative district located in the inland territory of the Kii peninsula was once called the Yamato region (Kansai nowadays), starting from the Yayoi era (2nd B.C – 3rd A.D). From the 5th century, the region was developed into a major center of political power with the form of a confederacy known as Yamato Japan. In the 6th century, a community began to appear an organized political council led by a government was established known as the Yamato Court. Since this period, Chinese civilization and Buddhism were imported into Japan, creating a strong development in technology, and profound changes in political institutions and social structure.

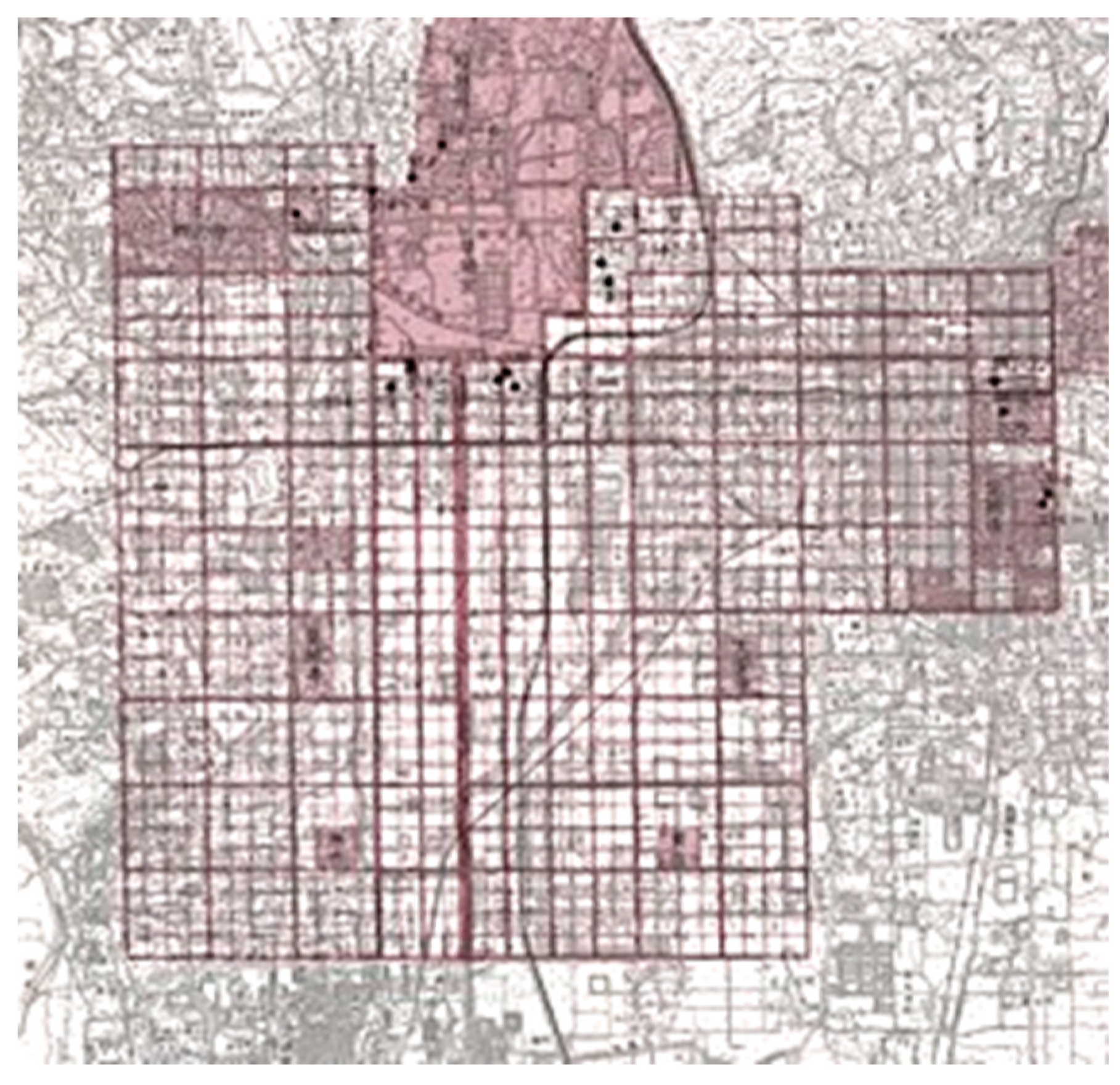

In the 710s, Japan’s first large-scale Heijokyo capital city (平城京, hereinafter referred to as “Nara’s ancient capital city”) (

Figure 1) was built in the copied model of the Chinese Chang’an capital city (長安京, Tang dynasty, 618–906) with distinctive features of the typical Fengshui capital city with the length of the north and south sides is 4.2 km, east and west sides are 4.7 km (Japanese Historial Chart 2003). In the 740s, after the political upheaval of the Fujiwara family, the capital was moved to the Kuni area. In the 744s, due to religious reasons and the suppression of other political powers, the capital was again moved to the Naniwa area. In the 745s, due to the impaction of Fengshui, the capital was moved back to its old location in Nara and remained there until the 784s before it was moved to Nagaoka. In the 794s, the capital was again moved to the Heian area (Kyoto nowadays) (

Figure 2) and remained there until more than a thousand later years (Catalog of Nabunken 2001).

The Nara period (710 - 784) was a short but volatile historical period, which left behind for this land a huge amount of cultural property with a dense density of heritage, most of which have been recognized by UNESCO as the World cultural heritage or classified by the Japanese government as a particularly important national heritage, such as Toudaiji pagoda (東大寺, 760), Houryuji pagoda (法隆寺, 607), Toshodaiji pagoda (唐招提寺, 710), Koufukuji pagoda (興福寺, 685), Yakushiji Pagoda (薬師寺, 718), etc., especially Heijokyu imperial city (平城宮, 710 – 784, hereinafter referred to as “Nara Palace Site”) with outstanding conservation achievements and reconstruction of Japanese architectural heritage.

2. Study purposes and methods

The purpose of this study is to understand the Japanese theory in the conservation of cultural heritage and its connotation. Normally at first feeling, the Japanese method of conservation and reconstruction of architectural heritage characterized by “Always renewable and always authentic” was difficult to accept because of the precedent provisions mentioned in the previous-approached international conventions. However, based on the characteristics of Japanese architectural heritage, which is mainly wooden architectural heritage, restoration work to maintain the existence of the heritages is necessary. Accordingly, the necessity to replace decayed wooden timbers with new ones is force majeure, if this replacement is repeated frequently over time will lose the original value of the heritage. In addition, the reconstruction of the ancient wooden heritage buildings of the Nara Palace Site with the recognition as a World cultural heritage is also an extraordinary new thing that has not been preceded before. In addition, learning and applying the advanced conservation methodology and sharing experiences with the community is the task of the conservation experts, which is also the purpose of conducting this study.

Architectural heritage conservation is a practical science that combines many different fields of study such as history, culture, archaeology, architecture, construction, and fine arts, and therefore needs to be established concurrently with several different approaches. With the pleasure of participating in training courses sponsored by JICA (Japan International Cooperation Association), practicing on the restoration sites in Japan such as the Nara Palace Site (1997, 2004, and 2006), Sakanoke family’s traditional house (2005), Toushodaiji (2006), Takenaka Dougukan museum of carpentry tools (2007) and other cultural heritage sites in Japan during the term of internship, conducting reference of archaeological reports of the Nara Palace Site, studying the international conventions, and lecturing from Japanese master artisans particularly architect-master carpenter Takaka Fumio, Satoh’s traditional lacquer family, and the Nabunken conservation experts. Those approaches provided the author with many useful study sources and information that helped to accumulate knowledge and experience for this study.

3. Introduction of the Nara Palace Site - Discovery and Conservation

3.1. Archaeological excavation works

The Nara Palace Site nowadays is the central part where political power and imperial residence are concentrated, occupying an area of about 1/16 of the total area of Nara’s ancient capital city. In the 1916s, Professor Sekino Tadasu (1867-1935) of the University of Tokyo began to survey the Nara area to find traces of the famous Heijokyu (Nara Palace Site) recorded by Japanese historical documents. Randomly, he heard information from farmers about a land called Daigoku, it reminded him of the name of the main palace of the Heijokyu recorded in historic documents as Daigokuden (大極殿) (Catalog of Nabunken 2001), then in 1918, he conducted a probed excavation and discovered the first basement stone of the Daigokuden (Hirota 1983). In the 1923s, a small-scale archaeological survey conducted by professors and archaeologists determined the exact location of the Nara Palace Site.

Probably at the same time, from the 1912s, Professor Ito Chuta (1867-1954) of the University of Tokyo began to study ancient heritage buildings in Nara with a focus on the Horyuji pagoda and the history of the pre-Nara period. Although his research has not focused directly on the Nara Palace Site, he has made important fundamental contributions to the understanding of architectural heritage and other important knowledge about the ancient periods of Japan (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), greatly contributing to the reconstruction study of the Nara Palace Site later.

Until the 2004s, more than 130 hectares of land were surveyed and nearly 1/3 of that area was archaeologically conducted including the foundations of important heritage buildings. According to the results of topographic measurement and analysis, the Nara Palace Site has north and south sides of 1.250 m, and east and west sides of 1.000 m (Nabunken 1977). Because the Nara Palace Site is located in the basin near the foot of the mountains, the terrain is flat but has a rather steep slope in the northeast-southwest direction, the alluvial soil layer in the south area is up to 3,5m thick, in then in the north area it was thin, the depositional formation only appeared as the lower layer of the present ground level (Nabunken 1979). However, on average in the central area, the ground level of the Nara period is about 80cm lower than the present.

It can be said that the archaeological excavation at the Nara Palace Site has opened the mysterious door of a legendary historical period that has been covered for more than 1,200 years, making an important contribution to the reconstruction of the ancient history of Japan. Accordingly, thousands of archaeological artifacts of various types, tools, thousands of pages of ancient documents, and a hundred of original timbers have been discovered and preserved scientifically, which are very useful for the study of history, architecture, art, technology, and a deep understanding of ancient history, providing important knowledge for the study of conservation and reconstruction of the architectural heritage of Japan.

3.2. Preservation of the Archeological Sites

There were two general solutions that have been proposed and implemented in sequence. First, planning the archaeological site into a relic park according to the site planning model of the ancient capital city while reconstruction projects have not been implemented. Second, represents the historical appearance when sufficient evidence has been collected, the doubts have been clarified, and reconstruction of the selected important heritage buildings.

For archaeological foundation ruins, the modeling method has been applied. The modeling method is understood as the visualization of information and knowledge about the ruins related to each architectural entity or a complex of foundation ruins by hypothetical models. Even large archaeological sites are modeled to preserve the integrity of the knowledge and archeological information for future reference.

For large complexes of heritage buildings, visualization of hypothetical research results by full-scale modeling is very useful for analysis that cannot be done by 2D drawing or 3D computer graphics. These full-scale models are placed right above the foundation ruins at their original location, this solution proved quite effective in assisting in visualizing the overall planning of the Nara Palace Site (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

For the ruins of other objects discovered during the excavation, whether they are objects of the architectural components such as timber, basement-stone (located not at their original position), brick, tile fragments, or archaeological artifacts (

Figure 7) were relocated at the new gathering places for research, storage, and display (Koezuka 1996).

3.3. Reconstruction of the Heritage buildings

Reconstruction studies and reconstruction projects are different. Reconstruction projects must be based on proven reconstruction study results. The reconstruction studies yield a richness of information that is important not only to one but to many other reconstruction projects. In other words, the reconstruction project is the come-later consequence of reconstruction studies. For the field of architectural heritage reconstruction, an understanding of the history of architecture, archaeology, traditional materials, and traditional techniques must be the first of many necessary and sufficient conditions for the reconstruction of the heritage. In case of the heritage, information is fully available and the authenticity of the sources is guaranteed, it is eligible to carry out the reconstruction projects of the lost heritage buildings.

By the method of comparative analysis on the existing-synchronous and similar heritage buildings which date back from the same Nara period as mentioned above, and based on the revealed archaeological foundation, it is possible to determine the column spans and column diameter, the researchers did analyze and compare of architectural proportion between the archaeological foundation with the existing-synchronous and similar heritage buildings, thereby predicting the upper-structure of the lost heritage buildings to be reconstructed. The design unit used to analyze was the traditional measurement unit of Japan known as Saku, 1 unit of Sakura = 29,5 cm (Nabunken 1994).

Reconstruction works have been carefully carried out based on the following main stages: Researching historical documents and related information, archaeological study of remaining foundations, analysis of architectural proportion, studies of the traditional design method and construction techniques, carrying out the architectural and engineering design, 3D computer modeling, building experimental research models (1/20, 1/10, 1/5 scale), material and structural testing, promoting reconstruction work, and publication of scientific reports. The full-scale model also can be considered as the reconstructed heritage building (

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12).

In fact, it is difficult to give an accurate assessment of the authenticity of these reconstructed heritage buildings, but one of the important original constituents that has been identified as the archaeological foundation at its original location, and the full knowledge of traditional construction techniques applied in the time frame of Nara period, the reconstructions were appraised to meet the authenticity according to the international conventions.

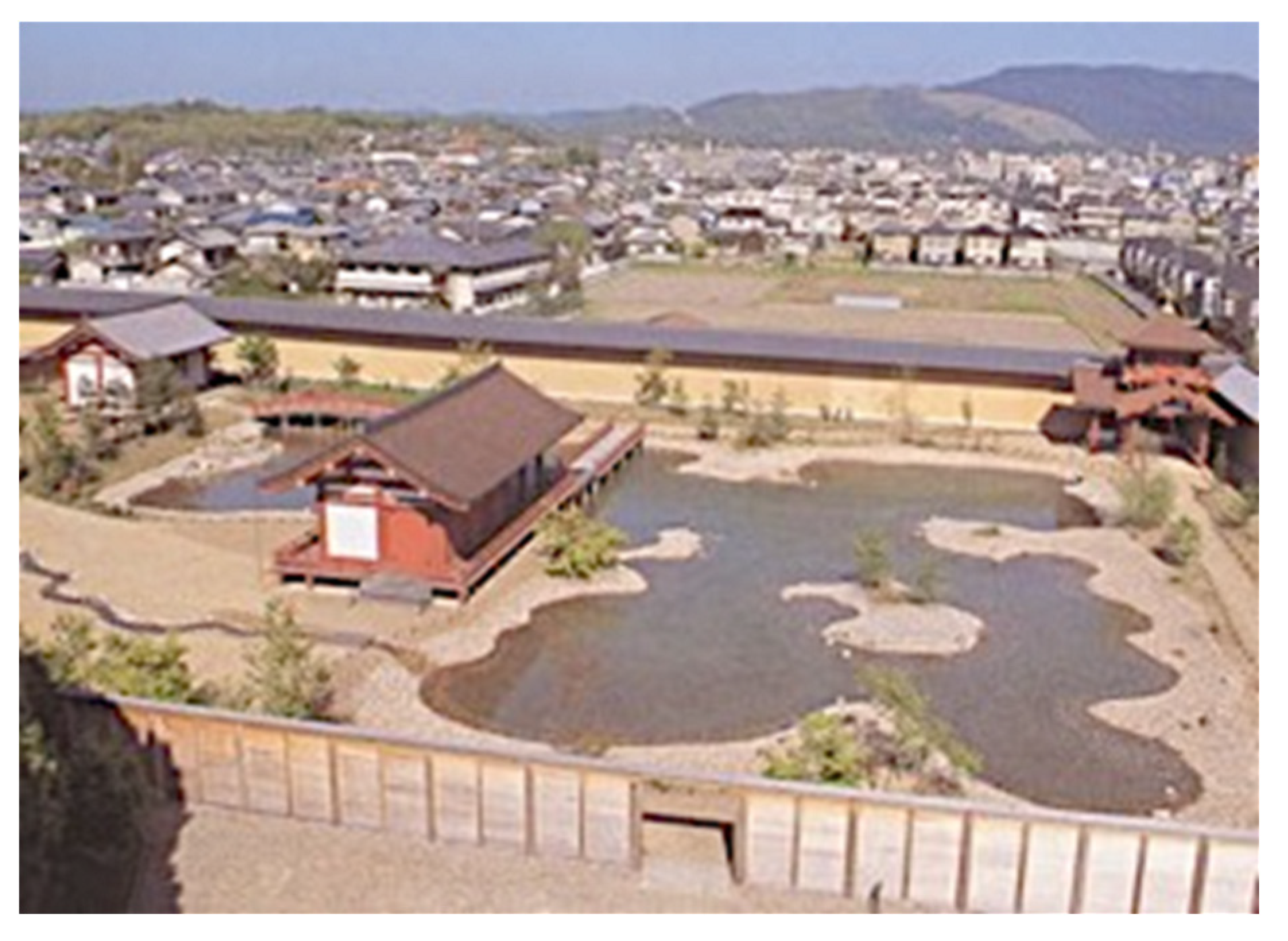

In a word, after nearly 100 years of research and accumulation of knowledge with thousands of scientific study reports, published books, and hundreds of Ph.D. theses, it was not until the last years of the 20th century that the Japanese began the reconstruction work of the Nara Palace Site. Accordingly, important heritage buildings have been reconstructed such as “Suzakumon” Scarlet Phoenix Gate (朱雀門), “Daigokuden” Imperial Audience Hall (大極殿), and “Touinteien” East Palace Garden (東院庭園), which recognized by UNESCO as the World cultural heritages.

4. Comprehensive studies of the Heritage site for the conservation

Normally, comprehensive studies are clearly distinguished from site surveying which is included in restoration projects. The outcome of comprehensive studies is knowledge of the heritage and an objective assessment of heritage values. Therefore, it is an effective way to understand the cultural genetic sources and thereby conserve the authentic values of the heritage.

4.1. Historical source studies

All of the historical sources (including official historic documents, ancient inscriptions, old drawings, and possibly previous study reports) should be thoroughly investigated and cataloged. These works are aimed at determining the existence of heritage buildings, their construction history, modification or/and transformation through previous restoration or renovation activities, symbolic meaning, and the use of heritage buildings (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14).

Through historical source studies, the architectural chronology, and its authentic features will be truthfully re-drawn. On that basis, it will help conservation experts to make objective and accurate assessments of the heritage values, and draw up a suitable plan for restoration or/and reconstruction projects to give back the highest value at its golden age. In addition, the historical studies will help to build comprehensive records of heritage buildings for the future stages of conservation.

4.2. Archaeological studies

Archaeological studies in the restoration and reconstruction of heritage buildings are applied to the constitutive elements of architecture, namely the structures underground and above the ground level. Understood in a large sense, the structure underground can be the whole ruins of the archeological sites, and in a narrow sense, it can only be the underground parts of the foundation of heritage buildings. These are very important physical pieces of evidence proving the existence of the heritage buildings at their original location, and/or information indicating the change of their physical structure through the previous renovations. Once there is a change in the underground structure, it is a sign of strong intervention in the physical structure of the heritage building, thereby affecting the change of the structure above the ground which can be seen (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16).

For the structures above the ground level, tracing the vestiges or pieces of evidence related to the modification and transformation of the heritage buildings is very important to help identify the morphological transformation and change the building structure. That information is useful to the field of architectural history studies, although the choice of restoration solution may ignore these archaeological discoveries.

4.3. Studies on the traditional designing principles and methods

The traditional design method is an original intangible source of the heritage’s constituting value. In the ideal case, the original drawings are still handed down and found, however for wooden architectural heritages, most design methods are often handed down by experiences passed from generation to generation, or by formulas encoded in a particular way by each ethnic community in which traditional families of carpenters and artisans are often the holders of these experiences. In some cases, their wording or working procedures did not match contemporary scientific logic, yet the knowledge they imparted through history was superior, programmed to create the architecture and to generate the heritage.

Therefore, the original drawings, in this case, should be approached and understood in larger concepts, it is not merely geometrical sketches that specify dimensions and pure architectural language characters but can be formulas encoded in various forms. Conservation experts and researchers need to understand the Architectural Heritage DNA and the mechanism that forms the heritage values, thereby providing useful guidance for restoration solutions to conserve as much as possible the authentic value of the heritage (

Figure 17,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19).

4.4. Studies on the traditional construction technique and authentic materials

The application of traditional construction techniques and the use of authentic materials are prerequisites to ensure the authenticity of architectural heritage through restoration activities (

Figure 20,

Figure 21,

Figure 22,

Figure 23,

Figure 24 and

Figure 25). Therefore, before intervening in a heritage building, it is necessary to understand how the heritage building was built, what materials are made of, and how their physicochemical properties can be used for suitable consolidated solutions.

It is very dangerous to apply construction techniques and to use alternative materials other than the original version of the heritage building once these techniques and materials have not been proven in terms of time, leading to degradation or rapid collapse. The more important issue is that the meaning and purpose of the restoration and conservation of architectural heritage will not be achieved if the elements constituting the heritage value are omitted or distorted. The original value and authenticity of the heritage will be gradually lost due to ignorant restoration activities and lack of careful consideration in the application of construction techniques and alternative materials which are specified in the above-mentioned Nara Document.

4.5. Experimental model study

It existed in the past as a way to visualize the intention of architectural design using a model (made of fired clay, wood, or metal) to express the features and structure of the intentional buildings. However, this method is gradually being forgotten due to the overwhelming use of computer technology today with 3D images that are very convenient for observing the three-dimensional space of architecture. The design method by model helps to directly verify the feasibility of load-bearing structures and construction methods. This method is especially important for wooden heritage buildings because the timbers are worked together by traditional tenon methods, they work together continuously to transmit force and suppress forces to help the heritage building achieve structural stability and aesthetic balance. In case the design is not optimized, these experimental models can be disassembled for further research to overcome the weaknesses of the design (

Figure 26 and

Figure 27).

Usually, the appropriate model scale will be 1/200 or 1/100 for the study of site planning principle or a group of heritage buildings, 1/20 or 1/10 for architectural study, 1/5 for the structural study, and 1/1 for the study of decorative patterns carved on wood or painted murals. Thus, the experimental model study in the restoration of architectural heritage is like a draft problem to avoid technical errors that may be encountered during the restoration process.

4.6. Studies on the modification or/and transformation of the heritage building

Architectural heritage is created by humans to satisfy the essential living needs of biological life, grace sense, filial piety, and spiritual needs, so the sustainable existence of the heritage is almost determined by these factors. In the process of human existence on the planet, in the broad sense is the collision of civilizations, and in the narrow sense, cultural interaction and changing of needs always occur that make the modification or/and transformation of heritage buildings. So, studying this phenomenon can bring a deep understanding of the heritage-bearing capacity through history. This, perhaps, can give a suitable orientation for the restoration and reconstruction projects to give back the authentic values of the heritage buildings.

4.7. Heritage historical environment and remained sporophyll-pollen studies

Architectural heritage is always placed in the natural environment organically associated with its value. In terms of physical impact, humidity, wind, and heat, will directly affect the material expansion of the heritage buildings. In terms of chemical effects, active substances in the air, and plant pollen spores will have chemical interactions with architectural materials with both positive and negative impacts. Therefore, a full understanding of the heritage surrounding the natural environment and sources of wooden materials is necessary to generate effective solutions to improve the technical conditions of the heritage building, limit the negative impacts, and increase the positive impacts on the existence of that heritage building.

In addition, the surrounding natural environment also plays an important role in regenerating architectural landscaping around the heritage building that is related to the heritage’s constituting values. The color of flowers and leaves, the height and cover of the tree canopy, and the shaded area are also important factors that directly affect heritage landscaping (

Figure 28 and

Figure 29).

4.8. Publishing the restoration and reconstruction reports

Publishing reports after the restoration project completion are not merely as-built records for the payment and settlement of volumes. The restoration and/or project of the heritage buildings are completely different from a new architectural construction project, but most of the processes and conditions for making payment and settlement of the volume are subject to the construction work that leads to a way of trivializing the restoration and reconstruction of the heritage buildings. Restoration and reconstruction document storing, database digitalizing, and publishing reports can bring long-term benefits to the conservation of architectural heritage, because:

Firstly, it is a summary of the theoric and practical experience;

Secondary, it is a valuable legacy scientific record with a lasting reference value;

Thirdly, it is the legal base for the payment, settlement, and disbursement of investment fund for restoration and preservation of heritage (

Figure 30).

5. International conventions and the Japanese conservation theory

5.1. Regarding the 1964 Venice Charter

The unifying characteristic of the wooden architectural heritage of Asian countries is structured from a variety of timbers by specific tenon jointing techniques. In addition to forced changes due to human repair and renovation activities, wooden structures also have their own changes due to external factors affecting and unavoidable laws of material decomposition. Therefore, the requirement to repair and replace decayed wooden timbers is a force majeure activity to maintain the existence of heritage buildings. Accordingly, if the architectural heritage is recognized as a living entity, all of the above changes or replacements are considered elements constituting the values of the heritage.

Article 11 (Venice 1964) concerning that “The valid contributions of all periods to the building of a monument must be respected since the unity of style is not the aim of a restoration”. Article 9 (Venice 1964) concerning that “The process of restoration is a highly specialized operation. Its aim is to preserve and reveal the aesthetic and historic value of the monument and is based on respect for original material and authentic documents”. Accordingly, it is particularly important to preserve the original material and to keep the authentic documents demonstrating the heritage value, then therefore the restoration work must aim to achieve integrity in the preservation of all values including the changes of the heritage in the past.

However, the above-mentioned contents in the Venice Charter seem inadequate and difficult to apply thoroughly to wooden structures that are often sensitive to weather conditions and often have shorter lifespans than brick and stone structures. Therefore, in order for the contents of the Venice Charter to be applicable to wooden heritage buildings, of which Japan is one of the countries possessing many types of these heritage buildings, it must be based on the specific characteristics of the heritage for a specific interpretation or concept complement. Specifically, the “Change” that has been made to brick and stone structures (throughout the history of their existence) is basically understood as the addition of a new part or a new layer of plaster, while for traditional Japanese wooden heritage buildings, it is the “Replacement” of decayed timbers with a new one at its primary position and with its original function, or replace a part of timber in case of the consolidation need (

Figure 31). It is this confusion that has led Japanese conservation experts to strive to build a new conceptual connotation based on the term authenticity as stated in the Venice Charter. On the one hand, to improve the contents of the Venice Charter, on the other hand, to expand the conceptual connotation to suit the conditions and nature of each type of heritage, specifically Japanese wooden heritage buildings.

Obviously, “Originality” includes “Authenticity”, but “Authenticity” does not necessarily imply the value of “Originality”. For example, if the column is identified as original, column A can be considered as the original component with full evidence, that is, that column also has authenticity. Whenever that column is decayed, the material goes through an irresistible period of decomposition, which itself cannot continue to perform the same bearing function as before, forcing people to replace a new column. If the new column, called column B, is made in the same way that the original column A was made (the same wood species and physicochemical properties, the same design thought and method, the same carpenter tool, technique, the same function, form, and decorations), then column B achieves the same authentic value as column A (but it is not an original component). However, when the same procedure is repeated for column C to replace column B, column B also becomes containing the original value (but it is not the primary component). With the characteristics of natural wood materials (if chemical preservation methods have not been applied) and with the above logic, column A can be decomposed and disappear. And, if the replacement of column B into the position of column A, or column C into the position of column B is force majeure, then all 3 columns A, B, and C will at some time point in the future be equivalent values.

The “Authentic” concept in article 11 (Venice 1964) as the above-mentioned can be understood in a way that is too broad or conversely too narrow within the limits of literature. Therefore, in article 9 (Nara 1994), this concept has been emphasized and concretized “Conservation of cultural heritage in all its forms and historical periods is rooted in the values attributed to the heritage. Our ability to understand these values depends, in part, on the degree to which information sources about these values may be understood as credible or truthful. Knowledge and understanding of these sources of information, in relation to original and subsequent characteristics of the cultural heritage, and their meaning, is a requisite basis for assessing all aspects of authenticity”.

However, with the valuable attribute of heritage as a living entity, the above concept is not comprehensive enough. Therefore, in article 13 (Nara 1994), that concept has been further expanded “Depending on the nature of the cultural heritage, its cultural context, and its evolution through time, authenticity judgments may be linked to the worth of a great variety of sources of information. Aspects of the sources may include form and design, materials and substance, use and function, traditions and techniques, location and setting, spirit and feeling, and other internal and external factors”. Thus, the 1994 Nara Document on Authenticity (hereinafter referred to as “Nara Document”) is not only applicable to Japanese architectural heritage but also can be effectively applied to various types, especially to wooden architectural heritage.

With such basic arguments, Japanese conservation experts have developed an applicable conservation theory for the type of wooden heritage building. Thus, besides preserving the original elements, it is also very important to preserve traditional design methods and technologies so that they can maintain their authenticity and further re-create authentic value. That is the Japanese conservation theory applied to the conservation of architectural heritage characterized by the “Always renewable and always authentic”.

5.2. Regarding the 1994 Nara Document on Authenticity

The Nara Document consists of 13 articles and two appendices, in which the addition of the concept of Cultural diversity and Heritage diversity, the Values and Authenticity are conceived in the spirit of the 1964 Venice Charter. Accordingly, it is bright to see that the Nara Document has simultaneously implemented two important theoretical items that expand the core concepts in the conservation of cultural heritage worldwide.

5.2.1. Cultural diversity and Heritage diversity

Dialectically, heritage diversity is an inevitable consequence of cultural diversity, consistent with UNESCO’s basic principle that the cultural heritage of each community is the cultural heritage of all human communities (Nara 1994, article 8). Therefore, the diversity of cultures and heritage in our world is an irreplaceable source of spiritual and intellectual richness for all humankind, and the protection and enhancement of cultural and heritage diversity should be actively promoted as an essential aspect of human development (Nara 1994, article 5).

Accordingly, the development of human society in general and each ethnic community, in particular, cannot but rely on each nation’s historical and traditional inheritance. The diversity of heritage will enrich and ensure a source of fresh cultural genes from which each ethnic community can develop sustainably. The concept of cultural diversity and heritage diversity mentioned in the Nara Document has broadened the heritage identification framework, from which a variety of traditional architecture and indigenous buildings generated by initiative acculturation with others through history can be a candidate for the national cultural heritage or the World cultural heritage.

5.2.2. Values and Authenticity

Heritage includes the following groups of values (Feilden, ISBN 0-7506-5863-0).

- a)

Emotional values include values of wonder, identity, continuity of tradition, admiration, reverence, symbolism, and spirit.

- b)

Cultural values include documentary, historical, archaeological, and chronological values, aesthetics and architecture, landscape, ecology, science, and technology.

- c)

Future usage values include functional, economic, social, educational, and political values.

Those groups of values are appraised, or recognized after the heritage has been generated, or recognized, these are also the evaluation criteria for the recognition of ranks and types of cultural heritage.

The Nara Document clarifies the origin of these values through the concept of heritage’s constitutive values including their whole aspects to create those values of the heritage are clearly expressed that the cultural heritage diversity exists in time and space, demands respect for other cultures, and all aspects of their belief systems (Nara 1994, article 6). In addition, the conservation of cultural heritage in all its forms and historical periods is rooted in the values attributed to the heritage (Nara 1994, article 9). Thus, it can be considered that before the heritage and its values have been generated, there existed the germ of the latent heritage shape within the tradition of the ethnic community that produced it. Perhaps, this is a bold and completely valid conceptual proposition derived from the tradition and reality of the conservation of Japanese cultural heritage, its scope is not limited to the framework of the administrative boundaries of Japan but also can transcend space and time to spread to many other countries.

The concept of authentic documentation was mentioned for the first time in the 1964 Venice Charter, but it is limited in the framework of documents proving the original and trustable information of the heritage for restoration activities which aims to preserve and reveal the aesthetic and historic value of the monument based on respect for original material and authentic documents (Venice 1964, article 9). However, the authenticity mentioned in the Nara Document has concerns that depending on the nature of the cultural heritage, its cultural context, and its evolution through time, authenticity judgments may be linked to the worth of a great variety of sources of information. The aspects of sources may include form and design, materials and substance, use and function, traditions and techniques, location and setting, spirit and feeling, and other internal and external factors (Nara 1994, article 13).

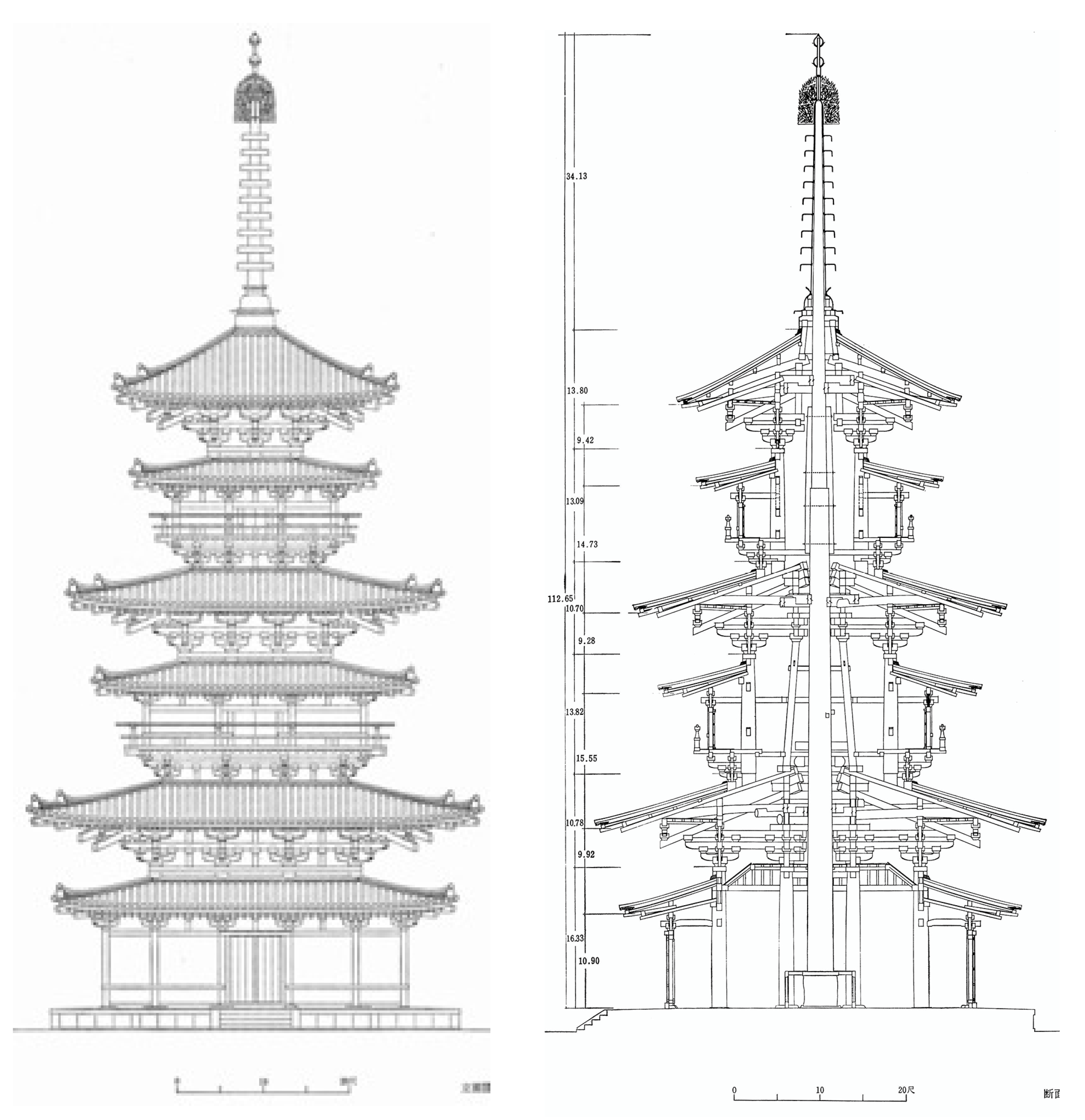

Besides, a monument in the shape of a building is an architectural entity consisting of a combination of original objects that cannot be reproduced, heritage in the shape of a wooden building is a wooden heritage building that can able to be physically reconstructed by continuing to not hybridize its source of genetics in case of its destruction. Thus, the monument is a unique prototype while the wooden heritage building can be an “N” version of that original prototype able to be regenerated during its use throughout history. For the case of the re-located Yakushiji pagoda (718) in Nara, the reconstruction of the West pagoda (in 1980) based on its source of genetics referenced from the design of the East pagoda (the three-stories pagoda is original one dates back to the 8th century), perhaps, is a typical example of this connotation (

Figure 32,

Figure 33 and

Figure 34). In addition, the Japanese reconstruction methodology has been applied suitably in the case of the Can Chanh Dien main palace of Hue Imperial City – World cultural heritage in Vietnam (An, Chau 2019).

In a word, what Japanese wants to present through theory and practice on the conservation of architectural heritage is like the born-cloning of the “Dolly sheep” in biology to open up the international legal base for the restoration and reconstruction of valuable architectural heritages lost in the past typical case being the Nara Palace Site.

Regarding, the authenticity considered according to the Nara Document appears as the essential qualifying factor concerning values, the understanding of authenticity plays a fundamental role in all scientific studies of cultural heritage, conservation, and restoration plans (Nara 1994, article 10). Therefore, the connotation of authenticity is very broad (in terms of quantity) and becomes important (in terms of quality), opening up great prospects for the reconstruction of the wooden architectural heritages of many other countries. From this, it is possible to think about the concept of the so-called “Architectural Heritage DNA”.

6. Discussion on the so-called “Architectural Heritage DNA”

6.1. Regarding Biology, Genetics, and DNA

Biology is the scientific study of life, it is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary information encoded in genes, which can be transmitted to future generations. Another major theme is evolution, which explains the unity and diversity of life (Hillis, Heller, Hacker, Sally D, Laskowski, Marta, Sadava, David, 2020).

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms. It is an important branch of biology because heredity is vital to organisms’ evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar working in the 19th century in Brno, was the first to study genetics scientifically. Mendel studied trait inheritance, patterns in the way traits are handed down from parents to offspring over time. He observed that organisms (pea plants) inherit traits by way of discrete units of inheritance. This term, still used today, is a somewhat ambiguous definition of what is referred to as a Gene (Griffiths, Miller, Suzuki, Lewontin, Gelbart, 2000)

DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth, and reproduction of all known organisms and many viruses (Alberts, Johnson, Lewis, Raff, Roberts, Walter, 2014). The foregoing are areas of in-depth expertise related to the unconscious transmission of all life that requires the collaboration of experts to support the following proposals for the structure of the so-called “Architectural Heritage DNA”. In this study, we borrow the basic concepts to express the conscious transmission of traditional culture through the field of architectural heritage study.

Naturally, transmission is the instinct of all life, in which an unconscious transmission guarantees evolution and conscious transmission ensures development. Conservation of architectural heritage is a way of conscious transmission that needs to be conducted based on the effort-establishing structure of the so-called Architectural Heritage DNA.

6.2. Potential Structure of the Architectural Heritage DNA

Following the above-mentioned biological DNA characterized by the “Two polynucleotide chains” and the “Four nitrogen-containing nucleobases”, possibly a somewhat lame application of the concept of cultural DNA, however, as the first grade, we try to propose the potential structure of the Architectural Heritage DNA based on the characteristics of the architectural heritage resources that can be explained as follows.

- ❖

Resource A implied the tangible chains, including:

- (1)

Documentary evidence of the heritage building includes historical documents, remaining historical reference sources, and archaeological evidence.

- (2)

Authentic building materials, architectural features, structure, and maintainability.

- ❖

Resource B implied the intangible chains, including:

- (3)

Traditional design principles, design methods, and a thorough understanding of traditional construction techniques.

- (4)

Integrity and continuity of traditional techniques engaged to the traditional craftmanship, and their applicability to the reconstruction of the heritage buildings.

These two resources A and B like the “Two polynucleotide chains” of the biological DNA representing the two tangible and intangible aspects (negative and positive, or/and yin and yang) of the heritage resources that are intertwined, opposite but not mutually exclusive, and mutually supportive.

In a shortsighted, resources (1), (2), (3), and (4) can be thought of as “Four nitrogen-containing nucleobases” that can be combined in forward, reverse, and diagonal directions together in pairs, thereby making it possible to create the self internal-regeneration of Architectural Heritage DNA in the context of it being socialized. Resources (1) and (2) are tangible elements, so they are often understandable and authenticated within the scope of the conservation major. Resources (3) and (4) are intangible elements often non-understandable, and difficult to validate scientifically because it is often influenced by tradition, society, culture, history, and economy. The ideal case A/B or B/A = 1, is that both tangible and intangible aspects of heritage resources are balanced so that the conservation of architectural heritage reaches the maximum authentic value (100%). The case of A/B or B/A < 1, is that the authentic value is not guaranteed, and needs to be re-evaluated.

Cultural heritage is a sustainable source of genes that strengthens and regenerates cultural identity. In terms of the conservation of architectural heritage, the Architectural Heritage DNA will help the restoration, and reconstruction activities to reach the goal of authenticity and/or high-quality conservation. Economically, conservation achievement will attract affection and restore community admiration and reverence for humanity’s cultural achievements through heritage, from which the tourism economy will flourish. To successfully conserve the cultural genetics of each ethnic community, it is necessary that the Architectural Heritage DNA needs to be regenerated for further future development of each country.

6.3. Regarding Conservation, Restoration, and Reconstruction

In the discussion about the conservation, restoration, and reconstruction of heritage, it is impossible not to mention the 1999 Bura Charter. This Charter provides specific guidance for conserving and managing cultural heritage sites based on the basic contents of the 1964 Venice Charter. The conceptual categories mentioned throughout this paper include conservation, restoration, and reconstruction whose target audience is architectural heritage.

Accordingly, “Restoration and reconstruction should reveal culturally significant aspects of the place” (Bura 1999, article 18), and “Restoration is appropriate only if there is sufficient evidence of an earlier state of the fabric” (Bura 1999, article 19). Meanwhile “Reconstruction is appropriate only where a place is incomplete through damage or alteration, and only where there is sufficient evidence to reproduce an earlier state of the fabric. In rare cases, reconstruction may also be appropriate as part of a use or practice that retains the cultural significance of the place” (Bura 1999, article 20.1), and “Reconstruction should be identifiable on close inspection or through additional interpretation” (Bura 1999, article 20.2). Thus, the heritage buildings can be rebuilt by new construction that was lost, following the exact form, materials, and details as the original (Burden, ISBN 0-07-142838-0).

With the above-mentioned theoretical points, the practice and theory of Japanese in the conservation of architectural heritage, we try to give the interpretation of the concepts as follows:

- ❖

Conservation is a way of accumulating heritage to enrich each ethnic community and the World’s cultural heritage.

- ❖

Restoration is a way to increase bearing capacity, recognize heritage values, and give back that heritage’s authentic value.

- ❖

Reconstruction is a way of reading and understanding heritage to regenerate its source of DNA for the sustainable conservation of that heritage.

Thus, conservation is the mother concept of restoration and reconstruction. Conservation of architectural heritage is not only about keeping the physical heritage buildings but also preserving all that is related to their existence. If the architectural monument is a tangible property, which is unique and non-renewable, then the architectural heritage is a type of cultural property that includes both tangible and intangible elements, applicable to be regenerated. Tangible elements are understood as their existence, including their design drawings, intangible elements include the design idea and truthfully-full understanding of them based on the authentic documentation.

6.4. Regarding Conservation, Inheritance, and Development

In terms of semantic content, heritage is the property to leave for the next generation, and inheritance is the continuation of that heritage. In the context of this discussion, the continuity of tradition and the integrity of the heritage’s constituting value always play a decisive role in the appraisal of heritage values.

Effectiveness is simply a calculated subtraction, what is subtracted but left behind with usefulness and validity is what we need to conserve, inherit, and use as the foundation for sustainable development. Therefore, conservation, inheritance, and development should be grouped into an indispensable unified logic. Non-selective conservation will be messy, development without inheritance is a development that lacks roots and is unsustainable. Thus, inheritance is an essential bridge between conservation and development. How to inheritance effectively the elite results from the conservation of cultural heritage is still a difficult issue that each community has to think about and create a suitable way by themselves, or perhaps, there will be a smart guideline for doing this provided by international experts.

7. As a conclusion

Why is it important to conserve cultural heritage? Because cultural heritage is the driving force to promote and ensure the sustainable development of each ethnic community and the human community because it is humans who have created a culture in their biological environment. Cultural heritage includes both tangible and intangible elements that are closely and sustainably linked together as images with shadows of things and phenomena. Therefore, conserving architectural heritages is keeping their physical existence and conserving all the information related to them.

Complementing and clarifying the concept of Cultural diversity and Heritage diversity, the connotation of Values and Authenticity developed in the Nara Document to help broaden awareness and vision of cultural heritage. Since then, many types of traditional architecture in the World will be the potential candidates to be recognized as the cultural heritage of each community and/or the World’s cultural heritage.

The attrition and loss of traditional values formed through history are inevitable phenomena due to the strict rules of history’s elimination. However, that rule of elimination needs to be oriented and corrected by human intelligence to retain the quintessence people have created through productive labor, progressive perception, and spiritual evolution. The conservation and regeneration of the Architectural Heritage DNA are paramount to the long-term and sustainable preservation of fossil values, which are important sources of knowledge to help mankind not forget the origin and history of their nation. The visible physical structure of the architectural heritage can be lost, but the invisible spiritual structure is still preserved through the conscious transmission that people can actively make and implement this plan.

If civilization is the creations or inventions of mankind to improve their living conditions, then literature is the experience of using civilization through history, and culture is the way of civilized use of each ethnic community. Ancient civilizations were once the driving force for the development of nations around the World, but that “core civilization” can no longer be found in the very place where it originated because of the constant threat of natural disasters, war, and the neglect of human memory. This is a prediction of the phenomenon of “empty civilization” in the millennium time frame. Fortunately, the introduction of the “1994 Nara Document on Authenticity” can help us preserve our culture through the conservation of architectural heritage that still exists, being conserved because of common interests of mankind, and will be a civilized bridge for the next stages of history.

References

- Alberts, B.; Johnson, A.; Lewis, J.; Raff, M.; Roberts, K.; Walter, P. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 6th ed.; Garland. p. Chapter 4: DNA, Chromosomes and Genomes; 2014; ISBN 978-0-8153-4432-2. [Google Scholar]

- An, L. V.; Chau, T. N. Q., “Practicing on the re-construction study of ‘Can Chanh Dien’ Palace, Hue Imperial City, Vietnam-word cultural heritage”, International Journal of Architectural Heritage, Taylor & Francis, 2019. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Burden, E. Illustrated Dictionary of Architectural Preservation; Mc.Graw-Hill; p. 134. ISBN 0-07-142838-0.

- Bura, Australia. 1999. The Bura Charter was adopted by the Australian National Committee of ICOMOS in August 1979, as amended in February 1981, April 1988, and November 1999.

- Catalog of Nabunken, above; Daigokuden Imperial Audience Hall (大極殿), the main hall of the Nara Imperial Palace (710-784), is the place where hole the Court meetings and important national ceremonies take place, the same function as the Thai Hoa Dien main palace in Beijing Fobbident City, China and in Hue Imperial City, Vietnam.

- Feilden, M. B. Conservation of Historic Buildings; Architectural Press; p. viii. ISBN 0-7506-5863-0.

- Griffiths AJ, Miller JH, Suzuki DT, Lewontin RC, Gelbart, “Genetics and the Organism: Introduction”, An Introduction to Genetic Analysis (7th ed.), New York: W.H. Freeman, 2000, ISBN 978-0-7167-3520-5.

- Hillis, David M.; Heller, H. Craig.; Hacker, Sally D.; Laskowski, Marta J.; Sadava, David E. “Studying life”. In Life: The Science of Biology, 12th ed; W. H. Freeman; 2020; ISBN 978-1319017644.

- Hirota, O. Kenchikushi no Sendatsutachi; Shou Kokusha: Tokyo, 1983; pp. 1-38, 89-112. [Google Scholar]

- Japanese Historial Chart, 2003, ISBN-8040-5304-2, p. 28.

- Japanese Historial Chart, above, p. 29; Catalog of the Nara National Cultural Properties Research Institute of Japan (Catalog of Nabunken), 2001, p. 3, http://www.nabunken.go.jp/ayumi/ayumiE.htm.

- Koezuka, T. , Sawada, M., “Conservation of Archaeological Objects – Current environment of Conservation Science in Japan”, Sixth Seminar on the Conservation of Asian Cultural Heritage, Nara 1996, pp. 38-44.

- NaBunKen, Study Report No. 34, Nara Heijo Imperial Palace Site Excavation Report IX (English summary), Nara 1977, p. 127.

- NaBunKen, Study Report No. 36, Nara Heijo Imperial Palace Site Conservation Report I (English summary), Nara 1979, p. English summary.

- NaBunKen, Study Report No. 53, “Architectural studies on the Reconstruction of Suzakumon (Scarlet Phoenix Gate), Nara Imperial Palace” (English summary), Nara 1994, p. 147.

- Nara, Japan. 1994. During the Nara Workshop on Authenticity (the framework of the International Heritage Convention) held in Nara City, Japan in November 1994, UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee, CCROM organization, and ICOMOS officially approved the “Nara Document on Authenticity”.

- Venice, Italy. 1964. Venice Charter 1964, Adopted by ICOMOS in 1965, is the framework text and is an important international convention for the conservation and restoration of cultural heritage around the World.

Figure 1.

An image of the scale of Nara’s ancient capital city (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 1.

An image of the scale of Nara’s ancient capital city (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 2.

The movement of Nara’s ancient capital city in the Yamato region (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 2.

The movement of Nara’s ancient capital city in the Yamato region (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

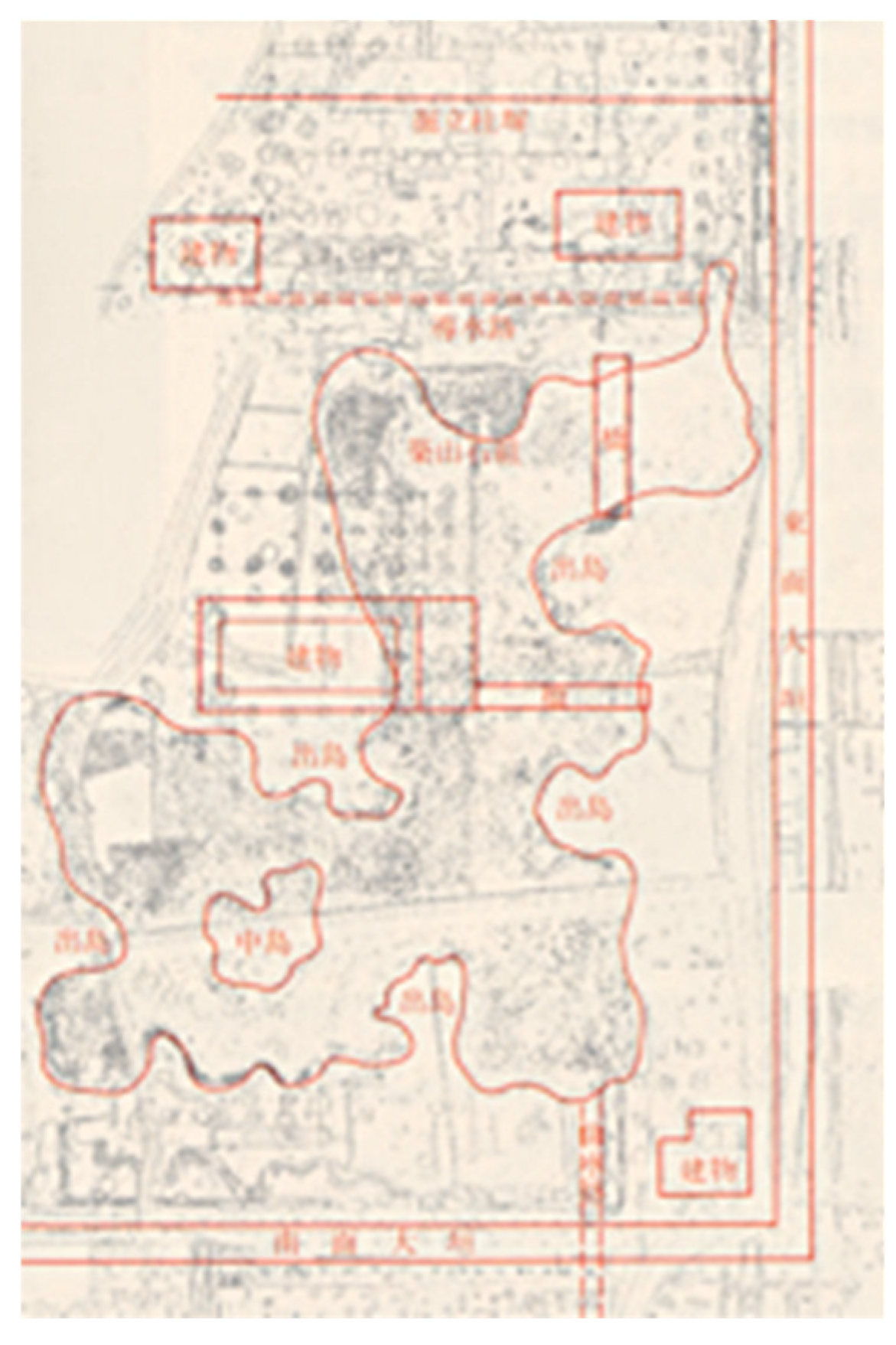

Figure 3.

Archaeological excavation site of the Touinteien (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 3.

Archaeological excavation site of the Touinteien (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 4.

Archaeological drawing of the Touinteien (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 4.

Archaeological drawing of the Touinteien (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

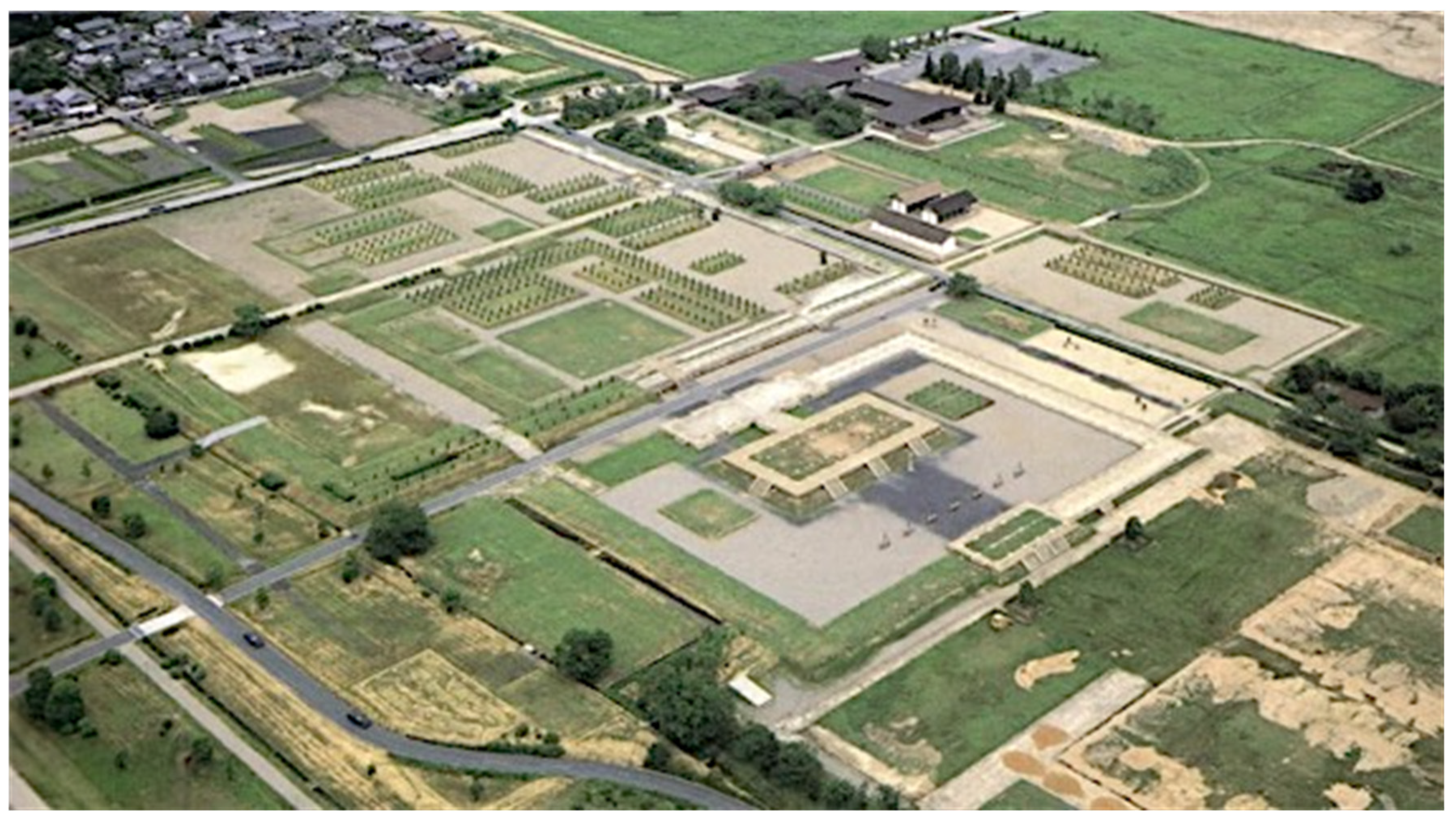

Figure 5.

The 1/1 scale reconstructed model of the central area of the Nara Palace Site (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 5.

The 1/1 scale reconstructed model of the central area of the Nara Palace Site (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 6.

The 1/50 scale reconstructed model of the Imperial residence of the Nara Palace Site (Nara, 2022).

Figure 6.

The 1/50 scale reconstructed model of the Imperial residence of the Nara Palace Site (Nara, 2022).

Figure 7.

The archaeological artifacts have been relocated to the Nara Palace Site Museum (Nara 2022).

Figure 7.

The archaeological artifacts have been relocated to the Nara Palace Site Museum (Nara 2022).

Figure 8.

The 1996 reconstructed Suzakumon Scarlet Phoenix Gate of the Nara Palace Site (Nara 2022).

Figure 8.

The 1996 reconstructed Suzakumon Scarlet Phoenix Gate of the Nara Palace Site (Nara 2022).

Figure 9.

Ruin of the Suzakumon’s foundation (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 9.

Ruin of the Suzakumon’s foundation (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 10.

Reconstruction wooden structure of Suzakumon (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 10.

Reconstruction wooden structure of Suzakumon (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 11.

Reconstructed model of the Daigokuden (1/10 scale).

Figure 11.

Reconstructed model of the Daigokuden (1/10 scale).

Figure 12.

Reconstruction of the Touinteiin (Full-scale model).

Figure 12.

Reconstruction of the Touinteiin (Full-scale model).

Figure 13.

Decoding of historic documents (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 13.

Decoding of historic documents (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 14.

Analyzing the relics and documental historical sources using advanced equipment (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 14.

Analyzing the relics and documental historical sources using advanced equipment (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 15.

Ruins of the wooden structure of a corridor exploded on the archaeological site (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 15.

Ruins of the wooden structure of a corridor exploded on the archaeological site (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 16.

Ruins of the wooden columns (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 16.

Ruins of the wooden columns (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 17.

The “Kiwari shou” old manuals of the Japanese traditional carpenters (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 17.

The “Kiwari shou” old manuals of the Japanese traditional carpenters (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 18.

Decoding of traditional design methods by researcher and carpenter based on the old manuals.

Figure 18.

Decoding of traditional design methods by researcher and carpenter based on the old manuals.

Figure 19.

Re-prototyping of the timbers according to the old manuals and their source of genetics.

Figure 19.

Re-prototyping of the timbers according to the old manuals and their source of genetics.

Figure 20.

The old painting of Japanese traditional carpentry (Source: Takanaka Dougukan Museum of carpentry tools, Japan).

Figure 20.

The old painting of Japanese traditional carpentry (Source: Takanaka Dougukan Museum of carpentry tools, Japan).

Figure 21.

The Japanese traditional carpentry tools (Source: Takanaka Dougukan Museum of carpentry tools, Japan).

Figure 21.

The Japanese traditional carpentry tools (Source: Takanaka Dougukan Museum of carpentry tools, Japan).

Figure 22.

Testing and studying authentic wooden relics of the Nara Palace Site (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 22.

Testing and studying authentic wooden relics of the Nara Palace Site (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 23.

Using authentic material (Hinoki wood) and traditional carpentry tools to represent the historical aspect of replacement timbers (Nara 2006).

Figure 23.

Using authentic material (Hinoki wood) and traditional carpentry tools to represent the historical aspect of replacement timbers (Nara 2006).

Figure 24.

The replacement timbers are assembled as their work position by using traditional techniques (Nara 2006).

Figure 24.

The replacement timbers are assembled as their work position by using traditional techniques (Nara 2006).

Figure 25.

Using authentic material of roof tiles for re-roofing of heritage buildings (Nara 2006).

Figure 25.

Using authentic material of roof tiles for re-roofing of heritage buildings (Nara 2006).

Figure 26.

The remaining original 1/5 scale design model of Kairyuouji Pagoda, Japan.

Figure 26.

The remaining original 1/5 scale design model of Kairyuouji Pagoda, Japan.

Figure 27.

The experimental 1/5 scale-reconstruction model of the Daigokuden Imperial Audience Hall of the Nara Palace Site (Nara 2022).

Figure 27.

The experimental 1/5 scale-reconstruction model of the Daigokuden Imperial Audience Hall of the Nara Palace Site (Nara 2022).

Figure 28.

Historical environment displayed on the old painting of the Nara Palace Site (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 28.

Historical environment displayed on the old painting of the Nara Palace Site (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 29.

Remained sporophyll-pollen studies (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 29.

Remained sporophyll-pollen studies (Source: Catalog of Nabunken, 2004).

Figure 30.

Printed version and tape of video recording of the reports after restoration.

Figure 30.

Printed version and tape of video recording of the reports after restoration.

Figure 31.

Replacement of decayed timbers with a new one at its primary position and with its original function, conserving the original components by traditional jointing techniques and saving the historical information written by ink (Narra 2004).

Figure 31.

Replacement of decayed timbers with a new one at its primary position and with its original function, conserving the original components by traditional jointing techniques and saving the historical information written by ink (Narra 2004).

Figure 32.

Elevation and Section drawings of the East Pagoda of Yakushiji Pagoda (Source: The Lab of History of Architecture, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan).

Figure 32.

Elevation and Section drawings of the East Pagoda of Yakushiji Pagoda (Source: The Lab of History of Architecture, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan).

Figure 33.

The East Pagoda. (Source: https://yakushiji.or.jp).

Figure 33.

The East Pagoda. (Source: https://yakushiji.or.jp).

Figure 34.

The West Pagoda. (Source: https://yakushiji.or.jp).

Figure 34.

The West Pagoda. (Source: https://yakushiji.or.jp).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).