1. Introduction

Cochlear implantation is an established therapy for sensorineural hearing loss if hearing aids and other solutions fail to restore speech recognition [

1,

2]. Recent studies reported on successful CI provision for patients with hearing losses from 50 to 80 dB [

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, even in these patients, with good preconditions for postoperative word recognition – and even more in the established patient population with no preoperative word recognition [

6] – some challenges still remain. Recent studies and opinions [

3,

7,

8,

9,

10] indicate a lack of audiological differential diagnosis in these patients and highlight the observation that “the broad array of factors that contribute to speech recognition performance in adult CI users suggests the potential both for novel diagnostic assessment batteries to explain poor performance, and also new rehabilitation strategies for patients who exhibit poor outcomes” [

7].

To our knowledge there is no generally agreed classification of CI recipients with respect to performance or to speech perception in general. A prediction model recently introduced by Hoppe

et al. [

3] for the expected postoperative word recognition score at conversation level, WRS

65(CI), after six months of CI use would allow such a classification. Thus, failure to reach this goal can easily be assessed by routine clinical audiometry [

3,

6]. “Unexplained poor performance” may be defined as applying to CI recipients whose WRS

65(CI) does not meet the predicted score according to this model. Such cases can be observed with an incidence of around five percent in a population with residual preoperative WRS [

6] on the basis of a 20-pp difference (WRS

GAP) between prediction and measurement in monosyllable test scores. Users who reach the predicted score later than six months after implantation (e.g., twelve months later) would not be covered by this definition [

6]. More recently, in a study by Dziemba

et al. [

11] such a definition was applied in order to identify systematic differences in postoperative fitting of CI systems in a group of well and poorly performing CI recipients, namely, the differences in audibility and the loudness growth function measured by categorical loudness scaling. An additional application of the prediction model [

3] could be the interpretation of electrophysiological measurements based on prior classification of groups of recipients in respect of the WRS

GAP. Other recent work [

8,

12,

13,

14,

15] led to the proposal and use of a setting for EABR mimicking the established acoustic broadband click. Reference values for latencies were assessed by including only CI recipients with WRS65CI of 50% or more [

13]. This approach led to improved differential diagnosis for CI recipients and improved intraoperative assessment [

13,

15,

16].

Some characteristics of CI recipients, such as rate dependence of electrophysiological measurements, indicate a potential for improvement in differential diagnostics. In the acoustic modality, rate effects in ABR are already well described [

17,

18]. Jiang

et al. [

18] reported age-dependent latencies and interpeak intervals in children as consequences of developmental effects. In our opinion this measure of auditory synaptic efficacy [

18] can be transferred to differential diagnostics in CI recipients to provide further explanation of unexpectedly poor WRS65CI values. We expect that certain damage mechanisms in hearing-impaired subjects and CI recipients may have a similar effect on rate dependence of EABRs.

Consequently, the goal of this study was to provide reference values for rate-dependent EABR in CI recipients. By including only CI users who met the predicted values of WRS65CI we aimed to open a window for differential diagnostics in CI recipients with unexpected and unexplained poor postoperative WRS65CI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Subjects

This prospective investigation included five subjects in the pilot phase and thereafter a further 20 subjects according to a power calculation based on the results of the pilot phase.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee on 10th August 2021 (BB 120/21), and all procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

The study was registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (

DRKS00026195).

Participants were recruited from the clinic’s patient population.

Inclusion criteria were:

Adulthood (minimum age 18 years) at implantation,

Implant type: CI24RE, CI400 series, CI500 series, or CI600 series (Cochlear™ Limited, Sydney, Australia),

Implant in specification according to European Consensus Statement on Cochlear Implant Failures and Explantations [

19],

WRS

65(CI) in the upper three quartiles according to classification of Hoppe

et al. [

20] and

Willingness and ability to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria were:

Demographic information for these patients is provided in

Table 1. Bilateral implantation was not an exclusion criterion; in those two cases, both ears were included in the analysis separately (#098/#107 and #271/#275).

2.2. Electrophysiological Measurements

To measure rate dependences of latencies and inter-peak latencies of EABRs, a quasi-simultaneous measurement of ECAPs and EABRs is needed. Here, it is essential to use the same stimulation mode and the same stimulation intensity for both assessments, to ensure compatibility of the data. Therefore, Dziemba

et al. [

12] introduced an intracochlear stimulation mode for the Nucleus

® CI system (EABR

CIStim). They used electrode 11 as a stimulation-active and electrode 18 as a stimulation-indifferent electrode, with a pulse width of 100 µs. This EABR

CIStim facilitates an electrical excitation covering a median length of about 80% of the length of the implanted CI electrode array.

In order to avoid possible intensity-dependent effects, a defined supra-threshold stimulation intensity of 20 CL above the individual ECAP threshold, measured with the EABRCIStim, was set. The measurements in all subjects followed the same procedure, as described below.

2.2.1. ECAP Measurements

For the unconditional avoidance of uncomfortable loud stimulation the LAPL using the EABRCIStim was estimated subjectively in a first step.

The second step was the identification of the most appropriate recording-active electrode according to Dziemba

et al. [

12]. Therefore, ECAP was measured at LAPL by stimulating all intra-cochlear electrodes, except electrodes 11 and 18, sequentially by using the extracochlear electrode (plate) MP2 as recording-indifferent electrode. The electrode with the largest ECAP amplitude at LAPL was selected as the best recording-active electrode.

In the third step, an ECAP amplitude-growth function was measured up to LAPL with the values found previously. The visual ECAP threshold was read out, taking into account a minimum signal-to-noise ratio for ECAP measurements according to Hey

et al. [

21].

Finally, the rate-dependent ECAPs were measured by using a stimulation intensity of 20 CL above the previously found threshold at stimulation rates of 11, 41, 81 and 91 stimuli per second.

2.2.2. EABR Measurements

All EABR measurement series were performed in the same stimulation mode as for the rate-dependent ECAP. The Eclipse system (Interacoustics, Middelfart, Denmark) was used to record the rate-dependent EABRs. Synchronisation between the CI system and the EABR device was achieved through a TTL-compatible trigger signal. This was sent via a commercially available cable (3.5 mm jack) from the programming interface of the CI system to the EABR recording system. The marking and labelling of all the measured potentials (ECAP and EABR) was performed according to Atcherson and Stoody [

22]. To avoid ambivalence in picking peaks, they recommended that the rightmost sample be used for marking the positive peaks and the leftmost sample be used for marking the negative peaks.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

We used boxplots for the graphical representation of the measured values.

For each user, the set of measurement data is a connected, non-normally distributed sample. Furthermore, there is no variance homogeneity of the data. Therefore, a non-parametric test must be used; we chose the Friedman rank sum test as being the most appropriate.

All statistical tests and figures were condicted with R [

23] and RStudio [

24].

3. Results

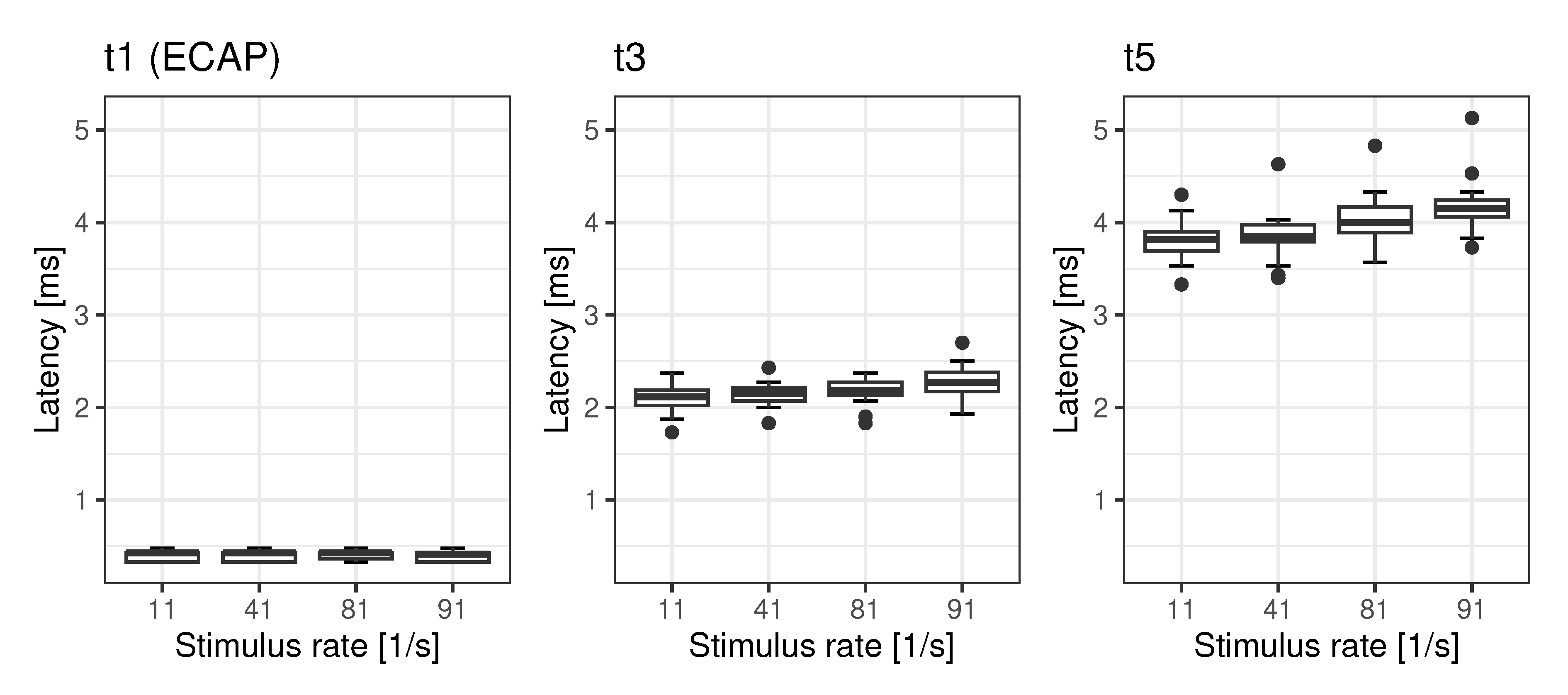

3.1. Latencies

The latencies t1, t3 and t5 of rate-dependent ECAP and EABR are shown in

Figure 1. While for the ECAP no rate effect on latency t1 was seen (

), we found significant mean rate effects for latency t3 (0.19 ms) and t5 (0.37 ms) The

post-hoc analyses of the rate effects of t3 and t5 are summarised in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

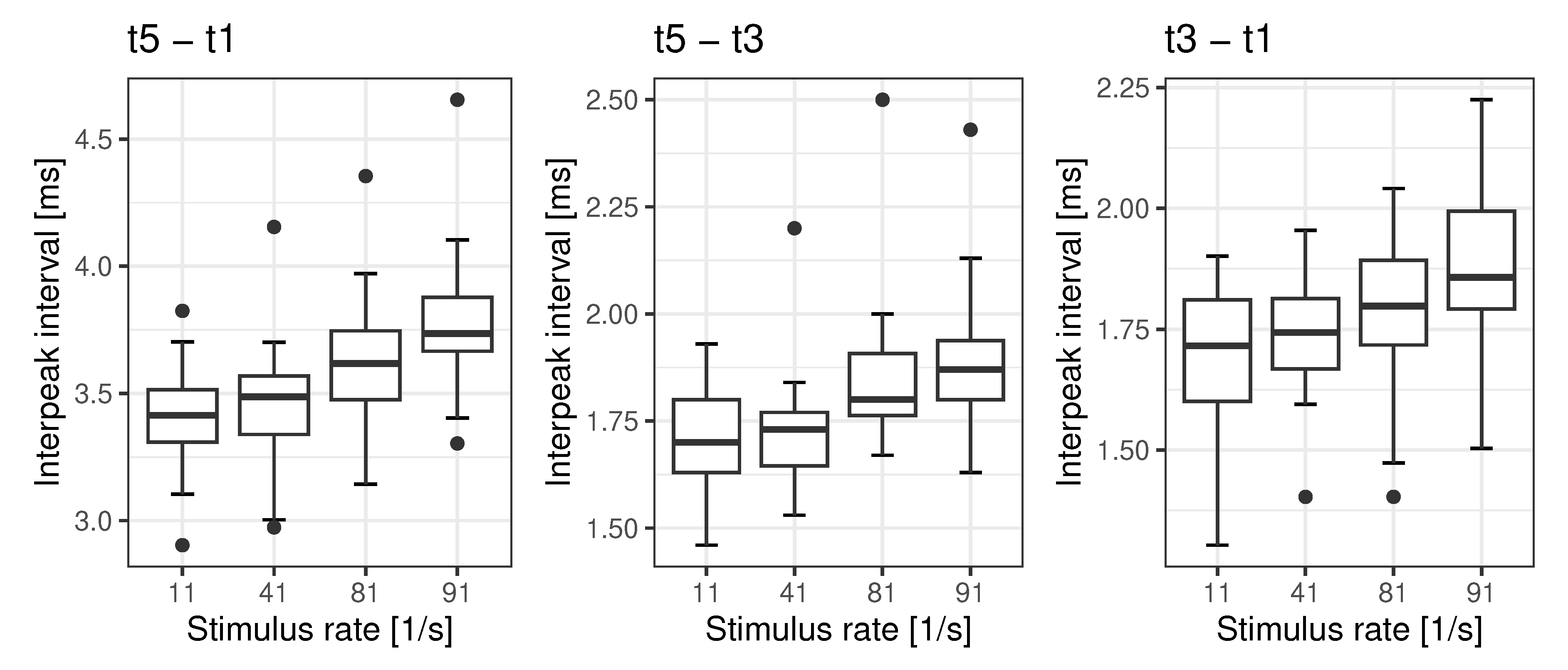

3.2. Interpeak Intervals

The interpeak intervals

,

and

of rate-dependent ECAPs and EABRs are shown in

Figure 2. We found significant rate effects for all the interpeak intervals analysed. The interpeak interval

shows a rate effect of 0.37 ms, while the interpeak interval

is shows a rate effect of 0.18 ms. The mean rate effect on interpeak interval

is 0.19 ms. The analyses are summarised in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6.

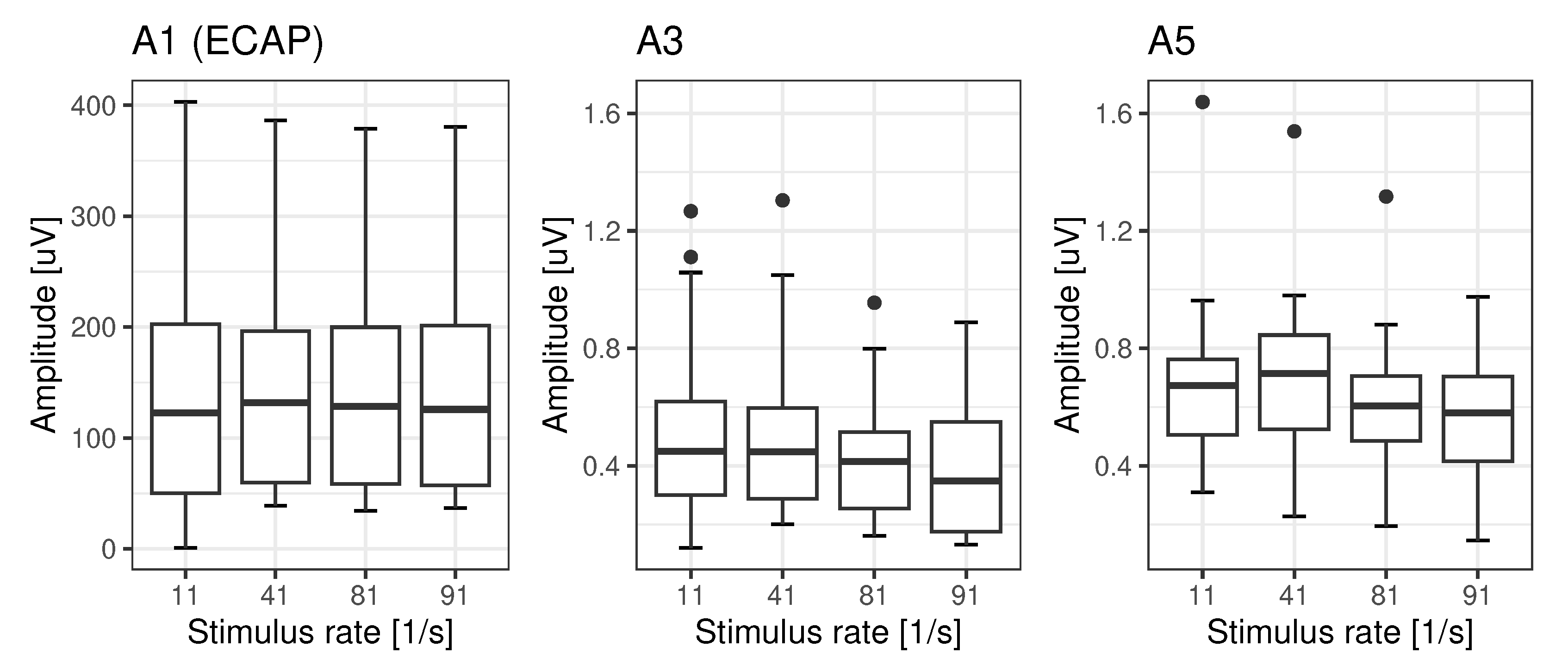

3.3. Amplitudes

The amplitudes A1, A3 and A5 of rate-dependent ECAPs and EABRs are shown in

Figure 3. While for ECAP there is no rate effect on A1 (

), we found significant detrimental rate effects, for A3 and A5, with respective mean reductions of 73% and 81%. The

post-hoc analyses of the rate effects of A3 and A5 are summarised in

Table 7 and

Table 8.

4. Discussion

In accordance with the study’s goals we investigated the rate dependences in our population of CI recipients, all of whom had monosyllabic word recognition within the upper three quartiles according to the classification put forward by Hoppe

et al. [

20]. We found rate dependences for EABR latency t3 and t5 in the order of 0.19 ms and 0.37 ms respectively, while ECAPs were not affected by rate. Correspondingly, the interpeak intervals’ rate dependences for

,

and

were found to be in the order of 0.37 ms, 0.18 ms and 0.19 ms. Jiang

et al. [

18] described the change of rate dependence in acoustic ABR as an effect of the maturing auditory pathway in children of various ages. In adults the latency changes with rate are probably related to synaptic adaptation [

17]. With respect to the amplitudes, Campbell

et al. [

25] have stated that the change in wave V of acoustic ABR does not decrease at 81/s by more than 28% compared with the amplitude at 11/s. However, in our population we found significant detrimental rate effects: a reduction down to 73% for A3 and down to 81% for A5. This is within the range for rate-dependent changes found for wave V in acoustic ABR [

25]. To summarise, these reference values for EABR and ECAP latencies, interpeak intervals and amplitudes provide a basis for possible differential diagnoses after cochlear implantation.

We hypothesize that in postlingually deafened adults with CI larger changes of amplitudes and latencies due to rate (in comparison with references values) can be interpreted as pathological effects. The values shown above can be regarded as reference values. Pathologies may then be revealed in significant deviations from them. For example, in patients with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder the dyssynchronous neural activity may affect temporal encoding of electrical stimulation from a cochlear implant [

26]. Even though Fulmer

et al. [

26] investigated the recovery function of ECAP, one may reasonably assume that EABR measurements and their rate dependences will be affected by these pathological mechanisms as well. Continuing this line of thought, we would ardue that, compared with ECAP, EABR assesses the higher levels of the auditory pathway as well and therefore appears to offer a valuable complement within differential diagnostics. However, while ECAP can be considered to provide tonotopic information, the EABR as applied in this study will provide integrated information about the status of the auditory pathway. This differential diagnostic pattern is especially important for the most recent CI population [

3,

4,

5,

6] with higher preoperative speech recognition scores. In this patient population a highly predictive outcome was observed [

3,

6] compared with the established patient population with no preoperative speech perception [

6,

27].

Consequently, if in the patient population with good audiometric preoperative conditions [

6] the prediction cannot be achieved, an underlying pathology of the auditory pathway may be suspected. Moreover, approaches utilising advanced measurements of ECAPs [

8,

28,

29,

30,

31] and the assessment of EABR and its rate dependences might be suitable in analogy to the findings in acoustic ABR. With values up to 0.28 ms the standard deviation for the interpeak interval

seems to be slightly higher than the 0.23 ms found by Campbell

et al. [

25]. A more thorough analysis will be needed in future studies.

Assuming a higher standard deviation (which still has to be confirmed) this may have its root cause in the inclusion criteria of the CI population. For acoustic stimulation, normative values, and the population in which to assess them, are easy to define as one has by definition to include normal-hearing subjects. In the case of CI recipients the definition of a reference group is far more challenging. There are no generally agreed criteria for the derivation of a reference group. Consequently, the reference values provided by this study can potentially be improved by better outcome prediction models and, based on this, a narrower patient selection.

Recently, Hoppe

et al. [

6] applied the criterion “unexpectedly poor speech perception” defined as monosyllabic speech recognition ≥ 20 pp lower than predicted after six months, in order to discuss the time course of such cases. The six months were derived from study which found that 90% of the final score is achieved after 6.9 months. Even if in that study [

6] the majority of subjects who were poor perfomer after six months nonetheless reached the target value after a longer time period, there remain 5% of cases in which the prediction is not reached in the long run. The aim of differential diagnostics using EABR would be to differentiate between a patient’s intrinsic root causes for unexpectedly poor speech perception (pathologies) or causes in which the fitting of CI system also plays a part [

11]. Future studies with a focus on the time course of postoperative speech recognition with respect to different pathologies (once these are confirmed) will be needed to refine the diagnostics using EABR.

5. Conclusions

The rate-dependences of latency and amplitude in EABR have characteristics comparable to those of acoustic ABR. Consequently, EABR may potentially support differential diagnosis in CI recipients with an outcome below expectation. The results of this study may serve to provide reference values. Pathological issues of the peripheral auditory pathway hindering a postoperative increase in speech perception and CI outcome in general can be excluded or confirmed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.D.; methodology, O.D., T.H. and F.I.; software, O.D.; validation, O.D.; formal analysis, O.D.; investigation, O.D.; resources, O.D., T.B., T.H. and F.I.; data curation, O.D.; writing—original draft preparation, O.D. and T.H.; writing—review and editing, O.D., F.I. and T.B.; visualization, O.D.; supervision, F.I.; project administration, O.D. and T.H.; funding acquisition, O.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Cochlear™ Research an Development Limited grant number IIR-2311.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval: BB 120/21, This study was registered in German Clinical Trials Register under DRKS-ID:

DRKS00026195.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

No Acknowledgements.

Conflicts of Interest

O.D. received funding in other projects and travel money. T.H. is employee of Cochlear Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG. T.B. and F.I. declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ABR |

auditory brainstem responses |

| CL |

current level |

| CI |

cochlear implant |

| EABR |

electrically evoked auditory brainstem responses |

| ECAP |

electrically evoked compound action potentials |

| EABRCIStim |

EABR stimulation mode according to [12] |

| IQR |

interquartile range |

| LAPL |

loudest acceptable presentation level |

| pp |

percentage-points |

| WRS |

word recognition score |

| WRS65(CI) |

word recognition score with cochlear implant at 65 dB |

References

- Buchman, C.A.; Gifford, R.H.; Haynes, D.S.; Lenarz, T.; O’Donoghue, G.; Adunka, O.; Biever, A.; Briggs, R.J.; Carlson, M.L.; Dai, P.; et al. Unilateral Cochlear Implants for Severe, Profound, or Moderate Sloping to Profound Bilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review and Consensus Statements. JAMA otolaryngology– head & neck surgery 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hals-Nasen-Ohren-Heilkunde, Kopf- und Hals-Chirurgie e.V.. S2k-Leitlinie Cochlea-Implantat Versorgung, 2020.

- Hoppe, U.; Hocke, T.; Hast, A.; Iro, H. Cochlear Implantation in Candidates With Moderate-to-Severe Hearing Loss and Poor Speech Perception. The Laryngoscope 2021, 131, E940–E945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thangavelu, K.; Nitzge, M.; Weiß, R.M.; Mueller-Mazzotta, J.; Stuck, B.A.; Reimann, K. Role of cochlear reserve in adults with cochlear implants following post-lingual hearing loss. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology and Head & Neck 2023, 280, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieck, J.H.; Beyer, A.; Mewes, A.; Caliebe, A.; Hey, M. Extended Preoperative Audiometry for Outcome Prediction and Risk Analysis in Patients Receiving Cochlear Implants. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppe, U.; Hast, A.; Hocke, T. Validation of a predictive model for speech discrimination after cochlear impIant provision. HNO 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberly, A.C.; Bates, C.; Harris, M.S.; Pisoni, D.B. The Enigma of Poor Performance by Adults With Cochlear Implants. Otology & Neurotology 2016, 37, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoth, S.; Dziemba, O.C. The role of auditory evoked potentials in the context of cochlear implant provision: Presented at the Annual Meeting of ADANO 2015 in Bern. Otology & Neurotology 2017, 38, e522–e530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, M.S.; Warnecke, A.; Staecker, H. A Window of Opportunity: Perilymph Sampling from the Round Window Membrane Can Advance Inner Ear Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawn, R.J.; Nassiri, A.M.; Rivas, A. Auditory Neuropathy: Bridging the Gap Between Hearing Aids and Cochlear Implants. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America 2019, 52, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziemba, O.C.; Merz, S.; Hocke, T. Zur evaluierenden Audiometrie nach Cochlea-Implantat-Versorgung. HNO 2023, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziemba, O.C.; Hocke, T.; Müller, A.; Kaftan, H. Excitation characteristic of a bipolar stimulus for broadband stimulation in measurements of electrically evoked auditory potentials. Zeitschrift für Medizinische Physik 2018, 28, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziemba, O.C.; Hocke, T.; Müller, A. EABR on cochlear implant – measurements from clinical routine compared to reference values. GMS Zeitschrift für Audiologie — Audiological Acoustics 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmann, L.C.; Strahlenbach, A.; Hans, S.; Lang, S.; Arweiler-Harbeck, D. Visualizing Contralateral Suppression of Hearing Sensitivity via Acoustic and Electric Brainstem Audiometry in Bimodal Cochlear Implant Patients: A Feasibility Study. Audiology and Neurotology 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahne, T.; Hocke, T.; Strauß, C.; Kösling, S.; Fröhlich, L.; Plontke, S.K. Perioperative Recording of Cochlear Implant Evoked Brain Stem Responses After Removal of the Intralabyrinthine Portion of a Vestibular Schwannoma in a Patient with NF2. Otology & Neurotology 2019, 40, e20–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Feick, J.; Dziemba, O.C.; Mir-Salim, P. Objective Diagnostics and Therapie of Hearing Loss Several Years after Cochlear Implant. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie 2016, 95, 634–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picton, T.W. Human auditory evoked potentials; Plural Publishing: San Diego, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.D.; Wu, Y.Y.; Zheng, W.S.; Sun, D.K.; Feng, L.Y.; Liu, X.Y. The effect of click rate on latency and interpeak interval of the brain-stem auditory evoked potentials in children from birth to 6 years. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology 1991, 80, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Consensus Statement on Cochlear Implant Failures and Explantations: Editorial. Otology & Neurotology 2005, 26, 1097–1099. [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, U.; Hocke, T.; Hast, A.; Iro, H. Maximum preimplantation monosyllabic score as predictor of cochlear implant outcome. HNO 2019, 62, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hey, M.; Müller-Deile, J. Accuracy of measurement in electrically evoked compound action potentials. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2015, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atcherson, S.R.; Stoody, T.M. (Eds.) Chapter 3: Principles of Analysis an Interpretation. In Auditory Electrophysiology; Thieme: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. In R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021.

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R, 2023.

- Campbell, K.B.; Picton, T.W.; Wolfe, R.G.; Maru, J.; Baribeau-Braun, J.; Braun, C. Auditory Potentials. Sensus 1981, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer, S.L.; Runge, C.L.; Jensen, J.W.; Friedland, D.R. Rate of neural recovery in implanted children with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery 2011, 144, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafieibavani, E.; Goudey, B.; Kiral, I.; Zhong, P.; Jimeno-Yepes, A.; Swan, A.; Gambhir, M.; BUECHNER, A.; Kludt, E.; Eikelboom, R.H.; et al. Predictive models for cochlear implant outcomes: Performance, generalizability, and the impact of cohort size. Trends in Hearing 2021, 25, 23312165211066174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botros, A.; Psarros, C. Neural Response Telemetry Reconsidered: II. The Influence of Neural Population on the ECAP Recovery Function and Refractoriness. Ear and Hearing 2010, 31, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Briaire, J.J.; Stronks, H.C.; Frijns, J.H.M. Speech Perception Performance in Cochlear Implant Recipients Correlates to the Number and Synchrony of Excited Auditory Nerve Fibers Derived From Electrically Evoked Compound Action Potentials. Ear and Hearing 2023, 44, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Goehring, T.; Cosentino, S.; Turner, R.E.; Deeks, J.M.; Brochier, T.; Rughooputh, T.; Bance, M.; Carlyon, R.P. The Panoramic ECAP Method: Estimating Patient-Specific Patterns of Current Spread and Neural Health in Cochlear Implant Users. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology 2021, 22, 567–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Abbas, P.J.; Doyle, D.V.; McFayden, T.C.; Mulherin, S. Temporal Response Properties of the Auditory Nerve in Implanted Children with Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder and Implanted Children with Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Ear and Hearing 2016, 37, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).