1. Introduction

Iron is an essential micronutrient for humans and microbiota, exerting direct effects on microbial growth, modulating the host immune system, and participating in various biochemical processes essential for sustaining life [

1,

2]. In the human body, the intricate interaction between host iron acquisition and the gut microbiota plays a crucial role in shaping the metabolism of both the host and microbiota. The microbiome ecology influences iron absorption, while iron uptake, deficiency, or overload in the host will affect the community, diversity, and function of the microbiota, thus disrupting the micro-ecological balance [

3].

Recent evidence has suggested that maternal dietary iron intake during pregnancy may impact the development of the maternal and infant gut microbiota [

4,

5]. High maternal dietary iron intake or supplementation during pregnancy has been linked with alterations in the infant gut microbiota composition, potentially increasing the relative abundance of pathogenic bacteria and decreasing that of beneficial bacteria [

4,

6], thus increasing the risk of infections, allergies, and metabolic disorders in the infant. In addition, as a vital micronutrient, iron is closely related to the metabolism of the gut microbiota. A study in rats has shown that iron deficiency decreased the concentrations of cecal butyrate (87%) and propionate (72%), as well as strongly modifying dominant species including Lactobacilli and Enterobacteriaceae [

7]. Iron depletion and repletion strongly impact the composition and function of the gut microbiota, while in humans the relationship between maternal dietary iron intake and the characteristics of the mother and neonate gut microbiota remains poorly understood.

Therefore, in this study, we aim to investigate the association between maternal dietary iron intake during pregnancy and the gut microbiota characteristics of the mother and neonate in a well-characterized cohort. Our findings are expected to contribute to a better understanding of the role of maternal iron status in shaping the gut microbiota in the neonate, and may inform future dietary recommendations for pregnant women.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and participant enrollment

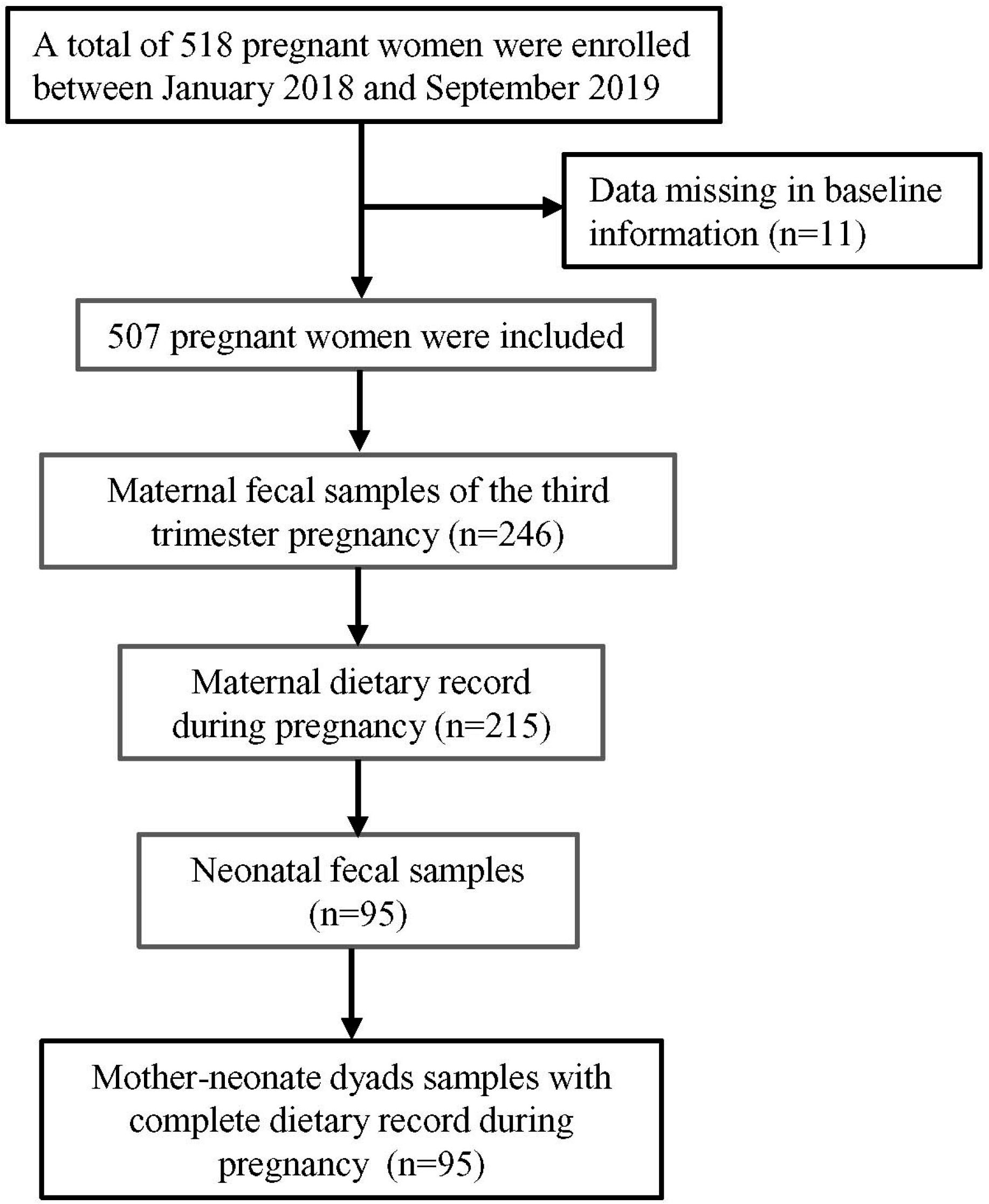

The study was based on a birth cohort from January 2018 to June 2019, and the mothers were enrolled in a randomized controlled trial in Northwest China. Detailed information of the cohort has been described elsewhere [

8,

9]. A total of 518 women were enrolled and 246 maternal fecal samples in the third trimester of pregnancy were collected. After delivery, fecal samples were collected from 220 mother–neonate dyads and, after combining this data with complete maternal dietary records, 95 mother–neonate dyads were included in our study. The flowchart of participant enrollment is shown in

Figure 1.

The inclusion criteria for the present study included: (1) Women with full-term singleton fetus; (2) women with detailed dietary record during pregnancy; (3) women without diagnosed gestational complications; (4) matched information and fecal samples of the mother–neonate dyads. The exclusion criteria of the study were (1) Unable to complete the questionnaire or sample collection as required; (2) poor quality of the sample.

A detailed explanation of the study was provided to the women when recruited, and written consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Xi’an Jiaotong University Health Science Center (No. 2018-293).

2.2. Basic information collection

A face-to-face questionnaire survey was used to collect information from the mothers during their antenatal care (ANC) visits. In the initial ANC visit, data about the maternal socio-demographic characteristics and reproductive history of the mother were collected. In each following ANC visit, details regarding the pregnancy were also documented, including environmental exposures, psychological disorders, disease and treatment, and nutritional supplements during pregnancy [

8]. Birth outcomes were retrieved from the hospital information system.

2.3. Assessment of maternal dietary iron intake during pregnancy

A 107-item semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) with good reliability and validity for pregnant women in Shaanxi Province of China was used to evaluate the diet of the mother once, either before or within 3 days after delivery [

10,

11,

12]. Specifically, we converted the daily food consumptions into total energy, macronutrient, and micronutrient intakes referring the Chinese Food Composition Table [

13], which was then analyzed (after energy adjustment) using the regression-residual method [

14]. Given that the pregnant women in this region generally have low dietary iron intake, we divided the women into two groups based on the recommended nutrient intake (RNI) of iron in the first trimester (20mg/d) for Chinese women provided by Chinese Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) in China in 2013 [

15]; in particular, we grouped them by iron intake ≥20 mg/d and <20 mg/d.

2.4. Fecal sample collection

The third trimester maternal fecal samples were collected in hospital, and neonate fecal samples were collected from the diapers by parents or investigators within 3 days after birth. The fecal samples were sub-packed and labeled before being swiftly moved to a −20 °C fridge for short-term storage, then transferred to the laboratory and stored in a −80°C fridge until subsequent analysis.

2.5. DNA extraction and high-throughput 16s rRNA gene amplicon sequencing

Bacterial DNA was extracted from 500 mg of each fecal sample using a QIAamp Fast DNA stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR amplification was conducted with barcoded bacterial primers (341F: 5′-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3′ and 806R: 5′-GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT-3′ [

16]), targeting the variable region V3-V4 of the 16S rRNA gene, followed by application of the Hiseq 2500 platform at Biomarker Technologies Co, Ltd. (Beijing China) to identify individual microbiota in the fecal samples. The original data obtained by the high-throughput sequencing platform were stored in FASTQ format file, which comprised the information of reads and corresponding the quality of sequences. The raw data processing contains two steps. First, raw data were filtered using Trimmomatic v0.33 [

17] and the primer sequences were identified and removed using cutadapt 1.9.1 [

18], generating high-quality reads without primer sequences. Then, using DATA2 [

19] in QIIME 2020.6 [

20] for denoising and the removal of chimeric sequences, non-chimeric reads were generated. The taxonomic annotation of feature sequences was processed using the reference database Silva 16S rRNA version 115 [

21]. After quality control, amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were inferred.

2.6. Bioinformatic and statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with Stata 15.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX), while microbial analyses were conducted with R (version 4.1.0). Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables are presented as ratios or percentages, which were analyzed via Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. The significance level was set as

p < 0.05. The Phyloseq package [

22] was used to create an object including the ASV table, sample variables, and taxonomy table for the measurement of diversity indices and microbiota analysis in R. Considering that we wished to maximally retain the diversity of fecal samples, we kept the sequencing depth of each sample without rarefaction [

23]. In addition, considering the low biomass in neonate fecal samples and potentially spurious taxa due to sequencing errors, we filtered the ASV data using the filter_taxa function, and only ASVs present at least 2 counts in at least 10% of fecal samples (e.g., based on our sample size, ASVs present in at least 15 fecal samples) were retained. The microbiota characteristics of fecal samples were compared between the maternal dietary iron intake groups, then further stratified by delivery mode for analyses to minimize the effect on the result. Alpha diversity indices including Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson diversity were calculated via filtered ASV table using the microbiota package [

24], while differences in the alpha diversity indices were analyzed via Mann–Whitney U test. Beta diversity assessment was carried out using the vegan package [

25]. To identify the effect of maternal dietary iron intake on the maternal/neonatal gut microbiota community, permutation multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) with 9999 permutations was conducted using the adonis2 function in the vegan package, stratified by delivery mode and adjusting for the effect of potential confounding variables such as pre-pregnancy BMI, and iron supplementation during pregnancy. Then, visualization of beta diversity in relation to delivery mode and maternal dietary iron intake was conducted via Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) using the vegan [

25] and ggplot2 [

26] packages. Moreover, gut microbiota composition was compared at phylum level, with top phyla visualized using the plot_composition function. Neonate fecal samples were then stratified by delivery mode compared at genus level with top genera.

Additionally, the core genera consistently present in the majority of neonate and maternal gut microbiota samples were identified using the core_members function of the microbiome package. Specifically, a threshold of 0.01% in 75% of neonate fecal samples, and a threshold of 0.01% in 95% of maternal fecal samples were applied to identify the core genera, respectively. The resulting core genera were subjected to the compositional transform and visualized using ggplot2. The shared core ASVs among groups in maternal and neonate fecal samples were illustrated using Venn diagrams generated using the microbiome and eulerr packages. Additionally, Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA), which helped to determine the association between variables and microbiota structure, was conducted to analyze the association between maternal dietary iron intake and microbiota at the genus level. Gene functions were assessed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). Finally, differences in taxonomic abundance were assessed between the low and high intake groups stratified by delivery mode, performed using Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction (ANCOM-BC) (v1.2.2) [

27], with adjustments made for neonate feeding, maternal use of Intrapartum Antimicrobial Prophylaxis (IAP), iron supplementation during pregnancy, and batch effect. Correction values obtained from the models were adjusted via the Bonferroni method (

q < 0.05). Taxa with a proportion of zeroes greater than 90% were excluded.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics and maternal dietary iron intake during pregnancy

Among the 95 mother–neonate dyads, 73.7% of neonates were delivered vaginally, and male and female neonates were observed in equal numbers. The baseline characteristics of the mothers and neonates are summarized in

Table 1. The maternal dietary iron intake was determined with a median (IQR) of 19.4 (16.9–21) mg/d.

3.2. Sequencing characteristics of mother–neonate dyads

In general, after filtering and removing sparse reads, from the 190 fecal samples were acquired 8,418,876 reads comprising 299 ASVs obtained for analysis, representing 87% of the ASVs. Specifically, the average number of reads per neonate sample were 44,236, and the range was 723–82,798; meanwhile, the average number of reads per mother sample was 44,383, and the range was 18,127–72,289.

3.3. Overview of maternal and neonate gut microbiota composition

The microbiota distribution in groups is shown in

Supplementary Figures S1 and S2. Firmicutes was the dominant phylum in the maternal gut microbiota, with relative abundance of 0.61 ± 0.2 [mean (%) ± SD (%)], and there was no significant difference between maternal dietary iron intake <20 mg/d and ≥20 mg/d groups.

In the neonate gut microbiota, Proteobacteria was the dominant phylum, followed by Firmicutes with relative abundance of 0.41 ± 0.32 and 0.3 ± 0.25 [mean (%) ± SD (%)], respectively, in the vaginal delivery group. Firmicutes and Proteobacteria with relative abundance of 0.44 ± 0.28 and 0.33 ± 0.31 [mean (%) ± SD (%)], respectively, were the top two dominant phyla in the cesarean section group. Non-parametric tests with Bonferroni corrections showed no significant difference in relative abundance between maternal dietary iron intake <20 mg/d and ≥20 mg/d groups, at not only phylum but also genus level (p > 0.05).

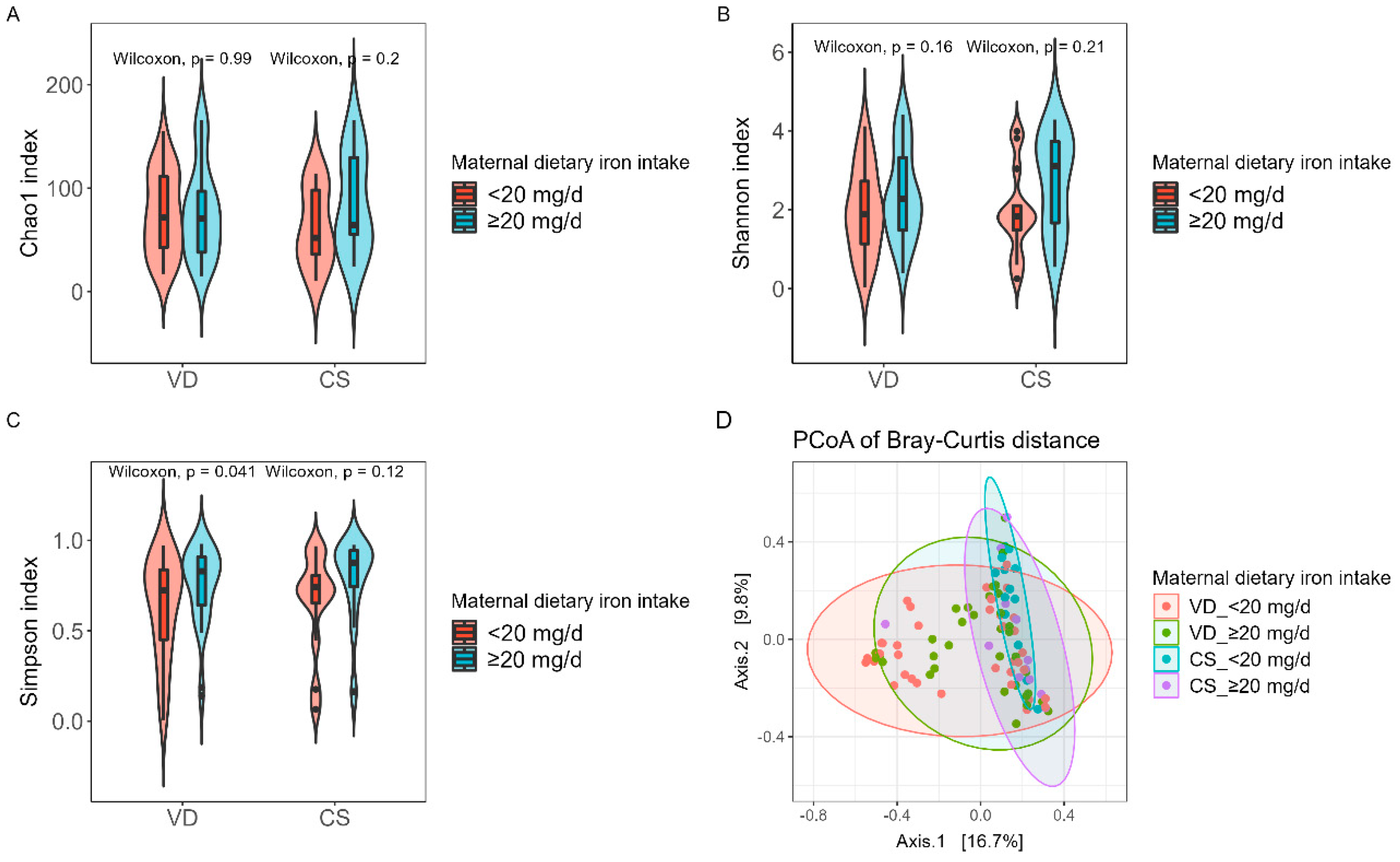

3.4. Impact of maternal dietary iron intake on gut microbiota diversity of mother and neonate

The alpha and beta diversity of mother fecal samples showed no significant difference between low and high dietary iron intake groups (

Supplementary Figure S3). However, the Shannon and Simpson indices in the ≥20 mg/d group were significantly higher than in the <20 mg/d group for neonate fecal samples (Shannon index,

p = 0.044; Simpson index,

p = 0.010;

Supplementary Figure S4). Meanwhile, after stratification (

Figure 2), the results showed the same tendency regarding Simpson diversity between the <20 mg/d and ≥20 mg/d groups in VD neonates (

p = 0.041), and no significant difference was observed for Chao1 and Shannon diversity. Furthermore, beta diversity presented no significant difference in neonate microbial community structure between the four groups (

Figure 2D,

p > 0.05).

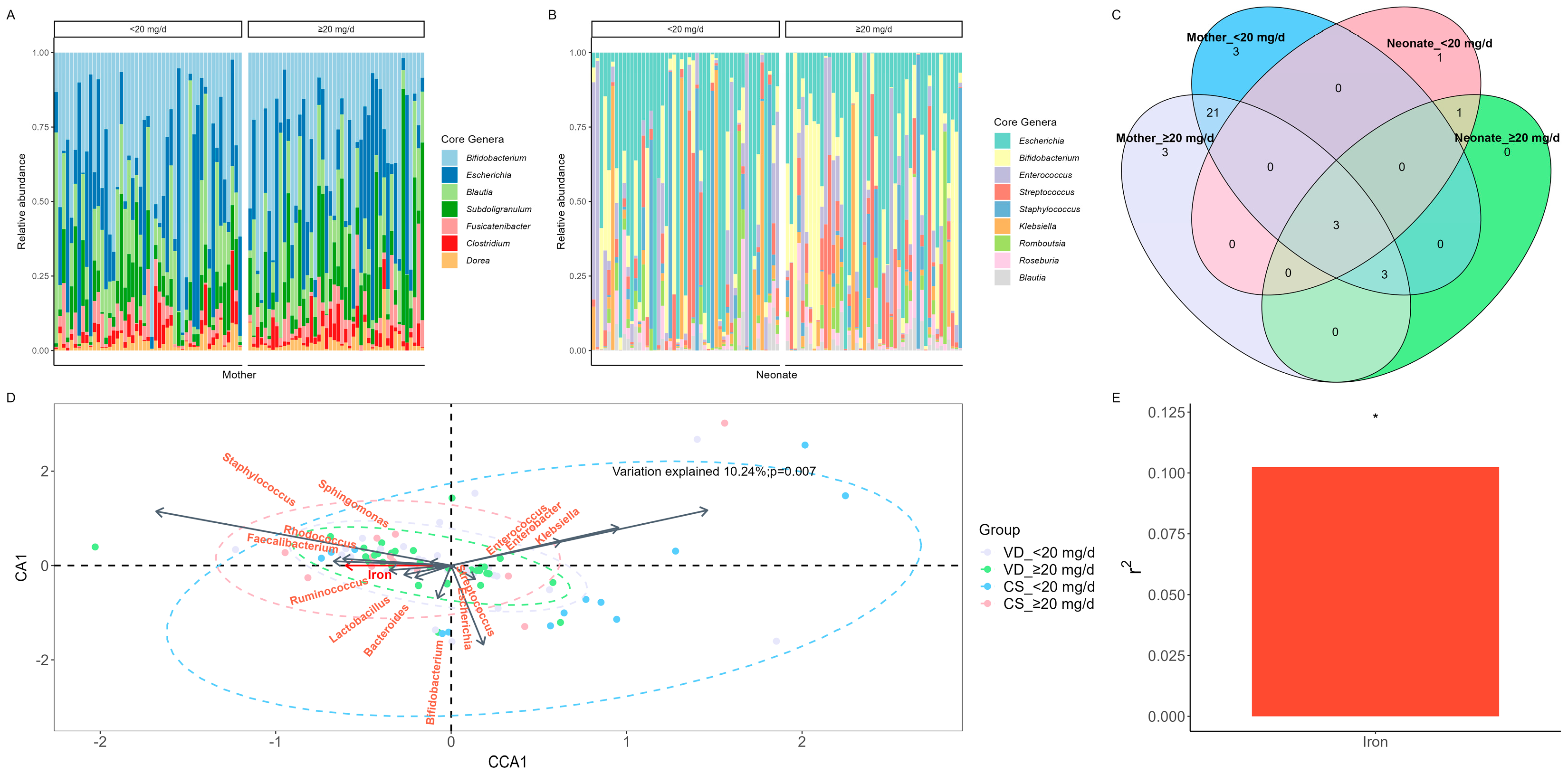

3.5. Core genera and shared ASVs in mother–neonate dyads

There were 7 core genera in the 95 maternal fecal samples (

Figure 3A). The most dominant core genus in the maternal gut microbiota was

Bifidobacterium, followed by

Escherichia and

Blautia (

Table 2). There were no significant differences between the maternal dietary iron intake <20 mg/d and ≥20 mg/d groups.

There were 9 core genera in neonate fecal samples, with the top 3 dominant genera being

Escherichia, Bifidobacterium, and

Streptococcus (

Figure 3B;

Table 2). The relative abundance of

Bifidobacterium was significantly higher in the ≥20 mg/d group than in the <20 mg/d group (

p = 0.044); however, no significant difference was observed in the remaining 8 core genera between groups.

Shared ASVs between mother and neonate gut microbial compositions are shown in

Figure 3C. Among the ASVs, 3 ASVs were shared between the <20 mg/d group in mother and neonate fecal samples (ASV1, ASV2, ASV3), while 6 ASVs were shared between the ≥20 mg/d group in mother and neonate fecal samples (ASV1, ASV2, ASV3, ASV7, ASV9, ASV10); see

Supplementary Table S1. The most dominant shared species in the mother and neonate gut microbiota were ASV1 (

Escherichia_coli), ASV2 (

Bifidobacterium_pseudocatenulatum), and ASV3 (

Bifidobacterium_longum).

3.6. General attributes of maternal dietary iron intake during pregnancy with respect to neonate fecal microbiota

CCA was performed at genus level (

Figure 3D).

Staphylococcus, Fecalibacterium, Lactobacillus, and

Bifidobacterium were positively correlated with maternal dietary iron intake, and were enriched in the VD_<20 mg/d, VD_≥20 mg/d and CS_ ≥20 mg/d groups, with

Staphylococcus presenting the highest correlation, and

Lactobacillus, and

Bifidobacterium having lower correlation.

Klebsiella was negatively correlated with maternal dietary iron intake, and was enriched in the CS_<20 mg/d group. Additionally, there was a significant difference between maternal dietary iron intake and neonate gut microbiota community structure (E). The variation explained by maternal dietary iron intake was 10.24% (

p = 0.007).

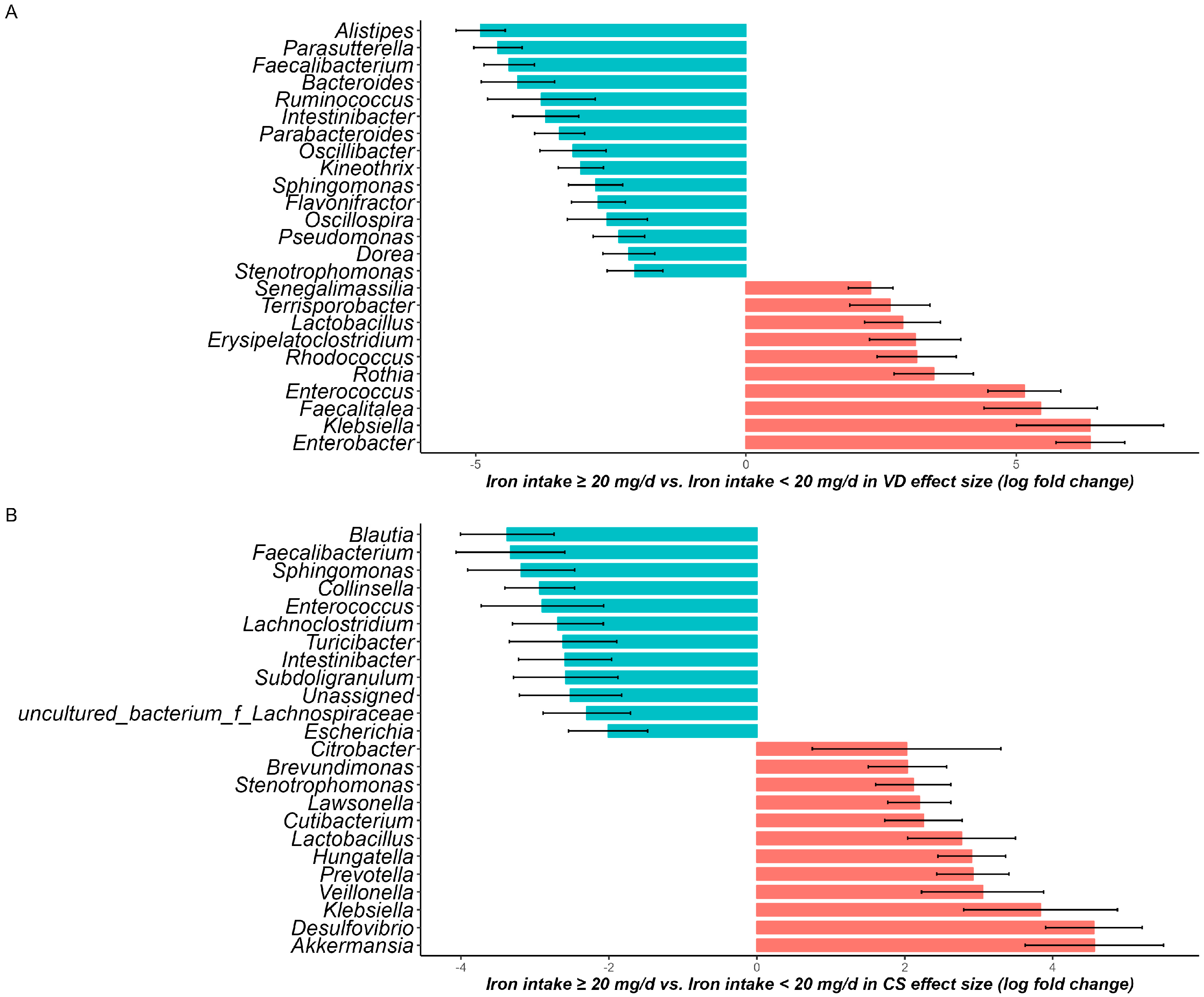

3.7. Effects of maternal dietary iron intake on neonate gut microbiota composition and function

The ANCOM-BC results for neonate gut microbiota with adjustment for covariates are shown in

Figure 4A,B, and

Supplementary Table S2. Specifically, in the VD group, 35 genera were found significantly different. In the <20 mg/d group, the abundances of 21 genera were found to be differential, and the top 3 genera were

Alistipes (beta = −4.91, w = −10.8,

q < 0.001),

Parasutterella (beta = 6.37, w = −10.01,

q < 0.001), and

Fecalibacterium (beta = −4.38, w = −9.4,

q < 0.001). Meanwhile, 14 genera were found to be differential in the ≥20 mg/d group, where

Enterobacter (beta = −4.59, w = −10.27,

q < 0.001) was the highest. In the CS group, the abundances of 45 genera were found to significantly different, with 18 genera showing high differences in the <20 mg/d group and 27 genera showing high differences in the ≥20 mg/d group. Notably, under both delivery modes, the abundance of

Lactobacillus was differential in the ≥20 mg/d group (VD: beta = 2.9, w = 4.13; CS: beta = 2.77, w = 3.8).

Additionally, KEGG annotation analysis in the four groups of neonate gut microbiota showed a diverse array of functional genes, with the top 5 involved in Metabolic pathways, Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, Biosynthesis of antibiotics, Microbial metabolism in diverse environments, and ABC transporters. No significant differences were observed between the four groups.

4. Discussion

Our results revealed that maternal dietary iron intake during pregnancy is associated with neonate gut microbiota diversity, affects the core genera in the neonate gut microbiota, and has a positive influence on the neonate gut microbiota at genus level. Our findings suggest that, in rural areas, adequate dietary iron intake during pregnancy is important for healthy neonate gut microbiota development.

Adequate iron intake during pregnancy is essential for both the mother’s health and the neonate’s development. Our study confirmed that above the recommended maternal dietary iron intake, the iron levels increase the Shannon and Simpson indices with respect to the neonate’s gut microbiota. After stratification by delivery mode, higher maternal dietary iron intake significantly increased the Simpson diversity of the gut microbiota in vaginally delivered neonates, with the same tendency when not stratified; however, the limited number of fecal samples after stratification may lower the ability to detect the difference in Shannon diversity. This association may due to the positive effects between iron and microbiota metabolism, especially through vaginal delivery.

Notably, the core genus

Bifidobacterium was commonly found in neonate gut microbiota, and presented a significant difference between the <20 mg/d and ≥20 mg/d groups of this study.

Bifidobacterium is an essential part of the human gut microbiota, and is one of the earliest beneficial and dominant microbiota in the neonate intestinal tract. Studies have shown that

Bifidobacterium promotes the development and maturation of the immune system, maintaining a dynamic balance of the gut microbiota [

28,

29]. However, no consistent conclusion has been drawn regarding the association between iron and

Bifidobacterium in the neonate gut. Iron is an essential nutrient for many microbiota species, including

Bifidobacterium, and moderate dietary iron intake may promote the colonization and development of beneficial microbiota [

30]. On the contrary, studies have shown that, in an iron-fortified diet, increased iron in the colon decreased the abundance of

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus and increase the abundance of enteropathogenic

Escherichia coli, which has been associated with enteritis [

31,

32,

33], thus highlighting the importance of rational dietary iron intake for microbiota efficacy. Our results preliminarily indicate that satisfying the recommended maternal dietary iron intake may increase the relative abundance of

Bifidobacteria in the neonatal offspring in iron-deficient areas; however, this association may be further studied using an expanded sample size.

Additionally, shared ASVs in the <20 mg/d and ≥20 mg/d groups indicated the transfer of microbiota from mother to neonate. As shown in our study,

Escherichia_coli, Bifidobacterium_pseudocatenulatum, and Bifidobacterium_longum were common species in the mother and neonate gut microbiota; furthermore,

Streptococcus_salivarius,

Blautia_obeum, and

Roseburia_faecis were shared in the ≥20 mg/d group between mother and neonate fecal samples. The association between these species and maternal dietary iron intake has not yet been sufficiently supported by evidence. Specifically,

Streptococcus_salivarius is a commensal microbiota that commonly colonizes the oral cavity and upper respiratory tract in humans, which has been associated with the prevention of oral infections and modulation of the immune system. In neonates,

S. salivarius has been found to prevent colonization by pathogenic bacteria, such as

Streptococcus mutans, and produces bacteriocins, which are antimicrobial peptides that can inhibit the growth of other bacteria (including

S. mutans) [

34,

35].

Blautia obeum and

Roseburia faecis are both associated with the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

B. obeum is capable of hydrolyzing bile salts, while

R. faecis has been found to produce butyrate, which is also an inhibitory substance against

Bacillus subtilis [

36,

37]. It is plausible that maternal dietary iron intake can influence the abundance or activity of these bacteria shared by the mother and neonate, given their crucial roles in maintaining gut health. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct more research to examine any possible associations between these bacterial species and maternal dietary iron intake.

In this study, we also observed a relationship between maternal dietary iron intake and representative genera in the neonate gut, as well as the differentially observed genera between groups.

Lactobacillus species were enriched in the ≥20 mg/d groups under both delivery modes, hinting at a potential connection between adequate iron intake and the presence of

Lactobacillus. However, existing studies have not yet reached consistent conclusions. In a randomized, double-blinded, controlled trial conducted to evaluate the efficacy of probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum 299v (LP299v) in enhancing the treatment of iron deficiency, the results indicated no significant correlation between increased ferritin levels and probiotic use. On the contrary, in a study conducted to assess the impact of

Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938, it was found that, compared with iron supplementation solely, children with iron supplementation plus

L. reuteri DSM 17938 had higher reticulocyte hemoglobin levels, suggesting an association between

L. reuteri DSM 17938 and iron in children [

38]. This cannot completely rule out the association between

Lactobacillus and dietary iron intake, due to the difference in the gut strain, however it it is clear that excessive iron intake does decrease the abundance of beneficial bacteria, including

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium [

39,

40], further emphasizing the importance of dietary iron intake within the recommended range.

Our study preliminarily evidenced an association between maternal dietary iron intake during pregnancy and neonate gut microbiota, but there are still some limitations. Although the results were stratified considering the difference in transmission of gut microbiota from mother to neonate between VD and CS, the sample size was limited, making it difficult to accurately reflect the more subtle differences. The study was carried out a less-developed area of China with generally low dietary iron intake, and the results may be extended to more areas with insufficient dietary iron intake during pregnancy; however, in areas with sufficient or high dietary iron intake, the results should be verified. In addition, the dietary iron intake of mothers was collected for the whole pregnancy and stratified using Chinese RNIs, while the recommended dietary iron intake varies throughout the three trimesters. Thus, future studies could consider the influence of dietary iron intake in different periods of pregnancy and different dietary patterns on the gut microbiota of neonates under the framework of larger samples.

5. Conclusions

Adequate iron intake during pregnancy may promote the colonization of beneficial bacteria in the neonate gut microbiota and increase its biodiversity, indicating that maternal dietary iron intake plays a role in shaping the gut microbiota of the neonate, especially in developing areas with low dietary iron intake. Therefore, different dietary intervention policies including iron supplements should be adopted, in order to ensure adequate intake of iron during pregnancy to promote healthy gut microbiota development in neonates.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: The dominant phylum composition and top phyla of mother and neonate samples; Figure S2: The dominant phylum composition, top phyla, and top genera of neonate samples; Figure S3: Alpha, beta diversity indexes of the maternal gut microbiota grouped by maternal dietary iron intake into <20 mg/d and ≥20 mg/d; Figure S4: Alpha, beta diversity indexes of the neonate gut microbiota grouped by maternal dietary iron intake into <20 mg/d and ≥20 mg/d; Table S1: Shared ASV of mother and neonate samples in Venn diagram; Table S2: ANCOM-BC data from differentially abundant genus in neonatal fecal samples in maternal dietary iron intake ≥20 mg/d and <20 mg/d.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.X.Z.; methodology, L.X.Z. and Q.Q.; software, Q.Q.; validation, L.X.Z. and Z.H.Z.; formal analysis, Q.Q., D.M.L.; investigation, Q.Q., D.M.L., L.W. and Y.Z.Z.; resources, Q.Q., D.M.L.; data curation, Q.Q., D.M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Q.; writing—review and editing, D.M.L., M.A.G., Z.H.Z. and L.X.Z.; visualization, Q.Q.; supervision, L.X.Z.; project administration, L.X.Z.; funding acquisition, L.X.Z., Z.H.Z. and Q.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 81872633; Shaanxi Provincial Innovation Capability Support Plan, grant number 2023-CX-PT-47; China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, grant number 2021M702578; China Scholarship Council, grant number 202006280219.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Xi’an Jiaotong University Health Science Centre (No. 2018-293, date 2018-3-8).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all pregnant women and their families included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank local doctors, nurses, and medical staff for the recruitment, sample, and questionnaire collection, as well as all the women and their families of the study. The author would also like to thank Professor Yue Cheng for her assistance of the manuscript writing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wessling-Resnick, M. Iron Homeostasis and the Inflammatory Response. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2010, 30, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nairz, M.; Schroll, A.; Sonnweber, T.; Weiss, G. The Struggle for Iron - a Metal at the Host-Pathogen Interface. Cell Microbiol. 2010, 12, 1691–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Moreno-Navarrete, J.M.; Fernández-Real, J.M. The Role of Iron in Host–Microbiota Crosstalk and Its Effects on Systemic Glucose Metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Frank, D.N.; Hendricks, A.E.; Ir, D.; Esamai, F.; Liechty, E.; Hambidge, K.M.; Krebs, N.F. Iron in Micronutrient Powder Promotes an Unfavorable Gut Microbiota in Kenyan Infants. Nutrients 2017, 9, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunasegaran, T.; Balasubramaniam, V.R.M.T.; Arasoo, V.J.T.; Palanisamy, U.D.; Ramadas, A. Diet Gut Microbiota Axis in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of Recent Evidence. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paganini, D.; Uyoga, M.A.; Kortman, G.A.M.; Cercamondi, C.I.; Winkler, H.C.; Boekhorst, J.; Moretti, D.; Lacroix, C.; Karanja, S.; Zimmermann, M.B. Iron-Containing Micronutrient Powders Modify the Effect of Oral Antibiotics on the Infant Gut Microbiome and Increase Post-Antibiotic Diarrhoea Risk: A Controlled Study in Kenya. Gut 2019, 68, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dostal, A.; Chassard, C.; Hilty, F.M.; Zimmermann, M.B.; Jaeggi, T.; Rossi, S.; Lacroix, C. Iron Depletion and Repletion with Ferrous Sulfate or Electrolytic Iron Modifies the Composition and Metabolic Activity of the Gut Microbiota in Rats. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Q.; Wang, L.; Gebremedhin, M.A.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Shen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Andegiorgish, A.K.; Cheng, Y.; Shi, L.; et al. The Impact of Early-Life Antibiotics and Probiotics on Gut Microbial Ecology and Infant Health Outcomes: A Pregnancy and Birth Cohort in Northwest China (PBCC) Study Protocol. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Mi, B.; Qu, P.; Liu, D.; Lei, F.; Wang, D.; Zeng, L.; Kang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Pei, L.; et al. Association of Antenatal Vitamin B Complex Supplementation with Neonatal Vitamin B12 Status: Evidence from a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Cheng, Y.; Mi, B.; Zeng, L.; Qu, P.; Li, S.; Zhang, R.; Qi, Q.; Wu, C.; Gao, X.; et al. Maternal Dietary Patterns during Pregnancy Derived by Reduced-Rank Regression and Birth Weight in the Chinese Population. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 123, 1176–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Dibley, M.J.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, L.; Yan, H. Assessment of Dietary Intake among Pregnant Women in a Rural Area of Western China. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Yan, H.; Dibley, M.J.; Shen, Y.; Li, Q.; Zeng, L. Validity and Reproducibility of a Semi-Quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire for Use among Pregnant Women in Rural China. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 17, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety & China Center for Disease Control and Prevention. China Food Composition Book 1, 2nd ed.; Peking University Medical Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W.C.; Howe, G.R.; Kushi, L.H. Adjustment for Total Energy Intake in Epidemiologic Studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65, 1220S–1228S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinese Nutrition Association. Chinese Dietary Reference Intakes; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Hou, C.; Li, N.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Yang, F.; Zeng, X.; Liu, Z.; Qiao, S. Microbial and Metabolic Alterations in Gut Microbiota of Sows during Pregnancy and Lactation. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 4490–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnet.journal 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Waste Not, Want Not: Why Rarefying Microbiome Data Is Inadmissible. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahti, L.; Shetty, S. Microbiome R Package Available online: http://microbiome. github.io.

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.R. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.5-6. Available online: https://github.com/vegandevs/vegan.

- Wickham, H. Mastering the Grammar. In ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; 2016; pp. 27–40.

- Lin, H.; Peddada, S.D. Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcon-Giner, C.; Dalby, M.J.; Caim, S.; Ketskemety, J.; Shaw, A.; Sim, K.; Lawson, M.A.E.; Kiu, R.; Leclaire, C.; Chalklen, L.; et al. Microbiota Supplementation with Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus Modifies the Preterm Infant Gut Microbiota and Metabolome: An Observational Study. Cell Rep. Med. 2020, 1, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barratt, M.J.; Nuzhat, S.; Ahsan, K.; Frese, S.A.; Arzamasov, A.A.; Sarker, S.A.; Islam, M.M.; Palit, P.; Islam, M.R.; Hibberd, M.C.; et al. Bifidobacterium Infantis Treatment Promotes Weight Gain in Bangladeshi Infants with Severe Acute Malnutrition. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabk1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.Z.; Badar, S.; O’Callaghan, K.M.; Zlotkin, S.; Roth, D.E. Fecal Iron Measurement in Studies of the Human Intestinal Microbiome. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6, nzac143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paganini, D.; Zimmermann, M.B. The Effects of Iron Fortification and Supplementation on the Gut Microbiome and Diarrhea in Infants and Children: A Review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1688S–1693S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paganini, D.; Uyoga, M.A.; Zimmermann, M.B. Iron Fortification of Foods for Infants and Children in Low-Income Countries: Effects on the Gut Microbiome, Gut Inflammation, and Diarrhea. Nutrients 2016, 8, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonyté Sjödin, K.; Domellöf, M.; Lagerqvist, C.; Hernell, O.; Lönnerdal, B.; Szymlek-Gay, E.A.; Sjödin, A.; West, C.E.; Lind, T. Administration of Ferrous Sulfate Drops Has Significant Effects on the Gut Microbiota of Iron-Sufficient Infants: A Randomised Controlled Study. Gut 2019, 68, 2095–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, A.; Furukawa, S.; Fujita, S.; Mitobe, J.; Kawarai, T.; Narisawa, N.; Sekizuka, T.; Kuroda, M.; Ochiai, K.; Ogihara, H.; et al. Inhibition of Streptococcus Mutans Biofilm Formation by Streptococcus Salivarius FruA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 1572–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, J.P.; Wescombe, P.A.; Macklaim, J.M.; Chai, M.H.C.; Macdonald, K.; Hale, J.D.F.; Tagg, J.; Reid, G.; Gloor, G.B.; Cadieux, P.A. Persistence of the Oral Probiotic Streptococcus Salivarius M18 Is Dose Dependent and Megaplasmid Transfer Can Augment Their Bacteriocin Production and Adhesion Characteristics. PLoS One 2013, 8, e65991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullish, B.H.; McDonald, J.A.K.; Pechlivanis, A.; Allegretti, J.R.; Kao, D.; Barker, G.F.; Kapila, D.; Petrof, E.O.; Joyce, S.A.; Gahan, C.G.M.; et al. Microbial Bile Salt Hydrolases Mediate the Efficacy of Faecal Microbiota Transplant in the Treatment of Recurrent Clostridioides Difficile Infection. Gut 2019, 68, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatziioanou, D.; Mayer, M.J.; Duncan, S.H.; Flint, H.J.; Narbad, A. A Representative of the Dominant Human Colonic Firmicutes, Roseburia Faecis M72/1, Forms a Novel Bacteriocin-like Substance. Anaerobe 2013, 23, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoppo, J.; Tasiringan, H.; Wahani, A.; Umboh, A.; Mantik, M. The Role of Lactobacillus Reuteri DSM 17938 for the Absorption of Iron Preparations in Children with Iron Deficiency Anemia. Korean J. Pediatr. 2019, 62, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Chassard, C.; Rohner, F.; N’goran, E.K.; Nindjin, C.; Dostal, A.; Utzinger, J.; Ghattas, H.; Lacroix, C.; Hurrell, R.F. The Effects of Iron Fortification on the Gut Microbiota in African Children: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Cote d’Ivoire. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs, N.F.; Sherlock, L.G.; Westcott, J.; Culbertson, D.; Hambidge, K.M.; Feazel, L.M.; Robertson, C.E.; Frank, D.N. Effects of Different Complementary Feeding Regimens on Iron Status and Enteric Microbiota in Breastfed Infants. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).