1. Introduction

For at least the past three decades, scholars have observed, defined (1), measured (2), and modeled social polarization, its drivers, its effects (3; 4), and its trends around the world (5; 6; 7; 8).

1 Increasing polarization tendencies have been documented for the short run (9; 10) and predicted in long run (11) unless some event or intervention changes its course.

2

The problems generated by severe societal polarization are felt in many places and in many ways—and in particular in diminished ability to solve serious societal problems demanding consensus. Besides the numerous real consequences to which they can lead, decisions resulting from such fraught processes tend to be non-robust, further accentuating political divisions and acrimony, and causing the public to lose trust in the democratic process and possibly disengage.

For example, the two political parties in the US Congress---- Democrats and Republican--are deeply polarized. As a direct result, both the Senate and the House of Representatives have great difficulties in making necessary joint decisions about important policies, such as budget allocations. Each has extremely slim majorities: in the Senate, there are 49 republicans to 48 democrats and 3 independents (caucusing with democrats who in effect hold the majority); and in the House, there are 221 republicans to 212 democrats (17). The resulting decision dynamics mostly lead to impasse. Many issues up for vote are very contentious, including, for example, nominations for necessary government positions, which remain unoccupied for extended time periods (18). Most proposals are decided on party line, meaning that they pass by the slimmest of majorities, at 1 or two vote differences. As a result, some senators and representatives acquire more power than warranted by their constituencies or seniority, because their votes are commodities sought by both parties. They can exact favors for their states or districts, angering the public (19). Yearly budget decisions are delayed to the last legal minute under threat of government closure (19). Consequences of failure to vote for the budget can be far-ranging, extending beyond the US border. For example, in Fall 2023 the House of Representatives approved a bi-partisan 45-day stopgap spending bill to prevent government closure, which did not contain continued financial support for the Ukraine. Moreover, despite relatively broad consensus on financially assisting Israel in its war which broke out on October 7, 2023, this aid cannot be extended because the House of Representatives has yet to vote for a Speaker—a party-line decision.

Polarization is especially notable and acute preceding elections in democratic countries, such as the United State (11; 23). For example, the latest of yearly Gallup polls conducted over the past 20 years regarding 24 issues central to past and current debates found increasing gaps between Democrat and Republican views (some deeper than others) for all issues, amounting to severe political polarization (23). These findings are consistent and buttressed by those of Doherty et al. (24) and Schaeffer (25).

Several factors have been viewed as causes, symptoms, and/or drivers for the observed increasing polarization among Americans. They include widespread loss of mutual trust (26), and loss of trust in government, media, and science (27; 28). Media and science have aligned themselves with politics (29), further diminishing public trust. Lack of trust may be behind the seemingly distinct, nonoverlapping and contradictory sets of data, facts, news and opinions held by members of the two groups. It is coupled with acute homophily (30), which impels individuals to communicate almost exclusively with members of their own group who share their point of view, reinforcing the information disjunction. For example, people tend to evaluate information by the party affiliation of the source, more or rather than by its content, arguments and evidence (31; 32). This way of evaluating information quality leads to wholesale rejection of any statements coming from the opposing group. It also leads to the partition of society into groups whose members have non-intersecting perceptions of reality. In turn, this prevents the groups from solving problems, which necessitates finding agreement regarding specific policies and laws even while continuing to disagree on values. Burgess et al. (3) examined several causes of polarization and proposed an additional category: bad-faith actors (4) fueling and reinforcing differences for their own purposes.

At times, such as currently in the US, a perfect storm is generated by deep value differences among opposing groups, combined with homophily (little or no direct inter-group communication) in the context of short political cycles which exacerbate both the differences and the homophily. In the face of the societal damage driven by polarization, scholars have been turning their attention to various theoretical and practical depolarization approaches, exploring tools at various scales, from local to country-wide (33; 34; 35; 36; 37). Although research on depolarization is not of recent vintage (for example, 12; 13), McCoy et al. (5) observe that with a few exceptions (14; 15; 16) there are no corresponding definitions, measures and models for depolarization.

As polarization reaches pernicious levels in some places including the US (14), efforts to counter it are emerging in research (3; 5; 39; 40), media (26), and communities.

3 In the latter, one depolarizing strategy entails actively breaking homophily (41; 42) to help individuals realize that even when they have very different values they may share some interests which can be satisfied through joint decisions. In this article, we contribute to these efforts by using sociophysics modeling to explore depolarization possibilities in the case of US ahead of the 2024 elections. We ask what, if any, types of events or actions might work to counter the observed acute polarization trend, and how durable their effects can be.

Sociophysics methods (43) including statistical mechanics are particularly suitable to the study of polarization and depolarization, because they are parsimonious ways to handle the complexity of social systems phenomena without requiring the use of extensive data bases. For several examples of this approach, and how sociophysics can be applied specifically to the study of polarization, see the 2022-2023 special issue of the Entropy Journal, Statistical Physics of Opinion Formation and Social Phenomena (e.g. 11; 44; 45; 46). Together with agent-based models (47; 48) sociophysics tools help construct anticipatory scenarios of polarization under different assumptions (49) circumventing some of the serious challenges to prediction posed by complexity (50).

Kaufman et al. (11) and Diep et al. (46) have proposed a statistical mechanics model for exploring dynamics of polarization in the US political system, between Democrat- and Republican-affiliated groups in the population, with consideration of a third group, Independents. The latter is now relatively large (representing a historic highest percent at about 41% of the American voter population (51) and therefore critical in determining election outcomes: neither of the two formal parties can win without attracting a considerable number of Independent voters. The model’s results are qualitatively similar to poll outcomes in time (e.g., 52). Using this model, Kaufman et al. (11) and Diep et al. (46) generated and explored scenarios of whether leadership, also discussed by (39), and/or external events—for example, a massive natural disaster or a serious external threat, labeled “focusing event”—might bring the groups closer to each other at least for some time. They found that although leadership and focusing events can help reduce polarization, their impact is rather temporary, consistent with (5) who found in numerous case studies around the world that polarization reductions rarely last beyond about 10 years.

The voting public in the US has been for at least the last 8 years, and is currently, split down the middle between the two major parties (53), impairing the ability of governments at all levels to make necessary decisions on key topics such as the economy, the environment, energy, health care, immigration, and foreign relations, including financial assistance to other countries and global organizations. We ask here how we can overcome the current impasse resulting from the confluence of deep value differences, short political cycles which exacerbate them, novel technology effects, and homophily which impedes direct communication across party lines. Perhaps the answers lie in the confluence of a multiplicity of conditions which together push extremes toward each other (not necessarily to the middle).

We propose to use sociophysics modeling again to examine several conditions which together might depolarize the public effectively (especially important ahead of the 2024 national elections), by nudging opinion extremes toward each other to overcome homophily and enable idea exchanges in the short run, and even for longer durations. To this end, we expand the three-group polarization model of (11; 46) by adding to it a depolarization field D similar to the Blume-Capel (54; 55; 56) crystal field. By design, increasing the value of D reduces the polarization of the system, as assessed by a measure proposed in (11). We find that the depolarization field D has an additional, desirable effect: for each group, the distribution of individuals’ stances, ranging from extreme left/liberal to extreme right/conservative, is a Gaussian normal distribution. This is consistent with empirical distributions captured through polling, such as by the Pew Research Center (57) for example. The challenge remains to identify actions which together have an effect similar to the D field.

The balance of this article begins with the description of our model in

Section 2, followed by numerical results in

Section 3. We offer our final remarks and plans for future work in

Section 4.

2. Method: A Dynamic Mean-Field Model

We approach the study of depolarization in the context of US political contests. They are waged among three major US political groups historically providing candidates for president, congress, as well as state and local positions: Democrats and Republicans (which are currently highly polarized (53)), and Independents. The latter tend to lean toward, and reinforce, the number of Democrat or Republican voters in specific elections. Especially now, when they constitute a relatively large group of voters compared to the other two (51), Independents are viewed as a deciding factor in elections. For this reason, both Democrats and Republicans pain to attract them to their respective positions.

Our three-group model represents the interactions in time of voters affiliated with the two parties—Democrats and Republicans—and with the nonaffiliated Independents. The model allows testing of various interventions, which might contribute to depolarization by bringing extreme positions closer to the center.

We assume that in each of the three political groups, each individual has preferences with respect to several key political issues (11; 16). These individual preferences range between extreme left-leaning and extreme right-leaning, but more or less aligned with the positions taken be their respective parties. Democratic party- and Republican party-affiliated individuals actively interact with each other mostly within their own group, enhancing internal cohesion. Nevertheless, they also keep an eye on stances of the members of the other groups.

Within any of the Democrat and Republican groups, everyone interacts with everyone, on a complete Erdös-Renyi network. The Independents, not being formally organized into a bloc or identifiable, interact with other Independents in a much weaker fashion or not at all. In what follows, we label Democrats as group 1, Republicans as group 2, and Independents as group 3.

In each group, each individual has a stance s which reflects their preferences regarding single issues under current political debate–economics, health care, defense, immigration, climate change—or a package of such issues. The stance s varies between -1 and +1, where -1 corresponds to the democrats’ extreme progressive/left position, +1 corresponds to the republicans' extreme conservative/right position, and 0 corresponds to the middle of the road position. The Democrats and the Republicans are homophilic, meaning that individuals in a given group prefer to communicate with other individuals from the same group through intra-group couplings J, and little or not at all with anyone from the other group. Thus, the magnitude of the couplings J quantifies the cohesiveness of each group. The other groups’ mean stances influence the stances of individuals in the group under consideration through inter-group couplings K. The groups’ leaderships act on individuals’ stances through the fields H and D. The temperature T represents the effects of the context on the individual stances. For example, in the moment, different states of the economy or politics might impinge on the degree of polarization and on the extent to which leaders or other factors can reduce it.

We use the Boltzmann probability weight to compute the probability distributions for individual stances in each group. Then we compute the average stance of each group using this Boltzmann probability distribution exp(-E/T), where T is the temperature. The negative energy associated with an individual in group 1 is:

-E1 = (J1s1+ K12s2 + K13s3 + H1)s – D1s2, where s is the stance of that individual and s1, s2, s3 are the mean stances of groups 1, 2, and 3 respectively. The fields H1 and D1 represent the action of the leaders on individuals of group 1. For H1 > 0 the mean stance is pushed towards positive values, while for H1 < 0 the mean stance is pushed to negative values.

When positive, the field D1 favors depolarization through – D1s2, whose effect is to push stances s toward the center: s ~ 0; while when D1 is negative, it favors polarization: |s| ~ 1. The crystal field D, which in our context controls depolarization, was used by (47; 48; 49) to study the thermodynamics of UO2 and He3-He4 mixtures. In our implementation, the stance s is a continuous variable, whereas in the original model (47; 48; 49) the spin s = -1, 0, 1.

To write the mean-field theory for our model, we introduce the Langevin–Blume–Capel function:

where h and d stand for H/T and D/T.

We use numerical integration to evaluate this function. The average stance s at time t + 1 is assumed to be determined by preferences of the group at an earlier time t. This lag represents the time it takes to change individuals’ stances. The time t is expressed in units of the lag time. Thus, for each of the three groups respectively:

where h1 stands for H1/T, k12 stands for K12/T, d1 stands for D1/T etc. The inter-group interaction parameters K12 and K21 are not necessarily equal, as members of one group may feel cooperative toward another group, who might not reciprocate. The model includes 15 parameters: 3 j’s, 6 k’s, 3h’s and 3d’s.

We use here the polarization measure defined by (11) as the distance at any point in time between the mean stances of groups 1 and 2:

It is defined so that -1 ≤ P ≤ 1. The unpolarized case P = 0 corresponds to equal stances s1 = s2. Polarization is extreme when: P = 1 corresponding to the Republicans’ stance s2 = 1 (conservative/right) and Democrats’ stance s1 = -1 (progressive/left) or when P = -1 corresponding to Republicans’ stance s2 = -1 and Democrats’ stance s1 = 1.

The distribution of individuals of group 1 among the stances s at time t is:

gives the fraction of all individuals in group 1 who have a stance in the interval (s, s + ds) at time t. Similarly, ρ2 and ρ3 are the distribution functions for groups 2 and 3.

3. Numerical Results and Discussion

To assess the influence of the depolarization field D on the three groups’ stances, we generate four scenarios for which we use the same J and K values

4 as in our previous work (11). Thus, all results that follow are obtained for: j1 = 5; j2 = 3; j3 = 0; k12 = -4; k21 =-5; k31 = -3; k13 = 0; k23 = 0; k32 = 0; h1 = 0; h2 = 0; h3 = 0. We also fix d3 = 5 for all cases discussed below.

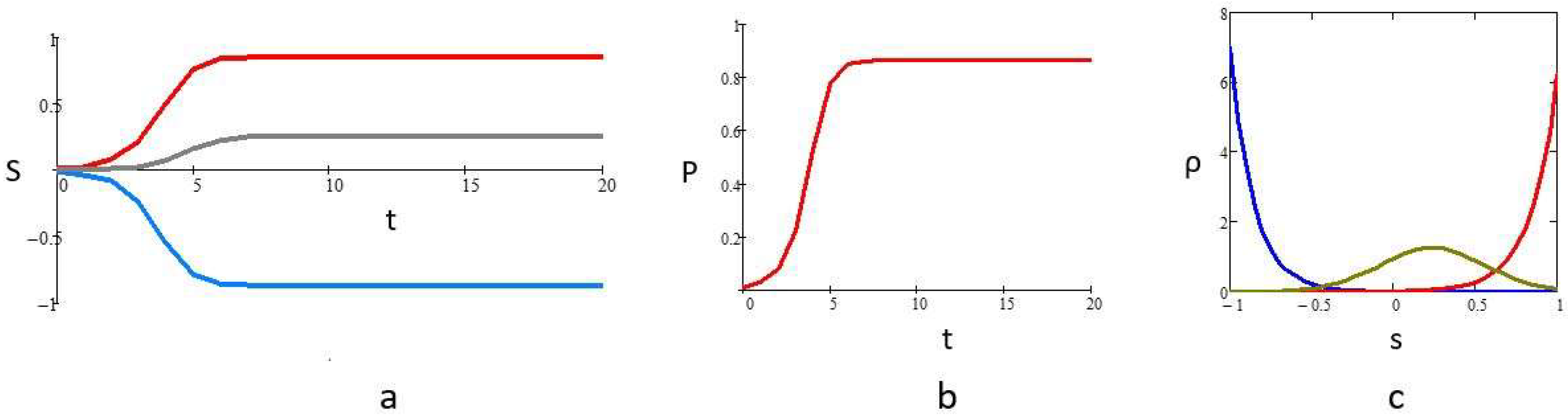

In the scenario of

Figure 1a, we set d1 = d2 = 0, meaning no depolarization action (this was the case for all scenarios we studied in (11), where d3 was also 0). As a result, the system polarizes over time. Starting at t = 0 with s1 and s2 very close to 0, in time the distance between the Democrats’ and Republicans’ mean stances increases. This can also be seen in

Figure 1b, where the polarization measure increases from 0 to about 0.8. In

Figure 1c (where t = 5), we show the stance distributions for the three groups. Since the value of d3 is positive, the distribution of stances for group 3 (Independents) is a Gaussian. In contrast, the Democrats’ and the Republicans’ distributions

depend monotonically on the stance since d2 = d2 = 0.

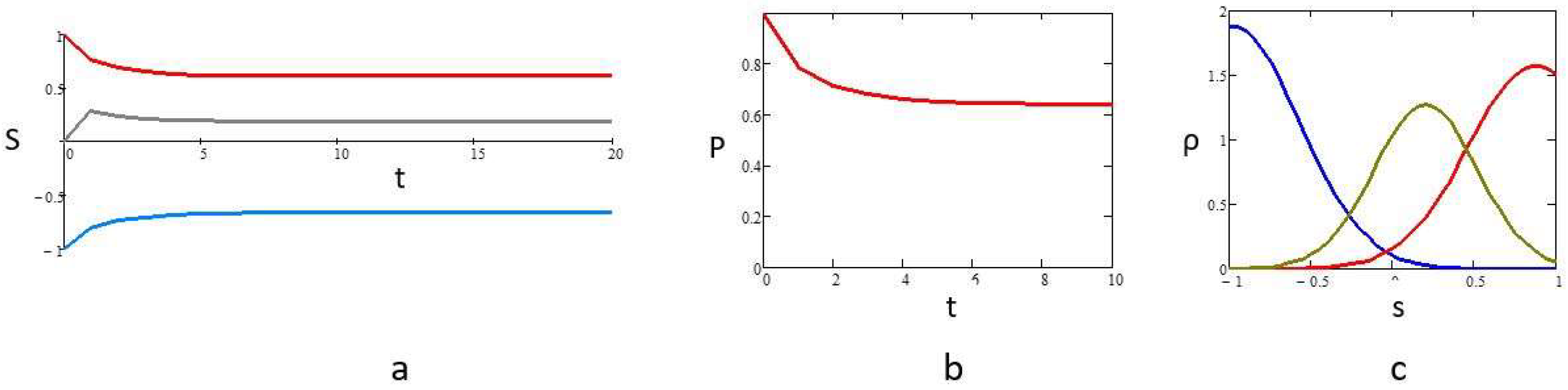

In the scenario of

Figure 2a, we set the intervention d1 = d2 = 3. Consequently, the system polarization diminishes over time. Starting at t = 0 with s1 = -1 and s2 = 1, over time the distance between the mean stances diminishes.

Figure 2b also reflects this effect: polarization P decreases from 1 to about 0.6. In

Figure 2c, for t = 5, we show that since the d values are all positive, the distributions for the three groups are all Gaussian.

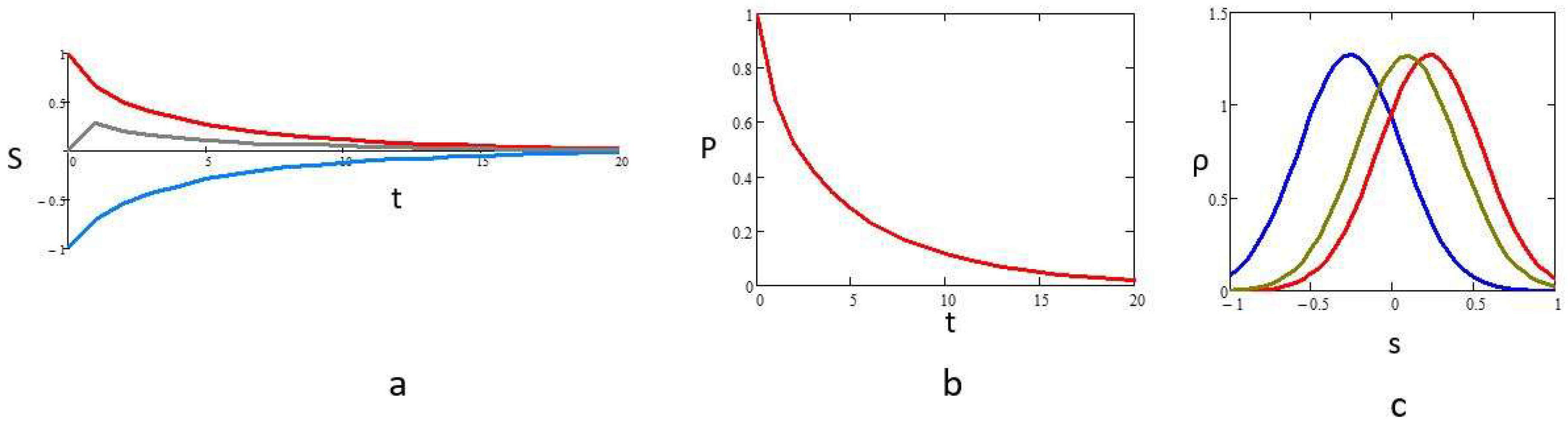

In the scenario of

Figure 3a we increase further the depolarization fields d1 = d2 = 5. The system depolarizes over time. Starting at t = 0 with s1 = -1 and s2 = 1, over time the distance between the mean stances diminishes. This is also shown in

Figure 3b where the polarization decreases from 1 at t = 0 to about 0 at t = 20. In

Figure 3c we show the stance distributions for the three groups. Since the d’s are positive, the distributions are all Gaussian.

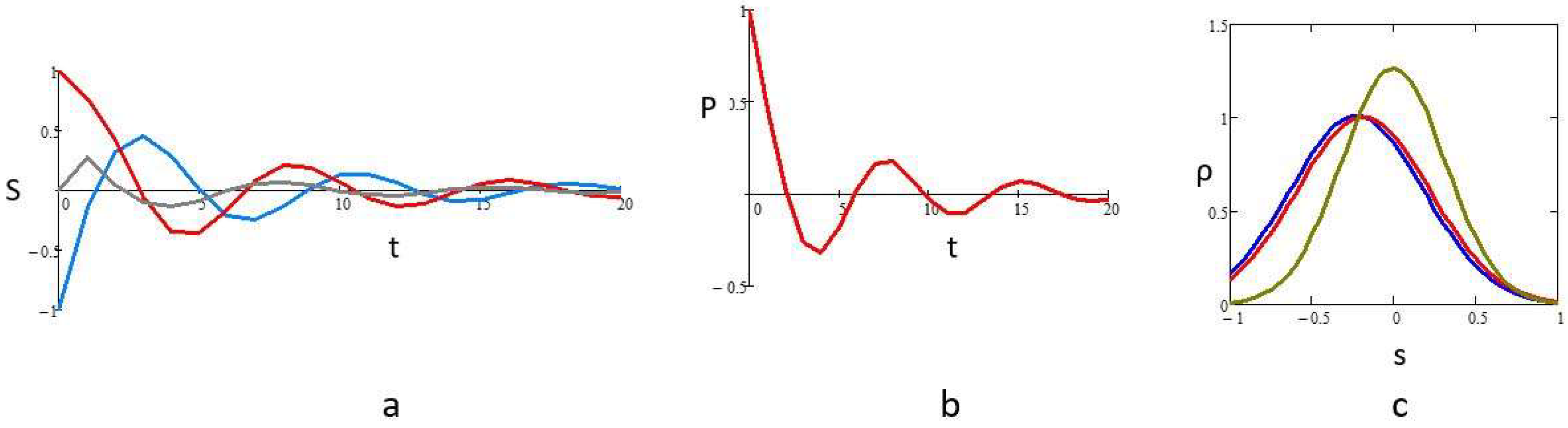

Finally, we consider a fourth scenario which in (11) exhibited time oscillations of the three stances: j1 = 5; j2 = 3; j3 = 0; k12 = 4; k21 =- 5; k31 = -3; k13 = 0; k23 = 0; k32 = 0; h1 = 0; h2 = 0; h3 = 0. Again, we add depolarization fields: d1 = d2 = 3; d3= 5. Now in

Figure 4a, the three groups’ stances exhibit damped oscillations over time. The system depolarizes in time and the polarization P also exhibits damped oscillations (

Figure 4b). The distributions of stances for the three groups, shown in

Figure 4c (t = 5), are Gaussian because the depolarization field values are positive for each group.

The increase in value of the depolarization fields of groups 1 and 2 reduces polarization over time. In the oscillatory case, which occurs when k12 and k21 have different signs, the depolarization field dampens those oscillations.

We have shown through these scenarios that when a positive depolarization field is added, the distribution of stances becomes Gaussian. It means that it is maximized at a stance within the interval (-1, 1), signifying a non-extreme stance. When the groups stances are non-extreme, there exists the possibility of breaking out of the extreme polarization.

4. Concluding Remarks

Using the case of the USA political system where three polarized groups—Democrats, Republicans and Independents—interact, we explored scenarios of depolarization under the effect of intervention. We found that when a depolarization field D is added, the polarization decreases over time. If the D field is sufficiently strong, the polarization decreases to zero.

In practice, the field D can result from the actions of the groups’ leadership, and/or of events which can refocus all groups on concerted actions in the face of some external threats. Examples of both have occurred in the past in the United States, such as during World War II, the Vietnam war, and after the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center in New York City, and elsewhere. The field D can also be the result of numerous local grassroots initiatives (also proposed by (26) as an antidote to polarization) currently occurring in the United States. They may add up to country-wide depolarization. Several examples can be found at (40). These initiatives are akin to massively parallel intervention—a multiplicity of independent, locally driven actions—proposed by (58) and (3)—which together, when reaching a critical mass, can have a depolarizing effect among the political groups at least in the short run. Sustaining depolarization in the longer run remains a challenge. As (5) observed in cases around the world, in general repolarization tends to resume after about 10 years. Since in our model the extent of depolarization depended on the strength of the intervention, we plan to explore further what factors might extend the duration of depolarized states.

This model includes, besides the single site field D, a field H. While D promotes compromise stance s ~ 0, the H field promotes extreme positions: |s| ~ 1. This could be the result of influencers and/or media activities. We plan to further explore the group dynamics in the 15-dimensional parameter space. For example, we intend to elucidate the influence of the D field on the chaotic dynamics that we observed in the 3-group model with competing K interactions. We also plan to study the model with intra-group short-range interactions by means of Monte-Carlo simulations. We will extend our study, to account for different levels of randomness, by varying the temperature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Kaufman, S.Kaufman & H.T.Diep; methodology, M.Kaufman; software, M.Kaufman; validation, M.Kaufman; formal analysis, M.Kaufman & S.Kaufman; data curation, S.Kaufman; writing—original draft preparation, M.Kaufman & S.Kaufman; writing—review and editing, S.Kaufman & H.T.Diep;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Please turn to the CrediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baldassarri, D.; Gelman, A. Partisans without constraint: Political polarization and trends in American public opinion. American Journal of Sociology 2008, 114, 408–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramson, A.; Grim, P.; Singer, D.J.; Berger, W.J.; Sack, G.; Fisher, S.; Holman, B. Understanding polarization: Meanings, measures, and model evaluation. Philosophy of science 2017, 84, 115–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, G.; Burgess, H.; Kaufman, S. Applying conflict resolution insights to the hyper-polarized, society-wide conflicts threatening liberal democracies. Conflict Resolution Quarterly (CRQ) 2022, 39, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess G.; Burgess H. Challenging “bad-faith” actors who seek to amplify and exploit our conflicts. Beyond Intractability. 2021 Retrieved from https://www.beyondintractability.org/frontiers/bad-faith-actors on 15 Aug 2023.

- McCoy, J.; Press, B.; Somer, M.; Tuncel, O. Reducing Pernicious Polarization: A Comparative Historical Analysis of Depolarization, CEIP: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. 2022 Retrieved from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2392500/reducing-pernicious-polarization/3413931/ on 15 Aug 2023. CID: 20.500.12592/jxnrmh.

- McCoy J.; Somer M. eds. Polarization and democracy: a Janus-faced relationship with pernicious consequences. American Behavioral Scientist 2018, 62.

- McCoy, J.; Rahman, T.; Somer, M. Polarization and the global crisis of democracy: Common patterns, dynamics, and pernicious consequences for democratic polities. American Behavioral Scientist 2018, 62, 16–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somer, M.; McCoy, J. Déjà vu? Polarization and endangered democracies in the 21st century. American Behavioral Scientist 2018, 62, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, L.; Gersbach, H. The great divide: drivers of polarization in the US public. EPJ data science 2020, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, K. Far more Americans see ‘very strong’ partisan conflicts now than in the last two presidential election years. Pew Research Center 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, M.; Kaufman, S.; Diep, H. T. , Statistical Mechanics of Political Polarization. Entropy 2022, 24, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinokur, A.; Burnstein, E. Depolarization of attitudes in groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1978, 36, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, M.; Judd, C.M. Group polarization and repeated attitude expressions: A new take on an old topic. European review of social psychology 1996, 7, 173–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, J.; Somer, M. Toward a theory of pernicious polarization and how it harms democracies: Comparative evidence and possible remedies. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 2019, 681, 234–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somer, M.; McCoy, J. Transformations through polarizations and global threats to democracy. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 2019, 681, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobkowicz, P. Social Depolarization and Diversity of Opinions—Unified ABM Framework. Entropy 2023, 25, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRS Reports. Membership of the 118 Congress: A Profile. October, 2023. Retreived fr https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47470 on Oct. 10 2023.

- Hundreds of Biden Nominees Stuck In Senate Limbo Amid G.O.P. Blockade New York Times January 8, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/08/us/politics/biden-nominees-senate-confirmation.html on Oct. 10 2023.

- Walter, J.; Helmore, E. Joe Manching hails expansive bill he finally agrees to as “great for America.” The Guardian July 31 2022. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/jul/31/joe-manchin-hails-deal-inflation-reduction-act on Oct. 10 2023.

- Dormido, H.; Blanco, A. How each member voted on House stopgap bill to avoid shutdown. Washington Post September 29, 2023. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/interactive/2023/house-vote-government-shutdown/ on Oct. 10, 2023.

- Sonnefeld, J. The Budget Deal is a Tragedy for Ukraine. TIME, October 2, 2023. Retrieved from https://time.com/6319570/ukraine-u-s-aid-republicans/ on Oct.10, 2023.

- Fung, K. Republicans are blocking theor own calls for Israeli Aid. Newsweek October 10, 2023. Retrieved from https://www.newsweek.com/republicans-blocking-calls-israel-aid-no-house-speaker-1833399 on Oct. 10 2023.

- Newport, F. Update: Partisan Gaps Expand Most on Government Power, Climate, Gallup August 2023 Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/509129/update-partisan-gaps-expand-government-power-climate.aspx?version=print&thank-you-subscription-form=1 on 15 Aug. 2023.

- Doherty, C.; Kiley, J.; Johnson, B. The partisan divide on political values grows even wider. Pew Research Center. Pew Research 2017.

- Schaeffer, K. Far more Americans see ‘very strong’ partisan conflicts now than in the last two presidential election years. Pew Research Center 2020.

- Fukuyama, F. Paths to depolarization. Persuasion 2022. Retrieved from https://www.persuasion.community/p/fukuyama-paths-to-depolarization on 16 Aug. 2023.

- Klein E, Robison J. Like, post, and distrust? How social media use affects trust in government. Political Communication. 2020, 37, 46–64.

- Rekker, R. The nature and origins of political polarization over science. Public Understanding of Science 2021, 30, 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubin, E.; von Sikorski, C. The role of (social) media in political polarization: a systematic review. Annals of the International Communication Association 2021, 45, 188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandekar, P.; Goel, A.; Lee, D.T. Biased assimilation, homophily, and the dynamics of polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 2013, 110, 5791–5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doise, W. Intergroup relations and polarization of individual and collective judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1969, 12, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, D.; Cooper, J. Attitude polarization: Effects of group membership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984, 46, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuesser A, Johnston R, Bodet MA. The Dynamics of Polarization and Depolarization: Methodological Considerations and European Evidence. APSA Annual Meeting Paper 2014.

- van der Linden, S.; Leiserowitz, A.; Maibach, E.W. Communicating the scientific consensus on human-caused climate change is an effective and depolarizing public engagement strategy: Experimental evidence from a large national replication study. Available at SSRN 2733956. 2016 Feb 17.

- Liu, R. : Wang L.; Jia C.; Vosoughi S. Political depolarization of news articles using attribute-aware word embeddings. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 2021, 15, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojer J, Starnini M, Pastor-Satorras R. Modeling Explosive Opinion Depolarization in Interdependent Topics. Physical Review Letters 2023, 130, 207401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sude, D.J.; Knobloch-Westerwick, S. The Role of Media in Political Polarization| When We Have to Get Along: Depolarizing Impacts of Cross-Cutting Social Media. International Journal of Communication 2023, 17, 23. [Google Scholar]

- McCoy, J.; Somer, M. Toward a theory of pernicious polarization and how it harms democracies: Comparative evidence and possible remedies. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 2019, 681, 234–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, J.; Somer, M. Overcoming polarization. Journal of Democracy 2021, 32, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Hyper-Polarization Crisis: A Conflict Resolution Challenge, Retrieved from Beyond Intractability, https://www.beyondintractability.org/ on 26 August, 2023.

- Diamond, M.J.; Lobitz, W.C. When familiarity breeds respect: The effects of an experimental depolarization program on police and student attitudes toward each other. Journal of Social Issues. 1973, 29, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currin, C.B.; Vera, S.V.; Khaledi-Nasab, A. Depolarization of echo chambers by random dynamical nudge. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galam, S. Galam S. What is sociophysics about?. In Sociophysics 2012 (3-19). Springer, Boston, MA.

- Galam, S. Unanimity, Coexistence, and Rigidity: Three Sides of Polarization. Entropy 2023, 25, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galam, S. Opinion dynamics and unifying principles: A global unifying frame. Entropy 2022, 24, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, H. T.; Kaufman, M.; Kaufman, S. ; An Agent-Based Statistical Physics Model for Political Polarization: A Monte Carlo Study. Entropy 2023, 25, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, J. M. Agent-based computational models and generative social science. Complexity 1999, 4, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempert, R. Agent-based modeling as organizational and public policy simulators. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99 (Suppl. S3), 7195–7196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, M.; Diep, H.T.; Kaufman, S. Sociophysics of intractable conflicts: three-group dynamics. Physica A 2019, 517, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M.; Torrens, P. M. Modelling complexity: the limits to prediction. Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography 2001.

- Jones, J. U. S Party Preferences Evenly Split in 2022 after Shift to GOP. Gallup. January 12 2023. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/467897/party-preferences-evenly-split-2022-shift-gop.aspx on Oct. 10, 2023.

- Doherty, C.; Kiley, J.; Johnson, B. The partisan divide on political values grows even wider. Pew Research Center. Pew Research 2017.

- Gallup party affiliation trend since 2004. https://news.gallup.com/poll/15370/party-affiliation.aspx (last visited on July 22, 2022).

- Blume, M. Theory of the First-Order Magnetic Phase Change in U O 2. Physical Review 1966, 141, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capel, H.W. On the possibility of first-order phase transitions in Ising systems of triplet ions with zero-field splitting. Physica 1966, 32, 966–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, M.; Emery, V.J.; Griffiths, R.B. Ising Model for the λ Transition and Phase Separation in He3-He4 Mixtures, Phys. Rev. A 1971, 4, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, C.; Kiley, J.; Johnson, B. The Partisan Divide on Political Values Grows Even Wider. Pew Research Center. 2017. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2017/10/05/the-partisan-divide-on-political-values-grows-evenwider/ on May 15, 2022.

- Burgess, G., & Burgess, H. 2020. Massively parallel peacebuilding Beyond Intractability. Retrieved from https://www.beyondintractability.org/frontiers/mpp-paper 12 Aug 2023.

| 1 |

The references included here are illustrative of the numerous articles addressing the increasing polarization around the world. |

| 2 |

For example, after long months of a deep split in the Israeli polity, accompanied by numerous weekly demonstrations, the sudden violent events of October 2023 played the role of a focusing event: differences were mostly set aside, and the entire society concentrated on mutual help and a unified response. |

| 3 |

See (40) for several examples of depolarizing initiatives at the community and organization levels. |

| 4 |

These values were selected based on a qualitative analysis to replicate Doherty et al. (20r17) poll results on Democrat and Republican increasingly polarized stances. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).