Submitted:

18 October 2023

Posted:

19 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Database Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Type of studies: This study only includes systematic reviews (with or without meta-analysis) that analysed randomised controlled trials due to their methodological quality. Published from 2015 to 2022. Only titles written in English and Spanish were considered.

-

Type of participants:

- ○

- Subjects diagnosed with an ischaemich or haemorrahagic stroke.

- ○

- Adults, over 18 years of age.

- ○

- Acute, sub-acute or chronic stroke.

- Type of intervention: we included studies in which the interventions involved tDCS, whether administered alone or in combination with another form of treatment and compared to another form of physical therapy, or placebo. We excluded papers that did not define interventions or multi-therapies and also any pharmacological treatment (e.g., botulinum toxin).

- Type of outcome measures: studies quantitatively assessing gait pattern (three-dimensional instrumental analysis systems), gait speed, functional mobility, endurance, motor function and muscle strength.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Methodological Assessment and Evaluation of the Quality of Evidence

3. Results

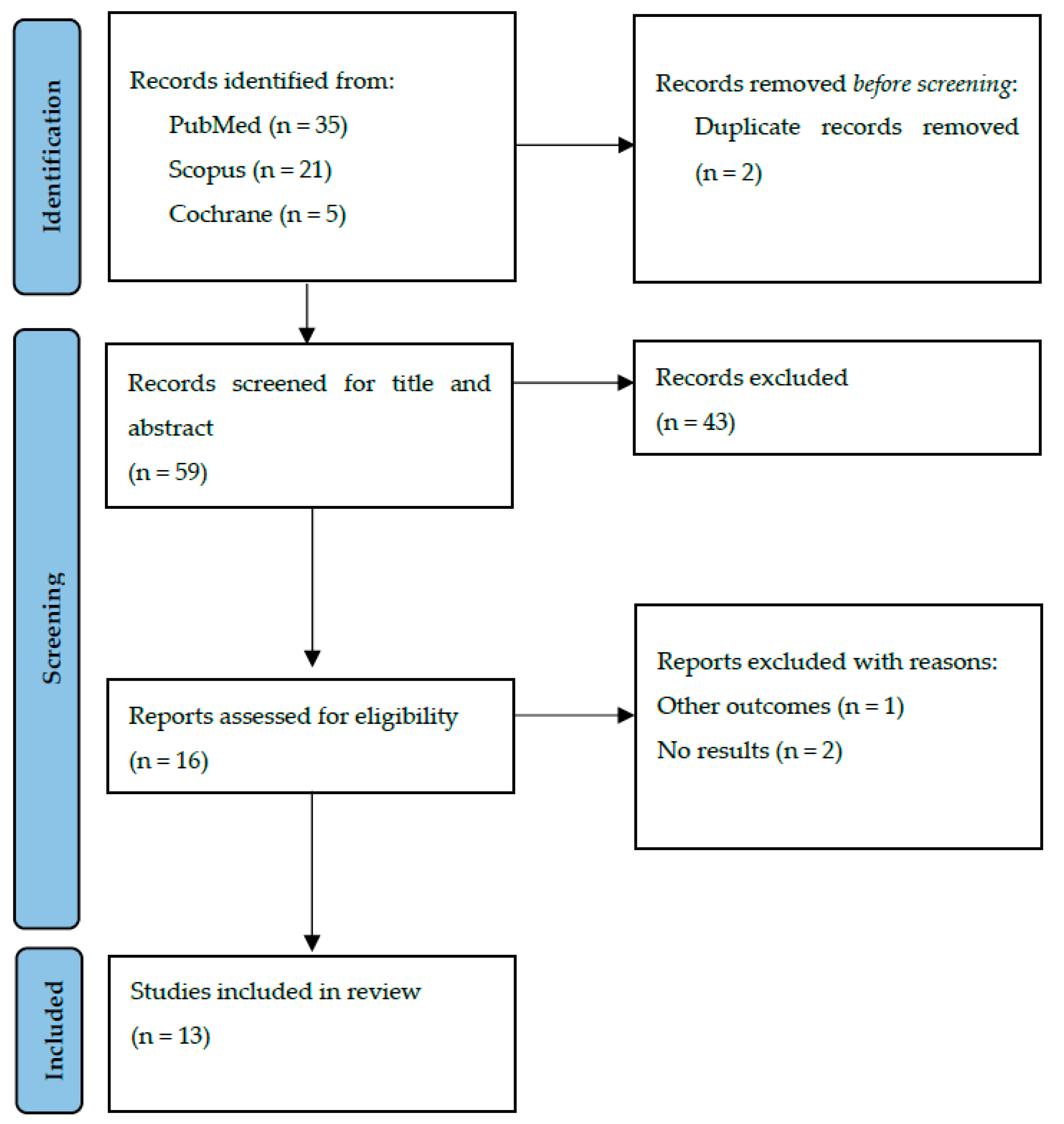

3.1. Selection of Studies

3.2. Methodological Quality Assessment

3.3. Assessing the Quality of Evidence

3.4. Summary of Results

3.4.1. Effect of tDCS in Combination with Physiotherapy on Spatiotemporal Parameters.

3.4.2. Effect of tDCS in Combination with Physiotherapy on Functional Mobility

3.4.3. Effect of tDCS in Combination with Physiotherapy on Endurance

3.4.4. Effect of tDCS in Combination with placebo On Motor Function

3.4.5. Effect of tDCS in Combination with Physiotherapy on Muscle strength

3.4.6. Effect of tDCS in Combination with Placebo on Lower Limb Function

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wonsetler, E.C.; Bowden, M.G. A Systematic Review of Mechanisms of Gait Speed Change Post-Stroke. Part 1: Spatiotemporal Parameters and Asymmetry Ratios. Top Stroke Rehabil 2017, 24, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghai, S.; Ghai, I. Effects of (Music-Based) Rhythmic Auditory Cueing Training on Gait and Posture Post-Stroke: A Systematic Review & Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alingh, J.F.; Groen, B.E.; van Asseldonk, E.H.F.; Geurts, A.C.H.; Weerdesteyn, V. Effectiveness of Rehabilitation Interventions to Improve Paretic Propulsion in Individuals with Stroke – A Systematic Review. Clinical Biomechanics 2020, 71, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Fan, J.; Yang, J.; He, C.; Li, S. Effects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Walking Ability after Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2018, 36, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winstein, C.J.; Stein, J.; Arena, R.; Bates, B.; Cherney, L.R.; Cramer, S.C.; Deruyter, F.; Eng, J.J.; Fisher, B.; Harvey, R.L.; et al. Guidelines for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association; 2016; Vol. 47, ISBN 0000000000000. [Google Scholar]

- Michener, G.R.; Beecher, M.D.B.; Johnson, V.R.; Brooke, M. de L. Stimulation of the Cerebral Cortex in the Intact Human Subject. Nature 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lefaucheur, J.P.; Antal, A.; Ayache, S.S.; Benninger, D.H.; Brunelin, J.; Cogiamanian, F.; Cotelli, M.; De Ridder, D.; Ferrucci, R.; Langguth, B.; et al. Evidence-Based Guidelines on the Therapeutic Use of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (TDCS). Clinical Neurophysiology 2017, 128, 56–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanía, R.; Nitsche, M.A.; Ruff, C.C. Studying and Modifying Brain Function with Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation. Nat Neurosci 2018, 21, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, A.; Luber, B.; Brem, A.K.; Bikson, M.; Brunoni, A.R.; Cohen Kadosh, R.; Dubljević, V.; Fecteau, S.; Ferreri, F.; Flöel, A.; et al. Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation and Neuroenhancement. Clin Neurophysiol Pract 2022, 7, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Farahani, F.; Bikson, M.; Parra, L.C. Weak DCS Causes a Relatively Strong Cumulative Boost of Synaptic Plasticity with Spaced Learning. Brain Stimul 2022, 15, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesikburun, S. Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation in Rehabilitation. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil 2022, 68, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsner, B.; Kugler, J.; Pohl, M.; Mehrholz, J. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (TDCS) for Improving Activities of Daily Living, and Physical and Cognitive Functioning, in People after Stroke (Review). Cochrane Library 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paz, R.H.; Serrano-Muñoz, D.; Pérez-Nombela, S.; Bravo-Esteban, E.; Avendaño-Coy, J.; Gómez-Soriano, J. Combining Transcranial Direct-Current Stimulation with Gait Training in Patients with Neurological Disorders: A Systematic Review. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2019, 16, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, P.G.; Salazar, A.P. da S.; Stein, C.; Marchese, R.R.; Lukrafka, J.L.; Plentz, R.D.M.; Pagnussat, A.S. Noninvasive Brain Stimulation Combined with Other Therapies Improves Gait Speed after Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Top Stroke Rehabil 2019, 26, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-López, V.; Molina-Rueda, F.; Jiménez-Jiménez, S.; Alguacil-Diego, I.M.; Carratalá Tejada, M. Effect of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Combined with Rehabilitation on Gait Pattern, Balance, and Functionality in Stroke Patients: A Systematic Review. diagnostics 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Fan, J.; Yang, J.; He, C.; Li, S. Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on Walking and Balance Function after Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis; 2018; Vol. 97, ISBN 0000000000000. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, Y.C.; Lai, C.H.; Liao, C. De; Huang, S.W.; Liou, T.H.; Chen, H.C. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of Lower Limb Motor Function in Patients with Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin Rehabil 2019, 33, 1102–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tien, H.H.; Liu, W.Y.; Chen, Y.L.; Wu, Y.C.; Lien, H.Y. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation for Improving Ambulation after Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 2020, 43, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.V.; Lopes, J.B.P.; Duarte, N.A.C.; Castro, C.R.A. de P.; Grecco, L.A.C.; Oliveira, C.S. TDCS and Motor Training in Individuals with Central Nervous System Disease: A Systematic Review. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2020, 24, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsutake, T.; Imura, T.; Hori, T.; Sakamoto, M.; Tanaka, R. Effects of Combining Online Anodal Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation and Gait Training in Stroke Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Hum Neurosci 2021, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Meng, S.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, R.; Xu, P.; Yuan, E.; Lian, T. The Effects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Balance and Gait in Stroke Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Neurol 2021, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldema, J.; Gharabaghi, A. Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation for Improving Gait, Balance, and Lower Limbs Motor Function in Stroke. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corominas-Teruel, X.; Mozo, R.M.S.S.; Simó, M.F.; Colomina Fosch, M.T.; Valero-Cabré, A. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation for Gait Recovery Following Stroke: A Systematic Review of Current Literature and Beyond. Front Neurol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressi, F.; Cinnera, A.M.; Morone, G.; Campagnola, B.; Cricenti, L.; Santacaterina, F.; Miccinilli, S.; Zollo, L.; Paolucci, S.; Di Lazzaro, V.; et al. Combining Robot-Assisted Gait Training and Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation in Chronic Stroke Patients: A Systematic Review. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 795788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüdemann-Podubecká, J.; Bösl, K.; Nowak, D.A. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Motor Recovery of the Upper Limb after Stroke. Prog Brain Res 2015, 218, 281–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The cochrane collaboration Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer Program] 2020.

- Higgins, J. Manual Cochrane de Revisiones Sistemáticas de Intervenciones, Versión 5.1. 0. Manual Cochrane de Revisiones Sistemáticas de Intervenciones, versión 5.1.0, 2012; 1–639. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara, W.; Sasaki, S.; Yamamoto, R.; Kawakami, M.; Kaneko, F. The Effects of Robot-Assisted Gait Training Combined with Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation on Lower Limb Function in Patients with Stroke and Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Hum Neurosci 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, N. Assessment of Cortical Reorganisation for Hand Function after Stroke. J Physiol 2011, 589, 5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murase, N.; Duque, J.; Mazzocchio, R.; Cohen, L.G. Influence of Interhemispheric Interactions on Motor Function in Chronic Stroke. Ann Neurol 2004, 55, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, M.N.; Stinear, C.M. TMS Measures of Motor Cortex Function after Stroke: A Meta-Analysis. Brain Stimul 2017, 10, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatem, S.M.; Saussez, G.; della Faille, M.; Prist, V.; Zhang, X.; Dispa, D.; Bleyenheuft, Y. Rehabilitation of Motor Function after Stroke: A Multiple Systematic Review Focused on Techniques to Stimulate Upper Extremity Recovery. Front Hum Neurosci 2016, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, A.; Farmer, S.E.; Brady, M.C.; Langhorne, P.; Mead, G.E.; Mehrholz, J.; van Wijck, F. Interventions for Improving Upper Limb Function after Stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, S.M.; Ferreira, J.J. de A.; Rufino, T.S.; Medeiros, G.; Brito, J.D.; da Silva, M.A.; Moreira, R. de N. Effects of Different Montages of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on the Risk of Falls and Lower Limb Function after Stroke. Neurol Res 2017, 39, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, A.R.; Smith, G. V.; Forrester, L.; Whitall, J.; Macko, R.F.; Hauser, T.K.; Goldberg, A.P.; Hanley, D.F. Comparing Brain Activation Associated with Isolated Upper and Lower Limb Movement across Corresponding Joints. Hum Brain Mapp 2002, 17, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, D.T.; Norton, J.A.; Roy, F.D.; Gorassini, M.A. Effects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on the Excitability of the Leg Motor Cortex. Exp Brain Res 2007, 182, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halakoo, S.; Ehsani, F.; Hosnian, M.; Zoghi, M.; Jaberzadeh, S. The Comparative Effects of Unilateral and Bilateral Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Motor Learning and Motor Performance: A Systematic Review of Literature and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2020, 72, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PubMed Search |

|---|

| 2,(((stroke) AND (NIBS)) OR (tDCS)) AND (gait),Most Recent,"Meta-Analysis, Systematic Review, from 2016 - 2022","((((""stroke""[MeSH Terms] OR ""stroke""[All Fields] OR ""strokes""[All Fields] OR ""stroke s""[All Fields]) AND ""NIBS""[All Fields]) OR (""transcranial direct current stimulation""[MeSH Terms] OR (""transcranial""[All Fields] AND ""direct""[All Fields] AND ""current""[All Fields] AND ""stimulation""[All Fields]) OR ""transcranial direct current stimulation""[All Fields] OR ""tdcs""[All Fields])) AND (""gait""[MeSH Terms] OR ""gait""[All Fields])) AND ((meta-analysis[Filter] OR systematicreview[Filter]) AND (2016:2022[pdat]))" |

| Cochrane Search |

| "transcranial direct current stimulation":ti,ab,kw AND "stroke":ti,ab,kw |

| Scopus Search |

| stroke AND tdcs AND gait AND PUBYEAR > 2014 AND PUBYEAR < 2023 AND ( LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE , "re")) AND (LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA, "HEAL")) |

| AMSTAR Checklist | Li et al. | De Paz et al. | Vaz et al. | Elsner et al. | Tien et al. | Santos et al. | Mitsutake et al. | Dong et al. | Navarro-López et al. | Veldema et al. | Corominas-Teruel et al. | Bressi et al. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y |

| 3 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 4 | PY | PY | PY | Y | N | PY | PY | PY | Y | PY | PY | PY |

| 5 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 6 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 7 | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | PY | N | N | N |

| 8 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 9 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 10 | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 11 | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | NA | Y | NA | NA |

| 12 | Y | NA | N | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | NA | Y | NA | NA |

| 13 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 14 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 15 | N | NA | N | Y | N | NA | N | N | NA | N | NA | NA |

| 16 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Overall assessment | Critically low | Low | Critically low | High | Critically low | Low | Critically low | Critically low | Low | Critically low | Low | Low |

| Review | Data assessed as up to date | Population | Interventions | Comparison interventions | Outcomes for which data were reported | Review limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. (2018) [4] | April 2017 (English) | Post-stroke patients over 18 years of age |

tDCS:

|

Simulated treatment (complementary robot-assisted treatments, task-related training, robotic orthoses and conventional rehabilitation) |

|

|

| De Paz et al. (2019) [13] | 2018 | Patients diagnosed with a pathology of the central nervous system | tDCS applying anode in ipsilateral (affected) hemisphere (n=4). |

|

|

|

| Vaz et al. (2019) [14] | December 2018 | Subjects who have suffered an acute/subacute (less than six months) or chronic (more than six months) stroke. |

tDCS:

|

|

|

|

| Elsner et al. (2020) [12] | January 2019 (all languages) | Post-stroke patients over 18 years of age |

tDCS:

|

|

|

|

| Tien et al. (2020) [18] | January 2019 | Post-stroke patients over 18 years of age |

tDCS:

|

Simulated treatment of tDCS. |

|

|

| Santos et al. (2020) [19] | October 2018 | Children, adolescents, adults and older people who do not have a progressive central nervous system disease. | tDCS in combination with motor training. | Simulated treatment in combination with motor training. |

|

|

| Matsutake et al. (2021) [20] | 19 March 2021 | Patients diagnosed with haemorrhagic or ischaemic stroke with unilateral hemiplegia. They can walk without support and can maintain their weight and balance. |

tDCS:

|

Simulated tDCS treatment in combination with robot-assisted gait therapy or neuromuscular stimulation. |

|

|

| Dong et al. (2021) [21] | August 2020 | Patients who have been diagnosed with a stroke. | tDCS applying anode in ipsilateral hemisphere. | Simulated treatment of tDCS. |

|

|

| Navarro-López et al. (2021) [15] | March 2020 | Patients who have been diagnosed with a stroke. |

tDCS:

|

Simulated treatment of tDCS. |

|

|

| Veldema et al. (2022) [22] | 31 March 2021 | Patients diagnosed with stroke |

NIBS:

|

Simulated stimulation | Lower limb functionality (combining outcome measures of balance, gait and motor function). |

|

| Corominas-Teruel et al. (2022) [23] | 7 February 2022 | Patients who have suffered a stroke aged 18 years or older | tDCS. | Simulated stimulation alone or in combination with other therapies. |

|

|

| Bressi et al. (2022) [24] | 15 March 2021 | Patients over 18 years of age who have suffered a stroke in a chronic process (>6 months). | tDCS in combination with gait-assisted robot | Simulated stimulation |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).