1. Introduction

An ovarian cyst is a common condition with a wide range of etiologies, particularly among premenopausal women [

1]. The majority of these cysts are asymptomatic and resolve spontaneously; however, those measuring over 10 cm are considered large [

2].

The presenting symptomatology of ovarian cysts can be perceived as subtle and vague concerns, for example, gradual undefined pelvic pain, early satiety, bloating, enlarging abdomen, and irregular menstrual history; however, addressing these concerns is an important step for primary physicians to maintain trusting relationships in patients care [

1,

3]. Large ovarian cysts, with the most common types being benign ovarian serous cystadenomas, arising from the ovarian epithelium are rare due to more effective multi-screening methods [

4,

5].

However, large ovarian cyst can lead to torsion and present as abdominal pain in over 58% of cases [

4,

6].

This report will discuss a unique case of a large ovarian cyst that developed over 6 years, which led to the sequela of acute emergency surgery for ovarian torsion. Additionally, this case will explore the cause and immediate management of this patient—including from the patient’s firsthand perspective. Further, we explore the clinical significance of the three-strike presentation rule in primary care, which can highlight early recognition and effective management of seemingly vague symptoms [

7].

The importance of considering the differentials of acute abdomen in women of reproductive age, obtaining accurate imaging, and considering the appropriate surgical techniques may prevent adverse consequences, such as the loss of fertility, complications from rupture and hemorrhage from exploratory laparotomy, or even death [

8,

9,

10].

2. Case Presentation

The patient, a 20-year-old Hispanic nulliparous female, presented to the emergency department one hour after the onset of a severe “stabbing” pain in the lower left quadrant and non-radiating pain in her abdomen after feeling an urge to defecate. Further, she had several episodes of non-bloody, non-bilious emesis. She was afebrile on admission, with no chest pain, no acute shortness of breath, or any urinary frequency or pain.

From gynecological anamnesis, the patient was a virgin, with first menarche at 11 years old, a history of oligomenorrhea (2 months apart), and her last menstrual period was 29 days before presentation. There was no vaginal discharge or bleeding on admission. The patient had a current history of breathlessness which had been attributed to mild asthma managed with a prescribed inhaler, used occasionally. There was a surgical history of an appendectomy in 2006 with an unremarkable recovery. The patient had no allergies, was a non-smoker, no illicit substance use, and drank alcohol socially. There were no relevant family history for ovarian malignancies or BRCA-1 and 2 mutations. The patient worked in the childcare profession whilst attending her second year of university studies.

Upon examination, the patient appeared to be obese, well-developed, anxious, and cooperative. She was not able to tolerate a speculum examination due to the pain. There was no pulsatile abdominal mass, guarding of the abdomen, nor any generalized and/or rebound tenderness or rigidity. The lower left quadrant of the patient’s abdomen was tender with mild distention and normal bowel sounds were heard. An elevated blood pressure on admission (145/89) was noted. The urinalysis was unremarkable. Blood analysis showed hypochromic, microcytic anemia (10.3 g/dL) with +1 anisocytosis (generally associated with iron deficiency anemia [

11]), and mild elevated chloride (109) and elevated glucose (109) levels.

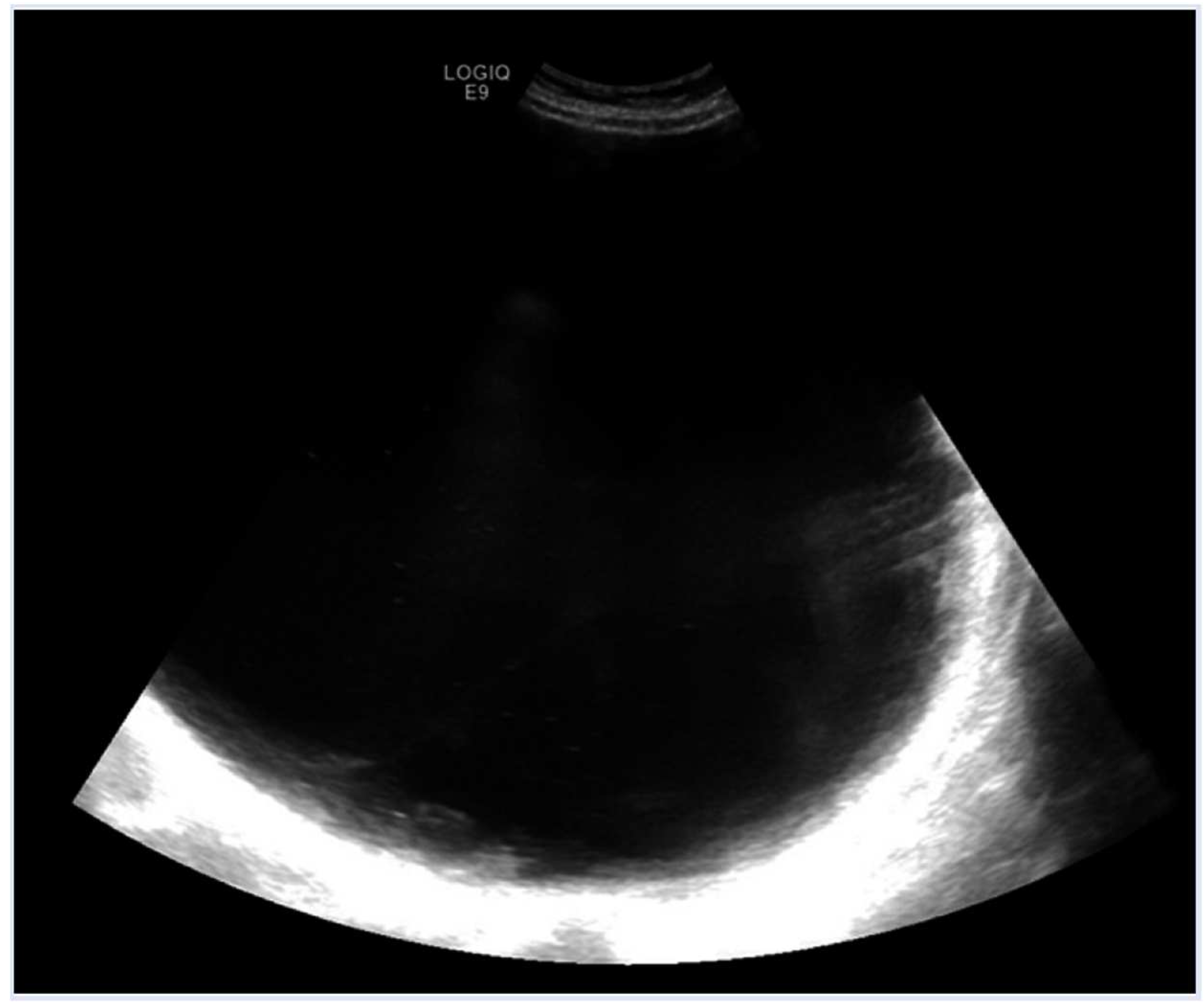

A pelvic ultrasound reported a normal uterus with no endometrial abnormalities, and the right ovary appeared normal. The left ovary was not visualized (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Additionally, the origin of the large cystic structure was unknown. An abdominal/pelvic

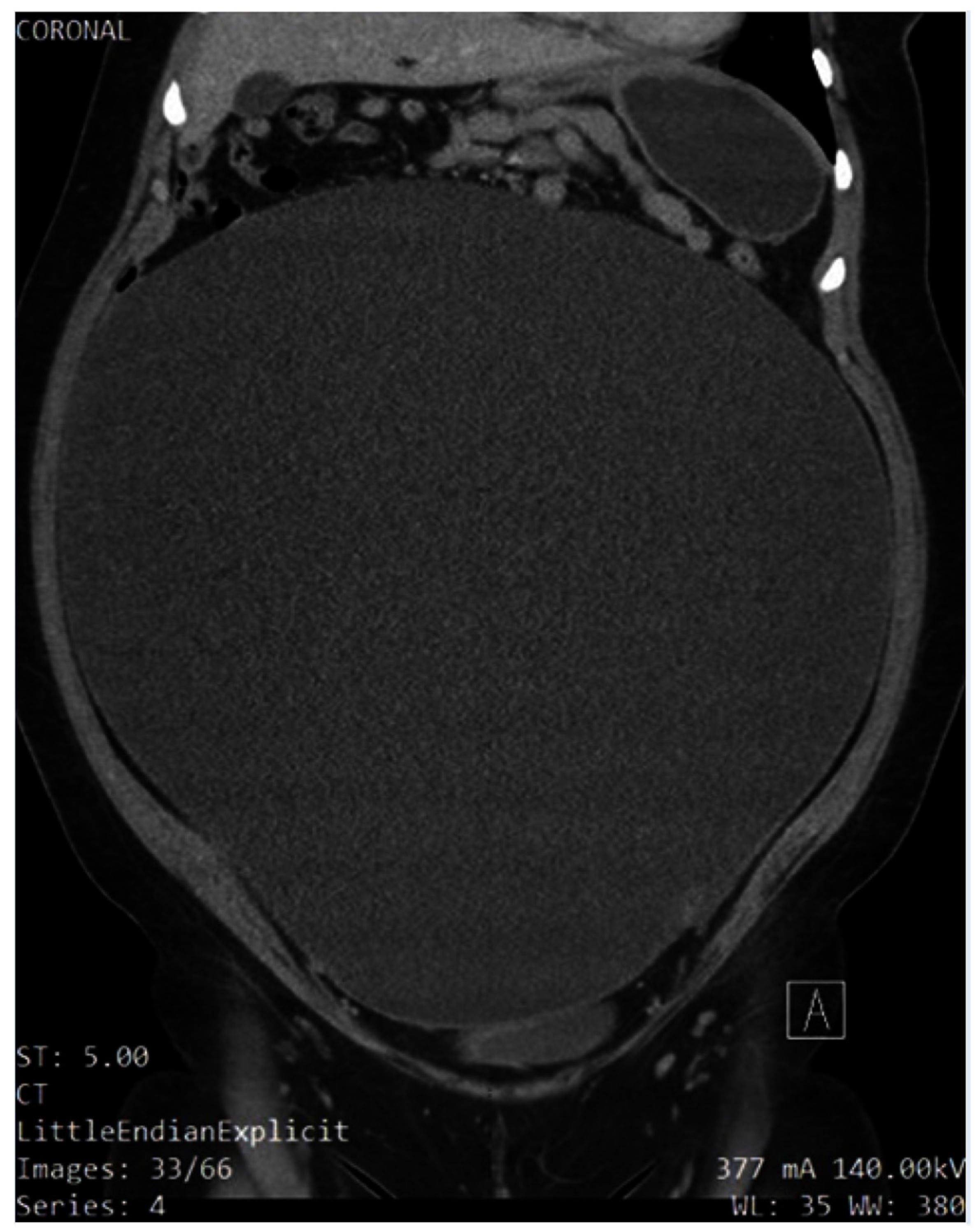

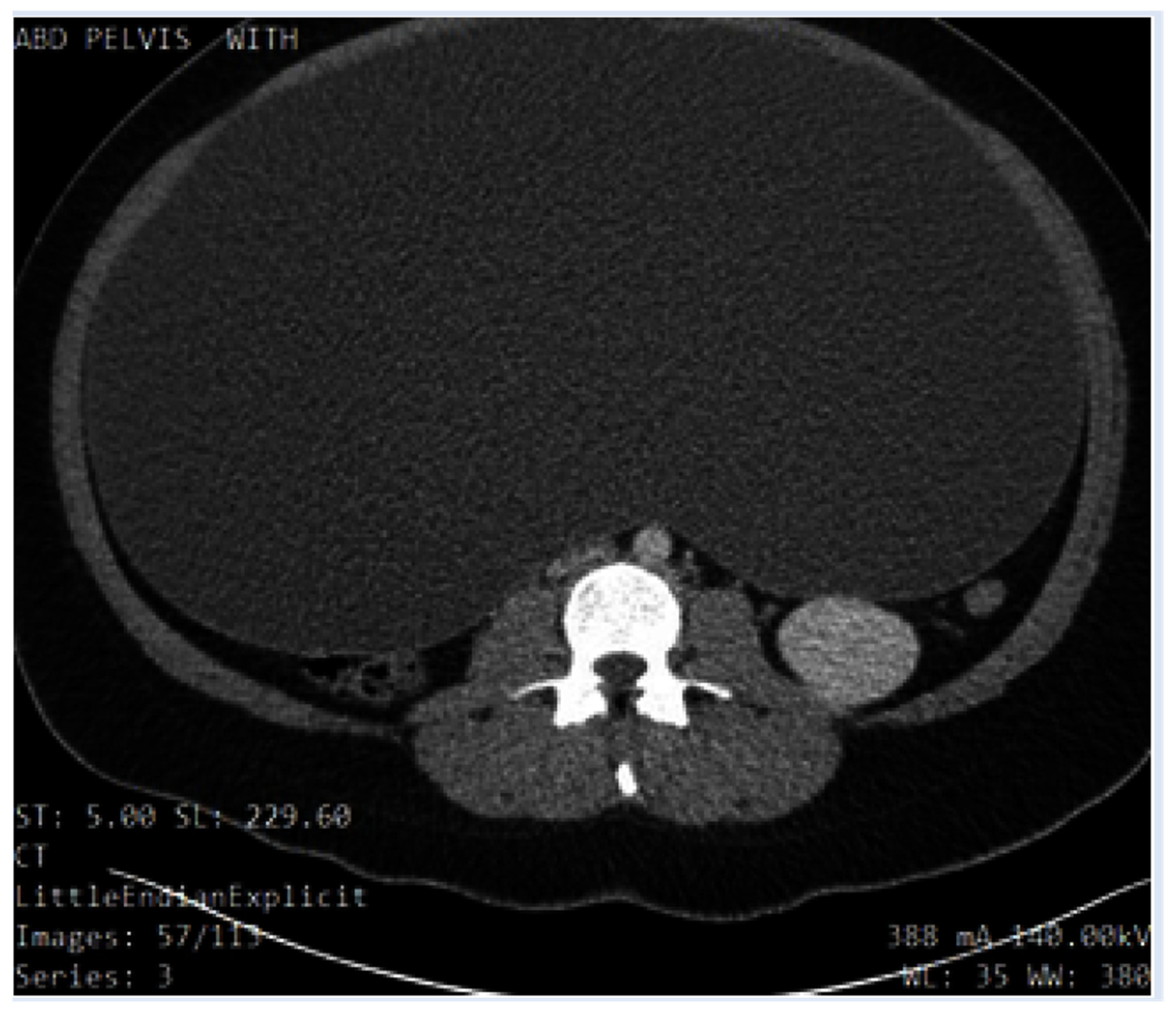

computerized tomography (CT) with contrast found a 36 cm cyst lesion filling the abdominal and pelvic cavity which appeared to originate from the left adnexa with a complicated hyperdense fluid or debris focus inferiorly (

Figure 3). The surrounding structures appeared unremarkable. There was a trace amount of fluid in the Douglas pouch

(Figure 4).

The patient’s pain and emesis were addressed with an anti-inflammatory ketorolac bromethamine 15 milligrams (mg) IV, antiemetic ondansetron 4 mg IV, and opioid analgesic morphine sulfate 4 mg IV, which had little effect on alleviating the patient’s pain. Intravenous 0.9% normal Saline and preoperative prophylactic intravenous antibiotics were administered. The patient consented to emergency exploratory laparotomy with counselling on the impact of an anticipated left salpingo-oophorectomy regarding her future fertility and was further advised that a biopsy would be sent to pathology.

A midline vertical skin incision was made, and the patient was found to have an ovarian cyst from the pubic bone to the chest. The cyst appeared to originate from the left ovary, which was in torsion. The incision was extended further, to five centimeters above the umbilicus, to ensure the removal of the cyst without rupture. The cyst was isolated in a bag, allowing half of its volume (eight liters) to be drained. A left salpingo-oophorectomy was performed, and the cyst was removed (along with a further 8 L of fluid) without rupture, with minimal blood loss (100 milliliters). The pathology report described the presence of a benign hemorrhagic serous cystadenoma (with a hemorrhagic left fallopian tube).

The patient tolerated surgery without complications and her postoperative recovery went well. During her stay, her anemia (hemoglobin was >100 g/dL) was not treated. In the months following surgery, the patient’s menstruation became “more regular” with approximately 5 days of heavy bleeding. The patient’s breathlessness was immediately relieved after surgery, resulting in no longer requiring the use of an inhaler. She lost further weight since the surgery and felt she has seen psychological improvements.

Approximately 12 months following the surgery due to concerns of dizziness (suspected to be related to anemia), she was started on oral contraceptives to reduce her heavy menstrual bleeding. However, no iron supplements were prescribed. The patient subsequently discontinued the oral contraceptive due to her apprehensions of side effects such as weight gain.

During her recovery, the patient wanted to share her history leading up to the emergency surgery. She shared that, for the past 6–7 years since she was 12/13 years old, she presented to her primary care doctor at least three times per year due to pain when lifting heavy objects and an intermittent rigidity of her abdomen (specifically umbilical). Further, she was concerned that her abdomen was enlarging, alongside her menstrual irregularities and dyspnea. She was advised by her doctor that her symptoms were due to obesity (told “you’re just fat”). At no time during the 9 years since the commencement of menses and bringing these concerns to her doctor was any investigations, scans, or blood test undertaken. Nor was she referred to a gynecologist where her age, duration of her symptomology (6–7 years), and otherwise general health may have been identified as a complicated benign ovarian cyst that had failed to involute, which turned out to be the case. Her body mass index (BMI) was not documented. No genetic testing was undertaken.

The patient eventually stopped presenting her concerns to her doctor over fears that the medical professionals were going to send her to a “special camp to lose weight”.

3. Discussion

Ovarian cysts are sacs that are filled with fluid and arise from ovarian tissue [

9]. They are most commonly benign and occur in women of reproductive age [

8]. In these women, endogenous hormone production usually stimulates the growth of such cysts during pregnancy [

9]. In postmenopausal women and in women whose cysts are not simple (e.g., solid), a malignancy is more likely [

12]. Whether the process of cyst formation occurs due to the failure of the dominant follicle to rupture or whether the immature follicles fail to involute is not known; however, the conclusion is the same [

13]. These cases usually result in the formation of functional types of cysts, such as corpus luteum cysts, theca-lutein cysts, or follicular cysts [

9]. Moreover, genetic mutations may play a role in the development of more malignant cysts, such as Lynch II syndrome or BRCA-1 and 2 mutations [

8,

14].

Due to the nature of ovarian cysts being mostly asymptomatic or spontaneously involuting, epidemiological data are difficult to ascertain [

1]. The occurrence of ovarian cysts is e

stimated to be 35% in premenopausal women and 17% in postmenopausal women [

15]

.

The small percentage of premenopausal women who experience rare, grossly enlarged cysts may have associated risk factors such as a history of early menarche, endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), pregnancy, or treatment for infertility. However, the patient in this case study had no associated risks [

6,

16].

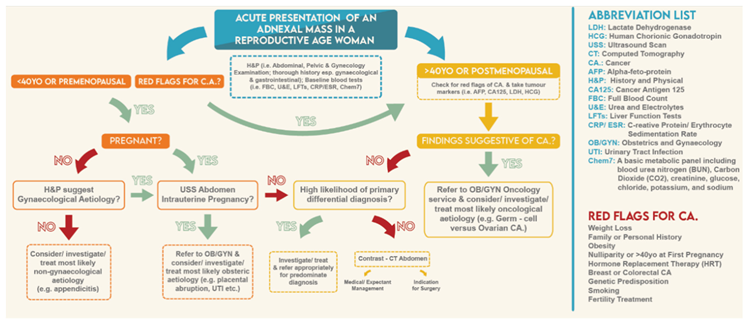

She experienced compression and distortion of abdominal–pelvic structures, which presented as bloating, pain, and difficult breathing. Her emergency presentation was a sharp increase in the pelvic pain and scans which revealed an adnexal mass

(i.e., masses in the fallopian tube, ovary, and/or associated tissue) [

4,

17]. She bought all these concerns to her physician’s attention for many years, but due to many potential factors (such as the doctor’s time constraints or factors like the financial incentive programs for physicians in US for faster patient throughput), along with seemingly vague symptoms, patient care was hindered [

4,

18,

19].

Nonetheless, continual, and consistent re-presentations in well over three visits should have raised a red flag and at the very least, some investigations should have been carried out [

1,

20].

To enable physicians in primary care to diagnose and manage patients’ symptoms, a “point of care” database could be used which can be directly impact patient care [

18].

Primary health care plays a vital role in the health and wellbeing of the population so any tools that assist in the management of this care can be of benefit [

21]. Yet, many express concerns that they have inadequate time to address all of the patients’ concerns [

22].

A therapeutic alliance between the primary physician and patient is a cornerstone of clinical care [

23]. Research has found that doctors miss many cues [

23] which can be addressed with training in communication to strengthen patient–doctor relationships and therapeutic trust [

24,

25].

In all situations, a thorough clinical history and physical examination are required, with a specific emphasis on gynecological and gastrointestinal etiologies (e.g., menstruation, pregnancy, bowel movements, etc.). However, the initial stabilization takes precedence over a more in-depth history of a patient in need of immediate care.

In this patient’s case, her primary care doctor may not have addressed her symptomatology, as they were non-specific, mild, and without any red flags. However, her oligomenorrhoea, significant weight gain, umbilical pain when lifting objects, and the patient’s growing concerns and continual presentation should have warranted more earnest consideration. Certainly, the patient did not feel heard or even acknowledged, eventually “giving up” trying to address her concerns after returning to her primary care doctor with the same medical complaint for years. Two factors interconnect in primary care: the patient’s concerns being articulated clearly and the physician’s response to enable better care outcomes; in this case, the patient lost faith and trust in the physician [

23,

26]. Further, she felt judged and repeatedly unheard in her concerns which she articulated during her hospital recovery.

The patient specifically wished to convey to the researchers that present and future clinicians should “double-check” the patient’s test results, as well as listen to their concerns regarding their presenting complaints which has been highlighted by other patients in other clinical settings [

7,

27].

The lack of a trusting relationship due to poor communication on the physician’s side has been shown to be detrimental in future patient–doctor relationships and therefore the patient’s future health [

28,

29].

Cysts that are >5 cm or have a complex pathology are unlikely to involute and therefore require surgical removal (if surgery is not contraindicated) [

16,

30]. Emergency presentations, such as rupture, hemorrhage, or torsion, are indications for emergency surgical intervention. Laparoscopic surgery utilizes smaller incisions and is more desirable for stable, simple cysts, as they have a reduced risk profile and recovery time [

6]. However, exploratory laparotomy, such as in this patient, may be required because of the complexity and size of the cyst, the presentation of the patient, and the fluid volume within the cyst [

31,

32].

When a cyst is likely benign (e.g., in a premenopausal woman who has plans to have children in the future), fertility-preserving surgery should be performed [

10]. Although the patient expressed her worries about conceiving in the future, she was comforted by knowing that her remaining ovary was still functional and unaffected by the surgery.

The clinical presentation and radiological or gross findings of the mass can be provisionally diagnostic for an ovarian cyst. The type of cyst (

Table 1) can be confirmed by histopathology. This patient had a common serous cystadenoma with some hemorrhagic debris, which likely caused a complex appearance in the radiological images. Her prognosis is reassuring considering that there has been no proven link between cystadenomas and conversion to ovarian cancer, with an overall survival of approximately 85% at 5 years [

8].

The cyst was twisted around the left fallopian tube, which was likely facilitated by its size, and it may have been present for an extended period of time before acute manifestations occurred due to some precipitating event, such as during defecation. However, the exact mechanism of torsion for such a large ovarian cyst is not clear in this patient. She had no clear risk factors or precipitating events aside from the size of the cyst, and the presence of the ovarian cyst itself is a risk factor for ovarian torsion. The larger a cyst is, the higher the risk of torsion [

30]. The likelihood of torsion and not the presence of an ovarian cyst was the primary reason for emergency surgery and the acute presentation in this case. Furthermore, adnexal masses in premenopausal women can be separated into gynecological and nongynecological etiologies (

Table 2).

The management of an enlarged ovarian cyst depends on the pathology of the cyst, its complexity (the radiological features including size, the histopathology, etc.), its effect on the adjacent structures, and the life-stage of the woman (pre- vs. postmenopausal) (

Table 3) [

34]. In a premenopausal woman, if a cyst is not complex and does not adversely affect the patient (e.g., does not compress the adjacent pelvic structures), then the cyst can be monitored, as it is likely to resolve spontaneously [

34]. However, explorative laparotomy is indicated if the cyst enlarges (or is >3 cm in size), becomes more complex, or begins to adversely affect the patient [

10]. In the case of this patient who presented with acute abdominal pain, the immediate management was an explorative laparotomy due to the possibility of a hemorrhagic cyst, the rupture of the cyst, or an ovarian torsion (which was the case for this patient), as well as its uncharacteristically large size [

32].

When a malignancy is more likely present in postmenopausal women or in older women with bilateral cysts, more radical management is undertaken, such as a frozen section biopsy, a bilateral oophorectomy, and a blood analysis for tumor markers (specifically, elevated serum CA-125) [

34]. When cases appear more complex, such as in this patient, the radiological findings can be used to give a preoperative risk stratification score. The Ovarian–Adnexal Reporting and Data System (O-RADS) is a valuable risk stratification and management tool for USA-based patients [

35]. The Risk Malignancy Index (RMI), which is based on the ultrasound scanning parameters set out by the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Group, is the primary radiological stratification tool that is used in the UK [

8,

10]. The prognosis for ovarian cysts is reassuring in the long term; however, there is an increased risk of ovarian cancer in premenopausal women if endometriosis is present [

36] (which was not the case for this patient).

4. Conclusions

Ovarian cysts are a common gynecological manifestation in premenopausal women. If the cysts are small (<10 cm), they tend to spontaneously involute without symptoms. However, in rare cases of enlarged cysts, these patients can present with symptoms that are consistent with the gradual compression of abdominal and/or pelvic structures or, as in the case of this patient, an emergency case of ovarian torsion. With an ovarian cyst of this size, there is a possibility of rupture, which is why patient education for safeguarding and clinical suspicion are vital to preventing serious complications.

This case also highlights the importance of the three-presentation or three-strikes rule in primary care screening for cancer: if a patient presents three times with the same complaint, this constitutes a yellow flag, and the patient’s concerns need further investigation. This is a debated rule; however, the researchers believe that, in this patient’s case, the presenting complaint had not been thoroughly investigated, and a more thoughtful consideration of this complaint should have been made to reduce or prevent serious misses or medical errors. This three-strikes rule would likely be useful in primary care not only for patients who are suspected to have cancer but also when there is a suspicion of the presence of a pathology that can lead to the detriment of the patient. In this patient, preventing this delay could have avoided the emergency admission for surgery and may have not adversely affected the patient’s future fertility plans.

5. Limitations

Case reports in general are unable to define a clear cause and effect in the disease as it is retrospective in design. It may also be difficult to generalize this research to a broader population because it is rare and unusual. The patient was interviewed and gave her account, but the primary care physician was not interviewed so there is a potential for patient-centric bias.

To reduce the limitations and improve the quality of this report, it was written adhering to the Consensus-Based Clinical Case Reporting (CARE) Guidelines.

Author Contributions

A.U. and C.B.B. agreed on the study conception, study design, and data analysis. Data collection was completed by A.U. Initial drafts were completed by A.U. and C.B.B. Reviews and further editing were performed by A.U., C.B.B., and J.B. AJE and MDPI services were used for final editing, formatting and figure formating before submission for publishing. A.U., C.B.B. and J.B. approved the final version and consented to publish. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This case study was approved by the IRB at the Swedish Hospital in Chicago, IL. The patient was also briefed and consented to being a part of this case report.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to my colleagues who provided robust and intellectual discussions that contributed to enhancing this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

CT: computed tomography, USS: ultrasound scan, BP: blood pressure, IV: intravenous, UK: United Kingdom, USA: United States of America, PCOS: polycystic ovarian syndrome, ACOG: American College of Gynecology, RCOG: Royal College of Gynecology

References

- Oliver, A.; Overton, C. Detecting ovarian disorders in primary care. Practitioner 2014, 258, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pramana, C.; Almarjan, L.; Mahaputera, P.; Wicaksono, S.A.; Respati, G.; Wahyudi, F.; Hadi, C. A Giant Ovarian Cystadenoma in A 20-Year-Old Nulliparous Woman: A Case Report. Front Surg 2022, 9, 895025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappen, T.; van Dulmen, S. General practitioners’ responses to the initial presentation of medically unexplained symptoms: a quantitative analysis. BioPsychoSocial Medicine 2008, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, C.E.; Ranjit, E.; Sapra, A.; Bhandari, P.; Wasey, W. Clinician Beware, Giant Ovarian Cysts are Elusive and Rare. Cureus 2020, 12, e6753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, P.V.; Attinà, G.; Spadola, S.; Caltabiano, R.; Farina, R.; Palmucci, S.; Zarbo, G.; Zarbo, R.; D’Arrigo, M.; Milone, P.; et al. MR imaging of ovarian masses: classification and differential diagnosis. Insights Imaging 2016, 7, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, B.; Niang, M.M.; Ba, P.A.; Toure, P.S.; Sy, A.; Wane, Y.; Sarre, S.M. Management of Giant Ovarian Cysts: A Review of 5 Case Reports. Journal of Gynecologic Surgery 2016, 32, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.; Rogers, A.; Salmon, P.; Gask, L.; Dowrick, C.; Towey, M.; Clifford, R.; Morriss, R. What do patients choose to tell their doctors? Qualitative analysis of potential barriers to reattributing medically unexplained symptoms. J Gen Intern Med 2009, 24, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of Suspected Ovarian Masses in Premenopausal Women. 2011, 14.

- Mobeen S., A. R. Ovarian Cyst; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Terzic, M.; Aimagambetova, G.; Norton, M.; Della Corte, L.; Marín-Buck, A.; Lisón, J.F.; Amer-Cuenca, J.J.; Zito, G.; Garzon, S.; Caruso, S.; et al. Scoring systems for the evaluation of adnexal masses nature: current knowledge and clinical applications. J Obstet Gynaecol 2021, 41, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, A.L.; Huang, O.Y.; Rakočević, R.; Chung, P. Critical iron deficiency anemia with record low hemoglobin: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2021, 15, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafin, C.; Vesnin, S.; Turnbull, A.; Dixon, M.; Goltsov, A.; Goryanin, I. Diagnostics of Ovarian Tumors in Postmenopausal Patients. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.H.; Turnbull, L.W.; Richmond, I.; Helboe, L.; Atkin, S.L. Localisation of somatostatin and somatostatin receptors in benign and malignant ovarian tumours. Br J Cancer 2002, 87, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fostira, F.; Papadimitriou, M.; Papadimitriou, C. Current practices on genetic testing in ovarian cancer. Ann Transl Med 2020, 8, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gynecologists. , A.C.o.O.a. Practice Bulletin No. 174: Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses. 2016, 128, e210–e226. [CrossRef]

- Ross, E.K.; Kebria, M. Incidental ovarian cysts: When to reassure, when to reassess, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2013, 80, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gynecology. , O. Practice Bulletin No. 174: Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2016, 128, e210–e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.T.; Pincock, D.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sadowski, D.C.; Fedorak, R.N.; Kroeker, K.I. An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success. npj Digital Medicine 2020, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Sulb, A.; Abu El Haija, M.; Muthukumar, A. Incidental finding of a huge ovarian serous cystadenoma in an adolescent female with menorrhagia. SAGE Open Medical Case Reports 2016, 4, 2050313X16645755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protus, B.M. BMJ Best Practice. J Med Libr Association 2014, 102(3), 224–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, D.; Thukral, A.; Kumar, P.; Deorari, A. Harnessing mobile technology to deliver evidence-based maternal-infant care. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, H.; Quera, V.; Graugaard, P.; Finset, A. Physician–patient dialogue surrounding patients’ expression of concern: applying sequence analysis to RIAS. Social Science & Medicine 2004, 59, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, W.; Gorawara-Bhat, R.; Lamb, J. A Study of Patient Clues and Physician Responses in Primary Care and Surgical Settings. Jama 2000, 284, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roter, D.L.; Hall, J.A.; Kern, D.E.; Barker, L.R.; Cole, K.A.; Roca, R.P. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress: a randomized clinical trial. Archives of internal medicine 1995, 155, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, D.A.; Goold, S.D. Maintaining Trust in the Surgeon-Patient Relationship: Challenges for the New Millennium. Archives of Surgery 2000, 135, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detmar, S.; Aaronson, N.; Wever, L.; Muller, M.; Schornagel, J. How are you feeling? Who wants to know? Patients’ and oncologists’ preferences for discussing health-related quality-of-life issues. Journal of clinical oncology 2000, 18, 3295–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, T.; Fahey, T. Defining diagnosis: screening and decision making in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2003, 53, 914–915. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.A.; Irish, J.T.; Roter, D.L.; Ehrlich, C.M.; Miller, L.H. Satisfaction, gender, and communication in medical visits. Medical care 1994, 1216–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graugaard, P.K.; Holgersen, K.; Eide, H.; Finset, A. Changes in physician–patient communication from initial to return visits: a prospective study in a haematology outpatient clinic. Patient education and counseling 2005, 57, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Hong, M.K.; Ding, D.C. A review of ovary torsion. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi 2017, 29, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, C.; Barbosa, B.; Santos, N.; Oliveira, A.; Casimiro, C. Giant abdominal cyst in a young female patient: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2020, 72, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, L.M.; Chang, S.D.; Horng, S.G.; Yang, T.Y.; Lee, C.L.; Liang, C.C. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for surgical intervention of ovarian torsion. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2008, 34, 1020–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravishankar, T.N.; Makarand Jadhav, H.; Satheesh Kumar, N.; Ambala, S.; Pillai N, M. A deep learning approach for ovarian cysts detection and classification (OCD-FCNN) using fuzzy convolutional neural network. Measurement: Sensors 2023, 27, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, W.S.; Marks, S.T. Diagnosis and Management of Adnexal Masses. Am Fam Physician 2016, 93, 676–681. [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti, R.F.; Timmerman, D.; Strachowski, L.M.; Froyman, W.; Benacerraf, B.R.; Bennett, G.L.; Bourne, T.; Brown, D.L.; Coleman, B.G.; Frates, M.C.; et al. O-RADS US Risk Stratification and Management System: A Consensus Guideline from the ACR Ovarian-Adnexal Reporting and Data System Committee. Radiology 2020, 294, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-J.; Cao, D.-Y.; Yang, J.-X.; Shen, K. Ovarian metastasis from nongynecologic primary sites: a retrospective analysis of 177 cases and 13-year experience. Journal of Ovarian Research 2020, 13, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).