1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction

The number of disabled people in a given context is often underappreciated and underestimated. The World Health Organization reported that over 15% of the world population is affected by disabilities (WHO, 2011). In the reality, the population size of those living with disabilities can be considered even larger given the chance of contracting a disability during the path of life (WHO, 2022a), as well as the wide range of the disabilities (ibid.). In this regard, the UN Disability Inclusion Strategy states that “the lack of disability-related data, including qualitative and disaggregated data, is one of the major barriers to the accurate assessment of disability inclusion in the development and humanitarian contexts” (UN Disability Inclusion Strategy, 2020, p.2). Moreover, the more blurred and liminal situation of those marginalized with invisible conditions such as depression and schizophrenia must also be considered when holistically identifying the population living with disability (WHO, 2022a). The difficulty in accurately estimating the number of people living with disability is that impacts extend beyond the traditional health sciences and include those connected to the personal and social isolation of the affected individuals (Emerson et al., 2021), and also is linked to issues of loneliness (Gómez-Zúñiga et al, 2023). The interrelationships between traditional healthcare and its related disciplines can be rendered as factors of inequity (WHO world disability report), as represented in

Figure 1.

The four factors of inequity that contribute to the definition of individual health and wellness can be described as follows:

Structural factors account for the ‘very broad socioeconomic and political context and the mechanisms that generate social stratification’ (WHO, 2022). This factor affects the key components that shape the base of the healthcare system, for example, the capacity of the State to structure its welfare programs.

Social determinants include the social life conditions of a given person. The social sphere existing around a single individual is a relevant factor in defining life possibilities, for instance, a social network which can affect their social behavior.

Risk factor considers issues of noncommunicable diseases, environmental factors, healthy and active lifestyle. It is a holistic view of the topic that includes the private sphere and the behaviors of an individual.

Health system factors include the accessibility of the health services, information, medical support, etc. It is a factor dependent on the conditions of welfare within the State, by the organization of the general healthcare system and it affects the possibilities of the individuals to receive care and medical assistance at different levels.

The general underappreciation of these factors by the general public and urban stakeholders results in an underestimation of the needs of people with disabilities and to a lack of physical spaces of inclusion, especially in peripheral metropolitan areas.

In this study, we employ the pragmatic epistemology of Research through Designing, which incorporates elements of the (post)positivist, constructivist, and advocacy/participatory epistemologies (Lenzholzer et al., 2013). The post(positivist) epistemology seeks to determine the performance of a project and in this case, may consider ideas of how effective is the universal design in accommodating people with a diversity of disabilities. The constructivist epistemology generally considers the type of landscape (or park/greenspace in our context) that the designer can create. This approach may include classic ideation and creative reflection-in-action techniques that address the community’s sensing, thinking and behavior. Finally, the advocacy/participatory epistemology directly involves community with problem identification and data collection. As per the scope of this research that ultimately produced the redevelopment design for an existing park through the pragmatic research through designing process, the four factors of inequity were interpreted as opportunities and adopted as guiding principles in the two phases of the study (qualitative/quantitative research; design of the redevelopment of the park) as follows, where the opportunity is highlighted in italics.

Redevelopment of a park into an inclusive space for disabled users acts on structural factors. Socioeconomic and political context represents an invariant factor that influences the redevelopment of an existing park into a space for people living with disability. Context, including consideration of cause-effect relationships is an essential element of effective design. An inclusive park, rooted by research through designing, and backed with quantitative and qualitative data coming from the surveys, can constitute an invaluable asset in the social context at various scales.

Redevelopment of a park into an inclusive space for disabled users pivots on the social determinants. The future redevelopment of the existing park would positively increase the opportunities for social gathering. As described in the following sections, this is a need particularly felt by the target group as determined through administration of the quantitative surveys.

Redevelopment of a park into an inclusive space for disabled users limits the risk factors. The future redevelopment of an existing park can contribute positively to the wellness of those living with disability, providing a green and stimulating healthy public space.

Redevelopment of a park into an inclusive space for disabled users influences the health system factor. This factor offers two opportunities. In the first place, qualitative reflections from stakeholders provided us with a deeper and richer understanding with respect to the needs of those living with disability. Secondly, it guided a dominant principle within the design concept: to be a free, public, open, inclusive and accessible gateway to a more active lifestyle.

1.2. Objectives

This article follows the definition of the principles for inclusive and accessible parks in Pathum Thani Province, Thailand (Selanon et al., 2022a), and the selection of a green existent area (The Thammasat Water Sport Center) within this provincial context where a possible redevelopment into an inclusive and accessible park for disabled is expected to have potential success (Selanon et al., 2022b). The objective of the research presented herein is to redevelop the existing space into an inclusive park for autonomous access by the disabled community.

We begin by introducing quantitative study with questionnaire surveys conducted with local stakeholders and people with disabilities. Secondly, we describe the design memory of the reconversion of the park (i.e. the design project). The design project is then discussed and evaluated, including the exploration of limitations existent between the perception of the users and the designers’ answers.

2. Literature Review

The social concept of disability sees an individual suffering from a particular disability as being a deviation to the norm, which can result in marginalization The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF, 2001) provides a generally-accepted definition of disability. The document, updated periodically (lastly, in January 2023), establishes three main areas of disability, impairment; activity limitation; and participation restriction. In the Thai context, the normative framework sets up seven different categories of disabilities (Ministry of Social Development and Human Security, 2012), with no further specifications. The research adapted this categorization in the first phase of the research, with regard to the questionnaire.

The inclusion of consideration of disabilities in public spaces is prioritized in various documents from the United Nations (UN) under the definition of the concept of accessibility. The 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is central to the international recognition of persons living with disabilities in that it defines the principles for inclusion. Specifically, Article 9 defines the principle of the Accessibility in the built environment “to ensure to persons with disabilities access, on an equal basis with others, to the physical environment, to transportation, […] and to other facilities and services open or provided to the public, both in urban and in rural areas. “(UN, 2006). The 2006 principle becomes a key concept, in an expanded definition of accessibility (UN, 2020, p.21).

The latest Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities, Physical Declines, a Primary Health-Care (PHC) targeted action for the inclusion of persons with disabilities to the built environment pushes to “incorporate a universal design-based approach to the development or refurbishment of health” (UN Global report extended, 2022). The document advises also to include a budget for inclusiveness and accessibility in the preliminary phase of design work, and noting the potential for lost opportunities in terms of social possibilities for the disability carriers (ibid., p. 222), and how the interrelation of the strategic entry points can strengthen the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 – Good Health and Well-Being (ibid., p. 160) empowering the participation of marginalized individuals to public life.

In relation to the built environment, beside the aforementioned SDG 3, the SDG goals connect disabilities and built environment tightly in 2 goals: SDG 10 – Reduce Inequalities and SDG 11 – Sustainable Cities and Communities, as a most impactful way for improving accessibility in the built environment (UN-DESA, n./d.a; UN, 2015; WHO, 2019). SDG 10 remains more connected to general policymaking, while SDG 11 aims to directly tackle the built environment in two specific measures. SDG 11.3 aims to “enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management” (UN, 2015); SDG 11.7 mentions the need for green park and public spaces “to provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities” (ibid.).

Parks are crucial elements of the urban environment as physical activities and social interaction within the parks can give a positive impact on urban residents’ quality of life (Irvine et al., 2021). Parks should be places that respond to the needs of people from different social and cultural backgrounds with a diversity of user groups in mind (Singh,2023). However, many aspects of parks are not designed for people with disabilities in mind (ASLA, 2023). For those parks that have been designed for people with disabilities, universal standards often have not been fully taken into account as part of the design process. As a result, parks often lack consideration of the distance that people with disabilities can comfortably negotiate. Some parks may have designed walkways that are wide enough for wheelchair access; however, these walkways do not fully the park area. Some parks have obstacles to the use of wheelchairs while others provide rides and equipment that are not suitable for people with disabilities. People with disabilities therefore are often unable to use the park space effectively. Additionally, most parks for people with disabilities do not facilitate social interaction with broader public. Behind such considerations is the basic idea that green spaces must be accessible, safe, and offer both comfort and maximum enjoyment. This awareness should be enhanced by offering proper amenities such as having properly designed walkways with ramps and railings, accessible public toilets, and usable telephone booths in greenspaces. The built environment must incorporate certain aspects of sound, texture, and other design elements to assist a person with disability in their surroundings. Knowing the basic necessities of the disabilities will assist the designers and planners to improve the built environment.

3. Materials and Methods

The first phase of the two-phase study involved the formulation and administration of a questionnaire, focusing on recreation activities of disabled people and perceptions of desired future spatial arrangement in public spaces. The sample size for survey participants was calculated resulting in a minimum of 369 people. The study was able to employ the sample size of 384 people. The surveys were designed with two sections:1) general information; and 2) needs and interests in active recreation activities. The close-ended, but also open-ended questions enabled participants to elaborate on their perceptions.

Results from the surveys were quantified using descriptive statistics in Microsoft Excel. Focusing on analysis of the survey section 2, perceptions and suggestions of the needs and interests in active recreation activities, the results were quantified as percentages. The qualitative results emerging from the survey were used to inform the design criteria, as discussed in section 4.4. In section 5, we clarify and explain the redevelopment of the park. Methodologically, the subsection 4.4 and the section 5 represent the core of the research through designing approach to landscape architecture.

4. Results

4.1. Background of the Survey Participants.

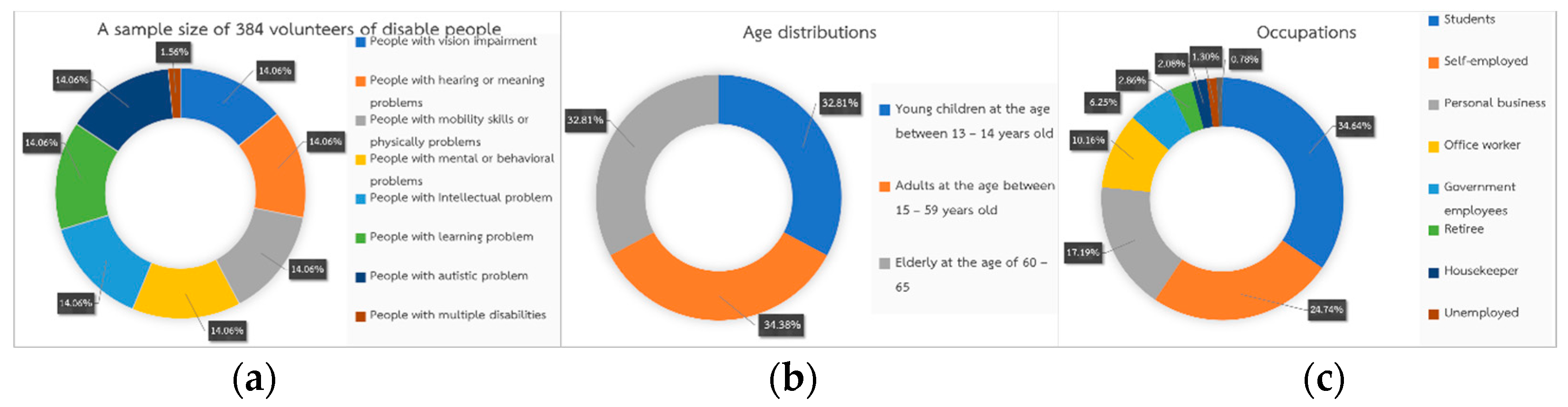

A sample of 384 persons with disabilities participated in the survey, their disabilities categorized into 8 groups: 1) people with vision impairments, 14.06%, 2) people with hearing problems, 14.06%, 3) people with mobility skills or physical problems, 14.06%, 4) people experiencing mental health issues or behavioral problems, 14.06%, 5) people with intellectual challenges, 14.06%, 6) people with learning difficulties, 14.06%, 7) people experiencing some form of autism, 14.06%, and 8) people with multiple disabilities, 1.56% (

Figure 2).

There was a slightly greater proportion of female respondents at 51.30%. The age distribution of the participants can be classified into three categories 1) 32.81% children, ages 13 – 14 years, 2) 34.38% adults between 15 – 59 years, and 3) 32.81% elderly with ages of 60 – 65 (

Figure 2). Occupations of the respondents were 1) students at 34.64%, and 2) self-employed at 24.74% (

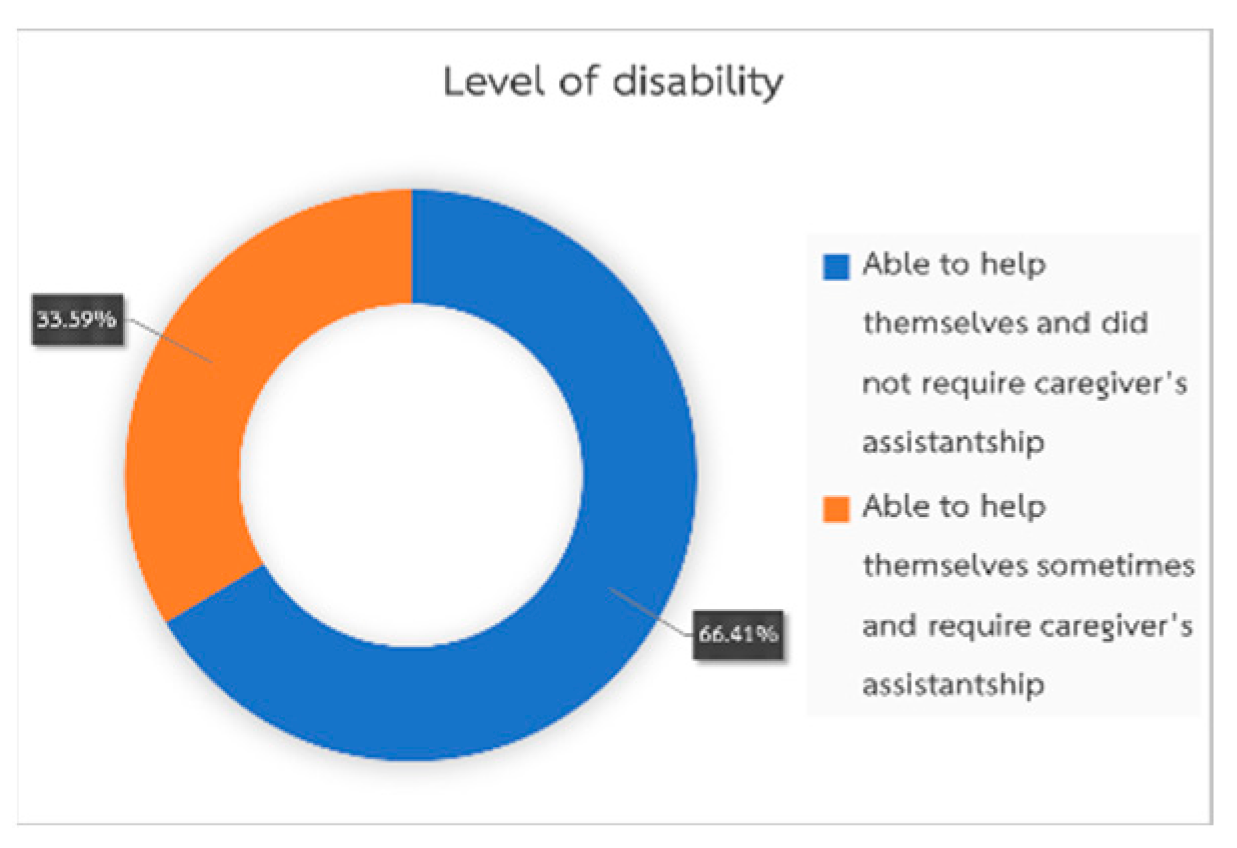

Figure 2). With respect to living assistance, 66.41% were able to help themselves and did not require a caregiver’s assistance, while 49.50% did require some help from the caregivers (

Figure 3).

4.2. Need for Programs and Facilities in a Public Park.

The overwhelming majority of respondents, 98.70%, preferred to exercises with the general public. Furthermore, 58.70% preferred individual exercise, 29.60% would enjoy a group of 2 – 3 people, 10.70% would like to exercise with a group larger than 3 people.

Outdoor exercise behaviors can be summarized as follows, 1) 35.80% of the respondents favored walking-running activities, 2) 20.90% preferred cycling, 3) 14.30% suggested multi-purpose exercises such as balancing, stretching exercises, yoga, aerobics, tai chi, etc., and 4) 2.90% required exercise in wheelchairs for disabled people (

Table 1).

The interests in passive recreation activities for public spaces can be summarized respectively, 1) 46.50% for meeting point activity, 2) 39.90% for picnic activity, 3) 11.70% for drawing activity, and 4) 2.00% for other modes of activities.

In addressing public park space and facilities requirements, 6 items were discussed. First, the results revealed that accommodation pavilions were desirable for 30.70% of people with intellectual disabilities, 26.90% for people with hearing disabilities, and 23.50% for people with autism. Second, a multi-purpose exercise activity yard was preferred by people with learning disabilities (19.00%) and people with multiple disabilities (15.20%). Third, parking space for people with disabilities was a top priority for people with mobility disabilities, at 15.50%. Fourth, social spaces were most important for people who are visually impaired (14.20%). Fifth, 14.20% of people who are visually impaired and 15.20% of people with multiple disabilities (highest value item) would like access to specialized exercise equipment. In addition, the highest response for people with mental health disabilities (13.90%) were bathroom areas and a recreation space.

Activities that relied on balancing and coordination and movement of the body such as Tai Chi, and yoga are often done as a group with lead performers and with or without rhythmic music and this results in higher social interactions. These activities can be performed at either indoor or outdoor spaces.

Physical enjoyment activities desired by the respondents can be categorized into two types as follows, 1) dancing activities such as imitating dance moves, creative dancing, etc., and 2) playing music, including band music and independent musical activity, etc.

It can be clearly seen that people with disabilities have a great demand for physical recreation activities. In addition, alternative recreational supporting activities were identified, including meditation and mindfulness activities Indeed, some of the respondents expressed interest in religious related activities such as meditation and mindfulness which required trainers and caretakers to ensure safety of the participants. Some suggestions to facilitate these activities included having a peaceful area by a pond in the absence of disturbing noises from traffic. The benefits of these activities for people living with disability include better daily activities performance and improved working efficiency.

We also see an opportunity to add new activities that are shared between people with disabilities and general users. These two groups can exchange views in a social setting and collaborative participation would provide an opportunity for the general public to better understand and appreciate living with a disability. Some respondents suggested that using a public park by themselves was an issue of concern. Therefore, assistantship service should ensure equal and safe access to the park. It appears that all disabled groups included in this study would benefit from guardians to help them access public spaces, especially those having multiple disabilities and who may have difficulties in accessing information, equipment, or asking for help in case an accident occurs.

4.3. Suggestions of participants from the survey.

Key recommendations for balancing-exercise guidelines were to install handrails, as well as having walking sticks and crutches available. Furthermore, choosing smooth, non-slippery, and soft surface materials would help those with disabilities to reduce the probability of a fall and should a fall occur during exercise, there would be a lesser risk of injury. Moreover, the selection of fitness accessories should consider ease of use, convenience, and light weight. Safety is the utmost important exercise guideline to prevent risk of accidents. In addition, caregiver assistantship may be considered in choosing equipment and methods of exercise.

Some major recommendations for hands and arm muscle exercises were provided for ball accessories. Consideration must be given to ball size where a small size is appropriate for hand compression and a moderate size for ball throwing, receiving, and passing activities. The balls also should have appropriate weight to prevent accidents during exercise. Moreover, a high-level handrail node including single and double railings should be established, and stocked with body protection equipment such as gloves, helmets, sleeves, etc.

Suggestions for sports field physical activities guidelines were to install sun and rain protection roofs as well as to improve tree coverage to provide shaded areas.

Any surface materials shall be selected for smooth, non-slippery, and no obstacles to the exercise area. Soft materials shall be chosen for wall covering especially to corner areas to prevent accidents that may occur from collision.

Focusing on sitting and use of spaces, there should be an appropriate number of sitting spaces, cushions, and handrails provided for performing activities.

Additional suggestions focused on having information signboards clear directions and details. Some physical activities and spaces such as balls, basketballs, and ping pong balls were suggested to have sound-producing devices installed, thereby accommodating people with hearing impairments.

Considering protection measures for some activities, net installation can prevent balls from leaving the activity area and make it easier to collect the balls as well as preventing the interference with other activities from another area. Moreover, it was suggested to have assistants for informing proper use and participation for each of activity.

Additional suggestions are to provide a special wheelchair service free of charge. Wheel chairs should be rotated freely in all directions and should be regularly maintained and safe to use. The new park should also provide accessories for wheel chairs such as belts for fastening. Activity performance should be done on flat smooth surfaces with no physical obstacles a wider path to support wheelchair movement, and supporting ramps for more convenient access. In addition, there should be a specific green physical activities area designed for wheelchair-accessibility.

Further recommendations on relaxation and provision of a peaceful atmosphere for relieving stress and worry should include a design having great numbers of trees to provide shade and fresh air. Moreover, there should be lawn areas where children can run, sit, and play as well as decorations, monuments, and entertainment such as running water, fountains, and music for relaxation.

In summary, based on respondent recommendations, open spaces should have, 1) no obstructions, 2) smooth surfaces, 3) no level variations, 4) clear path separation for walkways, jogging and bicycle, 5) clear and sufficient information boards, 6) easily accessible meeting points, 6) variety of learning improvement activities, 7) green area without cars and noise interference, 8) food distribution area, 9) bicycle lending service, 10) clean and all accessible bathrooms, and 11) close distance car parking area, etc.

A set of addition recommendations from the respondents can be describes as follows, 1) there should be a variety of standardized, universally-accessible exercise equipment for supporting every activity, 2) having group exercises together with general users, 3) sponsoring sporting events for people with disabilities, 4) have coaches and caregivers available to help on using equipment, 5) the need for having clean bathrooms, 6) suitable waiting area, 7) food distribution point, 8) vocational training center to provide services to support activities, 9) spaces for allocate disabled people proportionately, 10) clear symbols, sound signals, and ramps to facilitate wheelchair access, 11) spaces with trees shaded areas, 12) installed emergency buttons that allow assistances to reach in case of needing helps, and 13) the park should be free of charge.

4.4. From Insight to Design Criteria.

The nature of the open questions offered to the participants produced a diversity of results unrelated to the specific site. To avoid biases, the participants were not instructed on the specific project details. The specific location of the project was not disclosed nor mentioned. The other set of insights coming from the close-ended questionnaire and graded with the Likert scale produced, similarly, a general appreciation of the statements proposed in connection with the personal views of the participants. Each of these insights was also remarkably related to the specific disability – or mix of disabilities – of every participant. As a result, the broad range of insights provided a comprehensive ideal impression of a park to be interpreted: an optimal idea, rather than a direct set of inputs to be followed in the design.

The second phase of the research weighted and evaluated these insights: the design team balanced these with the site specifications, opportunities, and constraints, in defining a proposal which tried to create a compromise between the results and the real possibilities. The first consideration was taken in regards of the specificities of the survey sample.

The presence in the demographics of almost one-third of participants aged 13-14 implied a constraint on independency of movement related to the minor age, rather than to their specific disabilities. This issue was considered by the designers in relation to two site specificities: one, the site macro area does not allow an easy movement or reachability of the area at the urban scale – besides the presence of public transportation lines and public vans; two, the site’s surroundings are freely accessible but are strongly connected to the community of the Thammasat University, whose staff and students live in the area surrounding the site and whose age is above the youngest demographic queried. For these reasons, the designers determined that an autonomous access and an autonomous fruition of the park by this demographic, 13-14, is less likely to happen. This consideration is made visible in the design by the presence of playground devices valid for all ages (including the last group aged 59 and beyond) and by the absence of specific recreational devices for youth and children.

Similarly, consideration was given to the 34.60% of the sample’s composition (students of different ages), and the 24.70% (self-employed). The designers aimed to prioritize the areas for social engagement, inclusion and integration for these demographic transversal groups (not connected to the age) for two specific reasons: to blend in the context of students from diverse schools and backgrounds; and to provide the self-employed with an opportunity for public social gatherings far from their employment status. As such, these principles were conceptualized into open structured and semi-structured spaces.

Over 73% of the participants affirmed they had no underlying diseases which could additionally affect movement, while over the 65% indicated their health satisfaction was 8/10 or higher on a Likert scale. As a consequence, open structured and semi-structured spaces were blended to the exercise area to promote a seamless transition between passive and active recreation.

The 99% of users who declared to be willing to use exercise areas in public for individual exercise mostly (58.70%); in a group of 2-3 people (29.60%); in 3 or more for the remaining 11.70%. The last element of reflection connected to the demographic topic is that of self-help: a 66.40% of the sample identifies as a self-assisted person, while 93% identified as a person which can explore the space with no constraints. These insights reinforced the general overall conceptual idea of autonomous use and access of the park by all of the seven ranges of disabilities.

The next section describes the design intervention which arises from these data-driven insights. The features of the site, of the context, and of the design are illustrated with figures.

5. Integration of the Results of the Study into the Design of the Inclusive Park 1

5.1. Site area and context

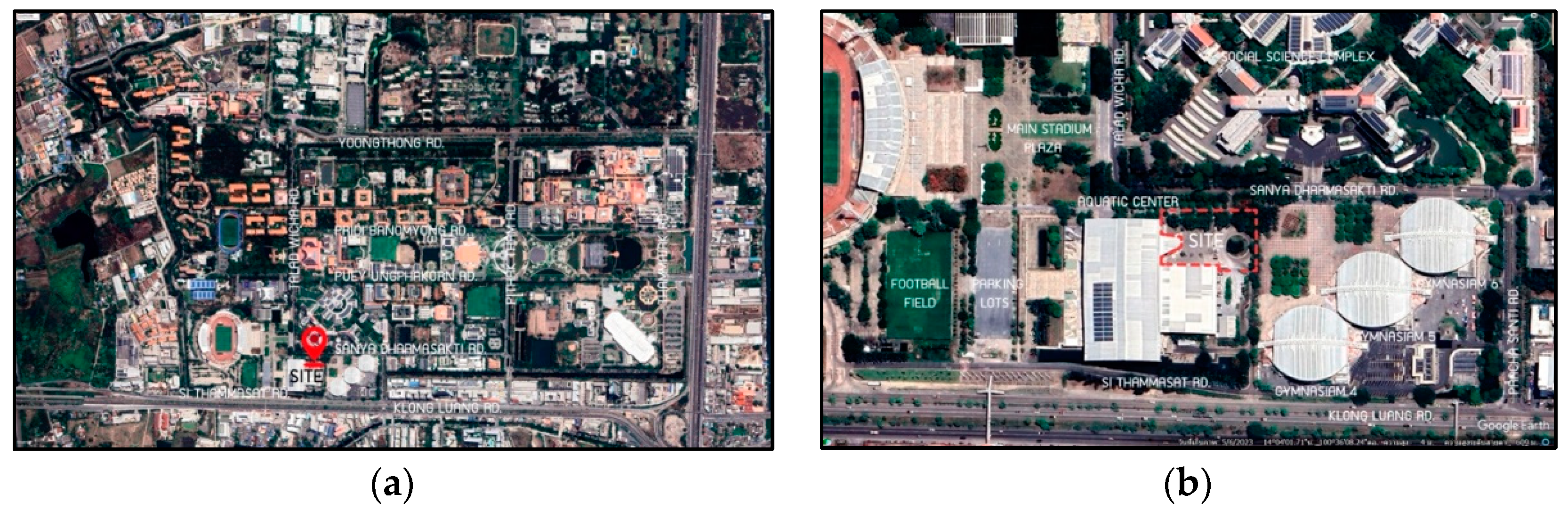

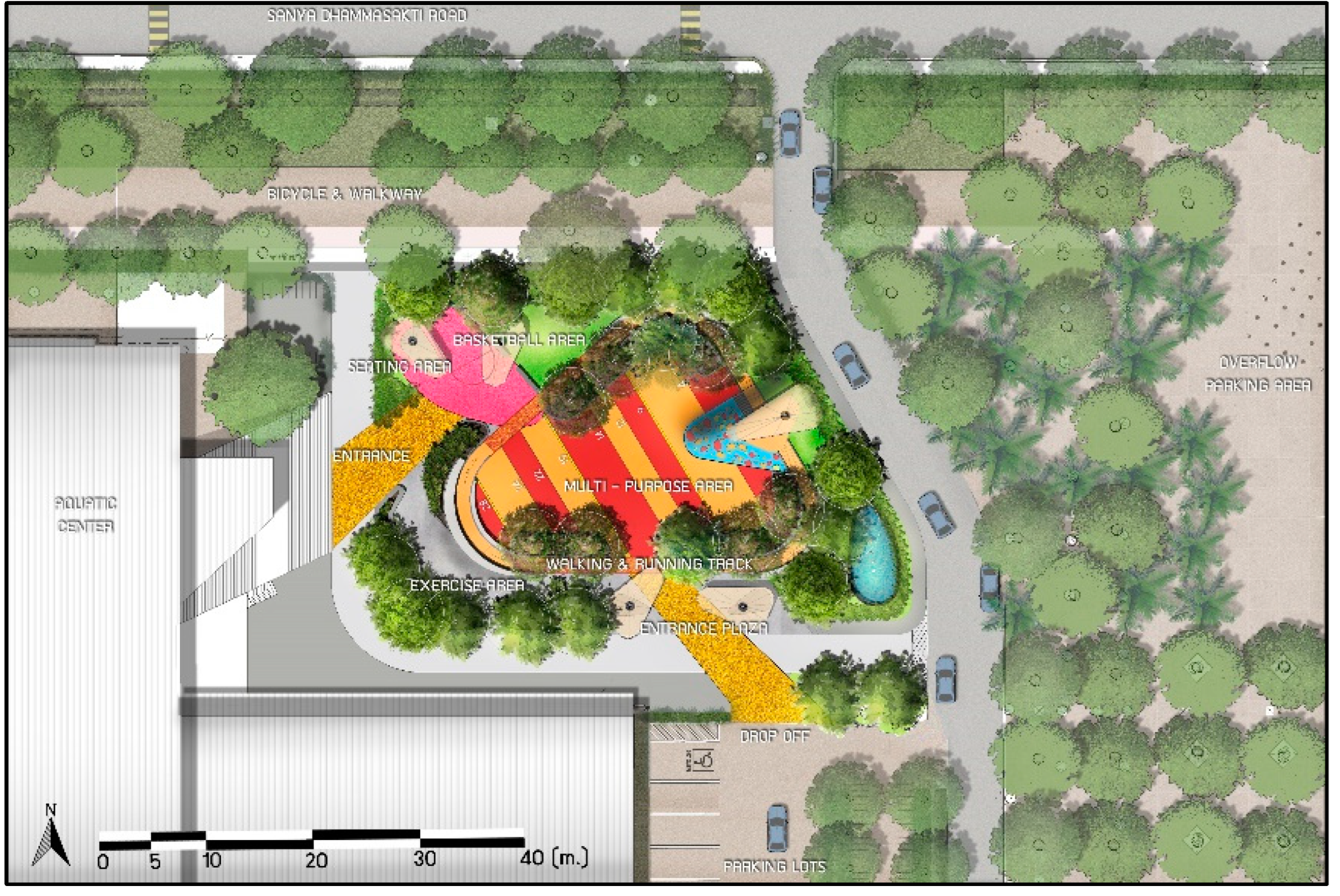

The project is located within the perimeter of the Thammasat University (TU), Rangsit Campus, Pathum Thani Province, in an open space overlooking the entrance of the Water Sport Complex Building (

Figure 4). The space is surrounded by commercial activities (small shops and cafes) and cultural and sportive recreation spaces (gym, multi-purpose room); the presence of this landmark influenced several design choices especially in terms of accessibility and layout.

The site has a surface area of 2,334 sqm (roughly 54 x 43 m) and is bordered on the north side by Sanya Dharmasakti Road; the road and park are separated by a cyclo-pedestrian sidewalk which runs parallel to the road. The main entrance is located on the opposite side facing the main parking lot and it is opened only on occasions of special events. On the west, the space is bordered by the iconic semi-covered access stairway of the Water Sport Complex Building. The wheelchair access to the complex is provided behind the staircase.

On the south, the site is bordered by the aforementioned commercial activities, recreational spaces, and a parking lot; on the east, by a wide-open space connected to the three Gymnasiums. This open space, the Water Sports Complex, the three Gymnasiums and the Main Stadium with its Plaza were architectural landmarks of the masterplan designed for the 1998 Asian Games, and were subsequently integrated in TU’s Master planning for the campus, blending all the spaces with green corridors.

At the moment, the detailed layout of the area consists of a space divided in two sections: one is an open space pavement with limited green provision, separated from the road and bordering the commercial activities on the south, located outside the Complex, to the east; the other area is a space for cars, with parking lots surrounding a green roundabout which directs and organizes the traffic coming from the Sanya Dharmasakti Road. The project inputs provided by the stakeholder allows the repurposing of this space with a project that overwrites the existing layout with a new, more rational organization of the access lane, traffic and of the overall design of an inclusive and accessible park which follows the main conceptual key-points established in the first phase of the research (Selanon et al., 2022a).

5.2. Project Rationale.

As per the design documentation (Dejnirattisai, 2023), the main site-specific design concept is “Finding Unity Through Difference”. This guiding concept allows the designers to both maintain and yet integrate the “unity”- “difference” dichotomy in the conceptual and practical dimensions of the design, which were developed with the goal of establishing a public recreation area to enhance the quality of life while promoting good health for people with disabilities.

“Unity” and “difference” summarize the goal of creating a unique space where space users and passers-by can meet and gather, with ease of access, no divisions or barriers, and regardless of the presence or the level of disabilities which may affect a user of the space. The park strongly promotes the inclusion of an often-marginalized share of the society - the people with disabilities, who can see in this space a tangible help and support for the enjoyment of social life, of multi-sensorial green spaces and water bodies, of specific sportive, playful and recreational activities, regardless their disabilities.

From the physical point of view, “unity” and “difference” represent the guidelines for the definition of spatial layouts, materials, activities, furniture and landscape design’s solutions which compose the design of the park. These items are materialized here often in a triangular shape with rounded edges. This recurrent shape of the design is present in the main layout of the areas, in the finishing of the pavements, in the shape of “the mountain” and in other diverse elements. The triangle symbolizes the stability that many users of the park are looking for in the context (as per the survey), the certainty for the park to be a new element which can enrich the disabled users’ life, and a stable presence the users will be able to count on. The rounded edges symbolize the easy of park use by the users.

5.3. Project Features and Description.

The project connects itself seamlessly to the context, to the cyclo-pedestrian mobility, and to the aforementioned features surrounding the space (

Figure 5). The design has the main objective of repurposing this area into an inclusive park for people with disabilities that is reflected in the design of the park, with its inclusive and green features.

Given the nature of the project, a repurposing, great attention was given to mobility, circulation, and pedestrian security – themes particularly felt in the Thai context and in an area which can suffer from traffic congestion in the rush hour. Hence, the project includes also:

A redefinition of the vehicular traffic for the site, with a redesign of the car alley connecting the parking lots and the creation of a new drop on/off point on the south of the site;

A redesign of the access to the close-by parking lots, the creation of safe pedestrian crossings, highlighted by colored pavements directly connected to the park and to other sidewalks;

The creation of a service lane surrounding the Water Sport Complex;

The connection of the park with the TU Campus’ Shuttle EV-Bus stop.

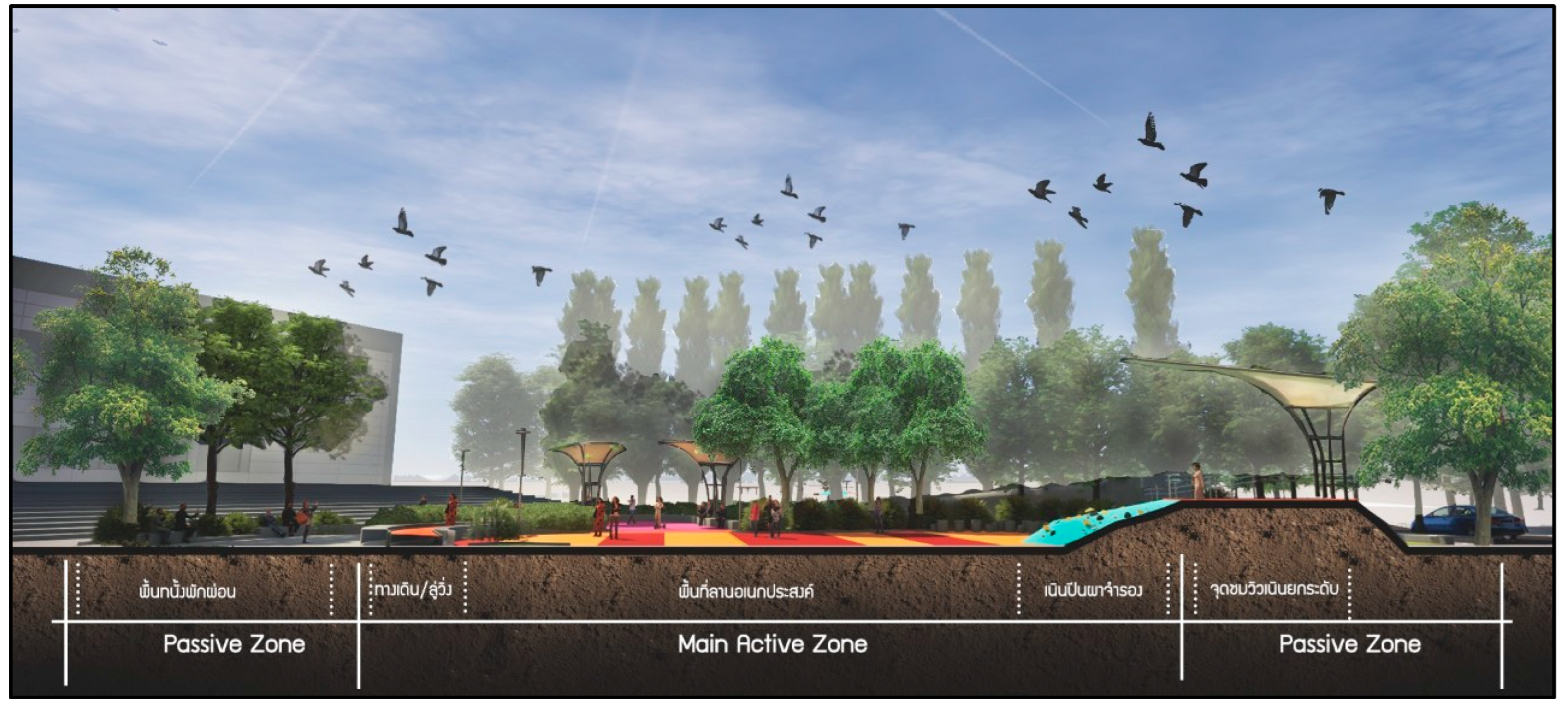

The park consists of a few main elements distributed in an asymmetrical layout: a green corridor running along the perimeter of the site; another inner ring of green; and a central area. The first two elements surround a central area, a quadrangular core subdivided into two triangular areas - a “main” and a “secondary” one.

The green corridor consists of new and existent trees, grass and bush, and a water body. Another inner ring runs parallel to the main triangular core and contains other trees and lawn, enclosed by flowerbeds. Their purpose, in accordance with the user consultation emerging from phase one of the research, the site-specific investigations and the contemporary literature on the topic (Selanon et al., 2022a; Selanon et al., 2022b) is to provide sensorial enjoyment and the pleasantness. Moreover, the physical layout of the trees encloses the area of the activities, providing a sense of visual enclosure and serving as a green barrier to absorb the sound and physically separate the safe area of the park from the surrounding campus and roadways.

The quadrangular core’s space is defined by the design criterion of “passive” and “active” zones, which subdivide the spaces (

Figure 6). The passive zones are related to the idea of the passive enjoyment of the green space: a sensorial enjoyment which does not imply exertion of physical exercise in the space. Seating, gathering, resting under the shaded zones, and relaxation are possible in the open spaces connected to these concepts. While seatings are mostly located on the northern edge of the main triangular core, alongside the concrete walls delimiting the green corridors and the water fountain, the whole design is characterized by a sequence of shaded and open spaces: five “flowers” of metal structure and texture covering provide shade and complete the design of the open spaces. The pavement is characterized by different colorations. This graphic support, to aid those who are partially sighted and to convey a general message of vibrancy, is paved with a soft layer of blended concrete and rubber which provides comfort and safety. The design additionally includes open green spaces freely accessible for multiple purposes.

In contrast, the “active” zones facilitate physical activities. Spaces for the structured active enjoyment of the space include fitness equipment and a basketball court in the northern and western portion of the park; a playground and a fitness area; the two connected elements of an artificial ground, and a walking lane which loops around the premises.

The fitness equipment consists of machines popular with active exercises, and that are specifically designed for disabled users. Similarly, the playground area is designed with equipment for adults that includes swings and seesaws to foster physical and sensory engagement and enjoyment. The active zone is located in the north-west area around the shading devices to guarantee rest and sun protection for the users. The area shares also the activity of basketball, with the installation of a half-court area, the positioning of which does not affect the other users. The basketball is a favorite in Thailand and the presence of the basket in an asymmetric context without the normal rectangular court dimension has the benefit of providing the idea of the game, stimulating the body and the brain. The rest of the area is general free non-shaded open space.

The artificial ground is a hill, 1.65 meters high, located on the eastern side of the area. It is reachable through the walking lane by the sides and through “the mountain” by the main open space and includes soft steep but walkable surface which contains devices for climbing. The walking lane extends alongside the perimeter of the main triangular core for a loop of 100 meters; it climbs the hill, and it is navigable by wheelchair, respecting the slope design criteria prescribed by the Thai regulations for the accessibility and the codified design (Harris & Dines, 1988).

The minimum width of 1.70 m allows the passage of more people or a combination of wheelchairs with people. Alongside its course, metal parapets protect the uses and are present active devices of activity. An anchoring device runs parallel to the path on a metal frame mounted at different heights. It allows the walkers with mobility or visual impairment to hold a moveable handle which can guide them in this path.

The unstructured active enjoyment zone is another important feature defining the spaces. It includes, as per the passive zones, the open spaces which allow free movements, walks, runs, and collective exercise by groups of users, in cooperation with the local stakeholders who can promote further interactions within the spaces. These spaces, by their nature, favor an informal gathering of users and social inclusion, allowing people to find new spaces to conduct social or other outdoor activities.

5.4. Social inclusion of the disabled people in the park with physical activities.

Whereas the park suggests and encourages sitting and passive enjoyment, generous attention was dedicated to the designing of recreational activities that can foster active social integration while promoting good health for people with disabilities. This principle is developed with two main principles: the one of the challenge and the other of the sensorial engagement.

The principle of the challenge, emerging from the interpretation of the studies conducted, consists of a balance of inclusive elements that leverages on accessible and controlled physical challenges. At the center of the northeast open space, the aforementioned artificial ground is created and paired with another solid element with a triangular base, the “mountain”. It is an artificial hill clad in soft rubber blend which allows and invites engagement through climbing. This element is constructed with a progressive slope and several anchor points designed to develop challenge and a sense of achievement.

In a similar way, the edge of the hill is designed to encourage the throw of a ball/weight from the top of the hill towards the square, in a shot-putting manner and targeting a specific angle which does not harm other visitors. It is possible to conduct this activity on the level of the square. The involvement of the same dual sense of engagement/challenge is amplified by the design of the floors: parallel lines with different color contrast and distance indicators allows the participants of the activity to measure the length of the throwing. In this sense, the design of the pavement with the color contrast and the parallel lines helps to identify the position of the thrown object. This opens up further possibilities of enjoyment and engagement, to be developed in the future daily operational routine of the park and in collaboration with sports experts, physiotherapists, and other personnel affiliated with the various Thammasat faculties who can be involved in activities that will aim to maximize positive health effects.

On the other hand, the topic of sensorial engagement can be enjoyed at the site in both active and passive forms. The park offers a wide variety of possibilities for the engagement of the senses with open space, natural ventilation, sun, water, and greenspace, elements capable of stimulating different sensorial sensations. The position of the park in between a cluster of sportive, recreational, and commercial activities facilitates spontaneous access, thereby enticing unplanned visits to the space. The presence of continuous seating, of generous greenspace, and of a water body with a fountain favors visitor aggregation, while concurrently providing opportunities for private and collective moments of sensorial engagement. For example, the open spaces can host active and reflective activities such as group-classes of mindfulness or meditation in a public space - a further experience of inclusion in the public context for people with different disabilities.

5.5. Green Landscape Design.

The design of green spaces warrants further elaboration. The greenspace was deemed as crucial by the designers in accordance with the TU Masterplan for a green campus and to provide real possibilities of sensorial engagement while being consistent with concepts of Nature-based Solutions. This empowerment of the greenspace design involves the maintenance of the existent trees with their relocation on the site and the plantation of 22 new trees of different arboreal species. Shrubs and grass are planted in the areas at the edge of the site to accomplish two additional goals other than the visual, sensorial and environmental ecosystem benefits. The first is the water collection: while an irrigation network supplies water in the dry season, permeable soils and water collection hubs facilitate the on-site collection of stormwater runoff and subsequent conveyance for treatment. The secondary goal is the protection and enclosing of the space for the activities. The water fountain is included to provide an element of variety, functioning as a sensorial and material point of engagement which creates a sensorial, acoustic, and visual landmark due to its position on the site, visible to the public road.

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 provide comprehensive rendered images of the park.

The next section discusses the limitations, points of convergence and divergence of the research insights coming from the surveys (as discussed in the

Section 4) and their reflection in the design process.

6. Discussion and Limitations of the Study

Beside the efforts of the design team to integrate and inform the provision of a new identity for a repurposed space, two critical limitations occurred in the process: one was related to the physical characteristics of the site and the surroundings, and the other to the qualitative principles of the insights received.

The main recurrent structural limit related to the physical characteristics of the site drove many choices in the design phase. The site’s surface of 2,334 sqm is large enough to accommodate a variety of functions and spaces, but it is inclusive of the vehicular mobility, emergency lane, pedestrian crossings and required greenspace, which have minimum sizes under the local laws and well-known international practices (Harris & Dines, 1988;). The designers decided not to disadvantage the mutual distancing and proportion among the elements, the greenspaces, and to keep the existent trees in spite of accommodating all the suggestions that emerged in the survey. The presence of the greenspaces could have been expanded, but only at the expense of the quantity of activities.

Another issue of the design phase was connected to the site positioning. The Water Center constitutes an iconic architecture and an existing hub both for the sportsman and the public given its sportive, commercial, and recreative appeal. The Complex is in need of renovation and restructuring, and needs universal design upgrades of some services, including the accessibility for wheelchairs, the position and the numbers of toilets. This indirectly affects the park, which needs to rely in the Complex’s toilets (accessible from the ground floor of the Complex) and with a poor general access to the swimming pool’s floor (accessible from the inside of the Complex) or by the iconic staircase, which is not suitable for those with mobility impairments.

Also, the new layout of the park and the roads separates the vehicular traffic completely from the Complex, creating a safe zone that is fully pedestrian (the surrounding lane is intended to be used for emergency use only). The drop-off area is moderately farther than the actual one, as the general circulation had been restructured, and it may cause confusion in the first operational stages if an adequate signaling system and traffic control are not provided.

Other limitations of the research process are bundled in the intrinsic nature of the survey and in the qualitative value of the insights. As mentioned, without prejudice to the methodological correctness of the survey and the elaboration of the results, the insights received were not connected to any specific site and therefore required site-specific adaptation. The choices the designers made adapted the survey inputs to the real physical constraints of the site. The design expression of the survey suggestions is summarized in the following

Table 3 and

Table 4, which represent a design distillation of information from

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Table 3 summarizes the implementation of the inputs received. It shows how every suggestion was or was not accommodated in the design, and providing a short rationale for the design decision. The suggestions were divided into 4 strands that emerged from the survey: active recreational items; passive recreational items; physical enjoyment activities; and complimentary activities.

From the

Table 3, it appears that no insights from the surveys had been fully excluded from the project. The designers accommodated the majority of the suggestions, tailoring these to the aforementioned site constraints. Most of the survey suggestions were related to generic activities with the designers opting to take them into account by providing flexible space and demanding the implementation of these activities by the relevant stakeholders under the management phase of the site once construction is completed.

Table 4 summarizes specific items that were suggested, and the 2 disability groups that most frequently demanded the item. In the last column of

Table 4, the rationale behind the choice is briefly explained, as per the previous

Table 3.

The designers were able to implement all the suggestions, except those requiring the edification of a new structure. In these two cases (pavilion and drink shop), the reason behind the designers’ choices is about the creation of an open space which excluded “walls” and constructions, dialoging with the immediate surroundings of the Water Sports Complex, and leveraging on the visual connections.

Further elaborations, considerations on the crossed connections between the specific disabilities and the activity requested fall beyond the scope of this article and the authors’ expertise, and can constitute a database for future specific studies on the subject coming from other disciplines.

We categorized another set of insights as “physical recommendations”. The majority of the recommendations falling under this class of survey results were included in the project since its conceptual phase: accessibility, gratuity, ease of use and access, separation from traffic, and safety from vehicles. Other requests involved more specific physical features, and all were taken into account: the installation of handrails, the presence of non-slippery and soft surfaces, sun shade protection, sitting areas, the provision of new trees and greenspace – interpreted also as a multisensory set of devices. The request of no level variations in the surfaces is partially taken into account, interpreted as an extra element which can be excluded from the park; it has materialized with the presence of the climbable “mountain”, connected to the ground with ramps.

The last set of suggestions received in the surveys were related to the presence of mobile devices such as sticks and crutches and wheelchairs on demand – rental, presence of balls of different weights and material for various exercises, presence of user-friendly devices, and presence of caretakers: these would be considered in the operational stage of the design, after the construction of the park. Potential space for accommodating the storage space could be identified in the Water Complex.

Taking everything into consideration, the design team actively pursued compromises between the survey group’s insights and design choices, highlighting the convergence points coming from the target use, rather than emphasizing the possible divergence points. For the authors, the result, besides the abovementioned limitations, satisfied the inputs received to the greatest extent possible.

7. Conclusion

This description of the research phase, of the design, and the discussion of the limitations provides three main conclusions for this research.

The features of the design, besides the inner limitations previously discussed, constitutes an satisfactory compromise between the target group’s insights and the site’s features. Designers act as an interpreter, translating the community insights into real spaces which empowers the minority and the vulnerable stakeholders. Furthermore, the provision of flexible, multi-use and non-predetermined open spaces is a further base for possible future collaborative bottom-up projects, or stakeholders’ collaborations. This research offered the base for more studies conducted also by other disciplines, in similar or comparable areas or with a similar methodologic approach, to investigate other related topics – i.e., the behavioral or medical sciences, as mentioned in regards of the future possibilities for research previously.

Secondly, we believe this kind of research through designing empowers the context because its foundations lay on the interpretation of the four factors of inequality in a proactive way, as specified in the Introduction. Specifically, as per the structural factors, the redevelopment of a park can lead to positive economic turnovers in the small scale and to a more inclusive political agenda by the local administrators, who will be able to count on an enrichment of public spaces. As per the social determinants and as described in the section 5, the layout of the areas, the presence of greenspace, sensorial features, passive and active spaces positively contribute in creating diverse occasions for improving the social engagement of the area. With respect to the risk factor, the renovated park offers to the society a public, free and protected space that empowers their active lifestyle and reduces negative behaviors from the users. Lastly, the nature of a free, public, open, inclusive, and accessible park can help the health system factor to establish the park as a gateway to a healthier lifestyle. In the future operational phases, the park is expected to incorporate collaborative activities connected to the health services in its open spaces.

Finally, we clearly illustrated the value of participation and inclusion. A space which suggests and encourages inclusion, social bonding, and social gathering, maximizing the autonomous accessibility by marginalized actors, reaches an importance which goes beyond its physical boundaries. As remarked previously (Selanon et al., 2022a; 2022b), with this repurposing, the role of a park and greenspace will be enriched and create a valuable precedent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S., F.P., and S.D.; methodology, P.S., F.D., and S.D; Writing, P.D. and F.P.; Review, P.S. and F.P.; editing, P.S. and F.P.; visualization, S.P. and A.R.; resource A.R.; funding acquisition, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received funding support from the NSRF via the Program Management Unit for Human Resources and Institutional Development, Research and Innovation [Grant number B05F640096] and supported by the Thammasat University Research Unit in Making of Place and Landscape, Thammasat University, Thailand.

Informed Consent Statement & Ethics statement

The Human Research Ethics Committee of Thammasat University: Social Sciences (Number 102/2564) approved this study. All participants and/or their legal guardians provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all participants who generously contributed to the present study, as well as all organizations that assisted in participant recruitment and assessment. The authors also wish to thank the research team and all the staff that were involved in this project for their help and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 |

Authors remark how this project described is related on real-life design procedures and approval process by the Thammasat University. At the moment of writing, it is in process of funding – a joint effort by the public and the private sectors. |

References

- American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) (2023). Universal Design: Parks and Plazas. Https://Www.Asla.Org/Universalparksandplazas.Aspx (accessed on 20th June 2022).

- Dejnirattisai, S., Selanon, P., Jetwaranyu, T., Rutchamart, A., Dechmak, I., Weerawittayasak, P., and Aiumpongpitoon, K. (2023). Design Documentation. Design documentation, Internal use, Thammasat University.

- Emerson, E., Fortune, N., Llewellyn, G., & Stancliffe, R. (2021). Loneliness, social support, social isolation and wellbeing among working age adults with and without disability: Cross-sectional study. Disability and Health Journal, 14(1), 100965. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Zúñiga, B., Pousada, M., & Armayones, M. (2023). Loneliness and disability: A systematic review of loneliness conceptualization and intervention strategies. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.W., Dines, N.T. (Eds.). (1988). Time-saver standards for landscape architecture: design and construction data. McGraw-Hill.

- International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). (2001). 2023/1 update. Retrieved https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 14th July 2022).

- Irvine, K.N., H.H. Loc, C. Sovann, A. Suwanarit, F. Likitswat, R. Jindal, T. Koottatep, J. Gaut, L.H.C. Chua, WQ Lai, and K. De Wandeler, 2021. Bridging the form and function gap in urban green space design through environmental systems modeling. Journal of Water Management Modeling, 29: C476. [CrossRef]

- Lenzholzer, S., Duchhart, I., & Koh, J. (2013). ‘Research through designing’in landscape architecture. Landscape and Urban Planning, 113, 120-127. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Social Development and Human Security (2012). Types of Disabilities. Retrieved http://web1.dep.go.th/sites/default/files/files/law/185.pdf.

- Singh, Japjot (2023). Inclusive Public Parks for Cross-Cultural Community Participation. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/incd2021/part/inclusive-public-parks-for-cross-cultural-community-participation-japjot-singh/.

- Selanon P, Puggioni F, Dejnirattisai S and Rutchamart A. 2022a. Towards inclusive and accessible parks in Pathum Thani Province, Thailand. City, Territory and Architecture (2022) 9:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-022-00169-y. [CrossRef]

- Selanon P, Puggioni F, Dejnirattisai S, Sapsangthong A and Rutchamart A. 2022b. Building a Suitability Scoring System for the Redevelopment of an Existing Park into an Inclusive Park for Disabled: Case Studies from Pathum Thani, Thailand. Thammasat Review (2022) 2:25 (218-253). https://doi.org/10.14456/tureview.2022.19. [CrossRef]

- United Nations - Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Social Inclusion (UN-DESA). (n./d., a). “Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) And Disability”. Retrieved from https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/sustainable-development-goals-sdgs-and-disability (accessed on 1st August 2022).

- United Nations (UN). (2015). Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development - A/RES/70/1 2030 https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf.

- United Nations (UN). (2020). The United Nations Disability Inclusion Strategy. https://www.un.org/en/content/disabilitystrategy/assets/documentation/UN_Disability_Inclusion_Strategy_english.pdf.

- World Health Organization (WHO) & The World Bank, World Report on Disability, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011, available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-report-on-disability (accessed on 2nd July 2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Regional Office for Europe. (2019). Disability: fact sheet on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): health targets. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/340894.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Policy on Disability. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022a). Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063600 (accessed on 2nd July 2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022b). Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities: executive summary. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063624.

- UN Disability Inclusion Strategy (2006). https://www.un.org/en/content/disabilitystrategy/assets/documentation/UN_Disability_Inclusion_Strategy_english.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).