Submitted:

20 October 2023

Posted:

20 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

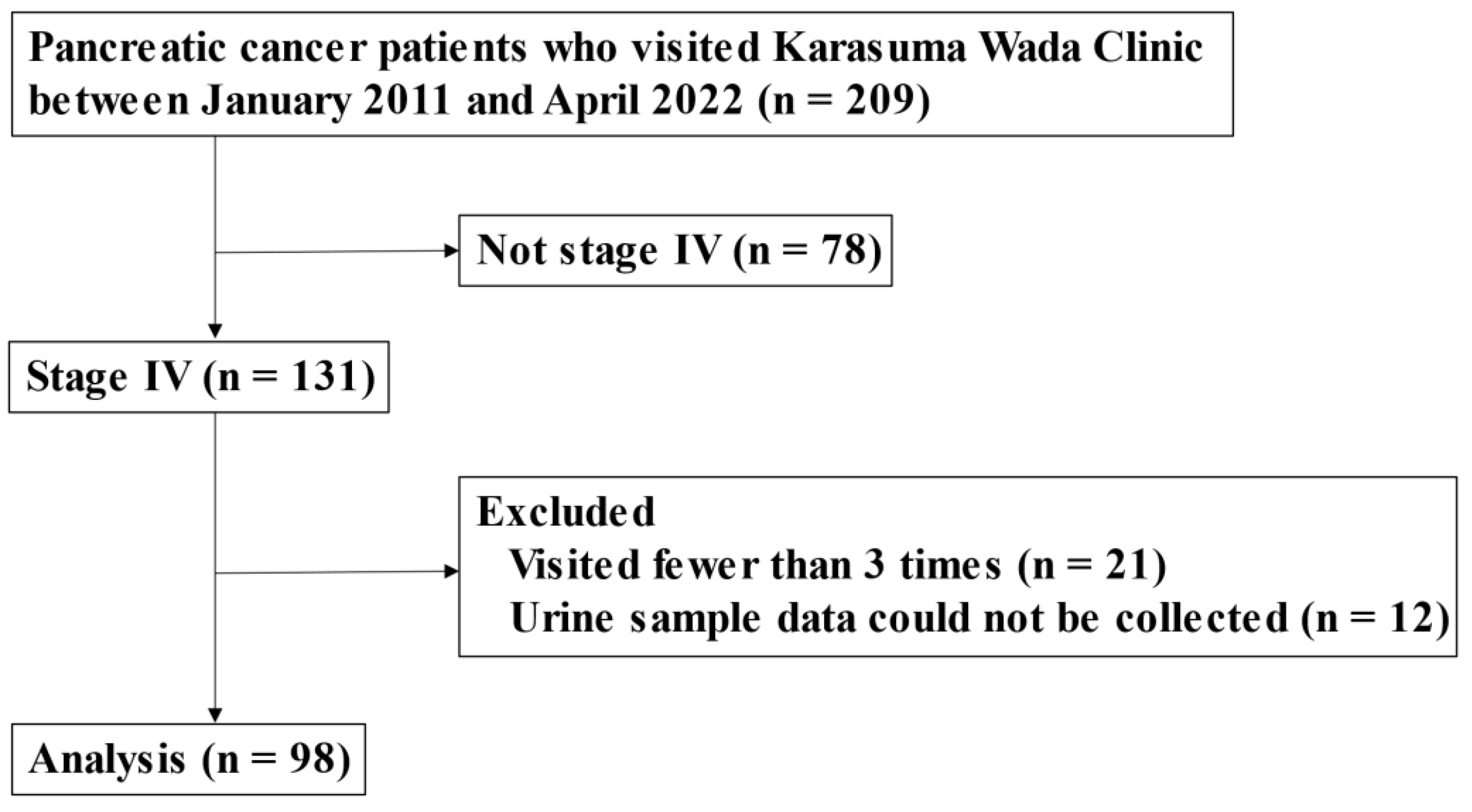

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Alkalization Therapy

2.3. Assessment Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

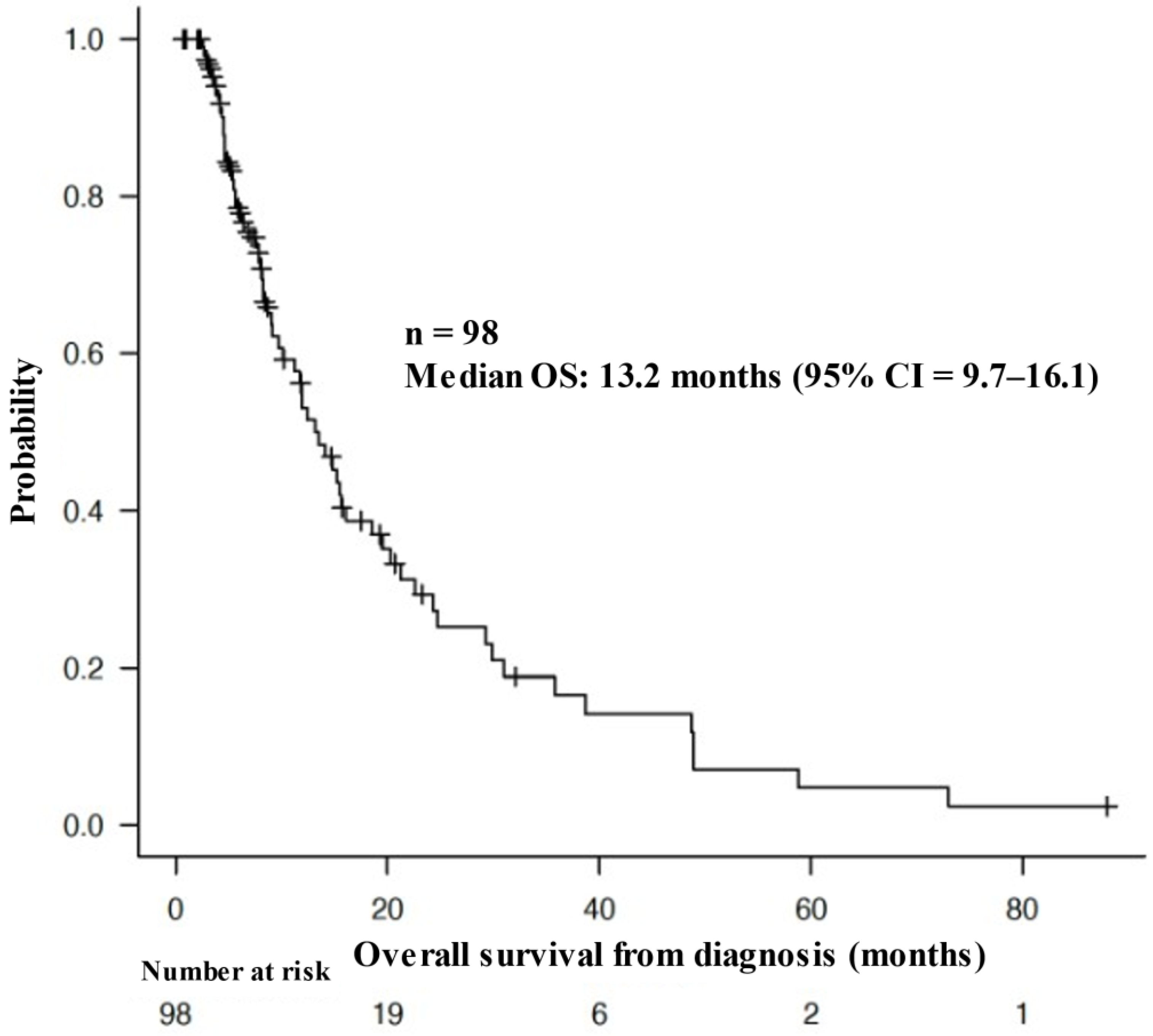

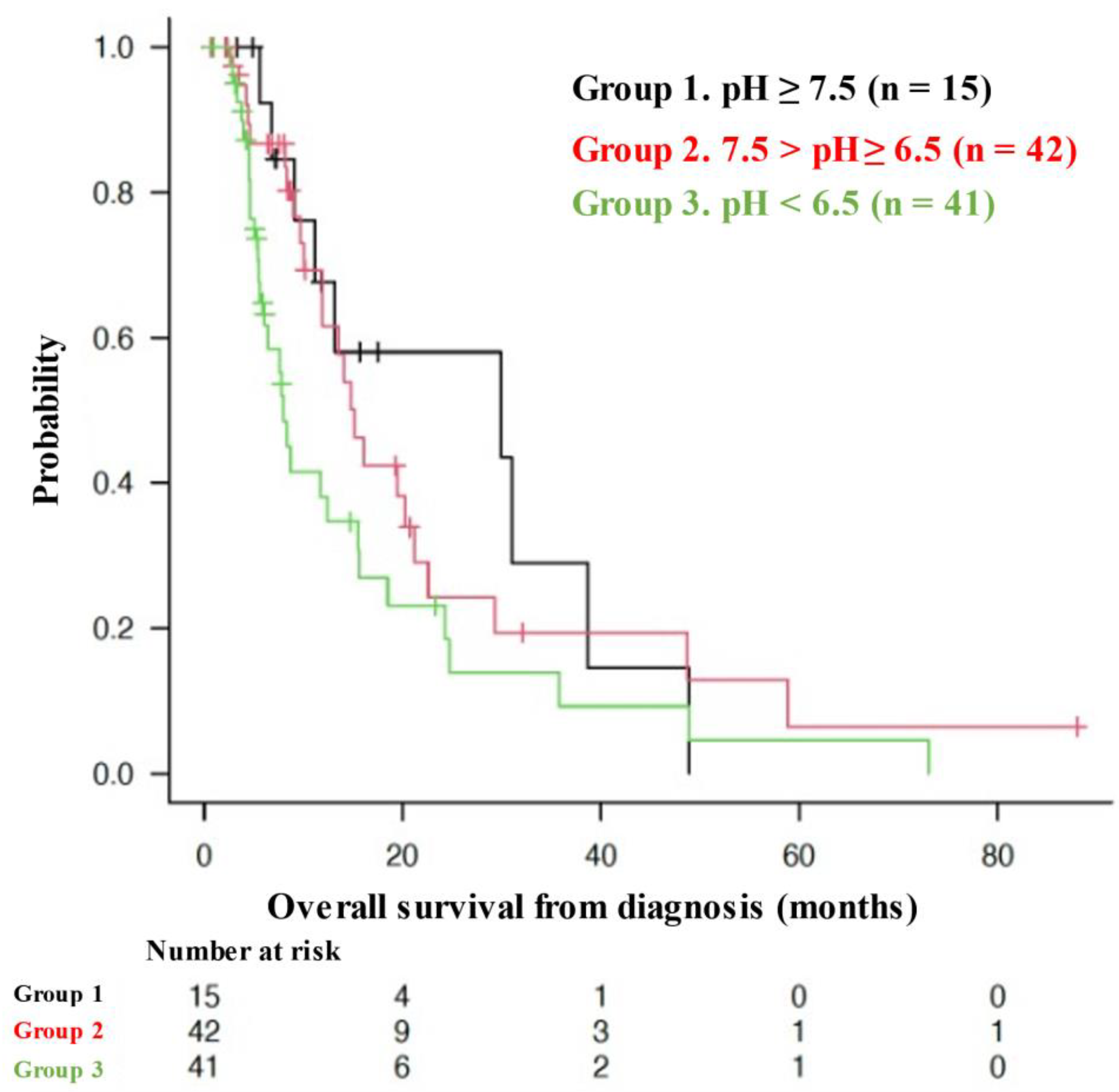

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. OS of Patients with Different Urine pHs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan - Survival 2009-2011 report (Center for Cancer Control and Information Services, National Cancer Center, 2020) [Japanese]. 2009-2011.

- Corbet, C.; Feron, O. Tumour acidosis: From the passenger to the driver's seat. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppenol, W.H.; Bounds, P.L.; Dang, C.V. Otto Warburg's contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neri, D.; Supuran, C.T. Interfering with pH regulation in tumours as a therapeutic strategy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011, 10, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamaguchi, R.; Okamoto, T.; Sato, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Wada, H. Effects of an Alkaline Diet on EGFR-TKI Therapy in EGFR Mutation-positive NSCLC. Anticancer. Res. 2017, 37, 5141–5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robey, I.F.; Lopez, A.M.; Roe, D.J. Safety and Tolerability of Long-Term Sodium Bicarbonate Consumption in Cancer Care. J. Integr. Oncol. 2015, 4, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, H.; Eshima, K.; Ishida, T. Neutralization of Acidic Tumor Microenvironment (TME) with Daily Oral Dosing of Sodium Potassium Citrate (K/Na Citrate) Increases Therapeutic Effect of Anti-cancer Agent in Pancreatic Cancer Xenograft Mice Model. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 44, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, H.; Hamaguchi, R.; Narui, R.; Morikawa, H. Meaning and Significance of "Alkalization Therapy for Cancer". Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 920843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi, R.; Narui, R.; Morikawa, H.; Wada, H. Improved Chemotherapy Outcomes of Patients With Small-cell Lung Cancer Treated With Combined Alkalization Therapy and Intravenous Vitamin C. Cancer Diagn. Progn. 2021, 1, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi, R.; Ito, T.; Narui, R.; Morikawa, H.; Uemoto, S.; Wada, H. Effects of Alkalization Therapy on Chemotherapy Outcomes in Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. In Vivo 2020, 34, 2623–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isowa, M.; Hamaguchi, R.; Narui, R.; Morikawa, H.; Wada, H. Effects of alkalization therapy on hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective study. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1179049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software 'EZR' for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.P. Pancreatic cancer epidemiology: Understanding the role of lifestyle and inherited risk factors. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kommalapati, A.; Tella, S.H.; Goyal, G.; Ma, W.W.; Mahipal, A. Contemporary Management of Localized Resectable Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleeff, J.; Korc, M.; Apte, M.; La Vecchia, C.; Johnson, C.D.; Biankin, A.V.; Neale, R.E.; Tempero, M.; Tuveson, D.A.; Hruban, R.H.; et al. Pancreatic cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamaguchi, R.; Isowa, M.; Narui, R.; Morikawa, H.; Wada, H. Clinical review of alkalization therapy in cancer treatment. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1003588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi, R.; Uemoto, S.; Wada, H. Editorial: The impact of alkalizing the acidic tumor microenvironment to improve efficacy of cancer treatment. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1223025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi, R.; Narui, R.; Wada, H. Effects of Alkalization Therapy on Chemotherapy Outcomes in Metastatic or Recurrent Pancreatic Cancer. Anticancer. Res. 2020, 40, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatenby, R.A.; Gillies, R.J. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardone, R.A.; Casavola, V.; Reshkin, S.J. The role of disturbed pH dynamics and the Na+/H+ exchanger in metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, R.A.; Harris, I.S.; Mak, T.W. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.J.; Raghunand, N.; Garcia-Martin, M.L.; Gatenby, R.A. pH imaging. A review of pH measurement methods and applications in cancers. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 2004, 23, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillies, R.J.; Raghunand, N.; Karczmar, G.S.; Bhujwalla, Z.M. MRI of the tumor microenvironment. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2002, 16, 430–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmlinger, G.; Yuan, F.; Dellian, M.; Jain, R.K. Interstitial pH and pO2 gradients in solid tumors in vivo: High-resolution measurements reveal a lack of correlation. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, F.A.; Kettunen, M.I.; Day, S.E.; Hu, D.E.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H.; Zandt, R.; Jensen, P.R.; Karlsson, M.; Golman, K.; Lerche, M.H.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of pH in vivo using hyperpolarized 13C-labelled bicarbonate. Nature 2008, 453, 940–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A.; Chubenko, V.; Volkov, N.; Moiseenko, F.; Moiseyenko, V. Tumor acidity: From hallmark of cancer to target of treatment. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 979154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillies, R.J.; Ibrahim-Hashim, A.; Ordway, B.; Gatenby, R.A. Back to basic: Trials and tribulations of alkalizing agents in cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 981718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okusaka, T.; Nakamura, M.; Yoshida, M.; Kitano, M.; Ito, Y.; Mizuno, N.; Hanada, K.; Ozaka, M.; Morizane, C.; Takeyama, Y.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pancreatic Cancer 2022 from the Japan Pancreas Society: A synopsis. Int J Clin Oncol 2023, 28, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaka, M.; Ishii, H.; Sato, T.; Ueno, M.; Ikeda, M.; Uesugi, K.; Sata, N.; Miyashita, K.; Mizuno, N.; Tsuji, K.; et al. A phase II study of modified FOLFIRINOX for chemotherapy-naïve patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2018, 81, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, H.; Ikeda, M.; Ueno, M.; Mizuno, N.; Ioka, T.; Omuro, Y.; Nakajima, T.E.; Furuse, J. Phase I/II study of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for chemotherapy-naive Japanese patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2016, 77, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).