Submitted:

24 October 2023

Posted:

24 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

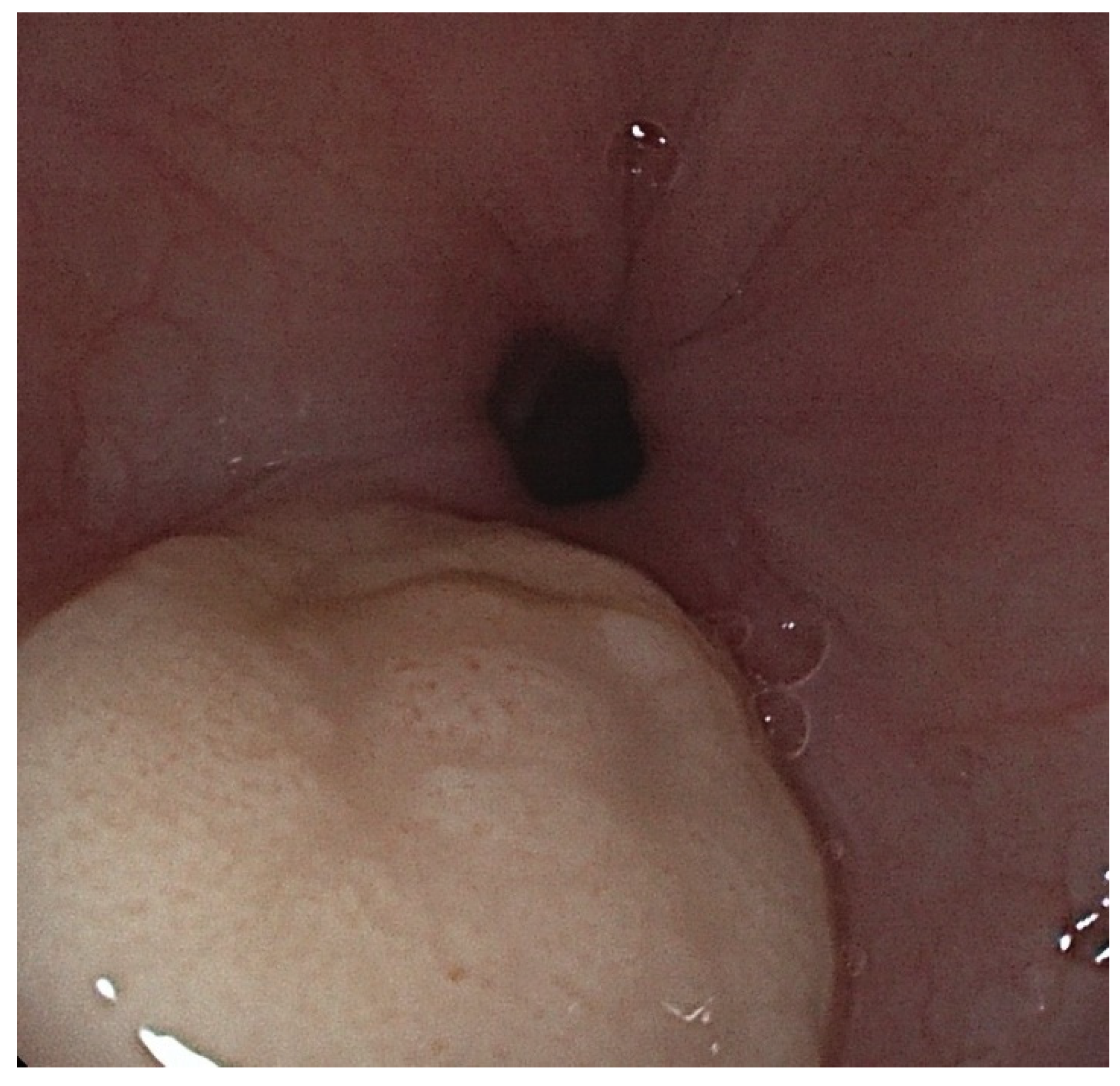

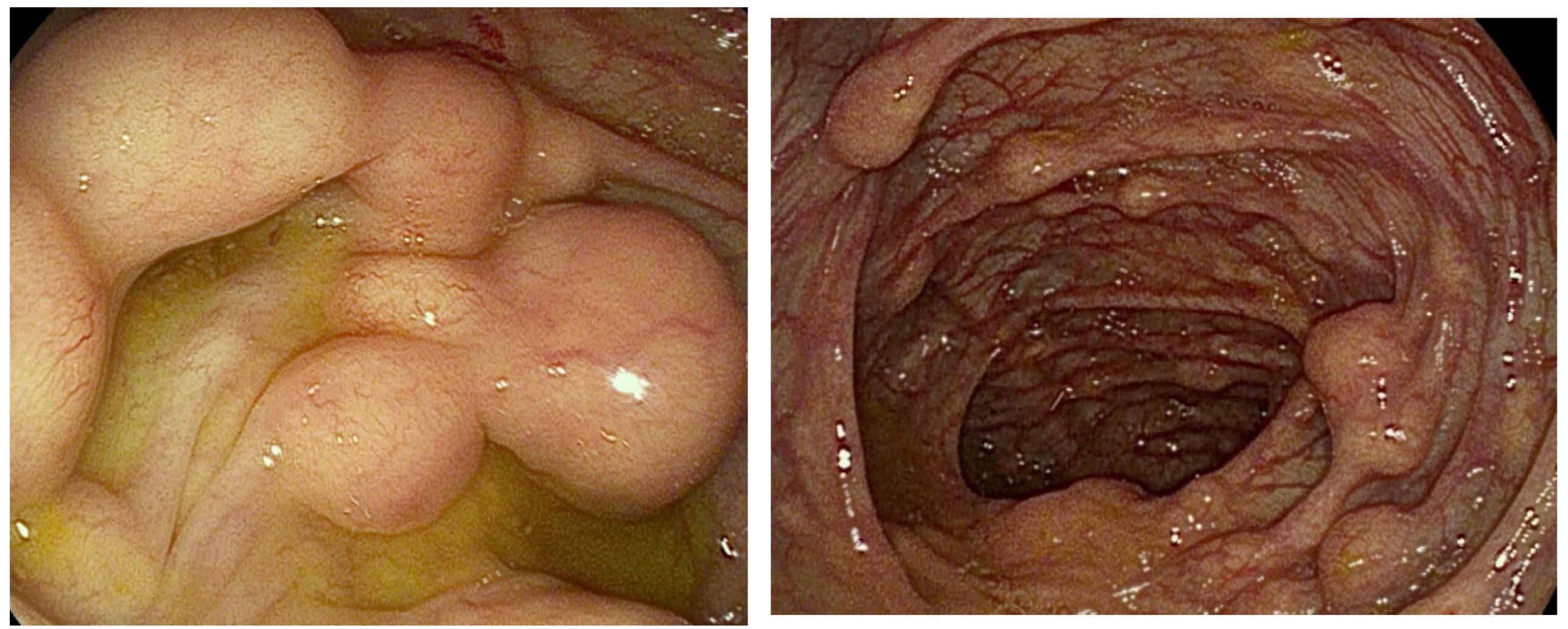

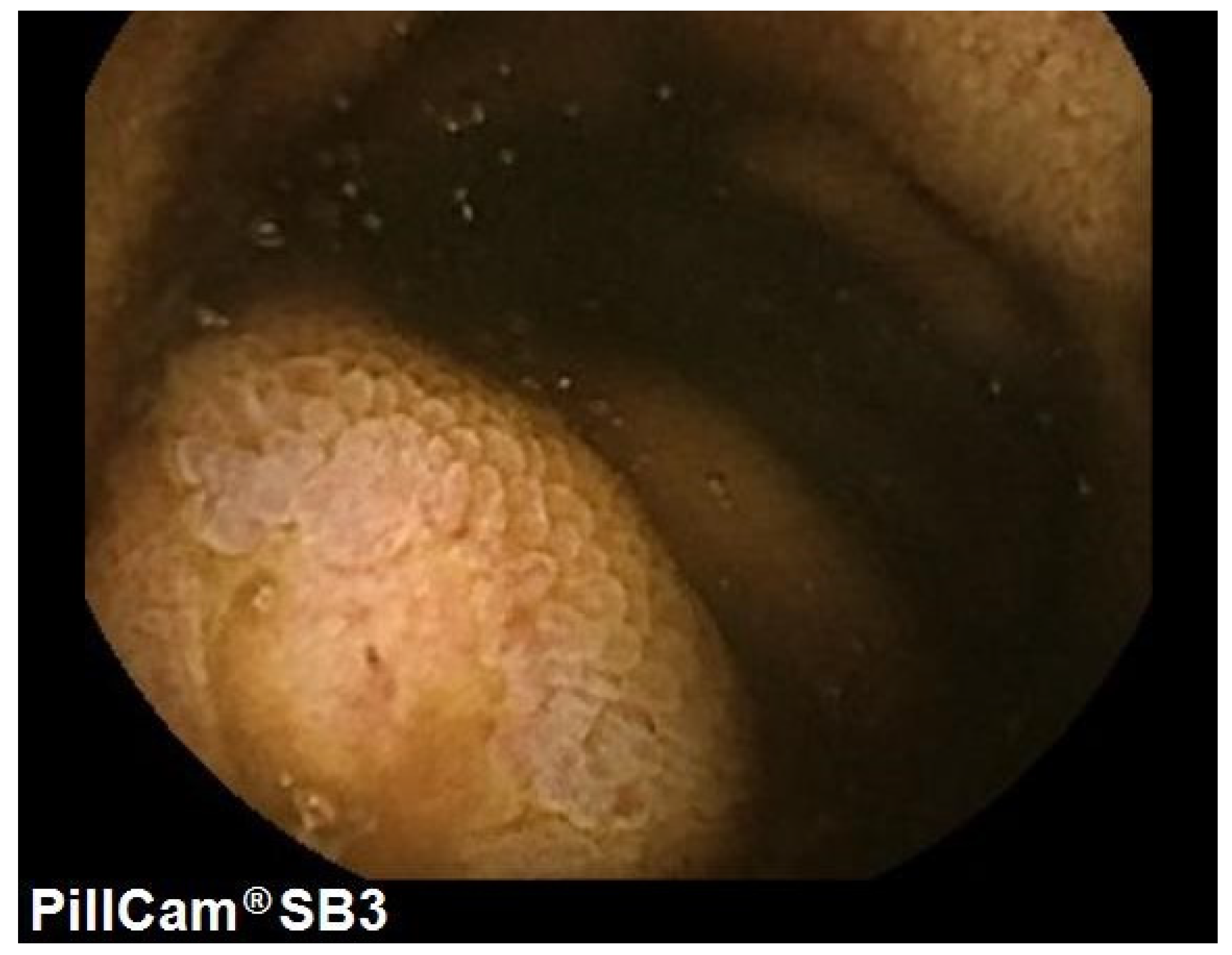

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stefansson, K.; Wollmann, R.L. S-100 protein in granular cell tumors (granular cell myoblastomas). Cancer 1982, 49, 1834–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.O.; Virchow, R. Anatomische Untersuchung einer hypertrophischen Zunge nebst Bemerkungen über die Neubildung quergestreifter Muskelfasern. Archiv für Pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für Klinische Medicin 1854, 7, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrikossoff, A. Über Myome. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat Physiol Klin Med 1926, 260, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, J.I.; Kim, H.J.; Jung, J.J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.S.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Granular cell tumours of the colorectum: histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation of 30 cases. Histopathology 2014, 65, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, S.; Aryanian, Z.; Ebrahimi, Z.; Kamyab-Hesari, K.; Mahmoudi, H.; Alizadeh, N.; et al. Cutaneous granular cell tumor: A case series, review, and update. J Family Med Prim Care 2022, 11, 6955–6958. [Google Scholar]

- Salaouatchi, M.T.; De Breucker, S.; Rouvière, H.; Lesage, V.; Rocq LJA, Vandergheynst, F. ; et al. A Rare Case of a Metastatic Malignant Abrikossoff Tumor. Case Rep Oncol. 2021, 14, 1868–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavesi, A.; Berrueta, J.; Pillajo, S.; Gaggero, P.; Olano, C. Endoscopic resection of a granular cell tumor (Abrikossoff’s tumor) in the esophagus using cap-assisted band ligation. Endoscopy. 2023, 55 (Suppl. 1), E796–E797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vincentis, F.; Manzi, I.; Di Giorgio, V.; Mussetto, A. Endoscopic full-thickness resection of a residual scar in ascending colon to assess post-EMR complete removal of an Abrikossoff tumor. Dig Liver Dis 2023, 55, 985–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Loo, S.; Thunnissen, E.; Postmus, P.; van der Waal, I. Granular cell tumor of the oral cavity; a case series including a case of metachronous occurrence in the tongue and the lung. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2015, 20, e30–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Su, J.; Liang, X.; Wu, J.; Gu, W.; Zhao, X. Clinical and pathological analysis of congenital granular cell tumor. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2022, 40, 710–715. [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt, J.R.; McLean, C.A.; Joseph, M.G.; Streutker, C.J.; Al-Haddad, S.; Driman, D.K. Granular cell tumours of the gastrointestinal tract: expression of nestin and clinicopathological evaluation of 11 patients. Histopathology 2006, 48, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanburg-Smith, J.C.; Meis-Kindblom, J.M.; Fante, R.; Kindblom, L.G. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol 1998, 22, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menaker, G.M.; Sanger, J.R. Granular Cell Tumor of Uncertain Malignant Potential. Ann Plast Surg 1997, 38, 658–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Jang, J.; Min, K.; Kim, M.S.; Park, H.; Park, Y.S.; et al. Granular cell tumor of the gastrointestinal tract: histologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 98 cases. Hum Pathol 2015, 46, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, A.; Satoh, K.; Hirota, M.; Hamada, S.; Umino, J.; Itoh, H.; et al. Granular cell tumor of the pancreas: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2010, 2, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, D.J.; Klapper, E.; Gordon, L.A.; Silberman, A.W. Granular cell tumor of the biliary system. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1994, 23, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Sun, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, G. Granular cell tumor of the appendix: a case report and literature review. Journal of International Medical Research 2022, 50, 030006052211093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen W shu, Zheng X ling, Jin, L. ; Pan X jie, Ye M fan. Novel diagnosis and treatment of esophageal granular cell tumor: report of 14 cases and review of the literature. Ann Thorac Surg 2014, 97, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deprez, P.H.; Moons LMG, OʼToole, D. ; Gincul, R.; Seicean, A.; Pimentel-Nunes, P.; et al. Endoscopic management of subepithelial lesions including neuroendocrine neoplasms: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy 2022, 54, 412–429. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, G.; Rampado, S.; Bocus, P.; Guido, E.; Portale, G.; Ancona, E. Single-band mucosectomy for granular cell tumor of the esophagus: safe and easy technique. Surg Endosc 2006, 20, 1296–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrmann, T.; Martchenko, K.; Nakamura, M.; Riphaus, A.; Stergiou, N. Endoscopic Resection of Submucosal Esophageal Tumors: A Prospective Case Series. Endoscopy 2004, 36, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, H.; Suga, M.; Ozeki, I.; Kobayashi, T.; Sugaya, T.; Sasaki, Y.; et al. Subcapsular hematoma of the liver and pylethrombosis in the setting of cholestatic liver injury. J Gastroenterol [Internet] 1996, 31, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavesi, A.; Berrueta, J.; Pillajo, S.; Gaggero, P.; Olano, C. Endoscopic resection of a granular cell tumor (Abrikossoff’s tumor) in the esophagus using cap-assisted band ligation. Endoscopy. 2023, 55 (Suppl. 1), E796–E797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, N.; Katzka, D.A.; Smyrk, T.C.; Wang, K.K.; Topazian, M. Endoscopic diagnosis and resection of esophageal granular cell tumors. Diseases of the Esophagus 2011, 24, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscay, M.; Chabrun, E.; Menguy, S.; Cesbron-Métivier, E.; Barthet, M.; Marty, M.; et al. Colonic Abrikossoff tumor: fortuitous discovery at colonoscopy for serrated adenomas polyposis, and resection by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy 2019, 51, E176–E178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utzeri, E.; Jacques, J.; Charissoux, A.; Rivory, J.; Legros, R.; Ponchon, T.; et al. Traction strategy with clips and rubber band allows complete en bloc endoscopic submucosal dissection of laterally spreading tumors invading the appendix. Endoscopy 2017, 49, 820–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Xu, M.D.; Zhou, P.H.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Chen, W.F.; Zhong, Y.S.; et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of esophageal granular cell tumor. World J Surg Oncol. 2014, 12, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, F.; Bernieh, A.; Saad, A.G. Esophageal Granular Cell Tumor in Children: A Clinicopathologic Study of 11 Cases and Review of the Literature. Am J Clin Pathol 2023, 160, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffle, M.E.; Polydorides, A.D.; Niakan, J.; Chehade, M. Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Esophageal Granular Cell Tumor. American Journal of Surgical Pathology 2017, 41, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddi, D.; Chandler, C.; Cardona, D.; Schild, M.; Westerhoff, M.; McMullen, E.; et al. Esophageal granular cell tumor and eosinophils: a multicenter experience. Diagn Pathol 2021, 16, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareja, F.; Brandes, A.H.; Basili, T.; Selenica, P.; Geyer, F.C.; Fan, D.; et al. Loss-of-function mutations in ATP6AP1 and ATP6AP2 in granular cell tumors. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castagna, J.; Clerc, J.; Dupond, A.S.; Laresche, C. Tumeurs à cellules granuleuses multiples chez un enfant atteint d’un syndrome de Noonan compliqué de leucémie myélomonocytaire juvénile. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2017, 144, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinreb, I.; Bray, P.; Ghazarian, D. Plexiform intraneural granular cell tumour of a digital cutaneous sensory nerve. J Clin Pathol 2007, 60, 725–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrader, K.; Nelson, T.; De Luca, A.; Huntsman, D.; McGillivray, B. Multiple granular cell tumors are an associated feature of LEOPARD syndrome caused by mutation in PTPN11. Clin Genet 2009, 75, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).