Submitted:

19 October 2023

Posted:

24 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Results for Lee Carter Model

3.1.1. Time index

3.1.2. Forecasted

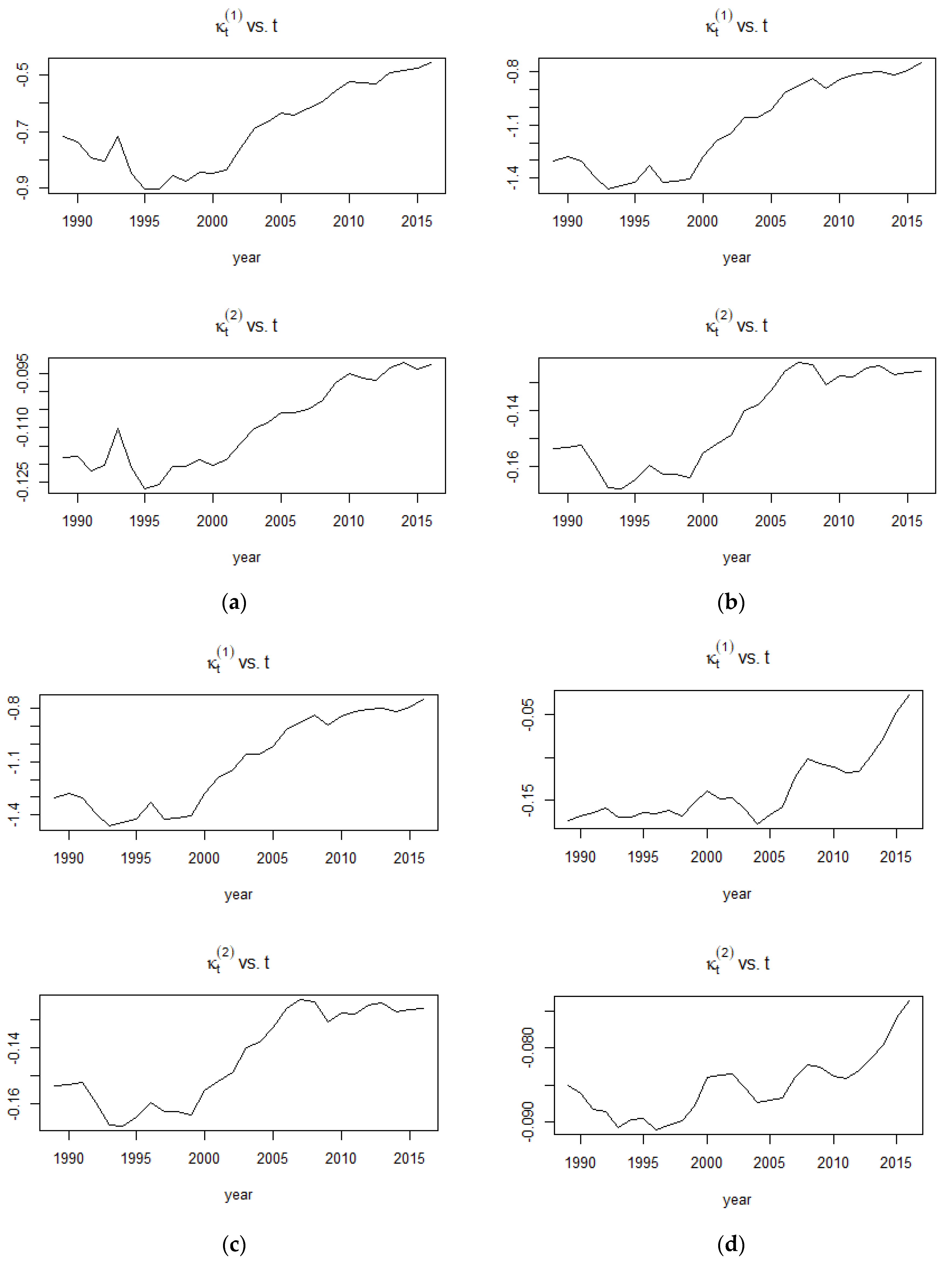

3.2. Results for Cairns-Blake-Dowd Model

3.2.1. Time index

3.2.2. Forecasted

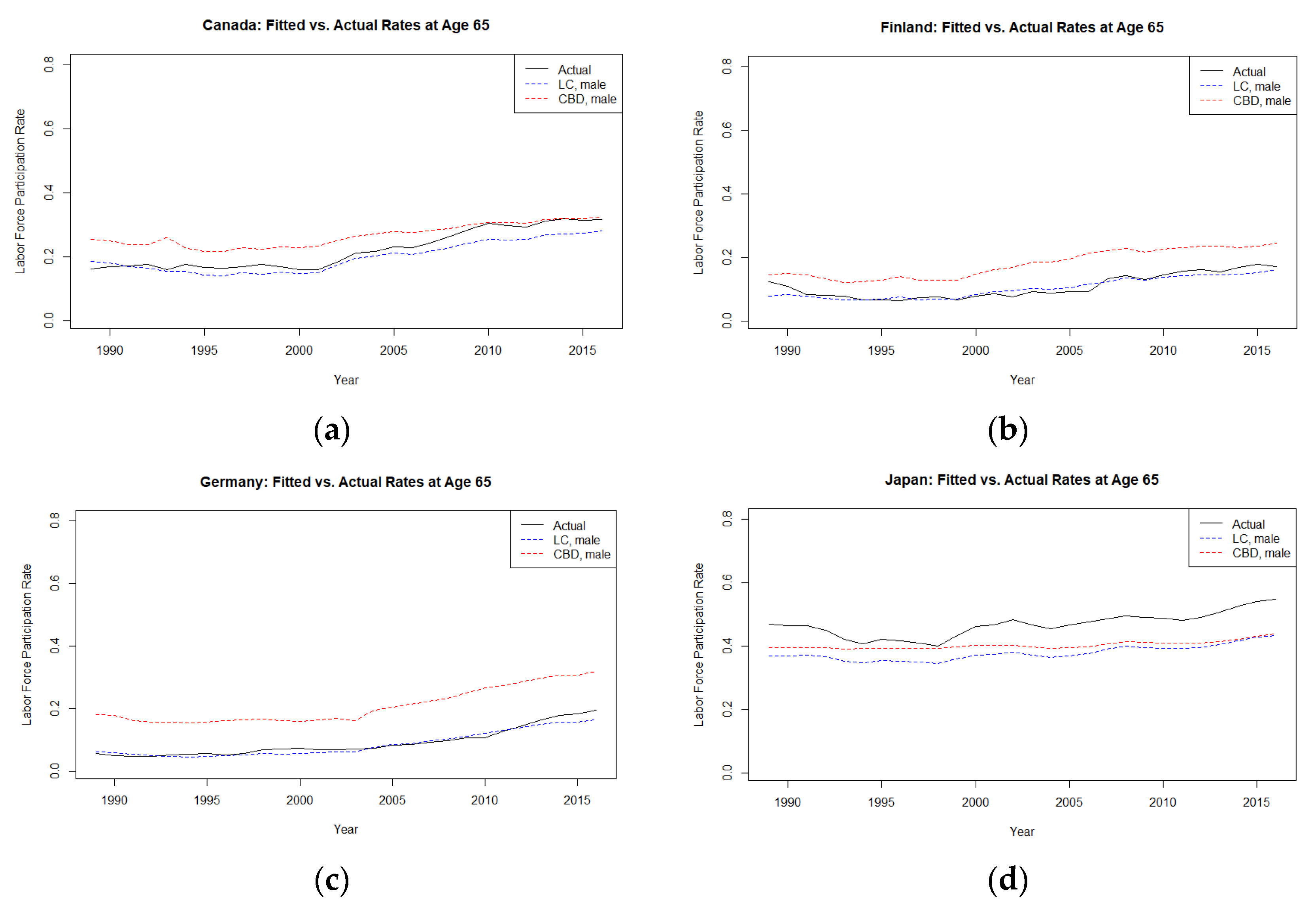

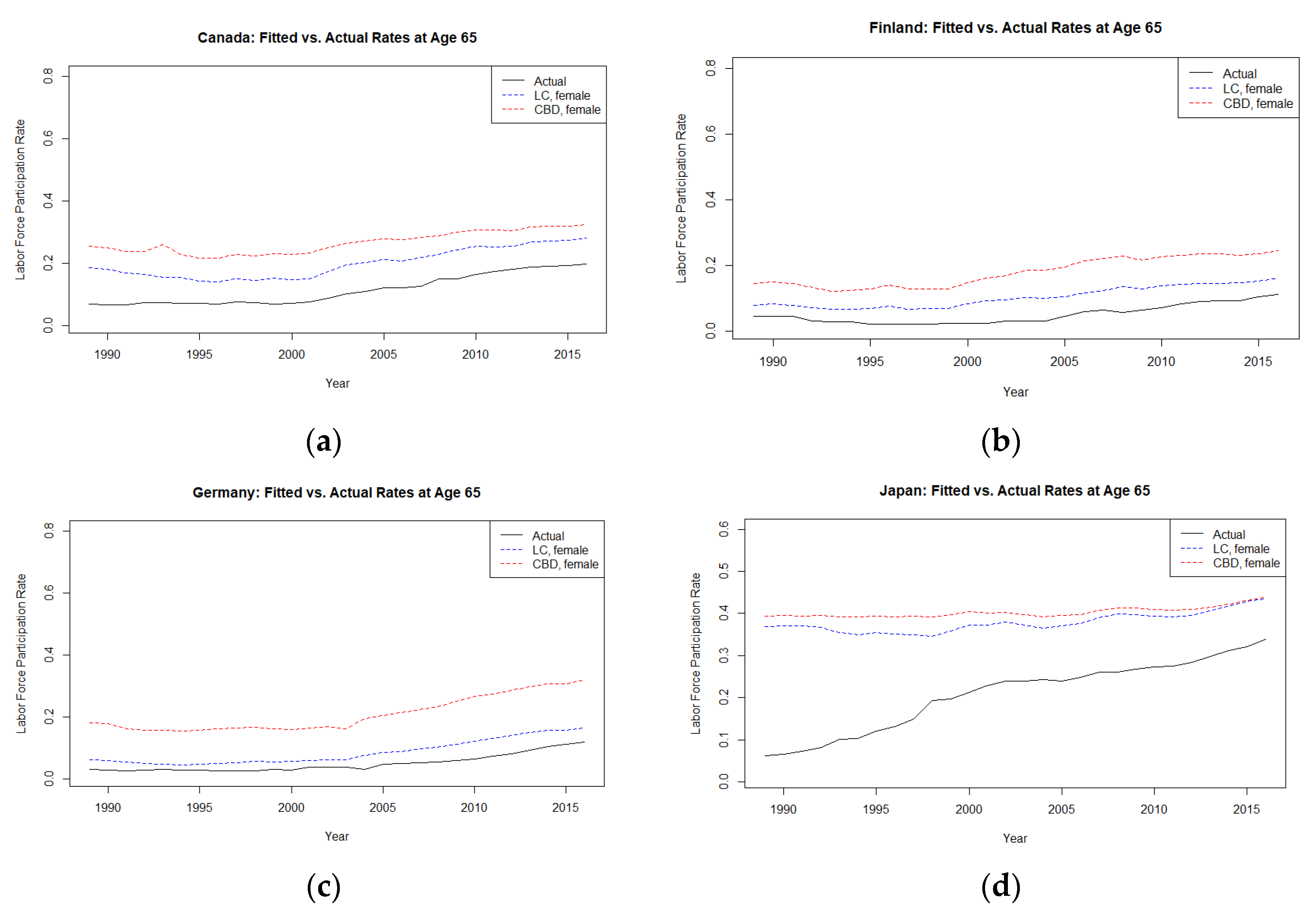

3.3. Labor Force Participation (LFP) rate

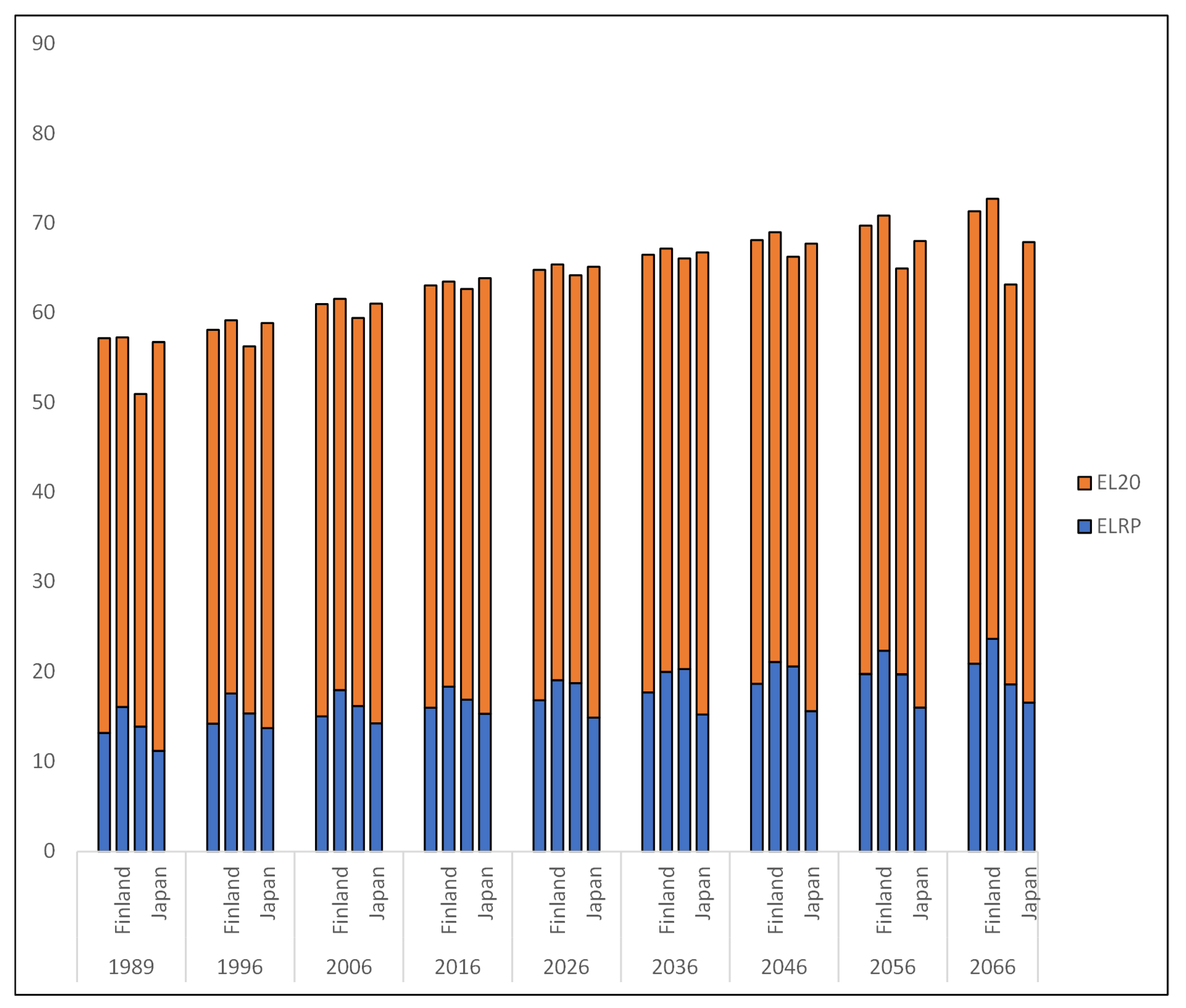

3.4. Duration of retirement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Felstead, A. Closing the age gap? Age, skills and the experience of work in Great Britain. Ageing Soc. 2010, 30, 1293–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomik, R.; McDonald, P.; Piggott, J. Population ageing in Asia and the Pacific: Dependency metrics for policy. J. Econ. Ageing 2016, 8, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louria, D.B. Extraordinary Longevity: Individual and Societal Issues. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, S317–S319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felstead, A. Closing the age gap? Age, skills and the experience of work in Great Britain. Ageing Soc. 2010, 30, 1293–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloostermans, L.; Bekkers, M.B.; Uiters, E.; Proper, K.I. The effectiveness of interventions for ageing workers on (early) retirement, work ability and productivity: a systematic review. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Heal. 2015, 88, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thang, L.L. Population aging, older workers and productivity issues: the case of Singapore. J. Comp. Soc. Welf. 2011, 27, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dalen, H.P.; Henkens, K.; Schippers, J. Productivity of Older Workers: Perceptions of Employers and Employees. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2010, 36, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szinovacz, M.E. Introduction: The Aging Workforce: Challenges for Societies, Employers, and Older Workers. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2011, 23, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjursell, C.; Nystedt, P.; Björklund, A.; Sternäng, O. Education level explains participation in work and education later in life. Educ. Gerontol. 2017, 43, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonin, H. 15 Years of Pension Reform in Germany: Old Successes and New Threats. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. - Issues Pr. 2009, 34, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukawa, T. Japanese Welfare State Reforms in the 1990s and Beyond: How Japan is Similar to and Different from Germany. Vierteljahr. zur Wirtsch. 2001, 70, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyyrä, T. Early Retirement Policy in the Presence of Competing Exit Pathways: Evidence from Pension Reforms in Finland. Economica 2015, 82, 46–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. A. Spedicato and G. P. Clemente, “Mortality projection with demography and lifecontingencies packages,” no. 2013, 2013, [Online]. Available: https://cran.r–project.org/web/packages/lifecontingencies/vignettes/mortality_projection.pdf.

- Dey, I. Wearing Out the Work Ethic: Population Ageing, Fertility and Work–Life Balance. J. Soc. Policy 2006, 35, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelle, N. Combining employment and care-giving: how differing care intensities influence employment patterns among middle-aged women in Germany. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 925–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyberaki, A. Migrant Women, Care Work, and Women's Employment in Greece. Fem. Econ. 2011, 17, 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Arimura, S.; Nakanishi, A.; Shimo, Y.; Motoi, Y.; Ishiguro, K.; Murakami, K.; Hattori, N.; Aoki, S. Age-related effects and gender differences in Japanese healthy controls for [123I] FP-CIT SPECT. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2017, 31, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. M. Manansala, D. G. M. Manansala, D. V Jan Marquez, and M. L. Antoinette Rosete, “Journal of Economics, Finance and Accounting Studies Social Security On Labor Markets to Address the Aging Population in Selected ASEAN Countries,” 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. S. Khan, “Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Studies Factors Affecting Labor Force Participation Decision in Bangladesh: An Empirical Study Using Microdata,” 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Maestas and J. Zissimopoulos, “W O R K I N G P A P E R How Longer Work Lives Ease the Crunch of Population Aging,” 2009. [Online]. Available: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1526761Electroniccopyavailableat:https://ssrn. 1526.

- Vanella, P.; Wilke, C.B.; Söhnlein, D. Prevalence and Economic Costs of Absenteeism in an Aging Population—A Quasi-Stochastic Projection for Germany. Forecasting 2022, 4, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, B.L.; Ferreira, M.L.A. The evolution of labor force participation and the expected length of retirement in Brazil. J. Econ. Ageing 2021, 18, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobotenko, M.I.; Nevecherya, A.P. Forecasting the labor force dynamics in a multisectoral labor market. Comput. Res. Model. 2021, 13, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, J.; Söhnlein, D.; Weber, B.; Weber, E. Stochastic Forecasting of Labor Supply and Population: An Integrated Model. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2018, 37, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, P.; Hotchkiss, J.L.; Terry, E. Evolution of Behavior, Uncertainty, and the Difficulty of Predicting Labor Force Participation. Bus. Econ. Res. 2019, 9, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajar, M.; Fajariyanto, E. LEE-CARTER MODELING FOR MORTALITY IN INDONESIA WITH A BAYESIAN APPROACH. BAREKENG: J. Ilmu Mat. dan Ter. 2022, 16, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo, J.O. Deep Learning Incorporated Bühlmann Credibility in the Modified Lee–Carter Mortality Model. Math. Probl. Eng. 2023, 2023, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnürch, S.; Korn, R. POINT AND INTERVAL FORECASTS OF DEATH RATES USING NEURAL NETWORKS. ASTIN Bull. 2022, 52, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelleng, A.U.; Sule, Y.J.; Kajuru, J.Y.; Kabiru, A. Comparative Study of Lee Carter and Arch Model in Modelling Female Mortality in Nigeria. UMYU Sci. 2022, 1, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ling, C.; Li, D.; Peng, L. BIAS-CORRECTED INFERENCE FOR A MODIFIED LEE–CARTER MORTALITY MODEL. ASTIN Bull. 2019, 49, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, A.J.G.; Blake, D.; Dowd, K.; Coughlan, G.D.; Epstein, D.; Ong, A.; Balevich, I. A Quantitative Comparison of Stochastic Mortality Models Using Data From England and Wales and the United States. North Am. Actuar. J. 2012, 13, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyamerah, S.A.; Arthur, J.; Akuamoah, S.W.; Sithole, Y. Measurement and Impact of Longevity Risk in Portfolios of Pension Annuity: The Case in Sub Saharan Africa. FinTech 2023, 2, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccheroni, C.; Nocito, S. Backtesting the Lee–Carter and the Cairns–Blake–Dowd Stochastic Mortality Models on Italian Death Rates. Risks 2017, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimmel, W.; Pruckner, G.J. Retirement and healthcare utilization. J. Public Econ. 2020, 184, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmeskov, J. Aging, Public Budgets, and the Need for Policy Reform. Rev. Int. Econ. 2004, 12, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.; Hagger-Johnson, G.; Head, J.; Shelton, N.; Stafford, M.; Stansfeld, S.; Zaninotto, P. Working conditions as predictors of retirement intentions and exit from paid employment: a 10-year follow-up of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Eur. J. Ageing 2016, 13, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- F. W. Heiland and Z. Li, “CHANGES IN LABOR FORCE PARTICIPATION OF OLDER AMERICANS AND THEIR PENSION STRUCTURES: A POLICY PERSPECTIVE,” 2012. [Online]. Available: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2127718Electroniccopyavailableat:https://ssrn.com/abstract=2127718Electroniccopyavailableat:https://ssrn.com/abstract=2127718.

- T. Bridges and F. P. Stafford, “At the Corner of Main and Wall Street: Family Pension Responses to Liquidity Change and Perceived Returns,” Michigan Retirement Research Center Research Paper,, no. 282, 2012, [Online]. Available: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2208568Electroniccopyavailableat:https://ssrn.com/abstract=2208568Electroniccopyavailableat:https://ssrn.com/abstract=2208568. 2208.

- Alcover, C.-M.; Topa, G. Work characteristics, motivational orientations, psychological work ability and job mobility intentions of older workers. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0195973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buyens, D.; Van Dijk, H.; Dewilde, T.; De Vos, A. The aging workforce: perceptions of career ending. J. Manag. Psychol. 2009, 24, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stynen, D.; Jansen, N.W.H.; Kant, I. The impact of work-related and personal resources on older workers’ fatigue, work enjoyment and retirement intentions over time. Ergonomics 2017, 60, 1692–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeer, N.; van Rooij, M.; van Vuuren, D. Retirement Age Preferences: The Role of Social Interactions and Anchoring at the Statutory Retirement Age. De Econ. 2019, 167, 307–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radl, J.; Himmelreicher, R.K. The Influence of Marital Status and Spousal Employment on Retirement Behavior in Germany and Spain. Res. Aging 2015, 37, 361–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic and, C. and Development, “OECD Labour Force Statistics,” 2020.

- Adejumo, W.A.; Tijani, A.R.; Adesanyaonatola, S. What Are the Socio-Economic Predictors of Mortality in a Society? J. Financial Risk Manag. 2019, 08, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Aum, J.; Han, J.-H.; Jeong, J. Optimization of compute unified device architecture for real-time ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography. Opt. Commun. 2015, 334, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Jang, D.; Kim, T. Improved Web Content Adaptation for Visual Aspect of Mobile Services. 2007 Third International IEEE Conference on Signal-Image Technologies and Internet-Based System SITIS. pp. 402–408.

- J. A. Liggett and J. R. Salmon, “CUBIC SPLINE BOUNDARY ELEMENTS,” 1981.

- Hou, X.H.; Liu, H.H. Research on Improved Spline Interpolation Algorithm in Super-Resolution Reconstruction of Video Image. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 380-384, 3722–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, A.M.; Kaishev, V.K.; Millossovich, P. StMoMo: An R Package for Stochastic Mortality Modeling. SSRN Electronic Journal, no. 1992, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Cairns, A.J.G.; Blake, D.; Dowd, K. A Two-Factor Model for Stochastic Mortality with Parameter Uncertainty: Theory and Calibration. J. Risk Insur. 2006, 73, 687–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. The expected length of male retirement in the United States, 1850-1990. J. Popul. Econ. 2001, 14, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crafts, N. The 15-Hour Week: Keynes's Prediction Revisited. Economica 2022, 89, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annear, M.; Shimizu, Y.; Kidokoro, T. Health-Related Expectations Regarding Aging among Middle-Aged and Older Japanese: Psychometric Performance and Novel Findings from the ERA-12-J. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 13509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R. The Lee-Carter Method for Forecasting Mortality, with Various Extensions and Applications. North Am. Actuar. J. 2000, 4, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, “United Nations World Population Prospects 2022,” 2022.

- Lin, H.-C.; Tanaka, A.; Wu, P.-S. Shifting from pay-as-you-go to individual retirement accounts: A path to a sustainable pension system. J. Macroecon. 2021, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Lee, R. Coherent mortality forecasts for a group of populations: An extension of the lee-carter method. Demography 2005, 42, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudvand, R.; Alehosseini, F.; Zokaei, M. Feasibility of Singular Spectrum Analysis in the Field of Forecasting Mortality Rate. J. Data Sci. 2013, 11, 851–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Zulkifle, S. H. Zulkifle, S. Rohani, M. Nor, F. Yusof, & Nurul, and S. Samsudin, “Modelling Period Effect of Lee-Carter Mortality Model with SETAR Model,” 2022.

- Antonio, K.; Bardoutsos, A.; Ouburg, W. Bayesian Poisson log-bilinear models for mortality projections with multiple populations. Eur. Actuar. J. 2015, 5, 245–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Nocito, “Stochastic Mortality Projections: A Comparison of the Lee-Carter and the Cairns-Blake-Dowd models Using Italian Data.,” University of Studies of Turin, no. 1, pp. 1–15, 2015.

- Andersen, A.G.; Markussen, S.; Røed, K. Pension reform and the efficiency-equity trade-off: Impacts of removing an early retirement subsidy. Labour Econ. 2021, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryser, V.-A.; Heers, M. Early Child-care Arrangements and Both Parents’ Subjective Well-being. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2023, 32, 1002–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppäkumpu, J.; Sivunen, A. Communicating across the borders: managing work-life boundaries through communication in various domains. Community, Work. Fam. 2023, 26, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, M.; Plagnol, A.C.; May, V. Linking Formal Child Care Characteristics to Children’s Socioemotional Well-Being: A Comparative Perspective. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 3482–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandan, M.M.; Marques, A.P. Education, Employment and Gender Gap in Mena Region. Asian Econ. Financial Rev. 2017, 7, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Terada-Hagiwara, S. F. A. Terada-Hagiwara, S. F. Camingue-Romance, and J. E. Zveglich, “Gender Pay Gap: A Macro Perspective,” 2018. [CrossRef]

- Hess, M. Retirement Expectations in Germany—Towards Rising Social Inequality? Societies 2018, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivorozhkin, A.; Nivorozhkin, E. Job search, transition to employment and discouragement among older unemployed welfare recipients in Germany. Soc. Policy Adm. 2021, 55, 747–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, H.; Kallweit, M.; Kindermann, F. Pension reform with variable retirement age: a simulation analysis for Germany. J. Pension- Econ. Finance 2012, 11, 389–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazah, N.; Duasa, J.; Arifin, M.I. Fertility and Female Labor Force Participation in Asian Countries; Panel ARDL Approach. 2021, 22, 272–288. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Wallbaum, K. Optimizing Pension Outcomes Using Target-Driven Investment Strategies: Evidence from Three Asian Countries with the Highest Old-Age Dependency Ratio*. Asia-Pacific J. Financial Stud. 2020, 49, 652–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, K. OPTIMAL PAY-AS-YOU-GO SOCIAL SECURITY WITH ENDOGENOUS RETIREMENT. Macroecon. Dyn. 2017, 23, 870–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.-H.P.; Tsui, A.K. ECONOMIC-DEMOGRAPHIC DEPENDENCY RATIO IN A LIFE-CYCLE MODEL. Macroecon. Dyn. 2019, 24, 1635–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustman, A.L.; Steinmeier, T. How Changes in Social Security Affect Recent Retirement Trends. Res. Aging 2008, 31, 261–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muryani; Watik, A. ; Wibowo, W.; Herianingrum, S.; Widiastuti, T. Study of the Socio-Economic Analysis of Females Role in Eastern part of Indonesia. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Res. Eng. 2023, 09, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, D.M.; Goodstein, R.M. Can Social Security Explain Trends in Labor Force Participation of Older Men in the United States? J. Hum. Resour. 2010, 45, 328–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.; Pedersen, P.J. Labour force activity after 65: what explain recent trends in Denmark, Germany and Sweden? J. Labour Mark. Res. 2017, 50, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalat, G.; Franck, N. Ecological study of the association between mental illness with human development, income inequalities and unemployment across OECD countries. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivankova, V.; Gavurova, B.; Khouri, S. Understanding the relationships between health spending, treatable mortality and economic productivity in OECD countries. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10, 1036058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.; Yoon, C.; Yoon, J. Influence of illness and unhealthy behavior on health-related early retirement in Korea: Results from a longitudinal study in Korea. J. Occup. Heal. 2015, 57, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, S.A.; Glymour, M.M.; Berkman, L.F. Childhood Health and Labor Market Inequality over the Life Course. J. Heal. Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Smuk, M.; Lain, D.; Stansfeld, S.A.; Carr, E.; Head, J.; Vickerstaff, S. Impact of childhood and adulthood psychological health on labour force participation and exit in later life. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 1597–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Lorenti, C. A. Lorenti, C. Dudel, J. M. Hale, and M. Myrskylä, “Working and disability expectancies at old ages: the role of childhood circumstances and education,” Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Schofield, D.J.; Callander, E.J.; Shrestha, R.N.; Passey, M.E.; Percival, R.; Kelly, S.J. Indirect Economic Impacts of Comorbidities on People With Heart Disease. Circ. J. 2014, 78, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomoike, H.; Yokoyama, H.; Sumita, Y.; Hanai, S.; Kada, A.; Okamura, T.; Yoshikawa, J.; Doi, Y.; Hori, M.; Tei, C.; et al. Nationwide Distribution of Cardiovascular Practice in Japan – Results of Japanese Circulation Society 2010 Annual Survey –. Circ. J. 2015, 79, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boissonneault, M.; Rios, P. Changes in healthy and unhealthy working-life expectancy over the period 2002–17: a population-based study in people aged 51–65 years in 14 OECD countries. Lancet Heal. Longev. 2021, 2, e629–e638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsukura, R.; Shimizutani, S.; Mitsuyama, N.; Lee, S.-H.; Ogawa, N. Untapped work capacity among old persons and their potential contributions to the “silver dividend” in Japan. J. Econ. Ageing 2018, 12, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Male | Female | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | Finland | Japan | Germany | Canada | Finland | Japan | Germany | ||

| Lee Carter | AIC | 4004 | 2628 | 5790 | 4449 | 3485 | 2271 | 5954 | 4005 |

| BIC | 4350 | 2974 | 6136 | 4795 | 4350 | 2974 | 6136 | 4669 | |

| RMSE | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.13 | |

| MAPE | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.54 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.21 | |

| Cairns Blake Dowd | AIC | 5691 | 2918 | 27531 | 14993 | 4501 | 2758 | 10562 | 10365 |

| BIC | 5946 | 3173 | 27786 | 15248 | 4756 | 3012 | 10817 | 10620 | |

| RMSE | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.19 | |

| MAPE | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.70 | 3.59 | 1.52 | 0.51 | 1.20 | |

| Year | Canada | Finland | Germany | Japan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | 11.05 | 10.70 | 16.10 | 11.26 |

| 1996 | 12.36 | 12.11 | 13.32 | 12.60 |

| 2006 | 12.97 | 12.81 | 14.07 | 12.63 |

| 2016 | 13.54 | 13.63 | 13.10 | 12.76 |

| 2026 | 14.19 | 14.53 | 15.36 | 12.36 |

| 2036 | 14.84 | 15.18 | 16.64 | 12.35 |

| 2046 | 15.44 | 15.76 | 18.07 | 12.96 |

| 2056 | 16.07 | 16.35 | 19.73 | 14.22 |

| 2066 | 16.77 | 17.00 | 21.60 | 16.06 |

| Year | Canada | Finland | Germany | Japan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | 13.20 | 16.10 | 13.91 | 11.56 |

| 1996 | 14.23 | 17.59 | 15.44 | 13.74 |

| 2006 | 15.04 | 17.97 | 16.19 | 14.27 |

| 2016 | 16.01 | 18.34 | 18.90 | 15.34 |

| 2026 | 16.84 | 19.06 | 18.75 | 14.91 |

| 2036 | 17.71 | 19.96 | 22.27 | 15.26 |

| 2046 | 18.67 | 21.07 | 20.56 | 15.63 |

| 2056 | 19.73 | 22.31 | 19.70 | 16.02 |

| 2066 | 20.87 | 23.64 | 18.61 | 16.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).