1. Introduction

More and more organizations are having to deal with Climate Change (CC). In some regions climate change has already led to a climate crisis, a crisis that has been decades in the making. In recent years, CC has been recognized as a major global risk category, according to the World Economic Forum 2023 Risk Report (WEF, 2023). For many organizations the “climate crisis” and related risks have created new business and financial management challenges. These challenges differ, depending on the defined scenario for global warming. The international community aims to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. However, this target seems more fragile than before, as recent studies show that current warming is higher (WMO, 2022). Therefore, there are also other scenarios, one of which defines a goal of limiting warming to 2 degrees Celsius, as warming above this level will cause greater irreversible damage. The climate crisis is also linked to the loss of biodiversity. While intact ecosystems, such as forests and wetlands, help absorb CO2, the destruction of ecosystems releases CO2 and makes it difficult to achieve the goal of limiting warming (CBD COP 15, 2022), and many developing countries are generally more vulnerable and exposed to CC and its impacts (Rondhi et. al, 2019).

From a business perspective, this raises the following questions: How much does the global warming cost or benefit us, depending on the scenario? How much will our revenues, investments, cost of capital, etc. increase or decrease as a result of CC? The answers also depend on an organization´s level of exposure, preparedness, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Many developing countries with their organizations and people, may turn out to be the most affected by global warming and the transition to a carbon neutral economy.

Van-Vuuren et. al. (2014) point out that we need frameworks to facilitate the creation of integrated scenarios based on combinations of climate model projections. From these, companies can build scenarios and financial methodologies and apply them to determine the financial impact on a company’s value. Three key drivers of a company´s intrinsic value have been identified: cash flows, growth and risk (Damodaran, 2012). One challenge, then, is to assess these elements in organizations under a scenario of local warming and a transition to carbon neutrality. If we know the magnitude of theses climate change impacts, change management can prioritize actions based on the incremental financial value of these impacts.

This paper contributes, in a broader sense, to the achievement of SDG (Sustainable Development Goal) number 13 on “climate action” and target 13b on “promoting mechanisms for raising capacity for effective climate change-related planning and management…” (UNEP, 2023). In a narrower sense, to answer the question whether it is possible to define a reproducible procedure to assess the financial impact of CC on an organization in developing countries, based on financial impact scenarios. Scenarios are an interesting methodological alternative due to the lack of historical data in corporate databases. Unlike a database, which typically reflects information from the past (historical data), scenarios generally model a forward-looking view of risk exposure. In this context, this paper also highlights the methodological advances that have been made in various aspects of financial climate impact assessment. The paper is organized as follows. First, we provide background information based on a review of the literature. Then, we describe the methods used to develop the proposed financial impact measurement. Then, we present and discuss the main findings. Finally, the main conclusions are drawn from these results.

2. Background

The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) is in the process of helping investors understand how a company integrates sustainability to create value. ISSB is currently working on Sustainability Disclosure Standards (Pensions & Investments, 2022). This means that the ESG disclosure landscape, which is currently fragmented, unconnected, mostly unregulated and with conflicting concepts (Larcker et. al. 2022), is evolving towards a common, global language of sustainability financial disclosures (IFRS, 2022). However, there is currently no standard, global language or regulation on how to measure the impact of global warming on an organization`s finances.

In fact, the TCFD notes that the disclosure of business resilience under different climate-related scenarios continues to have the lowest level of disclosure among the 11 TCFD recommended disclosures, at 16% (FSB, 2022). As a result, the UN currently claims that adaptation to CC is generally too slow and puts the world at risk (ONU, 2022).

ESG guidance. The ESG concept refers to three dimensions of sustainability: the environmental, social and economic dimensions, and seeks to achieve a “balance” between them in business and financial management. For example, ESG considers the interests of an organization’s different stakeholders, as opposed to focusing solely on shareholders. As a result, companies maximize these three objectives to create business value, which is the goal of any company (Damodaran, 2012). This is different from maximizing shareholder value under social and environmental constraints and therefore requires “multi-objective management”.

However, disagreement over the definition of materiality has hindered sustainability integration by separating ESG factors from business operations and cash flows (Jeb, 2019). In fact, ESG information disclosed by companies is generally referred to as “non-financial information”, even though this information is also relevant to investors and other financial decision-making.

The explicit inclusion of the environmental dimension as in sustainability reporting or in ESG scoring (SASB, 2023), (MSCI, 2023), (Bloomberg, 2023) is relatively new. Both, public listed companies, and external entities such as Bloomberg, MSCI, S&P Global or Sustainalytics assess, for example, a company’s energy and water consumption, as well as its waste production and avoidance to determine an “E”-score. This score assigns a classification or rating to the company that represents the company’s performance in terms of environmental sustainability, including the net zero aspect. This “inside-out” (environmental) perspective of the score is intended to identify investment or divestment opportunities and risks (Madison & Schiehll, 2021). Financial materiality is ultimately what investors are interested in, and this refers specifically to information on the creation of financial value for investors. We know that financial value can be affected not only by environmentally unfriendly production, but also by external factors, like stricter legislation or changes in consumer behavior as consumers demand more environmentally friendly and sustainable products and services. However, at present, ESG measurement and scoring essentially does not assess the impact of climate change or net zero on a company and its financials (“outside-in” perspective). This affects the meaningfulness of ESG scores.

CC Risks. Most organizations manage environmental impacts in terms of risk. Risk is defined as “the effect of uncertainty on objectives” (ISO 31000, 2018). Climate-related risks are generally divided into physical and transition risks (BCBS, 2021). These risks refer to events that have a potential impact on a company´s stated objectives. The first category relates to weather events such as storms, floods, droughts, etc. The second includes regulatory and political changes, as well as technological and market changes. The latter are related to changes in consumer and investor behavior that alter purchasing and investment patterns, gradually shifting the demand toward more sustainable products and services. Consequently, these changes in the transition to a more sustainable and low-carbon economy have an impact on the achievement of a company’s objectives, including financial ones.

A Qualitative Approach - Scenarios for Assessing Risk. Risk measurement is often based on an entity´s internal historical data (“internal loss data”), which may be supplemented by external data. However, in the case of CC, companies, especially in developing countries, still do not have databases with sufficient and reliable information on the probability of occurrence of climate and transition events and their impacts, in terms of losses or benefits. Scenario analysis can therefore be used as an approach, with each scenario representing a different set of conditions. For example, different assumptions about CC and the transition to a more sustainable economy.

Scenario analysis is not new and has been used in the context of enterprise risk management and operational risk (BCBS, 2006). The 2009 ISO 31010 standard defines scenario analysis as a method or tool that can be used for both risk identification and risk analysis and assessment (ISO, 2009; ANSI/ASSE, 2011). ISO 31010 defines in its Annex B10 that scenario analysis refers to the development of descriptive models of how the future might unfold (ISO; 2009).

Airmic (2016) points out that the exact method of scenario analysis is unique to each company. Therefore, the opinion of domain experts who understand the forces of change factors and business objectives is key to conducting a scenario analysis.

With respect to CC, which typically has a longer horizon (IPCC, 2022) than most other business and financial risks, the work of Ramírez et al. (2020) highlights that regulators, supervisors and financial institutions in Latin America are beginning to evaluate the acceptability of a scenario analysis and other methodologies for assessing the risk associated with climate change. This work emphasizes that “the first generation of climate metrics is based purely on CO2 emissions data” (p. 16). Regarding the second generation of metrics the authors noted that a new set of metrics is in the process of being developed. These combine multiple data sources to overcome the limitations of traditional carbon metrics, including climate and future company scenario data (Ramírez et al, 2020, p. 17). Based on this analysis, we see a growing interest in developing more comprehensive methodologies that incorporate corporate scenarios to assess the financial risks associated with climate change. Where corporate scenarios depend on climate scenarios.

Climate Scenarios. CC scenarios are not predictions of the future, but projections of what might happen by creating plausible, coherent and internally consistent descriptions of possible climate change futures. They can also provide plausible, coherent and internally consistent descriptions of pathways to specific goals. Thus, climate change scenarios can be presented in two different ways. In terms of “what might happen?” projections and in terms of goal oriented “what should happen?” pathways, where a single scenario is essentially meaningless. Rather, scenarios are used in pairs or sets to contrast different futures and options (Senses Project, 2023). From an environmental perspective, the IPCC in its Sixth Assessment Report on climate science (IPCC, 2022), documented five main climate scenarios that, at the macro level, are the starting point for defining financial scenarios at the corporate level. All of these climate scenarios assume more pronounced differences in elevated temperatures from around 2024, when companies will be even more exposed to localized warming.

For our work and in the context of a developing country we choose one of these scenarios as an example to develop a procedure for determining the financial impact of climate change on a company:

“SSP2-4.5”: Roughly in line with the upper bound of the combined commitments under the Paris Agreement. The scenario "deviates slightly from a baseline scenario of no additional climate policy, resulting in estimated warming of about 2.7°C by the end of the 21st century”.

CC Transition Scenarios. NGFS has published a series of what-if scenarios (2022). These provide a common, up-to-date reference point for understanding how climate change (physical risk), technology and climate policy trends (transition risk) might evolve in different futures. Each scenario shows a range of higher and lower risk outcomes and includes the following: (1) “Orderly”, (2) “disorderly”, (3) “hothouse world”, and (4) “too little, too late” transition scenario. For our work and in the context of a developing country we consider a “disorderly scenario”, which has been characterized by the NGFS as follows:

Scenarios and the financial assessment of CC. The BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) in its Conceptual framework for climate risk assessment for banks and supervisors (2021) proposed the use of scenarios to model and measure financial risks that are related to climate change. CC (physical risk and transition risk) affects traditional business- and financial risks through various economic transmission channels (NGFS, 2022). The assessment process at the corporate level therefore consists of a two-step approach:

determine the probability and impact of a CC event on traditional risk categories, such as market risk, credit risk, liquidity risk or operational risk, and then

aggregating the loss distributions of each individual risk, to arrive at the enterprise risk, and to obtain a loss distribution for the firm as a whole, where this loss distribution includes losses caused by CC events.

One challenge in applying this approach is estimating the probabilities (Shefrin, 2016) or frequencies with which CC events, such as transition events like a new or updated law or a lawsuit due to an environmental claim (Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, 2023), will occur.

In this context, Boushey et al (2021) point out that new tools are needed to assess climate-related financial risks, as the transmission channels and climate impacts are not so clear at present.

Financial Climate Stress Testing. A climate risk stress test is described in ECB - European Central Bank (2022), which argues that “climate change and the transition to net-zero carbon emissions pose risks for households and businesses and thus for the financial sector. As a result, addressing environmental and climate-related risks is one of ECB’s strategic priorities. However, the Banking Supervision Report for 2022-24, criticizes the measurement process as follows:

While many banks indicated that they intend to reduce exposures to sectors and counterparties with higher GHG emissions, banks showed little sensitivity when it comes to strategizing for different scenarios. … This lack of elaboration on the different pathways’ points to the need for further efforts to formulate strategic options for long-term transition scenarios.

This suggests that organizations do not always have a clear understanding of the level of sensitivity of their different operations to climate risk. For example, different services or lines of business may have different sensitivities. Where sensitivity refers to the combination of “relevance” and “proportionality” (Asobancaria, 2022):

Relevance: the degree of exposure to climate risk of the economic activities financed by the entity.

Proportionality: related to the nature of the financial institution´s operations and the complexity of the set of products and services offered.

Quantitative Approach - Climate Beta Factor. In addition to the above approaches, we also identify a proposal to modify the calculation of the cash flow discount rate, which mathematically considers the risk or estimated variability of the cash flows. Part of this calculation is the beta factor. The beta factor, which is, for example, part of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) (see e.g.: Fama & French, 2004) that is used to determine the cost of equity for a company, indicates the riskiness of the business in which a company operates, relative to the riskiness of the market as a whole. The equation for calculating beta is the covariance of the return of an asset (stock of the company

) with the return on a benchmark (stock index

), divided by the variance of the return on the benchmark over a given period (

), (Fama & French, 2004):

When markets are close to efficient, prices, and hence beta reflects the available information and expectations of supply and demand, and thus of sellers and buyers. This includes information and expectations about CC, physical and transition risk, net zero and the financial consequences for the company’s returns. This market-based view implies that if CC increases or decreases the riskiness of a business or a company relative to the market, then beta will reflect this.

To test the resilience of financial institutions to climate-related risks, (Jung et. al., 2021) present a CRISK measure to account for systemic climate risk, which is the expected capital shortfall of a financial institution under a climate stress scenario. This is a market-based measure, as previous studies suggest that climate risks are priced in the equity market. In this context the authors measure climate beta as follows:

Where, r

it is the stock return of organization (bank) i, MKT is the market return, and CF is the climate risk factor, measured as the return on the stranded asset portfolio. Market beta and climate beta in this regression measure the sensitivity of bank i´s returns to market risk and transition-related climate risk, respectively (Jung et. al, 2021).

They also present climate beta as a measure that quantifies how sensitive a stock (asset) is to the transition to a low-carbon economy. These authors show that this metric can discern between companies that are vulnerable to transition risks and those that are likely to benefit from a transition to net-zero emissions (Huij et. al., 2022).

Another quantitative method that has gained attention in the literature and in companies is the use of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) ratings to evaluate companies. ESG ratings are a measure of a company’s sustainability performance and are often used by investors to assess the environmental and social risks associated with a particular investment. Recent research has shown that companies with higher ESG ratings tend to perform better financially, especially over the long term (Kim & Park, 2021), (Khan et al., 2016). A Deloitte study found that ESG scores are rewarded with an “ESG-driven value premium” in the form of a higher EV/EBITDA (Enterprise Value / Earnings Before Interests Taxes Depreciation and Amortization) trading multiple (Deloitte, 2022). Using regression analysis, the authors found that a 10-point increase in ESG score was associated with an approximately 1.2 times higher EV/EBITDA multiple. This suggests that ESG ratings can be a useful factor for investors and companies in creating financial value. However, an ESG score does not assess the impact of CC on a company’s financials.

Other financial measures, such as cash flow analysis and valuation methods, have also been used to estimate the financial impact of climate change on companies (Battiston et al., 2017), (Park & Noh, 2017), (CPA Canada, 2021).

Building on the existing literature, our study proposes a financial cash flow-based approach to assess the financial impact of climate change on firms that incorporates external factors. By incorporating outside-in perspectives, our procedure aims to provide a more intuitive and holistic understanding of the financial impact of climate change on firms, and to support more effective decision-making in the face of these risks. In particular, it is our view that the probability of occurrence of climate risk events, such as transition risk events, is difficult for companies to estimate.

3. Methods

Our research is exploratory and forward-looking, exploring the financial impacts of climate change, on cash flows. The construction and evaluation of financial cash flows is a well-known, widely used and researched concept in financial analysis (Delapedra-Silva, et al., 2022), (Desai, 2019), (Damodaran, 2012). It is qualitative in that it requires expert opinion and it is quantitative in that we perform basic Excel-based calculations of a company’s cash flow. It is descriptive in that narratives describe and support the numbers and cash flow changes caused by climate change.

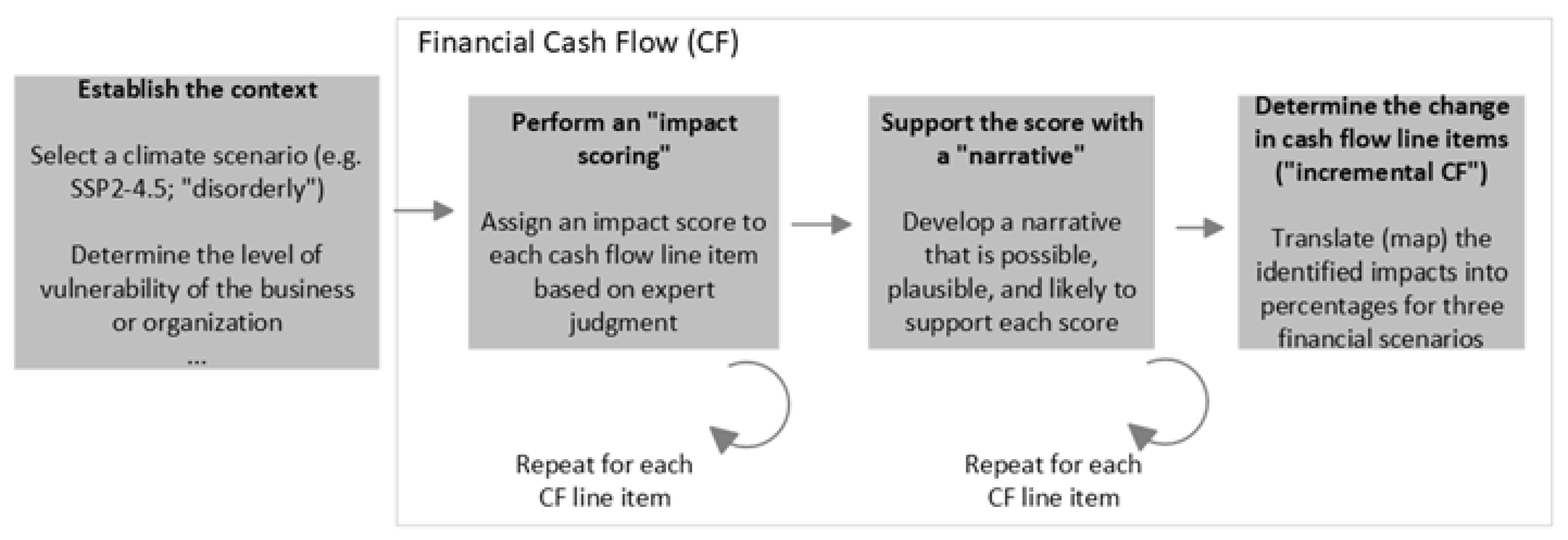

Figure 1 below outlines the proposed financial assessment steps.

Setting the stage

To estimate the financial impact of climate change and net zero respectively we focus on cash flow as our financial “bottom line” and primary unit of analysis (Desai, 2019). Climate change and net zero initiatives have led to climate scenarios that can be used to define financial scenarios based on fact-based narratives or short stories. Where the power of a story drives business value, adding substance to the numbers and enabling the decisions or assessments made by the experts (Damodaran, 2017).

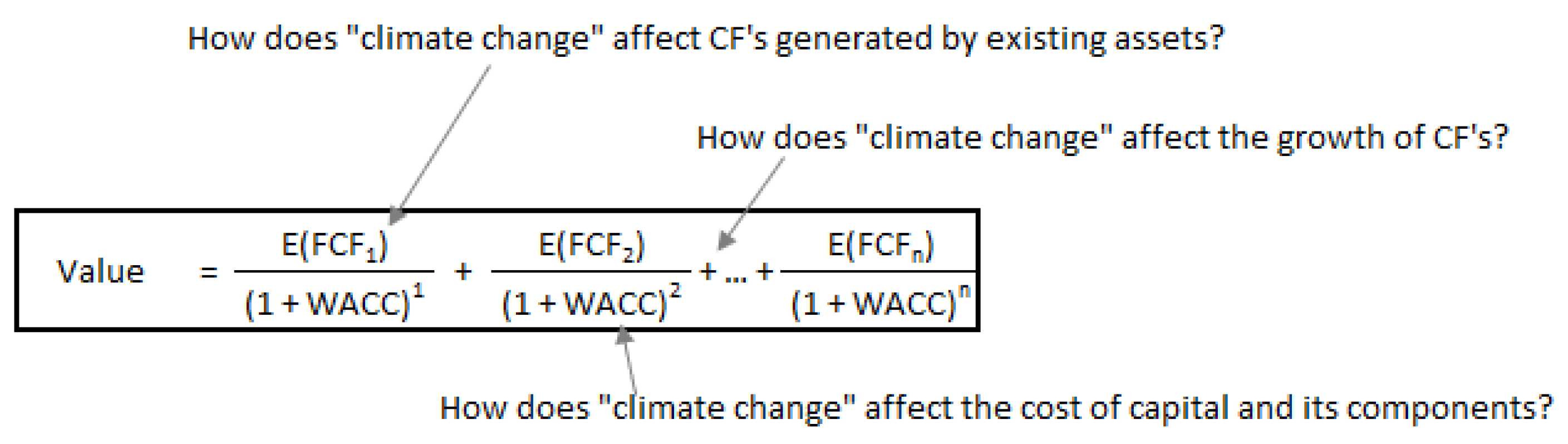

We propose three different financial scenarios to incorporate climate change. These three scenarios represent different levels of uncertainty and relate to the riskiness of the financial numbers of the cash flow and ultimately its net present value. Thus, each financial scenario is a numerical representation of a climate narrative, in terms of the affected cash flow line items and their main value drivers, as shown in

Figure 2 below: The cash flows that are generated from existing assets (investments), the growth of the cash flows based on new assets / investments, and the risk (variability) of these cash flows, which is reflected in the cost of capital that determines the hurdle rate or required financial rate of return.

Where:

CF: Cash flow

E(FCF): Estimated free cash flow

WACC: Weighted average cost of capital

1 … n: Periods, such as years.

Variables and parameters

Scenarios. As noted before, we use the “SSP2-4.5” climate scenario and a “Disordered Transition” scenario as possible and plausible, evidence-based assumptions for our work. Disordered because we believe that the transition to a more sustainable economy is still not a priority for most developing countries and because we assume that these countries generally lack the fiscal flexibility to finance the transition.

To financially account for these climate scenarios, we propose three financial scenarios: A base case (most likely), a best case (optimistic) and a worst case (pessimistic) financial scenario.

Climate variables. A climate scenario can be described in detail by the “climate variables” that we show in

Table 1 of the Supplementary Material.

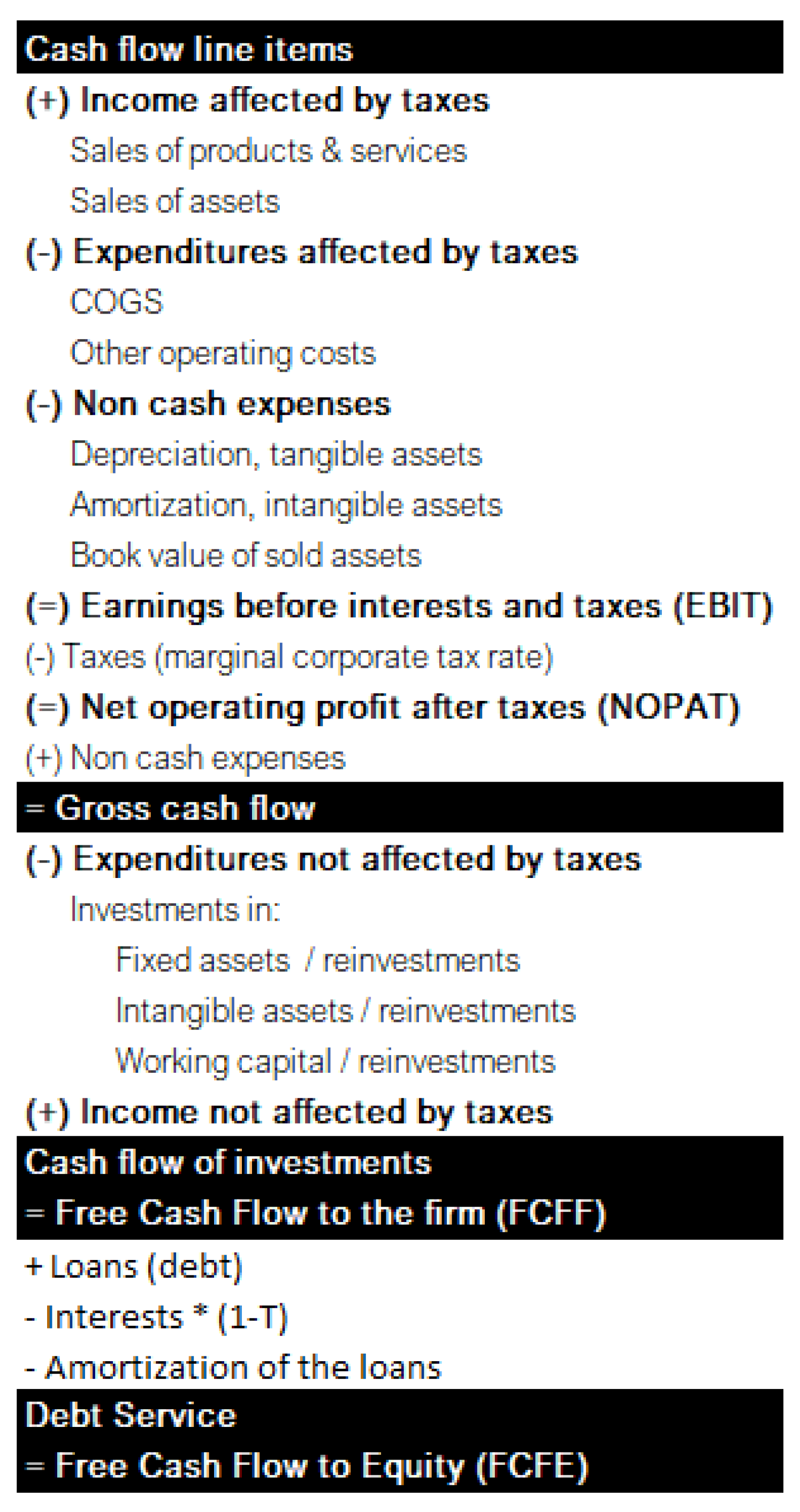

Financial variables. We consider the following free cash flow statement variables.

Table 1.

A company’s cash flow line items.

Table 1.

A company’s cash flow line items.

Thus, subtracting the debt from the free cash flow to the firm (FCFF) yields Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE).

Each line item number is supported by a narrative that considers the financial components of a line item and begins with a series of questions.

We use the cash flow variables because almost everything an organization does or does not do is reflected in its financials and its cash flows. For example, a “bad” climate change or net-zero management will be reflected in the affected financial line items. So will high inflation, low productivity, high levels of debt, failed investments, an increase in droughts, or floods, rising sea levels, and other negative factors. After all, these aspects are all built into the cash flows. The same is true for positive factors (climate change or net zero opportunities), as they simply change the sign of the cash flows.

Narratives. For a narrative we use a set of written accounts of connected business-related events that form a “line-item business micro-story” linked to the line items of a company’s free cash flow (Beattie, 2014), (Knaflic, 2015). That is, the narrative describes “why” a line item is changed by climate change or net zero. Accordingly, narratives facilitate the communication of financial numbers, expressed in monetary terms and can increase the level of understanding and, ultimately acceptance of these monetary values. However, the use of our narratives, as part of the CC financial impact measurement procedure, does not mitigate the subjectivity or imprecision of the estimated numbers.

Data and financial case. We use simulated data. However, our data is plausible, and therefore could be generated by real world events.

Based on this data we make the financial case for a medium-sized family-owned citriculture company, operating in the countryside of Latin America, in a mountainous region of Colombia. In this region the climatic conditions are tropical and provide temperatures between 20 and 35 degrees Celsius on average to grow citric fruit without the need to use greenhouses. This agricultural company grows and sells “Valencia” oranges, a sweet, refreshing, and natural food. This product is sold without much aggregated value to a local wholesaler who is the main customer of this company. This wholesaler collects the packaged fruit from the company’s premises. Thus, distribution, in the sense of transporting the fruit to retailers or markets, is the responsibility of the wholesaler. The fruit company can be considered “mature” in terms of its life cycle.

Financial assumptions: The company’s financials are “stable” and its growth is “moderate” and motivated by consumers who are increasingly seeking diets that include natural fruits, their fiber and vitamins. Debt is also “moderate” compared to similar companies in the same industry. Currently, the marginal corporate tax rate in Colombia is 35%. The company’s citrus trees are depreciated on a straight-line basis each year. These tangible assets may become stranded assets if physical and transition risks materialize and write-offs become necessary.

Validation. Finally, the proposed procedure was validated by a small group of four experts from both, the financial sector with expertise in cash flow modeling, and experts from the environmental sector, including corporate sustainability management. All experts are from Colombia, a developing country, and are familiar with the main challenges of climate change in the region. The “usefulness” of the proposed procedure was tested using a focus group approach.

Results and discussion: A procedure for determining the financial impact

An overview of the procedure. The procedure starts with a questionnaire of line-item related questions that ask about each element that is needed to calculate the company’s free cash flow. Then, narratives are added that explain why a line item will change. We then map the impact score in the form of a three-point estimate into scenarios. This considers the variability of the company’s future cash flows due to physical and transitional climate risks.

The steps of the procedure. To determine, how climate change and net-zero will hurt or help an organization financially, we suggest a procedure with the following steps:

- 0.

-

Establish the context - an interpretation of the company’s environment:

Briefly describe the “chosen” climate scenario.

Identify the level of exposure and vulnerability to climate change of the sector or business and possibly other macro-socio-economic aspects relevant to the company’s context.

Given the established context, qualitatively determine the magnitude of the impact on cash flow line items using expert judgement (i.e., financial expertise related to the analyzed business) and based on a series of questions.

Support this judgement with a possible, plausible, and probable narrative (“line-item business micro-story”).

Map the obtained qualification (score) to a percentage (number), which refers to the estimated percentage variation of the cash flow line item, using expert judgement. This mapping can be done as an estimate for the three scenarios: worst case, base case and best case.

Thus, we include the level of risk in the nominator (cash flows) of Exhibit 1, and to avoid double counting we do not adjust (increase) the denominator, i.e., the discount rate (WACC or cost of capital). This means, that we do not introduce a climate beta or add a climate risk premium to the denominator (Ameli, 2021) because our cash flow line item estimates are scenario values, where each scenario represents a different assessment of risk, in terms of a worst, base and best-case real-world situation.

The advantage of the chosen “nominator approach” is that we estimate well known cash flow line items in a bottom-up manner starting with a financial line item question that is supported by a business-specific narrative. We believe this is easier in a corporate setting than determining a climate change risk premium for the hurdle rate. Furthermore, in the context of developing countries this approach is simpler than calculating a climate beta, where a beta factor is generally determined by linear regression. This means that it is based on historical data with the aim of determining the riskiness of a company by comparing the non-diversifiable climate risk induced volatility of stock market returns caused by climate risk with the volatility of company returns. This historical data is often not available.

The idea that climate risks have a greater impact on a company's cash flow than on its weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is based on the fact that climate risks directly affect a company’s ability to generate cash, while their impact on the cost of capital is more indirect and difficult to quantify. For example, climate risks such as floods, droughts, or natural disasters can affect a company’s production and operations, which in turn can reduce its revenues and impact its cash flow. Climate risks can also increase a company's operating costs, for example by requiring additional infrastructure investments to adapt to a changing climate.

On the other hand, the impact of climate risks on the cost of capital is more indirect and difficult to quantify because investors and lenders may have different perspectives and approaches to assessing and pricing climate risks. Some investors may view climate risks as increasing the uncertainty of cash flows and the enterprise risk relative to the market, which in turn increases the cost of capital. Other investors may believe that companies that are well prepared and adapted to face climate risks have lower risk and a lower cost of capital.

One source that supports the idea that climate risks have a greater impact on a company's cash flow is: "Climate Change and Company Valuation: Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment" by Krueger (2015): This study analyzes the impact of climate risks on company valuation in a natural experiment context, where companies are exposed to different levels of climate risk due to natural climate variability.

4. Results - An example for the case study citrus fruit company

Establishing the context: An interpretation of the company’s environment

The selected Climate Scenario. We select “SSP2-4.5” and a “disordered transition” scenario to determine the financial impact for our case study company, the family-owned citrus company in Colombia. We choose a disordered transition primarily because Colombia does not have much fiscal flexibility, and transitioning to a more sustainable economy is in practice not a top priority of either the national or local governments.

Identifying the vulnerability level and exposure to climate change. According to ND-GAIN (2022), Colombia is the 98th country most vulnerable to climate change and Asobancaria Colombia (2022) states that the agricultural sector, which includes citrus fruits cultivation, is “highly exposed” to climate change.

This interpretation of the case study company’s environment provides the context and the starting point for answering the following questions to evaluate (score) the financial cash flow line items.

If desired, additional macro-socio-economic factors can be considered to complete the external context for the financial impact assessment. For example, by using relevant climate change-adjusted socio-economic data provided by industry associations.

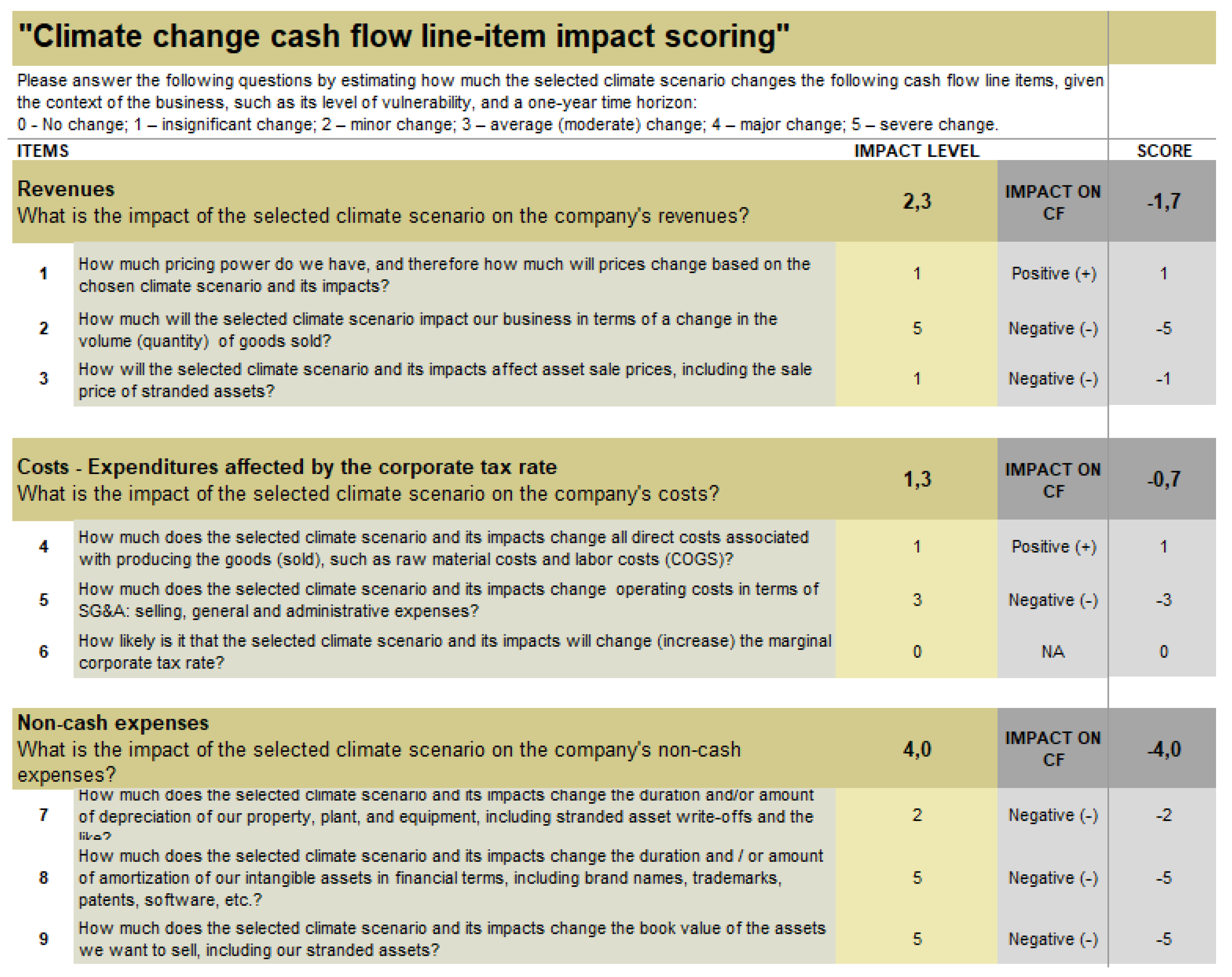

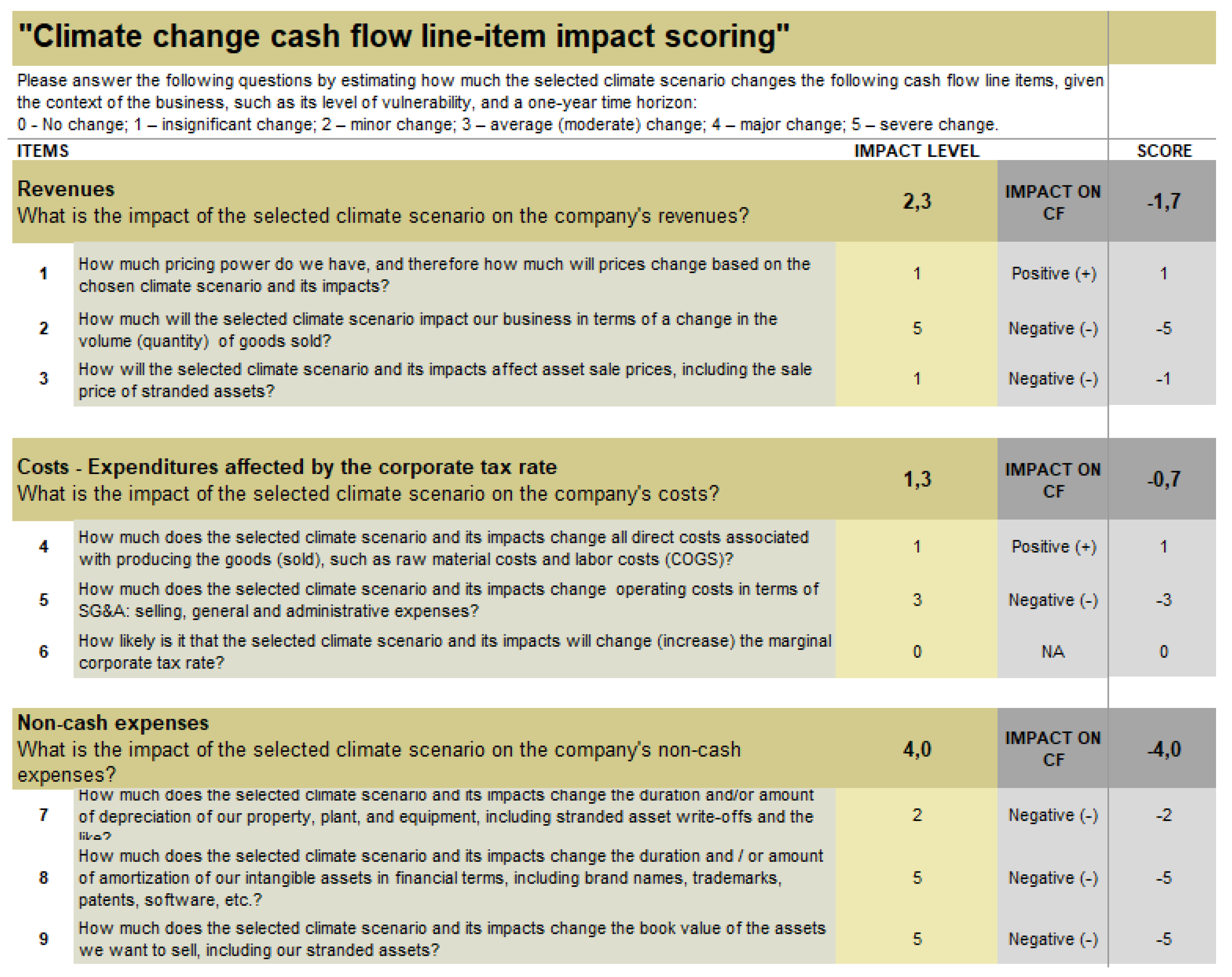

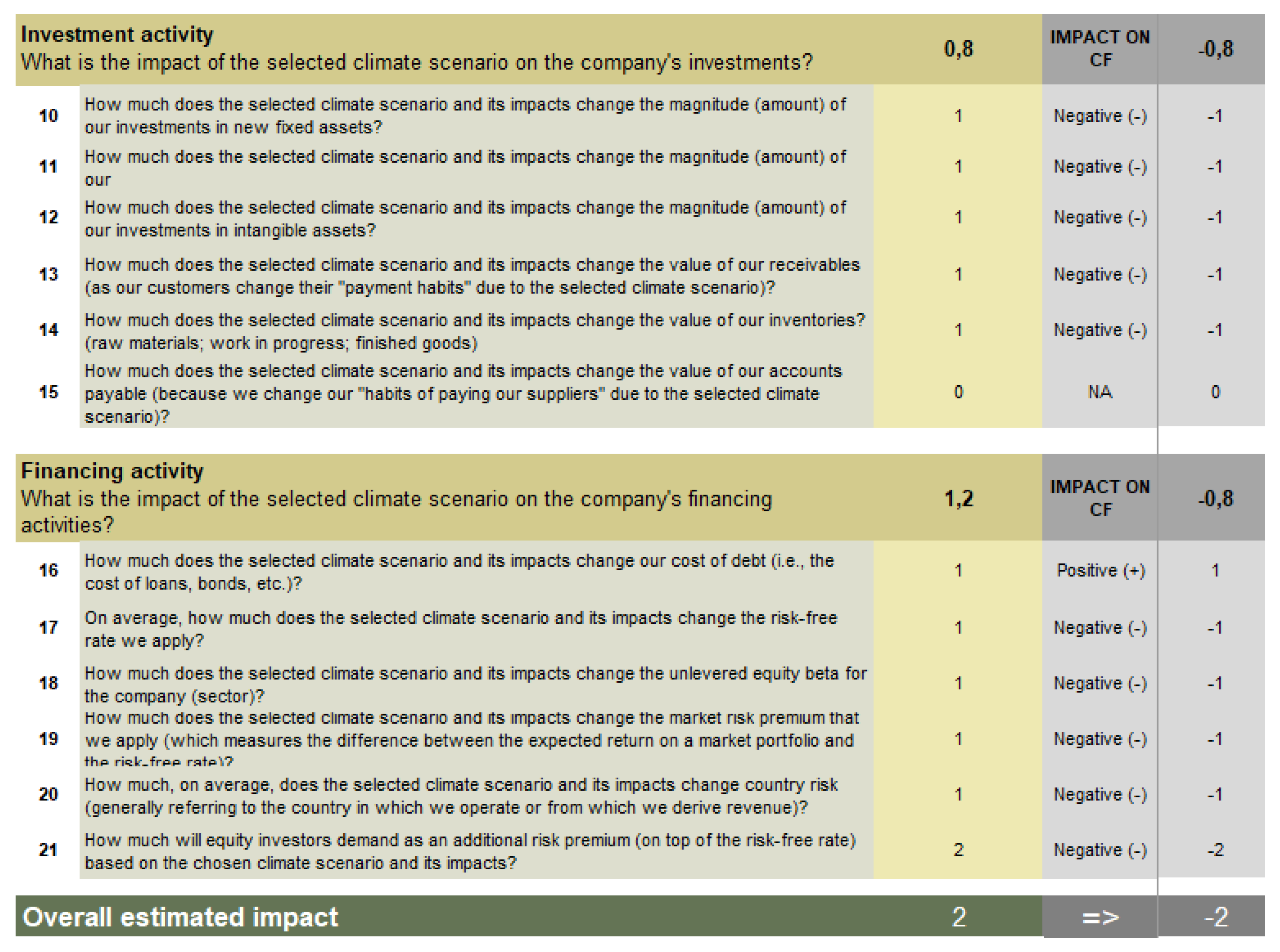

Performing qualitative line item impact scoring

Using the procedure described, we obtain the following result for our case study company, where the experts provide answers to the financial line items questions using two steps to determine the score. First, they assess the magnitude of the financial impact. Second, they determine the direction of the financial impact in terms of a positive impact (cash inflow or its increase) vs a negative impact (cash outflow or its increase) or NA, if the expert estimates neither a positive nor a negative impact (no change in cash flow). The score is determined as an average of the scores. The result of this assessment is an overall score that is negative (-1), indicating that the impact of the selected scenario, in total, is financially detrimental to the company, but “very little” (-1).

Table 2.

CC cash flow line item impact scoring.

Table 2.

CC cash flow line item impact scoring.

c

|

c

|

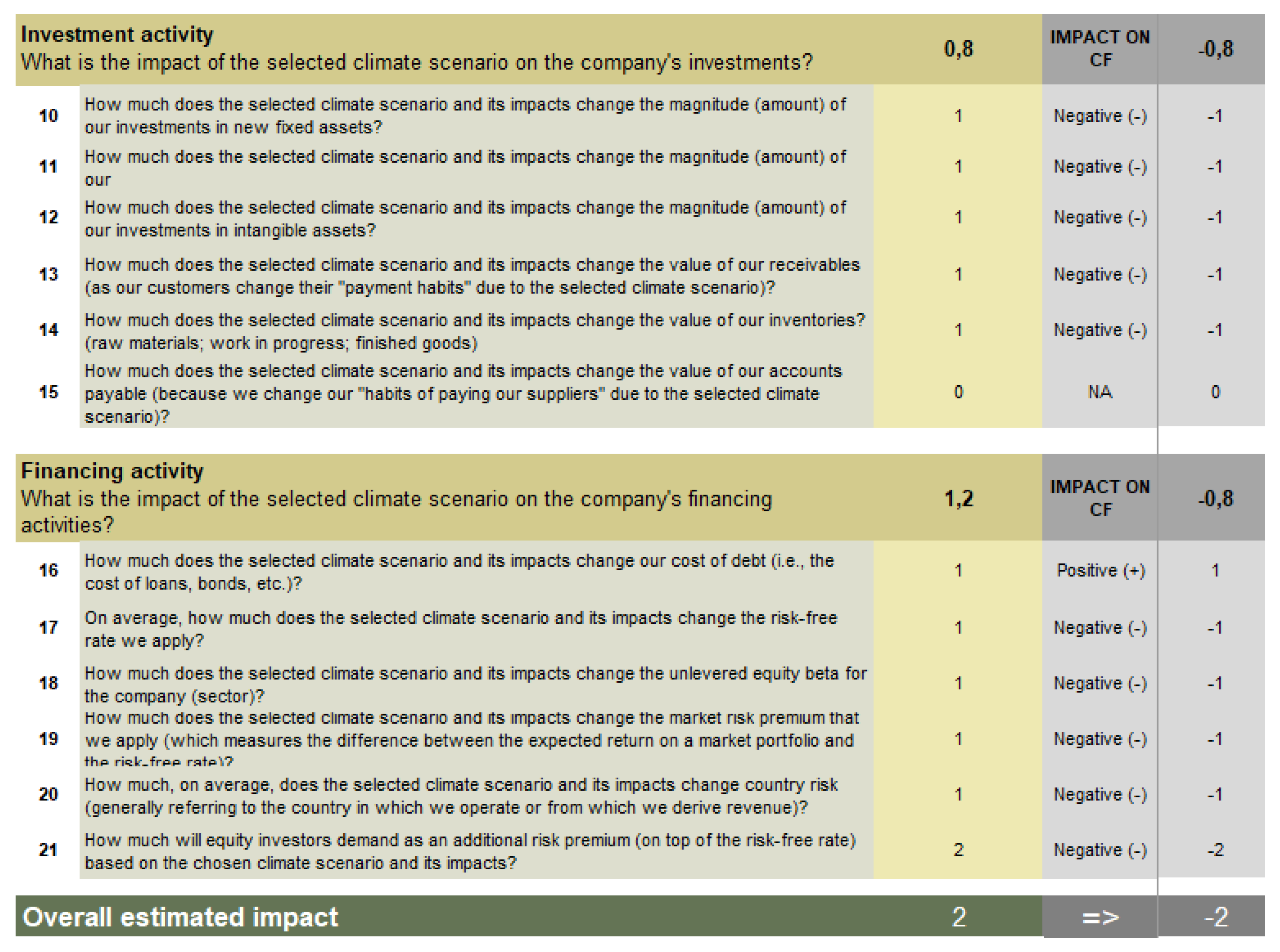

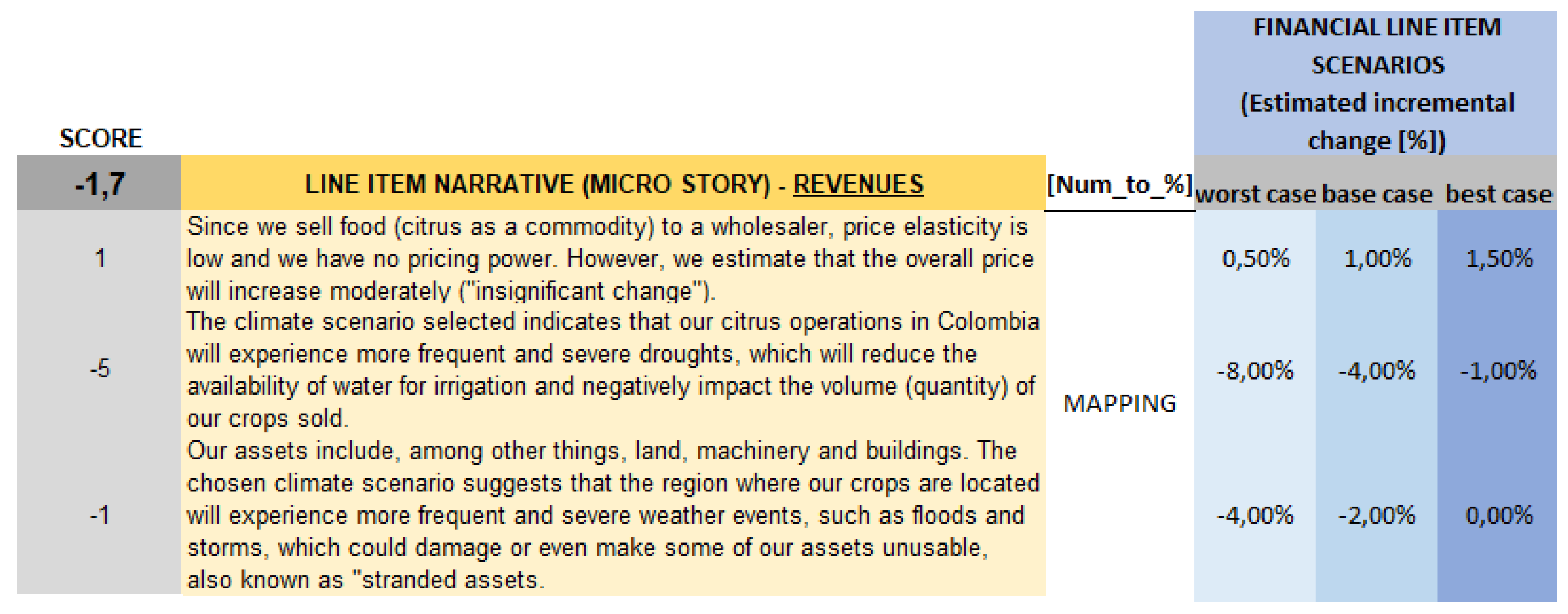

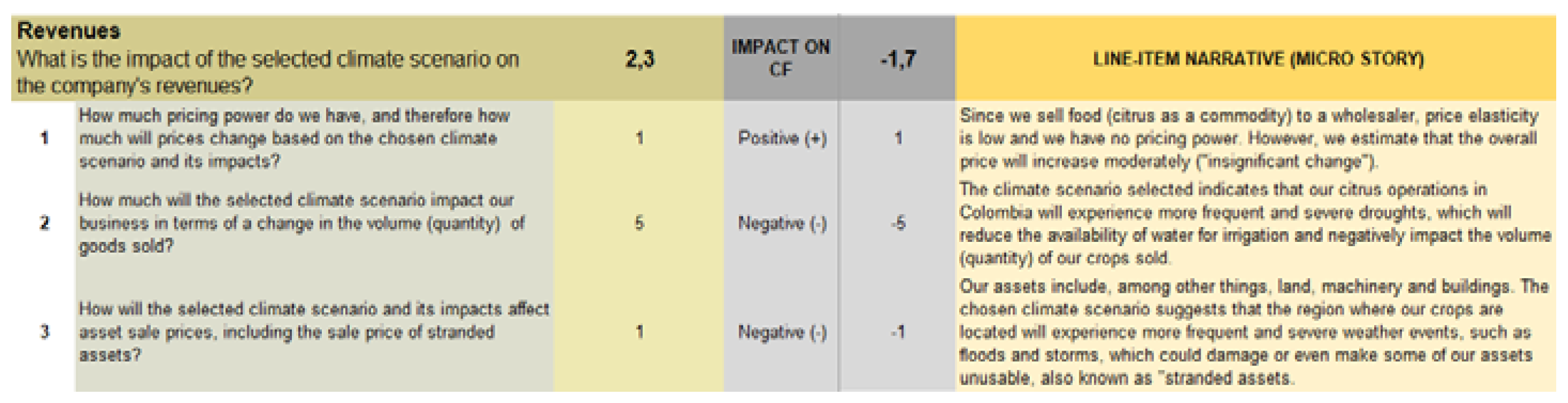

Adding a Narrative (“micro-story”)

The expert then adds a narrative that supports the score value determined for each line item. An example for the revenues of the case study company is shown in the following

Table 3. Here, the narrative is in the form of a short financial story that conveys information and leads the audience’s transition from an initial state to a later state (Robiady et al., 2021), where the later state of the cash flows includes the financial impact of CC on a line-item.

Table 3.

Revenue line-item score with narrative.

Table 3.

Revenue line-item score with narrative.

c

|

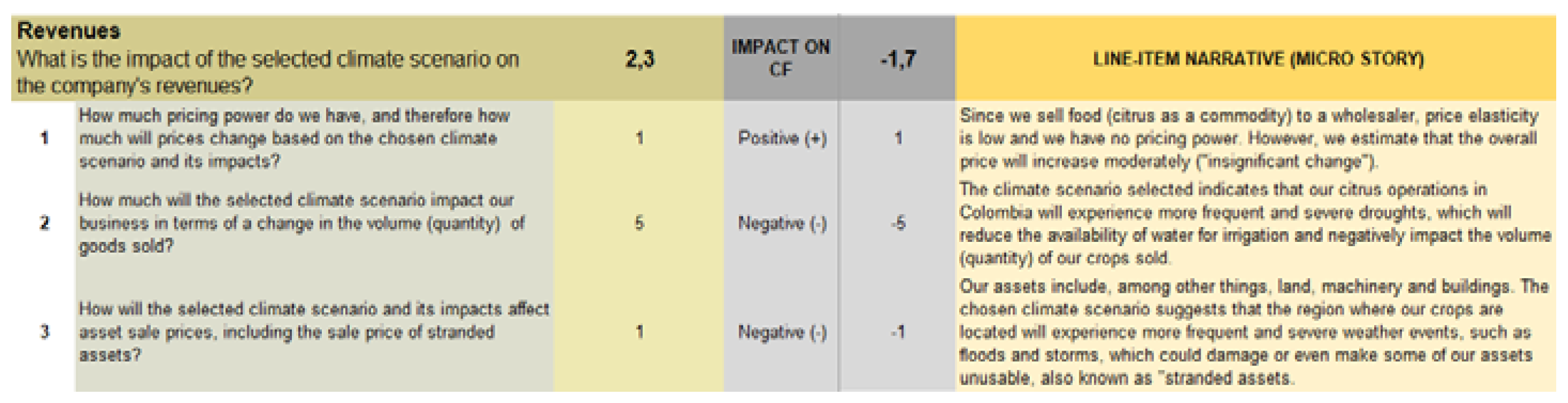

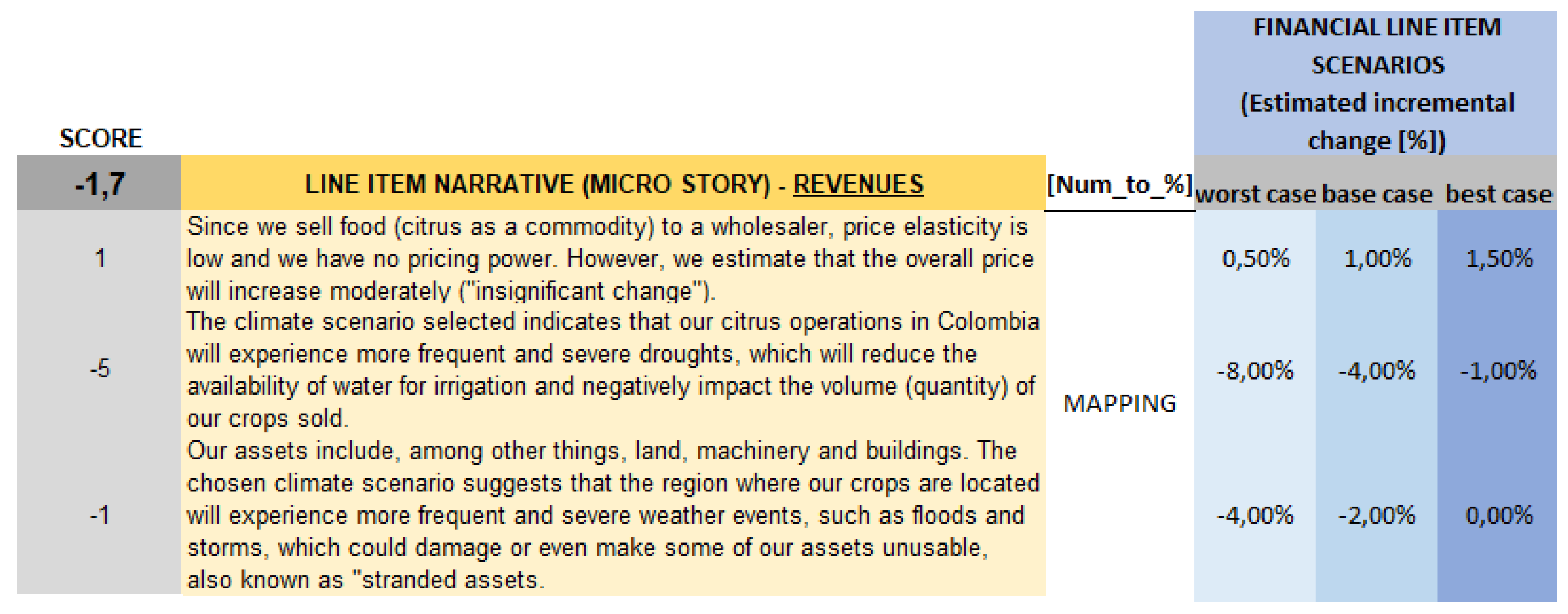

Mapping the impacts identified to percentages (category to number estimate)

The next step requires that the expert or group of experts translate or map the score, which is a categorical value, to a percentage for each scenario. The percentage indicates how much the monetary value of each financial line item moves in relative terms. Through this mapping we consider three levels of uncertainty or risk associated with the impact of climate change and therefore the scores determined. An example for the revenues of the case study company is shown in the following table 4, where each of the three financial line-item scenarios represents a level of uncertainty or riskiness regarding the specific financial impact for the line-items related to the revenues that a company receives from the sale of its produced goods (citrus fruits). For the expert, the context and starting value for determining the percentage variation of a cash flow line item is represented by the actual monetary value of the line item in an organization. Thus, the scenarios provide valuable information about the possible, plausible and probable adjustment of cash flows due to the effects of climate change, according to the chosen climate scenario.

Table 4.

Revenue line item score with narratives translated into a percentage change for three financial scenarios.

Table 4.

Revenue line item score with narratives translated into a percentage change for three financial scenarios.

c

|

Validation. The presentation and discussion of the proposed procedure for assessing the impact of CC on an organization’s finances with experts showed that the procedure is useful, in terms of “expert opinion”. Mainly because the spreadsheet-based, step-by-step style is “easy” to understand and easy to implement. The scenarios allow the simulation of different outcomes. However, an important finding was that virtually all participants in the validation session indicated that they had never before assessed CC impacts in an integral manner, as required by the financial framework provided by a cash flow statement. Another comment from participants was that the procedure remains “abstract” in the sense that we have not applied the estimated percentages to monetary values, which is ultimately the essence of a cash flow. The recommendation is to address this limitation in future research by applying the proposed procedure to a real company cash flow. Thus, it remains to be seen whether the proposed procedure is more "useful" to companies than, for example, a traditional risk measurement procedure that involves estimating the probabilities of CC risk events occurring.

Conclusions and future research

This research has developed a procedure for assessing the financial impact of climate change.

As companies, in general, still do not have a database with physical and transition risk events, their frequency of occurrence and their financial impact, it is still too early to quantify the financial impact of climate change based on mathematical, statistical or machine learning models. To address this issue, we used a qualitative financial assessment approach based on financial scenarios that incorporate expert judgement and estimates.

We conclude that this approach can help companies assess the financial impact of climate change in a structured and methodical way. The proposed procedure can be implemented in a spreadsheet, which is a well-known and widely used tool in companies, which helps in adapting the procedure to the established financial planning processes of companies.

An additional point regarding the flexibility of the proposed procedure is that it can be adapted to suit the specific needs and characteristics of different companies and industries. The use of a spreadsheet as the tool for implementing the procedure allows for easy customization and modification, making it a practical and accessible option for companies with varying levels of financial expertise and resources. However, while the flexibility of the procedure is a strength, it is important to note that careful thought and expertise are still required to ensure that the assessment accurately captures the potential financial impact of climate change on a particular company or industry.

We have found that the inclusion of narratives is promising because they add valuable expertise and generate insight by forcing the user to think through the implications and develop an argument. In addition, they can increase the acceptance of the proposed procedure by backing up the numbers and making them more accessible to the people involved in the financial impact assessment.

We conclude that the financial assessment is not a precise evaluation as the transmission of climate change into a cash flow can be many-layered and not always fully traceable. However, by incorporating narratives and expert knowledge into the assessment process, we can improve the quality and accuracy of the assessment. Narratives provide a more holistic understanding of the potential financial impacts of climate change and can help to identify previously unrecognized risks and opportunities.

Additionally, narratives can help to communicate the results of the assessment to a wider audience, including stakeholders who may not have a financial background, and can increase transparency and accountability in the decision-making process.

Finally, we recommend that companies build internal databases, so that the proposed qualitative measurement procedure can be enriched by a more quantitative approach that identifies patterns of financial impact by analyzing an organization's internal database of CC risk events.

As a result, we identify several areas for future research that can help to improve the assessment of the financial impact of climate change. These include (1) the application of the proposed procedure in a real company; (2) the creation of standardized databases, the development of robust quantitative models that implement machine learning techniques, and the evaluation of the effectiveness of climate change adaptation and mitigation activities. By addressing these research opportunities, we can improve our understanding of the planned and unplanned financial variability of cash flows associated with climate change and develop new managing strategies.

References

- Achilleas Boukis, 2023. Storytelling in initial coin offerings: Attracting investment or gaining referrals? Journal of Business Research). [CrossRef]

- Airmic. (2016). Scenario Analysis. A practical system for Airmac members. Guide 2016.

- Ameli, N.; Dessens, O.; Winning, M.; Cronin, J.; Chenet, H.; Drummond, P.; Calzadilla, A.; Anandarajah, G.; Grubb, M. Higher cost of finance exacerbates a climate investment trap in developing economies. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI/ASSE. (2011). Z 690.3 - Risk Assessment Techniques.

- Asobancaria (2022). Guía de implementación TCFD. Integración de recomendaciones TCFD para entidades financieras en Colombia. https://www.asobancaria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Guia-TCFD-para-entidades-financieras-en-Colombia.pdf.

- Battiston, S. , Mandel, A., Monasterolo, I., Schütze, F., & Visentin, G. (2017). A climate stress-test of the financial system. Nature Climate Change, 7(4), 283-288. https://web.stanford.edu/group/emf-research/docs/sm/2019/wk2/battiston2017.pdf.

- BCBS (2021). BIS - Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Climate-related risk drivers and their transmission channels. https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d517.pdf.

- BCBS (April 2021). Climate-related financial risks – measurement methodologies. https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d518.pdf.

- BCBS (2006) - Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards. Section V. https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs128.htm.

- Beattie, V. Accounting narratives and the narrative turn in accounting research: Issues, theory, methodology, methods and a research framework. Br. Account. Rev. 2014, 46, 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg (2023). ESG Data. https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/product/esg-data/.

- Boushey, H; Kaufman, N. & Zhang, J. (2021). New Tools Needed to Assess Climate Related Financial Risk, White House Council of Economic Advisors, Nov. 3, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2021/11/03/new-tools-needed-to-assess-climate-related-financial-risk-2/.

- Carbon Brief Ltd (2021). In-depth Q&A: The IPCC’s sixth assessment report on climate science. https://www.carbonbrief.org/in-depth-qa-the-ipccs-sixth-assessment-report-on-climate-science/.

- CBD COP 15 - Conferencia de Biodiversidad de la ONU en Montreal (2022). Nations Adopt Four Goals, 23 Targets for 2030 In Landmark UN Biodiversity Agreement. https://prod.drupal.www.infra.cbd.int/sites/default/files/2022-12/221219-CBD-PressRelease-COP15-Final_0.pdf.

- CPA Canada (2021). Essential Guide to Valuations and Climate Change. A framework to assess the impact of climate change on business valuations. https://www.accountingforD.org/valuations.html.

- Damodaran, A. (2017). Narrative and numbers: The value of stories in business. Columbia University Press.

- Damodaran, A. (2014). Applied Corporate Finance, 4th Edition. Wiley.

- Damodaran, A. (2012). Investment Valuation: Tools and Techniques for Determining the Value of Any Asset, 3rd Edition, Wiley.

- Delapedra-Silva, V. , Ferreira, P., Cunha, J., & Kimura, H. (2022). Methods for financial assessment of renewable energy projects: A review. Processes, 10(2), 184. [CrossRef]

- Deloitte (2022). Does a company’s ESG score have a measurable impact on its market value? https://www2.deloitte.com/ch/en/pages/financial-advisory/articles/does-a-company-ESG-score-have-a-measurable-impact-on-its-market-value.html.

- Desai, M. (2019). How finance works: The HBR guide to thinking smart about the numbers. Harvard Business Press.

- DNP-BID (2014). Impactos Económicos del Cambio Climático en Colombia – Síntesis. Bogotá, Colombia.

- Dutta, K.K.; Babbel, D.F. Scenario Analysis in the Measurement of Operational Risk Capital: A Change of Measure Approach. J. Risk Insur. 2014, 81, 303–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECB (2022). 2022 climate risk stress test. https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/ecb/pub/pdf/ssm.climate_stress_test_report.20220708~2e3cc0999f.en.pdf.

- Ergashev, B. (2012). A Theoretical Framework for Incorporating Scenarios into Operational Risk Modeling. Journal of Financial Services Research, 41(3), 145-161. [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. The Capital Asset Pricing Model: Theory and Evidence. J. Econ. Perspect. 2004, 18, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSB (2022). 2022 TCFD Status Report: Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. https://www.fsb.org/2022/10/2022-tcfd-status-report-task-force-on-climate-related-financial-disclosures/.

- Global Reporting (2022). The GRI Perspective. The materiality madness: why definitions matter. Issue 3, 22/02/2022 https://www.globalreporting.org/media/r2oojx53/gri-perspective-the-materiality-madness.pdf.

- Huij, J.; Markwat, T.; Peppelenbos, L. (12/09/2022). Indices insights: Does climate beta pick up on climate risk? Robeco. https://www.robeco.com/en-int/insights/2022/09/indices-insights-does-climate-beta-pick-up-on-climate-risk. 2022.

- IFRS (2022). ISSB describes the concept of sustainability and its articulation with financial value creation, and announces plans to advance work on natural ecosystems and just transition. https://www.ifrs.org/news-and-events/news/2022/12/issb-describes-the-concept-of-sustainability/.

- IPCC (2022). IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/.

- ISO (2018). 31000. Risk management – Guidelines.

- ISO (2009). 31010: Risk management - Risk assessment techniques.

- Jebe, R. The Convergence of Financial and ESG Materiality: Taking Sustainability Mainstream. Am. Bus. Law J. 2019, 56, 645–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H., Engle, R. F., & Berner, R. (2021). Climate stress testing. FRB of New York Staff Report, (977), revised June 2022. https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr977.pdf.

- Khan, M.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality. Account. Rev. 2016, 91, 1697–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. S. , & Norton, D. P. (2005). The balanced scorecard: measures that drive performance (Vol. 70, pp. 71-79). US: Harvard Business Review.

- Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The balanced scorecard: translating strategy into action. Harvard Business Press.

- Kim, H.H.-D.; Park, K. Impact of Environmental Disaster Movies on Corporate Environmental and Financial Performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaflic, C. N. (2015). Storytelling with data: A data visualization guide for business professionals. John Wiley & Sons.

- Larcker, D. F., Pomorski, L., Tayan, B., & Watts, E. M. (2022). ESG ratings: A compass without direction. Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University Working Paper Forthcoming. https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/cgri-closer-look-97-esg-ratings_0.pdf.

- Madison, N.; Schiehll, E. The Effect of Financial Materiality on ESG Performance Assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MSCI (2023). ESG Industry Materiality Map. https://www.msci.com/our-solutions/esg-investing/esg-industry-materiality-map.

- ND-GAIN (2022). ND-GAIN Index Country Rankings. https://gain-new.crc.nd.edu/country/colombia. https://gain-new.crc.nd.edu/country/colombia.

- NGFS (September 2022). NGFS Scenarios for central banks and supervisors. https://www.ngfs.net/sites/default/files/medias/documents/ngfs_climate_scenarios_for_central_banks_and_supervisors_.pdf.pdf.

- Park, J., & Noh, J. (2017). The Impact of Climate Change Risks on Firm Value: Evidence from the Korea. Global Business & Finance Review, 22, 110-127. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/224381.

- Popov, G., Lyon, B. K., & Hollcroft, B. (2016). Risk assessment: A practical guide to assessing operational risks: John Wiley & Sons.

- Ramírez, L., Thomä, J., & Cebreros, D. (2020). Transition Risks Assessment by Latin American Financial Institutions and the Use of Scenario Analysis. Inter-American Development Bank. Https://Publications.Iadb.Org/En/Transition-Risks-Assessment-Latin-American-Financial-Institutions-And-Use-Scenario-Analysis.

- Rondhi, M.; Khasan, A.F.; Mori, Y.; Kondo, T. Assessing the Role of the Perceived Impact of Climate Change on National Adaptation Policy: The Case of Rice Farming in Indonesia. Land 2019, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabin Center for Climate Change Law (2023). Climate Change Litigation Databases. https://climatecasechart.com/.

- Sanderson, H.; Irato, D.M.; Cerezo, N.P.; Duel, H.; Faria, P.; Torres, E.F. How do climate risks affect corporations and how could they address these risks? SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SASB Standards (2023). Exploring materiality. https://sasb.org/standards/materiality-map/.

- Schiehll, E.; Kolahgar, S. (2020). Financial materiality in the informativeness of sustainability reporting. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Senses Project (2023). What are Climate Change Scenarios? https://climatescenarios.org/primer/.

- Shefrin, H. (2016). Behavioral risk management: Managing the psychology that drives decisions and influences operational risk. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pensions & Investments (2022). ISSB to connect sustainability and corporate value in 2023 standards. https://www.pionline.com/esg/issb-connect-sustainability-and-corporate-value-2023-standards.

- TCFD (2017). Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Final Report. https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2021/10/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report.pdf.

- UNEP - United Nations Environment Programme (2023). GOAL 13: Climate action. https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/sustainable-development-goals/why-do-sustainable-development-goals-matter/goal-13.

- United Nations Environment Programme (2022). Adaptation Gap Report 2022: Too Little, Too Slow – Climate adaptationfailure puts world at risk. Nairobi. https://www.unep.org/adaptation-gap-report-2022.

- United Nations. (s. f.). ¿Qué es el cambio climático? | NacionesUnidas. https://www.un.org/es/climatechange/what-is-climate-change.

- University of Notre Dame (2022). ND-GAIN Country index. https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/.

- Van Vuuren, D. P., Kriegler, E., O’Neill, B. C., Ebi, K. L., Riahi, K., Carter, T. R., ... & Winkler, H. (2014). A new scenario framework for climate change research: scenario matrix architecture. Climatic Change, 122, 373-386. [CrossRef]

- WEF (2023). Global Risk Report 2023. https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-risks-report-2023/.

- WEF (2020). Explore the Metrics. https://www.weforum.org/stakeholdercapitalism/our-metrics.

- WMO (2022). Provisional State of the Global Climate in 2022. https://public.wmo.int/en/our-mandate/climate/wmo-statement-state-of-global-climate.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).