1. Introduction

The potato (

Solanum tuberosum L.), belonging to the Solanaceae family, holds a prominent position among the world's top four food crops. Its significance in global food production is underscored by its exceptional nutritional content and prolific yield [

1,

2,

3]. With the growing emphasis on the utilization of germplasm resources, developing effective storage solutions for seed potatoes has become crucial. In potato cultivation and production, seed potatoes play a crucial role due to their direct influence on both yield and quality, serving as the linchpin of potato production [

4,

5]. During storage, seed potatoes undergo intricate physiological and biochemical changes, leading to shifts in their chemical composition. The conditions of storage have a direct bearing on their vitality and quality [

6]. Particularly, initial seed potatoes, characterized by their diminutive size, lightweight, and diminished starch and nutrients, risk significant evaporation losses if not meticulously managed post-harvest [

7]. This predisposition could result in reduced germination, stunted seedling growth, and energy reserve depletion, thereby obstructing potato production. Mini-tuber potato seeds cultivated under aeroponics face heightened challenges.

Potato aeroponics, a novel production technique, requires suspending potato roots in hermetically sealed containers. These chambers are sporadically misted with a nutrient-rich solution using specialized devices, ensuring the potatoes receive essential water and nutrients [

8,

9]. When juxtaposed with conventional seed potato farming, aeroponics offers multiple benefits: superior yields of high-quality initial seed potatoes, condensed production cycles, absence of seasonal constraints, precision in production control, and diminished dependence on tuber seedlings. Yet, potatoes produced through aeroponics tend to exhibit increased tuber moisture, enlarged cuticular pores, elevated water content, and are more susceptible to pests and diseases [

10].

Approaches to manage potato tuber dormancy and sprouting include the use of chemicals and temperature variations [

11]. Abscisic acid (ABA) plays a crucial role in dormancy, controlling the status and germination timing to suit varying environmental conditions and survival needs. ABA is fundamental in curtailing growth and development, especially in potatoes, by inhibiting sprouting, prolonging dormancy, and thwarting untimely growth. Additionally, ABA enhances the potato's resilience against unfavorable conditions [

12]. In contrast, gibberellic (GA3) has proven effective in shortening dormancy durations. It plays an essential role in seed dormancy, promoting germination, ending dormancy, and interacting with other hormones, significantly impacting seed growth and development [

13]. Carvone serves a dual purpose: modulating sprouting and protecting mini-tubers from decay [

14]. Among its actions, a singular treatment with minimal carvone doses proves most effective for mini-tuber sprout control. Field tests reveal that carvone treatments do not negatively affect mini-tubers' emergence, field traits, yield, or harvested potato quality. Carvone also can serve both as a sprout suppressant for commercial potatoes and a sprout inhibitor for seed potatoes [

15,

16]. Empirical studies highlight temperature's profound effect on potato dormancy. Lower temperatures extend dormancy, while higher ones might induce early germination [

17]. Tubers generally sprout faster when stored between 8°C and 12°C for 5 to 9 months [

18]. Given potatoes' temperature sensitivity, understanding post-harvest processes is essential for determining ideal storage conditions. For fresh market potatoes, a temperature range of 3°C to 5°C is vital, while processed potatoes should be kept at a minimum of 4°C to retain flavor and quality [

19]. Conversely, elevated temperatures, especially between 16°C and 30°C, hasten germination, making sprouted potatoes apt for planting [

20]. Therefore, strategic temperature regulation is vital for ideal potato storage and sustainable farming practices.

Dormancy intensity follows recognizable patterns, with original species showing the strongest dormancy, followed by first-generation and subsequent generations. Original species tend to have extended and unpredictable dormancy phases. The aeroponic storage technique for these potatoes is still a nascent field. This research focuses on the aeroponic growth of these potatoes, investigating post-harvest physiochemical alterations. The primary goal is to control dormancy release and initiate sprouting before planting, providing a foundation for aeroponic seed potato cultivation. This investigation seeks to enhance seed potato farming methods and bolster sustainable agriculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Treatment

The potato cultivar employed for this study was 'Atlantic Ocean', sourced from Dingxi, China. Post-harvest, these potatoes were promptly conveyed to the laboratory. Mini-tuber potatoes that displayed uniform growth conditions, consistent size, and showed no evidence of damage or infestations were meticulously chosen.

These potatoes were subjected to varied treatments: temperature fluctuations in storage (alternating between 4°C and 20°C every 7 days, followed by room temperature storage with diffused light) and chemical treatments (0.02 mL/kg carvone, 4 mg/L ABA, and 10 mg/L GA3 combined with 1% thiourea solution). The potatoes were submerged in the solution for half an hour, followed by a 5-day sealed aerosol treatment. Subsequently, ventilation was initiated. For control, potatoes were drenched in water and stored at ambient temperature (20°C). Five treatments were instituted, each replicated thrice. Various parameters were evaluated at intervals during the study (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 days): weight loss rate, tuber decay occurrences, sprout length, germination rate, relative conductivity, malondialdehyde (MDA) content, α-amylase, SOD, and CAT activities.

2.2. Weight Loss Rate

The weight reduction rate was ascertained as described by Emragi et al. [

21] with modifications. At the experiment's onset, six potatoes were randomly picked from each batch. Their weights were logged initially and at 5-day intervals. Weight loss rate was computed as:

2.3. Tuber Decay Incidences

To determine decay rate, tuber surfaces were visually examined for soft rot symptoms, as described by Nyankanga et al. [

22]. At every scheduled interval, a set of 50 tubers were inspected for decay. Decay rate was computed as:

2.4. Sprout Length and Germination Rate

Germination length and rate were determined following Mahto et al. [

23]. Sprout lengths were gauged using a measuring tape. Germination rate was calculated as:

2.5. Relative Conductivity and MDA Content

Relative conductivity was measured with minor alterations to Xu et al. [

24]. Ten tissue samples were collected from each group, meticulously extracted, rinsed, and then submerged in 20 mL of distilled water for a 30-minute duration at a controlled temperature of 25°C. The initial conductivity (

C₀) was accurately gauged. Following a cycle of heating and cooling, the final conductivity (

C₁) of the samples was recorded. The relative conductivity was subsequently calculated using the formula:

MDA content was quantified by using kits (Suzhou Michy Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd., Suzhou China) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.6. Extraction and Assay of Enzyme Activities

All steps for crude enzyme extraction were conducted at 4°C. Tubers (5 g) were homogenized with 20 mL of an extraction buffer. The blend was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 minutes, and the supernatant was reserved for enzyme assays.

The activities of α-amylase, SOD, and CAT were determined utilizing kits provided by Suzhou Michy Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were statistically examined using one-way ANOVA in SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Each experiment followed a completely randomized design and was conducted thrice. Duncan’s test (p < 0.05) determined significant variances. All results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Graphical representations were crafted using OriginPro 2019b (Origin Lab., Micro Cal, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

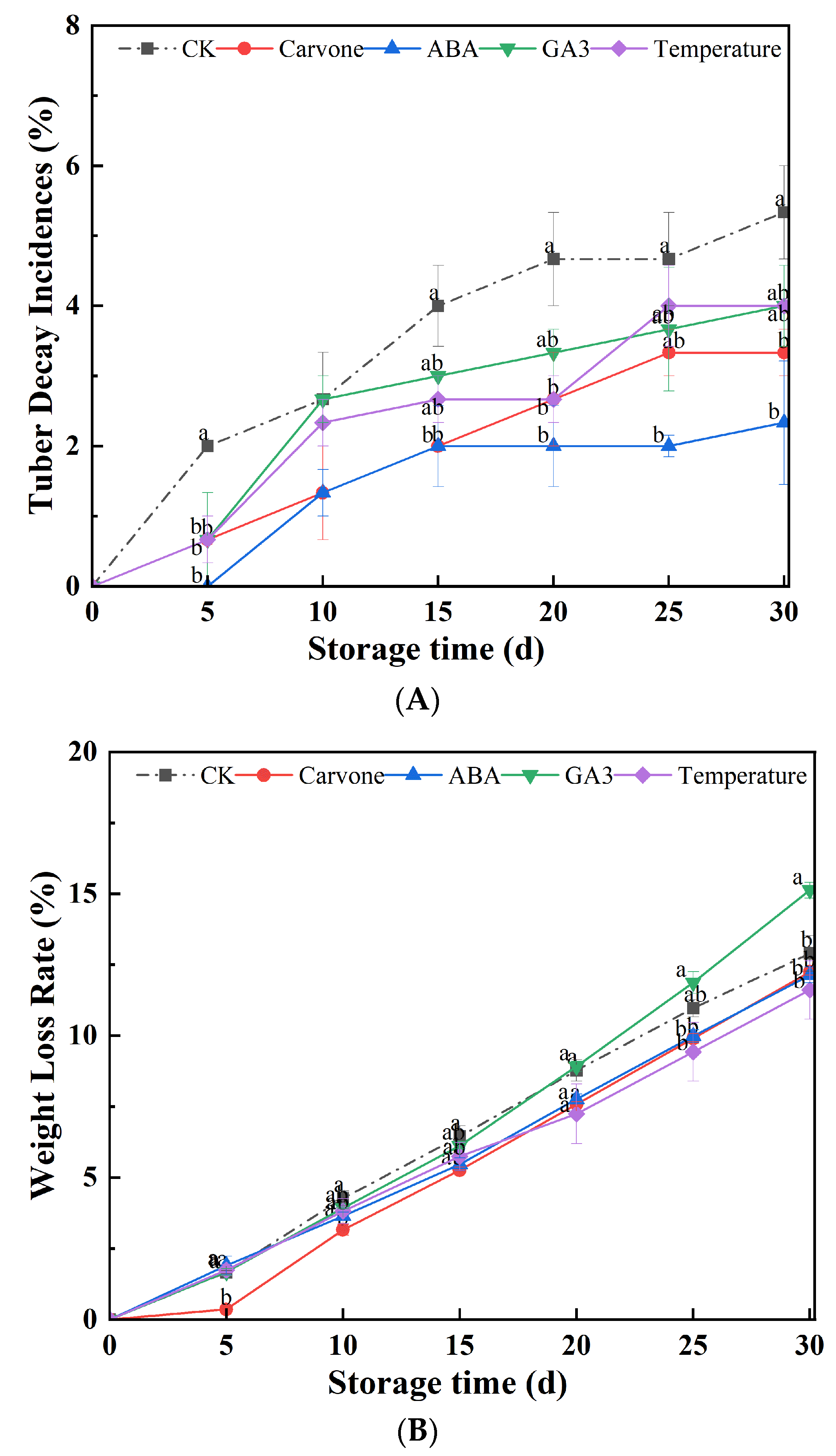

3.1. Weight Loss Rate and Tuber Decay Incidences

Figure 1A delineates an in-depth analysis of the impacts of diverse treatments on the weight loss rates of potatoes during their late dormancy phase. As the storage duration elongated, a consistent trend of tubers undergoing weight reduction was observed. Notably, 30 days into storage, the GA3 treatment manifested a weight loss rate that was 15.14% higher compared to the water treatment. Conversely, treatments employing carvone, ABA, and variable temperature modulations exhibited weight loss reductions of 12.25%, 12.13%, and 11.63%, respectively, when contrasted with the control. These data articulate the pronounced efficacy of carvone, ABA, and variable temperature treatments in curtailing weight loss throughout storage, with the carvone treatment emerging as the most impactful.

Extended potato storage invariably leads to weight diminution, a phenomenon attributed to the myriad physiological and metabolic transitions that occur during their dormant state. Within this dormancy phase, a seed's metabolic tempo diminishes, resulting in energy conservation. However, the moment this dormancy is interrupted, the seeds spring back to life, leading to moisture evaporation and subsequent weight loss [

25]. The GA3 treatment appears to stimulate this reactivation, thereby causing a more pronounced weight reduction. In contrast, treatments involving carvone, ABA, and temperature shifts seem to prolong the dormancy phase, leading to attenuated weight loss [

26]. It has been reported that carvone treatment is pivotal in sustaining dormancy, regulating bud length, and thwarting membrane lipid peroxidation in tubers. It mitigates weight loss and decay rate in seed potatoes during storage, preserves elevated SOD and CAT activity, diminishes MDA accumulation and the scope of membrane lipid peroxidation, delays physiological aging, augments ABA levels, and extends the dormant period in seed potatoes [

27]. Variable temperature treatment, by reducing the respiration rate and water evaporation, helps in minimizing the weight loss of fruits and vegetables [

28].

Figure 1B provides a detailed exploration of the varying effects of treatments on the rot rate of aeroponic tubers as they traverse the late dormancy period. As the storage timeline progressed, there was a consistent uptick in the tuber decay rate. An interesting observation was that tubers subjected to the ABA treatment exhibited 0 decay at the 5-day mark but saw a peak in rot rate by day 15. In a similar vein, both carvone and GA3 treatments reached their zenith in decay rate at the 25-day mark (3.33%) before stabilizing. The overall decay rate hit a ceiling of 4% by the 25th day and maintained this level thereafter. Importantly, all treatment modalities, which include carvone, ABA, GA3, and variable temperature, registered decay rates that were lower than the control, emphasizing their protective efficacy in tuber preservation. Of these, the ABA treatment emerged as particularly impressive, showcasing unparalleled rot-prevention capabilities.

Rising decay rates during storage are likely a consequence of microorganisms thriving under the specific storage conditions. Even as storage extends, decay persists, potentially stemming from the seeds' amplified metabolic activities once dormancy is broken [

29]. Treatments with carvone and GA3 seem poised to dampen decay rates, potentially by inhibiting microbial proliferation and simultaneously preserving the inherent physiological state of the tubers. Carvone, a compound extracted from the essential oil of coriander seeds, emerges as an environmentally-friendly antibacterial powerhouse. Notably, carvone displays formidable antibacterial prowess against pathogens commonly encountered during potato storage, notably

Fusarium sulphureum, effectively staving off afflictions like dry rot in stored potatoes [

30,

31].

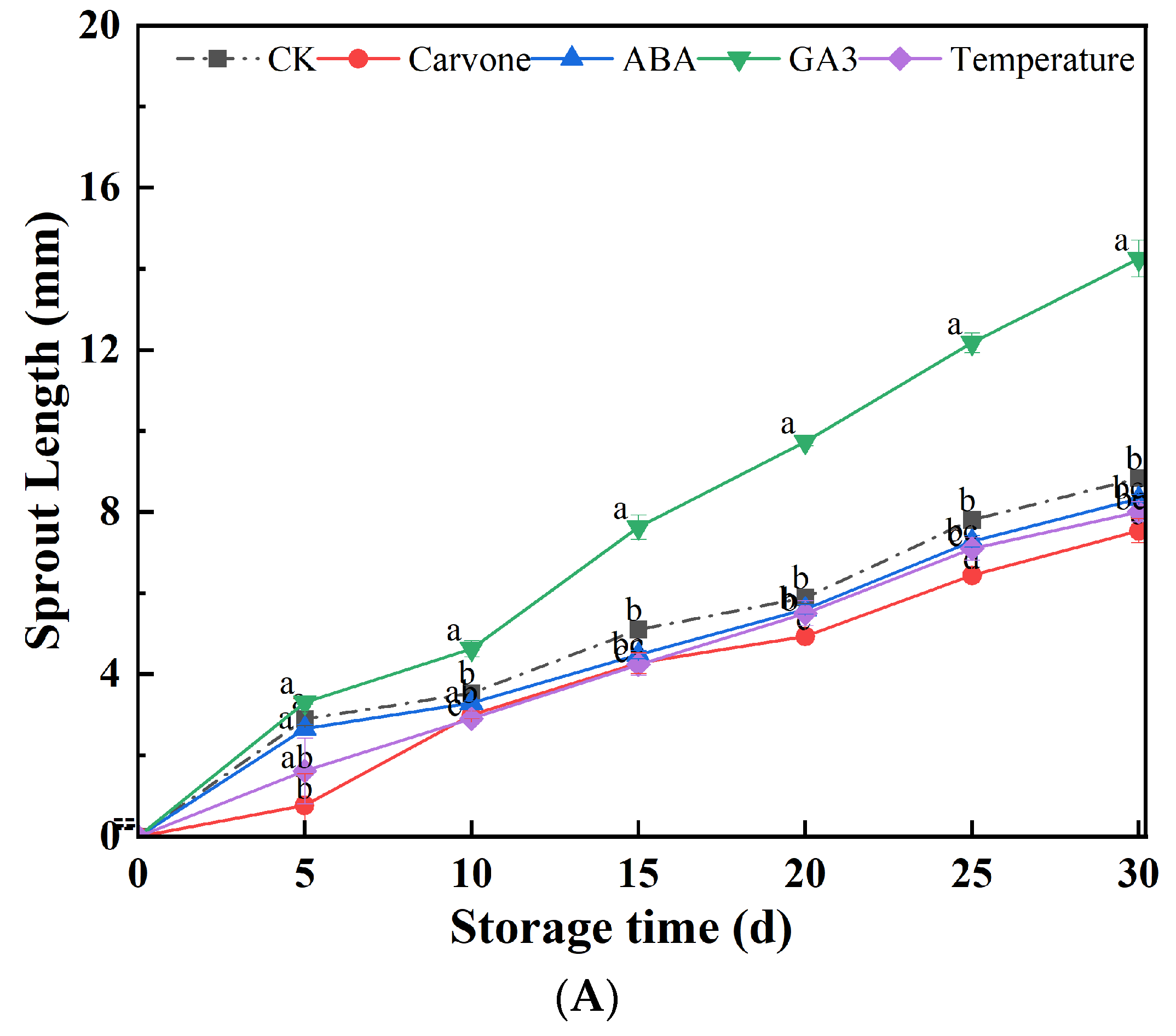

3.2. Sprout Length and Germination Rate

Figure 2 provides a detailed examination of how different treatments impact the sprout length and germination rates of aeroponic primary seeds during their late dormancy phase. As the storage timeline extended, a consistent uptrend in the sprout length of these primary seeds was observed. Intriguingly, the GA3 treatment manifested the most extended sprouts, reaching a zenith of 14.24 mm after a span of 30 days. In stark contrast, the carvone treatment culminated in the most abbreviated sprouts, measuring a mere 7.53 mm.

Following their storage phase, potato seeds segue into a profound dormancy period, characterized by a subdued metabolic tempo, which isn't conducive for bud proliferation. It's plausible that the GA3 treatment acts as a catalyst in bud growth, spurring both cell division and elongation. Conversely, the carvone treatment, with its distinct properties, might act as a deterrent to bud growth. When Carvone acts on seed potatoes, it stimulates ABA synthesis by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, hinders IAA and GA3 synthesis, thereby inhibiting seed potato germination. Removal of Carvone increases HMG-CoA reductase activity, inhibits ABA content, and increases IAA and GA3 content, resulting in the termination of seed potato dormancy [

32]. Carvone treatment significantly inhibits MDA accumulation in seed potatoes. Carvone treatment significantly increases SOD and CAT activity in seed potatoes and effectively prevents the accumulation of reactive oxygen species [

14]. Therefore, Carvone treatment helps maintain dormancy, controls bud length, and prevents membrane lipid peroxidation in seed potatoes.

Within the initial 15 days of observation, germination rates across all treatment paradigms witnessed an uptick, subsequently plateauing between the 15th and 30th day. The ABA treatment emerged as the clear frontrunner, registering a stellar germination rate of 97.33%. The other treatments, though not matching the efficacy of ABA, still posted commendable performances, with carvone and GA3 treatments clocking in at 94%, the control hovering at 93.33%, and the variable temperature treatment registering 94.67%. In this ensemble of treatments, the prowess of the ABA treatment in germination efficiency was unparalleled.

The escalating germination rates can potentially be ascribed to the seeds gradually shedding their dormancy cloak during their storage tenure, leading to the enervation of their intrinsic dormancy mechanisms. ABA has long been enshrined in botanical literature as an agent that inhibits seed germination. Positioned as a chief instigator of dormancy, multiple studies have expounded on ABA's pivotal role in perpetuating dormancy and the subsequent decline in its levels as dormancy is released [

33]. Further insights from the identification of ABA inhibitors and mutants in ABA synthesis have solidified its reputation as a dormancy-enhancing compound. Yet, it's noteworthy that this dormancy-inducing prowess of ABA can be neutralized by GA3, presenting a viable strategy to stymie germination and thereby mitigate the risk of tuber afflictions during their storage phase [

34]. ABA's inherent dynamics play a crucial role in the dormancy dance of tubers. As the tuber's formation process unfolds, there's a surge in its endogenous ABA concentrations, which in turn, puts a brake on tip growth. However, once the dormancy phase is terminated and the stem tip embarks on its growth journey, there's a precipitous drop in ABA levels. Consequently, ABA's overarching influence is most palpable in the ex vivo dormancy of potato tubers. As this dormancy phase reaches its denouement, there's a marked decrease in tuber ABA concentrations, leading to a shift in the ABA-GA ratio, which acts as the primary catalyst for tuber germination. Enhancing the reservoir of endogenous ABA through external application emerges as an optimal strategy to curtail germination rates of potatoes during their storage phase.

As this storage phase marches on, there's a gradual depletion in the seed's internal cache of ABA, which in turn, mitigates its germination-suppressing prowess, leading to a spike in germination rates. GA3, with its unique attributes, might amplify these germination rates by galvanizing cell division and growth, thereby neutralizing the inhibitory clout of ABA [

35,

36]. Insights gleaned from studying the effect of carvone on seed potato bud meristems have unveiled that in the absence of any external treatment, these seed potatoes, owing to their inherent apical dominance, prioritize the activation of their apical bud. However, a mere 2-day tryst with carvone treatment initiates a deterioration sequence in the apical meristem end and its vascular tissue, culminating in its necrosis within a 5-7 day window. This phenomenon might either spring from carvone's modulating effects on hormonal dynamics or its hydrophobic molecular structure, which influences its biological activity. The latter could inflict damage on the cell membranes of meristematic tissue, ushering in necrosis in the apical bud, while its axillary counterpart remains under the hegemony of hormonal regulation and preserves its sprouting vitality. A hiatus of three days post-treatment witnesses a waning of carvone's influence, likely attributable to shifts in the endogenous hormonal spectrum within the seed potatoes via the methyl hydroxybutyric acid conduit, which in turn, propels the growth trajectory of the axillary buds [

37]. Temperature shifts can influence the production and degradation of plant hormones, notably gibberellin and abscisic acid. These hormones are pivotal in governing seed dormancy and germination. Optimal temperatures can enhance the synthesis of GA3. Some seeds, after undergoing cold stratification (a process simulating winter conditions), produce higher amounts of GA3, facilitating their germination [

38]. On the other hand, elevated or non-ideal temperatures might amplify the production of abscisic acid, reinforcing seed dormancy [

39]. In contrast, appropriate temperature treatments, like cold stratification, can promote the breakdown or diminish the synthesis of abscisic acid, paving the way for seed germination.

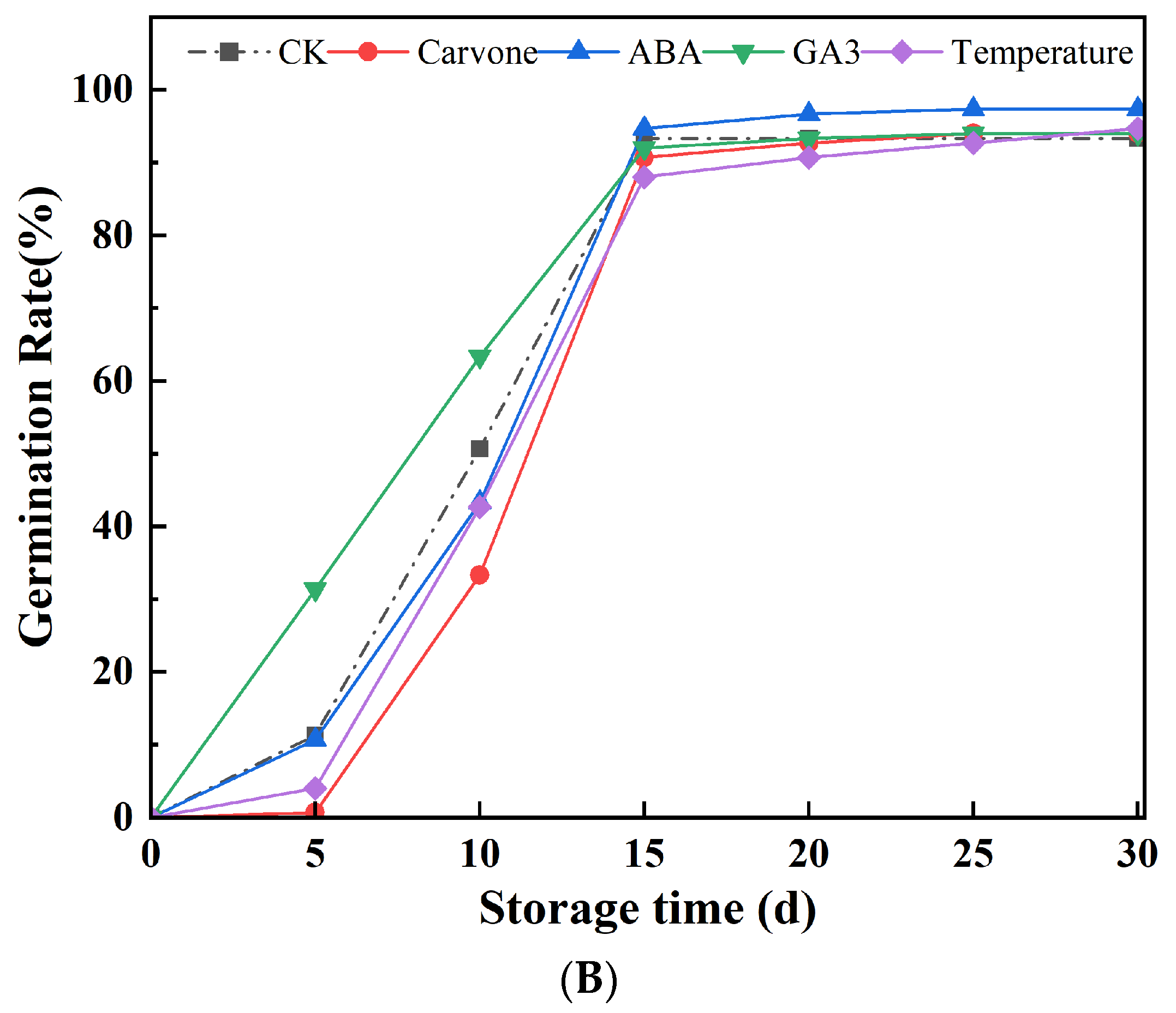

3.3. Electrical Conductivity and Malondialdehyde Content

Figure 3A offers an in-depth exploration of the varying treatments' implications on the relative electrical conductivity of aeroponic primary seeds during their late dormancy phase. Throughout the storage phase, seeds subjected to various treatments demonstrated an intriguing trend: a transient dip in electrical conductivity, followed by a steady increment. Notably, between the 10th and 25th days, the carvone treatment consistently yielded the lowest conductivity levels, demonstrating better results than other treatments. Yet, by the culmination of the 30-day observation period, all treatments showcased electrical conductivities that eclipsed the control, hinting at a degree of cell membrane deterioration in the primary seeds. Among this ensemble, the carvone treatment seemed to inflict the least cellular damage.

Electrical conductivity is a paramount metric, particularly for discerning the nutrient balance and osmotic pressure nuances in hydroponically cultivated plants. It serves as a vital indicator for gauging the integrity and permeability of cell membranes. A surge in conductivity values typically signifies heightened permeability, indicative of exacerbated cellular damage. In the context of profound dormancy, the metabolism of seeds undergoes a drastic downturn, translating into attenuated electrical conductivity. The GA3 treatment might act as a catalyst, invigorating bud growth and thereby ramping up electrical conductivity [

35]. Conversely, carvone might play the role of a suppressor, inhibiting bud growth and consequently leading to subdued conductivity.

Figure 3B meticulously chronicles the fluctuations in MDA content across the array of treatments during their storage tenure. MDA, a byproduct of lipid peroxidation, is a widely acknowledged marker for membrane lipid peroxidation and subsequent cellular trauma. Throughout the storage duration, the MDA content exhibited dynamic shifts across treatments. By the pivotal 30-day mark, the carvone and ABA treatments recorded increments of 6.73% and 0.96% from their initial values, respectively. In contrast, CK, GA3, and variable temperature treatments demonstrated decrements of 7.69%, 23.08%, and 7.69%, respectively. These observations accentuate the potency of the GA3 treatment in stymieing the escalation of MDA content in primary seeds during storage, thereby mitigating cellular harm.

The emergence of MDA as a lipid peroxidation byproduct is indicative of membrane lipid peroxidation, which in turn is synonymous with cellular damage. An uptick in MDA levels is a telltale sign of damage to cell membranes. The GA3 treatment appears to have the capability to curtail MDA content, potentially preserving the sanctity of cell membranes and staving off the lipid peroxidation reactions that can wreak havoc on them [

40]. Conversely, the carvone and ABA treatments seem to amplify MDA content, possibly due to their inability to effectively shield cell membranes from the onslaught of lipid peroxidation. Previous research has illuminated that heat treatments can effectively quell the accumulation of MDA in tubers while maintaining a relatively low electrical conductivity, thereby ensuring the stability and robustness of cell membranes. Temperature variations influence the fluidity of cell membranes, which subsequently can impact the activity of enzymes and the transport dynamics on the membrane. Seed germination is a process underpinned by the actions of numerous enzymes, including amylase and protease, which might remain dormant during seed dormancy. Fluctuating temperature treatments can awaken these enzymes, facilitating the degradation of stored materials within the seed and supplying energy for germination. Certain seeds contain dormancy-associated proteins that could hinder germination. Fluctuating temperature treatments can aid in breaking down these proteins, effectively disrupting the dormancy [

41].

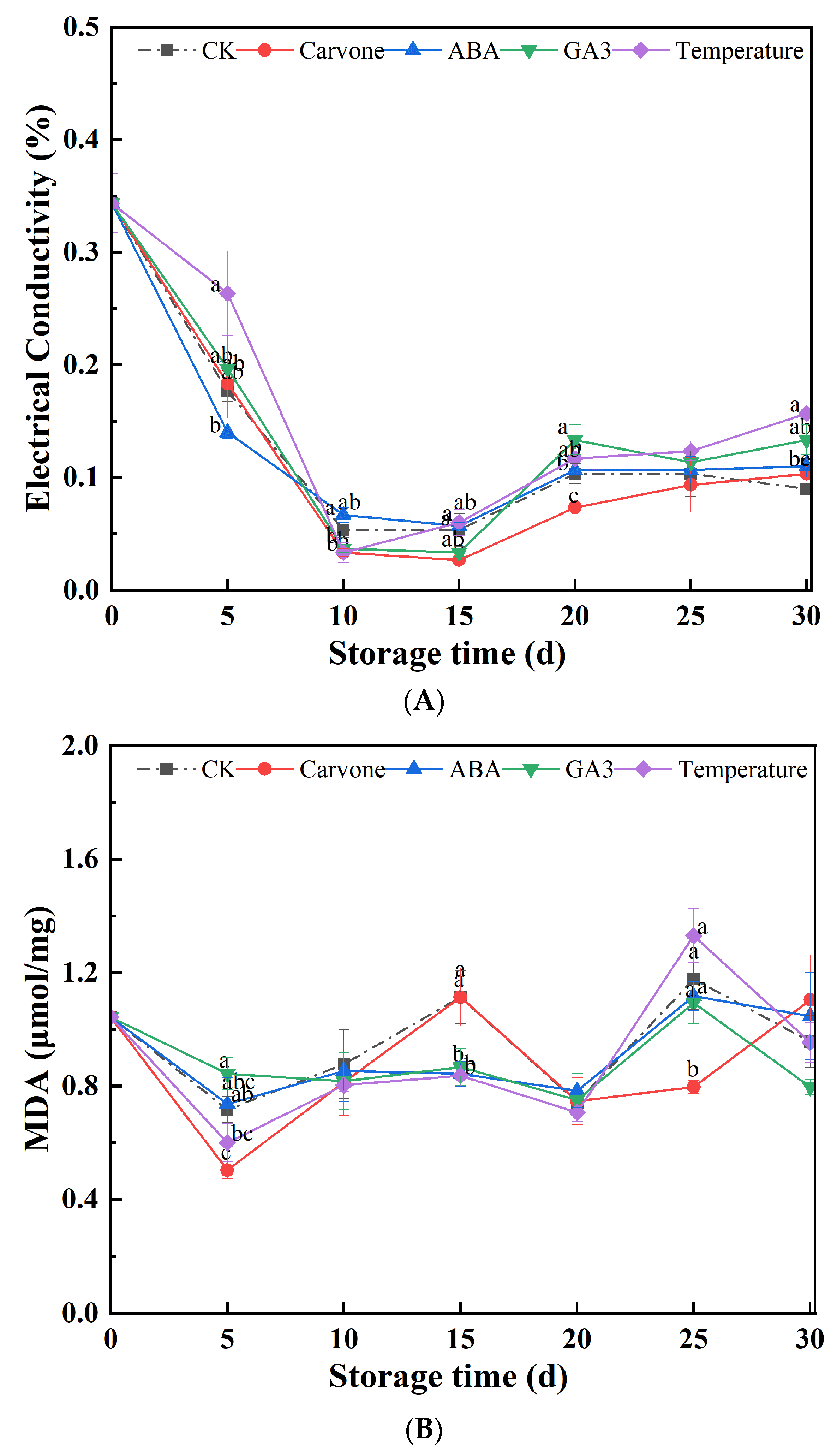

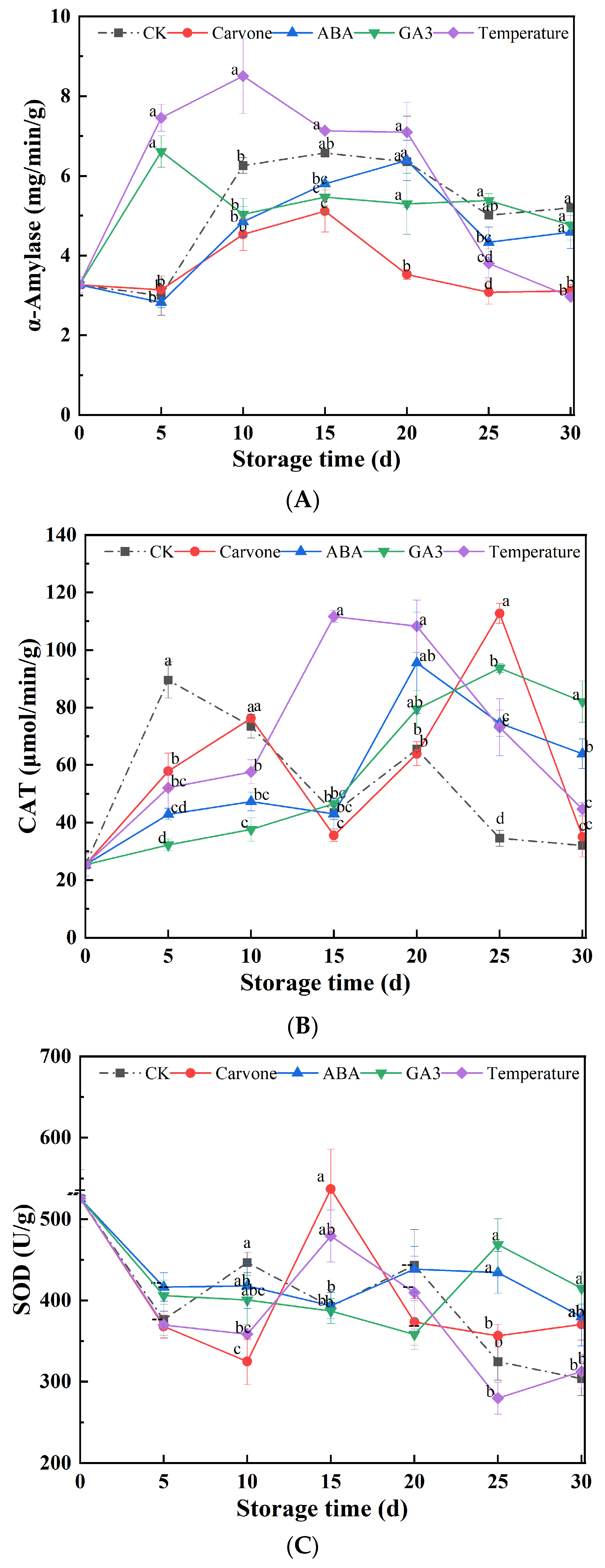

3.4.α-. Amylase, CAT, and SOD Activity

α-Amylase, playing a pivotal role in starch metabolism, emerges as a key player in seed physiology.

Figure 4A offers a panoramic view of temperature alterations and drug treatments influence α-amylase activity in original seeds during their late dormancy phase. A discernible pattern emerges across all treated original seeds throughout the storage span: an initial spike in α-amylase activity, which then tapers off. For instance, under the carvone treatment, α-amylase activity soared to a peak of 5.78 mg/min/g by the 15th day, only to retreat by 4.29% from its inception by the 30th day. The trajectory of the variable temperature treatment mirrored this trend, with a zenith of 8.51 mg/min/g by the 10th day and a subsequent 8.89% decrement from its outset by day 30. The treatments with water, ABA, and GA3 manifested peak α-amylase activities on the 20th, 20th, and 5th days, recording increments of 59.51%, 40.49%, and 46.01% from their baselines by the 30th day, respectively. In a broader perspective, the trajectory of α-amylase activity declined as the storage window expanded, underscoring the imperative of maintaining a consistent amylase activity level for the longevity of seed storage.

α-Amylase is inextricably linked to the metabolic cascade of starch. Its activity often witnesses a surge during the incipient stages of deep dormancy, likely owing to an accumulation of starch reserves within the seeds [

42]. As the dormancy phase recedes, the seeds tap into the stored starch for their energy needs. However, this reliance diminishes over time, leading to a contraction in α-amylase activity. The carvone and GA3 treatments appear to modulate α-amylase activity in distinct ways: carvone potentially acts as a suppressor, while GA3 might serve as an enhancer.

CAT, with its formidable role in disintegrating hydrogen peroxide into benign constituents like water and oxygen, is a linchpin in the cellular antioxidant defense mechanism.

Figure 4B delves deep into the ramifications of temperature oscillations and drug interventions on CAT enzyme activity in aeroponic original seeds during their late dormancy phase. An unmistakable trend emerges across all treated original seeds throughout the storage tenure: CAT enzyme activities first ascend and subsequently descend. Strikingly, both the carvone and GA3 treatments clinched the highest echelons of CAT enzyme activities, registering values of 112.73 and 93.69 μmol/min/g, respectively, by the 30th day. This translated into a marginal 0.95% increment for the carvone treatment and a staggering 223.97% surge for the GA3 treatment from their starting points. In stark contrast, the control treatment reached its pinnacle at 111.66 μmol/min/g by the 15th day, marking a robust 76.42% surge from its baseline by the 30th day. The water and ABA treatments reached their zeniths on the 5th and 20th days, with increments of 26.58% and 152.53% from their baselines by the 30th day, respectively. In a collective assessment, CAT enzyme activities under the variable temperature, ABA, and GA3 treatments outpaced those under the water treatment, while the Carvone treatment lagged slightly behind the control treatment.

CAT is quintessential for safeguarding cellular structures against oxidative stress. A rise in its activity might be a strategic response to counterbalance elevated levels of hydrogen peroxide in cellular confines post the release from dormancy. Both carvone and GA3 treatments seem to stimulate CAT activity, potentially as a countermeasure against cellular oxidative stress. In parallel, the ABA and variable temperature treatments might either minimally modulate or slightly curtail CAT activity.

Figure 4C elucidates the repercussions of temperature modulations and drug treatments on SOD enzyme activity in aeroponic original seeds during their late dormancy phase. A salient observation is that SOD activity for all treatments reached a pinnacle by the 15th day, with CK, carvone, ABA, and variable temperature treatments registering values of 478.92, 462.5, 466.53, and 453.28 U/g, respectively. By the 30th day, carvone, water, ABA, and variable temperature treatments witnessed contractions in SOD activity by 18.25%, 33.14%, 16.92%, and 32.91% from their baseline values, respectively. For the GA3 treatment, SOD activity initially ebbed until the 20th day, post which a slight resurgence was observed, culminating in an 8.36% contraction from its baseline by the 30th day. At the conclusion of the 30-day observation window, all treatments exhibited SOD activities that were superior to the control treatment.

SOD stands as a bedrock in the plant's antioxidant architecture, tasked with regulating the concentrations of superoxide anion radicals and hydrogen peroxide within cellular confines, ensuring the cellular membrane system remains impervious to damage. SOD, with its pivotal role in the plant's antioxidant framework, mitigates the adverse effects of superoxide anion radicals [

43]. An augmentation in SOD activity might be a strategic counteraction against escalating superoxide anion radicals post the cessation of the dormancy phase. The carvone, ABA, variable temperature, and GA3 treatments all appear to bolster SOD activity, highlighting their potential efficacy in combatting oxidative stress.

4. Conclusions

The intricate dynamics of post-harvest dormancy followed by the germination processes in potato cultivation are pivotal, casting profound implications on both the uniformity of the crop and its cumulative yield. The expertise in managing germination during the storage phase is of paramount importance. Not only does it mitigate potential losses, but it also ensures the sustainability and vitality of subsequent potato harvests.

This exhaustive research endeavor focused on scrutinizing aeroponic potato original seeds, all of which were sourced from a single production batch of a family-operated venture. By leveraging a judicious amalgamation of temperature modulation and a diverse array of drug interventions, our objective was to refine and optimize germination uniformity, priming the seeds for subsequent cultivation. The data amassed offers compelling evidence regarding the efficacy of the temperature variation regimen in modulating the weight attrition rate inherent to the primary potato specimens. Additionally, the ABA protocol emerged as a potent tool in curtailing rot incidences. Delving deeper, the treatments anchored around carvone, ABA, and variable temperature resulted in truncated germination lengths. Of particular note was the stellar performance of the ABA regimen, which clocked a germination rate of an impressive 97.33%, with the variable temperature regimen hot on its heels. A nuanced observation from our experiments indicated that while all treatments inflicted a certain degree of cellular membrane compromise, the carvone approach was the most benign, inflicting minimal damage. On the flip side, the GA3 protocol showcased its prowess in stymieing the escalation of MDA content during the storage phase, effectively acting as a sentinel for cell membrane preservation. Furthermore, across the board, the enzymatic activities of α-amylase, CAT, and SOD followed a consistent trajectory: an initial surge, followed by a gradual tapering, ensuring a balanced enzymatic milieu.

To encapsulate, this research, in its entirety, paves the way for a deeper understanding of the mechanisms at play and furnishes pragmatic insights into crafting robust strategies for germination management. Furthermore, it offers a blueprint for preserving the intrinsic quality of aeroponic potato original seeds during their extended dormant phase. The broader ramifications of these insights echo in the corridors of agricultural best practices, promising to revolutionize potato storage protocols and, in the grander scheme, amplify the yield and productivity of potato cultivation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Z.; methodology, T.Z; software, H.P.; validation, Z.L., and T.Z.; formal analysis, M.Z.; investigation, C.C., and S.L.; resources, Z.L.; data curation, T.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, T.Z.; writing—review and editing, T.Z.; visualization, C.C.; supervision, S.L.; project admin-istration, Z.L.; funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Plan Project of Gansu Province (GNKJ-2020-2), the Gansu Academy of Agricultural Sciences Scientific Research Conditions Construction and Achievement Transformation Project (2020GAAS10), the China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-09-P26), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31860459), and the Gansu Academy of Agricultural Sciences Scientific Research Conditions Construction and Achievement Transformation Project (2022GAAS50).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material: The data presented in this study are available in insert article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ezekiel, R.; Singh, N.; Sharma, S.; Kaur, A. Beneficial phytochemicals in potato - a review. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, H.; Ahmad, D.; Bao, J.S. Genetic diversity and health properties of polyphenols in potato. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, A.; Goffart, J.P.; Petsakos, A.; Kromann, P.; Gatto, M.; Okello, J.; Suarez, V.; Hareau, G. Global food security, contributions from sustainable potato agri-food systems. In Potato crop: Its agricultural, nutritional and social contribution to humankind; Campos, H., Ortiz, O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 3–35. ISBN 978-3-030-28683-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, D.; Jia, Y.X.; Zhang, J.Z.; Li, H.B.; Cheng, L.; Wang, P.; Bao, Z.G.; Liu, Z.H.; Feng, S.S.; Zhu, X.J.; et al. Genome evolution and diversity of wild and cultivated potatoes. Nature 2022, 609, E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.J.; Liu, H.; Zeng, F.K.; Yang, Y.C.; Xu, D.; Zhao, Y.C.; Liu, X.F.; Kaur, L.; Liu, G.; Singh, J. Potato processing industry in China: Current scenario, future trends and global impact. Potato Res. 2023, 66, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernie, A.R.; Willmitzer, L. Molecular and biochemical triggers of potato tuber development. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.J.; Lee, G.B.; Park, Y.E.; Jin, Y.I.; Choi, J.G.; Seo, J.H.; Cheon, C.G.; Chang, D.C.; Cho, J.H.; Kang, J.H. Effects of seed tuber size on dormancy and growth characteristics in potato double cropping. Hortic. Environ. Biote. 2023, 64, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunio, M.H.; Gao, J.M.; Shaikh, S.A.; Lakhiar, I.A.; Qureshi, W.A.; Solangi, K.A.; Chandio, F.A. Potato production in aeroponics: An emerging food growing system in sustainable agriculture for food security. Chil. J. Agr. Res. 2020, 80, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierno, R.; Carrasco, A.; Ritter, E.; de Galarreta, J.I.R. Differential growth response and minituber production of three potato cultivars under aeroponics and greenhouse bed culture. Am. J. Potato. Res. 2014, 91, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocic, Z.; Oljaca, J.; Pantelic, D.; Rudic, J.; Momcilovic, I. Potato aeroponics: effects of cultivar and plant origin on minituber production. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.N.; Tang, C.T.; Zhou, X.Y.; Yang, X.Z.; Luo, Z.S.; Wang, L.; Yang, M.Y.; Li, D.; Li, L. Potatoes dormancy release and sprouting commencement: A review on current and future prospects. Food Frontiers 2023, 4, 1001–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destefano-Beltrán, L.; Knauber, D.; Huckle, L.; Suttle, J. Chemically forced dormancy termination mimics natural dormancy progression in potato tuber meristems by reducing ABA content and modifying expression of genes involved in regulating ABA synthesis and metabolism. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 2879–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, M.W.; Ayyub, C.M.; Malik, A.U.; Ahmad, R. Plant growth regulators and electric current break tuber dormancy by modulating antioxidant activities of potato. Pak. J. Agr. Sci. 2019, 56, 867–877. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, X.; Xu, R.; Li, M.; Tian, J.C.; Li, S.Q.; Cheng, J.X.; Tian, S.L. Regulation mechanism of carvone on seed potato sprouting. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2020, 53, 4929–4939. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.J.; Onik, J.C.; Hu, X.J.; Duan, Y.Q.; Lin, Q. Effects of (S)-carvone and gibberellin on sugar accumulation in potatoes during low temperature storage. Molecules 2018, 23, 3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorce, C.; Lorenzi, R.; Ranalli, P. The effects of (S)-(+)-carvone treatments on seed potato tuber dormancy and sprouting. Potato Res. 1997, 40, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnewald, S.; Sonnewald, U. Regulation of potato tuber sprouting. Planta 2014, 239, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murigi, W.W.; Nyankanga, R.O.; Shibairo, S.I. Effect of storage temperature and postharvest tuber treatment with chemical and biorational inhibitors on suppression of sprouts during potato storage. J. Hort. Res. 2021, 29, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamar, M.C.; Tosetti, R.; Landahl, S.; Bermejo, A.; Terry, L.A. Assuring potato tuber quality during storage: A future perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.L.; Dusengemungu, L.; Igiraneza, C.; Rukundo, P. Molecular regulation of potato tuber dormancy and sprouting: a mini-review. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 15, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emragi, E.; Kalita, D.; Jayanty, S.S. Effect of edible coating on physical and chemical properties of potato tubers under different storage conditions. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 153, 112580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyankanga, R.O.; Murigi, W.W.; Shibairo, S.I. Effect of packaging material on shelf life and quality of ware potato tubers stored at ambient tropical temperatures. Potato Res. 2018, 61, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahto, R.; Das, M. Effect of gamma irradiation on the physico-mechanical and chemical properties of potato ( Solanum tuberosum L.), cv. 'Kufri Sindhuri', in non-refrigerated storage conditions. Postharvest Biol. Tec. 2014, 92, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.J.; Wang, D.; Zhao, W.T.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.B.; Wang, P.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, X.Y. Low frequency ultrasound treatment enhances antibrowning effect of ascorbic acid in fresh-cut potato slices. Food Chem. 2022, 380, 132190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, M.W.; Nafeesa, M.; Amina, M.; Asadb, H.U.; Ahmad, I. Physiology of tuber dormancy and its mechanism of release in potato. J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2021, 4, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, M.W.; Nafees, M.; Ahmad, I.; Ali, B.; Maryam; Iqbal, R.; Vodnar, D.C.; Marc, R.A.; Kamran, M.; Saleem, M.H.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Al-Hemaid, F.M.; Elshikh, M.S. Postharvest dormancy-related changes of endogenous hormones in relation to different dormancy-breaking methods of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 945256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Huang, Z.; Tian, J.; Xu, R.; Wu, X.; Tian, S. S-(+)-carvone/HPβCD inclusion complex: Preparation, characterization and its application as a new sprout suppressant during potato storage. Food Chem. Adv. 2022, 1, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Zhang, X. Advancements in the development of field precooling of fruits and vegetables with/without phase change materials. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 109007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, J.; Zheljazkov, V.D. Sprout suppressants in potato storage: Conventional options and promising essential oils-A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.K.; Bashyal, B.M.; Shanmugam, V.; Lal, M.K.; Kumar, R.; Sharma, S.; Vinod; Gaikwad, K.; Singh, B.; Aggarwal, R. Impact of Fusarium dry rot on physicochemical attributes of potato tubers during postharvest storage. Postharvest Biol. Tec. 2021, 181, 111638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanli, A.; Karadogan, T. Carvone containing essential oils as sprout suppressants in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers at different storage temperatures. Potato Res. 2019, 62, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterhaven, K.; Hartmans, K.J.; Huizing, H.J. Inhibition of potato (Solanum tuberosum) sprout growth by the monoterpene S-carvone: reduction of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase activity without effect on its mRNA level[J]. J. Plant Physiol. 1993, 141, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttle, J.C. Postharvest changes in endogenous ABA levels and ABA metabolism in relation to dormancy in potato-tubers. Physiol. Plantarum 1995, 95, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.T.; Zhang, N.; Fu, X.; Zhang, H.H.; Liu, S.Y.; Pu, X.; Wang, X.; Si, H.J. StTCP15 regulates potato tuber sprouting by modulating the dynamic balance between abscisic acid and gibberellic acid. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1009552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosetti, R.; Waters, A.; Chope, G.A.; Cools, K.; Alamar, M.C.; McWilliam, S.; Thompson, A.J.; Terry, L.A. New insights into the effects of ethylene on ABA catabolism, sweetening and dormancy in stored potato tubers. Postharvest Biol. Tec. 2021, 173, 111420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destefano-Beltrán, L.; Knauber, D.; Huckle, L.; Suttle, J.C. Effects of postharvest storage and dormancy status on ABA content, metabolism, and expression of genes involved in ABA biosynthesis and metabolism in potato tuber tissues. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006, 61, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumbo, N.; Magwaza, L.S.; Ngobese, N.Z. Evaluating ecologically acceptable sprout suppressants for enhancing dormancy and potato storability: A review. Plants 2021, 10, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamont, B.B.; Pausas, J.G. Seed dormancy revisited: Dormancy-release pathways and environmental interactions. Funct. Ecol. 2023, 37, 1106–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, M.; Bourdeau, N.; Barnabé, S.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Sprout suppressive molecules effective on potato (Solanum tuberosum) tubers during storage: A review. Am. J. Potato Res. 2020, 97, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Cao, Y.H.; Tang, J.; He, X.J.; Li, M.; Li, C.; Ren, X.L.; Ding, Y.D. Physiology and application of gibberellins in postharvest horticultural crops. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H. The seed and the metabolism regulation. Biology 2022, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, M.W.; Nafees, M.; Iqbal, R.; Asad, H.U.; Azeem, F.; Ali, B.; ... & Ali, M.A. Postharvest starch and sugars adjustment in potato tubers of wide-ranging dormancy genotypes subjected to various sprout forcing techniques. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14845. [CrossRef]

- Rajput, V.D.; Harish; Singh, R.K.; Verma, K.K.; Sharma, L.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R.; Meena, M.; Gour, V.S.; Minkina, T.; Sushkova, S.; Mandzhieva, S. Recent developments in enzymatic antioxidant defence mechanism in plants with special reference to abiotic stress. Biology 2021, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).