1. Introduction

Autoimmune inner ear disease (AIED), a rare autoimmune condition first identified by McCabe in 1979, is characterized by bilateral sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) triggered by an immune system response, with development over weeks to months [

1]. AIED primarily manifests as bilateral SNHL rather than just one ear in most AIED cases. Although hearing fluctuations are common, AIED predominantly involves the gradual deterioration of auditory function [

2]. In addition, 80% of AIED patients often develop additional clinical symptoms, such as dizziness, tinnitus, and aural fullness, which are difficult to distinguish from those of bilateral Meniere’s disease (MD) [

3]. Notably, even if only one ear is initially affected, AIED may eventually involve the other ear months or even years later, with its clinical progression differing from that of sudden hearing impairment or degenerative presbycusis [

1,

4,

5]. Given the overlapping clinical manifestations of AIED and MD, making an accurate diagnosis poses a considerable challenge [

6].

AIED has an incidence of fewer than five cases per 100,000 individuals per year, with female predominance; among 15% to 30% of cases with systemic autoimmune disease [

7]. The diagnostic criteria for AIED are as follows: (1) idiopathic, progressive, bilateral SNHL; (2) level of SNHL of 30 dB or higher in both ears at one or more frequencies (250, 500, 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000, 6000, or 8000 Hz); (3) active deterioration of hearing ability in at least one ear within 3 months of the first visit to a clinic; and (4) a level of hearing loss confirmed as idiopathic by a neurotologist on the basis of clinical evaluations, blood tests, and radiological imaging (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging of the internal auditory canal) [

8,

9,

10]. While AIED is rare, with it affecting less than 1% of all cases of SNHL, its prognosis is generally poor.

The pathophysiological mechanisms of this rare disease have only been hypothesized. Unlike some autoimmune diseases with a specific predominant single autoantibody, the presence of autoantibodies in AIED is uncertain. Consequently, no single autoantibody serves as a definitive diagnostic or prognostic marker for evaluating treatment responses. The challenge of identifying specific autoantibodies, along with the observed T-cell release of interleukin-17 and interferon-γ, suggests that AIED exhibits features of both autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases [

7].

The diagnostic process for AIED encompasses a thorough medical history assessment, physical examination, repeated audiograms, magnetic resonance imaging to rule out retrocochlear pathologies, and serological tests (e.g., complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, rheumatoid factor, anti-dsDNA, anti-SSA/B antibody, antiphospholipid antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, C3 and C4 complement levels, HIV, and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption). Although no uniformly accepted laboratory criteria currently exist for diagnosing AIED, the presence of bilateral SNHL of 30 dB or higher at any frequency, with evidence of progression in at least one ear on two serial audiograms obtained less than 3 months apart, is often used for case definite diagnosis [

11].

Corticosteroids serve as the primary treatment for AIED, with the widely accepted protocol proposed by Rauch et al. [

12]. In this protocol, an adult patient is first started on prednisone at 60 mg/day or 1 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks. If a positive treatment response is identified at the end of these 4 weeks, the steroid treatment is continued until clinical stabilization is achieved, after which the dosage is tapered over 8 weeks to a maintenance dose of 10 mg for at least 6 months. If the patient relapses, the dose is increased until clinical stabilization is achieved. If the patient does not respond to the initial 4-week treatment, a 12-day tapering regimen of steroid is employed [

11]. However, it's essential to note that not all AIED patients benefit from steroid treatment, with approximately 70% initially responding but this response weakening over time, resulting in an actual effective rate of only 14%. Other treatment options, including cytotoxic agents (e.g., methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and azathioprine), biologic agents (e.g., rituximab), and plasmapheresis, have been proposed but require further clinical validation. Hearing aids and cochlear implantation have also been considered as alternatives to medical treatment [

5,

6,

8,

9].

Overall, AIED presents significant challenges in both diagnosis and treatment. In this study, we investigated the detailed clinical picture of AIED and explored the risk factors impacting its progression and prognosis. Due to the rarity of AIED, its pathological mechanisms, detailed clinical presentation, treatment responses, and prognosis remain elusive. As a result, our research aims to gather extensive long-term clinical data through meticulous follow-up. This includes information such as age, gender, initial severity of hearing loss, patterns of hearing loss, accompanying symptoms, responses to steroid therapy, intervals between hearing impairment (HI) episodes in both ears, and medical history. This comprehensive analysis aims to shed light on the factors that may influence the disease's outcome.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

In this retrospective review, patients were selected from the outpatient medical records of Taipei Medical University Hospital. This study was approved by the Joint Institutional Review Board of Taipei Medical University (no, N202205043; May 24, 2022) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (JAMA, 2013). All data were obtained from the medical records documented from August 2016 to August 2021. Eligible patients aged 18–80 years who had hearing fluctuations were treated with a therapeutic dose of prednisone for less than 30 days over the initial 3 months of HI attacks. Patients with the following conditions were excluded: diabetes, history of tuberculosis or prophylactic isoniazid treatment after a positive tuberculin skin test, a severe psychiatric disease, history of a psychiatric reaction to corticosteroids, an active malignancy within the preceding 5 years, prior treatment with a chemotherapeutic agent, a positive HIV or hepatitis B or C test, and alcohol abuse.

2.2. Research Tools

All patients underwent pure tone audiometry (PTA) (average of 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz) and auditory brainstem response for testing their hearing function. In addition, patients with dizziness or disequilibrium underwent vestibular assessments, including a video head impulse test for assessing each semicircular canal and related pathway, a cervical vestibular-evoked myogenic potential test for assessing the saccules and related pathway, electrocochleography for identifying possible endolymphatic hydrops, and computerized dynamic posturography for assessing equilibrium. Hearing outcomes were evaluated using the criteria of the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, and the factors associated with prognosis were assessed. The levels of pretreatment hearing and hearing recovery outcomes were defined in accordance with the modified Siegel criteria [

15]. A positive response to treatment is defined as a PTA improvement of more than 10 dB or a word discrimination rate improvement of more than 12% [

3].

2.3. Modified Siegel criteria

The hearing recovery outcome was defined in accordance with the modified Siegel criteria and divided into the following five levels: complete recovery (CR, i.e., Final hearing level ≤ 25 dB), partial recovery (PR, i.e., Hearing gain > 15 dB; final hearing level of 26–45 dB), slight improvement (SI, i.e., Hearing gain > 15 dB; final hearing level of 46–75 dB), no improvement (NI, i.e., Hearing gain < 15 dB; final hearing level of 76–90 dB), and non-serviceable (NS, i.e., Final hearing level > 90 dB). In the present study, CR was defined as a favorable prognosis, whereas PR, SI, NI, and NS were regarded as poor prognosis.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Means and standard deviations are used to describe continuous variables with a normal distribution, whereas median (minimum–maximum) levels are used to describe variables with a non-normal distribution. Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were performed to analyze categorical variables where appropriate. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed by plotting sensitivity vs. specificity used to discriminate the power of these prognostic parameters. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Mann–Whitney U test was performed to analyze the differences between the two groups in terms of the time interval between HI occurrence in contralateral ears.

3. Results

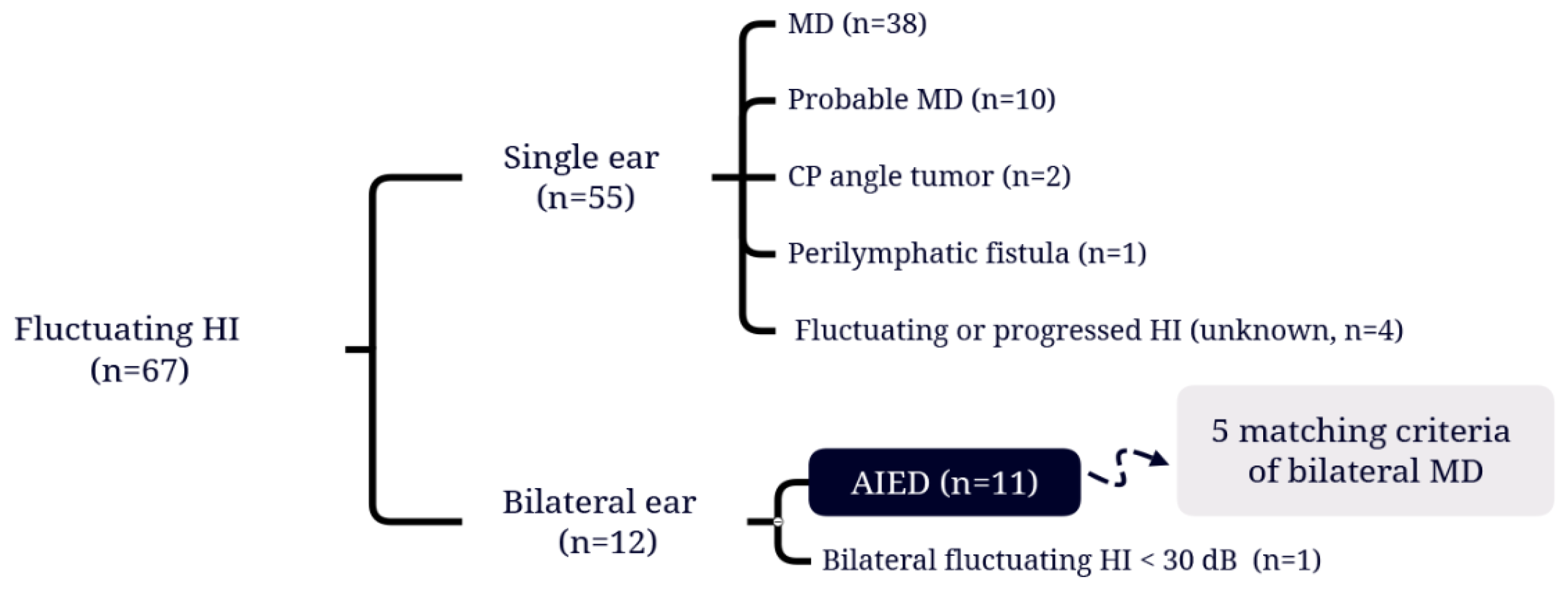

A total of 67 patients with hearing fluctuations were identified (

Table 1), and the flow chart of the study participants' selection of the study population were shown in

Figure 1. Among these patients, 38 (56.7%) had been diagnosed with MD and 10 (14.9%) met the diagnostic criteria for probable MD stipulated by the Classification Committee of the Bárány Society [

16]. 55 patients with unilateral fluctuating hearing loss attributed to a variety of medical issues were then excluded. Finally, 11 patients (16.4%) meeting the diagnostic criteria for AIED [

8] were included, among whom 5 (7.4%) also satisfied the diagnostic criteria for bilateral MD.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of each patient with AIED are summarized in

Table 2. For these patients (n = 11), all clinical manifestations of their both ears were recorded. The patients were aged 19 to 75 years, with a mean age of 40.6 years. The gender distribution consisted of four men and seven women. Initial hearing grades were stratified into four categories: ≤25 dB, 26–45 dB, 46–75 dB, and 76–90 dB, observed in seven, seven, six, and two ears, respectively. In addition, 13 ears with low frequencies loss only (250, 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz), defined as an ascending audiogram; 1 ear with high frequencies loss only (4000 and 8000 Hz), defined as a descending audiogram; and both low- and high-frequency loss was documented in 8 ears, denoted as a flat audiogram. In terms of clinical manifestations, 9 patients had tinnitus, 9 patients had aural fullness, and 6 patients had dizziness. Notably, 5 patients fulfilled the criteria for both AIED and bilateral MD, highlighting the shared clinical features between these conditions.

The mean follow-up duration for each patient was 30.6 ± 31.4 months (2–101 months) within the review period. The average time between attacks in contralateral ears was 278 ± 377.1 days (0–1141 days). All patients received 60 mg/day or 1 mg/kg/day prednisone as a therapeutic trial for 4 weeks or less depending on their individual responses. Subsequently, the dosage was gradually tapered. A total of four ears received additional intratympanic steroid injections because of poor response to the oral steroid. One male patient (Pt 5) with frequent attacks refused the oral steroid medication for his right ear hearing loss and was instead placed under observation. In total, sixteen ears exhibited a positive response to the steroid treatment, with an average duration of therapeutic response lasting 8.9 ± 10.3 days (2–48 days). However, 2 patients did not respond to the steroid treatment, and experience deteriorated hearing loss in four ears (Pt 2 and 6) despite the steroid treatment. The outcomes of hearing recovery were as follows: CR (12 ears), PR (2 ears), SI (2 ears), NI (4 ears), and NS (2 ears). 2 patients had immune-related disease: one had palindromic rheumatism and the other had systemic lupus erythematosus.

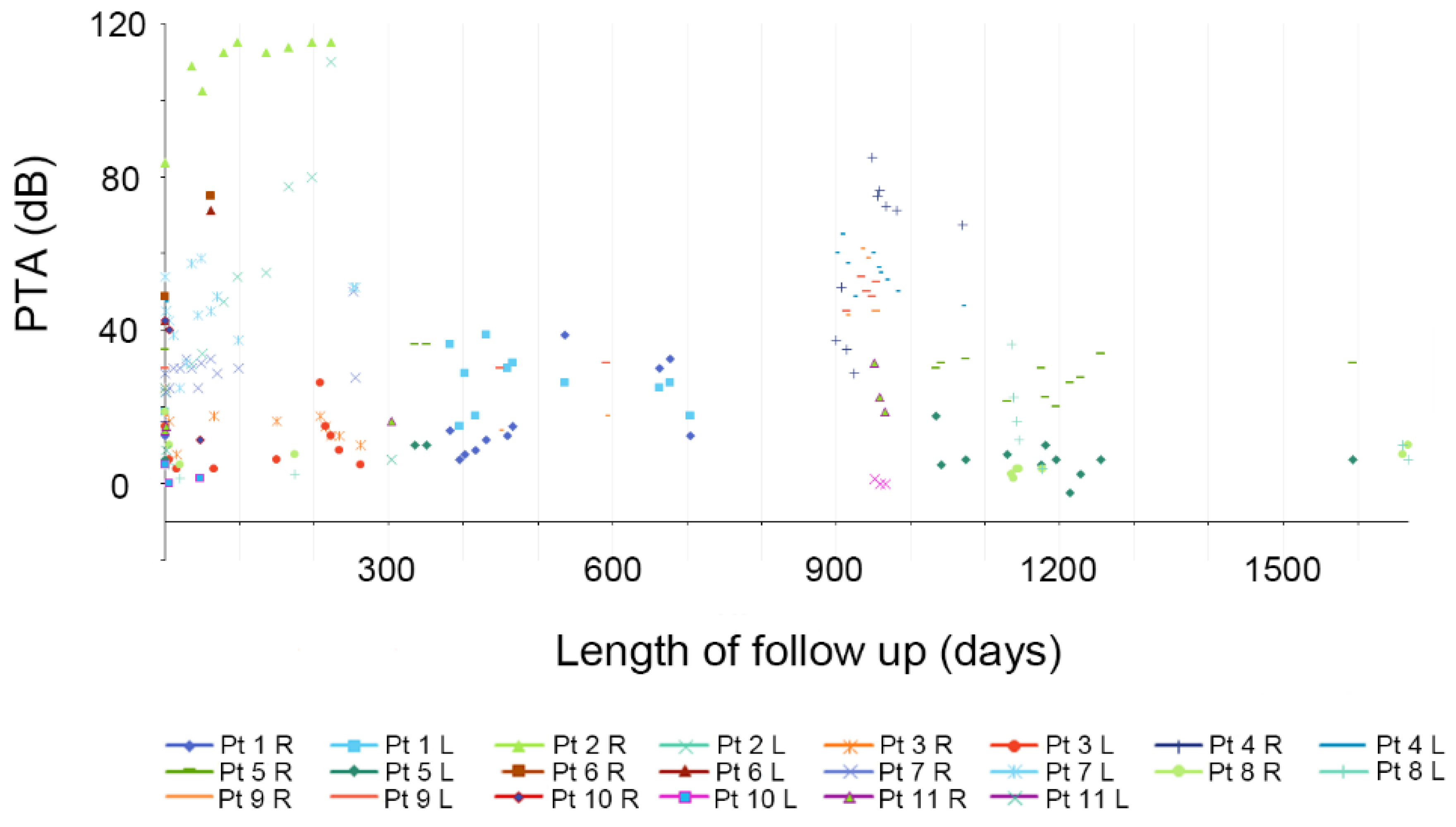

Among the 11 patients, hearing fluctuations were recorded in 22 ears with a PTA at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz, with the follow-up duration ranging from 2 to 101 months.

Figure 2 depicts the changes observed during the initial 5 years only.

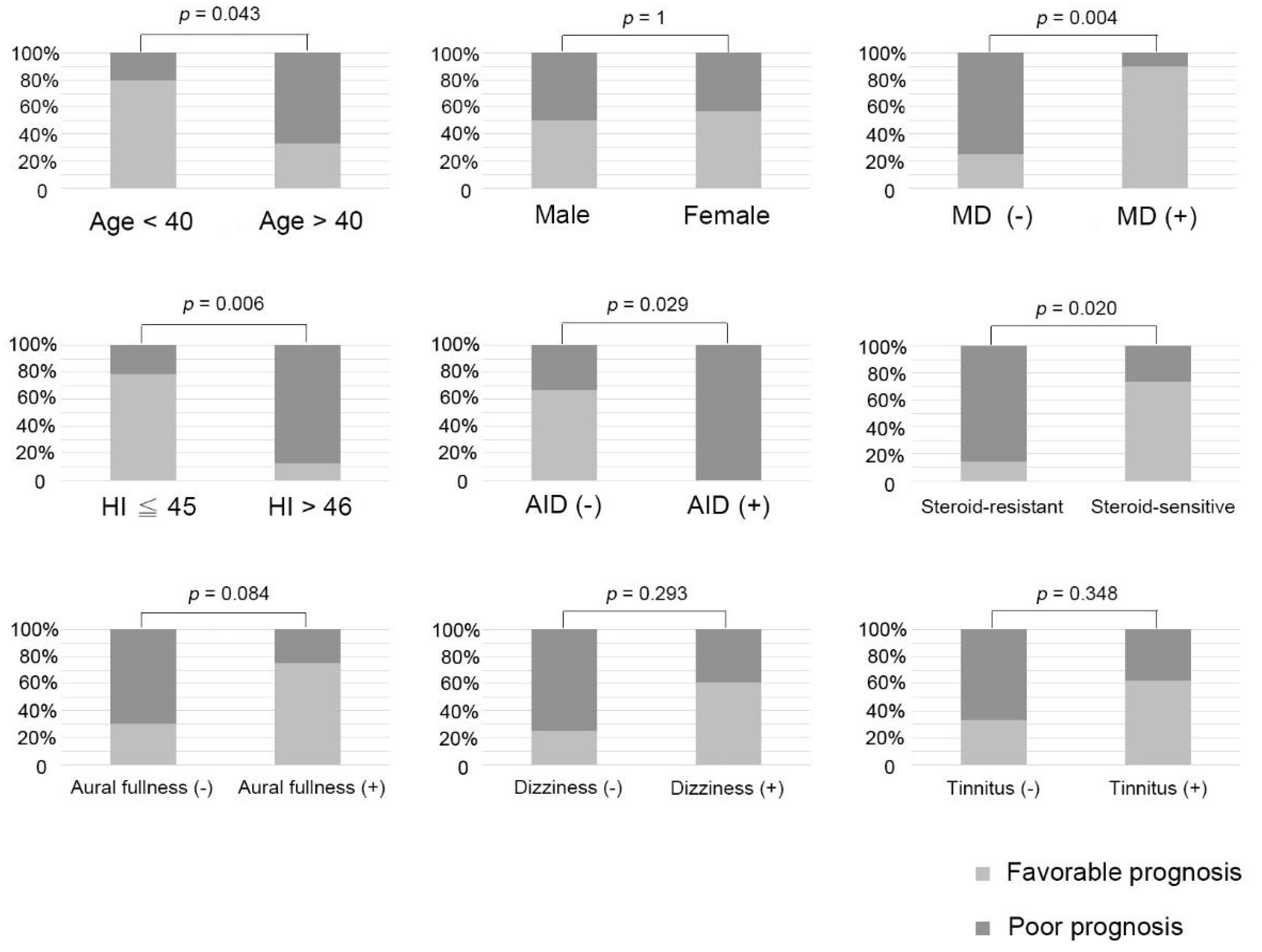

Our analysis encompassed several factors, including age, gender, severity of hearing loss at presentation, pattern of hearing loss, aural fullness, dizziness, tinnitus, history of autoimmune diseases, meeting the diagnostic criteria for bilateral MD, response to steroid therapy, and the time interval between HI attacks in contralateral ears. The association between these findings and prognosis is illustrated in

Figure 3. Given our limited sample size, we used Fisher’s exact test and considered hearing stability in patients as the final outcome. The 22 ears were divided into two groups: the favorable-prognosis and poor-prognosis groups.

Age analysis indicated a significant difference in the distribution of favorable and poor prognosis between the patients aged below 40 years and patients aged above 40 years (

p = 0.043). In terms of the severity of hearing loss at presentation, a hearing loss of 45 dB or less was defined as mild HI, whereas a hearing loss of more than 46 dB was defined as severe HI. The mild HI group had a much higher probability of CR (

p = 0.006). Analysis of the pattern of hearing loss (

Figure S1) indicated that the ascending pattern was predominant in the favorable-prognosis group, whereas the flat pattern was predominant in the poor-prognosis group, with the difference being statistically significant (

p = 0.001). This means that ascending audiograms were associated with a higher probability of recovery compared to flat audiograms, aligning with findings related to sudden hearing loss. Notably, there was only one case exhibiting a descending audiogram, but yielding no significant difference in this context.

Both patients with autoimmune disease had a poor prognosis (

p = 0.029). Among our 11 patients with hearing fluctuations, 5 met the diagnostic criteria for bilateral MD, and this group had a significantly better prognosis than those who did not meet the criteria (

p = 0.004). As shown in

Table S1, the average number of days before the patient responded to the steroid was 8.9 ± 10.3 days, with most individuals sensitive to steroids exhibiting a response within 2 weeks. Therefore, we considered 2 weeks as the cutoff point and divided the patients into a steroid-sensitive group and a steroid-resistant group. The steroid-sensitive group had a greater probability of CR (

p = 0.020). We calculated the time interval between HI attacks in contralateral ears and discovered that a longer time interval between attacks was associated with a better outcome (

p = 0.042,

Figure S2). However, the associated symptoms (i.e., tinnitus, dizziness, or aural fullness) had no significant associations with prognosis (

p = 0.384, 0.293, and 0.084, respectively), and neither did gender (

p = 1).

ROC curve analysis was conducted to evaluate the diagnostic value of these parameters in patients with AIED (

Table S2). The cut-off value of each predictor was as the following: Age ≤ 40 (AUC 0.733, sensitivity 66.7%, specificity 80.0%, 95%CI 0.516– 0.951,

p = 0.065), presence of bilateral MD (AUC 0.825, sensitivity 75.0%, specificity 90.0%, 95%CI 0.640–1.000,

p = 0.010), pretreatment HI ≤ 45 dB HL (AUC 0.808, sensitivity 91.7%, specificity 70.0%, 95%CI 0.610–1.000,

p = 0.015), no other immune-related disease (AUC 0.700, sensitivity 100%, specificity 40.0%, 95%CI 0.467–0.933,

p = 0.114), response to steroids (AUC 0.800, sensitivity 100%, specificity 60.0%, 95%CI 0.595–1.000,

p = 0.018), and ascending audiogram (AUC 0.858, sensitivity 91.7%, specificity 80.0%, 95%CI 0.683–0.858,

p = 0.005).