Introduction

The flexible, non-rigid weapons commonly referred to under the umbrella term of flails are probably one of the most contentious and misunderstood aspects of medieval warfare, (Lepage, 2005; Tzouriadis, 2017) particularly when considering the early and much of the high Middle Ages (up to 1250) in Western Europe, (Laking, 1920) despite their prevalence in modern media, such as film, videogames, (Sturtevant 2016a, 2017; Manning 2016; Fernandes, 2019; Dahm, 2018; Tardy, 2020, Moreno, 2015, Devereaux, 2019, Mondschein, 2017) and “popular history” writings. (Tunis, 1999; Dougherty, 2008) Some researchers argue the existence of flails and their use in warfare during the medieval period is primarily a fallacy, (Sturtevant, 2016a, 2016b, and 2017; Warner, 1968, O’Bryan, 2013) or at best, their provenance is overstated; (Manning, 2016; Oakeshott, 2012) arguments to both sides of the discussion appear in amateur and academic circles within the field.

I believe this is down to a poor awareness of period sources, (Farcas, 2016) many of which are available if not particularly easy to access, combined with an at-times poorly researched and sensationalist approach to “modern (and popular) medievalism”; (Tzouriadis, 2017; Utz, 2016; Gallardo, 2016) some of the more obscure references to flails were known to writers in the 19th Century. (Viollet-le-Duc, 1874; Sternberg, 1886; Oman, 1898) These can be acquired today with a little effort and have been studied to some extent by various researchers who reason that flails were common enough to be known to medieval peoples in Western, Central, and Southern Europe at least for some parts of the medieval era. (Gallardo, 2016; Moreno, 2015; Nilsson, 2021; Campagnano, 2015) Much of the well-known primary Western European sources for flails date from the later medieval era (post-1250), while sources from before this date are generally not well-studied beyond a few exceptions.

For the purposes of this work, I will consider four different categories of flexible weapons for the discussion, examples of which are presented in

Figure 1:

Threshing flails – farming tools used for millennia, but occasionally pressed into service as improvised weapons.

Weaponised derivatives of these which became popular in Europe from the 14th Century.

Scourges – sometimes incorrectly referred to as flails – are punishment devices rather than weapons, often depicted in religious settings and referenced heavily in the Bible. (Moreno, 2015)

War flails – a broad range of weapons including the “ball-and chain” type, which collectively are the primary source of contention around this class of weaponry and the primary focus of this work.

To my knowledge, there has been no recent effort to collate the various and disparate, but substantial body of evidence for flails and their use, which consists of a combination of artistic representations (statues, carvings, frescoes, manuscript illuminations, etc.), literary references, and archaeological finds, (DeVries and Smith, 2012; Nicolle, 1999) in the early and high medieval period within Western, Central, and Southern Europe, despite excellent work from researchers in the East of the continent and the Balkans highlighting the well-known use in those regions from as early as the 8th Century. (Kotowicz, 2006; Osypenko, 2019; Osypenko, 2020; Culic, 2016; Rabovyanov, 2016) As such, this work aims to draw together these sources and discuss their depictions and descriptions, highlighting the underlying period knowledge of flails, their use in warfare, associated symbology, political, and political importance within Western, Central, and Southern Europe in the early high medieval eras. I believe the collection of primary and secondary sources presented here is extensive but is by no means complete, and thus should not be considered exhaustive. Please note that while parallel development of flexible weaponry occurred during the medieval period across large parts of the world including Japan, (Gonzalez, 2013) China (Needham, 1958; Fauliot, 1982), Korea (Herrera, 2014), the pre-colonial Americas (Courville, 1948), and many other places, (Costa, 2015; Moreno, 2015; Gallardo, 2016; Escobar, 2018) these are beyond the scope of this work and will not be discussed further unless pertinent. The aim of this work does not include the development of weapon typologies but rather to provide a high-level overview and to highlight the previously underrated prevalence of flails within the region and period of interest by reviewing the available sources. A brief discussion of the likely historical use of flails in warfare will be presented, alongside some conclusions regarding the possible routes by which flails were introduced to Western, Central, and Southern Europe, likely before, but most certainly within the early medieval period; it was theorised that war flails migrated Westwards from Eastern Europe during the 10th-12th Centuries, but the provenance of many primary sources refutes this concept.

Much of the scepticism surrounding flails arise from the challenges in controlling such flexible weapons practically, with some researchers describing their motions as chaotic and as harmful to the wielder and their allies as to the enemy. (Sturtevant, 2016a; Moreno, 2015) As a riposte to this, several late Saxon (10th-11th Century) sources describe the ability of farmers to thresh crops without injury (Hill, 1998; Gallardo, 2016), and modern reproductions from 15th-16th Century “fight manuals” demonstrate comprehensively the opposite: with appropriate training and practice, flails are as controllable and precise as other weapons. (Rüther, 2023) The advantage of flails in their ability to “wrap around” shields, limbs, and weapons, (Zábojník, 2009) and hit at least as hard, if not harder than rigid weapons of similar weight and design (i.e. maces) with significant blunt force, (Rüther, 2022; van Dyke et al, 2007) makes them, hard to block, (Warner, 1968; Moreno, 2015) effective against certain types of armour, and especially dangerous under some circumstances. The “safe” use of flail in controlled environments, such as historical re-enactments, is a challenging balance to strike – maintaining the authenticity while also not risking serious injury to participants and observers alike. (Radtchenko, 2006)

Cultural and Literary Context

At this stage, it is pertinent to discuss the various historical and more recent translations of the overarching term flail into European languages, (Snook, 1979; Tihle, 2017) as even in modern parlance there is significant confusion and no uniformity in the many and varied terms used to describe such weapons in primary (Carley, 1962) and secondary sources. (Tzouriadis, 2017) In modern English, the flail as a weapon is sometimes referred to interchangeably as the war flail, morning star, or holy water sprinkler, while in Old English, the term fleel is used. In modern French, the common term is fléau d’armes (war flail), while in older texts, the term plomée is commonly utilised, though this has several meanings which will be discussed later; a few other less common terms will be highlighted as necessary, given the prevalence of primary French language sources. Modern German has several more descriptive terms, including Kriegsflegel (war flail), Morgenstern (morning star), Kettenmorgenstern (chain morning star), Streitflegel (lit. fight flail), and Schlachtgeissel (battle whip). In most Slavic languages (Polish, Ukrainian, Russian), the term kisten or kiścień, is used, with Řemdih and Remdik used in Czech and Slovak respectively. Modern Spanish and Portuguese use the term mangual, while Italian is mazzafrusto, with the period term flagellum and many other more specific derivatives. (Nicolotti, 2018)

The semantics of the term flail begin to become complex around the time of the Hunnic invasion of the 4-5th Century AD. The high medieval (1160-1170) poem Servaes Legende, attested to Heinrich von Veldeke (d. after 1184), based upon the previous Gesta Sancti Servatii (c. 1126) which found its roots in Historia Francorum (by Gregory of Tours, d. 594), describes the following exchange between Attila the Hun and the city of Troyes (the original texts are unavailable to me) (Bathgate, 1990):

“Then Troyes: Bishop Lupus asks Atilla (Attila), “why do you destroy the whole land?” Atilla (Attila) says, “I am God’s flail; open the gates, and I will thresh both woman and man!”

In this context, the flail of God Attila refers himself as being can be misconstrued due to a tendency of the meaning between flail and scourge to merge, though the reference to threshing means this requires somewhat deeper analysis. This merged meaning of flail and scourge arises from the Latin term Flagella, meaning flail (several types), and also scourge (the whip-type devices) to refer to, (Nicolotti, 2018) in the latter case, a scourge in its alternate definition as a source of great suffering or trouble. Similar observations are seen in French with the term fléau, where alone, this word refers to scourge, but with the suffix d’armes, refers to the weapons described here. (Havard, 1876) The evolution of language incorporated the further meanings of the word flail, at least in English from just the farming tool to the associated military definition primarily discussed here; (Izdebska, 2016) the chaotic flailing of threshing flails is indeed the origin of the modern adjective to describe wild circular motions (such as of the arms), representing a further branching of the semantics of the word. (Hill, 1998)

The epithet Flagellum Dei, meaning scourge/flail of God, was first loosely associated with Attila around the turn of the 7th Century, but had become a truly negative connotation referring to him by the 11th Century, at least within Western Europe; the Eastern Roman Empire (centred on Byzantium), held a much higher view of the Flagellum Dei. (Ridley, 1992) The Flagellum Dei epithet was also applied to the Lombards at times during and after their conquest of northern Italy (568-774), to the Hungarians (Williams, 1979) during their various invasions of Germany during the 10th Century, (Köstler, 1883) and also the Magyars and Pechenegs by the Byzantines during the 10th-12th Centuries. (Paron, 2021) Even certain Christians have been described as Flagellum Dei or rather fléau de Dieu – in reference to punishing the impiety of the Flemmings and English (under King John) at the battle of Bouvines (1214). (Leon, 2019) The late 14th Century French work L’Arbe des Batailles criticises violence as a scourge upon the land, but also recognises it as a punishment from God, who allows it to occur as a price for sins; the soldiers who provide the violence are, in this context the flail of God or les executeurs de nostre Seigneur. (Niewinski, 2019) The 15th Century French nobleman and general Jean de Dueil was labelled le fléau des Anglais (plague/scourge of the English) during the Hundred Years War, and (de Boislisle, 1943) the English solider Richard Bingham (1528-1599) was referred to by the epithet the Flail of Connaught for his oppressive actions against the Irish. (Herron, 2002) Indeed the term Flagellum Dei could be applied to “the enemy generally, regardless of their origin. (Allmand, 1999)

In a reversal of meaning from ancient times, by the early parts of the high medieval period (as attested in the Domesday Book), the flail had become a symbol of poverty and villeinhood, (Stoljar, 1985; Homans, 1941; Power, 1940; Hyams, 1970) remaining a symbol of servitude and menial (farming) labour well into the Renaissance, Beauchamp, 1984) although these labours were viewed in something of a positive light in the period, (McDougall, 1983) flailing being viewed as a metaphor for God’s struggles inflicted upon Christians to test the strength of their belief. (Lipton, 1999) To break from one’s designated place in society was at times seen as a threat to your betters, as the French epic poem Partonopeus de Blois (c. 1170-1180) describes – drawing upon the symbols of “plough, pitchfork, and flail” as those of servitude, warning against the perils of fils à villain (lit. “naughty son”) being raised from the dirt to those of higher office and political influence, directly wishing upon them significant misfortune. (Eley, 2011) This symbolism was further carried into the proto-science-fiction works of the English poet Edmund Spenser (1552-1599), who incorporated a flail into an “iron man” character named Telus into several of his works; the flail included as a symbol of servitude to his human masters. (McCulloch, 2011)

From the 13th and into the 14th Centuries, flails begin appearing in heraldic designs in Germany, such as those of Pflegelberg, (Erisman; Frutos, 2019; Moreno, 2015) with similar depictions (a lion holding a flail) noted in Aragaonese arms. (Clemmensen, 2013; Moreno, 2015)

Depictions and Descriptions of Threshing Flails as Improvised Weapons in Western, Central, and Southern Europe in the Early and High Medieval Eras

Threshing flails are ancient farming tools used to separate grains from stalks during harvesting, with their use in parts of Europe dating back at least two millennia, (Andrén, 2005) the latest occurrence being in parts of Scandinavia by about 1000 AD. (Myrdal, 1997) As symbols of the peasantry, along with the pitchfork and the scythe, threshing flails are more tools than weapons, but when push comes to shove, such implements can be turned on their fellow man as improvised weapons, a practice which is generally accepted by historians. (Moreno, 2015; Gallardo, 2016) The Greek philosopher and mathematician Euclid is reported to have considered it “a futile labour [to teach mathematics to those who toil with] flail and axe”, indicating that the users of such tools were not worthy of being raised up intellectually. (Gug, 1985)

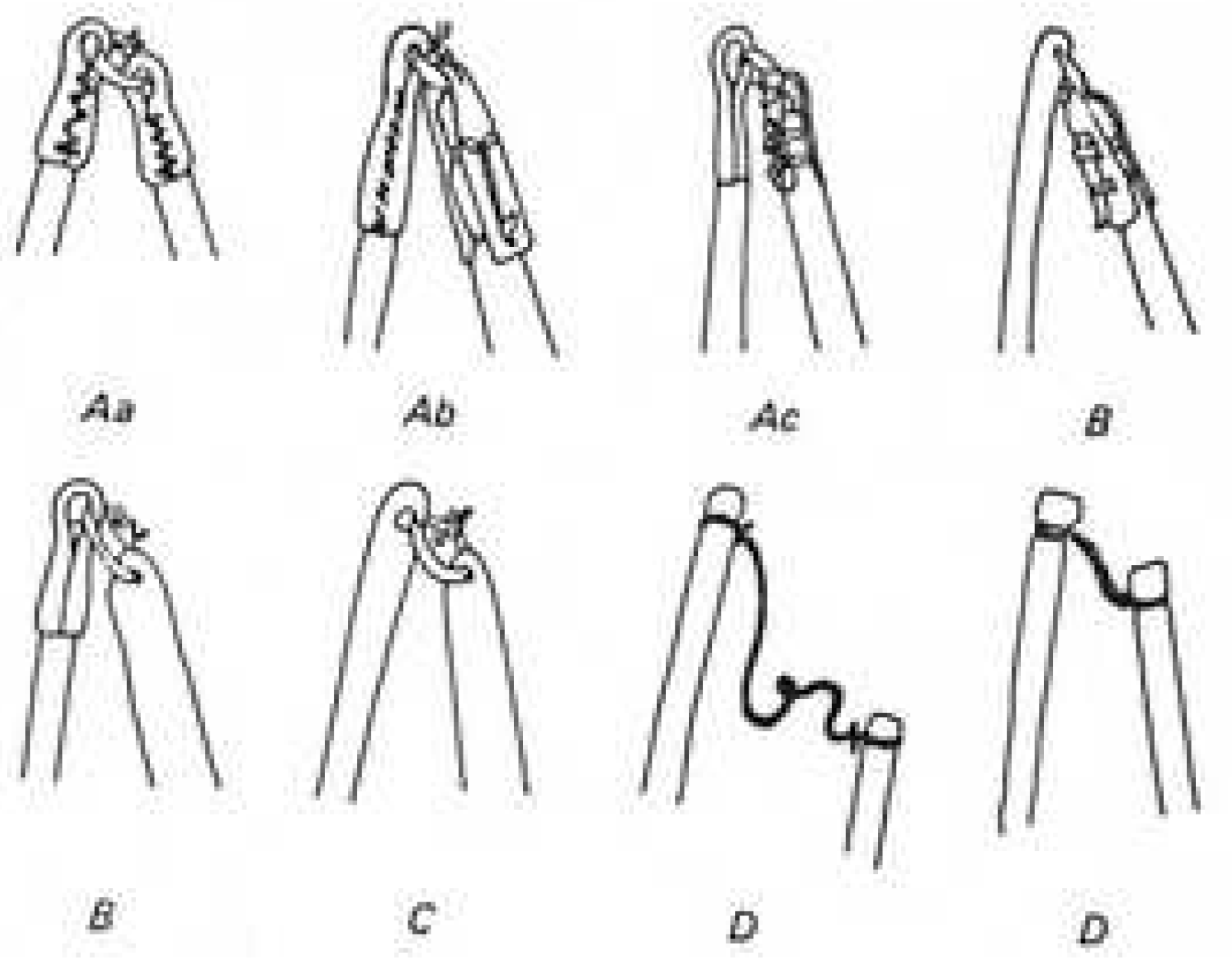

In Irish custom, the haft of a threshing flail was usually made of ash, while the beater (swingle or souple) could either be made of ash, hazel or holly. (Mac Coitir, 2020, Newman, 1985) Various means exist of attaching the two portions of a threshing flail together to ensure sufficient flexibility of the head, with the exact design employed varying with locale of manufacture, (Newman, 1985) the minutiae of which are beyond the scope of this work, though a selection of hinges is presented below. (

Figure 4, Veiga de Oliveira, 1983) The primary sources describing threshing flails as improvised weapons are now presented and discussed..

(A) The Gaelic folklore tradition describing the legend of Finn mac Cumaill (Fionn Mac Cumhaill) likely dates from before the high medieval period, but references to the death of this character and a particular scene described in hell are found from the 10th Century, becoming a key part of the story by the 12th Century. One of the other characters in the story (Oscar), is described as using a flail in hell to keep demons away, which is later transferred to the titular character in some variations of the story. (Macculloch, 1916) The flail described is “like that used for threshing grain”, but via divine favour (via an angel), the flail strap is made so that “it will last” – and made more durable. (Maher, 2018; O’Hogain, 1987) This provides an interesting example of a threshing flail being used in a folklore setting as an improvised weapon.

(B) In the 19th Century writing The History of Normandy and of England, Palgrave describes the “proud Norman peasantry” mustering and rising up and mustering with an assortment of weapons including (threshing) flails to fight the English (Saxons?) and Germans invading Normandy during the time Duke Richard II (r. 996-1026) and later regents, during battles at Bihorel, Maromme, and on the Contentin peninsula (near Cherbourg), though period sources for these references are not provided. (Palgrave, 1864)

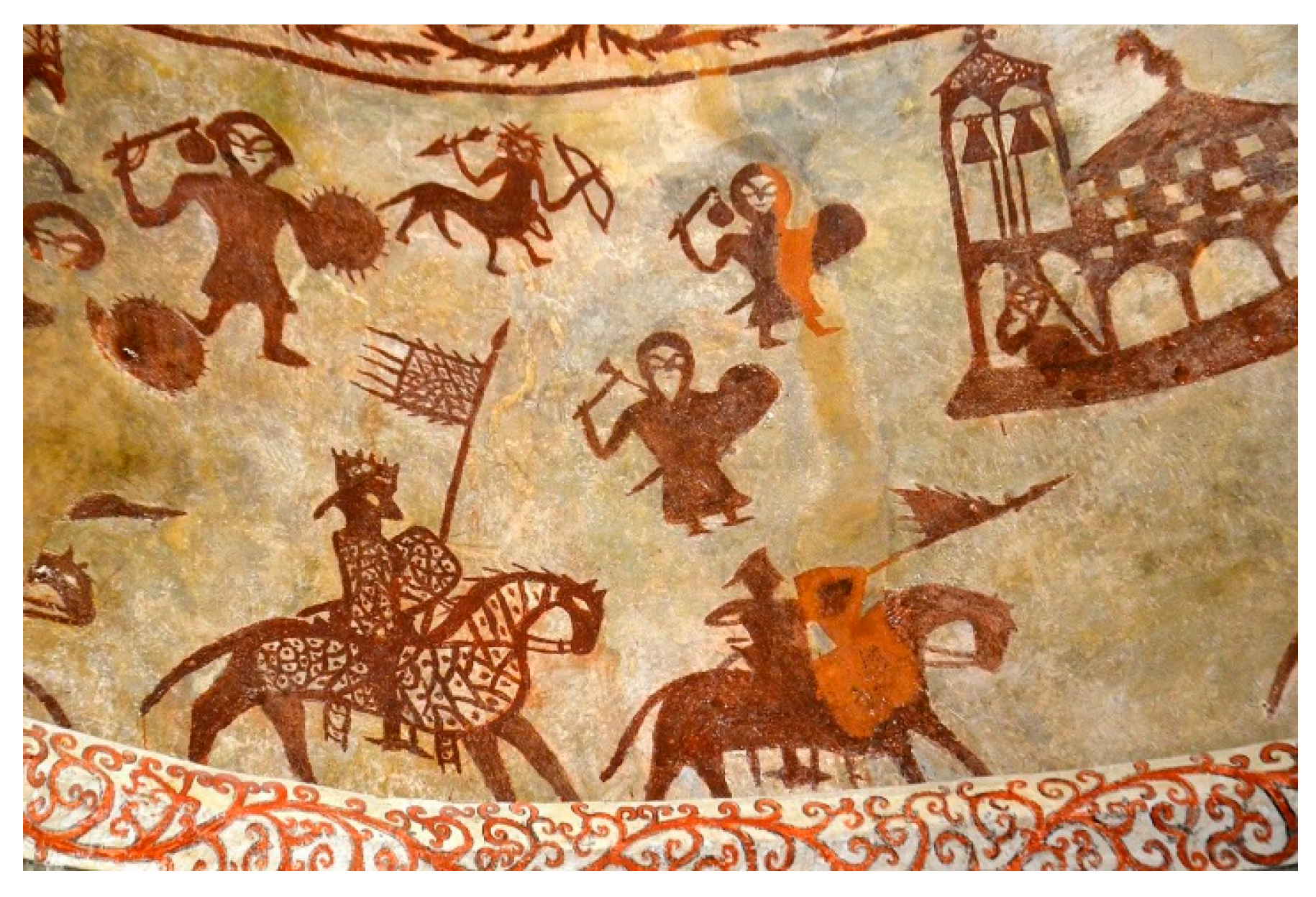

(C) A 12th Century fresco in the Royal Mantheon of San Isidoro (Spain), depicts peasant militias (described as pawns from the town of Bernesga, Spain, in modern references) armed with threshing flails supporting noble cavalrymen in battle. (Moreno, 2015, Gallardo, 2016)

(D) The Welsh tale Culhwch and Olwen, is connected to the legend of King Arthur and his Warriors and believed to originate orally from the 11th or 12th Century, though only manuscripts from the early 14th and 15th Centuries survive. The physical strength of one of the characters (Cacamwri, a servant of Arthur) is demonstrated by rending a barn to dust with a threshing flail. While allegorical and most certainly prone to the author’s exaggerations, this does highlight the period knowledge of the potential of a flail as a tool of destruction. (Toffee, 2013)

(E) The early 12

th Century illuminated manuscript from Citeaux, an illustrated version of the earlier

Moralia in Job (Dijon BM MS.173,

Figure 5) depicts a folio (fol. 148r) of a threshing flail in what is described by Thompson as “a humorous play on the flail of God (

Flagellum Dei) described in the book”. (Thompson, 2000) This work is associated with Pope Gregory the Great (d. c. 604), of which many reproductions were produced over the subsequent centuries.

The figure and the flail form a contorted “S” shape as an enlarged dropped first letter of the page, and represent one of the better depictions of the “hinge” of a threshing flail in period illustrations. In the context described in her thesis, (Thompson, 2000) based partly upon the interpretation of the work of Rudolph, (Rudolph, 1997) Thompson postulates that the folio represents the “spiritual struggle” and as such this can be likened to the use of the flail as a weapon to ward off temptation. (Thompson, 2000) This may have had a greater connection to the working classes intended by the author of the manuscript, but this is open to speculation.

(F) The poet Wace described in his mid-12

th Century chronicle

Roman de Rou, the mustering of the Saxon peasants (fyrd) for the Battle of Hastings with (pitch)forks amongst other weapons and tools they had to hand. (Planché, 1876) Here, the word “tinels” is used – referring to “heavy wooden implements” – perhaps clubs or flails.

| “Li vilains des viles aplouent |

| Tels armes portent com ils trouvcnt; |

| Machus portent e grans pels |

| Forches ferrdes e tinels.” |

| “The villeins of the towns applaud (gather?) |

| The arms bear where they find |

| March forth...? |

| Forks of iron and [heavy wooden implements].” |

(G) During the Anarchy (1138-1153), the English war of succession that followed the death of Henry I (d. 1135), a power struggle between two rival strands of the royal family resulted in numerous campaigns across England and modern-day France. One secondary source attests to, as with the later description of Jordan Fantosme (see below), the “peasants and churls turning out and driving the hated Guirribecs back over the border with fork and flail”, (Green, 1888) though no original, period reference is provided to corroborate this. In this context, “Guirribec” was used a derogatory term for the Angevins who were likely suffering from dysentery. (Bradbury, 1990)

(H)

Van den vos Reinaerde (the tale of Reynard the Fox in Middle Dutch) is a mid-12

th Century German tale (c. 1250 for the Dutch translation) telling the story of anthropomorphic animals in a manner comprised of both human and animal behaviours. In the tale, a bear is harassing a village which rouses the characters to gather their arms, a (threshing) flail (vhlegel) and pitchfork included, to kill the bear (Bouwman and Besamusca, 2009):

“Sulc was die eenen bessem brochte,

sulc eenen vleghel, sulc een rake,

sulc quam gheloepen met eenen stake.” |

(I) One of the earliest primary references I’m aware of where threshing flails are used as improvised weapons outside of a fictional setting comes from The Chronicle of the War between the English and the Scots in 1173 and 1174 by Jordan Fantosme (107). (Hosler, 2017; Day, 2010; Clark, 2018; Short, 2022) He describes their use against Flemish mercenaries alongside (pitch)forks:

“N’i aveit el païs ne villain ne corbel / N’alast Flamens destruire a furke e a fleel”

“In all the countryside there as neither villein nor peasant who did not go after the Flemings with fork and flail to destroy them... ...by fifteen, by forties, by hundreds and by thousands/ by main force they make them tumble into the ditches … Upon their bodies descend crows and buzzards/ who carry away the souls to the fire which ever burns’”

In this context, given the specific reference to the villains and the known symbology of “fork and flail” as those of servitude and the lower classes, he must be referring to threshing flails as tools of the peasantry. Matthew Paris repeats this tale in his Historia Anglorum (c. 1250-1259). (Oman, 1898)

(J) The late 12th Century French romance Perceval ou le Conte du Graal (Perceval and the Story of the Grail) is an Arthurian tale written by Chretien de Troyes (fl. 1160-1191) which describes the story of the titular character on the quest for the holy grail (not the cup as per modern adaptions of the story). In the story, Gawain is accused of murder causing (to quote McDowell) “every single rogue to snatch up a pitchfork or a hammer or a flail”, the mob threatening to tear apart the tower of Gawain. (McDowell, 2007) In this context, the flails described would be threshing flails, being tools used as improvised weapons. The original text of the Perceval ou le Conte du Graal is unfortunately unavailable to me.

(K) It seems that threshing flails were not only employed as occasional improvised weapons but at times as implements of domestic violence – in the early 13th Century, a Hereford bailiff by the name of Robert Praepositus “struck his daughter in the eye with a flail and the eye was lost”. She survived the ordeal and went on to marry. (Hillaby, 2006) A similar court entry was recorded in Shropshire in 1256. (Skinner, 2017)

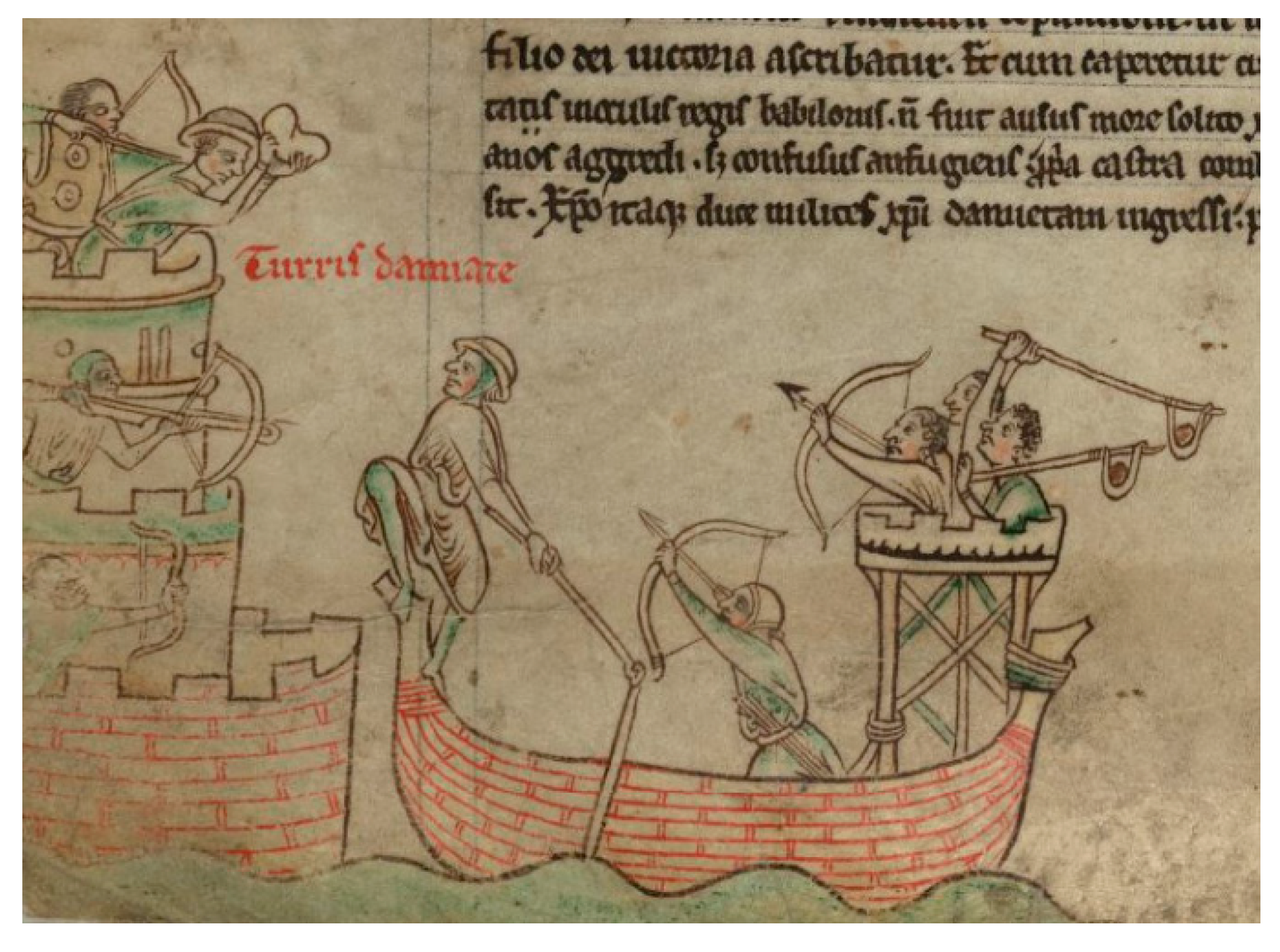

(L) Fol. 59v from the

Chronicle of the Fifth Crusade (Corpus Christi MS 016II, Chronica Maiora II,

Figure 6) by Matthew Paris (d. 1259), dated to the mid 13

th Century, depicts the Frisian Hayo von Wolvega attacking the Tower of Damietta (modern-day Egypt) with a threshing flail as an improvised weapon during the 5

th Crusade (1217-1221). (Day, 2010; James, 1925, Hewitt, 1855; Moreno, 2015)

This illumination likely stems from the testimony of Oliver of Paderborn (c. 1170-1227) who accompanied the 5th Crusade to the Holy Land. In his Historia Damiatina, “a flail by which grain is usually threshed” was weaponised by “interweaving it” with chains. Whilst this feature is omitted from the folio below, (Edwards, 2019; Edbury, 2016) it is a strong candidate for early “weaponising” threshing flails as is discussed later.

(M) Improvised threshing flails were still in use later in the medieval period (13th-14th Centuries) by the entrenched lower classes as well, especially in resistance to expansionist tendencies of land-hungry nobility of differing ethnicities, (Zientara, 1970) even predating the use of weaponised-type threshing flails during Hussite Wars (1419-1434) by at least a century. (Moreno, 2015; Wasiak, 2012; Tihle, 2017)

(N) One of the more interesting folios from the early 14

th Century (c. 1330) manuscript

The Taymouth Hours (BL Yates Thompson MS13, f185v,

Figure 7) depicts a shortened threshing flail in the hands of a half-man half-lion (or other big cat) also carrying a (conical wicker?) shield with a gigue strap. (BL Catalogue) To my knowledge, this is the only depiction of this kind of flail within early-high medieval sources.

(O) In the Celtic folk tale of Irish or Scottish origin, entitled The Battle of the Birds, the birds in the story are described as using flails as weapons to fight the mice, with the more modern, translated text specifically mentioning threshing flails being utilised as improvised weapons, albeit in a fantastical setting. The story and its variants were first recorded in the 15th Century but is believed to be much older in origin, due to the prevalence of similar tales across Europe and into Asia. (Jacobs, 1892)

(P) A tale entitled the Lad with the Goat Skin tells the fable of a young smith of Dublin who, smitten with a princess, is bidden by the King of Dublin to collect a (threshing) flail from hell which is told to be feared by the Danes harrying Ireland at the time. (Kennedy, 1866; Jacobs, 1892) As with many folk tales, this piece is first referenced in the medieval era, but given the context of the tale, the story is likely a few centuries older, before the invasion of Ireland by the Normans in the 12th and 13th Centuries. (Kennedy, 1866; Jacobs, 1892) The overall structure of the story mirrors that of the c. 1200 French (possibly Breton) story Lai d’Eliduc (the lays of Eliduc), though there are no specific references to flails in that piece that can be determined, although war is described as “fléau de la guerre” – lit. “the scourge of war”. (de France, 1820) The 19th Century illustrations accompanying these two tales illustrate them as threshing flails. (Jacobs, 1892)

Depictions, Descriptions, and Archaeological Finds of War Flails in Western, Central, and Southern Europe in the Early and High Medieval Eras

In contrast to Eastern Europe and the Balkan, where physical finds of flail heads predominate, in Western, Central, and Southern Europe, primary textual and artistic references (carvings, statues, illuminated manuscripts, etc.) are far more common. (Hrynchyshyn, 2014; Taavistainen, 2004; Kotowicz and Skowronski, 2020; Imiolczyk and Zdaniewicz, 2022; Shpakovsky and Nicolle, 2013) The reasons for this may be twofold: firstly, the challenges arising in accessing Eastern European textual and artistic sources due to language barriers and present geopolitical tensions; and secondly, the misidentification of many archaeological finds outside of the Eastern regions of Europe, which may in fact be flail heads rather than weights or other artefacts, as discussed later.

Here I attempt to present all primary (and some secondary) sources available to me. Readers will note the somewhat extensive literary references to flails in the various medieval national matters, for to quote Jean Bodel (d. c. 1210) in La Chanson des Saisnes (Song of the Saxons):

“Ne sont que III matieres a nul home antandant: De France et de Bretaigne et de Rome la grant.”

“There are only three subjects matters for any discerning man: That of France, that of Britain and that of great Rome.”

I will highlight references to flails where present within the various chansons, poems, and other works of folklore, but please note that this is not an exhaustive list but based more upon the abundant secondary sources which cite and mention these; translations are approximate based upon the availability of original texts, translated versions, and dictionaries, where these are available. Furthermore, some of the references poetic or textual references may predate their first recorded written examples by a significant amount of time (decades or even centuries) when drawn from oral histories of their parent peoples, as these were commonly adapted and changed over time. Where possible, a commentary of the apparent construction of the weapons depicted, and on the reliability of the source(s) is provided. The sources are presented in approximate chronological order. In some cases, the original texts are not available, where I would refer readers to the cited secondary sources are cited for guidance. Several questioned depictions are also highlighted and where these have been suspected over the years, this is discussed along with previous assessments as to their authenticity.

(I) Flails are described in use by the Bretons to fight off the Northmen (Vikings) during the late 9

th and early 10

th Century in a ballad referring to the Breton leader Alain Barbe-torte (Alan II, Duke of Brittany, c.900-952). Flails are described thusly (in Breton, translated French, (Villemarqué, 1846) and English):

“Ar Vretoned a weliz o vac’h el leur e louc’h

Ken a lame pellenou demeuz ar pennou blouc’h

Ha ne ket gant fustlou prenn a vac’h ar Vretoned

Nemet gand sparrou houarned ha gand tried ar virc’hed.”

“J’ai vu les Breston batter le blé dans l’aire foulée

J’ai vu voler la balle arrachée aux épis sans barbe.

Et ce n’est point avec des fléaux de bois que batten les Bretons

Mais avec des é[ieux ferres et avex les pieds des chevaux.

“I saw the Breton batter the wheat in the stomped area

I saw the chaff fly off the beardless ears

And it's not with wooden flails that the Bretons strike

But with iron spikes and horses' feet.” |

The type of flail utilised is not comprehensively described, but the reference to iron suggests this is a weapon rather than a threshing flail as described in some other folk tales later. The “Saxons” mentioned here are the Norse, due to the related (Germanic family) languages spoken by the two peoples. (Spence, 1917)

(II) Flails (schlachtgeissel – lit: “battle whip”) are attested as being used in 10th Century Germany during the second Battle of Lechfeld (955) in which Kingdoms of Germany and Hungary clashed; these are described as consisting of a short wooden handle with three or four chains, at the end of which an iron ball studded or filled with lead was attached. (Köstler, 1883; Bánlaky, 1928) This account may arise from the Annales Altahenses or similar period document. (Pohl, 2004; Négyesi, 2003) Bánlaky suspected that the Schlachtgeissel originated from the Frankish Empire, and its use was passed onto the Carolingian successor states, used as a secondary or tertiary weapon by the German cavalry, (Bánlaky, 1928; Jócsik, 2022) as was also likely the case for the Steppe peoples who first introduced such weapons (kistens) to Europe. (Zhirohov and Nicolle, 2019) The flail may have been introduced to the Carolingians by the Huns. (Gotzinger, 1885; Jahns, 1880) If this were the case, a likely explanation is provided for the significant prevalence of flails in the many tales of the Matter of France, England, and further afield. A plethora of 10th and 11th Century grave finds from present-day Central and Eastern Hungary would support the notion that flails were also used by the Magyars (fighting for or with the Hungarians) during this time period. (Jócsik, 2022)

(III) The Welsh poem Geraint uab Erbin (Geraint, son of Erbin) is believed to originate from the 10th or 11th Century, but the earliest surviving version dates from c. 1250 (the Black Book of Carmarthen, in Welsh). (Bollard, 1994) A dwarf character in the poem is described as using a flail (type not specified) to “whip the queen’s companion” (a knight). (Fee, 2018) I do not have access to the original text, this reference is taken from the work of Fee. (Fee, 2018)

(IV) Courville claims that the “morning star” style flail was introduced into England with the Norman conquest and was used for four hundred years following this, alongside extensive adoption in Teutonic (German) and Slavic Europe. (Courville, 1948) For the first two cases, the limited evidence of flail type weapons (known examples and references presented here) render his position for the first two points obsolete – we can verify a limited knowledge and adoption of flails in England and Western Europe, but not to the significant extent observed in Slavic lands. Hewitt considers that “stone flails” were used by the Saxons at Hastings, but this is likely a misinterpretation of the source (William of Poitiers, d. 1090) cited. (Hewitt, 1855) This demonstrates the inaccuracies sometimes incurred in dealing with secondary sources, especially those from Victorian times and less recent works, in addition to those where the authors are not subject matter experts regarding their writings, (Hewitt, 1855, Cuming, 1854; Cowper, 1906; Demmin, 1911; Snook, 1979) though there are outliers in this respect. (Schultz, 1889; Viollet-le-Duc, 1874; Sternberg, 1886) Modern advances in science and understanding around medicine and historical recreation and interpretation have further allowed us to cast doubt on certain more classical sources in light of new evidence and lack of a “rose-tinted view” of the medieval era. (Tracy and DeVries, 2015)

(V) A war flail is reportedly depicted in a carving (statue) of one of the founders (

Stifterfiguren) of Naumburg Cathedral (Germany,

Figure 13), possibly dated to the late 11

th Century, (Moreno, 2015) though this may be mis-dated and actually be a later creation from the 12

th or early 13

th Centuries, or fabricated in secondary sources of dubious accuracy. (Dona, 2021; Schultz, 1889; Demmin, 1911)

The weapon depicted is a ball and chain type flail with a smooth ball. I have been unable to find more recent images of this purported depiction. The other items depicted in the figure do provide a spread of late-Medieval flail designs, however, some of which are based on extant objects.

(VI) One of the earliest depictions in Southern Europe is a late 11

th or possibly early 12

th Century mosaic depicting the “Kiss of Judas” or the “Betrayal of Jesus” from the Basilica di San Marco (St Mark’s Basilica, Venice, Italy,

Figure 14), depicting a mob armed with an assortment of weaponry including a ball and chain flail, a spiked flail, and a very uncommon double-headed flail alongside lanterns, torches, and two-headed axes.

The colours present in the artwork suggest the author intended to convey the use of metal (iron) flail heads on wooden hafts. As these are in the background of the image, no more detailed information regarding the dimensions of these weapons can be ascertained. This does demonstrate knowledge of these types of weapons in Italy by the end of the 11th Century at the earliest, or the early 12th Century at the latest. Their presence in a mob-like setting reinforces the stereotype that such weapons were used by pagans or heathens. (Tihle, 2017)

(VII) A similar depiction is presented in the Queen Melisende Psalter (fol. 7v in BL Egerton MS 1139,

Figure 15), believed to have been prepared in Jerusalem c. 1130-1140, as part of a mob arresting Jesus, one of the weapons depicted is clearly a ball and chain flail, in addition to spears, maces, and torches. The colouring of the folio indicates the flail depicted has an iron head and chain on a wooden haft.

(VIII) War flails are not just depicted in military or mob-like settings, several images of demons wielding flails are present in both illuminated manuscripts and carvings present on churches. For example, L’Eglise Sainte-Foy de Conques (Abbey Church of Sainte-Foy, Conques, France,

Figure 16), completed c. 1125, contains an elaborate carved arch above the entranceway depicting a battle between angels and demons, the latter of which are armed, amongst other things, with a long shield, and axe, and a war flail (

Figure 76). (Deschamps, 1941; Denny, 1984; Moreno, 2015) This depicts a scene entitled “The Last Judgement”, as per the depiction in Winchester Psalter shown below.

(IX) Similar depictions are shown in the

Winchester Psalter (c. 1150, England, BL Cotton MS Nero C IV,

Figure 18), where during a scene titled

The Final Judgment, a pair of demons armed (centre and left of the figure) with war flails are presented tormenting the damned alongside several others armed with pitchforks. (Denny, 1984; Moreno, 2015) The form of the flails presented here is very much of the ball-and-chain weapon type, rather than scourges (discussed earlier) as are oft-depicted in monastic or biblically focused manuscripts; the handles appear to be ~2/3 the length of the overall weapon, with the flexible portion being the remaining 1/3 of the total length. This demonstrates a certain awareness of these devices within England by the mid 12

th Century.

The Anglo-Norman

Roman de Brut (c. 1155), translated and adapted from the Latin

De gestis Britonum or Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain) by Geoffrey of Monmouth (c.1095-1155) by the poet Wace (c.1110-1175) describes

plomées being used during a siege, (de Lincy, 1836) though in this context, this likely refers to leaded projectiles possibly hurled from slings, rather than flails, once again demonstrating the multifaceted meanings of many medieval words.

|

“Li Romain as murs les atendent

Qui à mervelle se desfendent...

...Lancent dars et plomées ruent

Maint en abatent et maint tuent”

“Romain had walls waiting for them

Which were wonderfully defensible...

...Arrows flew and [lead (ed projectiles)] were thrown

Many were cut down and killed...”

|

(X) The 12

th Century manuscript

La Chanson de Jerusalem describes flails (possibly threshing flails (as

plomées), though these are also described as “large clubs with dangling chain”) being wielded by the Tafurs (Frankish Catholic zealots who adopted a vow of extreme poverty) during the 1099 Siege of Jerusalem. The Saracens are described as being similarly armed (perhaps with ball and chain flails), one of whom “smashed a flail down on the King of the Tafurs... (leaving him) dripping with blood, the blow from the flail having smashed his nose and badly damaged his head and brains”. Two Christian knights (Eurvin of Creel and Wicher the German) are noted as being similarly set upon by “infidel pagans... wielding large thick maces and hinged flails, big lead clubs...” This piece clearly describes flails of various types being used by both sides during the First Crusade (1096-1099). (Sweetenham, 2016; Esposito, 2018)

|

“Ha! Dex! La n’ot mestier gius ne gabbi ne ris.

Bauduïns de Belvais fu navrés ens el pis

Et Harpins de Boorges devant en mi le vis

Et Ricars de Calmont estoit el cief malmis

Et d’une grant plomee ferus Jehans d’Alis

Si que li ber en ert encor tos estordis. (vv. 2374-2379).”

“Anuit m'est avenus uns damages mortals,

Al besoing m'ont fali nostre malvais deu fals.

Mais tant les ferai batre de fus et de tinals

Et de maces plomees, de bastons et de paus

Que ja mais n'aront cure de tresces ne de bals! (vv. 1762-1766)”

“Cascuns porte en se main u maçue u baston,

Plomee u materas et piçois u bordon

U gisarme aceree u grant hace u piçon. (vv. 1823-1825)”

“Es vos le roi tafur par mi .I. sablonal

A .X.M. ribaus : cascuns tient hoe u pal

U gissarme u picçois d’acier poitevinal.

Portent mals et flaiaus, fondefles et mangal. (vv. 1982-1985)”

“Portent haues et peles et grans fausars et pis,

Gisarmes et maçües et mals de fer traitis,

Trençans misericordes et cotels couleïs

Et plomees de coivre a caaines assis.

Li auquant portent fondes, molto nt caillos coillis (vv. 3012-3016)”

“Es vos le roi tafur et dant Pieron corant

Et Tafurs et Ribals qui molt vienent huant:

N'i a cel ne port hace u macüe pesant,

Coutel u grant plomee a caaine pendant,

U pouçon u piçois u alesne poignant.

Li rois tafurs tenoit une grant fauc trençant,

Entre paiens e mist, tant en vait craventant

Que par mi les ocis ne pot aler avant. (vv. 5912-5919)”

“Des mors et des navrés vont la terre covrant,

Fors de Jerusalem les mainent reculant.

Tos tant fierent sor els a tas demaintenant,

As grans maces de fer les vont jus craventant

Et as grandes plomees contre terre tuant.

Del sanc as Sarrasins i ot plenté si grant

Contreval le fossé en vont li riu corant. (vv. 7546-7557)”

|

(XI and XII) The

Song of Roland (Chanson de Roland), is a French epic poem possibly be written by the poet Turold (Turoldus in the manuscripts themselves) around the turn of the 11

th Century (est. 1040-1115), which describes the battle of Roncevaux (778) from the time of Charlemgane. (Thibout, 1966) One of the characters in the poem, Olivier (Oliver), is stated as using a ball and chain flail, with depictions of this character in various medieval locations including as a gate guardian at the Cathedral of Verona, Italy (c. 1139,

Figure 19), (Monfrin, 1965; Thibout, 1966; Beaud, 2017; Spiro, 2014; Moreno, 2015; Agrigoroaei, 2018) depicted opposite from Roland who is more conventionally armed (with sword and shield) and armoured in maille.

As the Song of Roland was composed around the time of the second crusade (1145-1149), coinciding with the liberation of parts of Spain and Portugal from the Moors and thus mirroring the deeds of the champions (or perhaps nephews?) of Charlemagne (Roland and Olivier), the time from which the story is believed to originate. (Spiro, 2014; Meneghetti, 1990) Roland is postulated to have been the nephew of Charlemagne, while Olivier could be an allegory for St. Romanus. (Dona, 2021)

The characters in period poems such as the Song of Roland are often transcribed into biblical or religious settings when illustrated or turned into physical carvings, with associated religious meanings attached to them. (Kahn, 1997) Beaud notes that in much of the epic literature (c.f. the Matters of France and Germany, and biblical depictions), flails are most commonly shown being used by “bandits, peasants, and pagans... are pejorative for the wielders...”. (Beaud, 2017) In use by the paladin Olivier, the meaning of the flail may be reversed, perhaps as an iconographic representation of divine rebuke transferred by the blows of the weapon. (Beaud, 2017) There has been speculation as to why Olivier is depicted unarmoured, (Dona, 2021) but the fact he’s carved carrying a shield indicates the stance of a warrior, rather than any more pacifistic option. Several archaeological finds present in the Abbey of Rencesvalles (Spain) are attested by some 16th Century sources to the flail of Olivier, but these are believed to be late medieval replicas or forgeries. (Dona, 2021)

(XIII) The mid-12

th Century French epic

Prise d’Orange (lit. “Taking of Orange”, originally written in Old French) describes the exploits of the hero Guillaume, who captures the walled city of Orange (France) from the “Saracens” (Moors, see below). Guillaume’s wargear is described in somewhat exaggerated terms in the original text, and includes, amongst other things, a

fléau d’armes, though this is referred to as a

plomée in the period text. (Cazanave, 2013; Sternberg, 1886) As with many of the similar French chansons, the origin of this particular story dates from the time of Charlemagne. An excerpt from the

Prise D’Orange (IV, 241) (Schultz, 1889) is presented:

|

“S’o ot plomées et maint fanssart pesant

Et maintes maces et espées tranchanz”

|

(XIV) Some degree of confusion arising from the multiple meanings derived from certain words can be evidenced by references to the

plomée in the

Roman de Thebes (Romance of Thebes), is a mid-12

th Century (c. 1150-1155) French epic poem believed to be an abbreviated and adapted version of the classical

Thebiad. The story is fitted to 12

th Century French methods of warfare and chivalric code, and includes several references to the use a plomée, (Constans, 1890; de Lage, 1966), at least one of which refers to something akin to a discus (v. 230-234 presented below), (Mosca, 2020; Ferlampin-Acher, 2007) while others are clearly in reference to the “leaded mace” or flail (v. 33-37 and 4175). (Mora-Lebrun, 1995) This story was also likely adapted into the late 12

th Century Anglo-Norman

romans d’aventures entitled the

Ipomedon and the sequel

Protheselaus.

|

“N’i avoit pas esté grant pose

que es geuz sort une mellee

par la raison d’une plomee (discus)

que li danzel iluec gitoient,

qui de giter mout se prisoient”

“Car il n'ont pas escus de chesne,

Espiés de fer, hanstes [de] fresne,

Elaives ne lances ne espees,

Maces de fer ne granz plomees (flail)

For solement danz Jupiter,

Qui tint un dart agu de fer.”

|

(XV) One of the earliest examples of a multi-headed flail is presented in a folio (97v) from the German manuscript

Stuttgarter Passionale – Par Hiemalis (cid.bibl.fol.57,

Figure 20), dated between variously 1130 and 1175. This folio depicts an unarmoured man wielding a three-headed ball-and-chain flail in one hand. The illustration is lacking the colour of some other depictions, but we can infer from the black hue of the balls and chains that this was intended to represent construction of iron. The balls of the flail present are round in nature, rather than spiked as in some contemporary depictions. The digitised images cut off two of the balls of the flail, but these are clearly visible on the opposite page, as pictured. As with one of the threshing flail depictions presented above, this image is worked into a highly-stylised letter.

(XVI) The use of flails outside of Western, Central, and Southern Europe continued in earnest throughout other parts of the known world, including the Byzantine Empire. Several folios from the Madrid Skylitzes (dated mid-11th Century) present images of weapons which are likely war flails, (D’Amato, 2011) some of which include the spiked ball varieties. This is backed up by significant archaeological evidence (flail head finds) from the former territories of that state, especially in the Balkans. (Culic, 2016, Rabovyanov, 2016) The well-characterised cultural contact between the Norse, Rus, and even English with Byzantium, in the form of the Varangian Guard and similar mercenary formations within the Byzantine Empire also resulted in foreign technologies being brought into the Empire and retained for centuries. (Katona, 2017) The prevalent interactions between the Byzantines and the Western and Southern European powers during the 11th, 12th, and 13th Centuries mean that a degree of technological and cultural awareness of each other’s capabilities and habits must have formed during this period, especially given the habits of certain peoples (Normans) to serve as mercenaries across much of the Mediterranean.

As discussed above, the Byzantines may have adopted flails from the Khazars, who served as mercenaries in the Imperial guard for centuries, or adopted from their Bulgar opponents in the 10th and 11th Centuries. (Grotowsky, 2010) These flails are occasionally confused with scourges in illustrations but have been described in use as (horseback) battlefield weapons – consisting of a wooden handle to which small (5 cm or less) bronze or antler, stone or bone balls were attached by leather or hemp rope. A great many depictions of such weapons appear in the Madrid Skylitzes, (D’Amato, 2005; D’Amati, 2011; Rabovyanov, 2021) though from the low quality of the images available, these could represent either flails or maces, though they are rather long to be the latter. See the 2011 work of D’Amato for a comprehensive selection of these and here for the full manuscript. Finds from the 11th Century around Romania verify such descriptions. (Culic, 2016) A Norman mercenary captain is described as being used to beaten (humiliated) by a Byzantine officer with a flail in several sources from both sides. (D’Amato, 2005)

(XVII) The c. 1170

chanson de geste entitled

La Bataille Loquifier (the Battle of Loquifier, adapted from MS de l’Arsenal 6562), which is part of the Cycle of Guillaume d’Orange, includes several references to the

plomée (flail) (Runeburg, 1913):

|

“S'i a fausars et quarriaus empené

Et pic et mache et coutiel afilé,

Et dars molus avoit a grant plenté.

III. grans plomees a deriere endossé,

Puis prist se loke, e le vous adoubé.

I. longement ot el chief saielé,

Ja tant n'aroit tout le cors desmembré.”

“Li Sarr. Avoit a sen costé

Les .III. espees don’t I je vous ai conté.

Se grant plomee’a d'encoste torsé

Et sen picois de brun achier tempré

Miséricorde a çaint a sen costé;

En sen dos furent si .m. hauberc saffre.”

“Quant .R. vit celui escapé

Hors de le tiere, molt en est aïré.

A se plomee avoit se main jeté

Que bien pesoit .i. grant caisne ramé:

IV diauble sont o lui empené.”

|

(XVIII) One of the more interesting medieval manuscripts depicting war flails is the Psalter Kupferstichkabinett 78 A 5 (

Figure 21), believed to originate from northern Italy c. 1175, though now located in Berlin. (Peterson, 1987; Augustyn, 1989) This piece depicts war flails in no less three separate folios (fols. 10r, 45v, and 52r) one in the hands of a maille-armoured and shielded figure, and two in the hands of unarmoured figures. All three are depicted with spiked heads attached to the haft via a chain, though the proportions between the haft and chain are slightly variable across the depictions. Two of the depictions illustrate the haft with a spiral pattern running up it (in a similar manner to some warclub depictions in the Maciejowski bible), while the third is plainer in design. These folios depict various biblical scenes with a common thread of the old testament King David, who himself is not noted to be wielding the flail in any of the scenes.

(XIX and XX) War flails are not restricted to textual, drawn, or carved depictions; several archaeological finds of flail heads have been discovered such as the copper-alloy flail head found in Flintshire, Wales, UK (Veninger, 2015; Link,

Figure 22). This has been dated between 900 and 1400, though the style matches earlier Slavic flail heads widely known in Eastern Europe to originate from the 12

th Century. A similar flail head was recovered from a dig site in Mainz in the 1990s (

Figure 23), believed to correspond to an early 13

th Century pattern. (Taavistainen, 2004; Wamers, 1994) The majority of flail heads are of the order 50-80 grams if of organic origin (bone/antler) (Michalak and Zamelska-Monczak, 2016) and of a few hundred grams in weight if metal (iron, lead, brass) – much heavier and such a weapon would be too slow and unwieldy to be a viable battlefield weapon. (Zdaniewicz and Adamiak, 2011)

One of Sturtevant’s arguments against flails being used at all, was the prevalence of reproduction pieces passed off as genuine period artefacts; (Sturtevant, 2016a, 2016b, 2017) while completely disregarding the widespread number of finds from Eastern Europe and similar artefacts which have surfaced in the Central, Western, and Northern reaches of the continent. (Taavistainen, 2004; Terävä, 2014) The level of decay observed on physical finds is dependent on the material of production and the inclement conditions in which they were found. (Drob and Vasilache, 2022) A selection of possibly misidentified archaeological finds is presented in the appendix.

A number of archaeological finds of “mace heads” may actually be flail heads due to the small diameter holes being insufficient for a rigid wooden haft of appropriate thickness to maintain the necessary strength of the weapon when administering blows to the foe, (Michalak, 2019; Farcas, 2016, Imiolczyk and Zdaniewicz, 2022; Kotowicz, 2008; Zdaniewicz and Adamiak, 2011; Tihle, 2017; Michalak, 2006) despite similarities in the patterns of mace and flail heads observed. (Skhorokhod and Blazhchek, 2020; Daubney, 2007; Michalak, 2006) One particular example is Fig. 4.2 in the 2019 work of Michalak, (Michalak, 2019) in this case, the head was likely attached to a wooden handle via a piece of rope or suitably thick, or possibly plaited/braided leather thonging knotted above and below the head, (Zhirohov and Nicolle, 2019; Michalak and Wolanin, 2008) either of which would usually have rotted away with centuries in the ground and as such are not commonly observed when such items are dug up; (Moreno, 2015) were a rigid iron shaft also present (as a mace), the remains of this would have been recovered alongside the head, (Michalak, 2019) and indeed wooden hafts are observed in several cases where ground conditions were favourable to preservation. (Tihle, 2017) A wooden haft or handle may or may not have been present on flails, (Kotwicz, 2006) with the chord simply wrapped around the hand for use. (Shpakovsky and Nicolle, 2013; Kotowicz, 2006) More examples are presented in the work of D’Amato, (D’Amato, 2011) though he considers these to be maces rather than flails, despite comments to the contrary in earlier works. (D’Amato, 2005)

A similar degree of confuson may arise between those unfamiliar with the common patterns of flail heads may arise for a range of artefacts of similar design labelled as “weights”. These can include the medieval “standard” weights or “steelyard weights” which bear a striking resemblance to flail head, e.g.

Figure 24.

The most likely distinguising factor between these two types of item is the overall size and weight – flails heads tend to mass ~300 g at a maximum, with definite steelyard weights massing more than 600 g, and being correspondingly larger, though a large number identified as such are significantly lighter and could thus function effectively as flail heads. The perishability of organic materials used as the flexible component of flails mean that it would be very easy for a flail to be misidentified as a flail in this manner. An example of a lead-filled, brass-shell steelyard weight is presented below. Several more possible flail heads identified as weights similar to this, though in the typical weight range of flail heads are presented in the appendix

(XXI) An 1174 English seal from the reign of Henry II depicting the legendary Gnostic figure Abrasax (Abraxas) wielding a flail and shield was used to countersign a charter of Louis VII of France. This is the only known utilisation of this particular seal. (Vincent, 2015)

(XXII) The

Chanson d’Antioche (Song of Antioch, c. 1180) provides a similar description of the Tafurs (chant VIII, v.87, with modern French added for context, and English translation of the relevant parts), describing the use of “plomées” (leaden/leaded flails), and scythes – improvised weapons of the impoverished. (Funck-Brentano, 1922):

|

“Il ne portent o [avec] els ne lance ne espée,

Mais gisarme esmolne et machu-e plomée,

Li rois porte une faus qui moult bien est temprée

N’a paien si armé en tote la contrée

K’il nel porfende tot desci qu’en la corée

Moult tient bien de sa gent la compaigne serrée,

S’ont lor sas à lor cols à cordele torsée,

Si ont les contés nus et les pances pelées,

Les mustiax ont rostis et les plantes crevées

Par lailquel terre qu’il voisent moult gastent la contrée.”

“They do not wield lance or sword

But gisarme (farming tool)... and flail (plomée)

The King (of the Tafurs) carries a scythe which is well-soaked...”

|

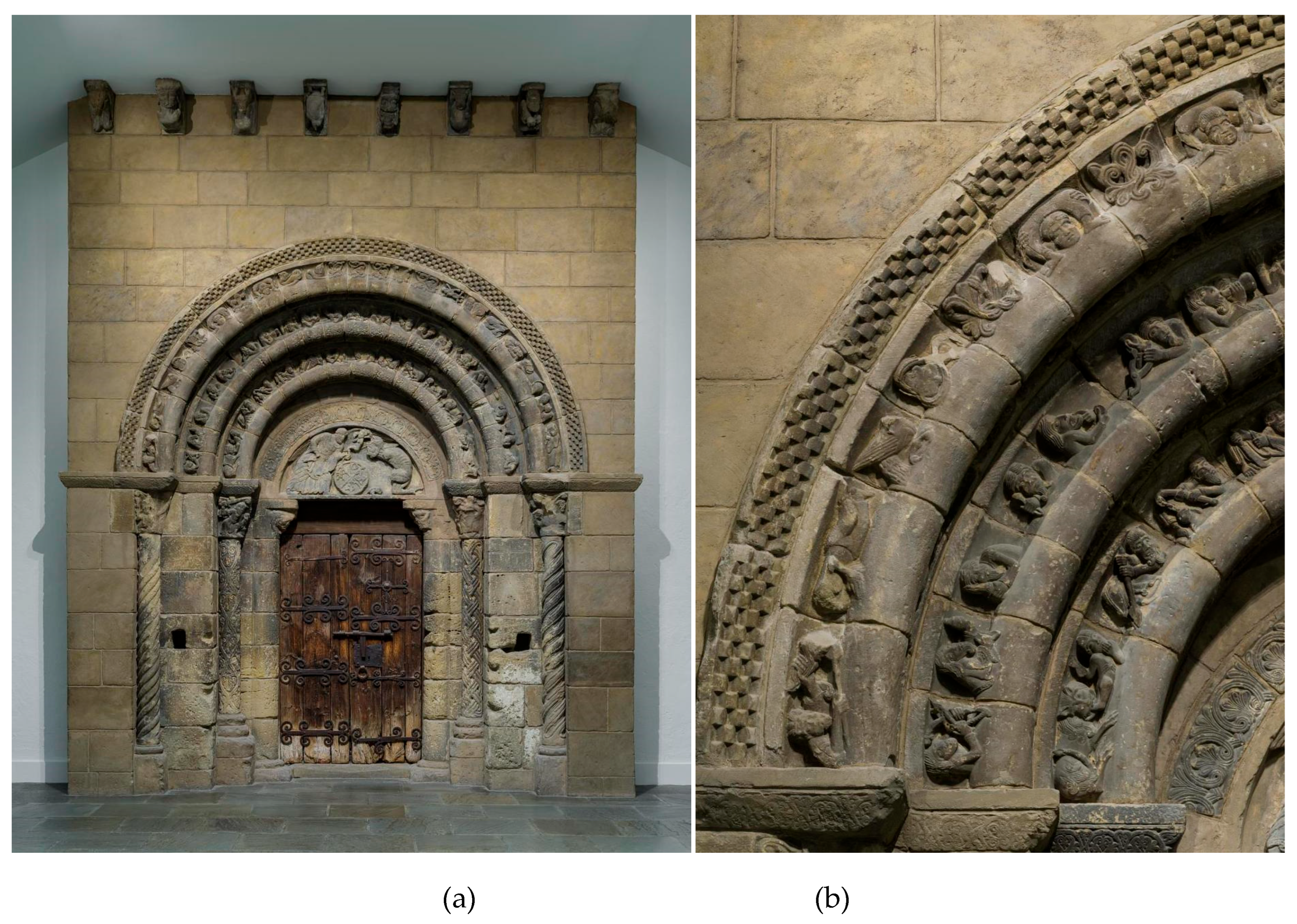

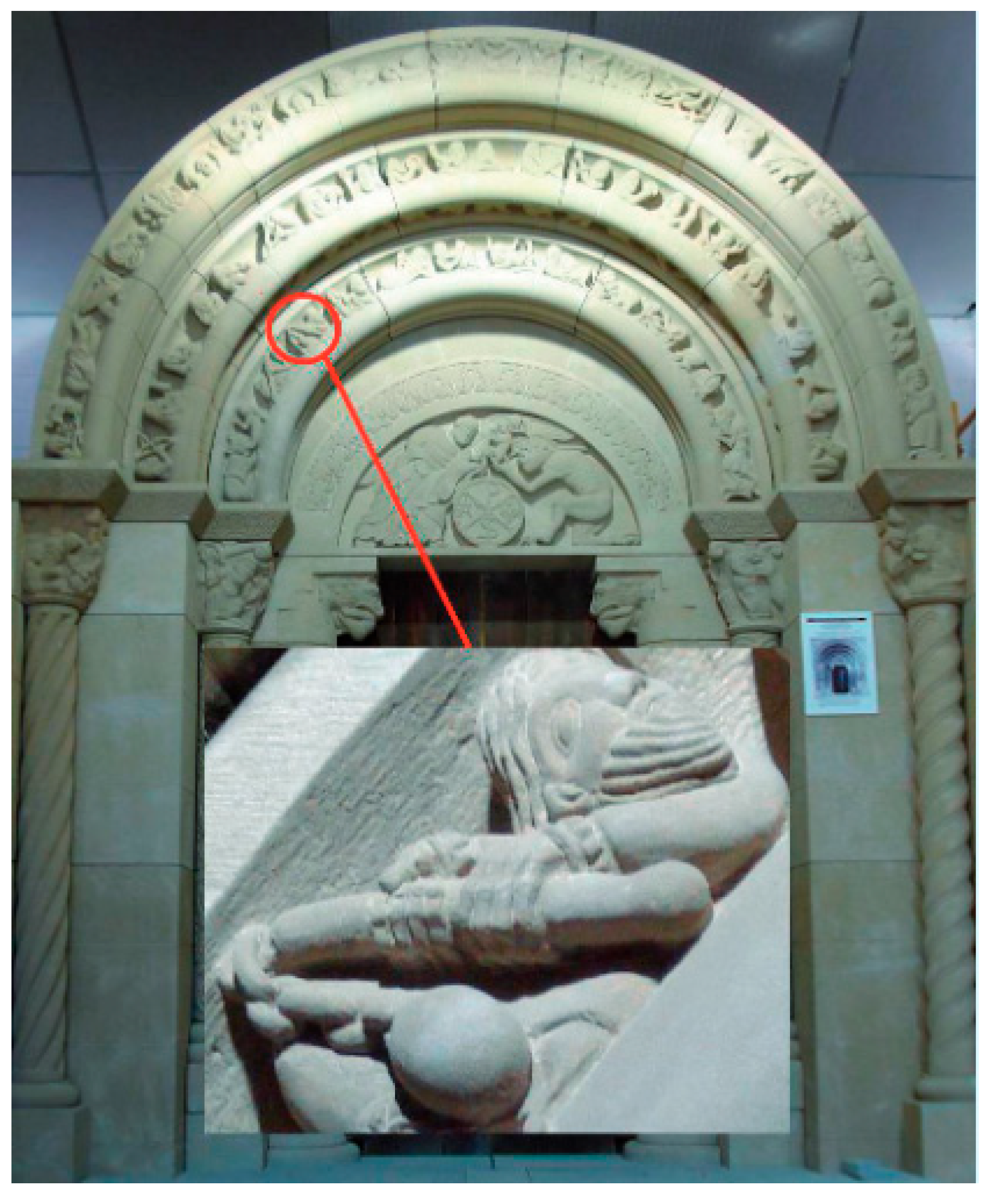

(XXIII) In the last quarter of the 12

th Century, depictions of war flails appear in Aragon, Northeastern Spain, for example in the archway of one of the many churches in the town of San Miguel de Uncastillo. (Perratore, 2015) The images depicted below (Nicolle, 1999; Manning, 2016) show a two-handed ball and chain type flail with a spherical ball and short chain (1/3 the length of the haft), though no further context of use is given. The original arch is present at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA, from which a selection of the below images (

Figure 25 is taken, although a faithful copy of the archway is has been reproduced (as per

Figure 26, Link).

(XXIV) The Old French poem Lancelot, le Chevalier de la Charrette, written by Chretien de Troyes c. 1180, is an Arthurian tale with Lancelot as a prominent character. In this story, a giant character arms himself with a mace de fer plomée (flail-mace of iron) and goes on a rampage. (Huet, 1912)

(XXV) The Celtic Irish tale Togail Bruidne Dá Derga (The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel), belonging to the Ulster Cycle of that country’s mythology dates from the 12th Century in the earliest recorded manuscripts, but the oral tradition is likely much older (Link). (Sayers, 1983) In the tale, three Manx giants (Vikings or Norse?) are described as being armed with iron flails (susta iarnae) comprising clubs with ball and chain. (Sayers, 1983, Brown, 1919)

“A blow, they give with three iron flails having seven chains triple-twisted, three-edged, with seven iron knobs at the end of every chain: each of them as heavy as an ingot of ten smeltings. Three big brown men. Dark equine backmanes on them, which reach their heels...

... Three hundred will fall by them in their first encounter, and they will surpass in prowess every three in the Hostel; and if they come forth upon you, the fragments of you will be fit to go through the sieve of a corn-kiln, from the way in which they will destroy you with the flails of iron. Woe to him that shall wreak the Destruction, though it were only on account of those three! For to combat against ‘them is not a 'paean round a sluggard.”

(XXVI) The late 12

th Century French chanson

La Mort Aymeri de Narbonne (Link, Link, Lines 2680-2690) features a reference to a

plomée being used by a Christian to attack a Saracen (Moorish) camp, likely corresponding to the time of Charlemagne as many of the contemporary pieces are. (du Parc, 1884)

|

“D’une plomée va crestiens tuant,

Ça .ii., ça .iii. les ala craventant.

Et il s’escrient : « Aïde, Guiberz frans.

« Sainte Marie ! ja serons recreant. »

Guiberz l’oï, cele part vint corant,

Et li paiens s’adrece vers l’enfant ;

De sa plomée va la verje hauçant

Que la mace ert par terre traïnant,

Va la corroie larjement estendant”

“From a plomée (flail) goes Crestiens killing

First two thenIee, craving...

...from his plomée goes the heightening [strike?]

As the mace (head) drags along the ground.”

|

(XXVII) The c. 1185 epic poem

Aliscans, originally written in the Picard language of northern France (Link and Link), contains several references to war flails, referred to as both morgensterns and kriegsflegels in a modern German translation of the text. (Knapp, 2013) Borel, a character from the poem, is described as causing great slaughter with a war flail even against armoured foes, while another character, Margot, is described as using a morning star, (Buridant, 2003; Hamilton, 1911) and with it killing two men with a single blow. The title of the poem is possibly a reference to the Roman settlement of Alsycamps, which continued in use until the early middle ages, and the story is likely a fictionalised retelling the story leading up to the expulsion of the “Saracens” (likely Moorish, as the term Saracen was used to refer to Arabs generally (Daniel, 1979)) from southern France around the end of the 10

th Century. The “Saracens” in particular are noted as using a range of unusual arms including flails, a hammer, and a scythe, (Schulz, 1889) though these kinds of descriptors are not unique to

Aliscans: many of the other

chansons portray the “Saracens” with different weapons, likely as a means to emphasise their “otherness”. (Lofmark, 1972; Hamilton, 1911) The story is believed to be based upon the earlier

Chançun de Willame, and inspired the later

Willehalm, composed by the German knight Wolfram von Eschenbach. (Gibbs and Johnson, 1997) The latter of these also cites the use of war flails (kriegsflegels). The effectiveness of flails against maille-armoured opponents is discussed later, but this is recognised in

Aliscans, thus likely reflecting period knowledge of the use of these weapons in a combat or battlefield setting. Flails are described around lines 5719, 5739 (where the Count Guillaume d’Orange flees a flail-wielding opponent, possibly a pagan), and 5990 (Sternberg, 1886):

|

“Un flaiel porte, la mace ert d’orpuement

Et tout li mances en estoit ensement

Et la chaine don’t la batier pent

Plain poig ert grosse, close estoit fierement

Ki ert molt dure, d’une pel de serpent

Ki ne crient arme d’acier ne ferrement.”

“N’i a celui ne portast I flael

Toz sont de coivre, bien over a cisel.”

|

(XXVIII) A flail is described in the c. 1200 German poem

Nibelungenlied or

The Song of the Nibelungs which is believed to originate from Passau in the south of the modern-day Germany. (Jähns, 1899; Whobrey, 2018; Shpakovsky and Nicolle, 2013) The duel between the character Alberich (Albrich) and a “dwarf king” is described as follows (from a modern-day translation (Link)):

|

“Alberich was full wrathy, / thereto a man of power.

Coat of mail and helmet / he on his body wore,

And in his hand a heavy / scourge of gold he swung.

Where was fighting Siegfried, / thither in mickle haste he sprung.

Seven knobs thick and heavy / on the club's end were seen,

Wherewith the shield that guarded / the knight that was so keen

He battered with such vigor / that pieces from it brake.

Lest he his life should forfeit / the noble stranger gan to quake.”

|

The weapon described here is referred to as a giessel (whip) in the original text, though this seemingly describes a war flail, though a bit of artistic license on the part of the authors is likely here, unless the reference to gold is instead describing copper alloy in the form of brass or bronze which can appear golden. Most of the period depictions of war flails picture these with single heads, rather than the seven attested to in the poem, with multi-headed flails only appearing later (post 1250), barring a few exceptions previously highlighted.. Shpakovsky and Nicolle postulate that the Germans viewed this as an alien weapon of some rarity in their locale, but nonetheless an awareness of the technology is demonstrated. (Shpakovsky and Nicolle, 2013) A late 13th-Century surviving versions of this work are extant and can be found here.

(XXIX) The c. 1200 French chanson

Jourdain de Blaivies, which tells a tale of revenge in the time of Charlemagne, describes the use of a war flail (

plomée) (Schulz, 1889; Sternberg, 1886):

|

“Li uns pleut hache et li autres espec

Li tiers sa mace et li quars sa plommée.”

|

(XXX) A 1202 inventory of weapons prepared after the capture of Robbio Castle (northern Italy) included, amongst other things, falciones (falchions/fauchards) and plumbatas (Kriegsflegels - war flails), though no further description than this is provided, and the original source (Angelucci Documenti) is unavailable. (Köhler, 1887)

(XXXI) The French epic poem Huon of Boreaux (c. first half of the 13th Century) describes a confrontation between the titular character and a pair of “men of brass, each of whom held in his hand an iron flail... beat with their flails without ceasing for a single moment”. These “brass men” are guarding a tower in which a damsel named Sybil is imprisoned by the giant Angolafer (perhaps the origin of so many “princess in the tower” stories). Huon triumphs over the brass men and slays the giant. (Church, 1904; Tuve, 1929) The legend itself is believed to originate from the time of Charlemagne.

(XXXII) Thorbeck’s interpretation of the events of the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212), where the power of the Moors during the Reconquista was broken, sealing their ultimate demise several centuries later, describes the use of a “látigo de guerra” (lit. war whip cf. Schlachtgeissel) by the Navarrese king Sanco the Strong, perhaps based on the account of the troubadour Guillermo de Aneliers. (Thorbeck, 1999; Moreno, 2015; Arnedo, 2010) The flail used or a similar example thereof was supposedly interred within the Abbey of Roncesvalles, (Thorbeck, 1999; Moreno, 2015; Arnedo, 2010) though items found are also attributed to the flails of Roland and Olivier, (Demmin, 1911) but these may be later reproductions or forgeries designed to act as “holy relics”, as these were first mentioned in a note from 1617. (Dona, 2021) The original Thorbeck reference is unavailable, however, and as such the sources he used cannot be analysed in any further detail. The remains of a flail were purportedly found upon the field of Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (Abad, 2013; Moreno, 2015), though again, this text is not available and so cannot be discussed further.

(XXXIII) The

Vercelli Mappamundi (Vercelli map of the world, c. 1217, held in the Archivio Capitolare of Vercelli), (Mittman, 2019) believed to be either an early or later 13

th Century stylised map of the world depicts a figure carrying a multi-headed flail (more likely than a scourge,

Figure 27). The accompanying text describes this crowned figure, who is riding a stylised giant bird bearing a horseshoe (described in one reference as “the iron-eating ostrich”) in its beak as “King Philip of France”, which could refer to Philip II (1165-1223) or Philip III (1245-1285). (Unknown; Davies, 2020; Lewy, 2021) Although otherwise heavily damaged, this portion of the map is still legible.

(XXXIV) A series of paintings from Iglesia de la Asunción, Alaiza, Spain depict several figures (perhaps demons?) armed with ball-and-chain type flails (

Figure 28). The church itself is dated from the early 13

th Century, though the style of the artwork (dress worn by the figures therein) more reflects late 12

th Century styles.

(XXXV) The Roman treatise De Re Militari, originally written in Latin was translated into French and Norman French during the early and mid-13th Century respectively (as the Fitzwilliam Vegetius), (Carley, 1962; Moreno, 2015) and includes many references to the use of flails in a military setting. The original Latin text was adapted during the translation process to account for period terms. (Carley, 1962; Moreno, 2015) Due to the number of references to the flail (as plomez or plommez), I will refer readers to the thesis of Carley, (Carley, 1962) for further discussion.

(XXXVI) The 13

th Century French chanson

Doon de Mayence further mentions the use of the plomée (flail), M 10624 (Sternberg, 1886):

|

“Dont li veissies pierres et pessemens ruer Et de lanches ferir et d espees capler

De maches de plommees merveilleus cous donner”

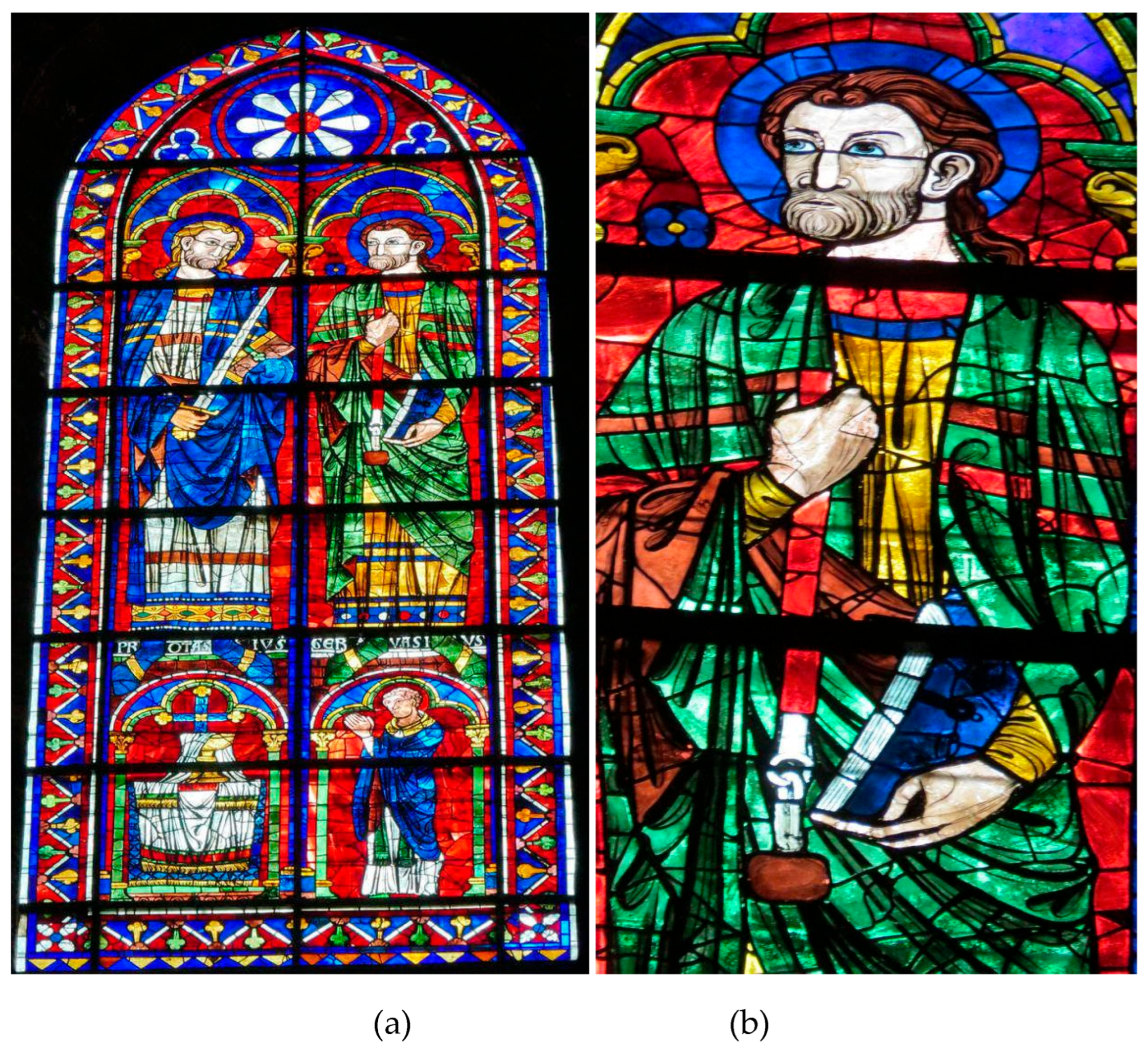

|

(XXXVII) The stained-glass windows of Chatres Cathedral (France, constructed around 1160), most of which are believed to date from the first half the 13

th Century; bay 100 (c. 1230-1250) depicts the 2

nd Century martyrs Saints Gervais (Gervasius) and Proteus (Protasius), (Kolar, 2020) who is carrying a book in his left hand and an inverted ball and chain flail in his right, the haft held to his chest (

Figure 29). This bay appears adjacent to the bay (99) depicting Saints Damien and Cosmos. (Link) The flail represented is depicted with a long red haft, perhaps intended to represent wood, with silvery fittings (iron) connecting a brown (copper alloy) head via a short chain. This represents one of the clearest representations of the fittings of a flail to its haft which, period artistic license notwithstanding, would suggest a conical socket containing a ring of iron, to which the chain of the flail is attached. This type of construction was well within the capabilities of smiths in the 13

th Century and indeed earlier. The flail may also be an unusual depiction of a threshing flail (given the shortness of the item), as the saints depicted are the patrons of haymakers. (Kolar, 2020)

(XXXVIII) The c. mid-13

th Century French or English manuscript

Bible Moralisée (dated 1226-1275), currently held in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford (MS. Bodl. 270 b,

Figure 30) contains a great many folios depicting demons tormenting people with an assortment of odd weapons, including a ball-and-chain flail (fol. 156r). In this image, a pink-hued demon (distinguished by horns, pointed ears, and a tail) wields a war flail two-handed, reinforcing the common iconography of flails being weapons wielded by the evil. The haft is depicted in brown (wooden) and the chain and (possibly spiked) ball in grey, suggesting construction in iron. The construction of this flail is one of the clearer examples presented and mirrors the design of the one presented above in several respects.

Later Sources

The number of visual depictions of war flails increases over the course of the 13th Century and onwards, with evolutions in style and use as will be discussed in due course, as the adaption of threshing flails into a weaponised form during the 14th Century was presented above. From c. 1250, war flails are depicted more commonly in use by heavily-armoured, mounted warriors rather than unarmoured or more-lightly armoured dismounted figures in earlier artwork. As such, a selection of pertinent examples from after 1250 is presented, rather than all known sources. A similar transition further takes place from this point in time whereby the previously numerous depictions of flails being wielded by “evil” persons (heathens, mobs, heretics) and creatures (demons) is surpassed by knightly or chivalric examples.

(XXXIX) One exception to this observation is fol. 179 from the Radziwill Chronicle (MS 34.5.30, currently held in the Research Department of Manuscrupts, Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation,

Figure 31), depicting the murder of Prince Ihor (Igor) by the Kyivans during the 1147 uprising. (Taavistainen, 2004)

The manuscript itself is dated from the 15th Century, but believed to be a copy of an earlier 13th Century manuscript. A short war flail is depicted being wielded by the figure in red – a wooden haft with a blued head. (Osypenko, 2020; Sturtevant, 2017) This is likely more representative of the flails used in Eastern Europe rather than those found more westwards where multi-headed designs become more prevalent after this point in time.

(XL) One of the earliest depictions of war flails being used by mounted warriors in Western Europe is a folio (210v) from the History of Outremer (BNF Français 2630, France,

Figure 32), dated c. 1250. A single or possibly multi-headed iron flail with a wooden haft is depicted being used by a mounted warrior in the top left of the image. Given the usual “lag” in the visual reporting of items being depicted in comparison to their actual use, this serves as confirmation that war flails were indeed in use in Western Europe at least as early as 1250, and very likely before this.

(XLI) The count of Holland and Zeeland, William II (1227-1256) was reportedly killed by a blow to the head from a flail (type unspecified – referred to in the Dutch text as a Strijdvlegel) after his horse fell through ice on a frozen lake during the Battle of Hoogwoud (modern-day Netherlands) against the Frisians. His body was buried under a house but recovered by his son and then reburied in the Abbey of Middelburg (Netherlands). (Burgers, 1998)

(XLII) An inventory of the armoury of Sesa Castle (Huesca, Aragon, Spain) from 1274 describes the inclusion of “3 iron maces with their chains”, (listed as iii macas de fierro con sus cadenzas). As the Spanish word “maca” is the standard description for a ball-headed mace, this entry likely refers to flails rather than other possibilities.

(XLIII) A circular boxwood artefact (c. 4 cm in diameter,

Figure 33) believed to be a draughts or backgammon piece originating from England depicts an armoured solider attacking what appears to be a giant, helmeted mollusc with a war flail. The timeframe of this piece can be narrowed by the ailettes present on the shoulders of the figure – items of armour which only came into brief use in the latter half of the 13

th Century and were replaced not long after the turn of the 14

th Century by dedicated shoulder cops and later pauldrons as metallurgy improved over time. The flail being wielded appears to be a ball-and-chain type. This item is held in the collection of British Museum.

(XLIV) A folio from Moniage de Guillaume (France), dated c. late 13th Century depicts two dismounted, maille-armoured warriors, one armed with a three-headed war flail, and the other with a giant two-handed war club and a sword belted at his waist. This image may have connections to the symbology of the 12th-Century Waldensian movement of France, whose leader is co-notated with a spiked flail, (Gerhardt, 2007) or perhaps represent Guillaume and Rainouart from the Cycle of Guillaume, discussed previously. The folio can be found here.

(XLV) A series of frescoes from a late 13th-early 14th Century Italian church (now destroyed) depict the story of La Chanson d’Otinel, a late 12th Century Norman or French tale about a Saracen (likely Moorish) knight from the time of Charlemagne who converts to Christianity. The titular character is depicted fighting on foot wielding “a flail or with three chains ending in lead spheres”, in contrast to the typical text of the story, where he fights mounted with a sword. (Gerhardinger, 2020) As Roland and Olivier (from the Song of Roland are somewhat intertwined in this story, (Fein and Rabin, 2019) the character depicted in these frescoes may be Olivier, as per the fresco from the Cathedral of Verona.

(XLVI) The c. 1277 French treatise De Regimine Principum, written by Giles of Rome, serving as Archbishop of Bourges (c. 1243-1316), for King Philip the Fair of France provides instruction on the correct governance of a kingdom in several sections including warfare, and was translated into several contemporary languages. The flail is explicitly mentioned (with reference to ball and chain) in both the French and Latin versions as plomée and plumbatis respectively. (Scala, 2021) To paraphrase both approximate translations: “For a ball of lead or iron, when some chain is attached to the wooden handle it gives a strong blow. For the sake of a ball with a chain attached to the spear strikes the air more violently than if they were themselves the spear itself would be attached to a wooden handle”.

(XLVII) Folio 282v from Arthurian Romances (Beinecke MS.229, France,

Figure 34), dated c. last quarter of the 13

th Century, depicts a maille-armoured figure wielding a three-headed flail (less likely a scourge, given a single head per strand). Somewhat amusingly, he is riding (or possibly choking) a giant chicken, (Shardtrand, 2020) suggesting a degree of artistic license is being taken here. The artist likely intended to convey a wooden-handled flail with iron heads. Whether these are connected to the haft via chains or another method cannot be determined. This may be a reference to King Philip the Fair of France (c. 1285-1314) or Guy of Dampierre. (Shardtrand, 2020)

(XLVIII) The French poet Guillaume Guiart (d. 1316) wrote of the use of flails (as plomées) in

Branche des Royaux Lignanges, covering the Franco Flemish war (1297-1305), where he was injured in 1304. The references are as follows (Schulz, 1889), lines 1469 and 6948:

|

“La véissiez enteser maces

Et plomées pour faire plaies.”

“La ot tant bastons et plomées.”

|

(XLIX) A folio from (131v-2) from the early 14

th Century French manuscript

Vita et Passio Beati Dionysii (BNF Latin MS 5286,

Figure 35) depicts a large battle scene where one of the soldiers (centre top) is wilding a ball and chain type war flail. This appears as a two-handed weapon where the chain or chord is about half the length of the haft. As the image is black and white and the wielding character is in the background, however, further information cannot be garnered.

(L) The c. 1310-1340 Franco-Italian manuscript

Libreria Marciana Fr. Z 21 –

Entrée d’Espagne contains no fewer than thirteen folios (fols. 17v, 22v, 23r, 23v, 24r, 27r, 32v, 33v, 36r, 43v, 44r, 44v, and 47v) of a mounted (possibly Saracen) knight (described as Farragu, or Farragut) wielding a three-headed ball-and-chain flail which in some of the folios is also presented with an additional spherical “head” at the top of the haft. The folios seem to have been illustrated by at least two different artists given the variance in design between the first (17r-27r,

Figure 36) and second (32v to 47v,

Figure 37) sets of similar folios from the manuscript. These two groups of folios are presented below, with a description (describing the flail as a “3-stringed mace”) available from Link.

The (Saracen) knight (paladin) depicted with the flail (Farragut) is one of the characters within several texts of the Matter of France and some Spanish texts dating back to the mid-12th Century at the latest, in addition to appearing in some Italian epics. He is sometimes depicted or referred to as a giant, and was eventually killed by the aforementioned Roland, who is also described in the manuscript from which these folios are drawn, alongside Charlemagne. Many of the other depictions of Farragut show him armed with more conventional knightly weapons (lance, sword), rather than the flail, but this is consistent in Fr. Z 21. The flail depicted is undoubtedly effective in the story as several of Farragut’s opponents are unhorsed by him fols. 22v and 27r.

(LI) An “Arming Treatise” entitled the

Manner of Arming Knights for the Tourney (f.86v and 87 from BL Additional MS 46919) believed to have been compiled by Fr William Herebert of Hereford (d. 1333 or 1337) in the early 14

th Century describes flails in the equipment of knights during tournaments. (Moffat, 2010) The type of flail mentioned here is not specified, but this suggests that flails were at least used in tournament settings. Note the use of the Latin-derived term “flagellu”, rather than the modern French “fléau”, which posed challenges in translating this piece. (Moffat, 2010)

|

“ayne payns ou gayns de baleyne sa espeye i. gladi’ & flagellű & galeam i. heaume.”

“gaignepains or gauntlets of baleen, his espeye that is sword, and flail, and helm that is heaume.”

|

(LII) A small, single-headed ball-and-chain flail is depicted in a folio (049r,

Figure 38) from the c. 1330-1340 illuminated French manuscript Avignon BM MS.121

Psalter-Hours in the hands of a maille-clad dark-skinned warrior who also bears a small round shield, perhaps a buckler. A number of similarly armoured figures wielding an assortment of polearms and a lantern are present in the background, perhaps mirroring the mob arresting Jesus from the 12