1. Introduction

Stiffness is the most common complication adversely affecting shoulder function postoperatively and is a crucial factor in shoulder pathology and associated conditions [

1]. Arthroscopic capsular release (ACR) is a key procedure for shoulder joint stiffness accompanied by rotator cuff tears or adhesive capsulitis that fails to respond to conservative treatment [

2]. Among other treatment options, ACR is clinically favored because it poses a low risk of fracture and allows simultaneous identification and treatment of intra-articular lesions [

2]. The improvement in range-of-motion (ROM) and pain score achieved with ACR leads to patient satisfaction [

1,

2].

While ACR provides excellent improvements in shoulder function, postoperative complications, such as iatrogenic axillary nerve injury or joint stiffness recurrence have been reported [

2,

3]. Blood supply to the humeral head is sustained through the intraosseous circulation facilitated by the anterior and posterior humeral circumflex arteries [

4]. Disruption of these pathways leads to osteonecrosis. Trauma and corticosteroid use commonly cause osteonecrosis of the humeral head of traumatic and atraumatic origins, respectively. Factors such as chronic alcohol consumption, systemic lupus erythematosus, coagulopathy, viral infection, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy induce osteonecrosis [

5]. Several case reports or series have presented postoperative progression of osteonecrosis of the humeral head during other arthroscopic procedures in the shoulder joint [

6]. For instance, recent case reports have described the development of osteonecrosis after arthroscopic rotator cuff surgery using anchors and surgical procedures for lesions in the biceps long-head tendon [

5,

7,

8,

9]. However, no case of osteonecrosis of the humeral head has been reported after ACR.

Here, we report a clinical case of post-ACR osteonecrosis of the humeral head, which was followed up for 3 years.

2. Case report

A 56-year-old male patient complained severe ROM limitations and pain in the right shoulder joint that did not improve. He had a history of dislocation of the right acromioclavicular joint due to a fall 9 months previously, had undergone open reduction and internal fixation of the joint using a hook plate at another hospital, followed by hardware removal 4 months after the initial surgery. Six months after the removal of the hook plate, he had no improvement in the persistent stiffness or pain in the shoulder, despite appropriate rehabilitation protocols, including medication and physiotherapy. The patient had a history of consuming 40 g of alcohol ≥ 5 times per week for 25 years, but had no history of smoking. He was regularly monitored for chronic hepatitis B and was taking medications for primary hypertension.

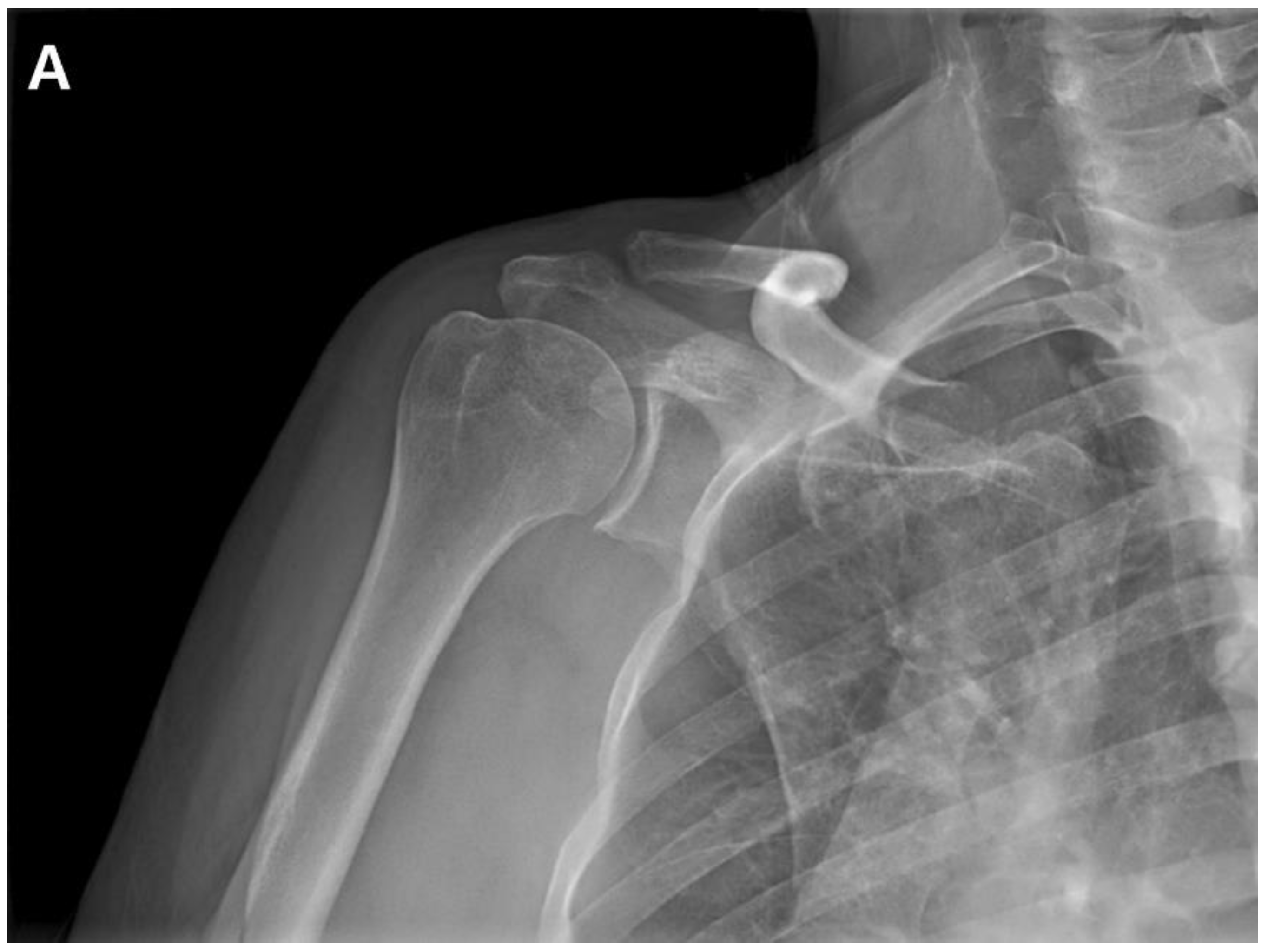

A postoperative scar was observed on the superior aspect along the distal clavicle and acromion, without definite tenderness, swelling, or redness. Preoperatively, the ROM of the affected shoulder was 90° for active forward flexion, 90° for abduction, 40° for external rotation, and sacral level for internal rotation. The visual analog scale (VAS) score was 4, the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score was 51, and the Constant-Murley Score (CMS) was 48. Preoperative shoulder radiographs showed acceptable alignment and joint congruency, with no bony spurs or subchondral lesions. Anteroposterior and axillary views of the shoulder radiograph showed acceptable status of acromioclavicular joint reduction without arthritic changes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed incomplete signal changes in the supraspinatus muscle, with preserved structural integrity (Fig. 1). Given the patient’s persistent symptoms, which did not improve, the patient had opted for ACR, with informed consent.

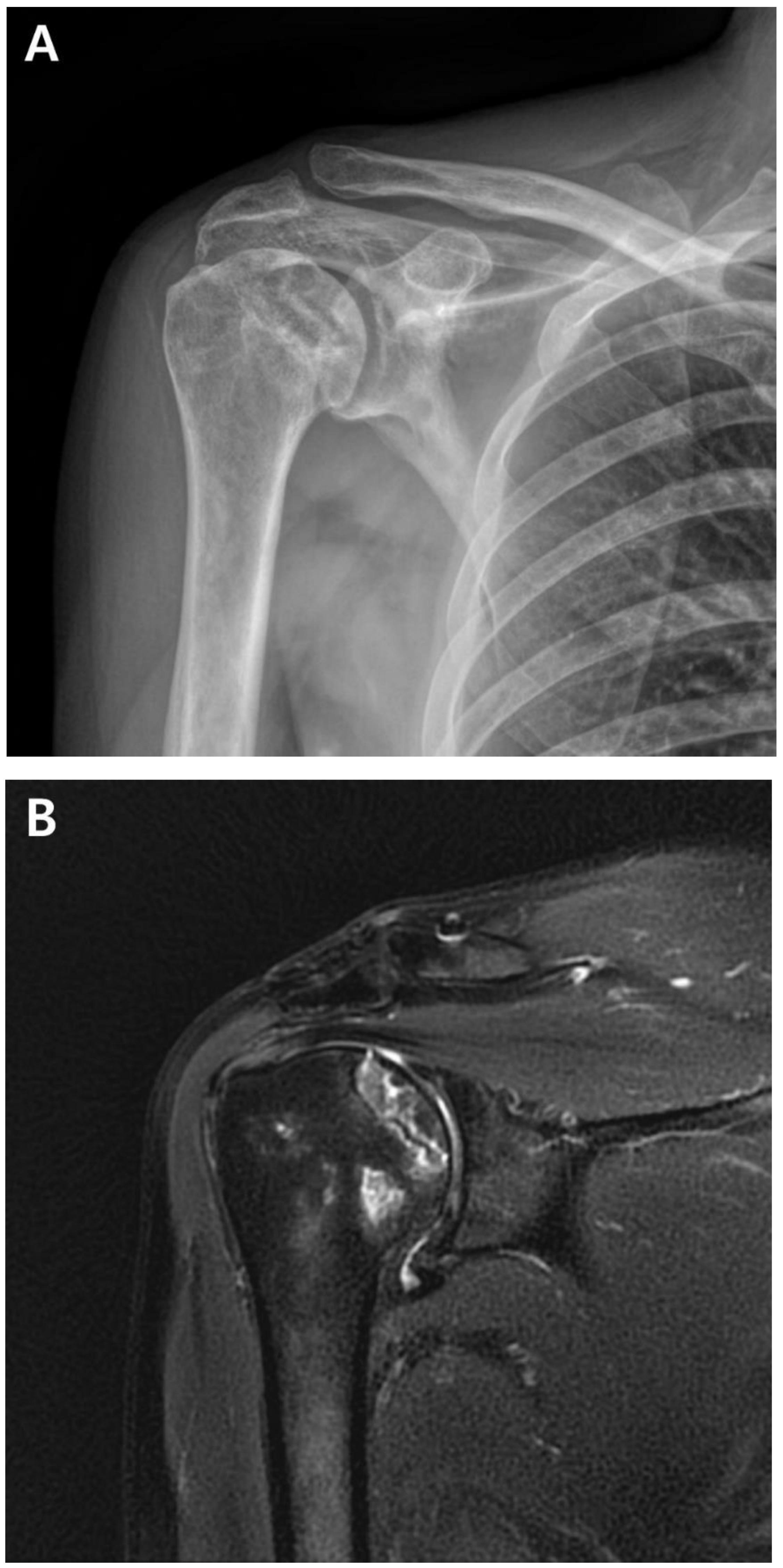

Figure 1.

A. Preoperative plain anteroposterior radiograph. Acromioclavicular joint alignment was acceptable with no arthritic changes. The glenohumeral joint showed adequate joint space and congruency. B. Oblique coronal T2 fat-suppressed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI of the right shoulder showed a thickened axillary pouch with normal hypointense joint capsule. The supraspinatus tendon had high signal variation with intact continuity.

Figure 1.

A. Preoperative plain anteroposterior radiograph. Acromioclavicular joint alignment was acceptable with no arthritic changes. The glenohumeral joint showed adequate joint space and congruency. B. Oblique coronal T2 fat-suppressed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI of the right shoulder showed a thickened axillary pouch with normal hypointense joint capsule. The supraspinatus tendon had high signal variation with intact continuity.

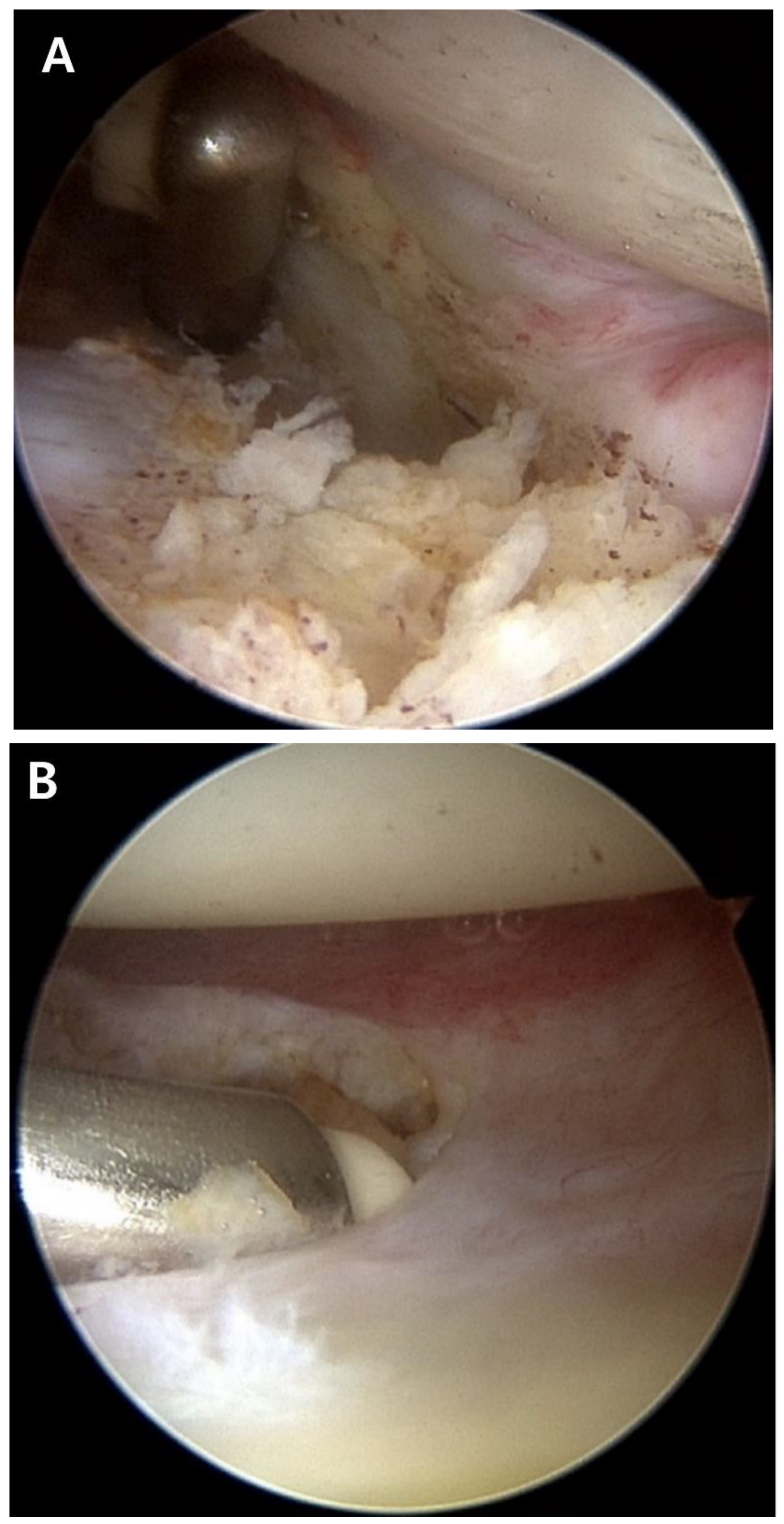

ACR was performed in the lateral decubitus position under general anesthesia. The fluid used during surgery was mixed with 1 mg of epinephrine per 3 L of normal saline, and the water pressure was maintained at 30–50 mmHg using an automatic infuser (10 K Fluid System, ConMed Linvatec, Largo, FL, USA). No abnormalities were observed in the rotator cuff, biceps long-head tendon, or glenohumeral joints on arthroscopic examination. ACR was performed according to the regular sequence, starting with the release of the rotator interval, middle glenohumeral ligament, and inferior and posterior capsules using a 3.0-mm 90° electrocautery device (Arthrocare, Smith & Nephew, Memphis, TN, USA) (Fig. 2). After ACR, the ROM under general anesthesia was defined as 150° forward flexion, 150° abduction, level of the 8th thoracic vertebral body for internal rotation, and 80° external rotation.

Figure 2.

Arthroscopic capsular release was performed. A. Release of the thickened middle glenohumeral ligament was performed. B. The inferior capsule was released using a radiofrequency ablation device. C. Engorgement synovitis and capsule thickening were observed.

Figure 2.

Arthroscopic capsular release was performed. A. Release of the thickened middle glenohumeral ligament was performed. B. The inferior capsule was released using a radiofrequency ablation device. C. Engorgement synovitis and capsule thickening were observed.

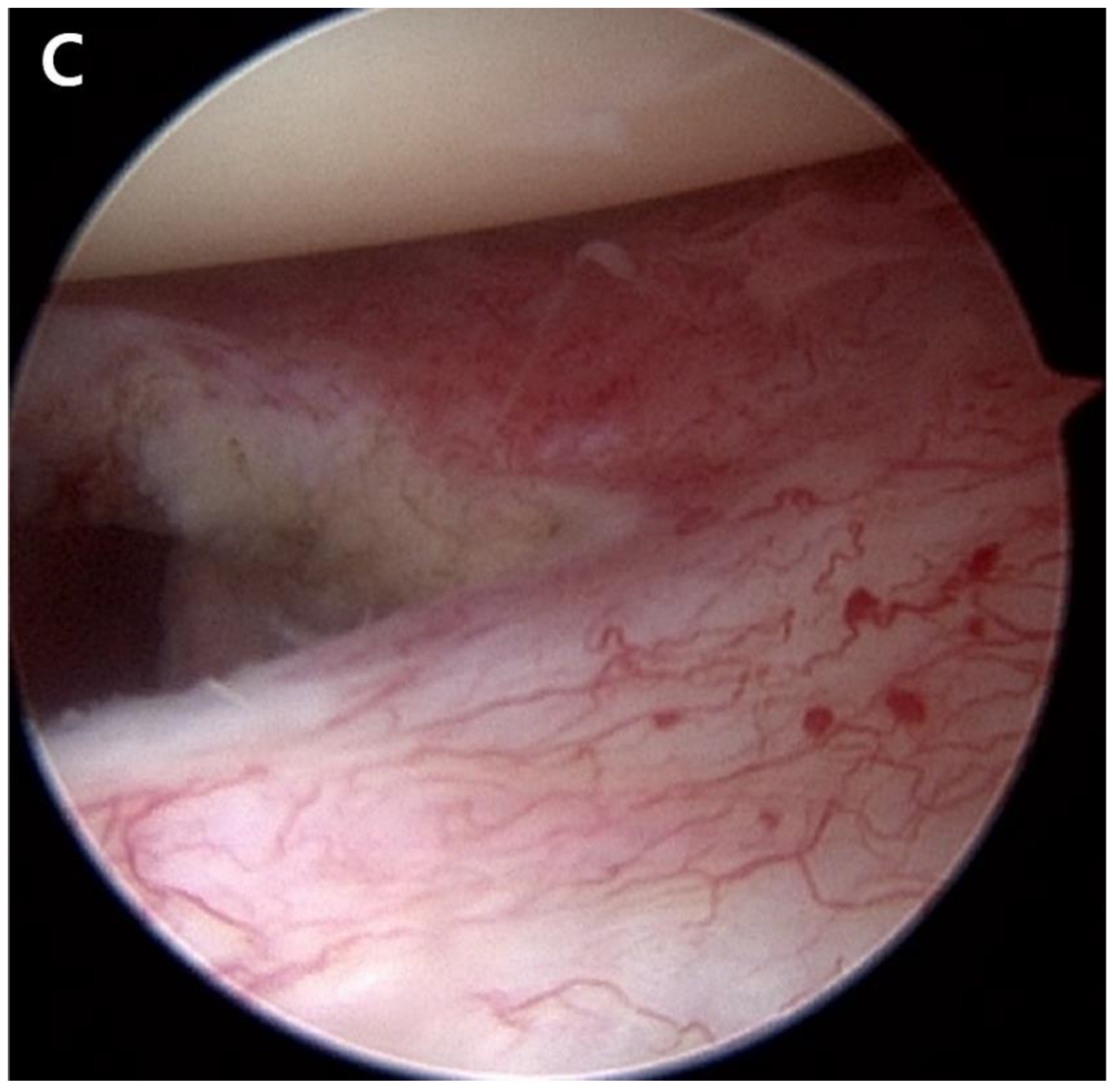

At 6-months postoperatively, functional outcomes were reported as a VAS score of 2, an ASES score of 79, and a CMS score of 75. Shoulder ROM was assessed as 135° forward flexion, 135° abduction, 70° external rotation, and internal rotation of the 10th thoracic vertebra. Radiographs showed an intact joint space and congruency (Fig. 3).

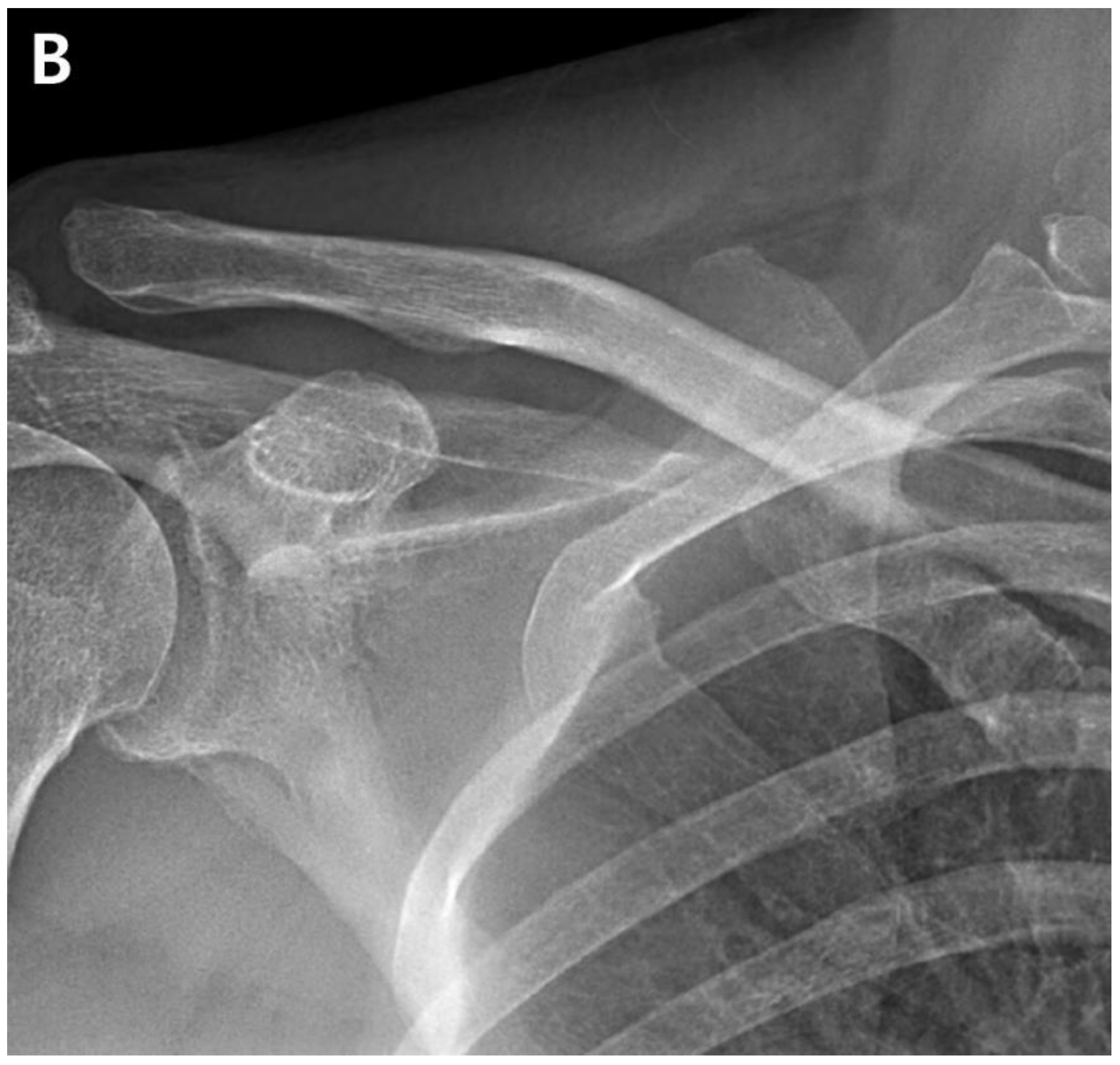

Figure 3.

A. Immediate postoperative anteroposterior radiograph. B. Anteroposterior radiograph of the shoulder at 6-months postoperatively showed no significant change in the radiographic findings of the glenohumeral joint.

Figure 3.

A. Immediate postoperative anteroposterior radiograph. B. Anteroposterior radiograph of the shoulder at 6-months postoperatively showed no significant change in the radiographic findings of the glenohumeral joint.

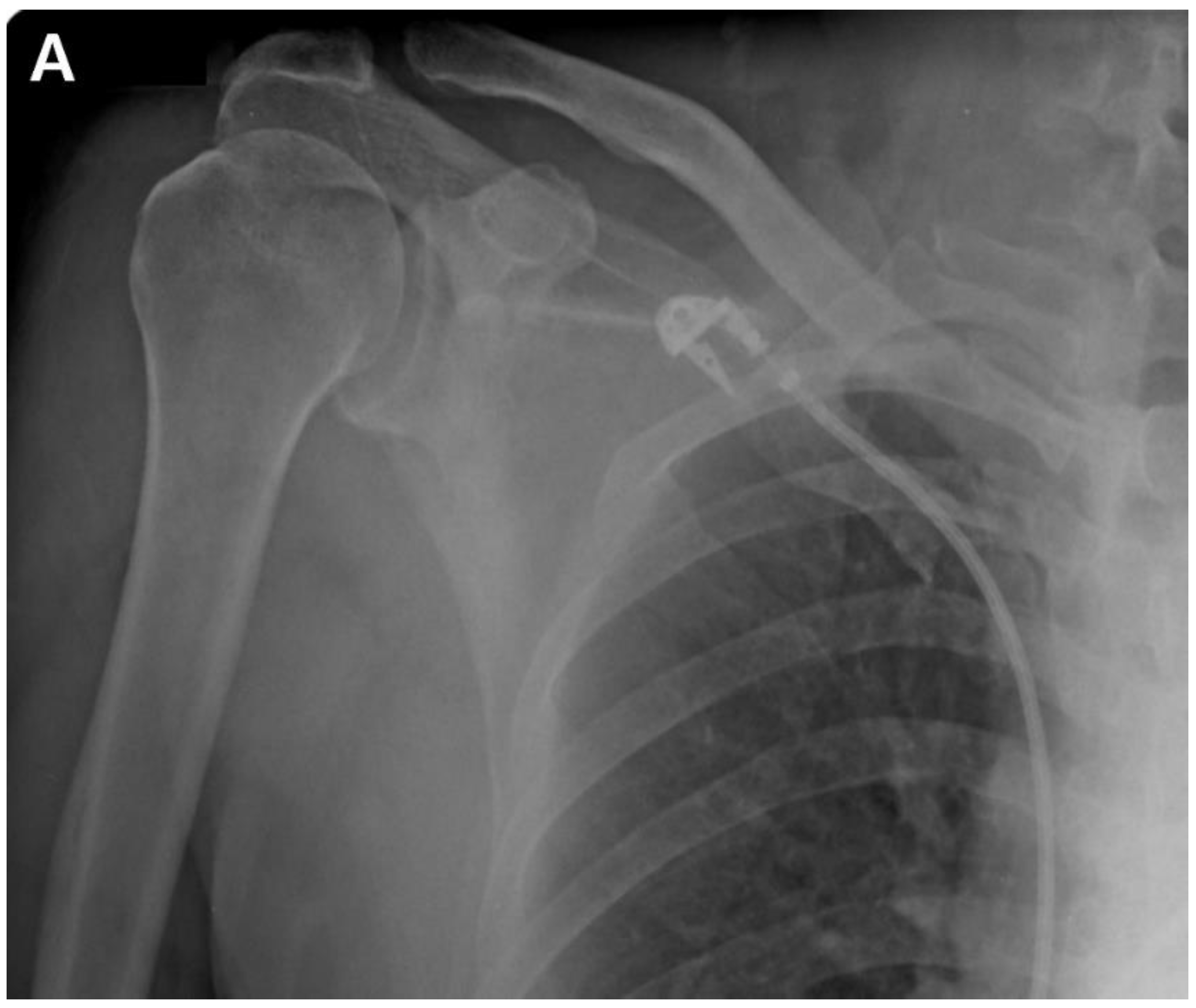

The patient returned to the hospital 21 months after the ACR with right shoulder pain. Plain shoulder anteroposterior radiography and MRI showed a subchondral cyst and a high bone marrow signal on the epiphysis of the superomedial area of the humeral head on T2-weighted images, suggesting avascular osteonecrosis of Cruess stage II (Fig. 4). The patient denied any traumatic injury, radiotherapy, exacerbation of chronic hepatitis, alcohol consumption, or use of other medications. The patient received six intra-articular injections of glucocorticoids during the 15 months of open follow-up at another institution. It is unclear whether the six intra-articular injections were corticosteroids. At 3-years postoperatively, his VAS score was 3, ASES score was 63, and CMS score was 59, indicating increased discomfort. As the patient found the discomfort tolerable in terms of both work capacity and activities of daily living, we decided to maintain the current status and continue observation until osteonecrosis progressed (Fig. 5.)

Figure 4.

A. Postoperative plain radiograph obtained at 21 months post-ACR. B. Oblique coronal T1 fat-suppressed MRI. C. Oblique coronal T2 fat-suppressed MRI shows osteolytic changes in the superomedial humeral head. MRI shows cystic changes in the epiphyseal area, but articular congruity remains preserved.

Figure 4.

A. Postoperative plain radiograph obtained at 21 months post-ACR. B. Oblique coronal T1 fat-suppressed MRI. C. Oblique coronal T2 fat-suppressed MRI shows osteolytic changes in the superomedial humeral head. MRI shows cystic changes in the epiphyseal area, but articular congruity remains preserved.

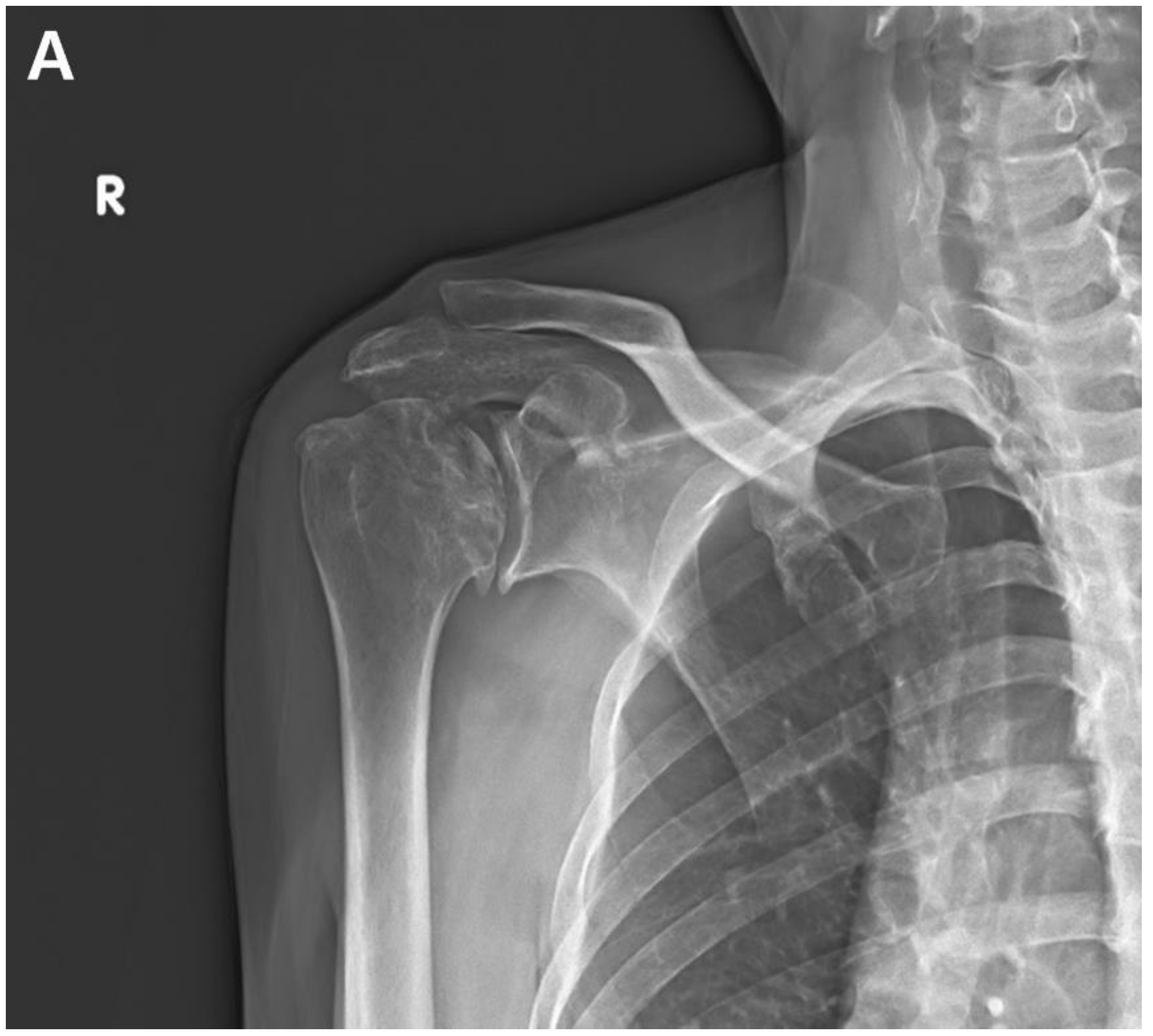

Figure 5.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the shoulder shows articular collapse on the superomedial side of the humeral head at 3-years postoperatively.

Figure 5.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the shoulder shows articular collapse on the superomedial side of the humeral head at 3-years postoperatively.

3. Discussion

ACR is a reliable surgical procedure clinically performed in patients with persistent shoulder stiffness. However, the occurrence of osteonecrosis of the humeral head after arthroscopic surgery reflects critical damage to the shoulder joint, necessitating revision surgery [

4]. The case presented here involved a patient with predisposing risk factors for osteonecrosis, including a history of chronic alcohol consumption, repeated intra-articular glucocorticoid injections, and previous shoulder surgery.

In previous clinical studies, recurrent stiffness and axillary nerve injury have been reported as complications of ACR [

10]. However, postoperative osteonecrosis has not been documented. Dilisio et al. hypothesized that associated surgical injuries could be caused by knots, the position of the suture anchor at the greater tuberosity or biceps, and aggressive use of a radiofrequency ablation device

7. Goto et al. demonstrated that the use of metal or multiple anchors placed at the greater tuberosity injures the anterolateral branch of the anterior circumflex humeral artery (ACHA) [

8]. Damage to the arcuate artery can cause osteonecrosis of the humeral head in patients undergoing biceps tenodesis or tenotomy [

11]. In our case, the use of radiofrequency ablation may have been associated with the development of osteonecrosis.

Circulation to the humeral head is facilitated by anastomoses involving the ACHA, posterior circumflex humeral artery (PCHA), and thoracoacromial artery [

9]. The superomedial aspect of the humeral head is particularly prone to osteonecrosis because of compromised arterial perfusion from the interosseous artery, a branch of the ACHA [

8]. Given that our patient had undergone previous surgery for acromioclavicular joint dislocation iatrogenic injury to the thoracoacromial artery may have occurred [

4]. A pseudoaneurysm involving the acromial branch of the thoracoacromial artery near the anterior portal was reported during an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair [

4]. Potential injuries to the thoracoacromial artery and ACHA can occur during plate fixation or arthroscopic procedures. Recent research has demonstrated that the PCHA contributes significantly to blood supply to the interosseous artery of the humeral head [

5,

12]. Although the PCHA may remain functional, the combined effects of intra-articular glucocorticoid injections and alcohol consumption may have critical effects, as detailed below.

Alcohol induces lipid deposition in osteocytes, increases adipogenesis, and decreases osteogenesis [

13]. Alcohol consumption has time- and dose-dependent effects on osteonecrosis [

13,

14]. Another clinical study showed that the occurrence of osteonecrosis was associated with a weekly ethanol consumption of > 320 g per week for more than 6 months [

13,

14]. In this case report, the patient’s consistent alcohol consumption of 40 g ≥ 5 times per week for 25 years, a time-dependent factor, may have contributed to the development of osteonecrosis. Although hepatitis B is not recognized as a risk factor, its impact on bone quality is notable in the context of liver cirrhosis [

13].

Complications of intra-articular steroid injections include septic arthritis, corticosteroid flares, elevated blood glucose levels, tendon rupture, chorioretinopathy, osteonecrosis, chondrotoxicity, and skin changes [

11]. Glucocorticoids can cause inadequate vascular supply, changes in blood flow, inflammatory processes, changes in lipid metabolism, and an imbalance between osteogenesis and adipogenesis in the bone marrow 13,15. Intra-articular steroid injections are commonly used to treat adhesive capsulitis, resulting in reduced pain and improved ROM [

15]. However, the administration of glucocorticoids can increase the risk of osteonecrosis by up to 20-fold, and discontinuation of corticosteroid treatment does not completely reverse the pathogenic processes responsible for osteonecrosis [

13]. Thus, intra-articular steroid injections are considered a significant risk factor for humeral head necrosis.

This case report had several limitations. First, the index surgery for acromioclavicular dislocation was performed at another hospital; therefore, defined medical records or details of the surgery could not be identified. Second, during the follow-up period, the history of preoperative medical treatment or intra-articular injections from other clinicians was not fully documented. Third, subjective masking of the patient in identifying his drinking history after ACR was possible, and compliance with rehabilitation treatment, such as ROM exercises after surgery, could not be verified.

4. Conclusion

ACR is one of the most reliable treatment options for post-operative shoulder stiffness and adhesive capsulitis that does not improve with standard conservative treatment. However, after ACR, our case demonstrated progressive osteonecrosis of the humeral head, which is an irreversible deterioration that may require additional surgical treatment, such as shoulder replacement. Therefore, surgeons need to be aware of possible osteonecrosis that may develop after ACR and should perform regular follow-up radiography for a sufficient time after surgery, particularly when treating patients with risk factors for osteonecrosis of the humeral head, such as chronic alcohol diseases and multiple steroid injections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jae-Hoo Lee. and Hyung-Suh Kim.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Hyung-Suh Kim.; writing—review and editing, Jae-Hoo Lee.; visualization, Kyung-Wook Nha & Jae-Hoo Lee.; supervision, Kyung-Wook Nha & Jae-Hoo Lee.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inje University Iisan Paik Hospital (2022-09-009 / 14 Nov, 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Millar, N.L.; Meakins, A.; Struyf, F.; Willmore, E.; Campbell, A.L.; Kirwan, P.D.; Akbar, M.; Moore, L.; Ronquillo, J.C.; Murrell, G.A.C.; et al. Frozen shoulder. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2022, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Lee, H.J. Essential surgical technique for arthroscopic capsular release in the treatment of shoulder stiffness. JBJS Essent Surg Tech 2015, 5, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.I.K.; Cho, H.L.; Hwang, T.H.; Wang, T.H.; Cho, H. Rapidly progressive osteonecrosis of the humeral head after arthroscopic Bankart and rotator cuff repair in a 66-year old woman: A case report. Clin Shoulder Elbow 2015, 18, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keough, N.; Lorke, D.E. The humeral head: A review of the blood supply and possible link to osteonecrosis following rotator cuff repair. J Anat 2021, 239, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cehelyk, E.K.; Stull, J.D.; Patel, M.S.; Cox, R.M.; Namdari, S. Humeral head avascular necrosis: Pathophysiology, work-up, and treatment options. JBJS Rev 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Jeong, H.J.; Shin, S.J.; Yoo, J.C.; Rhie, T.Y.; Park, K.J.; Oh, J.H. Rapid progressive osteonecrosis of the humeral head after arthroscopic rotator cuff surgery. Arthroscopy 2018, 34, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilisio, M.F.; Noble, J.S.; Bell, R.H.; Noel, C.R. Postarthroscopic humeral head osteonecrosis treated with reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2013, 36, e377–e380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, M.; Gotoh, M.; Mitsui, Y.; Okawa, T.; Higuchi, F.; Nagata, K. Rapid collapse of the humeral head after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015, 23, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, B.G.; Elliott, M.P. Pseudoaneurysm after arthroscopic subacromial decompression and distal clavicle excision. Orthopedics 2014, 37, e596–e599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardani-Kivi, M.; Hashemi-Motlagh, K.; Darabipour, Z. Arthroscopic release in adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: A retrospective study with 2 to 6 years of follow-up. Clin Shoulder Elb 2021, 24, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keough, N.; de Beer, T.; Uys, A.; Hohmann, E. An anatomical investigation into the blood supply of the proximal hu-merus: Surgical considerations for rotator cuff repair. JSES Open Access 2019, 3, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hettrich, C.M.; Boraiah, S.; Dyke, J.P.; Neviaser, A.; Helfet, D.L.; Lorich, D.G. Quantitative assessment of the vascularity of the proximal part of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010, 92, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konarski, W.; Poboży, T.; Konarska, K.; Śliwczyński, A.; Kotela, I.; Hordowicz, M.; Krakowiak, J. Osteonecrosis related to steroid and alcohol use-an update on pathogenesis. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, B.H.; Jones, L.C.; Chen, C.H.; Cheng, E.Y.; Cui, Q.; Drescher, W.; Fukushima, W.; Gangji, V.; Goodman, S.B.; Ha, Y.C.; et al. Etiologic classification criteria of ARCO on femoral head osteonecrosis Part 2: Alcohol-associated osteonecrosis. J Arthroplasty 2019, 34, 169–174e1 e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honcharuk, E.; Monica, J. Complications associated with intra-articular and extra-articular corticosteroid injections. JBJS Rev 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).