Background

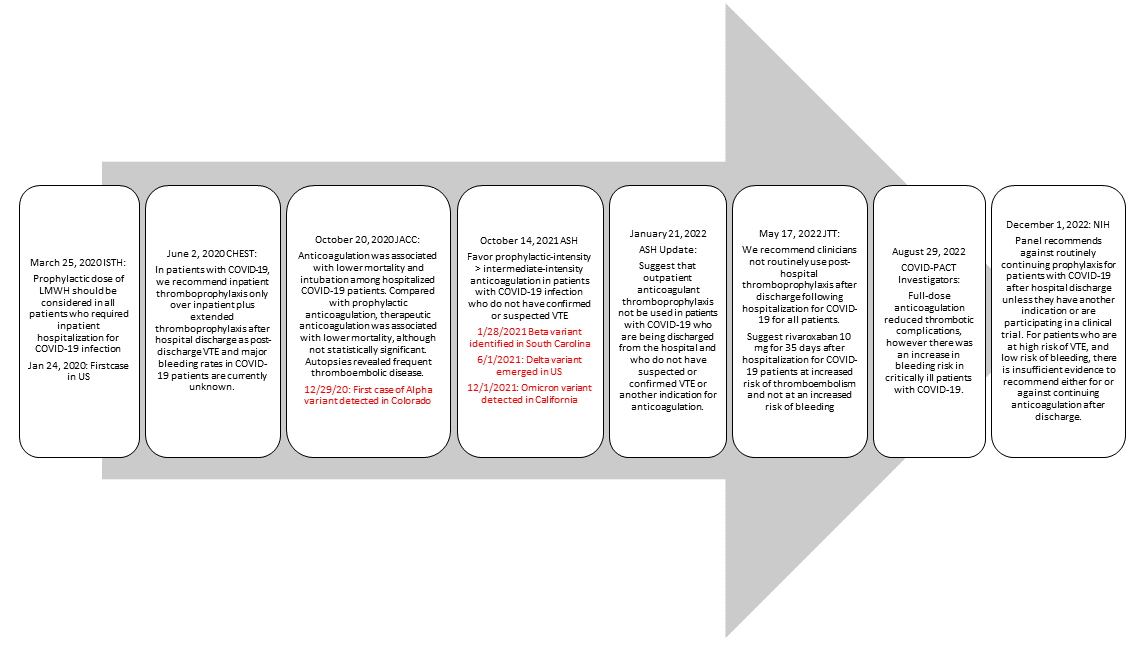

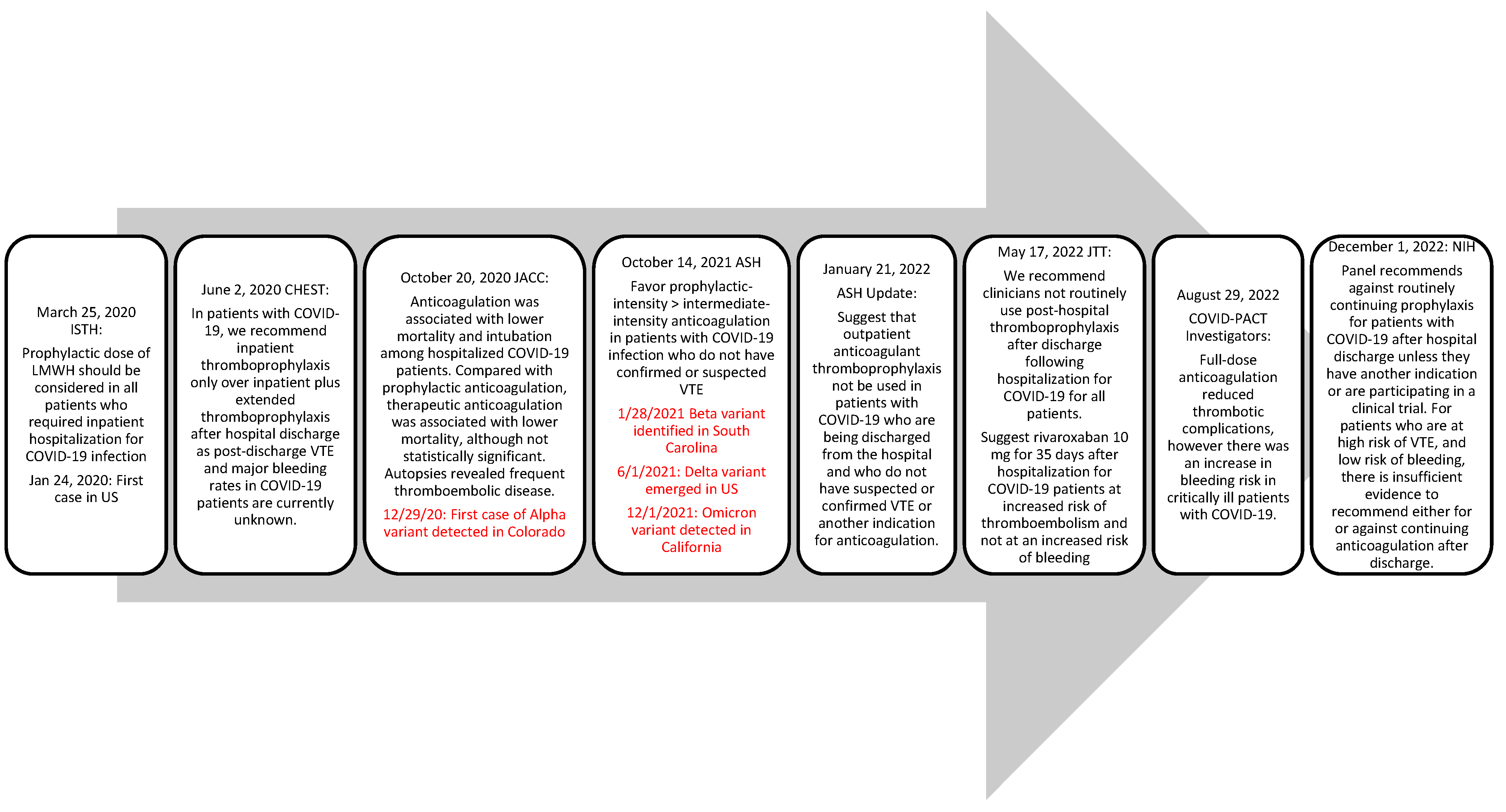

COVID-19 infection has been associated with a hypercoagulable state, an extensive inflammation process marked by elevated D-dimer, and higher incidence of thrombotic events. Presenting evidence throughout the pandemic has shown that patients hospitalized for COVID-19 infection should receive anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis (Helms 2020, Spyropoulos 2020, Poor 2021). Similarly, Nadkarni and et al showed that anticoagulation was associated with lower mortality in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection compared to no anticoagulation (Nadkarni 2020). Across various guidelines, thromboprophylaxis is recommended consistently for hospitalized patients diagnosed with COVID-19 regardless of thrombotic diagnoses. Based on newly available clinical outcome data and changes to the COVID-19 variants, guidance regarding the choice of anticoagulation, dosage, and duration were updated as shown in

Figure 1.

Prescribing thromboprophylaxis on discharge is not routine for patients with COVID-19. In the event of confirmed a VTE diagnosis, therapeutic anticoagulation for a minimum of 3 months is recommended with the regimen at the provider’s discretion at discharge (Spyropoulos AC, 2020). However, there is evidence to suggest that for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection without a VTE event, thromboprophylaxis at discharge may reduce future VTE occurrences. Giannis and colleagues found that patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 experienced a higher occurrence of VTE, arterial thromboembolism and all-cause mortality. The composite primary outcome rate was 7.13% within 90-days after discharge and incidence was lower when patients received post-discharge thromboprophylaxis (Giannis, 2020).

Although not directly related to COVID-19 infection specifically, the MARINER study assessed post-discharge thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients by observing rivaroxaban 10 mg or 7.5 mg once daily versus placebo for 45 days after hospital discharge. There was no statistically significant superiority in preventing venous thromboembolic events, however there was a 28% relative risk reduction in thromboembolic events. Incidence of major bleeding was not statistically significant (Spyropoulos AC, 2020).

Hennepin Healthcare System (HHS) established a practice guidance document in May 2020 for anticoagulation use in COVID-19 patients for extended-thromboprophylaxis at discharge based on literature reports. This guideline included consideration for a 30-days prescription for apixaban 2.5 twice daily, rivaroxaban 10 mg daily, or no therapy at discharge based on patients’ risk factors, which included severity of COVID-19 infection, risk of a VTE event (elevated D-dimer lab value), and risk of bleeding.

With inconclusive recommendations from professional guidance regarding post-discharge thromboprophylaxis and newly emerging COVID-19 variants over time, the purpose of this study is to describe HHS’s prescribing pattern and associated outcomes correlated with COVID-19 variants. This will further improve understanding of the role of post-discharge prophylaxis and identify potential improvement opportunities for patient care.

Methods

This is a single-center retrospective chart review of post-discharge thromboprophylaxis use in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and hospitalized within HHS from April 1st, 2020 to December 31st, 2021. Patients were included in the study if they were discharged with a COVID-19 diagnosis and had a hospital stay of 3 or more days. Patients less than 18 years old, incidental COVID-19 findings, on chronic anticoagulation, or had a diagnosis of VTE during their COVID-19 hospitalization stay were excluded.

Data of interest were collected and assessed utilizing the electronic health record (EHR) and billing ICD-10 codes; demographic characteristics include age, sex, race, weight, height, and BMI; laboratory values obtained during hospitalization were D-dimer and serum creatinine; new anticoagulant that was filled at discharge for patients with a COVID-10 diagnosis. New documented VTE, death within 30 days of prescribed anticoagulation, newly documented arterial thromboembolism events were collected for efficacy assessment, death due to bleeding and emergency department encounters or admissions within 30 days of new anticoagulation were analyzed to assess safety.

The primary objective of the study is to determine the prescribing practice patterns of post hospital discharge with extended thromboprophylaxis in COVID-19 patients without diagnosis of VTE compared to the total number of post hospital discharge COVID patients without diagnosis of VTE who are eligible for extended-thromboprophylaxis per the internal HHS COVID guidance document. The secondary objectives include evaluating the efficacy outcomes based on new thromboembolic events or death related to thrombotic events and assessing the safety of extended-thromboprophylaxis using the International Society of thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) criteria for major bleeding.

Information for the study gathered from the EHR was analyzed on Excel worksheets and statistics were generated using SPSS Version 27. The Institutional Review Board at Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute reviewed and approved this study.

Results

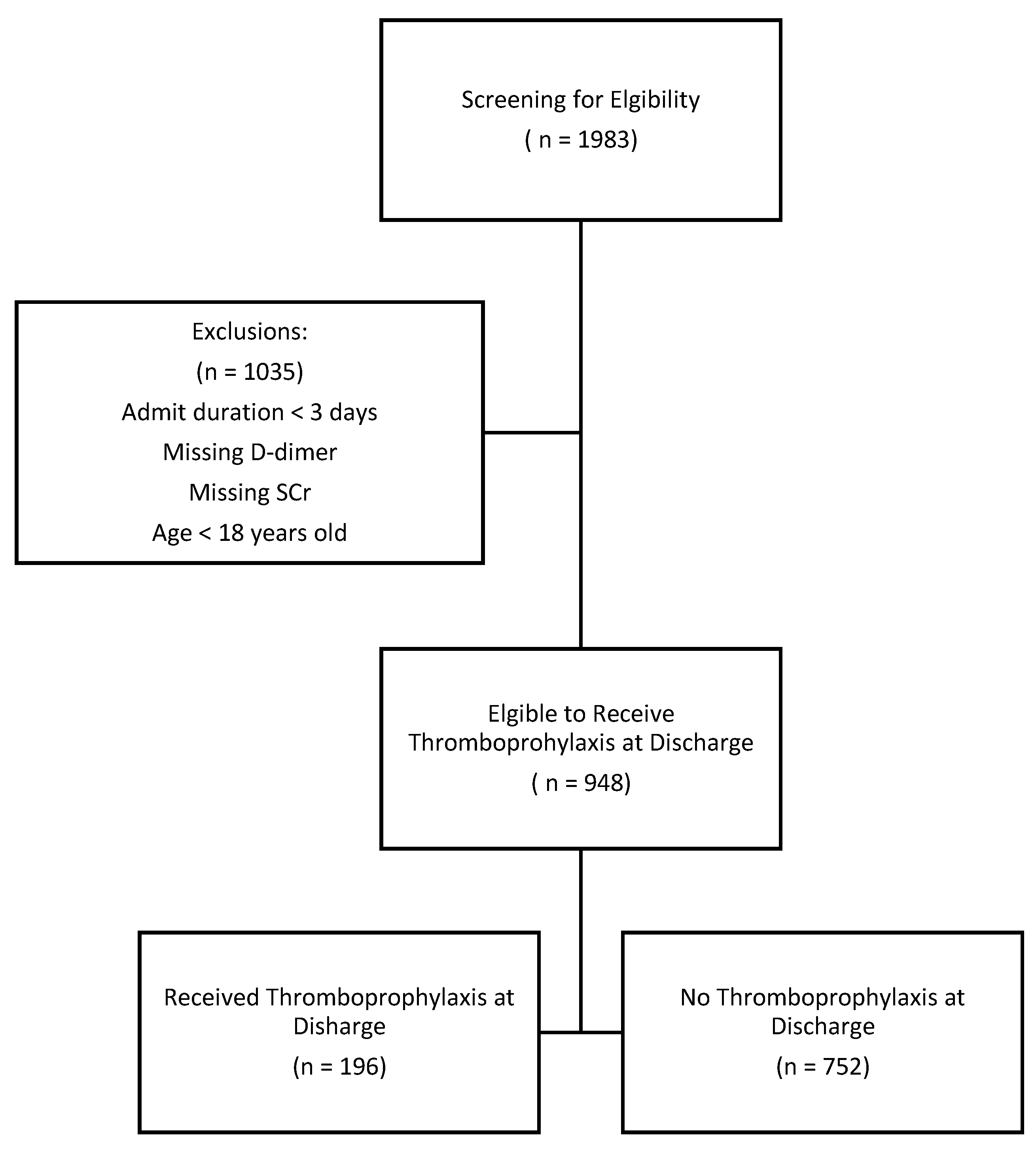

Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 infection within HHS from April 1

st, 2020 to December 31st, 2021 were reviewed for eligibility to receive thromboprophylaxis at discharge. A total of 1983 patients were positive for COVID-19 infection during their index hospitalization. After excluding patients less than 18 years old, hospitalization duration of less than 3 days, missing D-dimer, and missing serum creatinine, 948 (47.7%) patients qualified to receive post-discharge thromboprophylaxis. Of those eligible, 196 (21%) patients obtained either apixaban or rivaroxaban at discharge for thromboprophylaxis as shown in

Figure 2.

Baseline characteristics were balanced between groups (

Table 1). The mean age was 58 years, 389 (41%) were women, 559 (59%) were men, and the mean body-mass index was 31.33 kg/m

2. During hospitalization, 798 patients (84%) had a creatinine clearance of ≥50 mL/min, 65 patients (7%) had a creatinine clearance of 30 to < 50 mL/min, and 86 patients (9%) had creatinine clearance of < 30 mL/min. In patients who received thromboprophylaxis at discharge, the median (IQR) D-dimer was 1114.50 (448.50-4245.50). Comparatively, in patients with no thromboprophylaxis at discharge, the median (IQR) D-dimer was 452 (279.25 – 1040.0) (p = 0.00). Furthermore, median (IQR) of hospitalization duration was 11 days (6-25 days) in patients who received thromboprophylaxis at discharge compared to 7 days in duration (4-13 days) (p = 0.00), in patients who did not receive thromboprophylaxis at discharge.

For the primary outcome, according to HHS’s internal guideline, 948 patients were eligible to receive post-discharge thromboprophylaxis. A total of 196 (21%) patients were discharged with thromboprophylaxis at discharge (

Table 2). Physician prescribing patterns were temporally distributed by variant discovery as shown in

Table 3. For the secondary outcomes, 19 (10%) patients experienced a thromboembolic event within 30 days of discharge in patients discharged with thromboprophylaxis compared to 41 (5%) patients who did not receive thromboprophylaxis. Notably, the occurrence of VTE was statistically significant between the study arms. Additionally, regarding secondary outcomes aimed to evaluate safety, 5 (2.5%) patients in the thromboprophylaxis-prescribed group had a bleeding event, whereas 19 (2.5%) patients had occurrences of bleeding who did not receive thromboprophylaxis on discharge with no statistical significance (

Table 2).

Discussion

In this single-center study at HHS, current prescribing practices of extended-thromboprophylaxis at discharge were evaluated for congruency with the internal guideline. Prescribing patterns throughout the pandemic with different variants were also explored. From the primary outcomes, of the eligible patients able to receive thromboprophylaxis at discharge, 21% of patients were prescribed either apixaban or rivaroxaban. This showed that prescribing practices at HHS were inconsistent with our internal practice guidelines, therefore suggesting potential selection bias based on prescriber discretion.

Among the various emerging strains during the pandemic, it was found that the alpha strain carried higher risk for ICU admission and mortality. Compared to the Delta strain, the Omicron variant was noted to be less clinically severe based on less hospitalizations, need for mechanical ventilations, requirement for supplemental oxygen and fewer deaths (CDC 2023). Confounding factors include the evolution of therapeutic modalities as well as the development of vaccines during this time (Florensa 2022). At HHS, utilization of thromboprophylaxis decreased as the associated symptoms with each COVID-19 variant became less clinically severe, mirroring the progression of the pandemic.

From the secondary outcomes, higher rates of bleeding were observed in patients who did not receive thromboprophylaxis at discharge. This may be attributed to their elevated baseline bleeding risk; hence prophylactic therapy was not initially prescribed. Conversely, higher rates of thromboembolic events occurred in patients who received thromboprophylaxis at discharge suggesting that these patients were at higher risk of developing clots. Concurrent comorbidities and medical history can also contribute to a patient’s thromboembolic risk development including cancer, age, and immobilization. Other faucets to explore include the role of therapeutic anticoagulation at discharge. In a cohort study, Li et al found that in patients who received therapeutic anticoagulation at discharge, there was a reduced risk of symptomatic VTE (OR, 0.18;95% CI, 0.04-0.75; P=0.02) (Li 2021). Additional research will be needed to compare prophylaxis versus therapeutic dosing at discharge.

The review of HHS’s internal guideline suggests that it does not directly support the use of post-discharge thromboprophylaxis likely due to provider preference and insufficient evidence available to endorse routine utilization. Conversely, a trial published after the study’s period by Ramacciottie and colleagues, as part of the MICHELLE trial, showed a decreased incidence of thromboembolic events. Ramacciottie et al explored the use of rivaroxaban 10 mg versus no anticoagulation for post-discharge thromboprophylaxis after COVID-19 hospitalization. Inclusion criteria consisted of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 for a minimum of 3 days, have an increased risk for venous thromboembolism defined as an International Medication Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism (IMPROVE) VTE score of 2 or 3 with a D-Dimer of over 500 ng/mL or a score of 4 or more. Eligible patients were designated to receive rivaroxaban or no anticoagulation at discharge. The results revealed that in patients with high-risk of VTE who received rivaroxaban 10 mg for 35 days after COVID-19 hospitalizations had a reduction in major or fatal thromboembolic events compared to no extended thromboprophylaxis. No major bleeding occurred in either group (Ramacciotti 2022).

Compared to our study which had less stringent criteria, the MICHELLE trial was randomized with a larger sample size and had an objective method (IMPROVE-VTE score) to classify which patients received post-discharge prophylaxis based on their risk of developing a clot. Their patient population may entail more severe patients given the specific criteria that must be met to receive post-discharge thromboprophylaxis compared to our patient population.

Though the MICHELLE to suggest an improved clinical outcome in reducing thrombotic events with thromboprophylaxis, current professional guidelines recommend against routine post-discharge thromboprophylaxis in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 infection largely due to inadequate evidence (CDC, ASH). However, if patients are discharged on VTE prophylaxis, individual risk factors for VTE and bleeding risks should be thoroughly evaluated. Therefore, post-discharge thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban 10 mg daily for 35 days may be considered in patients with increased risk of thromboembolism and not at an increased risk of bleeding (Barnes 2022).

There are notable limitations to this study including the small sample size and inherent aspects of a retrospective review such as its dependence on detailed and comprehensive documentation to accurately capture the decision-making process of healthcare providers. The incongruency in prescribing pattern compared to the guidance document further implies the possibility of selection bias among health care providers. Additionally, the continuous development of professional guidelines and emergence of new variants presented challenges given the study represented only a momentary capture of prescribing patterns during that time.

Conclusion

Although the prescribing practices at HHS are incongruent with the internal guidelines provided within the system, the prescribing habits over time were reflective of newly published evidence and guideline recommendations. Moreover, determining the appropriate patient population for post-discharge thromboprophylaxis with COVID-19 infection remains a challenge. Additional prospective double-blinded placebo-controlled trials are needed to further provide guidance on post-discharge management of thromboprophylaxis in the corresponding to different COVID variants.

References

- Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46:1089-98.

- Poor, HD. Pulmonary thrombosis and thromboembolism in COVID-19. Chest. 2021; 160(4):1471-1480. [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos AC, Levy JH, Ageno W, et al. Scientific and Standardization Committee communication: clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost 2020; 18:1859-65.

- Ramacciotti E, Agati LB, Calderaro D, et al. Rivaroxaban versus no anticoagulation for post-discharge thromboprophylaxis after hospitalization for COVID-19 (MICHELLE): an open-label, multicentre, randomized, controlled trial. Lancet 2022; 399:50-59.

- Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1023-1026. [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni GN, Lala A, Bagiella E, et al. Anticoagulation, bleeding, mortality, and pathology in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(16):1815-1826. [CrossRef]

- Barnes GD, Burnett A, Allen A, et al. Thromboembolic prevention and anticoagulant therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: updated clinical guidance from the anticoagulation forum. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2022;54(2):197-210. [CrossRef]

- Cuker A, Tseng EK, Nieuwlaat R, et al. American Society of Hematology 2021 guidelines on the use of anticoagulation for thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2021;5(3):872-888. [CrossRef]

- Moores LK, Tritschler T, Brosnahan S, et al. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of VTE in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: CHEST guidelines and expert panel report. Chest. 2020;158(3):1143-1163. [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health. Available at https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/. Accessed May 21, 2022.

- Cuker A, Tseng EK, Nieuwlaat R, et al. American Society of Hematology living guidelines on the use of anticoagulation for thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19: July 2021 update on postdischarge thromboprophylaxis. Blood Adv. 2022;6(2):664-671. [CrossRef]

- Giannis D, Allen SL, Davidson A, et al. Thromboembolic outcomes of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the 90-day post-discharge period: early data from the Northwell CORE-19 Registry. Blood. 2020;136:33–34.

- Spyropoulos AC, Ageno W, Albers GW, et al. Post-discharge prophylaxis with rivaroxaban reduces fatal and major thromboembolic events in medically ill patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:3140–3147.

- Bohula EA, Berg DD, Lopes MS; COVID-PACT Investigators. Anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy for prevention of venous and arterial thrombotic events in critically ill patients with COVID-19: COVID-PACT. Circulation. 2022;146(18):1334-1356. [CrossRef]

- National Health Institute. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with COVID-19. National Health Institute. Published December 1, 2022. Accessed April 4, 2023. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/antithrombotic-therapy/.

- Florensa D, Mateo J, Spaimoc R. Severity of COVID-19 cases in the months of predominance of the alpha and delta variants. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1)15456. [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. SARS-CoV-2 variant classifications and definitions. Published March 20,2023. Assessed April 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-classifications.html#anchor_1679059484954.

- Li P, Zhao W, Kaatz S, et al. Factors associated with risk of postdischarge thrombosis in patients with COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11): e2135397. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).