1. Introduction

Greenhouse gas accounting conventions have played a major role in framing our understanding of what causes climate change and guiding policy responses [

1]. Since these conventions were framed climate science has advanced considerably and emission estimates have improved, in particular estimates of biosphere and ocean carbon flux. One recent advance in emissions accounting – consistent gross CO

2 accounting – has substantially boosted the value of land use emissions, particularly deforestation, placing fossil fuels second to land use as a carbon emission source [

2]. A second advance - emissions-based Effective Radiative Forcing (ERF) – has removed the need for contentious metrics to compare different gases [

3]. Together with the inclusion of cooling emissions, these advances allow us to better determine responsibility for present day warming and to re-examine policy responses.

The aim of this study is to consolidate arguments supporting these advances that promise more consistent, more inclusive, and less contentious accounting as summarised in

Table 1, and to combine and apply these to emissions since 1750. The novel aspect of this study is to determine the combined effect of these proposed advances, to test their validity and to explore their usefulness to climate policy.

2. Review of Novel Emissions Accounting Advances

2.1. Consistent CO2 Emissions Accounting

The IPCC inventory category Land Use/Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) reports

net CO

2 emissions and sinks on ‘managed’ land, whereas all other emissions, CO

2 or otherwise, are reported as

gross [

4]. Wedderburn-Bisshop 2024 reviews the arguments supporting consistent

gross accounting and its implications, finding that LULUCF has released more CO

2 than fossil fuels, with

gross emissions 2.8 times greater than

net since 1750 [

2]. Consistent accounting thereby boosts the relative importance of sectors causing LULUCF emissions, notably agriculture and forestry.

Net LULUCF CO

2 accounting was justified with the reasoning that it is the remaining atmospheric net CO

2 that affects climate and that fossil fuel carbon is ‘truly new carbon’, additional to the biosphere carbon pool. Gross carbon accounting (consistent with treatment of all other emissions) reasons that: carbon emissions from all sources are absorbed equally by growing vegetation, therefore the proportion of each emission remaining in the atmosphere is equal; that old growth deforestation carbon is equally ‘new carbon’; that vegetation growth both natural and anthropogenic (afforestation) is better described with gross accounting [

2].

2.2. Inclusive Accounting

Sector contributions are incomplete due to conventional partial accounting. This is most obvious in the case of fossil fuels, where co-emitted aerosols, whose cooling has until now masked most CO

2 warming, are rarely reported [

3]. Indeed, cooling emissions have been noted as cancelling warming of unrelated sectors [

5]. Including short term emissions leads to a more comprehensive and inclusive inventory, however there are other factors that must be considered, such as the dangers presented by aerosols to human health [

6] as well as implications for longer term warming (see 5.3).

Partial accounting is also evident in attributing land use emissions to agriculture. Although several authors have looked at comprehensive land and agriculture emissions, eg [

7], net accounting is used and past deforestation is overlooked. Fossil carbon emissions overtook land emissions in the 1960’s, but warming from past land carbon emissions continues. This can be rectified by incorporating past deforestation as done here, or by including carbon opportunity cost in yearly inventories [

8]. Agricultural fire emissions are also partially and inconsistently accounted, as discussed in

Supplementary Material.

2.3. Using ERF for Less Contentious Sector Comparison

Debate on how to compare the various greenhouse emission species has been robust, particularly comparing CO

2 to methane [

9], hindering agreement on mitigation effectiveness and sector comparisons [

10]. 100-year Global Warming Potentials (GWP

100) are the conventional IPCC metric, but recent advances in determining emissions-based Effective Radiative Forcing (ERF) and derived Global Surface Air Temperature (GSAT) change, as defined in the IPCC’s AR6 Section 6.4 and Supplementary Material 6.SM.1 [

3], present a more comprehensive and less contested means of comparing emission species.

Aviation is comparable to agriculture in that it produces an array of long- and short-lived emissions, aerosols, as well as water vapour and cloud impacts. ERF is now commonly used in aviation climate impact studies as the most accurate means of comparing these disparate emissions and impacts [

11]. Also, ERF is believed to produce more accurate estimates of climate impact for agriculture because conventional GWP use can distort mitigation effectiveness [

12]. Emissions-based ERFs are tested and constrained with historic observations, making them ideal for this study of warming since 1750 [

13]. Matthews et al., 2009, validate the use of sector cumulative emissions; finding that climate response is not sensitive to background concentrations or timing of those emissions [

14].

Although ERFs are seen to be most useful for this study, the benefit of GWPs is that their time periods can be chosen for future climate target dates [

10]. There are also dangers with applying ERFs to aerosols, in that by including cooling emissions this could distort their value, given that most cooling aerosols have a strong negative impact on health [

6], and aerosol ERF values still have high uncertainty [

15].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

Carbon emission timeseries from 1750 to 2020 are from the Global Carbon Budget, with Houghton and Castanho 2023 (H&C) LULUCF gross CO

2 data, with timeseries data for all other emission species from PRIMAP-hist, CEDS and FAO data plus fire emissions from the GFED4. Data source references are given in

Table S1. Data on land use carbon deficit are from Erb et al., 2018 [

16], and crop outputs are further allocated using biomass flows from IPCC AR5 chapter 11[

17]. Detailed data on agricultural emissions is now available (e.g. [

18]), but these studies do not capture past deforestation.

Emissions-based ERF values since 1750 are from the IPCC’s AR6 Section 6.4, and Supplementary Material 6.SM.1 [

3], with error updates from Roesch et al., 2024 [

19]. Data are limited to the 11 emission species for which emissions-based ERF is documented [

3], being carbon dioxide (CO

2), methane (CH

4), nitrous oxide (N

2O), halocarbons, nitrogen oxides (NOx), non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOC), carbon monoxide (CO), sulphur dioxide (SO

2), organic carbon (OC), black carbon (BC) and ammonia (NH

3). Land use albedo change is from AR6 chapter 7 [

20].

This study has not applied time-discounted land carbon emissions. We believe that no discount rate is warranted when using gross accounting of CO2 as we do here, because cumulative ERF is calculated for the entire period from 1750, and any discounting based on carbon drawdown could be equally applied to fossil fuel and LULUCF carbon emissions because they share the same fate: biosphere drawdown with a remaining airborne fraction.

3.2. Attributing ERF and GSAT to Sectors

Sectors have been chosen to demonstrate the impact of this novel accounting, being ‘Fossil Fuel and Industry’ (shortened to ‘fossil fuel’ in this text); ‘Agriculture’, further divided into ‘Animal Agriculture’ and ‘Other Agriculture’; ’Forestry’; ‘Waste’; and ‘Other’. Animal Agriculture is identified separately due to its high emissions and land use. These sector groupings require dissecting to finer detail, but for the purpose of this study, they demonstrate the concepts. The agriculture categories include land and production emissions only, and do not include on-farm fossil fuel use, processing, or distribution.

LULUCF CO

2 emissions are allocated to sectors based on land carbon deficit proportions from Erb et al., 2018 [

16], being Infrastructure (2% of land carbon deficit), Cropland 25%, Grassland and grazing land 49%, and Forests 23%. These land use carbon deficit proportions are very close to those of Lal et.al., 2021 [

21]. Crop outputs are allocated in the same proportion as biomass flows, taken from IPCC AR5 chapter 11[

17], where all grazing land and 66% of crop output are attributed to animal agriculture, 34% of crop output is other agriculture, and 100% of forest products and woodfuel is allocated to Forestry.

Non-CO

2 emissions are attributed to sectors using timeseries data as listed in

Table S1, with resultant attribution in

Table S3. Non-CO

2 emissions related to crops are proportioned to sectors according to biomass flows, as above.

3.3. Errors and Accuracy

Recent fossil fuel CO

2 emissions are known to +/- 5% [

22], however biosphere carbon flow uncertainty is in the order of +/-20% [

23]. Aerosol cooling is an important contributor to this assessment that has an even higher uncertainty, in the order of +/-70% [

3]. Sector ERF uncertainty estimates are given in Results. These uncertainties imply that this study gives an indicative, rather than exhaustive result, however agriculture emissions are conservative.

Gross LULUCF CO

2 emission values from Houghton and Castanho, 2023, are conservative because: a) deforestation emissions are based on FAO

net in-country data, thereby excluding re-clearing [

24,

25]; b) gross forest loss from finer-grained remote sensing studies indicate that forest loss exceeds current estimates [

26,

27], perhaps four times greater in extent than previous assessments [

28]; c) emissions are understated due to narrowly defined managed land [

29]; and d) if loss of additional sink capacity were included this would increase gross LULUCF emissions by 20% [

30].

Additionally, there are two major reasons why these values are conservative. Firstly, this study is limited to emissions from 1750-2021, ignoring the 1100Gt CO

2 deforestation emissions prior to 1750 [

31]. Secondly, carbon from agricultural fires is excluded for reasons given in

Supplementary Material, which, if included would double agricultural carbon emissions [

32].

Several recently published data sets document agricultural emissions to a greater detail than that used here, e.g. [

33,

34], however these use conventional land carbon accounting and are not directly relatable to the sectors as used here. This offers a useful area for further study.

4. Results

Results of applying proposed accounting changes listed in

Table 1 are given below.

4.1. Consistent Gross LULUCF CO2 Accounting

Of the accounting advances applied here, consistent gross CO2 emissions accounting is the most unconventional but consequential. Gross accounting finds that since 1750 agriculture has emitted 98% as much CO2 as fossil fuel, and forestry has emitted 30% as much CO2 as fossil fuel.

Forestry carbon emissions (timber harvest and wood fuel) are estimated here proportionally to land carbon deficit. However, comprehensive forestry sources and sinks can be quite complex, e.g. [

35], therefore our Forestry estimate here should be seen as indicative.

4.2. Sector ERF and GSAT

ERF of each emission species is attributed to sectors as described in 3.2, and derived sector ERF and GSAT values are shown in

Table 2.

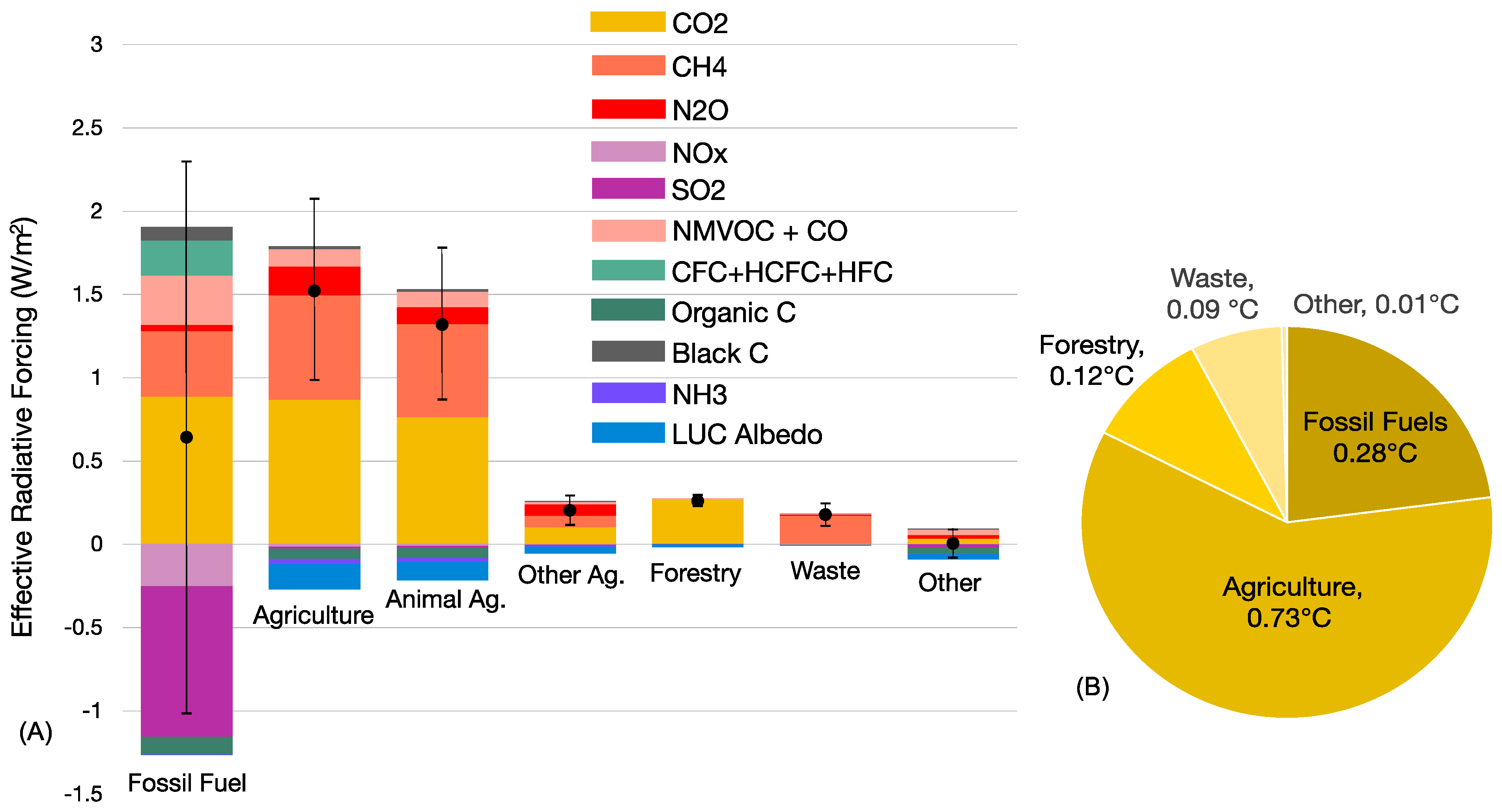

This attribution finds that agriculture has caused 0.73ºC (0.47º-0.99ºC) net GSAT warming from 1750 to 2020, with 87% of this (0.63ºC, 0.42º-0.85ºC) attributable to animal agriculture. Fossil fuels have caused 0.28ºC (-0.44º-1.00ºC) net GSAT change due to strong SO2 and NOx aerosol cooling. Methane, having little cooling co-emissions other than minor sulphur dioxide emissions from combustion of natural gas, is responsible for 0.60ºC (0.41º-0.78ºC) warming. Inclusive accounting finds that fossil fuel warming is 0.94°C together with 0.66°C cooling from co-emissions, whereas agriculture has caused 0.86°C warming but only 0.13°C cooling, with most of the cooling from land use albedo change and organic carbon from fires.

Table 2.

Attribution of emissions-based Effective Radiative Forcing (ERF) and Global Surface Air Temperature (GSAT) to emission species and sector.

Table 2.

Attribution of emissions-based Effective Radiative Forcing (ERF) and Global Surface Air Temperature (GSAT) to emission species and sector.

Emissions-based Effective Radiative Forcing (ERF)

and Global Surface Air Temperature (GSAT) Rise by Emission and Sector

|

|---|

| |

Fossil Fuel & Industry |

Animal Agriculture |

Other Agriculture |

Forestry |

Waste |

Other |

|

|

| Emission Species |

ERF |

GSAT |

ERF |

GSAT |

ERF |

GSAT |

ERF |

GSAT |

ERF |

GSAT |

ERF |

GSAT |

ERF by gas |

GSAT by gas |

| CO2 |

0.89 |

0.41 |

0.76 |

0.35 |

0.11 |

0.05 |

0.27 |

0.12 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.04 |

0.02 |

2.06 |

0.95 |

| Methane |

0.39 |

0.20 |

0.56 |

0.28 |

0.07 |

0.03 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.17 |

0.09 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.20 |

0.60 |

| N2O |

0.04 |

0.02 |

0.10 |

0.05 |

0.07 |

0.03 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.02 |

0.00 |

0.24 |

0.11 |

| NOx |

-0.25 |

-0.13 |

-0.01 |

-0.01 |

-0.00 |

-0.00 |

0.00 |

-0.00 |

-0.00 |

-0.00 |

0.00 |

-0.00 |

-0.27 |

-0.14 |

| SO2 |

-0.91 |

-0.48 |

-0.01 |

-0.01 |

-0.00 |

-0.00 |

-0.00 |

0.00 |

-0.00 |

-0.00 |

-0.02 |

-0.00 |

-0.94 |

-0.50 |

| NMVOC+CO |

0.30 |

0.17 |

0.09 |

0.06 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.44 |

0.25 |

| Halocarbons |

0.21 |

0.10 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.21 |

0.10 |

| Organic C |

-0.11 |

-0.05 |

-0.06 |

-0.03 |

-0.01 |

-0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

-0.00 |

-0.00 |

-0.04 |

-0.01 |

-0.21 |

-0.09 |

| Black Carbon |

0.08 |

0.05 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

-0.00 |

0.11 |

0.06 |

| Ammonia |

-0.00 |

-0.00 |

-0.02 |

-0.01 |

-0.01 |

-0.00 |

-0.00 |

-0.00 |

-0.00 |

-0.00 |

0.00 |

-0.00 |

-0.03 |

-0.02 |

| Albedo LUC |

0 |

0 |

-0.11 |

-0.06 |

-0.04 |

-0.02 |

-0.02 |

-0.01 |

0 |

0 |

-0.03

|

-0.12 |

-0.20 |

-0.10 |

| Net ERF & GSAT |

0.64 |

0.28 |

1.32 |

0.63 |

0.20 |

0.10 |

0.26 |

0.12 |

0.18 |

0.09 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

2.60 |

1.22 |

| % Net ERF & GSAT |

25% |

23% |

51% |

52% |

8% |

8% |

10% |

10% |

7% |

7% |

0% |

0% |

|

|

| ERF SE +/- |

1.66 |

|

0.45 |

|

0.09 |

|

0.03 |

|

0.07 |

|

0.08 |

|

|

|

Figure 3A presents data from

Table 2, showing sector ERF due to each emission species and land use albedo change, and Figure 3B presents GSAT warming due to each sector in °C.

4.3. Validation and Sensitivity Analyses

Gross LULUCF carbon accounting and sector attribution: Present-day land use offers a reasonability test on land carbon emissions, being the result of all previous land use changes. The 2019 IPCC report on climate change and land [

36] finds that grazing pastures take up 37% of the ice-free land; managed forests 22%; and cropland 12%, with built-up land taking up 1%. Grazing therefore uses 75% of agricultural land, with cropland using 25%. This compares with carbon deficit as used here of 49% for grazing, 25% for crops, 23% for forestry and 2% for infrastructure. This comparison is reasonable considering that cropland emissions are greater due to higher original forest cover, and about half of grazing land was originally grassland, resulting in lower carbon loss.

A sensitivity analysis was carried out using 15% higher and 15% lower gross LULUCF carbon emissions. This increased/decreased total carbon emissions, but the relative ranking of sectors did not change.

Sector contributions using ERF rather than GWPs: In other studies using this methodology, Dreyfus et al., 2022 [

5] used ERF in a similar way looking at fossil fuel and short-lived climate forcer contributions to warming, where they found fossil fuels had caused 20% of net global warming to 2015. Here we find fossil fuels caused 23% of net warming to 2020 (Figure 3B). In addition, Dreyfus et al. found methane to be responsible for 50% of GSAT temperature change, whereas we find it to have caused 49% of net GSAT.

As a reasonability test, from 1750 to 2020, 3,727Gt of CO2 and 26.1Gt of methane was emitted from all sources, causing 2.058W/m2 and 1.195W/m2 ERF respectively. Cumulative methane emissions therefore caused 41 times more ERF than CO2 since 1750 by weight. This value is between the conventional GWP100 factor of 28 and the GWP20 factor of 82. If emissions were tabulated each year using the conventional GWP100 factor, this would have underestimated methane’s present-day ERF by 46%.

A feature that is immediately apparent from Figure 3 (a) is the large uncertainty range of fossil fuel ERF, predominantly due to uncertainty of aerosol cooling. Although its value is uncertain, its cooling impact is well accepted, as well as the understanding that short term emissions have a long term impact through climate-carbon feedback [

37].

A sensitivity analysis was carried out using the same ERF dataset, but with emission sector proportions from recent emissions data (from 2000 to 2021). This approach is a test on sensitivity to sector proportions such as fossil fuels becoming the dominant CO2 emission source circa 1965, and the dramatic rise in all emission species, particularly the 250% rise in airborne methane. As expected, the fossil fuels/industry sector rose slightly in ranking, but agriculture remained the leading emissions sector.

5. Discussion

5.1. Significant Findings

Agriculture is clearly identified as the leading cause of global warming, substantially due to CO2 from past and present deforestation, followed by methane. Unlike fossil fuels, agriculture has produced minimal cooling emissions to offset warming.

Within this sector, animal agriculture provides ‘low hanging fruit’ mitigation opportunities that could benefit several Earth systems, particularly biodiversity and climate. Animal agriculture is the greatest methane emitter, but it also offers the greatest carbon opportunity cost/drawdown potential.

Inclusive accounting brings into focus the impact of methane, which has caused a substantial 49% of total net GSAT temperature change and 70% of net fossil GSAT, but has little cooling co-emissions, as noted by others [

5]. Methane therefore presents itself as a prime target for mitigation, particularly because it is the only means available to slow warming in the near term [

5,

38].

5.2. Usefulness of This Accounting

This accounting is seen as useful because it:

Offers a more comprehensive and transparent account of sectors driving climate change.

Properly values emissions from past deforestation that are not visible with conventional greenhouse inventory accounting, but which still contribute to warming.

Values current deforestation and avoided deforestation more consistently.

Provides a more transparent and less contentious means to compare emission species.

Re-focuses our attention on forests as a major climate disruptor, giving reason for optimism because deforestation is reversible.

Also, this accounting is beneficial in levelling the global north/south divide, in that developed countries deforested long ago can be compared with those experiencing active deforestation. At present, Brazil is being pressured to reduce deforestation, principally by the developed world, and as beneficial as that would be, this accounting would refocus critical attention on previously deforested nations as well as those experiencing current deforestation.

5.3. The Dangers of Aerosol Cooling

Cooling aerosols, as shown in Figure 3(a), although they are short-lived, have masked 75% of ERF from fossil fuel warming, but if cooling were to diminish, this would result in future warming. This is the ‘Faustian bargain’ [

39] that may cause additional near term warming by as much as 0.5-1.1°C if cooling emissions are reduced [

40]. Efforts to reduce aerosols due to their health impacts are proving effective [

41], threatening additional warming in coming decades [

15]. Cooling aerosols have been proposed as a geoengineering measure, however this introduces the prospect of ‘cooling credits’, that may dangerously distort carbon markets [

42]. Also, most cooling aerosols have a strong negative impact on health [

6]. The prospect of decreased aerosol cooling emphasises the urgency for quitting fossil fuels and drawing down legacy carbon.

Cooling from aerosols is highly uncertain, as shown in

Figure 1A. Estimates of fossil fuel warming at the higher end of this uncertainty range would alter sector ranking. However, this is unlikely because LULUCF CO

2 emissions presented here are highly conservative for reasons given in

section 3.3.

5.4. Policy Implications

Consistent and inclusive accounting contrasts strongly with conventional accounting, suggesting a need to further investigate novel accounting and review conventions.

This accounting re-focuses our attention on forests. Normalising and adopting gross deforestation emissions accounting would support policies aimed at reducing deforestation and preserving forests. Forest restoration may also benefit from policies informed by a greater appreciation of the role of past deforestation in causing climate change, placing emphasis on this, the most effective, lowest cost natural mitigation option [

43]. Knowing that clearing, or re-clearing in particular, re-releases an increasing proportion of fossil carbon [

2] informs policy that destruction of forest of any age could be seen in the same way as burning coal.

The greatest obstacle to large scale drawdown is finding enough land. Based on carbon deficits from Erb et.al., 2018, we find that land used for animal agriculture has a carbon deficit of about 540Gt CO

2, equivalent to the last four decades of fossil carbon emissions. When we consider carbon opportunity cost as well as methane emissions, this confirms other findings that strong controls on animal agriculture would have a transformative impact on climate change [

44].

Agriculture becomes the major disruptor of five planetary boundaries: biosphere integrity, land system change, freshwater change, biogeochemical flows [

45], and now climate change. This emphasises the need for policies to address this sector if we are to have a liveable future. Agricultural subsidies globally have been described as overwhelmingly harmful [

46]. Initiatives aimed at reducing harmful agricultural subsidies and initiatives such as the EU Green Deal are susceptible to industry influence, and misinformed and uninformed debate has enabled harmful agricultural industries to obstruct understanding and policy [

47]. This novel accounting may usefully support policy reform.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to review arguments for, and to apply accepted but unconventional advances in emissions accounting, to determine sector responsibility for present-day climate change, and to test their impact and usefulness. These results disrupt convention but appear to achieve the aim of portraying sector warming contributions more comprehensively and transparently. While there are reservations related to the inclusion of high uncertainty aerosol cooling, we believe this accounting is defensible and could be seen as overdue.

The consequences of applying consistent and inclusive accounting are extensive, suggesting a compelling need to further investigate this accounting and revisit these conventions.

These results reinforce the value of forests and identify high emission sectors, which we believe will lead to better informed mitigation actions and assist our transition to the age of drawdown.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. S1 Table: Timeseries emission data sources; S2 Table: Methodology for attribution of LULUCF carbon emissions to sectors; S3 Table: Attribution of emission species to sectors; S5 Table: Attribution of emission species proportions to sectors; References [

16,

17,

18,

22,

25,

32,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

I am also indebted to the many hundreds of dedicated climate scientists who have contributed to the data and the body of science that has enabled the current level of informed debate.

Conflicts of Interest

The author is biased against industrial scale deforestation, witnessed while monitoring deforestation for the Queensland government. This did influence the study topic, however every effort was made to make sure my personal judgement was unbiased.

References

- Ascui F, Lovell H. As frames collide. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability. 2011;24(8):978–99.

- Wedderburn-Bisshop G. Deforestation – a call for consistent carbon accounting. Environ Res Lett [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 23]; Available from: http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ad7d21. [CrossRef]

- Szopa S, Naik V, Adhikary B, Artaxo P, Berntsen T, Collins S, et al. Short-Lived Climate Forcers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press; 2021. p. 817–922.

- Houghton J, Meira Filho L, Lim B, Treanton K, Mamaty I, Bonduki Y, et al. Revised 1996 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories [Internet]. IPCC, UK Meteorological Office; 1996. Available from: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/revised-1996-ipcc-guidelines-for-national-greenhouse-gas-inventories/.

- Dreyfus GB, Xu Y, Shindell DT, Zaelke D, Ramanathan V. Mitigating climate disruption in time: A self-consistent approach for avoiding both near-term and long-term global warming. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2022 May 31;119(22):e2123536119. [CrossRef]

- Polonik P, Ricke K, Burney J. Paris Agreement’s Ambiguity About Aerosols Drives Uncertain Health and Climate Outcomes. Earth’s Future. 2021;9(5):e2020EF001787. [CrossRef]

- Davis SJ, Burney JA, Pongratz J, Caldeira K. Methods for attributing land-use emissions to products. Carbon Management. 2014 Mar 4;5(2):233–45. [CrossRef]

- Hayek MN, Harwatt H, Ripple WJ, Mueller ND. The carbon opportunity cost of animal-sourced food production on land. Nature Sustainability. 2021;1–4. [CrossRef]

- Allen M, Lynch J, Cain M, Frame DJ. Climate metrics for ruminant livestock. 2022 Jul 14 [cited 2022 Sep 13]; Available from: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2539344/programme-briefing/3561773/.

- Abernethy S, Jackson RB. Global temperature goals should determine the time horizons for greenhouse gas emission metrics. Environ Res Lett. 2022 Feb;17(2):024019. [CrossRef]

- Lee DS, Fahey DW, Skowron A, Allen MR, Burkhardt U, Chen Q, et al. The contribution of global aviation to anthropogenic climate forcing for 2000 to 2018. Atmospheric Environment. 2021 Jan 1;244:117834. [CrossRef]

- Brazzola N, Wohland J, Patt A. Offsetting unabated agricultural emissions with CO2 removal to achieve ambitious climate targets. PLOS ONE. 2021 Mar 17;16(3):e0247887. [CrossRef]

- Thornhill GD, Collins WJ, Kramer RJ, Olivié D, Skeie RB, O’Connor FM, et al. Effective radiative forcing from emissions of reactive gases and aerosols – a multi-model comparison. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2021 Jan 21;21(2):853–74. [CrossRef]

- Matthews HD, Gillett NP, Stott PA, Zickfeld K. The proportionality of global warming to cumulative carbon emissions. Nature. 2009 Jun;459(7248):829–32. [CrossRef]

- Quaas J, Jia H, Smith C, Albright AL, Aas W, Bellouin N, et al. Robust evidence for reversal of the trend in aerosol effective climate forcing. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2022 Sep 21;22(18):12221–39. [CrossRef]

- Erb KH, Kastner T, Plutzar C, Bais ALS, Carvalhais N, Fetzel T, et al. Unexpectedly large impact of forest management and grazing on global vegetation biomass. Nature. 2018 Jan;553(7686):73–6. [CrossRef]

- Smith P, Bustamante M, Ahammad H, Clark H, Dong H, Elsiddig E, et al. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU). In: IPCC AR5 WG3 Chapter 11 Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU) [Internet]. Cambridge UK and NY: Cambridge University Press,; 2014. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280076738_IPCC_AR5_WG3_Chapter_11_Agriculture_Forestry_and_Other_Land_Use_AFOLU.

- Singh C, Persson UM. Global patterns of commodity-driven deforestation and associated carbon emissions [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Apr 24]. Available from: https://eartharxiv.org/repository/view/7000/.

- Roesch CM, Ballinger AP, Schurer AP, Hegerl GC. Combining temperature and precipitation to constrain the aerosol contribution to observed climate change. Journal of Climate [Internet]. 2024 Apr 24 [cited 2024 May 1];1(aop). Available from: https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/clim/aop/JCLI-D-23-0347.1/JCLI-D-23-0347.1.xml. [CrossRef]

- Forster P, Storelvmo T, Armour K, Collins W, Dufresne JL, Frame D, et al. The Earth’s Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks, and Climate Sensitivity. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Internet]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, USA; 2021. Available from: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/chapter/chapter-7/.

- Lal R, Monger C, Nave L, Smith P. The role of soil in regulation of climate. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2021 Aug 4;376(1834):20210084.

- Friedlingstein P, O’Sullivan M, Jones MW, Andrew RM, Bakker DCE, Hauck J, et al. Global Carbon Budget 2023. Earth System Science Data. 2023 Dec 5;15(12):5301–69.

- Grassi G, Schwingshackl C, Gasser T, Houghton RA, Sitch S, Canadell JG, et al. Harmonising the land-use flux estimates of global models and national inventories for 2000–2020. Earth System Science Data. 2023 Mar 10;15(3):1093–114. [CrossRef]

- Jia G, Shevliakova E, Artaxo P, Noblet-Ducoudre N, Houghton R, House J, et al. Land–climate interactions. In: Shukla P, Skea J, Calvo Buendia E, Masson-Delmotte V, Portner H, Roberts D, et al., editors. Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems [Internet]. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; 2019. Available from: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/4/2020/08/05_Chapter-2-V3.pdf.

- Houghton RA, Castanho A. Annual emissions of carbon from land use, land-use change, and forestry from 1850 to 2020. Earth System Science Data. 2023 May 23;15(5):2025–54. [CrossRef]

- Bayer AD, Lindeskog M, Pugh TAM, Anthoni PM, Fuchs R, Arneth A. Uncertainties in the land-use flux resulting from land-use change reconstructions and gross land transitions. Earth System Dynamics. 2017 Feb 1;8:91–111. [CrossRef]

- Qin Y, Xiao X, Wigneron JP, Ciais P, Brandt M, Fan L, et al. Carbon loss from forest degradation exceeds that from deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Nat Clim Chang. 2021 May;11(5):442–8. [CrossRef]

- Winkler K, Fuchs R, Rounsevell M, Herold M. Global land use changes are four times greater than previously estimated. Nat Commun. 2021 May 11;12(1):2501. [CrossRef]

- Heinrich V, House J, Gibbs DA, Harris N, Herold M, Grassi G, et al. Mind the gap: reconciling tropical forest carbon flux estimates from earth observation and national reporting requires transparency. Carbon Balance and Management. 2023 Nov 20;18(1):22. [CrossRef]

- Gasser T, Crepin L, Quilcaille Y, Houghton RA, Ciais P, Obersteiner M. Historical CO emissions from land use and land cover change and their uncertainty. Biogeosciences. 2020 Aug 13;17(15):4075–101. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan JO, Krumhardt KM, Ellis EC, Ruddiman WF, Lemmen C, Goldewijk KK. Holocene carbon emissions as a result of anthropogenic land cover change. The Holocene. 2011 Aug 1;21(5):775–91. [CrossRef]

- van der Werf GR, Randerson JT, Giglio L, van Leeuwen TT, Chen Y, Rogers BM, et al. Global fire emissions estimates during 1997–2016. Earth System Science Data. 2017 Sep 12;9(2):697–720. [CrossRef]

- Ray DK, Sloat LL, Garcia AS, Davis KF, Ali T, Xie W. Crop harvests for direct food use insufficient to meet the UN’s food security goal. Nat Food. 2022 May;3(5):367–74. [CrossRef]

- Clark M, Springmann M, Rayner M, Scarborough P, Hill J, Tilman D, et al. Estimating the environmental impacts of 57,000 food products. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2022 Aug 16;119(33):e2120584119.

- Sato A, Nojiri Y. Assessing the contribution of harvested wood products under greenhouse gas estimation: accounting under the Paris Agreement and the potential for double-counting among the choice of approaches. Carbon Balance and Management. 2019 Nov 26;14(1):15. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse gas fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems Summary for Policymakers [Internet]. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); 2019 Aug. Available from: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2019/08/4.-SPM_Approved_Microsite_FINAL.pdf.

- Fu B, Gasser T, Li B, Tao S, Ciais P, Piao S, et al. Short-lived climate forcers have long-term climate impacts via the carbon–climate feedback. Nat Clim Chang. 2020 Sep;10(9):851–5. [CrossRef]

- Lelieveld J, Klingmüller K, Pozzer A, Burnett RT, Haines A, Ramanathan V. Effects of fossil fuel and total anthropogenic emission removal on public health and climate. PNAS. 2019 Apr 9;116(15):7192–7. [CrossRef]

- Hansen J, Kharecha P, Sato M. Climate forcing growth rates: doubling down on our Faustian bargain. Environ Res Lett. 2013 Mar;8(1):011006. [CrossRef]

- Samset BH, Sand M, Smith CJ, Bauer SE, Forster PM, Fuglestvedt JS, et al. Climate Impacts From a Removal of Anthropogenic Aerosol Emissions. Geophysical Research Letters. 2018;45(2):1020–9. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury S, Pozzer A, Haines A, Klingmüller K, Münzel T, Paasonen P, et al. Global health burden of ambient PM2.5 and the contribution of anthropogenic black carbon and organic aerosols. Environment International. 2022 Jan 15;159:107020. [CrossRef]

- Diamond MS, Wanser K, Boucher O. “Cooling credits” are not a viable climate solution. Climatic Change. 2023 Jul 4;176(7):96.

- Wilkinson K. The Drawdown Review: Climate Solutions for a New Decade [Internet]. International: Project Drawdown; 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.drawdown.org/drawdown-framework/drawdown-review-2020.

- Eisen MB, Brown PO. Rapid global phaseout of animal agriculture has the potential to stabilize greenhouse gas levels for 30 years and offset 68 percent of CO2 emissions this century. PLOS Climate. 2022 Feb 1;1(2):e0000010. [CrossRef]

- Campbell B, Beare D, Bennett E, Hall-Spencer J, Ingram J, Jaramillo F, et al. Agriculture production as a major driver of the Earth system exceeding planetary boundaries. Ecology and Society [Internet]. 2017 Oct 12 [cited 2017 Dec 13];22(4). Available from: https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol22/iss4/art8/. [CrossRef]

- Damania R, Balseca E, de Fontaunbert C, Gill J, Kim K, Rentschler J, et al. Detox Development: Repurposing Environmentally Harmful Subsidies [Internet]. Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 2023. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/61d04aca-1b95-4c06-8199-3c4a423cb7fe/content?utm_source=Plant+Based+Treaty&utm_campaign=20db4d4929-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2023_08_12_04_47&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_-20db4d4929-%5BLIST_EMAIL_ID%5D&mc_cid=20db4d4929&mc_eid=5787831cf1.

- Morris V, Jacquet J. The animal agriculture industry, US universities, and the obstruction of climate understanding and policy. Climatic Change. 2024 Feb 26;177(3):41. [CrossRef]

- Hoesly RM, Smith SJ, Feng L, Klimont Z, Janssens-Maenhout G, Pitkanen T, et al. Historical (1750–2014) anthropogenic emissions of reactive gases and aerosols from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS). Geoscientific Model Development. 2018 Jan 29;11(1):369–408. [CrossRef]

- Millington JDA, Perkins O, Smith C. Human Fire Use and Management: A Global Database of Anthropogenic Fire Impacts for Modelling. Fire. 2022 Aug;5(4):87. [CrossRef]

- Lauk C, Erb KH. Biomass consumed in anthropogenic vegetation fires: Global patterns and processes. Ecological Economics. 2009 Dec;69(2):301–9. [CrossRef]

- FAO. Forest Resource Assessment 2020 Remote Sensing Survey [Internet]. Rome: FAO; 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cb9970en.

- Stern DI, Kaufmann RK. Estimates of global anthropogenic methane emissions 1860–1993. Chemosphere. 1996 Jul 1;33(1):159–76.

- Gütschow J, Pflüger M. The PRIMAP-hist national historical emissions time series (1750-2021) v2.4.1 [Internet]. Zenodo; 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 10]. Available from: https://zenodo.org/record/7585420.

- Canadell, Monterio P, Costa M, Cotrim da Cunha L, Cox P, Eliseev A, et al., editors. Global Carbon and Other Biogeochemical Cycles and Feedbacks. In: Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Internet]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2021 [cited 2023 Jul 14]. p. 673–816. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/climate-change-2021-the-physical-science-basis/global-carbon-and-other-biogeochemical-cycles-and-feedbacks/93DFD13E855AC1F1B502965CABE28B7F.

- O’Rourke PR, Smith SJ, Mott A, Ahsan H, McDuffie EE, Crippa M, et al. CEDS v_2021_02_05 Release Emission Data [Internet]. Zenodo; 2021 [cited 2023 Jul 23]. Available from: https://zenodo.org/record/4509372.

- Andela N, Morton DC, Giglio L, Paugam R, Chen Y, Hantson S, et al. The Global Fire Atlas of individual fire size, duration, speed and direction. Earth System Science Data. 2019 Apr 24;11(2):529–52. [CrossRef]

- Sankaran M, Hanan NP, Scholes RJ, Ratnam J, Augustine DJ, Cade BS, et al. Determinants of woody cover in African savannas. Nature. 2005 Dec 8;438(7069):846–9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).