Submitted:

30 October 2023

Posted:

30 October 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Cerebellar function: a new perspective

Cerebellar anatomy

Scope

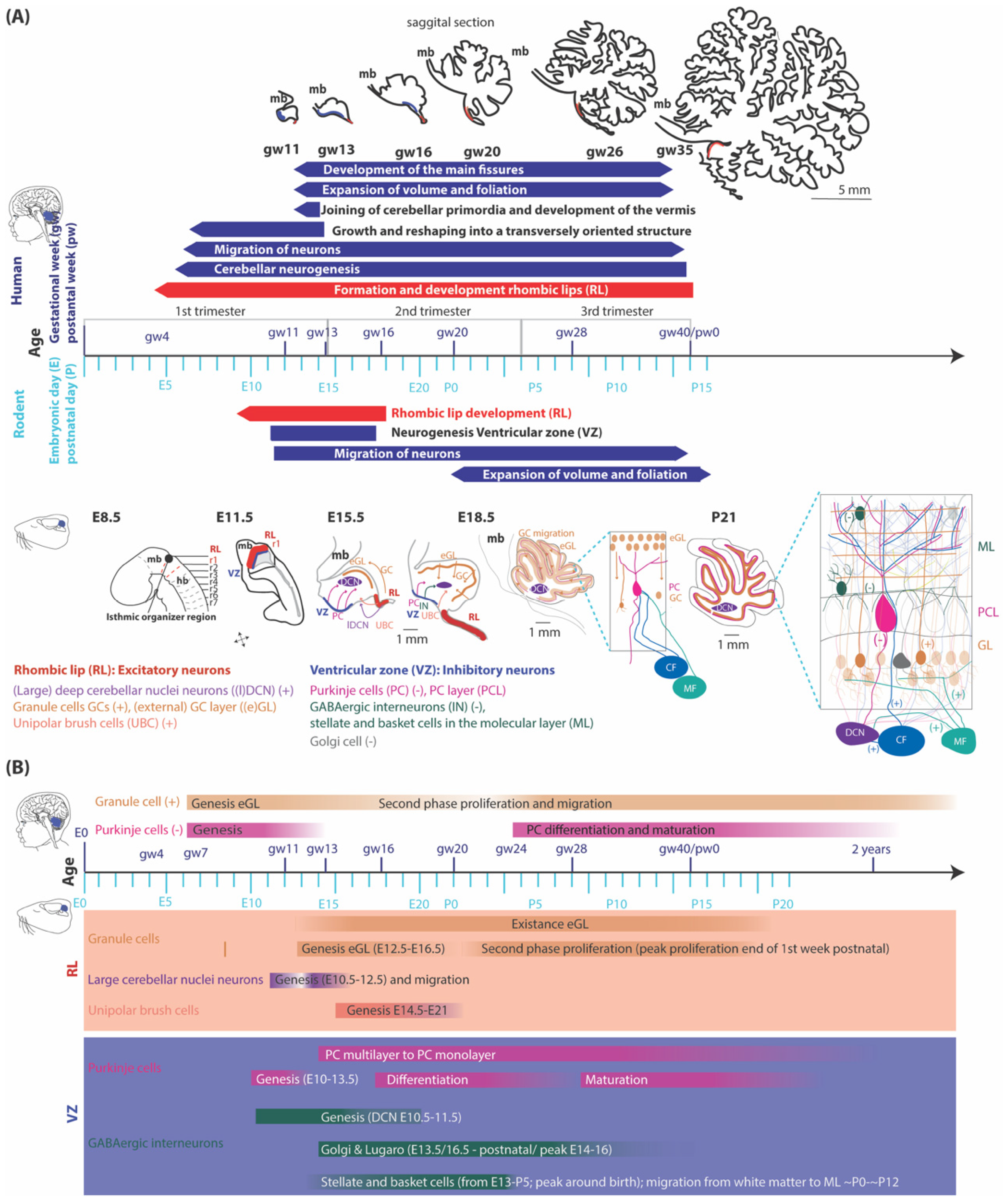

Embryology of the cerebellum

Glutamatergic neuron development

GABAergic neuron development

Embryology of the precerebellar system

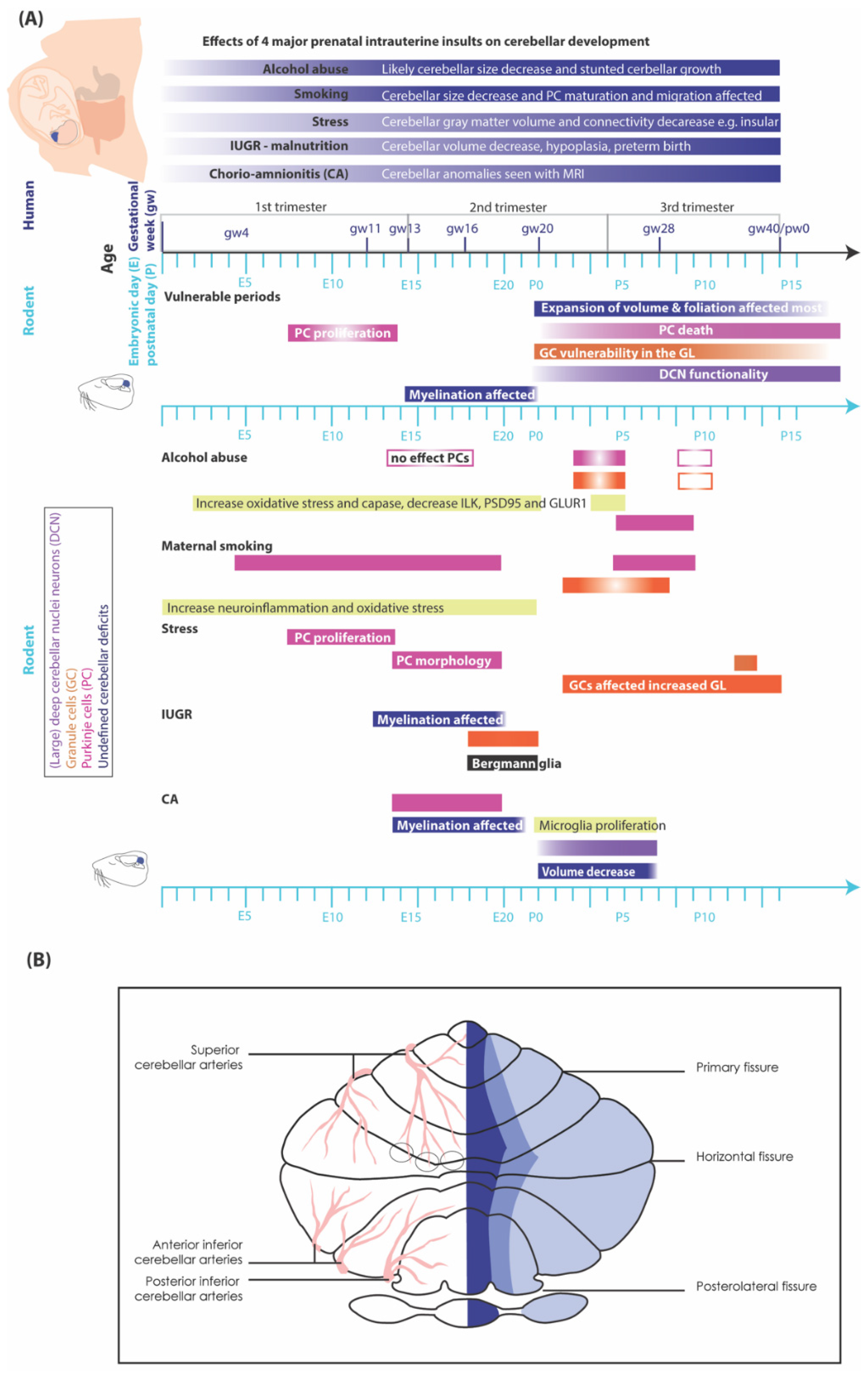

Extrinsic Deterrents Influencing Cerebellar Development

Maternal substance abuse

Impact of smoking and nicotine exposure on cerebellar maturation

E-cigarettes

Stress and sleep

Impact of stress

Possible impact of sleep deprivation

Intra-uterine growth restriction (IUGR)

Infections

Critical periods in cerebellar development affected by insults

First trimester (until week 13 human, until E12/13 rodents)

Second trimester (week 13-26 human, E13-birth rodents)

Third trimester (week 27-40 human)

Two weeks postnatal rodents

Differences in how intra-uterine and postnatal insults affect cerebellar regions

References

- Dietrich, K.N.; Eskenazi, B.; Schantz, S.; Yolton, K.; Rauh, V.A.; Johnson, C.B.; Alkon, A.; Canfield, R.L.; Pessah, I.N.; Berman, R.F. Principles and Practices of Neurodevelopmental Assessment in Children: Lessons Learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect 2005, 113, 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koning, I. V.; Dudink, J.; Groenenberg, I.A.L.; Willemsen, S.P.; Reiss, I.K.M.; Steegers-Theunissen, R.P.M. Prenatal Cerebellar Growth Trajectories and the Impact of Periconceptional Maternal and Fetal Factors. Hum Reprod 2017, 32, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwaniki, M.K.; Atieno, M.; Lawn, J.E.; Newton, C.R. Long-Term Neurodevelopmental Outcomes after Intrauterine and Neonatal Insults: A Systematic Review. The Lancet 2012, 379, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, K.J.; Meaney, M.J. Fetal Origins of Mental Health: The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease Hypothesis. American Journal of Psychiatry 2017, 174, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Essen, M.J.; Nayler, S.; Becker, E.B.E.; Jacob, J. Deconstructing Cerebellar Development Cell by Cell. PLoS Genet 2020, 16, e1008630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koning, I.V.; Tielemans, M.J.; Hoebeek, F.E.; Ecury-Goossen, G.M.; Reiss, I.K.M.; Steegers-Theunissen, R.P.M.; Dudink, J. Impacts on Prenatal Development of the Human Cerebellum: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 2017, 30, 2461–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badura, A.; Verpeut, J.L.; Metzger, J.W.; Pereira, T.D.; Pisano, T.J.; Deverett, B.; Bakshinskaya, D.E.; Wang, S.S.-H. Normal Cognitive and Social Development Require Posterior Cerebellar Activity. Elife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruchhage, M.M.K.; Bucci, M.-P.; Becker, E.B.E. Cerebellar Involvement in Autism and ADHD. Handb Clin Neurol 2018, 155, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathyanesan, A.; Zhou, J.; Scafidi, J.; Heck, D.H.; Sillitoe, R. V.; Gallo, V. Emerging Connections between Cerebellar Development, Behaviour and Complex Brain Disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 2019, 20, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herculano-Houzel, S. The Human Brain in Numbers: A Linearly Scaled-up Primate Brain. Front Hum Neurosci 2009, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. G. B. The Works of Aristotle. Translated into English under the Editorship of J. A.; Smith, M.A., and W. D. Ross, M.A. Vol. VIII. Metaphysica , by W. D. Ross. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1908. 8vo. Classical Rev 1909, 23, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manto, M.; Bower, J.M.; Conforto, A.B.; Delgado-García, J.M.; da Guarda, S.N.F.; Gerwig, M.; Habas, C.; Hagura, N.; Ivry, R.B.; Mariën, P.; et al. Consensus Paper: Roles of the Cerebellum in Motor Control—The Diversity of Ideas on Cerebellar Involvement in Movement. The Cerebellum 2012, 11, 457–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmahmann, J.D. Dysmetria of Thought: Clinical Consequences of Cerebellar Dysfunction on Cognition and Affect. Trends Cogn Sci 1998, 2, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.S.-H.; Kloth, A.D.; Badura, A. The Cerebellum, Sensitive Periods, and Autism. Neuron 2014, 83, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apps, R.; Hawkes, R. Cerebellar Cortical Organization: A One-Map Hypothesis. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009, 10, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grodd, W.; Hülsmann, E.; Lotze, M.; Wildgruber, D.; Erb, M. Sensorimotor Mapping of the Human Cerebellum: FMRI Evidence of Somatotopic Organization. Hum Brain Mapp 2001, 13, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, R.M.; Strick, P.L. Cerebellar Loops with Motor Cortex and Prefrontal Cortex of a Nonhuman Primate. J Neurosci 2003, 23, 8432–8444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmahmann, J.D. The Cerebellum and Cognition. Neurosci Lett 2019, 688, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kansal, K.; Yang, Z.; Fishman, A.M.; Sair, H.I.; Ying, S.H.; Jedynak, B.M.; Prince, J.L.; Onyike, C.U. Structural Cerebellar Correlates of Cognitive and Motor Dysfunctions in Cerebellar Degeneration. Brain 2017, 140, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochu, G.; Maler, L.; Hawkes, R. Zebrin II: A Polypeptide Antigen Expressed Selectively by Purkinje Cells Reveals Compartments in Rat and Fish Cerebellum. J Comp Neurol 1990, 291, 538–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, C.L.; Krueger-Naug, A.M.; Currie, R.W.; Hawkes, R. Constitutive Expression of the 25-KDa Heat Shock Protein Hsp25 Reveals Novel Parasagittal Bands of Purkinje Cells in the Adult Mouse Cerebellar Cortex. J Comp Neurol 2000, 416, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashizume, M.; Miyazaki, T.; Sakimura, K.; Watanabe, M.; Kitamura, K.; Kano, M. Disruption of Cerebellar Microzonal Organization in GluD2 (GluRδ2) Knockout Mouse. Front Neural Circuits 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarna, J.R.; Marzban, H.; Watanabe, M.; Hawkes, R. Complementary Stripes of Phospholipase Cbeta3 and Cbeta4 Expression by Purkinje Cell Subsets in the Mouse Cerebellum. J Comp Neurol 2006, 496, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, C.; Hawkes, R. Zones and Stripes. In Essentials of Cerebellum and Cerebellar Disorders A Primer For Graduate Students Second Edition; 2023; pp. 99–106.

- Ament, S.A.; Cortes-Gutierrez, M.; Herb, B.R.; Mocci, E.; Colantuoni, C.; McCarthy, M.M. A Single-Cell Genomic Atlas for Maturation of the Human Cerebellum during Early Childhood. Sci Transl Med 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Lin, Z.; Voges, K.; Ju, C.; Gao, Z.; Bosman, L.W.; Ruigrok, T.J.; Hoebeek, F.E.; De Zeeuw, C.I.; Schonewille, M. Cerebellar Modules Operate at Different Frequencies. Elife 2014, 3, e02536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Zeeuw, C.I. Bidirectional Learning in Upbound and Downbound Microzones of the Cerebellum. Nat Rev Neurosci 2021, 22, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Novello, M.; Gao, Z.; Ruigrok, T.J.H.; De Zeeuw, C.I. Input and Output Organization of the Mesodiencephalic Junction for Cerebro-cerebellar Communication. J Neurosci Res 2022, 100, 620–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Zeeuw, C.I.; Hoebeek, F.E.; Bosman, L.W.J.; Schonewille, M.; Witter, L.; Koekkoek, S.K. Spatiotemporal Firing Patterns in the Cerebellum. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011, 12, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, W. Cell Number and Cell Density in the Cerebellar Cortex of Man and Some Other Mammals. Cell Tissue Res 1975, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Y. Signaling Pathways in Cerebellar Granule Cells Development. Am J Stem Cells 2019, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haldipur, P.; Millen, K.J.; Aldinger, K.A. Human Cerebellar Development and Transcriptomics: Implications for Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci 2022, 45, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leto, K.; Arancillo, M.; Becker, E.B.E.; Buffo, A.; Chiang, C.; Ding, B.; Dobyns, W.B.; Dusart, I.; Haldipur, P.; Hatten, M.E.; et al. Consensus Paper: Cerebellar Development. Cerebellum 2015, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carletti, B.; Rossi, F. Neurogenesis in the Cerebellum. Neuroscientist 2008, 14, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, B.; Mangold, U.; Sievers, J.; Berry, M. Derivation of Cerebellar Golgi Neurons from the External Granular Layer: Evidence from Explantation of External Granule Cells in Vivo. J Comp Neurol 1985, 232, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldipur, P.; Bharti, U.; Alberti, C.; Sarkar, C.; Gulati, G.; Iyengar, S.; Gressens, P.; Mani, S. Preterm Delivery Disrupts the Developmental Program of the Cerebellum. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koning, I. V.; Tielemans, M.J.; Hoebeek, F.E.; Ecury-Goossen, G.M.; Reiss, I.K.M.; Steegers-Theunissen, R.P.M.; Dudink, J. Impacts on Prenatal Development of the Human Cerebellum: A Systematic Review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2017, 30, 2461–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Workman, A.D.; Charvet, C.J.; Clancy, B.; Darlington, R.B.; Finlay, B.L. Modeling Transformations of Neurodevelopmental Sequences across Mammalian Species. The Journal of Neuroscience 2013, 33, 7368–7383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldipur, P.; Aldinger, K.A.; Bernardo, S.; Deng, M.; Timms, A.E.; Overman, L.M.; Winter, C.; Lisgo, S.N.; Razavi, F.; Silvestri, E.; et al. Spatiotemporal Expansion of Primary Progenitor Zones in the Developing Human Cerebellum. Science (1979) 2019. under emba. [Google Scholar]

- Haldipur, P.; Dang, D.; Millen, K.J. Embryology. Handb Clin Neurol 2018, 154, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukic, A.M.; Baird, D.D.; Weinberg, C.R.; McConnaughey, D.R.; Wilcox, A.J. Length of Human Pregnancy and Contributors to Its Natural Variation. Hum Reprod 2013, 28, 2848–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.M.; Mukherjee, S.; Wilburn, A.N.; Cates, C.; Lewkowich, I.P.; Deshmukh, H.; Zacharias, W.J.; Chougnet, C.A. Pulmonary Consequences of Prenatal Inflammatory Exposures: Clinical Perspective and Review of Basic Immunological Mechanisms. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappelletti, M.; Presicce, P.; Kallapur, S.G. Immunobiology of Acute Chorioamnionitis. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semple, B.D.; Blomgren, K.; Gimlin, K.; Ferriero, D.M.; Noble-Haeusslein, L.J. Brain Development in Rodents and Humans: Identifying Benchmarks of Maturation and Vulnerability to Injury across Species. Prog Neurobiol 2013, 106–107, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldipur, P.; Aldinger, K.A.; Bernardo, S.; Deng, M.; Timms, A.E.; Overman, L.M.; Winter, C.; Lisgo, S.N.; Razavi, F.; Silvestri, E.; et al. Spatiotemporal Expansion of Primary Progenitor Zones in the Developing Human Cerebellum. Science (1979) 2019. under emba. [Google Scholar]

- Limperopoulos, C.; Soul, J.S.; Haidar, H.; Huppi, P.S.; Bassan, H.; Warfield, S.K.; Robertson, R.L.; Moore, M.; Akins, P.; Volpe, J.J.; et al. Impaired Trophic Interactions Between the Cerebellum and the Cerebrum Among Preterm Infants. Pediatrics 2005, 116, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accogli, A.; Addour-Boudrahem, N.; Srour, M. Diagnostic Approach to Cerebellar Hypoplasia. The Cerebellum 2021, 20, 631–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldinger, K.A.; Thomson, Z.; Phelps, I.G.; Haldipur, P.; Deng, M.; Timms, A.E.; Hirano, M.; Santpere, G.; Roco, C.; Rosenberg, A.B.; et al. Spatial and Cell Type Transcriptional Landscape of Human Cerebellar Development. Nat Neurosci 2021, 24, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Joyner, A.L. Otx2 and Gbx2 Are Required for Refinement and Not Induction of Mid-Hindbrain Gene Expression. Development 2001, 128, 4979–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckinghausen, J.; Sillitoe, R.V. Insights into Cerebellar Development and Connectivity. Neurosci Lett 2019, 688, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingate, R.J.T. The Rhombic Lip and Early Cerebellar Development. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2001, 11, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millet, S.; Campbell, K.; Epstein, D.J.; Losos, K.; Harris, E.; Joyner, A.L. A Role for Gbx2 in Repression of Otx2 and Positioning the Mid/Hindbrain Organizer. Nature 1999, 401, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broccoli, V.; Boncinelli, E.; Wurst, W. The Caudal Limit of Otx2 Expression Positions the Isthmic Organizer. Nature 1999, 401, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chizhikov, V.V.; Lindgren, A.G.; Mishima, Y.; Roberts, R.W.; Aldinger, K.A.; Miesegaes, G.R.; Currle, D.S.; Monuki, E.S.; Millen, K.J. Lmx1a Regulates Fates and Location of Cells Originating from the Cerebellar Rhombic Lip and Telencephalic Cortical Hem. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 10725–10730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrales, J.D.; Rocco, G.L.; Blaess, S.; Guo, Q.; Joyner, A.L. Spatial Pattern of Sonic Hedgehog Signaling through Gli Genes during Cerebellum Development. Development 2004, 131, 5581–5590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belzunce, I.; Belmonte-Mateos, C.; Pujades, C. The Interplay of Atoh1 Genes in the Lower Rhombic Lip during Hindbrain Morphogenesis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, C.R.; Seshadri, S.; Destefano, A.L.; Fornage, M.; Arnold, C.R.; Gage, P.J.; Skarie, J.M.; Dobyns, W.B.; Millen, K.J.; Liu, T.; et al. Mutation of FOXC1 and PITX2 Induces Cerebral Small-Vessel Disease. J Clin Invest 2014, 124, 4877–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldinger, K.A.; Lehmann, O.J.; Hudgins, L.; Chizhikov, V. V.; Bassuk, A.G.; Ades, L.C.; Krantz, I.D.; Dobyns, W.B.; Millen, K.J. FOXC1 Is Required for Normal Cerebellar Development and Is a Major Contributor to Chromosome 6p25.3 Dandy-Walker Malformation. Nat Genet 2009, 41, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldinger, K.A.; Timms, A.E.; Thomson, Z.; Mirzaa, G.M.; Bennett, J.T.; Rosenberg, A.B.; Roco, C.M.; Hirano, M.; Abidi, F.; Haldipur, P.; et al. Redefining the Etiologic Landscape of Cerebellar Malformations. Am J Hum Genet 2019, 105, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.R.; Musci, T.S.; Neumann, P.E.; Capecchi, M.R. Swaying Is a Mutant Allele of the Proto-Oncogene Wnt-1. Cell 1991, 67, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akazawa, C.; Ishibashi, M.; Shimizu, C.; Nakanishi, S.; Kageyama, R. A Mammalian Helix-Loop-Helix Factor Structurally Related to the Product of Drosophila Proneural Gene Atonal Is a Positive Transcriptional Regulator Expressed in the Developing Nervous System. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1995, 270, 8730–8738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshino, M.; Nakamura, S.; Mori, K.; Kawauchi, T.; Terao, M.; Nishimura, Y.V.; Fukuda, A.; Fuse, T.; Matsuo, N.; Sone, M.; et al. Ptf1a, a BHLH Transcriptional Gene, Defines GABAergic Neuronal Fates in Cerebellum. Neuron 2005, 47, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machold, R.; Fishell, G. Math1 Is Expressed in Temporally Discrete Pools of Cerebellar Rhombic-Lip Neural Progenitors. Neuron 2005, 48, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekerková, G.; Ilijic, E.; Mugnaini, E. Time of Origin of Unipolar Brush Cells in the Rat Cerebellum as Observed by Prenatal Bromodeoxyuridine Labeling. Neuroscience 2004, 127, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consalez, G.G.; Goldowitz, D.; Casoni, F.; Hawkes, R. Origins, Development, and Compartmentation of the Granule Cells of the Cerebellum. Front Neural Circuits 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chizhikov, V.; Millen, K.J. Development and Malformations of the Cerebellum in Mice. Mol Genet Metab 2003, 80, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komuro, H.; Yacubova, E.; Yacubova, E.; Rakic, P. Mode and Tempo of Tangential Cell Migration in the Cerebellar External Granular Layer. The Journal of Neuroscience 2001, 21, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helms, A.W.; Gowan, K.; Abney, A.; Savage, T.; Johnson, J.E. Overexpression of MATH1 Disrupts the Coordination of Neural Differentiation in Cerebellum Development. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 2001, 17, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wizeman, J.W.; Guo, Q.; Wilion, E.M.; Li, J.Y. Specification of Diverse Cell Types during Early Neurogenesis of the Mouse Cerebellum. Elife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zordan, P.; Croci, L.; Hawkes, R.; Consalez, G.G. Comparative Analysis of Proneural Gene Expression in the Embryonic Cerebellum. Developmental Dynamics 2008, 237, 1726–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miterko, L.N.; Sillitoe, R.V.; Hawkes, R. Zones and Stripes: Development of Cerebellar Topography. In Handbook of the Cerebellum and Cerebellar Disorders: Second Edition: Volume 3; 2021; Vol. 3.

- Sheldon, M.; Rice, D.S.; D’Arcangelo, G.; Yoneshima, H.; Nakajima, K.; Mikoshiba, K.; Howell, B.W.; Cooper, J.A.; Goldowitz, D.; Curran, T. Scrambler and Yotari Disrupt the Disabled Gene and Produce a Reeler -like Phenotype in Mice. Nature 1997, 389, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, B.W.; Hawkes, R.; Soriano, P.; Cooper, J.A. Neuronal Position in the Developing Brain Is Regulated by Mouse Disabled-1. Nature 1997, 389, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arcangelo, G.; G. Miao, G.; Chen, S.-C.; Scares, H.D.; Morgan, J.I.; Curran, T. A Protein Related to Extracellular Matrix Proteins Deleted in the Mouse Mutant Reeler. Nature 1995, 374, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.-H.; Marzban, H.; Croci, L.; Consalez, G.G.; Hawkes, R. Purkinje Cell Subtype Specification in the Cerebellar Cortex: Early B-Cell Factor 2 Acts to Repress the Zebrin II-Positive Purkinje Cell Phenotype. Neuroscience 2008, 153, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heijden, M.E.; Lackey, E.P.; Perez, R.; Ișleyen, F.S.; Brown, A.M.; Donofrio, S.G.; Lin, T.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Sillitoe, R. V Maturation of Purkinje Cell Firing Properties Relies on Neurogenesis of Excitatory Neurons. Elife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, B.E.; Turner, R.W. Physiological and Morphological Development of the Rat Cerebellar Purkinje Cell. J Physiol 2005, 567, 829–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beekhof, G.C.; Schonewille, M. Lobule-Related Action Potential Shape- and History-Dependent Current Integration in Purkinje Cells of Adult and Developing Mice. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapfhammer, J.P. Cellular and Molecular Control of Dendritic Growth and Development of Cerebellar Purkinje Cells. Prog Histochem Cytochem 2004, 39, 131–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarna, J.R.; Hawkes, R. Patterned Purkinje Cell Death in the Cerebellum. Prog Neurobiol 2003, 70, 473–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, S.E.; Hansel, C. Climbing Fiber Multi-Innervation of Mouse Purkinje Dendrites with Arborization Common to Human. Science (1979) 2023, 381, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, F.; Czubayko, U.; Thier, P. Morphological Classification of the Rat Lateral Cerebellar Nuclear Neurons by Principal Component Analysis. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2003, 455, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leto, K.; Carletti, B.; Williams, I.M.; Magrassi, L.; Rossi, F. Different Types of Cerebellar GABAergic Interneurons Originate from a Common Pool of Multipotent Progenitor Cells. The Journal of Neuroscience 2006, 26, 11682–11694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leto, K.; Bartolini, A.; Yanagawa, Y.; Obata, K.; Magrassi, L.; Schilling, K.; Rossi, F. Laminar Fate and Phenotype Specification of Cerebellar GABAergic Interneurons. The Journal of Neuroscience 2009, 29, 7079–7091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimaldi, P.; Parras, C.; Guillemot, F.; Rossi, F.; Wassef, M. Origins and Control of the Differentiation of Inhibitory Interneurons and Glia in the Cerebellum. Dev Biol 2009, 328, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chedotal, A.; Sotelo, C. Early Development of Olivocerebellar Projections in the Fetal Rat Using CGRP Immunocytochemistry. European Journal of Neuroscience 1992, 4, 1159–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugihara, I. Microzonal Projection and Climbing Fiber Remodeling in Single Olivocerebellar Axons of Newborn Rats at Postnatal Days 4–7. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2005, 487, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, C.I.; Dymecki, S.M. Origin of the Precerebellar System. Neuron 2000, 27, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.; Park, H.; Tanaka-Yamamoto, K.; Yamamoto, Y. Developmental Timing-Dependent Organization of Synaptic Connections between Mossy Fibers and Granule Cells in the Cerebellum. Commun Biol 2023, 6, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodlett, C.R.; Marcussen, L.; West, J.R. A Single Day of Alcohol Exposure During the Brain Growth Spurt Induces Brain Weight Restriction and Cerebellar Purkinje Cell Loss. Alcohol 1989, 7, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, M.E.; Lyoo, I.K.; Streeter, C.C.; Covell, J.; Sarid-Segal, O.; Ciraulo, D.A.; Kim, M.J.; Kaufman, M.J.; Yurgelun-Todd, D.A.; Renshaw, P.F. Cerebellar Gray Matter Volume Correlates with Duration of Cocaine Use in Cocaine-Dependent Subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007, 32, 2229–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manto, M.; Perrotta, G. Toxic-Induced Cerebellar Syndrome: From the Fetal Period to the Elderly. In; 2018; pp. 333–352.

- Dow-Edwards, D.L.; Benveniste, H.; Behnke, M.; Bandstra, E.S.; Singer, L.T.; Hurd, Y.L.; Stanford, L.R. Neuroimaging of Prenatal Drug Exposure. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2006, 28, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, L.; Nordberg, A.; Seiger, Å.; Kjældgaard, A.; Hellström-Lindahl, E. Smoking during Early Pregnancy Affects the Expression Pattern of Both Nicotinic and Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Human First Trimester Brainstem and Cerebellum. Neuroscience 2005, 132, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavezzi, A.M.; Corna, M.F.; Repetti, M.L.; Matturri, L. Cerebellar Purkinje Cell Vulnerability to Prenatal Nicotine Exposure in Sudden Unexplained Perinatal Death. Folia Neuropathol 2013, 4, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosdin, L.K.; Deputy, N.P.; Kim, S.Y.; Dang, E.P.; Denny, C.H. Alcohol Consumption and Binge Drinking During Pregnancy Among Adults Aged 18–49 Years — United States, 2018–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022, 71, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dukes, K.; Tripp, T.; Willinger, M.; Odendaal, H.; Elliott, A.J.; Kinney, H.C.; Robinson, F.; Petersen, J.M.; Raffo, C.; Hereld, D.; et al. Drinking and Smoking Patterns during Pregnancy: Development of Group-Based Trajectories in the Safe Passage Study. Alcohol 2017, 62, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handmaker, N.S.; Rayburn, W.F.; Meng, C.; Bell, J.B.; Rayburn, B.B.; Rappaport, V.J. Impact of Alcohol Exposure After Pregnancy Recognition on Ultrasonographic Fetal Growth Measures. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2006, 30, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astley, S.J.; Aylward, E.H.; Olson, H.C.; Kerns, K.; Brooks, A.; Coggins, T.E.; Davies, J.; Dorn, S.; Gendler, B.; Jirikowic, T.; et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Outcomes From a Comprehensive Magnetic Resonance Study of Children With Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009, 33, 1671–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, A.L.; Crocker, N.; Mattson, S.N.; Riley, E.P. Neuroimaging and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Dev Disabil Res Rev 2009, 15, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J. Acute and Long-Term Changes in the Cerebellum Following Developmental Exposure to Ethanol. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl. 1993, 2, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sowell, E.R.; Jernigan, T.L.; Mattson, S.N.; Riley, E.P.; Sobel, D.F.; Jones, K.L. Abnormal Development of the Cerebellar Vermis in Children Prenatally Exposed to Alcohol: Size Reduction in Lobules I-V. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1996, 20, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattson, S.N.; Riley, E.P.; Jernigan, T.L.; Garcia, A.; Kaneko, W.M.; Ehlers, C.L.; Jones, K.L. A Decrease in the Size of the Basal Ganglia in Children with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Neurotoxicol Teratol 1994, 16, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kfir, M.; Yevtushok, L.; Onishchenko, S.; Wertelecki, W.; Bakhireva, L.; Chambers, C.D.; Jones, K.L.; Hull, A.D. Can Prenatal Ultrasound Detect the Effects of In-utero Alcohol Exposure? A Pilot Study. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2009, 33, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autti-Rämö, I.; Autti, T.; Korkman, M.; Kettunen, S.; Salonen, O.; Valanne, L. MRI Findings in Children with School Problems Who Had Been Exposed Prenatally to Alcohol. Dev Med Child Neurol 2002, 44, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, E.P.; McGee, C.L. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: An Overview with Emphasis on Changes in Brain and Behavior. Exp Biol Med 2005, 230, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaatinen, P.; Rintala, J. Mechanisms of Ethanol-Induced Degeneration in the Developing, Mature, and Aging Cerebellum. Cerebellum 2008, 7, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hare, E.D.; Kan, E.; Yoshii, J.; Mattson, S.N.; Riley, E.P.; Thompson, P.M.; Toga, A.W.; Sowell, E.R. Mapping Cerebellar Vermal Morphology and Cognitive Correlates in Prenatal Alcohol Exposure. Neuroreport 2005, 16, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kfir, M.; Yevtushok, L.; Onishchenko, S.; Wertelecki, W.; Bakhireva, L.; Chambers, C.D.; Jones, K.L.; Hull, A.D. Can Prenatal Ultrasound Detect the Effects of In-utero Alcohol Exposure? A Pilot Study. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2009, 33, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handmaker, N.S.; Rayburn, W.F.; Meng, C.; Bell, J.B.; Rayburn, B.B.; Rappaport, V.J. Impact of Alcohol Exposure After Pregnancy Recognition on Ultrasonographic Fetal Growth Measures. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2006, 30, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.-J.A.; Parnell, S.E.; West, J.R.; Chen, W.-J.A.; Parnell, S.E.; Neonatal, J.R.W. Neonatal Alcohol and Nicotine Exposure Limits Brain Growth and Depletes Cerebellar Purkinje Cells; 1998; Vol. 15;

- Karaçay, B.; Li, S.; Bonthius, D.J. Maturation-Dependent Alcohol Resistance in the Developing Mouse: Cerebellar Neuronal Loss and Gene Expression during Alcohol-Vulnerable and -Resistant Periods. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2008, 32, 1439–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Rowe, J.; Eskue, K.; West, J.R.; Maier, S.E. Alcohol Exposure on Postnatal Day 5 Induces Purkinje Cell Loss and Evidence of Purkinje Cell Degradation in Lobule I of Rat Cerebellum. Alcohol 2008, 42, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topper, L.A.; Baculis, B.C.; Valenzuela, C.F. Exposure of Neonatal Rats to Alcohol Has Differential Effects on Neuroinflammation and Neuronal Survival in the Cerebellum and Hippocampus. J Neuroinflammation 2015, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodlett, C.R.; Eilers, A.T. Alcohol-Induced Purkinje Cell Loss with a Single Binge Exposure in Neonatal Rats: A Stereological Study of Temporal Windows of Vulnerability. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1997, 21, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcussen, B.L.; Goodlett, C.R.; Mahoney$, J.C.; West$, J.R.; Marcussen, B.L.; Goodlett, C.R.; Mahoney, J.C. Developing Rat Purkinje Cells Are More Vulnerable to Alcohol-Induced Depletion During Differentiation Than During Neurogenesis. Alcohol 1994, 11, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, D.; Majrashi, M.; Ramesh, S.; Govindarajulu, M.; Bloemer, J.; Fujihashi, A.; Crump, B.R.; Hightower, H.; Bhattacharya, S.; Moore, T.; et al. Assessment of the Cerebellar Neurotoxic Effects of Nicotine in Prenatal Alcohol Exposure in Rats. Life Sci 2018, 194, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavezzi, A.M.; Corna, M.F.; Repetti, M.L.; Matturri, L. Cerebellar Purkinje Cell Vulnerability to Prenatal Nicotine Exposure in Sudden Unexplained Perinatal Death. Folia Neuropathol 2013, 4, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, L.; Nordberg, A.; Seiger, Å.; Kjældgaard, A.; Hellström-Lindahl, E. Smoking during Early Pregnancy Affects the Expression Pattern of Both Nicotinic and Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Human First Trimester Brainstem and Cerebellum. Neuroscience 2005, 132, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekblad, M.; Korkeila, J.; Parkkola, R.; Lapinleimu, H.; Haataja, L.; Lehtonen, L. Maternal Smoking during Pregnancy and Regional Brain Volumes in Preterm Infants. Journal of Pediatrics 2010, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekblad, M.O. Association of Smoking During Pregnancy With Compromised Brain Development in Offspring. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2224714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, N.R.; Day, K.D.; Payakachat, N.; Franks, A.M.; McCain, K.R.; Ragland, D. Use and Risk Perception of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems and Tobacco in Pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues 2018, 28, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroud, L.R.; Papandonatos, G.D.; Borba, K.; Kehoe, T.; Scott-Sheldon, L.A.J. Flavored Electronic Cigarette Use, Preferences, and Perceptions in Pregnant Mothers: A Correspondence Analysis Approach. Addictive Behaviors 2019, 91, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BANERJEE, S.; DEACON, A.; SUTER, M.A.; AAGAARD, K.M. Understanding the Placental Biology of Tobacco Smoke, Nicotine, and Marijuana (THC) Exposures During Pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2022, 65, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.W.; Lee, S.M.; Ko, E.B.; Go, R.E.; Jeung, E.B.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, K.C. Inhibitory Effects of Cigarette Smoke Extracts on Neural Differentiation of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells. Reproductive Toxicology 2020, 95, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Rahman, A.; Dechkovskaia, A.M.; Sutton, J.M.; Chen, W.C.; Guan, X.; Khan, W.A.; Abou-Donia, M.B. Maternal Exposure of Rats to Nicotine via Infusion during Gestation Produces Neurobehavioral Deficits and Elevated Expression of Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein in the Cerebellum and CA1 Subfield in the Offspring at Puberty. Toxicology 2005, 209, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Donia, M.B.; Khan, W.A.; Dechkovskaia, A.M.; Goldstein, L.B.; Bullman, S.L.; Abdel-Rahman, A. In Utero Exposure to Nicotine and Chlorpyrifos Alone, and in Combination Produces Persistent Sensorimotor Deficits and Purkinje Neuron Loss in the Cerebellum of Adult Offspring Rats. Arch Toxicol 2006, 80, 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, Y.L.; Saad, S.; Pollock, C.; Oliver, B.; Al-Odat, I.; Zaky, A.A.; Jones, N.; Chen, H. Impact of Maternal Cigarette Smoke Exposure on Brain Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Male Mice Offspring. Sci Rep 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.Z.; Abbott, L.C.; Winzer-Serhan, U.H. Effects of Chronic Neonatal Nicotine Exposure on Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Binding, Cell Death and Morphology in Hippocampus and Cerebellum. Neuroscience 2007, 146, 1854–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Church, J.S.; Chace-Donahue, F.; Blum, J.L.; Ratner, J.R.; Zelikoff, J.T.; Schwartzer, J.J. Neuroinflammatory and Behavioral Outcomes Measured in Adult Offspring of Mice Exposed Prenatally to E-Cigarette Aerosols. Environ Health Perspect 2020, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupien, S.J.; McEwen, B.S.; Gunnar, M.R.; Heim, C. Effects of Stress throughout the Lifespan on the Brain, Behaviour and Cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009, 10, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, B.; Letourneau, N.; Lebel, C. Prenatal Maternal Anxiety and Children’s Brain Structure and Function: A Systematic Review of Neuroimaging Studies. J Affect Disord 2018, 241, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, B.; Letourneau, N.; Lebel, C. Prenatal Maternal Anxiety and Children’s Brain Structure and Function: A Systematic Review of Neuroimaging Studies. J Affect Disord 2018, 241, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkel Schetter, C.; Tanner, L. Anxiety, Depression and Stress in Pregnancy. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012, 25, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, C.; Davis, E.P.; Muftuler, L.T.; Head, K.; Sandman, C.A. High Pregnancy Anxiety during Mid-Gestation Is Associated with Decreased Gray Matter Density in 6–9-Year-Old Children. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010, 35, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulupinar, E.; Yucel, F. Prenatal Stress Reduces Interneuronal Connectivity in the Rat Cerebellar Granular Layer. In Proceedings of the Neurotoxicology and Teratology; May 2005; Vol. 27; pp. 475–484. [Google Scholar]

- Ulupinar, E.; Yucel, F.; Ortug, G. The Effects of Prenatal Stress on the Purkinje Cell Neurogenesis. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2006, 28, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, R.; Ebner, D.; Araneda, R.; Urqueta, M.J.; Bustamante, C. Maternal Stress Induces Long-Lasting Purkinje Cell Developmental Impairments in Mouse Offspring. Eur J Pediatr 2010, 169, 1517–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, R.; Valencia, M.; Bustamante, C. Purkinje Cell Dendritic Atrophy Induced by Prenatal Stress Is Mitigated by Early Environmental Enrichment. Neuropediatrics 2015, 46, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, R.; Santander, O.; Cuevas, I.; Valencia, M. Prenatal Glucocorticoid Administration Persistently Increased the Immunohistochemical Expression of Type-1 Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor and Purkinje Cell Dendritic Growth in the Cerebellar Cortex of the Rat. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2017, 58, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilber, A.A.; Lin, G.L.; Wellman, C.L. Neonatal Corticosterone Administration Impairs Adult Eyeblink Conditioning and Decreases Glucocorticoid Receptor Expression in the Cerebellar Interpositus Nucleus. Neuroscience 2011, 177, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, E.R.; Civillico, E.F.; Wang, S.S.-H. Calcium-Based Dendritic Excitability and Its Regulation in the Deep Cerebellar Nuclei. J Neurophysiol 2013, 109, 2282–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roque, A.; Lajud, N.; Valdez, J.J.; Torner, L. Early-Life Stress Increases Granule Cell Density in the Cerebellum of Male Rats. Brain Res 2019, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.-X.; Levine, S.; Dent, G.; Zhan, Y.; Xing, G.; Okimoto, D.; Gordon, M.K.; Post, R.M.; Smith, M.A. Maternal Deprivation Increases Cell Death in the Infant Rat Brain; 2002; Vol. 133;

- Schmidt, M.; Enthoven, L.; Van Der Mark, M.; Levine, S.; De Kloet, E.R.; Oitzl, M.S. The Postnatal Development of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis in the Mouse. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 2003, 21, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapolsky’, R.M.; Meaney’, M.J. Maturation of the Adrenocortical Stress Response: Neuroendocrine Control Mechanisms and the Stress Hyporesponsive Period; 1986; Vol. 11;

- Noguchi, K.K.; Walls, K.C.; Wozniak, D.F.; Olney, J.W.; Roth, K.A.; Farber, N.B. Acute Neonatal Glucocorticoid Exposure Produces Selective and Rapid Cerebellar Neural Progenitor Cell Apoptotic Death. Cell Death Differ 2008, 15, 1582–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.V. Stress-Hyporesponsive Period. In Stress: Physiology, Biochemistry, and Pathology Handbook of Stress Series, Volume 3; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 49–56 ISBN 9780128131466.

- MS, B.; JC, D.; G. , S. THE DEVELOPING BRAIN REVEALED DURING SLEEP. Curr Opin Physiol 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ma, L.; Yang, G.; Gan, W.-B. REM Sleep Selectively Prunes and Maintains New Synapses in Development and Learning. Nat Neurosci 2017, 20, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooley, J.C.; Sokoloff, G.; Blumberg, M.S. Movements during Sleep Reveal the Developmental Emergence of a Cerebellar-Dependent Internal Model in Motor Thalamus. Curr Biol 2021, 31, 5501–5511.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, D.; Sokoloff, G.; Blumberg, M.S. Corollary Discharge in Precerebellar Nuclei of Sleeping Infant Rats. Elife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crapse, T.B.; Sommer, M.A. Corollary Discharge across the Animal Kingdom. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008, 9, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Korovaichuk, A.; Astiz, M.; Schroeder, H.; Islam, R.; Barrenetxea, J.; Fischer, A.; Oster, H.; Bringmann, H. Functional Divergence of Mammalian TFAP2a and TFAP2b Transcription Factors for Bidirectional Sleep Control. Genetics 2020, 216, 735–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo, G.V.E.; Goularte, J.F.; Hoefel, A.L.; de Castro, A.L.; Kucharski, L.C.; da Rosa Araujo, A.S.; Lucion, A.B. Effects of Sleep Restriction during Pregnancy on the Mother and Fetuses in Rats. Physiol Behav 2016, 155, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollmer, B.; Edmonds, C.J. School Age Neurological and Cognitive Outcomes of Fetal Growth Retardation or Small for Gestational Age Birth Weight. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartkopf, J.; Schleger, F.; Keune, J.; Wiechers, C.; Pauluschke-Froehlich, J.; Weiss, M.; Conzelmann, A.; Brucker, S.; Preissl, H.; Kiefer-Schmidt, I. Impact of Intrauterine Growth Restriction on Cognitive and Motor Development at 2 Years of Age. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devaskar, S.U.; Chu, A. Intrauterine Growth Restriction: Hungry for an Answer. Physiology (Bethesda) 2016, 31, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.L.; Huppi, P.S.; Mallard, C. The Consequences of Fetal Growth Restriction on Brain Structure and Neurodevelopmental Outcome. J Physiol 2016, 594, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, W.; Liu, J. Neurodevelopment in Children with Intrauterine Growth Restriction: Adverse Effects and Interventions. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016, 29, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, P.; Baud, O.; Bouslama, M.; Evrard, P.; Gressens, P.; Verney, C. Moderate Growth Restriction: Deleterious and Protective Effects on White Matter Damage. Neurobiol Dis 2007, 26, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, J.J. Brain Injury in Premature Infants: A Complex Amalgam of Destructive and Developmental Disturbances. Lancet Neurol 2009, 8, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eixarch, E.; Muñoz-Moreno, E.; Bargallo, N.; Batalle, D.; Gratacos, E. Motor and Cortico-Striatal-Thalamic Connectivity Alterations in Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016, 214, 725.e1–725.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischi-Gomez, E.; Muñoz-Moreno, E.; Vasung, L.; Griffa, A.; Borradori-Tolsa, C.; Monnier, M.; Lazeyras, F.; Thiran, J.-P.; Hüppi, P.S. Brain Network Characterization of High-Risk Preterm-Born School-Age Children. Neuroimage Clin 2016, 11, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.L.; Bashir, M.; Santiago, C.; Farrow, K.; Fung, C.; Brown, A.S.; Dettman, R.W.; Dizon, M.L.V. Intrauterine Growth Restriction and Hyperoxia as a Cause of White Matter Injury. Dev Neurosci 2018, 40, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, A.R.A.; Wiradjaja, V.; Azhan, A.; Li, A.; Hale, N.; Wlodek, M.E.; Hooper, S.B.; Wallace, M.J.; Tolcos, M. Intrauterine Growth Restriction Alters the Postnatal Development of the Rat Cerebellum. Dev Neurosci 2017, 39, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskusnykh, I.Y.; Fattakhov, N.; Buddington, R.K.; Chizhikov, V. V Intrauterine Growth Restriction Compromises Cerebellar Development by Affecting Radial Migration of Granule Cells via the JamC/Pard3a Molecular Pathway. Exp Neurol 2021, 336, 113537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolcos, M.; McDougall, A.; Shields, A.; Chung, Y.; O’Dowd, R.; Turnley, A.; Wallace, M.; Rees, S. Intrauterine Growth Restriction Affects Cerebellar Granule Cells in the Developing Guinea Pig Brain. Dev Neurosci 2018, 40, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanez, C.; Rabin, O.; Heroux, M.; Giguere, J.F. Cerebral Amino Acid Changes in an Animal Model of Intrauterine Growth Retardation. Metab Brain Dis 1993, 8, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tita, A.T.N.; Andrews, W.W. Diagnosis and Management of Clinical Chorioamnionitis. Clin Perinatol 2010, 37, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylijoki, M.; Lehtonen, L.; Lind, A.; Ekholm, E.; Lapinleimu, H.; Kujari, H.; Haataja, L. Chorioamnionitis and Five-Year Neurodevelopmental Outcome in Preterm Infants. Neonatology 2016, 110, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendson, L.; Russell, L.; Robertson, C.M.T.; Liang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Abdalla, A.; Lacaze-Masmonteil, T. Neonatal and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Very Low Birth Weight Infants with Histologic Chorioamnionitis. J Pediatr 2011, 158, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasef, N.; Shabaan, A.E.; Schurr, P.; Iaboni, D.; Choudhury, J.; Church, P.; Dunn, M.S. Effect of Clinical and Histological Chorioamnionitis on the Outcome of Preterm Infants. Am J Perinatol 2013, 30, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, A.; Kendrick, D.E.; Shankaran, S.; Stoll, B.J.; Bell, E.F.; Laptook, A.R.; Walsh, M.C.; Das, A.; Hale, E.C.; Newman, N.S.; et al. Chorioamnionitis and Early Childhood Outcomes among Extremely Low-Gestational-Age Neonates. JAMA Pediatr 2014, 168, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limperopoulos, C.; Bassan, H.; Sullivan, N.R.; Soul, J.S.; Robertson, R.L.J.; Moore, M.; Ringer, S.A.; Volpe, J.J.; du Plessis, A.J. Positive Screening for Autism in Ex-Preterm Infants: Prevalence and Risk Factors. Pediatrics 2008, 121, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.G.; Willis, K.A.; Jobe, A.; Ambalavanan, N. Chorioamnionitis and Neonatal Outcomes. Pediatr Res 2022, 91, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normann, E.; Lacaze-Masmonteil, T.; Eaton, F.; Schwendimann, L.; Gressens, P.; Thébaud, B. A Novel Mouse Model of Ureaplasma-Induced Perinatal Inflammation: Effects on Lung and Brain Injury. Pediatr Res 2009, 65, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L.; Van Steenwinckel, J.; Fleiss, B.; Scheuer, T.; Bührer, C.; Faivre, V.; Lemoine, S.; Blugeon, C.; Schwendimann, L.; Csaba, Z.; et al. A Unique Cerebellar Pattern of Microglia Activation in a Mouse Model of Encephalopathy of Prematurity. Glia 2022, 70, 1699–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L.; Van Steenwinckel, J.; Fleiss, B.; Scheuer, T.; Bührer, C.; Faivre, V.; Lemoine, S.; Blugeon, C.; Schwendimann, L.; Csaba, Z.; et al. A Unique Cerebellar Pattern of Microglia Activation in a Mouse Model of Encephalopathy of Prematurity. Glia 2022, 70, 1699–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudsnuk, K.M.A.; Champagne, F.A. Epigenetic Effects of Early Developmental Experiences. Clin Perinatol 2011, 38, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, W. Regional Differences in the Distribution of Golgi Cells in the Cerebellar Cortex of Man and Some Other Mammals. Cell Tissue Res 1974, 153, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beekhof, G.C.; Osório, C.; White, J.J.; van Zoomeren, S.; van der Stok, H.; Xiong, B.; Nettersheim, I.H.; Mak, W.A.; Runge, M.; Fiocchi, F.R.; et al. Differential Spatiotemporal Development of Purkinje Cell Populations and Cerebellum-Dependent Sensorimotor Behaviors. Elife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojcinski, A.; Morabito, M.; Lawton, A.K.; Stephen, D.N.; Joyner, A.L. Genetic Deletion of Genes in the Cerebellar Rhombic Lip Lineage Can Stimulate Compensation through Adaptive Reprogramming of Ventricular Zone-Derived Progenitors. Neural Dev 2019, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heijden, M.E.; Sillitoe, R.V. Interactions Between Purkinje Cells and Granule Cells Coordinate the Development of Functional Cerebellar Circuits. Neuroscience 2021, 462, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beekhof, G.C.; Gornati, S. V.; Canto, C.B.; Libster, A.M.; Schonewille, M.; De Zeeuw, C.I.; Hoebeek, F.E. Activity of Cerebellar Nuclei Neurons Correlates with ZebrinII Identity of Their Purkinje Cell Afferents. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voogd, J. Cerebellar Zones: A Personal History. The Cerebellum 2011, 10, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).