Introduction

Inter-sectoral linkages in the form of demand for inputs and supply of outputs between different sectors are foundational for economic diversification. Under favourable political-economic conditions, such linkages bear the potential to generate income and employment multipliers and sustain higher levels of growth, underpinned by more diversified set of goods and services that an economy can produce. Meanwhile, in many resource-rich countries the extractive sector has failed to link up with other economic sectors, and instead has operated in enclaves (Hansen, 2014). Still, it remains puzzling why countries have struggled to develop other economic sectors, despite the relatively significant fiscal revenues generated from exporting unprocessed extractive resources.

Staples theory provided one approach to explain this conundrum. It argues that countries that have relied on exporting primary commodities (i.e. staples) have experienced volatile growth patterns and that these can be explained by the complacent role that states and political-economic constituencies have played (Findlay & Lundahl, 2017). In many developing countries, such dependency has been coupled with the inability of local businesses to participate in the supply of goods and services to the extractive sector. To address this dilemma, some governments have resorted to introducing local content policies. However, the challenge has been that such measures have centred on the extractive sector; thus, exacerbating rather than alleviating dependency on the extractive sector (Weldegiorgis et al., 2021). The typically narrow conceptualization of local content policies has led resource-rich countries to focus on the development of extractive sector supply chains by stipulating, enforcing, and monitoring targets for local procurement, workforce development, and technology transfer. At the same time, they have overlooked economic diversification which would require different strategies and policies.

Ideally, building inter-sectoral linkages should be conducive to achieving economic diversification. Building on Hirschman (1981), the analyses of resource-based linkages have evolved over the years. For example, value chain analyses have examined the economic value that can be retained through downstream processing and the broader value chain, including through packaging, distribution, and marketing (Fessehaie, 2012). Morris et al. (2012) have proposed a ‘general model of linkage development’ premised on developing local productive capacity to supply inputs to the mining industry. The authors argue that linkages may occur naturally through market forces, especially in terms of domestic capabilities and technological innovation, although they also mention the role of industrial policies and public-private sector collaboration. More recently, Atienza et al. (2021) has measured linkages at the sub-national level in the case of Chile, applying a multi-scalar approach using the input-output method. Weldegiorgis et al. (2023) have applied the partial hypothetical extraction input-output method to measure the inter-sectoral linkages with the extractive sectors in Tanzania and Botswana. These latter two studies have been motivated by gaining a better understanding of the sector’s role in contributing to economic diversification, but they have fallen short of developing a new theory on the nexus between linkages and achieving diversification.

The main argument of the article is that existing theories are too narrowly focused on the extractive sector and economic linkages, and most efforts and resources are concentrated on providing the goods and services the sector demands. This approach bears the risk that sector-focused policies concentrate on promoting economic activities that increase backward linkages, but they are not joined-up with other sectors of the economy, including those that may be prioritized to pursue sustainable and inclusive development. To address the disconnect, this article offers a theoretical model that seeks to make explicit how inter-sectoral linkages can leverage the extractive sector to achieve economic diversification, with the view to then push even further towards economic transformation.

The remainder of the article is organized in three sections: First, it introduces a conceptual framework centred around positive economic transformation. Building on this framework, it presents and explains the theoretical model. Finally, it places the theoretical model in the context of (a) the global energy transition away from fossil fuels and the increased demand for minerals that this transition requires and (b) the tension between the complementary role of states and markets in economic diversification and transformation but also the risk that state and market failures can occur at the same time. The article concludes, offering suggestions for future research.

Economic Transformation Framework

This section proposes an economic transformation framework that underpins the theoretical model explained in the next section. We define positive economic transformation as a process of progressive industrial upgrading that occurs following an economic shift from primarily relying on exporting extractive resources to producing a broad range of goods and services based on the efficient utilization of outputs from the inter-sectoral linkages of the extractive sector with other sectors. Economic transformation is often used interchangeably with economic growth and structural transformation. We see intricate and bidirectional enforcement between economic growth and economic transformation, each stimulating and facilitating the other. For example, foreign direct investment (FDI)-driven economic growth generates higher incomes and profits leading to increased savings, investments, consumer demand for a wide range of goods and services, and infrastructure development that can be channelled into high productivity sectors. In turn, structural change involving a shift in factor productivity and export growth induces economic growth in diverse sectors.

Positive economic transformation is premised on policy decisions that allow non-elite economic actors to seize economic opportunities in the extractive sectors and industries that do not rely on capturing resource rents. In this framework, we critique the narrow conceptualization of linkage building as understood by those who promote local content-focused backward linkages, and which increases rather than decreases an economy’s dependence on exporting raw minerals. We term this conceptualization the centripetal force of the extractive sector. We argue that if policies aimed at building linkages are centred around the extractive sector, they bear the risk of reactively focusing on meeting a demand for goods and services that are specific to the sector. The framework is underpinned by crucial steps that form the basis for the theoretical model.

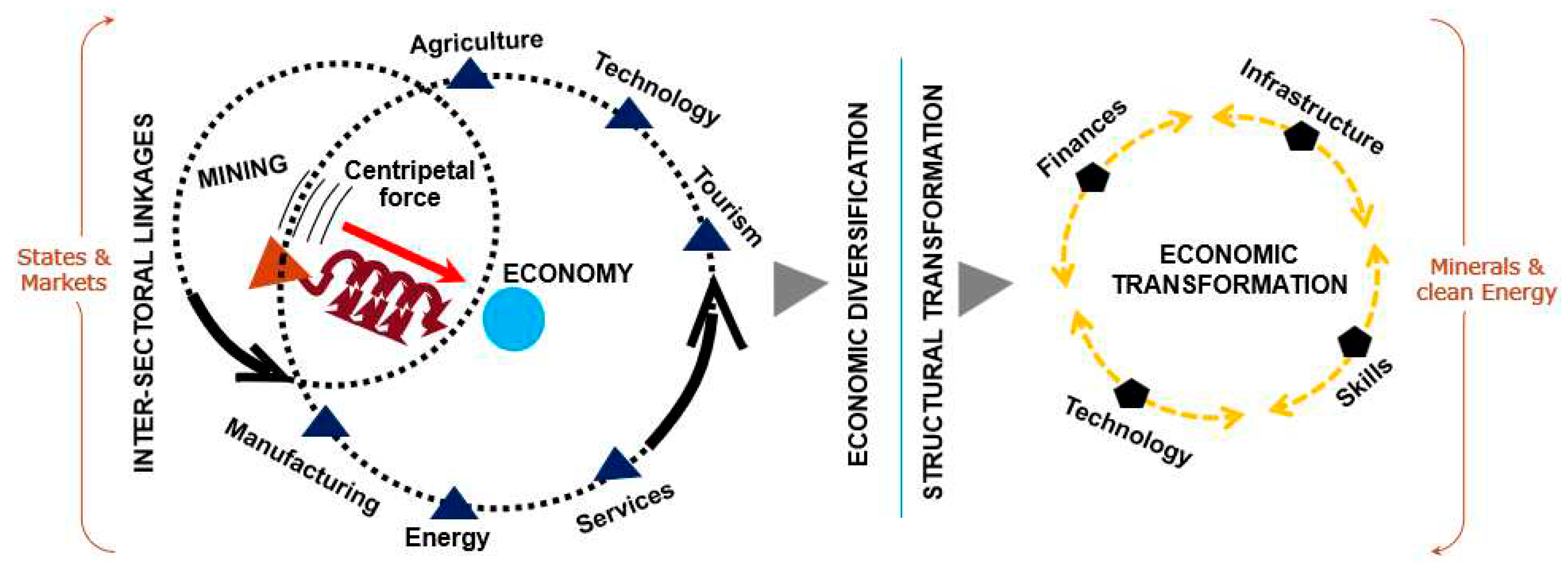

First, as indicated in the left-hand side of

Figure 1, we argue that if the extractive sector is to contribute to economic diversification and, ultimately positive economic transformation, the conceptualization needs to be corrected. We propose that this involves counterposing the

centripetal force of the extractive sector with its

centrifugal potential, whereby building inter-sectoral linkages should create ‘utilization content’ that serves the economy more broadly. The proposed counterposing places the broader economy at the centre of analysis drawing attention to the question of how the extractive sector could potentially inter-link with other economic sectors beyond the narrow focus on the extractive sector’s demand. The question shifts to where the overlaps are between the input factors that the extractive sector and other sectors demand now and into the future. There is, of course, complementarity between

centripetal forces and

centrifugal potential in that achieving greater economic diversification depends, in the first instance, on utilizing inputs that the extractive sector needs as well as the outputs that it produces. With

centrifugal potential, greater diversification strengthens the economy’s resilience, for example, against external shocks that are specific to one or several sectors. In effect, it means seizing new opportunities and spreading risks by putting one’s eggs across different baskets.

Second, economic diversification should be conceived of as a structural transformation process to guide policy and investment decision making towards raising productivity. An empirical study by Joya (2019) found that there is more potential to raise productivity, when the production structure and exports are broadened and diversified rather than being concentrated in resource-based industries. The structural transformation of an economy, therefore, involves a shift from low to high value-added production and exports, broadening of the tax base, and reallocation of factors of production to high productivity sectors (Elhiraika et al., 2019; Whitfield et al., 2015). Such a shift to high value-added production occurs when factor endowments such as labour, technology and infrastructure are upgraded, leveraging the efficiency gained through inter-sectoral linkages. While economic diversification is a key step to transform the economic structure by expanding economic activities within and across sectors, it is not an end but a means to achieve a positive economic transformation.

Third, shifting to upgraded industries should involve progressively improving efficiency, productivity, and competitiveness, resulting in comprehensive and sustained economic transformation that lifts living standards. Positive economic transformation process encompasses technological advancements, innovation, and increase in human, physical, and financial capital. However, this process is not straightforward; because it takes time for multiple factors to coordinate and interact to ensure the pathway from inter-sectoral linkages to positive economic transformation is realized. We argue that achieving this pathway is incumbent upon policy makers and industry actors (1) harmonizing the interplay between state intervention and market dynamics, and (2) optimizing the potential inherent in the intersection of extractive minerals and the transition to clean energy for harnessing sustainable energy solutions.

The state and market nexus relates to the political transformation needed; within which the article discusses broadly conceptualized industrial policies and institutional capacity that are needed to catalyze utilization of returns or outputs from inter-sectoral linkages and diversification. However, because of the limited scope of the paper, we do not provide an in-depth analysis of the political and social dimensions of economic transformation. Embedded in the transformation is, therefore, the connection and interdependence between politics and economics. How public institutions function internally and across public entities, in terms of the consistency and objectives of policies and regulations, determine the breadth and depth of inter-sectoral linkages and the potential to contribute to positive economic transformation. Furthermore, collaborative efforts between the public and private sectors are crucial, upon which the successes of the public sector’s proactive and sensible interventions are conditioned. The article departs from the dualistic notion around the state and market dynamics, and instead explores their complementarity and interdependence.

The Utilization Model

Building on the economic transformation framework, we develop the Utilization Model as a ‘theoretical’ model that lays out the pathway from building inter-sectoral linkages towards achieving positive economic transformation. The concept of utilization is already present in the literature. In simple economic terms, it is conceived as optimizing the use of available inputs to generate maximum outputs. Inputs can differ; for example, the USA’s Federal Reserve Board measures capacity utilization in the industrial sector as ‘a ratio of the actual level of output to a sustainable maximum level of output, or capacity’ (Corrado & Mattey, 1997). This is crucial in terms of utilizing capacity-related inputs such as technology, skills, and capital to generate the maximum possible output that is more sustainable. Performing optimization in economic theory is influenced by constrains as much as the objectives. The constraints that must be satisfied to realize optimization may relate to budget, resources, technical and regulatory constraints. Our model considers utilization in a more comprehensive manner and is premised on the three-stepped conceptual framework described in the previous section.

First, the model builds on economic linkage theory, which distinguishes between different types of linkages: upstream or backward linkages (procurement of goods and services); downstream or forward linkages (processing of minerals); side-stream or lateral linkages (skills, professional and technological capabilities); fiscal linkages (taxes, non-tax, and royalty payments); consumption linkages (wages and profits); and infrastructure linkages (for shared use or solely for community use). In addition to these types of linkages, Franks (2020) introduced utilization linkages and defined these as the ultimate domestic use minerals beyond their beneficiation. The term ‘beneficiation’ is defined from an engineering point of view around the processing of mineral ores and value adding. However, some economists conceive of beneficiation as the transformation of minerals into a complete product for use in manufacturing (Grynberg & Sekakela, 2015).

The

Utilization Model is partly premised on an economy’s comparative advantage. According to Lin et al. (2011), this advantage is based on an economy’s factor endowment, which should evolve from one level of development to another. In addition to resource-related endowments, the model also considers institutional endowment as part of the enabling factors discussed in the next section. Based on such a comparative advantage, Tier 1 (linkage formation) in

Figure 2 is about how the different linkage forms can be fostered between the extractive and other economic sectors. A review of the literature explains how linkage building has mostly focused on backward linkages, which have been mining-centric (Weldegiorgis et al., 2021). The model emphasizes the importance of a utilization strategy to guide broader linkage building and achieve positive economic transformation.

Second, the model postulates that these linkages can contribute to achieving greater economic diversification through utilization streams. In essence, we argue that there is a difference between the presence of linkages and the utilization of the ‘service’ that the linkages provide for economic diversification, which could be the use of processed minerals in manufacturing, or the investment of the fiscal revenues accrued in strategic economic sectors. Here we extend the utilization concept introduced by Franks (2020) such that the utilization streams encompass (i) mineral utilization, (ii) public sector revenue utilization, (iii) private sector revenue utilization, (iv) infrastructure utilization, and (v) skills and technology utilization (

Figure 2). Through these utilization streams, we argue that public and private sector policies and strategies must target the development of four

diversification levers, a catch-all term we use to refer to the four factors of physical capital, enterprise architecture, human capital, and financial assets. These

diversification levers, which are shown in

Figure 2 and discussed in the next sub-sections, are not sector specific, thus avoiding single sector specialization. Neither are they static, instead they are dynamic adapting to changing technology, market conditions, and corporate and societal needs.

In Tier 2 (linkage utilization) of

Figure 2, each of the utilization streams is maximized, in which case there are inputs from each of the linkage forms that need to be utilized to develop the

diversification levers in Tier 3. For example, some of the key inputs generated from the backward and forward linkages with the extractive sector are skills and technology, which can be utilized to develop enterprise architecture and human capital. The measures of ‘capacity utilization’ provided by the USA’s Federal Reserve Board (Corrado & Mattey, 1997) are but one of the mechanisms to ensure that maximum outputs are generated. The

Utilization Model provides a strategic direction as to what these outputs can be utilized for based on a national economic strategy.

In terms of mineral utilization, one way the inputs generated through forward linkages can be utilized is when minerals are directly used in development sectors such as infrastructure. But we argue that such infrastructure development cannot be considered as utilization unless it is ultimately used in developing non-mining dependent sectors. Secondly, processed minerals can be beneficiated as inputs in relevant manufacturing sectors. Based on the Utilization Model, construction and industrial minerals can be utilized to develop physical infrastructure including energy, transport, and communication as diversification levers. Mineral utilization for infrastructure can also be supplemented by the utilization of infrastructure developed by industry for its own use.

Similarly, revenues accrued by both the government and local firms linked to the extractive industry through the various linkage forms can support the above-mentioned diversification levers. Revenues may also be kept as savings for future utilization through respective investments and for maintaining macroeconomic stability through the growth position achieved. Exogenous shocks, such as changes in the stock market and FDI, can have a significant impact on revenues. Similar argument made by the model is that money generated through revenues cannot be considered as utilized unless it is shielded from inefficient spending and corruption but instead becomes of service for other sectors through the diversification levers, for example by being invested in improving education attainment and skills development.

Third, these

diversification levers are crucial for progressive industrial upgrading through increased productivity, technological advancement, and competitiveness, ultimately leading to positive economic transformation. Tier 3 is where the various areas developed in Tier 2 are consolidated to accumulate relevant physical and human capital, targeted investment of financial assets, and development of enterprise architecture leading to the constant incremental levels of industrial upgrading. Moreover, there are crosslinks among these

diversification levers as shown by the red dotted lines in

Figure 2. Accordingly, enterprise architecture and human capital would be needed to develop physical capital. Some funds from the accumulated financial assets would also be invested to develop enterprise architecture and human and physical capital.

The development of these diversification levers goes beyond selecting specific economic sectors. This is because these levers can be applied to support diverse, rather than specific, sectors, and their application is not a one-off but can adapt with time to changes in technology and markets. This is a departure from Hirschman’s theory (and others who improved it) of selectively investing in key sectors, which initially creates disequilibria but subsequently induces increased production (Hirschman, 1958; Lenzen, 2003). However, it is important to note that identification of key economic sectors from a linkages perspective helps, as a diagnostic step, to measure structural interdependence between economic sectors. This step is demonstrated in the analysis by Weldegiorgis et al. (2023), which helps gain a comprehensive understanding of the current state of the economy and identify the strategic sectors that diversification efforts may need to focus on. The sub-sections below discuss the diversification levers in detail.

The Utilization Model contributes to the linkage theory in three areas. First, it underlines that linkages created in the form of input and output transactions between the extractive and other economic sectors do not automatically lead to economic diversification, let alone positive economic transformation. More importantly, there is a risk of dependency on the extractive sector, as businesses incline towards developing sector-specific supply chains. Second, by detailing the three-tiered process for the pathway from linkages to positive economic transformation, the model exposes a major gap in the existing analysis and the popular uptake of local content policies, which have only focussed on the first tier of linkage building. It sheds light on how the other two tiers are critical to achieve the pathway to positive economic transformation. Third, the model argues that the pathway to positive economic transformation is crucially determined by how policy makers and industry actors: (1) address the challenges posed by state and market dynamics, and (2) maximize the opportunities arising with the interface between extractive minerals and the clean energy transition.

Physical Capital

The development of infrastructure is key to unlocking an efficient network of economic activities and markets within and across borders. Importantly, the development of both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ infrastructure will always be needed by each industrial structure that evolves one after the other (Lin et al., 2011). Hard or physical infrastructure could be related to transport and communication such as roads, railways, seaports and airports, optic fibre cables, ICT infrastructure, waterways; buildings such as private and commercial buildings, dams, storage; and energy such as solar systems, hydropower, thermal energy, and wind turbines. Soft infrastructure relates to the human capital, enterprise architecture, financial assets, and institutional capacity. Relating to physical infrastructure, resource-rich countries need ‘more than USD 1.3 trillion of infrastructure investment a year to 2030 to sustain their combined projected national GDP growth’ (McKinsey Global Institute, 2013:50).

A public-private sector collaboration can apply the Utilization Model to develop physical capital. First, mineral utilization implies the transformation of minerals and metals into productive assets. This entails the direct utilization in infrastructure development of construction and industrial minerals such as sand, clay, gravel, stones, and bricks as well as products of processed development minerals including cement, steel, glass, and polymer (Franks, 2020). In addition, other commodities including critical minerals such as cobalt, and the rare earth elements, and copper will be needed to develop clean energy sources and other high technology applications (Ali et al., 2017). The utilization of these minerals would require a broad and long-term strategy and concerted effort led by a highly capable and ‘entrepreneurial’ government body in collaboration with the extractive industry. Mineral utilization also needs to involve the private sector that is specifically working in infrastructure development and in intermediate production such as the production of steel and cement. It is the coordination of all these entities and their resources that could ensure successful mineral utilization to develop physical infrastructure for economic diversification.

Second, resource-rich countries have the option of utilizing their extractive-based fiscal revenues to develop physical infrastructure that is identified as part of a national economic strategy. Malaysia has been cited as a case where policy makers have decided to utilize the revenues generated by its rubber, tin and oil sectors to invest in energy, transport and communication infrastructure (Gelb, 2012). In most cases, extractive-based revenues form part of national budgets and so it becomes hard to pinpoint the extent of extractive-based revenues utilized for infrastructure development. What matters is the existence of a targeted physical infrastructure development plan and its implementation, and governments could play a vital role in ensuring that a portion of public revenues from the extractive sector is invested in infrastructure development according to the national economic strategy.

Third, the Utilization Model accounts for other economic sectors utilizing infrastructure that the extractive industry built primarily for its own use. The extractive industry is estimated to cover about 9% of the USD 1.3 trillion investments that resource-rich countries need for physical infrastructure including railways, roads, and ports (McKinsey Global Institute, 2013). This is large-scale capital investment that needs to be planned well in collaboration with host governments. There are two ways to approach this: first, industry can cover the cost, but to share use of that infrastructure after securing the right to build the infrastructure. The second approach is for governments to contribute to the investments through utilizing revenues or providing fiscal incentives for the construction of shared infrastructure in exchange for negotiating access to and the shared use of that infrastructure. Although these options depend on the type of commodity mined and can be difficult to implement, evidence suggests that it is possible to utilize revenues for infrastructure development, as well as negotiate a successful shared use of infrastructure developed by the extractive industry (CCSI, 2016). In both cases, it is important that policy makers take an interest in the design of infrastructure that fits within a greater industrialization scheme that the host country should develop, while fostering mutually beneficial partnership with the industry.

However, extractive companies have concerns regarding political, operational, and other risks of shared infrastructure use. This may be addressed by having an independent entity in charge of developing, operating, and maintaining infrastructure in addition to putting in place legal and regulatory framework for efficient utilization of shared infrastructure (Thomashausen & Ireland, 2015). While this risk may be more pronounced when bulk commodities are involved, other forms of infrastructure such as power supply may be less contentious. For example, water infrastructure in Central Queensland, Australia (such as the dam built by Mount Isa mine), was largely financed by extractive companies and serves multiple users including the extractive sector. Therefore, a successfully managed infrastructure for shared use and the post-mining use of such infrastructure by other economic sectors could boost economic diversification.

Enterprise Architecture

The development of the desired types of enterprises hinges on comparative advantage, market mechanisms, and a broadly scoped industrial policy at a given point in time. At the national level, the government would be guided by a national economic strategy to select and develop industries and businesses based on not only comparative advantage, but also by following policy framework to apply sensible protection and mechanisms including subsidies and trade restrictions. Notwithstanding, there is no specific industrial structure that can be pursued when identifying winning industries or businesses to support or losing ones to protect. Singer (1950:476) notes that ‘the most important contribution of an industry is not its immediate product and not even its effects on other industries and immediate social benefits, but perhaps even further its effect on the general level of education, skill, way of life, inventiveness, habits, store of technology, creation of new demand, etc’. Which is why this second diversification lever is not about developing specific businesses, but developing the architecture needed for businesses to thrive.

By enterprise architecture we refer to capabilities related to entrepreneurial skills, business leadership and management, organizational structure, technology and innovation, business rules and regulations. We consider the definition of enterprise architecture as an ‘instrument to articulate an enterprise’s future, while also serving as a coordination and steering mechanism toward the actual transformation of the enterprise’ (Greefhorst et al., 2011:3). Economy-wide (macro-level) transformation requires a transformation at the enterprise (micro) level. Equipped with an enterprise architecture, businesses can design an enterprise strategy and execute it by deploying a well-functioning business model, thus positioning well to diversify when needed and upscale with growing capital accumulation. The capabilities needed to develop a high productivity-yielding enterprise architecture are either learned through deliberate interventions such as skills development programs or acquired through experience. The Utilization Model helps to point to respective opportunities.

At the firm level, supplier businesses would accumulate business knowledge and capital through the opportunities created using a well-designed and functioning local content requirement to supply to the extractive industry. Furthermore, enterprise architecture can be fostered through a macro-level business strategy within a national economic strategy. As part of this strategy, an entrepreneurial government initiates a scheme that supports businesses while, at the same time, enables collaboration between businesses and large-scale producers. Such a scheme could involve providing investment subsidies, tax and tariff exemption, and trade incentives that allow imports of foreign intermediate inputs whose production requires high level technology (Stone et al., 2015). Indeed the South Korean economic development miracle is largely attributed to the government’s committed investments in innovation and technology, growth-promoting institutions and public policies, and high quality workers and entrepreneurs, among others (Harvie & Lee, 2003). Such a political economic approach also involves skills and technology utilization, leveraging the upstream, downstream, and side-stream linkages with the extractive sector (see

Figure 2). As businesses constantly increase their competitiveness, they would invest in business ventures in which they could exploit favourable market conditions for specialized products and take advantage of government facilitation.

In addition to learning by experience and more deliberate support schemes, an active intervention may see governments invest in programs for developing skills and technology, such as establishing centres of excellence. When investing in enterprise architecture development, governments can deploy state revenues, while business companies can reinvest a share of their returns. In this case, governments would rely on an effective generation and administration of fiscal income from tax and non-tax payments related to the extractive sector’s production as well as to the consumption of sector-related wages and profits. Malaysia, for example, has utilized revenues through investments in productive assets including human capital, machinery, and institutions (Chang & Lebdioui, 2020). Companies, meanwhile, invest the revenue savings they accumulate through their upstream, downstream, and side-stream linkages with the extractive sector. In both the public and private sector revenue utilization, a broadly scoped industrial policy and institutional capacity play a crucial role of coordination, alignment with set strategy, and effective implementation of enterprise architecture development.

Human Capital

Human capital relates to the technical, managerial, and professional skills of individuals. Education is an important foundation for a population to innovate and adapt to different production processes across different sectors. Skilled human capital in the mould of engineers, scientists and technicians can be flexibly engaged in various economic sectors, particularly the manufacturing and infrastructure sectors. A labour with transferable skills can move more easily across sectors and firms, and is key to facilitating rapid structural change (McMillan et al., 2014). According to McMillan et al. (2014), under-development in many resource-rich countries is characterized by the large gap in inter-sectoral productivity. Thus, what matters for economic transformation is not the development of workforce skills to match the labour skills demand of the extractive sector or any other economic sector, but broad-based skills that are easily transferable across sectors (Dietsche, 2020).

The extractive sector directly employs a very limited number of highly productive employees. If broad-based skills are not developed, the movement of the few highly skilled workers to low productive activities (or unemployment) at the end of mining tenure could cause growth-reducing structural change. Therefore, as McMillan et al. (2014) observe in their empirical results comparing Asia to Africa and Latin America, it is not the increase in productivity within individual economic sectors that determines economic transformation, but how political economic decisions enable broad-based structural transformation. Therefore, investing in the development of broad-based human capital, while at the same time leveraging the extractive sector for such a purpose via the various linkage formations, can contribute to positive economic transformation.

Human capital development can potentially emerge from utilizing linkage formations for positive economic transformation. There are different ways of utilizing public sector revenues collected through fiscal and consumption linkages to develop human capital; and this could be determined by various factors including political, social, and economic contexts. One of these ways is when governments set aside a specific fund for R&D and higher education, which are critical components of human capital development. Most developed countries have government finances invested in R&D, which make up the larger proportion of industry funding. For example, Sweden, Finland, Israel, and lately Korea top the list of countries that reached 3% or more of gross expenditure on R&D to GDP over the last two decades (OECD, 2023).

There could be other forms of funds that governments may set up, but the question is whether these funds are targeted, structured, and managed well for broad-based skills. One of the critical factors for South Korea’s fast economic development is putting in place organizational structures consistent with competitive strategies. Proactive production and operational management policies in South Korea entail assigning ‘high-quality managers to the shopfloor and inspire initiatives on the part of such managers to develop the skills of the workforce and to improve process performance’ (Amsden, 1992:161). In which case, institutional capacity and partnerships with educational institutions, industry, and other relevant organizations are crucial to not only set targeted strategies, but also see them through to completion. Part of the strategizing exercise is knowing one’s strengths, which could be a large labour force as in the case of many developing countries and the different mechanisms that can be introduced utilizing not only public revenues but also supportive education and industrial policies.

As a second utilization stream, the private sector (such as businesses linked through upstream, downstream, and side-stream with the extractive sector) could utilize revenue savings to upgrade and invest in new human capital. In doing so, the private businesses themselves (because of future market indications) or upon prompts and facilitation by a dedicated government entity would align with the national industrial strategy. While the overarching responsibility to develop broad-based human capital rests majorly on governments, the private sector and educational and non-government organizations also play important roles. In Sweden, conscious policy decision making regarding technical institutions, coupled with quality higher education, have been instrumental in creating new technologies (Blomstrom & Kokko, 2007). In addition to the leading role of governments in advancing R&D, industry can be incentivized to contribute to R&D. For example, Norway applied to good effect some licensing-related rewards and other preferential treatment to companies that were involved in R&D partnerships (CCSI, 2016).

The third utilization stream applicable to human capital development relates to the skills and technology that can be acquired through employment and skills training, directly with the extractive sector and indirectly with downstream, upstream, and side-stream businesses. This type of utilization is less straight forward than the other two, because it involves identifying and pursuing the types of transferable skills developed following involvement in the extractive sector and linked businesses. While attempts are made by governments and industry to identify and develop transferable skills for locals, it is a complex endeavour determined by several factors, chief of which are individual ambitions and long-term objectives.

There are two crucial aspects to human capital: one is time dependency, which refers to the fact that human capital development through education, training and experience takes time, and hence proactive long-term planning and implementation is necessary for effective utilization of the developed skills in as a timely manner as industrial development requires it. The other aspect is compatibility, meaning whether the quality and quantity of the developed skills match the job market demand. It is important for the development of human capital to be proportionate with industrial strategies, so as to avoid oversupply or undersupply of human capital that could constrain or overburden economic development (Lin, 2012). Therefore, the development of broad-based human capital should inform the skills and technology utilization stream, so that the skills feedstock is upgraded by the identified and pursued broad-based skills within the extractive sector and, in turn, meets the sector’s demand for specific skills.

Financial Assets

The term ‘financial assets’ is used here to refer to the accumulated and invested financial gains or revenues by both the private sector and public sector (e.g., a sovereign wealth fund) to generate profit and ultimately be invested in various productive areas. Examples of such assets, from a public sector perspective, include Botswana’s Pula fund and Norway’s Pension Fund, which are savings of extractive-based revenues for future investments. Different to the revenues utilized in real asset investments such as physical and human capital, the revenues set aside in financial assets could be funds used for manufacturing investments or enterprise development, or fiscal stabilization in the event of commodity price fluctuations, or for investments in real assets when the need arises. The distinguishing factor from the direct revenue utilization discussed in the previous sub-sections is that financial assets are developed as diversification levers through savings of revenues and the returns generated.

Obviously, the extent of extractives-based revenues that can be generated fluctuates, because of changes in prices, mine lifecycle, and other factors. Thus, it would be prudent for governments not to rely on extractives-based fiscal revenues for strategic economic development. Rather, keeping separate accounts like a sovereign wealth fund that could then be utilized for future investments would be sensible, not to mention the importance of putting in place the best possible fiscal policies. Here, there is time dependency and credibility issues that characterize management of such future funds, in which case, institutional capacity to plan, strategize and facilitate timely implementation is crucial. For example, Japan prudently managed its public savings and diversified investment portfolios through a Fiscal Investment and Loan Program; encouraged private savings and investments through tax laws and other measures; allowed private enterprises to exercise aggressive entrepreneurial leadership on the direction of investments, while taking a backseat to provide an enabling and supportive environment; and facilitated the development of a ‘unique set of cooperative labour-management relationships that promote high quality work and rapid productivity growth’ (Schultze, 1983:6).

Financial assets, from a private sector perspective, are accumulated by non-extractive businesses using private sector revenue utilization and are set aside for either reinvesting in existing business operations or other business ventures. Individuals may also accumulate funds through earnings from employment in the sector, invest in financial assets, and utilize these in new business ventures. Most profit-based companies, at least large-scale companies, employ financial management mechanisms, such as a project finance model that allows them to invest in new innovative business activities, while minimizing the risk of exposing the rest of their activities to financial bankruptcy (Halland et al., 2014). These mechanisms naturally are intended to uphold the interests of the companies, but the government may need to reorientate the new business activities developed in alignment with national economic strategy, either using licence issuance and/or incentives or involvement through state-owned enterprises.

Ultimately, the aim is to align the private and public sector sides of financial asset investments towards developing a diversified economy. In the process of financial assets development and future investments by the private sector, there are important skills such as financial and business management skills, which horizontally complement the development of enterprise architecture and human capital. In fact, such complementarity exists among all the four diversification levers, each of which therefore needs to be developed to achieve a positive economic transformation.

Opportunities and Challenges

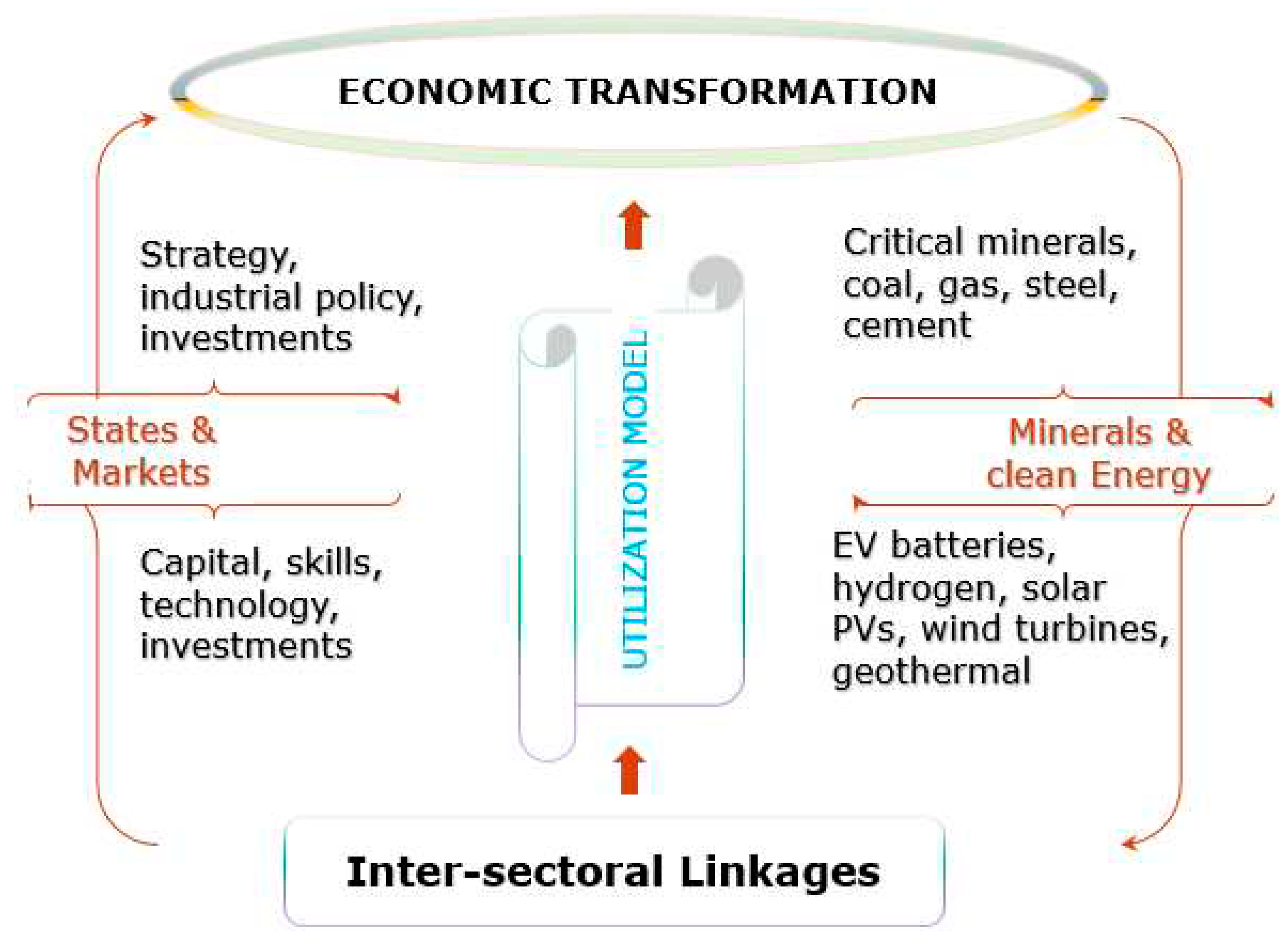

The

Utilization Model is underpinned by multiple factors, chief of which is a set of twin nexuses (see

Figure 3). The first nexus refers to the minerals and clean energy interdependence and interlinkage that is an important and contemporary driver for which the

Utilization Model must navigate. Structural transformation does not only hinge on diversifying beyond the extractive sector, but also on enhancing technology-led clean production in contemporary economic sectors. We use the definition of clean production as ‘the application of environmentally and socially sensitive practices to reduce the negative impact of manufacturing activities while, at the same time, harmonizing the pursuit of economic benefits’ (Baines et al., 2012). With growing pressures to commit to the Paris climate accord (United Nations, 2015), innovations to harness minerals and metals for developing clean energy are critical to power clean production in the manufacturing and other economic sectors. Research indicates positive effects of innovation in renewable energy technology on changes in industrial structure (Ge et al., 2022). It is, however, still less understood how mineral resources can be leveraged to diversify and develop technology-led economies.

Different types of minerals and metals have been identified as critical for the transition to clean energy (IEA, 2021). In the energy-intensive industrial sectors such as the steel and cement industries, for example, the use of hydrogen has been increasingly explored as an important source for industrial decarbonization (Griffiths et al., 2021). Various options for producing hydrogen involve resources ranging from fossil fuels in the short to medium terms to water electrolysis, solar and wind turbine energy (Zou et al., 2022). While recent developments in relation to the clean energy transition can facilitate the processing and manufacturing of mineral resources for energy infrastructure, these tend to be reactionary, in the sense that they are responding to environmental concerns rather than fostering a broad-based strategy incorporating structural transformation. For example, the European Green Deal is criticized for lacking vision about the post-carbon economy and for its inadequate consideration of broad macroeconomic framework and industrial policy within which climate targets can be achieved (Pianta & Lucchese, 2020). The Utilization Model, therefore, can help develop an approach and practices aimed at utilizing extractive resources to reduce the environmental impact of industrial operations while simultaneously improving efficiency, reducing costs, and enhancing economic diversification.

The main argument in the Utilization Model is that the global pressure to transition from fossil fuels to clean energy sources has different time and resource implications for developed and developing countries. Even within these two categories of countries, there are varying national interests and priorities as well as resource endowments that affect the choices that countries make in terms of how and when to utilize fossil fuels as well as develop and adopt clean energy sources in their production processes. An important point to keep in mind is that the production of clean energy requires a substantial amount of minerals, and the mineral production in turn could benefit from clean energy, as an energy intensive activity. At the same time, fossil fuel resources such as gas and coal may be utilized to develop clean energy technology infrastructure, while also being utilized in the interim as energy alternatives (including energy mix with reduced carbon emissions) in industrial sectors.

The second and crucial nexus relates to state and market dynamics that the model considers as an important challenge that policy makers and industry actors need to address to enable the pathway from linkages to positive economic transformation. The three-tiered process explained in the previous section is within the purview and complex interdependence between state intervention through the actions of government authorities, and market forces through the actions of investors, entrepreneurs, and traders. On the market side, the private sector is behind capital investments and skills and technology advancement, while also improving productivity through supply and demand mechanisms in a competitive market. A continuum of industrial change occurs, as the market mechanism ensures optimal resource allocation (Lin et al., 2011). However, effective market mechanisms cannot exist without a capable, committed, and credible government that facilitates industrial upgrading and infrastructure development using policies, regulations, and public sector investments.

Although neo-classical economists generally discount the role governments played in the industrialization processes of developed western economies, historical records show that governments have been central in various capacities including infant industry protection, subsidies and grants such as for R&D, direct government investments, financing of cross-country learning, among many other interventions (Chang, 2003; Juhász et al., 2023). Unlike neo-classical consideration of the state’s role as an economic externality, contemporary economic affairs have embraced state intervention as demonstrated in the clean energy financing such as the European Green Deal and the USA’s Inflation Reduction Act (Bown, 2023). The increasing state intervention in what are traditionally conceived as private sector affairs is just an explicit manifestation of an otherwise toned down but historically applied industrial policies. Reflecting a harmonized interplay between state intervention and market dynamics, public-private sector interrelationships and coordination can positively influence better governance and institutional capacity, which are important determinants of economic transformation (Ahrens, 2006). The proceeding sub-sections discuss how industrial policies and institutional capacity influence the outcome of the gradual pathway to achieving positive economic transformation.

Structural Transformation Policy

The debate around industrial policy has been characterized by evolving positions with respect to market failures versus state failures (Dietsche, 2018). There is an increasing consensus on the important role states can play through an industrial policy that complements, rather than distorts, market forces (Rodrik, 2007). Although such a policy is the mandate of government, its success is limited unless it involves collaborations and partnerships with the private sector and R&D entities, in addition to cross-government coordination. As Dietsche (2018:3) argues, ‘industrial policy sits at the heart of the relationship between markets and states’ helping correct market failures, such as in dealing with costs of transactions related to information, coordination, and externalities. When state intervention and market forces are mutually inclusive, both could use each other’s specialized impacts towards achieving the desired goal. There is a great potential for industrial policy to enable state-market dynamics to work together in achieving positive economic transformation.

The design and scope of industrial policy is loosely defined both in the literature and in practice, and is often associated with import-substitution trade policies (Weiss, 2013). A more appropriate definition of industrial policies is provided by Juhász et al. (2023) as ‘those government policies that explicitly target the transformation of the structure of economic activity in pursuit of some public goal [which could be] ... to stimulate innovation, productivity, economic growth, climate transition, good jobs, exports, or import substitution’. According to Weiss (2013), the main dimensions of industrial policy are the national vision or strategy of a country, the dialogue process between actors in the private and public sectors, and the policy instruments to drive change. Based on these dimensions, we frame industrial policy as a broadly scoped policy exercised by a network-based government organization and institution to catalyze the development of the diversification levers through the various utilization streams, leveraging inter-sectoral linkages. We, thus, adopt one of the characterizations of industrial policies by Aiginger and Rodrik (2020), and use the term structural transformation policy, which fits the conceptualization of industrial policy within the utilization model.

Structural transformation policy is beyond isolated policies; it encompasses policies related to industry, energy, innovation, trade, fiscal, local content, services, and all other policies pertaining to the economy. Such an approach is crucial for the cross-sectoral coordination that is badly needed. Industrial policies are currently being reinvented, as their importance increases with agglomeration of economies, technological change, changing organization of global production, increasing financializaton of world economy, and cumulative and path dependent industrial and learning capabilities (Chang & Andreoni, 2020; Lall, 2013). To this effect, the structural transformation policy framework is dynamic and changes with changing conditions, such as market dynamics, technological innovation, national priorities, industrial progress etc. This dynamic framework implies that structural transformation policy embraces all other economic activities (not just manufacturing) and the direction of technological change, particularly incorporating environmental and societal demands (Aiginger & Rodrik, 2020). Structural transformation policy also is well equipped to navigate through a country’s options for energy transition and its ability to upgrade its clean industrial capability. Therefore, any manufacturing advancement becomes not just about enhancing productivity, but is also socially and environmentally sustainable.

In addition to catalyzing connectivity within and between the private and public sectors, structural transformation policy responds to the needs of the contemporary production process and connectivity among suppliers, producers, final assemblers, universities, technology labs, training facilities etc. This connectivity leads to increased productivity, learning and capability domains, and technology clusters (Chang & Andreoni, 2020). The Australian Industry Participation National Framework (AIP) is a case in point, which has been crucial in building relationships, streamlining information, and linking stakeholders (GOA, 2001). The connectivity as streamlined through the structural transformation policy supports effective implementation of the various utilization streams discussed using

Figure 2. For example, collaborative partnerships between industry, government and universities are crucial in the utilization of skills and technology and development of enterprise architecture.

Structural transformation policy finds its relevance in whether and how to select economic sectors with a potential for industrial upgrading through investing in the diversification levers. There is an extensive academic debate as to whether selection of growth or ‘winning’ sectors should follow or defy comparative advantage, or be decided by government through industrial policy or by market forces (Lin, 2012). Andreoni and Chang (2019:143) argue that selecting growth sectors is not just a matter of following comparative advantage, but rather a process of ‘formulating a choice set’ from a very complex system of structural interdependencies through a coordination strategy designed and applied by a central agent or the state. Such a process is dependent on institutional capacity that is discussed next. According to the Utilization Model, a complementarity exists between selecting key sectors and developing diversification levers. On the one hand, selecting key economic sectors could be important to ensure that the development of diversification levers is compatible with and targets the industrial upgrading that is sought. In turn, developing diversification levers can help address the risk of selecting winners or losers because of the applicability of the levers across sectors with increasing adaptability to technological and market changes.

Institutional Capacity

An important determinant for the success of structural transformation policy, and more broadly the Utilization Model, is the development of institutional capacity. North (1990) differentiates institutions – the formal constraints (rules, standards,) and informal constraints (codes of behaviour, norms) that shape economic performance, from organizations – the group of people in the form of economic, political, social and educational bodies responsible for the functioning of institutions. According to North (1990), the created institutions influence the creation and evolution of organizations, which in turn, influence how institutions evolve. The structures created by institutions (i.e., goals, strategies) and organizations (i.e., skills and coordination) for human interaction are so crucial in the effective implementation of the pathway from inter-sectoral linkages to positive economic transformation. The constant changes in interdependence between institutional frameworks and organizational structures are reflected in how the structural transformation policy evolves and achieves outcomes. The outcomes could vary depending on what North (1990) refers to as political and economic transaction costs in the human interactions. Some outcomes involve leveraging opportunities and capabilities for the greater good and others could involve inadequate selection of sectors and rent seeking.

Explaining which outcome or how a positive outcome can be achieved in the resources and development discourse has been a difficult political and economic policy question. Specific institutional capacity development strategies may be targeted, but the sustainability of any positive outcome is often questionable in politically fragile states, where reversing to negative outcomes is more likely. Chang and Lebdioui (2020) suggest that resource-rich developing countries may not need to wait but initiate low-risk low-return investments, while at the same time developing institutional capacity through learning by doing, with gradual scaling up of investments. The success of any investment, however, is still influenced by the type of political foundation underpinning the institutional context. This begs for a more fundamental political transformation as a foundation from which productive rather than distributive institutions can thrive. According to Savoia and Sen (2020), either independent institutions within the national government such as parliament or an independent and powerful judiciary system may be necessary to limit the powers of political actors and keep institutionalized checks and balances. Laying such a foundation itself is not straight forward but a complex process that may inevitably go through a difficult period.

Constitutional foundations that create independent parliaments or judiciary systems cannot be established or maintained only through formal and informal power dynamics, but also through the involvement of the private sector. Political transformation characterized by a transition to mature and effective institutions is determined by the ‘bargaining power of different types of economic elites, and the nature of the institutional arrangements that characterize state–business relations’ (Pritchett et al., 2018:15). According to these authors, therefore, it is not through targeting a specific institutional development area that structural transformation is achieved. But it is through the interrelationships and combined effects of ‘transnational factors’ such as disruptive technology and price changes, ‘inclusive and pro-growth political settlement’, and the ‘rent space’ such as supporting productive industries and exposing bad rents to competition that occur at the ‘deals space’ (Pritchett et al., 2018:352-353). Businesses play a crucial role in pushing political institutions towards creating a stable and sustained business environment. In the process, constant feedback occurs between the state and market actors, thus correcting negative impacts and preserving and building on improvements in both the political and economic transformations.

Specific institutional capacity would then develop as the chain reaction proceeds constantly, in which the state’s institutional frameworks and organizational structures are refined, and productivity is increased by integrated and interlinked firms, creating high value industries. This is enabled when the state’s autonomous role is combined with ‘embeddedness’ in ties with the private sector as demonstrated in the South Korean experience (Juhász et al., 2023). Given the different roles and expectations of each stakeholder, an ongoing action-oriented dialogue is crucial to foster partnerships, which can drive action and promote accountability (McPhail, 2017). Of course, there is a tacit capability in the effective management of such a complex collaboration, that both public and private sector institutions learn and hone iteratively and constantly.

With respect to the public sector institutions, high level institutional capacity for the pathway from inter-sectoral linkages to positive economic transformation may relate to coordinating policies and functions across government ministries and being well versed with private sector business and investment needs. Various policies that need streamlining towards a common goal relate to trade and industry, mineral and energy resources, economic affairs, public sector enterprises, and science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) and R&D. Goals could include supporting the development of a national economic strategy; facilitating the development of inter-sectoral linkages; encouraging political and macroeconomic stability; catalyzing targeted programs that aim to develop various skills, technology, and infrastructure; facilitating knowledge and technology transfers through local procurement and learning exchanges; and aligning the education and vocational training system with industrialization needs. Both the public and private sector institutions need high level skills in leadership, management, communication, monitoring, evaluation, and the ability to function with integrity, transparency, and accountability.

Private sector institutions refer to organizations representing industry or companies. Examples may include chambers of mines, associations of SMEs, entrepreneurship organizations, cooperatives, and business forums, whose roles range from representing the interests of members in corporate affairs to liaising with governments to foster partnerships and coordination. Some of these could be set up by the private sector (like the Minerals Council of Australia) or sponsored by government. An example is the USA’s Advanced Manufacturing Institutes set up during the Obama administration as state sponsored institutes aiming to support business network connectivity, enhance capacities, and develop technology and workforce across the country (Aiginger & Rodrik, 2020). A study by the World Economic Forum (2016) involving a global multi-stakeholder survey found that strategic coordination is not only needed among public sector entities, but also between, for example, companies in the mining sector and those in other sectors such as infrastructure, so that complementary efforts are joined together for better efficiency. As well as representation and liaison, the role of private sector institutions may also involve monitoring and evaluation of performance, reporting, transparency and accountability, and compliance to corporate rules and government regulations.

Conclusion

In principle, economic linkages based on the extractive sector can be at the centre of broad-based diversification for structural transformation. However, existing approaches have either failed to capture the economic linkage benefits or the progress made has been largely within the sector rather than developing diversified economic activities such as manufacturing. Modern and future economic complexities demand multiple factors to work, including market availability and efficiency as well as regulatory and incentive-based interventions by an entrepreneurial state. In this article, we sought to explore how these complexities can be navigated by matching the centripetal force of the extractive sector with its centrifugal force, and fostering its potential to create inter-sectoral linkages and ‘utilisation content’ for the broad-based structural transformation. The article presented a theoretical model premised on the understanding that positive economic transformation is a slow and gradual process that requires multiple instruments working towards the same direction. A pertinent question that we have attempted to answer is what instruments or approaches can deliver the pathway from inter-sectoral linkages to achieving positive economic transformation.

The Utilization Model developed in this article argues that the sector can provide crucial impetus for countries to develop physical capital, technological, and human capital, enterprise architecture, and financial assets, which can act as diversification levers to upgrade industrial structure and promote positive economic transformation. An important aspect of the Utilization Model is that it frames the pathway from inter-sectoral linkages to positive economic transformation as influenced by the twin nexuses of – minerals and clean energy (as opportunity) and state and market dynamics (as challenge). Therefore, the paper proposes a shift in thinking about achieving positive economic transformation on the back of opportunities presented by the utilization of minerals in the transition to clean production. Crucially, political transformation is a necessary condition for the pathway to positive economic transformation, such that structural transformation policies support diversification by leveraging the utilization streams for industrial upgrading. While laying the foundations for a more fundamental political transformation is complex, productive rather than distributive institutions can thrive through interrelationships and combined effects, and the constant feedback occurring between the state and market actors. During this iterative process, specific areas of institutional capacity can be developed to effectively manage the public and private sector collaborations.

The Utilization Model pushed the analysis of extractive sector-based economic linkages to a broader theoretical underpinning that encompasses economic and political transformations. While this could potentially provoke further thought and have policy implications, future research may build on the theoretical model. Specifically, the model may be tested using a further in-depth case-study analysis in resource-rich economies. Future research may also expand on the Utilization Model particularly exploring the microeconomic and macroeconomic impacts of utilization to develop diversification levers. For example, some analysis indicated relationships between capacity utilization and prices and costs through the changes in output and demand (Corrado & Mattey, 1997). Econometric analysis may be applied to analyse multivariate causalities as the different linkage streams are put in practice to enable the pathway from linkage building to economic diversification. In-depth research is also needed to unpack and measure structural transformation policies that can support the formation and utilization of linkages, and development of diversification levers to achieve positive economic transformation.

References

- Ahrens, J. (2006) ‘Governance in the Process of Economic Transformation’, Private University of Applied Sciences Goettingen, Germany.

- Aiginger, K. and D. Rodrik (2020) ‘Rebirth of Industrial Policy and an Agenda for the Twenty-First Century’, Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 20(2): 189-207. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. H., D. Giurco, N. Arndt, E. Nickless, G. Brown, et al. (2017) ‘Mineral supply for Sustainable Development Requires Resource Governance’, Nature 543(7645): 367-372. [CrossRef]

- Amsden, A. H. (1992) ‘Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization’. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0195076036.001.0001 (accessed 7 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, A. and H.-J. Chang (2019) ‘The Political Economy of Industrial Policy: Structural Interdependencies, Policy Alignment and Conflict Management’, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 48: 136-150. [CrossRef]

- Atienza, M., M. Lufin, and J. Soto (2021) ‘Mining Linkages in the Chilean Copper Supply Network and Regional Economic Development’, Resources Policy 70: 101154. [CrossRef]

- Baines, T., S. Brown, O. Benedettini, and P.D. Ball (2012) ‘Examining Green Production And its Role Within the Competitive Strategy of Manufacturers’, Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 53-87. [CrossRef]

- Blomstrom, M. and A. Kokko (2007) ‘Natural Resources: Neither Curse nor Destiny’. International Trade Discussion Paper no 3804. Centre for Economic Policy Research.

- Bown, C. P. (2023) ‘Industrial Policy for Electric Vehicle Supply Chains and the US-EU Fight over the Inflation Reduction Act’. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper (23-1).

- CCSI (2016) ‘Linkages to the Resource Sector: The Role of Companies, Government and International Development Cooperation’. Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment. https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/sustainable_investment_staffpubs/18 (accessed 24 March 2021).

- Chang, H.-J. (2003) Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective. London: Anthem Press.

- Chang, H.-J. and A. Andreoni (2020) ‘Industrial Policy in the 21st Century’, Development and Change 51(2): 324-351. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-J. and A. Lebdioui (2020) ‘From Fiscal Stabilization to Economic Diversification: A Developmental Approach to Managing Resource Revenues’. WIDER Working Paper 2020/108. Helsinki: The United Nations University.

- Corrado, C. and J. Mattey (1997) ‘Capacity Utilization’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 11(1): 151-167.

- Dietsche, E. (2018) ‘New Industrial Policy and the Extractive Industries’, in T. Addison and A. Roe (eds) Extractive Industries: The Management of Resources as a Driver of Sustainable Development, pp. 137-157. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dietsche, E. (2020) ‘Jobs, Skills and the Extractive Industries: A Review and Situation Analysis’, Mineral Economics 33(3): 359-373. [CrossRef]

- Elhiraika, A. B., G. Ibrahim and W. Davis (2019) Governance for Structural Transformation in Africa. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fessehaie, J. (2012) ‘What Determines the Breadth and Depth of Zambia’s Backward Linkages to Copper Mining? The Role of Public Policy and Value Chain Dynamics’, Resources Policy 37(4): 443-451. [CrossRef]

- Findlay, R. and M. Lundahl (2017) The Economics of the Frontier: Conquest and Settlement. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Franks, D. M. (2020) ‘Reclaiming the Neglected Minerals of Development’, The Extractive Industries and Society 7(2): 453-460. [CrossRef]

- Ge, T., X. Cai and X. Song (2022) ‘How Does Renewable Energy Technology Innovation Affect the Upgrading of Industrial Structure? The Moderating Effect of Green Finance’, Renewable Energy 197: 1106-1114. [CrossRef]

- Gelb (2010) ‘Economic Diversification in Resource Rich Countries’ in Beyond the Curse. USA International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/external/np/seminars/eng/2010/afrfin/pdf/gelb2.pdf (accessed 23 June 2021).

- GOA (2001) ‘Australian Industry Participation National Framework’. A Joint Statement of the Governments of Australia.

- Greefhorst, D., E. Proper, D. Greefhorst, and E. Proper (2011) The Role of Enterprise Architecture. Springer.

- Griffiths, S., B. K. Sovacool, J. Kim, M. Bazilian and J. M. Uratani (2021) ‘Industrial Decarbonization via Hydrogen: A Critical and Systematic Review of Developments, Socio-Technical Systems and Policy Options’, Energy Research & Social Science 80. [CrossRef]

- Grynberg, R. and K. Sekakela (2015) ‘Case Studies in Base Metal Processing and Beneficiation: Lessons from East Asia and SADC Region’. Research Report 21. South african institute of international affairs (SAIIA).

- Halland, H., J. Beardsworth, B. Land and J. Schmidt (2014) Resource financed infrastructure: A Discussion on a New Form of Infrastructure Financing. World Bank Studies. Washington, DC. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M. W. (2014) ‘From Enclave to Linkage Economies? A Review of the Literature on Linkages between Extractive Multinational Corporations and Local Industry in Africa’. DIIS Working Paper 2014:02. Copenhagen: Business School Center for Business and Development Studies.

- Harvie, C. and H.H. Lee (2003) ‘Export-led Industrialisation and Growth: Korea’s Economic Miracle, 1962–1989’, Australian Economic History Review 43(3): 256-286. [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, A. O. (1958) The Strategy of Economic Development. 1st ed. New Haven, US: Yale University Press.

- Hirschman, A. O. (1981) Essays in Trespassing: Economics to Politics and Beyond. Cambridge Eng. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- IEA (2021) ‘The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions: World Economic Outlook Special Report’. OECD Publishing. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions (accessed 20 March 2023).

- Joya, O. (2019) ‘How should Resource-Rich Countries Diversify? Estimating Forward-Linkage Effects of Mining on Productivity Growth’, Economics of transition and institutional change 27(2): 457-473. [CrossRef]

- Juhász, R., N. J. Lane and D. Rodrik (2023) ‘The New Economics of Industrial Policy’. Working Paper No. 31538. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Lall, S. (2013) ‘Reinventing Industrial Strategy: The Role of Government Policy in Building Industrial Competitiveness’, Annals of economics and finance 14(2B): 767-811.

- Lenzen, M. (2003) ‘Environmentally Important Paths, Linkages and Key Sectors in the Australian Economy’, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 14(1): 1-34. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. Y. (2012) New Structural Economics: A Framework for Rethinking Development and Policy. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Lin, J. Y., A. Krueger and D. Rodrik (2011) ‘New Structural Economics: A Framework for Rethinking Development [with Comments]’, The World Bank research observer 26(2): 193-229. [CrossRef]

- McKinsey Global Institute (2013) ‘Reverse the curse: Maximizing the Potential of Resource-Driven Economies’. McKinsey & Company (December).

- McMillan, M., D. Rodrik and I. Verduzco-Gallo (2014) ‘Globalization, Structural Change, and Productivity Growth, with an Update on Africa’, World Development 63: 11-32. [CrossRef]

- McPhail, K. (2017) ‘Enhancing Sustainable Development from Oil, Gas, and Mining: From an "All of Government" Approach to Partnerships for Development’. WIDER Working Paper, No 2017/120. Helsinki: The United Nations University.

- Morris, M., R. Kaplinsky and D. Kaplan (2012) ‘“One Thing Leads to Another”—Commodities, Linkages and Industrial Development’, Resources Policy 37(4): 408-416. [CrossRef]

- North, D. C. (1990) ‘An Introduction to Institutions and Institutional Change’, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3-10.

- OECD (2023) ‘Gross Domestic Spending on R&D’. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://data.oecd.org/rd/gross-domestic-spending-on-r-d.htm (accessed 26 February 2023).

- Pianta, M. and M. Lucchese (2020) ‘Rethinking the European Green Deal: An Industrial Policy for a Just Transition in Europe’, Review of Radical Political Economics 52(4): 633-641. [CrossRef]

- Pritchett, L., K. Sen and E. Werker (2018) Deals and Development: The Political Dynamics of Growth Episodes’. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

- Rodrik, D. (2007) ‘Industrial policy for the twenty-first century’, One Economics, Many Recipes: Globalization, Institutions, and Economic Growth Globalization, Institutions, and Economic Growth: Princeton University Press, pp. 99-152.

- Savoia, A. and K. Sen (2020) ‘The Political Economy of the ‘Resource Curse’: A Development Perspective’. WIDER Working Paper 2020/123. Helsinki: The United Nations University.

- Schultze, C. L. (1983) ‘Industrial Policy: A Dissent’, The Brookings Review 2(1): 3-12.

- Singer, H. W. (1950) ‘The Distribution of Gains between Investing and Borrowing Countries’, The American Economic Review 40(2): 473-485. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1818065.

- Stone, S., J. Messent and D. Flaig (2015) ‘Emerging Policy Issues: Localisation Barriers to Trade’. OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 180. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Thomashausen, S. and G. Ireland (2015) ‘Shared-use Mining Infrastructure in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and Opportunities’. Mining Law Committee Newsletter. https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1127&context=sustainable_investment_staffpubs (accessed 12 December 2022).

- United Nations (2015) ‘The Paris Agreement on Climate Change’. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed 20 March 2023).

- Weiss, J. (2013) ‘Industrial Policy in the Twenty-First Century: Challenges for the Future’, in Szirmai, A., W. Naudé and L. Alcorta (eds.) Pathways to Industrialization in the Twenty-First Century: New Challenges and Emerging Paradigms. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Weldegiorgis, F. S., E. Dietsche and S. Ahmad (2023) ‘Inter-Sectoral Economic Linkages in the Mining Industries of Botswana and Tanzania: Analysis Using Partial Hypothetical Extraction Method’, Resources 12(7): 78. [CrossRef]

- Weldegiorgis, F. S., E. Dietsche and D.M. Franks (2021) ‘Building Mining’s Economic Linkages: A Critical Review of Local Content Policy Theory’, Resources policy 74: 102312. [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, L., O. Therkildsen, L. Buur and A.M. Kjar (2015) ‘The Case for Economic Transformation and Industrial Policy’, The Politics of African Industrial Policy pp. 37-59.

- World Economic Forum (2016) ‘Mineral Value Management – A Multidimensional View of Value Creation from Mining’. Responsible Mineral Devepolment Initiative.

- Zou, C., J. Li, X. Zhang, X. Jin, B. Xiong, et al. (2022) ‘Industrial Status, Technological Progress, Challenges, and Prospects of Hydrogen Energy’, Natural Gas Industry B 9(5): 427-447. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).