Submitted:

28 November 2023

Posted:

29 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Institutional Logics

2.2. Hospital Accreditation as an Institutional Standard

2.3. Institutional Logics Constituting the Hospital Accreditation Process

2.4. How do Hospitals Respond to the Hospital Accreditation Process?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Selection of Hospitals, Participants, and Field Research

3.2. Ethical Aspects

3.3. Measures

| Categories | Definitions of dimensions for each category | Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Logics [2,12,23,34] | Professional Logic: Practices based on the performance of the health professional, advocating the quality of services, patient and professional safety, and ensuring reputation and protection. The decline in the quality of care and possible errors in hospital care serve as threatening mechanisms for this logic. | a) Are you in favor of implementing accreditation in the hospital? What improvements can accreditation bring to the hospital? b) Can you name the most significant difficulties you encountered during the accreditation process? c) When choosing to join the Hospital Accreditation program, were there differences of opinions or any conflict between the members of the management? d) What are the main obstacles/problems that the hospital faced in achieving this adoption during the process? |

| Market Logic: Focus on the organization's financial performance and status in the market in which it operates. Profit and organizational advancement are the main objectives. The main threatening mechanisms are poor financial results, decreased performance, operational efficiency, and increased costs. | ||

| Goals of Adoption [19,46] | Legitimacy: Focus on obtaining greater acceptance, respect, and status by stakeholders, involving customers, suppliers, and competitors. | a) When did the institution decide to adopt Hospital Accreditation in the Hospital? b) What do you understand as Hospital Accreditation? How would you define it? c) For what reasons was it decided to adopt Hospital Accreditation? Were there other options? d) Why do you consider Hospital Accreditation Important for the Hospital? e) What did the institution hope to achieve by adopting Hospital Accreditation? |

| Efficiency: The organization's primary focus is to improve the technical aspect of the activity it carries out, such as reducing costs, improving procedures, and increasing productivity, among others. | ||

| Strategic Responses [19,20,21,22] | Conformity: The hospital fully adopts the practices established by the Hospital Accreditation Program, remaining faithful to the precepts and protocols required even after certification. | a) Were all requirements strictly met, or could they be met with alternative methods? b) After obtaining certification, were all processes maintained? c) When the hospital is reassessed, what difficulties are encountered? d) Do you believe that everyone in your sector meets all the standards required by accreditation daily? e) If you were visited by an evaluator today, do you think the hospital would be accredited again? |

| Non-conformity: The hospital mostly rejects the practices established by the Hospital Accreditation program, maintaining only those already practiced or having less impact than competing logics. | ||

| Customization: The hospital organization mainly adopts the practices established by the Hospital Accreditation program but with modifications aimed at adapting them to the real needs of the hospital. | ||

| Nature of Demands [14,23,30] | Origin in the Means: When the nature of the demands originates in the means, these conflicts occurred during the accreditation process, that is, in their implementation and reproduction within the organization. | a) What are the main obstacles/problems that the hospital faced in achieving this adoption during the process? b) For what reasons was it decided to adopt Hospital Accreditation? Were there other options? c) Who was the decision made by? |

| Origin in Goals: When the source is located in the goals, these are actions contrary to the decision to adopt accreditation; the obstacles are located in the decision-making phase before implementation. |

3.4. Categorization of Interview Excerpts

3.5. Analytical Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Institutional Logics

"It is a methodology in which it evaluates healthcare institutions to determine whether they comply with the requirements of the chapters of the accreditation manual aimed at patient safety and improvement of the organization." (CBA Assessor)

"He has a spreadsheet that has to give the grades. But the spreadsheet is exactly the manual. So that's his instrument. The grade is zero, five or ten. So, there are things that they point out." (Hospital manager C)

"The biggest difficulty is the engagement of the medical staff. First place because they think it already has quality. It is challenging for the physician to recognize and assume it needs improvement. So, scientific evidence shows that physicians are the last to incorporate these procedures. Still, when he arrives, the entire institution has already moved towards this." (Hospital manager B)

"The biggest difficulty was aligning the activities I had to do with those of other professionals. Sometimes we depended on others to complete our part, and that got in the way a little." (Nurse 1 from hospital C)

"The most important person here is the patient. I work for the patient. Everything I do is for the patient. So we had to translate this not following the manual." (Hospital manager A)

"In 2001, there was an absurd administrative mess here. Several people were sent away [...] the process stalled for months." (Hospital manager C)

"[...] there was a period when they needed to make changes in my sector, and this required a lot of expense, which was not authorized immediately, and the process was stopped for a while until the hospital fulfilled the requirements [...]" (Nurse 2 at Hospital C)

4.2. Adoption Objectives

"The Organization sought to improve the performance of its professional processes and adopt a certification model recognized as efficient in its purpose of offering quality and safety in healthcare provision." (Hospital manager B)

"The hospital where I work has always valued providing quality medical care that exceeds patients' expectations." (Hospital manager B)

"It is a voluntary evaluation method, where a health institution, for example, a hospital, agrees to submit its administrative processes and assistance to the standards of a manual if, once the required conformity is achieved, it is given a seal that determines it as having a quality and safety program for patients that positively differentiates it from its peers." (Hospital manager B)

"He [the patient] sees it but doesn't understand. So, I think the system lacks information [...] many find it strange to wear bracelets, and even complain. Still, they don't know that an accreditation protocol increases safety and quality of care." (Hospital manager A)

4.3. Strategic Responses

"[...] in my routine, I had no difficulty in [making] many changes, especially because, when I was admitted, it was at the same time that accreditation was being implemented." (Physiotherapist at hospital B)

"[…] there's no way you can make up everything. You have to have an organized process. Now... it's logical that, after the visits pass, you give it a little time, right? Well... you can't be with everyone all the time, so it's challenging to maintain it. People are confined and tend to form small relationships, so you always have to keep working." (Hospital manager A)

"Believing is very difficult. But it is ten times more difficult to sustain. We lose processes and recover them all the time. We have to be sensitive and aware of understanding when we lose the process. Losing, everyone loses, happens. You must see if you are missing a vital process impacting some outcome. It isn't easy to sustain. Conquering is difficult, but it is not the most difficult." (Hospital manager D).

"[...] there was a period when they needed to make changes in my sector, which required greater investment, which was not authorized immediately, and the process was stopped until the hospital fulfilled the requirements." (Nurse 1 of the hospital A)

4.4. Nature of Demands

"So, halfway through, the manager changed. Then until that [new] manager understood, bought into the process... there were several elections along the way... changing care leadership, changing nursing management... then there is a discontinuity, a break in the process..." Hospital manager C)

"Then, shortly afterward, José Serra came to the Ministry of Health [who had guidance for certification by ONA], and they forced us to do ONA. They made a pact with the ONA. So, we were evaluated. The CBA itself did ONA. So, they made visits through ONA and were there. For several reasons, we think the CBA is much better than the ONA. Then, when the government changed, and it no longer needed to be ONA, we went back to JCI, and soon after, we scheduled the visit and ended up getting accreditation later through CBA." (Hospital manager C)

"So, the ONA case was more external pressure? (Researcher 1) Yes. Because otherwise, we wouldn't have changed. So, in this item, change of direction, and so, there were days when there were 29 auditors, we were unable to work. So, it was a very troubled period." (Hospital manager D).

"The manual changed last year, and I think next year will be calmer. But like this: many of the things so-and-so stopped doing. With indicator and stopped doing it!? When you think you're almost there... you have to recover. So it's an ant and systematic work. It demands a certain organization [...]" (Hospital manager A)

"For example, I saw a hospital that had been ISO-certified for eight years. When they entered the accreditation process, they already had structured documentation. But it still took them almost three years to achieve accreditation. Because there is much more detail about patient care and not necessarily with documentation, I saw an institution that took nine years. But with great difficulty." (ONA Appraiser)

"The ones I worked with achieved [accreditation]. I started Three particular ones from the first day working; one took two and a half years; the other 3 and a half; and the other 3 years; and the three did it. I started the process with this audience and stayed there for seven years. But then I left, and it took them another two years or so, and then they managed to do it. But it is a public institution." (CBA Appraiser)

"Over time, you will say that there was no resistance... of course, there was one here and there, but as it was the Management's will, and we said it was something important, people understood. So, decoding that this will bring improvement to the quality of patient care is important. So, of course, today, when we visit, there is no longer any stress... there was already stress. My God, how is this? This no longer exists because it is already part of everyday life." (Hospital manager A)

"Accreditation is sometimes seen as a bargain. If I believe, then I want it. You don't have to want anything! So when we decoded it for them, that what the person comes to see is what we have to do." (Hospital manager A)

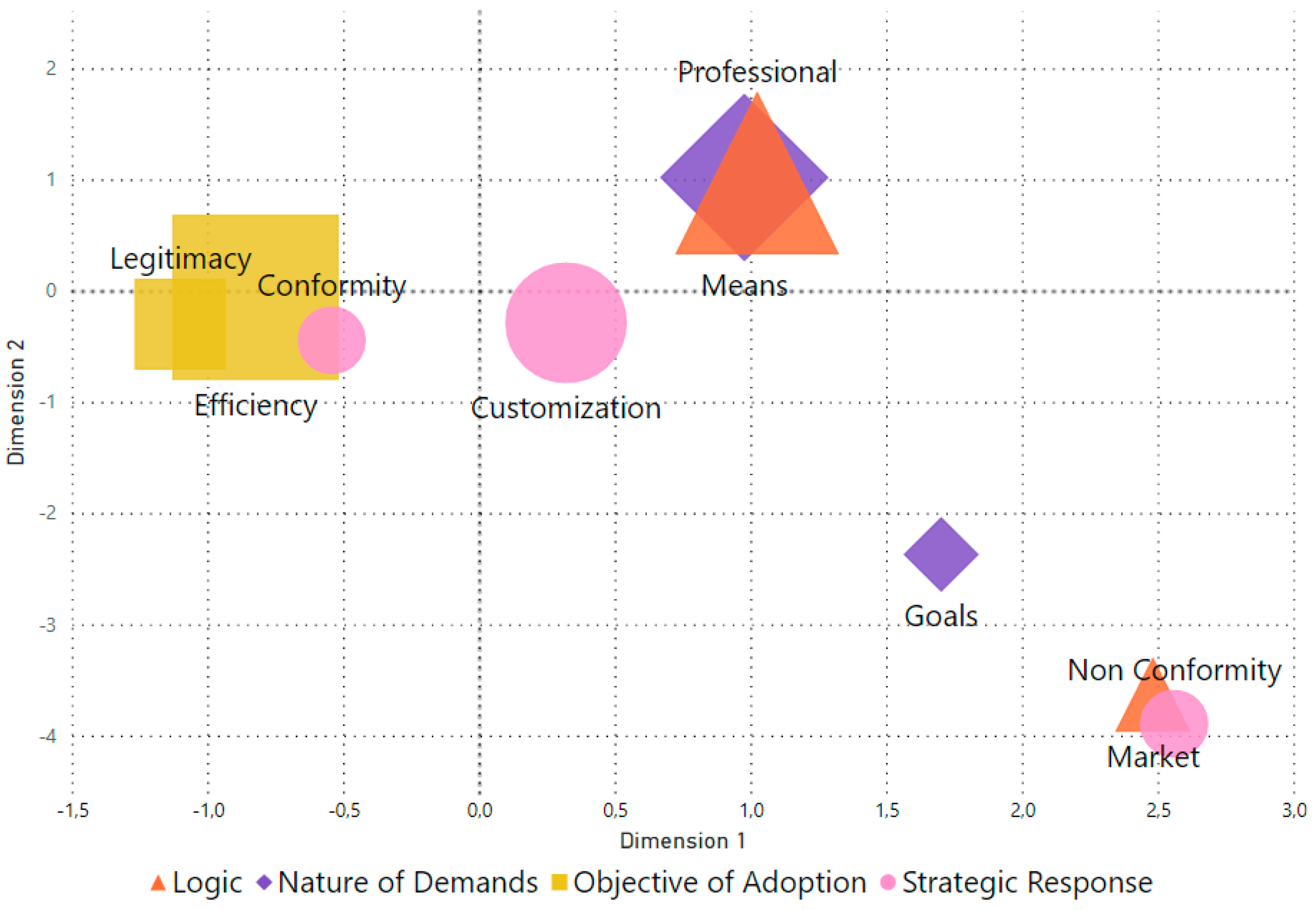

4.5. The Convergence of Logics, Demands, Objectives and Responses

5. Discussion

"We don't put a lot of bosses in these groups, sometimes we have to, because it's not happening, because the boss isn't doing things." (Hospital manager C)

"The mobility of professionals (made it difficult)... so, not necessarily physicians. There is always in the administration: "Ah, the physicians... [referring to the resistance of these professionals]" (Hospital manager D)

"We only stopped the process when we had to postpone scheduling the visit for evaluation, as in the last one, we had many adjustments pending that required a huge expense. This took a while to be approved and put into practice." (Hospital manager D)

"Belief is not cheap. It's not cheap because it involves royalties that have to be paid for the methodology. It involves paying international evaluators who earn, which comes with everything paid for. Well... when we have a problem with the budget, this interrupts the process." (Hospital manager C)

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anthony DL, Appari A, Johnson ME. Institutionalizing HIPAA Compliance. J Health Soc Behav. 2014, 55, 108–124.

- Conceição A, Picoito C, Major M. Implementing an hospital accreditation programme in a context of NPM reforms: Pressures and conflicting logics. Public Money & Management. 2022, 1–8.

- Corrêa J, Turrioni J, Mello C, Santos A, da Silva C, de Almeida F. Development of a System Measurement Model of the Brazilian Hospital Accreditation System. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018, 15, 2520.

- Mansour W, Boyd A, Walshe K. The development of hospital accreditation in low- and middle-income countries: a literature review. Health Policy Plan. 2020, 35, 684–700.

- Mosadeghrad, AM. Hospital accreditation: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Int J Healthc Manag. 2021, 14, 1597–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jardali F, Jamal D, Dimassi H, Ammar W, Tchaghchaghian V. The impact of hospital accreditation on quality of care: perception of Lebanese nurses. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007, 20, 363–371.

- de Oliveira JLC, Gabriel CS, Fertonani HP, Matsuda LM. Management changes resulting from hospital accreditation. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2017, 25.

- Brubakk K, Vist GE, Bukholm G, Barach P, Tjomsland O. A systematic review of hospital accreditation: the challenges of measuring complex intervention effects. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015, 15, 280.

- Greenfield D, Braithwaite J. Health sector accreditation research: a systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2008, 20, 172–183.

- Cain, CL. Agency and Change in Healthcare Organizations: Workers’ Attempts to Navigate Multiple Logics in Hospice Care. J Health Soc Behav. 2019, 60, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland R, Alford R. Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices, and institutional contradictions. In: Powell WW, DiMaggio PJ, editors. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. p. 232–63.

- Thornton PH, Ocasio W, Lounsbury M. The Institutional Logics Perspective. Oxford University Press; 2012.

- Andersson T, Liff R. Co-optation as a response to competing institutional logics: Professionals and managers in healthcare. Journal of Professions and Organization. 2018, 5, 71–87.

- Cappellaro G, Tracey P, Greenwood R. From Logic Acceptance to Logic Rejection: The Process of Destabilization in Hybrid Organizations. Organization Science. 2020, 31, 415–438.

- Kodeih F, Greenwood R. Responding to Institutional Complexity: The Role of Identity. Organization Studies. 2014, 35, 7–39.

- Kyratsis Y, Atun R, Phillips N, Tracey P, George G. Health Systems in Transition: Professional Identity Work in the Context of Shifting Institutional Logics. Academy of Management Journal. 2017, 60, 610–641.

- Pouthier V, Steele CWJ, Ocasio W. From Agents to Principles: The Changing Relationship between Hospitalist Identity and Logics of Health care. p. 203–41.

- Reay T, Goodrick E, Casebeer A, Hinings CR (Bob). Legitimizing new practices in primary health care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2013, 38, 9–19.

- Yang C-W, Fang S-C, Huang W-M. Isomorphic pressures, institutional strategies, and knowledge creation in the health care sector. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007, 32, 263–270.

- Gray CS, Berta W, Deber R, Lum J. Organizational responses to accountability requirements. Health Care Manage Rev. 2017, 42, 65–75.

- Oliver, C. Strategic Responses to Institutional Processes. The Academy of Management Review. 1991;16:145.

- Silva BN Da, Abbas K, Crubellate JM. Lógicas Institucionais na Mensuração e Gestão de Custos em Hospitais Acreditados. Contabilidade Gestão e Governança. 2021, 24, 349–369.

- Pache A-C, Santos F. When Worlds Collide: The Internal Dynamics Of Organizational Responses To Conflicting Institutional Demands. Academy of Management Review. 2010, 35, 455–476.

- Riessman, CK. Strategic uses of narrative in the presentation of self and illness: A research note. Soc Sci Med. 1990, 30, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland R, Mohr JW, Roose H, Gardinali P. The institutional logics of love: measuring intimate life. Theory Soc. 2014, 43, 333–370.

- Besharov ML, Smith WK. Multiple Institutional Logics in Organizations: Explaining Their Varied Nature and Implications. Academy of Management Review. 2014, 39, 364–381.

- SKELCHER C, SMITH SR. Theorizing hybridity: institutional logics, complex organizations, and actor identities: the case of nonprofits. Public Adm. 2015, 93, 433–448.

- Alford R, Friedland R. Powers of theory: Capitalism, the State, and democracy. Cambridge University Press; 1985.

- Thornton PH, Ocasio W. Institutional Logics. In: The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2008. p. 99–128.

- Pache A-C, Santos F. Inside the Hybrid Organization: Selective Coupling as a Response to Competing Institutional Logics. Academy of Management Journal. 2013, 56, 972–1001.

- Shea CM, Turner K, Albritton J, Reiter KL. Contextual factors that influence quality improvement implementation in primary care: The role of organizations, teams, and individuals. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018, 43, 261–269.

- Ruef M, Scott WR. A Multidimensional Model of Organizational Legitimacy: Hospital Survival in Changing Institutional Environments. Adm Sci Q. 1998, 43, 877.

- Westphal JD, Gulati R, Shortell SM. Customization or Conformity? An Institutional and Network Perspective on the Content and Consequences of TQM Adoption. Adm Sci Q. 1997, 42, 366.

- Rossoni L, Poli IT, Fogliatti de Sinay MC, Aguiar de Araújo G. Materiality of sustainable practices and the institutional logics of adoption: A comparative study of chemical road transportation companies. J Clean Prod. 2020, 246.

- Scott, WR. Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests. SAGE; 2008.

- Borowska M, Religioni U, Augustynowicz A. Patients’ Opinions on the Quality of Services in Hospital Wards in Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 20, 412.

- Quartz-Topp J, Sanne JM, Pöstges H. Hybrid practices as a means to implement quality improvement: A comparative qualitative study in a Dutch and Swedish hospital. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018, 43, 148–156.

- Feldman LB, Gatto MAF, Cunha ICKO. História da evolução da qualidade hospitalar: dos padrões a acreditação. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem. 2005, 18, 213–219.

- Alonso LBN, Droval C, Ferneda E, Emidio L. Acreditação hospitalar e a gestão da qualidade dos processos assistenciais. Perspectivas em Gestão & Conhecimento. 2014, 34–49.

- Rossoni L, Teixeira RM. A interação dos relacionamentos com os recursos e a legitimidade no processo de criação de uma organização social. Cadernos EBAPEBR. 2008, 6, 1–19.

- Scott, WR. Health care organizations in the 1980s: The convergence of public and professional control systems. Organizational environments: Ritual and rationality. 1983.

- Scott, WR. Institutional change and healthcare organizations: From professional dominance to managed care. University of Chicago press; 2000.

- Mintzberg, H. Understanding Organizations... Finally!: Structuring in Sevens. Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2023.

- Scott, WR. Lords of the Dance: Professionals as Institutional Agents. Organization Studies. 2008, 29, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, MC. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. The Academy of Management Review. 1995, 20, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer JW, Rowan B. Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. American Journal of Sociology. 1977, 83, 340.

- ONA. Manual brasileiro de acreditação hospitalar. ONA; 2014.

- Mohr JW, White HC. How to model an institution. Theory Soc. 2008, 37, 485–512.

- Breiger RL, Mohr JW. Institutional Logics from the Aggregation of Organizational Networks: Operational Procedures for the Analysis of Counted Data. Comput Math Organ Theory. 2004, 10, 17–43.

- Flick, U. An introduction to qualitative research. 2022.

- Yin, R. Case study research: Design and methods. Sage; 2013.

- Eisenhardt KM, Graebner ME. Theory Building From Cases: Opportunities And Challenges. Academy of Management Journal. 2007, 50, 25–32.

- Reay T, Jones C. Qualitatively capturing institutional logics. Strateg Organ. 2016, 14, 441–454.

- Eisenhardt KM, Graebner ME, Sonenshein S. Grand Challenges and Inductive Methods: Rigor without Rigor Mortis. Academy of Management Journal. 2016, 59, 1113–1123.

- Cunliffe AL, Alcadipani R. The Politics of Access in Fieldwork. Organ Res Methods. 2016, 19, 535–561.

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2019.

- Weber K, Patel H, Heinze KL. From Cultural Repertoires to Institutional Logics: A Content-Analytic Method. 2013. p. 351–82.

- Krippendorff, K. The Reliability of Generating Data. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2022.

- Oleinik, A. Mixing quantitative and qualitative content analysis: triangulation at work. Qual Quant. 2011, 45, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamenkov, G. Recommendations for improving research quality: relationships among constructs, verbs in hypotheses, theoretical perspectives, and triangulation. Qual Quant. 2023, 57, 2923–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco G, Di. Multiple correspondence analysis: one only or several techniques? Qual Quant. 2016, 50, 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2002.

- Weise A, Büchter RB, Pieper D, Mathes T. Assessing transferability in systematic reviews of health economic evaluations – a review of methodological guidance. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022, 22, 52.

- Hays DG, McKibben WB. Promoting Rigorous Research: Generalizability and Qualitative Research. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2021, 99, 178–188.

- Tsang EWK. Generalizing from Research Findings: The Merits of Case Studies. International Journal of Management Reviews. 2014, 16, 369–383.

- de Oliveira JLC, Matsuda LM. Disqualification Of Certification By Hospital Accreditation: Perceptions Of Professional Staff. Texto & Contexto - Enfermagem. 2016, 25.

- de Sousa Vilela G, Ferraz CMLC, de Araújo Moreira D, Brito MJM. Expressões da ética e do di stresse moral na prática do enfermeiro intensivista. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem. 2021, 34.

- Lewis K, Hinchcliff R. Hospital accreditation: an umbrella review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2023, 35.

- Arman R, Liff R, Wikström E. The hierarchization of competing logics in psychiatric care in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Management. 2014, 30, 282–291.

- Xing Y, Liu Y, Lattemann C. Institutional logics and social enterprises: Entry mode choices of foreign hospitals in China. Journal of World Business. 2020, 55, 100974.

- Tolbert PS, Zucker LG. Institutional Sources of Change in the Formal Structure of Organizations: The Diffusion of Civil Service Reform, 1880-1935. Adm Sci Q. 1983, 28, 22.

| Logic | Market | Professional |

|---|---|---|

| Guidance | Focuses on business strategies, market competition, and return on investment. | Based on norms and standards established by professional health associations and bodies. |

| Main Emphasis | Maximizing operational efficiency and financial profitability. | Providing high-quality healthcare based on best practices and professional standards. |

| Motivation | Obtaining profit, optimizing resources, and growing the market. | Commitment to professional ethics, continuous improvement in the quality of care, and patient well-being. |

| Threats | Increased costs and loss of customers. | Reduction in the quality of services and professional malpractice. |

| Basis of authority | Owners, investors and managers. | Professionals with the most outstanding technical and scientific reputations, especially physicians and nurses. |

| Source of Legitimacy | Position of the hospital in the market compared to other competitors. | Status of the hospital in the professional community, available resources, and structure quality. |

| Performance Measurement | Based on financial indicators such as profit margins, revenue, and market share. | Based on quality indicators, patient satisfaction, and adherence to professional standards. |

| Decision Making | Considerations of efficiency, competition and financial return often guide strategic decisions. | Physicians and healthcare professionals frequently make clinical and operational decisions to meet patient needs best. |

| Organizational structure | Organizational structure is often oriented toward management, finance, and operations functions. | Organizations are often structured around medical specialties and multidisciplinary teams. |

| Relationship with Patients | Attention to customer satisfaction, attracting and retaining patients, and maximizing the customer life cycle. | Focus on providing high-quality care and building trusting relationships with patients. |

| Regulation | Subject to government regulations, including compliance with health laws and healthcare regulations. | Subject to professional regulations, standards of practice, and healthcare licensing bodies. |

| Underlying Logic | Managerial | Healthcare |

| Hospital, Nature, Time of Foundation and Accreditor | Interviewed | Number of Interviews | Total Recording Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (Private), 18 years old, ONA | Manager | 4 | 236 minutes |

| Physician | 2 | 54 minutes | |

| Nurse | 2 | 55 minutes | |

| Nurse | 3 | 41 minutes | |

| B (Private), 86 years old, CBA | Manager | 4 | 190 minutes |

| Physician | 1 | 25 minutes | |

| Physiotherapist | 2 | 74 minutes | |

| Nurse | 1 | 22 minutes | |

| C (Public), 43 years old, ONA | Manager | 5 | 274 minutes |

| Physician | 2 | 49 minutes | |

| Nurse | 1 | 81 minutes | |

| Nurse | 3 | 171 minutes | |

| D (Public), 116 years old, CBA | Manager | 4 | 212 minutes |

| Physician | 1 | 12 minutes | |

| Physician | 2 | 44 minutes | |

| Nurse | 2 | 87 minutes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).