1. Introduction

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), such as cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes, were, in the pre-COVID-years, responsible for over 70% of deaths globally [

1]. In high-income countries NCDs are overrepresented in people with lower socio-economic positions (i.e. those with lower education, occupational class or income [

2]), thereby limiting health equality. In 2016, 90% of deaths in the Netherlands, a country in Northern-Europe, were attributed to NCDs. About 11% of deaths are premature, between the age of 30 and 70 years old, and caused by NCDs [

3]. Although both NCD prevention and control are essential response strategies for countries at all income levels, NCD prevention is more cost-effective than control [

4].

With respect to NCD prevention, an unhealthy diet is one of the four main modifiable, behavioral risk factors underlying NCDs [the others being: tobacco use, physical inactivity and harmful use of alcohol] [

1]. The 2015 Global Burden of Disease study calculated that diets: 1. high in sodium, 2. low in vegetables, 3. low in fruit, 4. low in whole grains, 5. low in nuts and seeds, and 6. low in seafood omega-3, each accounted for more than 1% of global disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs). This stresses the importance of promoting both the reduction of sodium intake and the increase in intake of vegetables, fruit, whole grains, nuts, seeds, and seafood omega-3 through interventions such as education, subsidies and other evidence-based strategies [

5]. This is fully in line with the World Health Organization’s (WHOs) 2013-2020 global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases aiming at “reducing the preventable and avoidable burden of morbidity, mortality and disability due to noncommunicable diseases by means of multisectoral collaboration and cooperation at national, regional and global levels, so that populations reach the highest attainable standards of health and productivity at every age and those diseases are no longer a barrier to well-being or socio-economic development” [

6]. Their overarching principles for achieving this goal include amongst others: 1) life-course approach; 2) equity-based approach; 3) multisectoral action; 4) empowerment of people and communities; and 5) evidence-based strategies.

When zooming in on these principles, the following gaps and opportunities are identified. Firstly, NCD prevention often focuses on either the first 1000 days or on the general adult population while adolescents have been overlooked [

7]. This neglect has been postulated to be the result of a lack of data about this target group and of evidence of what policies, strategies and interventions work in this target group [

8]. However, adolescence is a unique window of opportunity for the development of autonomous health promoting behavior and for limiting behavioral risk factors. Their cognitive function is larger than during childhood, the period with even larger brain plasticity, and their ability for change might be even larger than during adulthood [

9]. Crone and Dahl [

10] define adolescence as “a phase of development characterized by flexible adaptation to a rapidly changing social landscape marked by changes from dependency to autonomy and individuality”. Not only their social landscape, but also their food environment rapidly changes [

7]. In 2019 in the Netherlands, 67% of secondary schools had at least one food outlet within five minutes walking. Schools in low-income neighborhoods have a higher chance of having at least one nearby food outlet than schools in high-income neighborhoods [

11].

Targeting adolescents in pre-vocational schools aligns with the equity-based approach, the above-mentioned second principle, as these students often reside in and attend schools within low-income neighborhoods. They deserve heightened attention. As a result of intergenerational effects, they are more susceptible to poorer health from conception through childhood [

12]. Investment in their health would also be a chance to break this intergenerational cycle and propel them, and eventually their offset, into a better position in life.

Changing the food system of adolescents requires a multisectoral approach, the third principle, as also proposed in WHO’s Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!) [

13]. A multisectoral approach requires commitment of all parties, including the target group. Adolescents themselves can be peer researchers or citizen scientists for understanding the “present”, identifying levers for “change” and for cocreating their “future”. This approach has been successfully applied to address upstream NCD risk factors in urban low and middle-income contexts [

14].

Giving adolescents a voice would not only empower them, the fourth principle, their brain development also demands such an approach. Adult feedback is far less effective for changing their behavior than is peer feedback. Also, under the right circumstances - such as when highly motivated - their problem-solving skills may well be better than those of adults as they have a large capacity to diverge during a creative process [

10]. Don’t tell them what to do, but ask them for solutions.

We applied this approach for the design of a so-called social innovation - the Food Boost Challenge. The Dutch Advisory Council for Science and Technology Policy defines social innovation as “new solutions that simultaneously meet a societal need and introduce or improve capacities and relationships and a better use of resources”. They state that “social innovations are good for society and increase its capacity for action” [

15]. As a first use case, we selected two of the above-mentioned six dietary factors which favorably affect DALY and contribute to the prevention of NCDs, namely promoting the intake of vegetables and fruit. Very few people aged 1-79 year-old in the Netherlands consume the recommended daily minimum of 250 grams of vegetables and 200 grams of fruit (i.e., 6% and 15%, respectively). In the last national food consumption survey, adolescents, aged 14-18 year-old, daily consumed on average about 100 grams of vegetables and 100 grams of fruit with 1% reaching the recommendation for vegetables and 7-10% that of fruit (boys-girls, respectively) [

16]. So, there is sufficient room for improvement in the intake of vegetable and fruit products among adolescents. To our knowledge, there’s no evidence-based strategy – the fifth principle – in the Netherlands nor elsewhere, focusing on stimulating the intake of vegetable and fruit products among pre-vocational adolescents, 12-20 years old. In this paper, we describe the design of the social innovation called Food Boost Challenge (FBC) that has been developed for this purpose. Additionally, we present the initial results and key drivers for its success.

2. Materials and Methods

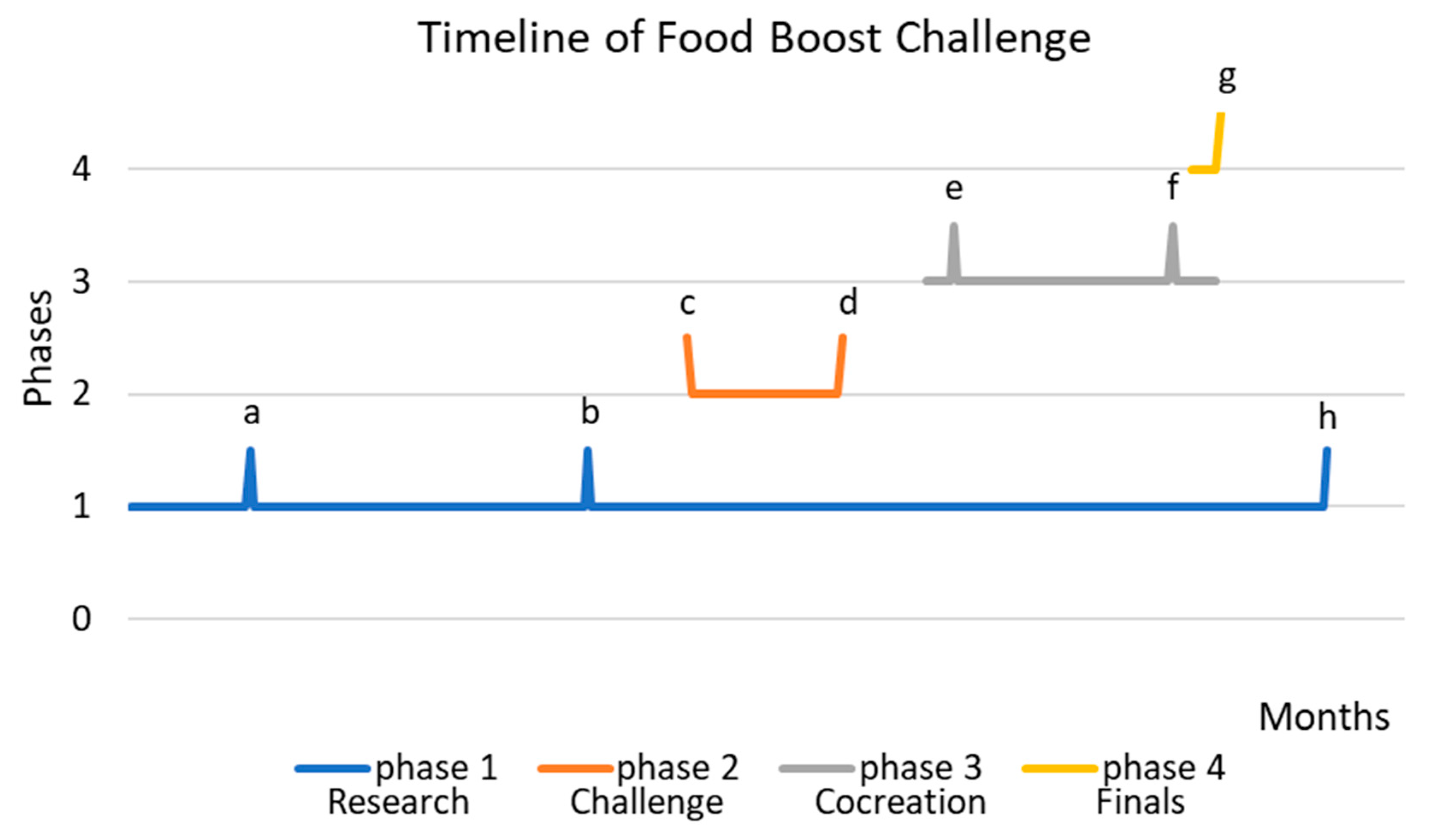

The design of the Food Boost Challenge is based on participatory action research. In

Figure 1 a complete timeline of phases and events (

spikes a-h) of the Food Boost Challenge is provided. In February 2021, the founding partners of the Food Boost Challenge, namely Foodvalley NL, HortiHeroes, and The Hague University of Applied Sciences along with Medical Delta Living Lab VIT for Life conceived the Food Boost Challenge for stimulating the intake of vegetable and fruit products among pre-vocational adolescents. Herewith the developmental phase of the Food Boost Challenge was initiated. A swift start was made recruiting partners throughout the whole food system covering adolescent’s ecosystem, aspiring for at least 30 partners. Partners were asked to sign a letter of commitment confirming both a pro rata cash and an in-kind contribution to the FBC. Additional funding was being sought through grant applications. After the initial 150 days of partner recruitment, it was decided to go ahead with the challenge even if no additional grant funding would be acquired. This decision was merely based on immediate buy-in of a wide array of partners supporting both the goal and approach of the Food Boost Challenge. This coincided with the official launch of the Food Boost Challenge in July 2021.

In August 2021, the research phase, phase 1 of the Food Boost Challenge, started (until

spike h,

Figure 1). The aim of this phase was to identify barriers and drivers of adolescents aged 12-20 year-old, for change in consumption of vegetable and fruit products. General research questions were formulated by the research team and partners were offered the opportunity to add specific research questions. Throughout the entire research phase students, scholars and their teachers at research and pre-vocational schools were invited to participate in a variety of intra-curricular projects, preferably using innovative methodologies. There was ample room for engaging as long as their participation contributed towards the above-mentioned aim of this research phase (i.e. stimulating consumption of vegetable and fruit products). We aspired at involving a minimum of 200 students and scholars in this phase. The kick-off meeting for partners was held towards the end of September 2021 (see

Figure 1,

spike a). Goal of this meeting was for partners and core team to meet and connect and for partners to be briefed about what to expect in each phase of the Food Boost Challenge.

Spike b (

Figure 1) refers to the partner meeting in December 2021 during which the initial results of the research phase were shared.

Early in 2022, during a 6-week-long period (see

Figure 1,

spike c for the start and

spike d for the end), students, 16-28 year-old, were challenged to develop innovative ideas into concepts that would increase consumption of vegetable and fruit products among 12-20-yr-olds. Students were reached via the core team’s network, partners, Dutch universities, social media, radio interviews, etc. Concepts had to fit into at least one of four routes: I) innovative technology to stimulate a healthy diet; II) new food products/concepts targeting adolescents; III) hotspots, i.e. physical places and/or events, influencing and improving the experience of F&V-products; IV) new routes to markets, e.g. new channels and/or ways of presenting products. A jury, consisting of members of the core team, reviewed all applications, submitted before the deadline (see

Figure 1,

spike d), looking at: innovativeness, relevance and potential impact, team composition and ambition.

The most promising student teams entered phase 3 of the Food Boost Challenge: the matchmaking and cocreation phase. We aspired at least 50 innovative ideas of which 15 would be selected for participation in phase 3. Shortly before the start of phase 3 (see

Figure 1,

spike e) partner recruitment stopped since new partners would be unable to be matched if entering beyond this moment. See the project website for a complete list of partners [

17]. Phase 3 started with an event. Mid-March 2022 (see

Figure 1,

spike e), all student teams, partners and representatives of the target group met during four rounds of speed dates after which they were matched, based on personal and professional preferences. Newly formed consortia of a student team and 1-2 partners and representatives of the target group subsequently received a professional cocreation training to kickstart their prototyping phase. Throughout this phase these consortia continued to develop and validate their prototypes. Phase 3 also ended with an event. Mid-May 2022 (see

Figure 1,

spike f), all student teams received a professional pitch training after which their pitch was video-taped. This pitch was used for a one-week-period of public voting at the start of phase 4 of the Food Boost Challenge.

Phase 4, which intended to create a national buzz and a boost for a healthy diet among adolescents, ended with the national finals (see

Figure 1,

spike g), a one-day event, during which consortia and partners had a national stage at which prototypes were pitched by the student teams, and experienced by the jury and audience; research findings were shared; and all people present networked. Four prizes were awarded to the student teams during the finals. We aspired at a minimum audience of 100 people during the national finals.

3. Results

In

Table 1 the design of the Food Boost Challenge is summarized, including numbers reached. Most remarkable was the large buy-in for the Food Boost Challenge of partners, teachers, students and scholars. This commitment enabled generation of sufficient funding and knowledge sharing; intra-curricular exposure to the importance of a healthy diet in general and vegetable and fruit products in specific for >2000 scholars; active participation in a quadruple helix project for >200 students. In

Table 2 all pre-set goals are compared with actual achievements. As can be seen five of the seven goals were reached. For one goal, the goal was deliberately lowered. Because not 50 but 25 concepts were submitted, only 10 - not 15 - of those were chosen to enter the match-making and cocreation phase.

Table 3 lists the prototypes pitched at the finals. Apart from the numbers - of partners, students, teams, adolescents - participating, the outcome of this challenge was hard to quantify, however, we do consider the FBC approach to be viable because: 1. most participants enjoyed participation; 2. the FBC approach was adopted in another region in the Netherlands (Food Boost Challenge Limburg); 3. advanced plans, including a submitted grant application, for future editions of the FBC in the Netherlands and abroad were developed; and 4. several partners expressed the desire to continue participating in future editions of the FBC.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we described the design of a social innovation called Food Boost Challenge that has been developed for increasing the intake of vegetable and fruit products in adolescents. In addition to initial results, we also identify key drivers for its success. Results indicate this quadruple helix innovation hits the right notes with all involved. The Food Boost Challenge generated useful insights in what adolescents need for increasing their intake of vegetable and fruit products. Not only have prototypes been developed in all four routes [

18] (see table 3), but some of them already reached the implementation stage. In addition the Food Boost Challenge is a sustainable model as it will be repeated and adopted in other regions and settings in The Netherlands and possibly abroad.

For future editions of the Food Boost Challenge, we encountered areas of improvement, larger potential and research needs. These are discussed using the main learnings 1-6 in table 2 (in a different order). First of all (see table 2, main learning 1), an undisputed aim facilitates the easy identification of opportunities for participation for all involved. We hypothesize the Food Boost Challenge approach could also be applied to promoting other challenging healthy eating behavior such as more sustainable diets or drinking water. It would be interesting to assess if the approach could also be successfully used for achieving goals for other lifestyle and/or health-related aims or even non-health-related challenges.

Although large numbers of students participated within their curricular activities in the research phase (see table 2, main learning 2), the numbers intended for the challenge phase were not met. Student teams participating in this phase did this on a voluntary, extracurricular basis. In our experience, and within the Dutch school system, a curricular nature of activities enables participation of large numbers of students, which also facilitates an equitable approach. However, this may differ from country to country [

21]. For future editions, the focused efforts made for phase 1 - to find smart combinations which allow students to participate in the challenge from within their curriculum – should be extended to the challenge phase (see table 2, main learning 3).

With only 3 out of 25 ideas of insufficient quality for participation in the challenge, we consider the recruitment of student teams and information on the challenge to be adequate [

17]. However, for accelerating innovation, we would recommend incorporating active dissemination of results of the research phase when recruiting students for the challenge phase (see table 2, main learning 6). Even if these results are preliminary. Apart from the events during which research results are shared, other innovative ways of sharing research findings with all involved should be sought. Continuous sharing of bite-sized findings, for example through micro-learning, might be a promising route [

22] resulting in even more innovative ideas, concepts and prototypes. Since the target group is highly active on social media, active sharing of findings through these media should also be explored.

Ultimately, the Food Boost Challenge is designed as an intervention which should increase adolescents’ intake of vegetable and fruit products. Although we conclude that the Food Boost Challenge generated a buzz, the effectiveness on intake and the wider impact has not yet been assessed. Additional funding and research is required to evaluate its impact using a relevant framework such as RE-AIM [

20] (see table 2, main learning 5). In addition, the quantitative effect should be assessed. In order to minimize the research burden on adolescents, within this edition of the Food Boost Challenge, a number of students developed a quick quantitative scan for assessing adolescents’ consumption of vegetable and fruit products. However, development of these tools was hampered because too many adolescents in our population do not yet possess sufficient food literacy skills to accurately and precisely recognize portion sizes of vegetable and fruit products. Even the - often recommended - use of food photos did not sufficiently improve the accuracy of the estimates. Ironically, this underlines the relevance of increasing knowledge and skills of this target group.

A final learning of this first Food Boost Challenge is that this approach was a powerful way of creating a community of a wide variety of partners (see table 2, main learning 4). This is a very good foundation for innovative practice-based research with impact in living labs. However, for achieving actual change in society, we would recommend adding a fifth phase, dedicated to implementation of high-potential prototypes, to the Food Boost Challenge. The exact implications for phase 1-4 and requirements for such a phase 5 should be developed in future editions of the Food Boost Challenge. While most partners in the current edition were satisfied, an implementation phase would provide added value for some of them. With dedicated partner management these and other needs of partners could be identified and met [

23] (see table 2, main learning 4).

In the introduction, we refer to WHO’s aim at reducing NCDs through a combination of overall principles [

6], namely: 1. life-course approach; 2. equity-based approach; 3. multisectoral action; 4. empowerment of people and communities; and 5. evidence-based strategies. We conclude that the design of Food Boost Challenge as described in this paper contributes to these aims and could therefore contribute towards reducing NCDs. In the Food Boost Challenge, we focused on an often overlooked target group, namely adolescents with lower education levels and students which we reached intra-curricularly (principles 1 and 2). A diverse array of partners participated in the Food Boost Challenge, ranging from NGO’s to start-ups, scale-ups and multinationals [

17] (principle 3). During the cocreation phase, consortia were formed, with each consortium comprising a student team, representatives from partners, and members of the target group. Each initial consortium meeting was facilitated by a member of the core team. Consortia were empowered through professional training and actively opening up networks for them. Quite a number of consortia have advanced plans for continuing development of their innovative concepts to increase vegetable and fruit consumption of adolescents. Some of them with their initial consortium partners, some with new business partners. Therefore, we conclude people have been empowered and communities have been strengthened (principle 4). Another example being that some of the activities during which students collaborated with schools in participatory research projects will be continued next academic year, with new generations of students and scholars. For future editions, effectiveness should be monitored in order to grow the evidence-base of the Food Boost Challenge approach as an intervention which enhances the vegetable and fruit intake of adolescents (principle 5). Overall, the Food Boost Challenge approach could transform ideas into actionable measures and shows potential to be adapted to promote various healthy eating behaviors among school students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; methodology, all authors; student research projects, MvL and WS-B; communication and event management, PvH; writing—original draft preparation, MvL; writing—review and editing, WS-B and SIdV; visualization, MvL; supervision, SIdV; project administration, PvH; funding acquisition, WS-B and JMvdH-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received no official funding, but was supported by in-kind contributions of the affiliations of the authors and by cash and in-kind contributions of participating partners (see text for further explanation).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The student research projects were conducted within the context of their intra-curricular school assignments. Therefore, in line with the Dutch “Kwaliteitshandboek Praktijkgericht Onderzoek” ethical review and approval were waived for this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all student teams and partners involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected in the student research projects presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to fact that they are made as part of their studies, i.e. a learning process. The student teams ideas presented in this study are openly available and can be found here

https://www.youtube.com/@FoodBoostChallenge/videos.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to everyone in the Food Boost Challenge community who contributed to this project, including all 34 partners, students, adolescents, and their teachers at schools and universities. We extend our sincere thanks to Fabienne van der Klugt, Fleur Helsloot, Kai Pruiksma, and Annabel van der Plasse, four integral members of the core team, for their significant contributions in perfectly co-organizing all events and communication, in collaboration with the authors of this paper. We also greatly appreciate all efforts of Yvonne van Santen for identifying courses and colleagues willing to participate in the student research projects.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The participating partners had no role in the design of the Food Boost Challenge; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of results; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. Available online: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Mackenbach, J.P. , Rubio Valverde, J., Bopp, M., Brønnum-Hansen, H., Costa, G., Deboosere, P., et al. Progress against inequalities in mortality: register-based study of 15 European countries between 1990 and 2015. Eur J Epidemiol 2019, 34, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. Available online: www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514620 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Nugent, R. , Bertram, M.Y., Jan, S., Niessen, L.W., Sassi, F., Jamison, D.T., et al. Investing in non-communicable disease prevention and management to advance the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet 2018, 391, 2029–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1659–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Patton, G.C. , Neufeld, L.M., Dogra, S., Frongillo, E.A., Hargreaves, D., He, S., et al. Nourishing our future: the Lancet Series on adolescent nutrition. Lancet 2022, 399, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, G.C. , Sawyer, S.M., Santelli, J.S., Ross, D.A., Afifi, R., Allen, N.B., et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, C.E. , Kleibeuker, S.W., de Dreu, C.K.W., and Crone, E.A. Training creative cognition: adolescence as a flexible period for improving creativity. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crone, E.A. , Dahl, R.E.. Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 9, 636–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slob, G.J. Voedselaanbod rondom scholen. Available online: https://wiki.jogg.nl/userfiles/Onderzoek%20Voedingsaanbod%20rondom%20scholen.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Norris, S.A. , Frongillo, E.A., Black, M.M., Dong, Y., Fall, C., Lampl, M., et al. Nutrition in adolescent growth and development. Lancet 2022, 399, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 13. World Health Organization. Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!): guidance to support country implementation. 2017.

- Oni, T. , Assah, F., Erzse, A., Foley, L., Govia, I., Hofman, K.J., et al. The global diet and activity research (GDAR) network: a global public health partnership to address upstream NCD risk factors in urban low and middle-income contexts. Global Health 2020, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Advisory Council for Science and Technology Policy. The power of social innovation. Available online: www.awti.nl/binaries/awti/documenten/adviezen/2014/1/31/de-kracht-van-sociale-innovatie---engels/the-power-of-social-innovation-summary.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Schuurman, R.W.C. , Beukers, M.H., and van Rossum, C.T.M. Eet en drinkt Nederland volgens de Richtlijnen Schijf van Vijf? Resultaten van de voedselconsumptiepeiling 2012-2016, RIVM: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Food Boost Challenge: Recipe for a Healthy Next Generation. Available online: www.foodboostchallenge.nl/?lang=en (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Food Boost Challenge: 1 minute-video pitches of finalist student team ideas. Available online: www.youtube.com/@FoodBoostChallenge/videos (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Food Boost Challenge: 90 second-animated explainer. Available online: https://youtu.be/UTK7J_0eyQk (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Glasgow, R.E. , Vogt, T.M., Boles, S.M.. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public. Health 1999, 89, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, A. , Hartmann, B.S., Larson, R. A Quarter Century of Participation in School-Based Extracurricular Activities: Inequalities by Race, Class, Gender and Age? J. Youth Adolescence 2018, 47, 1299–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Caballero, D. , Castillo-Sarmiento, C.A., Ballesteros-Yánez, I. et al. Microlearning through TikTok in Higher Education. An evaluation of uses and potentials. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hei, M. , and Audenaerde, I. How to Support Co-creation in Higher Education: The Validation of a Questionnaire. HES 2023, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).