1. Introduction

Natural farming (NF) is an agroecological approach that can potentially address multiple agricultural crises attributed to the industrial farming model [

1,

2]. The use of high-cost agrochemicals not only placed farmers in debt but polluted the environment, degraded the soil and affected people’s health adversely. In India, NF is being adopted for its potential to regenerate the soil, increase farmer incomes, enhance food security and enhance resilience to climate change. This paper uses a case study of a natural farming initiative by the north Indian state of Himachal Pradesh to explore how its mechanisms support and benefit small-scale and marginal women farmers. In India, research on agroecology and gender has been limited to NGO reports [

3]. Agarwal’s [

4] significant research on how group farming empowers women did not examine farming practices. An emerging body of literature from Latin American countries bridges agroecological and gender scholarship, but relatively little has been published in English [

5,

6,

7]. There is a need for evidence-based research that explores the processes of change and the impact on women from their perspectives so that the complexities of their day-to-day lives are understood. This paper asks whether state mechanisms in India support women transitioning to NF and whether any transitions open spaces for women to become more empowered in the domestic and social domains.

The paper begins by explaining key concepts in agroecology and women’s empowerment. Exploring the different academic framings and shifts that have taken place within the literature will make evident how agroecology and gender studies share common ground related to justice and equity.

1.1. Agroecology as a socio-political movement for transitions

The first argument the paper makes from the literature is that the concept of agroecology has evolved from that of longstanding traditional practice and science of sustainable farming into a discourse about whole food system transformations and food sovereignty. Currently, multiple agroecology initiatives in India address the fallout from the Green Revolution (GR) technologies. The GR, an industrial model of agriculture comprising hybrid seeds, fertilisers, pesticides, irrigation and mechanisation, was exported from the USA to India in the 1960s. It was resource-intensive, and, in India, it resulted in the marginalisation of small-scale farmers, soil degradation, water depletion, deteriorating human health, loss in biodiversity and farmer indebtedness [

8,

9,

10]. In 2018, the states of Andhra Pradesh and Himachal Pradesh began an ambitious plan to transition all their farmers from conventional chemical farming to NF. NF refers to low-cost regenerative agricultural practices based on ecological principles that do not rely on agrochemicals. Its fundamental principles, delineated by the National Coalition of Natural Farming (NCNF), a network of 400 organisations, are that it is friendly to soil and planet; calls for progressive elimination of synthetic chemicals; views ecosystem services using a landscape approach; includes a diversity of biological approaches and frameworks; is decentralised, friendly to people's institutions, and supports women farmers to have equal spaces in membership and leadership roles. The NCNF aims "to accelerate the practice and policy related to agroecology-based farming in its multiple variants in India" [

11]. That NCNF aims to empower small and marginal farmers with an emphasis on women farmers is particularly significant in India, where 63% of working women work in agriculture within oppressive patriarchal, caste and cultural norms [

12].

Agroecology remains a contested term in its definition and scope. Altieri's well-known description of agroecology as an ecosystem approach that applies ecological concepts and principles to the design and management of sustainable agroecosystems has expanded into increasingly political spaces, using food sovereignty and food justice perspectives to transform food systems [

13,

14]. According to Anderson et al., [

15] (p.13), it comprises a set of production principles: "Adapting to the local environment; building healthy soils rich in organic matter; conserving soil and water; diversifying species, crop varieties and livestock breeds in the agroecosystem over time and space from a landscape perspective; enhancing biological interactions and productivity throughout the system rather than focusing on individual species and single genetic varieties; and minimising the use of external resources and inputs (e.g., for nutrients and pest management)". Some of these principles are common to other ecological or regenerative agriculture techniques, such as conservation or no-till agriculture and organic farming; however, agroecology has acquired a socio-political dimension, which is its key distinguishing feature from other sustainable agricultural practices.

This socio-political dimension was facilitated by the emergence of agroecology as a socio-political movement. In Mexico, the first country where GR was introduced in the 1940s [

9], agroecology gained a social movement aspect. It was here that small farmers, scientists, and activists began their opposition to the agenda of ‘modernisation’, the industrial model of high input and intensive GR technologies and, instead, championed ecologically sound traditional farming practices [

16,

17]. World Trade Organisation rules and the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants that criminalised seed saving and seed exchanges by farmers were viewed as the common enemy by a network of grassroots organisations. In 1992, La Via Campesina, a transnational peasant organisation, proposed an alternative model of agriculture and rural development framed as food sovereignty, subsequently adopted In 2007 by advocates from 80 countries [

17,

18]:

"Food sovereignty includes the right to food - the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through socially just and ecologically sensitive methods. It entails peoples’ right to participate in decision-making and define their own food, agriculture, livestock and fisheries systems. It defends the interests and inclusion of the next generation and supports new social relations free from oppression and inequality between men and women, peoples, racial groups and social classes”.

In 2015, the Declaration of the International Forum for Agroecology was held at Nyéléni, Mali, where participants understood agroecology as a critical element in constructing food sovereignty and developed joint strategies to promote agroecology. The idea of agroecology thus evolved into a multi-scale and transdisciplinary approach to include the science and practice of agroecosystems and socio-political aspects of a movement. In asking for a transition to more sustainable food systems, this approach also asks for a more just society that counters structural oppression, racial capitalism and patriarchy [

15,

20]. Further, Schneider and McMichael [

21] argue that food sovereignty has a significant role as an environmental countermovement needed to resolve ecological crises. It does this by repairing the relationships between people and nature and restoring the ‘epistemic rift’ caused by industrial agriculture, i.e., a rupture in farmers’ knowledge needed for sustainable ecosystems.

The question of how to scale agroecology up and out has become an increasingly important debate in global policy and funding spaces which address food systems, such as UN climate and biodiversity conferences and the UN Food Systems Summit [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Gliessman's five transition levels form a widely used framework to understand how farmers can transition from conventional farming (CF) to an agroecological system [

15]. Gliessman borrowed the first three levels from Hill [

26] focusing on the technical aspects of transitions from CF to fully integrated agroecological systems at level three. He added two further levels to include a broader food system change and food sovereignty (

Table 1).

Although Gliessman’s transition levels represent a stepwise evolutionary process towards food systems transformation, several overlaps and entry points may exist. As was observed in Himachal Pradesh, NF is an example of a Level 3 systems redesign (also noted in Andhra Pradesh [

28]) where some farmers, such as those with established fruit orchards, begin with input substitution using the Palekar formulations. Success with these encourages further experimentation, and farmers transition to the next level. Anderson et al., [

15] argue that a level 3 redesign would be challenging unless farmers are supported by broader structures and relationships such as food markets, reciprocity within the community and wider landscape changes found at levels 4 and 5. In Himachal Pradesh, features of level 4 wider community and food systems change were present: the transitions involved new relationships and forms of social organisation, participatory forms of learning, and communities sharing resources similar to those observed in Andhra Pradesh [

28,

29].

In 2021, concerns that mainstreaming agroecology would deprive it of its political and social underpinnings led to the formation of the Agroecology Coalition to give agroecology a precise meaning [

24]. It adopted the 13 principles of agroecology defined by the High-Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) [

30] of the Committee of World Food Security, which include the ten elements from FAO [

31] and can be related to Gliessman’s transition levels. The first seven principles -1) recycling, 2) input reduction, 3) soil health, 4) animal health and welfare, 5) biodiversity, 6) synergy (managing ecological interactions), and 7) economic diversification - relate to levels 1 to 3. The next six principles relate to whole food systems changes: 8) co-creation of knowledge (embracing local knowledge and global science), 9) social values and diets, 10) fairness, 11) connectivity (between producers and consumers), 12) natural resource governance, and 13) participation.

1.2. The need for a gender focus in agroecology transitions

The second argument this paper derives from the literature is that given the problems with women’s invisibility and subordination [

32], a transition to agroecological farming alone may not be sufficient to overcome the barriers they face. While agroecology’s principles and theoretical underpinnings are based on promoting equity, its practice does not always reflect this [

33,

34]. In agroecology movements that do not promote initiatives specifically for women, women are seen to be present but only as farmers' wives. This was evident in a study of the ZBNF movement in Karnataka, India, despite being led by a grassroots movement [

35]. In instances where a gender focus has been included in agroecology approaches, the findings show enhanced life outcomes and empowerment for women [

36].

Empowerment can be understood as gaining a sense of power to shape the lives we want to live ourselves and the lives of others [

37]. It is generally agreed that empowerment is a multi-dimensional concept where relational power is an essential aspect. It can be expressed through dominating others, resisting transformative change, or generating new possibilities through collaboration. Additionally, what may be experienced as empowering for one woman may not be empowering for another. How interventions change women’s lives depends on their circumstances, the possibilities open to them and what they value [

38,

39]. The process, in essence, is one of self-determination. To understand how changes in power happen, it is helpful to distinguish between different types of power (

Table 2).

The types of power are interlinked and complementary. For example, 'power within' lies at the crux of empowerment and forms the basis of the other categories. In turn, an increase in one's capability to resist 'power over' or enhancement of abilities in the social domain, i.e., 'power with', strengthens the 'power within'. The importance of 'power within' or a woman's self-confidence and self-view is highlighted by Belenky et al., [

42] who argued that a woman's confidence in herself as a thinker and the belief that she is capable of intelligent thought lies at the basis of her ability to make choices for her well-being. These understandings reinforce the need for an intentional equity focus in agroecology efforts. Amartya Sen [

43] (p.125) noted, "the issue of gender inequality is ultimately one of disparate freedoms'. For agroecology to be transformative, a synergistic relationship between agroecology and the feminist movement is essential [

44]. Gender equality and women’s empowerment are considered to be integral to each of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals [

45].

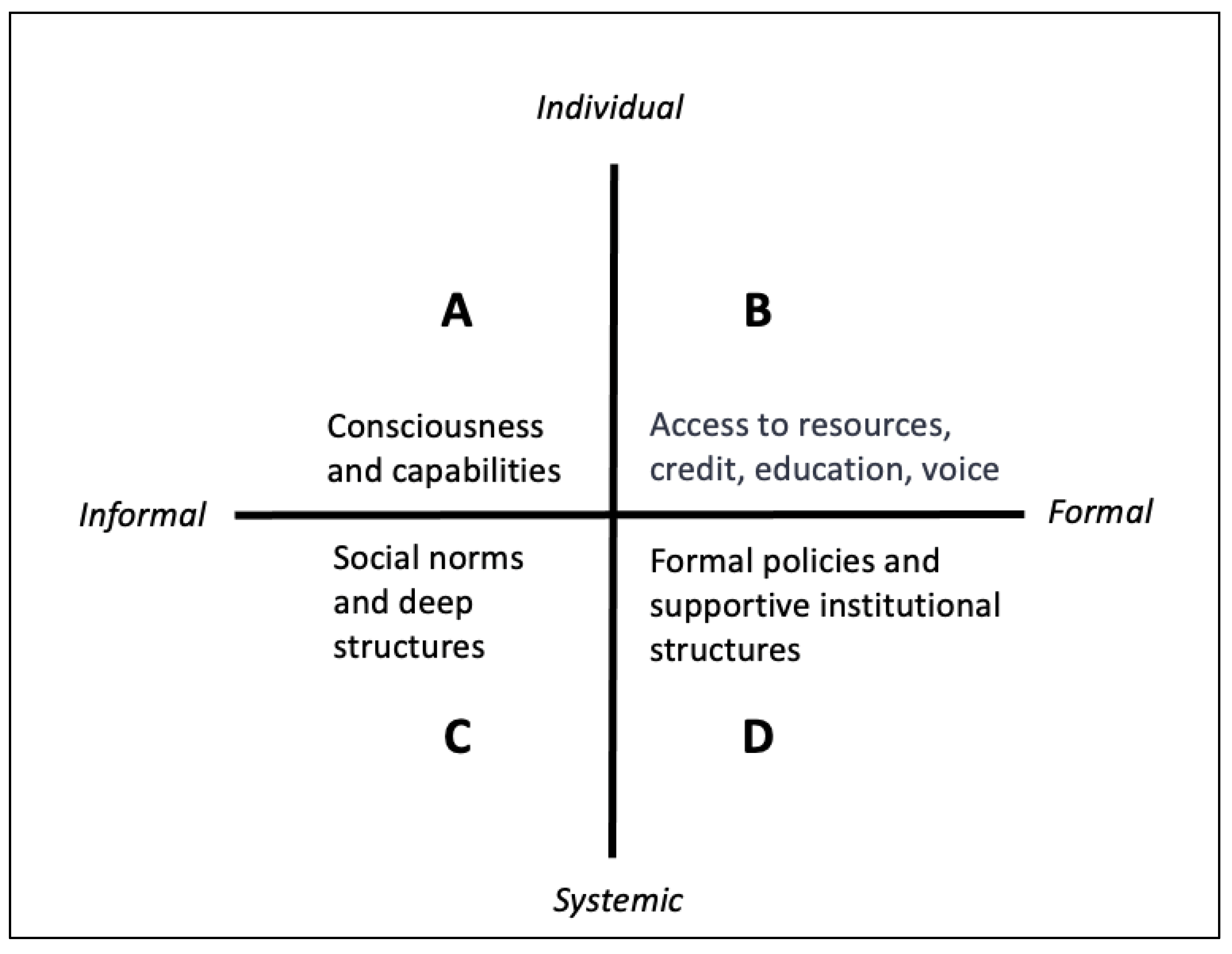

The framework shown below (

Figure 1) highlights different areas of change. It emphasises the need for change at all levels, personal, social and institutional, for gender equality and women’s empowerment to be achieved. Providing women with resources, economic opportunities and supportive policies are insufficient conditions for transformation. A process of change in consciousness that overturns limiting social norms and women’s self-image is also required [

36,

46].

The right side of the framework refers to measurable and tangible efforts, while the left refers to changes that are hidden, invisible or have fewer observable causes and effects. The framework can be used to link ideas from agroecology and gender, and analyse which combination of factors contribute to success and where further change is needed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

This paper is based on qualitative data gathered over three visits to Himachal Pradesh, India, between November 2021 and December 2022 (

Table 3). The study employed a gender-specific approach to gather women's perspectives on the impact of NF on their lives, including intra-household and social relations. Individual male farmers and farming couples were also interviewed to determine how decision-making and work burdens were shared. Furthermore, program officials (7), extension services staff (22), NGO staff (5) and agricultural scientists (4) were interviewed to understand the context, objectives and mechanisms being employed to engage with farmers and scale out NF practices. Each visit involved repeat interviews with program officials and meeting different field staff through snowball sampling. The field staff organised meetings with women farmers and observations of training events.

Data was collected in an iterative process that began with focus groups, where it became clear that the women belonged to four types of farming households in relation to work burdens. These were 1) women-headed households (where a woman is single or widowed), 2) women cultivators with male-out migration (men work in other towns or states and visit home periodically, e.g., every three to six months), 3) women cultivators where husbands mostly live at home but hold non-farm jobs, and 4) both women and men cultivate the land together. The sampling strategy, therefore, took the four types of households into account in addition to caste, length of time that NF was practised, i.e., for more than two years, different agro-climatic zones and types of crops grown. Districts and villages were purposively selected to cover three out of four agro-climatic zones where farms predominantly grew either cereals or vegetables and fruits as cash crops. Thirty-five villages were visited across five districts - Shimla, Solan, Mandi, Kangra and Kullu. These included five homestays with farmers, including two in Scheduled Caste villages.

The initial phase of focus group discussions was followed by individual life story interviews (20), time-use mapping (26) and semi-structured interviews with women farmers individually or in small groups of up to five women. The semi-structured interviews comprised two sets of questions. One set aimed to discover the NF practices adopted, the transition process, the challenges encountered, the support they had received from extension services, the crops grown, and the results achieved. Another set of questions investigated women's perception of how NF had affected them personally and whether it had impacted income earned, intrahousehold decision-making and their roles in the household or the community. Homestays were particularly useful for building rapport and in-depth interviewing, meeting couples, family members, and village council members, and helped to develop a deeper understanding of women's circumstances and the village context. Care was taken to involve farmers traditionally having less power and privilege respectfully. Since introductions through extension staff could inhibit responses, it was clarified that the researcher was investigating what improvements were needed in the state scheme. The first author conducted the interviews in Hindi, a language spoken throughout Himachal Pradesh.

The transcriptions were coded using Nvivo to organise, analyse and highlight the results' trends and nuances. A quantitative approach has not been used to summarise the results related to women's experiences as these would fail to capture the nuances of local contexts and intra-household dynamics [

48]. Instead, woman's accounts have been used to describe their perceptions and the varied realities of their lives.

2.2. Case study location

Himachal Pradesh is one of the northern states across the Himalayan mountains. Agriculture is the source of livelihood for 71% of the population, and 78% of the total cultivated area in the state is rainfed [

49]. It is a major producer of fruits and vegetables and is called 'the apple state' of India. However, intensive agriculture has increased susceptibility to insects, pests, diseases, falling yields and soil degradation in recent years [

2]. About 90% of all farms are small, with less than 2 ha or marginal, with less than 1 ha of land. The average size holding is 0.4 ha [

50]. Land ownership amongst farmers is widespread

1; all farming households interviewed owned land. A few farmers had increased their holdings by leasing additional land. Traditional practices based on manure persist on many marginal farms where chemicals are limited to pesticides. Farmers who specialise in apples and high-value vegetables use a range of agrochemicals. It was observed, that a diverse variety of crops are grown on each farm, including some cereals

2, beans/pulses, oilseeds and between fifteen and twenty-five vegetables and fruits.

Himachal Pradesh has the highest percentage of Hindu population in India, with 95.17% being Hindu compared to a national average of 79.8% [

50]. The Scheduled Castes (SC) constitute 25.22%, Other Backward Classes (OBC) form 13.52%, and Schedule Tribes (ST) form 5.71% of the population

3. STs are concentrated in three northern high-altitude districts, which were not included in this research.

The state is proud of its development indicators and its relative progress compared to other states in India. With a per capita income higher than the national average, the state is one of the wealthiest in the country. Income sources have emerged from agriculture, tourism, and hydropower. Moreover, the state boasts a high literacy rate, which places it among the top four states in India [

52]. Dreze [

53] described the literacy rate relative to the other Indian states as spectacular. The state government has been committed to promoting girls’ education with special incentives. With many villages having an active

mahila mandal (women’s group) in addition to the standard

gram panchayat (village council), public action at the village level has been less male-dominated [

51]. There is a high level of female labour force participation, and women’s involvement in economic activities outside the household is much higher than elsewhere in north India. Additionally, the 7% gender wage gap in 2017-18 compared to other states in India was the lowest [

1]. However, much of the arable land is being used for developmental projects and industries. It leads to the erosion of local subcultures and women’s livelihoods based on traditional agriculture [

54].

Despite educational advances, patriarchal and patrilineal norms continue to take precedence over legal norms in land ownership. Although the Hindu Succession Amendment Act 2005 gives all Hindu women (married and unmarried) equal rights with men for the ownership and inheritance of property, substantial inequalities persist [

55]. Women in Himachal Pradesh forgo their claim to ancestral property to maintain good relations with their brothers. Similarly, in their married homes, the land is passed down to their husbands, and should the husband die young, the father-in-law will not bequeath the son’s portion to the daughter-in-law. Instead, the land will be inherited by other male members of the family. These ingrained beliefs and the norms for gender roles together form a profound cultural basis for gender inequality. No operational holdings in Himachal Pradesh are jointly owned. Women own 7.3% of operational holdings in comparison to a national average of 14% [

50].

To overcome the difficulties of CF, an organic farming policy was established in Himachal Pradesh in 2002. However, organic farming was costly for farmers and lower yields led to financial losses. In its place, in 2018, a State Project Implementing Unit was set up to launch NF as a programme called

Prakritik Kheti Kisan Khushal Yojana (PK3Y) based on practices popularised by a farmer promoter, Subash Palekar (previously known as ZBNF). The main objectives were to reduce the cost of cultivation, increase farmer incomes, particularly for small and marginal farmers, grow healthy food, build climate resilience, and improve soil fertility and water holding capacity. Its vision was presented in line with the FAO concept of sustainable food systems, which recommends holistic growth inclusive of gender, indigenous people, traditional cultures, health, and nutrition [

56]. The state has 961000 farmers, of which 150000 farmers, i.e., 16%, were reported to be transitioning to NF by the end of 2022. However, NF was practised only on 2.5% [

57] of the net sown area, indicating farmers with very small plots of land featuring among NF farmers. Data on how many farmers were using NF on most of their holdings was in the process of being collected.

Subhash Palekar Natural Farming is based on four essential practices aimed at regenerating the soil microbiome for which an indigenous cow is recommended:

Beejamrit, a seed coating of cow dung, cow urine, lime and soil to protect seeds from fungal or soil-borne diseases.

Jeevamrit, a fermented mixture of cow dung and urine, pulse flour, jaggery, uncontaminated soil and water, acts as a microbial culture to promote microbial activity in the soil and enhance fertility. The microbes make soil nutrients bio-available to plants. The microbial culture is also used in its solid form called ghanjeevamrit.

Aachhadan, mulching to conserve soil moisture and stabilise soil temperatures.

Whapasa, the maintenance of aeration and moisture in the soil through humus and limited irrigation.

Other practices include multi-cropping, intercropping and line sowing. Various concoctions with botanical extracts, sour buttermilk and cow urine control pests and fungal diseases. The state offered subsidies for drums (up to three drums per family), cement lining for cowsheds, 50% for the cost of an indigenous cow

limited to Rs 25000

4 with Rs 5000 for transportation, and Rs 10000 for a bio-resource centre (BRC).

3. Results

This section begins with reporting the results related to the NF practices. Next, the processes or mechanisms used to support women’s access to resources and learning opportunities will be described and how these opened pathways for women to build capabilities, skills, knowledge, and opportunities for collaborative work.

Focus group sessions in nine villages revealed that the most immediate challenges to farming were lack of rain and animal or stray cattle raids. Three rainfed villages had no rainwater harvesting structures or watershed development. In villages where animal raids were causing extensive crop damage, the women did not know any NF recipes to deter animals. Nor were they aware of subsidised solar fencing schemes or the options available. Concerning NF benefits, women appreciated the cost savings and benefits to their health the most. Some women had adopted NF in opposition to their families and had proven to them that NF could reap good results. They wished for indigenous seeds and to be able to sell their NF produce at a higher price.

All the farmers who had practised NF for over a year reported that the soil texture had improved, and the population of earthworms had increased. The soil was crumblier or softer and, therefore, easier to till and weed. This concurs with findings in Andhra Pradesh [

58]. 60% of the farmers reported that the results in the first year had been poor for productivity and size of vegetables, e.g., cauliflower heads were smaller. From the 2nd year of transition, 80% of the farmers began to notice that the crops had improved in taste and appearance while the yield was at the same or higher levels than previously. The crops were more climate resilient; wheat and maize had stronger stalks and did not lodge in strong winds or heavy rains. All farmers in the 2nd year of NF reported that the shelf life of vegetables and fruit had improved, and the fruiting period had been prolonged, which resulted in increased income and diet diversity. Higher yield motivated farmers to plant more fruit trees and crops. Many farmers related stories about how their health had improved with NF. Women reported how the pesticides and fertilisers had previously caused them to feel ill with skin rashes, headaches, body aches, and burning skin and eyes. Three farmers, whose health had been adversely affected by conventional farming (CF) to the point that they could no longer work, said they regained their health with NF.

3.1. Prakritik Kheti Kisan Khushal Yojana mechanisms

PK3Y used the existing extension system, the Agricultural Technology Management Agency (ATMA), which had previously offered training in organic and CF. ATMA field officers, 37% of whom were female, are known as Block Technology Managers (BTM) and Assistant Technology Managers (ATM), respectively. A BTM is required to have a master’s degree, while an ATM must at least be a graduate in agricultural sciences. In 2018 and 2019, the extension staff attended six-day training from Subhash Palekar and were reorganised at higher salaries to deliver the NF extension services. These training camps were also attended by progressive farmers. Each of the 80 blocks in 12 districts was assigned one BTM and two ATMs. Consequently, each BTM or ATM was responsible for extension to approximately one hundred villages. This number presented greater challenges in high-altitude districts relative to low-altitude districts. They had the added responsibility of informing and assisting farmers in accessing other government initiatives and schemes. The emphasis was on communicating the new techniques in a friendly and practical manner through demonstrations and working with the farmers in the fields. The training was also cascaded to the farmers through farmers nominated as Master Trainers (MT) and

Krishi Sakhis5. Although trained by Palekar, the extension staff confessed that they were unsure whether the practices would work initially. In some instances, it took them time to adapt the recipes to local conditions to maintain yield. In effect, they were learning together with farmers.

3.1.1. Face-to-face farmer training

The BTMs and ATMs delivered training in the villages themselves rather than setting up a camp in a block or agricultural institutions, which the villagers would have to travel to. This increased access to training, and women could participate with ease. In many villages, it was the first instance of agricultural training that they had ever attended. Women from a scheduled caste (SC) village said:

“People like us did not get trained or find out about training or attend any.”

The trainings were arranged either through existing women’s self-help groups (SHGs) if these had been previously established by ATMA, or through a known farmer or through a panchayat (village council). Training dates were selected by consulting the farmers. Farmers were first encouraged to try NF on a part of their farms, particularly in kitchen gardens. In districts where male outmigration was prevalent, or men held local jobs, primarily women attended the training. Statewide, about 60% of the trained farmers were women. A village training lasted two days with lunch provided and comprised a mix of theory and practical demonstrations. It was delivered jointly by extension staff, a progressive farmer or a farmer who had attended the Palekar training camps and was nominated as an MT. The involvement of a local farmer in trainings was believed to lend greater credibility to practices being promoted. The MTs were familiar with local crops and growing conditions and could communicate in local dialects. It was observed that women listened to a woman MT with greater attention when she spoke in the local dialect.

At the outset, the person trained became both the advocate for and the expert in NF in the family. The trained farmer, whether a man or a woman, was the one who made the NF formulations and developed an understanding of what adaptations were required, what worked, and what did not. Adapting the formulations to local conditions requires creative thinking, intuition and experimentation. Rather than merely indicating who bore the burden of extra work, it engaged women in new areas of endeavour and established who controlled decision-making and problem-solving. This challenged cultural gender roles, which a male farmer explained:

“According to the local culture, it is men who attend trainings and meetings, and the men also take the decisions.”

As NF methods offer a range of safe ingredients and equipment mostly available on the farm, they facilitate experimentation. In many villages visited, there was evidence that women were testing and adjusting the NF preparations to find the best combination to overcome challenges such as pest attacks. In one village, a woman farmer first experimented with different quantities of jeevamrit to investigate its effect on the growth of young apple trees. She subsequently altered the recipes to suit her context. One farmer compared the effectiveness of different pest control substances, including chemical pesticides, cow urine, and NF concoctions, and invented combinations such as tobacco leaves mixed with cow urine. In another village, a group of women altered the frequency of application and recipe of a mixture of sour buttermilk and jeevamrit to deter animal raids. They tested it further in areas where wild pig raids were occurring to check its efficacy and were encouraged by the BTM to share their innovations in training sessions. Through their agency and critical thinking, the women invented a practice to save their crops and increase their productivity by a third.

3.1.2. Establishing NF groups and networks

Along with the training, the extension officers formed an NF group of up to 25 members; therefore, a village of about 50 households would have two NF groups. Previously existing SHGs were used in some villages. They became the channel for communication from the extension staff and the means for handholding - some extension staff made the solutions together with the women during their monthly meetings.

There were several benefits to forming NF groups. They comprised members from similar socio-economic backgrounds and became a mutually supportive learning community through their regular meetings and the use of social media, usually WhatsApp. In some villages with no previous SHGs, the NF groups were the first to offer collaborative spaces for speaking and discussing common concerns. These developed capacities to talk, think through issues and find solutions to challenges. As a result, they became hubs for social, learning and economic activities. In villages where farms were distanced from others, the NF group meetings offered opportunities to meet regularly. In one such village, the women turned the monthly meetings into celebratory events with music, singing, and eating together. As a government initiative, NF offered women greater freedom to spend time away from home for training or meetings.

Moreover, the SHGs acted as saving groups, where each woman contributed a small amount a month towards a savings account that members could borrow from at a low-interest rate. The funds became a handy source of credit for women. They also used their savings to build community resources, such as purchasing mattresses and folding chairs for events and family gatherings. Working collaboratively generated income opportunities, such as selling homemade food products at community fairs and NF events. During the COVID lockdown, members of a group cooked sweets for Diwali to share and sell in a farmer's market.

Establishing NF groups strengthened the traditional culture of reciprocity and labour sharing in Himachal Pradesh called the

jowari system.

Jowari is an informal institution where village members contribute their labour and time in a free exchange system and for managing common village property resources [

59]. Western sociologists refer to this as a dimension of social capital. Putnam [

60] (p.19) defines ‘

social capital’ as "connections among individuals – social networks and the norms of trustworthiness and reciprocity that arise from them". Women in several villages reported working in groups to help each other with farming tasks during busy periods. When NF practices were introduced, women worked collectively to sow in rows, which is more labour-intensive than broadcast sowing. Women groups made the NF preparations in the initial stages of implementing NF in all the villages visited, and some groups continued to share the tasks. The labour-sharing culture helped mitigate the burdens in marginal farms where the men held non-farm jobs.

Collective work and reciprocity engendered through the NF groups reinforced social cohesion and social capital. Not all exchanges in villages were monetised, thus representing use value rather than exchange value. These involved sharing labour, seeds, crops, and resources for NF formulations. Giraldo and Rosset [

61] describe exchanges of use value as fundamental to transformative agroecologies as these consolidate solidarity and cooperative economies. The farmers could access most materials within the village itself free of cost. Farmers who owned indigenous cows made the cow dung and urine available to others. However, transporting the materials to their farms was often laborious and viewed as an extra burden that some women preferred to avoid undertaking. Therefore, not owning a local breed of cow became an obstacle to adopting NF. The advice to farmers was altered later to increase the proportion of cow urine from non-indigenous cows in recipes so that farmers could use their own crossbred Jersey and Holstein cows

6.

The social networks became a pathway for informal and horizontal farmer knowledge exchange. Using a messaging app on smartphones became a vital tool for dialogues of knowledge and learning (61]. Farmers posted pictures, appreciated each other’s work and raised questions on how to manage diseases. Moreover, two-way interchanges between farmers and extension staff took place: the extension officers informed members about techniques, success stories, which farmers had indigenous seeds to share, and forthcoming meetings while the farmers contacted them with any queries regarding practices. A messaging app, therefore, became an essential tool for handholding. A Block Technology Manager posted videos of farmers, often women, explaining various practices. These demonstrated to women that they were valued and promoted enthusiasm and motivation. In addition to the village NF groups, there were block and district-level WhatsApp groups, which included extension staff and both male and women farmers. MTs became members of a state MT group. The wider groups enabled communications about farmer innovations and became an indigenous seed exchange mechanism. However, communications about farmer-led innovations did not seem to be communicated between districts; for example, extension staff in various districts were unaware of how the NF solutions were being used to deter animal raids by farmers in Solan district.

3.1.3. Visits to farms and conferences

Another critical mechanism for the horizontal transmission of knowledge used by PK3Y was for farmers to visit progressive or model farms. Extension staff arranged exposure visits to model farms established in each

panchayat or out of state. Additionally, there were state-level women’s farmers meetings held on occasion. PK3Y arranged for 721 women farmers to attend a two-day conference in 2022 to mark International Women’s Day. It is widely acknowledged that horizontal exchanges were vital to the success of the agroecology movement in Cuba, the most successful worldwide, which grew to over 100,000 smallholders in eight years. A study of the campesino-a-campesino (farmer-to-farmer) methodology revealed that training workshops were followed by farmer gatherings and conferences where smallholders presented their experiences and listened to new ideas from technicians and scientists. Farmer exchange visits were encouraged, where one group of farmers visited another to see sustainable practices at work – tools, seeds, information, and knowledge passed hand to hand as an example of shared cultural praxis [

62,

63]. Observing other farmers generated enthusiasm to try the practices. Some women mentioned that they were growing a wider range of crops, having seen the variety grown by other farmers, which positively impacted their dietary diversity. For some women, the visits were a significant event in their lives and the first opportunity they had to travel out of their district or state, as illustrated in Vignette 1:

Vignette 1:

3.1.4. Leadership roles

Women who held leadership roles as MTs benefited greatly. An MT was assigned to deliver training with extension staff or on their own to villages in three panchayats. Some MTs reported that they were given a target to introduce 30 farmers to NF in a month. 17 MTs who were interviewed agreed that the leadership roles had been beneficial in building their confidence, widening their social network and earning respect from the community. They appreciated the support they received from extension staff to develop confidence in addressing groups. The role gave them freedom of movement, overcoming cultural restrictions on their mobility in public spaces. In the more populous districts, women felt safe travelling to villages independently. Three MTs commented on how it improved their learning as they aspired to become more knowledgeable. A 40-year-old farmer commented on how social interchanges affected her well-being:

“When you leave the home, meet people and socialise, it freshens your mind and brings about change. When the mind is at peace, the person is happy. Peace of mind also affects your body. If a woman is not healthy, how can she raise healthy children or a healthy family.”

Once they became known in the community, it created a domino effect for their involvement in community projects. One MT was selected as the secretary of an SHG federation comprising 150 members; another was selected as the chairperson of a Farmer Producer Company facilitated by PK3Y. In a SC village, the MT and women from the NF group volunteered to run a state programme to teach basic literacy skills. They gave daily lessons for three months to women who had missed out on an education. For a few women, it became a catalyst to realise long-held personal goals, e.g., an MT chose to complete higher secondary school. Another farmer added an outside room to set up a shop in her house, which had been a long-held aspiration. The transformations in personal power triggered a shift in power relations within the home and the community. LK spoke about how her increasing confidence had resulted in altering intra-household relations:

“I used to feel that I had only studied till the 10th and didn’t know anything. I used to be afraid. Now, I have learned how to speak to people with confidence, and my knowledge has increased. My husband has noticed the change in me and looks to me to make decisions. It is because of NF that I am recognised; I have progressed and moved up in life.”

3.2. Increased economic opportunities and control over income

Most women interviewed had an independent source of income other than crops or the husband’s earnings being shared with the wife for household expenses. Usually, this was derived from selling milk and food products or sewing and handicrafts. On some farms, where the husband sold farm produce in the Mandi (wholesale market), the cash payments would be shared with the wife while the cheque would be deposited in the husband’s account. However, there were variations amongst households. Women whose husbands held full-time jobs either locally or elsewhere were the most independent in decision-making and control over income earned from the farm. This was especially true for marginal farms where farm income was supplementary. There was a fair amount of intra-household dialogue involved in household decision-making. All the women reported that they discussed major decisions with their husbands – this did not detract from their control; rather, the decision-making was part of an ongoing cooperative household dynamic. Increased incomes through NF resulted in the women contributing more to household expenses, which altered their status within the home. Women proudly stated how their earnings contributed to running everyday household expenses, paying for their children’s education or contributing to the extension of their home.

Many women felt it was essential to have their own earnings to spend money without having to justify the expenditure to themselves or their husbands. This was especially relevant for a few women who had toiled hard over the years to meet personal expenses rather than ask their husbands for their share of income from the farm. Where gender relations were mutually supportive, some women did not think they needed an income that was theirs alone.

About 25% of farmers interviewed were able to increase their income by selling NF produce directly to the public. This was often the case in Kangra, a populous district with many non-farming families. Some farmers developed a network of buyers who would place orders in advance and collect from the farmer. These sales secured between 10% to 20% more than the market rate on account of crop quality and their NF status. Marginal farmers with small holdings benefitted from selling their crops through the outlets arranged by PK3Y. This comprised of NF canopies, managed by farmers, set up at central locations on particular days of the week. Some farmers used their own or group canopies to sell at community events or in their villages, as illustrated in Vignette 2:

Vignette 2:

Some farmers who had previously practised organic farming reported that NF had significantly impacted their incomes. In organic farming, they had to purchase expensive biological inputs while the yield had not increased. For farmers transitioning from CF, savings on costs of chemical inputs depended on the types of crops grown. Savings were substantial for farmers who grew disease-prone cash crops such as capsicums and tomatoes, where they spent approximately Rs 100,000 per acre (0.4 ha) a year on chemical inputs. These costs were reduced by 90% and contributed to an increase of 30% in annual profits. Additionally, for all farmers, several factors, such as farming the plots more intensively with a wider variety of crops, a higher yield, a more extended fruiting period, longer shelf-life and better appearance, resulted in higher incomes. Encouraged by PK3Y staff, farmers began to grow more indigenous cereals, such as red rice and millets, for their own consumption and higher selling prices. Many of these factors also contributed to their diet diversity. Most farmers were hopeful that being certified as NF farmers under the new Certified Evaluation Tool for Agriculture Resource Analysis (CETARA) system established by PK3Y would secure higher prices for their produce [

64].

Setting up a bio-resource centre (BRC) presented another economic opportunity for women farmers. Farmers reported earning between Rs 1000 and Rs 5000 monthly, depending on the demand for NF formulations in a village. However, a woman farmer found that replacing her two Jersey cows with two sahiwal (an indigenous breed) cows to set up a BRC led to a loss in income. The sahiwal cows, purchased from a neighbouring state, did not adapt well to the colder climate in Himachal Pradesh, resulting in a loss from milk sales. On the other hand, selling cow urine and NF formulations did not compensate for the losses.

3.3. Effect on workloads

A time-use survey with 26 women farmers revealed that the average workday comprising both care and productive work, excluding times for personal care and leisure, was 14 hours long. It started early, often at 5.00 a.m., for women to first attend to their cows (or other livestock). All women farmers except two interviewed owned cattle, commonly one or two cows. Livestock care was time-consuming. Collecting fodder took two hours a day on average and could be excessively burdensome and risky. It involved women carrying 30 to 50 kg loads on their backs or heads over long distances or steep terrain in high-altitude districts. Many women also climbed trees to cut branches. On days when the women worked as waged labourers for a Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA)

7 project, they started the day at 4 a.m. to allow for fodder collection. In Mandi and Kullu, the women spent several weeks in Autumn gathering stocks of dry grass and firewood two or three times daily to store for the snow-bound winter months. A round trip from the forest could take several hours. During this period, men also helped carry loads. Farming in the fields took, on average, three hours a day with seasonal variations for a plot of 1 acre (0.4 ha).

Another arduous task related to livestock that women performed was carrying cow dung to the fields daily to add to a farm yard manure (FYM) heap. NF practices offered an alternative which eased this burden. If FYM was applied directly, 80 kilos of cow dung was required for 40 fruit trees. NF offered the alternative of replacing FYM with one drum of jeevamrit that needed only 10 kg of cow dung. However, most farmers interviewed strongly felt that using FYM was a traditional practice they would not relinquish. In contrast, a woman from a mountainous district felt that NF had relieved her of the burden of carrying cow dung uphill daily to the field. Instead, she needed to carry 50 kg ghanjeevamrit for her 1 acre (0.4 ha) plot four times a year.

Women who made their own formulations reported that the tasks added two hours a week to their workload. They found that this was a fair trade-off for saving costs. When both the husband and wife had received training, the tasks were shared. Farmers said that the spraying schedule was equivalent to that of conventional farming. This varied, however, according to the crops grown and seeds used. Farmers growing tomatoes from hybrid seeds needed to spray pest-control or anti-fungal concoctions twice a week, which added to workloads considerably. The burdens were mitigated by sharing the spraying tasks with the family, including older teenage children who had previously not been allowed to spray chemical pesticides. Farmers with larger plots reported that line sowing, applying mulches and weeding by hand added to workloads or labour costs.

3.4. Perceived constraints on the adoption of natural farming

The NF interventions were taking place in the context of constraints. Sen [

43] refers to these as ‘conversion factors’ which can block or differentiate people’s ability to acquire capabilities and achieve goals. These contextual conversion factors may include family characteristics or physical and socio-economic constraints. They could impede the take-up of NF or its scaling out; for example, horizontal exchanges were constrained by the unavailability of smartphones for some women - those women who started with better assets and capabilities captured more significant benefits than those who did not.

Some women rejected NF as it appeared complicated and felt it would increase their workloads to an intolerable level: for example, mothers with young children, women farming on fragmented and distant fields, or those without help at home or with many animals. The lack of support in the home or from the community when the plots were larger or where the fields were at a distance could not mitigate the work burdens. Periods of drought constrained farmers on rain-fed farms. Women felt it was pointless taking up NF as the drought would hamper their efforts.

Inadequate planning and execution by a state department can hinder the adoption of NF. Even the most well-intentioned project can be negatively impacted by staff members who hold opposing views or lack personal engagement. For instance, farmers in different districts were taken on exposure visits to other farms with varying frequency. Additionally, a few extension officers failed to inform women about government schemes that could help mitigate challenges or offer appropriate support in acquiring subsidies. Although indigenous seeds were promoted, some officers with an industrial agriculture mindset distributed hybrid seeds to farmers. This raises the question of how managers and front-line workers can be empowered to act as agents of change.

Lack of land ownership is a further perceived constraint by women. A woman farmer reported failing to secure a bank loan to start a ghee-making enterprise because she did not own land. The lack of access to credit limits women’s freedom of action and choice, the means to improve their economic status and circumvents their creative and productive potential. In a domestic situation, financial abuse is recognised as preventing a cohabitant from acquiring resources or assets, advancing their careers or restricting their ability to find employment. An individual uses this abuse to exert power and control over another. It may be argued that societal norms of denying land to women are an expression of economic abuse perpetrated collectively on women. In Himachal Pradesh, it is disguised as a cultural tradition that encourages good sibling relations.

Every woman interviewed who had siblings said that they had agreed to gift their portion of land to their brother/s or, in one instance, to a sister who was caring for the parents. They had made the decision either when their father had asked if they wished to inherit a portion of the land or after the death of their father at a meeting held by the land inheritance official. The officials often pressured the daughters to relinquish their share in favour of their brother/s [

55]. A male farmer remarked that a woman’s failure to gift the land to her brothers is considered lowly and dishonourable.

A woman who had one sister and two brothers said:

“My father willed the land to the sons so that we would not need to attend a meeting with the tehsildar to give up our portions. This is an old tradition. In case there is a problem where the sister’s marriage fails, the brother will give land to the sister for her to build a home. We trust the brother.”

However, SK, an MT and a divorced single woman living with her parents and brother for twelve years since her divorce, had yet to receive land or the promise of land from her parents. SK actively supported single women to take up NF:

“For a single woman, it has had many benefits. There are some who were widowed early. Rather than thinking about issues at home and feeling depressed, they get out of the home, meet people and get busy with a project.”

Despite her leadership capabilities, she did not question the validity of the patrilineal norms and felt that asking for her portion of the land would reflect poorly on her.

4. Discussion

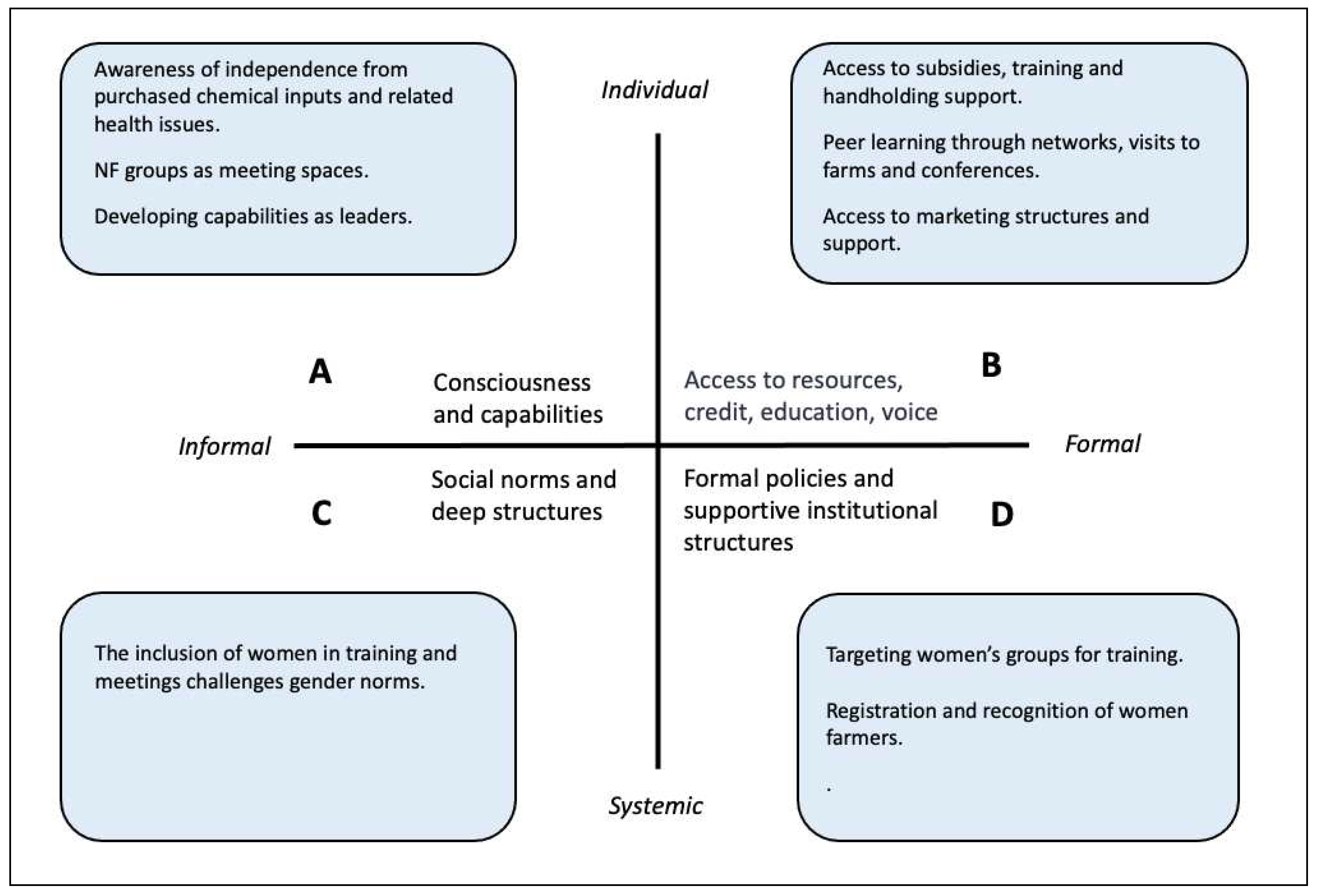

When implemented with adequate mechanisms for training and supporting women farmers, the NF initiative was seen to reap various benefits. The mechanisms described in ‘Results’ have been listed in

Figure 2 below. How the individual and systemic changes impacted women will be discussed next.

4.1. Quadrants A and B

The NF programme promised independence from corporate control, placing control back in the hands of farmers. As an agroecological approach, it reconceptualised what a woman could be or do as a farmer. In contrast to the industrial agriculture paradigm, which dispossessed farmers of their knowledge, telling them what to grow and how to grow it and the seeds they need to purchase, a transition to agroecology is knowledge-intensive. It requires considerable individual ingenuity to maximise the ecological advantages of their local environment [

21]. The evidence demonstrates that agroecological farming motivated the women; farming became meaningful, requiring traditional knowledge of local ecosystems, new learnings, creativity and innovation [

65]. Women appreciated the independence, dignity and control NF gave them, that it engaged their minds and expanded their knowledge:

“I learnt that we have the ability and resources to make whatever we need. We do not have to depend on the market. Knowing that I can rely on myself makes me feel confident.”

“We find natural farming interesting, and it keeps our minds active. We want to learn more about how to control diseases. “

Further, the NF vision of caring for ‘mother’ earth, one’s health and protecting the land for future generations resonated with women’s spiritual values. Women viewed NF as a worthy cause and felt good about participating. The fact that people may act for the good of others is a vital part of Sen’s capability approach [

43]. It is broader than many concepts of agency because the agent is not self-centred. A new clarity of vision inspired and motivated both women and men farmers to persist with their efforts towards creating an ecologically friendly way of farming for the greater good:

“I feel good that the earth is safe, and we are not feeding poisons to people. I am establishing an example for future generations to follow.”

Some women undertook NF despite opposition from their families. A SC woman wanted to revive millets for the benefit of the village farmers. She reported,

“My husband tried to discourage me, but this made me even more intent on proceeding with the project. I argued that it would be beneficial for the women in the village and also to sell.”

Transition mechanisms further paved the way for empowerment. Establishing NF groups brought women together to share experiences, reflect and build solidarity towards a common cause. It enabled women to discover common ground by realising that their problems were similar to those experienced by other women. A new perception of reality was constructed. A 38-year-old SC women farmer explained how joining a group developed confidence and agency:

“When we work the whole day, we do not even realise how hard we have worked. When we join a group, we get a good opportunity to express our thoughts and discuss our issues. When we attend a meeting, we get to learn new things. By joining a group, we acquire confidence and the capability to act.”

The fact that women attended training and had direct access to subsidies strengthened their role. This challenged notions of gender identities and patriarchal barriers. It was evident that in addition to peer-to-peer knowledge exchanges, structured learning options that advanced knowledge beyond basic practices were needed. A farmer who had undergone the two-day training explained:

“I am hesitant to advise other farmers. What if it affects them adversely? I have not been trained properly; I am just following what I have been told by ATMA staff.”

While there may be a need in the early stages of transition to introduce recipe options that produce quick results, the full benefits of a transition, such as increased production, fewer pest attacks, and reduced need for inputs, can only be realised upon greater agroecological integration [

66]. These call for an understanding of how complex ecological processes interact. Notably, the women who reported adjusting recipes had either attended the six-day training by Palekar; that is, they had gained a deeper understanding of agricultural processes, or they had been encouraged to think critically and find local solutions by extension officers. Given that many women do not have access to the internet through smartphones, the state needs to think about how access to learning networks and training could be assured for them. The requirement for farmers running model farms,

Krishi Sakhis, farmer trainers and extension staff to be well-versed in a range of NF practices and the vision of NF as a new food systems approach becomes all the more critical.

When women were trained and demonstrated an interest in NF, it became the starting point of a widening social network where increased interactions with farmers, extension, and government officers developed the ‘power with’. It built capacities to talk to government employees. raise questions, and share knowledge with their peers. RD, a 40-year-old SC farmer, received visitors and visited other farms; she spoke at a panchayat (village council) meeting and a video of her explaining practices was posted on YouTube by the BTM. She was one of five women in her village who travelled to Shimla, the capital, to attend a meeting with the executive director of NF. She explained how the social interactions and recognition built her sense of self-worth and gave her a sense of identity and purpose, thus developing her civic capacities and citizenship power:

“When we started natural farming and got good results, we began to be known by other people. People asked us about the practices and wanted to visit our farms. It made us feel happy and that we were significant and had a place in the world…... We are learning more about government schemes by meeting people and attending panchayat meetings. We now support women by registering requests. We have gained the confidence to state our wants or speak about what is needed in the community.”

The investigations show that the way women were empowered extends beyond the definition of empowerment as "the expansion in people's ability to make strategic life choices in a context where this ability was previously denied to them" [

37] (p.437). A shift to industrial agriculture had alienated women from their traditional farming knowledge and marginalised their roles. As a counter-movement, NF restored their “right to participate in decision-making” [

19], which, coupled with transition mechanisms aligned with the principles of agroecology, created new possibilities for empowerment. Training, new technologies, access to learning and social networks, and experiencing leadership roles were new pathways framed within and driven by the vision of protecting the earth as the source of life and reclaiming their food sovereignty. Thus, NF became instrumental in developing the existing dynamism in these women, building confidence and capabilities, which, in turn, resulted in a gradual change in the power relations in the home and society.

4.2. Quadrants C and D

The CETARA system established by PK3Y formalised the recognition of women as farmers, a step that challenges discriminatory gender norms and bolsters women’s self-image. Further, all data must be analysed by gender to understand women's participation in different categories. Both institutional mechanisms and policies need to be scrutinised for the differential impact they may have on women. For example, NF practices called for using indigenous cows, which could substantially increase women’s workloads. To change attitudes that hold inequalities in place, gender-aware policies need to be integrated at all levels of institutional work. It asks for continued monitoring of activities according to gender and the proportionate inclusion of women farmers in state meetings, exposure visits, consultations, and senior managerial positions.

In challenging norms for women farmers' roles, the state exemplified how it could influence people's capacities to think differently and, thereby, construct a new 'common sense' [

67]. The state's role could be further harnessed to dismantle the invisible power of cultural norms and beliefs that limit women’s land ownership. The state could encourage joint land titles by waiving fees, offering monetary incentives and public appreciation of male farmers who include their wives on land deeds or fathers who bequeath land to their daughters. Women, too, could be encouraged to critically examine the reasons for not claiming their land. After all, the classic argument that daughters do not inherit land because it causes further fragmentation should apply equally to male siblings. In practice, many rural families cultivate land jointly and cultivate land belonging to those siblings who may have migrated for work. A married sister who wishes to support a brother could retain the title as a security measure, while the brother could cultivate the land for his own benefit. This would preserve familial relations, and, in exchange, the brother, in his traditional role as the maternal uncle, could contribute to the costs of his niece or nephew's wedding as is the norm.

5. Conclusion

This research paper investigated how a state-led transition to natural farming, an agroecological approach, empowered women farmers. What this study interestingly showcases is that it can offer spaces into previously unimagined women’s empowerment through agroecology as a mechanism. Many women felt sufficiently empowered to defend NF's aims and methods in the face of family opposition. Others, as trainers, participated as active facilitators of the transition processes in their local area and further afield. A few addressed conferences and participated in discussions with PK3Y directors to give voice to its benefits and shortfalls. Furthermore, the benefits derived from increased empowerment not only rippled out to the advantage of other women, communities, and initiatives but across generations as, in some instances, children of the women became involved with the NF work. At its most effective, the NF mechanisms produced a positive feedback loop initiated by the work and actions of the women farmers that further strengthened their sense of empowerment. In short, for many women, their growing sense of self-confidence and faith in their own developing capabilities contributed to “extending the horizons of possibility, of what people imagine themselves being able to be and do” [

68] (p.3).

A nuanced understanding of women’s lives and choices exposed the power dynamics and how they manifested in the transition process. The tradition of collective work offered women vital support in their efforts to transition to NF, which, in turn, built social capital and expanded community agency. The positive collaborative spaces created by forming NF groups built the ‘power within’ and ‘power with’ and engendered a rich communication dynamic for learning and innovation. These new alliances for a common cause harnessed the ‘power for’ and strengthened their resolve to traverse new territories and take greater risks to realise a vision. This was observed across castes. The increased capabilities developed through leadership roles, illustrative of the ‘power to’, spurred the women to undertake further personal and community projects.

The state’s success in promoting natural farming depends largely on women’s efforts, even though women already shoulder substantial workloads. So that the state is not burdening women to contribute even greater efforts towards saving the soil and our health, women’s efforts must be fully supported. It is necessary to consult women to understand their needs and preferences concerning opportunities to further their knowledge, the provision of technology aids to reduce drudgery, support to revive indigenous seeds and the state challenging norms that deny women ownership of land. Further, farmers require supportive infrastructures to promote sustainability in a changing climate, including protecting ecosystems and watershed development.

This case study illustrates how an agroecology transition with a deliberate focus on gender can significantly enhance life outcomes for women farmers owing to their increased sense of empowerment. Providing opportunities for decision-making and reclaiming their food sovereignty mobilised women to harness their strengths, talents and creativity to bring about transformative change in their lives and communities. Further research is needed to explore how more women farmers can overcome obstacles and participate as decision-makers and innovators in agroecology transformations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B., H.O., S.C.; investigation and writing, P.B.; review, editing, H.O., S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the University of Reading.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethics Approval was granted by the University of Reading, School of Agriculture, Policy, and Development with Reference Number: 001691 on 1st November 2021 prior to fieldwork.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the primary author. The data are not publicly available due to the privacy concerns of the participants.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the directors and officers of the State Project Implementing Unit of Prakritik Kheti Kisan Khushal Yojana in Himachal Pradesh for their interviews and efforts in arranging contacts with extension staff and farmers. Our sincere thanks also to Nirmal Chandel (Ekal Nari Shakti Sanaghathan), Sukhdev Vishwapremi (RTDC), and Dr, D. K. Sadana (HimRRA) for sharing information on their initiatives and providing farmer contacts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 |

Land distribution reforms in 1960s and 1970s reduced the hegemony of large farmers, resulting in more widespread land ownership [ 51]. |

| 2 |

Maize, wheat, paddy and barley were most grown in that order. Lesser grown cereals were buckwheat and millets.. |

| 3 |

Discrimination based on caste is still prevalent in modern India. The Indian government officially recognises historically discriminated communities of India referred to as ‘Dalits’ under the designation of ‘Scheduled Castes’ or ‘Scheduled Tribes’ and certain economically backward castes as ‘Other Backward Classes’. This enables affirmative action to reduce inequalities. |

| 4 |

Rs 10000 was equivalent to $120.48 at the exchange rate of Rs 83 to 1 dollar. |

| 5 |

Krishi Sakhis are community resource persons funded by a central government scheme to support rural women. |

| 6 |

Himachal Pradesh began breeding programmes for local cattle cross-bred with foreign breeds, such as Jersey and Holstein, in 1954 to increase milk production (GoHP, nd). |

| 7 |

MGNREGA, established in 2005, is a social welfare measure that aims to guarantee at least 100 days of wage employment per year for at least one member of every rural household. |

References

- NRAS (2020) ‘State of Rural and Agrarian India Report 2020’. Available at: http://www.ruralagrarianstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/State-of-Rural-and-Agrarian-India-Report-2020.pdf.

- GOI (2009) State of Environment Report India 2009. Available at: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/state-environment-report-india.

- Khadse, A. (2017) ‘Women, Agroecology & Gender Equality’, Focus on the Global South, India.

- Agarwal, B. (2020) ‘Does group farming empower rural women? The Journal of Peasant Studies, 4: Journal of Peasant Studies, 47; :4. [CrossRef]

- Action Aid Brazil (2011) ’ Agroecology: Exploring Opportunities For Women’s Empowerment Based On Experiences From Brazil’, Feminist Perspectives Towards Transforming Economic Power. AWID. Available at https://www.landportal.org/fr/node/13813.

- Benítez, B. , Nelson, E., Romero Sarduy, M I., Ortíz Pérez, R., Crespo Morales, A., Casanova Rodríguez, C., Campos Gómez, M., Méndez Bordón, A., Martínez Massip, A., Hernández Beltrán, Y. and Daniels, J (2020) ‘Empowering Women and Building Sustainable Food Systems: A Case Study of Cuba's Local Agricultural Innovation Project’, Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4(219).

- Oliver, B. (2016) ‘The Earth Gives Us So Much: Agroecology and Rural Women's Leadership in Uruguay’, Culture, agriculture, food and the environment, 38(1): 38-47.

- Deb, D. (2009) Beyond Developmentality. London: Earthscan.

- Patel, R. 1: ‘The Long Green Revolution’, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 40, 2013; :1. [CrossRef]

- Pimbert, M. (2009) Towards Food Sovereignty: Reclaiming Autonomous Food Systems, London: IIED.

- NCNF (nd) Guiding Principles of Natural Farming. Available at: https://nfcoalition.in. (Accessed: 30 August 2023).

- NITI Aayog (2017) India Three Year Action Agenda. Available at: https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2023-03/Three-Year-Action-Agenda-2017-19.pdf. (Accessed: 30 August 2023).

- Altieri, M. and Nicholls, C. (2017) ‘Agroecology: a brief account of its origins and currents of thought in Latin America’, Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 41(3-4), pp.231-237.

- Sanderson Bellamy, A. and Ioris, A. (2017) ‘Addressing the Knowledge Gaps in Agroecology and Identifying Guiding Principles for Transforming Conventional Agri-Food Systems’, Sustainability, 9(3), p.330.

- Anderson, C. , Bruil, J., Chappell, M., Kiss, C. and Pimbert, M. (2021) Agroecology Now!. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bello, W. (2009) The Food Wars. London: Verso.

- Martínez-Torres, M. E. , & Rosset, P. M. (2010) ‘La Vía Campesina: the birth and evolution of a transnational social movement’, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 37(1), 149-175.

- Alonso-Fradejas, A. , Borras, S., Holmes,T., Holt-Giménez, E. & Robbins, M.J. (2015) ‘Food sovereignty: convergence and contradictions, conditions and challenges’, Third World Quarterly, 36:3, pp 431-448.

- Nyéléni (2007) Synthesis report - nyeleni.org. Available at: https://nyeleni.org/IMG/pdf/31Mar2007NyeleniSynthesisReport-en.pdf (Accessed: 30 June 2023).

- Wezel, A. , Bellon, S., Doré, T., Francis, C., Vallod, D. and David, C. (2009) ‘Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice: A review’, Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 29(4), pp.503-515.

- Schneider, M. & McMichael, M. (2010) ‘Deepening, and repairing, the metabolic rift’, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 37:3, 461-484. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. , Bruil, J., Chappell, M., Kiss, C. and Pimbert, M. (2019) ‘From Transition to Domains of Transformation: Getting to Sustainable and Just Food Systems through Agroecology’, Sustainability, 11(19), p. 5272.

- Ferguson, B.G. , Maya, M.A., Giraldo, O., Cacho, M., Morales, H., & Rosset, P. (2019) ‘Special issue editorial: What do we mean by agroecological scaling? Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, -8. [CrossRef]

- IDS & IPES-Food (2022) Agroecology, regenerative agriculture, and nature-based solutions: Competing framings of food system sustainability in global policy and funding spaces. Available at: https://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/SmokeAndMirrors_BackgroundStudy.pdf.

- Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho, M. , Giraldo, O. F., Aldasoro, M., Morales, H., Ferguson, B. G., Rosset, P. (2018) ‘Bringing Agroecology to Scale: Key Drivers and Emblematic Cases’, Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 42(6), pp 637-665.

- Hill, S. B. (1985) Redesigning the Food System for Sustainability. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285538508_Redesigning_the_food_system_for_sustainability.

- Gliessman, S.R. and Engles, E. (2015) Agroecology: The Ecology of Sustainable Food Systems. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Bharucha, Z.P., Mitjans, S.B. & Pretty, J. (2020) ‘Towards redesign at scale through zero budget natural farming in Andhra Pradesh, India’, International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 18:1, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- GIST Impact Report (2023) Natural Farming Through a Wide-Angle Lens: True Cost Accounting Study of Community Managed Natural Farming in Andhra Pradesh, India. GIST Impact, Switzerland and India.

- HLPE (2019) ‘Agroecological and other innovative approaches for sustainable agriculture and food systems that enhance food security and nutrition’, A report by the High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome.

- FAO (2018) The 10 elements of agroecology. Available at: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/I9037EN/ (Accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Pattnaik, I. , Lahiri-Dutt, K., Lockie, S., and Pritchard, B. (2018) ‘The Feminization of Agriculture or the Feminization of Agrarian Distress? Tracking the Trajectory of Women in Agriculture in India’, Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 23 (1): 138–55. [CrossRef]

- Bezner Kerr, R. 5: ‘Seed struggles and food sovereignty in northern Malawi’, Journal of Peasant Studies, 40, 2013; :5. [CrossRef]

- Montiel, M.S. , Rivera-Ferre, M. and Roces, I.G. (2020) ‘The path to feminist agroecology’, Farming Matters. Available at: https://www.cidse.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/07_09_FM0120_Perpectives.pdf.

- Khadse, A. (2017) ‘Women, Agroecology & Gender Equality’, Focus on the Global South, India.

- Larrauri, O. , Pérez Neira, D. and Montiel, M. S. (2016) ‘Indicators for the Analysis of Peasant Women’s Equity and Empowerment Situations in a Sustainability Framework: A Case Study of Cacao Production in Ecuador’, Sustainability 8, pp 1231.

- Cornwall, A. (2017) ‘The Role of Social and Political Action in Advancing Women’s Rights, Empowerment, and Accountability to Women’, IDS Working Paper 488, Institute of Development Studies, Brighton.

- Cornwall, A. (2016) ‘Women's Empowerment: What Works?’, Journal of International Development, 28(3), pp.342. [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. (2002) ‘Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women's Empowerment’, Development and Chang, 30(3), pp 435-464.

- Bradley, A. (2019) ‘Did we forget about power?’ In McGee, R. and Pettit, J. (Eds) Power, Empowerment and Social Change, Routledge.

- Rowlands, J. (1995) ‘Empowerment examined’, Development in Practice, 5(2), pp.101-107.

- Belenky, M. F. , Clinchy, B. M., Goldberger, N. R. & Tarule, J. M. (1986) Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice and Mind. New York, Basic Books.

- Sen, A. (1999) Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schwendler, S.F. and Thompson, L.A. (2017) ‘An education in gender and agroecology in Brazil’s Landless Rural Workers’ Movement’, Gender and Education, 29:1, 100-114. [CrossRef]

- UN Women (nd) Women and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/women-and-the-sdgs.

- Batliwala, S. (1994) ‘The meaning of women's empowerment: New concepts from action’, In Sen, G., Germain, A. & Chen, L.C. (ed) Population Policies Reconsidered: Health, Empowerment and Rights, pp 127-138.

- Rao, A. , Sandler, J., Kelleher. D. and Miller, C. (2016) Gender at work: Theory and practice for 21st Century organizations. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Addison, L. , Schnurr, M. A., Gore, C., Bawa, S. and Mujabi-Mujuzi, S. (2021) ‘Women’s Empowerment in Africa: Critical Reflections on the Abbreviated Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (A-WEAI)’, African Studies Review. Cambridge University Press, 64(2), pp. 276–291. [CrossRef]

- NITI Aayog (2021) Knowledge sharing workshop on natural farming. Available at: https://naturalfarming.niti.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Dr-Rajeshwar-Chandel-NITI-Meeting-301121.pdf (Accessed: 30 June 2023).

- GOI (2019) Agriculture Census 2015-16. Available at: http://agcensus.nic.in/document/agcen1516/T1_ac_2015_16.pdf.

- Sudarshan, R.M. (2011) India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Act: women’s participation and impacts in Himachal Pradesh, Kerala and Rajasthan. CSP Research Report 06. Available at: https://www.ids.ac.uk/download.php?file=files/dmfile/ResearchReport06FINAL.pdf.

- Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation (2023). State-Wise Data on per Capita Income. Available at: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1942055.

- Dreze, J. (1999) A surprising exception. Himachal's success in promoting female education. Manushi.

- Minocha, R. (2015) ‘Gender, Environment and Social Transformation: A Study of Selected Villages in Himachal Pradesh’, Indian Journal of Gender Studies. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B., Anthwal, P. & Mahesh, M. (2021) ‘How Many and Which Women Own Land in India? Inter-gender and Intra-gender Gaps’, The Journal of Development Studies. [CrossRef]

- FAO (2018) Sustainable food systems, Concept and framework. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/ca2079en/CA2079EN.pdf.

- CSE (2023) Market Access in India for Organic and Natural Produce (Webinar). Available at: https://www.cseindia.org/market-access-in-india-for-organic-and-natural-produce-11758. (Accessed on 20 June 2023).