Submitted:

31 October 2023

Posted:

01 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Treatment as Usual (TAU)

2.3. Non-Immersive Multisensory Virtual Experience for Emotional Regulation Intervention (VE-ER)

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Descriptive Variables

2.3.2. Feasibility

2.3.3. Acceptability

2.3.4. Exploratory Outcomes of Effectiveness

- −

- Difficulties in Emotion Regulation (DERS) [49]. This self-report scale asks respondents to rate how they manage their emotions on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never to always. Six subscales emerge from the questionnaires: (1) “The inability to accept emotional responses,” (2) “Impulse control difficulties,” (3) “Difficulty engaging in goal-directed behavior,” (4) “A lack of emotional awareness,” (5) “Lack of emotional clarity,” and (6) “Limited access to emotion regulation strategies.” Higher scores indicate greater problems with emotion regulation. In this study we considered only the Total Scores that range from 36 to 180. There are no standardized clinical cutoffs for this measure, however prior research suggests that the clinical range on the DERS total score varies from averages of approximately 80 to 127 [50].

- −

- The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) [51]. The DEBQ is a 33-item self-report questionnaire that assesses three distinct eating behaviors in adults: (1) emotional eating, (2) external eating, and (3) restrained eating. Items on the DEBQ range from 1 (never) to 5 (very often), with higher scores indicating greater endorsement of the eating behavior. Similar to the DERS, there are no standardized clinical cutoffs. Research community samples suggest a score > 3.25 as the 80% percentile.

- −

- Frequency of disordered eating. At the beginning of each session in both conditions, therapists assessed the participant’s frequency of disordered eating. This information was entered into a Therapist Note on Qualtrics. Preliminary signals of effectiveness were determined by changes in the frequency of disordered eating behaviors over the previous 7 days [e.g., number of EE episodes, evaluation of the trend of EE, number of objective binge episodes (OBEs), subjective binge episodes (SBEs), purging episodes]. EE episode frequency was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale: Never (1), Seldom (2), Sometimes (3), Often (4), Always (5). Binge episodes were distinguished as objective or subjective as defined by the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q). OBEs and SBEs episodes were assessed asking for a specific number of episodes over prior week.

- −

- The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II) [52]. This seven-item measure assesses for psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Items range from 1 (never true) to 7 (always true). The scale is scored by summing the seven items. Higher total scores indicate less flexibility, while lower total scores mean more flexibility (total range: 7-49).

- −

- - Weight Efficacy Life-Style Questionnaire (WELSQ) [53]. The Weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire (WELSQ) is a commonly used measure of eating self-efficacy consisting of 20-items and five situational factors (negative emotions, availability, social pressure, physical discomfort, positive activities). Respondents rate their confidence to resist eating in certain situations on a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not confident) to 9 (very confident). The WELSQ yields five subscales’ scores ranging from 0-36. High WELSQ scores indicate a higher self-efficacy to resist eating.

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Feasibility

3.2.1. Therapists

3.2.2. Patients

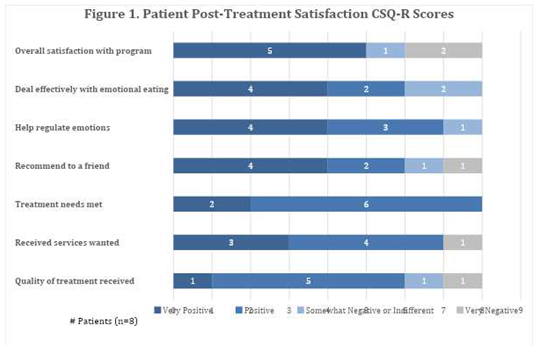

3.3. Acceptability

3.3.1. VE-ER Intervention

3.3.2. TAU Treatment

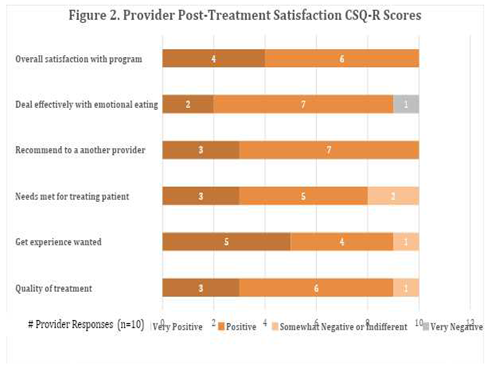

3.3.3. Therapists’ Satisfaction with Virtual Intervention

3.4. Exploratory Outcomes of Effectiveness

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McRae, K.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation. Emotion 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vintró-Alcaraz, C.; Munguía, L.; Granero, R.; Gaspar-Pérez, A.; Solé-Morata, N.; Sánchez, I.; Sánchez-González, J.; Menchón, J.M.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Fernández-Aranda, F. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic factor in eating disorders and gambling disorder: Treatment outcome implications. J Behav Addict 2022, 11, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenberger, J.; Schnepper, R.; Arend, A.-K.; Blechert, J. Emotional eating in healthy individuals and patients with an eating disorder: Evidence from psychometric, experimental and naturalistic studies. Proc Nutr Soc 2020, 79, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricca, V.; Castellini, G.; Lo Sauro, C.; Ravaldi, C.; Lapi, F.; Mannucci, E.; Rotella, C.M.; Faravelli, C. Correlations between binge eating and emotional eating in a sample of overweight subjects. Appetite 2009, 53, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, R.; Shuval, K.; Li, Q.; Oetjen, R.; Drope, J.; Yaroch, A.L.; Fennis, B.M.; Harding, M. Emotional eating in adults: The role of sociodemographics, lifestyle behaviors, and self-regulation—Findings from a U.S. national study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemanian, M.; Mæland, S.; Blomhoff, R.; Rabben, Å.K.; Arnesen, E.K.; Skogen, J.C.; Fadnes, L.T. Emotional eating in relation to worries and psychological distress amid the covid-19 pandemic: A population-based survey on adults in Norway. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchetto, C.; Aiello, M.; Gentili, C.; Ionta, S.; Osimo, S.A. Increased emotional eating during COVID-19 associated with lockdown, psychological and social distress. Appetite 2021, 160, 105122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braden, A.; Musher-Eizenman, D.; Watford, T.; Emley, E. Eating when depressed, anxious, bored, or happy: Are emotional eating types associated with unique psychological and physical health correlates? Appetite 2018, 125, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarevich, I.; Irigoyen Camacho, M.E.; Velázquez-Alva, M.D.C.; Zepeda Zepeda, M. Relationship among obesity, depression, and emotional eating in young adults. Appetite 2016, 107, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.L.; Appelhans, B.M.; Whited, M.C.; Oleski, J.; Pagoto, S.L. Trait anxiety, but not trait anger, predisposes obese individuals to emotional eating. Appetite 2010, 55, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Rodriguez, S.T.; Chou, C.-P.; Unger, J.B.; Spruijt-Metz, D. BMI as a moderator of perceived stress and emotional eating in adolescents. Eat Behav 2008, 9, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchanturia, K.; Davies, H.; Harrison, A.; Fox, J.R.E.; Treasure, J.; Schmidt, U. Altered social hedonic processing in eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2012, 45, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.J.; Nowson, C.A. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition 2007, 23, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, A.E.; Lee, M.; Price, M.; Williams, C. A Serial mediation model of the relationship between alexithymia and BMI: The role of negative affect, negative urgency and emotional eating. Appetite 2019, 133, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.C.; Chow, C.M. Stress and Emotional Eating: The mediating role of eating dysregulation. Personality and Individual Differences 2014, 66, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, M.; Mingarelli, A.; Guarino, A.; Favieri, F.; Boncompagni, I.; Germanò, R.; Germanò, G.; Forte, G. Alexithymia: A facet of uncontrolled hypertension. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2019, 146, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.J.; Parker, J.D.; Bagby, R.M.; Bourke, M.P. Relationships between Alexithymia and psychological characteristics associated with eating disorders. J Psychosom Res 1996, 41, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, A.J.; Lewis, V.J.; Booth, D.A. Does emotional eating interfere with success in attempts at weight control? Appetite 1990, 15, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayn, M.; Knäuper, B. Emotional eating and weight in adults: A review. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues 2018, 37, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, L.R.; Porter, A.M. Weight stigma and eating behavior: A review of the literature. Appetite 2016, 102, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michopoulos, V.; Powers, A.; Moore, C.; Villarreal, S.; Ressler, K.J.; Bradley, B. The mediating role of emotion dysregulation and depression on the relationship between childhood trauma exposure and emotional eating. Appetite 2015, 91, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katterman, S.N.; Kleinman, B.M.; Hood, M.M.; Nackers, L.M.; Corsica, J.A. Mindfulness meditation as an intervention for binge eating, emotional eating, and weight loss: A systematic review. Eat Behav 2014, 15, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulac, J.; Sandre, D.; Mercer, D. Impact on mindfulness, emotion regulation, and emotional overeating of a DBT skills training group: A Pilot Study. Eat Weight Disord 2019, 24, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattimore, P. Mindfulness-based emotional eating awareness training: Taking the emotional out of eating. Eat Weight Disord 2020, 25, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraets, C.N.W.; van der Stouwe, E.C.D.; Pot-Kolder, R.; Veling, W. Advances in immersive virtual reality interventions for mental disorders: A new reality? Curr Opin Psychol 2021, 41, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, D.; Díaz-García, A.; Fernandez-Álvarez, J.; Botella, C. Virtual reality for the enhancement of emotion regulation. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 2021, 28, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Vogel, E.N.; Adler, S.; Bohon, C.; Bullock, K.; Nameth, K.; Riva, G.; Safer, D.L.; Runfola, C.D. Bringing virtual reality from clinical trials to clinical practice for the treatment of eating disorders: An example using virtual reality cue exposure therapy. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020, 22, e16386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, A.; Mancini, F. Rescripting memory, redefining the self: A meta-emotional perspective on the hypothesized mechanism(s) of imagery rescripting. Front Psychol 2018, 9, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arntz, A. Imagery rescripting as a therapeutic technique: Review of clinical trials, basic studies, and research agenda. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology 2012, 3, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G.; Malighetti, C.; Serino, S. Virtual reality in the treatment of eating disorders. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 2021, 28, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, A.; Welch, E.; Zha, C.; Holmes, E.A. Imagery rescripting for reducing body image dissatisfaction: A randomized controlled trial. Cogn Ther Res 2022, 46, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morina, N.; Lancee, J.; Arntz, A. Imagery rescripting as a clinical intervention for aversive memories: A meta-analysis. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2017, 55, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G. The key to unlocking the virtual body: Virtual reality in the treatment of obesity and eating disorders. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2011, 5, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G. Virtual reality in clinical psychology. Comprehensive Clinical Psychology 2022, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. Six views of embodied cognition. Psychon Bull Rev 2002, 9, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G. The neuroscience of body memory: From the self through the space to the others. Cortex 2018, 104, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L.F. The theory of constructed emotion: An active inference account of interoception and categorization. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 2017, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett-Cheetham, E.; Williams, L.A.; Bednall, T.C. A differentiated approach to the link between positive emotion, motivation, and eudaimonic well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2016, 11, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A. Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain; Self comes to mind: Constructing the conscious brain; Pantheon/Random House: New York, NY, US, 2010; pp. xi, 367. ISBN 978-0-307-37875-0. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio, A.; Carvalho, G.B. The nature of feelings: Evolutionary and neurobiological origins. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013, 14, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malighetti, C.; Schnitzer, C.; Potter, G.; Nameth, K.; Brown, T.; Vogel, E.; Riva, G.; Runfola, C.D.; Safer, D.L. Rescripting emotional eating with virtual reality: A Case Study. Annual Review of Cybertherapy and Telemedicine 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Malighetti, C.; Bernardelli, L.; Pancini, E.; Riva, G.; Villani, D. Promoting Emotional and Psychological Well-being during COVID-19 Pandemic: A self-help virtual reality intervention for university students. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2023, 26, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G.; Malighetti, C.; Chirico, A.; Di Lernia, D.; Mantovani, F.; Dakanalis, A. Virtual reality. In Rehabilitation interventions in the patient with obesity; Capodaglio, P., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 189–204. ISBN 978-3-030-32274-8. [Google Scholar]

- Riva, G.; Bernardelli, L.; Castelnuovo, G.; Di Lernia, D.; Tuena, C.; Clementi, A.; Pedroli, E.; Malighetti, C.; Sforza, F.; Wiederhold, B.K.; et al. A virtual reality-based self-help intervention for dealing with the psychological distress associated with the COVID-19 lockdown: An Effectiveness Study with a Two-Week Follow-Up. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D.; Van Rheenen, T.E.; Neill, E.; Phillipou, A.; Tan, E.J.; Toh, W.L.; Sumner, P.J.; Rossell, S.L. Surviving the COVID-19 pandemic: An examination of adaptive coping strategies. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahimanesh, S.; Serino, S.; Tuena, C.; Di Lernia, D.; Wiederhold, B.K.; Bernardelli, L.; Riva, G.; Moradi, A. Effectiveness of a virtual-reality-based self-help intervention for lowering the psychological burden during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a randomized controlled trial in Iran. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, A.C.; Davis, L.L.; Kraemer, H.C. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatr Res 2011, 45, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, D.L.; Attkisson, C.C.; Hargreaves, W.A.; Nguyen, T.D. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann 1979, 2, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.; Sullivan, S.; Tchanturia, K.; Treasure, J. Emotional functioning in eating disorders: Attentional bias, emotion recognition and emotion regulation. Psychol Med 2010, 40, 1887–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Strien, T.; Frijters, J.E.; Bergers, G.P.; Defares, P.B. The Dutch eating behavior questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1986, 5, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyndall, I.; Waldeck, D.; Pancani, L.; Whelan, R.; Roche, B.; Dawson, D.L. The acceptance and action questionnaire-II (AAQ-II) as a measure of experiential avoidance: Concerns over discriminant validity. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 2019, 12, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navidian A reliability and validity of the weight efficacy lifestyle questionnaire in overweight and obese individuals. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences 2009, 3, 217–222.

- Brownley, K.A.; Berkman, N.D.; Peat, C.M.; Lohr, K.N.; Cullen, K.E.; Bann, C.M.; Bulik, C.M. Binge-eating disorder in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2016, 165, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zwaan, M.; Herpertz, S.; Zipfel, S.; Svaldi, J.; Friederich, H.-C.; Schmidt, F.; Mayr, A.; Lam, T.; Schade-Brittinger, C.; Hilbert, A. Effect of internet-based guided self-help vs individual face-to-face treatment on full or subsyndromal binge eating disorder in overweight or obese patients: The INTERBED Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runfola, C.D.; Kirby, J.S.; Baucom, D.H.; Fischer, M.S.; Baucom, B.R.W.; Matherne, C.E.; Pentel, K.Z.; Bulik, C.M. A pilot open trial of UNITE-BED: A couple-based intervention for binge-eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2018, 51, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safer, D.L.; Robinson, A.H.; Jo, B. Outcome from a randomized controlled trial of group therapy for binge eating disorder: Comparing dialectical behavior therapy adapted for binge eating to an active comparison group therapy. Behav Ther 2010, 41, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsoff, S.; Pullmer, R.; Cyr, M.; Aime, H. The role of the therapeutic alliance in eating disorder treatment outcomes: A systematic review. Eat Disord 2015, 23, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G.; Malighetti, C.; Serino, S. Virtual reality in the treatment of eating disorders. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 2021, 28, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingemans, A.; Danner, U.; Parks, M. Emotion regulation in binge eating disorder: A review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surmay, C.; Vo, M.; Derenne, J.; Sherman, D. Virtual reality mindfulness therapy for anxiety and pain management in adolescent and young adult patients with eating disorders. Journal of Adolescent Health 2020, 66, S62–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, D.; Xu, N.; Yang, J. The effectiveness of immersive virtual reality (VR) based mindfulness training on improvement mental-health in adults: A narrative systematic review. Explore (NY) 2023, 19, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, G.; Wiederhold, B.K.; Mantovani, F. Neuroscience of virtual reality: From virtual exposure to embodied medicine. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2019, 22, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanova, E.; Quesnel, D.; Riecke, B. Understanding AWE: can a virtual journey, inspired by the overview effect, lead to an increased sense of interconnectedness? Frontiers in Digital Humanities 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Waltz, T.; Zettle, R.D. Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav Ther 2011, 42, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Virtual Scenarios* | Description |

|---|---|

|

The Secret Garden (duration 13:10 minutes) is characterized by a tranquil nature scene intended to help the viewer immediately perceive a sense of calm. Throughout the video the narrative voice guides participants on a walk around a garden on a sunny day. |

|

The Waterfall in the Prairie (duration 14:13 minutes) scenario takes participants on a walk in a prairie that leads them to a waterfall. As in the first video, this scenario aims to help the participant experience calm and greater awareness of their sensations. |

|

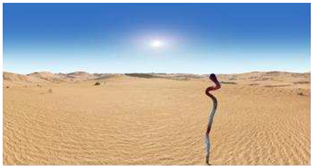

The Desert and the Oasis (duration 11:32 minutes) shows a stark and desolate environment. Here participants faced a sandstorm and a scorpion, a symbol of menace, which is overcome by participants in order to return to a more peaceful path. Themes such as loneliness, abandonment, silence, and survival may surface. |

|

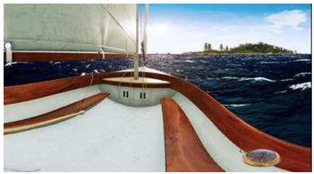

The Boat and the Sea (duration 11:12 minutes) involves a journey in a boat, during which a strong storm takes place, perhaps symbolizing a moment of difficulty or anxiety experienced in real life. Participants managed to overcome the storm, and re-experience clear skies and a serene view of the shore. |

|

The Mountain and the Backpack (duration 13:32 minutes), is a walk along a path in the mountains, during which a heavy stone in a backpack is transformed into a lighter stone, enabling the journey to continue more easily. The scenario involves themes such as challenges, discovery, goals to achieve, resilience, and spirituality. |

|

In the final video, The Hero and the Dragon (duration 14:05 minutes), participants encounter a frightening dragon that becomes smaller and smaller throughout the video. Participants then manage to reach a door that leads to a treasure chest from which a light emanates, symbolizing the achievement of goals and increasing awareness of their own resources in the face of difficulties. *Images courtesy of Become-hub. |

| Emotion Regulation Sessions | The Role of the Experimenter |

| Introduction to the first two immersive experiences (5 minutes) | Remind patient of the purpose of the emotion regulation intervention and how the intervention will be administered. “We will now turn to the emotion regulation intervention. As a reminder, the purpose of this intervention is to help you to increase your awareness and ability to recognize your emotional states. I will begin with helping you focus on the present moment and your body. Then you will be immersed in a waterfall landscape and a voice will guide you in the exploration of this scene. The voice will encourage you to pay attention to physical sensations, your breath and to the environment. After the immersive experience we will talk about your feeling and thoughts about what you experienced. Let me know if you have any questions or need a break.” |

| Focus on Attention (5 minutes) |

“If you aren’t already, please sit in a comfortable position, letting your back adopt a straight but not rigid posture. A dignified and comfortable posture, with the soles of your feet parallel to the ground and your legs uncrossed. Place your hands comfortably on your thighs or on your lap. And if you feel comfortable, you can gently close your eyes or keep your eyes open, with a soft, unfocused gaze. When you are ready, bring your awareness to the level of your physical sensations, directing your attention to the sensations, pressure and friction in your body at the points where your body is in contact with the chair or whatever is supporting you. Spend a few moments exploring these sensations, in your feet, in your legs, and your hands, back, etc [pause]. And now direct your attention and focus it on the flow of physical sensations in your abdomen, while the air enters and exits the body [pause]. Try to connect yourself with the flow of the physical sensations in the abdomen for the entire duration of each inhalation and exhalation [pause]. There is no need to try to control your breathing, just let it go [pause]. As you continue to focus awareness on the bodily sensations of the area that enters and exits, sooner or later your mind may move away from the breath, perhaps wandering aimlessly, or be taken over by a thought, a project, a fantasy [pause]. This wandering and being distracted is a normal thing, not a mistake or a failure [pause]. When you notice that your attention is no longer on the breath, pause for a moment to see where the mind has gone, congratulating yourself for being aware of your experience in the moment [pause]. Then, voluntarily turn your attention away from what distracted you and gently bring it back to the sensation of breathing, by focusing completely on breathing in and out. [pause]. Remind yourself from time to time that your only goal is to be aware of your experience moment by moment, the best you can; and that breathing is available to you at all times, when you need an anchor to bring you back to the present moment [pause]. And now, when you're ready, slowly emerge from this experience, redirecting your attention to space and time.” [note: If possible, continue straight from this experience to the immersive environment to avoid moving the focus away from their focus on their bodily experience. If the person appears uncomfortable or voices any concerns, the therapist can feel free to ask about the experience. For example, you can ask: “What was it like to breathe in and out, focus on the breath, have your mind wander, etc?) |

| VR Scenarios (12 minutes) | Session 1: The Secret Garden Introduce Scene: “We will now start the secret garden immersive experience. In the secret garden experience, we will guide you through a protected place (a large but closed natural garden) where you will find access to a new, internal, world of well-being and awareness (through the portal of the cherry trees). Session 2: The Waterfall and the Prairie Introduce Scene: “In addition to the main goal of promoting relaxation, this experience, specifically, will help you lighten your thoughts and emotions providing a safety and protection feeling (an open but safe natural place protected by streams and fences).” |

| Identification of the safe place (5 minutes) |

After the immersive experience, ask the patient to think through the immersive experience and identify the moment of greatest well-being and serenity. For example: “Go back with your mind to the immersive journey and try to remember the moment when you felt the greatest sense of well-being or serenity. Describe the place and the feeling” If they did not experience a sense of well-being or serenity, therapist can ask what “positive” or “neutral” emotions they felt at any point. Let them describe where they felt them in the scene. |

| Anchoring the New Somatic Marker (10 minutes) |

Create an anchor by linking the positive emotion experienced in the virtual environment to a real experience the patient had in the “real world.” Let them close their thumb between their 4 fingers while they are retrieving the real-life experience. “Now, close your eyes, and --focusing on the emotion that you felt in the VR-- try to recall in your mind an experience that you had in your real life in which you felt this emotion. As you recall this event, close your thumb between the 4 fingers of your hand. Feel the contact of your thumb on your skin and recall as many details as possible. If you feel comfortable, could you share this event with me?” Let them describe the real-life experience in great detail to you. [The greater the detail, the more vivid the recollection and the subsequent re-experience.] “Every time that you need to feel this emotion you can make this gesture with your hands. This will bring you back to this present moment and to this positive sensation”. |

| Homework | Patients at the end of the experience will receive a mp3 or video copy of this immersive experience in order to practice it every day at home before breakfast or in a particular emotional moment of the day. “I will email you the mp3 and video of this VR experience. Try to listen or watch it before breakfast. This might help you to be more focused as well as more aware of yourself and of what you truly need. If you feel anxious or the urge to eat, try to listen this audio, and make the gesture with your hands that you’ve already learned. We are trying to help you to be more aware of what is happening in your body and to teach you some skills to face the obstacles that you may meet in your real life.” |

| Emotional Rescripting Sessions | The Role of Experimenter |

| Check in & review homework (5 minutes) |

“How did the homework go last week with listening (or watching) the… scenarios?” If completed, process experiences (thoughts and feelings) to facilitate new learning. Use CBT/DBT strategies. If not completed, assess barriers to completion and problem solve around overcoming barriers. |

| Assessment: Therapist Note | Assessment of any changes to emotional eating? (Obtain frequency of behaviors—OBEs, SBEs, and purges, as well as assess presence of emotional eating using the following scale: never, seldom, sometimes, often, always) Any changes to emotional eating compared to last session? (same, worse, better) |

| Brief Introduction to Rescripting Immersive Experiences |

The somatic marker theory posits that emotions are changes in both our body and brain states. Over time, emotions and their corresponding bodily changes, which are called "somatic markers", become associated with particular situations and their past outcomes. These changes are autonomic and reflect prior experience of that event, usually a negative consequence. Once formed, the somatic markers are reactivated every time the person encounters similar situations to those that originally induced the emotion reaction. The reactivation of the somatic markers reclaims the associated body state. For example, if you were judged in high school for what you ate-- causing understandable negative somatic experiences of anxiety, shame, rapid heartbeat, sweating, etc., then every time you ate in front of those peers, your body may have “memorized” the connection between the negative internal states and eating with others. As such, you might find the same feelings of discomfort present later in life even when those reactions wouldn’t make sense, for example, when eating with friends who make you feel safe and have never judged or criticized your eating before. An improvement in managing emotions then must depend on a change in the somatic memory of the body. If we experience a negative situation similar to one that we met in the past, our body reproduces the same answers learned in the past (due to body memory). This makes change impossible. It is necessary to rescript this automatic mechanism (somatic marker) to modify the emotional experience. We know that an individual’s awareness and understanding of emotions may constitute a necessary step to successfully regulate the emotions. |

| Focus on attention exercise (5 minutes). | The same script of previous sessions |

| VR Scenarios: The Desert and the Oasis Experience; The Mountain and the Backpack; The Boat and the Sea; The Hero and the Dragon |

Introduce Scene: “You will be immersed in a metaphorical journey through ….., holding a …. like object in your hand” [if in person session, can add: “that I will give you at the right time.”]. The immersive experience will take 10 minutes. After, we will talk about what you felt and thought during this journey”. During the experience, therapists should observe patients’ behavior silently. This observation of the patient’s body language can offer useful information. If the patient appears very distressed, for example and the therapists feel the need to intervene, the therapist could stop the video and take a moment to discuss with him/her what they are experiencing and possibly insert a coping skill, reframe, reminder about how repeated exposure can help regulate emotions, etc.) As noted, please ask the patient to have a real object similating a … available to grab while they’re watching the video. When the narrative voice mentions the …, please remind the patient to grab the real walking stick in order to involve the body for the somatic marker modification. If patient doesn’t have access to a walking stick, therapist can suggest some alternatives as per above. |

| Emotion Evaluation (10 minutes) |

Purpose: The concretization of what patients felt during the immersive experience will lead them to be able to face and manage their emotions. Once the immersive experience is over, ask the patients to identify and localize in the body what they felt. For example: “Return with your mind to the immersive experience. How did it feel? Did you feel a negative or a positive emotion? If they felt both positive and negative emotions, start always with NEGATIVE. Then, after the desensitization, start with positive reinforcement. IF NEGATIVE: Once the emotion is identified, in case of negative experience it will be reduced or tolerated through the use of awareness and acceptance, physicalizing exercises (treating unwanted content as an object), defusion/desensitization exercises (making it move away to the horizon until it disappears; make it smaller and smaller until it disappears; make it decompose into many small pixels until it disappears), and/or containment Potential questions to ask: Close your eyes and return with your mind to the immersive experience: Q1. (Awareness): Focus on the different parts of your body, WHERE did you feel this emotion? Q2. (Physicalizing) Can you give a shape to this emotion? As a natural element, or a Geometric object. Q3. What color is emotion? Q4. Is the object moving or still? Q5.(Systematic desensitization) “Close your eyes and try to focus on the object. It is (color and the name of the object) and it starts to move counterclockwise. As it starts to move, it moves further and further away to the horizon, until it disappears, like a dot.” Or talk about small pixels that crumble and moves further and further away as a cloud that branches out and there is no more. If the patient does not manage to make the negative emotion disappear... You can have him/her imagine a drawer or a box where to put the emotion left (containment) or assist them in simply sitting with the emotion (to improve tolerance) IF POSITIVE: Once the emotion is identified, in case of positive experience it will be amplified. Close your eyes and return with your mind to the immersive experience: Q1. Focus on the different parts of your body, WHERE did you feel this emotion? Q2. Can you give a shape to this emotion? As a natural element, or a Geometric object. Q3. What color is the emotion? Q4. Is the object moving or still? “Now that you have noticed where you felt this emotion in your body and that you have seen its shape, and its color, try to imagine to breath inside this emotion. Every breath you take, the emotion expands throughout the body.” At this point: Anchor by linking the positive emotion experienced in the immersive environment to a real experience lived in the real world. For example: “Close your eyes and try to recall in your mind an experience that you lived in the real world in which you felt this positive emotion. “Close your thumb between your 4 fingers. Feel the contact with the thumb and try to recall an episode when you felt this same way. Try to retrieve as many details as possible.” This positive experience will be memorized in your body and will be available to you every time you need it by making the gesture and using the mp3. |

| Homework: | At the end of each session, patients will be asked to repeat the rescripting experience every day before bedtime, using a mp3 audio version of the experience and the real objects associated. The audio version of the intervention will lead the patient to relive the immersive experience by recreating in mind the emotional and somatic screenplay. |

| Summary of sessions | Theme |

|---|---|

| The Secret Garden | Build emotional awareness and strengthen mindfulness skills |

| The Waterfall and the Prairie | Build emotional awareness and strengthen mindfulness skills |

| The Desert and the Oasis | Continuing/proceeding despite adversity (sandstorm, scorpion). Somatic marker: a walking stick. |

| The Boat and the Sea | Using a/an (inner) compass to guide you, stay on course (i.e., values-directed action), see the bigger picture instead of overfocus on details, etc. Somatic marker: something that feels like a compass, such as the lid of a bottle or jar. |

| The Mountain and the Backpack | What is keeping the patient weighed down/stuck as they journey through life trying to achieve their goals? Somatic marker: a backpack that can be loaded (to be heavy) and then lightened. |

| The Hero and the Dragon | Patient is the hero of their own quest. Somatic marker: a key |

| Measures | VE-ER Group N=10 |

TAU Group N=11 |

t | Sign |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| DERS_TOT | 109.80±22.90 | 108.64±22.47 | .117 | .908 |

| DEBQ-R | 3.09±.79 | 2.78±.50 | 1.064 | .301 |

| DEBQ-E | 4.12±.49 | 3.55±1 | 1.634 | .119 |

| DEBQ-EXT | 3.35±.88 | 2.99±.60 | 1.093 | .288 |

| AAQ_II | 33.40±6.50 | 30.82±5.98 | .948 | .355 |

| WELSQ_NE | 9.90±6.80 | 15.73±6.21 | -2.051 | .054* |

| WELSQ_AV | 16.40±8.50 | 19.18±8.32 | -.757 | .458 |

| WELSQ_SP | 16.70±8.23 | 21.36±6.21 | .351 | .157 |

| WELSQ_PD | 17.20±9.36 | 20.18±6.94 | -.834 | .414 |

| WELSQ_PA | 22±5.59 | 24.45±4.84 | -1.092 | .288 |

| #OBES | 1.50±1.50 | .73±1.47 | .748 | .984 |

| #SBES | 1.70±1.98 | 3.43±2.57 | -1.962 | .951 |

| #PURGES | .60±1.35 | .64±2.11 | -.047 | .750 |

| #EE | 3.40±1.07 | 2.92±.90 | 1.26 | .222 |

| VE-ER Group (n=10) |

TAU Group (n=11) |

Anova | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Time | Group*time | ||

| Mean ±SD | Mean ±SD | Mean ±SD | Mean ±SD | F | Sig. | F | Sig. | |

| #EE | 3.40±1.07 | 1.90±.73 | 2.92±.90 | 2±.60 | 13.07 | .002* | 4.95 | .038* |

| #SBES | 1.70±1.98 | .80±1.13 | 3.43±2.57 | 1.42±1.24 | 9.29 | .007* | 2.69 | .117 |

| #Purge | .60±1.35 | 0±.00 | .64±2.11 | .45±1.50 | 3.03 | .098 | .869 | .363 |

| #OBES | 1.50±1.50 | .80±1.13 | .73±1.47 | .55±.88 | 7.61 | .012* | .005 | .947 |

| VE-ER Group | TAU Group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre N=10 |

Post N=5 |

Pre N=11 |

Post N=11 |

|||||

| Measures | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | z | Sign | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | z | Sign |

| DERS_TOT | 109.80±22.90 | 86±26.46 | -2.032 | .042* | 108.64±22.47 | 102.09±20.62 | -1.07 | .284 |

| DEBQ-R | 3.09±.79 | 2.66±.95 | -.674 | .500 | 2.78±.50 | 2.76±.72 | .089 | .929 |

| DEBQ-E | 4.12±.49 | 3.20±.67 | -1.753 | .060 | 3.55±1 | 3.38±.92 | -.561 | .575 |

| DEBQ-EXT | 3.35±.88 | 3.10±.99 | -1.604 | .109 | 2.99±.60 | 2.97±.49 | -.102 | .919 |

| AAQ_II | 33.40±6.50 | 30.20±10.68 | -1.095 | .273 | 30.82±5.98 | 29.91±7.36 | -.66 | .504 |

| WELSQ_NE | 9.90±6.80 | 18.80±5.63 | -1.753 | .070 | 15.73±6.21 | 15±5.86 | -.67 | .501 |

| WELSQ_AV | 16.40±8.50 | 20.80±9.49 | -944 | .354 | 19.18±8.32 | 16.82±8.08 | -.66 | -505 |

| WELSQ_SP | 16.70±8.23 | 23.40±7.05 | -1.214 | .225 | 21.36±6.21 | 19±11.27 | -81 | .413 |

| WELSQ_PD | 17.20±9.36 | 23.40±8.26 | .000 | 1 | 20.18±6.94 | 20.18±5.28 | -.35 | .720 |

| WELSQ_PA | 22.99±5.59 | 23.40±7.12 | -.406 | .684 | 24.45±4.69 | 22.36±6.57 | -.75 | .449 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).