Submitted:

10 November 2023

Posted:

13 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of GM-CSF

2.3. Exression and Purification of S100A7L2/G/Z Proteins

2.4. Surface Plasmon Resonance Studies

| L1 + A | → ← |

L1A | L2 + A | → ← |

L2A | (1) | |

|

kd1 Kd1 |

kd2 Kd2 |

2.5. Fluorimetric Studies

2.6. Chemical Crosslinking

2.7. Structural Modeling of the GM-CSF -‒ S100A4 Complex

2.8. Cell Viability Studies

2.9. Search of the Diseases Associated with GM-CSF and S100A4/A6/P Proteins

3. Results and Discussion

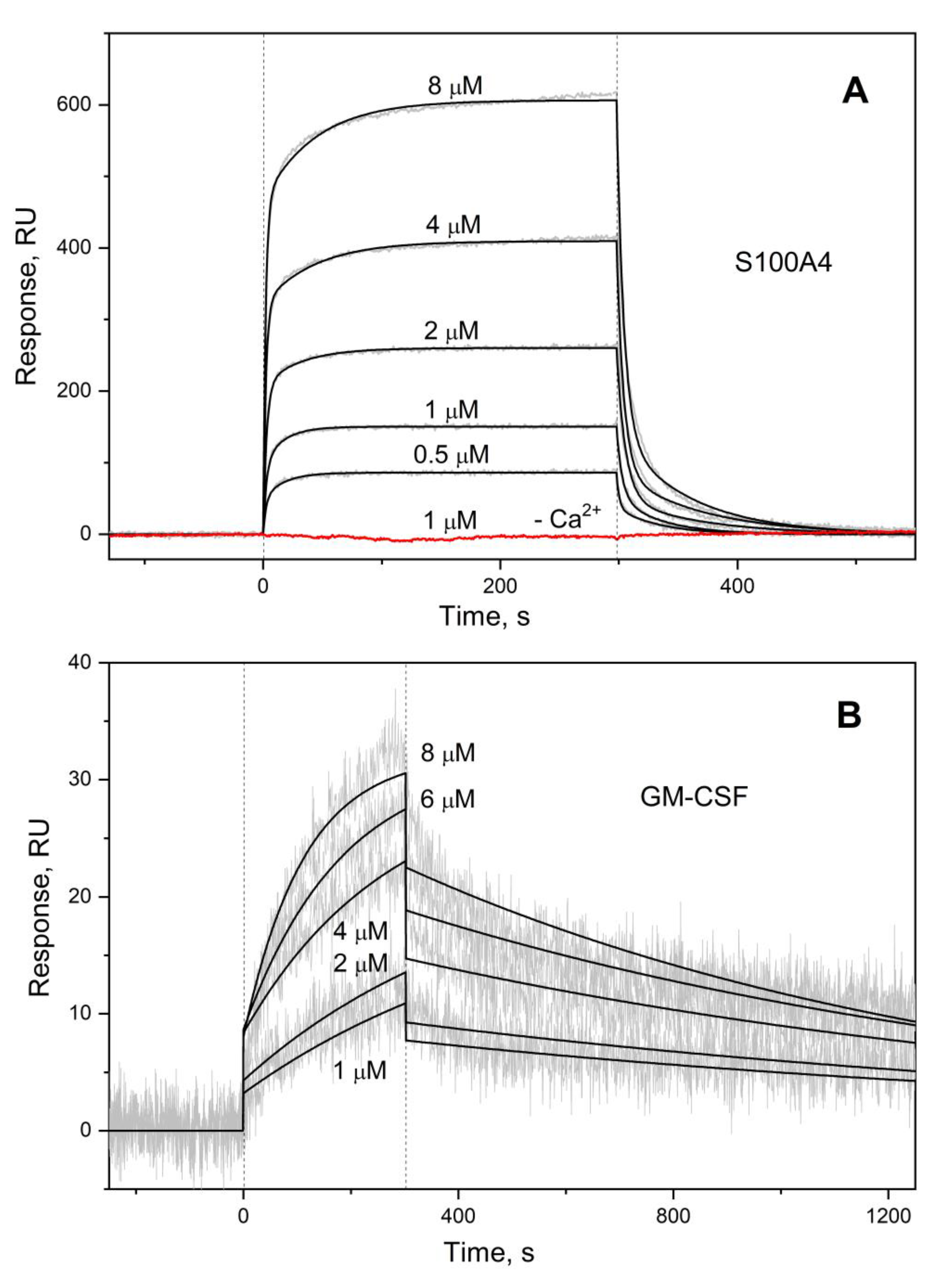

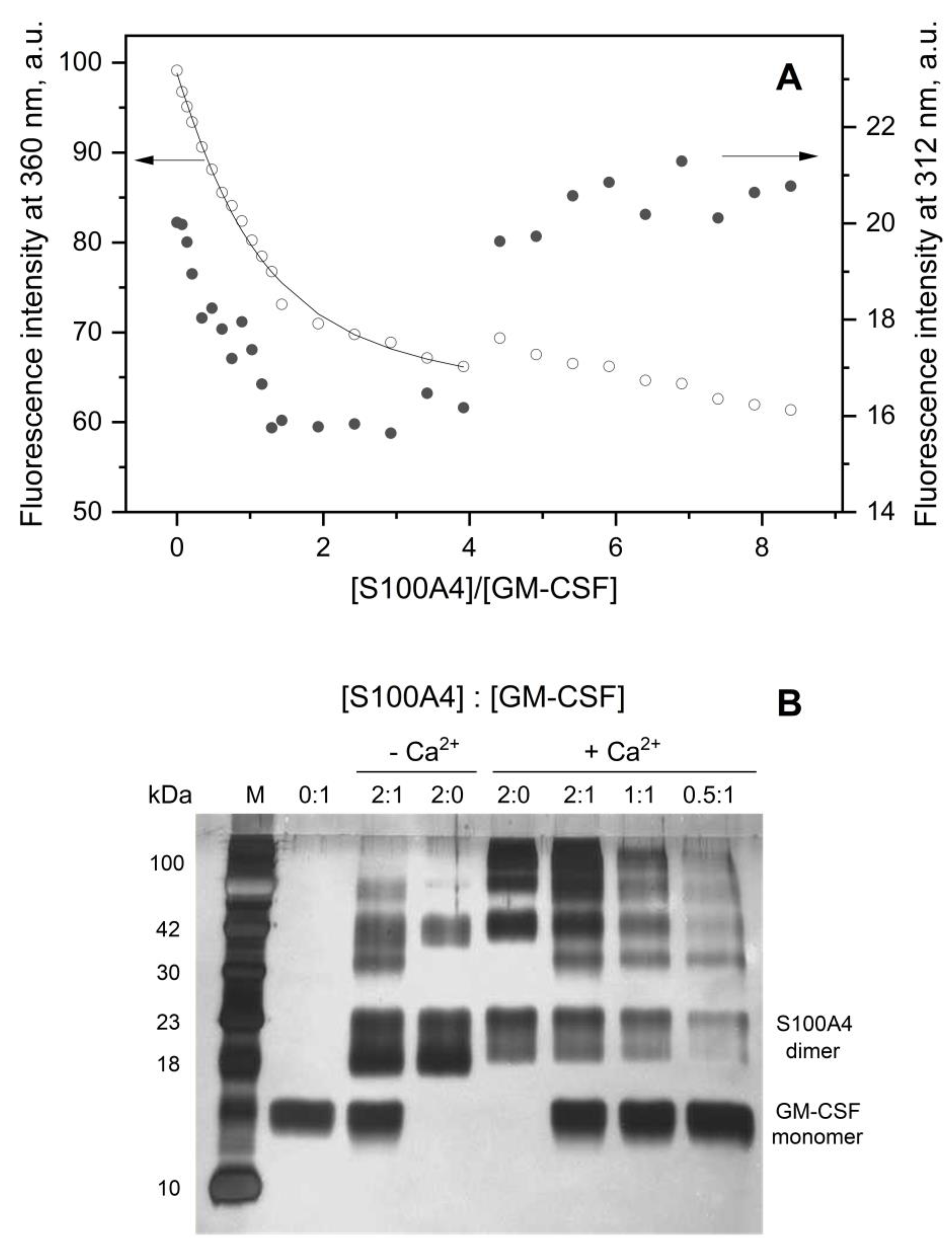

3.1. GM-CSF Binding to S100 Proteins

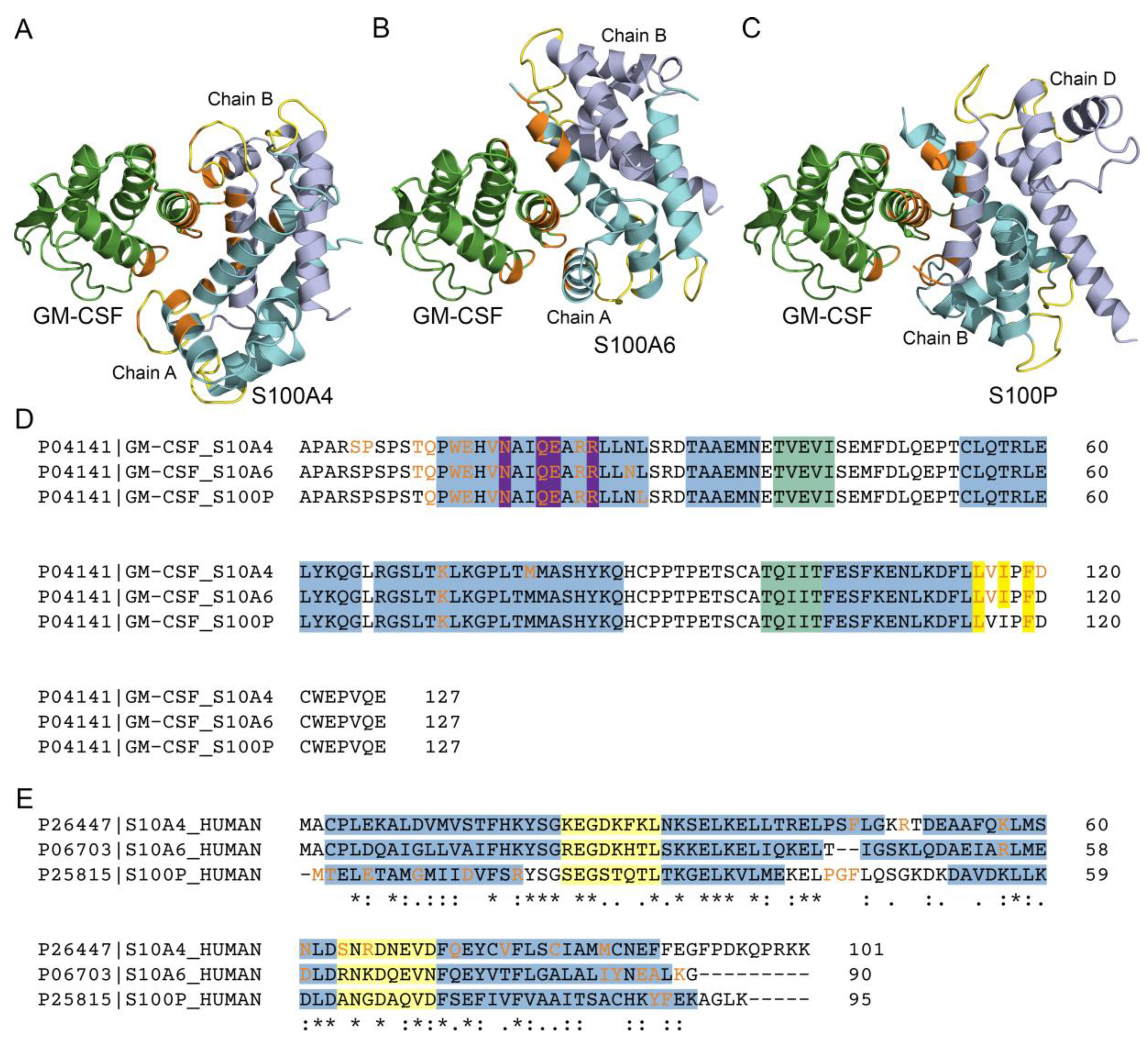

3.2. Structural Modeling of the GM-CSF ‒ S100A4 Complex

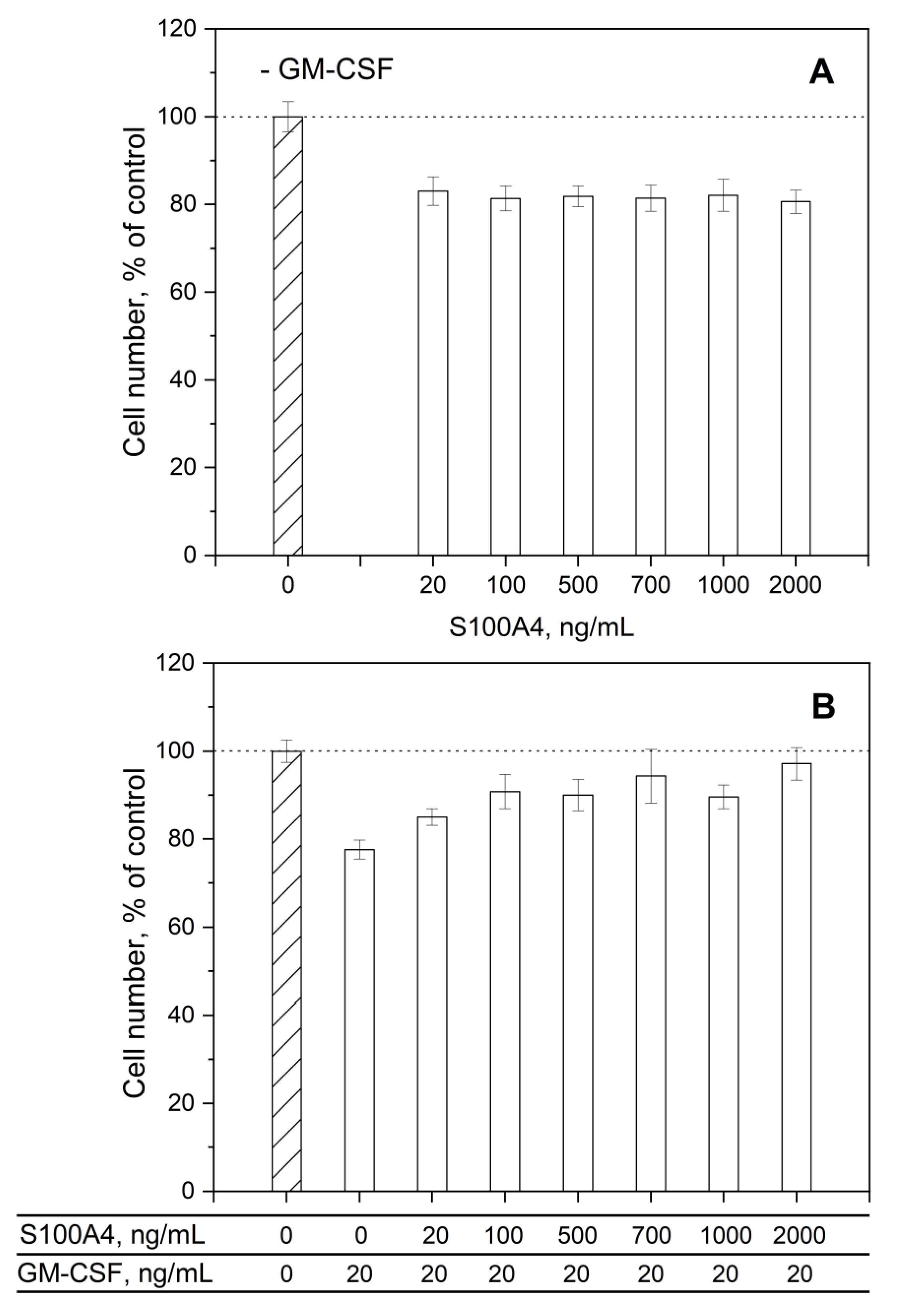

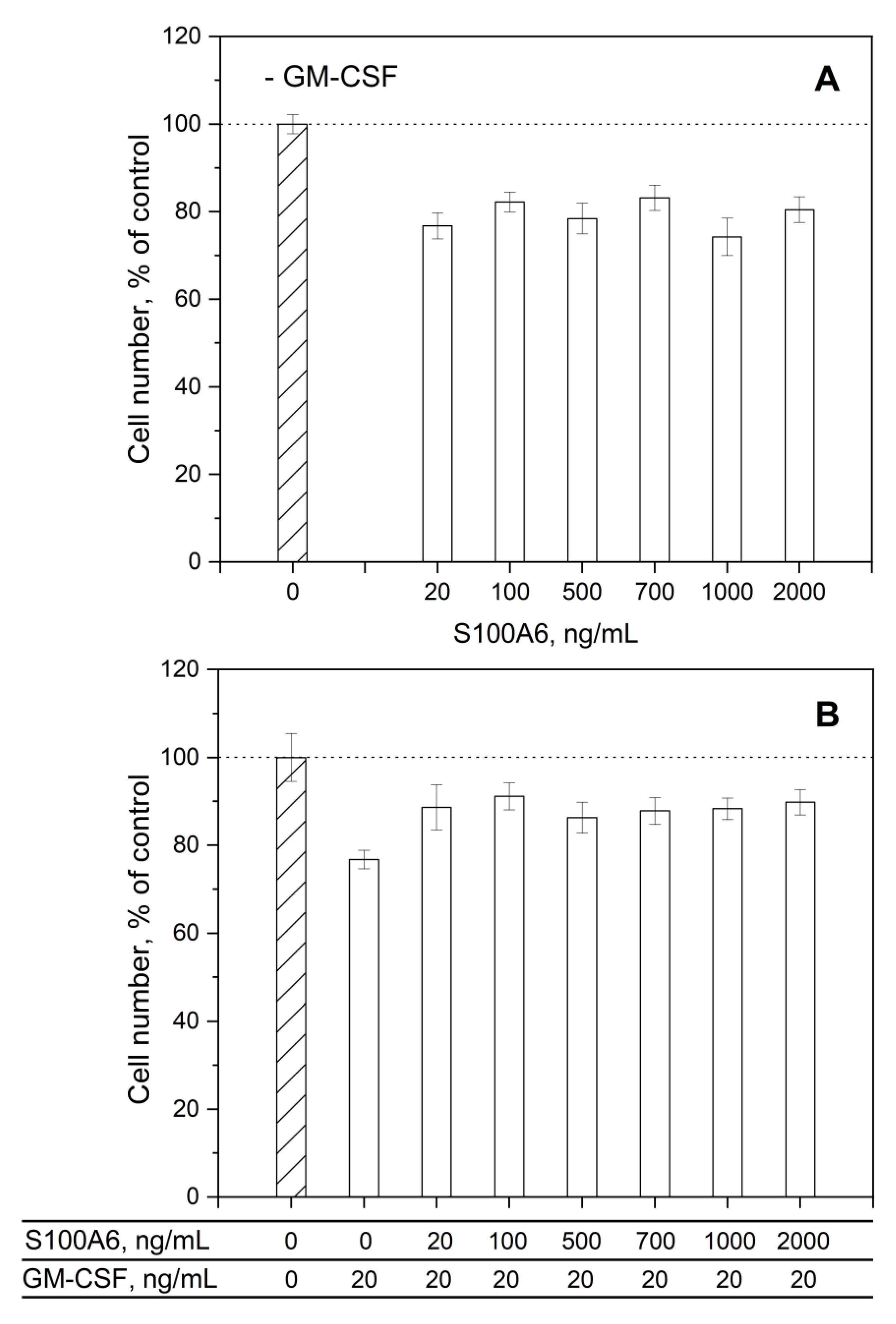

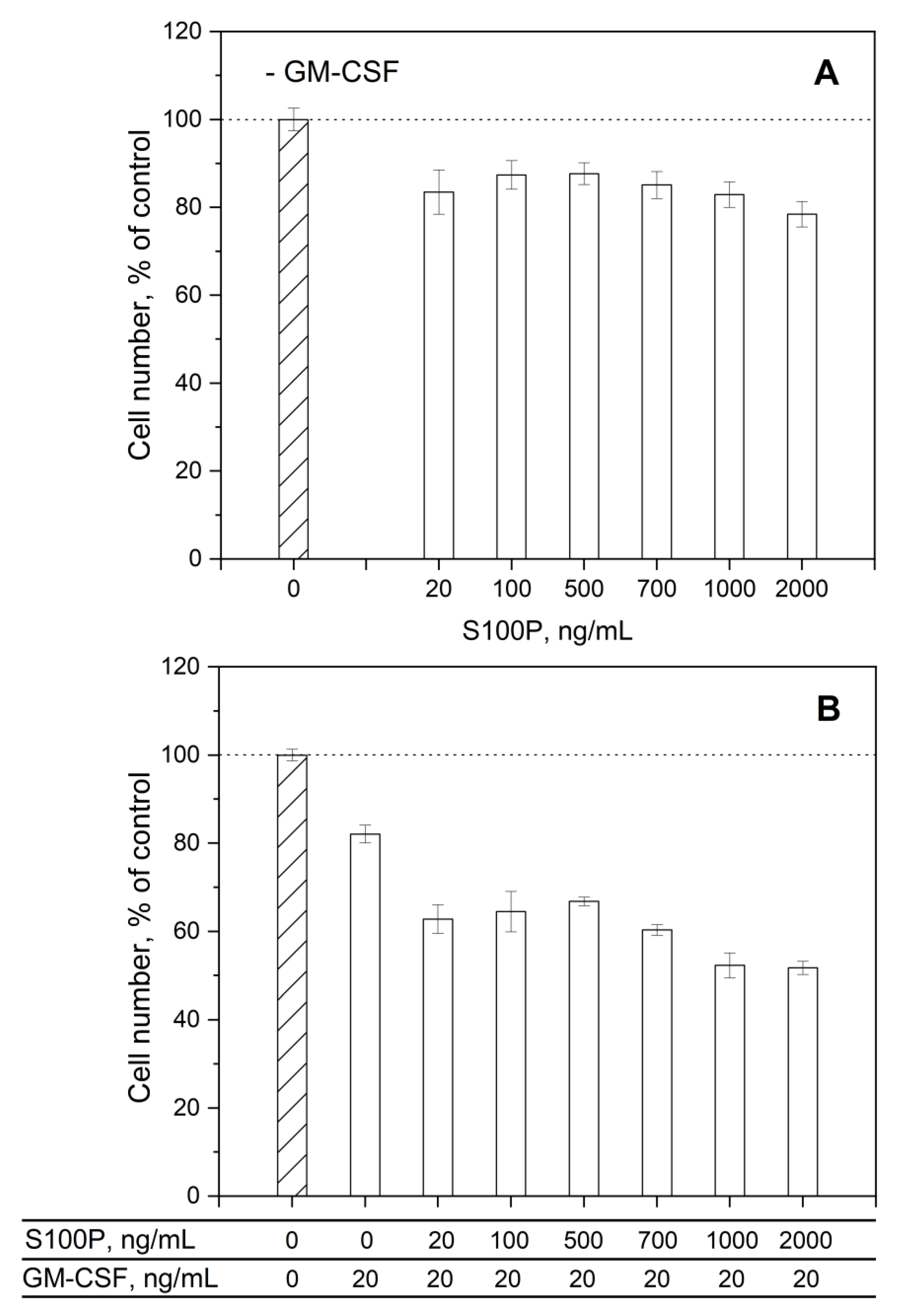

3.3. Impact of GM-CSF, S100 Proteins and Their Mixtures on Viability of THP-1 Cells

3.4. Human Diseases Associated with Dysregulation of GM-CSF and S100A4/A6/P Proteins

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Andreeva, A.; Kulesha, E.; Gough, J.; Murzin, A.G. The SCOP database in 2020: expanded classification of representative family and superfamily domains of known protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, D376–D382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hercus, T.R.; Kan, W.L.T.; Broughton, S.E.; Tvorogov, D.; Ramshaw, H.S.; Sandow, J.J.; Nero, T.L.; Dhagat, U.; Thompson, E.J.; Shing, K. , et al. Role of the beta Common (betac) Family of Cytokines in Health and Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pant, H.; Hercus, T.R.; Tumes, D.J.; Yip, K.H.; Parker, M.W.; Owczarek, C.M.; Lopez, A.F.; Huston, D.P. Translating the biology of β common receptor-engaging cytokines into clinical medicine. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023, 151, 324–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougan, M.; Dranoff, G.; Dougan, S.K. GM-CSF, IL-3, and IL-5 Family of Cytokines: Regulators of Inflammation. Immunity 2019, 50, 796–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becher, B.; Tugues, S.; Greter, M. GM-CSF: From Growth Factor to Central Mediator of Tissue Inflammation. Immunity 2016, 45, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, L.; Gessani, S. GM-CSF in the generation of dendritic cells from human blood monocyte precursors: recent advances. Immunobiology 2008, 213, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, M.; Zhang, C.; Méar, L.; Zhong, W.; Digre, A.; Katona, B.; Sjöstedt, E.; Butler, L.; Odeberg, J.; Dusart, P. , et al. A single-cell type transcriptomics map of human tissues. Sci Adv 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, J.A. GM-CSF in inflammation. J Exp Med 2020, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Taghi Khani, A.; Sanchez Ortiz, A.; Swaminathan, S. GM-CSF: A Double-Edged Sword in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 901277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasson, J.C. Molecular physiology of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood 1991, 77, 1131–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco-Cruz, A.; Aguilar-Santelises, M.; Ramos-Espinosa, O.; Mata-Espinosa, D.; Marquina-Castillo, B.; Barrios-Payan, J.; Hernandez-Pando, R. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: not just another haematopoietic growth factor. Med Oncol 2014, 31, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Thiruppathi, M.; Elshabrawy, H.A.; Alharshawi, K.; Kumar, P.; Prabhakar, B.S. GM-CSF: An immune modulatory cytokine that can suppress autoimmunity. Cytokine 2015, 75, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, M.S.; Gabrilove, J.L. Colony-stimulating factors. Curr Opin Oncol 1990, 2, 1152–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, B. Erythropoietin Receptor/beta Common Receptor: A Shining Light on Acute Kidney Injury Induced by Ischemia-Reperfusion. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 697796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.M.C.; Achuthan, A.A.; Hamilton, J.A. GM-CSF: A Promising Target in Inflammation and Autoimmunity. Immunotargets Ther 2020, 9, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.L.; Salerno, D.G.; Sadras, T.; Engler, G.A.; Kok, C.H.; Wilkinson, C.R.; Samaraweera, S.E.; Sadlon, T.J.; Perugini, M.; Lewis, I.D. , et al. The GM-CSF receptor utilizes beta-catenin and Tcf4 to specify macrophage lineage differentiation. Differentiation 2012, 83, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribechini, E.; Hutchinson, J.A.; Hergovits, S.; Heuer, M.; Lucas, J.; Schleicher, U.; Jordan Garrote, A.L.; Potter, S.J.; Riquelme, P.; Brackmann, H. , et al. Novel GM-CSF signals via IFN-gammaR/IRF-1 and AKT/mTOR license monocytes for suppressor function. Blood Adv 2017, 1, 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrowski, D.; Basle, M.; Lomri, A.; Marie, P.J. Syndecan-2 is involved in the mitogenic activity and signaling of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 9178–9185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebollela, A.; Cagliari, T.C.; Limaverde, G.S.; Chapeaurouge, A.; Sorgine, M.H.; Coelho-Sampaio, T.; Ramos, C.H.; Ferreira, S.T. Heparin-binding sites in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Localization and regulation by histidine ionization. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 31949–31956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiomi, A.; Usui, T. Pivotal roles of GM-CSF in autoimmunity and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm 2015, 2015, 568543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Budnick, I.; Singh, M.; Thiruppathi, M.; Alharshawi, K.; Elshabrawy, H.; Holterman, M.J.; Prabhakar, B.S. Dual Role of GM-CSF as a Pro-Inflammatory and a Regulatory Cytokine: Implications for Immune Therapy. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2015, 35, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, F.M.; Lee, K.M.; Teijaro, J.R.; Becher, B.; Hamilton, J.A. GM-CSF-based treatments in COVID-19: reconciling opposing therapeutic approaches. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaventura, A.; Vecchie, A.; Wang, T.S.; Lee, E.; Cremer, P.C.; Carey, B.; Rajendram, P.; Hudock, K.M.; Korbee, L.; Van Tassell, B.W. , et al. Targeting GM-CSF in COVID-19 Pneumonia: Rationale and Strategies. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotfi, N.; Thome, R.; Rezaei, N.; Zhang, G.X.; Rezaei, A.; Rostami, A.; Esmaeil, N. Roles of GM-CSF in the Pathogenesis of Autoimmune Diseases: An Update. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 25. Granulocyte Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor Market – Global Industry Analysis and Forecast (2022-2029); 69429; 2022.

- Kazakov, A.S.; Deryusheva, E.I.; Rastrygina, V.A.; Sokolov, A.S.; Permyakova, M.E.; Litus, E.A.; Uversky, V.N.; Permyakov, E.A.; Permyakov, S.E. Interaction of S100A6 Protein with the Four-Helical Cytokines. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakov, A.S.; Deryusheva, E.I.; Permyakova, M.E.; Sokolov, A.S.; Rastrygina, V.A.; Uversky, V.N.; Permyakov, E.A.; Permyakov, S.E. Calcium-Bound S100P Protein Is a Promiscuous Binding Partner of the Four-Helical Cytokines. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 12000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, G.; Heizmann, C.W. 3D Structures of the Calcium and Zinc Binding S100 Proteins. Handbook of Metalloproteins, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, R.; Cannon, B.R.; Sorci, G.; Riuzzi, F.; Hsu, K.; Weber, D.J.; Geczy, C.L. Functions of S100 proteins. Curr Mol Med 2013, 13, 24–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donato, R.; Cannon, B.R.; Sorci, G.; Riuzzi, F.; Hsu, K.; Weber, D.J.; Geczy, C.L. Functions of S100 Proteins. Curr Mol Med 2013, 13, 24–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreejit, G.; Flynn, M.C.; Patil, M.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Murphy, A.J.; Nagareddy, P.R. S100 family proteins in inflammation and beyond. Adv Clin Chem 2020, 98, 173–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Ali, S.A. Multifunctional Role of S100 Protein Family in the Immune System: An Update. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, D.; Foell, D.; Kessel, C. The role of S100 proteins in the pathogenesis and monitoring of autoinflammatory diseases. Mol Cell Pediatr 2018, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingelhofer, J.; Moller, H.D.; Sumer, E.U.; Berg, C.H.; Poulsen, M.; Kiryushko, D.; Soroka, V.; Ambartsumian, N.; Grigorian, M.; Lukanidin, E.M. Epidermal growth factor receptor ligands as new extracellular targets for the metastasis-promoting S100A4 protein. Febs J 2009, 276, 5936–5948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pankratova, S.; Klingelhofer, J.; Dmytriyeva, O.; Owczarek, S.; Renziehausen, A.; Syed, N.; Porter, A.E.; Dexter, D.T.; Kiryushko, D. The S100A4 Protein Signals through the ErbB4 Receptor to Promote Neuronal Survival. Theranostics 2018, 8, 3977–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, S.K.; Yu, C. The IL1alpha-S100A13 heterotetrameric complex structure: a component in the non-classical pathway for interleukin 1alpha secretion. The Journal of biological chemistry 2011, 286, 14608–14617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreira, C.M.; LaVallee, T.M.; Tarantini, F.; Jackson, A.; Lathrop, J.T.; Hampton, B.; Burgess, W.H.; Maciag, T. S100A13 is involved in the regulation of fibroblast growth factor-1 and p40 synaptotagmin-1 release in vitro. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1998, 273, 22224–22231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.A.; Chou, R.H.; Li, H.C.; Yang, L.W.; Yu, C. Structural insights into the interaction of human S100B and basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2): Effects on FGFR1 receptor signaling. Bba-Proteins Proteom 2013, 1834, 2606–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riuzzi, F.; Sorci, G.; Donato, R. S100B protein regulates myoblast proliferation and differentiation by activating FGFR1 in a bFGF-dependent manner. J Cell Sci 2011, 124, 2389–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakov, A.S.; Zemskova, M.Y.; Rystsov, G.K.; Vologzhannikova, A.A.; Deryusheva, E.I.; Rastrygina, V.A.; Sokolov, A.S.; Permyakova, M.E.; Litus, E.A.; Uversky, V.N. , et al. Specific S100 Proteins Bind Tumor Necrosis Factor and Inhibit Its Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 15956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakov, A.S.; Deryusheva, E.I.; Sokolov, A.S.; Permyakova, M.E.; Litus, E.A.; Rastrygina, V.A.; Uversky, V.N.; Permyakov, E.A.; Permyakov, S.E. Erythropoietin Interacts with Specific S100 Proteins. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakov, A.S.; Sofin, A.D.; Avkhacheva, N.V.; Denesyuk, A.I.; Deryusheva, E.I.; Rastrygina, V.A.; Sokolov, A.S.; Permyakova, M.E.; Litus, E.A.; Uversky, V.N. , et al. Interferon Beta Activity Is Modulated via Binding of Specific S100 Proteins. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 9473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakov, A.S.; Mayorov, S.A.; Deryusheva, E.I.; Avkhacheva, N.V.; Denessiouk, K.A.; Denesyuk, A.I.; Rastrygina, V.A.; Permyakov, E.A.; Permyakov, S.E. Highly specific interaction of monomeric S100P protein with interferon beta. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 143, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakov, A.S.; Sofin, A.D.; Avkhacheva, N.V.; Deryusheva, E.I.; Rastrygina, V.A.; Permyakova, M.E.; Uversky, V.N.; Permyakov, E.A.; Permyakov, S.E. Interferon-β Activity Is Affected by S100B Protein. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakov, A.S.; Sokolov, A.S.; Permyakova, M.E.; Litus, E.A.; Uversky, V.N.; Permyakov, E.A.; Permyakov, S.E. Specific cytokines of interleukin-6 family interact with S100 proteins. Cell Calcium 2022, 101, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakov, A.S.; Sokolov, A.S.; Vologzhannikova, A.A.; Permyakova, M.E.; Khorn, P.A.; Ismailov, R.G.; Denessiouk, K.A.; Denesyuk, A.I.; Rastrygina, V.A.; Baksheeva, V.E. , et al. Interleukin-11 binds specific EF-hand proteins via their conserved structural motifs. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2017, 35, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakov, A.S.; Sokolov, A.S.; Rastrygina, V.A.; Solovyev, V.V.; Ismailov, R.G.; Mikhailov, R.V.; Ulitin, A.B.; Yakovenko, A.R.; Mirzabekov, T.A.; Permyakov, E.A. , et al. High-affinity interaction between interleukin-11 and S100P protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015, 468, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bresnick, A.R. S100 proteins as therapeutic targets. Biophys Rev 2018, 10, 1617–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zha, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ma, T.; Li, H.; Liang, J. S100 proteins in cardiovascular diseases. Mol Med 2023, 29, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, D.; Anuradha, U.; Angati, A.; Kumari, N.; Singh, R.K. Pharmacological and Pathological Relevance of S100 Proteins in Neurological Disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2023, 22, 1403–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Dou, J.; Cui, P.; Zhu, J. S100P as a potential biomarker for immunosuppressive microenvironment in pancreatic cancer: a bioinformatics analysis and in vitro study. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, C.N.; Vajdos, F.; Fee, L.; Grimsley, G.; Gray, T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995, 4, 2411–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVallie, E.R.; DiBlasio, E.A.; Kovacic, S.; Grant, K.L.; Schendel, P.F.; McCoy, J.M. A thioredoxin gene fusion expression system that circumvents inclusion body formation in the E. coli cytoplasm. Biotechnology (N Y), 1993; 11, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, A.S.; Kazakov, A.S.; Solovyev, V.V.; Ismailov, R.G.; Uversky, V.N.; Lapteva, Y.S.; Mikhailov, R.V.; Pavlova, E.V.; Terletskaya, I.O.; Ermolina, L.V. , et al. Expression, Purification, and Characterization of Interleukin-11 Orthologues. Molecules 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catanzariti, A.M.; Soboleva, T.A.; Jans, D.A.; Board, P.G.; Baker, R.T. An efficient system for high-level expression and easy purification of authentic recombinant proteins. Protein Sci 2004, 13, 1331–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, E.A.; Emelyanenko, V.I. Log-normal description of fluorescence spectra of organic fluorophores. Photocem.Photobiol. 1996, 64, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, I.T.; Porter, K.A.; Xia, B.; Kozakov, D.; Vajda, S. Performance and Its Limits in Rigid Body Protein-Protein Docking. Structure 2020, 28, 1071–1081.e1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrodinger, LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8. 2015.

- Pinero, J.; Ramirez-Anguita, J.M.; Sauch-Pitarch, J.; Ronzano, F.; Centeno, E.; Sanz, F.; Furlong, L.I. The DisGeNET knowledge platform for disease genomics: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, D845–D855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho-Silva, D.; Pierleoni, A.; Pignatelli, M.; Ong, C.; Fumis, L.; Karamanis, N.; Carmona, M.; Faulconbridge, A.; Hercules, A.; McAuley, E. , et al. Open Targets Platform: new developments and updates two years on. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, D1056–D1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, E.; Fritz, G.; Vetter, S.W.; Heizmann, C.W. Binding of S100 proteins to RAGE: an update. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009, 1793, 993–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Niu, Z.; Guo, X.; Yuan, F.; Liu, Y. Serum S100 calcium binding protein A4 (S100A4, metatasin) as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in epithelial ovarian cancer. Br J Biomed Sci 2018, 75, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathuri, P.; Vogeley, L.; Luecke, H. Crystal structure of metastasis-associated protein S100A4 in the active calcium-bound form. J Mol Biol 2008, 383, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malashkevich, V.N.; Varney, K.M.; Garrett, S.C.; Wilder, P.T.; Knight, D.; Charpentier, T.H.; Ramagopal, U.A.; Almo, S.C.; Weber, D.J.; Bresnick, A.R. Structure of Ca2+-bound S100A4 and its interaction with peptides derived from nonmuscle myosin-IIA. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 5111–5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Permyakov, S.E.; Denesyuk, A.I.; Denessiouk, K.A.; Permyakova, M.E.; Kazakov, A.S.; Ismailov, R.G.; Rastrygina, V.A.; Sokolov, A.S.; Permyakov, E.A. Monomeric state of S100P protein: Experimental and molecular dynamics study. Cell Calcium 2019, 80, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.A.; Ecsedi, P.; Kovacs, G.M.; Poti, A.L.; Remenyi, A.; Kardos, J.; Gogl, G.; Nyitray, L. High-throughput competitive fluorescence polarization assay reveals functional redundancy in the S100 protein family. The FEBS journal 2020, 287, 2834–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, M.A.; Bartus, É.; Mag, B.; Boros, E.; Roszjár, L.; Gógl, G.; Travé, G.; Martinek, T.A.; Nyitray, L. Promiscuity mapping of the S100 protein family using a high-throughput holdup assay. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeira, F.; Park, Y.M.; Lee, J.; Buso, N.; Gur, T.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Basutkar, P.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Potter, S.C.; Finn, R.D. , et al. The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, W636–W641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Toro, N.; Shrivastava, A.; Ragueneau, E.; Meldal, B.; Combe, C.; Barrera, E.; Perfetto, L.; How, K.; Ratan, P.; Shirodkar, G. , et al. The IntAct database: efficient access to fine-grained molecular interaction data. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D648–D653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oughtred, R.; Rust, J.; Chang, C.; Breitkreutz, B.J.; Stark, C.; Willems, A.; Boucher, L.; Leung, G.; Kolas, N.; Zhang, F. , et al. The BioGRID database: A comprehensive biomedical resource of curated protein, genetic, and chemical interactions. Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society 2021, 30, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanput, W.; Mes, J.J.; Wichers, H.J. THP-1 cell line: an in vitro cell model for immune modulation approach. Int Immunopharmacol 2014, 23, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Matsuoka, N.; Temmoku, J.; Furuya-Yashiro, M.; Asano, T.; Sato, S.; Matsumoto, H.; Watanabe, H.; Kozuru, H.; Yatsuhashi, H. , et al. JAK inhibitors impair GM-CSF-mediated signaling in innate immune cells. BMC Immunol 2020, 21, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, H.; Schmittner, M.; Duschl, A.; Horejs-Hoeck, J. Residual endotoxin contaminations in recombinant proteins are sufficient to activate human CD1c+ dendritic cells. PLoS One 2014, 9, e113840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresnick, A.R.; Weber, D.J.; Zimmer, D.B. S100 proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2015, 15, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, X.; Zhang, H.M.; Jia, J.F.; Chen, S.S.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, X.L. Roles of S100 family members in drug resistance in tumors: Status and prospects. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Xu, C.; Jin, Q.; Liu, Z. S100 protein family in human cancer. Am J Cancer Res 2014, 4, 89–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Riuzzi, F.; Sorci, G.; Beccafico, S.; Donato, R. S100B engages RAGE or bFGF/FGFR1 in myoblasts depending on its own concentration and myoblast density. Implications for muscle regeneration. PLoS One 2012, 7, e28700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Analyte | Ligand | kd1, s-1 | Kd1, M | kd2, s-1 | Kd2, M |

| S100A4 | GM-CSF | (2.03 ± 0.70) × 10-2 | (4.71 ± 2.83) × 10-7 | (1.65 ± 0.32) × 10-1 | (2.43 ± 1.22) × 10-6 |

| S100A6 | (7.92 ± 4.02) × 10-4 # | (2.26 ± 1.18) × 10-6 # | (1.76 ± 0.49) × 10-2 # | (3.63 ± 1.14) × 10-6 # | |

| S100P | (1.13 ± 0.23) × 10-3 † | (2.45 ± 1.45) × 10-7 † | (6.72 ± 2.13) × 10-2 † | (4.50 ± 1.75) × 10-7 † | |

| S100P F89A | (2.83 ± 1.25) × 10-3 | (1.43 ± 1.03) × 10-6 | (4.10 ± 0.39) × 10-2 | (2.02 ± 0.95) × 10-6 | |

| GM-CSF | S100A4 | n.d. | |||

| S100A6 | |||||

| S100P | (6.87±0.71) × 10-4 ** | (8.11±2.14) × 10-7 ** | - | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).