Introduction

In recent years, the focus on innovation performance has moved to the center stage of scholarly research on Human Resource Management (HRM) (Lin et al., 2023). Innovation performance is an important indicator that must be paid attention to in building the long-term sustainability of enterprises, especially in the context of VUCA (Complexity, Ambiguity, Uncertainty, Randomness) era, and the current external competition faced by enterprises is increasingly intense.

The rapid iterations of the digital economy and unpredictable technological changes have increased the competitive pressure on enterprises, and how to achieve the transformation and upgrading of enterprises and digital empowerment with the help of innovation has become a key topic of concern in the industry. As the most active economic unit, enterprises, by pooling superior resources, creating an innovation system and improving innovation efficiency, are important measures to build up their competitive advantages and achieve long-term sustainable development.

Based on this, it is of great practical significance to explore the influencing factors of enterprise innovation from a microscopic perspective. At present, many scholars have studied the antecedents influencing the innovation performance of firms from various perspectives such as open search strategies, dedicated human capital (Wood and de Menezes, 2011), and innovation networks (Jackson, Schuler, and Jiang, 2014). So, are there other factors that may have an impact on firm innovation performance?

Most studies have concluded that organizational change is a stressor for employees at work and the effect of change on employees depends on their stress coping strategies (Payne, Trumbach, and Soharu, 2022; Saleem et al., 2022). In fact, organizational change may also motivate employees to work and promote positive and positive behaviors. The rapidly changing environment leads to more frequent and urgent organizational changes, even in time to prepare for them, and employees may first face changes in their job characteristics when meeting organizational changes, which often directly affect employees’ work attitudes and thus have a differential effect on innovative performance. the JD-R model states that when the job generates more work demands, employees tend to feel tired due to higher stress and have a negative effect on work When work resources are increased, employees are not only relieved of work pressure, but also motivated, motivated, and more engaged in their work, which in turn produces positive work outcomes (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, and Schaufeli, 2001). Therefore, changes in work characteristics brought about by organizational change may have negative and positive dual effects on employees’ innovation performance through both work pressure and work engagement paths, respectively, and the investigation of this mechanism is an important guide for enterprises to improve employees’ innovation performance in the context of organizational change.

The success of organizational change is closely related to employees’ attitudes and behaviors. In other words, whether employees actively participate and respond to organizational change largely determines whether the change can be successfully promoted and achieve good results, while the relationship between employees and the organization can largely influence employees’ attitudes and performance in the change. Organizational identity is a kind of cognitive and emotional belonging that employees regard themselves and the organization as a unified body. When employees identify themselves as members of an organization, they will make favorable tendencies toward the organization in terms of resources, behaviors, and emotions, etc. Employees with high organizational identity tend to show a supportive attitude toward the organization or are more willing to maintain consistency with organizational goals in their actions (Ashforth and Mael, 1989). In particular, in the context of organizational change, employees with high levels of organizational identity tend to show positive attitudes toward change and are able to respond positively and actively participate in their actions, stimulating their personal potential and creativity to facilitate the smooth implementation of change and the achievement of organizational goals. Therefore, the differentiated level of organizational identity may play a boundary-binding role in the process of the dual-path influence of organizational change on employees’ innovation performance.

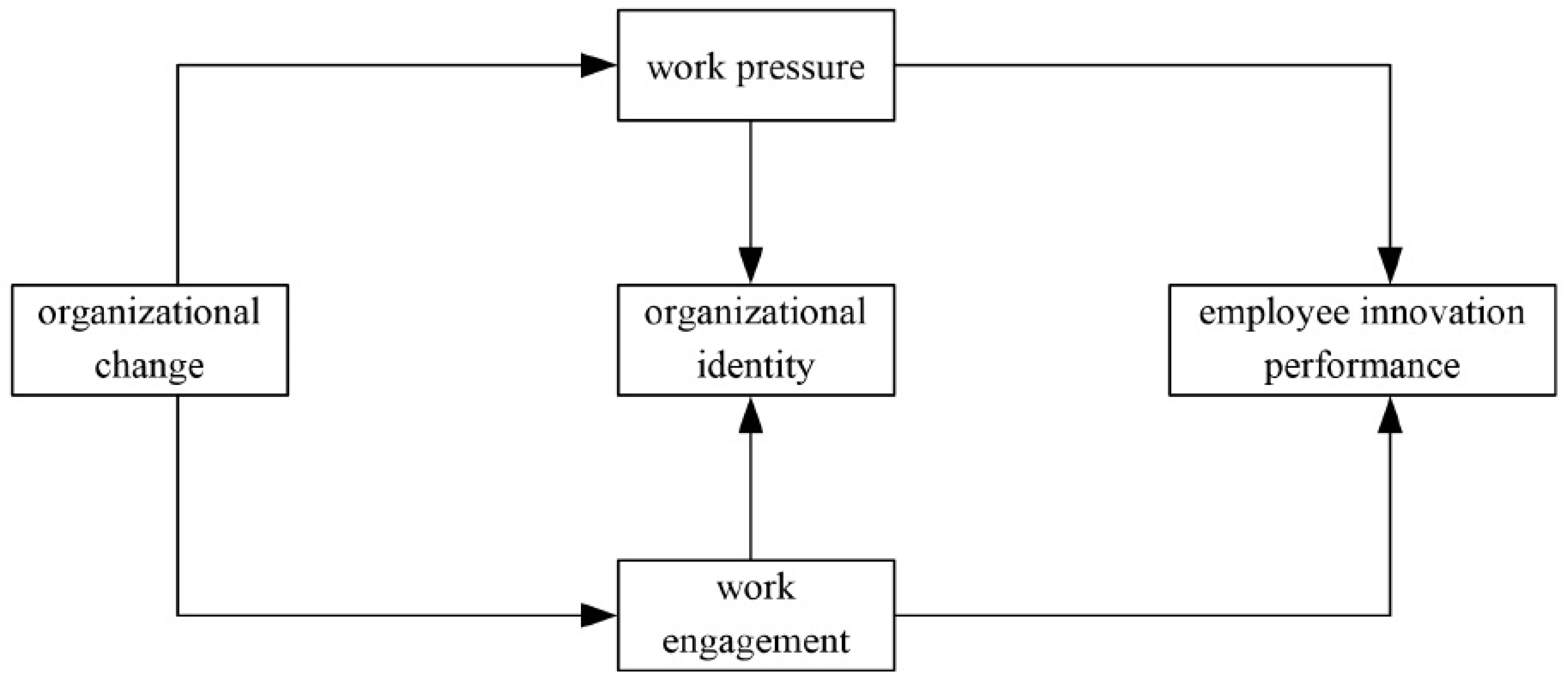

By testing the proposed research model (see

Figure 1) the study contributes to the HR, organizational change, and innovation performance literature in two primary ways. First, explores the mechanism of the influence of organizational change on employees’ innovation performance, which enriches the research on the influence of organizational change on employees’ work outcomes and expands the antecedent research on employees’ innovation performance. The JD-R model has been widely cited and studied by more scholars since its introduction, but the existing literature rarely applies this model theory to organizational change contexts, ignoring the relationship between organizational change and employee performance based on the JD-R model perspective. While past studies have extensively explored employee innovation performance, focusing more on the individual employee and work level, the number of studies on the relationship between organizational change, as a special organizational contextual factor, and employee innovation performance is somewhat stretched. In doing so, it directly responds to calls from researchers to investigate possible organizational factors, i.e., organizational change, which can affect employees’ innovative performance (Becker, Lazaric, Nelson, and Winter, 2005). The second contribution of the study is that it investigates the boundary conditions of the organizational change-innovation performance link. This is critical to decipher whether organizational change can universally increase or reduce innovation performance or whether their impact is dependent on contextual factors. A number of authors have called for research which explores the important variables capable of enhancing or undermining the effectiveness of organizational change (Bouckenooghe, Schwarz, Kanar, and Sanders, 2021) and in this regard we look at a critical albeit unexplored factor which occurs inside the domain of work i.e. organizational identity.

In the following sections, we discuss the links in the proposed model and the theoretical underpinnings for the proposed hypotheses. Then the paper will discuss the employed methodology before discussing the results and implications for both theory and practice.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Job Demands-Resources Theory

The Job Demand-Resource (JD-R model) is a theoretical achievement formed by Demerouti et al by drawing on the ideas of resource conservation theory, job demand-control theory (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, and Schaufeli, 2001), and give-and-take imbalance. Once the model was proposed, it received wide attention from the fields of management and psychology (Becker, Lazaric, Nelson, and Winter, 2005; Zhu, Wanberg, Harrison, and Diehn, 2016), and scholars have conducted rich studies based on the JD-R model, which have enriched the content of the model and helped in its continuous improvement and revision. At present, the JD-R model has developed into a more mature and perfect JD-R theory (Jiang, Ning, Liu, Zhang, and Liu, 2022).

According to the JD-R model, any occupation possesses unique factors that affect employee health and work status, all of which can be attributed to job demands and job resources, which together constitute job characteristics. Among them, work demands are those factors in work that involve physical, psychological, social or organizational aspects that require continuous physical and mental effort, which are related to physical and mental exertion, such as work-family conflict, role stress, work load, etc. Work resources are the resource factors that can provide workers with physical, mental, social or organizational support and assistance, such as autonomy, supervisor support, work participation, performance feedback, etc. These resources help motivate workers to achieve their goals, reduce the physical and psychological exertion generated by work demands, and promote personal growth, learning and development.

The JD-R model proposes a dual process of positive and negative effects of job characteristics on employees’ job outcomes, which provides the theoretical basis for this paper. In the process of organizational change, employees usually face role change, job content or way adjustment, etc., which leads to changes in job requirements and job resources. Continuous or high level of change requirements can damage employees’ physical and mental health and lead to resource depletion, causing psychological stress and job burnout, which negatively affect their innovation performance. However, the abundant supply of change resources can alleviate the negative effect of change requirements, motivate employees to work, motivate employees to actively participate in their work, and thus improve their innovation performance. Therefore, in the process of organizational change, employees may perceive changes in job requirements and job resources and produce negative and positive dual psychological and behavioral outcomes, respectively, which have differential on their individual innovation performance.

Organizational Change, Work Pressure and Employee Innovation Performance

Organizational Change and Work Pressure

Organizational change is a process of strategy, structure, technology, human resources and other factors change carried out by an organization to better achieve its goals. Although organizational change takes the improvement of business operation as the starting point, there is significant evidence that organizational change will lead to work pressure among employees (Hetland, Bakker, Espevik, and Olsen, 2022). JD-R model points out that the work requirements of employees at work will lead to the loss of individual health, continuous or high level of work requirements may consume employee resources, and then consume mental energy and cause stress

process (Hetty Van Emmerik, Bakker, and Euwema, 2009). As a result, employees may feel higher levels of work pressure in the face of increased job demands.

Research shows that organizational change will lead to increased job requirements of different degrees (García-Morales, Jiménez-Barrionuevo, and Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, 2012). The process of organizational change is often accompanied by organizational structure adjustment, system adjustment, technology upgrade, personnel adjustment and other actions. In 2015, China introduced its Made in China 2025 strategy to upgrade technology comprehensively. Thus this reform led to dramatic increase in the organization affairs (Dhar et al., 2022). In order to ensure the smooth implementation of the change, the organization usually promulgates new organizational policies and systems and establishes new rigorous working procedures. In this process, Organizational politics and red tape in organizations may consume more energy and resources of employees and increase their sense of stress (Sharma et al., 2021). Furthermore, in order to adapt to the changes generated by the reform, employees need to understand new organizational policies, learn new routine procedures and skills (Rafferty and Griffin, 2006). These work requirements will increase the workload and cognitive impairment of employees, leading to work pressure. In addition, employees may encounter the change of job positions and the change of superior leaders in the process of reform, and need to establish working relationships with new colleagues, which undoubtedly increases their requirements in interpersonal communication, and even leads to role conflicts and ambiguities, and interpersonal conflicts. In addition, many studies have pointed out that uncertainty is also the main source of pressure of organizational change on employees, and employees will try to search for information about change-related events to understand the content of the change to reduce uncertainty, thus generating work pressure (Weber, Büttgen, and Bartsch, 2022). Organizational change is often accompanied by the implementation of new technologies, organizational structure adjustment, relocation, mergers and acquisitions, and personnel reform, among which the frequency and intensity of change may also increase the working pressure of employees and undermine their well-being (Cannavacciuolo, Capaldo, and Ponsiglione, 2022).

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the hypothesis that

H1a: Organizational change positively affects work pressure.

Work Pressure and Employee Innovation Performance

Once work pressure is generated, employees’ work emotions, attitudes and behaviors are bound to be affected. Most scholars believe that the effects of work pressure on employees include both positive and negative aspects, which are related to the dual attributes of challenging and hindering stress. Research on the effects of the double-edged sword of work pressure from the perspective of the dual attributes mainly reflects the positive results of challenging stress and the negative results of hindering stress. Organizational change usually implies workload, job uncertainty, organizational politics, and cumbersome work procedures, among which hindering stress is more significant than challenging stress, so scholars prefer hindering stress in the classification of stressors (Shin, Woodwark, Konrad, and Jung, 2022; Wu, Chen, and Wang, 2023). Obstructive stress refers to stresses that employees find difficult or impossible to cope with, which are difficult for employees to resolve through their own efforts and therefore prevent them from self-improvement and goal achievement (Rissel, Petrunoff, Wen, and Crane, 2014). Although the challenging pressures of organizational change can motivate employees to work, challenge themselves, and increase their work engagement, the accompanying hindering pressures have a more significant impact on employees. Obstructive pressures do not have potential benefits and not only hinder employees’ work process, but also consume their resources (Jiang, Ning, Liu, Zhang, and Liu, 2022), so employees do not invest more time and energy in searching for new ways to solve problems, but rather “settle” for the existing solutions. Once motivation for innovation is weakened, innovation performance is naturally lower (Ek Styvén, Näppä, Mariani, and Nataraajan, 2022). A number of empirical studies have confirmed these inferences. Researchers based on a cognitive resource theory perspective, argued that work pressure reduces the cognitive resources needed to generate innovative thinking and leads to a greater tendency to habitual patterns of thinking and action, which undermines creativity (Dayton and Sala, 2001). Other studies have confirmed the idea that work pressure inhibits individual innovation (He, Wu, Zhao, and Yang, 2019).

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the hypothesis that

H1b: Work pressure negatively affects employees’ innovation performance.

Organizational Change, Work Engagement and Employee Innovation Performance

Organizational Change and Work Engagement

The JD-R model states that work resources motivate employees, enhance work engagement, and help employees achieve superior performance (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, and Schaufeli, 2001). Change researchers have confirmed that information about change, participation in change, supervisor support for change, decision-making autonomy, and career development opportunities are positively associated with positive employee feedback on organizational change, and that an increase in work resources related to organizational change facilitates increased employee change engagement (Kashif, Zarkada, and Thurasamy, 2017). Organizational change is a series of activities in which orders are given from the top down and feedback is given from the bottom up, and in order to promote successful implementation of change, leaders at all levels often provide supportive resources to employees, including a clear purpose and vision for change, clear communication about the change message, and positive encouragement and assistance with the change (Rass, Treur, Kucharska, and Wiewiora, 2023). Employees who feel supported by their superiors are more motivated to commit to their work and show full energy and stronger dedication. In addition, change involvement is an important work resource in organizational change. It has been shown that employees who have the opportunity to participate in the design and implementation of change are more willing to actively support the change and are more engaged in the change process (Brammer, He, and Mellahi, 2015). Researchers showed, based on the JD-R model, that a work environment that provides employees with job control during organizational change also enhances employees’ willingness to dedicate their personal capabilities to their work, increases employee work commitment, and induce employees to evaluate organizational change favorably (Omer and Roberts, 2022).

In addition to this, other scholars have focused on procedural justice as a working resource in organizational change (Proost, Verboon, and van Ruysseveldt, 2015). Organizational change is a complex process in which organizations select change agents to gather relevant information about employees’ concerns and create new rules and mechanisms (i.e., procedural justice) to support the change (Jiang and Chen, 2021). A high level of procedural justice means that employees have more opportunities to express their opinions and can use such work resources to protect themselves from the effects of change (Guay and Choi, 2015). Particularly in the context of organizational change, action initiatives in which companies seek to listen to employees and provide relevant information can signal organizational procedural fairness to employees, who perceive an increase in work resources and thus have a positive attitude toward organizational change. When employees have more resources, they are also more willing to adjust their behavior to accommodate change and enhance their work engagement during change (Proost, Verboon, and van Ruysseveldt, 2015).

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the hypothesis that

H2a: Organizational change positively affects work engagement.

Work Engagement and Employee Innovation Performance

The relationship between job attitudes and performance has been the focus of academic inquiry in existing research and practice, where work engagement is considered a stronger predictor of performance than other attitudinal constructs such as job satisfaction, job commitment, and organizational commitment (Rich, Lepine, and Crawford, 2010). Work engagement is the physical, emotional, and cognitive involvement of employees into their organizational roles, expressed as energy, dedication, and focus. Cognitive engagement has been shown to be the mental energy required for innovative behavior, and in the process of generating ideas, employees invest additional cognitive effort to support better and different systems and processes through cognitive flexibility (Yao et al., 2022). In this process, employees expand their cognitive and perceptual scope by revisiting their existing knowledge structures and may experiment with nontraditional adaptations and combinations of ideas to mobilize innovative behaviors (Fredrickson, Mancuso, Branigan, and Tugade, 2000). Knowledge dissemination is a vital factor in economic development (Dhar et al., 2023). Research showed that according to the cognitive-emotional personality system theory, employees are able to complete their work with a sense of responsibility and pride when they are highly engaged in their work, are courageous and persistent and this state of high cognitive activity and arousal can promote their innovative behavior (Banks, Woznyj, and Mansfield, 2021).

In addition to cognitive engagement, work engagement includes energetic and dedication, and new employees with higher levels of work engagement are able to enter the workplace more efficiently and show higher levels of engagement and enthusiasm in their work, which in turn leads to more innovative behaviors (Lee, Sok, and Mao, 2022). From an emotional perspective, employees with high levels of work engagement not only establish a strong emotional connection with their work, but also possess greater confidence to perform the job requirements (Goering, Shimazu, Zhou, Wada, and Sakai, 2017), and even when they encounter various difficulties at work, they are able to proactively find new ways to change the status quo. In this process, novel and practical ideas may thus be elaborated, and employees show greater creativity and higher levels of innovative performance at work (Rogiest, Segers, and van Witteloostuijn, 2015). From a physiological involvement perspective, the creative process involvement theory states that the innovation realization process often includes three stages: problem identification, information search, and idea generation, and when employees invest a lot of time and energy in their work, they are highly likely to identify problems and gather information more effectively in their work practices in order to come up with more reliable solutions, thus promoting personal innovation performance (Kim, Hon, and Lee, 2010).

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the hypothesis that

H2b: Work engagement positively affects employee innovation performance.

The Mediating Role of Work Engagement

The process of organizational change is accompanied by the realignment and reallocation of employee work resources, and supervisor support, change participation, and change autonomy can motivate employees to respond positively to change. It has been confirmed that superior support, support from colleagues, family and friends, and job rewards in work resources significantly and positively predict work engagement (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, and Schaufeli, 2001). In addition, organizational change usually involves changes in technology, management models, or business process re-engineering, and training and development related to change is a practical activity that organizations must consider and implement. By participating in training, employees have the opportunity to gain access to enhance their personal skills development, which has a positive effect on promoting their work engagement during change (Albrecht, Connaughton, Foster, Furlong, and Yeow, 2020; Jiang, Ning, Liu, Zhang, and Liu, 2022). In addition, new policies and systems are often enacted during organizational change, and employees’ performance under the new rules is of high concern to organizational leaders, who often support and encourage their work engagement and active response during change periods and give timely performance feedback on their performance. Developmental feedback from superiors, as an important work resource for employees, can stimulate motivation and engagement motivation and lead to more passionate commitment to work (Zhang, Zhang, Zheng, Cheng, and Rahmadani, 2019).

When employees are at a high level of work engagement, they are willing to work hard for their jobs and do not easily get tired, and they are able to persevere even in the face of work difficulties, showing a positive emotional state at work (Eldor and Vigoda-Gadot, 2017). In such a context, when employees are engaged in their work and experience positive emotions, their intellectual and psychological resources are expanded, thus promoting them to actively explore, discover and develop original ideas and try to put innovative ideas into practice (Kim, Han, and Park, 2019). Compared to repressed emotions, active and positive emotional experiences facilitate employees to generate greater creative fluency, increase the level of divergent thinking, and therefore generate higher creativity and achieve higher levels of innovative performance (Robb et al., 2022).

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the hypothesis that

H2c: Organizational change positively affects employee innovation performance through work engagement.

The Moderating Role of Organizational Identity

Organizational identity is the cognitive and emotional belonging of employees to the organization based on their individual organizational membership identification, and this identity can motivate employees to think about and guide their personal work behavior from the perspective of organizational interests. As mentioned above, organizational change creates a work environment full of uncertainty and insecurity, and employees may feel more work demands and work pressure in the turbulent environment. At the same time, organizational change is accompanied by an increase in work resources, which promotes employees’ work engagement. Organizational identity, as a special self-construal of the employee-organization relationship, is more than a simple exchange between employees and the organization; it can have a direct impact on employees’ work attitudes and behavioral choices. Employees with a high level of organizational identity tend to recognize and support organizational decisions, are willing to expand their perceptions of their work roles, and make personal decisions based on the principle of alignment with organizational goals even in the face of uncertainty (Ashill, Abuelsamen, Gibbs, and Semaan, 2022); this trust and support for the organization can weaken employees’ work pressure due to organizational change and strengthen the positive impact of organizational change on work engagement. Organizational identity is spontaneous, and employees’ strong spontaneous identification with the organization helps employees to actively cope with stressors at work, and even if some work is unpleasant and depletes resources, employees can still persist and endure, thus weakening the positive predictive effect of organizational change on work pressure. On the other hand, employees’ sense of belonging to the organization, pride, and other emotional attachments can lead to positive attitudes toward change (Ashforth and Mael, 1989), especially when employees identify themselves as part of the organization, they will tend to take actions that are beneficial to the organization’s development, actively engage in their work and expect to dedicate themselves to achieving organizational goals, thus enhancing the positive effect of organizational change on work engagement. On the contrary, if organizational identity is at a low level and employees’ relationship with the organization lacks cognitive and emotional foundation, a series of change initiatives brought by organizational change may intensify employees’ dissatisfaction with the organization, and employees need to consume more resources to cope with the change requirements and generate more work pressure. At the same time, according to resource conservation theory, employees may pay less to their work and reduce their personal work commitment in order to protect their resources.

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the hypothesis that:

H3a: Organizational identity negatively moderates the effect of organizational change on work pressure.

H3b: Organizational identity positively moderates the effect of organizational change on work engagement.

Organizational identity, as a strong sense of identification and belonging of organizational members to the organization, provides an emotional basis for employees’ innovative behavior, and therefore, organizational identity can play an influential role in the relationship between organizational change and innovative performance. In a study by Griffin et al (Griffin, Neal, and Parker, 2007), it was found that organizational identity is a necessary condition for employees to achieve high levels of performance in work situations with high uncertainty. Based on social identity theory, high organizational identity will bring individuals closer to the organization and make employees’ personal goals converge with the organizational goals of the company, and even in the face of organizational change, employees can match their perceptions of the organization with their own best under this psychological perception to promote the survival and development of the company through pioneering and innovative work attitudes and continuous innovative work behaviors (Xu, Graves, Shan, and Yang, 2022). A study (Avey, Avolio, and Luthans, 2011) pointed out that employees who have a strong sense of identification with the organization will stand firmly with the organization even when they are in adversity or encounter more difficulties at work, out of trust and belonging to the organization. This resilience can help employees cope positively with work pressure, alleviate burnout under high pressure, and weaken the negative impact of organizational change on innovation performance through work pressure.

Organizational identity promotes the formation of an implicit psychological contract between employees and the organization, and employees with strong organizational identity will develop real dependence and belonging, and thus spontaneously make efforts to maintain the dignity of the organization, which provides strong motivation and persistence for individual innovative behavior (Brammer, He, and Mellahi, 2015), (Brammer, He, and Mellahi, 2015; Glavas and Godwin, 2013).

In the face of a series of changes in organizational change, employees with high organizational identity can show stronger cognitive understanding and inclusiveness, and are willing to put in physical and mental efforts to help the organization achieve its goals, which is reflected in their work as full of energy, energetic, and proactive in stimulating personal innovation potential and creativity to improve work efficiency to better adapt to the change. It has been confirmed that employees tend to show greater creativity when they are in a better organizational climate and have a higher level of organizational identification (Lin et al., 2023; Lin, Ma, Zhang, Li, and Jiang, 2018). Conversely, employees who lack the experience of organizational identity find it difficult to align their personal goals with organizational goals in organizational change, and when faced with stress, they often fail to feel the significance of overcoming challenges and tend to develop pessimistic and negative emotions, which in turn amplify the negative transmission effects of work pressure and hinder the positive feedback effect of work engagement, preventing them from achieving the desired innovative performance.

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the hypothesis that

H4a: Organizational identity moderates the mediating role of work pressure between organizational change and employee innovation performance.

H4b: Organizational identity moderates the mediating role of work engagement between organizational change and employee innovation performance.

The research model of this paper is shown in Figure 1.

Method

Sample

The study applied a survey method based on a questionnaire to collect data. Data were collected from companies located in the eastern region of China that are in the midst of change. Access to the participants was gained through professional and personal contacts of the author(s). A total of five companies were examined for this study in order to select participants. The link to the questionnaire was distributed to individual employees by contacting the department heads of the companies, introducing the purpose of the study, and seeking their consent; for those who were not comfortable filling out the questionnaire online, a paper questionnaire was distributed to the survey participants. The survey participants were coded before filling in the answers, and the questionnaires were matched through the codes after they were returned. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were assured of the anonymity of their responses. In addition, we told the participants that all identifying information would be removed to preserve their anonymity. To reduce the potential common method biases (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff, 2003), we conducted surveys in three different phases separated by 3 weeks. If the time lag is too long, it may mask existing relationships; by contrast, if the lag is too short, memory effects may inflate the relation artificially between variables (Babalola, Stouten, Camps, and Euwema, 2019). In the first stage, we asked employees to report organizational change and demographic characteristics, 350 questionnaires were distributed and 328 were returned, for a 93.71% return rate; three weeks later, in the second stage, employees were asked to report work pressure, work engagement, organizational identity, and demographic characteristics, 328 questionnaires were distributed and 309 were returned, for a 94.20% return rate; three weeks later, in the third stage, employees were asked to employees to report innovation performance and demographic characteristics, 309 questionnaires were distributed and 301 were returned, for a 97.41% return rate. To increase the seriousness of completing the answers, a fee of $40 was paid to the participant upon completion each time. After all stages of data collection were completed, all online and offline questionnaire data were integrated and aggregated, and the three phases of questionnaire matching were conducted through the code. After eliminating invalid questionnaires with missing or mismatched questionnaire code numbers, questionnaires with questionable answers, and questionnaires where the subjects’ work had not been experienced or affected by organizational change, a total of 289 valid questionnaires were obtained, with an efficiency rate of 96.01%.

Measures

All scales were measured on a seven-point Likert-scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Scores were created by averaging the relevant items. All the scales used are based on existing measures that have been shown to have sound psychometric properties.

Organizational change was measured with (Bartunek and Woodman, 2015) 15-item scale.

Respondents indicated how often they experience each state using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). There are 15 questions on the scale, and representative questions include “This change will have an important impact on my future in the company”, “This changehas changed the way I work”, and “I can participate in the change process”. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.958.

Work pressure was measured using the (Boswell, Olson-Buchanan, and LePine, 2004) scale. There are 5 questions on the scale, and representative questions include “I have multiple projects or tasks at the same time and have a large workload or task” and “I have a large amount of work and tasks to complete within a set time frame”. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.918. Work engagement was measured using (Schaufeli, Bakker, and Salanova, 2006) scale. Seven items were selected to measure the variables, including “I feel energetic and dynamic when I work,” “When I work, I forget everything around me,” and “At work, I always persevere even when things are not going well,” etc. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.972. Organizational identity was measured using (Miller, Allen, Casey, and Johnson, 2000) three-dimensional scale. There are 6 questions on the scale, and representative questions include “I care deeply about the future of my company,” “I find that my values are consistent with the organization’s values,” and “I would like to devote my future to my company. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.917.

Employee innovation performance was measured using (Wang, Chen, and Fang, 2018) scale. There are 7 questions on the scale, and representative questions include “I am open to coming up with new ideas in order to improve the current situation,” “I am open to turning innovative ideas at work into practical applications,” and “I often look for new ways of working, tools, and ways of doing things to improve my work.” The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.970. Several variables were controlled. Following previous studies (Wang, Cui, Cai, and Ren, 2022), gender (0 = female, 1 = male), employee age (1 ≤ 25 years to 4 = 46 years and over), education (1 = high school degree or less to 4 = master’s degree or above), job position (0 = general employees, 4 = senior management), tenure (1 ≤ 1 year to 5 = over 10 years) and company size (1 ≤100, to 4 =over 1000) are included as control variables in the current study.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Correlations among all study variables are presented in

Table 1. As shown in

Table 1, the control variables were correlated with some of the main variables, respectively, indicating that the choice of control variables was meaningful. Organizational change was positively correlated with work pressure (r=0.327, p<0.001) and work engagement (r=0.224, p<0.001), respectively, and similarly, employee innovation performance was negatively correlated with work pressure and positively correlated with work engagement, respectively. Organizational change was not significantly related to employee innovation performance, and organizational identity was negatively related to work pressure (r= -0.363, p<0.001) and significantly positively related to organizational change (r=0.084, p<0.05), work engagement (r=0.653, p<0.001), and employee innovation performance (r= 0.396, p<0.001). The results of the correlation analysis indicated that the hypothesized relationships among organizational change, work pressure, work engagement, employee innovation performance, and organizational identity were initially verified. In addition, the correlation coefficients between the core variables were all less than 0.7, reflecting the absence of serious multicollinearity among the variables.

The Measurement Model

We first examined the convergent and divergent validity of our measures. Specifically, a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) and model comparisons were conducted. CFA analyses found that the five-factor (i.e., organizational change, work engagement, work pressure, employee innovation performance, organization identity) measurement model fit the data well: χ2/df=2.373, p<0.01, RMSEA=0.069, SRMR=0.058, TLI=0.919, CFI=0.925, (

Table 2). All factor loading for items were significant (ps<0.01). Results of model comparisons further demonstrated that the hypothesized five-factor measurement model had a significant better fit to the data than any of the alternative four-factor models (i.e., combining any two of the five factors). Such findings provided evidence of construct distinctiveness.

Common Method Variance

Although we collect three-phase data, all five variables are from the same source. We use multiple methods, namely Harman’s single-factor test and controlling for the ULMC (Unmeasured Latent Method Construct) methods factor to test for the presence of common method variance (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff, 2003). As shown in

Table 2, a one-factor model does not fit well (χ2/df =8.678,

p>0.05; CFI=0.571, TLI=0.545, SRMR=0.139 and RMSEA=0.163), whereas the five-factor model fits satisfactorily (χ2/df =2.373,

p<0.01, TLI = 0.919, CFI=0.925, SRMR=0.058 and RMSEA = 0.069). The

χ2 comparison shows that the one-factor model is significantly worse than the five-factor model. Referring to the treatment of (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff, 2003), we also control for the effects of the ULMC methods factor. We construct one latent variable,

CMV (common method variance), by loading all observed indicators of the five theoretical variables. Hence, we develop a six-factor model that includes five theoretical variables and

CMV. The results reveal that the six-factor model (χ2/df= 2.372,

p<0.01, TLI=0.919, CFI=0.925, SRMR=0.060 and RMSEA =0.069) does not substantially improve the goodness of fit of the six-factor model (

Table 2). Based on the above judgment, the effect of common method variance was not significant in this study.

One-factor Model all variables combined;

Two-factor work engagement, work pressure, employee innovation performance, organizational identity combined;

Three-factor Model work pressure, employee innovation performance, organizational identity combined;

Four-factor Model employee innovation performance, organizational identity combined;

Five-factor Model hypothesized model;

Six-factor Model five theoretical constructs with the latent common methods variance factor.

Hypothesis Testing

Hierarchical regression analysis of variables was performed using SPSS 22.0 software, and Bootstrap tests for mediating and moderating effects were performed using the Process program, respectively.

Main Effect Test

Regression analysis was conducted on work pressure, work engagement and employee innovation performance to initially test the first half path and second half path effects of the mediating effects of work pressure and work engagement, and then Bootstrap test was applied to the dual mediating effects of juxtaposition using the Process procedure to further test the overall mediating effects and to improve robustness. The results of the regression analysis between organizational change, work pressure, and employee innovation performance are shown in

Table 3. By comparing model 1 and model 2, organizational change has a significant positive effect on work pressure (b= 0.322, p< 0.001) based on the control variables, thus hypothesis H1a is supported. Comparing model 4 and model 5, the effect of organizational change on employee innovation performance changed from insignificant to significant after adding mediating variables, and work pressure showed a significant negative predictive effect on employee innovation performance (b= -0.535, p< 0.001),

whereby hypothesis H1b was supported.

The results of the regression analysis between organizational change, work engagement, and employee innovation performance are shown in

Table 4. By comparing Model 1 and Model 2 in

Table 5, on the basis of the control variables, organizational change has a significant positive effect on work engagement (b= 0.216, p< 0.001), i.e., organizational change positively promotes work engagement, thus hypothesis H2a is verified. On the basis of model 4, with the addition of mediating variables, the results showed that the regression coefficient of organizational change on employee innovation performance increased but was not significant, and work engagement had a significant positive predictive effect on employee innovation performance (b= 0.545, p< 0.001), thus hypothesis H2b was verified.

Moderating Effect Test

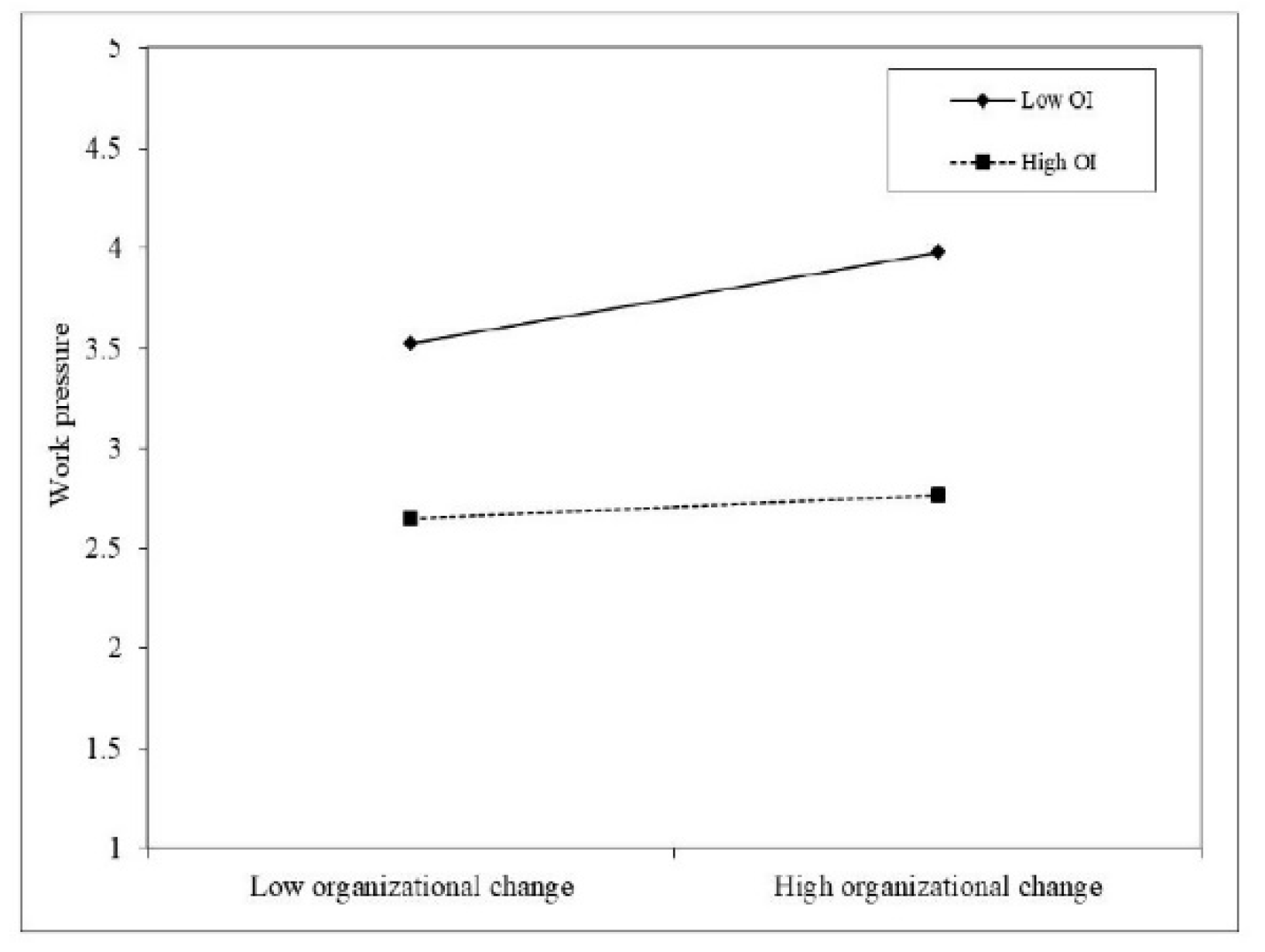

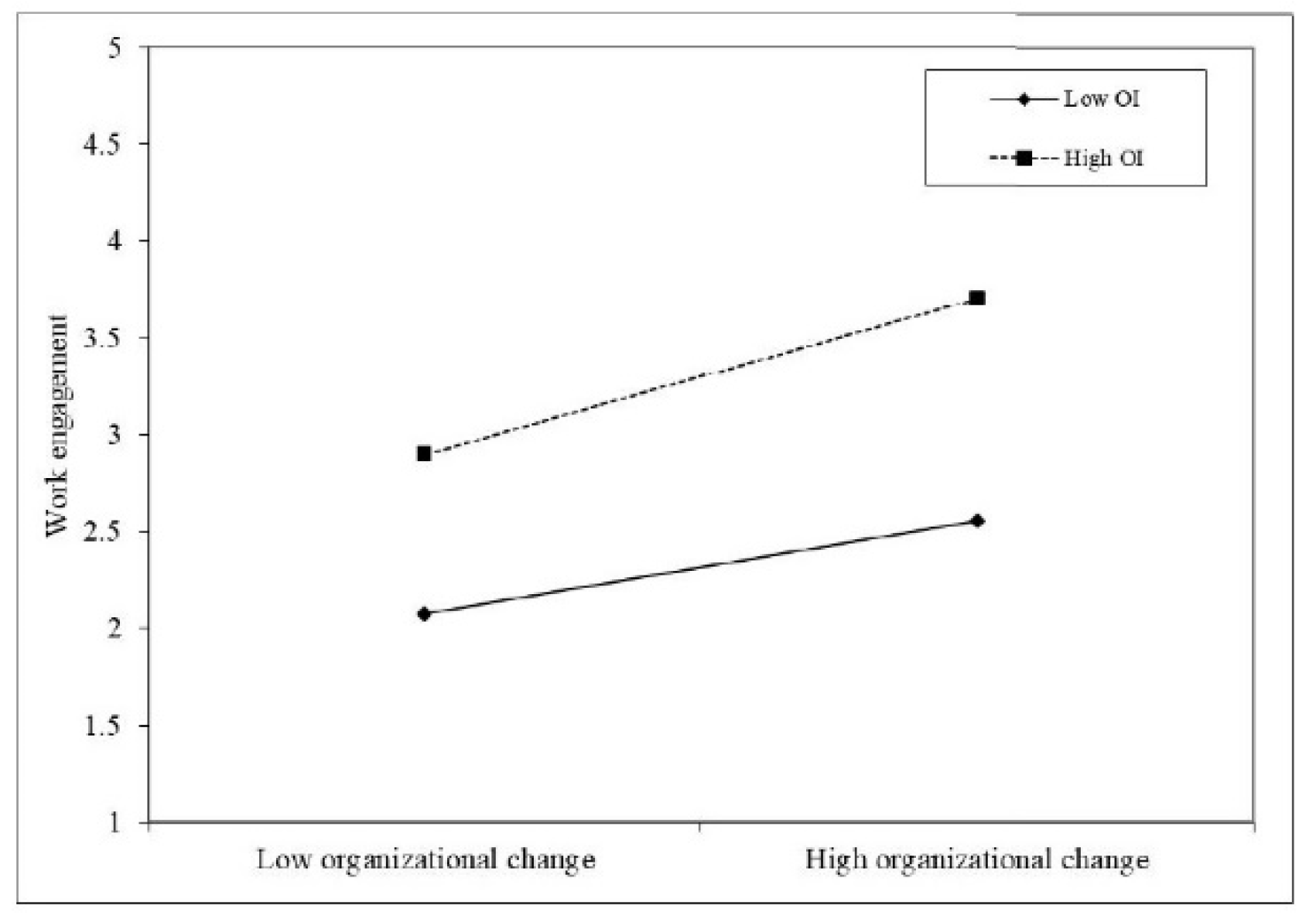

Before conducting the moderating model runs, both the independent and moderating variables were centered to reduce the multidisciplinary of the variables. In the work pressure regression model, model 2 showed significant interaction term regression coefficients after adding the independent variables, moderating variables, and the product of the two interaction terms based on model 1, indicating the moderating role of organizational identity in the process of organizational change affecting work pressure (see

Table 6). Similarly, in the work engagement model, the regression coefficient of the interaction term between organizational change and organizational identity is significant in model 4, indicating that organizational identity moderates the effect of organizational change on work engagement.

Based on the model of the dual mediating path effect of organizational change on employee innovation performance, adding the moderating variable organizational identity, the overall mediating-regulating effect path can be obtained as shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. Under the moderating effect, organizational change significantly and positively predicts work pressure and work engagement, but organizational identity negatively moderates the effect of organizational change on work pressure and positively moderates the effect of organizational change on work engagement, respectively.

To further explain the moderating effect of organizational identity, simple slope estimation was conducted in this study (see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). As shown in

Figure 2, the negative effect of organizational change on work pressure is stronger at low organizational identity compared to high organizational identity level, so organizational identity can somewhat weaken the negative predictive effect of organizational change on work pressure.

Figure 3 shows that the positive effect of organizational change on work engagement is stronger at high organizational identity levels. Thus, hypotheses H3a and H3b are supported.

Discussion

Based on the JD-R model, this study investigates the “double-edged sword” effect of organizational change on employees’ innovation performance, and considers the boundary role of employee-organization relationship in the above influence process. First, organizational change negatively affects employee innovation performance through the mediating role of work pressure. Empirical studies show that organizational change positively affects work pressure, while work pressure negatively affects employee innovation performance. According to JD-R model theory, any job characteristic can be divided into job demands and job resources, in which job demands can consume employees physically and mentally and thus lead to health depletion process and eventually lead to negative job outcomes. The increased work demands due to change, such as workload, role conflict, and organizational politics, tend to consume more energy and time for employees to complete their old or new work tasks, thus increasing their work pressure. In addition, a series of new policies and events in the change may require employees to recognizance and re-adapt, and the uncertainty brought by the change makes them psychologically worried and apprehensive, thus creating a sense of insecurity and increasing work pressure. Employees under high work pressure tend to focus more on dealing with negative emotions and stress to seek “resource protection” during the change phase, so it is difficult to devote time to improving work effectiveness and personal innovation, which ultimately leads to low innovation performance. Second, organizational change positively affects employee innovation performance through the mediating role of work engagement. The empirical results show that organizational change positively affects work engagement, and work engagement positively affects employee innovation performance; therefore, work engagement positively mediates the relationship between organizational change and employee innovation performance. In the process of organizational change, procedural fairness, support from superiors, change participation and feedback are all work resources that are added to employees’ work. These work resources create a favorable change climate, help employees better understand and support change, and allow them to perceive higher work value and stronger work meaning, so that they are more engaged in their work and stimulate their personal creativity to perform better in innovation at work performance. Finally, organizational identity negatively moderates the negative effect of organizational change on work pressure and positively moderates the positive effect of organizational change on work engagement, while moderating the mediating role of work pressure and work engagement between organizational change and employee innovation performance.

The results of the study show that in the mediated-regulated model, organizational identity has a significant moderating role in the process of organizational change affecting work pressure and work engagement, and low organizational identity amplifies the negative effect of organizational change on work pressure, while high organizational identity enhances the positive effect of organizational change on work engagement. The moderating effect of organizational identity on the two mediating variables was also significant in the test of the mediating model with moderation. According to social identity theory, individuals with identity are usually consistent with the society or group to which they belong in many aspects of behavior and perceptions. Organizational identity is an extension of social identity in the organizational environment, and employees with a high level of organizational identity tend to rely on the organization, trust the organization, align their personal goals and interests with those of the organization, and are willing to do their best for the organization. Therefore, in the face of the “test” of organizational change, members with high organizational identity can also support and cooperate with organizational decisions, actively participate in the practice of change, become more involved in their work, and actively mobilize their personal initiative, stimulate their creativity, and better promote the development of change.

Employees with low organizational identity, on the other hand, do not have strong emotional ties with the organization, and are more inclined to respond negatively when they encounter negative effects such as work requirements brought about by change, lack trust in the organization, and are more likely to focus on the potential risks of change, thus generating negative emotions and feeling greater pressure. Out of the protection of their own resources, employees under high pressure are more inclined to try to maintain the timely completion of current work tasks, rather than spending more energy and time to come up with new work ideas, create new work methods, etc., thus showing lower innovative performance.

Theoretical Implications

First, based on the JD-R model theory, the “double-edged sword” effect of organizational change on employees’ innovation performance is confirmed at the individual subjective level. Since the emergence of organizational change, experts and scholars have been focusing on the impact of this context on employees’ work. Given the influence and importance of employees’ attitudes on the outcome of change, more studies have focused on employees’ attitudes and behaviors toward change, but less on the impact of organizational change on employees’ work outcomes in normal work situations. Innovation has always been the main theme of corporate development, and employee innovation performance to some extent reflects organizational vitality and innovation base. Existing studies have investigated the antecedent variables of employee innovation performance in terms of individual factors, job factors, and factors in regular organizational contexts, while less attention has been paid to the current increasingly frequent organizational change contexts. The only relevant literature, too, has derived the effects of organizational change on employee innovation in terms of positive or negative aspects, respectively, while ignoring attempts to explore both positive and negative opposing effects based on an integrative perspective. From the perspective of the JD-R model, this study argues for the dual mediating role of work pressure and work engagement between organizational change and employee innovation performance, taking the changes in job requirements and job resources due to organizational change as triggers, respectively, and provides empirical evidence for the simultaneous positive and negative effects of organizational change on employee innovation performance.

Second, embedding the JD-R model in an organizational change context expands the scope of application of the JD-R model and enriches the research on the results of the JD-R model. However, the number of studies that have embedded the model in a particular organizational context is very small. In fact, the JD-R model provides a very good perspective and theoretical support in exploring the topic of organizational change affecting employees’ innovative performance. These changes have negative and positive effects through the dual path theory of the JD-R model, which explains the “double-edged sword” effect of organizational change on employees’ innovation performance. In addition, job happiness and job performance are the variables that have been widely focused on in the JD-R model’s work outcome studies, while innovation as an outcome variable is relatively uncommon in JD-R-related studies.

Finally, based on social identity theory, the boundary role of organizational identity in the dual mediating mechanism of organizational change on employee innovation performance was explored and confirmed. It was found that organizational change can produce very different results on employee innovation performance through different mediating mechanisms, and this process is also moderated by organizational identity. The higher the degree of employees’ organizational identification, the more they can show positive support for organizational decisions and actions, and the more they are willing to put in more efforts and attempt to help achieve organizational goals. Therefore, when facing organizational change events with uncertainty, organizational identification may directly influence employees’ change responses and behavioral choices. To a certain extent, the above discussion reveals the important role of employee-organization relationship in the process of organizational change affecting employees’ work outcomes that cannot be ignored, and also expands the application of social identity theory in specific organizational development contexts and enriches the content of organizational identity theory.

Practical Implications

First, pay attention to the work requirements and resource changes brought about by organizational change. “Organizational change is a series of innovation from top to bottom, and the successful implementation of this “big move” is actually inseparable from the active participation and support of every member of the organization. JD-R model theory provides a novel perspective to help managers effectively guide employees to actively participate in the change process. The changes in employees’ work characteristics should be categorized and managed to balance the incremental changes in employees’ work requirements and work resources. On the one hand, leaders of each department should strengthen effective communication with employees, always synchronize the systems and policies in the change, increase the training related to organizational change, clarify the new organizational structure and the specific job responsibilities and goals of employees in the change, reduce employees’ perception of job requirements, and relieve employees’ work pressure. On the other hand, management should strengthen the work resources in the change, establish open and transparent communication channels between top and bottom, maintain procedural justice in the change, clearly communicate to employees that they support their participation in organizational change and their personal efforts for the change, and encourage and give positive feedback to employees’ positive change performance in a timely manner to enhance employees’ sense of work meaning and increase their work commitment.

Second, pay attention to the dual-path impact of organizational change on employees’ innovation performance. Companies have been sparing no effort to stimulate employees’ innovation potential, such as improving leadership style and creating a good innovation atmosphere, to enhance employee innovation and thus improve the overall innovation performance of the organization. In fact, in addition to the targeted improvement of innovation management methods and tools, special organizational situations may also bring “unexpected benefits”. Although organizational change is primarily designed to adapt to changes in the internal and external environment, improve organizational efficiency, and better achieve organizational goals, not to improve employee innovation, organizational change itself is a collection of new things and events that provide a “breeding ground” for employee innovation. This study has confirmed that organizational change may hinder employee innovation through work pressure or promote employee innovation through work engagement. As a company manager, you can focus your efforts on improving the positive impact of organizational change on employee innovation by paying attention to and satisfying employees’ reasonable needs, striving to improve employees’ work engagement, actively implementing innovation incentive policies, organizing relevant innovation practice activities, and encouraging employees to They can focus on improving the positive impact of organizational change on employees’ innovation, meeting employees’ reasonable needs, improving employees’ commitment to work, actively implementing innovation incentive policies, organizing relevant innovation practice activities, encouraging employees to give full play to their initiative and creativity in the change situation, cultivating employees’ innovation consciousness and stimulating their innovation potential to improve their innovation performance.

Finally, focus on developing and improving employees’ organizational identity. Research findings show that the double-edged sword effect of organizational change on employees’ innovation performance is power-variable, and low organizational identity will increase the negative impact of organizational change and offset its positive impact to a certain extent. In Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War”, it is mentioned that “the one who wants the same thing from the top and the bottom wins”, and employees with a high sense of organizational identity are often able to “unite with the organization” and form “the same desire from the top and the bottom” to work together to achieve the goals. Therefore, it is very important to cultivate employees’ sense of organizational identity. In recruiting employees, HR should pay attention to the match between employees’ values and the organization’s cultural values, and “fasten the first button of organizational identity” when new employees join the company. Further, employee organizational identity is not static and cannot be achieved overnight, but can be cultivated and improved by the company through later efforts. Internally, enterprises should create a good working environment with transparent policies and fair systems in their daily management to ensure fair benefits for employees and win their trust in the organization, while paying attention to the quality improvement of managers, strengthening harmonious communication between management and grassroots employees, and encouraging leaders to increase humanistic care for employees at work and their family life behind them. Externally, enterprises should take more social responsibility in their business philosophy, enhance the organization’s reputation, create a positive brand image, promote employees and the organization in the rational and emotional “two-way run”, strengthen employees’ sense of organizational identity, so that employees from the heart to link their personal interests with the interests of the organization, and thus strive to create performance for the organization The brand image of the organization can be strengthened.

Limitations

This study has followed the scientific procedures in model formulation and research design, but there are still some shortcomings due to our professional ability, resource conditions and objective limitations: (1) Due to geographical limitations, this study only selected some enterprises in Shandong in the questionnaire survey, and there may be differences in the empirical results of enterprises in different regions in this topic. Future research can broaden the questionnaire distribution channels, expand the sample area, and further analyze with a more random, diverse, and universal sample to improve the generalization of the study. (2) The questionnaire adopted in this study was completed by employees’ self-assessment. Although the three-stage questionnaire design reduces homogeneous error to a certain extent, the influence of personal subjective factors on the study cannot be completely excluded. Future research can try questionnaire other assessment, up and down paired survey, etc. to further reduce homogenization error through more objective data. (3) In terms of the timing of the questionnaire, the surveyed companies were undergoing organizational change during the research process, so the data reported by employees during the three stages of the questionnaire before and after about 1.5 months came from after the organizational change and did not include the data before the organizational change, and the relationship between the relevant variables may not be convincing. Future research could follow up with companies to cover the research process before and after organizational change, and further explore the differences in the impact of organizational change on employees by comparing data from different stages.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study does not involve animal subjects. The study involves human subjects. This manuscript does not include any potentially identifiable human images/data, including individual case descriptions. There is a mutual, verbal agreement between participants and researchers.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data contains personal information that cannot be easily anonymized. The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Albrecht, S.L.; Connaughton, S.; Foster, K.; Furlong, S.; Yeow, C.J.L. Change Engagement, Change Resources, and Change Demands: A Model for Positive Employee Orientations to Organizational Change. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social Identity Theory and the Organization. Academy of Management Review 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashill, N.; Abuelsamen, A.; Gibbs, T.; Semaan, R.W. Understanding organization-customer links in a service setting in Russia. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2022, 66, 102949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Luthans, F. Experimentally analyzing the impact of leader positivity on follower positivity and performance. The Leadership Quarterly 2011, 22, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, M.T.; Stouten, J.; Camps, J.; Euwema, M. When Do Ethical Leaders Become Less Effective? The Moderating Role of Perceived Leader Ethical Conviction on Employee Discretionary Reactions to Ethical Leadership. Journal of Business Ethics 2019, 154, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G.C.; Woznyj, H.M.; Mansfield, C.A. Where is “ behavior ” in organizational behavior? A call for a revolution in leadership research and beyond. The Leadership Quarterly 2021, 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartunek, J.M.; Woodman, R.W. Beyond Lewin: Toward a Temporal Approximation of Organization Development and Change. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 2015, 2, 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.C.; Lazaric, N.; Nelson, R.R.; Winter, S.G. Applying organizational routines in understanding organizational change. Industrial and Corporate Change 2005, 14, 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, W.R.; Olson-Buchanan, J.B.; LePine, M.A. Relations between stress and work outcomes: The role of felt challenge, job control, and psychological strain. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2004, 64, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckenooghe, D.; Schwarz, G.M.; Kanar, A.; Sanders, K. Revisiting research on attitudes toward organizational change: Bibliometric analysis and content facet analysis. Journal of Business Research 2021, 135, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; He, H.; Mellahi, K. Corporate Social Responsibility, Employee Organizational Identification, and Creative Effort. Group & Organization Management 2015, 40, 323–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, P.S.; Serpe, R.T.; Stryker, S. The Causal Ordering of Prominence and Salience in Identity Theory. Social Psychology Quarterly 2014, 77, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavacciuolo, L.; Capaldo, G.; Ponsiglione, C. Digital innovation and organizational changes in the healthcare sector: Multiple case studies of telemedicine project implementation. Technovation 2022, 102550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayton, P.K.; Sala, E. Natural History: the sense of wonder, creativity and progress in ecology. Scientia marina 2001, 65, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, B.K.; Shaturaev, J.; Kurbonov, K.; Nazirjon, R. The causal nexus between innovation and economic growth: An OECD study. February 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, B.K.; Thanh Tiep Le Coffelt, T.A.; Shaturaev, J. U.S. U.S. -China trade war and competitive advantage of Vietnam.; 2022; Volume 1998, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ek Styvén, M.; Näppä, A.; Mariani, M.; Nataraajan, R. Employee perceptions of employers’ creativity and innovation: Implications for employer attractiveness and branding in tourism and hospitality. Journal of Business Research 2022, 141, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldor, L.; Vigoda-Gadot, E. The nature of employee engagement: rethinking the employee-organization relationship. International Journal of Human Resource Management 2017, 28, 526–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Mancuso, R.A.; Branigan, C.; Tugade, M.M. The Undoing Effect of Positive Emotions. Motivation and emotion 2000, 24, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Jiménez-Barrionuevo, M.M.; Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, L. Transformational leadership influence on organizational performance through organizational learning and innovation. Journal of Business Research 2012, 65, 1040–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Godwin, L.N. Is the Perception of ‘Goodness’ Good Enough? Exploring the Relationship Between Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Organizational Identification. Journal of Business Ethics 2013, 114, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goering, D.D.; Shimazu, A.; Zhou, F.; Wada, T.; Sakai, R. Not if, but how they differ: A meta-analytic test of the nomological networks of burnout and engagement. Burnout research 2017, 5, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A.; Parker, S.K. A New Model of Work Role Performance: Positive Behavior in Uncertain and Interdependent Contexts. Academy of Management Journal 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, R.P.; Choi, D. To whom does transformational leadership matter more? An examination of neurotic and introverted followers and their organizational citizenship behavior. The Leadership quarterly 2015, 26, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.X.; Wu, T.J.; Zhao, H.D.; Yang, Y. How to Motivate Employees for Sustained Innovation Behavior in Job Stressors? A Cross-Level Analysis of Organizational Innovation Climate. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetland, J.; Bakker, A.B.; Espevik, R.; Olsen, O.K. Daily work pressure and task performance: The moderating role of recovery and sleep. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetty Van Emmerik, I.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Euwema, M.C. Explaining employees’ evaluations of organizational change with the job - demands resources model. Career Development International 2009, 14, 594–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Schuler, R.S.; Jiang, K. An Aspirational Framework for Strategic Human Resource Management. The Academy of Management Annals 2014, 8, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Ning LLiu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q. Job demands-resources, job crafting and work engagement of tobacco retailers. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10, 925668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Chen, Z. Innovative Enterprises Development and Employees’ Knowledge Sharing Behavior in China: The Role of Leadership Style. Frontiers in psychology 2021, 12, 747873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashif, M.; Zarkada, A.; Thurasamy, R. Customer aggression and organizational turnover among service employees. Personnel Review 2017, 46, 1672–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Hon, A.H.Y.; Lee, D. Proactive Personality and Employee Creativity: The Effects of Job Creativity Requirement and Supervisor Support for Creativity. Creativity Research Journal 2010, 22, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Han, S.; Park, J. Is the Role of Work Engagement Essential to Employee Performance or ‘Nice to Have’ ? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.T.; Sok, P.; Mao, S. When and why does competitive psychological climate affect employee engagement and burnout? Journal of Vocational Behavior 2022, 139, 103810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, E.L. Emotion and power (as social influence): Their impact on organizational citizenship and counterproductive individual and organizational behavior. Human Resource Management Review 2010, 20, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Hirst, G.; Wu, C.; Lee, C.; Wu, W.; Chang, C. When anything less than perfect isn’t good enough: How parental and supervisor perfectionistic expectations determine fear of failure and employee creativity. Journal of Business Research 2023, 154, 113341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.C.; Jiang, F. How is Benevolent Leadership Linked to Employee Creativity? The Mediating Role of Leader–Member Exchange and the Moderating Role of Power Distance Orientation. Journal of business ethics 2018, 152, 1099–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.D.; Allen, M.; Casey, M.K.; Johnson, J.R. Reconsidering the Organizational Identification Questionnaire. Management communication quarterly 2000, 13, 626–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, Y.; Roberts, T. A novel methodology applying practice theory in pro-environmental organisational change research: Examples of energy use and waste in healthcare. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 339, 130542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, D.; Trumbach, C.; Soharu, R. The Values Change Management Cycle: Ethical Change Management. Journal of business ethics 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proost, K.; Verboon, P.; van Ruysseveldt, J. Organizational justice as buffer against stressful job demands. Journal of managerial psychology 2015, 30, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, A.E.; Griffin, M.A. Perceptions of organizational change: a stress and coping perspective. J Appl Psychol 2006, 91, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rass, L.; Treur, J.; Kucharska, W.; Wiewiora, A. Adaptive Dynamical Systems Modelling of Transformational Organizational Change with Focus on Organizational Culture and Organizational Learning. Cognitive Systems Research. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job enagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management journal 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissel, C.; Petrunoff, N.; Wen, L.M.; Crane, M. Travel to work and self-reported stress: Findings from a workplace survey in south west Sydney, Australia. Journal of Transport & Health 2014, 1, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, A.; Rohrschneider, M.; Booth, A.; Carter, P.; Walker, R.; Andrews, G. Enhancing organisational innovation capability – A practice-oriented insight for pharmaceutical companies. Technovation 2022, 115, 102461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogiest, S.; Segers, J.; van Witteloostuijn, A. Climate, communication and participation impacting commitment to change. Journal of Organizational Change Management 2015, 28, 1094–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.S.; Isha, A.S.N.B.; Benson, C.; Awan, M.I.; Naji, G.M.A.; Yusop, Y.B. Analyzing the impact of psychological capital and work pressure on employee job engagement and safety behavior. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and psychological measurement 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Prakash, G.; Kumar, A.; Mussada, E.K.; Antony, J.; Luthra, S. Analysing the relationship of adaption of green culture, innovation, green performance for achieving sustainability: Mediating role of employee commitment. Journal of cleaner production 2021, 303, 127039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Woodwark, M.J.; Konrad, A.M.; Jung, Y. Innovation strategy, voice practices, employee voice participation, and organizational innovation. Journal of Business Research 2022, 147, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.J.; Lu, C.Q.; Siu, O.L. Job insecurity and job performance: The moderating role of organizational justice and the mediating role of work engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology 2015, 100, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, P.; Fang, S. A critical view of knowledge networks and innovation performance: The mediation role of firms’ knowledge integration capability. Journal of Business Research 2018, 88, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cui, T.; Cai, S.; Ren, S. How and when high-involvement work practices influence employee innovative behavior. International journal of manpower 2022, 43, 1221–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P.; Inceoglu, I. Job engagement, job satisfaction, and contrasting associations with person–job fit. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 2012, 17, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, E.; Büttgen, M.; Bartsch, S. How to take employees on the digital transformation journey: An experimental study on complementary leadership behaviors in managing organizational change. Journal of business research 2022, 143, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.; de Menezes, L.M. High involvement management, high-performance work systems and well-being. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2011, 22, 1586–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, T.; Wang, Y. Formation of hotel employees’ service innovation performance: Mechanism of thriving at work and change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2023, 54, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.G.; Graves, C.; Shan, Y.G.; Yang, J.W. The mediating role of corporate social responsibility in corporate governance and firm performance. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 375, 134165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Ayub, A.; Ishaq, M.; Arif, S.; Fatima, T.; Sohail, H.M. Workplace ostracism and employee silence in service organizations: the moderating role of negative reciprocity beliefs. International journal of manpower 2022, 43, 1378–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, J.; Cheng, B.; Rahmadani, V.G. Supervisor Developmental Feedback and Voice: Relationship or Affect, Which Matters? Frontiers in psychology 2019, 10, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Wanberg, C.R.; Harrison, D.A.; Diehn, E.W. Ups and downs of the expatriate experience? Understanding work adjustment trajectories and career outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology 2016, 101, 549–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).