Submitted:

01 November 2023

Posted:

02 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Largest Global Producers, Their Potential and Challenges

2.1. China: A Process of Refinement of Production Technique

2.2. Indonesia: The Association Between Tilapia Culture and Rice Farming

2.3. Egypt: Good Results from Production Industrialization

2.4. Brazil: Favorable Natural Characteristics

3. Main Pathogens for Tilapia

3.1. Streptococcosis

3.2. Francisellosis

3.3. Aeromonosis

3.4. Vibriosis

3.5. Columnariosis

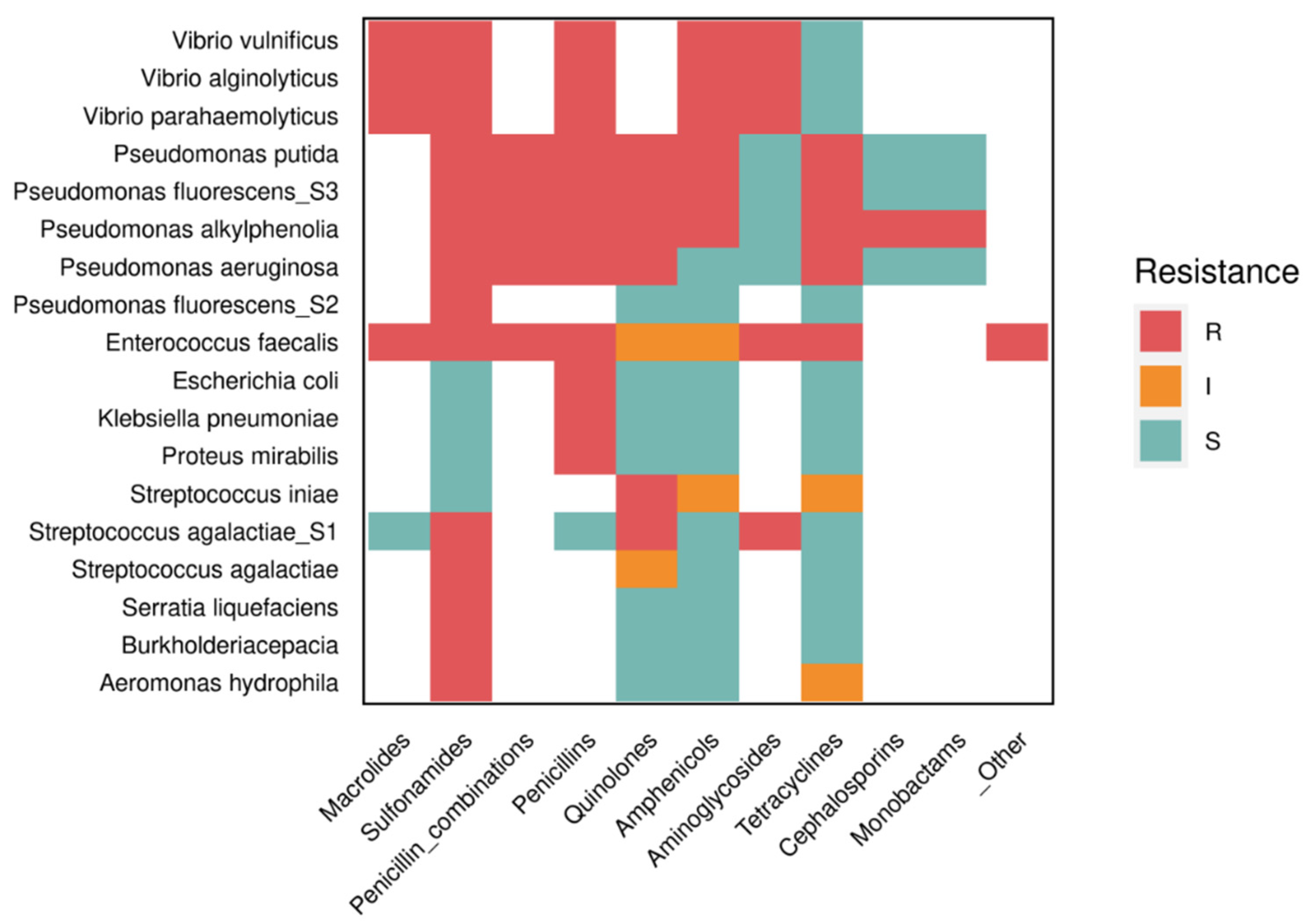

4. Use of Antibiotics in Disease Control

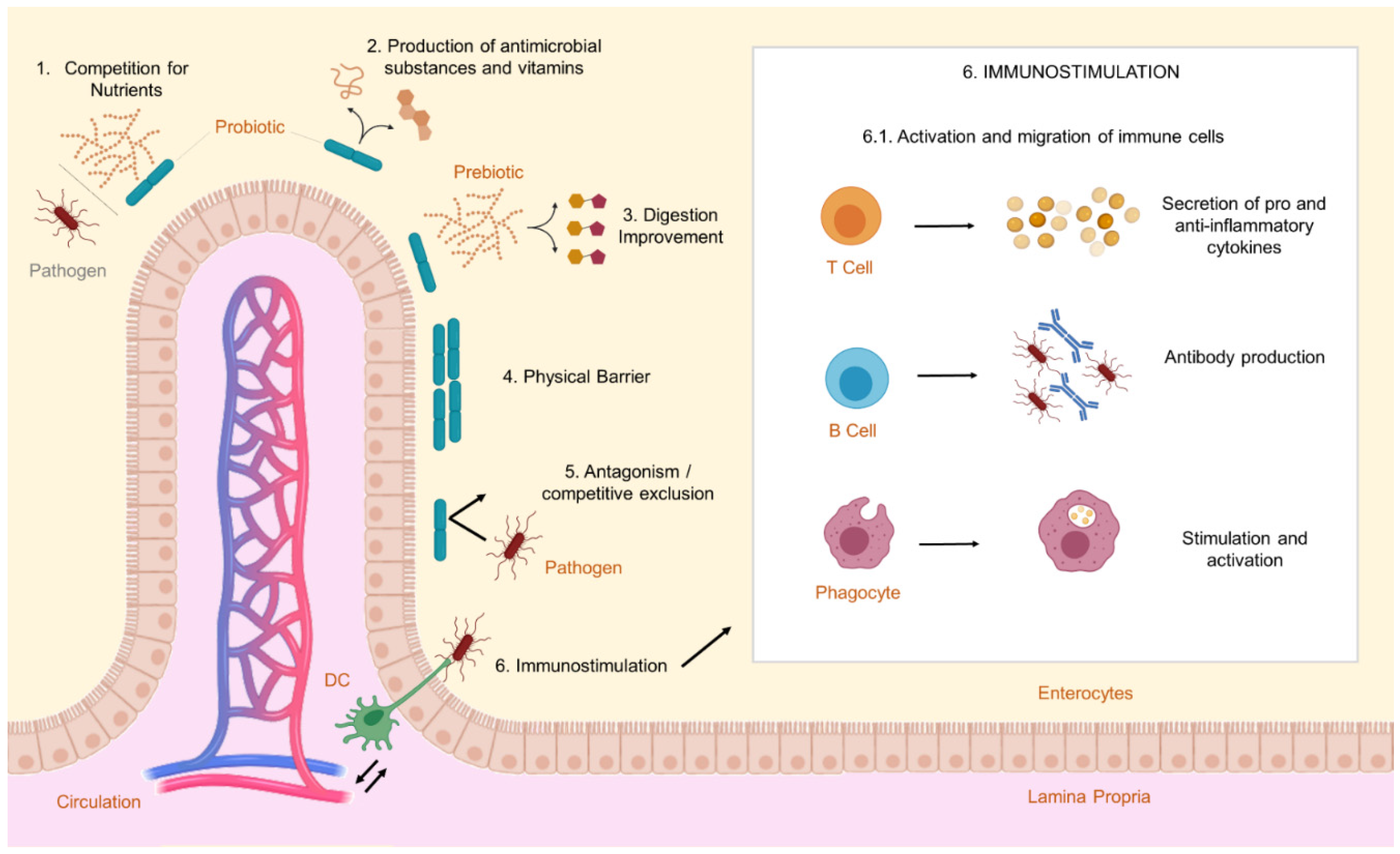

5. Benefits of Probiotics, Prebiotics and Bacteriocins in Tilapia Culture

5.1. Probiotics in Tilapia Culture

5.2. Probiotics in Combination with Prebiotics (Synbiotics)

5.3. Bacteriocins in Tilapia Culture

5.3.1. Mechanism of Action

5.3.2. Antimicrobial Potential

5.3.3. Resistance Mechanisms

5.3.4. Synergistic Effects

5.3.5. Challenges in Characterization

5.3.6. Safety and Efficacy

5.3.7. Identification Challenges

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lucas, J.S.; Southgate, P.C.; Tucker, C.S. Aquaculture: farming aquatic animals and plants. John Wiley & Sons, West Sussex, United Kingdom. 2019.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). The state of World fisheries and aquaculture. Topics fact sheets. Available online: http://www.fao.org/state-of-fisheries-aquaculture/2018/en (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Aquaculture News. May 2022, No. 65. Rome. Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc0158en (accessed on 04 February 2023).

- Woods, R.G. Future dimensions of world food and population, 1st ed.; CRC Press: New York, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kassam, L.; Dorward, A. A comparative assessment of the poverty impacts of pond and cage aquaculture in Ghana. Aquaculture 2017, 470, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, T.V.D. Aquicultura: a nova fronteira para produção de alimentos de forma sustentável. Rev. BNDES 2018, 25, 119–170. Available online: https://web.bndes.gov.br/bib/jspui/bitstream/1408/16085/1/PRArt_Aquicultura%20a%20nova%20fronteira_compl.pdf (accessed on 2023 May 28).

- SOFIA (State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture). The state of world fisheries and aquaculture. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca9229en/CA9229EN.pdf (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). The state of World fisheries and aquaculture. Topics fact sheets. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca9229en/CA9229EN.pdf (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Aquaculture development in China: the role of public sector policies. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/Y4762E/Y4762E00.htm (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- SOFIA (State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture). The state of World fisheries and aquaculture. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i5798e/i5798e.pdf (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- Calado, R.; Olivotto, I.; Oliver, M.P.; Holt, G.J. Marine ornamental species aquaculture; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- PEIXE BR. Anuário Peixe Br da piscicultura brasileira. São Paulo: Associação Brasileira de Piscicultura. Available online: https://www.peixebr.com.br/anuario-2020/ (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- Schulter, E.P.; Vieira Filho, J.E.R. Desenvolvimento e potencial da tilapicultura no Brasil. Rev. Econo. Agron. 2018, 16, 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Abdel-Rahman, M.; Mansour, E.S.; Monir, W. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility of bacterial pathogens implicating the mortality of cultured Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Egyp. Jour. Aquac. 2020, 10, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foysal, M.J.; Alam, M.; Kawser, A.R.; Hasan, F.; Rahman, M.M.; Tay, C.Y.; Gupta, S.K. Meta-omics technologies reveals beneficiary effects of Lactobacillus plantarum as dietary supplements on gut microbiota, immune response and disease resistance of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture 2020, 520, 734–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, W.A.; Piazentin, A.C.M.; de Oliveira, R.C. Bacteriocinogenic probiotic bacteria isolated from an aquatic environment inhibit the growth of food and fish pathogens. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.F.M. Tilapia culture; Academic Press: London, United Kingdom, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). National aquaculture overview – Egypt. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fishery/countrysector/naso_egypt/en (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- De Andrade, L.A.R.; de Azevedo, T.M.P. Manejo experimental de alevinos de tilápia (Oreochromis niloticus), alimentados com ração comercial e pré-probióticos. PUBVET 2018, 12, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEIXE BR. Anuário Peixe Br da piscicultura brasileira. São Paulo: Associação Brasileira de Piscicultura. 2019. Available online: https://www.peixebr.com.br/anuario-peixe-br-da-piscicultura-2019/ (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- Gu, D.E.; Yu, F.D.; Yang, Y.X.; Xu, M.; Wei, H.; Luo, D.; Hu, Y.C. Tilapia fisheries in Guangdong Province, China: Socio-economic benefits, and threats on native ecosystems and economics. Fishe. Manag. Ecol. 2019, 26, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Dai, Y.; Gong, Y. Economic profitability of tilapia farming in China. Aquac. Intern. 2017, 25, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Gong, Y.; Yuan, Y. Technical efficiency of different farm sizes for tilapia farming in China. Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Ming, J. Status and trends of the tilapia farming industry development. Aquac. Indai China: Succ. Stor. Mod. Tren. 2018, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, F.; Yuan, X. Technical efficiency of Tilapia production in Malawi and China: Application of stochastic frontier production approach. Jour. Aquac. Res. Develop. 2018, 9, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.Y.; Yuan, Y.M.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H.Y. Competitiveness of Chinese and Indonesian tilapia exports in the US market. Aquac. Intern. 2020, 28, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Petersen, G.; Barco, L.; Hvidtfeldt, K.; Liu, L.; Dalsgaard, A. Salmonella Weltevreden in integrated and non-integrated tilapia aquaculture systems in Guangdong, China. Food Microb. 2017, 65, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.M.; Fitzsimmons, K. From Africa to the world—The journey of Nile tilapia. Revi. Aquac. 2023, 15, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, M.; Dickson, C.; Dickson, M.; Leschen, W.; Baily, J.; Muir, F.; Weidmann, M. Identification of Tilapia Lake Virus in Egypt in Nile tilapia affected by ‘summer mortality’syndrome. Aquaculture 2017, 473, 430–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wati, L.A.; Harahab, N.; Riniwati, H.; Utami, T.N. Development of tilapia cultivation strategy based local economy: case study in Wonogiri, Central Java. IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Envir. Sci. 2020, 493, 012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Global aquaculture production 2019, 1950-2017. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fishesy/statistics/global-aquaculture-production/query/en (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- Wijayanto, D.; Kurohman, F.; Nugroho, R.A. Bioeconomic of profit maximization of red tilapia (Oreochromis sp.) culture using polynomial growth model. IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Envir. Sci. 2018, 139, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaalan, M.; El-Mahdy, M.; Saleh, M.; El-Matbouli, M. Aquaculture in Egypt: insights on the current trends and future perspectives for sustainable development. Revi. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2018, 26, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goada, A.M.A.; Essa, M.A.; Hassaan, M.S.; Sharawy, Z. Bio economic features for aquaponic systems in Egypt. Turk. Jour. Fish. Aqua. Sci. 2015, 15, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiadi, E.; Widyastuti, Y.R.; Prihadi, T.H. Water quality, survival, and growth of red tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus cultured in aquaponics systems. E3S Web of Conf. 2018, 47, 02006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parata, L.; Mazumder, D.; Sammut, J.; Egan, S. Diet type influences the gut microbiome and nutrient assimilation of Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Plos one 2020, 15, e0237775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, W.Y.; Man, Y.B.; Wong, M.H. Use of food waste, fish waste and food processing waste for China’s aquaculture industry: Needs and challenge. Sci. Total Envir. 2018, 613, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadjar, M.; Sanoesi, E.; Mintiya, Y.A.; Hakim, L. Effect of squid powder (Loligo Sp.) on antibody titer and bacteria density in blood of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) infected by Aeromonas hydrophila. Aquac. Indo. 2020, 21, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.F.M. On-farm feed management practices for Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in Egypt. On-farm feeding and feed management in aquaculture. FAO Fish. Aquac. Techn. Paper 2013, 583, 101–129. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, M.; Nasr-Allah, A.; Kenawy, D.; Kruijssen, F. Increasing fish farm profitability through aquaculture best management practice training in Egypt. Aquaculture 2016, 465, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.A.H.; El-kady, A.H.M.; Abu Almaaty, A.H.M.; Ramadan, M.A. Effect of environmental pollution on gonads histology of the Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus from Lake Manzala, Egypt. Egyp. Jour. Aqua. Biol. Fish 2018, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, R.K.; Omer, A.M.; Othman, D.I. Bio-Fertilization Effect on the Productivity and Biodiesel Quality of Castor Plant Oil under El-Salam Canal Irrigation Condition. Alexa. Sci. Exch. Jour. 2018, 39, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, P.; Fathi, M.A.; Fischer, A.; Mohan, C.; Schieck, E.; Mishra, N.; Jores, J. Detection of tilapia lake virus in Egyptian fish farms experiencing high mortalities in 2015. Jour. Fish Dise. 2017, 40, 1925–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donia, G.; Hafez, A.; Wassif, I. Studies on some heavy metals and bacterial pollutants in tilapia fish of El Salam Canal, Northern Sinai, Egypt. Egyp. Jour. Aqua. Biol. Fish. 2017, 21, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.E.; Jansen, M.D.; Mohan, C.V.; Delamare-Deboutteville, J.; Charo-Karisa, H. Key risk factors, farming practices and economic losses associated with tilapia mortality in Egypt. Aquaculture 2020, 527, 735438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanez, A.Y.; Guimarães, D.D.; Maia, G.D.S.; Muñoz, A.E.P.; Pedroza Filho, M.X. Potencial e barreiras para a exportação de carne de tilápias pelo Brasil. Embrapa Pesca e Aquic. 2019, 25, 155–213. [Google Scholar]

- Castilho-Barros, L.; Owatari, M.S.; Mouriño, J.L.P.; Silva, B.C.; Seiffert, W.Q. Economic feasibility of tilapia culture in southern Brazil: A small-scale farm model. Aquaculture 2020, 515, 734551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghiante, F.; de Mattos Ferrasso, M.; Rodrigues, M.V.; Biondi, G.F.; Martins, O.A. Francisella spp. em tilápias no Brasil: Uma revisão. Ver. Bras. Higi. Sanid. Ani. 2017, 11, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, S.C.R.P.; de Oliveira, E.D.C.P.; de Seixas Filho, J.T. Aspectos da aquicultura e sua importância na produção de alimentos de alto valor biológico. Semioses 2017, 11, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, R.; Muñoz, A.; Tahim, E.; Tenório, R.; Muehlmann, L.; Silva, F.; Flores, R. Dimensão socioeconômica da tilapicultura no Brasil, 1st ed.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brasil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- CNA (Confederação da agricultura e pecuária do Brasil). Tilápia, cenário econômico 2018. Available online: https://www.cnabrasil.org.br/assets/arquivos/artigostecnicos/AntecipaCNACena%CC%81rio-Econo%CC%82mico-Tilapia.pdf (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- Kubitza, D.; Becka, M.; Mueck, W.; Halabi, A.; Maatouk, H.; Klause, N.; Bruck, H. Effects of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety of rivaroxaban, an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor. Brit. Jour. Clin. Pharm. 2010, 70, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedroza Filho, M.X. Análise comparativa de resultados econômicos dos polos piscicultores no segundo trimestre de 2015. Ativ. Aqui. CNA 2015. Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/busca-de-publicacoes/-/publicacao/1041290/analise-comparativa-de-resultados-economicos-dos-polos-piscicultores-no-segundo-trimestre-de-2015 (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- Igarashi, M.A. Aspectos tecnológicos e perspectivas de desenvolvimento do cultivo de tilápia no Brasil. Arqu. Ciên. Veter. Zool. da UNIPAR 2018, 21, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowland, S.J.; O’Connor, W.A.; Osborne, M.W.; Southgate, P.C. Current status and potential of tropical rock oyster aquaculture. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2020, 28, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asche, F.; Cojocaru, A.L.; Roth, B. The development of large scale aquaculture production: A comparison of the supply chains for chicken and salmon. Aquaculture 2018, 493, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamom, A.; Alam, M.M.; Iqbal, M.M.; Khalil, S.M.I.; Parven, M.; Sumon, T.A.; Mamun, M.A.A. Identification of pathogenic bacteria from diseased nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus with their sensitivity to antibiotics. Intern. Jour. Curr. Microb. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 716–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Cabrera, L.; Olivera, B.C.L.; Villavicencio-Pulido, J.G.; Luna, R.J.O. Proximity and density of neighboring farms and water supply, as risk factors for bacteriosis: A case study of spatial risk analysis in tilapia and rainbow trout farms of Oaxaca, Mexico. Aquaculture 2020, 520, 734955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanja, D.W.; Mbuthia, P.G.; Waruiru, R.M.; Bebora, L.C.; Ngowi, H.A. Natural concurrent infections with Black Spot Disease and multiple bacteriosis in farmed Nile tilapia in Central Kenya. Veter. Med. Intern. 2020, 8821324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, E.; Zayas, M.; Tobar, J.; Illanes, O.; Yount, S.; Francis, S.; Dennis, M.M. Laboratory-controlled challenges of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) with Streptococcus agalactiae: comparisons between immersion, oral, intracoelomic and intramuscular routes of infection. Jour. Compar. Pathol. 2016, 155, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhu, J.; Chen, K.; Gao, T.; Yao, H.; Liu, Y.; Lu, C. Development of Streptococcus agalactiae vaccines for tilapia. Disea. Aqua. Organ. 2016, 122, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.S.; Siti-Zahrah, A.; Syafiq, M.R.M.; Amal, M.N.A.; Firdaus-Nawi, M.; Zamri-Saad, M. Feed-based vaccination regime against streptococcosis in red tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus x Oreochromis mossambicus. BMC Veter. Resea. 2016, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Fang, W.; Ke, B.; He, D.; Liang, Y.; Ning, D.; Ke, C. Inapparent Streptococcus agalactiae infection in adult/commercial tilapia. Scient. Rep. 2016, 6, 26319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Li, J.; Lu, M.; Deng, G.; Jiang, X.; Tian, Y.; Jian, Q. Identification and molecular typing of Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from pond-cultured tilapia in China. Fish. Sci. 2011, 77, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huang, T.; Liang, W.; Chen, M. Development of an attenuated oral vaccine strain of tilapia Group B Streptococci serotype Ia by gene knockout technology. Fish & Shellf. Immun. 2019, 93, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, D.; Neto, R.T. As principais bacterioses que acometem a tilápia do Nilo (Oreochromis niloticus): Revisão de literatura. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. FAG 2019, 2, 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Veselá, K.; Kumherová, M.; Klojdová, I.; Solichová, K.; Horáčková, Š.; Plocková, M. Selective culture medium for the enumeration of Lactobacillus plantarum in the presence of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus. LWT 2019, 114, 108365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palang, I.; Hirono, I.; Senapin, S.; Sirimanapong, W.; Withyachumnarnkul, B.; Vanichviriyakit, R. Cytotoxicity of Streptococcus agalactiae secretory protein on tilapia cultured cells. Jour. Fish Dis. 2020, 43, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bal, F.A.; Ozkocak, I.; Cadirci, B.H.; Karaarslan, E.S.; Cakdinleyen, M.; Agaccioglu, M. Effects of photodynamic therapy with indocyanine green on Streptococcus mutans biofilm. Photod. Photod. Ther. 2019, 26, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.T.; Guo, W.L.; Meng, A.Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, S.F.; Xie, Z.Y.; He, C. A metabolomic investigation into the effects of temperature on Streptococcus agalactiae from Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) based on UPLC–MS/MS. Veter. Microb. 2017, 210, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laith, A.A.; Abdullah, M.A.; Nurhafizah, W.W.I.; Hussein, H.A.; Aya, J.; Effendy, A.W.M.; Najiah, M. Efficacy of live attenuated vaccine derived from the Streptococcus agalactiae on the immune responses of Oreochromis niloticus. Fish & Shellf. Immun 2019, 90, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, H.; Gabr, A.N.M.; Aboyadak, I.; Saber, N. Subcellular degenerative changes in hepatopancreas and posterior kidney of Streptococcus iniae infected Nile tilapia using transmission electron microscope. Egyp. Jour. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2019, 23, 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Suhermanto, A.; Sukenda, S.; Zairin Jr., M.; Lusiastuti, A.M.; Nuryati, S. Characterization of Streptococcus agalactiae bacterium isolated from tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) culture in Indonesia. Aquac. Aquar. Conserv. Legisl. 2019, 12, 756–766. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Wang, K.Y.; Huang, X.L.; Chen, D.F.; Li, C.W.; Ren, S.Y.; Lai, W.M. Streptococcus agalactiae, an emerging pathogen for cultured ya-fish, Schizothorax prenanti, in China. Transb. Emer. Dis. 2012, 59, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iregui, C.A.; Comas, J.; Vásquez, G.M.; Verjan, N. Experimental early pathogenesis of Streptococcus agalactiae infection in red tilapia Oreochromis spp. Jour. Fish Dis. 2016, 39, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, E.; Wang, R.; Wiles, J.; Baumgartner, W.; Green, C.; Plumb, J.; Hawke, J. Characterization of isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae from diseased farmed and wild marine fish from the US Gulf Coast, Latin America, and Thailand. Jour. Aqua. Ani. Heal. 2015, 27, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Machado, G.; Barato-Gómez, P.; Iregui-Castro, C. Morphological characterization of the adherence and invasion of Streptococcus agalactiae to the intestinal mucosa of tilapia Oreochromis sp.: an in vitro model. Jour. Fish Dis. 2019, 42, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, P.; Mon-on, N.; Jaemwimol, P.; Tattiyapong, P.; Surachetpong, W. Coinfection of tilapia lake virus and Aeromonas hydrophila synergistically increased mortality and worsened the disease severity in tilapia (Oreochromis spp.). Aquaculture 2020, 520, 734746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, C.A.G.; Tavares, G.C.; Figueiredo, H.C.P. Outbreaks and genetic diversity of Francisella noatunensis subsp orientalis isolated from farm-raised Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in Brazil. Gen. Mol. Res. 2014, 13, 5704–5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facimoto, C.T.; Chideroli, R.T.; Di Santis, G.W.; Gonçalves, D.D.; Do Carmo, A.O.; Kalapothakis, E.; Pereira, U.P. Complete genome sequence of Francisella noatunensis subsp. orientalis strain F1 and prediction of vaccine candidates against warm and cold-water fish francisellosis. Gen. Mol. Res. 2019, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, E.; Baumgartner, W.; Wiles, J.; Hawke, J.P. Francisella asiatica as the causative agent of piscine francisellosis in cultured tilapia (Oreochromis sp.) in the United States. Jour. Vet. Diagn. Inv. 2011, 23, 821–825. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastião, F.A.; Pilarski, F.; Kearney, M.T.; Soto, E. Molecular detection of Francisella noatunensis subsp. orientalis in cultured Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.) in three Brazilian states. Jour. Fish Dis. 2017, 40, 1731–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amal, M.N.A.; Saad, M.Z.; Zahrah, A.S.; Zulkafli, A.R. Water quality influences the presence of Streptococcus agalactiae in cage cultured red hybrid tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus × Oreochromis mossambicus. Aquac. Res. 2015, 46, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, G.B.N.; Tavares, G.C.; Pereira, F.L.; Figueiredo, H.C.P.; Leal, C.A.G. Natural coinfection by Streptococcus agalactiae and Francisella noatunensis subsp. orientalis in farmed Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.). Jour. Fish Dis. 2017, 40, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.T.; Techatanakitarnan, C.; Jindakittikul, P.; Thaiprayoon, A.; Taengphu, S.; Charoensapsri, W.; Senapin, S. Aeromonas jandaei and Aeromonas veronii caused disease and mortality in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (L.). Jour. Fish Dis. 2017, 40, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D.C.; Eto, S.F.; Funnicelli, M.I.; Fernandes, C.C.; Charlie-Silva, I.; Belo, M.A.; Pizauro, J.M. Immunoglobulin Y in the diagnosis of Aeromonas hydrophila infection in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture 2019, 500, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amal, M.N.A.; Koh, C.B.; Nurliyana, M.; Suhaiba, M.; Nor-Amalina, Z.; Santha, S.; Zamri-Saad, M. A case of natural co-infection of Tilapia Lake Virus and Aeromonas veronii in a Malaysian red hybrid tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus × O. mossambicus) farm experiencing high mortality. Aquaculture 2018, 485, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.; Zharan, E.; Saad, R.; Zaki, V. Prevalence, molecular characterization, virulotyping, and antibiotic resistance of motile aeromonads isolated from Nile tilapia farms in northern Egypt. Mans. Vet. Med. Jour. 2020, 21, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Tawwab, M.; Samir, F.; Abd El-Naby, A.S.; Monier, M.N. Antioxidative and immunostimulatory effect of dietary cinnamon nanoparticles on the performance of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (L.) and its susceptibility to hypoxia stress and Aeromonas hydrophila infection. Fish & Shellf. 2018, 74, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farias, T.H.V.; Arijo, S.; Medina, A.; Pala, G.; da Rosa, P.E.J.; Montassier, H.J.; de Andrade, B.M.A. Immune responses induced by inactivated vaccine against Aeromonas hydrophila in pacu, Piaractus mesopotamicus. Fish & Shellf. Immun. 2020, 101, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basri, L.; Nor, R.M.; Salleh, A.; Saad, M.Z.; Barkham, T.; Amal, M.N.A. Co-infections of tilapia lake virus, Aeromonas hydrophila and Streptococcus agalactiae in farmed red hybrid tilapia. Animals 2020, 10, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajales-Hahn, S.; Hahn-von, H.C.M.; Grajales-Quintero, A. Case report of Aeromonas salmonicida in nilotic tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in caldas, Colombia. Boletín Científico 2018, 22, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsheshtawy, A.; Yehia, N.; Elkemary, M.; Soliman, H. Investigation of Nile tilapia summer mortality in Kafr El-Sheikh governorate, Egypt. Gen. Aqua. Org. 2019, 3, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addo, S.; Carrias, A.A.; Williams, M.A.; Liles, M.R.; Terhune, J.S.; Davis, D.A. Effects of Bacillus subtilis strains and the prebiotic Previda® on growth, immune parameters and susceptibility to Aeromonas hydrophila infection in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Aquaculture Research 2017, 48, 4798–4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauzi, N.A.; Mohamad, N.; Azzam-Sayuti, M.; Yasin, I.S.M.; Saad, M.Z.; Nasruddin, N.S.; Azmai, M.N.A. Antibiotic susceptibility and pathogenicity of Aeromonas hydrophila isolated from red hybrid tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus × Oreochromis mossambicus) in Malaysia. Vet. World 2020, 13, 2166. [Google Scholar]

- Hal, A.M.; Manal, I. Gene expression and histopathological changes of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) infected with Aeromonas hydrophila and Pseudomonas fluorescens. Aquaculture 2020, 526, 735392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos-Francisco, D.; Castillo, Y.; De La Rosa, F.; Vásquez, W.; Reyes-Santiago, R.; Cuello, A.; Esteban, M.Á. Bactericidal effect on skin mucosa of dietary guava (Psidium guajava L.) leaves in hybrid tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus × O. mossambicus). Jour. Ethnop. 2020, 259, 112838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboyadak, I.M.; Ali, N.G.M.; Goda, A.M.A.S.; Saad, W.; Salam, A.M.E. Non-Selectivity of RS media for Aeromonas hydrophila and TCBS media for Vibrio species isolated from diseased Oreochromis niloticus. Jour. Aqua. Res. Devel. 2017, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumithra, T.G.; Reshma, K.J.; Anusree, V.N.; Sayooj, P.; Sharma, S.R.K.; Suja, G.; Sanil, N.K. Pathological investigations of Vibrio vulnificus infection in Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.) cultured at a floating cage farm of India. Aquaculture 2019, 511, 734217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Kojima, S.; Homma, M. Structure, gene regulation and environmental response of flagella in Vibrio. Front. Microb. 2013, 4, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novriadi, R. Vibriosis in aquaculture. Omni-Akuatika 2016, 12, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Austin, C.; Oliver, J.D.; Alam, M.; Ali, A.; Waldor, M.K.; Qadri, F.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Vibrio spp. infections. Nature Rev. Dis. Prim. 2018, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrok, M.A.E.; Wahdan, A. The immune modulatory effect of oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) essential oil on Tilapia zillii following intraperitoneal infection with Vibrio anguillarum. Aquac. Intern. 2018, 26, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastião, F.A.; Nomura, D.; Sakabe, R.; Pilarski, F. Hematology and productive performance of nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) naturally infected with Flavobacterium columnare. Braz. Jour. Microb. 2011, 42, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonmongkol, P.; Sukhavachana, S.; Ampolsak, K.; Srisapoome, P.; Suwanasopee, T.; Poompuang, S. Genetic parameters for resistance against Flavobacterium columnare in Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758). Jour. Fish Dis. 2018, 41, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, C.A.G.; Carvalho-Castro, G.A.; Sacchetin, P.S.C.; Lopes, C.O.; Moraes, A.M.; Figueiredo, H.C.P. Oral and parenteral vaccines against Flavobacterium columnare: evaluation of humoral immune response by ELISA and in vivo efficiency in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquac. Intern. 2010; 18, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoi, L.N.D.; Wijngaard, J.; Lutz, C. Farming system practices of seafood production in Vietnam: the case study of Pangasius small-scale farming in the Mekong River Delta. Asean Bus. Case Stud. 2008, 27, 45–69. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). The state of World fisheries and aquaculture. Topics fact sheets. 2016. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5798e.pdf (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- Brunton, L.A.; Desbois, A.P.; Garza, M.; Wieland, B.; Mohan, C.V.; Häsler, B.; Nguyen-Viet, H. Identifying hotspots for antibiotic resistance emergence and selection, and elucidating pathways to human exposure: Application of a systems-thinking approach to aquaculture systems. Sci. Total Envir. 2019, 687, 1344–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, M.; Islam, S.R.; Osman, M.H.; Rahman, M.K.; Uddin, M.N.; Kamal, M.; Reza, M.S. Antibacterial activity of oxytetracycline on microbial ecology of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) gastrointestinal tract under laboratory condition. Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 2125–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.B.; Young, K.; Silver, L.L. What is an “ideal” antibiotic? Discovery challenges and path forward. Bioch. Pharmac. 2017, 133, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastalho, S.; Silva, G.; Ramos, F. Uso de antibióticos em aquacultura e resistência bacteriana: Impacto em saúde pública. Acta Farm. Portug. 2014, 3, 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Limbu, S.M.; Zhou, L.; Sun, S.X.; Zhang, M.L.; Du, Z.Y. Chronic exposure to low environmental concentrations and legal aquaculture doses of antibiotics cause systemic adverse effects in Nile tilapia and provoke differential human health risk. Envir. Internat. 2018, 115, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makled, S.O.; Hamdan, A.M.; El-Sayed, A.F.M. Growth promotion and immune stimulation in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, fingerlings following dietary administration of a novel marine probiotic, Psychrobacter maritimus S. Prob. Antim. Prot. 2019, 12, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Zhang, C.; Fan, L.; Qiu, L.; Wu, W.; Meng, S.; Chen, J. Occurrence of antibiotics and their impacts to primary productivity in fishponds around Tai Lake, China. Chemosphere 2016, 161, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States) / WHO (World Healt Organization). FAO/WHO expert meeting on foodborne antomicrobial resistance: Role of environment, crops and biocides. 2008. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/CA0963EN/ca0963en.pdf (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- Lulijwa, R.; Rupia, E.J.; Alfaro, A.C. Antibiotic use in aquaculture, policies and regulation, health and environmental risks: a review of the top 15 major producers. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 640–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Antimicrobial usage in aquaculture. 2017. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fi/static-media/MeetingDocuments/WorkshopAMR/presentations/09Lavila Pitogo.pdf (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). China: Development of nation action plans on AMR: Aquaculture component, project accomplishments and impacts. 2017. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fi/static-media/MeetingDocuments/WorkshopAMR17/presentations/23.pdf (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- Arumugam, U.; Stalin, N.; Rebecca, G.P. Isolation, molecular identification and antibiotic resistance of Enterococcus faecalis from diseased Tilapia. Intern. Jour. Curr. Microb. App. Sci. 2017, 6, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEIXE BR. Anuário Peixe Br da piscicultura brasileira 2018. São Paulo: Associação Brasileira de Piscicultura. 2018. Available online: https://www.peixebr.com.br/anuario2018/ (accessed on 2023 February 04).

- Monteiro, S.H.; Garcia, F.; Gozi, K.S.; Romera, D.M.; Francisco, J.G.; Moura-Andrade, G.C.; Tornisielo, V.L. Relationship between antibiotic residues and occurrence of resistant bacteria in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) cultured in cage-farm. Jour. Envir. Sci. Heal. 2016, 51, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, K.M.; da Silva Pires, Á.; Franco, O.L.; Orabi, A.; Ali, A.H.; Hamada, M.; Elbehiry, A. Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) as an aquatic vector for Pseudomonas species: Quorum sensing association with antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation and virulence. Aquaculture 2021, 532, 736068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongkao, K.; Sudjaroen, Y. Beta-lactamase and integron-associated antibiotic resistance genes of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from Tilapia fishes (Oreochromis niloticus). Jour.App. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 9, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangwetngam, M.; Suanyuk, N.; Kong, F.; Phromkunthong, W. Serotype distribution and antimicrobial susceptibilities of Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from infected cultured tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in Thailand: Nine-year perspective. Jour. Med. Microb. 2016, 65, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, R.H.; Peng, T.L.; Ong, B.L.; Suhana, M.Y.S.; Hamid, N.H.; Afifah, M.N.F.; Raina, M.S. Antibiotics resistance of Vibrio spp. isolated from diseased seabass and tilapia in cage culture. Procee. Inter. Sem. Lives. Prod. Vet. Tech. 2018, 1, 554–560. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, P.; Mao, D.; Luo, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, B.; Xu, L. Occurrence of sulfonamide and tetracycline-resistant bacteria and resistance genes in aquaculture environment. Water Res. 2012, 46, 2355–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidi, L.R.; Santos, F.A.; Ribeiro, A.; Fernandes, C.; Silva, L.H.M.; Gloria, M.B.A. Quinolones and tetracyclines in aquaculture fish by a simple and rapid LC-MS/MS method. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaunt, P.S.; Gao, D.X.; Wills, R. Preparation of ormetoprim–sulfadimethoxine-medicated discs for disc diffusion assay. North Amer. Jour. Aqua. 2011, 73, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskins, H.R.; Collier, C.T.; Anderson, D.B. Antibiotics as growth promotants: mode of action. Animal Biotec. 2002, 13, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuebutornye, F.K.; Abarike, E.D.; Sakyi, M.E.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Z. Modulation of nutrient utilization, growth, and immunity of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus: the role of probiotics. Aquac. Intern. 2020, 28, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasslöf, P.; Stecksén-Blicks, C. Probiotic bacteria and dental caries. In The Impact of Nutrition and Diet on Oral Health; Karger Publishers: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Umu, Ö.C.; Rudi, K.; Diep, D.B. Modulation of the gut microbiota by prebiotic fibres and bacteriocins. Mic. Ecol. Heal. Disea. 2017, 28, 1348886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, H.H.; Wu, S.L.; Zhu, C.H.; Seri, H.I.; Zhu, G.Q. The potential benefits of probiotics in animal production and health. Jour. Ani. Vet. Adv. 2009, 8, 313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Begum, N.; Islam, M.S.; Haque, A.K.M.F.; Suravi, I.N. Growth and yield of monosex tilapia Oreochromis niloticus in floating cages fed commercial diet supplemented with probiotics in freshwater pond, Sylhet. Bangl. Jour. Zool. 2017, 45, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, P.; Edwards, R.A.; Greenhalgh, J.F.D.; Morgan, C.A.; Sinclair, L.A.; Wilkinson, R.G. Animal Nutrition, 7th edition; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, England, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wieërs, G.; Belkhir, L.; Enaud, R.; Leclercq, S.; Philippart de Foy, J.M.; Dequenne, I.; Cani, P.D. How probiotics affect the microbiota. Front. Cell. Infec. Microb. 2020, 9, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, G.; Nandi, A.; Ray, A.K. Assessment of hemolytic activity, enzyme production and bacteriocin characterization of Bacillus subtilis LR1 isolated from the gastrointestinal tract of fish. Arch. Microb. 2017, 199, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawood, M.A.; Eweedah, N.M.; Moustafa, E.M.; Farahat, E.M. Probiotic effects of Aspergillus oryzae on the oxidative status, heat shock protein, and immune related gene expression of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) under hypoxia challenge. Aquaculture 2020, 520, 734669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.Y.; Chen, S.W.; Hu, S.Y. Improvements in the growth performance, immunity, disease resistance, and gut microbiota by the probiotic Rummeliibacillus stabekisii in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish & Shellf. Immun. 2019, 92, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Doan, H.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Khanongnuch, C.; Kanpiengjai, A.; Unban, K.; Srichaiyo, S. Host-associated probiotics boosted mucosal and serum immunity, disease resistance and growth performance of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture 2018, 491, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarike, E.D.; Cai, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, H.; Chen, L.; Jian, J.; Kuebutornye, F.K. Effects of a commercial probiotic BS containing Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis on growth, immune response and disease resistance in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Fish & Shellf. Immun. 2018, 82, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobi, N.; Vaseeharan, B.; Chen, J.C.; Rekha, R.; Vijayakumar, S.; Anjugam, M.; Iswarya, A. Dietary supplementation of probiotic Bacillus licheniformis Dahb1 improves growth performance, mucus and serum immune parameters, antioxidant enzyme activity as well as resistance against Aeromonas hydrophila in tilapia Oreochromis mossambicus. Fish & Shellf. Immun. 2018, 74, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, K.M.; Reda, R.M. Improvement of immunity and disease resistance in the Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, by dietary supplementation with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Fish & Shellf. Immun. 2015, 44, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efendi, Y. Bacillus subtilis strain VITNJ1 potential probiotic bacteria in the gut of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) are cultured in floating net, Maninjau lake, West Sumatra. Pak. Jour. Nut. 2014, 13, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, L.; Telli, G.S.; de Carla Dias, D.; Gonçalves, G.S.; Ishikawa, C.M.; Cavalcante, R.B.; Ranzani-Paiva, M.J.T. Effect of feeding strategy of probiotic Enterococcus faecium on growth performance, hematologic, biochemical parameters and non-specific immune response of Nile tilapia. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 16, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.W.; Chen, C.N.; Pan, C.Y. Antimicrobial status of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fed Enterococcus avium originally isolated from goldfish intestine. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 17, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, J.S.; Choresca, C.H.; Quiazon, K.M.A. Selection and screening of bacteria from African nightcrawler, Eudrilus eugeniae (Kinberg, 1867) as potential probiotics in aquaculture. Wor. Jour. Microb. Biotec. 2020, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poolsawat, L.; Li, X.; He, M.; Ji, D.; Leng, X. Clostridium butyricum as probiotic for promoting growth performance, feed utilization, gut health and microbiota community of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus × O. aureus). Aquac. Nut. 2020, 26, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, M.C.; Dias, D.C.; Araujo, F.V.A.P.; Ishikawa, C.M.; Tachibana, L. Probiotic Bacillus subtilis and Lactobacillus plantarum in diet of nile tilapia. Bol. Inst. Pesca 2019, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Wang, M.; Gao, F.; Lu, M.; Chen, G. Effects of dietary probiotic supplementation on the growth, gut health and disease resistance of juvenile Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Ani. Nut. 2020, 6, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doan, H.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Tapingkae, W.; Seel-Audom, M.; Jaturasitha, S.; Dawood, M.A.; Esteban, M.Á. Boosted growth performance, mucosal and serum immunity, and disease resistance Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fingerlings using corncob-derived xylooligosaccharide and Lactobacillus plantarum CR1T5. Prob. Antim. Prot. 2019, 12, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.W.; Liu, C.H.; Hu, S.Y. Dietary administration of probiotic Paenibacillus ehimensis NPUST1 with bacteriocin-like activity improves growth performance and immunity against Aeromonas hydrophila and Streptococcus iniae in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish & Shellf. Immun. 2019, 84, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewaka, M.; Trullas, C.; Chotiko, A.; Rodkhum, C.; Chansue, N.; Boonanuntanasarn, S.; Pirarat, N. Efficacy of synbiotic Jerusalem artichoke and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-supplemented diets on growth performance, serum biochemical parameters, intestinal morphology, immune parameters and protection against Aeromonas veronii in juvenile red tilapia (Oreochromis spp.). Fish & Shellf. Immun. 2019, 86, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaktcham, P.M.; Temgoua, J.B.; Zambou, F.N.; Diaz-Ruiz, G.; Wacher, C.; de Lourdes Pérez-Chabela, M. In vitro evaluation of the probiotic and safety properties of bacteriocinogenic and non-bacteriocinogenic lactic acid bacteria from the intestines of nile tilapia and common carp for their use as probiotics in aquaculture. Prob. Antim. Prot. 2018, 10, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Aktar, S.; Faruk, M.O.; Uddin, M.S.; Ferdouse, J.; Anwar, M.N. Probiotic potentiality of Lactobacillus coryniformis subsp. Torquens MTi1 and Lactobacillus coryniformis MTi2 isolated from intestine of Nile tilapia: An in vitro evaluation. Jour. Pure App. Microb. 2018, 12, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo, S.; Carrias, A.A.; Williams, M.A.; Liles, M.R.; Terhune, J.S.; Davis, D.A. Effects of Bacillus subtilis strains on growth, immune parameters, and Streptococcus iniae susceptibility in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Jour. World Aquac. Soc. 2017, 48, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, A.A.; Yomla, R.; Jaramillo-Torres, A.; Rodiles, A.; Merrifield, D.L.; Davies, S.J. Combined effects of exogenous enzymes and probiotic on Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) growth, intestinal morphology and microbiome. Aquaculture 2016, 463, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, R.M; Selim, K.M. Evaluation of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens on the growth performance, intestinal morphology, hematology and body composition of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Aquac. Intern. 2015, 23, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Long, W.Q.; He, J.Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Si, Y.Q.; Tian, L.X. Effects of dietary Bacillus licheniformis on growth performance, immunological parameters, intestinal morphology and resistance of juvenile Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) to challenge infections. Fish & Shellf. Immun. 2015, 46, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyat, M.S.; Labib, H.M.; Mahmoud, H.K. A probiotic cocktail as a growth promoter in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Jour. App. Aquac. 2014, 26, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telli, G.S.; Ranzani-Paiva, M.J.T.; de Carla Dias, D.; Sussel, F.R.; Ishikawa, C.M.; Tachibana, L. Dietary administration of Bacillus subtilis on hematology and non-specific immunity of Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus raised at different stocking densities. Fish & Shellf. Immun. 2014, 39, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.H.; Refat, N.A.A. Pathological evaluation of probiotic, Bacillus subtilis, against Flavobacterium columnare in Tilapia nilotica (Oreochromis niloticus) fish in Sharkia Governorate, Egypt. The Jour. Amer. Sci. 2011, 7, 244–256. [Google Scholar]

- Zorriehzahra, M.J.; Delshad, S.T.; Adel, M.; Tiwari, R.; Karthik, K.; Dhama, K.; Lazado, C.C. Probiotics as beneficial microbes in aquaculture: an update on their multiple modes of action: A review. Vet. Quar. 2016, 36, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Singh, R. Probiotics in aquaculture: a promising emerging alternative approach. Symbiosis 2019, 77, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuebutornye, F.K.; Abarike, E.D.; Lu, Y. A review on the application of Bacillus as probiotics in aquaculture. Fish & Shellf. Immun 2019, 87, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farizky, H.S.; Satyantini, W.H.; Nindarwi, D.D. The efficacy of probiotic with different storage to decrease the total organic matter, ammonia, and total Vibrio on shrimp pond water. E&ES 2020, 441, 012108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsabagh, M.; Mohamed, R.; Moustafa, E.M.; Hamza, A.; Farrag, F.; Decamp, O.; Eltholth, M. Assessing the impact of Bacillus strains mixture probiotic on water quality, growth performance, blood profile and intestinal morphology of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Aquac. Nutr. 2018, 24, 1613–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.M.; Versalovic, J. Probiotics-host communication: modulation of signaling pathways in the intestine. Gut Mic. 2010, 1, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suez, J.; Zmora, N.; Segal, E.; Elinav, E. The pros, cons, and many unknowns of probiotics. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oelschlaeger, T.A. Mechanisms of probiotic actions–a review. Intern. Jour. Med. Micr. 2010, 300, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opiyo, M.A.; Jumbe, J.; Ngugi, C.C.; Charo-Karisa, H. Different levels of probiotics affect growth, survival and body composition of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) cultured in low input ponds. Sci. Afr. 2019, 4, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseinifar, S.H.; Sun, Y.Z.; Wang, A.; Zhou, Z. Probiotics as means of diseases control in aquaculture, a review of current knowledge and future perspectives. Front. Microb. 2018, 9, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.D.C.; Furlaneto, F.D.P.B.; Sussel, F.R.; Tachibana, L.; Gonçalves, G.S.; Ishikawa, C.M.; Ranzani-Paiva, M.J.T. Economic feasibility of probiotic use in the diet of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, during the reproductive period. Acta Scien., Ani. Sci. 2020, 42, 47960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.F.; Nyachoti, M. Using probiotics to improve swine gut health and nutrient utilization. Ani. Nut. 2017, 3, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, Y.S.; Yulvizar, C.; Mazhitov, B. Characterization of lactic acid bacteria from local cow’s milk kefir. IOP Conf. Ser.: Ear. Envir. Sci. 2018, 130, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, H.R.; do Nascimento, R.C.V.; Talma, S.V.; de Carvalho Furtado, M.; Balieiro, A.L.; Barbosa, J.B. Aplicações tecnológicas de Bactérias do Ácido Lático (BALs) em produtos lácteos. Ver. INGI-Ind. Geog. Inov. 2020, 4, 681–690. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, W.N. The living gut; Nottingham University Press: Nottingham, United Kingdom, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, K.D.; Del’Duca, A.; Borges, M.L.; Fernandes, R.T.; Cesar, D.E.; Apolônio, A.C.M. Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance in aquaculture: a classic method of protein precipitation for a new applicability. Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 2018, 40, e37881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Cao, J.; Wang, M.; Lu, M.; Chen, G.; Gao, F.; Yi, M. Effects of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis JCM5805 on colonization dynamics of gut microbiota and regulation of immunity in early ontogenetic stages of tilapia. Fish & Shellf. Immun. 2019, 86, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdan, A.M.; El-Sayed, A.F.M.; Mahmoud, M.M. Effects of a novel marine probiotic, Lactobacillus plantarum AH 78, on growth performance and immune response of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Jour. App. Microb. 2016, 120, 1061–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.H.; Ammar, M.A.M. Effect of some antimicrobials on quality and shelf life of freshwater tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Jour. Food Proc. Pres. 2020, 45, e15026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaktcham, P.M.; Piame, L.T.; Sileu, G.M.S.; Kouam, E.M.F.; Temgoua, J.B.; Ngoufack, F.Z.; de Lourdes Pérez-Chabela, M. Bacteriocinogenic Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis 3MT isolated from freshwater Nile Tilapia: isolation, safety traits, bacteriocin characterisation, and application for biopreservation in fish pâté. Arch. Microb. 2019, 201, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaktcham, P.M.; Kouam, E.M.F.; Tientcheu, M.L.T.; Temgoua, J.B.; Wacher, C.; Ngoufack, F.Z.; de Lourdes Perez-Chabela, M. Nisin-producing Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis 2MT isolated from freshwater Nile tilapia in Cameroon: Bacteriocin screening, characterization, and optimization in a low-cost medium. LWT 2019, 107, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfatah, E.N.; Mahboub, H.H.H. Studies on the effect of Lactococcus garvieae of dairy origin on both cheese and Nile tilapia (O. niloticus). Intern. Jour. Vet. Sci. Med. 2018, 6, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, J.Y.; Lim, Y.Y.; Ting, A.S.Y. Bacteriocin-like substances produced by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis CF4MRS isolated from fish intestine: Antimicrobial activities and inhibitory properties. Inter. Food Res. Jour. 2017, 24, 394. [Google Scholar]

- Tasaku, S.; Siripornadulsil, S.; Siripornadulsil, W. Inhibitory activity of food-originated Pediococcus pentosaceus NP6 against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in Nile tilapia by-products. Chi. Mai Jour. Sci. 2017, 44, 383–393. [Google Scholar]

- Etyemez, M.; Balcazar, J.L. Isolation and characterization of bacteria with antibacterial properties from Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Res. Vet. Sci. 2016, 105, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Yao, J.; Li, W. Inhibition ability of probiotic, Lactococcus lactis, against A. hydrophila and study of its immunostimulatory effect in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Inter. Jour. Eng. Sci. Tech. 2010, 2, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Production in 2018 (milliontons) | Installations | Integration with other economic activities | Other technologies | Reference |

| China | 1.86 | Floating cage (high-density), net, ponds (in hydroelectric reservoirs) | Polyculture with carp, mullet or shrimp; rice culture | Hydroponics, GIFTs and ProGIFT*, RAS (Recirculating systems), hatcheries | [17,20,21,24] |

| Indonesia | 1.25 | Floating net cage, two-net cage | Polyculture with carp; rice culture | Biofloc technology, RAS, GIFT and other genetic improved tilapias, nanobubble technology, dual-cage | [17,20] |

| Egypt | 0.86 | Pond-farm, tank, earthen-ponds | Polyculture with mullet; rice culture | RAS, In-Pond Raceway System (IPRS), dual-cage, aquaponics, hatcheries, improved-feeds, GIFT and GIANT*, seed production, Automated Monitoring and Control System (AMCS) | [17,20] |

| Brazil | 0.40 | Earthen-ponds, tank-net, cages (in hydroelectric reservoirs, high-density), periphyton pond | Polyculture with pirapitinga or shrimp | Aerator, automatic feeding, Biofloc technology, GIFTs and GST | [17,20,46,121] |

| Philippines | 0.33 |

Earthen-ponds, floating cages and fixed cages, tank | Most farmers adopt monoculture system; however, there is integration with swine, rabbit and poultry cultures in lesser extent | GIFT and other genetic improved tilapias, monosex tilapia, supermale technology, Biofloc technology | [12,17,20] |

| Thailand | 0.32 | Floating-cages (high-density), Bamboo cages | Integration with poultry culture; rice culture | GIFT and other genetic improved tilapias, supermale technology, improved seaweed | [17,20] |

| Bangladesh | 0.22 | Pond-dike, cages | Polyculture with carp, rice culture (rotational) | GIFT, feed supplements, improved seeds, water-saving technologies | [17,20] |

| Vietnam | 0.20 | Cages, net | Polyculture with silver barb and carp or shrimp, rice culture | RAS, GIFT | [17,20] |

| Colombia | 0.077 | Cages (in hydroelectric reservoirs, high-density), pond, tanks, raceways | Polyculture with carp or bocachico | Improved seeds, Biofloc technology | [2,17] |

| Uganda | 0.070 | Earthen-ponds, Cages (low-density), cage/pens, tank/raceways | Most farmers adopt monoculture system; however there is integration between farming/aquaculture activities | Hatcheries, improved seeds | [2,17] |

| Taiwan | 0.062 | Cages, octogonal tanks/raceway ponds | Polyculture with shrimp | Aerator, automatic feeders, RAS | [2,17] |

| Mexico | 0.052 | Net-pens, cages | Polyculture with Mayan cichlids shrimp or prawn | RAS, Biofloc technology | [2,17] |

| China | 1.86 | Floating cage (high-density), net, ponds (in hydroelectric reservoirs) | Polyculture with carp, mullet or shrimp; rice culture | Hydroponics, GIFTs and ProGIFT*, RAS (Recirculating systems), hatcheries | [17,20,21,24] |

| Resistant Pathogen | Ineffective antibiotic (resistance) | Tilapia origin | Reference | Most common antibiotics detected in the country | Reference | Antibiotic allowed in the country (active principle) | Reference |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Ampicillin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, tetracycline and nalidixic acid | Giza (Egypt) | [123] | Ciprofloxacin and florfenicol | [117] | Florfenicol, ciprofloxacin | [117] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, and Streptococcus agalactiae | Penicillin, ampicillin, oxytetracyclines, trimethoprim, oxolinic acid, gentamicin, and sulfamethoxazole | Bangkok and Nakhon Si Thammarat (Thailand) | [124,125] | Enrofloxacin, norfloxacin, amoxicillin, oxolinic acid, penicillin, florfenicol, tetracycline, oxytetracycline, sulfadiazine, trimethoprim, ormetoprim, sulfadiazine + trimethoprim, sulfadimethoxine + trimethoprim, sulfaguanidine | [117,118] | Oxytetracycline, tetracycline, sulfadimethozine, trimethoprim, sulfadimethoxine-ormethoprim and amoxicillin | [117] |

| Vibrio spp. | Erythromycin and chloramphenicol | Sri Tujuh (Malaysia) | [126] | Oxolinic acid, virginiamycin, chloramphenicol and sulfonamides, tetracyclines, nitrofurans* | [117,118] | Amoxicillin, oxytetracycline, flumequine and florfenicol, oxolinic acid, virginiamycin and tetracyclines | [117,118] |

| Enterococcus spp. | Tetracycline | Chennai (India) | [120] | Erythromycin, chloramphenicol, sulfadiazine, sulfadimethoxine, sulfamethazine, sulfapyridine, sulfamethoxypyridazine, sulfadoxine, sulfamethoxazole, sulfanilamide, sulfathiazole | [117] | Sulfadimethoxin, sulfabromomethazin, erythromycin, oxytetracycline, althrocin, ampicillin, sparfloxacin, and enrofloxacin and sulfaethoxypyridazine | [117,120] |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | Tetracycline, sulfathiazole | Solteira Island (Brazil) | [122] | Florfenicol, tetracycline, oxytetracycline and enrofloxacin** | [117] | Florfenicol, oxytetracycline and neomycin (ornamental fish) | [20,119,121,122] |

| Acinetobacter spp. | Sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline | Tianjin (China) | [127] | Neomycin sulphate, doxycycline hydrochloride, thiamphenicol, florfenicol, sulfadiazine, sulfamethoxazole + trimethoprim, sodium sulfamonomethoxine, enrofloxacin, flumequine, oxolinic acid, oxytetracycline, ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, ofloxacin, amoxicillin, cephalexin, cefradine, cefotaxime, erythromycin, gentamicin S, neomycin, tetracycline, lycomicin, sulfamethoxazole*** | [117,119] | Neomycin sulfate, doxycycline hydrochloride, thiamphenicol, florfenicol, sulfadiazine, sulfamethoxazole + trimethropim, sodium sulfamonomethoxin, enrofloxacin, flumequine, oxolinic acid, oxytetracycline |

[119] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Ampicillin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, tetracycline and nalidixic acid | Giza (Egypt) | [123] | Ciprofloxacin and florfenicol | [117] | Florfenicol, ciprofloxacin | [117] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, and Streptococcus agalactiae | Penicillin, ampicillin, oxytetracyclines, trimethoprim, oxolinic acid, gentamicin, and sulfamethoxazole | Bangkok and Nakhon Si Thammarat (Thailand) | [124,125] | Enrofloxacin, norfloxacin, amoxicillin, oxolinic acid, penicillin, florfenicol, tetracycline, oxytetracycline, sulfadiazine, trimethoprim, ormetoprim, sulfadiazine + trimethoprim, sulfadimethoxine + trimethoprim, sulfaguanidine | [117,119] | Oxytetracycline, tetracycline, sulfadimethozine, trimethoprim, sulfadimethoxine-ormethoprim and amoxicillin | [117] |

| Vibrio spp. | Erythromycin and chloramphenicol | Sri Tujuh (Malaysia) | [126] | Oxolinic acid, virginiamycin, chloramphenicol and sulfonamides, tetracyclines, nitrofurans* | [117,119] | Amoxicillin, oxytetracycline, flumequine and florfenicol, oxolinic acid, virginiamycin and tetracyclines | [117,119] |

| Tilapia species | Probiotic | Concentration | Duration | Secreted enzyme | Results | Reference |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Aspergillus oryzae | 106 and 108 CFU/g | 60 days | PR, AP, LY, SD and CA (Results obtained under hypoxia) |

IR, AA, PP, FCR, GR ↑; BC, SR, AN←; CH, PC, ROS↓ | [139] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Rummeliibacillus stabekisii | 107 CFU/g | 7 days | PR, CE, AM and XY | GR, FE, WG ↑ | [140] |

| Oreochromis spp. | Lactobacillus plantarum, Bacillus velezensis | 108 CFU/g- Lb. plantarum 107 CFU/g- B. velezensis |

15 and 30 days | PE and LY | IR, GR, DR ↑ | [141] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus spp. | 107 CFU/g | 14 days | LY, SD, CA, MPO and AP | WG, GR, IR, DR, FCR, PP↑ | [142] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Lactobacillus plantarum (KC426951) | 105 and 107 CFU/g | 14 and 28 days | ALP, MPO and LY | WG, GR, IR, DR, FCR, PP, ROS↑ | [143] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | 104 and 106 CFU/g | 56 days | LY | IR, DR, PP ↑ | [144] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus subtilis V1TNJ1 | Not specified | Not specified | PR | PI ↑ | [145] |

| Tilapia species | Probiotic | Concentration | Pathogen | Duration | Results | Reference |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Enterococcus faecium | 1010 CFU/g | Aeromonas hydrophila | 84 days (CON); 7 days (P7); 14 days (P14) | SR, HE, HM, PG, PC, MO (regardless of the period) →; PP (CON)↑; GR, WG (P7) ↑; RB (P14) ← | [146] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Enterococcus avium | 107, 108, 109 and 1010 CFU/g | Streptococcus agalactiae | 7, 14 and 21 days | SR, AM, PR, LA ↑ (107 CFU/g during 7 days) | [147] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Lactobacillus plantarum | 1.02 × 109 CFU/mL/kg | Enterococcus faecalis | 56 days | GR →; IR (innate), DR, IG (cytokines), SR↑; MO↓; BC← | [15] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus spp. | 107 and 108 CFU/g | Aeromonas hydrophila, Micrococcus luteus, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus agalactiae | 14 days | SR↑ DE← | [148] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Aspergillus oryzae | 106 and 108 CFU/g | Aeromonas hydrophila | 60 days | FCR, GR, GLx, IR (immunoglobulin M), SR, LY, PP, TP, PA, CA↑; AN←; PG, CH↓ | [139] |

| Hybrid tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus x Oreochromis aureus) | Clostridium butyricum | 1.50 × 108 CFU/g | Aeromonas hydrophila | 56 days | PRE, LR, ADC, VH, GR, FCR↑; BC←; MO↓ | [149] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus subtilis and Lactobacillus plantarum | 1.51 × 106 CFU/g for Lb. plantarum 1.34 × 107 CFU/g for B. subtilis |

Aeromonas hydrophila | 28 days | GR, SR, IG →; BC← | [150] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus cereus NY5 and Bacillus subtilis | 108 CFU/g | Streptococcus agalactiae | 42 days | WG, FCR, SR→ (only B. subtilis); FCR↑ (B. cereus alone, and B. cereus + B. subtilis); DR, LY, ML, MD↑; BC← | [151] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Rummeliibacillus stabekisii | 107 CFU/g | Streptococcus iniae and Aeromonas hydrophila | 56 days | WG, FCR, GR, FE, DE, SR, DR, IR, IG (cytokines)↑; PA, RB, LY← | [140] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis JCM5805 | 104 CFU/mL (T1) and 108 CFU/mL (T2) | Streptococcus agalactiae | 15 days | DR, GR, IG, SR↑ (only in T2); BC ← | [151] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Lactobacillus plantarum CR1T5 | 108 CFU/g | Streptococcus agalactiae | 84 days | WG, GR, FCR, PA, PE, RB, LY, IR↑; SM←; SR→ | [152] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Paenibacillus ehimensis NPUST1 | 106 and 107 CFU/g | Streptococcus iniae and Aeromonas hydrophila | 70 days | WG, FCR, FE, PA, RB, SD, LY, IG (TNF-α and IL-1β), PY, LA, AM, PR↑ | [153] |

| Oreochromis spp. | Lactobacillus rhamnosus | 108 CFU/g | Aeromonas veronii | 30 days | GR, FCR, LY, WG, CH, PG, VH, VW, GC, AB, MP↑; AL, TR, AST→; ALT, BUN, MO↓ | [154] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Lactococcus lactis | Not specified | Staphylococcus spp., Vibrio spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Not specified | AN ← | [155] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Lactococcus coryniformis subsp. torquens MTi1 and MTi2 | 1.50 × 108 CFU/mL | Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhi, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus | Not specified | AN← | [156] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus spp. | 107 CFU/g | Streptococcus agalactiae | 30 days | GR, WG, LY, PR, CA, SD, ALP, MPO, ROS, GC, PP↑; IR, IG ← MO↓ | [142] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus licheniformis | 105 and 107 CFU/g | Aeromonas hydrophila | 14 or 28 days | GR, WG, FCR, IR, DR, ROS↑; ALP, LY← | [143] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus subtilis | 3.9 × 107 CFU per fish | Aeromonas hydrophila | 56 days | WG, GR, FCR, LY, RB→; SR, PP↑; MO↓ (even lower when probiotic was combined with Previda® prebiotic) | [94] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus subtilis | 4 x 107 CFU/g | Streptococcus iniae | 21 days | GR→; AN, LY↑; MO↓ | [157] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Lactobacillus plantarum AH78 | 1010 CFU/mL | Aeromonas hydrophila | 40 days | GR, IR, FCR, AL, GLx↑; IG (cytokines), VH, BC, ABA, ← | [126] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus pumilus | Not specified | Cetobacterium spp. and Plesiomonas spp. | 49 days | GR, FCR, LY, GC, WG, ABA, VH↑ | [158] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | 104 and 106 CFU/g | Yersinia ruckeri and Clostridium perfringens | 30 days | LY, NO, PA, IR, DR, IG, PP (at higher concentration) ↑ | [144] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | 104 and 106 CFU/g | Not evaluated | 30 and 60 days | WG, GR (after 60 days), SR, GC; GB, AL, TP (at higher concentration) ↑VH, BC← | [159] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus licheniformis | 4.4 × 106 CFU/g | Streptococcus iniae | 70 days | WG, GR, DR↑; LY, ML←; FCR, SD, SR→ | [160] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Streptococcus thermophilus | Not specified | Aeromonas hydrophila | 98 days | GR, DR, AL, GC, FCR↑; MO↓; ALT, AL, GB, SR→; AST← | [161] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus subtilis | 5 × 106 CFU/g | Not evaluated | 84 days | GR, PC, PG→; LY, PA, HE↑; HM↓; IR← | [162] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Bacillus subtilis | 0.1 g/mL (in water), 0.2 g/mL (in diet) | Flavobacterium columnare | 60 days | MO↓; WQ→; DR↑ | [163] |

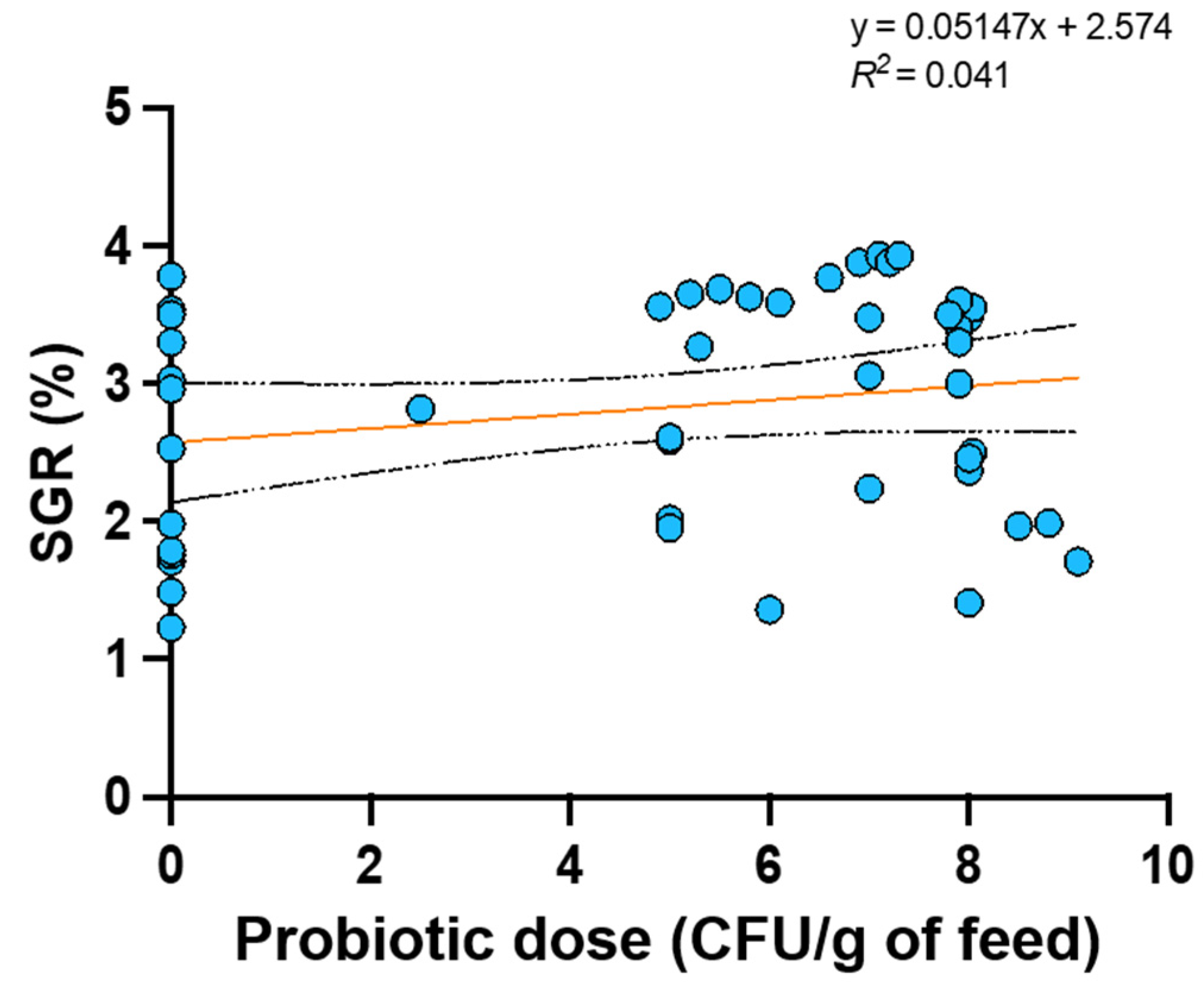

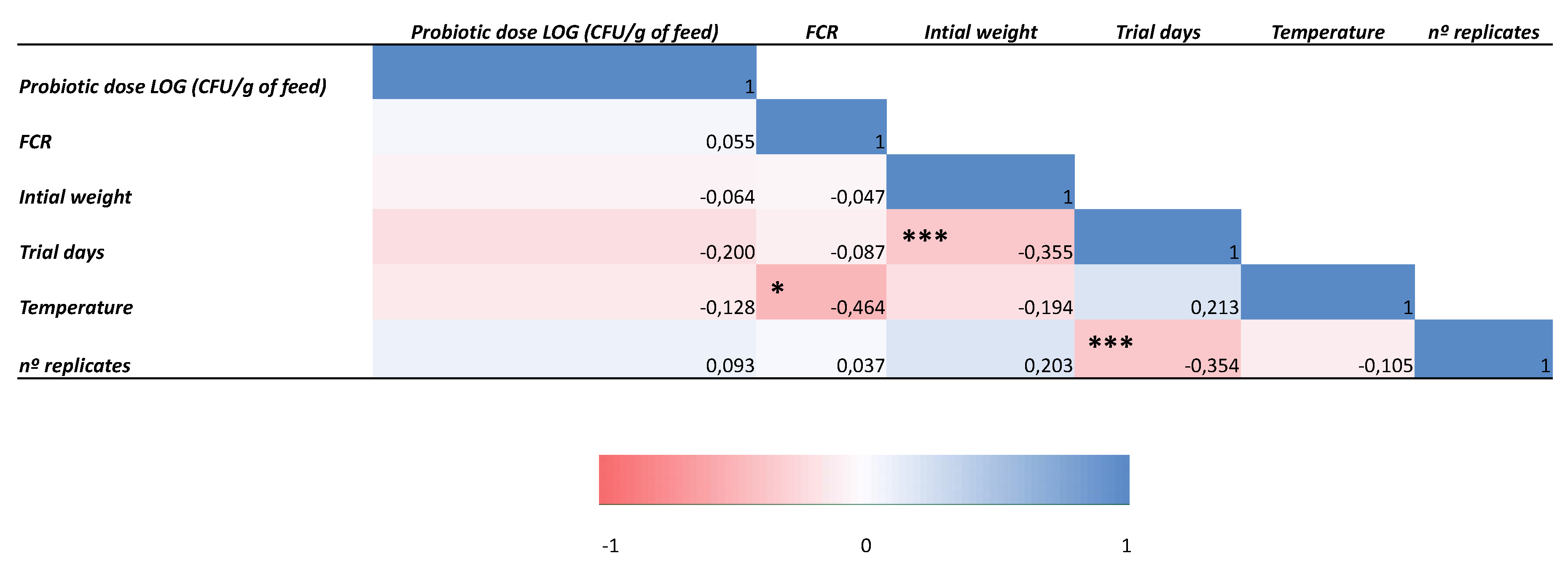

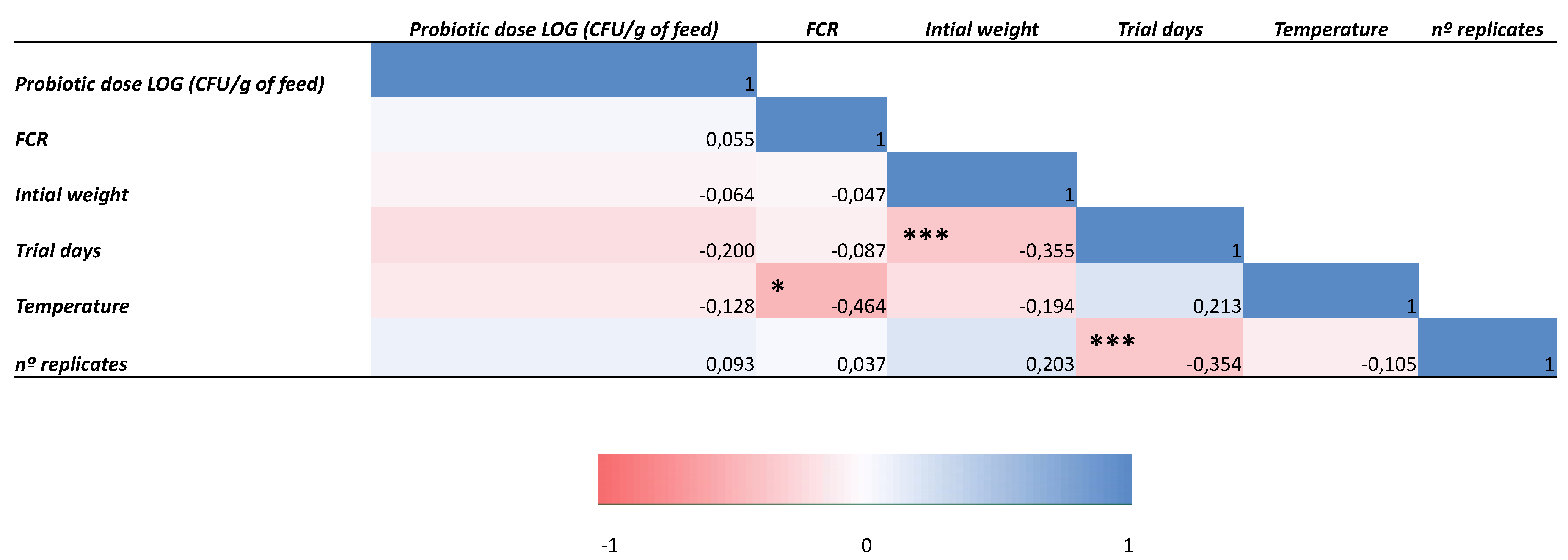

| Model | Predictors | R2 | ∆R2 | ∆F | p-value |

| 1 | Number of replicates, initial weight, temperature and test duration. | 0.354 | 0.354 | 5.063 | 0.002 |

| 2 | Number of replicates, initial weight, temperature, test duration and probiotic dose in feed | 0.377 | 0.023 | 1.319 | 0.258 |

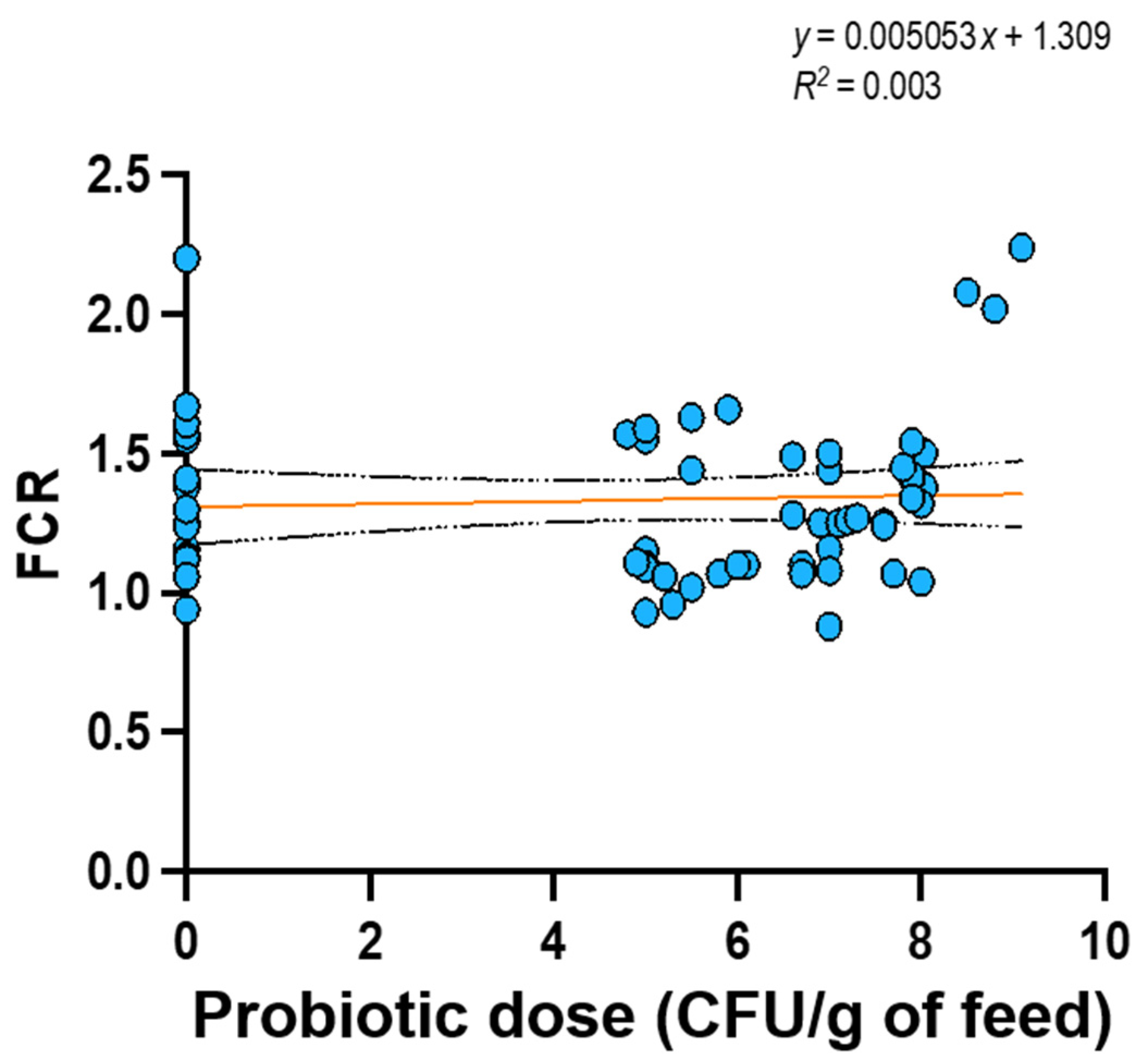

| Model | Predictors | R2 | ∆R2 | ∆F | p-value |

| 1 | Number of replicates, initial weight, temperature and test duration. | 0.279 | 0.279 | 5.036 | 0.002 |

| 2 | Number of replicates, initial weight, temperature, test duration and probiotic dose in feed | 0.279 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.905 |

|

Tilapia Species |

Bacteriocin or BLIS | Pathogen | Research mode | Results | Reference |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Nisin | Enterobacteriaceae | In vitro study, the capacity of preserving tilapia meat was evaluated | Biopreservation effect, bacteriocin did not affect sensory properties of the product, there was no biogenic amine production. | [182] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | BLIS produced by Paenibacillus ehimensis NPUST1 | Streptococcus iniae and Aeromonas hydrophila | In vivo study, administration of probiotics with BLIS production | Low pH tolerance, high thermal tolerance, broad spectrum, BLIS had antibacterial activity and improved fish immunity | [153] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | BLIS produced by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis 3MT | Vibrio spp. | In vitro study, evaluation of the biopreservation capacity of bacteriocin isolated from tilapia in fish pâté | Stable to heat and pH, antibacterial properties, free of virulence, no production of biogenic amines | [183] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Nisin Z | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 | In vitro study, screening for bacteriocin production in LAB isolates and identification | High stability to heat, resistance to pH variations, detergents and NaCl, wide range of antibacterial activity | [184] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | BLIS produced by Bacillus spp. | Aeromonas hydrophila, Salmonella typhi | In vitro study, purification and evaluation of antibacterial capacity of BLIS extracted from tilapia gut | BLIS was not resistant to acid treatment and denatured in ammonium sulfate (20% of saturation), antibacterial activity against both tested pathogens. | [179] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | BLIS produced by Lactococcus garvieae | Staphylococcus aureus | In vivo study, administration of probiotics with BLIS production | BLIS showed moderate zones of inhibition against closed related species; fish that received bacteriocinogenic probiotics were protected against pathogens and had improved immune response. | [185] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | BLIS produced by Lactococcus coryniformis subsp. torquens MTi1 and MTi2 | Escherichia coli | In vitro study, purification and evaluation of antibacterial capacity of BLIS extracted from tilapia gut | BLIS exhibited antibacterial activity, but when submitted to enzyme treatment, the inhibitory properties were inactivated, according to the protein nature of these compounds | [156] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | BLIS produced by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis CF4MRS | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Aeromonas hydrophila, Edwardsiella tarda and Serratia marcescens | In vitro study, purification and evaluation of antibacterial activity of BLIS extracted from tilapia intestine | BLIS concentration was too low to significantly inhibit the pathogens | [186] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Supernatant produced by Pediococcus pentosaceus NP6 | Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium | In vitro study, capacity of preserving tilapia by-products | Supernatant exhibited antibacterial activity; partial purification indicates that it may be a bacteriocin | [187] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | BLIS produced by Bacillus endophyticus, Bacillus flexus, Bacillus mojavensis, Bacillus sonorensis and Bacillus subtilis | Streptococcus iniae | In vivo study, administration of probiotics with BLIS production | BLIS exhibited antibacterial activity; the enzyme treatment suggested that the inhibitory substance may be a bacteriocin | [188] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | BLIS produced by Lactococcus lactis RQ516 | Aeromonas hydrophila | In vivo study, administration of probiotics with BLIS production | Immunostimulant effect and antibacterial activity against a wide spectrum of bacteria, including A. hydrophila. | [189] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Nisin | Enterobacteriaceae | In vitro study, capacity of preserving tilapia meat | Biopreservation effect, the bacteriocin did not affect sensory properties of the product, there was no biogenic amine production. | [182] |

| Oreochromis niloticus | BLIS produced by Paenibacillus ehimensis NPUST1 | Streptococcus iniae and Aeromonas hydrophila | In vivo study, administration of probiotics with BLIS production | Low pH tolerance, high thermal tolerance, broad spectrum, BLIS had antibacterial activity and improved fish immunity | [153] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).