Submitted:

01 November 2023

Posted:

03 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Aims and objectives

- What constitutes the concept of child-centred care in healthcare?

- How has the concept of child-centred care developed?

- What is the applicability of child-centred care and what are its limitations?

- How does the concept of child-centred care benefit and inform children’s healthcare?

2. Methods

Inclusion criteria

Search strategy

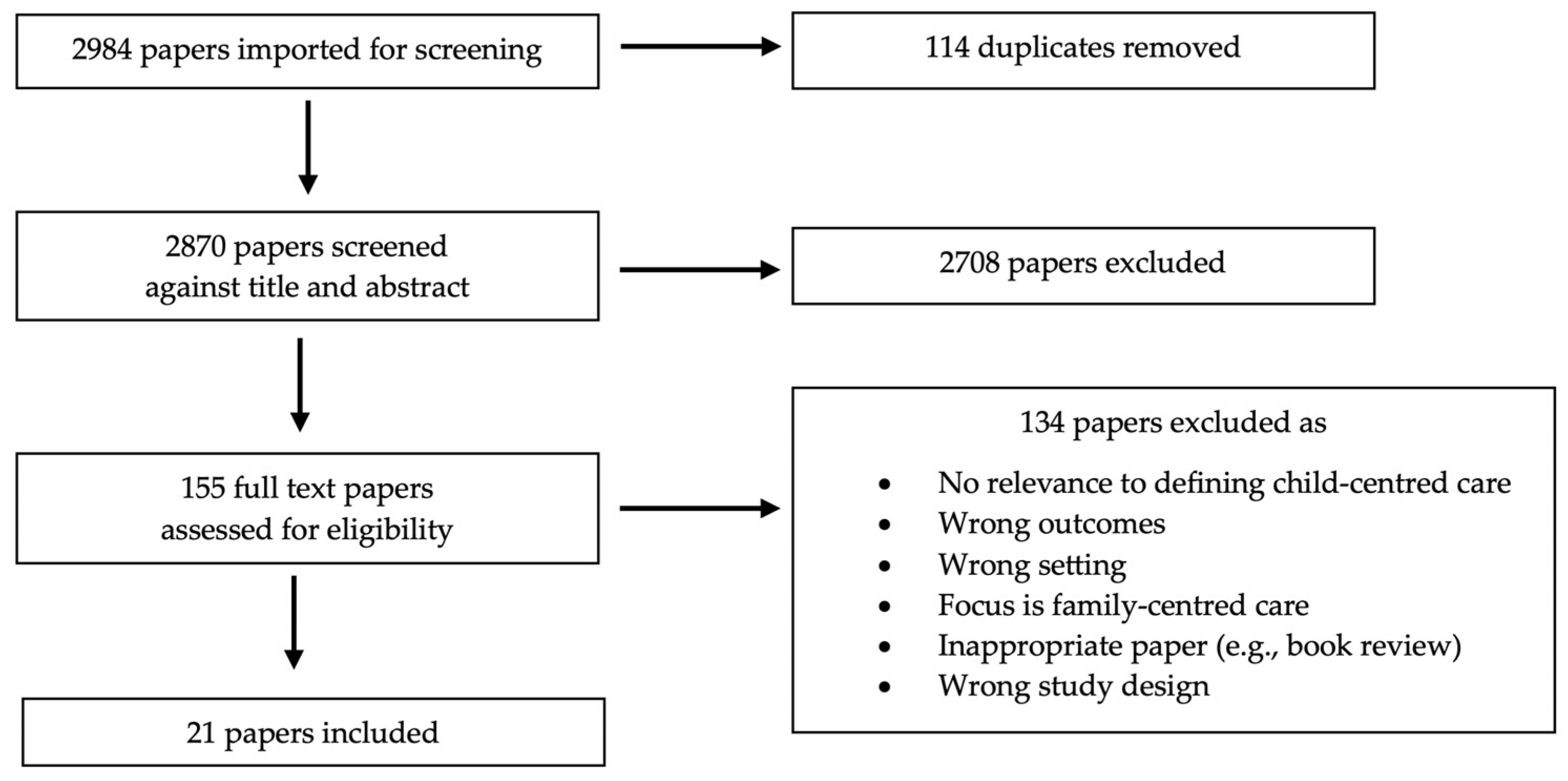

Screening and eligibility

- The focus of the paper was adequately on child-centred care and not FCC;

- There was sufficient content relevant to defining child-centred care on a practical or conceptual level, including papers who may not have used the term child-centered care but whose content was relevant to the germinal concept of child-centred care; and

- The outcomes and setting were relevant to this scoping review.

Data extraction and charting

3. Results

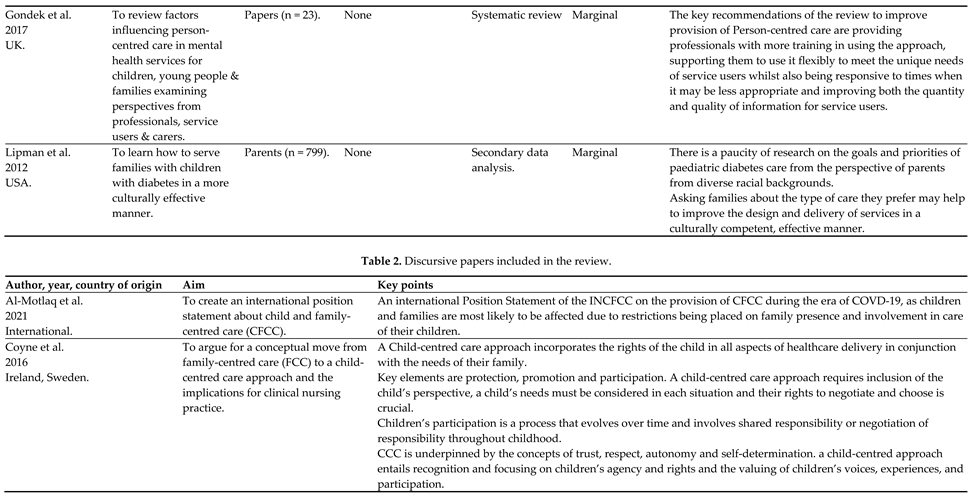

Demographics of included papers

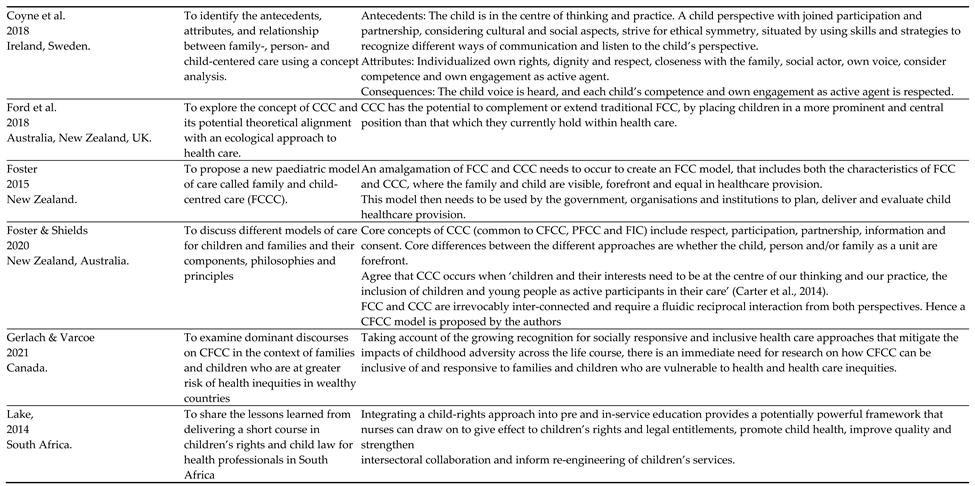

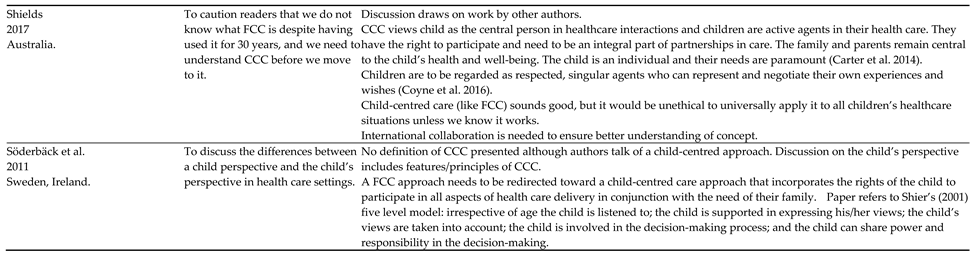

Overview of discursive papers

Dates of publication

Authorship

Discursive focus

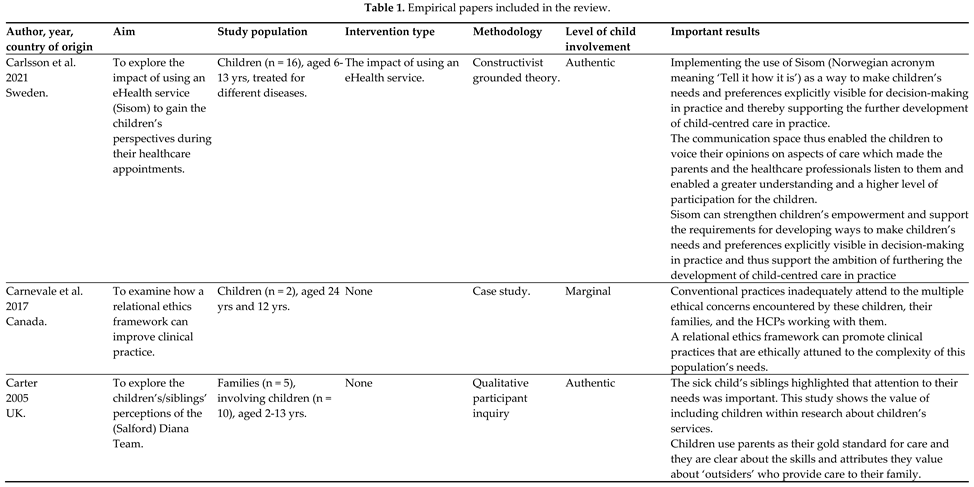

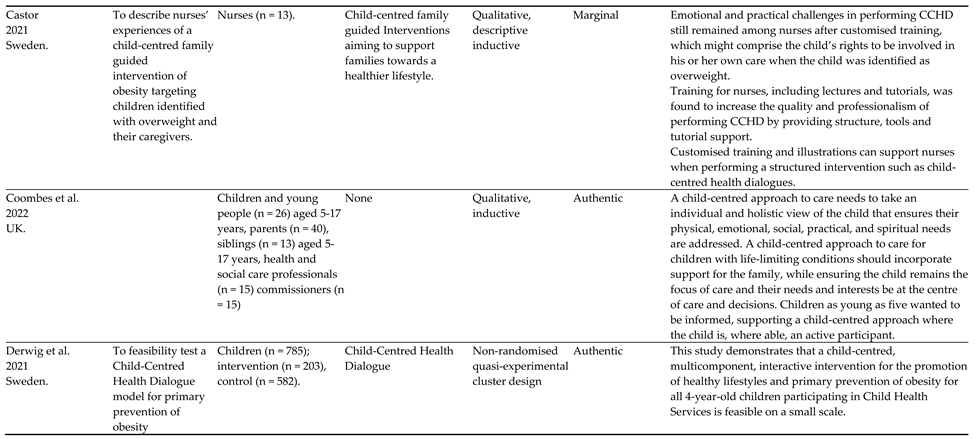

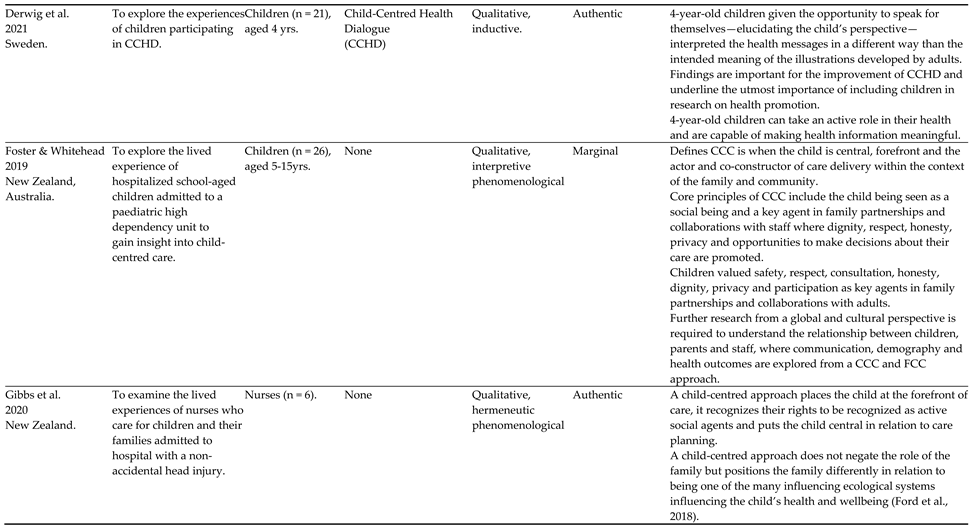

Overview of empirical papers

Dates of publication

Countries data generated from

Study design

Level of child involvement

Sample size and characteristics

Themes

Agency

Participation

Decision making

Communication

Impact

4. Discussion

What constitutes the concept of child-centred care in healthcare?

How has the concept of child-centred care developed?

What is the applicability of child-centred care and what are its limitations?

How does the concept of child-centred care benefit and inform children’s healthcare?

Strengths and limitations of the review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ford, K.; Dickinson, A.; Water, T.; Campbell, S.; Bray, L.; Carter, B. Child Centred Care: Challenging Assumptions and Repositioning Children and Young People. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2018, 43, e39–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B.; Bray, L.; Dickinson, A.; Edwards, M.; Ford, K. Child-centred nursing: promoting critical thinking.; Sage Publications: London, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, I.; Hallström, I.; Söderbäck, M. Reframing the focus from a family-centred to a child-centred care approach for children's healthcare. Journal of child health care: for professionals working with children in the hospital and community 2016, 20, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, I.; Holmström, I.; Söderbäck, M. Centeredness in Healthcare: A Concept Synthesis of Family-centered Care, Person-centered Care and Child-centered Care. Journal of pediatric nursing 2018, 42, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, E.; Merkur, S.; Anell, A. Person-centredness: exploring its evolution and meaning in the health system context. In Achieving Person-Centred Health Systems., Nolte, E., Merkur, S., Anell, A., Eds. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2020; pp. 19-40.

- Ahmann, E. Family-centered care: shifting orientation. Pediatric nursing 1994, 20, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Ministry of Health. The Welfare of Children in Hospital. Report of the Committee (The Platt Report).

- Shields, L. What is ‘family-centred care’? European Journal for Person Centered Healthcare 2015, 3, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B.; Ford, K. Researching children's health experiences: The place for participatory, child-centered, arts-based approaches. Research in Nursing & Health 2013, 36, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, L.; Snodin, J.; Carter, B. Holding and restraining children for clinical procedures within an acute care setting: an ethical consideration of the evidence. Nursing Inquiry 2015, 22, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 11. United Nations. UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989.

- James, A.; Jenks, C.; Prout, A. Theorizing childhood; Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Franck, L.S.; Callery, P. Re-thinking family-centred care across the continuum of childrens healthcare. Child: Care, Health and Development 2004, 30, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M.; Blamires, J.; Moir, C.; Jones, V.; Shrestha-Ranjit, J.; Fenton, B.; Dickinson, A. Children and young people's participation in decision-making within healthcare organisations in New Zealand: An integrative review. J Child Health Care, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, L. All is not well with family-centred care. Nursing Children and Young People 2017, 29, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderbäck, M.; Coyne, I.; Harder, M. The importance of including both a child perspective and the child’s perspective within health care settings to provide truly child-centred care. Journal of Child Health Care 2011, 15, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, K.; Campbell, S.; Carter, B.; Earwaker, L. The concept of child-centered care in healthcare: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports 2018, 16, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P.; The, P.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. 2015.

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O'Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O'Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Motlaq, M.; Neill, S.; Foster, M.J.; Coyne, I.; Houghton, D.; Angelhoff, C.; Rising-Holmström, M.; Majamanda, M. Position Statement of the International Network for Child and Family Centered Care: Child and Family Centred Care during the COVID19 Pandemic. Journal of pediatric nursing 2021, 61, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M. A new model: the family and child centered care model. Nursing praxis in New Zealand 2015, 31, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, M.; Shields, L. Bridging the Child and Family Centered Care Gap: Therapeutic Conversations with Children and Families. Comprehensive child and adolescent nursing 2020, 43, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, A.; Varcoe, C. Orienting child- and family-centered care toward equity. Journal of child health care: for professionals working with children in the hospital and community 2021, 25, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, L. Children's rights education: An imperative for health professionals. Curationis 2014, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, I.-M.; Arvidsson, S.; Svedberg, P.; Nygren, J.M.; Viklund, Å.; Birkeland, A.-L.; Larsson, I. Creating a communication space in the healthcare context: Children’s perspective of using the eHealth service, Sisom. Journal of Child Health Care 2021, 25, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, F.A.P.; Teachman, G.; Bogossian, A. A Relational Ethics Framework for Advancing Practice with Children with Complex Health Care Needs and Their Parents. Comprehensive child and adolescent nursing 2017, 40, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B. “They’ve got to be as good as mum and dad”: Children with complex health care needs and their siblings’ perceptions of a Diana community nursing service. Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing 2005, 9, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castor, C.; Derwig, M.; Borg, S.J.; Ollhage, M.E.; Tiberg, I. A challenging balancing act to engage children and their families in a healthy lifestyle - Nurses' experiences of child-centred health dialogue in child health services in Sweden. Journal of clinical nursing 2021, 30, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombes, L.; Braybrook, D.; Roach, A.; Scott, H.; Harðardóttir, D.; Bristowe, K.; Ellis-Smith, C.; Bluebond-Langner, M.; Fraser, L.K.; Downing, J.; et al. Achieving child-centred care for children and young people with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions—a qualitative interview study. European Journal of Pediatrics 2022, 181, 3739–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derwig, M.; Tiberg, I.; Björk, J.; Hallström, I. Child-Centred Health Dialogue for primary prevention of obesity in Child Health Services – a feasibility study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 2021, 49, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derwig, M.; Tiberg, I.; Hallström, I. Elucidating the child's perspective in health promotion: children's experiences of child-centred health dialogue in Sweden. Health promotion international 2021, 36, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, M.; Whitehead, L. Using drawings to understand the child's experience of child-centred care on admission to a paediatric high dependency unit. Journal of child health care: for professionals working with children in the hospital and community 2019, 23, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, K.A.; Dickinson, A.; Rasmussen, S. Caring for Children with Non-Accidental Head Injuries: A Case for a Child-Centered Approach. Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing 2020, 43, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondek, D.; Edbrooke-Childs, J.; Velikonja, T.; Chapman, L.; Saunders, F.; Hayes, D.; Wolpert, M. Facilitators and Barriers to Person-centred Care in Child and Young People Mental Health Services: A Systematic Review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 2017, 24, 870–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipman, T.H.; Murphy, K.M.; Kumanyika, S.K.; Ratcliffe, S.J.; Jawad, A.F.; Ginsburg, K.R. Racial differences in parents' perceptions of factors important for children to live well with diabetes. The Diabetes educator 2012, 38, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodén, L. On, to, with, for, by: ethics and children in research. Children's Geographies, 1080; -16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, T. Reconceptualising Children’s Agency as Continuum and Interdependence. Social Sciences 2019, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkins, C.; Satchwell, C. Learning How to Know Together: Using Barthes and Aristotle to Turn From ‘Training’ to ‘Collaborative Learning’ in Participatory Research with Children and Young People. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231164607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkins, C. Deeping the roots of children’s participation. Sociedad e Infancias 2023, 7, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montreuil, M.; Carnevale, F.A. A concept analysis of children's agency within the health literature. J Child Health Care 2016, 20, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijngaarde, R.O.; Hein, I.; Daams, J.; Van Goudoever, J.B.; Ubbink, D.T. Chronically ill children's participation and health outcomes in shared decision-making: a scoping review. Eur J Pediatr 2021, 180, 2345–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedding, C.; Reis, R.; Wolf, B.; Hardon, A. Revealing the hidden agency of children in a clinical setting. Health Expectations 2015, 18, 2121–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaye, A.A.; Coyne, I.; Söderbäck, M.; Hallström, I.K. Children's active participation in decision-making processes during hospitalisation: An observational study. J Clin Nurs 2019, 28, 4525–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, I.; Staland-Nyman, C.; Svedberg, P.; Nygren, J.M.; Carlsson, I.-M. Children and young people’s participation in developing interventions in health and well-being: a scoping review. BMC Health Services Research 2018, 18, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, B.Q.; Mendoza, M.M.; Saini, S.K.; Sweeny, K. Let the Kid Speak: Dynamics of Triadic Medical Interactions Involving Pediatric Patients. Health Commun 2023, 38, 1762–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Woerden, C.S.; Vroman, H.; Brand, P.L.P. Child participation in triadic medical consultations: A scoping review and summary of promotive interventions. Patient Educ Couns 2023, 113, 107749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoecklin, D. Theories of action in the field of child participation: In search of explicit frameworks. Childhood 2013, 20, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, G.; Conn, R.; Kelly, M.A.; Thompson, A.; Dornan, T. Fifteen-minute consultation: Guide to communicating with children and young people. Archives of disease in childhood - Education & Practice Edition 2023, 108, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navein, A.; McTaggart, J.; Hodgson, X.; Shaw, J.; Hargreaves, D.; Gonzalez-Viana, E.; Mehmeti, A. Effective healthcare communication with children and young people: a systematic review of barriers and facilitators. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2022, 107, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thunberg, G.; Johnson, E.; Bornman, J.; Öhlén, J.; Nilsson, S. Being heard – Supporting person-centred communication in paediatric care using augmentative and alternative communication as universal design: A position paper. Nursing Inquiry 2022, 29, e12426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutman, T.; Hanson, C.S.; Bernays, S.; Craig, J.C.; Sinha, A.; Dart, A.; Eddy, A.A.; Gipson, D.S.; Bockenhauer, D.; Yap, H.K.; et al. Child and Parental Perspectives on Communication and Decision Making in Pediatric CKD: A Focus Group Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2018, 72, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.; Condren, M. Communication Strategies for Empowering and Protecting Children. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 2016, 21, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RCPCH. Engaging children and young people - improving communication. Availabe online: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/engaging-children-young-people/communication (accessed on 25th August).

- Boland, L.; Graham, I.D.; Légaré, F.; Lewis, K.; Jull, J.; Shephard, A.; Lawson, M.L.; Davis, A.; Yameogo, A.; Stacey, D. Barriers and facilitators of pediatric shared decision-making: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2019, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, L.; Munns, A.; Taylor, M.; Priddis, L.; Park, J.; Douglas, T. Scoping review of the literature about family-centred care with caregivers of children with cystic fibrosis. Neonatal, Paediatric & Child Health Nursing 2013, 16, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, L.; Pratt, J.; Hunter, J. Family centred care: a review of qualitative studies. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2006, 15, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janerka, C.; Leslie, G.D.; Gill, F.J. Development of patient-centred care in acute hospital settings: A meta-narrative review. Int J Nurs Stud 2023, 140, 104465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.M.; Braybrook, D.; Harðardóttir, D.; Ellis-Smith, C.; Harding, R. Implementation of child-centred outcome measures in routine paediatric healthcare practice: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2023, 21, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosengren, K.S.; Kirkorian, H.; Choi, K.; Jiang, M.J.; Raimer, C.; Tolkin, E.; Sartin-Tarm, A. Attempting to break the fourth wall: Young children's action errors with screen media. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2021, 3, 468–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson Eklund, J.; Holmström, I.K.; Kumlin, T.; Kaminsky, E.; Skoglund, K.; Höglander, J.; Sundler, A.J.; Condén, E.; Summer Meranius, M. “Same same or different?” A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Education and Counseling 2019, 102, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossiter, C.; Levett-Jones, T.; Pich, J. The impact of person-centred care on patient safety: An umbrella review of systematic reviews. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2020, 109, 103658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).