1. Methods for assessing the correction of the cervical-chin area.

The initial assessment of the face begins with a visual examination, taking into account the underlying bone structure and the unique characteristics of the soft tissues. While bone tissue is relatively stable, it undergoes age-related changes such as loss of density and volume, which can be addressed through implants or soft tissue fillers. However, achieving facial rejuvenation primarily involves targeting the soft tissues. In modern medicine, various technological methods are utilized, including ultrasound, which offers a non-invasive and informative approach to planning surgical correction of age-related soft tissue changes (Sharobaro, 2021). During the work of V.I. Sharobaro (2021), the high information content of this method was noted [

1].

Contemporary correction methods require a comprehensive and individualized approach, considering factors such as mandible size and shape, distribution of cervical fat, location of the hyoid bone, and variations in subcutaneous muscle fibers of the neck. Thorough analysis of these parameters is essential for attaining optimal aesthetic outcomes [

2].

A notable advantage of aesthetic surgery is its lack of standardization. Similar to art, it relies on subjective judgments from both the patient and the surgeon. Consequently, various approaches for treating aging neck, such as neck liposuction, bilateral platysma plication, median platysma plication with distal fiber intersection, neck lift with skin and soft tissue excision, and botulinum toxin injections for platysma relaxation, are suitable for specific patient groups. It is crucial for surgeons to have a comprehensive understanding of these approaches to deliver the best aesthetic results for each individual patient.

2. The Evolution of Platysmaplasty: A Historical Analysis of Advancements in Surgical Techniques for Facial Rejuvenation

An extensive analysis of the available literature reveals significant advancements in the field of surgical correction for the face and neck, underscoring the evolution of techniques employed in facial rejuvenation. In earlier years, rhytidectomy (facelift) predominated as the primary approach; however, the advent of platysmaplasty has emerged as a pivotal component in achieving harmonious and comprehensive aesthetic outcomes [

3].

The historical progression of platysmaplasty techniques demonstrates notable contributions from pioneering surgeons. J. Bourguet’s seminal work in 1928 introduced the concept of platysmaplasty through a chin incision. Subsequently, T. Skoog’s innovative technique in 1969 introduced a single-layer neck plasty approach, involving the suspension of skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscles through lateral incisions. J. Guerro-Santos’ contributions in 1978 encompassed the lateral fusion of the platysma with the sternocleidomastoid fascia and mastoid periosteum. Further advancements were observed with J.J. Feldman’s corset platysmaplasty technique in 1990, involving suturing the medial crura of the platysma. Simultaneously, V.C. Giampapa and B. Di Bernardo introduced the concept of suspension neck correction, initially as a complement to traditional facelift procedures and later as a closed neck lift technique. A.F. del Campo’s novel “hammock platysmaplasty” technique in 1998 employed double-breasted platysma plication to the mastoid fascia [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Despite these advancements, challenges persist in addressing neck aging and the prominence of platysmal bands, necessitating ongoing discussions and investigations to determine the optimal methods for achieving more pronounced and enduring aesthetic outcomes.

3. Anterior (Medial) Platysmaplasty: A Comprehensive Analysis of Surgical Correction Techniques for the Cervical-Chin Region

The most prevalent approach for surgically correcting the cervical-chin region is liposuction combined with medial platysmaplasty. Initially, the procedure involved direct excision of skin in the central neck area, a method frequently mentioned in scientific literature [

9]. However, this technique often resulted in visible scars on the neck, leading to disappointment for both patients and surgeons [

11]. Nonetheless, it remains the preferred method in male patients with significant excess skin (T.C. Biggs). In cases without significant excess skin, the anterior platysmaplasty technique is also employed in female patients. This technique involves a transverse skin incision along the chin fold or slightly lower, followed by dissection to the cricoid cartilage. The medial pedicles of the platysma are then isolated and sutured along the midline from the chin to the thyroid cartilage [

9].

To achieve a well-defined contouring of the cervical-chin angle, medial platysmaplasty is commonly combined with liposuction or lipectomy. The removal of pre-platysmal fat can be performed through a chin incision or via lipo-aspiration. It is important to note that a normal, aesthetically pleasing neck possesses a layer of subcutaneous fat that contributes to a smooth contour and allows for proper movement along the platysma [

12,

13]. The decision to excise sub-platysmal fat is typically made intraoperatively. Sensible removal leads to improved neck contours, while excessive removal can result in secondary chin depression and deformities in the chin region. Thus, if sub-platysmal fat must be removed, the surgeon must ensure a safe midline closure to address any deficit [

13,

14,

15]. In patients with an obtuse cervical-chin angle and good skin elasticity, a single liposuction or open lipectomy with platysmaplasty procedure is generally sufficient [

16].

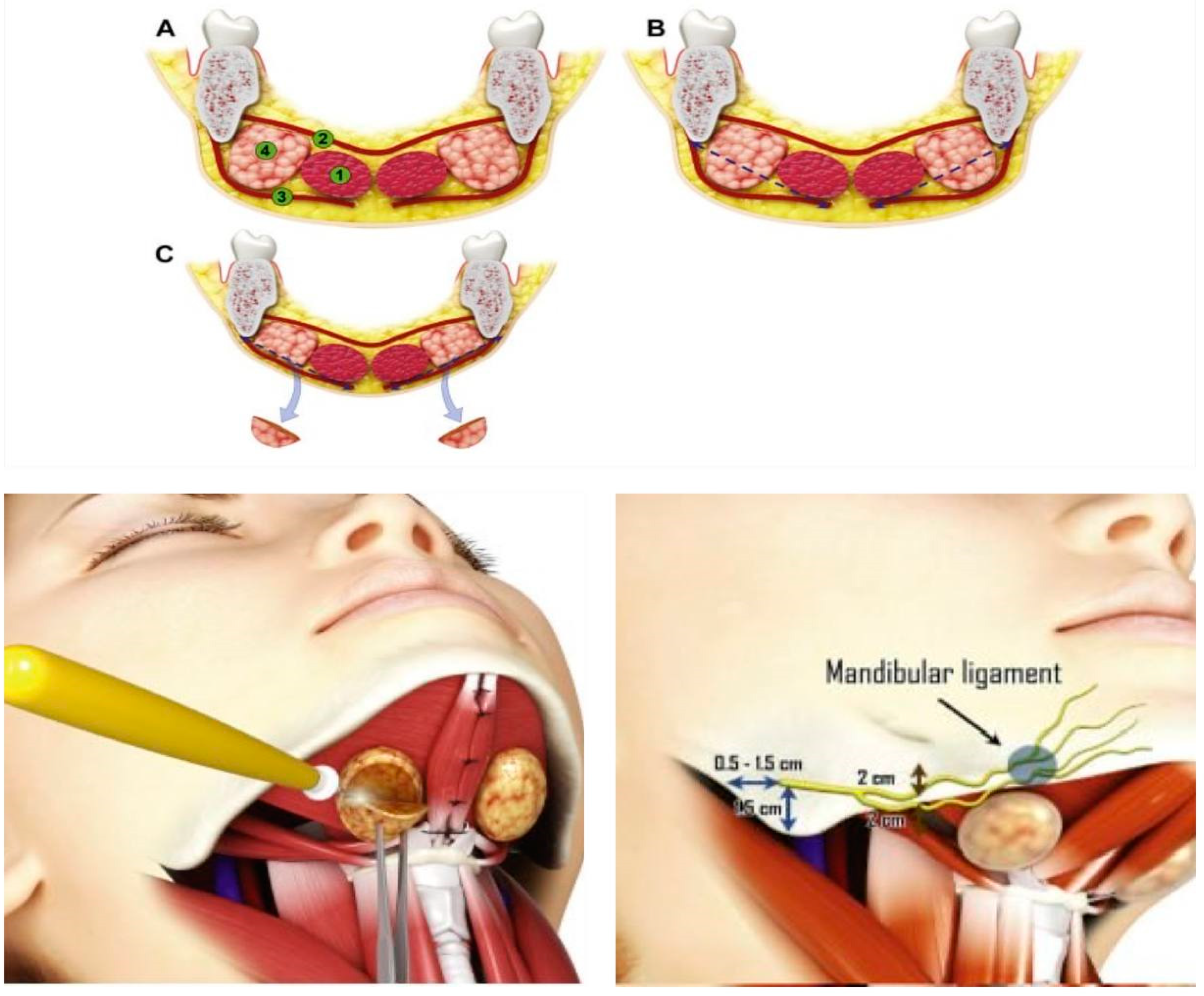

The anterior platysmaplasty approach is particularly suitable for addressing excess subplatysmal fat, protruding submandibular glands, bulky anterior digastric bellies, or “hard” dynamic platysmal bands. A study by A. L. Kochuba (2021) demonstrates the effectiveness of median platysmoplasty in correcting subplatysmal structures in patients with an obtuse cervical-chin angle [

17].

The corset platysmaplasty technique, initially introduced by J. J. Feldman in 1990 and subsequently modified in 2014 [

6,

18], capitalizes on the firmness of the lateral fascia enveloping the neck with age. This technique involves tightening medially relative to fixed lateral anchorages to shape the chin-cervical angle. Excess neck skin can be excised laterally or allowed to contract naturally. A key advantage of this technique is the robustness of the medial closure. Later modifications by J. J. Feldman (2014) include additional study of subplatysmal structures. It is worth noting that the necessity of median platysmaplasty is a topic of discussion among many authors due to the frequent recurrence of platysmal cords, prompting considerations for modifications to this procedure [

19,

20,

21]. A. A. Jacono also asserts that median platysmaplasty significantly reduces the volume of facial tissue lifted during SMAS-lifting [

22]. In simultaneous face and neck lifts, platysmaplasty should be performed after the buccal SMAS flap has been incised and suspended, as this sequence allows for optimal correction of the cervical-chin angle without impeding maximum face lifting [

9].

E.R. Citarella introduced the concept of reinforcing sutures to prevent the divergence of the medial edges of the platysma muscle. This triple suture technique enhances neck contouring and creates a vertical traction vector, thereby improving the aesthetic outcome [

23].

The muscle hypothesis proposed to explain the pathophysiology of paramedian platysmal bands appears insufficient in fully explaining the clinical manifestations observed in elderly individuals with cervical soft tissue laxity. In a retrospective analysis of computed tomography scans, K. Davidovic et al. found that the contraction of platysma muscle fibers leads to the elevation of the most medial fibers, which do not attach in the area of fascial fusion. Therefore, surgical treatment should involve the dissection of fascial adhesions to potentially prevent the recurrence of paramedian platysmal bands [

24].

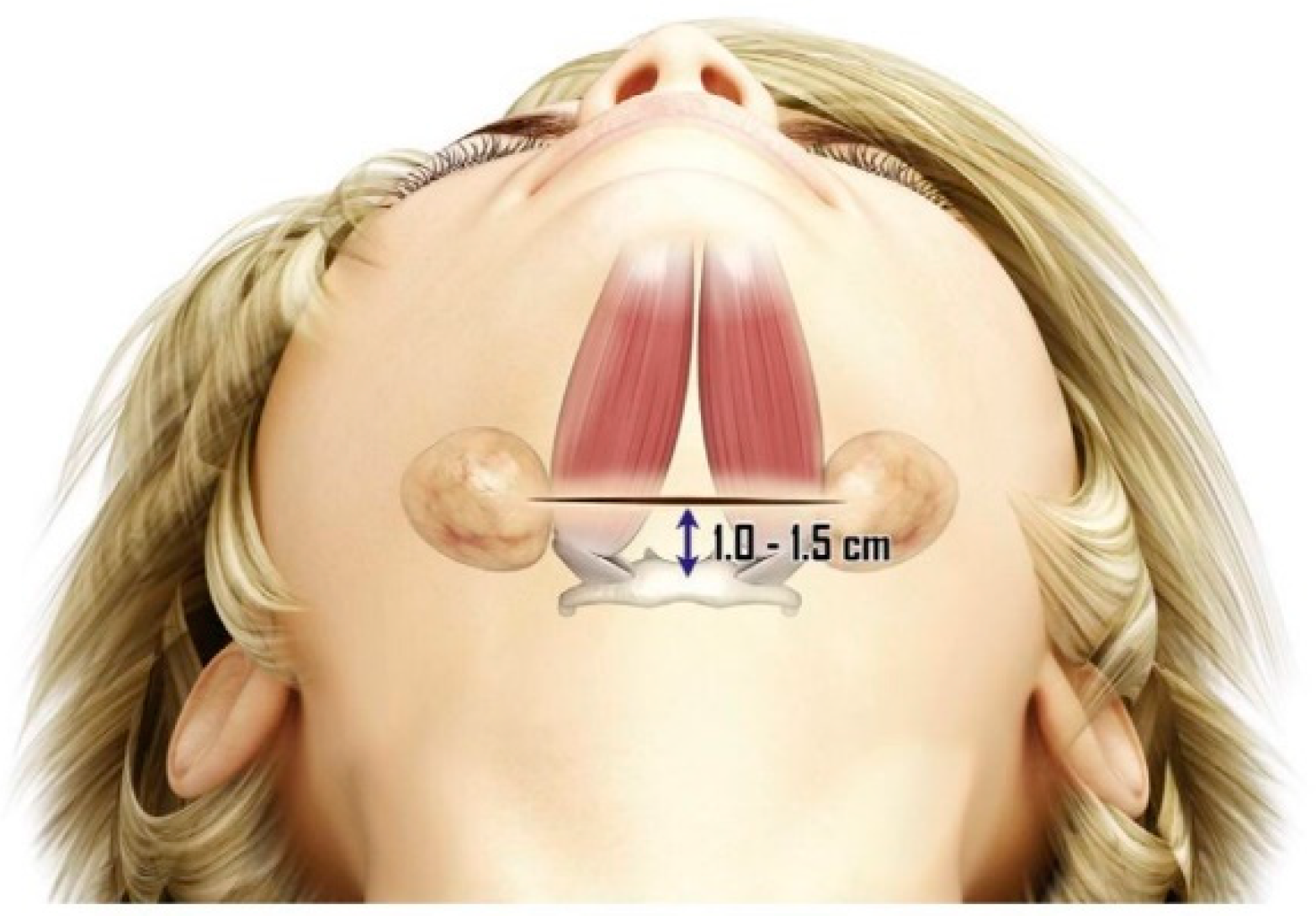

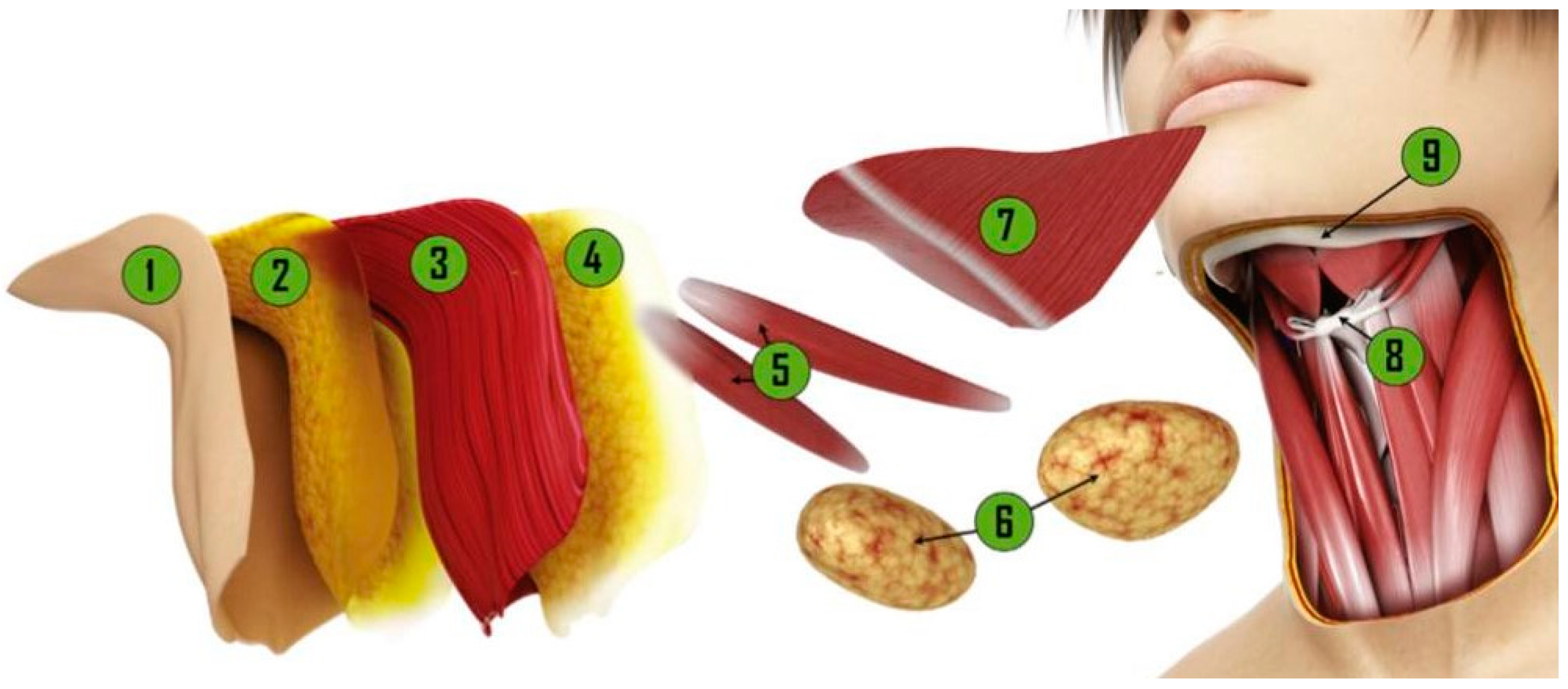

During medial platysmaplasty, myotomy (dissection) of the subcutaneous muscle strands can be performed to correct their appearance. A low medial partial incision is made to minimize medial tension, while a partial lateral incision may facilitate vertical elevation of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) [

25]. Complete transection of the platysma muscle is less commonly performed, typically reserved for cases with very obtuse angles where maximum contouring is required [

9] (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

4. Lateral platysmaplasty.

Lateral platysmaplasty is a successful technique employed in cases of mild platysmal sagging. By applying lateral traction, the platysmal bands can be corrected. Typically, the lateral border of the saphenous muscle is sutured to the sternocleidomastoid fascia, although some authors suggest attachment to the preauricular fascia or peri-parotid fascia, which provides a more vertical vector of support and elevation. This approach ensures a smooth and even neck contour and enhances the results of neck lifting procedures [

9,

26,

27,

28].

The current trend in lateral platysmaplasty aims to minimize complications by avoiding extensive anterior neck dissection, which has contributed to the increasing popularity of this lateral and upward tension approach [

22].

M. Pelle-Ceravolo proposed a technique involving lateral displacement of both the skin and platysma, achieved through suspension sutures. This method offers several advantages, including limited neck dissection, a low risk of paramedial band recurrence, easy access to the submandibular gland, the absence of a chin scar, and faster patient recovery. Overall, satisfactory results have been reported with this approach [

29].

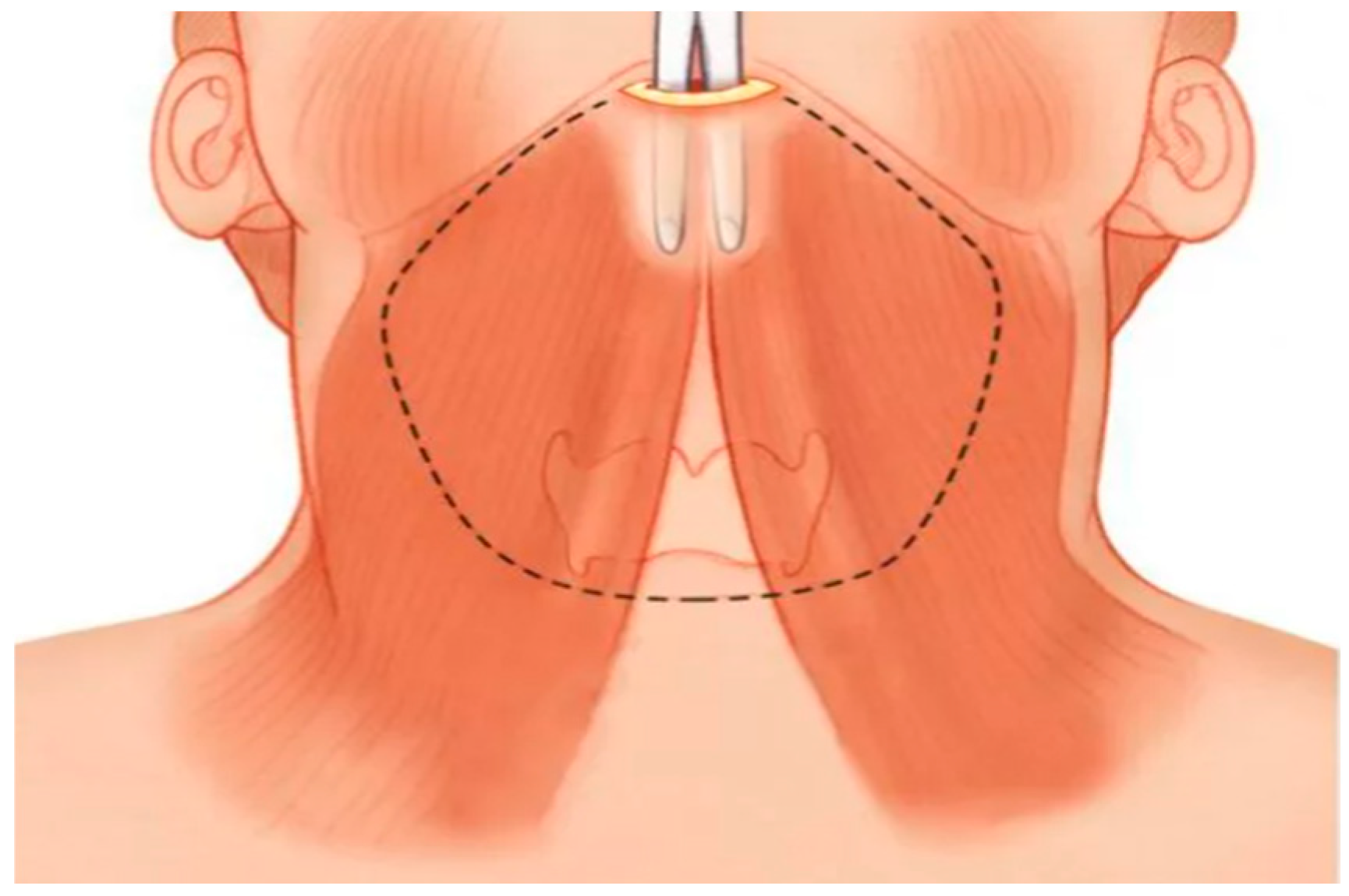

Lateral platysmaplasty is commonly performed in combination with a facelift, utilizing composite techniques to improve outcomes. W. Chin-Ho (2022) introduced a combined composite lift technique that allows for safe dissection of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) and facilitates lateral movement of the platysma (

Figure 3). During neck dissection, the cervical retaining ligaments along the posterior-outer edge of the platysma are released from the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Composite flap fixation is achieved using Ethibond 3/0 sutures, typically applying five fixation sutures from the lower face to the zygomatic bone. The dissected lateral portion of the platysma is divided into two flaps: the upper flap is secured with two figure-of-eight sutures to the Laura fascia in front of the tragus, while the lower flap is fixed to the periosteum of the mastoid process with two fixation sutures [

25].

A study conducted by M. Pelle-Ceravolo investigated partial and complete myotomy of the platysma and concluded that complete myotomy requires a longer rehabilitation period and increases the risk of iatrogenic deformities [

19]

5. Mixed platysmaplasty.

A comprehensive comprehension of the anatomical and physiological aspects of neck aging is crucial in order to better comprehend the combination of platysmal correction techniques. Numerous studies have indicated that the implementation of mixed platysmaplasty results in increased satisfaction for both patients and surgeons [

30].

In a study conducted by L. Charles-de-Sá et al., the authors aimed to determine whether the traction of the lateral platysma could potentially increase the distance between the medial platysmal bands. However, their findings concluded that the lateral platysmal approach, whether through plication or dissection, does not lead to an expansion of the distance between the medial platysmal bands [

31].

One of the pioneering techniques in the field of platysmaplasty is the suspension suture technique introduced by V.C. Giampapa in 1995. This technique has proven to be highly effective and has been widely adopted by many surgeons. In 2013, the author himself made improvements to the technique, further enhancing its efficacy.

Suture suspension platysmaplasty of the neck involves the creation of a permanent artificial “ligament” beneath the lower jaw, effectively correcting the deformities associated with aging neck. This method is characterized by its simplicity, safety, and reproducibility, ultimately leading to excellent patient outcomes [

32,

33].

In 2021, M. Robenpour and colleagues proposed their own version of the suspension suture technique developed by V.C. Giampapa. However, some patients who underwent suspensory platysmaplasty reported prolonged discomfort, excessive neck tightening, and recurrence of deformities. To address these concerns, the author devised a new technique involving the use of wide suspension sutures. This technique, known as “hanging wide seams,” resulted in improved aesthetic outcomes and did not require any further interventions during the observation period from 2015 to 2017 [

34].

It is important to note that this technique may not be suitable for patients with excessive tissue and skin laxity. Its primary focus lies in correcting age-related deformities caused by subplatysmal structures in the cervical-chin region. In the current era of minimally invasive procedures, both surgeons and patients are seeking methods that offer maximum improvement with minimal intervention. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that limited incisions and minimal intervention do not always yield the best results [

22].

The relationship between the musculoskeletal support of the lower face and the surgical anatomy of the anterior neck is intricate and multifaceted. Extensive research in this area has contributed to a better understanding of how various anatomical structures in the anterior neck impact the overall appearance of the neck [

35,

36].

And as evidenced by a growing body of literature over the past three decades, there has been an increasing number of authors advocating for a more comprehensive approach to aesthetic surgery of the neck. This approach includes addressing various subplatysmal structures such as deep fatty tissue, anterior digastric muscles, submandibular gland, and the hyoid bone [

37,

38].

Numerous studies on hypertrophy of the digastric muscles have led authors to conclude that a partial tangential resection is often necessary for improving contour without causing functional deficits.

In a recent study by Th. G. O’Daniel (2021) involving 152 patients, the optimization of neck lifting was evaluated. The findings suggested that reduction sculpting and hyoid bone repositioning are typically required in most cases [

39].

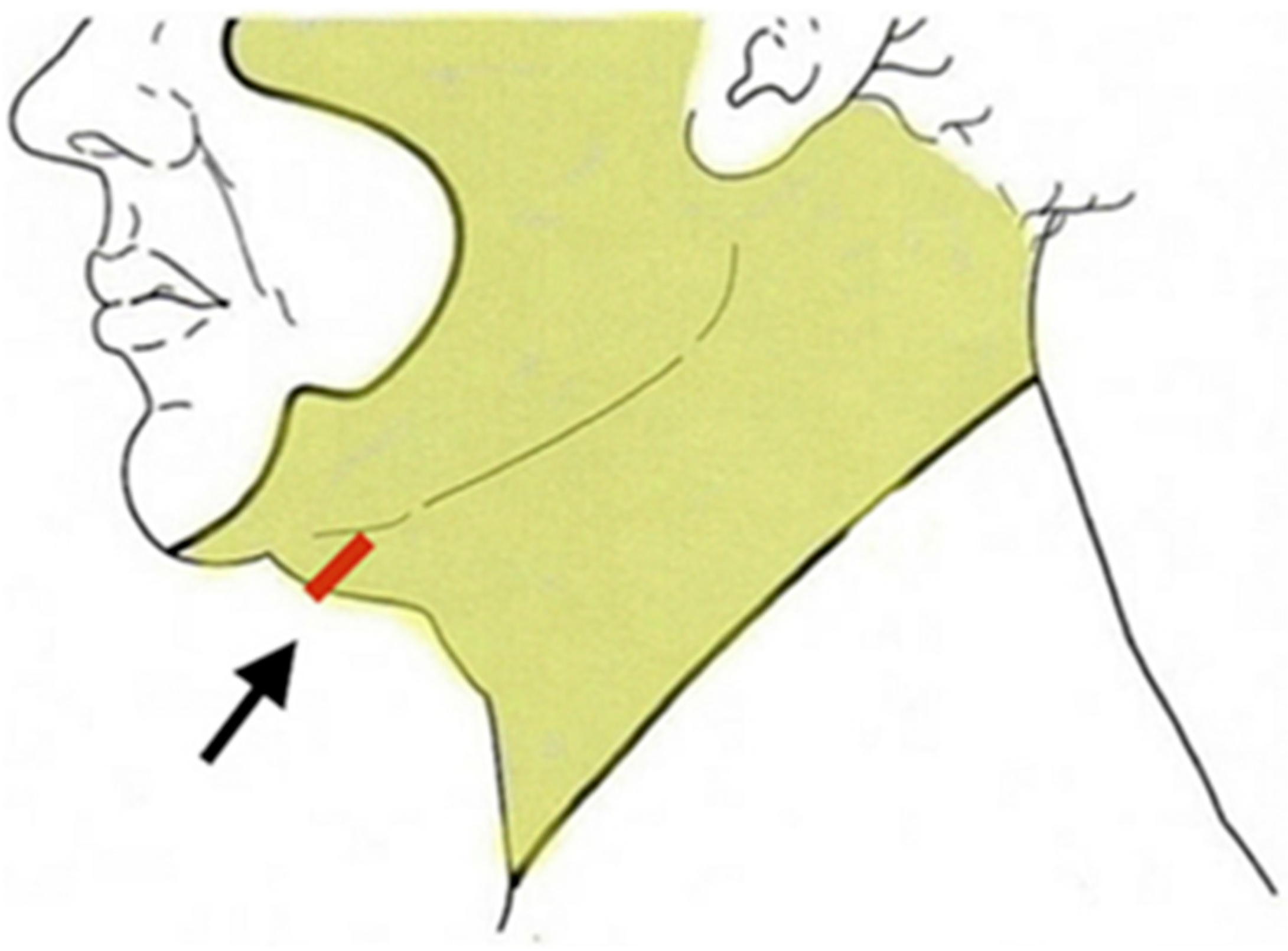

It is important to note that the position of the hyoid bone can significantly impact the overall shape of the neck. In individuals with a desired cervical-chin angle of 90° to 110°, the hyoid bone is vertically aligned with the fourth cervical vertebra [

40].

For patients with an obtuse cervical-chin angle, the hyoid bone tends to be positioned below the fourth cervical vertebra. In 2016, C. Le Louarn proposed a technique to recreate an acute chin-cervical angle by suturing the platysma and skin to the hyoid bone [

41].

In order to improve results and efficiency, a significant technique modification for the sublingual neck lift was proposed in 2018. This modification involves dissecting the supra- and sub-platysmal fatty tissue from the lateral access dissection to the medial edge of the platysma, and subsequently fixing the platysma to the deep cervical fascia under visual control. Additionally, the lateral edge of the platysmal flap is suspended from the periosteum of the mastoid process. If necessary, partial excision of the submandibular gland can also be performed through the same access [

42].

In certain patients, ptosis of the submandibular gland is commonly observed, resulting in visible deformation of the submental region. Treatment options for this condition include partial resection, mandibular duplication sutures, and transcervical suspension sutures [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52] (

Figure 3).

However, it is important to note that surgical manipulations on the submandibular gland carry risks such as hematoma formation from glandular vessels, potential damage to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve, and long-term healing complications of salivary gland fistulas.

C. Mogelvang proposed a technique for correcting a ptotic submandibular gland called X-platysmaplasty, where the medial cords of the platysma muscle are isolated and crossed to form an X shape. The defect is sutured after removing the cut strip. This X shape is created at the level of or slightly above the cervical-mental angle, approximately at the level of the hyoid bone [

53].

T. Marten focused on correcting platysma bands and their variations. He emphasizes the importance of an individualized approach for each patient. However, like the authors mentioned above, I believe that working with subplatysmal tissues yields the best results [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58] (

Figure 4).

The aforementioned subplatysmal techniques enable the modification of the anterior contours of the neck by reducing the volume or repositioning the subplatysmal structures, resulting in long-term correction (

Figure 5).

6. Minimally Invasive Techniques for Facial Lower Third Rejuvenation

Minimally invasive techniques for rejuvenating the lower third of the face have revolutionized the field of plastic surgery. S. R. Coleman’s pioneering work on lipofilling, a procedure involving the transplantation of stem cells for rejuvenation, has emerged as an invaluable adjunct to traditional surgical approaches. Additionally, a range of minimally invasive procedures such as laser skin resurfacing, chemical peels, dermabrasion, botulinum toxin therapy, and volumetric fillers have significantly expanded the repertoire of facial aging treatments [

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69].

In the realm of lower facial rejuvenation, R. Gonzalez has described an innovative variant of closed myotomy of the medial strands of the platysma. This technique employs the use of a reversible percutaneous puncture with a 16-gauge needle, followed by the passage of a 3/0 nylon thread to precisely cut the muscle [

70]. Another temporary measure for addressing the anterior platysmal bands involves the injection of neuroprotein, which has shown particular efficacy in younger patients and those with dense skin [

71,

72,

73].

Thread lifting is yet another temporary approach that can provide support to neck structures and augment the outcomes of previous surgeries [

74,

75]. Notably, this technique boasts a relatively short rehabilitation period [

76]. However, its acceptance is somewhat limited due to its brief duration of effect and occasional risk of extrusion [

77].

To optimize outcomes and enhance the stability and distinctiveness of results, it has been found that a synergistic amalgamation of multiple surgical procedures during the recovery phase can play a pivotal role. This comprehensive approach has shown remarkable improvements in patients’ overall quality of life.

7. Algorithm for Postoperative Care and Management of Patients Following Lower Third Face Rejuvenation

The preoperative assessment of patients undergoing lower third face rejuvenation is of utmost importance in ensuring successful outcomes. This assessment should encompass a range of diagnostic procedures, including CT, MRI, and ultrasound examinations. Additionally, the utilization of modeling techniques allows for visualization of the desired postoperative results, while adhering to established beauty canons and the golden ratio. Notably, a study conducted by R. Ellenbegen and J.V. Karlin in 1980 identified five key criteria for determining an aesthetically pleasing contour of the lower third of the face. These criteria encompass the presence of smooth skin devoid of hyperelastosis, wrinkles, and horizontal folds, a well-defined cervical-mental angle, absence of platysma bands, and visible anterior borders of the sternocleidomastoid muscles [

51,

78,

79,

80].

While surgeons strive for optimal outcomes in lower third face anti-aging procedures, it is crucial to acknowledge the potential risks of complications. Among the most serious complications during the early postoperative period are necrosis, severe hematoma, and paresis. Assessing the viability of the skin flap during dissection and determining appropriate tissue tension play pivotal roles in mitigating the risks of ischemia and subsequent flap necrosis. Effective vascular therapy and meticulous hemostasis techniques are essential in reducing the incidence of hematomas immediately after surgery (

Figure 6).

Late postoperative complications may include hypertrophic scars, excessive fibrosis of the soft tissues, submental area retraction, prolonged swelling, and bruising. To ensure optimal recovery, a well-planned recovery process should be implemented at a specialized rehabilitation center. Proper planning and adherence to the rehabilitation period are crucial for achieving a favorable final outcome. Lymphotropic therapy, as demonstrated in a study by O.V. Vozgoment et al. in 2021, has shown promising results in lymphatic drainage, leading to a reduction in edema [

81].

8. Conclusions

The advancements in surgical strategies for enhancing the submental and cervicofacial regions have paved the way for achieving harmonious outcomes in the correction of age-related changes in the face and neck. It is crucial to consider the individual anatomical characteristics of each patient and the extent of their age-related changes in order to tailor the surgical approach accordingly. A comprehensive analysis of the face, incorporating techniques such as ultrasound imaging of the soft tissues of the chin zone, enables the creation of a personalized plan that aligns with the patient’s desired outcome and the surgeon’s capabilities. Collaboration between cosmetology and plastic surgery becomes increasingly important as patients age, as they complement each other in delivering rejuvenating effects on both the shape and volume of the skin, as well as tissue quality. To achieve lasting results in addressing facial and neck aging, it is imperative to master a diverse range of techniques, utilizing an array of tools and approaches at our disposal. By continuously advancing our knowledge and expertise in these surgical strategies, we can consistently strive towards optimal outcomes and enhanced patient satisfaction.

9. Future Directions

In the field of surgical interventions, future directions for research will increasingly emphasize personalized approaches that account for individual anatomical characteristics. This approach will encompass not only evaluating factors such as BMI and the type of aging but also considering potential comorbidities. The aim is to proactively prepare patients for the preoperative period and optimize their postoperative rehabilitation, with the ultimate goal of minimizing complications and enhancing overall patient satisfaction with the surgical procedure.

Advancements in medical imaging techniques, including MRI, computed tomography, and duplex scanning, will undoubtedly shape future surgical planning. These objective assessment methods will enable surgeons to tailor their surgical strategies based on a patient’s unique anatomical features, in alignment with principles of proportion and the golden ratio.

Furthermore, the future will witness increased collaboration among surgeons, cosmetologists, and physiotherapists in the development of comprehensive preoperative preparation protocols and postoperative care algorithms. These collaborative efforts will aim to minimize postoperative complications, expedite the rehabilitation process, and ultimately enhance patient satisfaction with the surgical outcomes.

By focusing on these future directions, scientific research in the field of surgical interventions can pave the way for advancements in personalized approaches, optimized surgical planning techniques, and interdisciplinary collaboration. These endeavors will contribute to improved patient outcomes, furthering our understanding and refining the art and science of surgical interventions in the submental and cervicofacial regions.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).*****

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alimova, S. M., Sharobaro, V. I., Telnova, A. V., & Stepanyan, E. E. (2021). Planning of methods of surgical correction of soft tissues of the face and neck. Medical Visualization, 25(4), 47–52] . [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, S. S.; Anthony, D. J.; Ion, L. An Anatomic Basis for Volumetric Evaluation of the Neck. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2012, 32 (6), 685–691. [CrossRef]

- Sinno, S.; Thorne, C. H. Cervical Branch of Facial Nerve: An Explanation for Recurrent Platysma Bands Following Necklift and Platysmaplasty. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2018, 39 (1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Frisenda, J.; Nassif, P. Correction of the Lower Face and Neck. Facial Plast. Surg. 2018, 34 (05), 480–487. [CrossRef]

- de Castro, C. C. The Anatomy of the Platysma Muscle. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 1980, 66 (5), 680–683. [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J. J. Corset Platysmaplasty. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 1990, 85 (3), 333–343. [CrossRef]

- del Campo, A. F. Midline Platysma Muscular Overlap for Neck Restoration. Plast. & Reconstr.e Surg. 1998, 102 (5), 1710–1714. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Santos, J. The Role of the Platysma Muscle in Rhytidoplasty. Clinics in Plast. Surg. 1978, 5 (1), 29–49. [CrossRef]

- Fuentedelcampo, A. Continuing Medical Education Examination—Facial Aesthetic Surgery the Hammock Platysmaplasty. Aesthetic Surg. J. 1998, 18 (4), 246–252. [CrossRef]

- Giampapa, V.; Bitzos, I.; Ramirez, O.; Granick, M. Long-Term Results of Suture Suspension Platysmaplasty for Neck Rejuvenation: A 13-Year Follow-up Evaluation. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2005, 29 (5), 332–340. [CrossRef]

- Adamson, J. E.; Horton, C. E.; Crawford, H. H. The surgical correction of the “Turkey gobbler” deformity. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 1964, 34 (6), 598–605. [CrossRef]

- Fezza, J. P. Face-Lifting in the Full Neck. Springer eBooks 2014, 613–614. [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Pindar, C.; Katira, K.; Bahman Guyuron. Neck Contouring without Rhytidectomy in the Presence of Excess Skin. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2017, 42 (2), 464–470. [CrossRef]

- Gryskiewicz, J. M. Submental Suction-Assisted Lipectomy without Platysmaplasty: Pushing the (Skin) Envelope to Avoid a Face Lift for Unsuitable Candidates. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg.2003, 112 (5), 1393–1405; discussion 1406-1407. [CrossRef]

- O’Daniel, T. G. Optimizing Outcomes in Neck Lift Surgery. J. Aesthetic Surg. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Barton Jr., F. E. Aesthetic Surgery of the Face and Neck. J. Aesthetic Surg. 2009, 29 (6), 449–463. [CrossRef]

- Kochuba, A. L.; Surek, C. C.; Ordenana, C.; Vargo, J.; Scomacao, I.; Duraes, E.; Zins, J. E. Anterior Approach to the Neck: Long-Term Follow-Up. J. Aesthetic Surg. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J. J. Neck Lift My Way. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 134 (6), 1173–1183. [CrossRef]

- Pelle-Ceravolo, M.; Angelini, M.; Silvi, E. Complete Platysma Transection in Neck Rejuvenation. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 138 (4), 781–791. [CrossRef]

- Pelle-Ceravolo, M.; Angelini, M.; Silvi, E. Treatment of Anterior Neck Aging without a Submental Approach. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 139 (2), 308–321. [CrossRef]

- Sinno, S.; Thorne, C. H. Cervical Branch of Facial Nerve: An Explanation for Recurrent Platysma Bands Following Necklift and Platysmaplasty. J. Aesthetic Surg. 2018, 39 (1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Jacono, A. A.; Malone, M. H. The Effect of Midline Corset Platysmaplasty on Degree of Face-Lift Flap Elevation during Concomitant Deep-Plane Face-Lift. JAMA Facial Plast. Surg. 2016, 18 (3), 183–187. [CrossRef]

- Citarella, E. R.; Condé-Green, A.; Sinder, R. Triple Suture for Neck Contouring: 14 Years of Experience. J. Aesthetic Surg. 2010, 30 (3), 311–319. [CrossRef]

- Davidovic, K.; Frank, K.; Schenck, T. L.; Cohen, S. R.; Dayan, S.; Gotkin, R. H.; Sykes, J. M.; Liew, S.; Gavril, D.; Cotofana, S. Anatomy behind the Paramedian Platysmal Band: A Combined Cadaveric and Computed Tomographic Study. Plast. & Reconstr. Surg.2021, 148 (5), 979–988. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.-H.; Hsieh, M. K. H.; Mendelson, B. Asian Face Lift with the Composite Face Lift Technique. Plast. & Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 149 (1), 59–69. [CrossRef]

- Fogli, A. L. Skin and Platysma Muscle Anchoring. Aesthetic Plast. Surg.2008, 32 (3), 531–541. [CrossRef]

- Ellenbogen, R.; Karlin, J. V. Visual Criteria for Success in Restoring the Youthful Neck. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 1980, 66 (6), 826–837. [CrossRef]

- Botti, C.; Botti, G. Facelift 2015. Facial Plast. Surg. 2015, 31 (05), 491–503. [CrossRef]

- Pelle-Ceravolo, M.; Angelini, M. Lateral Skin–Platysma Displacement. Clinics in Plast. Surg. 2019, 46 (4), 587–602. [CrossRef]

- Ozcan Cakmak; Ismet Emrah Emre; Berke Ozucer. Surgical Approach to the Thick Nasolabial Folds, Jowls and Heavy Neck—How to Approach and Suspend the Facial Ligaments. Facial Plast. Surg. 2018, 34 (01), 059–065. [CrossRef]

- Charles-de-Sá, L.; Gontijo-de-Amorim, N. F.; Loureiro Claro, V.; Vieira, D. M. L.; de Andrade, G. M.; Dantas-Rocha, L.; da Silva, C. G. R.; Abboudib, J. H.; de Castro, C. C. Does the Approach of the Lateral Platysmal Bands Widen the Gap between the Medial Bands? Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. - Global Open 2020, 8 (6), e2853. [CrossRef]

- Giampapa, V. C.; Mesa, J. M. Neck Rejuvenation with Suture Suspension Platysmaplasty Technique. 2014, 41 (1), 109–124. [CrossRef]

- Daniels, M.; Agag, R.; Dobryansky, M.; Giampapa, V. C. Review of 500 Suture Suspension Platysmaplasties. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 130, 88. [CrossRef]

- Manoocher Robenpour; Shir Fuchs Orenbach; Reut Hadash-Bengad; Ophir Robenpour; Heller, L. The Wide Suture Suspension Platysmaplasty, a Revised Technique for Neck Rejuvenation: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. of Cosmetic Dermatology 2021, 20 (11), 3603–3609. [CrossRef]

- O’Daniel, T. G. Understanding Deep Neck Anatomy and Its Clinical Relevance. Clinics in Plast.Surg. 2018, 45 (4), 447–454. [CrossRef]

- Labbé, D.; Rocha, C. S. M.; de Souza Rocha, F. Cervico-Mental Angle Suspensory Ligament: The Keystone to Understand the Cervico-Mental Angle and the Ageing Process of the Neck. Aesth. Plast. Surg.2017, 41 (4), 832–836. [CrossRef]

- Auersvald, A.; Auersvald, L. A.; Oscar Uebel, C. Subplatysmal Necklift: A Retrospective Analysis of 504 Patients. J. Aesthetic Surg. 2016, 37 (1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Bravo, F. G. Reduction Neck Lift. Clinics in Plast. Surg.2018, 45 (4), 485–506. [CrossRef]

- O’Daniel, T. G. Optimizing Outcomes in Neck Lift Surgery. J. Aesthetic Surg. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Marino, H.; Galeano E. J.; Gandolfo E. A. Plastic correction of double chin. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg.1963, 31 (1), 45–50. [CrossRef]

- C. Le Louarn. Hyo Neck Lift: Preliminary Report. 2016, 61 (2), 110–116. [CrossRef]

- Le Louarn, C. Hyo-Neck Lift Evolution: Neck Lift with Fixation of the Platysma to the Deep Cervical Fascia. Annales de Chirurgie Plastique Esthétique 2018, 63 (2), 164–174. [CrossRef]

- Shirakabe, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Lam, S. M. A New Paradigm for the Aging Asian Face. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2003, 27 (5), 397–402. [CrossRef]

- Singer, D. P.; Sullivan, P. K. Submandibular Gland I: An Anatomic Evaluation and Surgical Approach to Submandibular Gland Resection for Facial Rejuvenation. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 2003, 112 (4), 1150–1154. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P. K.; Freeman, M.; Schmidt, S. Contouring the Aging Neck with Submandibular Gland Suspension. J. Aesthetic Surg. 2006, 26 (4), 465–471. [CrossRef]

- Bahman Guyuron; Jackowe, D. J.; Seree Iamphongsai. Basket Submandibular Gland Suspension. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 2008, 122 (3), 938–943. [CrossRef]

- Sepahdari, A.; Cohen, M.; Lee, M. Radiologic Measurement of Submandibular Gland Ptosis. Facial Plast. Surg. 2013, 29 (04), 316–320. [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, K.; Ramanadham, S.; O’Reilly, E.; Rohrich, R. J. Secondary Neck Lift and the Importance of Midline Platysmaplasty. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 137 (4), 667e675e. [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, B. C.; Tutino, R. Submandibular Gland Reduction in Aesthetic Surgery of the Neck. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 136 (3), 463–471. [CrossRef]

- Bravo, F. G. Reduction Neck Lift. Clinics in Plast. Surg. 2018, 45 (4), 485–506. [CrossRef]

- Auersvald, A.; Auersvald, L. A.; Oscar Uebel, C. Subplatysmal Necklift: A Retrospective Analysis of 504 Patients. J.Aesth. Surg. 2016, 37 (1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Auersvald, A.; Auersvald, L. A. Management of the Submandibular Gland in Neck Lifts. Clinics in Plast. Surg. 2018, 45 (4), 507–525. [CrossRef]

- Mogelvang, C. Roman II-X Platysmaplasty. J. of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2000, 106 (1), A1. [CrossRef]

- Marten, T.; Elyassnia, D. Neck Lift. Clinics in Plast. Surg. 2018, 45 (4), 455–484. [CrossRef]

- Marten, T.; Elyassnia, D. Management of the Platysma in Neck Lift. Clinics in Plast. Surg. 2018, 45 (4), 555–570. [CrossRef]

- Marten, T.; Elyassnia, D. Short Scar Neck Lift: Neck Lift Using a Submental Incision Only. Clinics in Plast. Surg. 2018, 45 (4), 585–600. [CrossRef]

- Marten, T. J. High SMAS Facelift: Combined Single Flap Lifting of the Jawline, Cheek, and Midface. Clinics in Plast. Surg. 2008, 35 (4), 569–603. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S. R. Long-Term Survival of Fat Transplants: Controlled Demonstrations. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2020, 44 (4), 1268–1272. [CrossRef]

- Ellenbogen, R. G. Free Autogenous Pearl Fat Grafts in the Face-A Preliminary Report of a Rediscovered Technique. Annals of Plast. Surg. 1986, 16 (3), 179–194. [CrossRef]

- Guerrerosantos, J. Simultaneous Rhytidoplasty and Lipoinjection: A Comprehensive Aesthetic Surgical Strategy. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 1998, 102 (1), 191–199. [CrossRef]

- Tonnard, P.; Verpaele, A.; Peeters, G.; Hamdi, M.; Cornelissen, M.; Declercq, H. Nanofat Grafting. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 132 (4), 1017–1026. [CrossRef]

- Rohrich, R. J.; Ghavami, A.; Constantine, F. C.; Unger, J.; Mojallal, A. Lift-And-Fill Face Lift. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 133 (6), 756e767e. [CrossRef]

- Baker, T. J. Chemical face peeling and rhytidectomy. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg.1962, 29 (2), 199–207. [CrossRef]

- Suhan Ayhan; Baran, C. N.; Reha Yavuzer; Osman Latifoğlu; Seyhan Çenetoğlu; Baran, N. K. Combined Chemical Peeling and Dermabrasion for Deep Acne and Posttraumatic Scars as Well as Aging Face. 1998. [CrossRef]

- Bagatin, E.; Gonçalves, H. de S.; Sato, M.; Almeida, L. M. C.; Miot, H. A. Comparable Efficacy of Adapalene 0.3% Gel and Tretinoin 0.05% Cream as Treatment for Cutaneous Photoaging. European J. of Dermatology 2018, 28 (3), 343–350. [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, C. N.; Huettner, F.; Ozturk, C.; Bartz-Kurycki, M. A.; Zins, J. E. Outcomes Assessment of Combination Face Lift and Perioral Phenol-Croton Oil Peel. Plast. and Reconstr.Surg. 2013, 132 (5), 743e753e. [CrossRef]

- Orra, S.; Waltzman, J. T.; Mlynek, K.; Duraes, E. F. R.; Kundu, N.; Zins, J. E. Periorbital Phenol-Croton Oil Chemical Peel in Conjunction with Blepharoplasty. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg.2015, 136, 99–100. [CrossRef]

- Sugrue, C. M.; Kelly, J. L.; McInerney, N. Botulinum Toxin Treatment for Mild to Moderate Platysma Bands: A Systematic Review of Efficacy, Safety, and Injection Technique. J. Aesthetic Surg. 2018, 39 (2), 201–206. [CrossRef]

- Duranti, F.; Salti, G.; Bovani, B.; Calandra, M.; Rosati, M. L. Injectable Hyaluronic Acid Gel for Soft Tissue Augmentation. Dermatologic Surg. 1998, 24 (12), 1317–1325. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R. (2009). Composite Platysmaplasty and Closed Percutaneous Platysma Myotomy: A Simple Way to Treat Deformities of the Neck Caused by Aging. J. Aesthetic Surg. 29(5), 344–354. [CrossRef]

- Corduff, N. Neuromodulating the SMAS for Natural Dynamic Results. Plast. and Reconstr. Surg.- Global Open 2021, 9 (8), e3755. [CrossRef]

- Sugrue, C. M.; Kelly, J. L.; McInerney, N. Botulinum Toxin Treatment for Mild to Moderate Platysma Bands: A Systematic Review of Efficacy, Safety, and Injection Technique. J. Aesthetic Surg. 2018, 39 (2), 201–206. [CrossRef]

- Matarasso, S. L.; Matarasso, A. Commentary On: Botulinum Toxin Treatment for Mild to Moderate Platysma Bands: A Systematic Review of Efficacy, Safety, and Injection Technique. J. Aesthetic Surg. 2018, 39 (2), 207–208. [CrossRef]

- Sulamanidze, M. A.; Paikidze, T. G.; Sulamanidze, G. M.; Neigel, J. M. Facial Lifting with “APTOS” Threads: Featherlift. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America 2005, 38 (5), 1109–1117. [CrossRef]

- Sulamanidze, M.; Sulamanidze, G. APTOS Suture Lifting Methods: 10 Years of Experience. Clinics in Plast. Surg. 2009, 36 (2), 281–306. [CrossRef]

- Mejia, J.; Nahai, F.; Nahai, F.; Momoh, A. Isolated Management of the Aging Neck. Seminars in Plast. Surg. 2009, 23 (04), 264–273. [CrossRef]

- Matarasso, A.; Paul, M. D. Barbed Sutures in Aesthetic Plastic Surgery: Evolution of Thought and Process. J. Aesthetic Surg. 2013, 33 (3_Supplement), 17S31S. [CrossRef]

- Manturova NE, Talolin NP, Andryushchenko OA. The use of algorithms in aesthetic facial surgery. Plast. Surg. and Aesth. Medicine. 2023;(2):67 75. [CrossRef]

- Chuang, J.; Barnes, C.; Wong, B. J. F. Overview of Facial Plastic Surgery and Current Developments. The Surg. Jour. 2016, 2 (1), e17–e28. [CrossRef]

- Pourdanesh, F.; Esmaeelinejad, M.; Jafari, S. M.; Nematollahi, Z. Facelift: Current Concepts, Techniques, and Principles. A Textbook of Advanced Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Volume 3 2016. [CrossRef]

- Vozgoment, A.G. Nadtochiy, V.A. Semkin, A.A. Ivanoval. The efficiency of lymphotropic therapy in patients with secondary lymphedema of the maxillofacial region. Kremlin medicine Journal 2021; 3: 21-30.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).