Submitted:

02 November 2023

Posted:

03 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

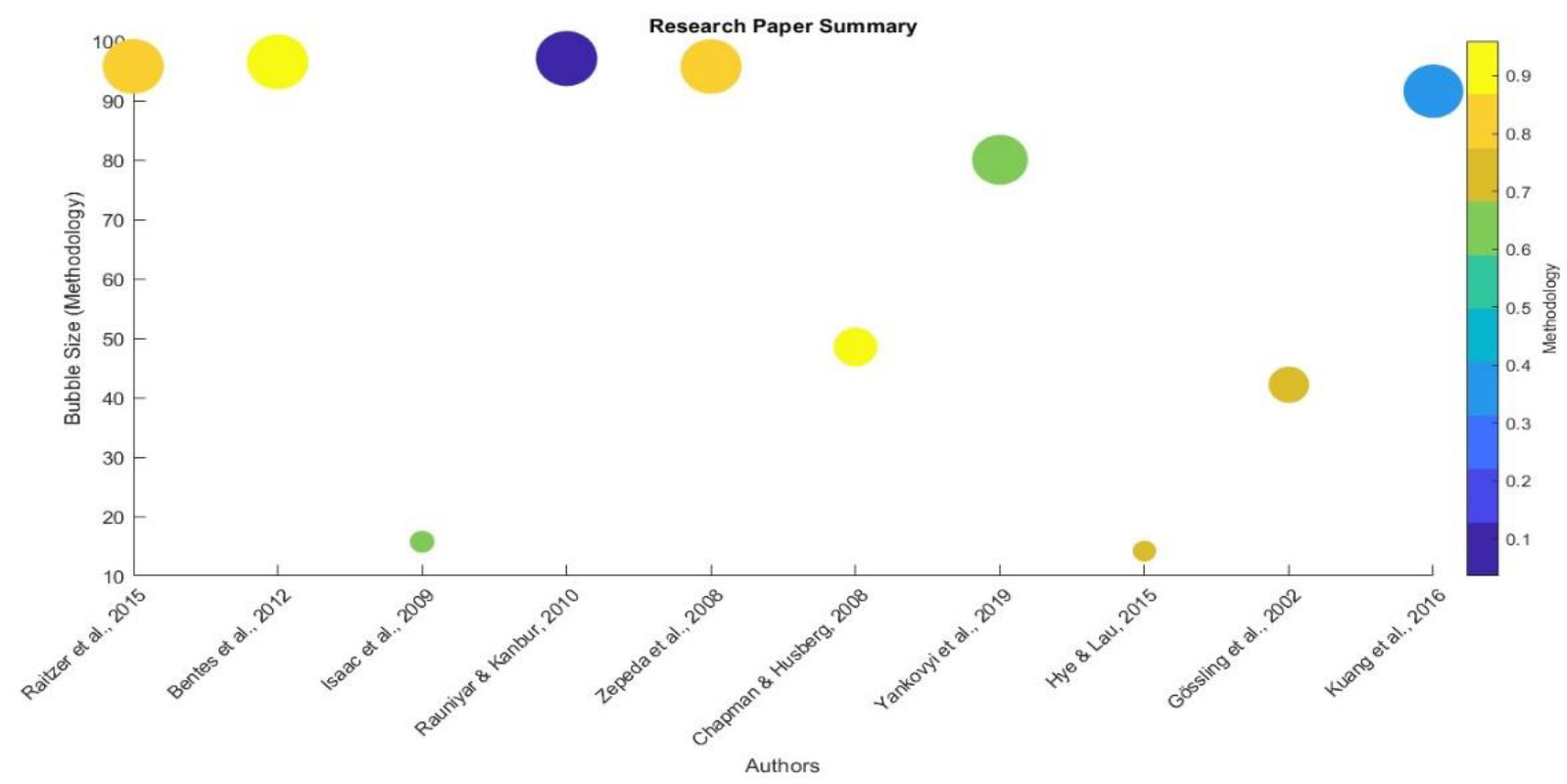

2.1. Details of previous research

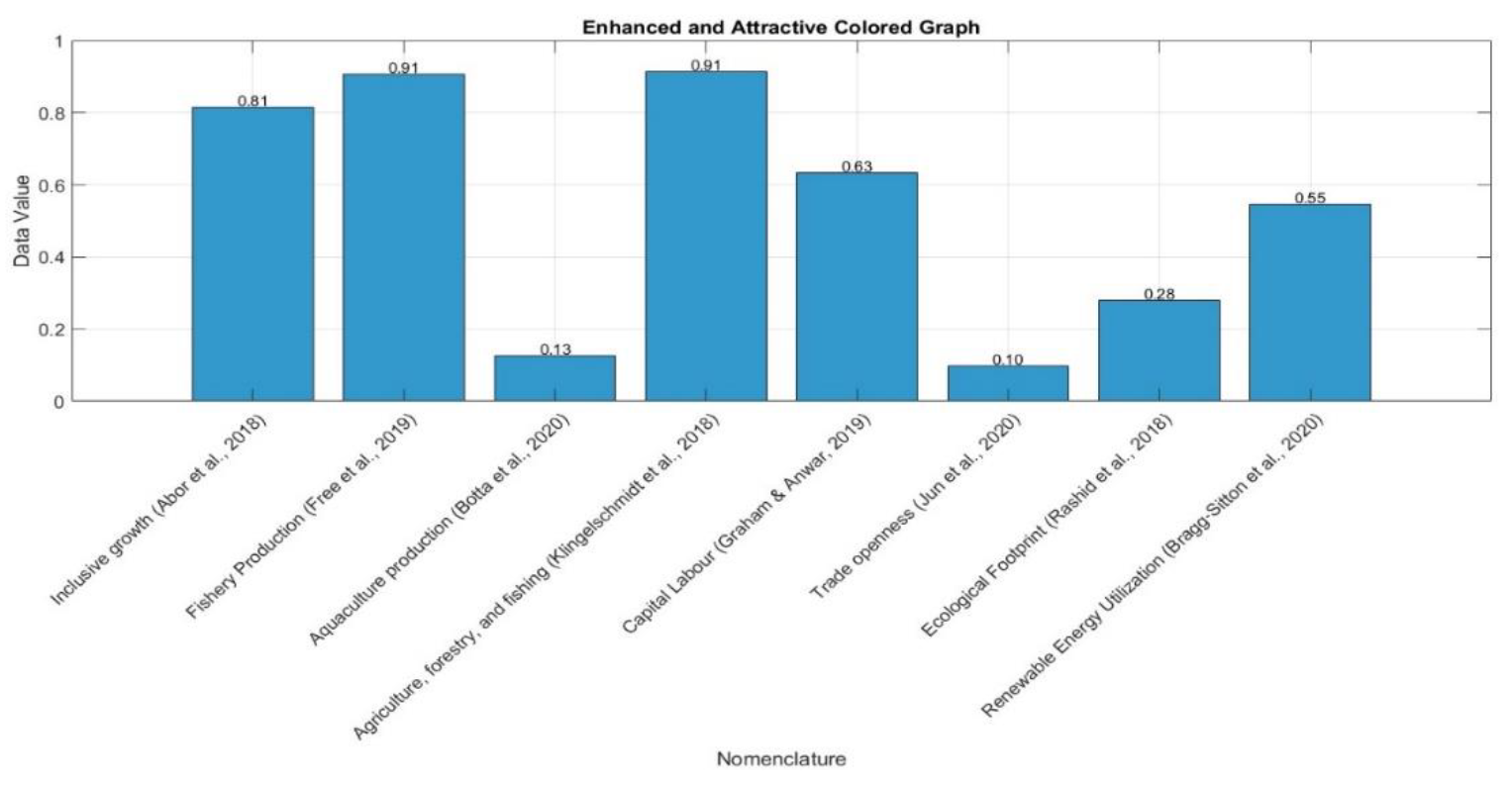

| Author(s) | Variables | Methodology | Findings |

| [82] | Inclusive growth | Mixed methods | The agricultural industry in Myanmar has a lot of untapped potential for promoting fair economic growth, but it requires targeted investments, better infrastructure, and long-term planning to address productivity issues and properly use its competitive advantages. |

| [83] | Fishery Production | Field Surveys | A multidisciplinary approach was used to classify 20 different fishery production systems into 10 different groups based on ecological, economic, social, technological, and political factors, showing the complexity of artisanal fishing in the area and providing useful information for customized management and development strategies. |

| [84] | Fishery Production system | Grouping Analysis | The “RAPFISH” methodology was used to evaluate 20 fishery production systems off the coast of Pará, Brazil, and three main groups were identified: industrial and semi-industrial fisheries that show economic and social sustainability, large-scale artisanal fisheries that show ecological sustainability, and small-scale artisanal fisheries. Some of the recommendations are reducing industrial fishing activities, implementing licensing quotas, funding research for semi-industrial and large-scale artisanal fisheries, offering financial incentives for small-scale artisanal fisheries, and encouraging stakeholder involvement in decision-making. |

| [85] | Inclusive growth | Content analysis | While a consensus definition of inclusive growth is still hard to find, it is clear from a review of ADB’s well-founded knowledge products that it is generally understood to mean “growth with equal opportunities” including economic, social, and institutional aspects. Major suggestions emphasize the need of interdisciplinary strategies, such as the encouragement of sustainable economic growth, guaranteeing fair political involvement, and supporting social safety nets and capacity-building initiatives to promote inclusive growth and development. |

| [86] | Aquaculture production | Case studies | The research emphasizes that while compartmentalization offers a promising strategy for disease management, its successful implementation in aquaculture depends on aligning with the specific production system and disease epidemiology, implying that it may not be universally applicable, and underscores the importance of integrating HACCP principles for effective biosecurity in compartmentalized systems. Moreover, the study explores the valuable role of compartmentalization in addressing and managing aquaculture disease emergencies.. |

| [87] | Agriculture, forestry, and fishing | Case studies, SLR | The study indicates that worker protection in the Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing (AgFF) sector is considerably limited, with regulatory protections weaker than in other industrial sectors and enforcement being insufficient. The vulnerability of AgFF workers is aggravated by immigration policies, and the sector’s workforce has historically experienced legal “exceptionalism,” resulting in the exclusion of many regulatory protections specifically designed to secure workers in other industries. |

| [88] | Capital Labour | Mathematical analysis | The study confirms the presence of a unique marginal rate of technological substitution under optimal capital-labor conditions and establishes a practical procedure for finding the optimal capital-labor ratio in any two-factor production function, grounded in microeconomic theory, where the marginal rate of technological substitution is set to one unit, relying on an accurate representation of key enterprise dynamics. |

| [89] | Trade openness | New endogenous growth model | The study introduces a novel trade openness index and employs a multifaceted approach, revealing that while human and physical capital positively influence long-term economic growth in India, trade openness has a negative long-term impact, with short-term positive effects, and granger causality tests support the existence of trade openness-led and human capital-led growth hypotheses. |

| [90] | Ecological Footprint | Statistical analysis | The study presents a methodological framework for calculating ecological footprints associated with leisure tourism in the Seychelles, highlighting the environmental impact of air travel, and raises important questions about the potential role of long-distance travel in safeguarding biodiversity, emphasizing the need for sustainable tourism practices. |

| [91] | Renewable Energy Utilization | Systematic literature review (SLR) | The study provides a comprehensive overview of island energy resources, investigates the current utilization status and development potential of various renewable energy sources for island power grids, and presents advanced technologies and strategies to improve the penetration of renewables, highlighting the increasing importance of sustainable energy solutions for island communities. |

2.2. Contribution of the Study

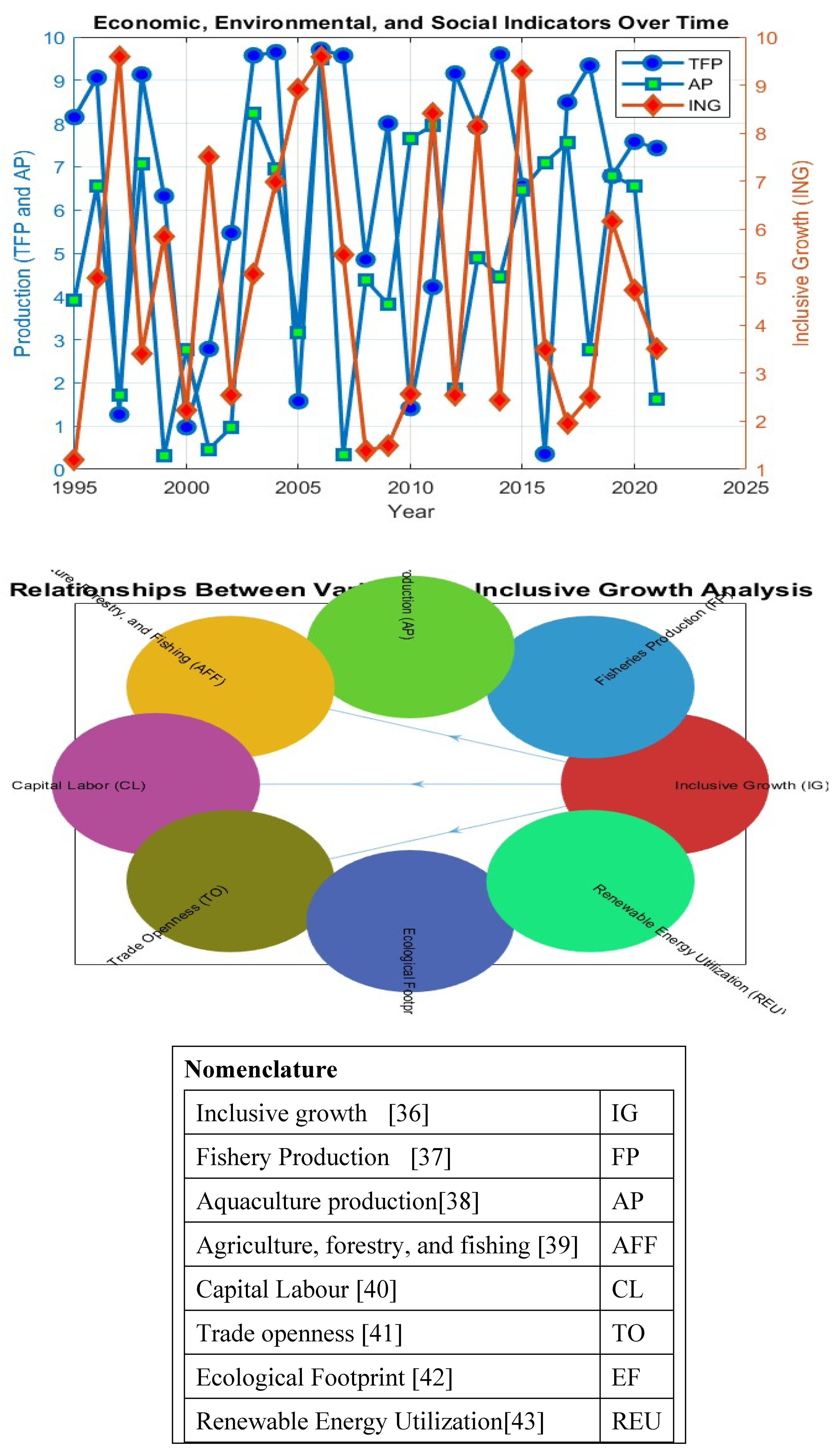

3. Materials and Methods

- Econometric Methods

- Panel Heteroscedasticity Test

- Panel Autocorrelation Test

- Panel Unit Root (CIPS) Test

- Panel Cointegration test of Westerlund

- Long-run Estimation Method

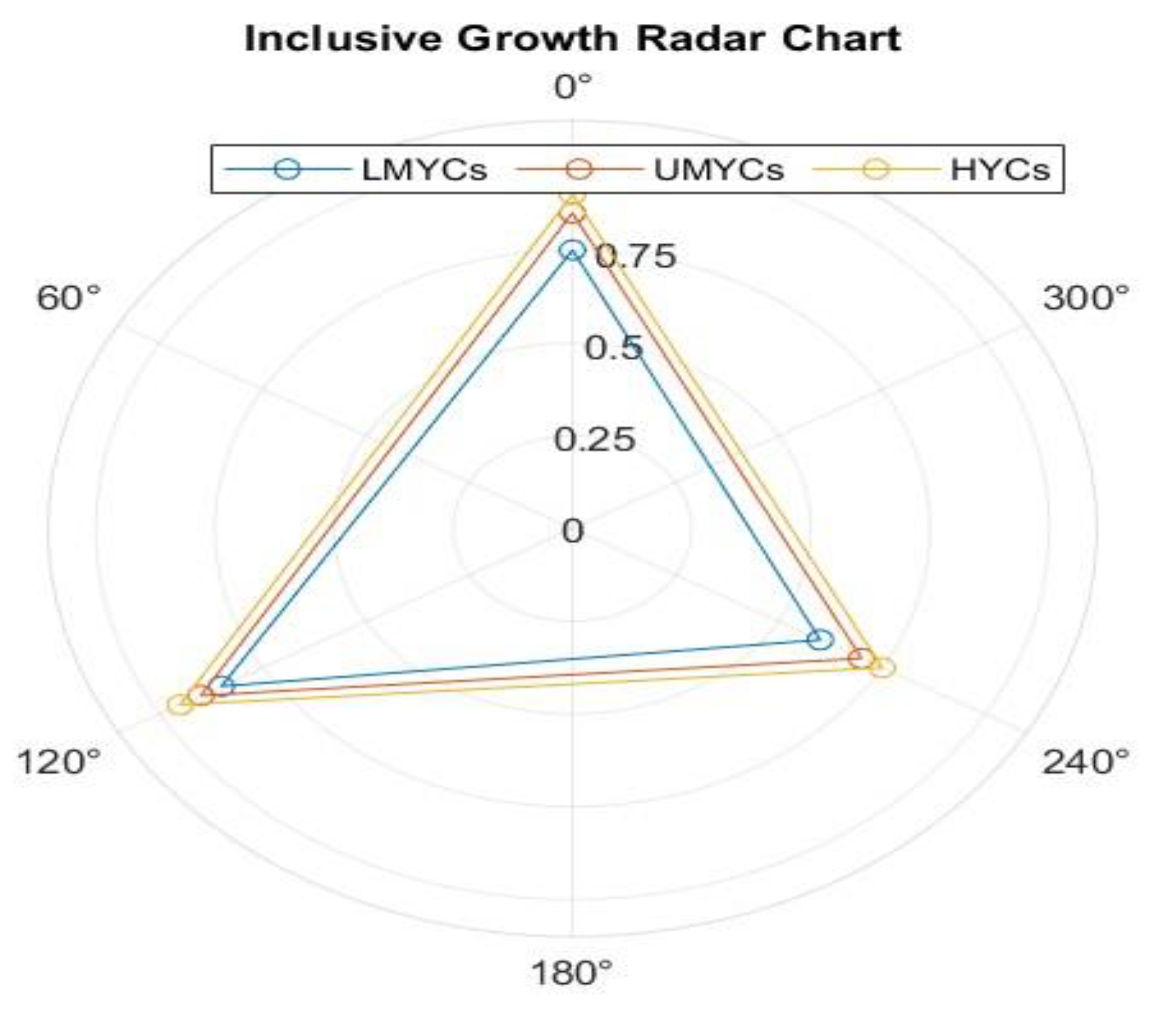

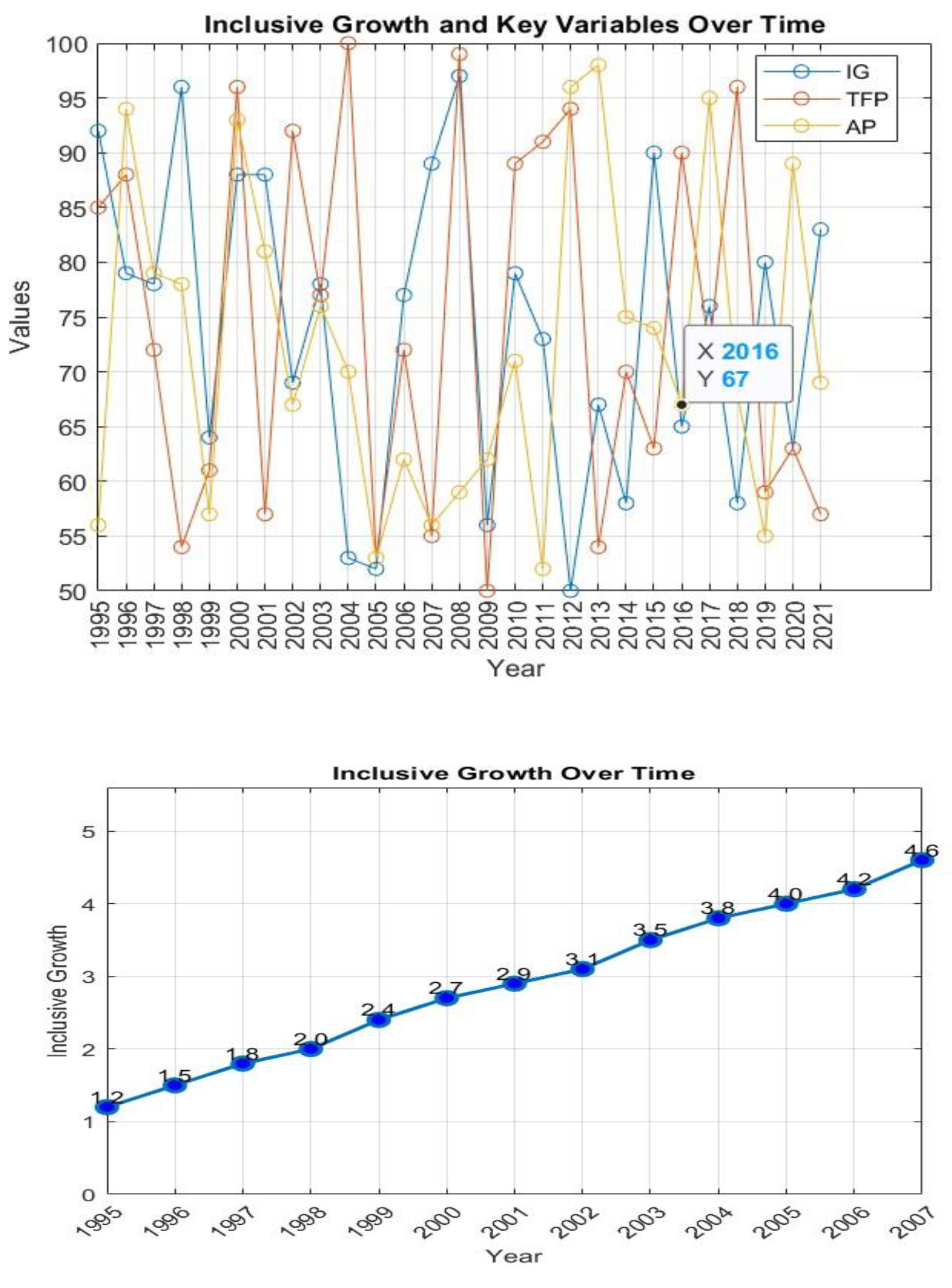

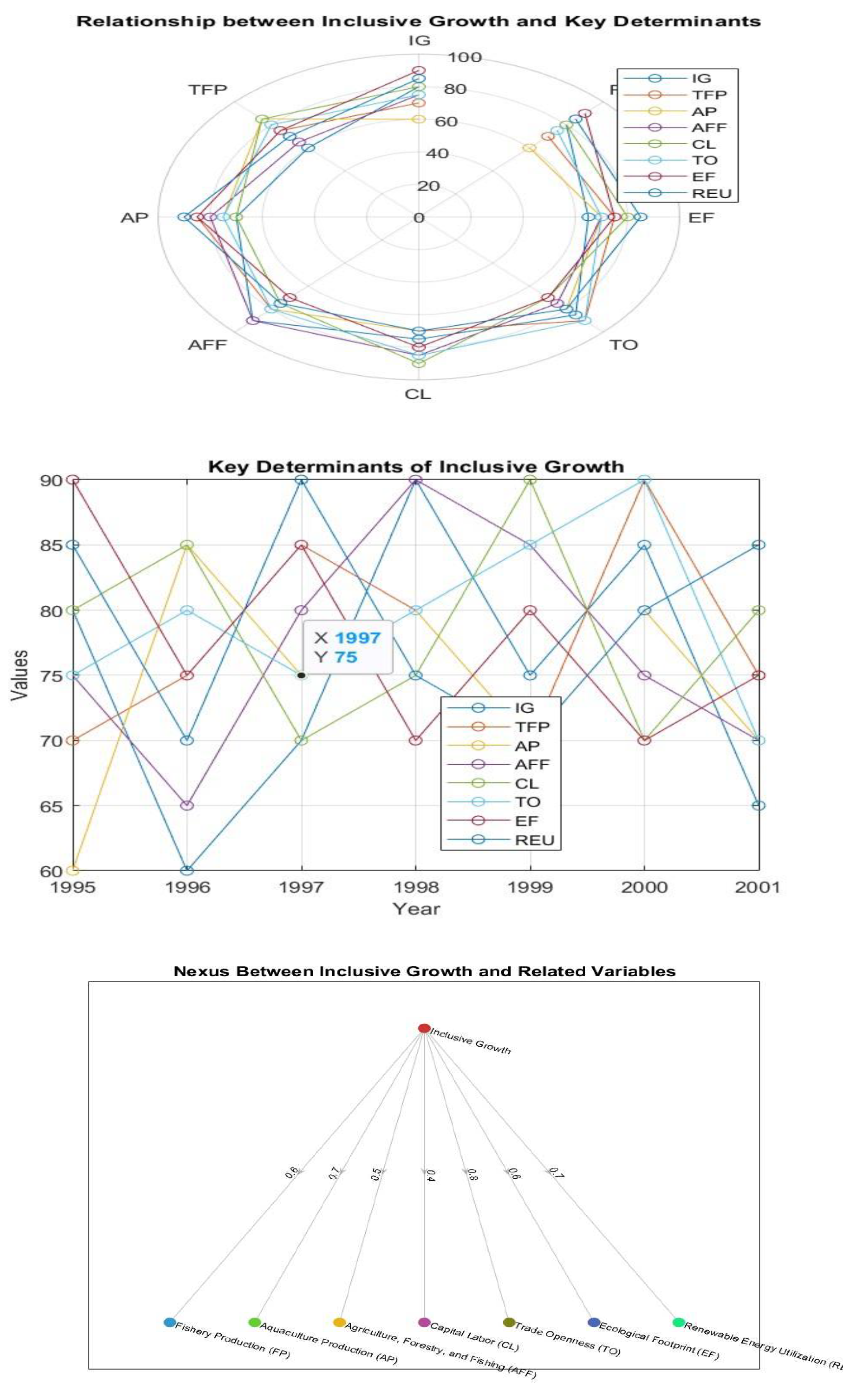

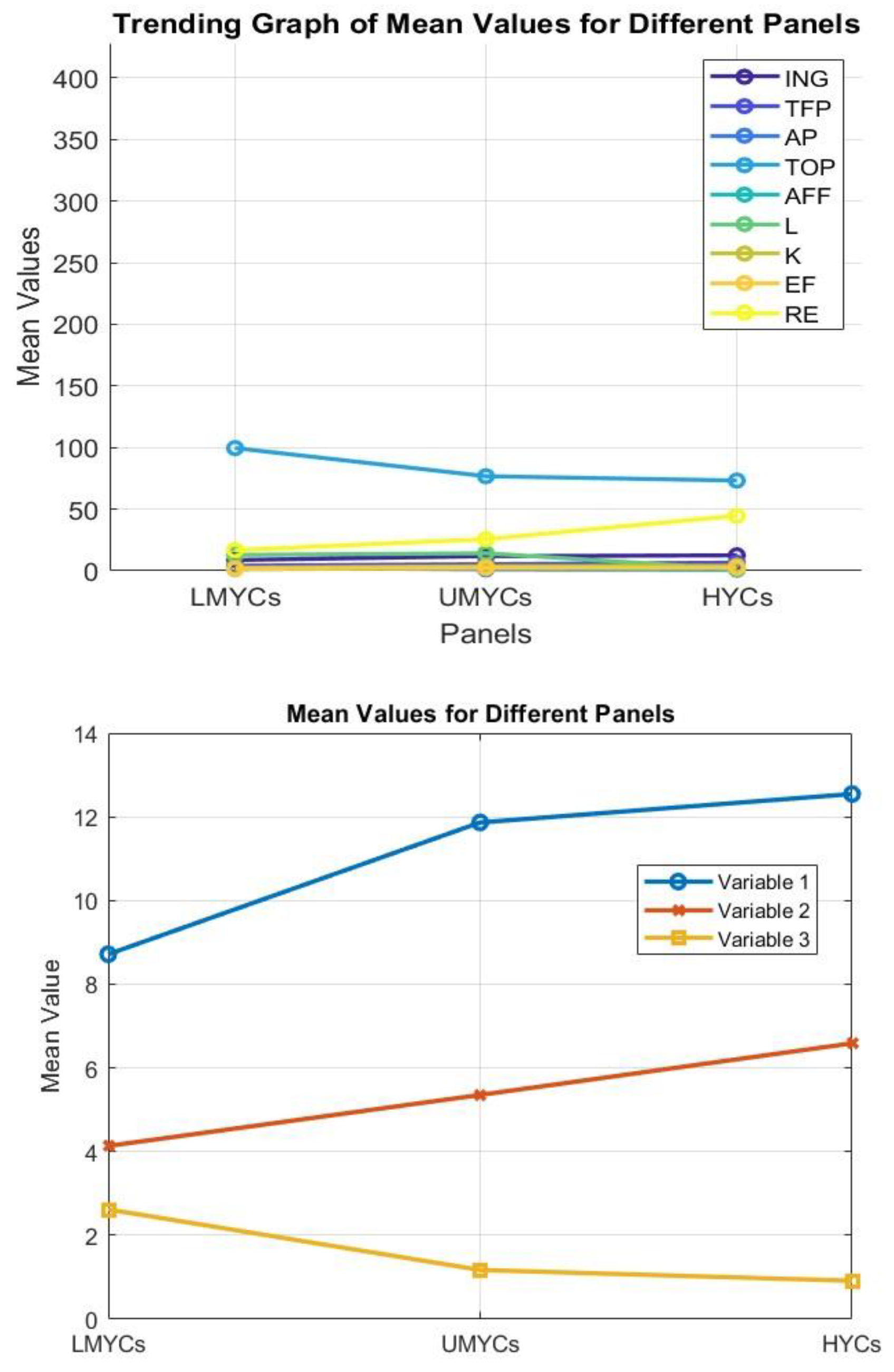

| Panel | Mean | Min | Max | Sd. Dev. | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusive Growth (ING) (GDP per person employed) | |||||

| LMYCs | 8.715 | 6.234 | 9.768 | 0.456 | W.D.I. |

| UMYCs | 11.865 | 9.245 | 12.564 | 0.501 | |

| HYCs | 12.545 | 11.231 | 13.453 | 0.392 | |

| Total Fishery Production (TFP) (metric tonnes) | |||||

| LMYCs | 4.134204 | 1.80672 | 4.615417 | 0.43924 | W.D.I. |

| UMYCs | 5.352802 | 2.649245 | 5.610105 | 0.356066 | |

| HYCs | 6.586513 | 4.445568 | 5.60746 | 0.026144 | |

| Aquaculture production (AP) (metric tonnes.) | |||||

| LMYCs | 2.6166512 | -10.94238 | 3.78219 | 1.261692 | W.D.I. |

| UMYCs | 1.169859 | -6.25558 | 4.29876 | 1.237899 | |

| HYCs | 0.9107528 | -7.198535 | 6.107207 | 1.59848 | |

| Trade Openness (TOP) (% of GDP.) | |||||

| LMYCs | 99.56 | 14.564 | 423.234 | 65.563 | W.D.I. |

| UMYCs | 76.754 | 13.522 | 218.543 | 34.677 | |

| HYCs | 73.234 | 0.154 | 178.354 | 33.453 | |

| Agriculture, forestry, and fishing (AFF (% of GDP.) | |||||

| LMYCs | 1.322114 | -3.963077 | 9.169629 | 1.40004 | W.D.I. |

| UMYCs | 2.24804 | -3.962927 | 7.510115 | 1.55605 | |

| HYCs | 1.282795 | -4.012442 | 4.854778 | 1.386042 | |

| Labour (L) in (millions) | |||||

| LMYCs | 12.877 | 4.742 | 22.456 | 5.772 | W.D.I. |

| UMYCs | 14.216712 | -1.386294 | 3.65842 | 0.7304148 | |

| HYCs | 1.461135 | -0.3581045 | 3.313094 | 0.5508925 | |

| Capital (K) (in USD) | |||||

| LMYCs | 24.592 | 1.000 | 70.433 | 6.612 | W.D.I. |

| UMYCs | 25.432 | 3.011 | 46.420 | 4.433 | |

| HYCs | 21.583 | 10.064 | 41.533 | 5.153 | |

| Total ecological footprint (EF)(Global hectares per capita) | |||||

| LMYCs | 1.603 | -0.823 | 3.421 | 0.664 | W.D.I. |

| UMYCs | 2.312 | -1.065 | 3.546 | 0.654 | |

| HYCs | 2.543 | -0.234 | 3.213 | 0.590 | |

| Renewable Energy Utilization (RE) (% of total final energy use) | |||||

| LMYCs | 16.751 | 0.000 | 82.654 | 16.152 | W.D.I. |

| UMYCs | 25.687 | 1.263 | 86.045 | 18.432 | |

| HYCs | 44.673 | 0.015 | 92.661 | 28.654 | |

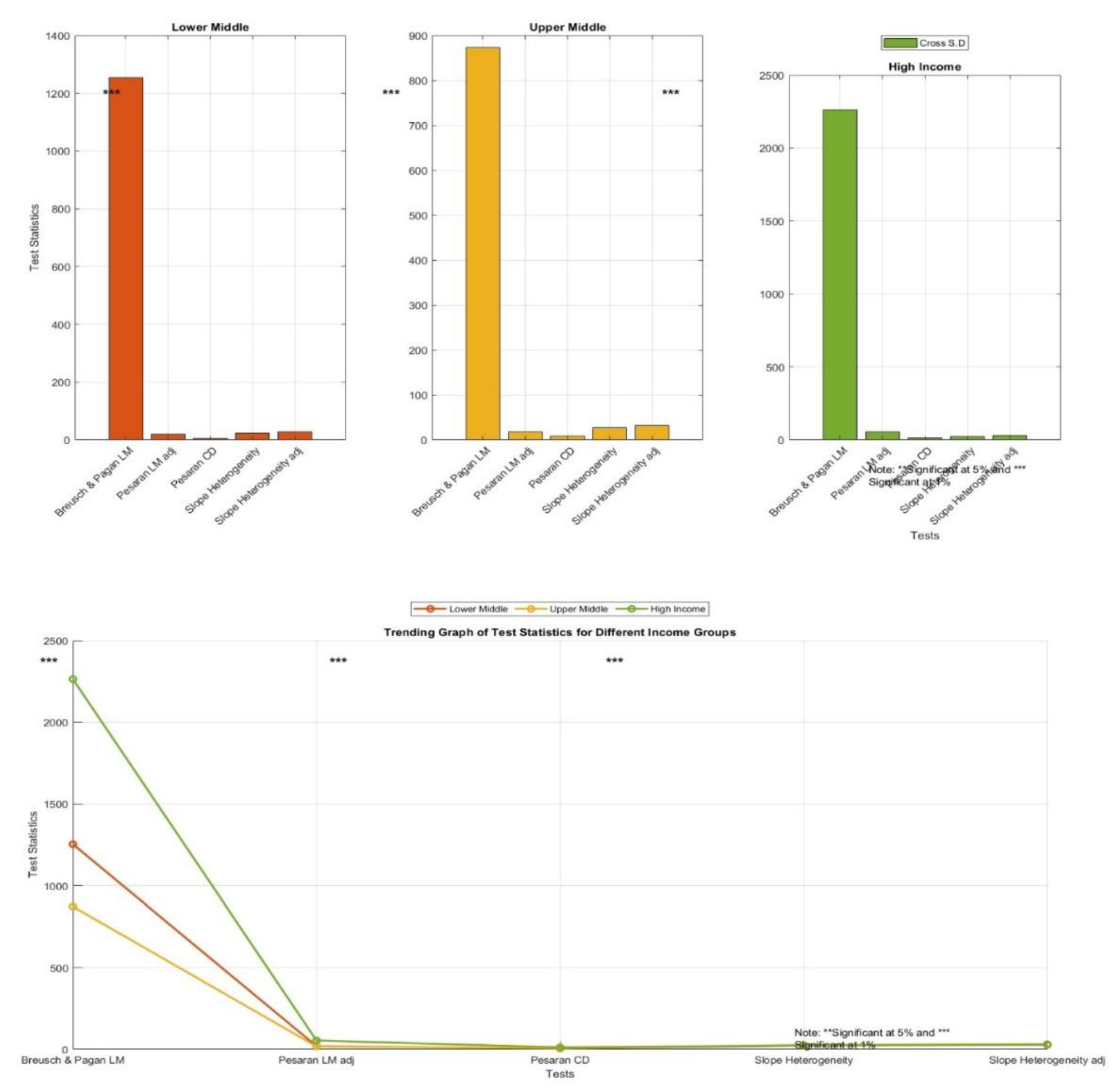

| Problem | Test | Lower Middle | Upper middle | High Income | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test.stat. | Prob. | Test.stat. | Prob. | Test.stat. | Prob. | ||

| Cross S.D | Breusch & Pagan LM | 1254*** | 0.00 | 873.6*** | 0.000 | 2264*** | 0.000 |

| Pesaran LM adj | 19.94*** | 0.000 | 18.33*** | 0.000 | 54.58*** | 0.000 | |

| Pesaran CD | 6.107*** | 0.000 | 8.127*** | 0.000 | 12.52*** | 0.000 | |

| Slope Heterogeneity | ∆ | 23.671*** | 0.000 | 26.940*** | 0.000 | 24.025*** | 0.000 |

| ∆^ adj | 28.449*** | 0.000 | 32.378*** | 0.000 | 31.37*** | 0.000 | |

|

Heteroscedasticity Autocorrelation |

Modified Wald Breusch-Pagan /Cook-Weisberg Wooldridge |

21889.68* 14.06*** 228.93*** |

0.000 0.000 0.000 |

11466.28* 7.55*** 12.786*** |

0.000 0.000 0.000 |

32884.53* 44.82*** 208.76*** |

0.000 0.000 0.000 |

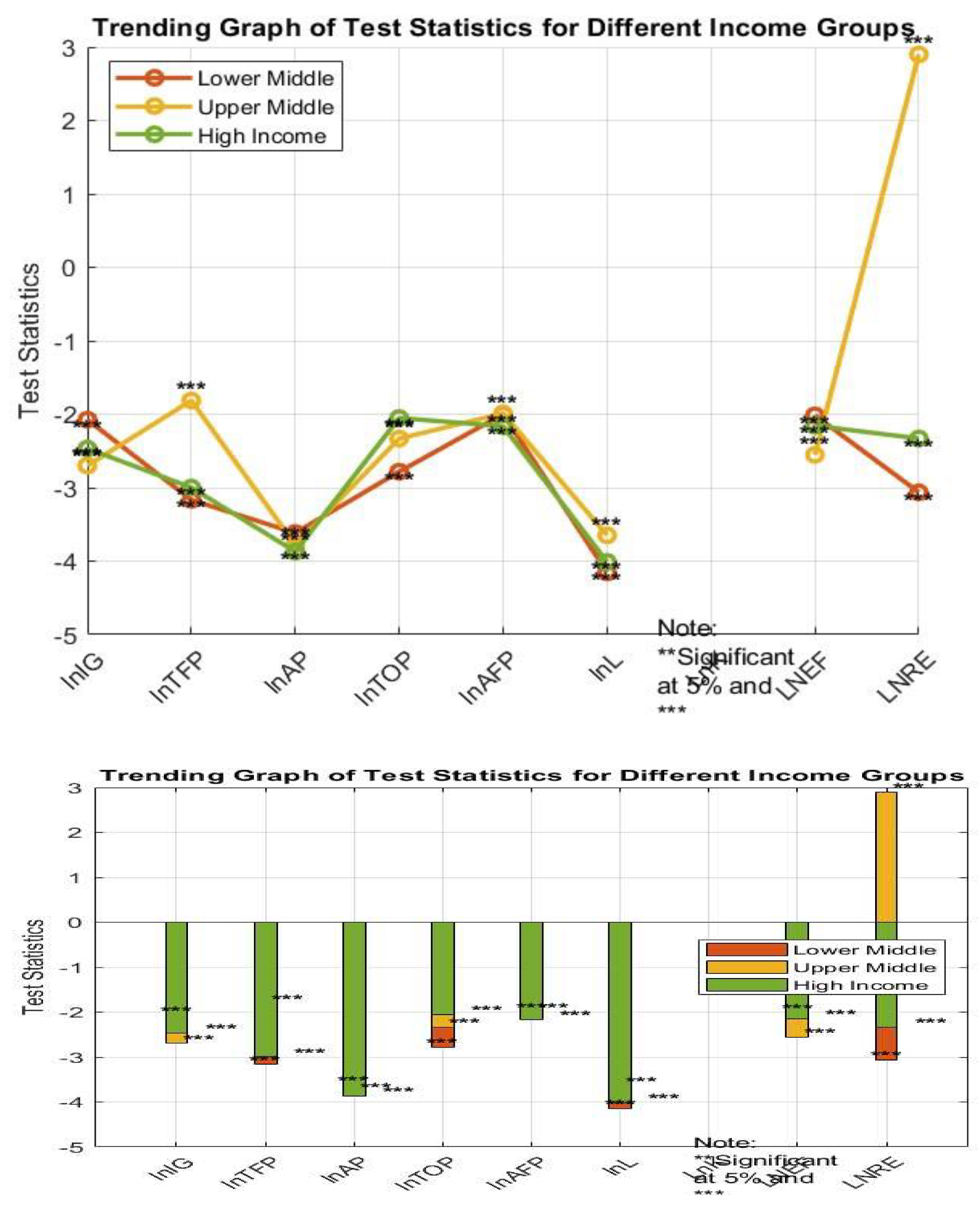

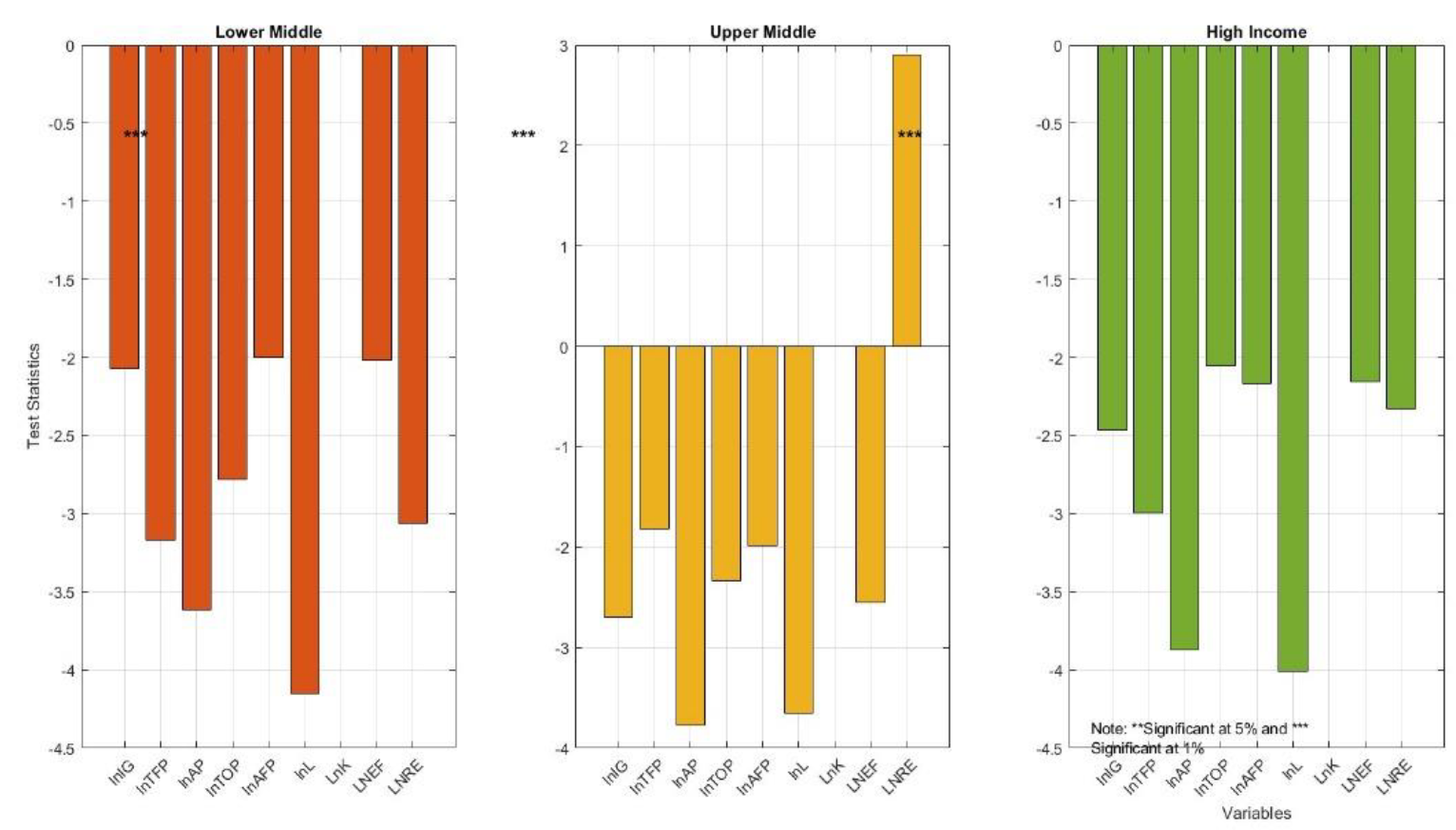

| Variables | Lower Middle | Upper Middle | High Income |

|---|---|---|---|

| At level (Intercept & Trend) | |||

| lnIG | -2.074 | -2.699** | -2.466 |

| lnTFP | -3.166*** | -1.813 | -2.998*** |

| lnAP | -3.616*** | -3.777*** | -3.870*** |

| lnTOP | -2.782*** | -2.332 | -2.051 |

| lnAFP | -1.998 | -1.988 | -2.164 |

| lnL | -4.153*** | -3.648*** | -4.010*** |

| LnK LNEF LNRE |

-2.015 -3.063*** -2.156*** |

-1.977 -2.552 2.899 |

-2.330 -3.457*** 2.443** |

| At first difference (only with intercept) | |||

| lnIG | -3.522 *** | -3.817*** | -4.047*** |

| lnTFP | -4.818*** | -3.426*** | -3.787*** |

| lnAP | -5.286*** | -5.595*** | -5.726*** |

| lnTOP | -4.365*** | -4.094*** | -3.775*** |

| lnAFP | -4.239*** | -3.968*** | -4.504*** |

| lnL | -5.725*** | -5.652*** | -5.705*** |

| LnK LNEF LNRE |

-4.165*** -3.22*** |

-3.707*** 3.456*** |

-3.251*** 3.111*** |

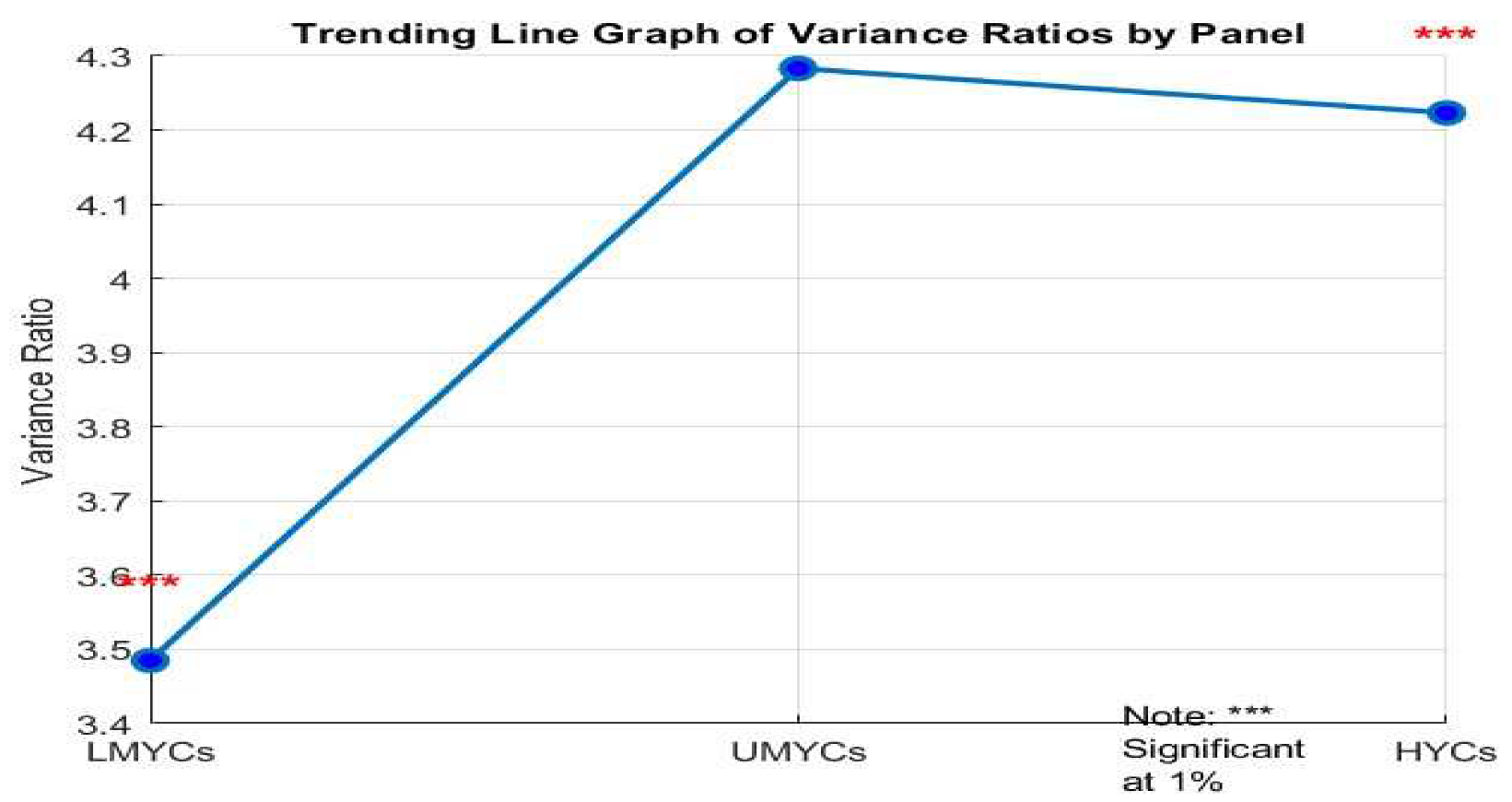

| Panel | Variance Ratio | |

|---|---|---|

| Statis. | Prob. | |

| LMYCs | 3.485** | 0.0005 |

| UMYCs | 4.283*** | 0.0000 |

| HYCs | 4.223*** | 0.0000 |

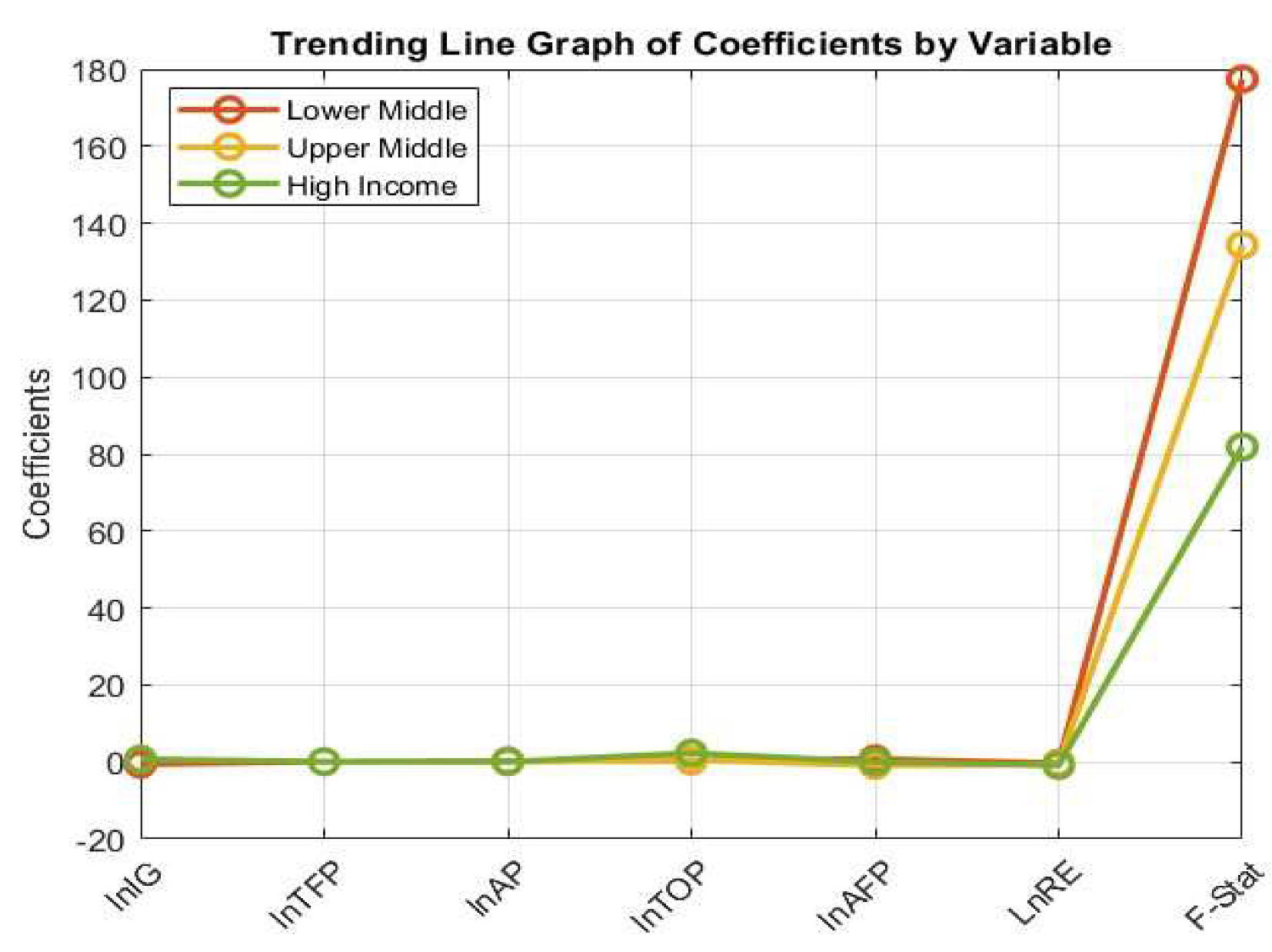

| Variables | High Income | Lower Middle | Upper Middle | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coff. | Std. Er. | Prob. | Coef. | Std. Er. | Prob. | Coef. | Std. Er. | Prob. | |

| lnIG | 0.535*** | 0.055 | 0 | 0.682*** | 0.053 | 0 | 0.736*** | 0.689 | 0.001 |

| lnTFP | 0.077** | 0.015 | 0.059 | 0.099 | 0.006** | 0.086 | -0.015 | 0.004 | 0.128 |

| lnAP | 0.232*** | 0.031 | 0 | 0.053** | 0.033 | 0.055 | 0.222*** | 0.041 | 0.008 |

| lnTOP | 0.345*** | 0.09 | 0.006 | 0.544*** | 0.248 | 0 | 2 | 296***0.083 | 0.002 |

| lnAFP | 0.788** | 0.004 | 0.08 | -0.889** | 0.009 | 0.017 | 0.0234*** | 0.011 | 0.007 |

| LnRE | -0.345*** | 0.005 | 0.03 | -0.576*** | 0.003 | 0.012 | 0.896*** | 0.01 | 0.005 |

| F-Stat | 177.44*** (0.000) | 134.29*** (0.000) | 81.89***(0.000) | ||||||

| R2 | 0.566 | 0.678 | 0.36 | ||||||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cichowicz, E.; Rollnik-Sadowska, E. Inclusive growth in CEE countries as a determinant of sustainable development. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, M.P.; Jeyacheya, J.; Long, P.H. Can tourism promote inclusive growth? Supply chains, ownership and employment in Ha Long Bay, Vietnam. The Journal of Development Studies 2018, 54, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouzet, D.; Sánchez, A.C.; Renault, T.; Roehn, O. Fiscal challenges and inclusive growth in ageing societies. 2019.

- Mirzoev, T.; Tull, K.I.; Winn, N.; Mir, G.; King, N.V.; Wright, J.M.; Gong, Y.Y. Systematic review of the role of social inclusion within sustainable urban developments. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 2022, 29, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Aldaco, R.; Ruiz, I.; Margallo, M.; Laso, J.; Hoehn, D. Deliverable Title: D4. 1.1 State of the art report of the seafood sector in the European Atlantic area. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor, R.L.; Hardy, R.W.; Buschmann, A.H.; Bush, S.R.; Cao, L.; Klinger, D.H.; Little, D.C.; Lubchenco, J.; Shumway, S.E.; Troell, M. A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature 2021, 591, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, W.C.; Kimpara, J.M.; Preto, B.d.L.; Moraes-Valenti, P. Indicators of sustainability to assess aquaculture systems. Ecological indicators 2018, 88, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESCAP, U. Fast-tracking the SDGs: driving Asia-Pacific transformations. 2020.

- Cho, K.M.; Lee, H.Y.; Cho, D.Y.; Jung, J.G.; Kim, M.J.; Jeong, J.B.; Jang, S.-N.; Lee, G.O.; Sim, H.-S.; Kang, M.J. Comprehensive Comparison of Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Panax ginseng Sprouts by Different Cultivation Systems in a Plant Factory. Plants 2022, 11, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S.; Estim, A.; Shapawi, R. Future-proofing oceans for food security and poverty alleviation. In Decent Work and Economic Growth, Springer: 2020; pp. 462-472.

- Berchin, I.I.; Nunes, N.A.; de Amorim, W.S.; Zimmer, G.A.A.; da Silva, F.R.; Fornasari, V.H.; Sima, M.; de Andrade, J.B.S.O. The contributions of public policies for strengthening family farming and increasing food security: The case of Brazil. Land use policy 2019, 82, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Lu, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, S.; Xu, X.; Hua, H.; Chen, L.; Zhao, K.; Xu, Q. Effects of preoperative frailty on outcomes following surgery among patients with digestive system tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2021, 47, 3040–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma Serrano, M.; Picón-Berjoyo, A.; Calvo-Mora, A. Business and sustainable development goals (SDGs): a bibliometric analysis [Dataset]. 2022.

- Zeng, L.; Zeng, L. Conceptual analysis of China’s belt and road initiative: A road towards a regional community of common destiny. Contemporary International law and china’s peaceful development.

- Raihan, A. A review on the integrative approach for economic valuation of forest ecosystem services. Journal of Environmental Science and Economics 2023, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picatoste, X.; Novo-Corti, I.; Tî rcǎ, D.M. Human Development Index as an Indicator of Social Welfare. In No Poverty, Springer: 2021; pp. 449-459.

- Ojea, E.; Lester, S.E.; Salgueiro-Otero, D. Adaptation of fishing communities to climate-driven shifts in target species. One Earth 2020, 2, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, N.; Zeufack, A.G. Unlocking East Asian Markets to Sub-Saharan Africa. Africa in the New Trade Environment Market Access in Troubled Times 2022, 135–185. [Google Scholar]

- Takyi, S.A.; Amponsah, O.; Yeboah, A.S.; Mantey, E. Locational analysis of slums and the effects of slum dweller’s activities on the social, economic and ecological facets of the city: insights from Kumasi in Ghana. GeoJournal 2021, 86, 2467–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrancea, L.M.; Rathnaswamy, M.M.; Rus, M.-I.; Tulai, H. Determinants of economic growth for the last half of century: A panel data analysis on 50 countries. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 2022, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremen, C.; Merenlender, A.M. Landscapes that work for biodiversity and people. Science 2018, 362, eaau6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, S.; Al-Awadhi, T.; Al Nasiri, N.; Al Balushi, A. Modernization and female labour force participation in Oman: spatial modelling of local variations. Annals of GIS 2022, 28, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W. Convergence success and the middle-income trap. The Developing Economies 2020, 58, 30–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguinetti, P.; Moncarz, P.; Vaillant, M.; Allub, L.; Juncosa, F.; Barril, D.; Cont, W.; Lalanne, Á. Pathways to integration: trade facilitation, infrastructure, and global value chains. CAF: 2022.

- Korinek, A.; Stiglitz, J.E. Artificial intelligence and its implications for income distribution and unemployment. In The economics of artificial intelligence: An agenda, University of Chicago Press: 2018; pp. 349-390.

- Świąder, M.; Szewrański, S.; Kazak, J.K.; Van Hoof, J.; Lin, D.; Wackernagel, M.; Alves, A. Application of ecological footprint accounting as a part of an integrated assessment of environmental carrying capacity: A case study of the footprint of food of a large city. Resources 2018, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Jahanger, A.; Ahmad, P. Are Mercosur economies going green or going away? An empirical investigation of the association between technological innovations, energy use, natural resources and GHG emissions. Gondwana Research 2023, 113, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensland, A. 2021 Global Agricultural Productivity Report: Climate for Agricultural Growth. 2021 Global Agricultural Productivity Report: Climate for Agricultural Growth, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, A.; Basurto, X.; Virdin, J.; Lin, X.; Betances, S.J.; Smith, M.D.; Allison, E.H.; Best, B.A.; Brownell, K.D.; Campbell, L.M. Recognize fish as food in policy discourse and development funding. Ambio 2021, 50, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Nhamo, L.; Mpandeli, S.; Nhemachena, C.; Senzanje, A.; Sobratee, N.; Chivenge, P.P.; Slotow, R.; Naidoo, D.; Liphadzi, S. The water–energy–food nexus as a tool to transform rural livelihoods and well-being in Southern Africa. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019, 16, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.N.; Marquez, G.P.B.; Deng, H.; Iu, A.; Fabella, M.; Salonga, R.B.; Ashardiono, F.; Cartagena, J.A. A review on urban agriculture: technology, socio-economy, and policy. Heliyon 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, C.; te Velde, D.W. Structural transformation, economic development and industrialization in post-Covid-19 Africa; Institute for New Economic Thinking: New York, NY, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Aghion, P.; Hasanov, F.; Cherif, R. Competition, innovation, and inclusive growth. 2021.

- Guo, Q.; Wang, Y.; Dong, X. Effects of smart city construction on energy saving and CO2 emission reduction: Evidence from China. Applied Energy 2022, 313, 118879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongomin, O.; Nziu, P. A critical review on the development and utilization of energy systems in Uganda. The Scientific World Journal 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abor, J.Y.; Amidu, M.; Issahaku, H. Mobile telephony, financial inclusion and inclusive growth. Journal of African Business 2018, 19, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, C.M.; Thorson, J.T.; Pinsky, M.L.; Oken, K.L.; Wiedenmann, J.; Jensen, O.P. Impacts of historical warming on marine fisheries production. Science 2019, 363, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botta, R.; Asche, F.; Borsum, J.S.; Camp, E.V. A review of global oyster aquaculture production and consumption. Marine Policy 2020, 117, 103952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingelschmidt, J.; Milner, A.; Khireddine-Medouni, I.; Witt, K.; Alexopoulos, E.C.; Toivanen, S.; LaMontagne, A.D.; Chastang, J.-F.; Niedhammer, I. Suicide among agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health.

- Graham, M.; Anwar, M. Labour. 2019.

- Jun, W.; Mahmood, H.; Zakaria, M. Impact of trade openness on environment in China. Journal of Business Economics and Management 2020, 21, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Irum, A.; Malik, I.A.; Ashraf, A.; Rongqiong, L.; Liu, G.; Ullah, H.; Ali, M.U.; Yousaf, B. Ecological footprint of Rawalpindi; Pakistan's first footprint analysis from urbanization perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 170, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg-Sitton, S.M.; Boardman, R.; Rabiti, C.; O'Brien, J. Reimagining future energy systems: Overview of the US program to maximize energy utilization via integrated nuclear-renewable energy systems. International Journal of Energy Research 2020, 44, 8156–8169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E. On the sustainability of smart and smarter cities in the era of big data: an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary literature review. Journal of Big Data 2019, 6, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praharaj, S.; Han, J.H.; Hawken, S. Towards the right model of smart city governance in India. Sustainable Development Studies 2018, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, S.; Yamahata, C. ASEAN and Regional Actors in the Indo-Pacific, Springer Nature, 2023.

- Morales-Muñoz, H.; Jha, S.; Bonatti, M.; Alff, H.; Kurtenbach, S.; Sieber, S. Exploring connections—Environmental change, food security and violence as drivers of migration—A critical review of research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.C.; Bisht, I.S. Reviving Smallholder Hill Farming by Involving Rural Youth in Food System Transformation and Promoting Community-Based Agri-Ecotourism: A Case of Uttarakhand State in North-Western India. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.L.; Farhat, K. Regulation of platform market access by the United States and China: Neo-mercantilism in digital services. Policy & Internet 2022, 14, 348–367. [Google Scholar]

- Saqib, N.; Ozturk, I.; Usman, M. Investigating the implications of technological innovations, financial inclusion, and renewable energy in diminishing ecological footprints levels in emerging economies. Geoscience Frontiers 2023, 14, 101667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Pretorius, J.H.C.; Gupta, S.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Role of institutional pressures and resources in the adoption of big data analytics powered artificial intelligence, sustainable manufacturing practices and circular economy capabilities. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2021, 163, 120420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Q.; Cao, N.D.; Gounopoulos, D.; Newton, D. Environmental concern, regulations and board diversity. Review of Corporate Finance 2023, 3, 99–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, A. Parachuters vs. climbers: Economic consequences of barriers to political entry in a democracy. Job Market Paper, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, N. Inclusive growth in cities: A sympathetic critique. Regional Studies 2019, 53, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Q.; Jian, C. Natural resource endowment, institutional quality and China's regional economic growth. Resources Policy 2020, 66, 101644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Übler, H.D.; Genzel, R.; Wisnioski, E.; Schreiber, N.M.F.; Shimizu, T.T.; Price, S.H.; Tacconi, L.J.; Belli, S.; Wilman, D.J.; Fossati, M. The Evolution and Origin of Ionized Gas Velocity Dispersion from $ z\sim2. 6$ to $ z\sim0. 6$ with KMOS $^{\rm 3D} $. arXiv, 2019; arXiv:1906.02737 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, A.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, J.; Tal, A.; Juneja, R. From Food Scarcity to Surplus; Springer: 2021.

- Balami, S.; Sharma, A.; Karn, R. Significance of nutritional value of fish for human health. Malaysian Journal of Halal Research 2019, 2, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Carpio, X.; Cuesta, J.A.; Kugler, M.D.; Hernández, G.; Piraquive, G. What effects could global value chain and digital infrastructure development policies have on poverty and inequality after COVID-19? Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2022, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.; Baste, I.; Larigauderie, A.; Leadley, P.; Pascual, U.; Baptiste, B.; Demissew, S.; Dziba, L.; Erpul, G.; Fazel, A. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany.

- Allioui, H.; Mourdi, Y. Exploring the Full Potentials of IoT for Better Financial Growth and Stability: A Comprehensive Survey. Sensors 2023, 23, 8015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, V.; Di Lernia, C. Climate and carnism: Regulatory pathways towards a sustainable food system. UNSWLJ 2022, 45, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Blythe, J.; White, C.S.; Campero, C. Blue growth and blue justice: Ten risks and solutions for the ocean economy. Marine Policy 2021, 125, 104387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ramady, H.; Brevik, E.C.; Bayoumi, Y.; Shalaby, T.A.; El-Mahrouk, M.E.; Taha, N.; Elbasiouny, H.; Elbehiry, F.; Amer, M.; Abdalla, N. An overview of agro-waste management in light of the water-energy-waste nexus. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.B. Overcoming global food security challenges through science and solidarity. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 2021, 103, 422–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraca, B.; Neuber, F. Viable and convivial technologies: Considerations on Climate Engineering from a degrowth perspective. Journal of cleaner production 2018, 197, 1810–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meckling, J.; Allan, B.B. The evolution of ideas in global climate policy. Nature Climate Change 2020, 10, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Hook, A.; Martiskainen, M.; Brock, A.; Turnheim, B. The decarbonisation divide: contextualizing landscapes of low-carbon exploitation and toxicity in Africa. Global Environmental Change 2020, 60, 102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, K.; Lahiani, A.; Roubaud, D. Natural resources as blessings and finance-growth nexus: A bootstrap ARDL approach in an emerging economy. Resources Policy 2019, 60, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombi, M. Modeling the material stock of manufactured capital with production function. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2018, 138, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beegle, K.; Honorati, M.; Monsalve, E. Reaching the poor and vulnerable in Africa through social safety nets. Realizing the full potential of social safety nets in Africa 2018, 1, 49–86. [Google Scholar]

- Group, W.B. Democratic Republic of Congo Systematic Country Diagnostic: Policy Priorities for Poverty Reduction and Shared Prosperity in a Post-Conflict Country and Fragile State; World Bank: 2018.

- Arvin, M.B.; Pradhan, R.P.; Nair, M. Uncovering interlinks among ICT connectivity and penetration, trade openness, foreign direct investment, and economic growth: The case of the G-20 countries. Telematics and Informatics 2021, 60, 101567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidenfeld, A. Tourism diversification and its implications for smart specialisation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L. The World Trade Organization and the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement: Analog Trade Rules in a Digital Era. In Big Tech Firms and International Relations: The Role of the Nation-State in New Forms of Power, Springer: 2022; pp. 93-114.

- Franko, P. The puzzle of Latin American economic development; Rowman & Littlefield, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kalair, A.; Abas, N.; Saleem, M.S.; Kalair, A.R.; Khan, N. Role of energy storage systems in energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables. Energy Storage 2021, 3, e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.; Obaideen, K.; Elsaid, K.; Wilberforce, T.; Sayed, E.T.; Maghrabie, H.M.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Assessment of the pre-combustion carbon capture contribution into sustainable development goals SDGs using novel indicators. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 153, 111710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammi, B.; Khatoun, R.; Zeadally, S.; Fayad, A.; Khoukhi, L. IoT technologies<? show [AQ ID= Q1]?> for smart cities. IET networks 2018, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Khuong, P.M.; Fichtner, W. Urbanisation and renewable energies in ASEAN: multi-disciplinary approaches to analysing past and future trends.

- Dolek, H. Between Patriarchy and Occupation: Joyful Encounters, Intimate Politics and Endurance in Hebron. University of Sheffield, 2021.

- Raitzer, D.; Wong, L.C.; Samson, J.N. Myanmar's agriculture sector: unlocking the potential for inclusive growth. Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentes, B.; Isaac, V.J.; Espírito-Santo, R.V.d.; Frédou, T.; Almeida, M.C.d.; Mourão, K.R.M.; Frédou, F.L. Multidisciplinary approach to identification of fishery production systems on the northern coast of Brazil. Biota Neotropica 2012, 12, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, V.; Santo, R.; Bentes, B.; Frédou, F.; Mourão, K.; Frédou, T. An interdisciplinary evaluation of fishery production systems off the state of Pará in North Brazil. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 2009, 25, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauniyar, G.; Kanbur, R. Inclusive growth and inclusive development: A review and synthesis of Asian Development Bank literature. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 2010, 15, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, C.; Jones, J.; Zagmutt, F. Compartmentalisation in aquaculture production systems. 2008.

- Chapman, L.J.; Husberg, B. Agriculture, forestry, and fishing sector. Journal of Safety Research 2008, 39, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yankovyi, O.; Goncharov, Y.; Koval, V.; Lositska, T. OPTIMIZATION OF THE CAPITAL-LABOR RATIO ON THE BASIS OF PRODUCTION FUNCTIONS IN THE ECONOMIC MODEL OF PRODUCTION. Scientific Bulletin of National Mining University 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hye, Q.M.A.; Lau, W.-Y. Trade openness and economic growth: empirical evidence from India. Journal of Business Economics and Management 2015, 16, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Hansson, C.B.; Hörstmeier, O.; Saggel, S. Ecological footprint analysis as a tool to assess tourism sustainability. Ecological economics 2002, 43, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, B.; Li, C.; Cao, Y.; Li, L.; Zeng, L. A review of renewable energy utilization in islands. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 59, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shambaugh, D. International relations of Asia; Rowman & Littlefield, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Majeed, A.; Ahmad, M.; Rasheed, M.F.; Khan, M.K.; Popp, J.; Olah, J. The dynamic impact of financial globalization, environmental innovations and energy productivity on renewable energy consumption: evidence from advanced panel techniques. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 894857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Cui, X.; Li, Q. Global action on SDGs: Policy review and outlook in a post-pandemic era. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Q. The effect of change in main economic factors in China and OECD countries. Szent István Egyetem (2000-2020), 2018.

- Shurety, A.L.; Bartelet, H.A.; Chawla, S.; James, N.L.; Lapointe, M.; Zoeller, K.C.; Chua, C.M.; Cumming, G.S. Insights from twenty years of comparative research in Pacific Large Ocean States. Ecosystems and People 2022, 18, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, A.; Zizka, A.; Carvalho, F.A.; Scharn, R.; Bacon, C.D.; Silvestro, D.; Condamine, F.L. Amazonia is the primary source of Neotropical biodiversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 6034–6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handisyde, N.; Telfer, T.C.; Ross, L.G. Vulnerability of aquaculture-related livelihoods to changing climate at the global scale. Fish and Fisheries 2017, 18, 466–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeleke, B.S. Assessment of Productivity and supply chain of aquaculture projects in Gauteng province for sustainable operation. 2017.

- Borozan, D.; Starcevic, D.P. European energy industry: Managing operations on the edge of efficiency. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 116, 109401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Nketiah, E.; Obuobi, B.; Adjei, M. Trade Openness, Inflation and GDP Growth: Panel Data Evidence from Nine (9) West Africa Countries. Open Journal of Business and Management 2019, 8, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, A.; Baris-Tuzemen, O.; Uzuner, G.; Ozturk, I.; Sinha, A. Revisiting the role of renewable and non-renewable energy consumption on Turkey’s ecological footprint: Evidence from Quantile ARDL approach. Sustainable cities and society 2020, 57, 102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.; Mihardjo, L.W.; Sharif, A.; Jermsittiparsert, K. The role of tourism and renewable energy in testing the environmental Kuznets curve in the BRICS countries: fresh evidence from methods of moments quantile regression. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 39427–39441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onakoya, A.; Johnson, B.; Ogundajo, G. Poverty and trade liberalization: empirical evidence from 21 African countries. Economic research-Ekonomska istraživanja 2019, 32, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILORI, O.O.; TANIMOWO, F.O. Heteroscedasticity Detection in Cross-Sectional Diabetes Pedigree Function: A Comparison of Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey, Harvey and Glejser Tests. 2022.

- Wiedermann, W.; Artner, R.; von Eye, A. Heteroscedasticity as a basis of direction dependence in reversible linear regression models. Multivariate Behavioral Research 2017, 52, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushita, Y.; Otsu, T. A jackknife Lagrange multiplier test with many weak instruments. Econometric Theory 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeabah, D.; Gyeke-Dako, A.; Andoh, C. Board gender diversity, corporate governance and bank efficiency in Ghana: a two stage data envelope analysis (DEA) approach. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 2019, 19, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flandrin, P. Explorations in time-frequency analysis, Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Sharif, A.; Raza, S.A.; Ozturk, I.; Afshan, S. The dynamic relationship of renewable and nonrenewable energy consumption with carbon emission: a global study with the application of heterogeneous panel estimations. Renewable energy 2019, 133, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhelkhal, A. Energy use, economic growth and CO2 emissions in Africa: does the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis exist? New evidence from heterogeneous panel under cross-sectional dependence. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2022, 24, 13083–13110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, S. Analyzing Crime Dynamics and Investigating the Great American Crime Decline. The University of Toledo, 2022.

- Moulder, R.G.; Boker, S.M.; Ramseyer, F.; Tschacher, W. Determining synchrony between behavioral time series: An application of surrogate data generation for establishing falsifiable null-hypotheses. Psychological methods 2018, 23, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanal, A. The role of ICT and energy consumption on carbon emissions: An Australian evidence using cointegration test and ARDL long-run and short-run methodology. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy 2021, 11, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatemi-J, A. Hidden panel cointegration. Journal of King Saud University-Science 2020, 32, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, U. Examining the role of financial inclusion towards CO2 emissions: presenting the role of renewable energy and globalization in the context of EKC. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 15946–15954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fromentin, V. The long-run and short-run impacts of remittances on financial development in developing countries. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 2017, 66, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akadiri, A.C.; Gungor, H.; Akadiri, S.S.; Bamidele-Sadiq, M. Is the causal relation between foreign direct investment, trade, and economic growth complement or substitute? The case of African countries. Journal of Public Affairs 2020, 20, e2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, U.; Shan, W.; Wang, J.-j.; Amin, A. Outward foreign direct investment and economic growth in China: Evidence from asymmetric ARDL approach. Journal of Business Economics and Management 2018, 19, 706–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, W.; Mallik, G.; Nghiem, X.-H.; Sinha, A.; Vo, X.V. Is green finance really “green”? Examining the long-run relationship between green finance, renewable energy and environmental performance in developing countries. Renewable Energy 2023, 208, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellink, R.; Chateau, J.; Lanzi, E.; Magné, B. Long-term economic growth projections in the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Global Environmental Change 2017, 42, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade, M.; Rossouw, J.; Gwatidzo, T. Determinants of tax revenue performance in the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Economic Research Southern Africa, working paper 2018, 762. [Google Scholar]

- Tugcu, C.T. Panel data analysis in the energy-growth nexus (EGN). The economics and econometrics of the energy-growth nexus, Elsevier, 2018; 255–271. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y.; Si, C.; Zhang, S.; Sarwar, S. Impact of urbanization on energy intensity by adopting a new technique for regional division: evidence from China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2018, 25, 36102–36116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.M.; Alam, K. Life expectancy in the ANZUS-BENELUX countries: The role of renewable energy, environmental pollution, economic growth and good governance. Renewable Energy 2022, 190, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Zhang, W.; Ding, Y.; Shen, R.; Jiang, Z.; Lu, X.; Li, X. In situ fabrication of robust cocatalyst-free CdS/g-C3N4 2D–2D step-scheme heterojunctions for highly active H2 evolution. Solar Rrl 2020, 4, 1900423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNown, R.; Sam, C.Y.; Goh, S.K. Bootstrapping the autoregressive distributed lag test for cointegration. Applied Economics 2018, 50, 1509–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Makhdum, M.S.A.; Anwar, S.; Yaseen, M.R. Climate Change Vulnerability, Adaptation, and Feedback Hypothesis: A Comparison of Lower-Middle, Upper-Middle, and High-Income Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Seker, F.; Bulbul, S. Investigating the impacts of energy consumption, real GDP, tourism and trade on CO2 emissions by accounting for cross-sectional dependence: a panel study of OECD countries. Current Issues in Tourism 2017, 20, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xiang, P.; Chen, Y.-J.; Xie, X.; Li, Y. Unit of analysis: Impact of Silverman and Solmon’s article on field-based intervention research in physical education in the USA. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 2017, 36, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanov, F.J.; Liddle, B.; Mikayilov, J.I. The impact of international trade on CO2 emissions in oil exporting countries: Territory vs consumption emissions accounting. Energy Economics 2018, 74, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Silge, J. Tidy modeling with R; O'Reilly Media, Inc., 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Callens, B.; Cargnel, M.; Sarrazin, S.; Dewulf, J.; Hoet, B.; Vermeersch, K.; Wattiau, P.; Welby, S. Associations between a decreased veterinary antimicrobial use and resistance in commensal Escherichia coli from Belgian livestock species (2011–2015). Preventive veterinary medicine 2018, 157, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gao, S.; Li, S.; Feng, K. Strategizing the relation between urbanization and air pollution: Empirical evidence from global countries. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 243, 118615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S. Comparative R squared. Available at SSRN 3790200 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Computer Science 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, R.; Wood, G.A.; Whelan, S.; Cigdem-Bayram, M.; Atalay, K.; Dodson, J. Inquiry into housing policies, labour force participation and economic growth. 2017.

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Singer, D. Financial inclusion and inclusive growth: A review of recent empirical evidence. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Saud, S.; Haseeb, A.; Chen, S.; Li, H. The role of information and communication technology and financial development in shaping a low-carbon environment: a Belt and Road journey toward development. Information Technology for Development 2023, 29, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, R.; Deng, Q.; Tillaguango, B.; Méndez, P.; Bravo, D.; Chamba, J.; Alvarado-Lopez, M.; Ahmad, M. Do economic development and human capital decrease non-renewable energy consumption? Evidence for OECD countries. Energy 2021, 215, 119147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anser, M.K.; Syed, Q.R.; Lean, H.H.; Alola, A.A.; Ahmad, M. Do economic policy uncertainty and geopolitical risk lead to environmental degradation? Evidence from emerging economies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Danish, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. The dynamic linkage between information and communication technology, human development index, and economic growth: evidence from Asian economies. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2019, 26, 26982–26990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayatilleke, K. Challenges in implementing surveillance tools of high-income countries (HICs) in low middle income countries (LMICs). Current treatment options in infectious diseases 2020, 12, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles, J.; Prebble, M.; Wen, J.; Hart, C.; Schuttenberg, H. Advancing gender in the environment: gender in fisheries-a sea of opportunities. IUCN and USAID. Washington, USA: USAID. 68pp.

- Raihan, A.; Tuspekova, A. Dynamic impacts of economic growth, energy use, urbanization, agricultural productivity, and forested area on carbon emissions: New insights from Kazakhstan. World Development Sustainability 2022, 1, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sour, O.; Maliki, S.B.; Benghalem, A. Modelling the Interconnection Between Technological Leadership and the Level of Use of Information and Communication Technologies. 2023.

- Musah, M.; Kong, Y.; Mensah, I.A.; Antwi, S.K.; Donkor, M. The connection between urbanization and carbon emissions: a panel evidence from West Africa. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2021, 23, 11525–11552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, H.; Khan, I.; Alharthi, M.; Zafar, M.W.; Saeed, A. Sustainable energy policy, socio-economic development, and ecological footprint: The economic significance of natural resources, population growth, and industrial development. Utilities Policy 2023, 81, 101490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mueller, V. Coastal climate change, soil salinity and human migration in Bangladesh. Nature climate change 2018, 8, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriithi, L.N. Adoption of Selected Climate Smart Agriculture Technologies among Smallholder Farmers in Lower Eastern Kenya. University of Embu, 2021.

- Canh, P.N.; Schinckus, C.; Dinh Thanh, S. What are the drivers of shadow economy? A further evidence of economic integration and institutional quality. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 2021, 30, 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, Y.; Lee, H.S.; Trung, B.H.; Tran, H.-D.; Lall, M.K.; Kakar, K.; Xuan, T.D. Impacts of mainstream hydropower dams on fisheries and agriculture in lower Mekong Basin. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Ullrich, P.; Shu, L. Using convolutional neural networks for streamflow projection in California. Frontiers in Water 2020, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Colantonio, E.; Gattone, S.A. Relationships between renewable energy consumption, social factors, and health: A panel vector auto regression analysis of a cluster of 12 EU countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, M. Renewable energy for sustainable development in India: current status, future prospects, challenges, employment, and investment opportunities. Energy, Sustainability and Society 2020, 10, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).