Submitted:

05 November 2023

Posted:

06 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Taxon Sampling

2.2. DNA Extraction

2.3. Molecular Markers, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

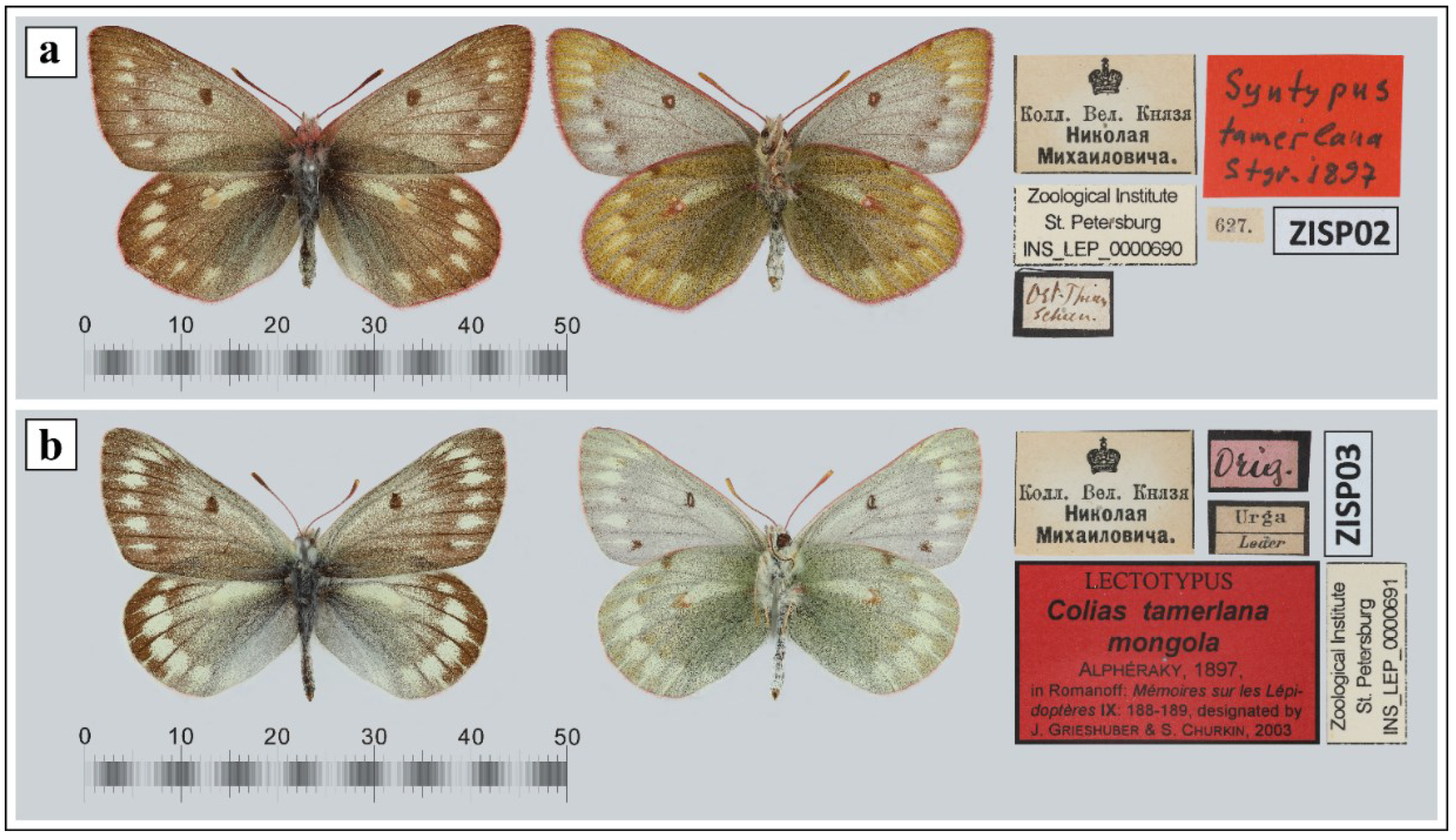

2.4. Processing and Sequencing of Old Type Specimens

2.5. Detection of Wolbachia Endosymbionts

2.6. Molecular Data Analysis and Phylogenetic Reconstructions

2.6.1. Molecular Characterization of Wolbachia

2.7. Data Availability

3. Results

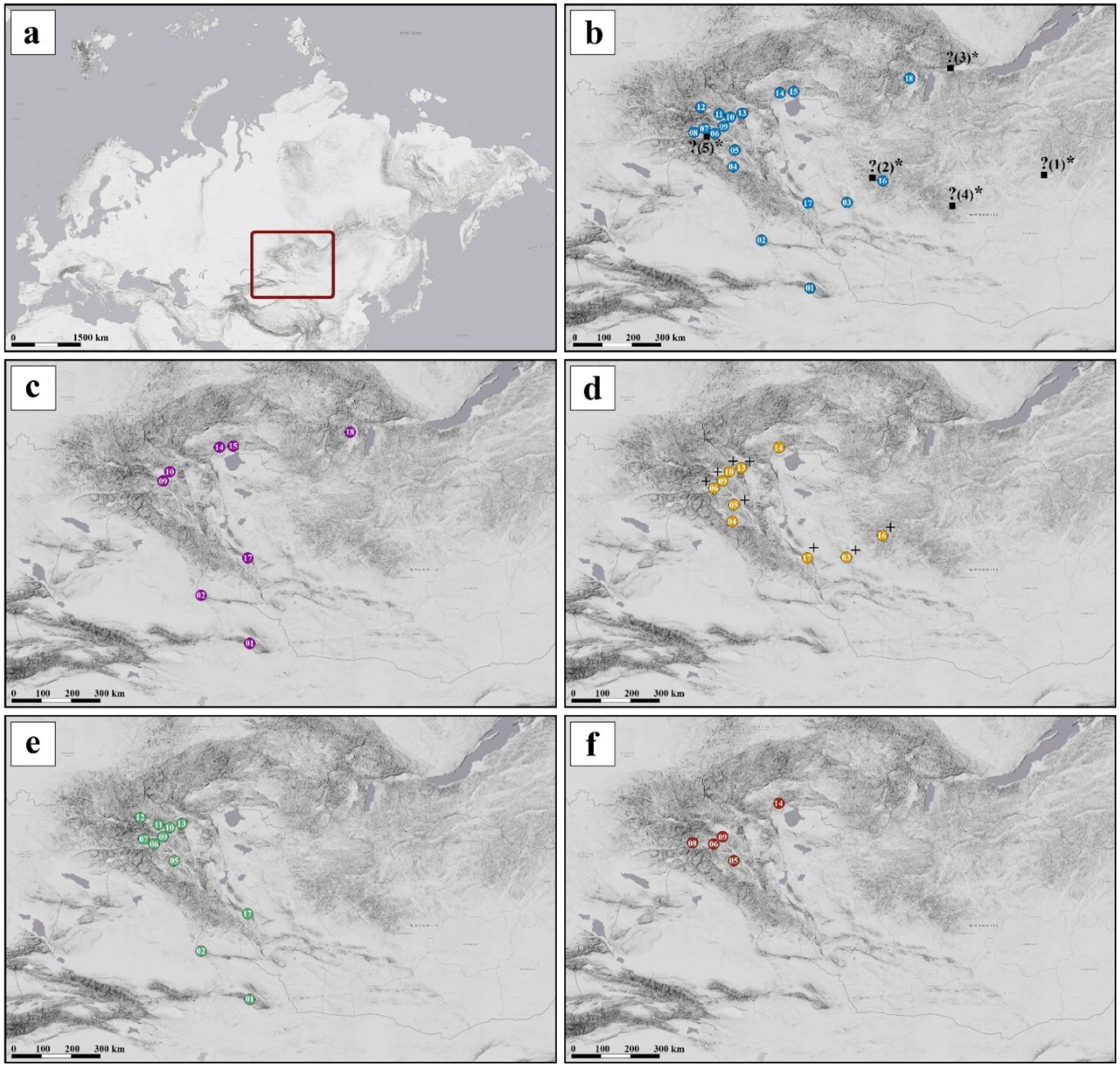

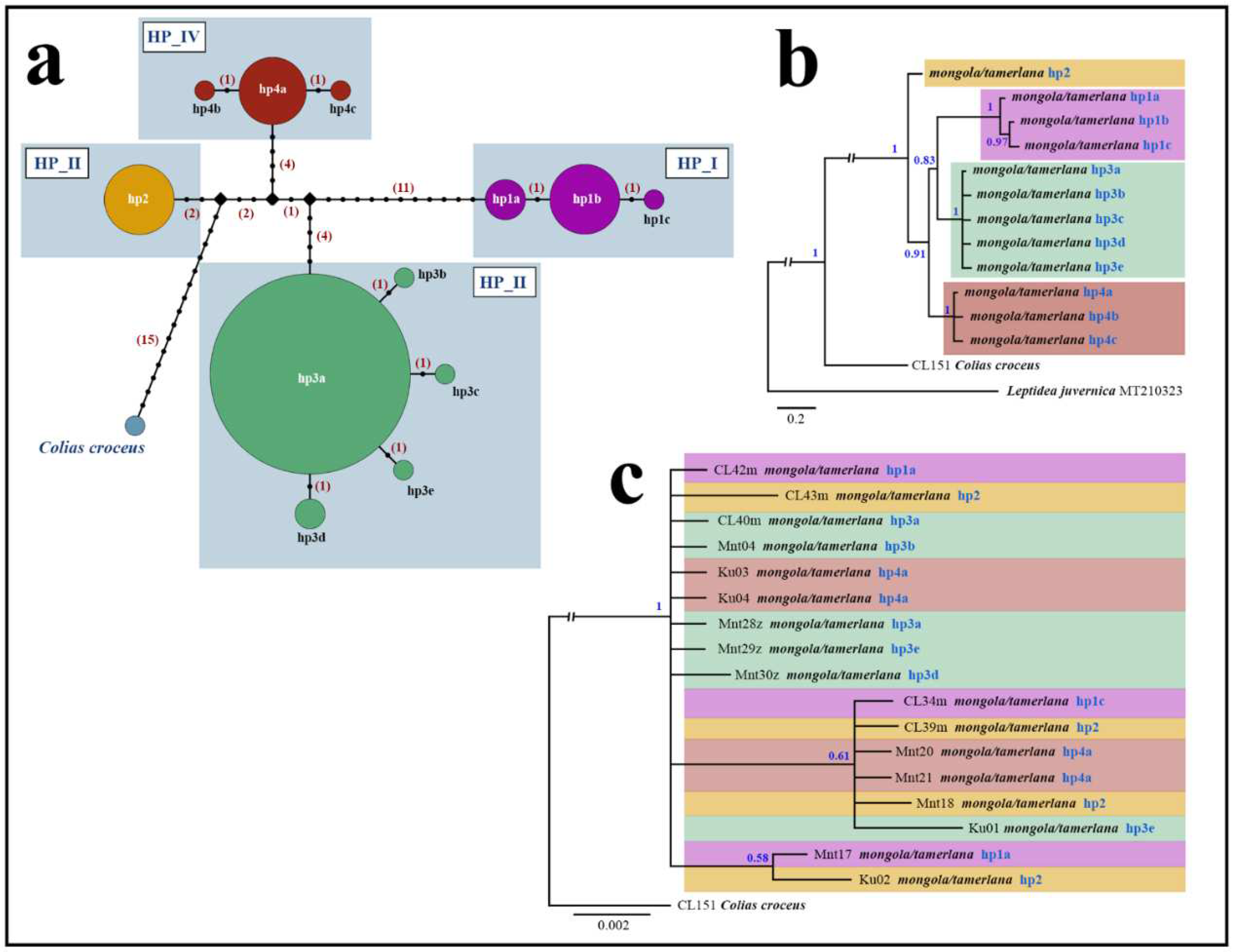

3.1. Phylogeographic Structure of Colias mongola and Colias tamerlana

3.2. Phylogenetic Analyses of Mitochondrial and Nuclear Markers

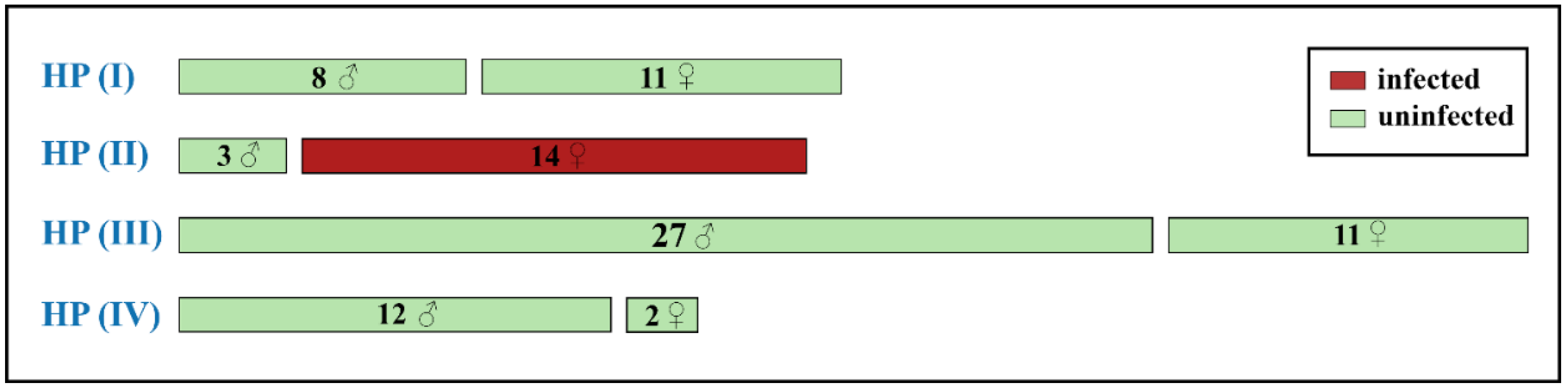

3.3. Wolbachia Analysis

3.3.1. Wolbachia Allele Identified in C. mongola/C. tamerlana

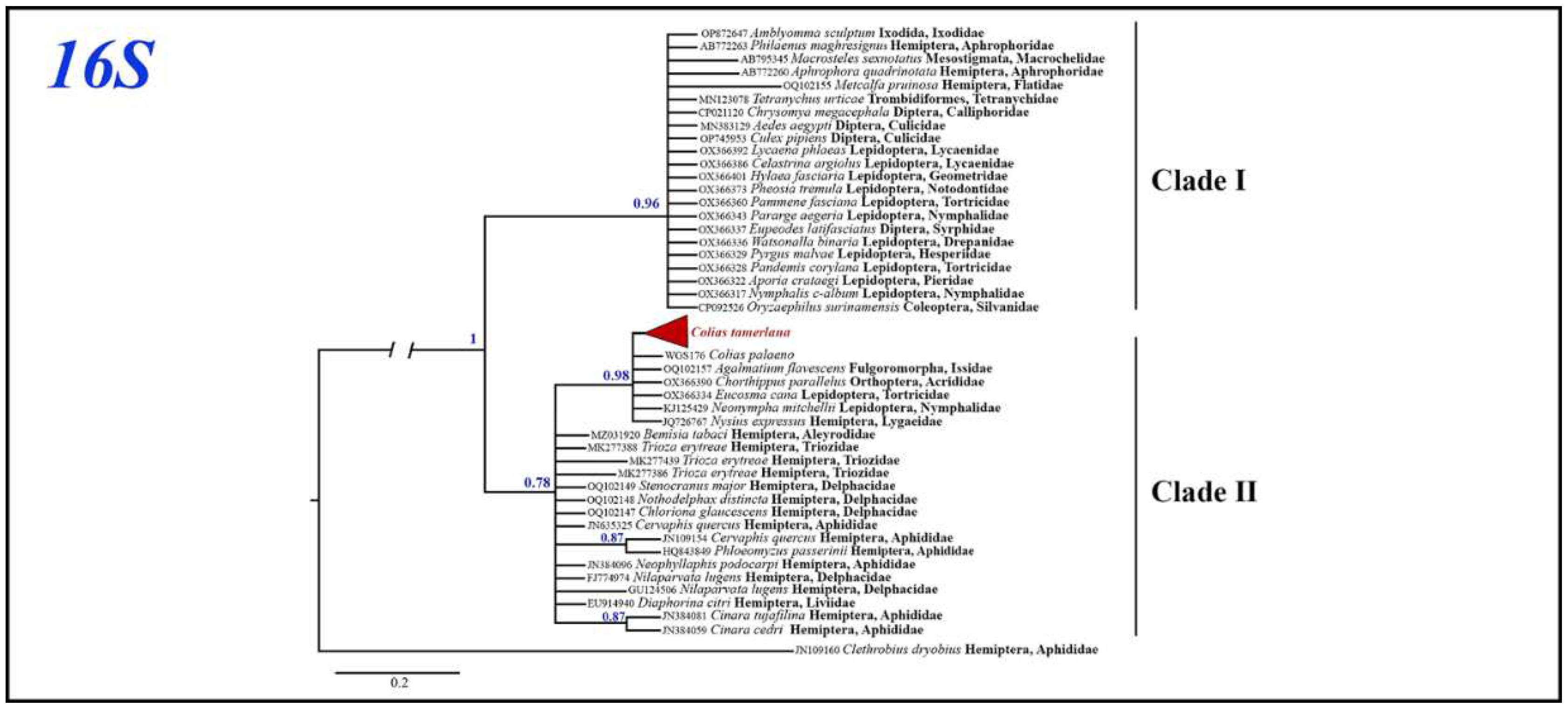

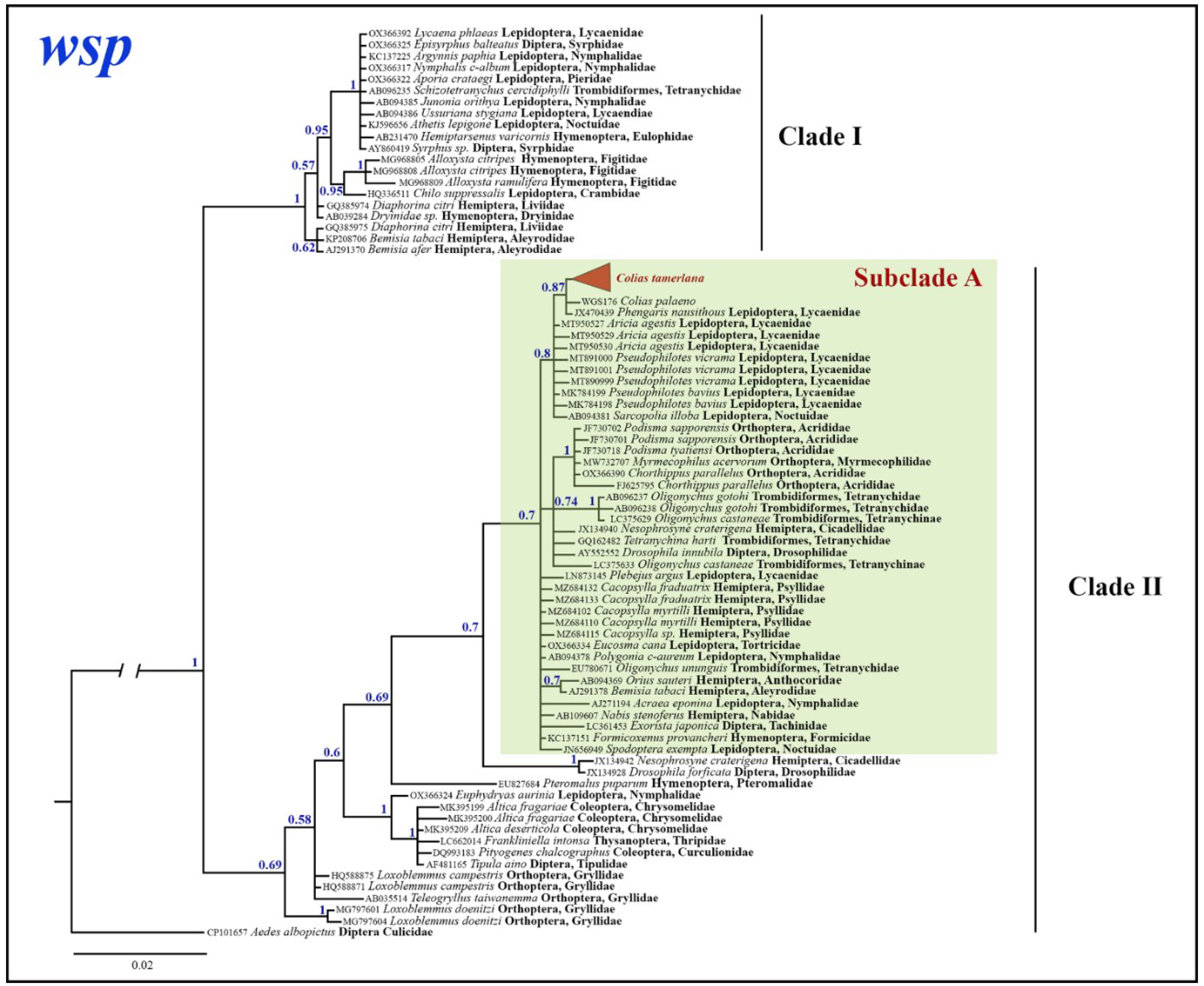

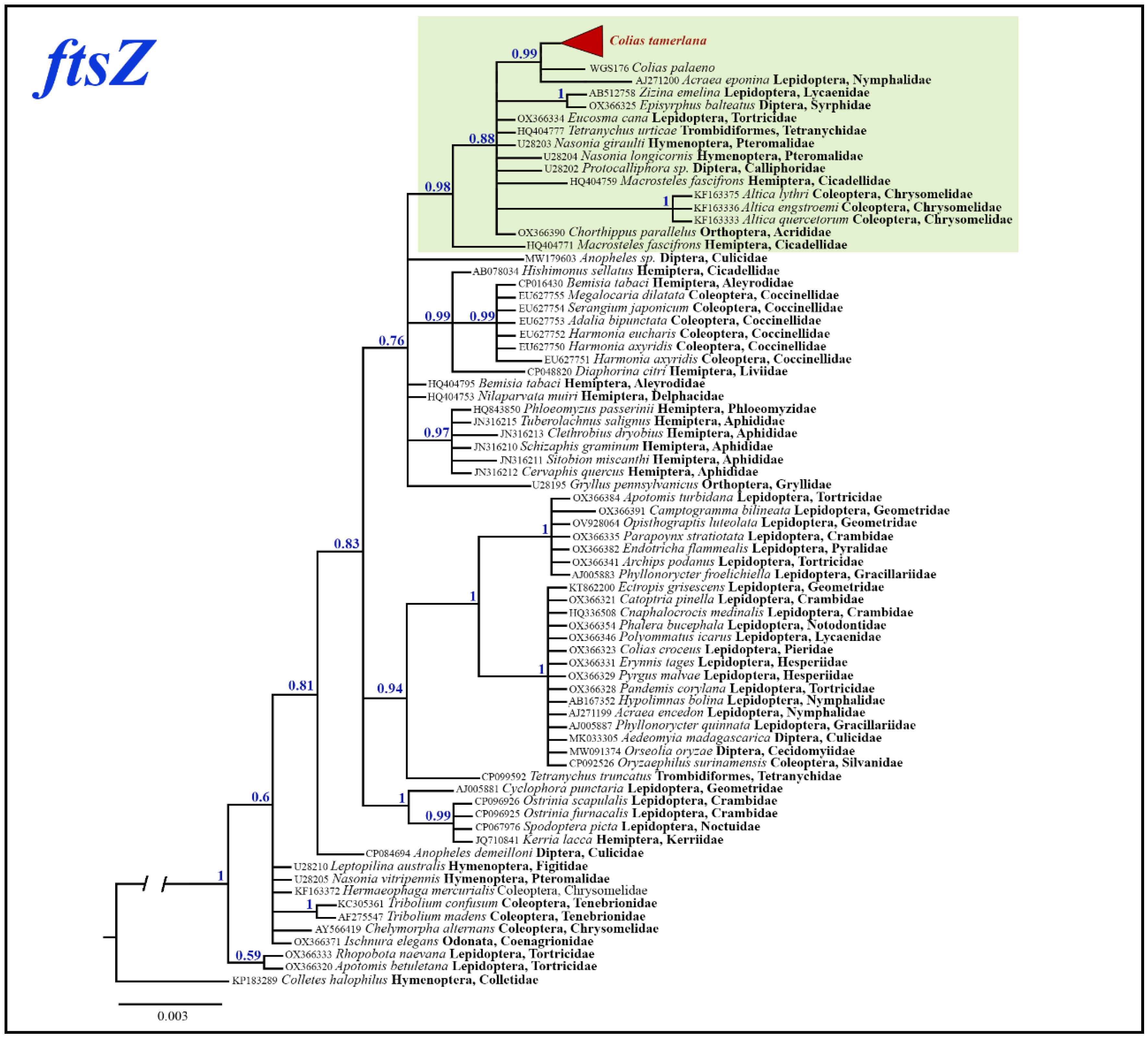

3.3.2. Phylogenetic Inferences

4. Discussion

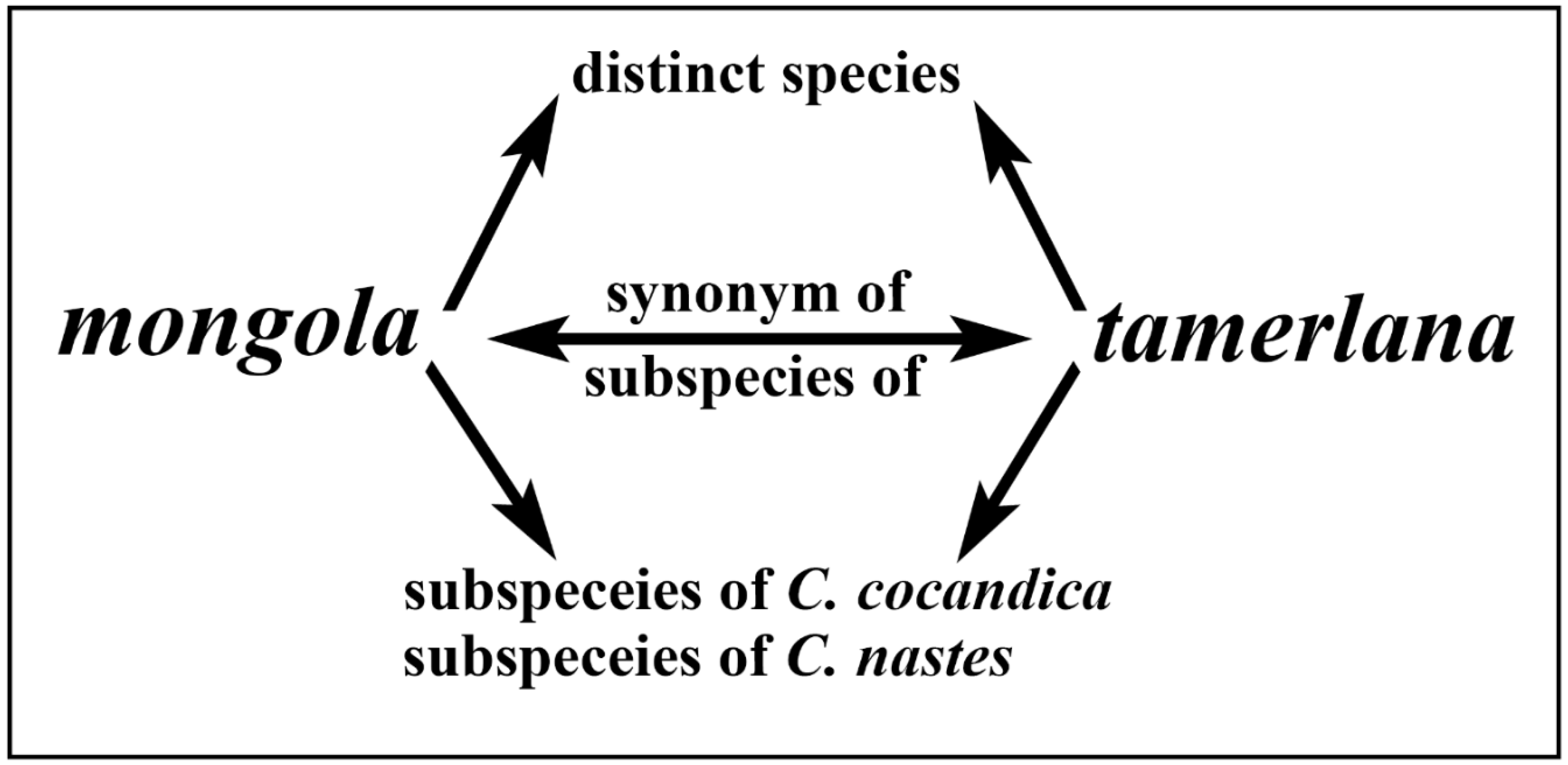

4.1. Molecular Analysis and Taxonomy of C. mongola/C. tamerlana

4.2. Wolbachia Infection in C. mongola/C. tamerlana

5. Conclusions

6. Taxonomic conclusion

- Colias nastes mongola Alphéraky, 1897 = Colias tamerlana Staudinger, 1897, syn. nov.

- Colias mongola ukokana Korb & Yakovlev, 2000 = Colias tamerlana Staudinger, 1897, syn. nov.

- Colias cocandica sidonia Weiss, 1968 = Colias tamerlana Staudinger, 1897, syn. nov.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Greishuber, J. Guide to the butterflies of the Palearctic region. Pieridae part II; Omnes Artes: Milano, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Greishuber, J.; Lamas, G. A synonymic list of the genus Colias Fabricius, 1807 (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Mitt. Münch. Ent. Ges. 2007, 97, 131–171. [Google Scholar]

- Greishuber, J.; Worthy, B.; Lamas, G. The genus Colias Fabricius, 1807. Jan Haugum’s annotated catalogue of the Old World Colias (Lepidoptera, Pieridae); Tshikolovets Publications: Pardubice, Czech Republic, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst, J. Les Colias du Globe. Monograph of the genus Colias; Goecke & Evers: Keltern, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, T. Barcode et Colias africains (Lepidoptera, Pieridae). Entomologia Africana 2018, 23, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kir’yanov, A.V. DNA Barcoding and renewed taxonomy of South American Clouded Sulphurs (Lepidoptera: Pieridae: Colias). Southwest. Entomol. 2021, 46, 891–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kir’yanov, A.V. A new species of Colias Fabricius, 1807 from eastern Sudan (Lepidoptera, Pieridae, Coliadinae). Entomologia Africana 2021, 26, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tshikolovets, V.V.; Yakovlev, R.V.; Bálint, Z. The butterflies of Mongolia; Tshikolovets Publications: Pardubice, Czech Republic, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tshikolovets, V.V.; Yakovlev, R.V.; Kosterin, O.E. The butterflies of Altai, Sayan and Tuva (South Sibiria); Tshikolovets Publications: Pardubice, Czech Republic, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger, O. Drei neue paläarktische Lepidopteren. Deut. ent. Zeit. Iris 1897, 10, 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Alphéraky, S.N. Mémoire sur différents lépidoptères, tant nouveaux que peu connus, de la faune paléarctique. In Mémoires sur les Lépidoptères; Romanoff, N.M., Ed.; Imprimerie de P.P. Soïkine: Saint-Petersburg, Russia, 1897; Vol. 9, pp. 185–227. [Google Scholar]

- Korb, S.K. On the systematic of some Colias cocandica-like taxa (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Phegea 2006, 34, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Gorbunov, O.G. On the nomenclature of Colias nastes mongola Alpheraky, 1897 and Colias tamerlana Staudinger, 1897. Entomol. Rev. 2012, 92, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D. Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Tagfalter-Fauna der Mongolei (Lepidoptera, Rhopalocera). Acta Entomol. Mus. Natl. Pragae 1968, 13, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger, O. Macrolepidoptera. In Catalog der Lepidopteren des palaearctischen Faunengebeites; Staudinger, O., Rebel, H., Eds.; Friedländer & Sohn: Berlin, Germany, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Talbot, G. Pieridae. In Lepidopterorum Catalogus; Strand, E., Ed.; W. Junk: Berlin, Germany, 1935; Vol. 66, pp. 386–697. [Google Scholar]

- Tshikolovets, V.V.; Bidzilya, O.V.; Golovushkin, M.I. The butterflies of Transbaikal Siberia; Tshikolovets Publications: Brno–Kiev, Czech Republic–Ukraine, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tuzov, V.K.; Bogdanov, P.V.; Devyatkin, A.L.; Kaabak, L.V.; Korolev, V.A.; Murzin, V.S.; Samodurov, G.D.; Tarasov, E.A. Guide to the butterflies of Russia and adjacent territories (Lepidoptera, Rhopalocera). Volume I. Hesperiidae, Papilionidae, Pieridae, Satyridae; Pensoft: Sofia–Moscow, Bulgaria–Russia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gorbunov, P.Y. The Butterflies of Russia: Classification, genitalia, keys for identification (Lepidoptera: Hesperioidea and Papilionoidea); Thesis: Ekaterinburg, Russia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gorbunov, P.Y.; Kosterin, O.E. The Butterflies (Hesperioidea and Papilionoidea) of North Asia (Asian Part of Russia) in Nature; Rodina & Fodio and Gallery Fund: Moscow–Chelyabinsk, Russia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kurentsov, A.I. Bulavousye cheshyekrylye Dal’nego Vostoka SSSR [Butterflies of the Far East USSR]; Nauka: Leningrad, USSR, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Korb, S.K.; Yakovlev, R.V. Colias mongola ukokana nov. ssp. (Lepidoptera Pieridae). Alexanor 2000, 21, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dincă, V.; Montagud, S.; Talavera, G.; Hernandez-Roldan, J.; Munguira, M.L.; Garcia-Barros, E.; Hebert, P.D.N.; Vila, R. DNA barcode reference library for Iberian butterflies enables a continental-scale preview of potential cryptic diversity. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukhtanov, V.A.; Dantchenko, A.V.; Vishnevskaya, M.S.; Saifitdinova, A.F. Detecting cryptic species in sympatry and allopatry: analysis of hidden diversity in Polyommatus (Agrodiaetus) butterflies (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2015, 116, 468–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukhtanov, V.A.; Shapoval, N.A. Chromosomal identification of cryptic species sharing their DNA barcodes: Polyommatus (Agrodiaetus) antidolus and P. (A.) morgani in Iran (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae). Comp. Cytogenet. 2017, 11, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, P.C.; McCorkle, D.V. A review of geographic variation and possible evolutionary relationships in the Colias scudderii-gigantea complex of North America (Pieridae). J. Lepid. Soc. 2008, 64, 201–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlberg, N.; Braby, M.F.; Brower, A.V.Z.; De Jong, R.; Lee, M.-M.; Nylin, S.; Pierce, N.E.; Sperling, F.A.H.; Vila, R.; Warren, A.D.; Zakharov, E. Synergistic effects of combining morphological and molecular data in resolving the phylogeny of butterflies and skippers. Proc. Royal Soc. B 2005, 272, 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlberg, N.; Rota, J.; Braby, M.F.; Pierce, N.E.; Wheat, C.W. Revised systematics and higher classification of pierid butterflies (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) based on molecular data. Zool. Scr. 2014, 43, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espeland, M.; Hall, J.P.W.; DeVries, P.J.; Lees, D.C.; Cornwall, M.; Hsu, Y.-F.; Wu, L.-W.; Campbell, D.L.; Talavera, G.; Vila, R.; Salzman, S.; Ruer, S.; Lohman, D.J.; Pierce, N.E. Ancient Neotropical origin and recent recolonisation: phylogeny, biogeography and diversification of the Riodinidae (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2015, 93, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espeland, M.; Breinholt, J.; Willmot, K.R.; Warren, A.D.; Vila, R.; Toussaint, E.F.A.; Maunsell, S.C.; Aduse-Poku, K.; Talavera, R.; Eastwood, R.; Jarzyna, M.A.; Guralnick, R.; Lohman, D.J.; Pierce, N.E.; Kawahara, A. A comprehensive and dated phylogenomic analysis of butterflies. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, R.K.; Warren, A.D.; Wahlberg, N.; Brower, A.V.Z.; Lukhtanov, V.A.; Kodandaramaiah, U. Ten genes and two topologies: an exploration of higher relationships in skipper butterflies (Hesperiidae). PeerJ 2016, 4, e2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, C.; Davis, D.R.; Cummings, M.P. Phylogeny and evolution of Lepidoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2017, 62, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphim, N.; Kaminski, L.A.; Devries, P.J.; Penz, C.; Callaghan, C.; Wahlberg, N.; Silva-Brandao, K.L.; Freitas, A.V.L. Molecular phylogeny and higher systematics of the metalmark butterflies (Lepidoptera: Riodinidae). Syst. Entomol. 2018, 43, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, E.F.A.; Breinholt, E.W.; Earl, C.; Warren, A.D.; Brower, A.V.Z.; Yago, M.; Dexter, K.M.; Espeland, M.; Pierce, N.E.; Lohman, D.J.; Kawahara, A.Y. Anchored phylogenomics illuminates the skipper butterfly tree of life. BMC Evol. Biol. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Cong, Q.; Shen, J.; Brockmann, E.; Grishin, N. Three new subfamilies of skipper butterflies (Lepidoptera, Hesperiidae). ZooKeys 2019, 861, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allio, R.; Scornavacca, C.; Nabholz, B.; Clamens, A.-L.; Sperling, F.A.H.; Fabien, L. Whole genome shotgun phylogenomics resolves the pattern and timing of swallowtail butterfly evolution. Syst. Biol. 2020, 69, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiemers, M.; Chazot, N.; Wheat, C.W.; Schweiger, O.; Wahlberg, N. A complete time-calibrated multi-gene phylogeny of the European butterflies. ZooKeys 2020, 938, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vodă, R.; Dapporto, L.; Dincă, V.; Vila, R. Cryptic matters: overlooked species generate most butterfly beta-diversity. Ecography 2015, 38, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukhtanov, V.A.; Shapoval, N.A.; Dantchenko, A.V. Agrodiaetus shahkuhensis sp. n. (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae), a cryptic species from Iran discovered by using molecular and chromosomal markers. Comp. Cytogenet. 2008, 2, 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Shapoval, N.A.; Lukhtanov, V.A. On the generic position of Polyommatus avinovi (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Folia Biol. (Krakow) 2016, 64, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talavera, G.; Lukhtanov, V.A.; Pierce, N.E.; Vila, R. Establishing criteria for higher-level classification using molecular data: the systematics of Polyommatus blue butterflies (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae). Cladistics 2013, 29, 166–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramp, K.; Cizek, O.; Madeira, P.M.; Ramos, A.A.; Konvicka, M.; Castilho, R.; Schmitt, T. Genetic implications of phylogeographical patterns in the conservation of the boreal wetland butterfly Colias palaeno (Pieridae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 119, 1068–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiho, J.; Ståhls, G. DNA barcodes identify Central Asian Colias butterflies (Lepidoptera, Pieridae). ZooKeys 2013, 365, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheat, C.W.; Watt, W.B. A mitochondrial-DNA-based phylogeny for some evolutionary-genetic model species of Colias butterflies (Lepidoptera, Pieridae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008, 47, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Porter, A.H. An AFLP-based interspecific linkage map of sympatric, hybridizing Colias butterflies. Genetics 2004, 168, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzurinka, M.; Šemeláková, M.; Panigaj, L. Taxonomy of hybridizing Colias croceus (Geoffroy, 1785) and Colias erate (Esper, 1805) (Lepidoptera, Pieridae) in light of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, with occurrence and effects of Wolbachia infection. Zool. Anz. 2022, 299, 73–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ercole, J.; Dincă, V.; Opler, P.A.; Kondla, N.; Schmidt, C.; Phillips, J.D.; Robbins, R.; Burns, J.M.; Miller, S.E.; Grishin, N.; Zakharov, E.V.; DeWaard, J.R.; Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D.N. A DNA barcode library for the butterflies of North America. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, M.G.; Thompson, W.F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980, 8, 4321–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukhtanov, V.A.; Shapoval, N.A. Detection of cryptic species in sympatry using population analysis of unlinked genetic markers: A study of the Agrodiaetus kendevani species complex (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Dokl. Biol. Sci. 2008, 423, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R.C. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Marine Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Hajibabaei, M.; Janzen, D.H.; Burns, J.M.; Hallwachs, W.; Hebert, P.D.N. DNA barcodes distinguish species of tropical Lepidoptera. PNAS 2006, 103, 968–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukhtanov, V.A.; Sourakov, A.; Zakharov, E.V.; Hebert, P.D.N. DNA barcoding Central Asian butterflies: Increasing geographical dimension does not significantly reduce the success of species identification. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009, 9, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlberg, N.; Wheat, C.W. Genomic outposts serve the phylogenomic pioneers: Designing novel nuclear markers for genomic DNA extractions of Lepidoptera. Syst. Biol. 2008, 57, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colgan, D.J.; McLauchlan, A.; Wilson, G.D.F.; Livingston, S.P.; Edgecombe, G.D.; Macaranas, J.; Cassis, G.; Gray, M.R. Histone H3 and U2 snRNA DNA sequences and arthropod molecular evolution. Aust. J. Zool. 1998, 46, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlberg, N.; Peña, C.; Ahola, M.; Wheat, C. W.; Rota, J. PCR primers for 30 novel gene regions in the nuclear genomes of Lepi- doptera. ZooKeys 2016, 596, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cong, O.; Shen, J.; Zhang, J.; Hallwachs, W.; Janzen, D. H.; Grishin, N.V. Genomes of skipper butterflies reveal extensive convergence of wing patterns. PNAS 2019, 116, 6232–6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchfink, B.; Xie, C.; Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werren, J.H.; Windsor, D.M. Wolbachia infection frequency in insects: Evidence of a global equilibrium? Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2000, 267, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Rousset, F.; O’Neil, S. Phylogeny and PCR- based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1998, 265, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldo, L.; Dunning Hotopp, J.C.; Jolley, K.A.; Bordenstein, S.R.; Biber, S.A.; Choudhury, R.R.; Hayashi, C.; Maiden, M.C.; Tettelin, H.; Werren, J.H. Multilocus sequence typing system for the endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 7098–7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; Thierer, T.; Ashton, B.; Meintjes, P.; Drummond, A. Geneious basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T. BioEdit: An important software for molecular biology. GERF Bull. Biosci. 2011, 2, 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- Villesen, P. FaBox: an online toolbox for fasta sequences. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2007, 7, 965–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. JModelTest 2: More models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Meth- ods 2012, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1. 7. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandelt, H.; Forster, P.; Röhl, A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D. PopART: Full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Data Sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajima, F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 1989, 123, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.-X.; Li, W.-H. Statistical test of neutrality of mutations. Genetics 1993, 133, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.-X. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations against population growth, hitchhiking and background selection. Genetics 1997, 147, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werren, J.H.; Zhang, W.; Guo, L.R. Evolution and phylogeny of Wolbachia: Reproductive parasites of arthropods. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1995, 261, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Rousset, F.; O’Neil, S. Phylogeny and PCR- based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1998, 265, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousset, F.; de Stordeur, E. Properties of Drosophila simulans strains experimentally infected by different clones of the bacterium Wolbachia. Heredity 1994, 72, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, D.J.; Omland, K.E. Species-level paraphyly and polyphyly: frequency, causes, and consequences, with insights from animal mitochondrial DNA. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 34, 397–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, G.D.D.; Jiggins, F.M. Problems with mitochondrial DNA as a marker in population, phylogeographic and phylogenetic studies: the effects of inherited symbionts. Proc. Royal Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005, 272, 1525–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiemers, M.; Fiedler, K. Does the DNA barcoding gap exist? - a case study in blue butterflies (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Front. Zool. 2007, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakharov, E.V.; Lobo, N.F.; Nowak, C.; Hellma, J.J. Introgression as a likely cause of mtDNA paraphyly in two allopatric skippers (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae). Heredity 2009, 102, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerth, M.; Geißler, A.; Bledidorn, C. Wolbachia infections in bees (Anthophila) and possible implications for DNA barcoding. Syst. Biodivers. 2011, 9, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvie, K.S.; Hogner, S.; Aarvik, L.; Lifjeld, J.T.; Johnsen, A. Deep sympatric mtDNA divergence in the autumnal moth (Epirrita autumnata). Ecol. Evol. 2013, 3, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritter, S.; Michalski, S.G.; Settele, J.; Wiemers, M.; Fric, Z.F.; Sielezniew, M.; Šašić, M.; Rozier, Y.; Durka, W. Wolbachia infections mimic cryptic speciation in two parasitic butterfly species, Phengaris teleius and P. nausithous (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). PloS ONE 2013, 8, e78107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Cywinska, A.; Ball, S.L.; DeWaard, J.R. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc. Royal Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausmann, A.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Huemer, P.; Mutanen, M.; Rougerie, R.; van Nieukerken, E.J.; Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D.N. Genetic patterns in European geometrid moths revealed by the Barcode Index Number (BIN) system. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D.N. A DNA-based registry for all animal species: the Barcode Index Number (BIN) system. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Ratnasingham, S.; Zakharov, E.V.; Telfer, A.C.; Levesque-Beaudin, V.; Milton, M.A.; Pedersen, S.; Jannetta, P.; deWaard, J.R. Counting animal species with DNA barcodes: Canadian insects. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B, Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friberg, M.; Bergman, M.; Kullberg, J.; Wahlberg, N.; Wiklund, C. Niche separation in space and time between two sympatric sister species – a case of ecological pleiotropy. Evol. Ecol. 2008, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friberg, M.; Olofsson, M.; Berger, D.; Karlsson, B.; Wiklund, C. Habitat choice precedes host plant choice-niche separation in a species pair of a generalist and a specialist butterfly. Oikos 2008, 117, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friberg, M.; Leimar, O.; Wiklund, C. Heterospecific courtship, minority effects and niche separation between cryptic butterfly species. J. Evol. Biol. 2013, 26, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunkhe, R.C.; Narkhede, K.P.; Shouche, Y.S. Distribution and evolutionary impact of Wolbachia on butterfly hosts. Indian J Microbiol. 2014, 54, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.Z.; Araujo-Jnr, E.V.; Welch, J.J.; Kawahara, A.Y. Wolbachia in butterflies and moths: geographic structure in infection frequency. Front. Zool. 2015, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilinsky, Y.; Kosterin, O.E. Molecular diversity of Wolbachia in Lepidoptera: Prevalent allelic content and high recombination of MLST genes. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2017, 109, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Bertrand, C.; Crosby, K.; Eveleigh, E.S.; Fernandez-Triana, J.; Fisher, B.L.; Gibbs, J.; Hajibabaei, M.; Hallwachs, W.; Hind, K.; Hrcek, J.; Huang, D.W.; Janda, M.; Janzen, D.H.; Li, Y.; Miller, S.E.; Packer, L.; Quicke, D.; Ratnasingham, S.; Rodriguez, J.; Rougerie, R.; Shaw, M.R.; Sheffield, C.; Stahlhut, J.K.; Steinke, D.; Whitfield, J.; Wood, M.; Zhou, X. Wolbachia and DNA barcoding insects: patterns, potential, and problems. PloS ONE 2012, 7, e36514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodandaramaiah, U.; Simonsen, T.J.; Bromilow, S.; Wahlberg, N.; Sperling, F. Deceptive single-locus taxonomy and phylogeography: Wolbachia-associated divergence in mitochondrial DNA is not reflected in morphology and nuclear markers in a butterfly species. Ecol. Evol. 2013, 3, 5167–5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.Z.; Breinholt, J.W.; Kawahara, A.Y. Evidence for common horizontal transmission of Wolbachia among butterflies and moths. BMC Evol. Biol. 2016, 16, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, R.K.; Lohman, D.J.; Wahlberg, N.; Müller, C.J.; Brattström, O.; Collins, S.C.; Peggie, D.; Aduse-Poku, K.; Kodandaramaiah, U. Evolution of Hypolimnas butterflies (Nymphalidae): Out-of-Africa origin and Wolbachia-mediated introgression. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2018, 123, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaunet, A.; Dincă, V.; Dapporto, L.; Montagud, S.; Vodă, R.; Schär, S.; Badiane, A.; Font, E.; Vila, R. Two consecutive Wolbachia-mediated mitochondrial introgressions obscure taxonomy in Palearctic swallowtail butterflies (Lepidoptera, Papilionidae). Zool. Scr. 2019, 48, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplouy, A.; Pranter, R.; Warren-Gash, H.; Tropek, R.; Wahlberg, N. Towards unravelling Wolbachia global exchange: a contribution from the Bicyclus and Mylothris butterflies in the Afrotropics. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arif, S.; Gerth, M.; Hone-Millard, W.G.; Nunes, M.D.S.; Dapporto, L.; Shreeve, T.G. Evidence for multiple colonisations and Wolbachia infections shaping the genetic structure of the widespread butterfly Polyommatus icarus in the British Isles. Mol Ecol. 2021, 30, 5196–5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucek, K.; Bouaouina, S.; Jospin, A.; Grill, A.; de Vos, J.M. Prevalence and relationship of endosymbiotic Wolbachia in the butterfly genus Erebia. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2021, 21, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucháčková Bartoňová, A.; Konvička, M.; Marešová, J.; Wiemers, M.; Ignatev, N.; Wahlberg, N.; Schmitt, T.; Faltýnek Fric, Z. Wolbachia affects mitochondrial population structure in two systems of closely related Palaearctic blue butterflies. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, M.; Kulanek, D.; Varga, Z.; Rákosy, L.; Schmitt, T. Pronounced mito-nuclear discordance and various Wolbachia infections in the water ringlet Erebia pronoe have resulted in a complex phylogeographic structure. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, S.; Shimajiri, Y.; Nomura, M. Strong cytoplasmic incompatibility and high vertical transmission rate can explain the high frequencies of Wolbachia infection in Japanese populations of Colias erate poliographus (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 2009, 99, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.-H.; Gao, S. A prevalence survey of Wolbachia in butterflies from South China. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2021, 169, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.L.; Giordano, R.; Colbert, A.M.E.; Karr, T.L. 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis of the bacterial endosymbionts associated with cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992, 89, 2699–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, F.; Bouchon, D.; Pintureau, B.; Solignac, M. Wolbachia endosymbionts responsible for various alterations of sexuality in arthropods. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1992, 250, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascarenhas, R.O.; Prezotto, L.F.; Perondini, A.L.P.; Marino, C.L.; Selivon, D. Wolbachia in guilds of Anastrepha fruit flies (Teph- ritidae) and parasitoid wasps (Braconidae). Genet. Mol. Biol. 2016, 39, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Braswell, W.E.; Pelz-Stelinski, K.S. Genetic variation and potential coinfection of Wolbachia among widespread Asian citrus psyllid (Diaphorina citri Kuwayama) populations. Insect Sci. 2019, 26, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintupachee, S.; Milne, J.R.; Poonchaisri, S.; Baimai, V.; Kittayapong, P. Closely related Wolbachia strains within the pumpkin arthropod community and the potential for horizontal transmission via the plant. Microb. Ecol. 2006, 51, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutzwiller, F.; Dedeine, F.; Kaiser, W.; Giron, D.; Lopez-Vaamonde, C. Correlation between the green-island phenotype and Wolbachia infections during the evolutionary diversification of Gracillariidae leaf-mining moths. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 4049–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavre, F.; Fleury, F.; Lepetit, D.; Fouillet, P.; Bouletreau, M. Phylogenetic evidence for horizontal transmission of Wolbachia in host-parasitoid associations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 1711–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haine, E.R.; Pickup, N.J.; Cook, J.M. Horizontal transmission of Wolbachia in a Drosophila community. Ecol. Entomol. 2005, 30, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesen, J. Tracing the history and ecological context of Wolbachia double infection in a specialist host (Urophora cardui) – parasitoid (Eurytoma serratulae) system. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.-Q.; Zhao, G.-Z.; Su, C.-Y.; Zhu, D.-H. Wolbachia prevalence patterns: horizontal transmission, recombination, and multiple infections in chestnut gall wasp-parasitoid communities. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2020, 168, 752–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuhashi, W.; Saiki, T.; Wei, W.; Kawakita, H.; Sato, M. Two novel strains of Wolbachia coexisting in both species of mulberry leafhoppers. Insect Mol. Biol. 2002, 11, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittayapong, P.; Jamnongluk, W.; Thipaksorn, A.; Milne, J.R.; Sindhusake, C. Wolbachia infection complexity among insects in the tropical rice-field community. Mol. Ecol. 2003, 12, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sintupachee, S.; Milne, J.R.; Poonchaisri, S.; Baimai, V.; Kittayapong, P. Closely related Wolbachia strains within the pumpkin arthropod community and the potential for horizontal transmission via the plant. Microb. Ecol. 2006, 51, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.-H.; Zhu, D.-H.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Su, C.-Y. High levels of multiple infections, recombination and horizontal transmission of Wolbachia in the Andricus mukaigawae (Hymenoptera; Cynipidae) communities. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-J.; Ahmed, M.Z.; Lv, N.; Shi, P.-Q.; Wang, X.-M.; Huang, J.-L.; Qui, B.-L. Plantmediated horizontal transmission of Wolbachia between whiteflies. ISME J. 2017, 11, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousset, F.; Solignac, M. The evolution of single and double Wolbachia symbioses during speciation in the Drosophila simulans complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995, 92, 6389–6393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiggins, F.M. Male-killing Wolbachia and mitochondrial DNA: selective sweeps, hybrid introgression and parasite population dynamics. Genetics 2003, 164, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, B.S.; Vanderpool, D.; Conner, W.R.; Matute, D.R.; Turelli, M. Wolbachia acquisition by Drosophila yakuba-clade hosts and transfer of incompatibility loci between distantly related Wolbachia. Genetics 2019, 212, 1399–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraldo, A.; Duplouy, A. High Wolbachia strain diversity in a clade of dung beetles endemic to Madagascar. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Clec’h, W.; Chevalier, F.D.; Genty, L.; Bertaux, J.; Bouchon, D.; Sicard, M. Cannibalism and predation as paths for horizontal passage of Wolbachia between terrestrial isopods. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, M.; Albanese, D.; Tuohy, K.; Donati, C.; Segata, N.; Rota-Stabelli, O. Large scale genome reconstructions illuminate Wolbachia evolution. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bing, X.-L.; Zhao, D.-S.; Sun, J.-T.; Zhang, K.-J.; Hong, X.-Y. Genomic analysis of Wolbachia from Laodelphax striatellus (Delphacidae, Hemiptera) reveals insights into its “Jekyll and Hyde” mode of infection pattern. Genome Biol. Evol. 2020, 12, 3818–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradt, L.; Corbet, S.A.; Roper, T.J.; Bodsworth, E.J. Parasitism by the mite Trombidium breei on four UK butterfly species. Ecol. Entomol. 2002, 27, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaei, E.; Charlat, S.; Engelstädter, J. Wolbachia host shifts: routes, mechanisms, constraints and evolutionary consequences. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 433–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovyev, V.I.; Ilinsky, Y.; Kosterin, O.E. Genetic integrity of four species of Leptidea (Pieridae, Lepidoptera) as sampled in sympatry in West Siberia. Comp. Cytogenet. 2015, 9, 299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhov, I.A.; Gorodilova, Y. Yu.; Lukhtanov, V.A. Sympatric occurrence of deeply diverged mitochondrial DNA lineages in Siberian geometrid moths (Lepidoptera: Geometridae): cryptic speciation, mitochondrial introgression, secondary admixture or effect of Wolbachia? Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2021, 134, 342–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y. Overlapping distribution of two groups of the butterfly Eurema hecabe differing in the expression of seasonal morphs on Okinawa- jima Island. Zool. Sci. 2000, 17, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, S.; Kageyama, D.; Nomura, M.; Fukatsu, T. Unexpected mechanism of symbiont-induced reversal of insect sex: feminizing Wolbachia continuously acts on the butterfly Eurema hecabe during larval development. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 4332–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, P.; Cook, J.M.; Kageyama, D.; Riegler, M. Double trouble: Combined action of meiotic drive and Wolbachia feminization in Eurema butterflies. Biol. Lett. 2015, 11, 20150095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werren, J.H.; Baldo, L.; Clark, M.E. Wolbachia: Master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplouy, A.; Hornett, E.A. Uncovering the hidden players in Lepidoptera biology: The heritable microbial endosymbionts. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Taxon | Sample ID | Sex | COI haplotype | Wolbachia | Year | Locality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S | wsp | ftsZ | ||||||

| tamerlana | Akr01 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2016 | (01)** China, Xinjiang |

| tamerlana | Akr02 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2016 | (01) China, Xinjiang |

| tamerlana | Akr03 | ♀ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2016 | (01) China, Xinjiang |

| tamerlana | Akr04 | ♀ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2016 | (01) China, Xinjiang |

| tamerlana | CL162 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2016 | (01) China, Xinjiang |

| tamerlana LT | 21128B07 | ♂ | hp1b | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1896 | (01) China, Xinjiang |

| tamerlana PLT | 20022A02 | ♀ | hp1b | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1896 | (01) China, Xinjiang |

| mongola | Mnt03 | ♂ | hp1b | - | - | - | 2018 | (02) Mongolia, Hovd |

| mongola | Mnt04 | ♀ | hp3b | - | - | - | 2018 | (02) Mongolia, Hovd |

| mongola | CL34m | ♂ | hp1c | - | - | - | 2015 | (02) Mongolia, Hovd |

| mongola | Mnt54 | ♀ | hp1b | - | - | - | 2003 | (17) Mongolia, Hovd |

| mongola | Mnt55 | ♀ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2003 | (17) Mongolia, Hovd |

| mongola | Mnt56 | ♀ | hp1b | - | - | - | 2003 | (17) Mongolia, Hovd |

| mongola | Mnt57 | ♀ | hp1b | - | - | - | 2003 | (17) Mongolia, Hovd |

| mongola | Mnt58 | ♀ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2003 | (17) Mongolia, Hovd |

| mongola | Mnt59 | ♀ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2003 | (17) Mongolia, Hovd |

| mongola | Mnt60 | ♀ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2003 | (17) Mongolia, Hovd |

| mongola | Mnt61 | ♂ | hp1b | - | - | - | 2003 | (17) Mongolia, Hovd |

| mongola | Mnt62 | ♂ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2003 | (17) Mongolia, Hovd |

| mongola | Mnt63 | ♂ | hp1b | - | - | - | 2003 | (17) Mongolia, Hovd |

| mongola | Mnt01 | ♀ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2013 | (03) Mongolia, Gobi-Altai |

| mongola | Mnt02 | ♀ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2013 | (03) Mongolia, Gobi-Altai |

| mongola | CL41m | ♀ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2017 | (03) Mongolia, Gobi-Altai |

| mongola | Nsk16 | ♂ | hp2 | - | - | - | 2005 | (04) Mongolia, Bayan-Ulegej |

| mongola | CL39m | ♀ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2017 | (05) Mongolia, Bayan-Ulegej |

| mongola | CL40m | ♀ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2017 | (05) Mongolia, Bayan-Ulegej |

| mongola | CL43m | ♀ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2017 | (05) Mongolia, Bayan-Ulegej |

| mongola | Mnt24z | ♀ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2017 | (05) Mongolia, Bayan-Ulegej |

| mongola | Mnt25z | ♀ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2017 | (05) Mongolia, Bayan-Ulegej |

| mongola | Mnt53 | ♀ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2004 | (16) Mongolia, Zavkhan |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt18 | ♀ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2022 | (06) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt19 | ♀ | hp3c | - | - | - | 2022 | (06) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt20 | ♂ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2022 | (06) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt21 | ♂ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2022 | (06) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt22 | ♂ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2022 | (06) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt23 | ♂ | hp2 | - | - | - | 2022 | (06) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Nsk014 | ♂ | hp3a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1997 | (07) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt34z | ♂ | hp3a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1997 | (07) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana PT | Nsk015 | ♂ | hp4c | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1995 | (08) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt24 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt25 | ♀ | hp1a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt26 | ♂ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt27 | ♀ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt28 | ♀ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt29 | ♂ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt30 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt31 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt32 | ♂ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt33 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt34 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt35 | ♂ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt36 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt37 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt38 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt39 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt44 | ♂ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt45 | ♂ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt46 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt47 | ♂ | hp3d | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt48 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt49 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt50 | ♂ | hp3d | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt51 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2001 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Ku01 | ♀ | hp3e | - | - | - | 2022 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Ku02 | ♀ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2022 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Ku03 | ♂ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2022 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Ku04 | ♂ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2022 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt28z | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2022 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt29z | ♀ | hp3e | - | - | - | 2022 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt30z | ♂ | hp3d | - | - | - | 2022 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | LOWA141-06* | ♂ | hp3a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1999 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | LOWA818-06* | ♂ | hp3a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1999 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | LOWA142-06* | ♂ | hp4b | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1999 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | CL42m | ♀ | hp1a | - | - | - | 2017 | (09) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt17 | ♀ | hp1a | - | - | - | 2022 | (10) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt40 | ♀ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2003 | (10) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt41 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2003 | (10) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt42 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2003 | (10) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt43 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2003 | (10) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt09 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2002 | (11) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt10 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2002 | (11) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt08 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2003 | (12) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola ukokana | Mnt12 | ♂ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2003 | (12) Russia, Republic of Altai |

| mongola | Mnt14 | ♀ | hp2 | + | + | + | 2010 | (13) Russia, Republic of Tyva |

| mongola | Mnt15 | ♀ | hp3a | - | - | - | 2010 | (13) Russia, Republic of Tyva |

| mongola | Mnt07 | ♂ | hp2 | - | - | - | 2002 | (14) Russia, Republic of Tyva |

| mongola | CL35m | ♀ | hp1b | - | - | - | 2002 | (14) Russia, Republic of Tyva |

| mongola | CL37m | ♂ | hp1b | - | - | - | 2002 | (14) Russia, Republic of Tyva |

| mongola | CL38m | ♀ | hp1a | - | - | - | 2002 | (14) Russia, Republic of Tyva |

| mongola | CL54m | ♂ | hp1b | - | - | - | 2002 | (14) Russia, Republic of Tyva |

| mongola | CL55m | ♂ | hp4a | - | - | - | 2002 | (14) Russia, Republic of Tyva |

| mongola | CL56m | ♂ | hp1b | - | - | - | 2002 | (14) Russia, Republic of Tyva |

| mongola | CL57m | ♀ | hp1b | - | - | - | 2002 | (14) Russia, Republic of Tyva |

| mongola | Mnt26z | ♂ | hp1a | - | - | - | 2002 | (14) Russia, Republic of Tyva |

| mongola | Mnt05 | ♀ | hp1b | - | - | - | 2001 | (15) Russia, Republic of Tyva |

| mongola | Mnt06 | ♀ | hp1b | - | - | - | 2001 | (15) Russia, Republic of Tyva |

| mongola LT | 20022A03 | ♂ | hp1b | n/a | n/a | n/a | ? | (??) see text for explanation |

| sidonia | S1-22064B02 | ♀ | hp1b | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1967 | (18) Mongolia, Khovsgol |

| sidonia | S2-22064B03 | ♀ | hp1b | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1966 | (18) Mongolia, Khovsgol |

| sidonia | S3-22064B04 | ♂ | hp1b | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1967 | (18) Mongolia, Khovsgol |

| sidonia | S4-22064B05 | ♂ | hp1b | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1967 | (18) Mongolia, Khovsgol |

| N | HG | H | S | π | h | Tajima’s D | Fu and Li’s D | Fu and Li’s F | Fu’s Fs | max. p-distance | within group divergence | between group divergence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 | 4 | 12 | 28 | 0.0138656 | 0.7874 | 2.01246 | 1.21273 | 1.82127 | 7.422 | 2.89% | HP_I 0.04% (± 0.02%) | HP_I / HP_II 2.56% (± 0.59%) |

| 0.1 > p > 0.05 | p>0.1 | p<0.05 | p=0.001 | (± 0.62%) | HP_II 0.00% (±0.00%) | HP_I / HP_III 2.40% (± 0.57%) | ||||||

| HP_III 0.07% (± 0.05%) | HP_I / HP_IV 2.56% (± 0.58%) | |||||||||||

| HP_I 0.04% (± 0.03%) | HP_II / HP_III 1.39% (± 0.42%) | |||||||||||

| HP_II / HP_IV 1.23% (± 0.41%) | ||||||||||||

| HP_III / HP_IV 1.41% (± 0.43%) |

| Haplogroup | n | Sn | COI haplotype | n | Sn | Samplingsite* | n | HGn | Hn | COI haplotype (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP_I | 26 | 9 | hp1a | 5 | 4 | 01 | 7 | 2 | 2 | hp1b (2), hp3a (5) | |||

| hp1b | 20 | 6 | 02 | 3 | 2 | 3 | hp1a (1), hp1c (1), hp3b (1) | ||||||

| hp1c | 1 | 1 | 03 | 3 | 1 | 1 | hp2 (3) | ||||||

| HP_II | 17 | 10 | hp2 | 17 | 10 | 04 | 1 | 1 | 1 | hp2 (1) | |||

| HP_III | 42 | 11 | hp3a | 35 | 9 | 05 | 5 | 3 | 3 | hp2 (2), hp3a (2), hp4a (1) | |||

| hp3b | 1 | 1 | 06 | 6 | 3 | 3 | hp2 (2), hp3c (1), hp4a (3) | ||||||

| hp3c | 1 | 1 | 07 | 2 | 1 | 1 | hp3a (2) | ||||||

| hp3d | 3 | 1 | 08 | 1 | 1 | 1 | hp4c (1) | ||||||

| hp3e | 2 | 1 | 09 | 35 | 4 | 7 | hp1a (2), hp2 (1), hp3a (17), hp3d (3), hp3e (2), hp4a (9), hp4b (1) | ||||||

| HP_IV | 16 | 4 | hp4a | 14 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 3 | hp1a (1), hp2 (1), hp3a (3) | |||

| hp4b | 1 | 1 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 1 | hp3a (2) | ||||||

| hp4c | 1 | 1 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 1 | hp3a (2) | ||||||

| 13 | 2 | 2 | 2 | hp2 (1), hp3a (1) | |||||||||

| 14 | 9 | 3 | 4 | hp1a (2), hp1b (5), hp2 (1), hp4a (1) | |||||||||

| 15 | 2 | 1 | 1 | hp1b (2) | |||||||||

| 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | hp2 (1) | |||||||||

| 17 | 10 | 3 | 3 | hp1b (5), hp2 (4), hp3a (1) | |||||||||

| 18 | 4 | 1 | 1 | hp1b (4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).