Introduction

This article describes an interdisciplinary, arts-based, doctoral project which assembles threads from psychoanalysis, art (psycho)therapy, and the arts to explore the psychosocial role of reflexive art practice in honing sensitivity to the affective dimensions of human situations and experience (Michaels, 2022b).

Background

The philosopher Donald Schön writes of the inherently unstable, complex, nature of practice, of tangled webs and turbulent environments, and of swampy lowlands where ‘situations are confusing “messes” incapable of technical solution’ but where the problems of greatest human concern might be (Schön, 1983, p.42).

It is motivated by a concern that imaginative, reflective spaces that enliven our emotional, affective, and ethical sensitivities are being severely eroded (Bunting, 2020, Cooper and Lousada, 2005, Bolton, 2010, Etherington, 2004a, Huet, 2012). While reflective and reflexive attitudes are deemed essential for responsible and ethical practice, increasing mechanisation, systemisation, and scrutiny of the human services with expectations of constant activity, efficiency, and productivity strike at the tacit, less articulable, subtleties of practice (McIntosh, 2010, Candy, 2019). Such demands make it difficult to adopt a contemplative, attitude or to engage with the complex and difficult in substantial and intense ways (Walker, 2016). This risks reducing reflection and reflexivity in professional practice to a simple matter of ‘thinking rigorously’ where emotionally-charged, affect-laden, landscapes, feeling, and imagination are downplayed in favour of more easily measurable targets (Candy, 2019, Boud and Walker, 1998, Bolton, 2010, Collier, 2010). Feelings, bodily sensations, and imaginings accompany all our practice and research encounters (Holmes, 2014); yet, the subjective, affective, cultural life of the practitioner-researcher is often seen as irrelevant, embarrassing, or disruptive, and relegated to an unspoken, unheard place (Healey, 2015, Kenny and Gilmore, 2014, Holmes, 2010, McNiff and Nash, 2017). Nonetheless, rooted in human experience and feeling, subjectivity, imagination, and affect remain the realm in which much clinical work takes place. This, it might be argued, makes attending to such matters even more important.

Art as Research

Arts-based research (ABR) asserts the fundamental belief that artistic practices are integral to learning and generating knowledge (Vear, 2022, Leavy, 2017). Increasingly acknowledged as a valid mode of enquiry (Nelson, 2013, Gray and Malins, 2004, Sullivan, 2010), and inherently interdisciplinary in nature (Cazeaux, 2008, Michaels, 2022c), ABR is especially significant to the field of art therapy. Expanding on heuristic self-dialogue, attention is directed outwards to dialogues with the making process and its products (McNiff, 2008), with meanings residing in the questions provoked, what is learnt along the way, and how new understandings emerge (Hogan and Pink, 2010, Candy, 2019, Ryan, 2014). Working across boundaries, the arts offer a multiplicity of models, metaphors, forms, and approaches through which to experience and consider different situations, articulate and share understanding, engage audiences, and facilitate critical reflection on the way practices are organised (Sade, 2022, Kaimal et al., 2022, McCaffrey and Edwards, 2015, Eastwood, 2022, Skukauskaite et al., 2022). Rooted in feeling, while drawing on social meanings as subject matter, the arts make empathic participation possible through forms and practices that are evocative and compelling, facilitating access to marginalised perspectives and cultivating an increased social consciousness (Barone and Eisner, 2012, Leavy, 2009, Leavy, 2017).

Experiential processes of making are central to art (psycho)therapy trainings; art (psycho)therapists have been using responsive, reflexive, artmaking to deepen attunement and broaden understanding since the early days of the profession (Fish, 2023, Nash, 2020). Yet, while there is growing interest in ABR approaches (Nash, 2021, Huet and Kapitan, 2021, Malchiodi, 2017, Mahony, 2009, Eastwood, 2022, Gregory, 2021, Kaimal et al., 2022, Learmonth and Huckvale, 2012), it is still the case that comparatively few art (psycho)therapists write about, or undertake research through, their own art practice. Perhaps this is because staying close to more subjective or artistic ways of knowing goes against the grain of prevailing institutional norms and values which demand that art-based disciplines, including the arts therapies, justify themselves through ‘scientific’ evidence (McNiff, 2017).

Expanding on previous thoughts (Michaels, 2015) my hypothesis on starting this project is that, by assembling ideas and practices differently, embracing an attitude of curiosity, discovery, wonder (Kapitan, 2018), and learning through experiences of ‘making’, this research might contribute to thinking about the psychosocial role of reflexive art practice in honing sensitivity to affective dimensions of human situations and experience; my aim being, to explore how reflexive art practice as a research methodology may affectively enhance and amplify our understanding of the research subject. A primary objective, however, is not to be ‘objective’, in that I do not carry out an impersonal, systematic enquiry or present a complete, ‘factual’ account of events. Placing my artistic practice at the centre of the research process, I offer an account of my subjective sensitivity to a research situation I construct (in part at least) – a partial, situated, view which argues, after feminist scholar, Donna Haraway, that ‘only partial perspective promises objective vision’ (Haraway, 1988, p.583).

METHOD

Study Design

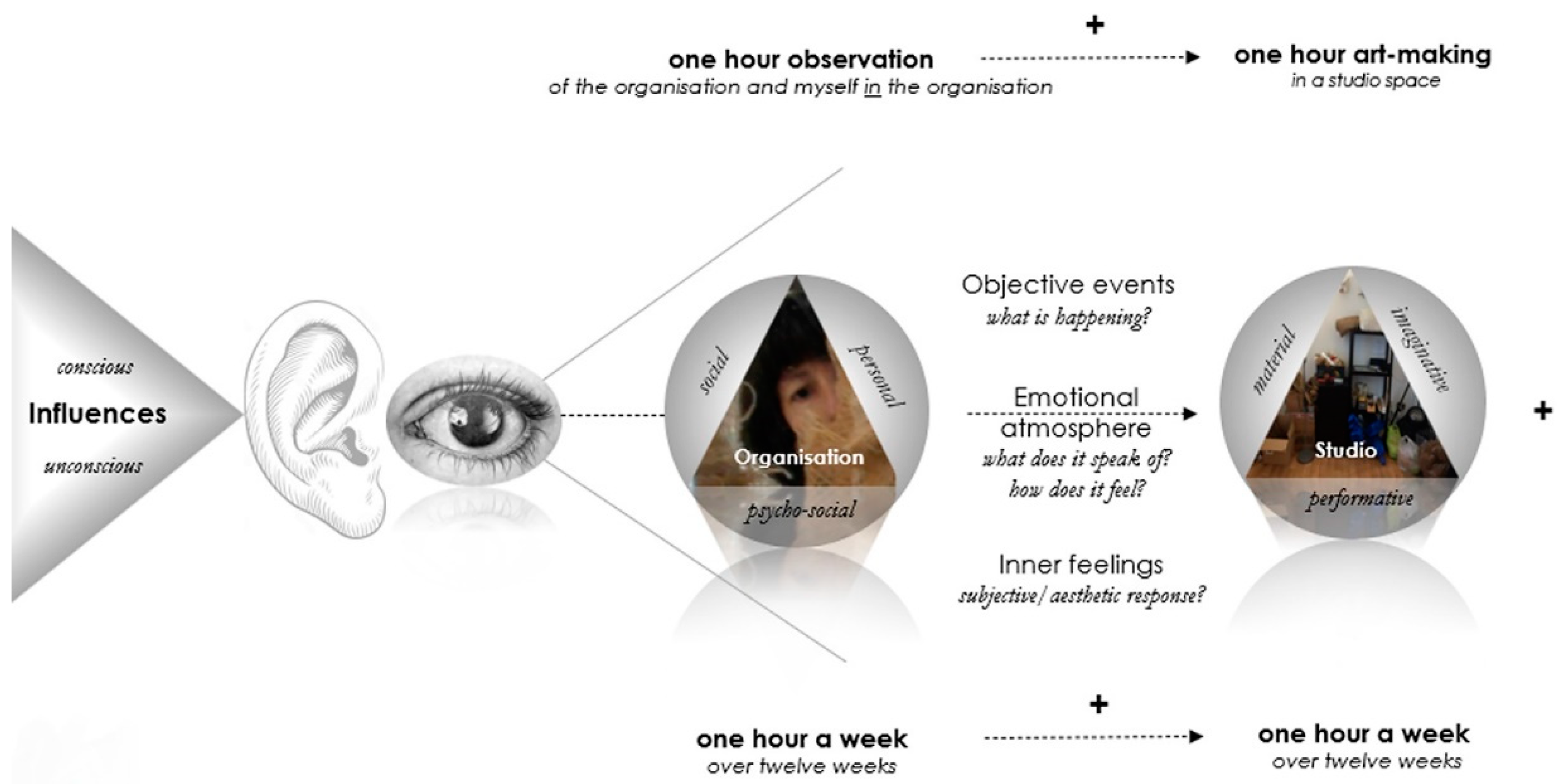

My method is grounded in artistic practice as an experimental, experiential, reflexive process of moving, handling, modifying, and assembling ideas, objects, and things (Vear, 2022). Specifically, I expand on a training model of organisational observation described in the psychoanalytic literature (Hinshelwood and Skogstad, 2000, Hinshelwood, 2013, Hinshelwood, 2002). This emphasises the subjective experience of the participant-observer and their ordinary human capacity to intuitively tune in to the atmosphere of a situation. Transposing this frame into the arts, I use it as scaffolding on which to build an original research response (Kapitan, 2018), adapting and modifying the model by weaving in threads from art (psycho)therapy that involve artmaking as a responsive, reflexive, space for broadening and deepening an understanding of a situation through allowing it to find an 'echo' in one's own inner life (Nash, 2020, Fish, 2012, Rogers, 2002, Townsend, 2019). Assembling these approaches I embrace my research as an active, imaginative, process of exploration, encounter, engagement, participation, and discovery through which new possibilities and insights into self and/or practice may emerge (Finlay, 2008, Linesch, 1995, Boud et al., 2013, Candy et al., 2022). The implication is that the world may reveal itself through fluctuations and movements in the situation I set up, that I am ‘part of – affecting and affected by – the research process, and that the situation can answer back and contribute to this interaction’ (Knudsen and Stage, 2015, pp.5-6).

Underpinning my method is the principle that my understanding of the world is unique to me, and that processes of learning and meaning-making are personal, sensory, social, and contextual, requiring my active involvement. I am influenced by psychoanalysis and approaches that emphasise the ‘tacit’ dimension, and the potential for intuitive processes to bring to awareness what is sensed but cannot easily be explained (Polanyi, 1966, Milner, 2010 [1950]). My approach is also informed by feminist ideas that challenge dualist thinking and embrace complex relationalities, encouraging reflexivity and responsibility (Etherington, 2004b), as well as ideas that emphasise the materiality of the world and invite, tentative, marginalised, affective, and subjective voices to be heard alongside more dominant discourses (Barad, 2007, Fox and Alldred, 2016, Dolphijn and Van Der Tuin, 2012).

I describe the study design in three phases:

Phase One – Prepare the Ground

Exploring the implications of crossing disciplinary boundaries from art (psycho)therapy to the fine arts, I transfer ideas, approaches, and practices from one place to another, tentatively testing out how documentation of personal experience through various media and processes might become material for artistic practice and research. I also prepare the ground for a participant-observation, approaching several different organisations in health and social care sectors. Identifying a host organisation, I work with staff to negotiate a twelve-week observational placement and apply for the necessary ethical approvals and permissions.

Alongside this, I prepare a small studio space away from the organisational site, assembling a range of materials and tools and installing various documentary devices including a paper backdrop, camera set on five-second time-lapse, and audio and video equipment (

Figure 1). Further data collection strategies include a research journal to record written observations, notes, and reflections, an iPhone to record fleeting thoughts and the use of Fitbit tracking technology to trace personal metrics including speed, heartrate, and journeys travelled.

Phase Two – Experience the situation and myself in it

The host for the participant-observation is an NHS community-based service providing day rehabilitation for adults living with neurological conditions.

1 Following the psychoanalytic model I attend for one hour a week from 9.30-10.30am, over a period of twelve weeks, on a day allocated for people living with the residual effects of stroke. I sit in full view, in the same place each week, on the edge of a communal area where service-users are attended to by nursing and support staff and a range of health professionals. While I observe from a place that offers a wide field of view and hearing, I do not observe individual treatment processes which take place away from the communal area. I use my personality, as well as my sensory and emotional sensitivity as an apparatus for receiving and processing subjective information, adopting an attitude of ‘evenly suspended attention’ (Freud, 2001) and open interest in whatever is going on, without engaging directly with people, except to respond sensitively and respectfully to any approaches (Hinshelwood and Skogstad, 2000).

I follow each ‘observation’ in the organisation with one hour ‘making’ in the studio from 11.15am-12.15pm (

Figure 2). Responding to my experiences

in/of the situation I engage with the space and materials, documenting my interactions through the various recording devices identified. From week two, I also record thoughts on my iPhone prior to each observation, and annotate photographs in my research journal. Such documentation combines the observation and noting of fleeting thoughts and sensory experience (Milner, 2011), and includes a written account of each observation, as well as personal thoughts, imaginings, associations, and speculations, material ‘things’ and aspects of subjective experience

embedded and

embodied in process.

Phase Three – Engage different audiences in meaning-making

After completion of the twelve-week project, I revisit and re-examine the body of material and documentation produced. Reworking and (re)presenting it in different situations across the arts and/in health and academia, I engage different audiences in the meaning-making process. Such opportunities include an art installation in the host organisation, focus groups with staff, conference presentations and interventions locally and internationally, and meetings with the art psychotherapy community.

Data gathering, production, and analysis

As practitioner-artist-researcher I am situated amidst, rather than separate from, the situation I seek to understand (Schön, 1983, Vear, 2022), concerned with listening, sensing, and imagining, with mulling over practice, and being impressed by a thing – ‘feeling its touch and feeling in response’ (Are, 2018), p. 2. Rather than searching for meanings, patterns or codes through more traditional means, analysis and the construction of meaning takes place as part of the gathering, production, and assemblage of data, as I feel my way forward and into the research situation. While each phase follows on from the other, it is through repeatedly returning to revisit the sites and material of my research, working through the artistic process, and engaging in conversation with the ‘work’ of art, and others, that thoughts, associations, feelings, and affects begin to gather around the making of particular artworks and projects, and significances begin to reach out or ‘glow’ (MacLure, 2013).

Ethics

The study was subject to ethical scrutiny and approval by Sheffield Hallam University Research Ethics Committee and all necessary permissions and consents were gained from the relevant NHS Trusts and others involved in the research.

RESULTS

Results take the form of artworks and artistic projects, written and recorded audio- visual documentation of process, and responses collected through exhibitions, art installations, focus groups, conferences, and other conversations. Collectively, these respond to the research situation as a whole. Detailed accounts and descriptions can be found in my thesis and practice submissions (Michaels, 2022b) and at

https://www.debbiemichaels.co.uk/artworks.php. For the purposes of this paper I identify key artworks and projects in each phase.

Phase One

‘Hung Out to Dry’ (Figure 3a)

Preparing the ground for the participant-observation ‘Hung Out to Dry’ responds to an initial meeting with a potential host. Without any prior concept in mind, the work emerges quickly through a process of using ‘stuff’ I have to hand and moving it from my art (psycho)therapy room to an adjacent space set aside for my research. It is only when I step back to look at the assemblage that the work takes on significance; offering a feel both for the ethical sensitivity surrounding ‘observation’, and what it means to transfer ideas, materials, and attention from art-as/in-therapy to art-as-research.

Figure 3.

a - ‘Hung Out to Dry’. Assemblage, 2015. Table, easel, lamp, string, nails, modroc, light bulb; b - ‘Be│tween’. Multimedia installation, 2016 ‘Testing Testing’ exhibition & symposium, Sheffield Institute of Arts. Video, audio, and other material, 340×150×150, Duration: 50 + 10 minutes (loop).

Figure 3.

a - ‘Hung Out to Dry’. Assemblage, 2015. Table, easel, lamp, string, nails, modroc, light bulb; b - ‘Be│tween’. Multimedia installation, 2016 ‘Testing Testing’ exhibition & symposium, Sheffield Institute of Arts. Video, audio, and other material, 340×150×150, Duration: 50 + 10 minutes (loop).

This project explores and documents the reflexive dialogues that emerge in the spaces between unravelling, reconfiguring, and exhibiting an ‘art-therapy-object’ (not made for public view) in a fine art research context. Staging an encounter with the object’s unravelling, the installation and associated writings (Michaels, 2016b, Michaels, 2016c) reframe practice in a space somewhere between fact and fiction. Although I do not literally re-site the contents of my art (psycho)therapy room, the dilemmas raised by imagining, mulling over, and enacting the unravelling, re-siting, and staging of the work are, nonetheless, real. In the photograph I sit (as the viewer is invited to do) opposite the unravelled ‘art-therapy-object’, watching and listening to the process of its deconstruction (Michaels, 2016a).

Practice Documentation

‘Twelve Weeks: Twelve Hours + Twelve Hours +’ project (Figure 4)

The main body of work emerges through a multi-layered response to the twelve-week participant-observation. This results in a wealth of practice documentation which acts both as further artistic material, and analytical/ critical tools to think with. These include: written accounts of each observation, reflections, drawings, photographs, timelapse, video and audio recordings, digital tracings of journeys travelled, speed, and heartrate, and material remains known as the ‘object-body-thing’.

Figure 4.

- ‘Twelve Weeks: Twelve Hours + Twelve Hours +’, 2017.

Figure 4.

- ‘Twelve Weeks: Twelve Hours + Twelve Hours +’, 2017.

The atmosphere in the rehabilitation setting generally appears settled; still, I experience significant emotional and sensory disturbance. For example, during observation-week-1, I am suddenly overcome with feelings of nausea and disorientation as sounds and voices coming from all directions merge into one nonsensical noise. At other times, I experience isolation, anxiety, sleepiness, and sadness, as well as powerful identifications, emotional disconnection, and impulses to help or leave.

In the studio I begin on impulse, working with the constraints of time and space and the available materials. During early sessions I recount my experiences in/of the rehabilitation setting to the various documentary bodies, as if silent witnesses. At other times their scrutiny feels intrusive, although the audio-recorder remains an empathic listener. The material object-body-thing emerges without prior conception but through the process of grappling with ‘stuff’ in an attempt to understand what I am making and how it responds to the research situation. For example, in studio-session-1, drawn gestures in graphite transition to wire and string drawn across and between nails hammered into the wall, where a network of connections develops, but with ends left dangling. While I do not consciously make a ‘body’, early interactions provoke unexpectedly powerful associations to ‘brain’, ‘gut’, and ‘womb’, and a body imprisoned – ‘pinned to the wall […] unable to move independently’. Building an independent structure alongside evokes thoughts of a conduit or transmitter but is followed by associations to body parts and limbless joints as the repetitive gesture of wrapping it in plaster bandages to make it more robust turns warmth and softness to coldness and rigidity, and emotional deadness overcomes me.

After week-7, the atmosphere shifts dramatically as, presenting ‘raw’ material at a research seminar, I am pressed to ‘disrupt’ my process and break with familiar conventions and languages. While resisting at a conscious level, the experience nonetheless provokes a turning point. Feeling the intense scrutiny of the art-research institution, I cover the cameras and, like a mime artist, change into black clothes and an expressionless mask, entangling myself with the threads of the emerging object-body-thing, unsure to which institution I respond. As the work becomes more performative and entangled, what was once spoken in words becomes unintelligible noise and guttural expressions of rage at my attempts to make some sense of it all. Finally, I liberate the object-body-thing from the wall, strapping it to my body, before separating myself and attaching it to the tall, erect, structure so it stands independently – the black uniform and mask positioned neatly alongside.

Phase Three

‘Interrupting the Flow (Figure 5a)

For ‘Interrupting the Flow’ I move the object-body-thing out of the studio, (re)situating it in the rehabilitation setting, in the place from where I had observed, and invite responses from all present on the day, and in a subsequent focus group with staff.

2 However, moving the material residue evokes surprisingly powerful feelings as I realise that, rather than simply dismantling its parts dispassionately, moving the ‘body’ and (re)presenting it elsewhere requires very careful, sensitive, handling.

Figure 5.

a - ‘Interrupting the Flow’. Installation, 2018 Assessment and Rehabilitation Centre Mixed Media; b - ‘The-voice-of-its-making’. Sound piece, 2018 Double Agency Intervention, Design4Health Conference, Sheffield Hallam University; Audio, duration: 60 minutes.

Figure 5.

a - ‘Interrupting the Flow’. Installation, 2018 Assessment and Rehabilitation Centre Mixed Media; b - ‘The-voice-of-its-making’. Sound piece, 2018 Double Agency Intervention, Design4Health Conference, Sheffield Hallam University; Audio, duration: 60 minutes.

Responses from staff on the day and during a subsequent focus group include those shown in

Figure 5a and range from ‘it’s just a pile of materials’ and ‘I don’t understand it’ to ‘reaching out to something difficult to grasp’ and how uncomfortable and frightening the mask felt – ‘disconnected emotionally’.

‘The-voice-of-its-making’ (Figure 5b)

As part of a conference intervention, delegates are invited to engage with and respond individually to an installation of the object-body-thing with ‘the-voice-of-its-making’; a soundtrack of its construction composed of twelve hours of studio audio-recordings compressed into one hour. For many delegates, the soundtrack distracts and annoys as the conversation is elusive and difficult to follow. For some, the random noises intrude and interfere with a visual, more tactile, appreciation of the material, creating anxiety and tension. For others they disturb, as it is unclear what the sounds are or from where they come, evoking someone in pain, needing help, or trying to escape a situation or body – thoughts that resonate with my own associations, on first listening, to a voice being muffled, gagged, bricked up behind a wall.

Emergent Strands

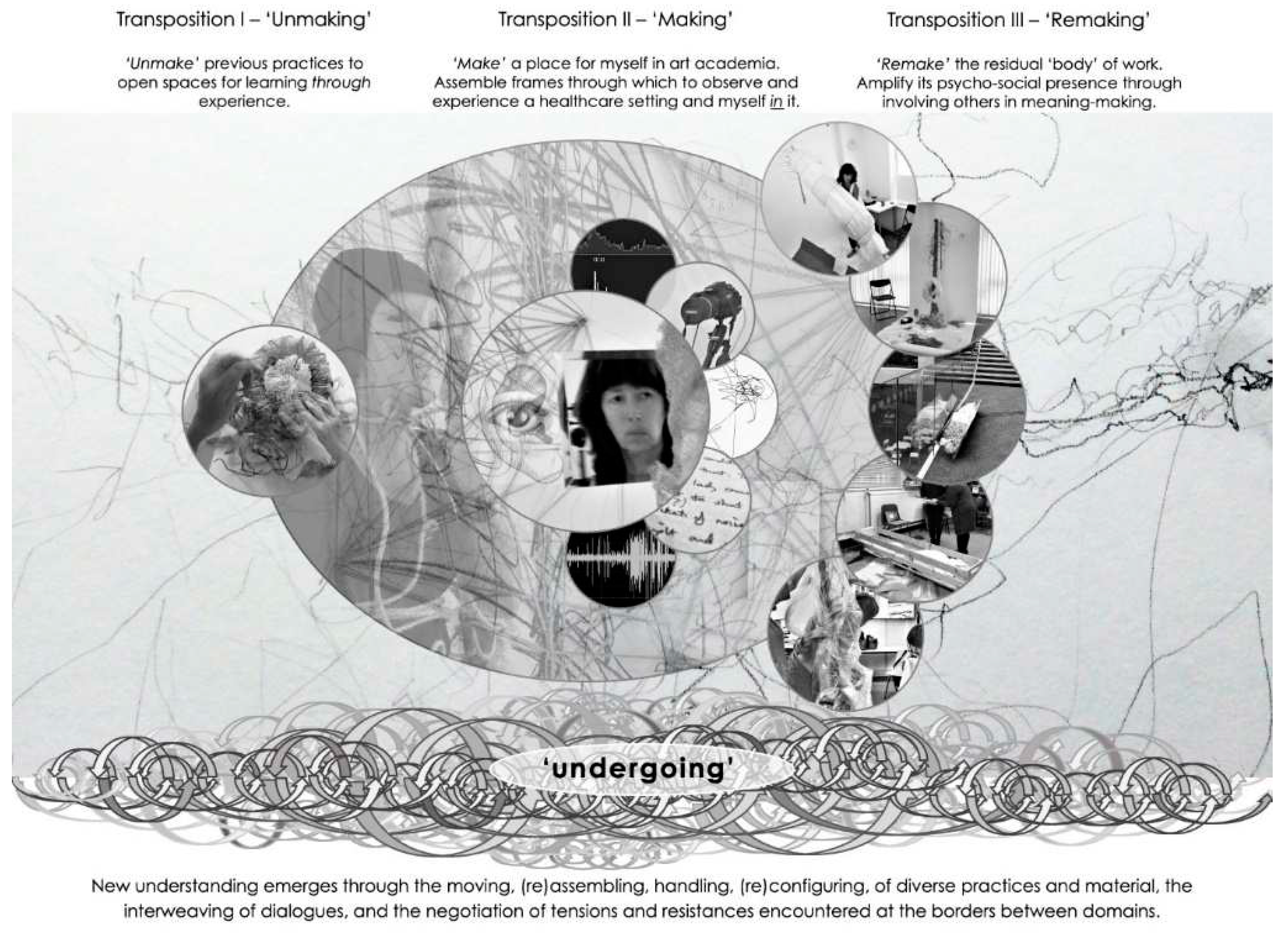

Viewed as a space for imaginative encounter and performative enactment, emergent threads indicate the speculative, entangled, and affective nature of the research process. Two core strands become apparent, encapsulated in

Figure 6. The first is concerned with the reflexivity generated through the moving and handling of practices, materials, situations, ideas, things, emotions, and other ‘bodies’ – conceptualised in three ‘Transpositions’:

unmaking, making, and

remaking. The second strand, deeply entwined with the first in its underpinning of it, is concerned with the reflexive work of

undergoing – conceptualised as an ongoing process of ‘speculative weaving’. This presses me to notice and feel more acutely

into the emotional, affective, and ethical dimensions of the research situation, foregrounding an ethics of responsibility, care, and attention

for/of the body (in various forms) as material moves, and is moved, from one place to another across boundaries. New understanding emerges through the moving, (re)assembling, handling, (re)configuring, of diverse practices and material, the interweaving of dialogues, and the negotiation of tensions and resistances encountered at the borders between domains.

Bound into this transpositional process and speculative weaving are three further gestural actions and practices –

move, make space(s), and take time (see

Table 1 and Michaels, 2022b, pp.226-234). As characteristics or conditions that have facilitated developments in my understanding these actions or guiding principles are embedded and embodied in

undergoing, implicit in which is a capacity to endure and sustain the slow, messy, material, affective, and emotional nature of the ‘work’.

Discussion

Unmake, Make, Remake

Transposition 1 - Unmake

‘Transposition’ implies an exchange of places, a move to a different context, or a change of key. Researching in the arts offers different frames and lenses through which to experience and observe organisational processes (my own included), shifting the emphasis from art as/in therapy to art as a primary mode of enquiry (McNiff, 2018). Nonetheless, the move is not straightforward. Without a fine art background or the familiar codes, conventions, and languages of art (psycho)therapy, I feel like an intruder in a foreign land – unsettled, vulnerable, exposed – and, like the art-therapy-object, unravelled. Nevertheless, engaging in conversation with other artists, researchers, and thinkers through literature and projects such as ‘Be│Tween’, I begin to get a feel for what it means to loosen the threads that hold me in place and open myself to new, unfamiliar, ideas and different ways of thinking.

Transposition 2 - Make

Although familiarity helped facilitate the ‘Twelve Weeks’ project, the observational role is unfamiliar, challenging convention for all concerned and provoking ongoing questions (mainly from staff) about who I am and what I am doing; whether I am ‘doing’ nothing or as one service-user remarks, do I just ‘sit there each week watching the telly’? Pressures from the art institution to ‘disrupt’ my process and break with familiar conventions and languages also unsettle, pressing me to notice and feel into the complexities of the broader research situation more acutely, as I realise how intimately my ‘making’ in response to the rehabilitation service is entangled with the institutional context in which I make.

The studio offers a ‘virtual’ space away from clinical and research settings (albeit connected to them), in/through which to safely explore, test and (re)enact relations, feelings, and thoughts; the various documentary devices observing, witnessing, and absorbing the affective, emotive, and chaotic tensions inherent in the making process (Nash, 2021). More than a bundle of projections the object-body-thing occupies an intermediate area of experiencing (Winnicott, 1991[1971]), ‘alive with gestures and answering forms’, that bear the residue of a living dialogue with me, as artist, and the research situation (Wright, 2009). Gradually, attention moves from something 'made' to the gestural, repetitive, performative nature of some ‘thing’ in the making – an intertwining of 'undergoings' and 'goings on’ through which I access the thinking (Ingold, 2010).

Transposition 3 - Remake

Sharing my sensitivity across disciplinary and professional boundaries I test prior conceptions, opening a space for dialogue through the incorporation of multiple perspectives (Leavy, 2009) and amplifying the psychosocial presence of the ‘body’. Whether through interest, engagement, indifference, dismissal or devaluation, the audience is implicated in the meaning-making process through receiving, handling, and response. This deepens my understanding of the situation, drawing attention to the complex nature of different sites (what they might provoke, enable, activate, or silence), and an ethics of hospitality, responsibility, attention, and care of/for the body. It also offers an insight into how the art is working; revisiting and reworking material reframes experience, giving new texture and meaning to what has gone before as material ‘made’ in the past is ‘remade’ through touching the stuff of new situations in the present, and affective understanding is unmade and remade with each 're' iteration and performance of it.

Similarly, as I revisit and rework the tracings of speed and heartrate what becomes significant is that, during the observation hour, my heartrate slows and no speed is registered, a realisation that ‘glows’ even more strongly in the face of organisational pressures for speed and productivity and to be seen to be ‘doing’.

Learning through Experience

Grounded in a reflexive process of learning through experiences of making, the work of art-as-research is integral to the design of this study, the ‘method’ developing over time. Reflexivity is understood as part of a collective ethos; an ongoing, iterative, affective conversation with the complexities of a situation, including different subjectivities, around which various meanings float (Luttrell, 2019, Probst, 2015). A slow, messy, business this does not happen in a linear, orderly fashion, but through the complex interplay of different elements. Although each transposition foregrounds a primary gesture, each is intricately woven together in a reflexive conversation that repeatedly loops back and over as I feel my way into the situation, slowly moving towards 'knowing how to move forward' (Candy, 2019). More than adding ‘this + that’, the fact that I do ‘this’ as part of ‘this + that’ changes the nature of both as they become part of a new affective assemblage.

Schön stresses the tacit knowledge that is difficult to articulate, but ‘implicit in our patterns of action and in our feel for the stuff with which we are dealing’ (Schön, 1983, p.49). This research tests my capacity to dwell with and in a complex situation and observe its affects. Far from a systematic, mechanical, process, the performative, embodied, embedded, nature of the research demands that I engage in an ongoing reflexive and affective dialogue with the matter at hand; thinking through affect and the intensity of sensory experience evoked as I move, handle, and manipulate things, feel, mull over, imagine, filter, and sort (Massumi, 2015, Barrett, 2012). Feelings, thoughts, and insights emerge at different times, from all directions, the process fraught with tensions, ambivalences, and embarrassments at the borders between domains as I encounter, observe, undergo, and respond to various events and occurrences. Nonetheless, using artistic practice as a research method I come to a deeper understanding, not only of the events and situations I experience, but also the process through which this understanding develops. While documentation and ‘things’ made along the way act as residual evidence that something has taken place, it is through moving, making space(s), and taking time, paying attention to how I administer and document the research process, and working through the ongoing embodied, transferential, process of unmaking, making, and remaking, that new concepts emerge and my understanding is also sophisticatedly moved.

Caveats and Limitations

Like all research, a Ph.D. sets up an artificial frame around an ongoing, evolving process. While the methods outlined here are repeatable, when undertaken by different people under different circumstances such research would be subject to a wide range of variables, producing different, albeit potentially useful, insights. I cannot return to where I was at the time things happened; insights and understandings come with time and space as I work through the research process. Therefore, I can only offer a partial, situated, view of my sensitivity to the research situation with all its inconsistencies and flaws (Haraway, 1988); I rely on working with and through extensive documentation to feel into the material as I produce it although, by its nature, all documentation is selective, incomplete, and abbreviated and, inevitably, excludes.

Mapping clinical concepts and practices onto social or artistic research, or vice versa, is controversial (Holmes, 2014); yet, while psychoanalysis, art (psycho)therapy, and the fine arts do not always lie comfortably together, I suggest that such models are not mutually exclusive and, when assembled differently, may produce new methods and useful ways to approach and consider a situation. By choosing particular sites in/through which to set up, develop, and test out my method, I emphasise the subjective, emotional, and affective dimensions of emergent material which involves the complex negotiation of fact and fiction, memory, reconstruction of events, authenticity, and ethics. Accompanying this is the constant, shadowy, threat of self-absorption (McNiff and Nash, 2017) although, as the artist Grayson Perry remarks, ‘I cannot step outside myself to look around the edges of my own humanity – see the world not through the lens of my own experience and emotions’ (Perry, 26 December 2019). Engaging in reflexivity is a perilous endeavour, full of muddy ambiguity and multiple trails (Finlay, 2002). Nonetheless, alongside well-trodden criticisms of navel-gazing and mirroring fixed positions, lie the considerable challenges of managing the self-doubt and anxiety provoked through questioning, and being questioned by, the dominant voices in myself and the academic (amongst other) institutions. The line between openness and intolerable rawness is difficult to navigate and my vulnerabilities, discomforts, ambivalences, embarrassments, and frustrations are exposed for all to see. This is not exposure for its own sake; rather, it is ‘essential to the argument’ (Behar, 1996, p.31). Indeed, I argue, after Eastwood, that making, sharing, and voicing through the ‘work’ of art in an act of radical vulnerability can support the depth of reflexivity necessary to unsettle established patterns, value systems, and power structures (Eastwood, 2022).

Implications for Practice/Policy/Future Research

As a practice-based research project, grounded in learning through experiences of making, I claim a position in the broad area of reflective practice(s), including response art. Although I gain insights about the organisation, the specific contribution of my research lies in the multiplicity of ideas, strategies, processes, and potential positions through which I explore, examine, and respond to my experiences in/of the research situation as I undergo it; the making process acting as a keen observational tool (Fish, 2023). With creative experience at its heart, it contributes to a growing body of research emphasising the embodied nature of knowing and the value of affective methodologies that include (rather than exclude) subjective experience, imagination, and emotion.

This study also contributes to a broader conversation concerning the application of ABR approaches for art (psycho)therapy. Questioning more traditional approaches, and including the practitioner’s voice, I move attention away from what the art ‘means’ or represents to how it ‘works’ – how it might ‘move’ us toward different positions or understandings (Michaels, 2022a). This broadens the scope from the visual, to the embodied, sensory, performative ‘work’ of art as both site and material with and through which to affectively feel one’s way into human experiences and situations – processes that are at the root of the art (psycho)therapy profession. Moving away from the single, linear, narrative trajectory of a case study, I redirect attention towards an intersubjective approach, assembling and interweaving analytic, aesthetic, social, sensual, and material considerations with creative and imaginative writing, and artmaking around artworks’ (Gilroy, 2006), further extending processes of reflexivity and analysis (McCaffrey and Edwards, 2015, Eastwood, 2022, Skukauskaite et al., 2022).

ABR works to disrupt and unsettle knowing (Talwar, 2018), resisting exclusivity, absolutes, and certainties, and challenging more dominant ideologies (Sullivan, 2010, Nelson, 2013, Gray and Malins, 2004, Barrett and Bolt, 2007, Leavy, 2017). Working across boundaries, this research foregrounds the learning opportunities afforded by assembling and exchanging ideas and practices through artistic practice, placing value on exploring the tensions, ambivalences, embarrassments, and resistances encountered as differences collide, as well as the affective, cultural sensitivity of documentary fragments captured in various voices and media. Drawing attention to how material and understanding is formed through the research process, this study amplifies the significance of ‘transference’ as a method of enquiry, as well as an ethics of hospitality, responsibility, attention, and care. Sitting with and alongside others in conversation, rather than over or above, this speaks to a broader agenda of equality, diversity, and inclusivity through the way we gather, produce, move, handle and analyse data, and how we collaborate with, and represent, our research subjects.

Conclusion

Kapitan suggests that ‘art therapy research primarily involves the discipline of learning how to observe, how to place our observations in context so that we can see more accurately, and how to return again and again to the evidence we see in order to validate our understandings.’(Kapitan, 2010, p.2). As a site for affective reflexivity through which one may be pressed to notice and feel more acutely, and drawing particular attention to an ethics of responsibility, attention, and care for/of the body, the research value lies in the capacity of this method to embrace complex relationalities, and engage our imaginative, emotional, and ethical sensibilities in ways that may not emerge through more traditional approaches to reflective/reflexive practice(s). It is therefore relevant, not only for practitioners and researchers working across the humanities as well as arts and/in healthcare but also for those affected by, and in receipt of, the care that is delivered.

Funding

The doctorate was funded by the author, however certain projects received funding from Sheffield Hallam University through a researcher-led activities fund.

Notes on contributors

Dr Debbie Michaels is an HCPC registered art (psycho)therapist and associate lecturer on the Sheffield-based training course, with whom she has been involved since 2006. After a first career as an interior designer in the 1980’s, and following a period of illness, she subsequently began an intense period of personal change and professional retraining, undertaking a master’s degree in the psychoanalysis of groups and organisations in the late 1990’s. After reconnecting with her interest in art, this led her to pursue a second career in art (psycho)therapy, as practitioner and, later, as educator. She has contributed to the literature in psychoanalysis, art (psycho)therapy, and practice-based research in the arts, and has recently completed an art-based doctorate at Sheffield Hallam University. Her research interests lie with reflexive art practice as a research methodology and how this may enhance and amplify sensitivity to the affective dimensions of human situations and experience. Her clinical work is mainly based in private/independent practice and she supports and supervises art therapists working across a broad range of client groups and organisational settings.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the author, Debbie Michaels, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The author extends her sincere appreciation and thanks to all those who (knowingly or otherwise) have contributed to, and supported this research, without whom it would not have been possible.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- ARE, K. 2018. Touching stories: Objects, writing, diffraction and the ethical hazard of self-reflexivity. TEXT: Journal of Writing and Writing Courses, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- BARAD, K. 2007. Meeting the universe halfway: quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning, Durham, N.C., Duke University Press, Table of contents only http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip0619/2006027826.html.

- BARONE, T. & EISNER, E. W. 2012. Arts based research, London, Sage.

- BARRETT, E. 2012. Materiality, Affect, and the Aesthetic Image. Carnal Knowledge: Towards a 'New Materialism' through the Arts. London: I B Taurus.

- BARRETT, E. & BOLT, B. (eds.) 2007. Practice as Research: Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry, London: I.B.Taurus.

- BEHAR, R. 1996. The Vulnerable Observer: Anthropology that Breaks your Heart, Boston, Beacon Press.

- BOLTON, G. 2010. Reflective practice: Writing and professional development, London, Sage.

- BOUD, D., KEOGH, R. & WALKER, D. 2013. Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning, Oxon, Routledge.

- BOUD, D. & WALKER, D. 1998. Promoting reflection in professional courses: The challenge of context. Studies in Higher Education, 23, 191–206. [CrossRef]

- BUNTING, M. 2020. Labours of Love: The Crisis of Care, London, Granta Books.

- CANDY, L. 2019. The Creative Reflective Practitioner: Research Through Making and Practice, London, Routledge.

- CANDY, L., EDMONDS, E. & VEAR, C. 2022. Practice-Based Research. In: VEAR, C. (ed.) Routledge International Handbook of Practice-Based Research. London: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- CAZEAUX, C. 2008. Inherently interdisciplinary: four perspectives on practice-based research. Journal of Visual Art Practice, 7, 107–132. [CrossRef]

- COLLIER, K. 2010. Re-imagining reflection: Creating a Theatrical Space for the Imagination in Productive Reflection. In: HELEN BRADBURY, N. F., SUE KILMINSTER, MIRIAM ZUKAS (ed.) Beyond Reflective Practice: New approaches to Professional Lifelong Learning. London: Routledge.

- COOPER, A. & LOUSADA, J. 2005. Borderline welfare: Feeling and fear of feeling in modern welfare, London, Karnac.

- DOLPHIJN, R. & VAN DER TUIN, I. 2012. New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies, MI, Open Humanities Press, http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.11515701.0001.001.

- EASTWOOD, C. 2022. Finding Reconnection: Using Art-based intersectional self-reflexivity to ignite profession based community care in the arts therapies during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 80. [CrossRef]

- ETHERINGTON, K. 2004a. Becoming a Reflexive Researcher-Using Our Selves in Research, London & Philadelphia, Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- ETHERINGTON, K. 2004b. Research methods: Reflexivities-roots, meanings, dilemmas. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 4, 46–47. [CrossRef]

- FINLAY, L. 2002. Negotiating the swamp: the opportunity and challenge of reflexivity in research practice. Qualitative research, 2, 209–230. [CrossRef]

- FINLAY, L. 2008. Reflecting on Reflective Practice. Practice-based Professional Learning Paper 52. The Open University.

- FISH, B. J. 2012. Response art: The art of the art therapist. Art Therapy, 29, 138–143. [CrossRef]

- FISH, B. J. 2023. Response art: A resource for practice and supervision, in person and online. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 14, 73-84. [CrossRef]

- FOX, N. J. & ALLDRED, P. 2016. Sociology and the new materialism: Theory, research, action, London, Sage. [CrossRef]

- FREUD, S. 2001. Recommendations to physicians practicing psycho-analysis (1912). In: STRACHEY, J. (ed.) The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud: Case History of Schreber, Papers on Technique and Other Works, Volume XII (1911-1913). London: Vintage.

- GILROY, A. 2006. Art therapy, research and evidence-based practice, London, Sage.

- GRAY, C. & MALINS, J. 2004. Visualizing research: A guide to the research process in art and design, Aldershot, Hampshire, Ashgate Publishing.

- GREGORY, Z. 2021. The page as place: how we enter into images as place. International Journal of Art Therapy, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- HARAWAY, D. 1988. Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14, 575–599. [CrossRef]

- HEALEY, J. 2015. Exploring the emotional landscapes of placement learning in occupational therapy education. Ph.D. Thesis, Sheffield Hallam University.

- HINSHELWOOD, R. D. 2002. Applying the observational method: observing organizations. In: BRIGGS, A. (ed.) Surviving space: papers on infant observation. London: Karnac.

- HINSHELWOOD, R. D. 2013. Observing Anxiety: A psychoanalytic training method for understanding organisations. In: LONG, S. (ed.) Socioanalytic Methods: Discovering the Hidden in Organisations and Social Systems. London: Karnac Books.

- HINSHELWOOD, R. D. & SKOGSTAD, W. (eds.) 2000. Observing Organisations: Anxiety, defence and culture in health care, London: Routledge.

- HOGAN, S. & PINK, S. 2010. Routes to interiorities: Art therapy and knowing in anthropology. Visual Anthropology, 23, 158–174. [CrossRef]

- HOLMES, J. 2014. Countertransference in qualitative research: a critical appraisal. Qualitative Research, 14, 166–183. [CrossRef]

- HOLMES, M. 2010. The emotionalization of reflexivity. Sociology, 44, 139–154. [CrossRef]

- HUET, V. 2012. Creativity in a cold climate: Art therapy-based organisational consultancy within public healthcare. International Journal of Art Therapy, 17, 25–33. [CrossRef]

- HUET, V. & KAPITAN, L. (eds.) 2021. International Advances in Art Therapy Research and Practice: The Emerging Picture: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- INGOLD, T. 2010. The textility of making. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 34, 91–102.

- KAIMAL, G., ARSLANBEK, A. & MALHOTRA, B. 2022. Approaches to research in art therapy. Foundations of Art Therapy. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- KAPITAN, L. 2010. Power, reflexivity, and the need to complicate art therapy research. Art Therapy, 27, 2-3. [CrossRef]

- KAPITAN, L. 2018. Introduction to art therapy research, Hove & New York, Routledge.

- KENNY, K. & GILMORE, S. 2014. From research reflexivity to research affectivity: Ethnographic research in organizations. The Psychosocial and Organization Studies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [CrossRef]

- KNUDSEN, B. T. & STAGE, C. (eds.) 2015. Affective Methodologies: Developing Cultural Research Strategies for the Study of Affect, Basingtoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- LEARMONTH, M. & HUCKVALE, K. 2012. The feeling of what happens: A reciprocal investigation of inductive and deductive processes in an art experiment. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 3, 97-108. [CrossRef]

- LEAVY, P. 2009. Method meets art: Arts-based research practice, New York, Guilford Press.

- LEAVY, P. (ed.) 2017. Handbook of arts-based research, New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- LINESCH, D. 1995. Art therapy research: Learning from experience. Art Therapy, 12, 261-265. [CrossRef]

- LUTTRELL, W. 2019. Reflexive qualitative research. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education.

- MACLURE, M. 2013. The wonder of data. Cultural Studies? Critical Methodologies, 13, 228–232.

- MAHONY, J. E. 2009. 'Reunion of broken parts'(Arabic a/-jabr): A therapist's personal art practice and its relationship to an NHS outpatient art psychotherapy group: an exploration through visual arts and crafts practice. Goldsmiths, University of London.

- MALCHIODI, C., A. 2017. Creative Arts Therapies and Arts-based Research. In: LEAVY, P. (ed.) Handbook of arts-based research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- MASSUMI, B. (ed.) 2015. Politics of affect, Cambridge: Politiy Press.

- MCCAFFREY, T. & EDWARDS, J. 2015. Meeting art with art: Arts-based methods enhance researcher reflexivity in research with mental health service users. Journal of Music Therapy, 52, 515-532. [CrossRef]

- MCINTOSH, P. 2010. Action research and reflective practice: Creative and visual methods to facilitate reflection and learning, Abingdon, Routledge.

- MCNIFF, S. 2008. Art-based research. In: L.COLE, J. G. K. A. A. (ed.) Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications.

- MCNIFF, S. 2017. Philosophical and practical foundations of artistic inquiry: crating paradigms, methods and presentations based in art. In: LEAVY, P. (ed.) Handbook of arts-based research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- MCNIFF, S. 2018. Doing art-based research: An advising scenario. Using art as research in learning and teaching: Multidisciplinary approaches across the arts, 79-89.

- MCNIFF, S. & NASH, G. 2017. In Conversation with Shaun McNiff: Art-based Research. The British Association of Art Therapists: Newsbriefing 20-23.

- MICHAELS, D. 2015. Art therapy in brain injury and stroke services: a glimpse beneath the surface of organisational life. In: WESTON, M. L. A. S. (ed.) Art Therapy with Neurological Conditions. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- MICHAELS, D. 2016a. Be│tween. Testing Testing, Sheffield Institute of Arts: Sheffield Hallam University, Art and Design Research Unit.

- MICHAELS, D. 2016b. Between. In: DAY, M. & RAY, J. (eds.) Testing Testing: Prologue (Vol. 1). Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University, Art and Design Research Unit.

- MICHAELS, D. 2016c. A Constructed Fiction. In: DAY, M. & RAY, J. (eds.) Testing Testing: Dialogue (Vol. 2). Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University, Art and Design Research Unit.

- MICHAELS, D. 2022a. Organisational Encounters and Speculative Weavings: Questioning a Body of Material. In: VEAR, C. (ed.) Routledge International Handbook of Practice-Based Research. London: Routledge.

- MICHAELS, D. A. 2022b. Organisational Encounters and Reflexive Undergoings: A Speculative Weaving in Three Transpositions. Ph.D. Thesis, Sheffield Hallam University, http://shura.shu.ac.uk/31989/.

- MICHAELS, J. 2022c. Interdisciplinary Perspectives in Practice-based Research. In: VEAR, C. (ed.) Routledge International Handbook of Practice-Based Research. London: Routledge.

- MILNER, M. 2010 [1950]. On Not Being Able To Paint, Hove, Routledge. [CrossRef]

- MILNER, M. 2011. A life of one's own, Hove, Routledge.

- NASH, G. 2020. Response art in art therapy practice and research with a focus on reflect piece imagery. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25, 39–48. [CrossRef]

- NASH, G. 2021. The Principles of an Art-Based Research Design: Response Art and Art Therapy Research. In: HUET, V. & KAPITAN, L. (eds.) International Advances in Art Therapy Research and Practice: The Emerging Picture. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- NELSON, R. 2013. Practice as research in the arts: principles, protocols, pedagogies, resistances, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

- PERRY, G. 26 December 2019. Guest Editor. Today Programme. BBC.

- POLANYI, M. 1966. The Tacit Dimension, Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press.

- PROBST, B. 2015. The eye regards itself: Benefits and challenges of reflexivity in qualitative social work research. Social Work Research, 39, 37–48. [CrossRef]

- ROGERS, M. 2002. Absent figures: A personal reflection on the value of art therapists own image-making. International Journal of Art Therapy: Inscape, 7, 59–71. [CrossRef]

- RYAN, M. 2014. Reflexivity and aesthetic inquiry: Building dialogues between the arts and literacy. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 13, 5–18.

- SADE, G. J. 2022. The Relationship between Practice and Research. In: VEAR, C. (ed.) Routledge International Handbook of Practice-Based Research. London: Routledge.

- SCHÖN, D. A. 1983. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action, New York, NY, Basic Books.

- SKUKAUSKAITE, A., YILMAZLI TROUT, I. & ROBINSON, K. A. 2022. Deepening reflexivity through art in learning qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 22, 403-420. [CrossRef]

- SULLIVAN, G. 2010. Art practice as research: Inquiry in visual arts, London, Sage.

- TALWAR, S. K. 2018. Art therapy for social justice: Radical intersections, New York, NY, Routledge.

- TOWNSEND, P. 2019. Creative States of Mind: Psychoanalysis and the Artist’s Process, London, Routledge.

- VEAR, C. (ed.) 2022. Routledge International Handbook of Practice-Based Research, London: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- WALKER, M. B. 2016. Slow Philosophy: Reading Against the Institution, London, Bloomsbury.

- WINNICOTT, D. W. 1991[1971]. Playing and Reality, London, Routledge.

- WRIGHT, K. 2009. Mirroring and attunement: Self-realization in psychoanalysis and art, Hove, Routledge.

| 1 |

I undertook my art (psycho)therapy training placement here from 2003-2005. |

| 2 |

The title references the interruption to the flow of usual processes and routines; whether through an interruption to blood flow as with stroke, my observational presence in the organisation, or an interruption that opens a space to see something differently. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).