Submitted:

07 November 2023

Posted:

08 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. India’s Energy Policy

2.1. India’s Macroeconomics

2.2. India’s Energy Policy

- “Target 500 GW of non-fossil electricity capacity by 2030”

- “Renewable energy contribution of 50% of its electricity demands by 2030”.

- “Forecasted decrease of CO2 emissions by one billion tonnes from present to 2030”.

- “Decline by 45% of the CO2 intensity of the economy by 2030, referenced with 2005 emissions”.

- “The zero carbonisation goals by 2070”

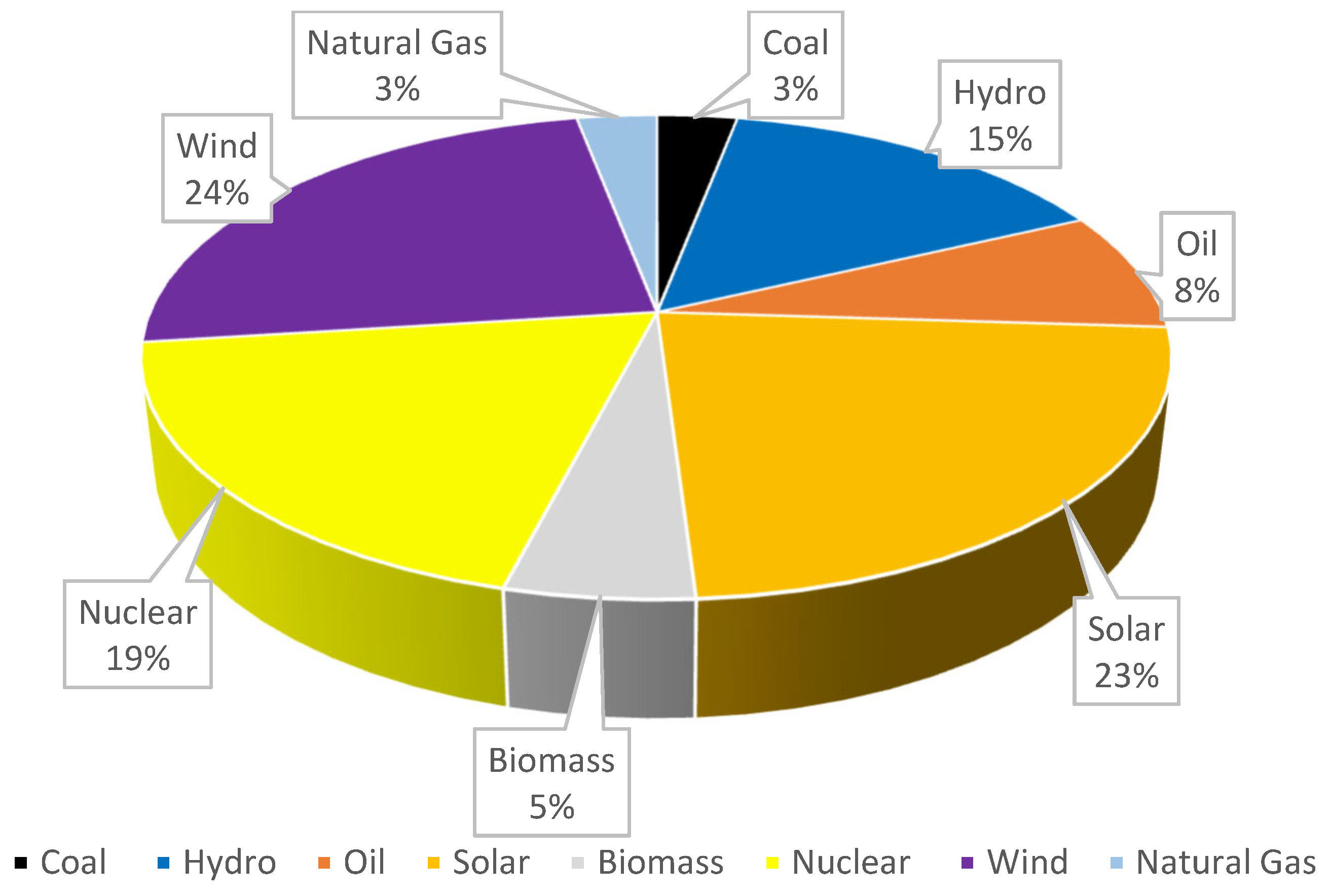

3. China

3.1. China’s Macroeconomics

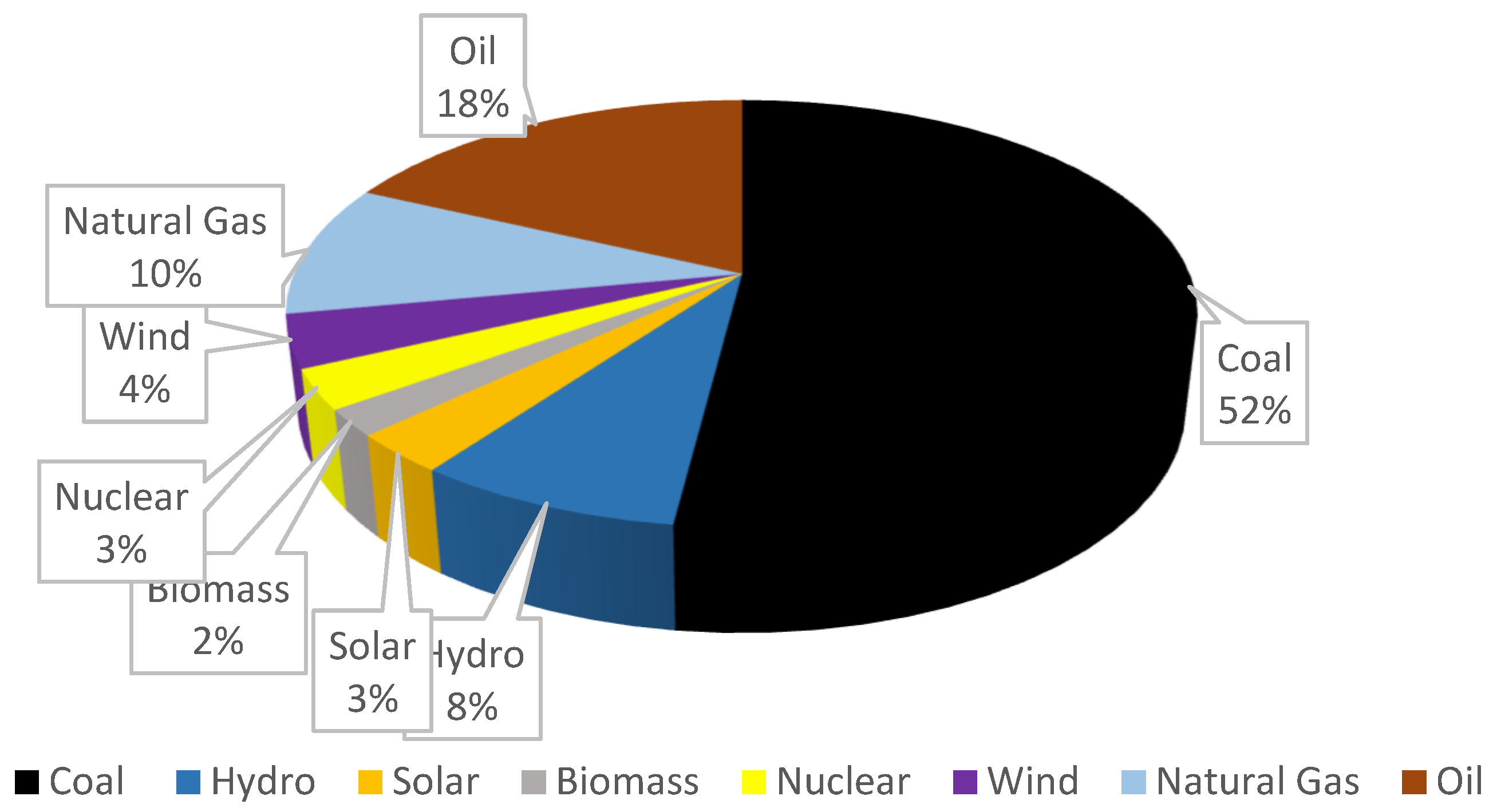

3.2. China’s Energy Policy

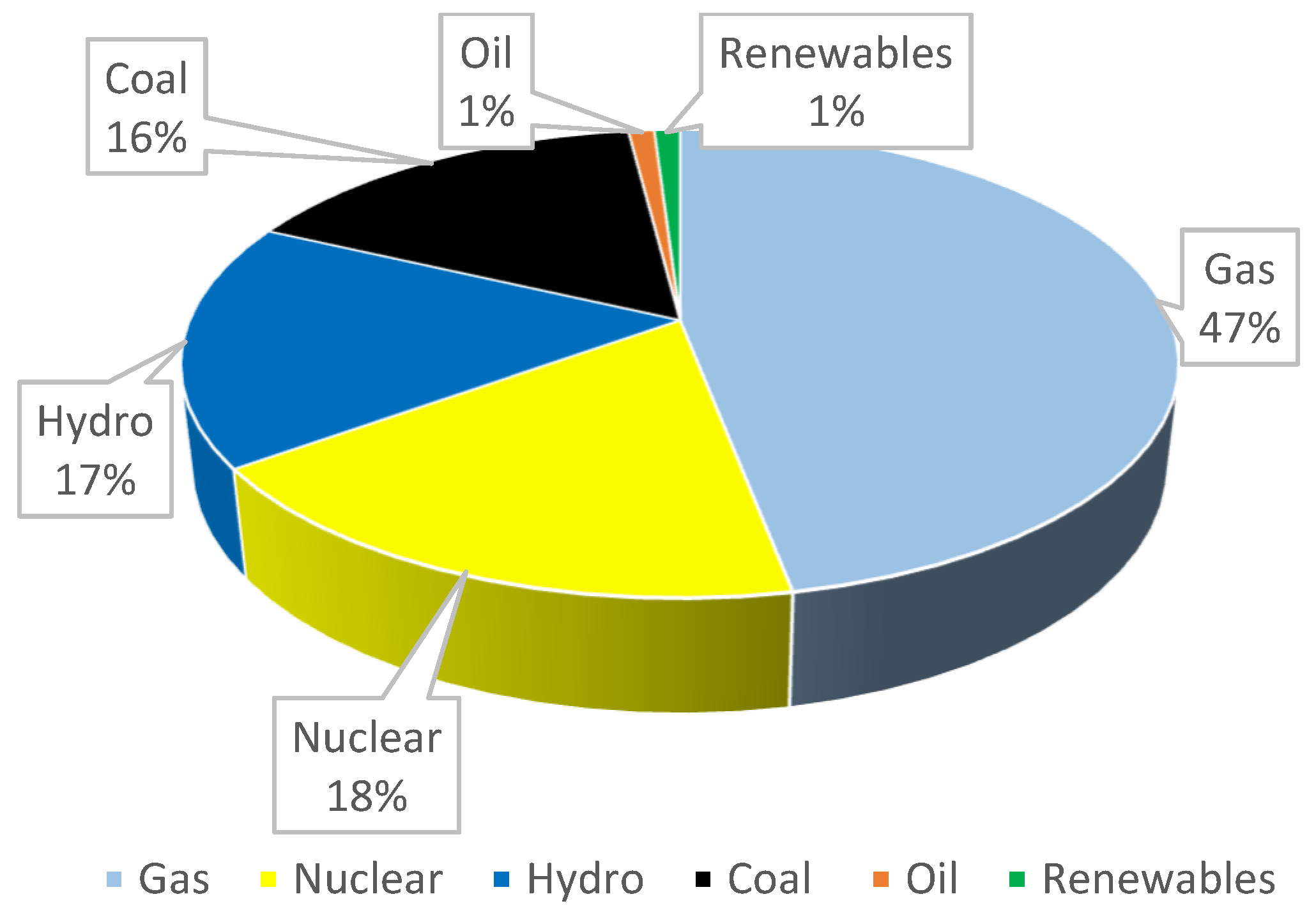

4. Russia

4.1. Russia’s Macroeconomic

4.2. Russia’s Energy Policy

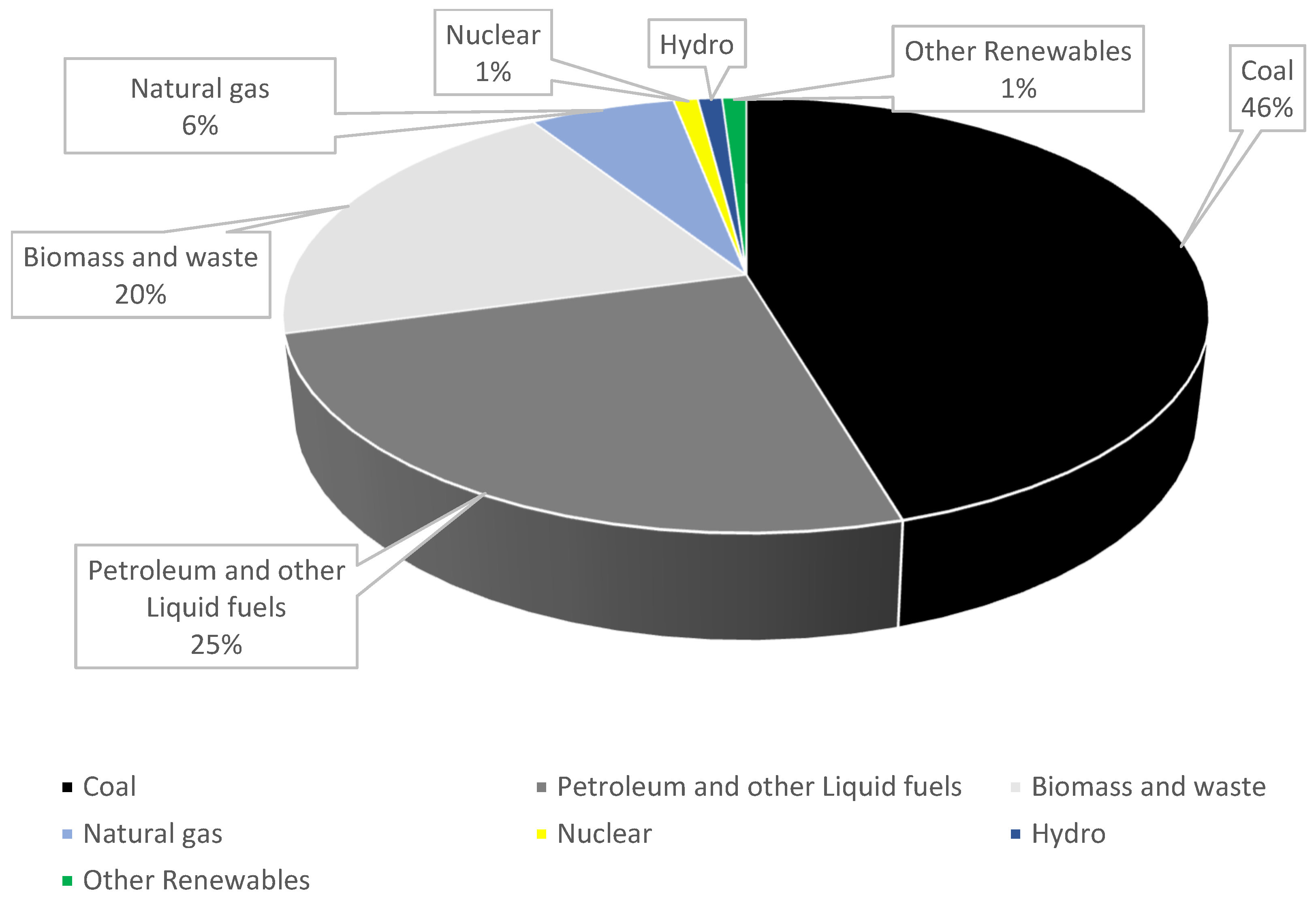

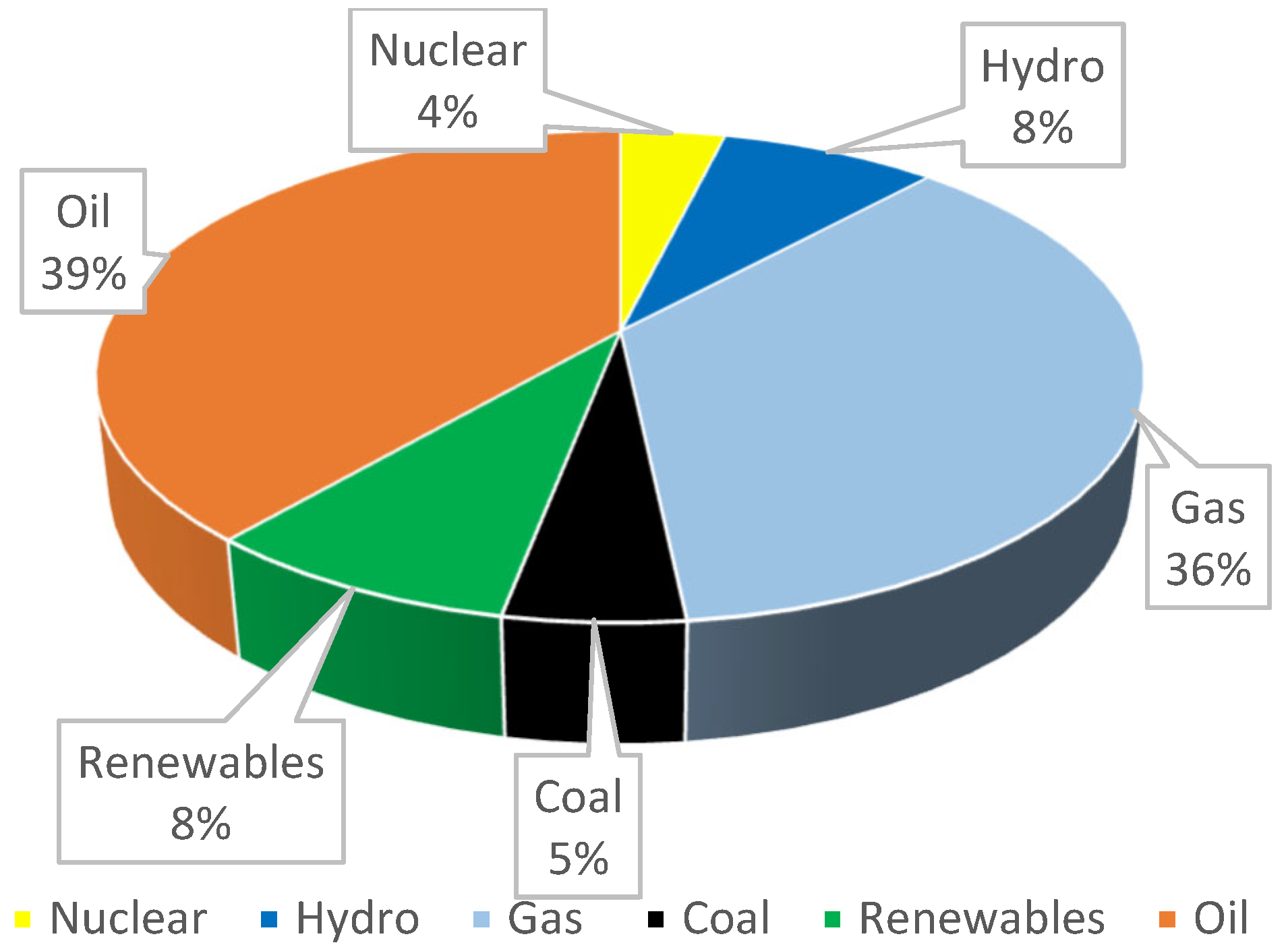

5. Brazil’s Energy Policy

5.1. Brazil’s Macroeconomics

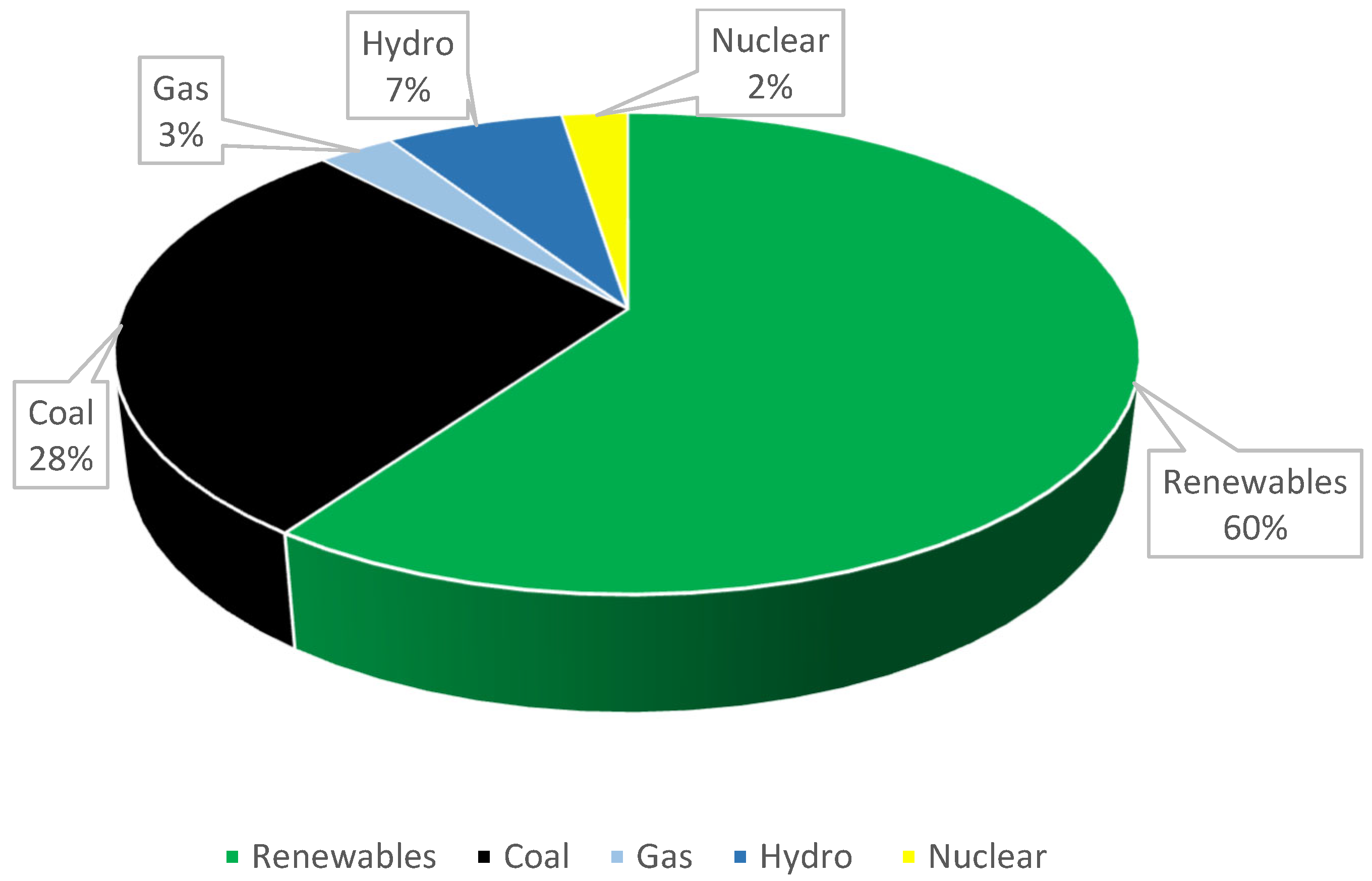

5.2. Brazil’s Energy Policy

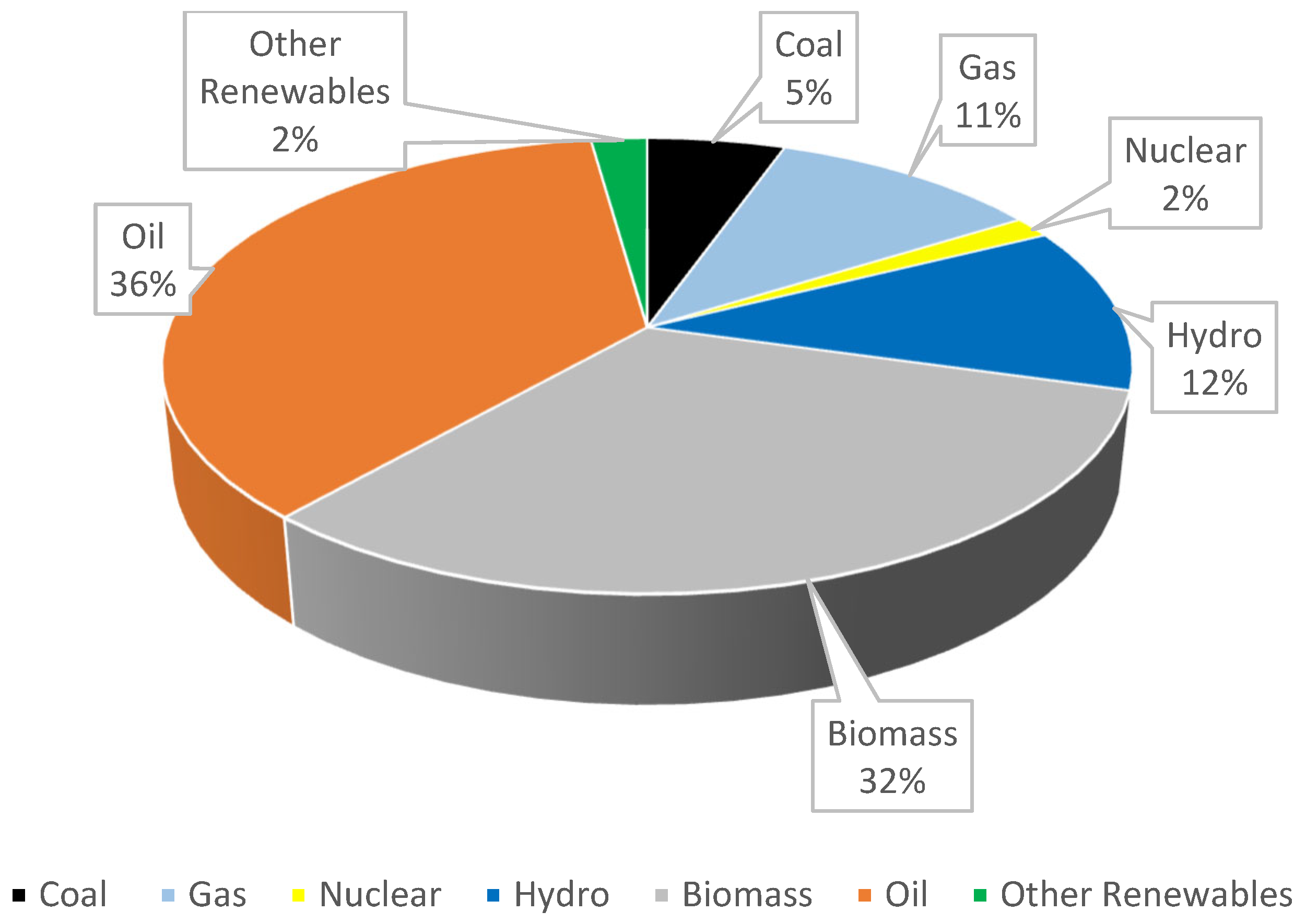

6. History of Energy Policy in SA

6.1. South Africa’s Social and Economic Context in Comparison with the Rest of the BRICS Partners

6.2. South Africa’s Macroeconomics

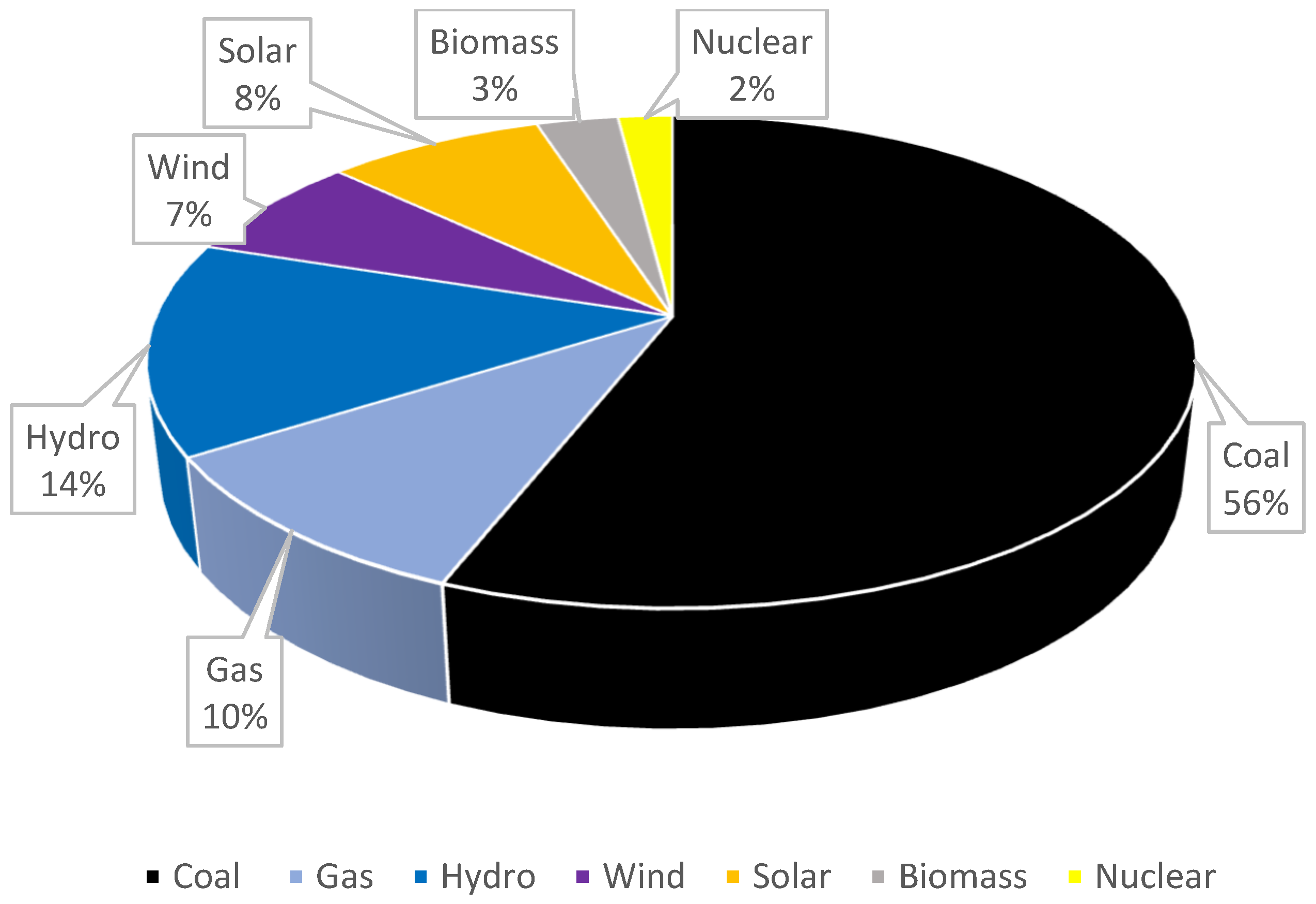

6.3. Current Energy Mix in South Africa

6.4. Insight into the “Just” Energy Transition in South Africa

7. Conclusion and Policy Implications

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morazan, P., Knoke. I., Knoblauch, D., Schafer, T., (2012). The Role of BRICS in the Developing World, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EXPO-DEVE_ET(2012)433779.

- JSP, (2018). BRICS https://www.statssa.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/BRICS-JSP-2018.pdf.

- IMF, (2011a:8). New Growth Drivers for Low-Income Countries: The Role of BRICS. https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2011/011211.pdf.

- World Economic Forum (WEF), (2021). https://www.weforum.org/reports/annual-report-2021-2022/.

- Macroeconomic Outlook Report: India, (2023). https://www.globaldata.com/store/report/india-pestle-macroeconomic-analysis-2/.

- IEA, (2021). India Energy Outlook. https://www.iea.org/reports/india-energy-outlook-2021.

- COP26, (2021). The Glasgow Climate Pact, UN Climate Change Conference, United Kingdom. https://www.efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://ukcop26.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/COP26-Presidency-Outcomes-The-Climate-Pact.pdf.

- NEP-India, (2022). National Electricity Plan of India. https://powermin.gov.in/en/content/national-electricity-plan-0.

- Kaur, R., Pandey, P., (2021). Air Pollution, Climate Change, and Human Health in Indian Cities. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2021.705131/full.

- Agarwal, S., Mani, S., Aggarwal, D., Hareesh, C., Ganesan, K., Jain, A., (2020). Awareness and Adoption of Energy Efficiency in Indian Homes. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water. https://www.ceew.in.

- Mani, S., Agarwal, S., Ganesan, K., Jain, A., (2020). State of Electricity Access in India: Insights from the India Residential Energy Survey (IRES) 2020. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water. https://www.ceew.in/publications/state-electricity-access-india.

- Aklin, M., Harish, S.P., Urpelainen, J., (2015). Quantifying slum electrification in India and explaining local variation. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/115751/.

- Chandran, R., (2018). Forced to walk miles, India water crisis hits rural women hardest. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-water-women-idUSKBN1K318B.

- Macroeconomic Outlook Report: China, (2023). https://www.globaldata.com/data-insights/macroeconomic/china-macroeconomic-country-outlook/.

- IEA, (2021). An Energy Sector Roadmap to Carbon Neutrality in China. https://www.iea.org/reports/an-energy-sector-roadmap-to-carbon-neutrality-in-china.

- Chang, S., Zhuo, J., Meng, S., Qin, S., (2016). Clean Coal Technologies in China: Current Status and Future Perspectives. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2095809917300814?via%3Dihub.

- Chen, Y., (2018). Comparing North-South Technology Transfer and South-South Technology Transfer: The Technology Transfer Impact of Ethiopian Wind Farms, Energy Policy. [CrossRef]

- Hasanbeigi, A., Becqué, R., Springer, C., (2019). Curbing Carbon from Consumption: The Role of Green Public Procurement, Global Efficiency Intelligence. https://www.climateworks.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Green-Public-Procurement-Final-28Aug2019.pdf.

- Korsunskaya, D., Marrow, A., (2023). Russia Raises 2023 GDP Growth Forecast, Longer-term Outlook Worsens. https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/russian-economy-ministry-improves-2023-gdp-growth-forecast-2023-04-14/.

- Henderson, J., Mitrova T., (2017). Natural Gas Pricing in Russia Between Regulation and Markets. SKOLKOVO Centre, Russia. https://energy.skolkovo.ru/downloads/documents/SEneC/research02.pdf.

- ERI RAS, (2019). Global and Russian Energy Outlook up to 2040. https://www.eriras.ru/files/forecast_2016.pdf.

- Mitrova, T., (2019). Energy Transition in Russia, Moscow, Russia. [CrossRef]

- Macroeconomic Outlook Report: Brazil, (2023). https://www.globaldata.com/data-insights/macroeconomic/brazil-macroeconomic-country-outlook/.

- IEA, (2018). Coal Analysis and Forecasts. https://www.iea.org/coal2018.

- Staffell, I., Jansen, M., Chase, A., Cotton, E., Lewis, C., (2018). Energy Revolution: Global Outlook. Selby, Drax .https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=related:4ocQEJoNd7AJ.

- Grushevenko, E., Mitrova T., Malov A., (2018). The Future of Russian Oil Production: Life Under Sanctions SKOLKOVO Energy Centre. https://energy.skolkovo.ru/downloads/documents/SEneC/research04-en.pdf.

- Ratner, S., Berezin, A., Gomonov, K., Serletis, A., Sergi, BS., (2021). What is Stopping Energy Efficiency in Russia? Exploring the Confluence of Knowledge, Negligence, and Other Social Barriers in the Krasnodar Region. [CrossRef]

- Wills, W., Westin, FF., (2019). Energy Transition in Brazil. https://www.climate-transparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Brazilian-Policy-Paper-En.pdf.

- Karpavicius, LM., (2021). Brazil Sources 45% of its Energy from Renewables, Brazil. https://www.climatescorecard.org/2021/01/brazil-sources-45-of-its-energy-from-renewables.

- Sewalk, S., (2015). Brazil’s Energy Policy and Regulations, Brazil. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26195861.

- Ambiente Energia., (2018). MME Authorizes the Installation of 25 Clean Energy Plants to Generate 883 MW, Brazil. https://www.ambienteenergia.com.br/index.php/2018/09/governo-autoriza-instalacao-de-25-usinas-geradoras-de-energia-limpa/34721#.W5r1BOhKiUk.

- ABDI., (2014). Mapping of the Production Chain of the Wind Industry in Brazil. https://www.investimentos.mdic.gov.br/public/arquivo/arq1410360044.pdf.

- ILO., (2015). https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---actrav/documents/publication/wcms_826060.pdf.

- Agência Brazil., (2018). Increase Percentage of Biodiesel Takes Effect, Brazil. https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/economia/noticia/2018-03/aumento-para-10-do-percentual-de-biodiesel-no-diesel-entra-em-vigor.

- Macroeconomic Outlook Report: South Africa, (2023). https://www.globaldata.com/data-insights/macroeconomic/south+africa-macroeconomic-country-outlook/.

- ABEEólica., (2018). Wind Energy is Expected to Generate Jobs in Brazil by 2026. Brazil. https://abeeolica.org.br/noticias/estudo-abdi-ventos-que-trazem-empregos.

- Lawrence, A., (2020). South Africa’s Energy Transition. Wits School of Governance, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa.

- Malumbazo, N., (2020). A New Normal; Coal. SANEA Energy Webinar, 06 August 2020.

- Central Electricity Authority (CEA), 2022. https://cercind.gov.in/2022/draft_reg/Sharing-Regulations_Amend-2022/CEA%20COMMENTS.pdf.

- Juodaityte, J., (2011). Microalgal Biotechnology for Carbon Capture and Bioenergy Production. Eskom, Research and Innovation Report, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- Ritchie, H., Roser, M., (2017). CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-other-greenhouse-gas-emissions#future-emissions.

- Hirsch, T., Matthess, M., Dr. Funfgelt, J., (2017). Guiding Principles and Lessons Learnt for a Just Energy Transition in the Global South. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Berlin, Germany.

- Naidoo, C., (2019). Transcending the Interregnum: Exploring How Financial Systems Relate to Sustainability Transition Processes. University of Sussex, Business School, UK.

- PCC, (2021). Laying the Foundation for A Just Transition Framework For South Africa. https://www.climatecommission.org.za.

- Condor, J., Unatrakarn, D., Asghari, K., Wilson, M., (2011). Current Status of CCS Initiatives in the Major Emerging Economies. https://pdf.sciencedirectassets.com/277910/1-s2.0-S1876610211X00036.

- Melnikov, Y., Mitrova, T., (2019). A carbon-free world: What is Russia’s response? Energy Centre, SKOLKOVO Business School, Moscow, Russia. https://www.cairn.info/revue-responsabilite-et-environnement-2019-3-page-128.htm.

- Grattan,S., (2022). Brazil's 2021 climate emissions. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/brazils-2021-climate-emissions-highest-since-2006-report-says-2022-11-01/.

- Drummond, C., (2016). Understand How Light for All Works, Brazil. https://www.cartacapital.com.br/especiais/infraestrutura/entenda-como-funciona-o-luz-para-todos.

- Halsey, R., Schubert, T., Maguire, G., Lukuko, T., Worthington, R., McDaid, L., (2020).Energy Sector Transformation in South Africa. Project 90 by 2030, Cape Town, South Africa. https://www.90by2030.0rg.za.

- Globaldata Country Risk Index (GCRI, 2023). https://www.globaldata.com/store/report/global-economic-risk-quarterly-analysis/.

| Country | Area of Countr (1000 sq.km) | Population (million person) | Life Expectancy in years | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 8516 | 208 | 76 | 1.2% |

| Russia | 17125 | 147 | 71.9 | 2.1% |

| India | 3287 | 1269 | 68.7 | 6.7% |

| China | 9600 | 1386 | 76.3 | 4.5% |

| South Africa | 1221 | 59 | 64 | 2.1% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).