1. Introduction

Novel foods, as defined by the European Union (EU), encompass plant-based, microbial, fungal, algal, and animal-derived products that have not been traditionally consumed in significant quantities by humans (European Union definition, 1997). This category also includes newly created foods not traditionally consumed in the EU but established as part of diets outside the EU [

1].

European regulation governing novel foods has been in effect since January 2018, established through Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament. This regulation outlines the procedures for authorizing and commercially circulating novel foods [

2]. Additionally, the Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/2470 determines which products qualify as novel foods [

3], aligning with Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and the Council. This regulation has undergone amendments from 2018 to 2023, providing a comprehensive list of authorized new foods in the EU, specifying their names, conditions of use, specifications, and necessary consumer information. Authorization for novel foods requires confirmation that a product has a history of consumption in human food within the European Union before May 15, 1997, and consultation and verification by the Commission of Member States. The verification process, as detailed in Regulation (EU) 2018/456 of the Commission, adheres to the phases of consultation specified in Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and the Council. Furthermore, novel foods must undergo safety evaluation by the EFSA prior to marketing authorization [

2].

The “Catalogue of Novel Foods” serves as a guidance document, providing a non-exhaustive list of products that fall within the novel food standard. This catalogue results from ongoing discussions within the Novel Foods Working Group at EFSA, involving experts from Member States and representatives from the European Commission [

4].

Since 2018, the number of novel food applications scientifically evaluated by EFSA has considerably increased due to the new harmonized European regulatory framework. Factors such as provisions that enhance competition and the evolving societal needs contribute to this heightened activity [

5].

In recent years, edible insects have gained recognition as a more sustainable source of protein compared to other animal-derived proteins. They are being considered a future food and could soon be found in supermarkets and utilized by the food industry as ingredients.

The consumption of insects (entomophagy) in European diets is not only a growing trend but also a new food culture, particularly since the EFSA’s 2015 publication on risk assessment related to insect production and consumption. This assessment stressed the need for separate evaluations of biological and chemical hazards, along with data collection due to the insufficient information available [

6].

Countries are responsible for regulating their markets, and food agencies play a crucial role in this process. In Spain, the Institutional Commission of the Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition (AESAN) communicated in 2022 [

7] that the marketing of insects could be authorized as a novel food or through notification as a traditional food from a third country with a consumption history of at least 25 years.

An example of this is the acceptance of

Locusta migratoria and dried

Tenebrio molitor larvae as new foods in 2021, specified in Execution Regulation (EU) 2021/882 of the Commission [

8].

Acheta domesticus and

Tenebrio molitor larvae were authorized for commercialization in frozen, dried, and powdered forms through Regulations 2021/1975 [

9], 2022/169 [

10], and 2022/188 [

11] of the European Commission.

In the context of novel foods, the certification and control by food safety organizations are pivotal in ensuring consumer trust and safety [

12]. Label information is equally crucial in shaping consumer perceptions of product safety. Additionally, studies emphasize the importance of food hygiene in production. For example, research in European populations highlights that foods of animal origin, primarily meat, eggs, and their derivatives, pose the greatest perceived risk and that rigorous sanitary inspections by competent authorities enhance consumer confidence [

13].

Edible insects, as a novel food category, must undergo evaluations to guarantee product safety and quality and alleviate concerns about cultural acceptance, perceived unpleasantness, and doubts regarding safe farming practices [

14,

15,

16]. Academic training and knowledge can influence consumption patterns, and young people, driven by curiosity and a lower perception of risk, may be a target audience for novel food consumption. A comprehensive study examining insect consumption, reasons for acceptance or refusal, and risk perception is essential to understand this emerging trend, with young populations serving as a valuable group for assessing the acceptance of new foods like edible insects.

In this study, a questionnaire was employed to assess the perceptions of students from various health science programs at the university and evaluate their knowledge of edible insects.

2. Material and Method

2.1. Study Design

An observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted to collect data on the consumption of insects and the potential factors influencing their acceptance as a new source of alternative protein in young population sample (universities students) from Valencia (Spain). The studies of participants were either undergraduates or graduates of: Human Nutrition and Dietetics, Pharmacy, Gastronomic Science, Food Science, Veterinary and Quality and Food Safety, from Valencia (Spain), and who voluntarily agreed to answer the questionnaire. The total number of questionnaires collected was 235, including 165 women and 70 men, comprising a range age from 19 to 35 years old. The data collection tool was a questionnaire created from a review of previous studies and using two validated questionnaires reported by Guiné et al. [

15] and Ros-Baró et al. [

18].

The final version consisted of 24 questions relating to the potential factors influencing the acceptance of insect consumption, such as cultural influences, gastronomic potential, the sustainability of food systems, economic and commercialization aspects or nutrition and health information [

15,

18]. Ten questions had a binary Yes/No response option, and fourteen were Likert scale survey questions. The Likert scale collected the options of “strongly agree”, “agree”, “disagree” and “strongly disagree” which implies to divide them in two groups: positive response (for “strongly agree” and “agree”) and negative response (“strongly disagree” and “disagree”). The questionnaire also included sociodemographic data, such as the respondents’ gender, age and studies.

2.2. Recruiting participant in the Questionnaire

The questionnaire was created on the Google Forms platform which specializes in online surveys, and was distributed during teaching sessions from 2022 to 2023 year (academic years 2021/2022 and 2022/2023). The first screen contained general information about the study. Prior to completing the questionnaire, each participant had to give consent to participate. To ensure the confidentiality of the results obtained, the questionnaires were anonymous and participants could not be identified.

The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles for research involving human beings and the processing of personal data contained in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Research in Humans of the Ethics Commission in Experimental Research of University of Valencia (cod. 1942475).

2.3. Data Analysis

Ten-item with binary scale (Yes/No) and fourteen items each scored on 5-point Likert scale were used. Yes/No responses were considered nominal and dichotomous categorical variables. Pearson’s ¬Chi-Square test, which considers a non-parametric test to measure the differences between an observed distribution and a theoretical one, allowed the relationship between these dichotomous variables to be analysed. Statistical analysis of data was carried out using the IBM SPSS Statistic version 23.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The statistical analysis of the results was performed by student’s t-test for paired samples. Differences between groups were analyzed statistically with ANOVA, followed by the Tukey HDS post hoc test for multiple comparisons. The level of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preparation of the questionnaire

Selection of questions were based on validated surveys available in bibliographic sources. In literature studies on the perception and acceptance of entomophagy have included models based on a dependent variable such as dietary behaviour and independent variables that have an effect on it, so that in the present study these aspects were taken into account. The independent variables were:

– Neophobic food, disgust with insects and risk assessment of entomophagy, are variables that have a negative influence.

– The environmental and nutritional awareness of the participants and their familiarity with entomophagy have a positive influence.

– Sociodemographic variables are also usually included since it is assumed that these also influence the acceptance of entomophagy: gender, age, and education of the participants.

Because exposure and pleasant taste experiences were recognized as essential elements for enhancing acceptability of using insects in the diet [

16], different questions were added. Instead, a greater effect is indicated by a complication of emotional elements such as disgust and neophobia, as well as familiar tastes, textures, and settings. Due to the fact that quality certification gives more confidence in the consumers, and the natural aspect of the insect determines the acceptance, label preferences were also contained in the questionnaire.

Culture and tradition were measured through what extent edible insects are or are not part of their cultural heritage. Indeed, insect consumption is closely associated with cultural values, religious festivities, local customs, taboos and traditional knowledge [

19,

20,

21]. Gastronomic potential, including innovation and gourmet kitchen, was evaluated due to certain key subjects can incentive and influence to improve the acceptability of edible insects. Environment and sustainability dimension are matters that consumers are more alert and more prone to change their diets toward more sustainable food choices [

17,

22].

Finally, the dimension of nutritional aspects, four items were included contemplating edible insects as source of: high nutritional value [

23], high amounts of proteins, fats, vitamins and minerals [

24]; and containing anti-nutrients, like oxalates and phytic acid [

25,

26,

27,

28], related to reduce the bioavailability and/or utilization of nutrients if consumed in large quantities and over a long period of time [

28].

3.2. Results of the perception questionnaire

3.2.1. Dietary habits

In literature, different studies about the acceptability of insects as food [

29,

30], as ingredient in food products [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37], as alternative of meat protein [

14,

18,

38,

39] or as insect-based feed [

40,

41,

42] have been reported. In these sense, many studies indicate that comparing the pre- and post-tasting food, there is an increase in the intention to eat products containing insect flour as well as a favourable attitude toward the behaviour in accepting those [

33]; furthermore, Erhard et al. [

37] observed that food neophobia was found to be a strong predictor of willingness to try insect foods, whereas food disgust sensitivity had no effect.

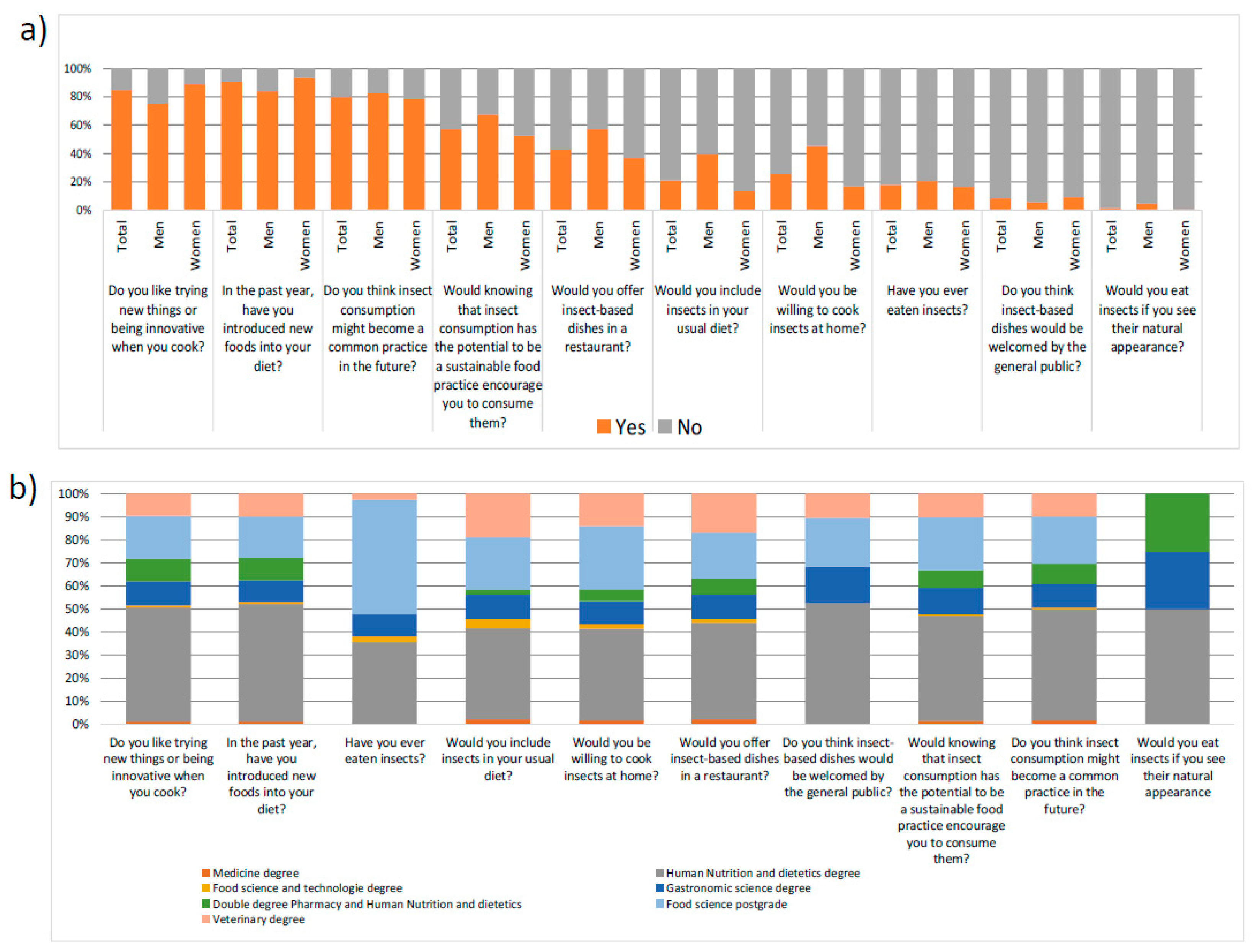

Our results of dietary habits and acceptance of insect food are reported in

Figure 1. Although only 18% of respondents had tasted insects or insect food products, a favourable attitude to try novel food and insects (>84%) accompanied by a positive response (strongly agree and agree) in having introduced new food product in the last year was obtained (90%). A positive response was also obtained for the question related to be concerned that “insect consumption will be a future common practice that will be raised up” and consequently “driven towards sustainability consumption” with 79% and 57% of responders, respectively. This positive acceptance started to decrease when asked about “offering insect meals in a restaurant” and “inclusion of insects on a diet daily basis” with 42% and 21% of responders, respectively (

Figure 1a). However, a clear increase tendency of refusing insect food products was observed in dietary habits for aspects related to: “cooking insect food”, “introduction of insects daily”, “having tried them”, “well-acceptance of all consumers or the intentions of eating them by its natural aspect” (response from 82% to 97%). To highlight that positive response in many questions and concretely with “to include insects in diet” was related to those coursing the degree of human nutrition and dietetics (40%) or postgraduate students in food science (23%) (

Figure 1b).

Another aspect to highlight in this block is gender, especially in the question about trying new foods (

Figure 1a). Women declare higher intention in trying new food compared to men (89% women vs 75% men); however, who may be willing to “include insects in their diets or cooking insects at home” or “offering insects in a restaurant”, it was higher for men (57% of men vs 37% of women and 46% of men vs 17% of women, respectively), revealing that men have high acceptance to eat insects.

3.2.2. Perception of acceptability for eating insects

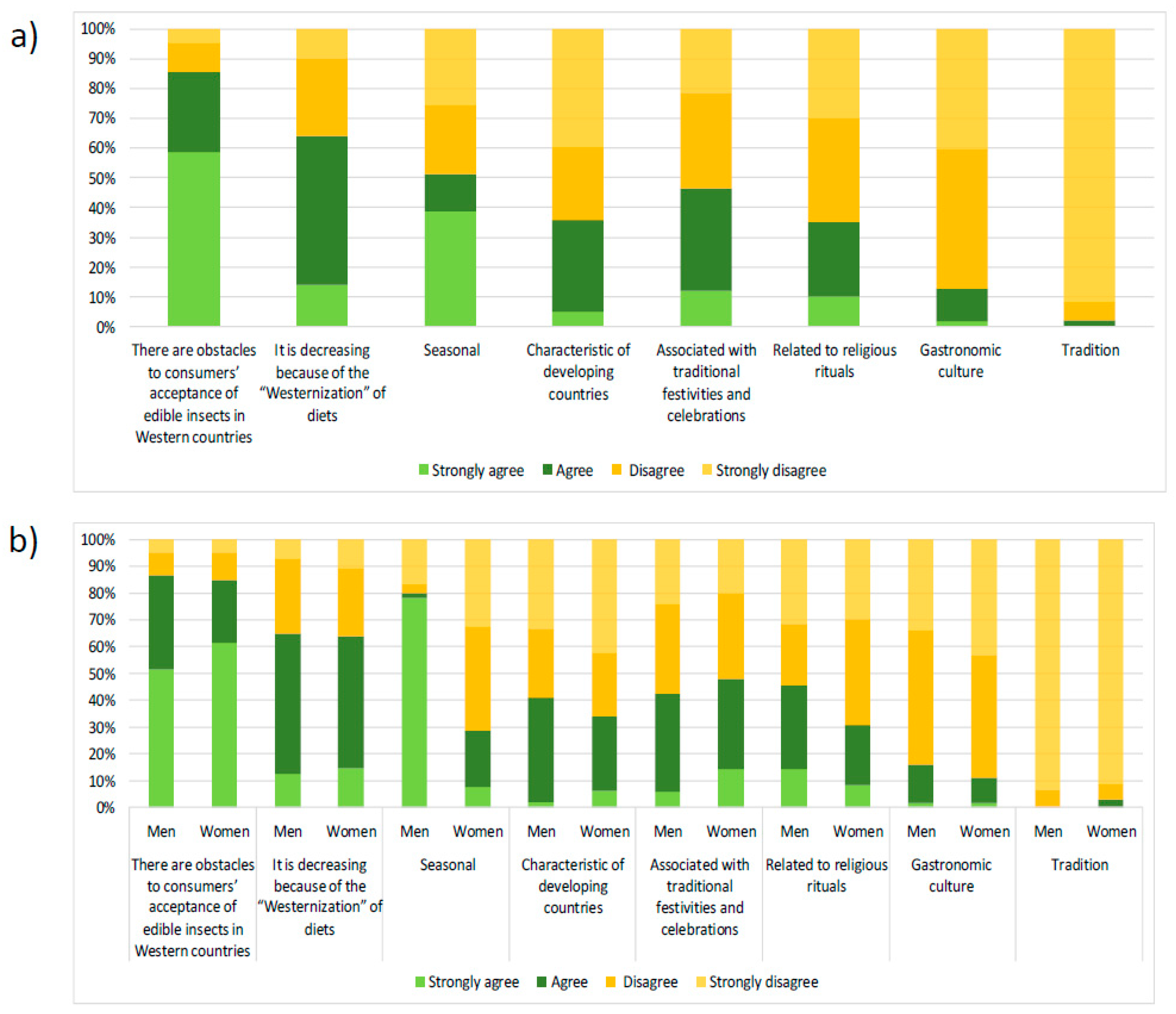

In studies about the acceptability for eating insects indicate that familiarity plays a role in reducing food-disgust. According to our results, the reasons of perception associated by Valencian university students reported in

Figure 2a about consuming insects were mainly because of a decrease “tendency in occidental diet” (64%) which implies to have a diet more open to other tendencies, followed by other factors as the fact that the consumption is “seasonal”, “common in countries worried for enhanced future food perspectives”, “associated to festivities and religious rituals” or “tradition” ranging from 8% to 47% (for positive perspective: agree and strongly agree). However, from the negative perspective (for negative perspective: considering disagree and strongly disagree), the highest negative perspective for the insect consumption was reported for being something “traditional” (98%); while, the lowest negative was for the factor of “seasonal” perception (49%). To highlight that the “tradition” (92%) and “culture” (87%) were discarded as the reasons associated of population for insects’ consumption (

Figure 2a).

A last appreciation of this block of questions was that the insect consumption has been associated with “developed countries” (36%) where there are difficulties with its consumption (86%) and has decreased by the “Westernization” of diets (58%). Regarding, gender, it was observed that men consider that the consumption of insects is “seasonal”, in fact, 79% of men responders consider this the main reason for eating insects (

Figure 2b).

3.2.3. Gastronomic perception of insects

Related to the perception of insects’ consumption and from the gastronomic point of view would be because it includes characteristic in food or because it remarks an especial occasion. The questionnaire included the evaluation of those gastronomic situation where insect consumption could be more often (Figure 3). The following factors were considered: “exotic food”, “treats/delicacies food”, “edible in gourmet restaurants”, “present in culinary events and gastronomic shows”, “recommended by some recognized chefs”, “chefs contribute to the popularization of insects into gastronomy”, or “culinary education favours overall liking for innovative insect based products” (Figure 3).

Results revealed that out of all factors, a total of 82% consider that the gastronomic perception of insects as edible is associated to be “exotic food” and 78% associated to “available in gourmet restaurants”, and it has been the chefs’ task who have contributed to the popularization of its presence in culinary events and gastronomic shows (72%) (Figure 3a). On the opposite, respondents revealed that the gastronomic perception is associated at all to the fact that can be considered “treat food” (candies) either the “culinary nutritional education” and the fact of being “available in culinary events”, contribute to its popularization, the values observed ranging from 52% to 71%. That two factors about chef were perceived as less positive motivation to consume edible insects (72%), obtaining equal frequency. However, for women the impact of “insects consume being recommended by some recognized chefs” (72%) were higher than for men (62%) (Figure 3b).

3.2.4. Knowledge of insect safety quality and the effect of insect consumption on health.

In the acceptance or rejection of insects’ consumption, it becomes relevant to know in what way the respondents have one degree or another (education) and the level of knowledge and awareness for sustainability issues, as it can contribute to the perception of insects’ consumption. Although literature collects different methodologies related to this topic, such as, the Food Neophobia Scale [

43] (to highlight that it is one of the most used); it does not apply specifically to edible insects and does not cover the range of domains that were included in our questionnaire. The dimension considered was Health Knowledge which it is essentially related to the risks associated with the consumption of insects and the knowledge of safe quality. Consumers tend to decrease trustiness for those foods that are not familiar with and consider them to pose a higher level of risk than other foods, especially with higher risks involved.

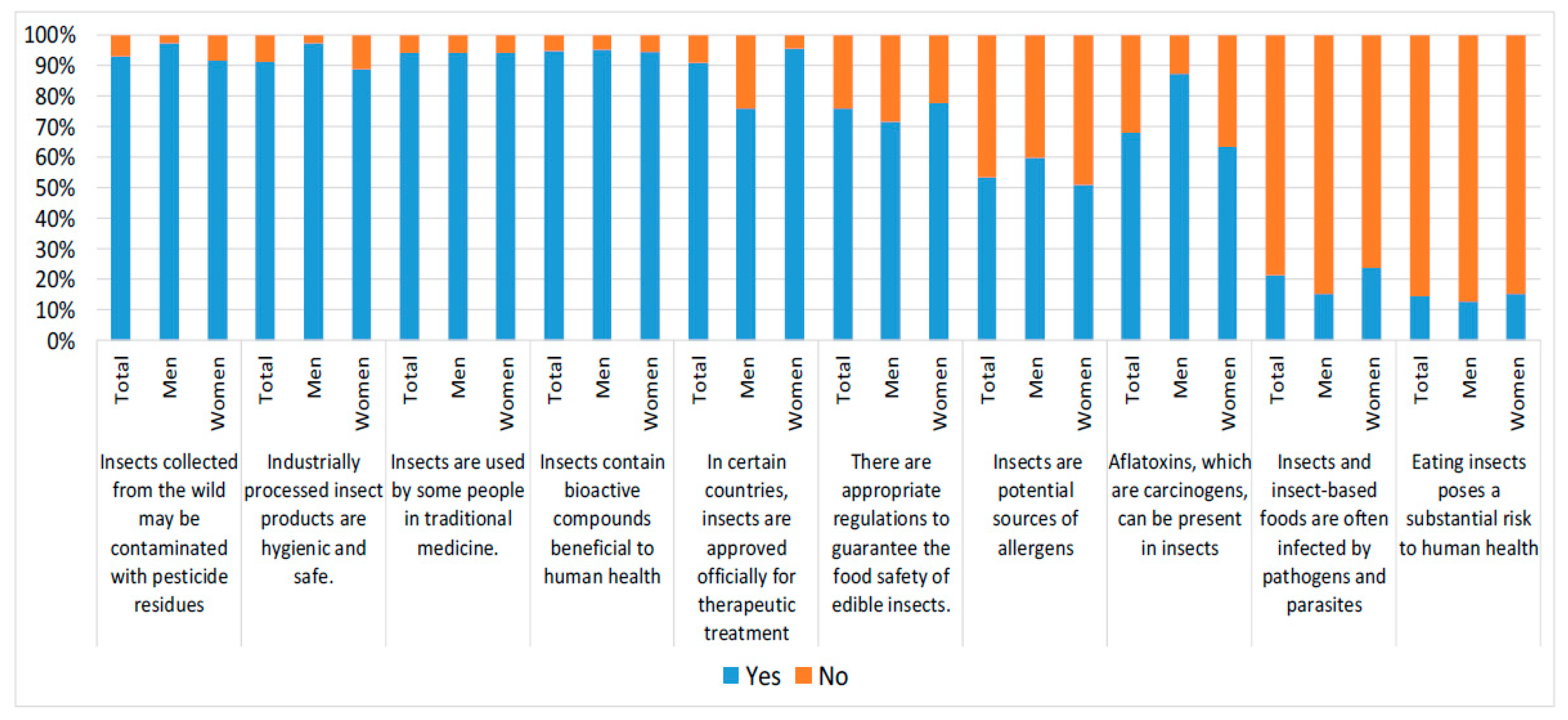

Although the perception of risks is usually high in insect consumption, in our study the university students have declared that in aspects related to health it is highly possible that “insects collected from forests may be contaminated with pesticide residues” (93%) to find accordingly that then “industrially processed insect products are hygienic and safe” in a 91% of respondents (

Figure 4). Among that, it was revealed that respondents understand that “insects are used by some people in traditional medicine” (94%). In the same tendency of concern and perception of benefits and healthy aspects that can be in insect´s consumption, there was a clear positive response in the fact that “insects contain bioactive compounds beneficial for human health” (95%) as well as its use in some culture for therapeutic treatment are officially approved (91%) or that by “eating insects does not pose a substantial risk to human health” (86%) and that is not infected by pathogens or parasites (79%) (

Figure 4).

From this section, it is also important to remark that there is uncertainty and unknown concepts related to the health benefits for example the presence of contaminants such as aflatoxins in insects (81%) and consider the source of insects as potential allergens (67%) (

Figure 4).

To summarize, the consumption of insects is perceived as safe, including all good practices followed in their production and transformation, just as has happened with other types of food. However, if the insects are collected from wild/forests the responders indicate that they may be contaminated with pesticide residues, contributing to the risk perception of insect consumption (

Figure 4).

Regarding regulations for insects’ consumption, the students ignored if there is a European legislation and the item related with this dimension was for 33% (76 students) by indicating that “there are appropriate regulations to guarantee the food safety of edible insects”; however, there were 56% (131 students) that ignored if there are regulations to guarantee the food safety of edible insects. This brought us to know that students are not informed about the recent regulation established by European Commission [

8,

9,

10,

11].

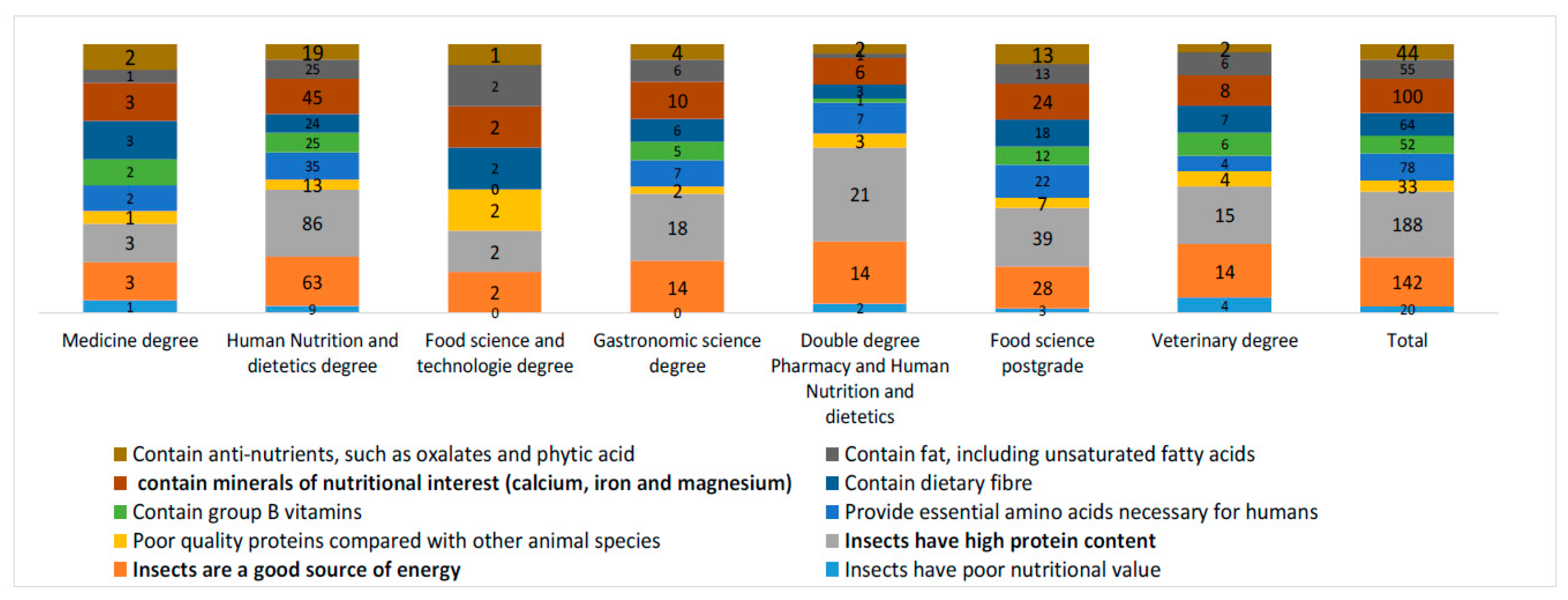

3.2.5. Knowledge of the nutritional and health contribution of insects

The designed questionnaire contemplated the dimension of nutritional aspects by analysing them in two directions: i) through the nutritional contribution, and ii) through the education profile of the responders. It was confirmed that the nutritional quality of the consumption of insects was the most known aspect. Majority of the students indicated that the insects have high nutritional value because they provide high protein content (91%) and are a good source of energy (75%). When it was asked about specific knowledge of providing specific nutritional components, the following order was reached (from strongly agreed to strongly disagree): providing nutritional minerals, essential amino acids, dietetic fibre, fatty acids, vitamin B group, phitic acid and oxalates, poor quality of protein content and poor nutritional content (Figure 5) ranging from 26% to 76%.

Regarding the educational profile or the studied degree, it was observed that for respondents in human nutrition and dietetic degree were convinced that insects are a good source of energy and have high protein content, followed by double degree pharmacy and human nutrition and dietetics and food science postgraduate students which were considered both groups as the highest knowledge related to food safety (

Figure 6). Nevertheless, there was also a general perception collected in respondents that although their degree had less linked-up with food perception, both factors of good protein and energy source were also the ones with the highest punctuation.

3.2.6. Influence of marketing and labeling preferences on purchase and consumption

Literature reveals that there are studies where the effect of the visual appearance of the real insect on the product packaging, indicating that it can trigger a disgust-based food rejection [

44] have been evaluated; while others, report an increased willingness to eat products where the insect ingredient are less visible compared to products that contain unprocessed insect ingredients [

45,

46]. It has been concluded that removing the image of the insect from the product packaging can have a beneficial effect on perceived disgust, removing any references to insects can be perceived as deceptive strategy and therefore lead to negative consumer reactions [

47]. However, our results reported in

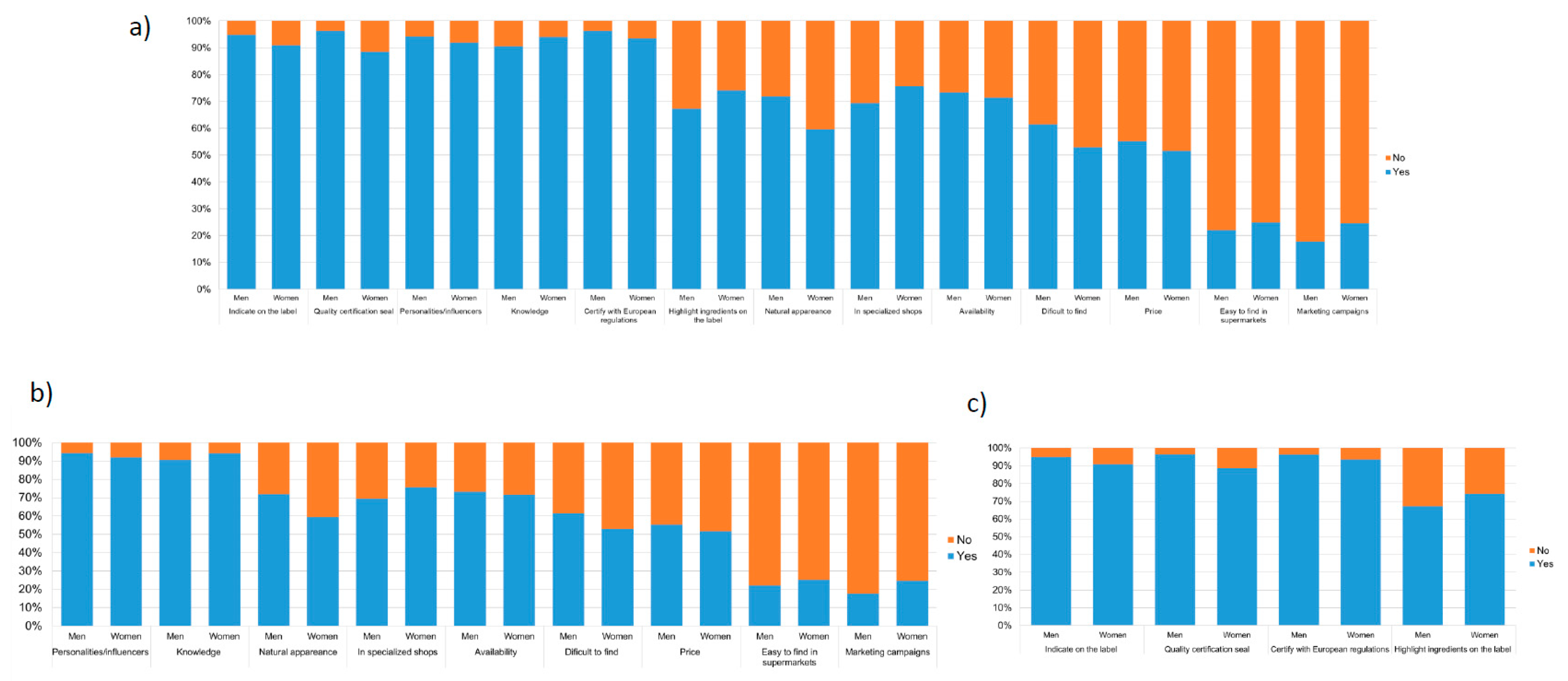

Figure 7, suggest that our responders, regarding the preferences of information appearing in the label it is highly preferred to indicated the presence of insect´s derivative as ingredient (92%), followed by presence of quality certification seal (91%), prefer the natural appearance in the product package (63%), as well as correctly labelled indicating completely the information about insect´s content (92%). Regarding the aspect of certification, the students ‘perception was safe if label indicates information about the certify that they comply with European regulations with the identification mark and health mark (94%), and perceives greater product safety if there is a quality certification seal (91%).

Related with food packaging and food labelling, marketing enters as an important factor. In fact, marketing has implication for communication of product benefits and qualities. However, marketers have to be careful when attempting to promote product healthiness and sustain- ability, especially through product packaging. Pozharliev et al. [

44] show that removing the focus on health- and sustainability- related benefits from the product packaging improves consumers’ implicit, self-reported, intentional and behavioural responses to insect-based food products for first-time users. Then, in our questionnaire it was included to evaluate the perception of influence of marketing campaigns to consumption. Results revealed that 134 students (77%) make crucial the marketing for insects´ consumption; however, many of them has declared that “The level of knowledge influences the willingness to purchase insect food” (93%).

4. Conclusions

The study on the acceptance of introducing insects as new foods into the diets of Spanish university students was here assessed based on a perception questionnaire. The results showed that, while a small proportion of participants had tried insects or insect-based food products and a few were willing to include them in their regular diet, there was a positive attitude toward consuming them in the future, especially due to sustainability. The main reason for the low consumption of insects was the traditional and cultural aspects typical of Western countries, making them seem exotic in gastronomy. Regarding nutrition and food safety, most participants believed in the nutritional and health benefits of insects and trusted the hygiene standards of the food industry over direct field collection. When it comes to consumer information, the study found that product acceptance could be improved by using certifications from food control and safety organizations to ensure product quality and safety. While gender differences are often observed in studies related to food risk perception, this study did not find substantial differences between males and females, except for minor variations in dietary habits and some considerations about the seasonality and nutritional components of entomophagy.

The availability of edible insects to consumers underscores the complexities and intricacies of our relationship with food, culture, nature, and sustainability. Although struggling with these questions is happening, the acceptance of edible insects reflects a shift toward a more environmentally conscious and ethically responsible approach to food, challenging long-standing norms and encouraging us to think more deeply about our place in the natural world.

Acknowledgments

this work has been supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation project PID2020-115871RB-100 and the Conselleria d’Educació, Universitats i Ocupació from Generalitat Valenciana project CIAICO2022/199.

References

- Reglamento (CE) N° 258/97, de 27 de Enero de 1997, sobre nuevos alimentos y nuevos ingredientes alimentarios.

- Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council, of November 25, 2015, regarding novel foods.

- Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/2470 of the Commission of December 20, 2017 establishing the union list of novel foods, in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council, related to new foods.

- EFSA, Novel Food Catalogue, available in: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/fip/novel_food_catalogue/ (consulted November 5th, 2023).

- Ververis, E.; Ackerl, R.; Azzollini, D.; Colombo, P.A.; de Sesmaisons, A.; Dumas, C.; Fernandez-Dumont, A.; Ferreira da Costa, L.; Germini, A.; Goumperis, T. “Novel Foods in the European Union: Scientific Requirements and Challenges of the Risk Assessment Process by the European Food Safety Authority.” Food Research International 2020. 137: 109515. [CrossRef]

- EFSA Scientific Committee. 2015. “Risk Profile Related to Production and Consumption of Insects as Food and Feed.” EFSA Journal 13 (10): 4257. [CrossRef]

- Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición (AESAN), Situación de los insectos en alimentación humana (26 April 2023). Available in: https://www.aesan.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/seguridad_alimentaria/gestion_riesgos/insectos_alimentacion.pdf (Consulted 29th September 2023).

- Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/882 of the Commission of June 1, 2021 authorizing the marketing of dried Tenebrio molitor larvae as a novel food in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/2470 is amended.

- Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/1975 of the Commission of November 12, 2021 authorizing the marketing of frozen, dried and powdered forms of Locusta migratoria as a novel food in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council and modifies Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/2470.

- Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/169 of the Commission of February 8, 2022 authorizing the marketing of frozen, dried and powdered forms of the mealworm (Tenebrio molitor larva) as a novel food under to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council and modifies the Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/2470 of the Commission.

- Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/188 of the Commission of February 10, 2022 authorizing the marketing of frozen, dried and powdered forms of Acheta domesticus as a novel food in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council and amending Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/2470 (Text relevant for EEA purposes).

- Cantalapiedra, F.; Juan, C.; Ana Juan-García, A. “Facing Food Risk Perception: Influences of Confinement by SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Young Population.” Foods 2022, 11 (5): 662.

- Djekic, I.; Nikolic, A.; Mujcinovic, A.; Blazic, M.; Herljevic, D.; Goel, G.; Trafiałek, J.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Guiné, R.; Gonçalves, J.C. “How do Consumers Perceive Food Safety Risks?–Results from a Multi-Country Survey.” Food Control 2022, 142: 109216. [CrossRef]

- Boehm, E.; Borzekowski, D.; Ververis, E.; Lohmann, M.; Böl, G-F. “Communicating Food Risk-Benefit Assessments: Edible Insects as Red Meat Replacers.” Frontiers in Nutrition 2021 8: 749696. [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Bartkiene, E.; Florença, S.G.; Djekić, I.; Bizjak, M.Č.; Tarcea, M.; Leal, M.; Ferreira, V.; Rumbak, I.; Orfanos, P.; et al. Environmental Issues as Drivers for Food Choice: Study from a Multinational Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendin, M.E.; Nyberg, M.E. Factors Influencing Consumer Perception and Acceptability of Insect-Based Foods. Current Opinion in Food Science, 2021, 40, 67-71.

- Guiné, P.F.; Sofia, G.; Florença.; Cristina, A.; Costa, M.R.; Correia, MF.; João Duarte, AP.; Cardoso, SC.; Ofélia, A. Development of a Questionnaire to Assess Knowledge and Perceptions about Edible Insects. Insects, 2021, 13, 1, 47.

- Ros-Baró, M.; Sánchez-Socarrás, V.; Santos-Pagès, M.; Bach-Faig, A.; Aguilar-Martínez, A. Consumers’ Acceptability and Perception of Edible Insects as an Emerging Protein Source. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022, 19, 23, 15756. [CrossRef]

- Megu, K.; Jharna, C.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B. An Ethnographic Account of the Role of Edible Insects in the Adi Tribe of Arunachal Pradesh, North-East India. Edible Insects in Sustainable Food Systems, 2018, 35-54.

- Séré, A.; Adjima, B.; Judicaël, T.O.; Mamadou, T.; Hassane, S.; Anne Mette, L.; Amadé, O.; Olivier, G.; Imaël Henri, N.B. Traditional Knowledge regarding Edible Insects in Burkina Faso. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 2018, 14, 1-11.

- Ghosh, S.; Jung, C.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B. What Governs Selection and Acceptance of Edible Insect Species? Edible Insects in Sustainable Food Systems, 2018, 331-351. [CrossRef]

- Matek Sarić, M.; Krešimir Jakšić, J.C.; Guiné, R. Environmental and Political Determinants of Food Choices: A Preliminary Study in a Croatian Sample. Environments, 2020, 7, 11, 103. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Lucas, A. J; Menegon de Oliveira, L.M.R.; Prentice, C. Edible Insects: An Alternative of Nutritional, Functional and Bioactive Compounds. Food Chemistry, 2020, 311, 126022. [CrossRef]

- Agbidye, F. S.; Ofuya, T. I.; Akindele, S. O. Some Edible Insect Species Consumed by the People of Benue State, Nigeria. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 2009, 8, 7, 946-950. [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, J.; Ghosh, S.; Megu, K.; Jung, C.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B. Nutritional and Anti-Nutritional Composition of Oecophylla Smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and Odontotermes Sp. (Isoptera: Termitidae): Two Preferred Edible Insects of Arunachal Pradesh, India”. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology, 2016, 19, 3, 711-720. [CrossRef]

- Murefu, T.R.; Macheka, L.; Musundire, R.; Manditsera, F.A. Safety of Wild Harvested and Reared Edible Insects: A Review. Food Control, 2019, 101, 209-224. [CrossRef]

- Ojha, S.; Bekhit, A.E.; Grune, T.; Schlüter, O.K. Bioavailability of Nutrients from Edible Insects. Current Opinion in Food Science, 2021, 41, 240-248. [CrossRef]

- Kunatsa, Y.; Chidewe, C.; Zvidzai, C.J. Phytochemical and Anti-Nutrient Composite from Selected Marginalized Zimbabwean Edible Insects and Vegetables. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 2020, 2, 100027. [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, R.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Consumer Perceptions of Insect Consumption: A Review of Western Research since 2015. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 2021, 56,10, 4942-4958. [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, C.; Materia, V.C. Insects Or Not Insects? Dilemmas Or Attraction for Young Generations: A Case in Italy”. International Journal on Food System Dynamics, 2018, 9, 3, 226–239. [Google Scholar]

- Piha, S.; Pohjanheimo, T.; Lähteenmäki-Uutela, A.; Zuzana Křečková, Z.; Otterbring, T. The Effects of Consumer Knowledge on the Willingness to Buy Insect Food: An Exploratory Cross-Regional Study in Northern and Central Europe. Food Quality and Preference, 2018, 70, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.; Norwood, B.F.; Hoback, W.W.; Riggs, A. A Survey of Willingness to Consume Insects and a Measure of College Student Perceptions of Insect Consumption using Q Methodology. Future Foods, 2021, 4, 100046. [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, D.; Sogari.; Veneziani G.M, Simoni, E.; Mora, C. 2017. Eating Novel Foods: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict the Consumption of an Insect-Based Product. Food Quality and Preference, 2017, 59, 27-34. [CrossRef]

- Specht, K.; Zoll, F.; Schümann, H.; Bela, J.; Kachel, J.; Robischon, M. How Will we Eat and Produce in the Cities of the Future? from Edible Insects to Vertical farming—A Study on the Perception and Acceptability of New Approaches. Sustainability, 2019, 11,16, 4315. [CrossRef]

- Claudia, D.; Schouteten, J.J.; Dewettinck, K.; Gellynck, X.; Tzompa-Sosa, D.A. Consumers’ Perception of Bakery Products with Insect Fat as Partial Butter Replacement. Food Quality and Preference, 2020, 79, 103755. [CrossRef]

- Dion-Poulin, A.; Mylène Turcotte, S.L.; Perreault, V.; Provencher, A.D.; Turgeon, S.L. ”Acceptability of Insect Ingredients by Innovative Student Chefs: An Exploratory Study”. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 2021, 24, 100362.

- Erhard, A.L.; Silva, M.A.; Damsbo-Svendsen, M.; Sørensen, H.; Bom Frøst, M. Acceptance of Insect Foods among Danish Children: Effects of Information Provision, Food Neophobia, Disgust Sensitivity, and Species on Willingness to Try. Food Quality and Preference, 2023, 104, 104713. [CrossRef]

- Mancini, S.; Sogari, G.; Espinosa Diaz, S.; Menozzi, Paci, G.; Roberta Moruzzo, R. Exploring the Future of Edible Insects in Europe. Foods, 2022, 11, 3, 455. [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, N.; Nervo, C.; Torri, L. Consumers’ Attitudes Towards Sustainable Alternative Protein Sources: Comparing Seaweed, Insects and Jellyfish in Italy. Food Quality and Preference, 2023, 104, 104735.

- Szendrő, K.; Tóth, K.; Nagy, M.Z. Opinions on Insect Consumption in Hungary. Foods, 2020, 9, 12, 1829. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.C.; Sposito, A.T.; Pinto, A.; Varela, P.; Cunha, L.M. Insects as Food and Feed in Portugal and Norway–cross-Cultural Comparison of Determinants of Acceptance. Food Quality and Preference, 2022, 102, 104650. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Osei-Owusu, J.B.; Yunusa, M.T.; Rahayu, M.T.; Fernando, I.; Shah, M.A.; Centoducati, G. Prospects of Edible Insects as Sustainable Protein for Food and Feed–a Review. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 2023, 1, aop, 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a Scale to Measure the Trait of Food Neophobia in Humans. Appetite, 1992, 19, 2, 105-120. [CrossRef]

- Pozharliev, R.; De Angelis, M.; Rossi, D.; Bagozzi, R.; Amatulli, C. I might Try it: Marketing Actions to Reduce Consumer Disgust Toward Insect-Based Food. Journal of Retailing, 2023, 99, 1,149-167. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Shi, J.; Alice Giusto, A.; Siegrist, M. The Psychology of Eating Insects: A Cross-Cultural Comparison between Germany and China. Food Quality and Preference, 2015, 44, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.S.G.; Verbaan, Y.T.; Stieger, M. How Will Better Products Improve the Sensory-Liking and Willingness to Buy Insect-Based Foods? Food Research International, 2017, 92, 95-105. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M. Consumers’ Responses to Price Presentation Formats in Rebate Advertisements. Journal of Retailing, 2006, 82, 4, 309-317. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).