Submitted:

08 November 2023

Posted:

08 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Monsoon Onset

- Drop in temperature

- Rise in dew point

- Wind shift to southerly

- Increase in wind speed

- Rise in sea-level pressure

- Lower visibility (due to haze and blowing dust)

- Increasing low to mid-level cloud cover

El Niño Southern Oscillation

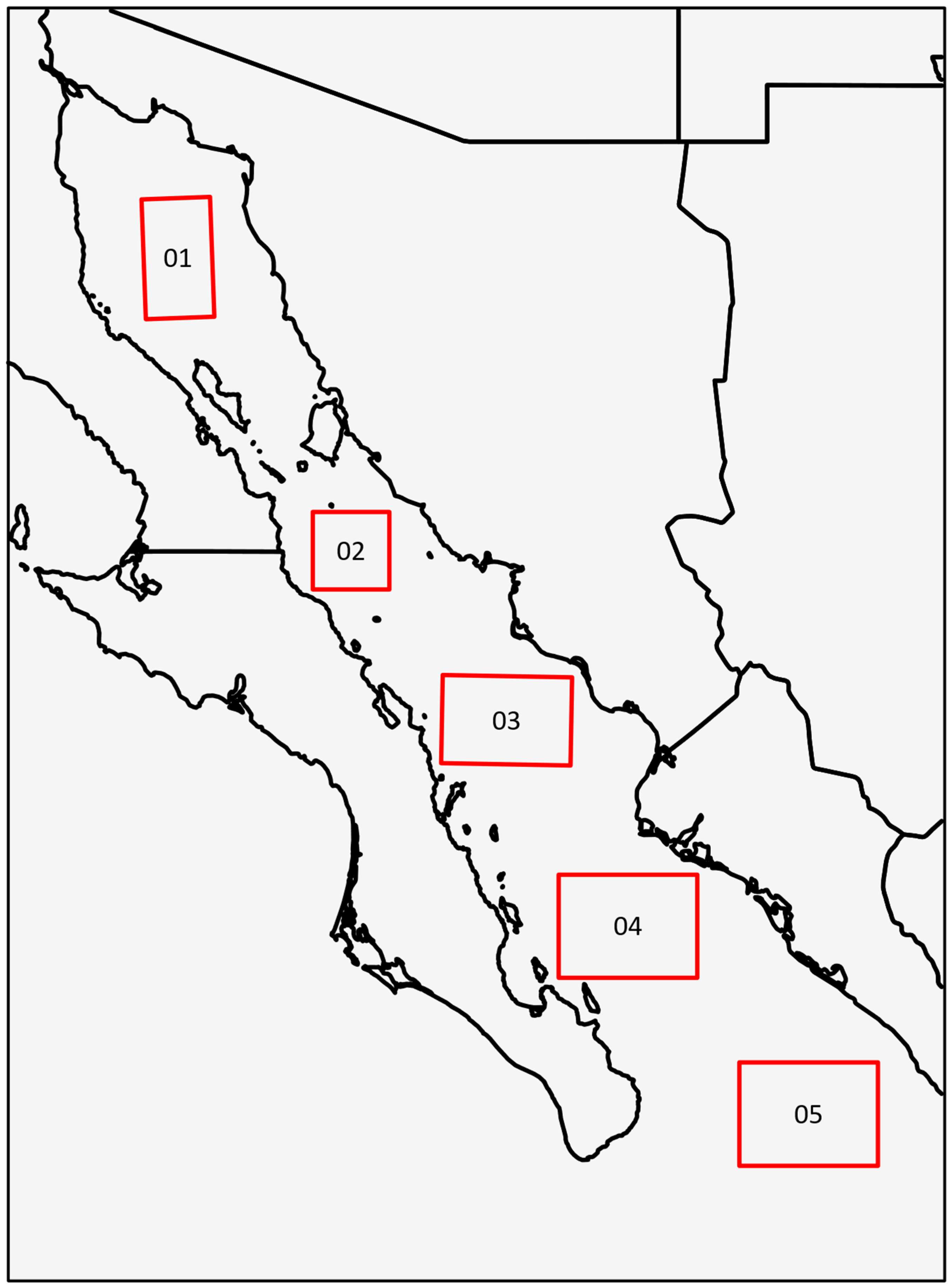

Gulf of California (GoC) Sea Surface Temperatures (SST)

Results

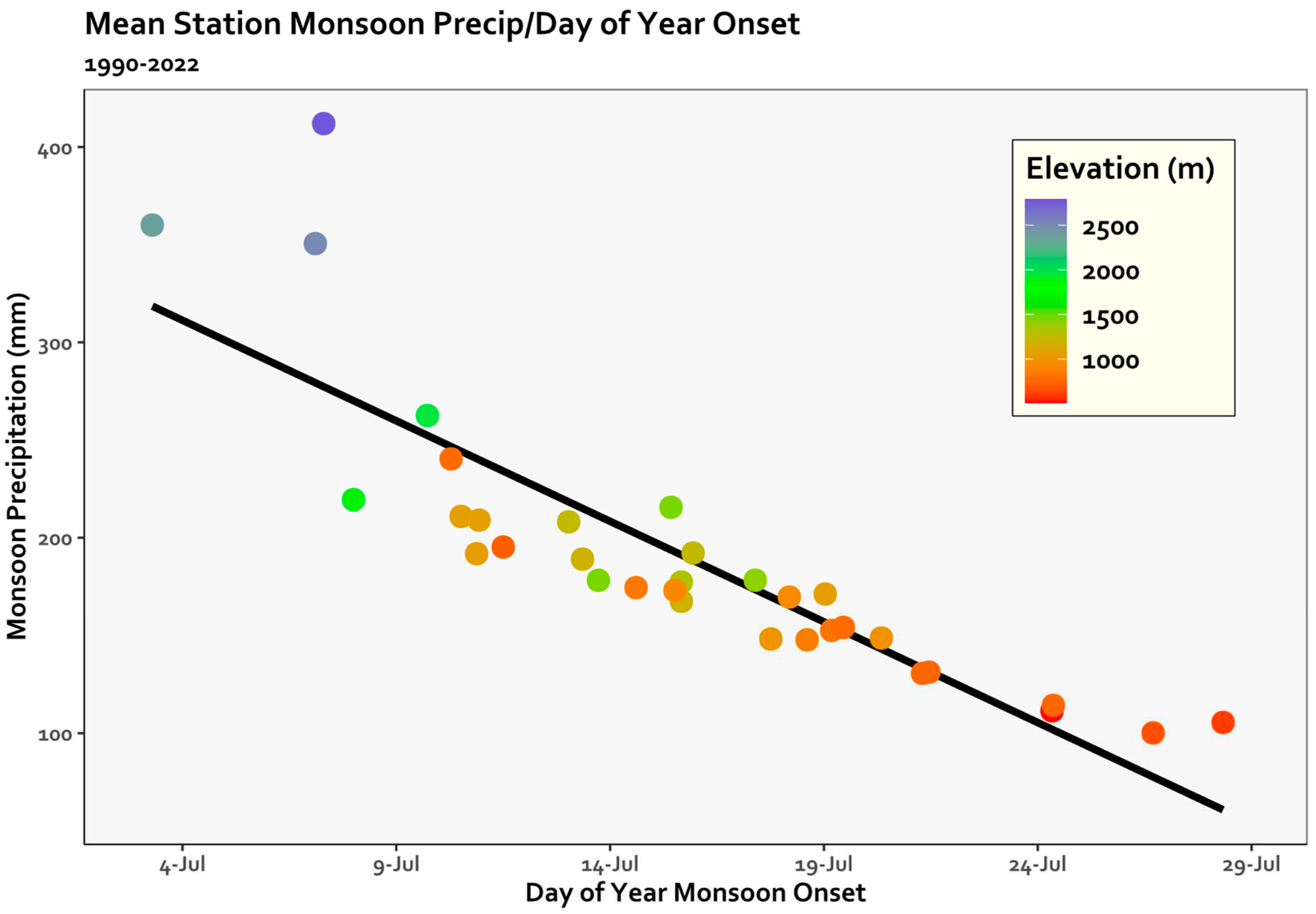

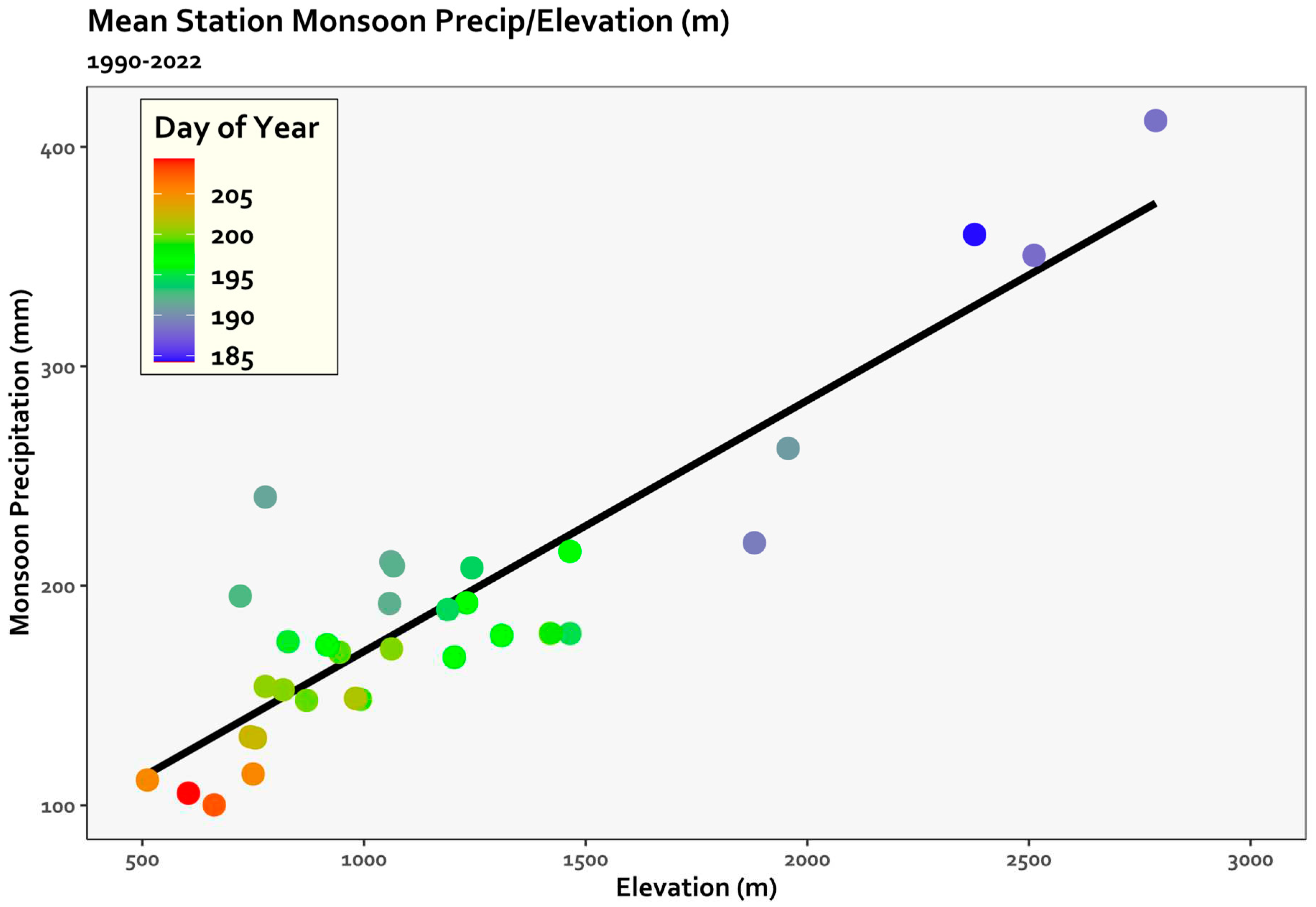

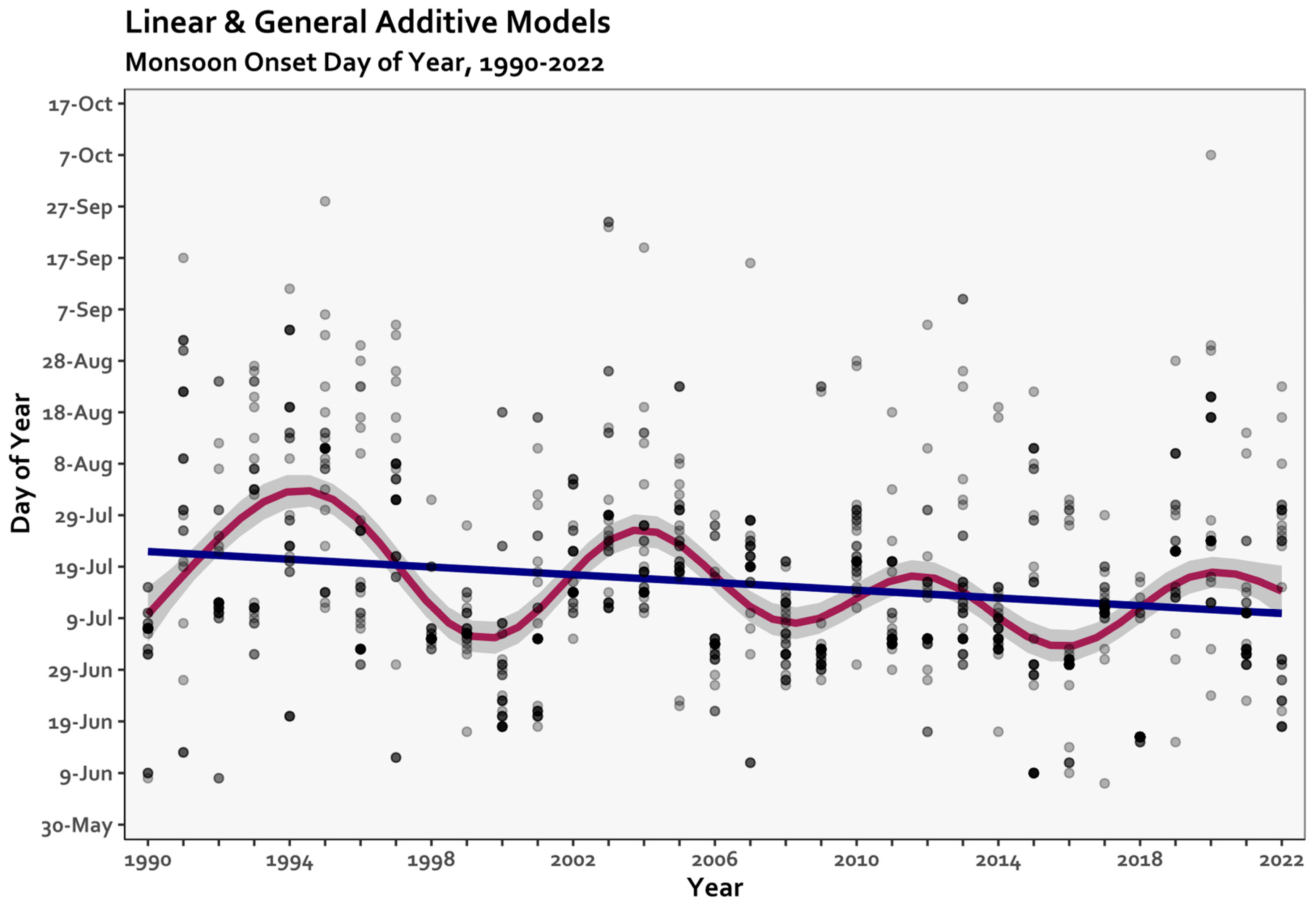

Monsoon Onset Timing

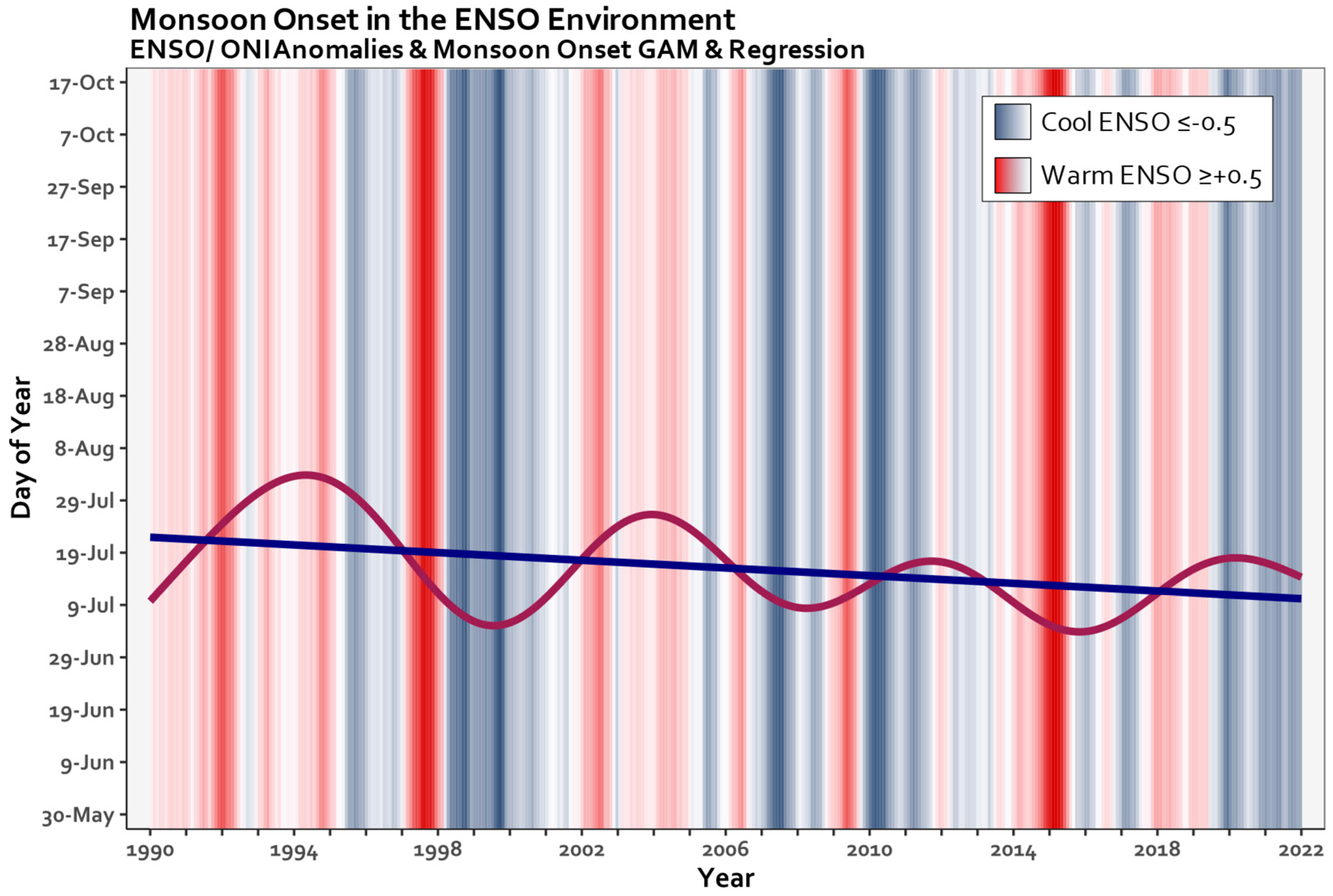

El Niño Southern Oscillation

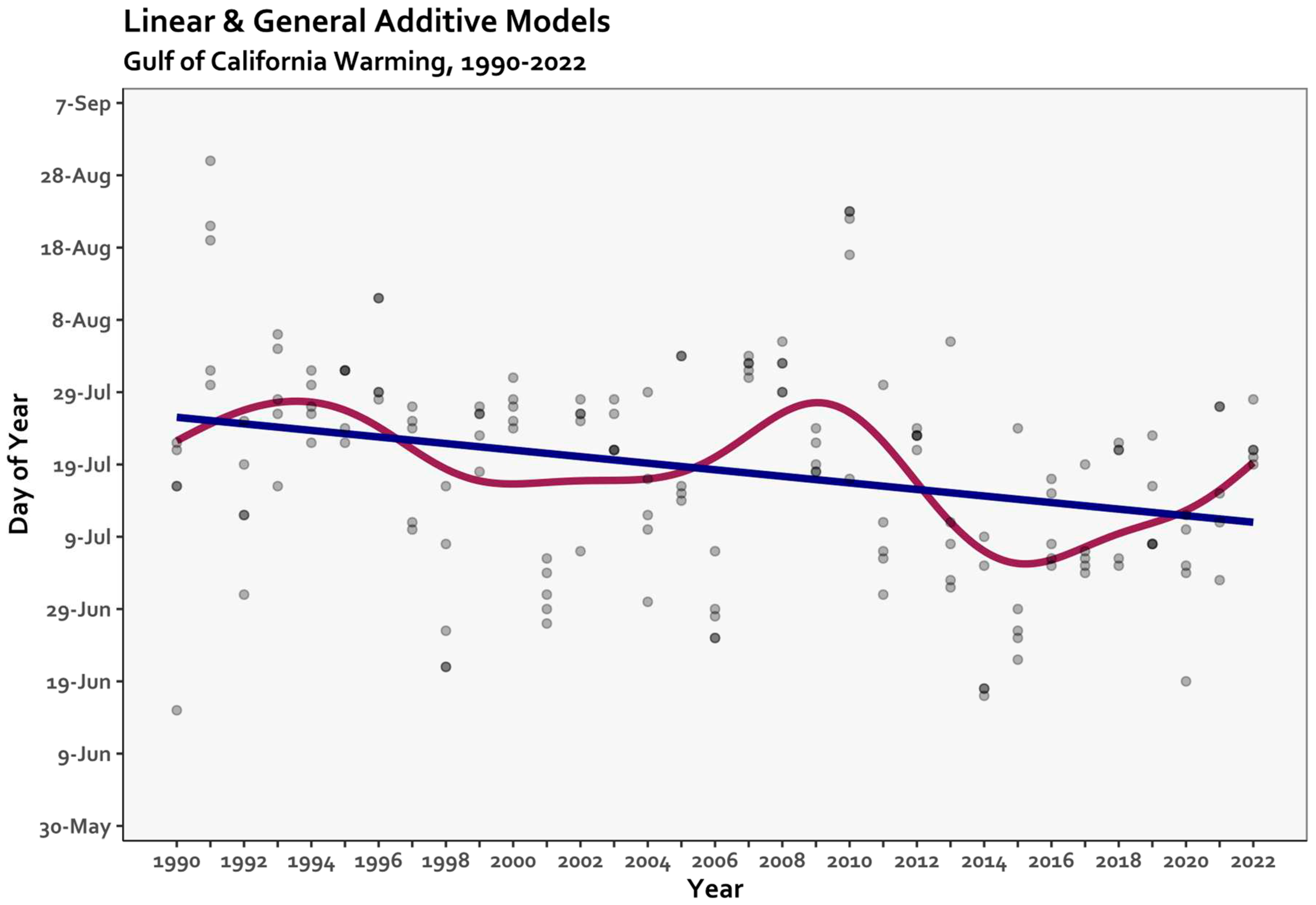

Gulf of California SST Warming

Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowers J, Dimmitt M 1994 Flowering phenology of six woody plants in the northern Sonoran Desert Bulletin Torrey Bot. Club 121 215-229. [CrossRef]

- Brenner I 1973 A surge of maritime tropical air-Gulf of California to the Southwestern United States 1973 NOAA Tech. Memo. NWS WR88 US Dept. Commerce, Natl. Weather Serv.

- Carleton A 1985 Synoptic And Satellite Aspects Of The Southwestern U.S. Summer ‘Monsoon’ J. Climatol. 5 389-402.

- Huang B, Liu C, Banzon VF, Freeman, E, Graham G, Hankins B, Smith TM, Zhang H-M 2020 NOAA 0.25-degree Daily Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST), Version 2.1. NOAA Natl. Ctrs. Environ. Info.

- Di Lorenzo E, Xu T, Zhao Y, Newman M, Capotondi A, Stevenson S, Amaya DJ, Anderson BT, Ding R, Furtado JC, Joh Y, Liguori G, Lou J, Miller AJ, Navarra G, Schneider N, Vimont DJ, Wu S, Zhang H, 2023 Modes and mechanisms of Pacific decadal-scale variability Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15 249-275. [CrossRef]

- Douglas M, Maddox R, Howard K 1993 The Mexican monsoon J Clim. 6 1665-1677. [CrossRef]

- Erfani E, Mitchell D 2014 A partial mechanistic understanding of the North American monsoon J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 119 096–13. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Hernandez M, Turrent C, Mayor Y, Tereschenko I 2021 Using observational and reanalysis data to explore the southern Gulf of California boundary layer during the North American Monsoon onset J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Higgins R, Chen Y, Douglas A 1999 Interannual variability of the North American warm season precipitation regime J Clim 12 653–680. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell D, Ivanova D, Rabin R, Brown T, Redmond K 2002 Gulf of California sea surface temperatures and the North American monsoon: Mechanistic implications from observations J. Clim. 15 2261–2281. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell D, Ivanova D, Redmond K 2003 Onset of the 2002 North American Monsoon: Relation to Gulf of California sea surface temperatures 12th Conf. Interactions of the Sea Atmos. 83th AMS Ann. Meeting, Long Beach, Calif., 9–14 Feb.

- Williams A, Cook B, Smerdon J 2022 Rapid intensification of the emerging southwestern North American megadrought in 2020–2021 Nature Clim. Change 12 232-234. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Gao X, Shuttleworth J, Sorooshian S, Small E 2004 Model climatology of the North American Monsoon onset period during 1980-2001 J. Clim. 17 3892–3906. [CrossRef]

- Zeng X, Lu E 2004 Globally unified monsoon onset and retreat indexes. J. Clim. 17 2241-2248. [CrossRef]

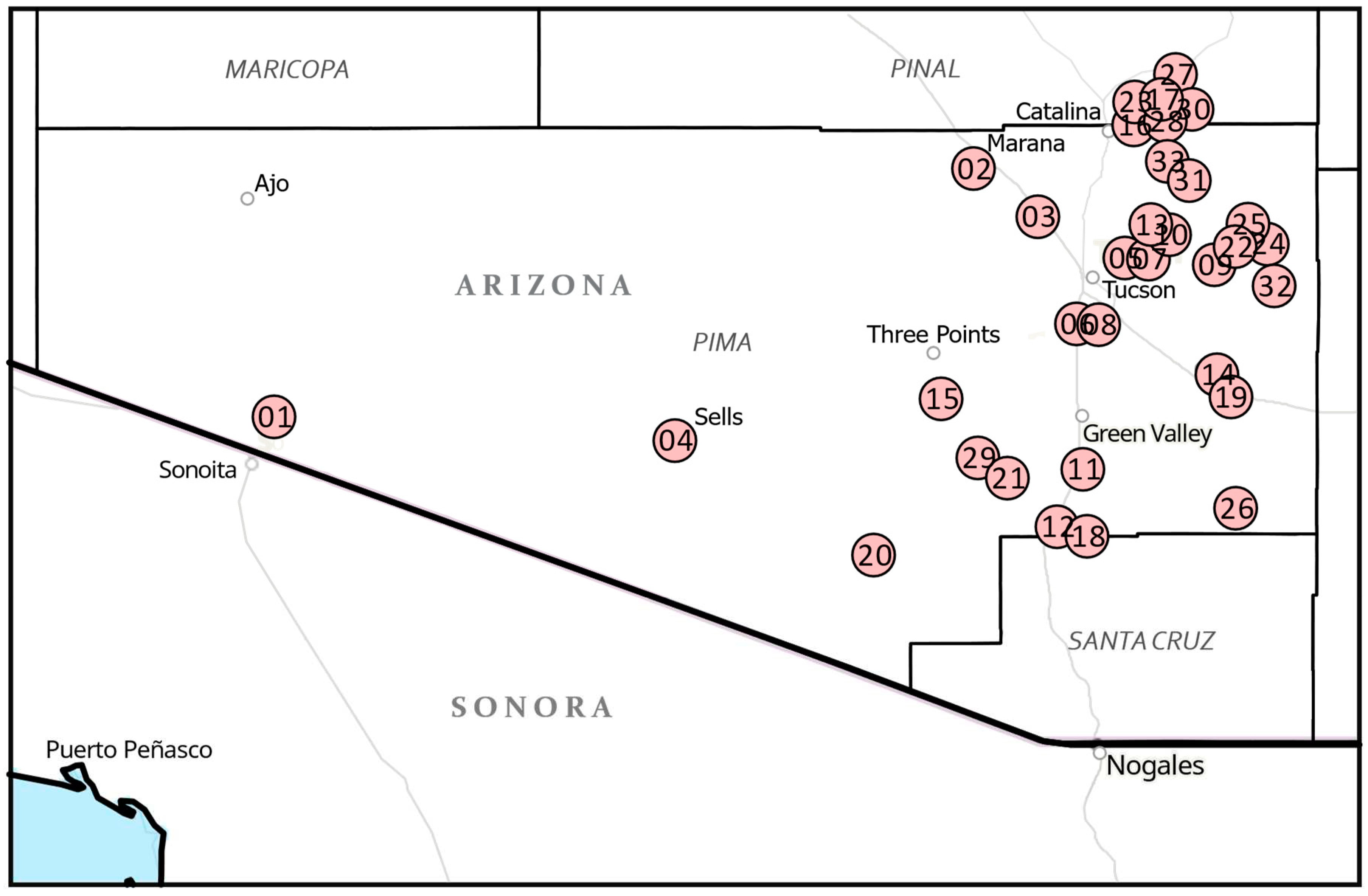

| Network | Station ID | Station Name | Period of Record Used | Elev. (m) | Latitude | Longitude | |

| 1 | US Park Service3 | USC00026132 | Organ Pipe Cactus NM | 1990-2001, 2003-2022 | 512 | 31.9555 | -112.8002 |

| 2 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 6110 | Avra Valley Air Park/Santa Cruz R | 1990-2000, 2002-2022 | 604 | 32.42902 | -111.2251 |

| 3 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 6020 | Santa Cruz R/Ina Rd | 1990-2000, 2002-2022 | 662 | 32.33725 | -111.0801 |

| 4 | RAWS4 | 021209 | Sells | 2005-2006, 2008-2009, 2011-2022 | 721 | 31.91 | -111.8975 |

| 5 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 2370 | Alamo Wash/Glenn St | 1990-2008, 2010-2021 | 744 | 32.25871 | -110.8841 |

| 6 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 6040 | Santa Cruz R/Valencia Rd | 1990-1996, 1998-2021 | 750 | 32.13306 | -110.9931 |

| 7 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 2120 | Tanque Verde Sabino Bridge | 1990-2000, 2001-2010, 2011-2022 | 755 | 32.26529 | -110.8415 |

| 8 | US Weather Service2 | USW00023160 | Tucson Int'l Airport | 1990-2022 | 778 | 32.13153 | -110.9564 |

| 9 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 2090 | Tanque Verde Guest Ranch | 1990-2008, 2010-2021 | 829 | 32.2458 | -110.6828 |

| 10 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 2160 | Sabino Dam | 1990-2022 | 847 | 32.31464 | -110.8109 |

| 11 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 6050 | Santa Cruz R/Continental Rd | 1990-2021 | 871 | 31.85512 | -110.9788 |

| 12 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 6060 | Santa Cruz R/Canoa Ranch | 1990-2022 | 917 | 31.7451 | -111.037 |

| 13 | RAWS4 | 021202 | Saguaro | 2002-2022 | 945 | 32.31667 | -110.8133 |

| 14 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 4250 | Pantano Vail | 1990, 1992-2019, 2022 | 981 | 32.03595 | -110.6768 |

| 15 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 6410 | Diamond Bell Ranch | 1990-1999, 2001-2022 | 992 | 31.98991 | -111.298 |

| 16 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1040 | Dodge Tank | 1990-2020 | 1006 | 32.51192 | -110.8642 |

| 17 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1070 | Catalina State Park | 1991-2021 | 1009 | 32.52609 | -110.7948 |

| 18 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 6350 | Elephant Head | 1990-2022 | 1058 | 31.72684 | -110.9694 |

| 19 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 4310 | Davidson Canyon | 1990-2022 | 1061 | 31.99358 | -110.6452 |

| 20 | RAWS4 | 021206 | Sasabe | 1992-2022 | 1067 | 31.69083 | -111.45 |

| 21 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 6320 | Tinaja Ranch | 1990, 1992, 1994-2022 | 1189 | 31.83826 | -111.1487 |

| 22 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 2080 | Alamo Tank | 1990-2022 | 1204 | 32.28031 | -110.6359 |

| 23 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1050 | Cherry Tank | 1990-2021 | 1231 | 32.51808 | -110.837 |

| 24 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 2030 | Italian Trap | 1990, 1992-2022 | 1244 | 32.28517 | -110.5635 |

| 25 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 2050 | Ranch Rd | 1990-1993, 1995-2022 | 1311 | 32.30989 | -110.6069 |

| 26 | RAWS4 | 021205 | Empire | 1990-2011, 2013-2016, 2018-2022 | 1417 | 31.78056 | -110.6347 |

| 27 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1020 | Oracle R.S. CDO | 1990-2019, 2021 | 1420 | 32.58566 | -110.7859 |

| 28 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1060 | Pig Springs | 1990-2022 | 1465 | 32.52609 | -110.7948 |

| 29 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 6310 | Keystone Peak | 1990-2021 | 1881 | 31.87694 | -111.2152 |

| 30 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1030 | Oracle Ridge | 1990-2021 | 1957 | 32.5328 | -110.7563 |

| 31 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 2150 | White Tail | 1990-1992, 1994-202 | 2490 | 32.41311 | -110.7319 |

| 32 | RAWS4 | 021207 | Rincon | 1995-2022 | 2512 | 32.20556 | -110.5481 |

| 33 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1090 | Mount Lemmon | 1990-2022 | 2786 | 32.44264 | -110.7885 |

| Station Name | Mean Onset (day of year) |

Monsoon Total (mm) |

Annual Total (mm) | No. Years | Elev. (m) | Latitude | Longitude |

| Organ Pipe Cactus NM | 205.33 | 111.49 | 234.81 | 33 | 512 | 31.956 | -112.800 |

| Avra Valley Air Park - Santa Cruz Basin | 209.18 | 105.51 | 206.68 | 33 | 604 | 32.429 | -111.225 |

| Santa Cruz River at Ina Road | 207.70 | 100.15 | 201.24 | 33 | 662 | 32.337 | -111.080 |

| Sells | 192.50 | 195.23 | 322.60 | 22 | 721 | 31.910 | -111.898 |

| Alamo Wash below Glenn St | 202.45 | 131.23 | 244.69 | 33 | 744 | 32.259 | -110.884 |

| Santa Cruz River at Valencia Road | 205.36 | 114.23 | 208.66 | 33 | 750 | 32.133 | -110.993 |

| Tanque Verde Sabino Bridge | 202.30 | 130.59 | 240.29 | 33 | 755 | 32.265 | -110.842 |

| Tucson Int'l Airport | 200.45 | 154.09 | 273.47 | 33 | 778 | 32.132 | -110.956 |

| Tanque Verde Guest Ranch | 195.61 | 174.43 | 328.58 | 33 | 829 | 32.246 | -110.683 |

| Sabino Dam | 200.18 | 152.55 | 302.59 | 33 | 847 | 32.315 | -110.811 |

| Santa Cruz River at Continental Rd | 199.61 | 147.73 | 243.46 | 33 | 871 | 31.855 | -110.979 |

| Santa Cruz River at Canoa Ranch | 196.52 | 173.03 | 271.15 | 33 | 917 | 31.745 | -111.037 |

| Saguaro | 199.19 | 169.61 | 309.14 | 21 | 945 | 32.317 | -110.813 |

| Pantano Vail | 201.34 | 148.65 | 104.41 | 32 | 981 | 32.036 | -110.677 |

| Diamond Bell | 198.76 | 148.17 | 249.32 | 33 | 992 | 31.990 | -111.298 |

| Dodge Tank | 200.03 | 171.17 | 343.37 | 33 | 1006 | 32.512 | -110.864 |

| Catalina State Park | 194.73 | 178.18 | 348.69 | 33 | 1009 | 32.526 | -110.795 |

| Elephant Head | 191.88 | 191.82 | 306.42 | 33 | 1058 | 31.727 | -110.969 |

| Davidson Canyon | 191.52 | 210.89 | 360.39 | 33 | 1061 | 31.994 | -110.645 |

| Sasabe | 191.94 | 208.99 | 334.04 | 31 | 1067 | 31.691 | -111.450 |

| Tinaja Ranch | 194.35 | 189.03 | 310.90 | 31 | 1189 | 31.838 | -111.149 |

| Alamo Tank | 196.67 | 167.40 | 345.44 | 33 | 1204 | 32.280 | -110.636 |

| Cherry Spring | 196.94 | 192.16 | 379.87 | 33 | 1231 | 32.518 | -110.837 |

| Italian Trap | 194.03 | 208.11 | 393.66 | 32 | 1244 | 32.285 | -110.564 |

| Ranch Road | 196.67 | 177.29 | 360.22 | 33 | 1311 | 32.310 | -110.607 |

| Empire | 191.28 | 240.36 | 359.13 | 32 | 1417 | 31.781 | -110.635 |

| Oracle Ranger Stn at Canada del Oro | 198.39 | 178.23 | 356.17 | 33 | 1420 | 32.586 | -110.786 |

| Pig Springs | 196.42 | 215.57 | 451.81 | 33 | 1465 | 32.526 | -110.795 |

| Keystone Peak | 189.00 | 219.48 | 328.04 | 33 | 1881 | 31.877 | -111.215 |

| Oracle Ridge | 190.73 | 262.55 | 480.58 | 33 | 1957 | 32.533 | -110.756 |

| White Tail | 188.78 | 402.34 | 772.65 | 32 | 2490 | 32.413 | -110.732 |

| Rincon | 188.11 | 350.55 | 574.48 | 28 | 2512 | 32.206 | -110.548 |

| Mountain Lemmon | 188.30 | 411.99 | 809.18 | 33 | 2786 | 32.443 | -110.789 |

| Year | Month-day | Phase |

| 1994 | 28 Jun | Peak |

| 1999 | 30 Sep | Valley |

| 2004 | 9 Feb | Peak |

| 2008 | 4 May | Valley |

| 2011 | 30 Dec | Peak |

| 2015 | 28 Nov | Valley |

| 2020 | 10 Jul | Peak |

| Period = 8.7 years | ||

| Station Name | Elev. (m) | Intercept | Slope | P-value | R2 |

| Organ Pipe Cactus NM | 512 | 724.9356 | -0.2590 | 0.5658 | 0.0108 |

| Avra Valley Air Park - Santa Cruz Basin | 604 | 1365.7159 | -0.5765 | 0.1370 | 0.0699 |

| Santa Cruz River at Ina Road | 662 | 1260.9811 | -0.5251 | 0.1757 | 0.0583 |

| Sells | 721 | -1402.0401 | 0.7930 | 0.0890 | 0.1378 |

| Alamo Wash below Glenn St | 744 | 1206.7955 | -0.5007 | 0.2027 | 0.0518 |

| Santa Cruz River at Valencia Road | 750 | 1581.5329 | -0.6860 | 0.1000 | 0.0849 |

| Tanque Verde Sabino Bridge | 755 | -486.2538 | 0.3432 | 0.3790 | 0.0251 |

| Tucson Int'l Airport | 778 | 553.7841 | -0.1761 | 0.6536 | 0.0066 |

| Tanque Verde Guest Ranch | 829 | 341.0947 | -0.0725 | 0.8162 | 0.0018 |

| Sabino Dam | 847 | 761.3523 | -0.2797 | 0.3317 | 0.0304 |

| Santa Cruz River at Continental Rd | 871 | -183.8939 | 0.1912 | 0.6811 | 0.0055 |

| Santa Cruz River at Canoa Ranch | 917 | 321.2197 | -0.0622 | 0.8656 | 0.0009 |

| Saguaro | 945 | 0.6035 | 0.0987 | 0.8797 | 0.0012 |

| Pantano Vail | 981 | 1960.0453 | -0.8765 | 0.0263 | 0.1540 |

| Diamond Bell | 992 | 81.4280 | 0.0585 | 0.8275 | 0.0016 |

| Dodge Tank | 1006 | 1707.8826 | -0.7517 | 0.0439 | 0.1246 |

| Catalina State Park | 1009 | 881.9432 | -0.3426 | 0.3283 | 0.0308 |

| Elephant Head | 1058 | 1589.1061 | -0.6965 | 0.0038 | 0.2399 |

| Davidson Canyon | 1061 | 1356.0947 | -0.5805 | 0.0811 | 0.0949 |

| Sasabe | 1067 | 1431.7435 | -0.6177 | 0.0521 | 0.1239 |

| Tinaja Ranch | 1189 | -72.4807 | 0.1330 | 0.6373 | 0.0078 |

| Alamo Tank | 1204 | 1731.3371 | -0.7650 | 0.0441 | 0.1244 |

| Cherry Spring | 1231 | 582.4508 | -0.1922 | 0.5592 | 0.0111 |

| Italian Trap | 1244 | 1590.9192 | -0.6962 | 0.0446 | 0.1277 |

| Ranch Road | 1311 | 1615.3485 | -0.7072 | 0.0346 | 0.1362 |

| Empire | 1417 | 496.2033 | -0.1520 | 0.6082 | 0.0089 |

| Oracle Ranger Stn at Canada del Oro | 1420 | 626.8144 | -0.2136 | 0.5863 | 0.0097 |

| Pig Springs | 1465 | 1050.5833 | -0.4258 | 0.1835 | 0.0563 |

| Keystone Peak | 1881 | 591.2727 | -0.2005 | 0.4065 | 0.0223 |

| Oracle Ridge | 1957 | 1396.8750 | -0.6013 | 0.0437 | 0.1249 |

| White Tail | 2490 | 1264.1146 | -0.5359 | 0.0524 | 0.1197 |

| Rincon | 2512 | 755.9179 | -0.2827 | 0.3621 | 0.0320 |

| Mountain Lemmon | 2786 | 1634.4735 | -0.7209 | 0.0322 | 0.1396 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).