1. Introduction

The aviation industry has witnessed remarkable growth, leading to an increasing demand for airport facilities and services. As airports expand and operate under higher traffic volumes, the importance of effective maintenance management becomes more pronounced. Meeting the demands of various stakeholders while optimizing resource allocation presents a complex challenge. Previous research has mainly concentrated on advancing optimization models, often overlooking their applicability in real-world scenarios.

The primary objective of the airport pavement maintenance decision-making system is to efficiently maintain or improve pavement conditions within a limited budget. This not only ensures user safety but also extends the overall lifespan of the pavement, resulting in cost savings. Airport management entities strive to establish effective maintenance strategies to balance short-term requirements and long-term sustainability.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) provides guidance for individual airport management entities to develop their pavement management systems [

1], with most management organizations applying FAA guidelines as the basis for their procedures. Korea Airports Corporation maintains and manages the pavements of 15 domestic and international airports in the country. Maintenance methods and time are determined based on functional factors such as pavement surface distress, skid resistance, and longitudinal profile. Additionally, structural stability assessments are conducted to determine remaining life of the pavement and allowable loads for aircraft. However, a challenge arises from the separation of functional and structural assessments within the decision-making process, as well as the absence of evaluation indices reflecting each country’s environmental conditions. The Pavement Condition Index (PCI), widely used in most countries, has limitations in explaining structural damage phenomena, such as blow-ups, which have been a concern in Korean pavements over the past decade. Furthermore, the estimation of remaining service life is based on “the past damage” concept, which is the ratio of accumulated traffic volume to the allowable load repetitions, leading to limitations in determining maintenance methods based on functional assessment and timing based on structural evaluation. When the structural remaining lifespan is less than 5 years (LEVEL I), immediate maintenance is deemed necessary, and for cases between 5 and 10 years (LEVEL II), continuous monitoring and maintenance planning are required. For cases exceeding 10 years (LEVEL III), a long-term maintenance plan is established. In this process, a comprehensive assessment is made based on functional evaluation factors, including visual inspections and lab tests, to justify the maintenance plan. It is observed that the emphasis is more on qualitative and subjective judgments rather than consistent linkage between pavement condition, predicted performance, and budget conditions at the assessment stage.

It is essential to recognize that the challenges faced in Korean airport pavement management are not unique to this context. Budget allocation issues are closely linked to national policies, and implementing maintenance based solely on optimization analysis results is difficult to accept practically. Additionally, the nature of public servant systems, which tend to maintain existing regulations and practices, makes it challenging to create an environment where the effectiveness of budget allocation can be clearly evaluated relative to the budget invested.

From a technical perspective, improvements are also necessary. Decision-making systems must compare costs and associated effects for each maintenance method, which can be challenging due to the difficulty of quantifying environmental factors, traffic closure times, user satisfaction, and other non-monetary elements consistently.

Despite the academic advancements in optimization technology, practical airport pavement management systems have not progressed significantly. In this paper, we first examine the underlying reasons for this situation and then aim to develop a decision-making system that can flexibly adapt to the spectrum of budgets. Considering the difficulty of rapid changes in annual budgets for individual airports and the need for equitable budget allocation, our system is designed to address these challenges. Secondly, we seek to improve the decision-making system by enhancing each stage’s component model, including evaluation indices, performance curves, cost, effects, and optimization models. Our goal is to elevate the system’s theoretical validity and rationality using academic research outcomes while simultaneously meeting the practical needs of airport managers.

2. Related Literutures

The key components of pavement management systems are the evaluation of pavement conditions and the decision-making process regarding maintenance methods and timing. The dominant airport pavement evaluation index is the Pavement Condition Index (PCI), developed by the United States Corps of Engineers in 1980s [

2]. The FAA utilizes the Structural Condition Index (SCI) as part of PCI, which is associated with structural deterioration, including rutting and alligator cracking. In addition, functional evaluations encompass longitudinal profile, skid resistance, and PCI excluding SCI to assess functional performance [

3] Y. Hachiya [

4] introduced the Pavement Rehabilitation Index (PRI) as a Japanese airport pavement evaluation index, adopting cracking, rutting, and profile as key factors.

Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands emphasizes the equal importance of functional and structural pavement performance. They evaluate functional performance using PCI, profile, and skid resistance, and adopt PCN method and remaining life analysis as alternatives for assessing structural performance [

5]. Amsterdam Airport, Belgium, and Italy have adopted the PCN method, only [

6]. The ACN-PCN system (currently changed to ACR-PCR) was developed to assess aircraft operational suitability, explicitly stating that it cannot be used as an evaluation basis for design and maintenance decisions [

7].

Pavement performance models have been developed using different modeling methods, including mathematical methods, soft computing methods, and hybrid models combining both [

8]. The Markov Chain Method stands out as one of the most widely used approaches. Its advantage lies in its ability to analyze with limited data. Experts can estimate pavement condition change probabilities based on knowledge and experience [

9]. Examples of applying the Markov Chain Method in pavement management include a 1982 study by Golabi et al. on optimal maintenance method determination for Arizona state roads [

10].

Traditional methods such as Ranking have been used to prioritize decisions for maintenance [

11]. and the Decision Tree Method was introduced by Darter et al. in 1985 [

12]. There are cases applying decision models with multivariate variables [

13], and the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) technique, which determines importance through pairwise comparisons [

14]. The Worst-fit method, prioritizing higher rankings as conditions worsen, is relatively straightforward and intuitive, but it has limitations in overall improvement of the entire management target [

12]. Since the 2010s, there has been a trend in developing priority models using artificial intelligence technology and GIS-based approaches [

15]. When using optimization models, the prevalent approach for airport pavement is to estimate individual damage over time and traffic volume and derive an integrated index, rather than using the former method.

Linear programming has been used in pavement management since its introduction in the late 1980s [

16] and continues to be employed [

17]. Integer linear programming has been predominantly used, offering the advantage of shorter calculation times due to its relatively simple modeling [

18,

19,

20]. Yanfeng Ouyang [

21] introduced Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) and expanded it from single to multiple facilities. Hwasoo Yeo [

22] also attempted to develop optimization models for multi-facilities using a bottom-up approach. Unlike the models mentioned earlier, they defined costs with Expected Cost-To-Go (ECT). Lee [

23] proposed effective dynamic programming solution for optimizing reconstruction intervals jointly with maintenance and surface treats, using discrete approximation method and parametric approximation method.

The literature review revealed a lack of decision-making systems that comprehensively consider both functional and structural aspects of pavement. While research on decision methodologies has been ongoing, it has been challenging to find examples that link evaluation indices, costs, and effects by pavement type. This identified the need to improve the component models necessary for the step-by-step analysis of decision-making systems, including optimization methods. Furthermore, we aimed to validate the applicability through case studies using actual pavement evaluation data.

3. Airport Paement Management System Architecture

3.1. System Architecture

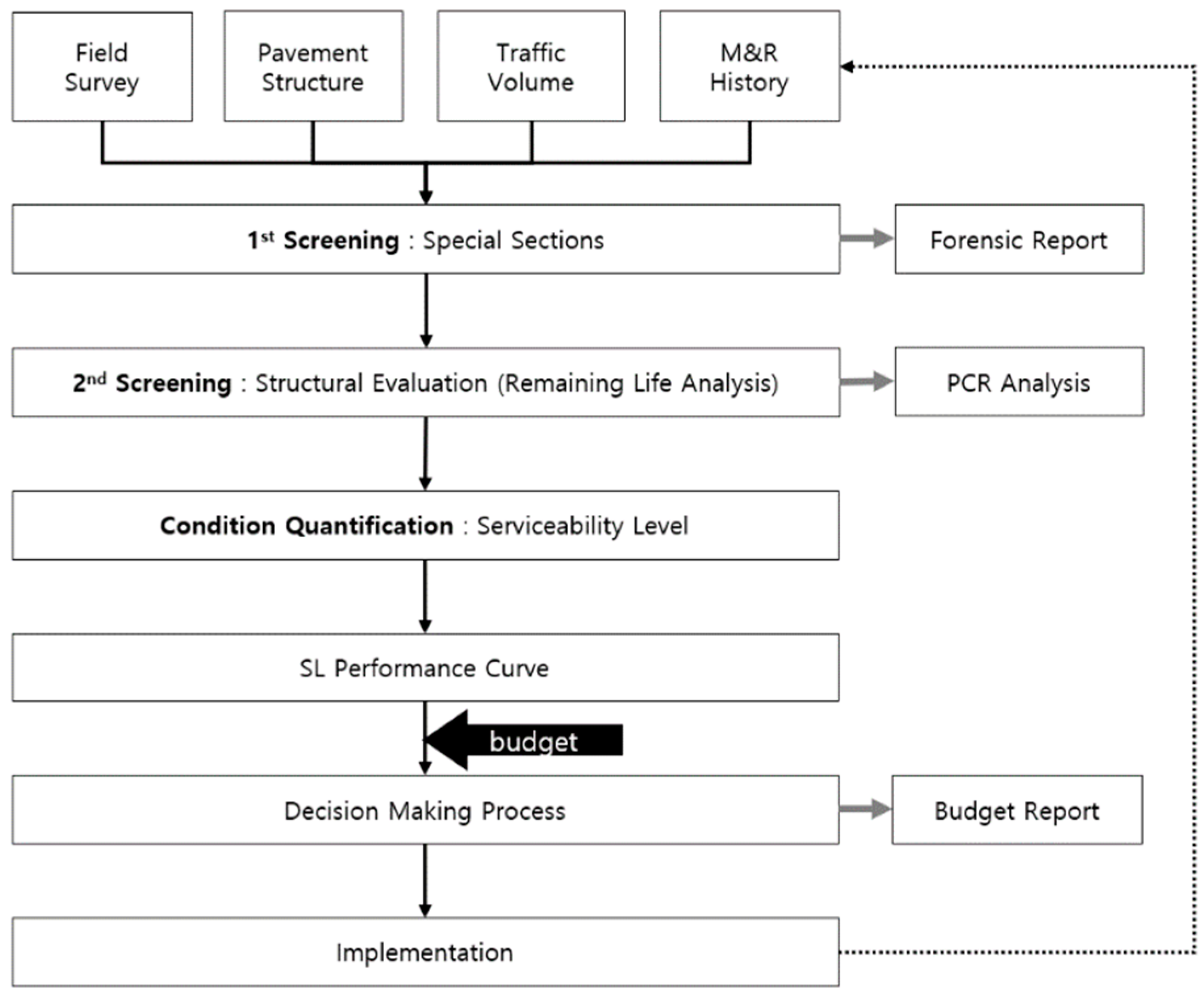

The architecture of the airport pavement maintenance decision-making system proposed in this paper is as follows (

Figure 1). To overcome the limitations mentioned earlier, a key feature of this system is the integration of structural and functional evaluation factors into a single system, incorporating specific segment procedures with a clear sequence.

In cases where phenomena that are difficult to explain using conventional general serviceability prediction models are observed after indoor and field evaluations, special sections are separated. This includes scenarios where there is a risk to safety, such as abrupt climate changes, traffic variations, excessive occurrence of specific defects due to construction management issues, or sudden decreases in skid resistance. Additionally, structural elements, represented by remaining life, are placed before comprehensive performance evaluations. In this phase, the remaining life at the evaluation point is estimated to determine the need for urgent maintenance, and the Pavement Classification Rating (PCR) is calculated for determining allowable take-off weight of aircraft. Budget considerations are primarily conducted for sections that do not fall into these two categories.

After separating the first and second special sections, “Serviceability Level” (SL) is calculated to quantitatively assess pavement conditions comprehensively. Based on maintenance history, serviceability prediction curves for runways, aprons, and taxiways are developed, and they are applied as input variables for decision-making, along with cost and effectiveness for different maintenance methods. The Condition Cases Optimization method, tailored to reflect the rationality of the system and the characteristics of domestic airports, is introduced to ensure practical applicability.

Through the decision-making process, a budget sensitivity report is generated, and after actual maintenance methods are implemented, the maintenance history is stored in the maintenance database.

3.2. Condition Index: Serviceability Level(SL)

In accordance with the perspectives of various stakeholders such as airport managers, pilots, and passengers, the demands placed on airport pavement vary significantly. Airport managers prioritize efficient budget allocation and pavement maintenance, while pilots focus on the safe takeoff and landing of aircraft, and passengers prioritize a comfortable driving experience. To accommodate these diverse considerations, the decision-making model adopted in this study is based on the Serviceability Level (SL) developed through collaborative research between the Korea Airports Corporation (KAC) and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). This unique index takes into account the specific conditions in Korea, departing from the mega-index SL concept introduced by the FAA [

24] and tailored to the domestic context [

25].

SL is expressed as a numerical value ranging from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 100, characterized by hierarchy and comprehensiveness. It is constructed from a perspective that seeks facilities that are safe, sustainable, and comfortable. Factors influencing safety (SAFE) are subdivided into categories related to material or construction-induced distress (MCD: Material and Construction Related Distress) and skid resistance (F: Friction). SUSTAINABLE (SUS) comprises categories related to design-related distress (DD: Design-Related Distress) and structural stability (SS: Structural Stability). Structural stability is calculated as a weighted sum of deflection indices, such as Base Layer Index (BLI), Middle Layer Index (MLI), and D8(measured deflection from the sensor located 60inch offset from the loading plate), using the deflection measurements collected from the Heavy Weight Deflectometer (HWD) test data, adjusted based on daily and monthly temperature change. When DD&SS values are evaluated as poor, extensive maintenance such as full-depth repairs or re-pavement methods is necessary. Lastly, COMFORT evaluates longitudinal profile (P: Profile) as an indicator affecting aircraft vibrations. The Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) was chosen as the methodology for determining the weightings between these constituent elements. Developed by Saaty in 1980, AHP simplifies complex problems into pairwise comparisons, enabling informed decision-making [

26]. Weighted averages were applied to the responses of 18 Korean and 3 U.S. highway/airport pavement experts. The final weights were then used to derive the SL formula(Equation 1 ~ Equation 4) [

25].

3.3. SL Performance Curve

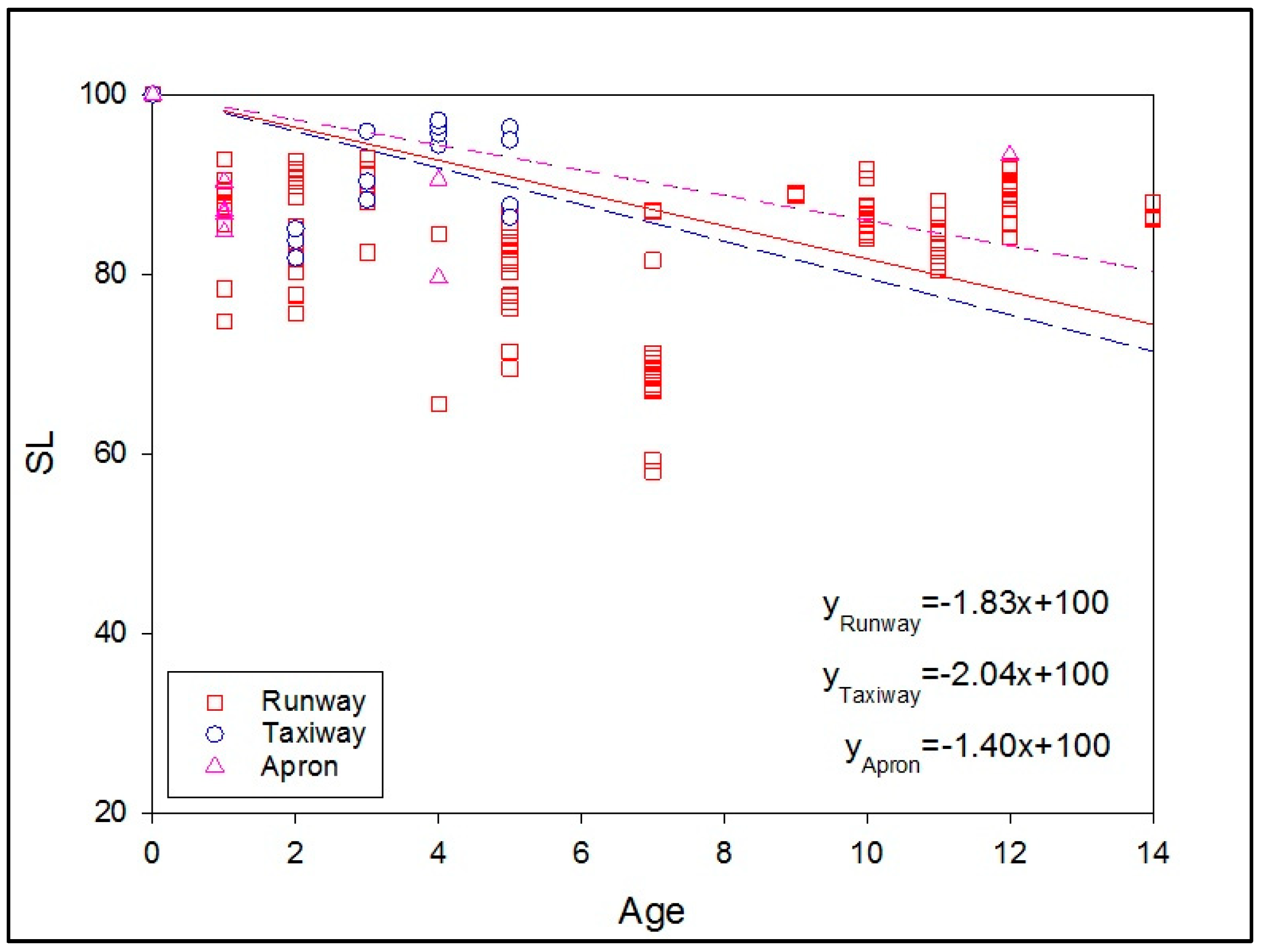

A relationship between the maintenance history and SL scores was analyzed to develop performance curves for pavement serviceability. Data collection commenced after the establishment of the airport pavement management system in 2011 and given that regular assessments are conducted every five years, as of 2023, a maximum of three sets of evaluation data have been accumulated. To reflect the actual behavior of pavements, various curve shapes such as linear, nonlinear, and polynomial were considered. However, at this stage, a relatively simple linear formula was adopted to enhance practical applicability. It was assumed that the pavement would return to its original design condition (100 points) upon reconstruction or overlay.

Figure 2 illustrates the SL performance curves for runways, taxiways, and aprons.

3.4. Decision Making Process for Airport Pavement Management System

3.4.1. Determination of Cost and Effect for M&R Methods

For the stable and efficient operation of a Pavement Management System (PMS), it is crucial to quantify the costs and benefits of alternative maintenance methods and establish selection criteria [

27]. The determination of pavement methods and costs was informed by domestic and international cases, including reports from agencies like the Minnesota Department of Transportation [

28], and the Airport Cooperative Research Program (ACRP) [

29] and academic papers such as Noruzoliaee [

30], Limon Barua [

31], and Hosseini [

32]. Additionally, references were made to maintenance manuals from the Korea Expressway Corporation [

33] and the Korea Airports Corporation [

34].

Pavement maintenance methods are generally categorized into preventive maintenance, major rehabilitation, and reconstruction [

11]. Among the major rehabilitation methods applied to Korean airport flexible pavements, 62% were 7.5cm milling and overlay, 10% were 5cm thin milling and overlay, and 14% were 10 cm to 25cm milling and overlays [

35]. To evaluate the effectiveness of various methods used for highway, this study selected resurfacing, partial repair, mill & overlay by thickness, patching, slurry sealing, fog sealing, and crack maintenance as alternatives.

While primarily referring to the Korea Airports Corporation’s data, for methods with limited case studies, practical costs were determined by giving higher weights to data from the Korea Expressway Corporation and the ACRP. The costs of other methods were distributed based on the least expensive method, crack maintenance (

$2.35/M2), and the most expensive method, reconstruction(

$105.75/M2), serving as references. Preventive maintenance aims to extend the expected service life of the pavement, so the immediate recovery of the pavement condition is minimal. Through consultations with researchers from the Korea Expressway Corporation, the study assigned lifespan extension effects of 3.5 years, 4 years, 3 years, and 2 years for patching, slurry sealing, fog sealing, and crack maintenance, respectively. For major rehabilitation methods like milling and overlay, it was assumed that the pavement condition increases to 95, and the expected service life extends up to 10 years. Thickness criteria of 5 cm, 7.5 cm, and 15 cm were selected for milling and overlay based on Korean pavement evaluation data. Resurfacing was assumed to fully restore the pavement’s structural capacity, resulting in an SL recovery level of 100 and an extended service life of 30 years. During reconstruction implementation, it was considered that the affected section would be closed for 3 years, but the pavement condition would be maintained to prevent negativity for benefit calculation. Furthermore, it was assumed that as the number of applications accumulates, the expected lifespan extension effect diminishes in a 5:3:2 ratio [

36].

Table 1.

Cost and effect of M&R methods used in the analysis.

Table 1.

Cost and effect of M&R methods used in the analysis.

| Category |

Alternatives |

Unit Cost

($/m2) |

SL after

implementation |

Life Extension(yr) |

| 1st

|

2nd

|

3rd

|

| Reconstruction |

Reconstruction |

105.75 |

100 |

30 |

- |

- |

Major

Rehabilitation |

15cm M/OL*

|

78.96 |

95 |

10 |

6 |

4 |

| 7.5cm M/OL*

|

56.40 |

8 |

4.8 |

3.2 |

| 5cm M/OL*

|

47.00 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

| Preventive Maintenance |

Patching |

58.75 |

- |

3.5 |

- |

- |

| Slurry Seal |

16.45 |

4 |

- |

- |

| Fog Seal |

9.40 |

3 |

- |

- |

| Crack Sealing |

2.35 |

2 |

- |

- |

3.4.2. Benefit

User benefits for B/C analysis is defined as shown in [Equation 5]. The most common method for calculating is the area under the pavement condition curve (AUC) between the PCI, IRI, and the threshold scores [

37]. In this paper, we considered the delay effects due to traffic closure, specifically applying it to the reconstruction maintenance method among the three maintenance method categories. Based on domestic experience, especially in airports with high traffic volumes, unit costs for minimizing traffic closure times were 2.4 times higher for pre-cast methods and 3.5 times higher for rapid-setting methods compared to 7.5 cm milling and overlay [

25]. User benefits due to preventing traffic closure were calculated at

$670/m² compared to general concrete pavement partial repairs. In this paper, we conducted a cost-benefit analysis limited to flexible pavement maintenance methods.

The traffic volume groups were categorized as a high, medium, and low groups, based on the number of annual departures in equivalent B737-900ER aircraft. The distribution of airport groups in South Korea was 23% for high traffic, 62% for medium traffic, and 15% for low traffic. The λ coefficient is determined based on the traffic volume group and the number of runways. As λ increases, the importance of method application becomes higher compared to closure effects. The highest λ values were observed in the C traffic group and when there were three or more runways. Conversely, under opposite conditions, the reduction in the closure effect is most significant, with the most extreme case being when traffic is high and there is only one runway.

Where, AUC = Area Under Curve and λ = factor on number of runways and traffic volume

Table 2.

λ factor for number of runways and traffic volume.

Table 2.

λ factor for number of runways and traffic volume.

| # of Runways |

1 |

2 |

3 or more |

| Traffic Volume |

High |

Med |

Low |

High |

Med |

Low |

High |

Med |

Low |

| λ |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

| 1- λ |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

3.4.3. Optimization Method

Traditional network optimization methods are divided into top-down and bottom-up approaches for distributing budgets based on pavement condition assessments at each airport and determining pavement maintenance methods through detailed investigations. In this paper, we adopted a dual optimization bottom-up approach that first generates a set of possible alternatives through single facility (section) optimization and then prioritizes them through multi-facility optimization.

The objective function of the optimization problem is to maximize the total B/C ratio of all evaluation sections within the network. Here, B represents benefits, C represents costs, i represents facilities, x represents integer coefficients, L represents the set of applicable pavement maintenance methods for homogeneous sections, and K represents the number of homogeneous sections. The constraints include that the total cost of the selected set of maintenance methods cannot exceed the total budget and only one maintenance method set can be chosen for each section. Here, t represents one year, and N represents the analysis period. The optimization technique selected for this purpose was Brute-Force, and the coding was done in Python.

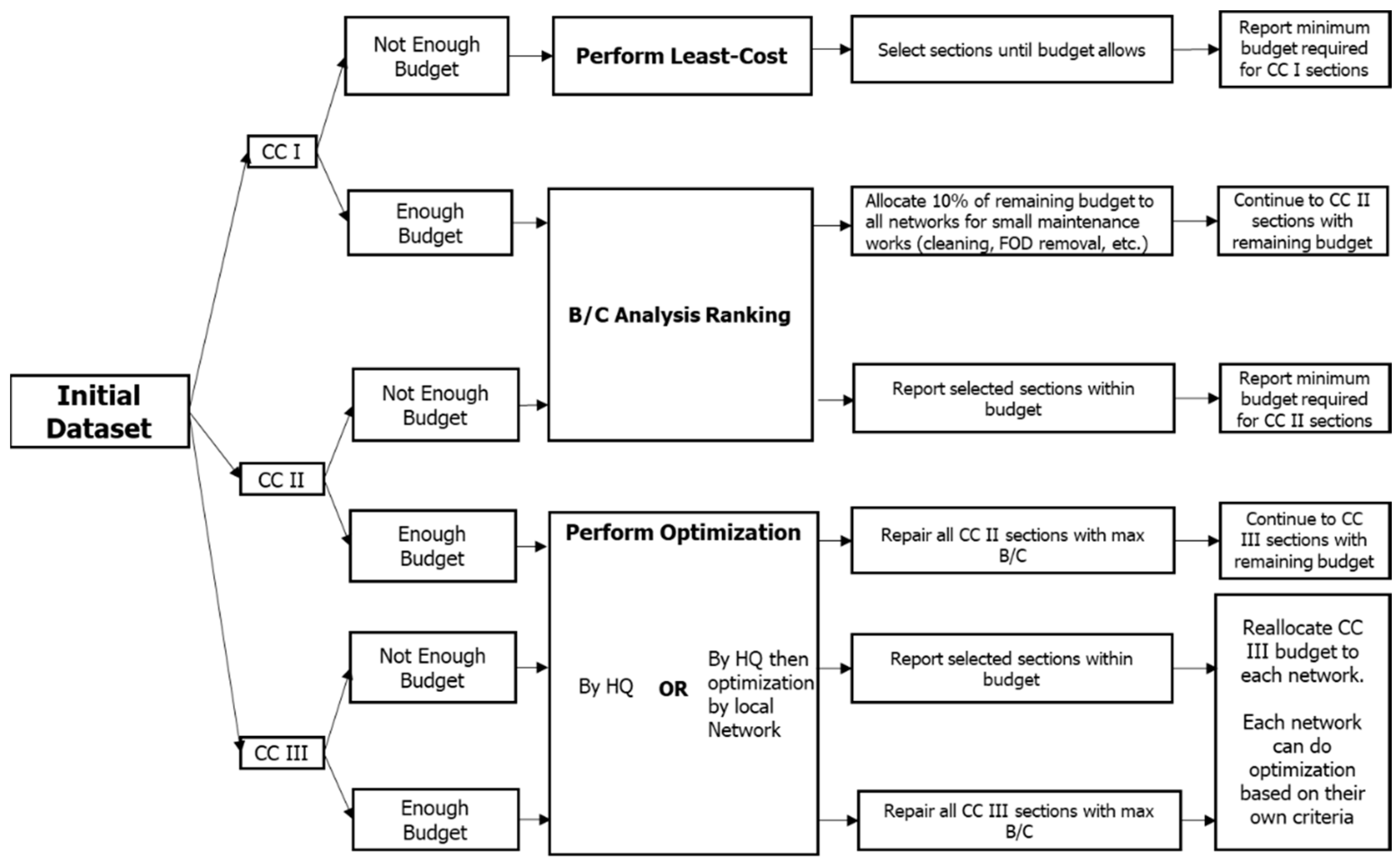

A procedure has been developed that considers the current condition of the pavement to determine the prioritization of M&R application. Subsequently, we estimate the required budget for the remaining sections through optimization modelling. This approach, termed Condition Cases Optimization (CCO), is summarized in

Figure 3 based on budget and initial conditions. Through condition assessments, we classify the homogeneous sections constituting the network into CC I, II, and III. The budget conditions are divided into three cases. The first case is when there is insufficient budget to rehabilitate CC I. The second case is when there is enough budget to rehabilitate CC I, but it is not sufficient to cover all of CC II. The last case is when there is enough budget to fully rehabilitate CC II. Although the last case can be further divided into cases where the budget is insufficient or sufficient for CC III, they are considered the same in terms of applying network optimization methods.

In cases where the budget is very limited to address CC I, ranking is determined based on the minimum cost among alternatives rather than B/C analysis. The minimum required budget to cover CC I is calculated, but as it may be insufficient to address all possible methods, priorities are determined based on cost within the budget range. In the second case, prioritization is based on B/C analysis. After allocating the necessary budget for CC I, 10% of the remaining budget is evenly distributed among airports. This is assumed to cover minimal maintenance such as pavement surface cleaning and FOD removal. With the remaining amount, the applicable CC II and corresponding methods are selected, and similar to the first case, the minimum budget required to cover CC II is reported, but in this case, priorities are determined based on B/C rather than minimum cost. In the third condition where there is sufficient budget for CC II rehabilitation, network optimization is conducted. Network optimization can be performed either at the headquarters or individually by each airport. In other words, through initial optimization analysis, the necessary budget for each airport is allocated. Airports can either follow these results or, based on their philosophy, utilize SUS, SAFE, and COMF as reference scores within their allocated budget to conduct optimization and apply maintenance and rehabilitation methods to homogeneous sections accordingly.

3.4.4. Sensitivity Analysis

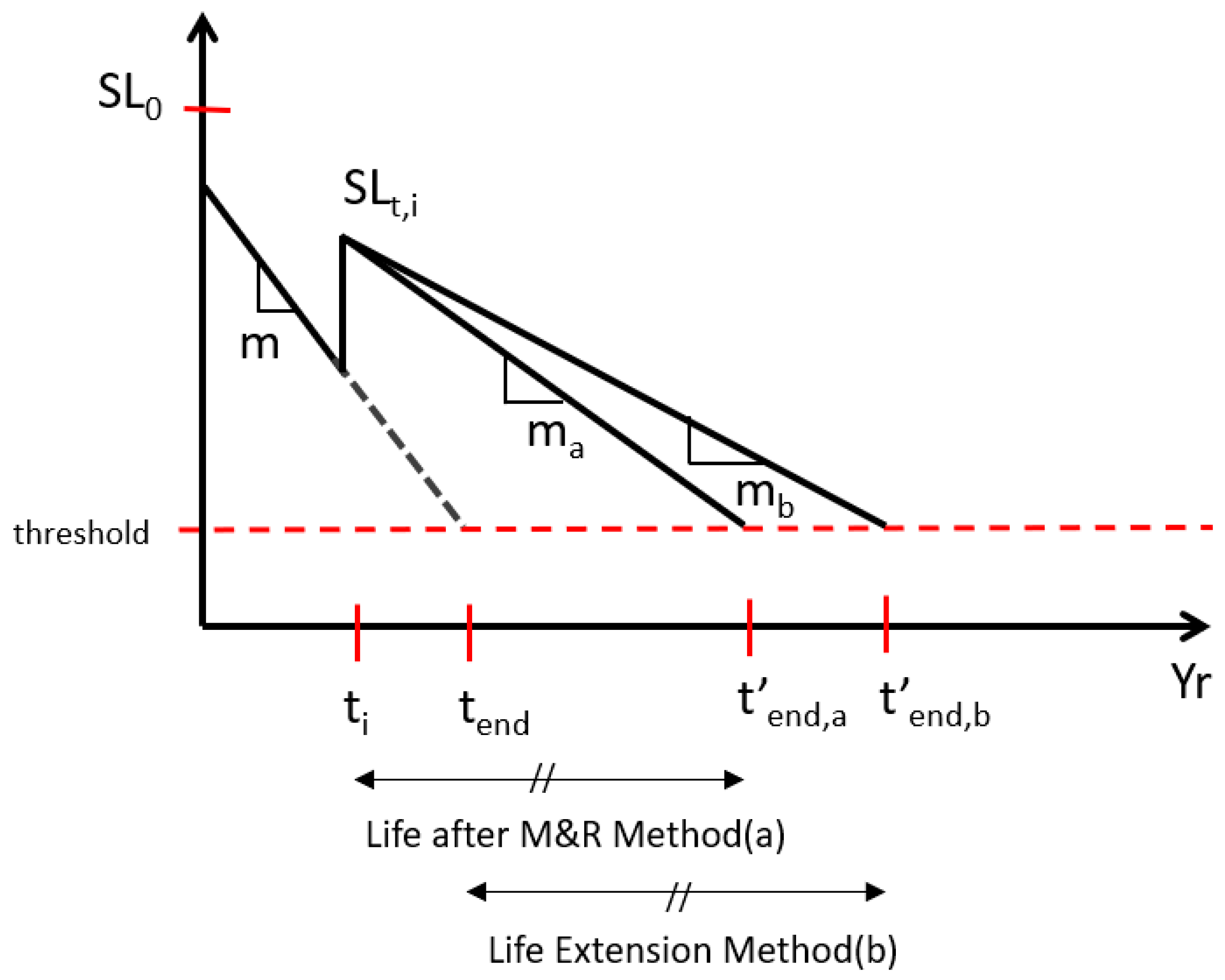

Sensitivity analysis was conducted by varying input variables for flexible pavement. For comparison, we included the results for Do-nothing (DN) and Network Optimization (NO), which represents the application of the conventional network optimization. Analysis was performed using variables such as the minimum SL threshold, budget, analysis period, the lifespan extension effect after method application, and M&R cost, as shown in [

Table 3]. For the minimum SL threshold, we examined cases with ±15 points around the SL of 65 points, specifically considering thresholds of 50 and 80 points. Regarding the budget, we initially applied a value of

$1,000 and tested variations of ±10% and ±20%. We expanded the analysis period from the initial 5 years to 7 and 10 years. To calculate the change in the slope of the Serviceability Level (SL) performance curve after M&R, we divided the analysis into two cases: one where the overall lifespan is extended and another where the lifespan is extended for a specific number of years from the time of method application (

Figure 4). Where,

= SL score at the evaluation,

= Original slope of SL performance curve,

= M&R method,

= time when M&R method

is applied,

= SL score at

,

= original time of end of life,

= time of end of life after applying method

(Life after M&R method),

= time of end of life after applying method

(Life extension method),

= slope of the SL performance curve after applying method

(Life after M&R method),

= slope of the SL performance curve after applying method

(Life extension method ).

Furthermore, we examined the results by varying the expected lifespan extension level after method application and the costs associated with each method by ±20%. The lifespan extension effect was increased or decreased by 20%, and this effect was also adjusted by the same ratio for second and third applications of the method.

The analysis results are summarized in

Table 4. Total budget allocation showed significant variations in CCO’s total B/C. When it decreased by 10%, there was approximately a halving effect, and when it decreased by 20%, it dropped sharply by 2%. When analyzing the two methods of lifespan extension effects, NO and CCO methods exhibited a difference of more than 2-fold in total B/C, with no significant difference in SL after the analysis period (5 years). When extending the analysis period from 5 years to 7 and 10 years, NO’s total B/C increased, while CCO’s B/C was higher than that for 5 years, particularly showing the highest value at the 7-year analysis period. After the analysis period, SL showed a similar decrease rate for all alternatives.

When adjusting the costs for maintenance methods, a 20% cost reduction resulted in an approximately 1.3-fold increase in total B/C. However, when costs increased by 20%, particularly in the case of CCO, it showed a significant decrease of 8% compared to the initial value, indicating high sensitivity.

4. Case Study

We compared the average SL at the end of the analysis period with the DN scenario using actual pavement evaluation data from 164 homogeneous flexible pavement sections, including runways, aprons, and taxiways.

Table 5 provides information on airport-specific equivalent annual takeoff traffic, traffic groups, branch configurations, λ weights, and the number of sections corresponding to CC I, II, and III. In the case of Airport C, there were two sections falling under CC I, while for CC II, Airport A had three sections, and Airport C had fifteen sections. Annual traffic was converted using the B737-900ER aircraft, and λ values were determined based on the runway numbers and traffic group, with respective values of 0.6, 0.2, 0.4, and 0.7.

When analyzed under the condition of sufficient budget, the annual average SL over the years is as shown in

Figure 5. For DN, the average SL decreases steadily over time, starting from an initial average of 86 points and reaching approximately 76 points after 5 years. When the NO method is applied, the SL increased to 87 points in the subsequent years after the analysis, gradually declining to about 80 points. Considering the domestic airport pavement, which is generally well-maintained, it seems reasonable that tere was little difference in the numerical values.

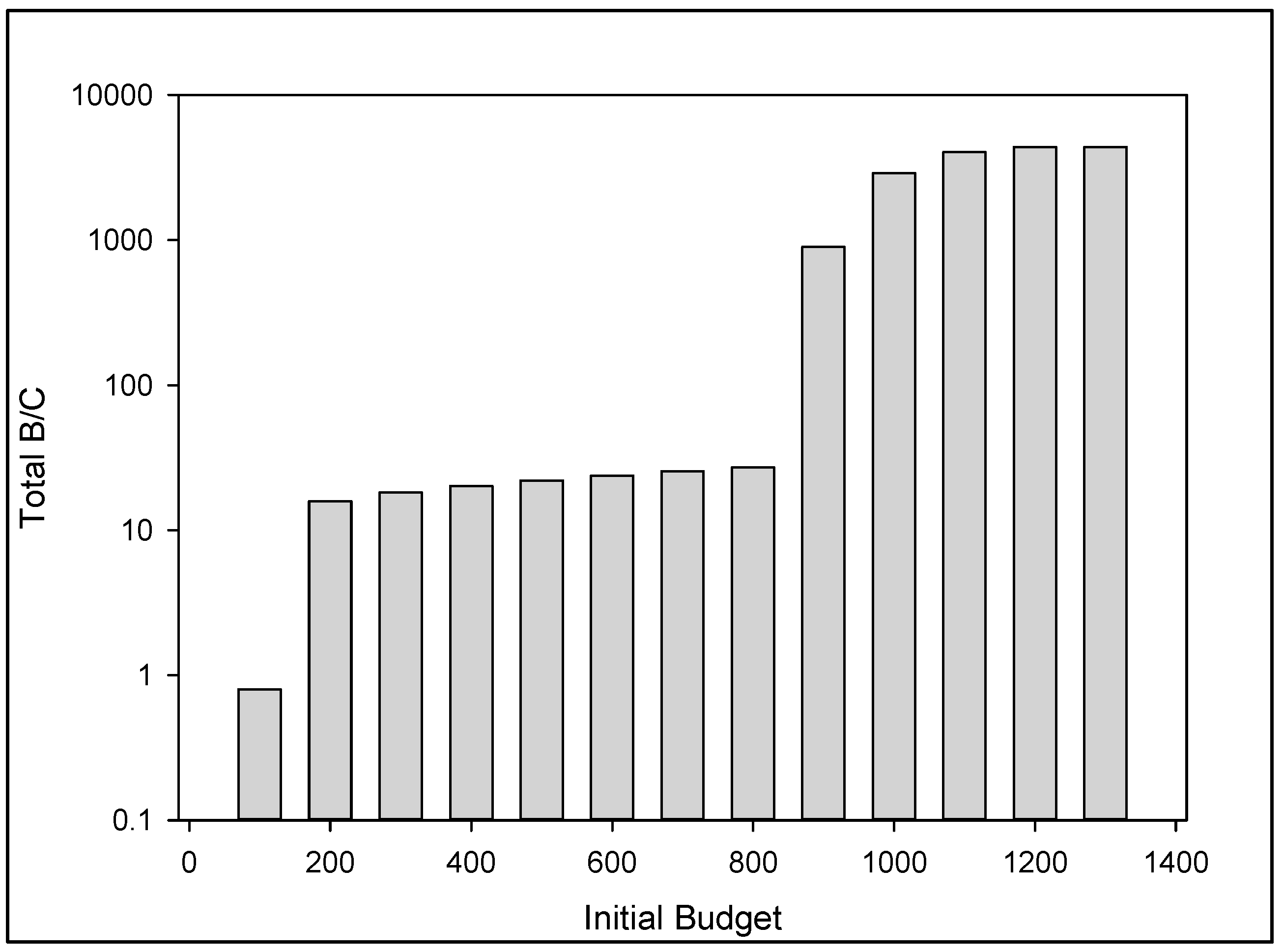

To examine the effect of the budget, one of the advantages of the decision-making method presented in this paper, the total B/C was evaluated while incrementally increasing the budget from 0 to 2400 in increments of 400 (as shown in

Figure 6). Initially, for the CC I, where immediate maintenance is required, the B/C was around 1. Afterward, for CC II, it increased to approximately 50 after a budget of 200. However, for CC III, starting from 800, the B/C rapidly increased to 10,000 or more. This steep increase likely occurred because high-scoring CC III segments, which were initially in good condition, began to be included in the maintenance targets, leading to a rapid increase in the B/C.

5. Conclusion

The objective of this study was to develop a rational and efficient airport pavement management system. The Condition Cases Optimization (CCO) method was introduced which addresses the limitations of conventional network optimization and enhances its practical applicability. It categorizes pavement conditions into three groups, allowing for the allocation of resources based on the current state of the pavement. The method accommodates varying budget constraints, making it adaptable to the financial realities of different airports. It offers strategies for decision-making under different budget scenarios, ensuring that airport managers can make informed choices. The sensitivity analysis conducted in the study emphasizes the method’s flexibility and adaptability. It identifies key factors that influence decision outcomes, such as the initial budget, maintenance method costs, and SL threshold scores. The CCO method’s applicability was validated using evaluation data from four South Korean airports. Results of the case study demonstrate that the proposed procedure can be effectively utilized in field. In summary, the study’s findings underline the potential of the CCO method as an effective decision-making tool for airport pavement management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y. Cho and W. Lin.; methodology, J. Lee and S. Roh.; software, I. J. Urbino and Y. Cho.; validation, W. Lin., S. Roh and Y. Cho.; formal analysis, I. J. Urbino.; investigation, S. Roh.; resources, Y. Cho.; data curation, J. Lee and W. Lin.; writing—original draft preparation, S. Roh.; writing—review and editing, W. Lin and Y. Cho.; visualization, W. Lin.; supervision, Y. Cho and W. Lin.; project administration, Y. Cho.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the BK21 FOUR (Fostering Outstanding Universities for Research) research team “SURE”. The APC was funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE, Korea) and National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Federal Aviation Administration. Advisory Circular No. 150/5380-6C Guidelines and Procedures for Maintenance of Airport Pavements. FAA, United States, 2014. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/advisory_circulars/index.cfm/go/document.information/documentID/1026067.

- Karballaeezadeh, Nader & Zaremotekhases, Farah & Band, Shahab & Mosavi, Amir & Nabipour, Narjes & Csiba, Peter & Varkonyi-Koczy, Annamaria. Intelligent Road Inspection with Advanced Machine Learning; Hybrid Prediction Models for Smart Mobility and Transportation Maintenance Systems. Energies 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Federal Aviation Administration. Advisory Circular No. 150/5320-6G Airport Pavement Design and Evaluation. FAA, United States, 2021. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/airports/resources/advisory_circulars/index.cfm/go/document.current/documentnumber/150_5320-6.

- Hachiya, Y., Watanabe, T., & Kanno, M.. Development of Airport Pavement Optimal Rehabilitation Timing System and Its Application to Airports in Japan. In Airfield and Highway Pavement 2013: Sustainable and Efficient Pavements; pp. 640-649. [CrossRef]

- Laguado Lancheros, Juan, Wolfert, A. R. M., van Nederveen, G. A., Koutamanis, A., Mooren, F. Airport Pavement Management Decision Making: A Prioritization tool to select pavement sections requiring M&R treatment. Master’s thesis. Delft University of Technology, Netherlands. 2018.

- Di Mascio, P., & Moretti, L. Implementation of a pavement management system for maintenance and rehabilitation of airport surfaces. Case studies in construction materials 2019, 11, e00251. [CrossRef]

- International Civil Aviation Organization. Doc 9157 Aerodrome Design Manual Part 3 – Pavements, ICAO, 2022.

- Fwa, T. F., Chan, W. T., & Hoque, K. Z. Multi objective optimization for pavement maintenance programming. Journal of Transportation Engineering 2000, 126, 367-374. [CrossRef]

- Li, Deng-Feng & Yang, Jian-Bo. Fuzzy linear programming technique for multiattribute group decision making in fuzzy environments. Information Sciences 2004. 158. 263-275. [CrossRef]

- Golabi, K., Kulkarni, R. B., & Way, G. B.. A statewide pavement management system. Interfaces 1982, 12, 5-21. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, W.R., Haas, R. & Uddin, W. Infrastructure Management. McGraw, New York, U.S. 1997.

- Maher Shakir Mahmood. Network-level maintenance decisions for flexible pavement using a soft computing-based framework. Doctoral Theses. Nottignham Trent University, England. 2015.

- Augeri, M. G., Colombrita, R., Greco, S., Lo Certo, A., Matarazzo, B., & Slowinski, R. Dominance-based rough set approach to budget allocation in highway maintenance activities. Journal of infrastructure systems 2011, 17, 75-85. [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.S. Applying AHP-based CBR to estimate pavement maintenance cost. Tsinghua Science & Technology 2008, 13, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantha, B. R., Yatabe, R., & Bhandary, N. P. GIS-based highway maintenance prioritization model: an integrated approach for highway maintenance in Nepal mountains. Journal of Transport Geography 2010, 18, 426-433. [CrossRef]

- Hugo, F., Scholtz, W. J., Sinclair, M., & Curtayne, P. C. Management of pavement rehabilitation. European journal of operational research 1989, 42, 129-141. [CrossRef]

- de la Garza, J. M., Akyildiz, S., Bish, D. R., & Krueger, D. A. Network-level optimization of pavement maintenance renewal strategies. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2011, 25, 699-712. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z., Flintsch, G. W., & Chowdhury, T. Hybrid multiobjective optimization model for regional pavement-preservation resource allocation. Transportation research record 2008, 2084, 28-37. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y., & Madanat, S. Optimal scheduling of rehabilitation activities for multiple pavement facilities: exact and approximate solutions. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2004, 38, 347-365. [CrossRef]

- Priya, S., & Uthra, R. A. Deep learning framework for handling concept drift and class imbalanced complex decision-making on streaming data. Complex & Intelligent Systems 2021, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Yanfeng Ouyang & Samer Madanat. Optimal scheduling of rehabilitation activities for multiple pavement facilities: exact and approximate solutions. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2004, 38, 347-365. [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Hwasoo & Yoon, Yoonjin & Madanat, Samer. Algorithms for bottom-up maintenance optimisation for heterogeneous infrastructure systems. STRUCT INFRASTRUCT ENG 2012, 9. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Madanat, S. Jointly optimal policies for pavement maintenance, resurfacing and reconstruction. EURO Journal on Transportation and Logistics 2015, 4, 75-95. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, Timothy & Murrell, Scott. Validation of FAA-Proposed Airport Pavement Serviceability Level Index Components. In proceedings of Transportation Research Board 2023 Annual Meething at Washington, D.C., U.S. 11 May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Korea Airports Corporation. Development of Serviceability Level and Improvement of Back-calculation. Research project report. KAC, Republic of Korea, 2019.

- Mahmoodzadeh, S., Shahrabi, J., Pariazar, M., & Zaeri, M. S. Project selection by using fuzzy AHP and TOPSIS technique. International Journal of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering 2007, 1, 270-275.

- Pedigo, R. D., Roberts, F. L., Hudson, W. R., & Haas, R. C. PAVEMENT MANAGEMENT: THE NETWORK-LEVEL DECISION PROCESS (ABRIDGMENT). Transportation Research Record 1980, 766. Available online: http://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/trr/1980/766/766-001.pdf.

- Hill, L., Cheetham, A., & Hass, R. Development and implementation of a pavement management system for Minnesota. Transportation Research Record 1991, 1311, 230-241. Available online: https://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/trr/1991/1311/1311-031.pdf.

- Airport Cooperative Research Program. ACRP Synthesis 22 Common Airport Pavement Maintenance Practices. Transportation Research Board. Washinton, DC., U.S. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Noruzoliaee, M., & Zou, B. Airfield Infrastructure Management Using Network-Level Optimization and Stochastic Duration Modeling. Infrastructures 2019, 4, 2. [CrossRef]

- Barua, L., & Zou, B. Planning maintenance and rehabilitation activities for airport pavements: A combined supervised machine learning and reinforcement learning approach. International Journal of Transportation Science and Technology 2022, 11, 423-435. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S. A., & Smadi, O. How Prediction Accuracy Can Affect the Decision-Making Process in Pavement Management System. Infrastructures 2021, 6. [CrossRef]

- Korea Expressway Corporation. Korea Expressway Design and Evaluation Guidelines. KEC, Republic of Korea, 2021.

- Korea Airports Corporation. Upgrade of Korean Airport Management System (KAPMS). Research project report. KAC, Republic of Korea, 2010.

- Korea Airports Corporation. Analytical Logic Improvement Research for Upgrading Airport Pavement Management System (APMS). Research project report. KAC, Republic of Korea, 2022.

- Yeong Hwan, Lim. Improvement of Project Level PMS and Development of Network Level PMS of National Highway in Korea. Doctoral thesis. Chung-Ang University, Republic of Korea. 2003.

- Irfan, M., Khurshid, M.B., Iqbal, S. et al. Framework for airfield pavements management—an approach based on cost-effectiveness analysis. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev 2015. 7, 13. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).