Submitted:

07 November 2023

Posted:

08 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Identify biomarkers of depressed mood in athletes and people in extreme professions.

- Detect genetic determinants of elevated levels of anxiety in the studied population.

- Build models predicting scores in HADS subscales from genetic data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Description

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Psychological Assessment

2.2.2. Genotyping

- Serotonergic system regulates basic biological functions such as sleep, appetite, circadian rhythms, and cognition. Decreased serotonin activity is linked with depression, mania, anxiety disorders, suicidal ideantions and etc [22].

- Dopaminergic system spreads across the mesocortical, mesolimbic, and nigrostriatal pathways regulating multiple functions. The mesocortical pathway is involved in regulation of attention, executive function, and working memory. The mesolimbic pathway is important for motivation and reward processes. Planning and execution of motor function are processed in the nigrostriatal pathway [23].

- Noradrenergic system activates and facilitates cerebral blood flow, metabolism, and electroencephalographic activity. The system also improves adaptational plasticity, arousal, and vigilance. Noradrenergic dysfunctions are linked with a variety of psychiatric disorders including all forms of stress, addictions, anxiety, and depression [24].

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid-ergic (GABRA) system consists of GABA receptors, GABA transporters , and glutamate decarboxylase which work as an inhibitory neurotransmitter and help in maintaining the normal functions of the central nervous system [27]. Alterations in this system are seen in patients with neurological diseases [28].

- Neurotrophin family of growth factors is a group of proteins responsible for development, survival and function of neurons in central and peripheral nervous systems [29].

2.2.3. Data Preprocessing

2.3. Study Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Susceptibility to Depression

3.2. Inherited Predisposition to Anxiety

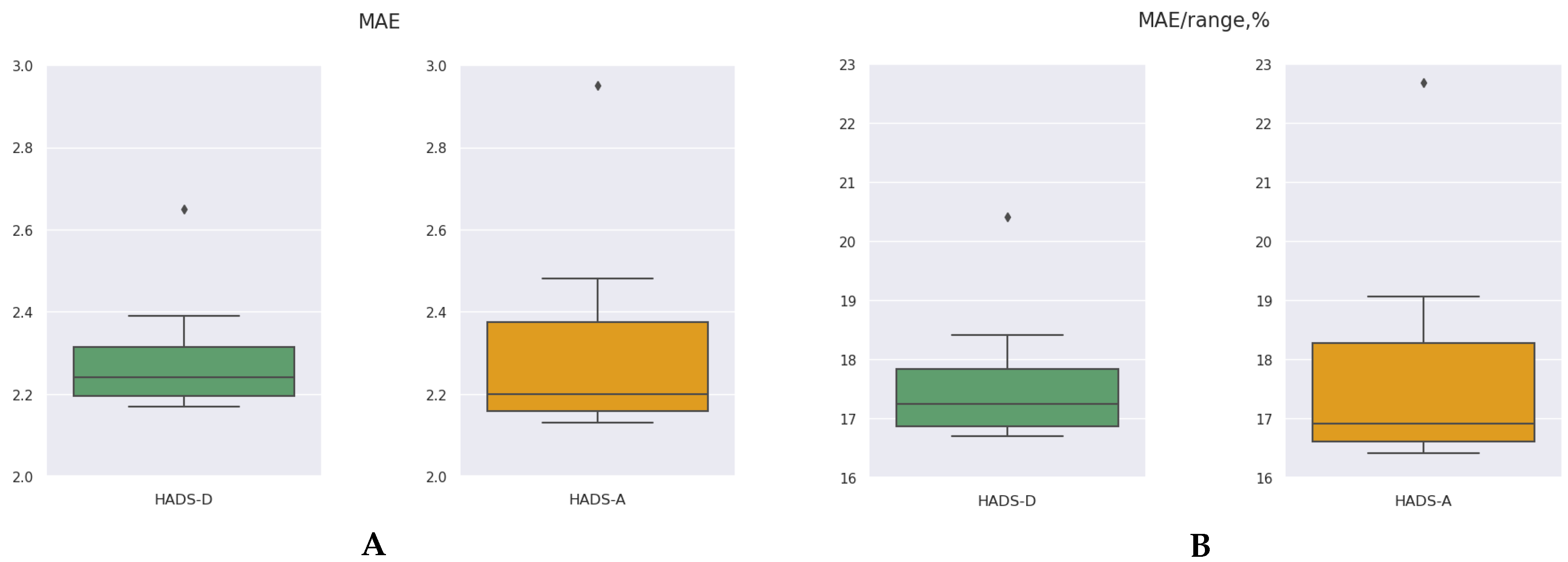

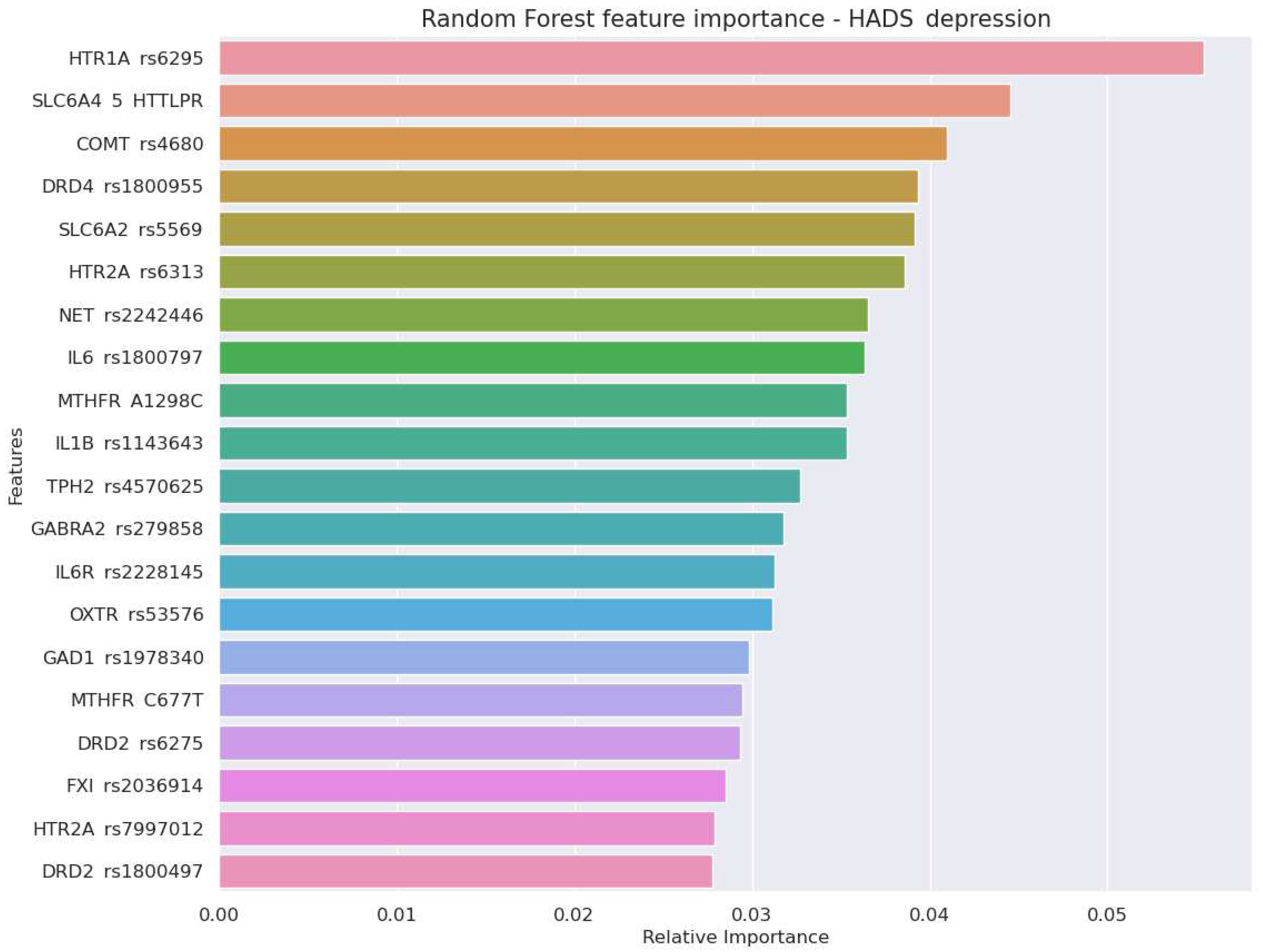

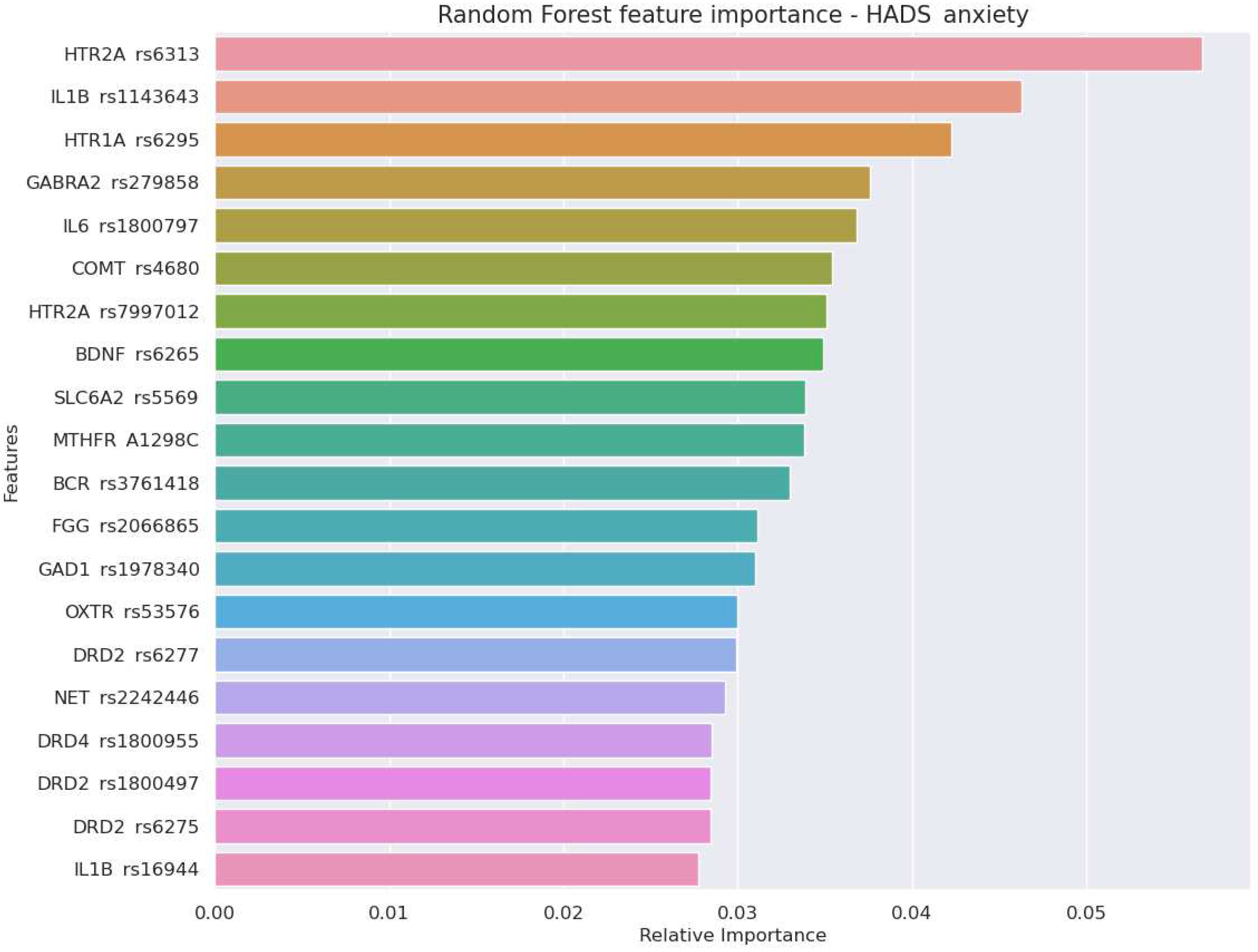

3.3. Prediction of Depression and Anxiety Levels in Sports and Extreme Professions

| Model | HADS-Depression | HADS-Anxiety | p2−4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE (1) | MAE/ROV,% (2) | MAE (3) | MAE/ROV,% (4) | ||

| CatBoost Regressor | 2.26 | 17.37 | 2.18 | 16.76 | |

| Random Forest | 2.22 | 17.1 | 2.15 | 16.55 | |

| LGBM Regressor | 2.25 | 17.28 | 2.23 | 17.17 | |

| Gradient Boosting | 2.66 | 20.44 | 2.97 | 22.85 | |

| XGB Regressor | 2.37 | 18.23 | 2.38 | 18.28 | |

| Theil-Sen Regression | 2.29 | 17.64 | 2.48 | 19.06 | |

| Lasso Regression | 2.18 | 16.75 | 2.15 | 16.57 | |

| Support Vector Regression | 2.17 | 16.7 | 2.17 | 16.68 | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.30±0.18 | 17.69 ±1.35 | 2.32 ±0.27 | 17.86±2.09 | 0.5054 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Role of Genes and Environment in Liability to Stress

4.2. Association between Immune System and Stress-Resistance

4.3. Polygenic Nature of Stress Resistance

Conclusions

- Study findings justified a polygenic nature of stress resistance among people in extreme professions. Elevated levels of anxiety were associated with genes regulating the serotonergic, dopaminergic, GABRA-ergic systems, coagulation, and immune response. A chance of developing depression was higher in the carriers of MTHFR C677T C/T and MTHFR A1298C A/C genotypes.

- We found almost equal performance of ML algorithms predicting scores in HADS-Depression and in HADS-Anxiety subscales (17.69±1.35 vs 17.86±0.27 respectively), although the number of significant genetic associations was higher for HADS-Anxiety.

- Genes encoding serotonergic system - textitHTR1A and HTR2A - were among top three predictors of scores in HADS-D and HADS-A scales. HTR2A rs6313 also provided the greatest odds ratio for the risk of anxiety (OR 4.82,p=0.001). A high perdictive power of the serotonergic genes reflects an important role of serotonin in mood regulation.

- A set of genetic markers of the immune system were top-informative predictors of the HADS-anxiety score (IL1B rs1143643 and rs16944, IL6 rs1800797). The findings justify the importance of considering genetic markers of immune and coagulatory systems while predicting stress resistance in athletes and military employees.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE | angiotensin I converting enzyme |

| ACTN3 | actinin alpha 3 |

| AST | attention study technique |

| BCR | breakpoint cluster region |

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CMD | common mental disorders |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| DARPP-32 | dopamine- and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein with an apparent Mr of 32,000 |

| DRD2 | dopamine receptor |

| FKBP51 | FK506-binding Protein 51 |

| GABRA2 | gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunit alpha 2 |

| HADS | hospital anxiety and depression scale |

| HTR1A | 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 1A |

| HTR2A | 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2A |

| MAE | mean absolute error |

| MAE/ROV | mean absolute error / range of values |

| ML | machine learning |

| MTHFR | methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase |

| NET | norepinephrine transporter |

| SLC6A2 | solute carrier family 6 member 2 |

| SNP | single nucleotie polymorphysm |

| TPH2 | tryptophan hydroxylase-2 |

References

- Akanji, B. Occupational Stress: A Review on Conceptualisations, Causes and Cure. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, B.N.; Fleshner, M. Exercise, stress resistance, and central serotonergic systems. Exercise and sport sciences reviews 2011, 39, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, I.H.; Hom, M.A.; Joiner, T.E. A systematic review of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among police officers, firefighters, EMTs, and paramedics. Clinical psychology review 2016, 44, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junge, A.; Feddermann-Demont, N. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in top-level male and female football players. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2016, 2, e000087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.F.d.A.; Barbosa, L.N.F.; Gomes, P.C.d.S.; Nóbrega, F.A.F. Evaluation of anxiety and depression symptoms among u-20 soccer athletes in recife-pe: A cross-sectional study. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konietzny, K.; Chehadi, O.; Levenig, C.; Kellmann, M.; Kleinert, J.; Mierswa, T.; Hasenbring, M.I. Depression and suicidal ideation in high-performance athletes suffering from low back pain: The role of stress and pain-related thought suppression. European Journal of Pain 2019, 23, 1196–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popovych, I.; Halian, I.; Pavliuk, M.; Kononenko, A.; Hrys, A.; Tkachuk, T. Emotional quotient in the structure of mental burnout of athletes. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouttebarge, V.; Aoki, H.; Kerkhoffs, G. Symptoms of common mental disorders and adverse health behaviours in male professional soccer players. Journal of Human Kinetics 2015, 49, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouttebarge, V.; Aoki, H.; Ekstrand, J.; Verhagen, E.A.; Kerkhoffs, G.M. Are severe musculoskeletal injuries associated with symptoms of common mental disorders among male European professional footballers? Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy 2016, 24, 3934–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Mackinnon, A.; Batterham, P.J.; Stanimirovic, R. The mental health of Australian elite athletes. Journal of science and medicine in sport 2015, 18, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foskett, R.; Longstaff, F. The mental health of elite athletes in the United Kingdom. Journal of science and medicine in sport 2018, 21, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radloff, L.S. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of youth and adolescence 1991, 20, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, S.; Archambeau, O.G.; Deliramich, A.N.; Kim, B.S.; Chiu, P.H.; Frueh, B.C. Depressive symptoms and mental health treatment in an ethnoracially diverse college student sample. Journal of American College Health 2011, 59, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouttebarge, V.; Backx, F.J.; Aoki, H.; Kerkhoffs, G.M. Symptoms of common mental disorders in professional football (soccer) across five European countries. Journal of sports science & medicine 2015, 14, 811. [Google Scholar]

- Gnall, K.E.; Sacco, S.J.; Park, C.L.; Mazure, C.M.; Hoff, R.A. Life meaning and mental health in post-9/11 veterans: The mediating role of perceived stress. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.J.; Morrow, C.E.; Etienne, N.; Ray-Sannerud, B. Guilt, shame, and suicidal ideation in a military outpatient clinical sample. Depression and anxiety 2013, 30, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uher, R. Gene–environment interactions in common mental disorders: An update and strategy for a genome-wide search. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology 2014, 49, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klengel, T.; Binder, E.B. Epigenetics of stress-related psychiatric disorders and gene× environment interactions. Neuron 2015, 86, 1343–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, S.M.; Reid, M.W. Gene-environment interactions in depression research: Genetic polymorphisms and life-stress polyprocedures. Psychological Science 2008, 19, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokhin, A.P. Genetic psychophysiology: Advances, problems, and future directions. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2014, 93, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, A.F. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Occupational medicine 2014, 64, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, J.J. Role of the serotonergic system in the pathogenesis of major depression and suicidal behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 1999, 21, 99S–105S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.D.; Zald, D.H.; Felger, J.C.; Christman, S.; Claassen, D.O.; Horga, G.; Miller, J.M.; Gifford, K.; Rogers, B.; Szymkowicz, S.M.; et al. Influences of dopaminergic system dysfunction on late-life depression. Molecular psychiatry 2022, 27, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, M.; Panzer, A. The central noradrenergic system: An overview. African Journal of Psychiatry 2007, 10, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumsta, R.; Heinrichs, M. Oxytocin, stress and social behavior: Neurogenetics of the human oxytocin system. Current opinion in neurobiology 2013, 23, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Domes, G.; Kirsch, P.; Heinrichs, M. Oxytocin and vasopressin in the human brain: Social neuropeptides for translational medicine. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2011, 12, 524–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, M. The role of the GABA system in amphetamine-type stimulant use disorders. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2015, 9, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garret, M.; Du, Z.; Chazalon, M.; Cho, Y.H.; Baufreton, J. Alteration of GABA ergic neurotransmission in Huntington’s disease. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics 2018, 24, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaper, S.D. The neurotrophin family of neurotrophic factors: An overview. Neurotrophic factors: Methods and protocols 2012, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, V.; Gleeson, M.; Williams, N.; Clancy, R. Clinical investigation of athletes with persistent fatigue and/or recurrent infections. British journal of sports medicine 2004, 38, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, M. Immune system adaptation in elite athletes. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care 2006, 9, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, G.; Whiteside, W.K.; Kanwisher, M. Venous thrombosis in athletes. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2013, 21, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, R.; Ingerslev, J.; Sørensen, B. Muscle bleeds in professional athletes–diagnosis, classification, treatment and potential impact in patients with haemophilia. Haemophilia 2010, 16, 858–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, J.; Moll, S. Athletes and blood clots: Individualized, intermittent anticoagulation management. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2017, 15, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklearn. Preprocessing. 2023. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.preprocessing.LabelEncoder.html (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Intermediate Linear Regressions and Logistic Regressions. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/FraManl/DataCamp/blob/main/Intermediate%20Regression%20with%20statsmodels%20in%20Python.ipynb (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Statsmodels - categorical encoding. 2023. Available online: https://www.statsmodels.org/dev/examples/notebooks/generated/contrasts.html (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Perform a Fisher exact test on a 2x2 contingency table. 2023. Available online: https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/generated/scipy.stats.fisher_exact.html (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Bind, M.A.; Rubin, D. When possible, report a Fisher-exact P value and display its underlying null randomization distribution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 19151–19158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Jabeur, S.; Gharib, C.; Mefteh-Wali, S.; Ben Arfi, W. CatBoost model and artificial intelligence techniques for corporate failure prediction. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2021, 166, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, Q.; Yu, B. LightGBM-PPI: Predicting protein-protein interactions through LightGBM with multi-information fusion. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2019, 191, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yin, Y.; Quan, X.; Zhang, H. Gene Expression Value Prediction Based on XGBoost Algorithm. National Library of Medicine 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mean decrease in impurity feature importance. 2023. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/ensemble.html#random-forest-feature-importance (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Kandler, C.C.E.; Lam, M.S.T. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase screening in treatment-resistant depression. Federal Practitioner 2019, 36, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Kropotov, J.D. Functional neuromarkers for psychiatry: Applications for diagnosis and treatment; Academic Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge, R.; Young, A.H.; Cleare, A.J. Biomarkers for depression: Recent insights, current challenges and future prospects. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment 2017, 1245–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, A.; Cattane, N.; Begni, V.; Pariante, C.; Riva, M. The human BDNF gene: Peripheral gene expression and protein levels as biomarkers for psychiatric disorders. Translational psychiatry 2016, 6, e958–e958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reardon, C.L.; Hainline, B.; Aron, C.M.; Baron, D.; Baum, A.L.; Bindra, A.; Budgett, R.; Campriani, N.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Currie, A.; et al. Mental health in elite athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement (2019). British journal of sports medicine 2019, 53, 667–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mountjoy, M.; Brackenridge, C.; Arrington, M.; Blauwet, C.; Carska-Sheppard, A.; Fasting, K.; Kirby, S.; Leahy, T.; Marks, S.; Martin, K.; et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement: Harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016, 50, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tranæus, U.; Ivarsson, A.; Johnson, U. Stress and injuries in elite sport. Handbuch Stressregulation und Sport, 2018; 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foong, P.L.C.; Kwan, R.W.S.; et al. Understanding mental health in Malaysian elite sports: A qualitative approach. Malaysian Journal of Movement, Health & Exercise 2021, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, A.; Yoder, L. Military resilience: A concept analysis. In Nursing forum; Wiley Online Library, 2013; Volume 48, pp. 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, B.E. The concept of depression as a dysfunction of the immune system. In Depression: From psychopathology to pharmacotherapy; Karger Publishers, 2010; Volume 27, pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, S.; Chugh, G.; Asghar, M. Inflammation in anxiety. Advances in protein chemistry and structural biology 2012, 88, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, D.; Eszlari, N.; Petschner, P.; Pap, D.; Vas, S.; Kovacs, P.; Gonda, X.; Juhasz, G.; Bagdy, G. Effects of IL1B single nucleotide polymorphisms on depressive and anxiety symptoms are determined by severity and type of life stress. Brain, behavior, and immunity 2016, 56, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guardado, P.; Olivera, A.; Rusch, H.L.; Roy, M.; Martin, C.; Lejbman, N.; Lee, H.; Gill, J.M. Altered gene expression of the innate immune, neuroendocrine, and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) systems is associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in military personnel. Journal of anxiety disorders 2016, 38, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohrt, B.A.; Worthman, C.M.; Adhikari, R.P.; Luitel, N.P.; Arevalo, J.M.; Ma, J.; McCreath, H.; Seeman, T.E.; Crimmins, E.M.; Cole, S.W. Psychological resilience and the gene regulatory impact of posttraumatic stress in Nepali child soldiers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 8156–8161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodney, T.; Taylor, P.; Dunbar, K.; Perrin, N.; Lai, C.; Roy, M.; Gill, J. High IL-6 in military personnel relates to multiple traumatic brain injuries and post-traumatic stress disorder. Behavioural brain research 2020, 392, 112715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milaneschi, Y.; Kappelmann, N.; Ye, Z.; Lamers, F.; Moser, S.; Jones, P.B.; Burgess, S.; Penninx, B.W.; Khandaker, G.M. Association of inflammation with depression and anxiety: Evidence for symptom-specificity and potential causality from UK Biobank and NESDA cohorts. Molecular Psychiatry 2021, 26, 7393–7402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brydon, L.; Edwards, S.; Jia, H.; Mohamed-Ali, V.; Zachary, I.; Martin, J.F.; Steptoe, A. Psychological stress activates interleukin-1β gene expression in human mononuclear cells. Brain, behavior, and immunity 2005, 19, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rietschel, L.; Zhu, G.; Kirschbaum, C.; Strohmaier, J.; Wüst, S.; Rietschel, M.; Martin, N.G. Perceived stress has genetic influences distinct from neuroticism and depression. Behavior genetics 2014, 44, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkosis, A.G.; Tsirka, S.E. Neuroimmune mechanisms and sex/gender-dependent effects in the pathophysiology of mental disorders. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2020, 375, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.W.; Ramachandran, S. Missing compared to what? Revisiting heritability, genes and culture. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2018, 373, 20170064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, W.; Penke, L.; Spinath, F.M. Heritability in the era of molecular genetics: Some thoughts for understanding genetic influences on behavioural traits. European Journal of Personality 2011, 25, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokhin, I.O.; Khorkova, O.; Saveanu, R.V.; Wahlestedt, C. Molecular mechanisms of psychiatric diseases. Neurobiology of disease 2020, 146, 105136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Bao, Y.; He, S.; Wang, G.; Guan, Y.; Ma, D.; Wang, P.; Huang, X.; Tao, S.; Zhang, D.; et al. The association between genetic variants in the dopaminergic system and posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2016, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosák, L. Role of the COMT gene Val158Met polymorphism in mental disorders: A review. European Psychiatry 2007, 22, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatt, J.M.; Burton, K.L.; Williams, L.M.; Schofield, P.R. Specific and common genes implicated across major mental disorders: A review of meta-analysis studies. Journal of psychiatric research 2015, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapić, M.; Pivac, N.; Kozarić-Kovačić, D.; Deželjin, M.; Cubells, J.F.; Mück-Šeler, D. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) activity and-1021C/T polymorphism of DBH gene in combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics 2007, 144, 1087–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambouris, M.; Ntalouka, F.; Ziogas, G.; Maffulli, N. Predictive genomics DNA profiling for athletic performance. Recent Patents on DNA & Gene Sequences (Discontinued) 2012, 6, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommers, L.G.; Richter, J.; Yang, Y.; Raab, A.; Baumann, C.; Lang, K.; Schiele, M.A.; Weber, H.; Wittmann, A.; Wolf, C.; et al. A functional genetic variation of SLC6A2 repressor hsa-miR-579-3p upregulates sympathetic noradrenergic processes of fear and anxiety. Translational psychiatry 2018, 8, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.K.; Hwang, J.A.; Lee, H.J.; Yoon, H.K.; Ko, Y.H.; Lee, B.H.; Jung, H.Y.; Hahn, S.W.; Na, K.S. Association between norepinephrine transporter gene (SLC6A2) polymorphisms and suicide in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of affective disorders 2014, 158, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genetic variant | Allele | HADS-D | HADS-A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI, 95% | p-value | OR | CI, 95% | p-value | ||

| SEROTONERGIC SYSTEM | |||||||

| SLC6A4 5-HTTLPR | L/L | 1.36 | [0.53, 3.51] | 0.64 | 1.06 | [0.45, 2.51] | 0.99 |

| L/S | 0.60 | [0.21, 1.72] | 0.46 | 1.14 | [0.48, 2.72] | 0.82 | |

| S/S | 1.29 | [0.37, 4.53] | 0.72 | 0.62 | [0.14, 2.70] | 0.75 | |

| HTR2A rs6313 | C/T | 1.34 | [0.52, 3.47] | 0.64 | 0.39 | [0.15, 0.98] | 0.05 |

| C/C | 0.78 | [0.29, 2.13] | 0.81 | 0.91 | [0.37, 2.23] | 0.99 | |

| T/T | 0.99 | [0.19, 3.72] | 0.72 | 4.82 | [1.97, 11.78] | 0.001 | |

| HTR2A rs7997012 | A/G | 0.69 | [0.25, 1.89] | 0.63 | 0.81 | [0.33, 1.99] | 0.82 |

| A/A | 1.01 | [0.37, 2.75] | 0.99 | 1.45 | [0.60, 3.50] | 0.48 | |

| G/G | 1.46 | [0.55, 3.85] | 0.44 | 0.85 | [0.32, 2.23] | 0.81 | |

| HTR1A rs6295 | C/G | 0.92 | [0.35, 2.40] | 0.99 | 0.81 | [0.33, 1.95] | 0.67 |

| C/C | 1.46 | [0.55, 3.86] | 0.44 | 1.33 | [0.54, 3.28] | 0.63 | |

| G/G | 0.71 | [0.23, 2.21] | 0.79 | 0.96 | [0.36, 2.52] | 0.99 | |

| DOPAMINERGIC SYSTEM | |||||||

| COMT rs4680 | A/G | 0.83 | [,0.32 2.17] | 0.81 | 1.83 | [0.71, 4.70] | 0.27 |

| A/A | 0.42 | [0.09, 1.86] | 0.38 | 0.15 | [0.02, 1.17] | 0.04 | |

| G/G | 2.22 | [0.83, 5.91] | 0.15 | 1.28 | [0.48, 3.41] | 0.60 | |

| COMT rs165599 | A/G | 0.52 | [0.2, 1.38] | 0.24 | 0.58 | [0.24, 1.39] | 0.28 |

| A/A | 1.42 | [0.56, 3.63] | 0.47 | 1.46 | [0.62, 3.44] | 0.38 | |

| G/G | 2 | [0.57, 7.02] | 0.40 | 1.57 | [0.46, 5.42] | 0.45 | |

| DARPP-32 PPP1R rs3764352 |

T/T | 0.73 | [0.27, 2.01] | 0.63 | 0.90 | [0.35, 2.29] | 0.83 |

| C/C | 1.19 | [0.26, 5.5] | 0.69 | 0.43 | [0.06, 3.35] | 0.70 | |

| C/T | 1.3 | [0.47, 3.58] | 0.63 | 1.39 | [0.55, 3.53] | 0.50 | |

| DARPP-32 PPP1R rs879606 |

G/G | 0.74 | [0.25, 2.19] | 0.62 | 1.29 | [0.45, 3.7] | 0.66 |

| A/A | 0.99 | [0.12, 8.01] | 0.99 | 0.33 | [0.02, 5.78] | 0.45 | |

| A/G | 1.37 | [0.46, 4.09] | 0.61 | 1.01 | [0.36, 2.85] | 0.99 | |

| DARPP-32 PPP1R rs907094 |

A/A | 0.89 | [0.35, 2.27] | 0.82 | 1.06 | [0.45, 2.5] | 0.99 |

| A/G | 1.1 | [0.42, 2.87] | 0.81 | 1.22 | [0.51, 2.92] | 0.65 | |

| G/G | 1.08 | [0.25, 4.74] | 0.99 | 0.39 | [0.05, 2.95] | 0.71 | |

| DBH rs1108580 | A/G | 1.07 | [0.41, 2.74] | 0.99 | 0.9 | [0.38, 2.16] | 0.83 |

| A/A | 1.31 | [0.48, 3.58] | 0.60 | 0.56 | [0.18, 1.7] | 0.46 | |

| G/G | 0.68 | [0.22, 2.13] | 0.60 | 1.78 | [0.73, 4.3] | 0.22 | |

| DBH rs1611115 | C/C | 1.35 | [0.5, 3.67] | 0.63 | 2.34 | [0.84, 6.52] | 0.12 |

| C/T | 0.38 | [0.11, 1.33] | 0.13 | 0.57 | [0.21, 1.57] | 0.35 | |

| T/T | 3.35 | [0.96, 11.68] | 0.10 | 0.29 | [0.017, 5] | 0.39 | |

| DRD2 rs1800497 | C/C | 1.59 | [0.51, 4.96] | 0.60 | 0.34 | [0.14, 0.81] | 0.02 |

| C/T | 0.72 | [0.24, 2.22] | 0.79 | 3.44 | [1.48, 8] | 0.01 | |

| T/T | 0.82 | [0.04, 14.82] | 0.89 | 0.67 | [0.04, 12.02] | 0.78 | |

| DRD2 rs6277 | A/G | 0.97 | [0.38, 2.5] | 0.99 | 0.99 | [0.41, 2.36] | 0.99 |

| A/A | 1.93 | [0.74, 5.01] | 0.19 | 0.88 | [0.33, 2.32] | 0.99 | |

| G/G | 0.36 | [0.08, 1.61] | 0.26 | 1.17 | [0.44, 3.08] | 0.8 | |

| DRD2 rs6275 | G/G | 1.55 | [0.59, 4.13] | 0.48 | 1.22 | [0.5, 2.97] | 0.67 |

| A/A | 0.59 | [0.13, 2.63] | 0.75 | 1.09 | [0.35, 3.38] | 0.77 | |

| A/G | 0.81 | [0.29, 2.26] | 0.81 | 0.76 | [0.18, 3.42] | 0.99 | |

| DRD4 rs1800955 | C/T | 2.04 | [0.76, 5.43] | 0.16 | 0.57 | [0.23, 1.43] | 0.28 |

| C/C | 1.13 | [0.39, 3.26] | 0.79 | 0.45 | [0.55, 3.6] | 0.45 | |

| T/T | 0.27 | [0.06, 1.21] | 0.11 | 1.36 | [0.21, 3.37] | 0.48 | |

| NORADRENERGIC SYSTEM | |||||||

| NET rs2242446 | T/T | 10.8 | [0.29, 2.17] | 0.64 | 0.55 | [0.21, 1.43] | 0.19 |

| C/C | 0.51 | [0.07, 4.00] | 0.99 | 1.49 | [0.41, 5.43] | 0.47 | |

| C/T | 1.52 | [0.56, 4.13] | 0.46 | 1.57 | [0.62, 3.98] | 0.37 | |

| SLC6A2 rs5569 | G/G | 1.14 | [0.43, 3.03] | 0.82 | 0.92 | [0.37, 2.28] | 0.99 |

| A/A | 1.20 | [0.33, 4.36] | 0.73 | 0.95 | [0.27, 3.36] | 0.99 | |

| A/G | 0.78 | [0.28, 2.21] | 0.81 | 1.12 | [0.45, 2.8] | 0.82 | |

| OXYTOCINERGIC SYSTEM | |||||||

| OXTR rs53576 | A/G | 0.42 | [0.14, 1.27] | 0.15 | 0.52 | [0.2, 1.38] | 0.19 |

| A/A | 1.99 | [0.62, 6.39] | 0.27 | 0.65 | [0.14, 2.89] | 0.75 | |

| G/G | 1.51 | [0.56, 4.03] | 0.47 | 2.19 | [0.87, 5.52] | 0.08 | |

| GAMMA-AMINOBUTYRIC ACID-ERGIC SYSTEM | |||||||

| GABRA2 rs279858 | C/T | 0.5 | [0.18, 1.39] | 0.23 | 0.37 | [0.14, 1] | 0.05 |

| C/C | 1.68 | [0.57, 4.91] | 0.36 | 2.68 | [1.07, 6.74] | 0.04 | |

| T/T | 1.39 | [0.53, 3.68] | 0.62 | 1.22 | [0.49, 3.03] | 0.65 | |

| GAD1 rs1978340 | G/G | 0.81 | [0.3, 2.18] | 0.81 | 0.7 | [0.28, 1.77] | 0.51 |

| A/A | 1.25 | [0.34, 4.52] | 0.73 | 0.6 | [0.13, 2.68] | 0.75 | |

| A/G | 1.11 | [0.41, 2.98] | 0.81 | 1.74 | [0.71, 4.27] | 0.28 | |

| GAD1 rs3749034 | G/G | 0.86 | [0.31, 2.43] | 0.81 | 0.7 | [0.26, 1.87] | 0.51 |

| A/A | 0.75 | [0.09, 5.92] | 0.99 | 3.41 | [1.02, 11.4] | 0.06 | |

| A/G | 1.25 | [0.44, 3.54] | 0.63 | 0.89 | [0.32, 2.48] | 0.89 | |

| NEUROTROPHIN FAMILY OF GROWTH FACTORS | |||||||

| BDNF rs6265 | C/C | 0.85 | [0.32, 2.23] | 0.8 | 0.62 | [0.26, 1.48] | 0.35 |

| C/T | 0.72 | [0.24, 2.22] | 0.79 | 1.9 | [0.8, 4.5] | 0.21 | |

| T/T | 2.88 | [0.82, 10.03] | 0.13 | 0.6 | [0.08, 4.49] | 0.99 | |

| TPH2 rs4570625 | G/G | 1.24 | [0.47, 3.27] | 0.81 | 1.38 | [0.56, 3.37] | 0.52 |

| G/T | 0.99 | [0.38, 2.58] | 0.99 | 0.72 | [0.29, 1.81] | 0.65 | |

| T/T | 0.48 | [0.03, 8.4] | 0.61 | 0.95 | [0.13, 7.13] | 0.99 | |

| Genetic variant | Allele | HADS-D | HADS-A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI, 95% | p-value | OR | CI, 95% | p-value | ||

| FGG rs2066865 | C/C | 0.94 | [0.34, 2.56] | 0.99 | 0.99 | [0.39, 2.52] | 0.99 |

| C/T | 1.03 | [0.36, 2.93] | 0.99 | 0.78 | [0.28, 2.16] | 0.80 | |

| T/T | 1.18 | [0.16, 8.94] | 0.6 | 2.2 | [0.51, 9.51] | 0.28 | |

| FXI rs2036914 | C/T | 1.87 | [0.64, 5.47] | 0.33 | 3.31 | [1.07, 10.23] | 0.03 |

| C/C | 0.7 | [0.2, 2.48] | 0.77 | 0.16 | [0.02, 1.19] | 0.06 | |

| T/T | 0.51 | [0.11, 2.27] | 0.54 | 0.65 | [0.19, 2.28] | 0.78 | |

| GP6 rs1613662 | A/A | 1.66 | [0.37, 7.46] | 0.75 | 4.51 | [0.59, 34.41] | 0.14 |

| A/G | 0.68 | [0.16, 2.99] | 0.99 | 0.11 | [0.01, 1.89] | 0.13 | |

| G/G | 1.38 | [0.07, 26.5] | 3.61 | 0.33 | [0.48, 26.99] | 0.31 | |

| Genetic variant | Allele | HADS-D | HADS-A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI, 95% | p-value | OR | CI, 95% | p-value | ||

| BCR rs3761418 | A/A | 1.79 | [0.68, 4.69] | 1.34 | 1.1 | [0.47, 2.59] | 0.99 |

| A/G | 0.36 | [0.11, 1.1] | 0.09 | 0.74 | [0.3, 1.8] | 0.66 | |

| G/G | 2.11 | [0.6, 7.38] | 0.22 | 1.66 | [0.48, 5.69] | 0.43 | |

| FKBP5 rs1360780 | C/C | 1.59 | [0.61, 4.18] | 0.48 | 0.44 | [0.17, 1.16] | 0.12 |

| C/T | 0.76 | [0.29, 2] | 0.64 | 2.32 | [0.88, 6.14] | 0.09 | |

| T/T | 0.48 | [0.03, 8.4] | 0.61 | 0.95 | [0.13, 7.14] | 0.99 | |

| IL1B rs1143643 | C/T | 0.69 | [0.26, 1.78] | 0.48 | 1.92 | [0.78, 4.73] | 0.19 |

| C/C | 1.42 | [0.55, 3.66] | 0.46 | 0.37 | [0.12, 1.13] | 0.11 | |

| T/T | 1.09 | [0.31, 3.83] | 0.99 | 1.24 | [0.41, 3.75] | 0.76 | |

| IL1B rs16944 | A/G | 0.94 | [0.35, 2.51] | 0.99 | 0.65 | [0.26, 1.63] | 0.39 |

| A/A | 1.34 | [0.37, 4.89] | 0.72 | 0.13 | [0.01, 2.23] | 0.16 | |

| G/G | 0.92 | [0.34,2.53] | 0.99 | 2.7 | [1.08, 6.77] | 0.03 | |

| IL6 rs1800797 | A/G | 0.89 | [0.34, 2.32] | 0.99 | 1.1 | [0.46, 2.65] | 0.99 |

| A/A | 0.2 | [0.03, 1.54] | 0.14 | 0.16 | [0.02, 1.22] | 0.06 | |

| G/G | 2.3 | [0.89, 5.94] | 0.11 | 1.96 | [0.81, 4.72] | 0.15 | |

| IL6R rs2228145 | A/A | 1.34 | [0.52, 3.45] | 0.64 | 2.34 | [0.93, 5.9] | 0.08 |

| A/C | 0.94 | [0.36, 2.45] | 0.99 | 0.42 | [0.15, 1.16] | 0.12 | |

| C/C | 0.45 | [0.06, 3.4] | 0.7 | 0.79 | [0.18, 3.42] | 0.99 | |

| FOLATE SYSTEM | |||||||

| MTHFR C677T | C/C | 1.52 | [0.58, 3.98] | 0.48 | 1.13 | [0.48, 2.67] | 0.83 |

| C/T | 0.29 | [0.08, 1] | 0.05 | 0.86 | [0.35, 2.1] | 0.83 | |

| T/T | 3.36 | [1.09, 10.35] | 0.06 | 1.05 | [0.24, 4.56] | 0.99 | |

| MTHFR A1298C | A/C | 0.33 | [0.11, 1.02] | 0.05 | 1.23 | [0.52, 2.89] | 0.66 |

| A/A | 2.53 | [0.96, 6.65] | 0.09 | 0.88 | [0.37,2.1] | 0.83 | |

| C/C | 1.09 | [0.31, 3.82] | 0.99 | 0.85 | [0.25, 2.94] | 0.99 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).