1. Introduction

Smartphones have emerged as transformative tools, reshaping personal communication and how we access information. Their omnipresence, especially among adolescents, integrates them seamlessly into daily activities [

1,

2,

3]. These devices are no longer mere communicative gadgets but gateways to myriad of online services, redefining societal norms and youth interactions [

1,

3].

Yet, the advantages that smartphones bring can also be double-edged. The line between constructive and detrimental use becomes ambiguous when individuals can’t modulate their engagement, negatively impacting their social ties, professional life, and overall well-being [

4,

5]. As a result, terminologies such as ‘smartphone addiction (SA)’ and ‘problematic smartphone use (PSU)’ have emerged in academic discourse. The former implies deep-seated dependence, while the latter signifies extreme use without necessarily denoting addiction, although they are frequently used interchangeably [

6].

‘Nomophobia’ further captures the contemporary zeitgeist, highlighting the anxiety of being without a smartphone [

7]. And while the DSM-IV doesn’t recognize ‘smartphone addiction’ as a distinct ailment, its behavioral symptoms align closely with the criteria set for other addictions [

8].

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated smartphone reliance, reinforcing that smartphone are primary tools for remote learning, sustaining social bonds, and indoor entertainment during prolonged confinements [

9] A recurring theme in this discussion is self-regulation. A lack of it, especially in managing smartphone interactions, can cultivate persistent and detrimental habits [

6].

The adolescent phase is marked by profound cognitive, emotional, and social shifts [

10]. Given their still-developing self-control mechanisms, adolescents are particularly susceptible to instant gratifications, often overlooking potential long-term consequences [

11]. In this landscape, smartphones—with their ceaseless notifications and entertainment options—act as potent lures. Excessive indulgence can disrupt vital facets of adolescent growth, including social development, restful sleep, and scholastic performance [

12].

Considering this, comprehending the intricacies of SA in adolescents is paramount. It’s not just about understanding the addiction dynamics in this demographic, but also formulating precise interventions and preventive measures catering to their developmental context [

13]. Consequently, pinpointing the antecedents of SA is pivotal, as discerning these factors is a stepping stone towards reducing its prevalence among adolescents.

1.1. Negative effects of SA

Research highlights the varied consequences of smartphone addiction. A series of recent meta-analysis studies [

6,

14,

15]. revisited previous findings and reported that SA predominantly impacts emotional health more than physical health. Notably, there’s a paucity of research on the physical health impacts compared to emotional health [

1].

Habitual smartphone users often encounter physical challenges. Common issues include ’text neck’ and eye strain. More critical problems involve sleep disruptions and a heightened risk of conditions like obesity, reduced physical fitness, and pain and migraines due to extended sedentary behavior [

16]. A clear link between SA and sleep deprivation was established by Alshobaili and AlYoousefi [

17].

The psychological implications can be even more profound. Constant alerts and an unending desire to remain informed can trigger anxiety. The idealized portrayals on social media can breed feelings of inadequacy, resulting in depression and intensified feelings of isolation [

18,

19]. Harwood et al. [

20] associated SA with depression, while Hartanto & Yang [

21] connected it to anxiety. Furthermore, smartphones can serve as an escape from negative emotions. For instance, anxiety-ridden individuals might become overly reliant on their phones for communication or seek distractions through entertainment, further amplifying problematic usage patterns [

22]. Wu et al. [

23] noted an increase in PSU which was associated with a rise in depressive symptoms and anxiety, subsequently affecting sleep quality.

Distractions from smartphones can lead to fragmented attention, compromised academic results, and even temptations for academic dishonesty due to easy information access [

2]. Several studies, such as those by Goswamee and Banerjee [

1] and Sahin [

24], show that excessive smartphone use and high levels of specific app usage can decrease academic performance and increase procrastination. Yang, Asbury and Griffiths [

22] also observed increased academic anxiety and procrastination among university students with heightened SA.

It’s important to understand the long-term consequences of these habits, especially during adolescence. This period is a critical stage for personal development, and distractions can lead to potential challenges in personal relationships and future career aspirations. Adolescents are especially at risk due to their ongoing development and limited impulse control [

25]. Yet, not all studies view smartphone use as detrimental. Lopez-Fernandez et al. [

26] suggested that regular mobile gamers might not necessarily be more prone to SA.

1.2. Smartphone use in Thailand

Thailand’s smartphone dynamics echo global patterns, but they’re infused with distinct cultural and societal idiosyncrasies. The nation’s swift urban transition and economic surge intermingle with deep-rooted Thai principles that prioritize communal and family connections [

27]. Balancing these age-old cultural values with the temptations of the digital universe presents both potential and challenges for Thailand’s younger generation [

28]. To truly grasp the dimensions of Thai adolescent smartphone habits, it is vital to delve into these interwoven elements.

Emerging studies highlight the profound role smartphones play in the daily lives of Thai youth. Smartphones stand out as the favored device among Thai schoolchildren, with PCs not far behind. In contrast, tablets do not share the same appeal, with infrequent usage patterns [

28]. Delving into the specifics, while students typically access PCs or tablets just 1-2 times a week, an impressive 64% turn to their smartphones daily, underlining their indispensable role [

28].

Recent research by D’souza and Sharma [

29] revealed parity in SA levels between Thai and international students studying in Thailand. In another study, Tangmunkongvorakul et al. [

30] noted that an overwhelming 99.1% of university attendees in Northern Thailand owned a smartphone, and nearly half of these students devoted at least five hours daily to their devices.

Despite the extensive research on adolescent behavior, there remains a noticeable void regarding the Muslim adolescent population in Thailand. Considering Thailand’s diverse cultural tapestry, it is crucial to delve into this specific demographic for a holistic understanding of the matter. To the best of the researchers’ knowledge, this subgroup has yet to be extensively studied.

1.3. Family and SA

Families, pivotal in shaping behavioral and belief trajectories, intertwine individual actions with familial dynamics, as proposed by Bowen’s Family Systems Theory [

31]. This theory paints families as intertwined emotional systems, suggesting that adolescent SA might reflect deeper family interactions rather than isolated events. Central to this theory are two elements: the ‘Differentiation of Self’, indicating how individual autonomy can influence susceptibility to family emotional climates and, consequently, external lures like smartphone overuse [

32] and the ‘Emotional Triangle’ which suggests that intense familial tensions might push adolescents towards smartphones as emotional shields [

33]. Moreover, structural family theory highlights the importance of well-defined family boundaries, effective communication, and encouraging offline interactions as pivotal in fostering balanced digital behaviors among adolescents. For example, a study by Kim et al. [

25] revealed how such positive family dynamics can bolster self-control, which is a critical determinant of SA.

The McMaster Model, rooted in family systems theory, provides a nuanced perspective on family dynamics, highlighting specific structures and transactional patterns associated with family challenges [

34,

35,

36]. While it does not encompass all dimensions of family functioning, the model delineates six critical areas: problem-solving, communication, family roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, and behavior control [

35]. A study conducted in Thailand further refined this by introducing a measurement of family functionality, comprising five distinct dimensions: discipline, communication and problem-solving, relationship, emotional status, and family support [

36].

Combining insights from Bowen’s Family Systems Theory, Structural Family Theory, and the McMaster Model offers a comprehensive approach to understanding SA in adolescents. This integration highlights the dynamic relationship between family influences and individual addictive tendencies, emphasizing the need for a thorough exploration of family environments and their functionality. Such an approach is crucial for effectively addressing the multifaceted nature of SA in youth.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research design and participants

The study’s design was cross-sectional. A total of 825 students from six private Islamic schools in three provinces of Southern Thailand was enrolled in the study using a purposive sampling method. The inclusion criteria were Thai Muslim students in junior and senior schools, aged 12 to 20 (Grades 7 to 12), who were currently attending school and using a smartphone. These eligible students voluntarily participated in the study by completing a set of paper-based questionnaires.

2.2. Research Instruments

2.2.1. Socio-demographics and family environments

Participants’ socio-demographic details were gathered using a questionnaire that encompassed attributes like gender, age, grade level, and family environments. This latter category delved into specifics such as parenting status, educational backgrounds of both parents, and the family’s monthly income.

2.2.2. Thai version of Smartphone Addiction Scale–Short version (THAI-SAS-SV)

In this study, the THAI-SAS-SV, formulated by Hanphitakphon and Thawinchai [

37], was used to gauge SA. Adapted from Kwon et al.’s [

38] Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version (SAS-SV), this tool features specific cut-off scores of 31 for males and 33 for females. It contains 10 items rated on a 6-point Likert scale, from Strongly Disagree=1 to Strongly Agree=6, with higher scores indicating increased SA. The scale showcased commendable reliability, reflected by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.780.

2.2.3. Family State and Functioning Assessment Scale in Thai (FSFAS-25)

The FSFAS-25 [

36], an amalgamation of elements from the Family Assessment Device within the McMaster Model of Family Functioning, Chulalongkorn Family Inventory, and the Thai Family Functional Scale, offers an in-depth evaluation of family functioning. It encompasses five crucial dimensions: discipline, communication and problem-solving, relationship, emotional status, and family support. The 25-item scale uses a 4-point Likert response system, ranging from Strongly Disagree=1 to Strongly Agree=4, accommodating both positive and reversed-scored negative statements. A cumulative score between 25 and 100 is obtained, where a higher score is indicative of superior family functionality. With Cronbach’s alpha of 0.844, the tool boasts commendable reliability.

2.3. Data collection

Participants were given an informed consent form to sign after understanding the study’s purpose and the assurance of their response confidentiality.The study commenced with an official request for approval sent to six selected secondary schools in three southern provinces of Thailand. Participants in this research included students spanning from Grade 7 to Grade 12. Within each school, a facilitator assisted the principal researcher in entering classrooms, distributing informed consent forms, and collecting data during designated break times. Respondents were informed that their responses would be kept confidential and analyzed anonymously, with no impact on their personal lives. In this selection, two schools were chosen from each of the three provinces. Once respondents agreed to take part in the survey, they proceeded to complete the questionnaire. It took approximately 30 min to complete the set of questionnaires. IBM SPSS Statistics 29 for descriptive statistics and factor analysis and IBM AMOS 25 was adopted for structural equation modeling (SEM).

2.4. Statistical analysis

First, the study used statistics including frequencies on all the variables in a sample of 825 participants. Second, to investigate the relationships between socio-demographic and family background factors and SA, a series of t-tests and one-way ANOVA were conducted. Following these tests, post-hoc analyses using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (Tukey HSD) tests were performed to further explore specific differences identified in the ANOVA. Third, a factor analysis was conducted in both family functioning and SA. The underlying mechanisms of the two variables were investigated through principal axis factoring with the promax rotation method. Finally, to identify family functioning factors that influence SA, SEM was conducted.

3. Results

3.1. General characteristics including family environment

Table 1 presents the results of general characteristics of the participants including family environment factors. The majority of the sample were female, constituting 55.7% (n=459), while males made up 43.3% (n=422). On average, participants were 15 years old (M=15.11, SD=1.78), with most in the ninth grade (M=9.35, SD=1.69).

Examining family environments, a significant 77.2% (n=630) were raised in dual-parent homes, while 16.5% lived in single-parent households, including 3.8% (n=31) with only a father and 12.7% with only a mother. Patterns in parental education levels were also observed. Approximately 26.2% (n=205) of fathers and 20.0% (n=156) of mothers completed primary school as their highest level of education. Furthermore, a notable 75.8% (n=663) of fathers and 71% (n=554) of mothers had secondary school education or below as their highest academic achievement. This data indicates a slight linear pattern in the educational attainment of the participants’ parents. Concerning family income, 67.9%(n=541) reported monthly earning below 11,000 Baht. Furthermore, 55.2% (n=440) reported monthly earnings below 9,000 Baht, while 22.1% (n=168) had incomes exceeding 15,000 Baht.

3.2. The Prevalence of SA and family environment factors differing in SA

Within the vast realm of smartphone usage, the data from 825 Muslim adolescents reveals a compelling narrative on addiction. A substantial 70.30% (n=580) of the participants reported addiction scores surpassing established benchmarks. Delving deeper, certain socio-demographic and familial markers stand out in their influence (see

Table 1).

There was a significant effect of grade on SA at the p<.05 level for three conditions [F(5, 819)=2.958, p<.05]. Post hoc comparisons using Tukey HSD tests indicated Grade 7 students (M=38.66, SD=8.528) exhibited notably higher addiction scores compared to their Grade 8 counterparts (M=35.14, SD=8.787). The findings suggest that students recently transitioning to junior high school face heightened SA risks, potentially due to adjustments in a new academic environment. Nonetheless, some grade levels did not exhibit a clear influence on addiction tendencies.

The data also revealed a marked relationship between a father’s education and SA [F(7,775)=4.665, p<.001]. Specifically, children of fathers with a Ph.D. exhibited the lowest addiction scores (M=28.94, SD=8.062) compared to those with lesser educational qualifications A similar pattern was observed with mother’s educational level [F(7,772)=3.833, p<.001]. Mothers with a Ph.D. qualification had children with lower addiction scores (M=31.75, SD=8.226) than those of lesser-educated mothers. Notably, it appears that only the highest educational qualifications (e.g., Ph.D.) exhibit protective effects against SA, with mid-level qualifications not showing significant differences.

A significant association between family monthly income and SA was observed [F(5,792)=2.463, p<.05]. Muslim adolescents from families earning over 15,000 Baht monthly had reduced addiction scores (M=35.10, SD=8.733) than those from families earning between 7,001~9,000 Baht (M=37.98, SD=7.892). This suggested that higher family income may offer some protection against SA. However, mid-income levels do not seem to significantly influence addiction rates.

3.3. Family functioning factors predicting SA

3.3.1. Factor analysis for the measurements

To unravel the underlying mechanisms linking family functioning and SA, a four-step Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis was conducted in this study. The construct validity of the FSFAS-25 was also examined using a principal axis factoring analysis with Promax rotation. The suitability of the sample size for factor analysis was confirmed by the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of .885 and Bartlett’s sphericity test (p<.001). Factor analysis identified a five-factor structure: ‘Discipline’, ‘Communication and Problem-Solving’, ‘Relationship’, ‘Emotional Status’, and ‘Family Support’ (see

Table 2).

Factor 1, labeled ’Discipline’, was composed of 5 items with factor loadings between 0.476 and 0.837. However, Item 6 was excluded for its lower factor loading, falling below 0.40. Similarly, Factor 2, ’Communication and Problem-Solving’, involved 5 items, with loadings from 0.410 to 0.711, leading to the exclusion of Item 5 due to inadequate loading. Factor 3, ’Relationship’, initially had 4 items, ranging in load values from 0.599 to 0.681, but Items 20 and 21 were removed for their subpar loadings. For Factor 4, ’Family Support’, included 2 items with loadings from 0.651 to 0.717, and here, Item 19 was discarded. Lastly, Factor 5, ’Emotional Status’, it comprised 2 items with loadings from 0.581 to 0.854, but Item 4 was eliminated for the same reason. The factors identified in the study were named according to the sub-factors of the original scale. To validate these factors, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted. The results demonstrated that the measurement model was a good fit for the data, as indicated by the following statistics: χ2(142) = 478,194, p < .001, CFI = .919, TLI = .903, and RMSEA = .054 (.048; .059). They accounted for 52.3% of the total variance. Furthermore, the scale’s internal consistency was confirmed to be strong, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.816 across 19 items.

The construct validity of the THAI-SAS-SV was also assessed using a principal axis factoring analysis with Promax rotation. The suitability of the sample size for factor analysis was confirmed by the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of .808 and Bartlett’s sphericity test (p<.001). The factor analysis revealed a two-factor structure (See

Table 3).

Factor 1, labeled as ‘Smartphone Dependence’ by the authors, consisted of 6 items with load values ranging from 0.445 to 0.742. Item 10 was discarded due to the lower factor loading (below .40). Factor 2, denoted as ‘Emotional and Physical Problem’, comprised 3 items with load values ranging from 0.421 to 0.799. To assess the validity of a one-factor congeneric model, confirmatory factor analysis was undertaken. The analysis indicated that the measurement model fit the data well, as evidenced by the following statistics: χ2(26) = 157.190, p < .001, CFI = .920, TLI = .889, and RMSEA = .054 (.048; .059). This structure explained 49.2% of the total variance, and the internal consistency of the scale was 0.759 with 9 items.

3.3.2. Preliminary analyses

Table 4 in the study delineates a detailed statistical overview, providing the means and standard deviations (SD), alongside a comprehensive analysis of Pearson correlations between the variables linked to SA, inclusive of its subdivided factors, and the broader spectrum of family functioning, which itself is broken down into five distinct sub-factors. Notably, the analysis yielded significant negative inter-correlations between SA—more specifically, the identified sub-factors of addiction—and the ’Emotional Status’ component of family functioning.

In addition, a noteworthy negative correlation was established between the ’Discipline’ aspect of family functioning and the ’Smartphone Dependence’ sub-factor of SA, indicating that stronger familial discipline is associated with lower levels of dependence on smartphones. However, when examining the other elements of family functioning, such as communication and problem-solving, relationship quality, and family support, the study did not find these to be significantly correlated with the sub-factors of SA, pointing to a more complex and perhaps indirect relationship that warrants further investigation.

3.3.3. Testing to determine family functioning factors influencing SA

The study tested an initial model examining the relationship between five family functioning factors and SA. The results indicated that the model provided a good fit to the data, as evidenced by several fit indices: χ2(174) = 525.640, p < .001, CFI = .918, TLI = .901, and RMSEA = .050 (.045; .054).

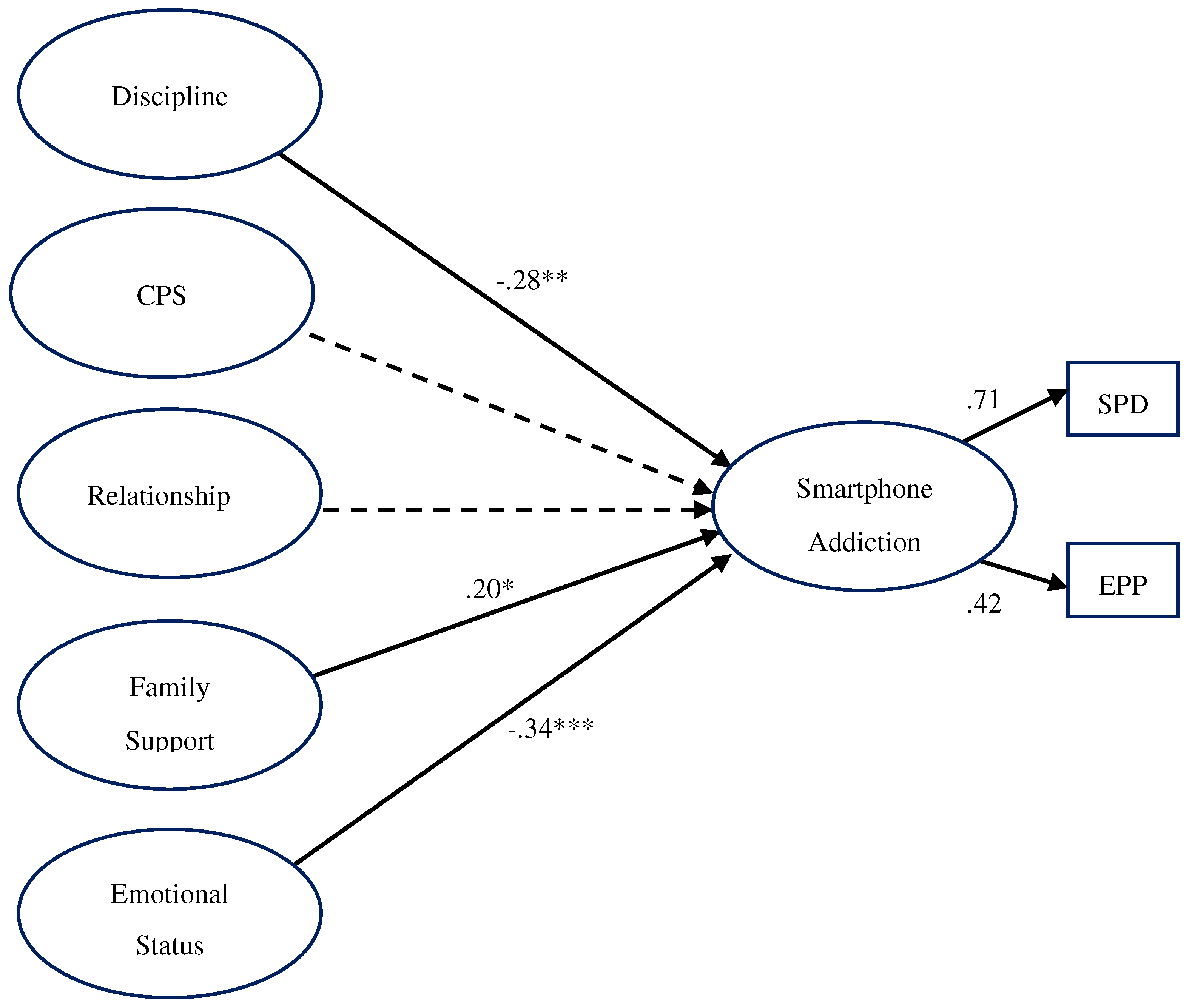

Figure 1 presents the standardized parameter estimates of the structural paths, mapping from exogenous to endogenous variables, in the final model.

The structural path of the final model indicates several significant relationships. The study revealed that ‘Emotional Status’ significantly and negatively predicted SA; at the level of β = -.34, p < .001. ‘Discipline’ also had a significant and negative prediction on SA, β = -.28, p = .002. Strangely, ‘Family Support’ reported the significant and positive prediction on SA, β = .20, p < .05 respectively.

The results suggested that Muslim students whose families presented better discipline and emotional status would be at the lower level of SA. The adolescent Muslim students who were more supported by their families would be exposed to a higher risk of addictive smartphone use.

4. Discussion

This study underscores a pronounced prevalence of SA among Thai Muslim students, with a staggering 70% exhibiting signs. Such a figure contrasts sharply with findings from other Asian nations. In India, addiction rates fluctuate between 39% and 67% [

2,

39]. Similarly, only 21.3% of Chinese undergraduates [

40], 11.4% of Indonesian junior high students [

41], and 35.2% of South Korean adolescents [

42]were reported as addicted. A recent study also pinpointed a 62.6% addiction rate among Filipino adolescents [

43]. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that even within Thailand, there is a stark contrast between different demographics. A recent study by Chinwon et al. [

28] reported a 49% rate of SA among undergraduates in Northern Thailand. Given this stark disparity, a deeper exploration is needed to discern the factors uniquely contributing to the heightened addiction rates among Thai Muslim students.

The influence of family environments, particularly in terms of parental education on SA is evident from the findings of this study. A noteworthy observation is the distinct association between parents’ educational levels and their children’s smartphone engagement patterns. Specifically, Thai adolescents with parents who attained lower educational qualifications tend to manifest heightened smartphone use [

30]. Such a trend suggests that parental awareness, stemming from their educational exposure, might have a moderating effect on the screen time habits of their offspring. Additionally, while family financial status does influence adolescent SA, its impact remains ambiguous. For instance, family income did not correlate with SA among Korean junior students [

44].

The findings of this study draw a clear link between family functioning, particularly ‘Emotional Status’ and ‘Discipline’, and SA among adolescents. Bowen’s Family Systems Theory suggests that emotional challenges within families can push individuals, especially young ones, towards external problems [

31,

32,

33]. When teenagers grow up in families marked by intense emotional ties, emotional distance, or unclear family rules, they are more likely to become heavily reliant on smartphones.

The role of parents is pivotal in this equation. A flexible and understanding relationship between parents and their teenage children can serve as a protective barrier against SA [

34,

35,

36]. Specifically, when parents maintain an adaptable bond with their adolescents, especially during the crucial high school years, they can more effectively guide their smartphone habits [

3]. In essence, a balanced family environment with emotional stability and clear boundaries can help prevent excessive smartphone use in teenagers.

These findings are in line with studies from Korea and China, which highlight the positive impact of cohesive family settings on diminishing SA [

44,

45]. Mangialavori et al. [

46] also identify family challenges, such as disengagement and chaos, as prominent risk determinants. Furthermore, a strong parent-child bond has been shown to curb excessive smartphone usage among Chinese teenagers [

47]. Notably, this research presents a unique observation: increased family support was linked to a heightened risk of addiction, a sentiment reinforced by Castaño-Pulgarín et al. [

48].

Moreover, while smartphones can foster family connections, a majority still prioritize virtual interactions over face-to-face family time [

49]. This trend could be due to adolescents’ shifting social dynamics, where peer influence begins overshadowing family guidance, leading them towards online risks [

48]. Additionally, it’s worth noting that for some young adults, SA might be a coping mechanism against a tumultuous family backdrop [

46,

50,

51].

Yet, the role of smartphones is not universally negative. For many, they act as a bridge, fostering family connections, even if some prefer virtual interactions over physical ones [

50]. This dynamic underscore the idea that smartphones can be both a symptom of and a solution to family disconnect. Ultimately, while smartphones can serve as a refuge from family strife, offering confidence or anxiety relief [

46,

50,

51], it is evident that robust family functioning, characterized by time spent together and adaptability, plays a protective role against SA among adolescents [

44].

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implications of the findings

SA has been highlighted because of poor self-regulation, especially among adolescents transitioning from childhood to adulthood [

25]. It is crucial to bolster self-control mechanisms among this demographic, as their multidimensional development is at stake.

This study accentuates the role of family environments, particularly among Thai Muslim students, in predicting smartphone addictive behaviors. Muslim adolescents in Southern Thailand emerge as a high-risk group, especially those with parents of lower educational backgrounds. Such findings underscore the need for targeted educational initiatives and awareness programs to equip parents with strategies to combat this addiction.

Robust family dynamics can act as a safeguard against SA. Previous research, such as the study conducted in South Asia, indicates that positive family functioning can curtail internet addiction among adolescents [

52]. In stark contrast, healthier family dynamics mitigate the risks of addiction and foster improved academic performance. Specifically, adolescents hailing from well-functioning families are four times less likely to succumb to internet addiction than those from dysfunctional families [

52].

These findings should guide policymakers, educators, and parents in formulating strategies to address SA. Emphasizing digital literacy, promoting open parent-child communication, and organizing workshops that highlight the perils and preventive measures against SA become paramount.

5.2. Limitations and recommendations for future research

This research has several limitations. First, this study employed a cross-sectional design, which offers only a snapshot of the phenomenon under investigation. Subsequent studies should consider implementing longitudinal or experimental designs to establish causality and further validate the observed relationships. Second, the research relied on self-reported questionnaires, which can be prone to biases and may not always capture the true depth or breadth of a subject. Future investigations should leverage standardized and validated measures of internet and SA to ensure more reliable results. Third, assessments of family functioning were based solely on adolescents’ self-reports, potentially providing a one-dimensional perspective. A more holistic approach would entail sourcing data from various family members, such as parents and siblings, to provide a multi-faceted understanding. This could also involve the use of additional tools like dysfunctional family measurements. Lastly, the study presented conflicting results, where some family functioning factors were predictive of SA while others, like family support, positively influenced addiction tendencies. Subsequent research should aim to replicate these findings and explore the underlying reasons for such discrepancies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation Y.K. and W.D.; methodology, Y.K. and K.L.; formal analysis, Y.K. and I.R.; investigation, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.K. and W.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received partial support from the Faculty of Liberal Arts Research Fund (No. LA-GS002/2020), Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai Campus.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research at Sirindhorn College of Public Health, Yala (IRB No. SCPHYLIRB-2565/113).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data availability is restricted due to privacy reasons. However, data may be available by writing to the correspondence author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Funding sources were not involved in the study’s design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript composition, or the choice to submit the findings for publication.

References

- Goswamee G.; Banerjee P. A study on smartphone usage among the adolescents and its influence on the academic performance. Psychology and Education Journal 2021, 58(4). Retrieved from http://psychologyandeducation.net/pae/index.php/pae/article/view/5440/4692.

- MP V.; Kamala K. 2021. A Study on Smartphone Addiction among School Children. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology 2021, 19897–19902. Retrieved from https://www.annalsofrscb.ro/index.php/journal/article/view/8788.

- Kaur S.; Bhatt M.; Upadhyay C.; Gurung C.; Rai C.; Varghese CS. A cross sectional study to assess the addiction of smartphone by students attending higher secondary school of urban community, Lucknow. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) 2019, 9(3). [CrossRef]

- Pera A.The psychology of addictive smartphone behavior in young adults: problematic use, social anxiety, and depressive stress. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11:573473. [CrossRef]

- Panova T.; Carbonell X. 2018. Is smartphone addiction really an addiction?. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2018, 7(2), 252-259. [CrossRef]

- Busch PA.; McCarthy S. 2021. Antecedents and consequences of problematic smartphone use: A systematic literature review of an emerging research area. Computers in Human Behavior 2021, 114. 106414. [CrossRef]

- Notara V.; Vagka E.; Gnardellis C.; Lagiou A. The Emerging Phenomenon of Nomophobia in Young Adults: A Systematic Review Study. Addict Health 2021, 13(2), 120-136. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders ( 4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author, 2000.

- Indrasvari M.; Harahap R.; Harahap D. Analysis of the Impact of Smartphone Use on Adolescent Social Interactions During COVID-19. Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan IPA 2021, 7(2), 167-172. [CrossRef]

- Steinberg L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2005, 9(2), 69-74. [CrossRef]

- Somerville LH.; Casey BJ. Developmental neurobiology of cognitive control and motivational systems. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2010, 20(2), 236-241. [CrossRef]

- Twenge, JM.; Campbell WK. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive Medicine Reports 2018, 12, 271-283. [CrossRef]

- Hinnant JB.; O’Brien M. Cognitive and emotional control and perspective taking and their relations to empathy in 5-year-old children. The Journal of Genetic Psychology 2007, 168(3), 301-322. [CrossRef]

- Shahjehan A.; Shah SI.; Qureshi JA.; Wajid A. A meta-analysis of smartphone addiction and behavioral outcomes. International Journal of Management Studies 2021, 28(2), 103-125. [CrossRef]

- Malinauskas R.; Malinauskiene V. A meta-analysis of psychological intervention for internet/smartphone addiction among adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2019, 9(4), 631-624. [CrossRef]

- Wacks Y.; Weinstein AM. Excessive Smartphone Use Is Associated With Health Problems in Adolescents and Young Adults. Front Psychiatry 2021, 28(12), 669042. [CrossRef]

- Alshobaili FA.; AlYousefi NA. The effect of smartphone usage at bedtime on sleep quality among Saudi non-medical staff at King Saud University Medical City. J Family Med Prim Care 2019, 8(6), 1953-1957. [CrossRef]

- Pantic I. Online social networking and mental health. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17(10), 652-657. [CrossRef]

- Seabrook EM.; Kern ML; Richard N. Social networking sites, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review. JMIR Ment. Health 2016, 3(4), e50. [CrossRef]

- Harwood J.; Dooley JJ.; Scott AJ.; Joiner R. Constantly connected–The effects of smart-devices on mental health. Computers in Human Behavior 2014, 34, 267–272. [CrossRef]

- Hartanto A.; Yang H. Is the smartphone a smart choice? The effect of smartphone separation on executive functions. Computers in Human Behavior 2016, 64, 329–336. [CrossRef]

- Yang Z; Asbury Y.; Griffiths MD. An exploration of problematic smartphone use among Chinese university students: Associations with academic anxiety, academic procrastination, self-regulation and subjective wellbeing. Int. J. Ment. Health Addiction 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wu R.; Guo L.; Rong H.; Shi J.; Li W.; Zhu M.; He Y.; Wang W.; Lu C. The Role of Problematic Smartphone Uses and Psychological Distress in the Relationship Between Sleep Quality and Disordered Eating Behaviors Among Chinese College Students. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 793506. [CrossRef]

- Sahin YL. Comparison of users’ adoption and use cases of Facebook and their academic procrastination. Digital. Education Review 2014, 25, 127–138. https://scholar.google.co.th/scholar_url?url=https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/4778261.pdf&hl=ko&sa=X&ei=ZBlDZYutJ92N6rQP4cu4oA4&scisig=AFWwaeafrnvEXrlJvJA43vkaoZBB&oi=scholarr.

- Kim Y.; Richards JS.; Oldehinkel AJ. Self-control, Mental Health Problems, and Family Functioning in Adolescence and Young Adulthood: Between-person Differences and Within-person Effects. J Youth Adolescence 2022, 51, 1181–1195. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Fernandez O.; Männikkö N.; Kääriäinen M.; Griffiths MD.; Kuss DJ. 2018. Mobile gaming and problematic smartphone use: A comparative study between Belgium and Finland. J Behav Addict 2018. 1;7(1), 88-99. [CrossRef]

- Harfield A.; Nang H.; Nakrang J.; Viriyapong R. A survey of technology usage by primary and secondary school children in Thailand. The Eleventh International Conference on eLearning for Knowledge-Based Society 2014. Retrieved from http://mobcomlab.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/elearning2014-harfield.pdf.

- Chinwong D.; Sukwuttichai P.; Saenjum C.; Klinjun N.; Chinwong S. Smartphone use and addiction among pharmarcy students in Northern Thailand: A cross-sectional study. Healthcar (Basel) 2023, 11(9), 1264. [CrossRef]

- D’souza J.; Sharma S. Smartphone addiction in relation to academic performance of students in Thailand. Journal of Community Development Research (Humanity and Social Science) 2020, 13(2). Retrieved from https://www.journal.nu.ac.th/JCDR/article/view/Vol-13-No-2-2020-31-41/1678.

- Tangmunkongvorakul A.; Musumari PM.; Thongpibul K.; Srithanaviboonchai K.; Techasrivichien T.; Suguimoto SP.; et al. Association of excessive smartphone use with psychological well-being among university students in Chiang Mai, Thailand. PLoS ONE 2019, 14(1): e0210294. [CrossRef]

- Bowen M. Family therapy in clinical practice. NY and London: Jason Aronson. 1978.

- Kerr ME, Bowen M. 1988. Family evaluation. New York: W. W. Norton. 1988.

- Bowen M. 1966. The use of family theory in clinical practice. Comprehensive Psychiatry 1966, 7(5), 345-374. In M. Bowen, 1978 (see above).

- Epstein NB.; Bishop DS.; Baldwin LM. McMaster Model of Family Functioning: A view of the normal family. In F. Walsh (Ed.), Normal family processes 1982, 115–141. Guilford Press.

- Miller IW.; Ryan CE.; Keitner GI.; Bishop DS.; Epstein NB. The McMaster approach to families: Theory, assessment, treatment and research. Journal of Family Therapy 2000, 22(2), 168–189. [CrossRef]

- Supphapitiphon S.; Buathong N.; Supppitiporn S. 2019. Reliability and validity of the family state and functioning assessment scale. Chula Med. J. 2019, 63(2), 103-109. [CrossRef]

- Hanphitakphong P.; Thawinchai N. 2020. Validation of Thai Addiction Scale-short version for school students between 10 to 18 years. Journal of Associated Medical Sciences 2020, 53(3), 34-42. Retrieved from https://he01.tcithaijo.org/index.php/bulletinAMS/article/view/235102.

- Kwon M.; Kim DJ.; Cho H.; Yang S. The smartphone addiction scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS One 2013, 8(12), e83558. [CrossRef]

- Davey S, Davey A. 2014. Assessment of Smartphone addiction in Indian Adolescents. A mixed method study by Systematic review and meta analysis approach. Int J Prev Med 2014, 5(12): 1500-11.

- Long L.; Liu T-Q.; Liao Y-H.; Qi C.; He H-Y.; Chen S-B.; Billieux J. Prevalence and corelates of problematic smartphone use in a large random sample of Chinese undergraduates. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16:408. [CrossRef]

- Fatkuriyah L.; Sun-Mi C. The relationship among parenting style, self-regulation, and smartphone addiction proneness in Indonesian junior high school students. Indonesian Journal of Nursing Practices 2021, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Lee C.; Lee S-H. Prevalence and predictors of smartphone addiction proneness among Korean adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review 2017, 77, 10-17. [CrossRef]

- Buctot DB.; Kim N.; Kim, JJ. 2020. Factors associated with smartphone addiction prevalence and its predictive capacity for health-related quality of life among Filipino adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review 2020, 100, 104758. [CrossRef]

- Gil S-Y.; Kim M-S.; Park K-W.; Lee H-J.; Park W-J.; Oh M-K. 2020. Associations between family function and smartphone addiction proneness in middle school student. The Korean Academy of Family Medicine 2020. [CrossRef]

- Shi X.; Wang J.; Zou H. 2017. Family functioning and internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: The mediating roles of self-esteem and loneliness. Computer in Human Behavior 2017, 76, 201-210. [CrossRef]

- Mangialavori S.; Russo C.; Jimeno MV.; Ricarte JJ.; D’Urso G.; Barni D.; Cacioppo M. 2021. Insecure Attachment Styles and Unbalanced Family Functioning as Risk Factors of Problematic Smartphone Use in Spanish Young Adults: A Relative Weight Analysis. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 1011–1021. [CrossRef]

- Niu G.; Yao L.; Wu L.; Tian Y.; Xu L.; Sun X. 2020. Parental phubbing and adolescent problematic mobile phone use: The role of parent-child relationship and self-control. Children and Youth Services Review 2020, 116, 105247. [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Pulgarín SA, Otero KLM, Herrera-López, HM. Risks on the Internet: the role of family support in Colombian adolescents. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology 2021, 19(1), 145-164. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal A, Firdous R, Hussain T. 2021. Social media and family integration: Perception of college students of Faisalabad. Global Regional Review 2021, V(II), 12-19. [CrossRef]

- Kim E.; Koh E. Avoidant attachment and smartphone addiction in college students: The mediating effects of anxiety and self-esteem. Comput. Hum. Behav 2018, 84, 264–271. [CrossRef]

- Kim E.; Cho I.; Kim EJ. Structural equation model of smartphone addiction based on adult attachment theory: Mediating effects of loneliness and depression. Asian Nurs. Res 2014. 11, 92–97. [CrossRef]

- Sutrisna IPB.; Ardjana IGA.; Supriyadi S.; Setyawati L. Good family function decrease internet addiction and increase academic performance in senior high school students. Journal of Clinical and Cultural Psychiatry 2020, 1(2), 28-31. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).