Submitted:

09 November 2023

Posted:

10 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Tools

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Description

2.3.2. Statistical Design and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Correlational Analysis

3.3. Contrast of Means

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- García, A.D.; Hernández, L.J.; Espinosa, C.J.F.; Soler, M.J. Salud mental en la adolescencia montevideana: una mirada desde el bienestar psicológico. Arch Venez Farmacol Ter 2020, 39, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailen, N.H.; Green, L.M.; Thompson, R.J. Understanding emotion in adolescents: A review of emotional frequency, intensity, instability, and clarity. Emot Rev 2019, 11, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de España. Real Decreto 463/2020, de 14 de marzo, por el que se declara el estado de alarma para la gestión de la situación de crisis sanitaria ocasionada por el COVID-19. «BOE» núm. 67, de 14 de marzo de 2020.

- Anglim, J.; Horwood, S.; Smillie, L.D.; Marrero, R.J.; Wood, J.K. Predicting psychological and subjective well-being from personality: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2020, 146, 279–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, J.; Lüftenegger, M.; Käser, U.; Korlat, S.; Pelikan, E.; Schultze-Krumbholz, A.; Spiel, C.; Wachs, S.; Schober, B. Students’ basic needs and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: A two-country study of basic psychological need satisfaction, intrinsic learning motivation, positive emotion and the moderating role of self-regulated learning. Int J Psychol 2021, 56, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgilés, M.; Tomczyk, S.; Amorós-Reche, V.; Espada, J.P.; Morales, A. Stressful Life Events in Children Aged 3 to 15 Years During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Latent Class Analysis. Psicothema 2023, 35, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamarit, A.; de la Barrera, U.; Mónaco, E.; Schoeps, K.; Montoya-Castilla, I. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in Spanish adolescents: Risk and protective factors of emotional symptoms. Rev Psicol Clín Niños Adolesc 2020, 7, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiano, R.M.; Prado, R.F.; Mustelier, B.RG. Salud mental en la infancia y adolescencia durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Rev Cubana Pediatr 2020, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Zheng, D.; Liu, J.; Gong, Y.; Guan, Z.; Lou, D. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 88, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, I.; Barba, M.J.; Lázaro, C.; Cuenca, J.; Samaniego, E. Prevención de los problemas socioemocionales en los centros educativos. Una propuesta de intervención psicoeducativa. Rev Orient Educ AOSMA 2022, 31, 36–66. [Google Scholar]

- Oram, R.; Ryan, J.; Rogers, M.; Heath, N. Emotion regulation and academic perceptions in adolescence. Emot Behav Diffic 2017, 22, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenreich-May J, Kennedy SM, Sherman JA, Bennett SM, Barlow DH. Protocolo unificado para el tratamiento transdiagnóstico de los trastornos emocionales en adolescentes. Manual del terapeuta. Pirámide. 2022.

- Achenbach, T.M. International findings with the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA): applications to clinical services, research, and training. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Healt 2019, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcón, P.D.; Bárrig, J.P.S. Internalizing and externalizing behaviors in adolescents. Liberabit. Rev Peru Psicol 2015, 21, 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, P.M.A.; Belmonte, G.L.; Martínez, A.M.M. Autoestima y ansiedad en los adolescentes. ReiDoCrea 2018, 7, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud, OMS. Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades, undécima revisión (CIE-11). 2019. https://icd.who.int/browse11.

- Lizano, O.J. Autoestima y depresión en adolescentes del distrito de San Vicente. Tesis doctoral. Universidad Católica de los Ángeles. 2023. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.13032/31999. 1303.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Association. 2014.

- Lohmann, M.J.; Boothe, K.A.; Nenovich, N.M. Using Classroom Design to Reduce Challenging Behaviors in the Elementary Classroom. Classroom Manag Ser 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Salavera, C.; Usán, S.P. Influencia de los problemas internalizantes y externalizantes en la autoeficacia en estudiantes de Secundaria. Rev Investig Educ 2019, 37, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caqueo, U.A.; Mena, C.P.; Flores, J.; Narea, M.; Irarrázaval, M. Problemas de regulación emocional y salud mental en adolescentes del norte de Chile. Ter Psicol 2020, 38, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesurado, B.; Vidal, E.M.; Mestre, A.L. Negative emotions and behaviour: The role of regulatory emotional self-efficacy. J Adolesc 2018, 64, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey, B.M.; Calonge, R.I.; Martínez, A.M.; Thomas, C.H. Sexo como variable moderadora de la sintomatología internalizante y externalizante en la infancia. Rev. esp. salud pública 2023, e202303022-e202303022.

- Carapeto, M.J.; Domingos, R.; Veiga, G. Attachment and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescence: The Mediatory Role of Emotion Awareness. Behav Sci 2022, 12, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter, F.; Dalbert, C.; Kloeckner, N.; Radant, M. Personal belief in a just world, experience of teacher justice, and school distress in different class contexts. Eur J Psychol Educ 2013, 28, 1221–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.W.; Roker, R.; Bowling, A. Gender differences in the association between aggression and substance use among African American adolescents. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse 2020, 29, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancey, T.J.; Bennett, D.C.; Benner, A.D.; Li, F. Gender differences in behavioral and academic trajectories from kindergarten to eighth grade. Dev Psychol 2019, 55, 1004–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, A.; Antolín, L.; Pertegal, M.A.; Ríos, M.; Parra, Á.; Hernando, A.; Hernández, J.A. Gender differences in aggressive behavior among adolescents and young adults: A study from the Canary Islands. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 2017, 17, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, A.; Álvarez, G.D.; Pérez, F.M.C. Ansiedad y autoestima en los perfiles de cibervictimización de los adolescentes. Comunicar 2021, 29, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farías, Á.D.R.; Urra, R.G. Funcionalidad familiar y autoestima en adolescentes durante la pandemia por COVID-19. Rev PSIDIAL Psicol Diálogo Saberes 2022, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibby, R.; Hartwell, B.K.; Wright, S. Dyslexia, literacy difficulties and the self-perceptions of children and young people: A systematic review. Curr Psychol 2021, 40, 5595–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korlat, S.; Reiter, J.; Kollmayer, M.; Holzer, J.; Pelikan, E.; Schober, B.; Spiel, C.; Lüftenegger, M. Basic psychological needs and agency and communion during the COVID-19 pandemic: Gender differentials and the role of well-being in adolescence and early adulthood. J Individ Differ 2023, 44, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada, L. Reflexión y construcción del conocimiento en torno a las habilidades sociales y la competencia social. Rev Carib Investig Educ 2018, 2, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, L.; Plötner, M.; Schmitz, J. Social competence and psychopathology in early childhood: A systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019, 28, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar EFR. Variables psicológicas y educativas para la intervención en el ámbito escolar. En M.M. Molero, A. Martos, A.B. Barragán, M.M Simón, M. sisto, R.M. Pino, B.M. Tortosa, & J.J. Gázquez (Eds.) Variables psicológicas y educativas para la intervención en el ámbito escolar: nuevas realidades de análisis. Dykinson 2020, 9-102.

- Portela, P.I.; Alvariñas, V.M.; Pino, J. M. Socio-Emotional Skills in Adolescence. Influence of Personal and Extracurricular Variables. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pinto I, Santamaría P, Sánchez-Sánchez F, Carrasco MA, Del Barrio V. Sistema de Evaluación de Niños y Adolescentes (SENA). TEA Ediciones. 2015.

- Schoeps, K.; Tamarit, A.; González, R.; Montoya, C.I. Competencias emocionales y autoestima en la adolescencia: Impacto sobre el ajuste psicológico. Rev Psicol Clín Niños Adolesc 2019, 6, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds C, Kamphaus R. Sistema de evaluación de la conducta de niños y adolescentes (BASC). Pearson. 2004.

- Morey LC. Inventario de evaluación de la personalidad para adolescentes (PAI-A). TEA Ediciones. 2015.

- Consejería de Educación de la Junta de Andalucía. La educación en Andalucía. Datos y cifras. Gobierno Andaluz: Sevilla, ESP. 2021.

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 25), [Computer software]. IBM Corp. 2021.

- González, R.M.; Delgadillo, R.G.; Valles, M.A.M.; Caloca, L.H.; de la Mora, S. Internalizing and externalizing behaviors in high school adolescents in a northern border city of Mexico and their type of family. Aten primaria 2023, 55, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.J.; Kim, B.N.; Song, D.H. Gender differences in the relationships between internet gaming disorder and aggression among South Korean teenagers. J Psychiatr Res 2018, 98, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Carre, J.M.; Archer, J. Testosterone and human aggression: An evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2020, 116, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettencourt, A.; Farrell, A.; Liu, W. Gender differences in aggression: The mediating role of social information processing. J Youth Adolesc 2020, 49, 858–874. [Google Scholar]

- Stegge, H.; Terwogt, M. M. Emotional intelligence, self-esteem, and externalizing problems in early adolescence. J Early Adolesc 2017, 37, 681–696. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, C.M.; Nelson, L.J.; Dulin, R. Associations between adolescent externalizing behaviors, mental health, and social competence: A longitudinal study. J Child Fam Stud 2019, 28, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Harachi, T.W. The mediating role of social integration in the relationship between aggression and substance use in early adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 2020, 49, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canals, J.; Voltas, N.; Hernández-Martínez, C.; Cosi, S.; Arija, V. Prevalence of DSM-5 anxiety disorders, comorbidity, and persistence of symptoms in Spanish early adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019, 28, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resa, J. A. Z. Gestión Emocional durante la cuarentena: orientaciones desde la práctica de la Atención Plena. Rev Orient Educ AOSMA 2020, 28, 134-1. [Google Scholar]

| Academic Year | n | female | male | f |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st year of Compulsory Secondary Education | 109 | 60 | 49 | 24.5 |

| 2nd year of Compulsory Secondary Education | 210 | 115 | 95 | 47.2 |

| 3rd year of Compulsory Secondary Education | 66 | 33 | 33 | 14.8 |

| 4th year of Compulsory Secondary Education | 60 | 22 | 38 | 13.5 |

| Total | 445 | 215 | 230 | 100 |

| Variables | N | Pmín | Pmáx | αt | αe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANX | 10 | 10 | 50 | .87 | .89 |

| DEP | 14 | 14 | 70 | .91 | .94 |

| ANG | 8 | 8 | 40 | .89 | .88 |

| AGR | 7 | 7 | 35 | .91 | .81 |

| SEL | 7 | 7 | 35 | .93 | .95 |

| SOC | 7 | 7 | 35 | .93 | .88 |

| AWE | 9 | 9 | 45 | .93 | .88 |

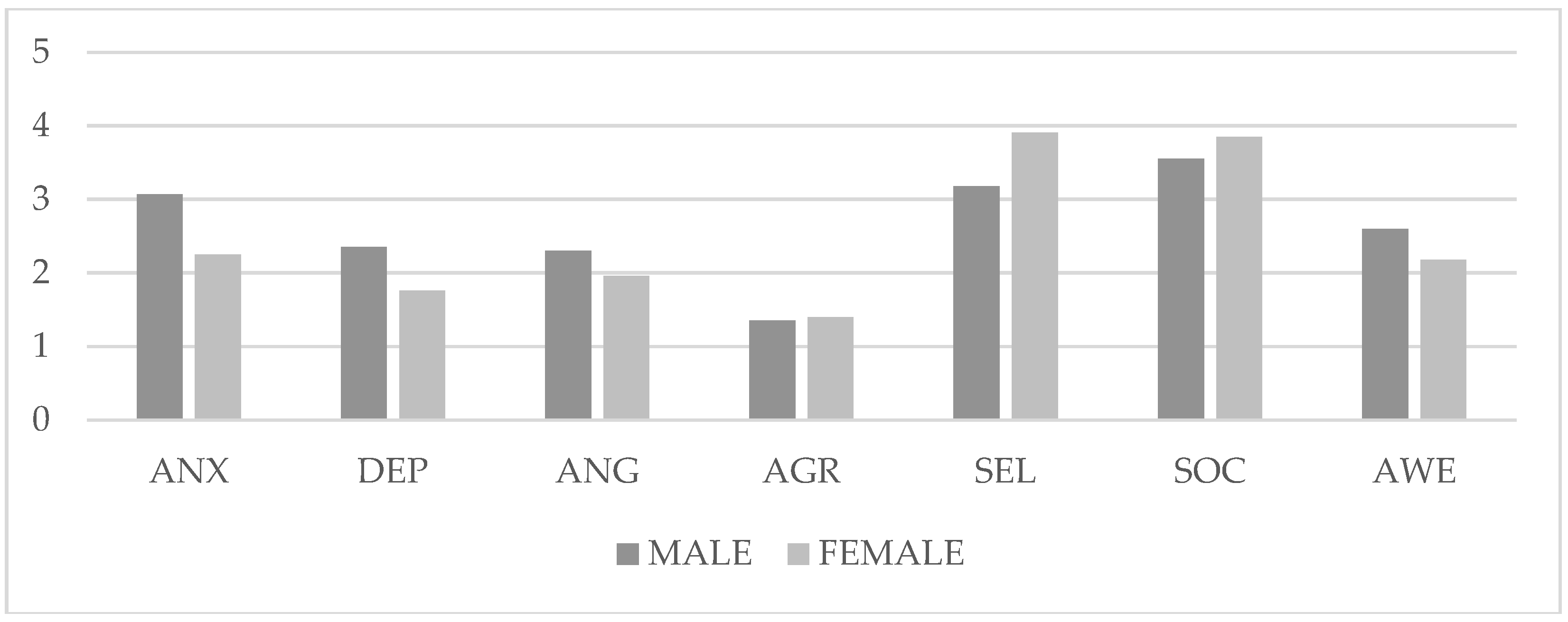

| Variables | Female | Male | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | |

| ANX | 3.07 (0.96) | 1.00-5.00 | 2.25 (0.82) | 1.00-5.00 |

| DEP | 2.35 (0.99) | 1.00-4.57 | 1.76 (0.75) | 1.00-5.00 |

| ANG | 2.30 (0.92) | 1.00-4.88 | 1.96 (0.86) | 1.00-5.00 |

| AGR | 1.35 (0.45) | 1.00-3.57 | 1.40 (0.53) | 1.00-3.86 |

| SEL | 3.18 (1.07) | 1.00-5.00 | 3.91 (0.87) | 1.00-5.00 |

| SOC | 3.55 (0.79) | 1.44-5.00 | 3.85 (0.76) | 1.44-5.00 |

| AWE | 2.60 (0.89) | 1.00-4.29 | 2.18 (0.78) | 1.00-5.00 |

| Variables | ANX | DEP | ANG | AGR | SEL | SOC | AWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANX | .724** | .456** | .366** | -.528** | -.247*** | .598** | |

| DEP | .815** | .553** | .427** | -.664** | -.422*** | .673** | |

| ANG | .445** | .471** | .626** | -.277** | -.093** | .440** | |

| AGR | .255** | .309** | .635** | -.271** | -.078** | .422** | |

| SEL | -.687** | -.798** | -.388** | -.257** | .613** | -.442** | |

| SOC | -.349** | -.488** | -.160** | .020** | .537** | -.231** | |

| AWE | .750** | .775** | .440** | .318** | -.676** | -.410** |

| Male | Female | U | p | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | ||||

| ANX | 3.07 (0.96) | 2.25 (0.82) | 12582 | .001 | 0.49 |

| DEP | 2.35 (0.99) | 1.76 (0.75) | 15680 | .001 | 0.36 |

| ANG | 2.30 (0.92) | 1.96 (0.86) | 18971 | .001 | 0.23 |

| AGR | 1.35 (0.45) | 1.40 (0.53) | 24553 | .897 | - |

| SEL | 3.18 (1.07) | 3.91 (0.87) | 14897 | .001 | 0.39 |

| SOC | 3.55 (0.79) | 3.85 (0.76) | 19201 | .001 | 0.22 |

| AWE | 2.60 (0.89) | 2.18 (0.78) | 17983 | .001 | 0.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).