1. Introduction

Childhood drowning is a concerning public health problem that affects communities worldwide [

1,

2], being the third leading cause of global child mortality among children aged 5 and older [

3]. Incidents involving children in aquatic environments have multifactorial causes, including lack of aquatic competence [

4], absence of direct supervision, and caregivers’ negligence [

5,

6,

7,

8].

Education must play a crucial role in drowning prevention, and different school programs, from preschool to secondary education, have demonstrated benefits related to drowning prevention [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Childhood drowning incidents are multifactorial, so their approach should also involve parents or caregivers, as they reinforce learning and safe behaviors in the aquatic environment [

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, there is a gap in knowledge about which activities or educational approaches for younger children could be effective alternatives, as well as how to address them from a family perspective. Furthermore, there is general agreement that community intervention has a beneficial effect in preventing drowning [

19].

An overall purpose of drowning research should be to provide low-cost, wide-ranging, and easily replicable educational resources and strategies to mitigate the cultural or economic gap, particularly focusing on low-income countries where children are more vulnerable [

3]. In the quest for effective strategies, scientific evidence has shown that theatrical performances, especially those involving puppets, have great potential for teaching content related to injury prevention and health education due to their incorporation of fantasy elements and imagination, allowing recipients to actively engage in the teaching-learning process [

20]. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no research has yet been conducted on drowning prevention using puppets.

Therefore, based on the hypothesis that a puppet show, specifically written with messages towards safety in the aquatic environment, would improve the knowledge and attitudes of both children and their parents regarding drowning prevention and the activation of the chain-of-survival, this study aimed to assess the feasibility and immediate effects of this innovative teaching strategy and tool.

2. Materials and Methods

A quasi-experimental study was designed, comprising three phases: creation of the puppet show, recruitment of the sample, and pre- and post-intervention evaluation. The research team consisted of eight experts, including 1 pediatrician, 1 puppeteer, 2 lifeguards, 2 university professors specializing in arts, and 2 university professors who were experts in drowning prevention. This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Education and Sports Sciences of the University of Vigo, with the code 06-170123, in accordance with the ethical principles of the Helsinki Convention.

2.1. Creation of the Puppet Show

The play was an adaptation of the children’s book “The rat who wanted to learn to swim” (“

O rato con as que quería aprender a nadar”) [

21]. This book pedagogically addresses the most frequent incidents reported in scientific literature as known causes of child drowning [

5,

6,

13,

22,

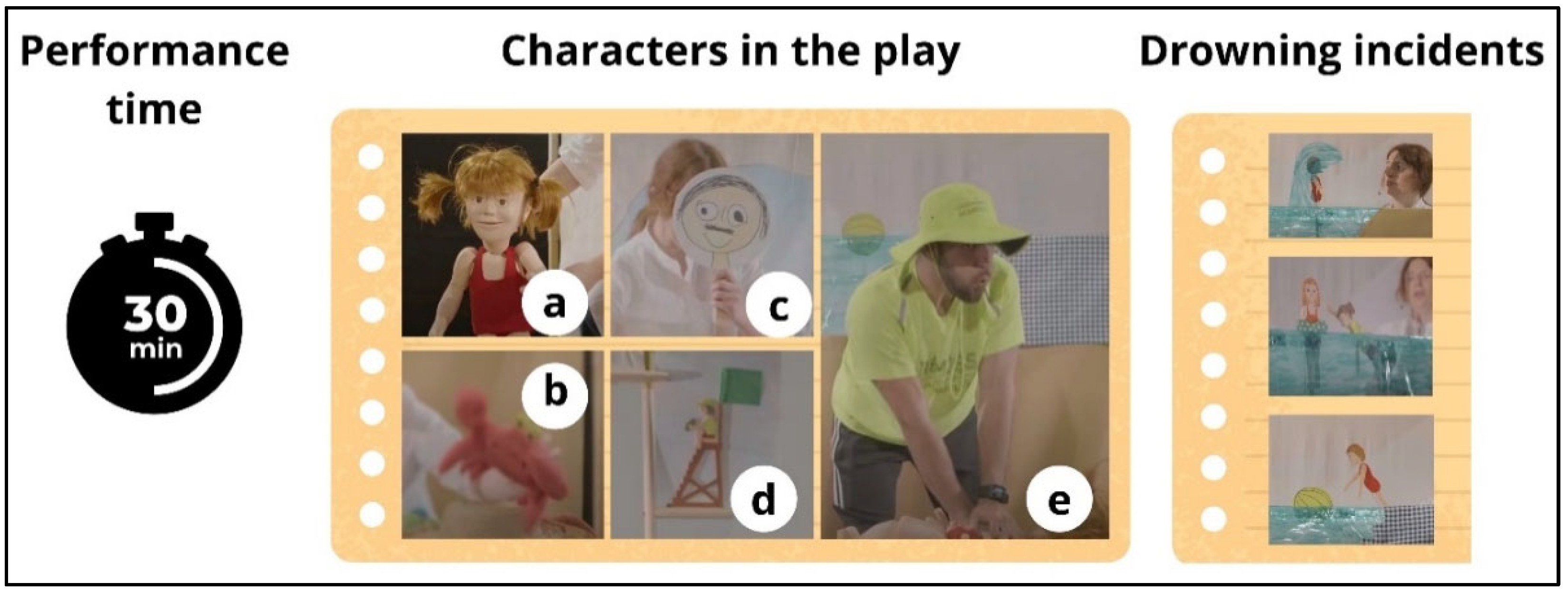

23] and covers the following topics: the meaning of safety flags on beaches, how to activate emergency services in case of witnessing a drowning, and basic tips for safe bathing (such as the importance of never bathing alone, even when using floating devices). The group of experts adapted the book’s messages and scripted the puppet play. This play depicted the aquatic adventures of the protagonist puppet, designed in the likeness of an approximately five-year-old girl. Throughout the performance, this puppet experienced two drowning incidents, one at the beach and another in a pool. The plot of the play is summarized below:

“A girl (the puppet) was at the beach and decided to swim in the sea without adult supervision, despite the warning of the red flag. This led her to aspirate water and cough (non-fatal drowning - grade 1). Subsequently, the same girl re-entered the water equipped with a ring-shaped float. Due to the wind, she was carried farther out to sea, requiring a rescue by the lifeguard and the incident only resulted in a warning (water rescue). After this incident, upon returning home, she attempted to retrieve a ball from her pool but slipped and fell, initiating the drowning process. Her mother promptly called the emergency number 112, and a lifeguard (another character) performed cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR), explaining the steps to the public. The protagonist puppet was revived in the scene (non-fatal drowning - grade 6). The story concludes with a moral emphasizing prevention, the importance of respecting sea warning flags, always bathing under adult supervision, remembering the emergency number 112, and the steps of CPR.”

Therefore, the cast of the play (

Figure 1) included: a) the main character, a 5-year-old girl named Lis (puppet) who served as the protagonist around whom the story revolves; b) a crab (puppet), who was her friend and reinforced the educational messages; c) the mother (actress) who alternated between offering educational advices and displaying confusion and lack of attention during drownings; d) a lifeguard (puppet) who performed the sea rescue; and e) a lifeguard (actor) taught the CPR protocol and saved the main character (Lis). The recording of the performance is available online at the following link:

https://youtu.be/BSveUwewTyA.

2.2. Sample

A total of 345 subjects participated in this study, comprising 185 children (85 boys and 100 girls) aged between 4 and 8 years (mean age: 6.2 ± 1.1 years) and 160 parents (134 mothers and 26 fathers) aged between 29 and 56, with an average age of 41.7 ± 4.8 years. The study involved 11 theatrical performances conducted in different cities and towns in Galicia (northwest Spain). Each performance accommodated between 20 and 40 people and was advertised in local press and on the institutional website of the University of Vigo. The inclusion criteria for children encompassed an age range of 4 and 8 years, parental authorization, and voluntary participation. For adults, inclusion required a parental (father or mother) relationship with the child attending the puppet show. Participants did not receive any form of compensation for their involvement and attendance to the puppet show was free. The children’s legal tutors provided informed consent for the use of their data in this research.

2.3. Intervention, Variables, and Evaluation

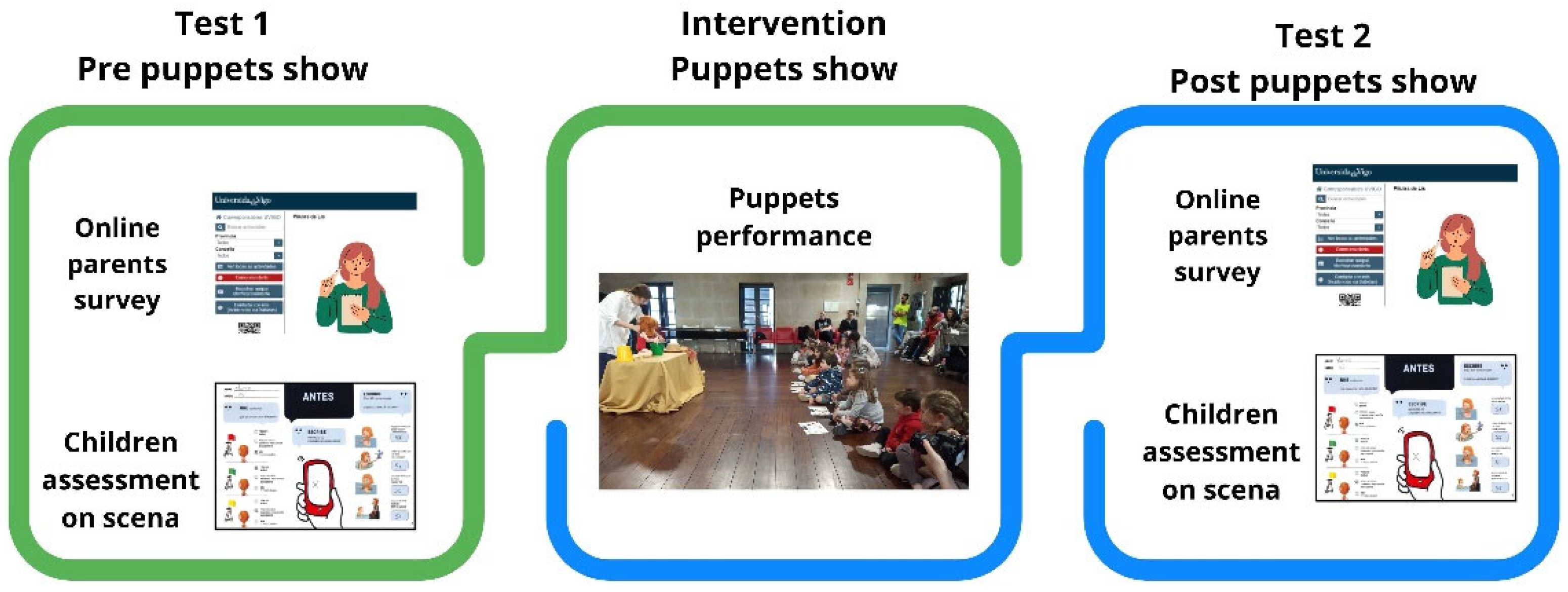

The puppets show was programmed to last 30 minutes and was consistently performed by the same actress and characters, as well as under optimal conditions of light, sound, and space. The research design focused on two groups: a) the pre- and post-intervention knowledge of the children, and b) the attitudes and knowledge about drowning prevention among the parents (

Figure 2).

2.3.1. Children’s Knowledge in Drowning Prevention (Pre- and Post-Intervention).

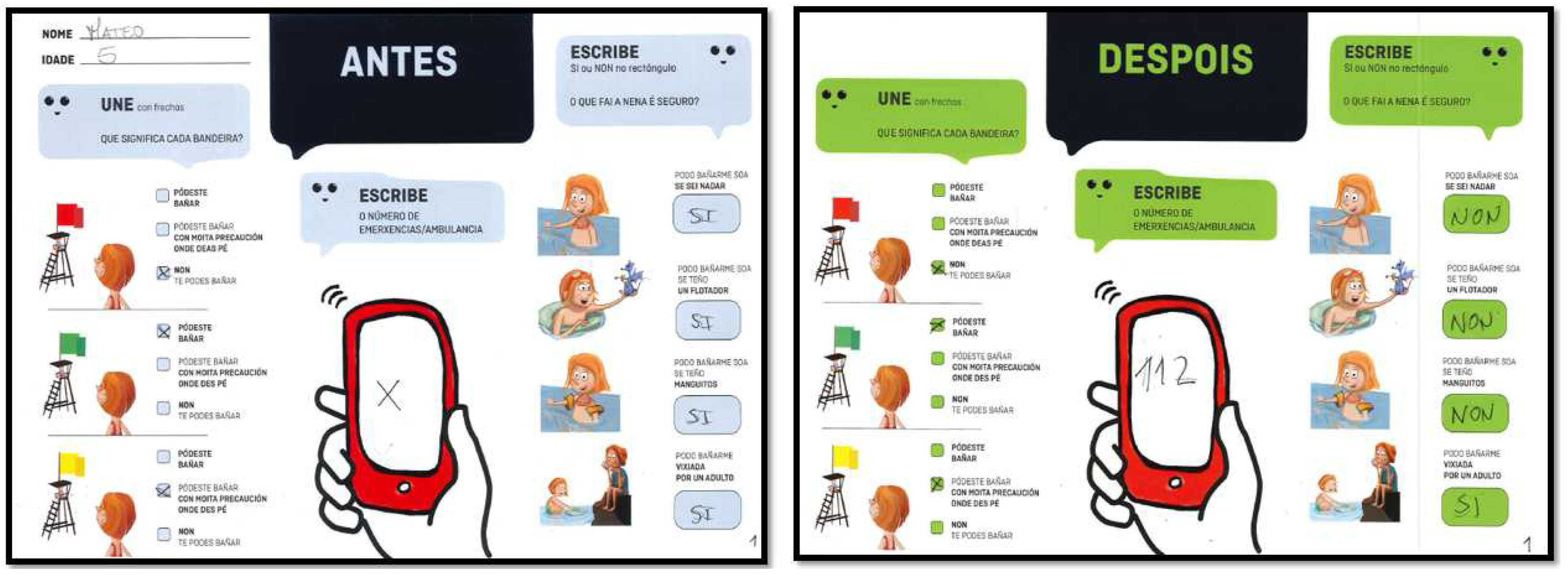

The evaluation tool was designed in the format of a children’s school card, where children were required to answer a series of questions presented in the form of illustrations (

Figure 3). This evaluation system was employed based on a previous pilot study that demonstrated its methodological feasibility among similar age groups [

13]. The design and iconography of the evaluation sheet was created by two professionals in graphic design and arts, with extensive experience in illustration and creation of children’s materials.

Before the puppet show, the children individually filled out the evaluation form (Test 1). Immediately following the performance, once again individually, they completed the reverse side of the evaluation form, which held the exact same set of questions (Test 2).

The variables were grouped into three blocks: 1) the association between flag colors and their corresponding meanings, 2) knowledge of the emergency number, and 3) safe bathing behaviors (being alone, using a float, wearing sleeves and/or being supervised by an adult). For the evaluation, a dichotomous scale of correctness or error was used for each item, alongside a cumulative variable reflecting the total count of correctly answered items.

2.3.1. Parents’ Behaviors and Knowledge Regarding Drowning Prevention.

For parents, the research team designed a questionnaire consisting of 10 questions. Following a discussion process based on the focus group technique, 3 questions were eliminated, resulting in a consensus of 7 questions. Questions Q1 and Q2 were administered before the puppet show to assess the children’s aquatic skills according to the classification of Szpilman et al [

4] and to determine whether they had experienced any significant distractions or lapses in attention during their child’s bath at any point. Questions Q3-Q6 were presented both before and after the performance, with the purpose of assessing whether the puppet show had influenced parents’ preferences regarding the choice of beaches with the presence of lifeguards, exploring the use of flotation devices as a measure for drowning prevention, investigating understanding of the meanings of sea state flags, and analyzing knowledge of CPR. Finally, Q7 aimed to determine if the puppet show induced any changes in knowledge regarding drowning prevention (

Table 1). Parents completed this survey electronically through an email invitation sent during the registration process for the puppet show and during the week following their attendance at the event.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using the statistical package IBM SPSS for Windows (version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). The descriptive results for qualitive variables are presented as absolute frequencies (F) and relative percentages (%) of responses, while mean and standard deviation (SD) are provided for continuous variables. The McNemar test was used to analyze the differences in children’s responses and parents’ perceptions before and after the intervention. The differences between the number of correct responses of children before and after the intervention were analyzed using the Wilcoxon test. For all analyses, the significance value was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Children’s Knowledge in Drowning Prevention.

Table 2 shows the differences in children’s knowledge on water safety before and after the intervention. Overall, children answered an average of 5.5 ± 1.5 out of 8 questions correctly before the intervention, whereas after the intervention, the number of correct answers increased to 7.6 ± 0.9. Thus, there was a significant improvement in children’s overall knowledge on water safety following the intervention (Wilcoxon

Z = 10.746;

p < 0.001). More specifically, the percentage of correct responses significantly increased (p < 0.05) for all items asked to the children, except for bathing under adult supervision, where there was little room for improvement as a high number of correct responses were already obtained in the initial test. In the third block, there was an approximate 50% increase in the percentage of correct responses for the variables bathing alone, using a flotation device, and using armbands.

3.2. Parents’ Behaviors and Knowledge Regarding Drowning Prevention

Table 3 displays the information on parental behaviors and knowledge about water safety before and after the intervention. Around 80% of children lacked the ability to swim or had basic flotation skills. Moreover, 17.5% of parents acknowledged that they had inadvertently left their children unsupervised near water or allowed them to bathe without supervision at some point.

The majority of parents (46.1%) indicated that they did not consider the presence of lifeguards as a determining factor when selecting a beach or pool, while 21.1% stated that they did not take it into account at all. In contrast, 19.7% expressed a preference for beaches with lifeguards, and 13.2% considered it a crucial factor. However, there was a significant shift in this perception of lifeguards’ importance following the intervention. Most parents (38.2%) stated a preference for beaches with lifeguards, and 26.3% considered their presence a determining factor. Regarding the use of armbands and floaters as a preventive measure against drowning, the majority of parents reported that their children used them sometimes (35.5%) or always (22.4%), while others indicated that they never (26.3%) or rarely (15.8%) used such devices. After the intervention, parents expressed a greater inclination toward their children using these devices. Specifically, 35.5% of parents stated their children would use them sometimes, and 39.5% indicated they would use them always.

With respect to the knowledge of the meaning of the three flags denoting sea conditions (green, yellow, and red), before to the intervention, 97.4% of parents were familiar their meaning. After the intervention, all parents reported being aware of their meanings. Furthermore, there was a significant increase (McNemar = 36.980; p < 0.001) in the percentage of parents who considered themselves knowledgeable in performing pediatric CPR, rising from 71.1% to 86.4% following the intervention.

Overall, although most parents (42.1%) already perceived themselves as highly aware of the behaviors and recommendations presented in the performance, others reported a slight (14.5%), moderate (26.3%), or substantial (17.1%) increase in their understanding of child drowning prevention. Furthermore, the parents’ overall evaluation of the theatrical performance averaged 3.8 ± 0.4 on a 4-point Likert scale.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to analyze the knowledge and perceptions of children and their parents regarding aquatic safety. It was also intended to promote a more proactive awareness of drowning prevention through attendance to a puppet show. The main findings were as follows: a) Children demonstrated a high level of knowledge about the meaning of flags but had limited awareness of the emergency number. A high percentage of children believed they could bathe without adult supervision. Some adults acknowledged failures in supervision while their children were in the water. b) Parents’ choice of aquatic spaces did not respond to a safety criterion, such as the presence of a lifeguard, even though the majority of children possessed only basic aquatic competence or do not know how to swim. c) After the puppet show, children exhibited increased confidence in their preference for bathing supervised by adults. Among parents, half of them considered that the performance would lead to changes (to a greater or lesser extent) in safer and more preventive behaviors in aquatic environments, while also enhancing their knowledge of CPR.

In the battle against drowning, the World Health Organization (WHO) advocates for community-based educational initiatives that focus on enhancing public awareness and education regarding the use of aquatic spaces, training children and bystanders in safe bathing, safe rescue procedures, and CPR [

3]. Accessibility is also promoted, so the creation of educational materials and resources must be a priority strategy. In addition, various previous experiences using comics, stories [

13], and songs [

12] have proven effective in enhancing children’s understanding of water safety. In this regard, puppet plays have been implemented in diverse health areas for educational purposes [

24,

25]. However, to the best of our knowledge, their effect on preventing drowning has never been studied.

The use of puppets in the shape of children serves as a pedagogical tool since they can be perceived as peers by other children. This educational approach is practical and cost-effective, and it also allows for addressing false beliefs within an imaginary scenario [

26]. However, children’s learning from puppets may not necessarily align with their learning from real-world social agents, such as adults [

27]. To mitigate potential discrepancies between the imaginary and the real, a collective activity involving parents and children was promoted. In this activity, puppet representations were used to impart new knowledge and encourage safer behaviors related to drowning prevention at the family level.

In the first phase, the primary aim was to identify the baseline. It became apparent that the children participating in this study had a basic aquatic competence, as reported by their parents. Aquatic competence is defined as the set of skills essential for surviving common drowning situations [

6] and even includes the ability to identify a swimmer in distress, call for help, or perform a safe rescue [

28]. However, young children often lack developed aquatic skills, consequently heightening their vulnerability in water [

4]. Moreover, the current findings revealed that a significant proportion of children did not recognize bathing alone as potentially dangerous behavior, and approximately 20% of parents admitted to instances of inadequate supervision during their children’s aquatic activities, even on more than one occasion. This situation is not coincidental, as other studies have also identified that between 15% and 30% of caregivers have left young children unsupervised for periods ranging from 1 to 5 minutes during bathing [

7].

The puppet show emphasized this key concept, highlighting unsupervised access to water as the primary trigger for drowning in young children [

5,

6,

7,

29,

30]. Throughout the storyline, the puppet experienced two non-fatal drownings, both of which could have been prevented if parents had been present. While some may believe that children carrying floating devices or knowing how to swim might relax their attention, but it is crucial to note that knowing how to swim is not “drown proof” against drowning [

15]. The American Academy of Pediatrics emphasizes that parents and caregivers should never – even for a moment – leave children alone or in the care of another child in bathtubs, swimming pools, or open water [

6]. The primary preventive strategy is supervision [

7,

14], defined as direct, contact supervision, where adults are within arm’s reach of the child [

6]. Adequate supervision comprises three key components: proximity, attention, and continuity [

31]. Therefore, parents play an active role and become aware of the importance of supervision. After the intervention, half of the parents indicated an increase in their knowledge about preventing drowning after attending the puppet show. Moreover, over 80% of the children responded that bathing alone was an incorrect behavior. Another positive outcome from the puppet show was an increase in parents’ intention to visit supervised beaches, recognizing that lifeguards provide additional security [

6,

32].

In the puppet show, the recognition of sea state flags was promoted, as it is directly related to drowning prevention. Prior to the intervention, parents and children already possessed a high level of knowledge regarding their meanings. Following attendance at the puppet show, flag recognition reached nearly 100%. These findings suggest that using simple visual elements is an effective strategy. However, there is still no universal consensus regarding this symbology. In various regions worldwide, such as Spain, the flags represent traffic light colors, but in other areas, up to 6 or 7 flags coexist, differing in colors and even shapes, potentially hindering comprehension, especially among children. This leads to the question of why there exists an almost unanimous global consensus in most danger symbols or road signs, while the same does not hold true for symbols and signs in aquatic environments.

In the drowning survival chain, the first step is prevention, while the second is recognizing aquatic distress and asking for help [

33]. Therefore, this puppet show also aimed to teach how to ask for help. Contacting emergency services not only activates the chain but also serves as a preventive measure against further rescue attempts by laypeople, which could potentially result in the drowning of both the victim and the rescuer [

34,

35]. Overall, over half of the children in this study were already aware of the European emergency telephone number (112). However, after the intervention, nearly 100% of them indicated they would know whom to call in the event of an emergency occurring in an aquatic setting.

The final step in the chain of survival for drowning is to provide necessary care [

33]. Our puppet show addressed this content by incorporating recommended adaptations for managing cardiac arrest resulting from drowning (rescue ventilations, 30 chest compressions – 2 ventilations). Tobin et al. [

36] observed neurologically favorable survival rates in children who received bystander compressions and ventilations. Therefore, it is imperative to train and encourage parents in the application of conventional CPR. The aim of this intervention was to move from the standard recommendation for laypeople of “just compress” towards the recommendation of “compress and ventilate”, specifically in cases involving children and/or individuals experiencing cardiorespiratory arrest due to drowning. In the theatrical performance, an actor (lifeguard) successfully resuscitates the puppet (the main protagonist) and during the CPR demonstration, the actor interacts with the audience, explaining key guidelines according to the European Resuscitation Council’s recommendations for specific circumstances (drowning) [

37]. Upon completion of the intervention, 86% of parents reported knowledge of the CPR techniques indicated for drowning. This dissemination led to a majority of adults being theoretically aware of the peculiarities of performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation in cases of asphyxia.

4.1. Practical Implications

Young children represent a particularly vulnerable group due to their limited ability to assess risks effectively and their insufficiently developed swimming skills, which impede their autonomy in aquatic environments [

19]. Preventing aquatic incidents requires a multifaceted approach, with education playing a pivotal role. Evidence has shown that educational activities involving children, parents, or communities have a positive impact on drowning prevention. The challenge, however, lies in providing cost-effective interventions (for greater accessibility) that are pedagogically efficient, and replicable. An example of such an intervention is the “

Kim na escola” project, promoted by the Brazilian Aquatic Rescue Society (SOBRASA) [

38]. Puppets can serve as an alternative meeting all these criteria and can be integrated into various programs implemented across different countries.

4.2. Limitations of this Study

This research has some limitations that must be pointed out. The study was confined to a specific Spanish region with a strong connection to the sea; hence, it is plausible that different answers might have been observed in other locations or among individuals with distinct cultural profiles. Additionally, a bias exists that is challenging to control concerning certain responses, as a correct answer does not necessarily correlate with correct behavior. Therefore, future research should aim to investigate the effects of parental and child behaviors in actual aquatic incidents.

5. Conclusions

A community educational model based on a puppet show is effective in promoting knowledge and safer behavioral practices for the prevention of drowning, targeting both young children and their parents. Puppets can be an engaging, interactive method to enhance the connection with both children and adults, effectively conveying essential messages that contribute to reducing the incidence of drowning. Through the puppet-based approach, parents can shift their mindset towards adopting safer and more proactive behaviors in drowning prevention while gaining new knowledge. Hence, encouraging and facilitating parental participation in educational activities tailored for children is highly recommended.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B.-F., L.P.-P., B.P.-G. and A.R.-N.; methodology, R.B.-F., L.P.-P., B.P.-G. and A.R.-N.; formal analysis, M.L.-M.; investigation, R.B.-F., L.P.-P., B.P.-G..; resources, B.P.-G., A.G.-S., C.V.-C.; data curation, M.L.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P.-P., R.B.-F, A.R.-N.; writing—review and editing, M.L.-M.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, L.P.-P., B.P-G, A.G-S., A.R.-N.; project administration, A.G.-S., C.V.-C., J.R.-D; funding acquisition, J.R.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has been funded by the Vice-Rectorate for University Extension of the University of Vigo (Spain), within the ’Corresponsables’ program promoted by the Xunta de Galicia (Spain)."

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Education and Sports Sciences of the University of Vigo, with the code 06-170123, in accordance with the ethical principles of the Helsinki Convention.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all children and parents involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wu Y, Huang Y, Schwebel DC, Hu G. Unintentional Child and Adolescent Drowning Mortality from 2000 to 2013 in 21 Countries: Analysis of the WHO Mortality Database. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017, 14, 875. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Preventing drowning. Practical guidance for the provision of day-care, basic swimming and water safety skills, and safe rescue and resuscitation training. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- World Health Organization. Preventing drowning: an implementation guide. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland 2017.

- Szpilman D, Pinheiro AMG, Madormo S, Palacios-Aguilar J, Otero-Agra M, Blitvich J, Barcala-Furelos R. Análisis del riesgo de ahogamiento asociado al entorno acuático y competencia natatoria [Analysis of the drowning risk associated with aquatic environment and swimming ability]. Rev Int Med Cienc Act Física Deporte. 2022, 22, 917-932.

- Sánchez-Lloria P, Barcala-Furelos R, Otero-Agra M, Aranda-García S, Cosido-Cobos Ó, Blanco-Prieto J, Muñoz-Barús I, Rodríguez-Núñez A. Análisis descriptivo de las causas, consecuencias y respuesta de los sistemas de Salud Pública en los ahogamientos pediátricos en Galicia. Un estudio retrospectivo de 17 años [Descriptive analysis of triggers, outcomes and the response of the health systems of child drowning in Galicia (Spain). A 17-year retrospective study]. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2022, 22, e202206048.

- Denny SA, Quan L, Gilchrist J, McCallin T, Shenoi R, Yusuf S, Hoffman B, Weiss J. Prevention of Drowning. Pediatrics. 2019, 143, e20190850.

- Denny SA, Quan L, Gilchrist J, McCallin T, Shenoi R, Yusuf S, Weiss J, Hoffman B. Prevention of Drowning. Pediatrics. 2021, 148, e2021052227.

- Petrass LA, Blitvich JD, Finch CF. Lack of caregiver supervision: a contributing factor in Australian unintentional child drowning deaths, 2000–2009. Med J Aust. 2011, 194, 228-231. [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira J, Piñeiro-Pereira L, Padrón-Cabo A, Alonso-Calvete A, García-Crespo O, Varela-Casal C, Queiroga AC, Barcala-Furelos R. Percepciones, conocimientos y educación para la prevención del ahogamiento en adolescentes [Perception, knowledge and education for drowning prevention in adolescent]. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2021, 11, e202111148.

- Wilks J, Kanasa H, Pendergast D, Clark K. Beach safety education for primary school children. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2017, 24, 283-292. [CrossRef]

- Wilks J, Kanasa H, Pendergast D, Clark K. Emergency response readiness for primary school children. Aust Health Rev Publ Aust Hosp Assoc. 2016, 40, 357-363. [CrossRef]

- Peixoto-Pino L, Barcala-Furelos R, Lorenzo-Martínez M, Rodríguez-Núñez A. Prevención del ahogamiento desde la educación para la salud escolar. Evaluación del proyecto piloto SOS 112 [Drowning prevention through school health education. Evaluation of the SOS 112 pilot project]. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2023, 97, e202306057.

- Barcala-Furelos R, Carbia-Rodríguez P, Peixoto-Pino L, Abelairas-Gómez C, Rodríguez-Núñez A. Implementation of educational programs to prevent drowning. What can be done in nursery school?. Med Intensiva. 2019, 43, 180-182. [CrossRef]

- Rahman F, Bose S, Linnan M, Rahman A, Mashreky S, Haaland B, Finkelstein E. Cost-effectiveness of an injury and drowning prevention program in Bangladesh. Pediatrics. 2012, 130, e1621-8. [CrossRef]

- Moran K, Stanley T. Toddler drowning prevention: teaching parents about water safety in conjunction with their child’s in-water lessons. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2006, 13, 254-256. [CrossRef]

- Sandomierski MC, Morrongiello BA, Colwell SR. S.A.F.E.R. Near Water: An Intervention Targeting Parent Beliefs About Children’s Water Safety. J Pediatr Psychol. 2019, 44, 1034-1045.

- Morrongiello BA, Sandomierski M, Spence JR. Changes over swim lessons in parents’ perceptions of children’s supervision needs in drowning risk situations: «His swimming has improved so now he can keep himself safe». Health Psychol Off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 2014, 33, 608-615.

- Farizan NH, Sutan R, Mani KK. Effectiveness of «Be SAFE Drowning Prevention and Water Safety Booklet» Intervention for Parents and Guardians. Iran J Public Health. 2020, 49, 1921-1930. [CrossRef]

- De Buck E, Vanhove AC, O D, Veys K, Lang E, Vandekerckhove P. Day care as a strategy for drowning prevention in children under 6 years of age in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021, 4, CD014955. 2021; 4, CD014955.

- Rampaso DA de L, Doria MAG, Oliveira MCM de, Silva GTR da. Teatro de fantoche como estratégia de ensino: relato da vivência [Puppet theatre as teaching strategy: a report of the experience]. Rev Bras Enferm. 2011, 64, 783-185. 2011; 64, 783–185.

- Pinedo del Olmo, C. O rato con as que quería aprender a nadar [The Rat Who Wanted to Learn to Swim]. Universidade de Vigo: Vigo, España, 2023.

- Rubio B, Yagüe F, Benítez MT, Esparza MJ, González JC, Sánchez F, Vila JJ, Mintegi S. Recomendaciones sobre la prevención de ahogamientos [Recommendations for the prevention of drowning]. An Pediatr. 2015, 82, 43.e1-5. 2015; 82, 43.e1–5.

- Barcala-Furelos R, Sanz-Arribas I, Sánchez-Lloria P, Izquierdo V, Martínez-Isasi S, Aranda-García S, Rodríguez-Núñez A, Muñoz-Barús I. Educación sanitaria ante las falsas creencias, mitos y errores en torno a los incidentes acuáticos. Una revisión conceptual basada en evidencias. [Health education in the face of false beliefs, myths and misconceptions surrounding aquatic incidents. An evidence-based conceptual review]. Educ Médica. 2023, 24.

- Morrison MI, Herath K, Chase C. Puppets for Prevention: «playing safe is playing smart». J Burn Care Rehabil. 1988, 9, 650-651.

- Synovitz LB. Using puppetry in a coordinated school health program. J Sch Health. 1999, 69, 145-147. [CrossRef]

- Rakoczy H. Puppet studies present clear and distinct windows into the child’s mind. Cogn Dev. 2022, 61, 101147. 2022; 61, 101147. [CrossRef]

- Stengelin R, Ball R, Maurits L, Kanngiesser P, Haun DBM. Children over-imitate adults and peers more than puppets. Dev Sci. 2023, 26, e13303. [CrossRef]

- Stallman RK, Moran K, Quan L, Langendorfer S. From Swimming Skill to Water Competence: Towards a More Inclusive Drowning Prevention Future. Int J Aquat Res Educ. 2017, 10. [CrossRef]

- Petrass LA, Blitvich JD. A Lack of Aquatic Rescue Competency: A Drowning Risk Factor for Young Adults Involved in Aquatic Emergencies. J Community Health. 2018, 43, 688-693. [CrossRef]

- Peden AE, Franklin RC. Causes of distraction leading to supervision lapses in cases of fatal drowning of children 0-4 years in Australia: A 15-year review. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020, 56, 450-456.

- Saluja G, Brenner R, Morrongiello BA, Haynie D, Rivera M, Cheng TL. The role of supervision in child injury risk: definition, conceptual and measurement issues. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2004, 11, 17-22. 2004; 11, 17–22. [CrossRef]

- Denny SA, Quan L, Gilchrist J, McCallin T, Shenoi R, Yusuf S, et al. Prevention of Drowning. Pediatrics. 2021, 148, e2021052227.

- Szpilman D, Webber J, Quan L, Bierens J, Morizot-Leite L, Langendorfer SJ, Beerman S, Løfgren B. Creating a drowning chain of survival. Resuscitation. 2014, 85, 1149-1152. [CrossRef]

- Franklin RC, Pearn JH. Drowning for love: the aquatic victim-instead-of-rescuer syndrome: drowning fatalities involving those attempting to rescue a child. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011, 47, 44-47. 2011; 47, 44–47. [CrossRef]

- Barcala-Furelos R, Graham D, Abelairas-Gómez C, Rodríguez-Núñez A. Lay-rescuers in drowning incidents: A scoping review. Am J Emerg Med. 2021, 44, 38-44. 2021; 44, 38–44. [CrossRef]

- Tobin JM, Ramos WD, Greenshields J, Dickinson S, Rossano JW, Wernicki PG, Markenson D, Vellano K, McNally B. Outcome of Conventional Bystander Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Cardiac Arrest Following Drowning. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2020, 35, 141-147. [CrossRef]

- Truhlář A, Deakin CD, Soar J, Khalifa GE, Alfonzo A, Bierens JJ, Brattebø G, Brugger H, Dunning J, Hunyadi-Antičević S, Koster RW, Lockey DJ, Lott C, Paal P, Perkins GD, Sandroni C, Thies KC, Zideman DA, Nolan JP. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 4. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation. 2015, 95, 148-201.

- Sobrasa – Sociedade Brasileira de Salvamento Aquatico. KIM na escola. Avaliable online: https://www.sobrasa.org. (accessed on 2 November 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).