Submitted:

10 November 2023

Posted:

13 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Well-being

1.2. Psychosocial work conditions and well-being among police officers

1.3. Perceived Job Stress as a Mediator

1.4. Job Satisfaction as a Mediator

1.5. Key variables in the present study

- Job demands

- Control

- Supervisor Support

- Colleague Support

- Effort

- Reward

- Overcommitment

- Bullying

- Role conflict

- Lack of consultation on change

- Positive well-being (happiness, life satisfaction, positive affect)

- Negative well-being (negative affect, anxiety, and depression).

- Physical health

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Psychosocial work conditions

2.2.2. Victimization

2.2.3. Perceived job stress

2.2.4. Job satisfaction

2.2.5. Psychological well-being

2.2.6. General physical health

2.2.7. Demographic and occupational variables

2.3. Analysis strategy

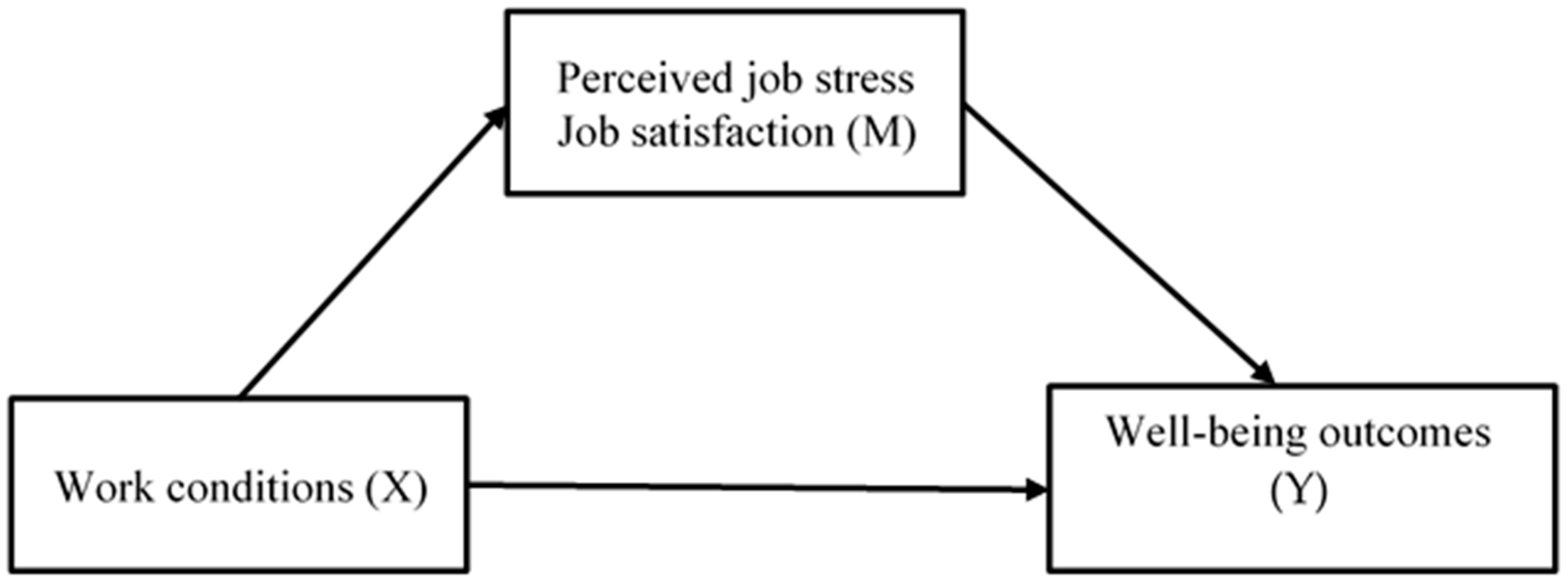

2.4. Mediation Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and occupational characteristics of the sample

3.2. Factor analysis

3.3. Direct Relationships

3.4. Mediation

3.4.1. Psychological distress

3.4.2. Positive Well-being

3.4.3. General physical health

4. Discussion

4.1. Direct Relationships

4.2. Indirect effects

4.3. Strengths and limitations of the research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Magnavita, N.; Capitanelli, I.; Garbarino, S.; Pira, E. Work-related stress as a cardiovascular risk factor in police officers: a systematic review of evidence. International Archives Occupational and Environmental Health 2018, 91, 377-89. [CrossRef]

- Purba, A.; Demou, E. The relationship between organizational stressors and mental well-being within police officers: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Violanti, J. M.; Charles, L. E.; McCanlies, E.; Hartley, T. A., Baughman, P.; Andrew, M. E.; Burchfiel, C. M. Police stressors and health: a state-of-the-art review. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 2017, 40(4), 642-656. [CrossRef]

- KKSSBaka, L. Types of job demands make a difference. Testing the job demand-control-support model among Polish police officers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2020, 31(18), 2265-2288. [CrossRef]

- Hansson, J.; Hurtig, A. K.; Lauritz, L. E.; Padyab, M. Swedish police officers' job strain, work-related social support and general mental health. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology 2017, 32, 128-137. [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.; Chen, M.; Toh, S. M.; Ang, J. Roles of effort and reward in well-being for police officers in Singapore: The effort-reward imbalance model. Social Science & Medicine 2021, 277, 113878. [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, S.; Cuomo, G.; Chiorri, C.; Magnavita, N. Association of work-related stress with mental health problems in a special police force unit. BMJ Open 2013, 3(7), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Rostami, A.; Ghazinour, M.; Burman, M.; Hansson, J. Job satisfaction among Swedish police officers: The role of work-related stress, gender-based and sexual harassment. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10, 889671. [CrossRef]

- Houdmont, J.; Jachens, L.; Randall, R.; Colwell, J. English rural policing: job stress and psychological distress. Policing: An International Journal 2021, 44(1), 49-62. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.V; Smith, A.P. Occupational stress, coping, and mental health in Jamaican police officers. Occupational Medicine 2016, 66(6). [CrossRef]

- Oliver, H.; Thomas, O.; Neil, R.; Moll, T.; Copeland, R. J. Stress and psychological well-being in British police force officers and staff. Current Psychology 2022, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M.; Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology 2001, 52(1), 141-166. [CrossRef]

- Grawitch, M. J.; Gottschalk, M.; Munz, D. C. The path to a healthy workplace: A critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 2006, 58(3), 129. [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, E. J. K.; Chaplin, K. S.; Allen, P. H.; Smith, A. P. What is a good job? Current perspectives on work and improved health and well-being. The Open Occupational Health & Safety Journal 2010, 2, 9-15. [CrossRef]

- Hart, P. M.; Cooper, C. L. Occupational stress: Toward a more integrated framework. In Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology, Anderson, N., Ones D.S., Sinangil H.K., Viswesvaran, C., Eds; Sage: London, 2001; Vol 2, pp.93-114.

- Hart, P.M., Cotton, P. Conventional wisdom is often misleading: Police stress within an organizational health framework. In Occupational Stress in the Service Professions, Dollard, M.F., Winefiled, A.H., Winefiled H.R., Eds. Taylor & Francis: London, 2002, pp.130-138.

- Mark, G.M.; Smith, A.P. Stress models: A review and suggested direction. In Occupational Health Psychology Houdmont, J., Leka, S, Eds.; Nottingham University Press, UK, 2008; pp. 111-144.

- Margrove, G.; Smith, A.P. The Demands-Resources-Individual Effects (DRIVE) Model: Past, Present and Future Research Trends. Chapter 2, in "Complexities and Strategies of Occupational Stress in the Dynamic Business World". Edited by Dr Adnam ul Haque. IGI Global. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.M. Researching and developing mental health and well-being assessment toll for supporting employers and employees in Wales. Doctoral dissertation. Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2014.

- Williams, G.M.; Smith, A. P. A holistic approach to stress and well-being. Part 6: The Well-being Process Questionnaire (WPQ Short Form). Occupational Health [At Work] 2012, 9(1), 29-31.

- Huddleston, L.; Stephens, C.; Paton, D. An evaluation of traumatic and organizational experiences on the psychological health of New Zealand police recruits. Work 2007, 28(3), 199-207.

- Wang, Z.; Inslicht, S. S.; Metzler, T. J.; Henn-Haase, C.; McCaslin, S. E.; Tong, H; Marmar, C. R. A prospective study of predictors of depression symptoms in police. Psychiatry Research 2010, 175(3), 211-216. [CrossRef]

- van der Velden, P. G.; Kleber, R. J.; Grievink, L.; Yzermans, J. C. Confrontations with aggression and mental health problems in police officers: The role of organizational stressors, life-events and previous mental health problems. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 2010, 2(2), 135-144. [CrossRef]

- Janzen, B.L.; Muhajarine, N.; Kelly, I.W. Work-family conflict, and psychological distress in men and women among Canadian police officers. Psychological Reports 2007,100(2), 556-562. [CrossRef]

- Violanti J. M.; Mnatsakanova, A.; Andrew, M. E.; Allison, P.; Gu, J. K.; Fekedulegn, D. Effort–reward imbalance and overcommitment at work: associations with police burnout. Police Quarterly 2018, 21(4), 440-460. [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, S.; Cuomo, G.; Chiorri, C.; Magnavita, N. Association of work-related stress with mental health problems in a special police force unit. BMJ Open 2013, 3(7), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Houdmont, J.; Randall, R.; Kerr, R.; Addley, K. Psychosocial risk assessment in organizations: Concurrent validity of the brief version of the management standards indicator tool. Work & Stress 2013, 27(4), 403-412. [CrossRef]

- Dewe, PJ; O'Driscoll, M.P.; Cooper, C.L. Theories of psychological stress at work. In Handbook of Occupational Health and Wellness, Handbooks in Health, Work, and Disability; Gatchel R.J, Schultz, I, Eds.; Springer Science: New York, 2012, pp.23-38.

- Lazarus, R. S. Theory-based stress measurement. Psychological Inquiry 1990, 1(1), 3-13. [CrossRef]

- Cox, T., Griffiths, A. (2010). Work-related stress, A theoretical perspective. In Occupational Health Psychology, Leka, S., Houdmont, J., Eds; Blackwell: Malden, MA, 2010, pp. 31-56.

- Allisey, A. F.; Noblet, A. J.; Lamontagne, A. D.; & Houdmont, J. Testing a model of officer intentions to Quit: The mediating effects of job stress and job satisfaction. Criminal Justice and Behavior 2013, 41 (6), 751-771. [CrossRef]

- Mark, G.; Smith, A. P. Occupational stress, work conditions, coping, and the mental health of nurses. British Journal of Health Psychology 2012, 17(3), 505-521. [CrossRef]

- Locke, E. A. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology 1976, 1, 1297-1343.

- Ercikti, S.; Vito, G. F.; Walsh, W. F.; Higgins, G. E. Major determinants of job satisfaction among police managers. Southwest Journal of Criminal Justice 2011, 8(1), 97-111.

- Miller, H. A.; Mire, S.; Kim, B. Predictors of job satisfaction among police officers: Does personality matter? Journal of Criminal Justice 2009, 37(5), 419-426. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. R. Police officer job satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis. Police Quarterly 2012, 15(2), 157-176. [CrossRef]

- Demirkol, I. C. Predictors of job satisfaction among police officers: a test of goal-setting theory. Police Practice and Research 2021, 22(1), 324-336. [CrossRef]

- Paoline III, E. A.; Gau, J. M. An empirical assessment of the sources of police job satisfaction. Police Quarterly 2020, 23(1), 55-81. [CrossRef]

- Tomaževič, N.; Seljak, J.; Aristovnik, A. Factors influencing employee satisfaction in the police service: the case of Slovenia. Personnel Review 2014, 43(2), 209-227. [CrossRef]

- Viegas, V.; Henriques, J. Job stress and work-family conflict as correlates of job satisfaction among police officials. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology 2021, 36(2), 227-235. [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. M.; Smith, A. P. Using single-item measures to examine the relationships between work, personality, and well-being in the workplace. Psychology 2016, 7(6), 753-767. [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implication for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly 1979, 24(2), 285-308. [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J.; Siegrist, K.; Weber, I. Sociological concepts in the etiology of chronic disease: The case of ischemic heart disease. Social Science & Medicine 1986, 22(2), 247-253. [CrossRef]

- Cheong, J.; Yun, I. Victimization, stress and use of force among South Korean police officers. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 2011, 34(4), 606-624. [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, P., Eisner, M. Violence between the police and the public influences work-related stress, job satisfaction, burnout, and situational factors. Criminal Justice and Behavior 2006, 33(5), 613-645. [CrossRef]

- Calnan, M.; Wadsworth, E.; May, M.; Smith, A.; Wainwright, D. Job strain, effort-reward imbalance, and stress at work: Competing or complementary models? Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 2004, 32(2), 84-93. [CrossRef]

- Warr, P.; Cook, J.; Wall, T. Scales for the measurement of some work attitudes and aspects of psychological well-being. Journal of Occupational Psychology 1979, 52(2), 129-148. [CrossRef]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2007, 5:63. [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A. Just one question: If one question works, why ask several? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2005, 59(5), 342-345.

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, LS Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.) Boston: Pearson, 2013.

- Hayes, A. F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs 2009, 76(4), 408-420. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.V. Beyond the Frontline: Occupational stress and well-being in Jamaican police officers. Doctoral Dissertation. Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2017.

- Tyagi, A.; Lochan Dhar, R. Factors affecting health of the police officials: Mediating role of job stress. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 2014, 37(3), 649-664. [CrossRef]

- Brough, P.; Frame, R. Predicting police job satisfaction and turnover intentions: The role of social support and police organizational variables. New Zealand Journal of Psychology 2004, 33(1), 8-18.

| Gender (N = 578) | Male | N=427 | 74% |

| Female | 151 | 26 | |

| Age (N = 578) | ≤ 28 | 200 | 35 |

| 29-35 | 197 | 34 | |

| 36+ | 181 | 31 | |

| Education (N = 574) | Secondary | 330 | 58 |

| Diploma | 117 | 20 | |

| Associate degree | 23 | 4 | |

| Bachelor's | 99 | 17 | |

| Master's | 5 | 1 | |

| Relationship status (N = 578) | Single | 122 | 21 |

| In a relationship | 257 | 45 | |

| Married | 164 | 28 | |

| separated/divorced/ widowed |

35 | 6 | |

| Rank (N = 578) | Constable | 362 | 63 |

| Corporal | 128 | 22 | |

| Sergeant | 62 | 11 | |

| Inspector | 26 | 4 | |

| Years of service (N = 578) | ≤ 5 | 246 | 43 |

| 6-12 | 157 | 27 | |

| 13+ | 175 | 30 |

| Independent variables | Perceived job Stress | Job Satisfaction | Psychological Distress | Positive Well-being | General Health | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 β | Step 2 β | Step 1 β | Step 2 β | Step 1 β | Step 2 β | Step 1 β | Step 2 β | Step 1 β | Step 2 β | |

| Demographics | ||||||||||

| Gender | 0.02 | 0.03 | -0.04 | -0.07 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.00 | -0.03 |

| Rank | -0.03 | -0.04 | .16** | .14** | -0.07 | -0.08 | 0.10 | 0.09 | -0.01 | -0.02 |

| Relationship status | 0.04 | 0.05 | -0.07 | -.08* | 0.03 | 0.05 | -0.04 | -0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Years of service | 0.10 | .15** | 0.07 | -0.02 | -0.07 | -0.01 | 0.11 | 0.06 | .17** | .12* |

| Work factors | ||||||||||

| Neg. work conditions | .38*** | -.29** | .36*** | -.19** | -.24** | |||||

| Work support | -0.05 | .25*** | -.14*** | .20*** | 0.06 | |||||

| Pos. work conditions | -.09* | 20*** | -0.08 | .11** | .12** | |||||

| Victimisation | .13*** | -.12** | .10* | -0.06 | -.13** | |||||

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| ΔR2 | .21*** | .28*** | .21*** | .13*** | .13*** | |||||

| Perceived Job Stress | Job Satisfaction | |||

| Total effects |

Direct effects |

Indirect Effects | Indirect effects | |

| Negative Work conditions |

.24*** | .21*** | .02, CI [.00, .05]a | .01, CI [-.01, .03] |

| Work support |

-.10*** | -.09** | -.00, CI [-.01, .01] | -.01, CI [-.03, .01] |

| Positive Work conditions |

-.10 | -.08 | -.01, CI [-.03, -.00]a | -.01, C. [-.04, .01] |

| Victimization | 1.13* | .95* | .13, CI [.01, .34]a | .05, CI [-.07, .25] |

| Perceived Job Stress | Job Satisfaction | |||

| Total effects | Direct effects | Indirect Effects | Indirect effects | |

| Negative job | ||||

| characteristics | -.21*** | -.16*** | -.01, CI [-.04, .03] | -.05, CI [-.09, - 01]a |

| Work support | .24*** | .20*** | .00, CI [-.00, .01] | .04, CI [.01, .08]a |

| Positive job | ||||

| characteristics | .24** | .18* | .00, CI [-.02, .02] | .06, CI [.02, .13]a |

| Victimization | -1.09 | -.73 | -.03, CI [-.25, .20] | -.33, CI [-.77, -.08]a |

| Perceived Job Stress | Job Satisfaction | |||

| Total effects |

Direct effects |

Indirect Effects | Indirect effects | |

| Negative work | ||||

| conditions | -.06*** | -.04*** | -.01, CI [-.02, -.00]a | -.01, CI [-.02, - .00]a |

| Work support | .02 | .01 | .00, CI [-.00, .00] | .01, CI [.00, .02]a |

| Positive workconditions | .06** | .04* | .00, CI [.00, .01]a | .01, CI [.01, .03]a |

| Victimization | -.56** | -.44* | -.05, CI [-.13, -.01]a | -.08, CI [-.17, -.02]a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).