Submitted:

13 November 2023

Posted:

13 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Language Skills

1.2. Designations for Idiopathic Language Impairment

1.3. ADHD

1.4. Comorbidity

1.5. The Current Review

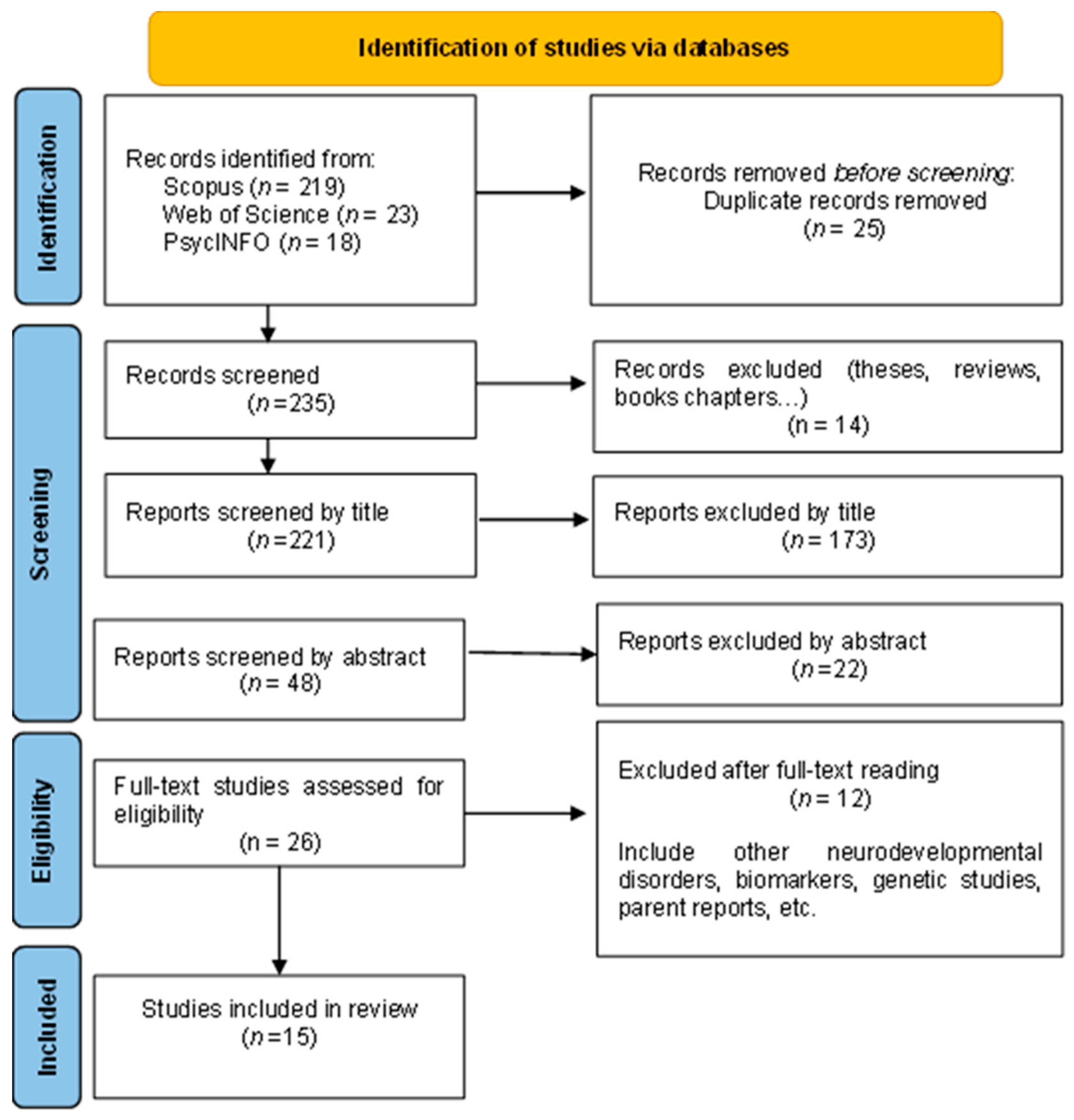

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Criteria

2.4. Study Selection

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leonard, L.B. 200-year history of the study of childhood language disorders of unknown origin: Changes in terminology. Perspect ASHA Spec Interest Groups 2020, 5, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, K.K. How we fail children with developmental language disorder. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch, 2020; 51, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D.V. Which neurodevelopmental disorders get researched and why? PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmond, S.M. Clinical intersections among idiopathic language disorder, social (pragmatic) communication disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2020, 63, 3263–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmond, S.M. Markers, models, and measurement error: Exploring the links between attention deficits and language impairments. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2016, 59, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanford, E.; Delage, H. The contribution of visual and linguistic cues to the production of passives in ADHD and DLD: Evidence from thematic priming. Clin Linguist Phon 2021, 37, 17–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiswick, B. R., Miller, P. W. Language Skill Definition: A Study of Legalized Aliens. Int Migr Rev 1998, 32, 877–900. [CrossRef]

- Koutsoftas, A.D. School–age language development: Application of the five domains of language across four modalities. N. Capone-Singleton and BB Shulman (Eds.), Language development: Foundations, processes, and clinical applications, 2013; pp.,215-229.

- Riad, R., Allodi, MW, Siljehag, E., Bölte, S. Language skills and well-being in early childhood education and care: A crosssectional exploration in a Swedish context. Front Educ 2023, 8, 963180. [CrossRef]

- Parks, K. M., Hannah, K. E., Moreau, C. N., Brainin, L., Joanisse, M. F. Language Abilities in Children and Adolescents with DLD and ADHD: A Scoping Review. J Commun Disord 2023, 106, 106381. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, D. V. Ten questions about terminology for children with unexplained language problems. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2014, 49, 381–415. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D. V., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., Greenhalgh, T., Adams, C. Phase 2 of CATALISE: A multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2017, 58, 1068–1080. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahufinger, N., Guerra, E., Ferinu, L., Andreu, L. and Sanz-Torrent, M. Cross-situational statistical learning in children with developmental language disorder. Lang Cogn Neurosci 2021, 36, 1180–1200. [CrossRef]

- Sansavini, A.; Favilla, M.E.; Guasti, M.T.; Marini, A.; Millepiedi, S.; Di Martino, M.V.; Vecchi, S.; Battajon, N.; Bertolo, L.; Capirci, O. Developmental Language Disorder: Early Predictors, Age for the Diagnosis, and Diagnostic Tools. A Scoping Review. Brain Sci 2021, 11, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, S., Tomblin, B., Law, J., Mckean, C., Mensah, F.K., Morgan, A., Goldfeld, S., Nicholson, J.M., Wake, M. Specific language impairment: A convenient label for whom? Int J Lang Commun Disord 2014, 49, 416–451. [CrossRef]

- Stanford, E., Delage, H. Executive functions and morphosyntax: Distinguishing DLD from ADHD in French-speaking children. Front Psychol 2020, 11, 551824. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korrel, H., Mueller, K. L., Silk, T., Anderson, V., Sciberras, E. Research Review: Language problems in children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder–a systematic meta-analytic review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2017, 58, 640–654. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisci, G., Caviola, S., Cardillo, R., Mammarella, I. C. Executive functions in neurodevelopmental disorders: Comorbidity overlaps between attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder and specific learning disorders. Front Human Neurosci 2021, 15, 594234. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Wafa, H. E. A., Ghobashy, S. A. E. L., Hamza, A. M. A comparative study of executive functions among children with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder and those with learning disabilities. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 2020, 27, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P. L., Li, H., Farkas, G., Cook, M., Pun, W. H., Hillemeier, M. M. Executive functioning deficits increase kindergarten children's risk for reading and mathematics difficulties in first grade. Contemp Educ Psychol 2017, 50, 23–32. [CrossRef]

- Redmond, S. M., Ash, A. C., Hogan, T. P. Consequences of co-occurring attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on children's language impairments. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch 2015, 46, 68–80. [CrossRef]

- Morsanyi, K., van Bers, B. M., McCormack, T., McGourty, J. The prevalence of specific learning disorder in mathematics and comorbidity with other developmental disorders in primary school-age children. Br J Psychol 2018, 109, 917–940. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C., Areces, D., García, T., Cueli, M., Gonzalez-Castro, P. Neurodevelopmental disorders: An innovative perspective via the response to intervention model. World J Psychiatr 2021, 11, 1017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitin, R., Shaw, D. M., Rocha, D. B., Walters, C. E., Jr, Chabris, C. F., Camarata, S. M., Gordon, R. L., Below, J. E. Association of Developmental Language Disorder With Comorbid Developmental Conditions Using Algorithmic Phenotyping. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2248060. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adlof, S.M. Promoting reading achievement in children with developmental language disorders: What can we learn from research on specific language impairment and dyslexia? J Speech Lang Hear Res 2020, 63, 3277–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanoudis, G. C., Papadopoulos, T. C., Spyrou, S. Specific language impairment and reading disability: Categorical distinction or continuum? J Learn Disabil 2019, 52, 3–14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, E., Gathercole, S., Astle, D., Calm Team, Holmes, J. Language problems and ADHD symptoms: How specific are the links? Brain Sci 2016, 6, 50. [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Cartes, P.; Moreno-Garcia, I. Linguistic competences at schools. Comparison of students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, specific language impairment and typical development. Rev de Pedagog 2021, 79, 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, D., Varela, M. M. S. Language and school performance in children with diagnosis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Rev Mex de Neurocienc 2017, 18, 89–99.

- Page, M.J; McKenzie, J.E; Bossuyt, P.M.; Bouton, I.; Hoffmann, T.C; Mulrow, C.D; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 2021; 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinton, B., Fujiki, M., Asai, N. The Ability of Five Children With Developmental Language Disorder to Describe Mental States in Stories. Commun Disord Q 2019, 40, 109–116. [CrossRef]

- Delgado, V. G., Herrera, D. P., Ruiz, F. B. Metapragmatic awareness in children between 7 and 12 years-old, with specific language disorder, attention deficit disorder and typical language development. Pragmalinguistica 2018, 26, 109–130. [CrossRef]

- El Sady, S. R., Nabeih, A. A. S., Mostafa, E. M. A., Sadek, A. A. Language impairment in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in preschool children. Egypt J Med Hum Genet 2013, 14, 383–389. [CrossRef]

- Gooch, D., Sears, C., Maydew, H., Vamvakas, G., Norbury, C. Does Inattention and Hyperactivity Moderate the Relation Between Speed of Processing and Language Skills? Child Dev 2019, 90, E565–E583. [CrossRef]

- Helland, W. A., Helland, T., Heimann, M. Language profiles and mental health problems in children with specific language impairment and children with ADHD. J Atten Disord 2014, 18, 226–235. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaganovich, N., Schumaker, J., Christ, S. Impaired audiovisual representation of phonemes in children with developmental language disorder. Brain Sci 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S., Thornton, V., Marks, D. J., Rajendran, K., Halperin, J. M. Early language mediates the relations between preschool inattention and school-age reading achievement. Neuropsychol 2016, 30, 398–404. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ralli, A. M., Chrysochoou, E., Roussos, P., Diakogiorgi, K., Dimitropoulou, P., Filippatou, D. Executive function, working memory, and verbal fluency in relation to non-verbal intelligence in greek-speaking school-age children with developmental language disorder. Brain Sci, 2021; 11. [CrossRef]

- Staikova, E., Gomes, H., Tartter, V., McCabe, A., Halperin, J. M. Pragmatic deficits and social impairment in children with ADHD. J Chil Psychol Psychiatry 2013, 54, 1275–1283. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassiliu, C., Mouzaki, A., Antoniou, F., Ralli, A., Diamanti, V., Papaioannou, S., Katsos, N. Development of Structural and Pragmatic Language Skills in Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Commun Disord Q 2023, 44, 207–218. [CrossRef]

- Zenaro, M. P., Rossi, N. F., Souza, A. L. D. M. d., Giacheti, C. M. Oral narrative structure and coherence of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. CoDAS 2019, 31, 1–8.

- Marini, A., Piccolo, B., Taverna, L., Berginc, M., Ozbič, M. The complex relation between executive functions and language in preschoolers with Developmental Language Disorders. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1772:1–1177:14.

- Park, J., Miller, C. A., Mainela-Arnold, E. Processing speed measures as clinical markers for children with language impairment. J Speech, Lang Hear Res 2015, 58, 954–960. [CrossRef]

- Peter, M. S., Durrant, S., Jessop, A., Bidgood, A., Pine, J. M., Rowland, C. F. Does speed of processing or vocabulary size predict later language growth in toddlers? Cogn Psychol 2019, 115, 101238:1–101238. [CrossRef]

- Shokrkon, A., Nicoladis, E. The directionality of the relationship between executive functions and language skills: A literature review. Front Psychol, 2022; 13, 848696. [CrossRef]

- Slobodin, O., Davidovitch, M. Gender differences in objective and subjective measures of ADHD among clinic-referred children. Front Hum Neurosci 2019, 13, 441. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakhlin, N., Kornilov, S. A., Grigorenko, E. L. Gender and agreement processing in children with Developmental Language Disorder. J Child Lang 2014, 41, 241–274. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilosi, A. M., Brovedani, P., Cipriani, P., Casalini, C. Sex differences in early language delay and in developmental language disorder. J Neurosci 2023, 101, 654–667. [CrossRef]

- Vermeij, B. A., Wiefferink, C. H., Knoors, H. E. T., Scholte, R. H. Effects in language development of young children with language delay during early intervention. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2023, 103, 106326:1–106326:12. [CrossRef]

| Author | Year | Journal | Country | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brinton et al. [32] | 2018 | Communication Disorders Quarterly | USA | English |

| Delgado et al. [33] | 2018 | Pragmalingüística | Chile | Spanish |

| El Sady et al. [34] | 2013 | The Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics | Egypt | Arabic |

| Gooch et al. [35] | 2019 | Child Development | UK | English |

| Helland et al. [36] | 2014 | Journal of Attention Disorders | Norway | Norwegian |

| Kaganovich et al. [37] | 2021 | Brain Sciences | USA | English |

| O'Neil et al. [38] | 2016 | Neuropsychology | USA | English |

| Paredes-Cartes y Moreno-Garcia [29] | 2021 | Revista Española de Pedagogía | Spain | Spanish |

| Ralli et al. [39] | 2021 | Brain Sciences | Greece | Greek |

| Redmond et al. [22] | 2015 | Language speech and hearing services in schools | USA | English |

| Staikova et al. [40] | 2013 | The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry | USA | English |

| Stanford y Delage [6] | 2021 | Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics | Switzerland | French |

| Stanford y Delage [17] | 2020 | Frontiers in Psychology | Switzerland | French |

| Vassiliu et al. [41] | 2022 | Communication Disorders Quarterly | Greece | Greek |

| Zenaro et al. [42] | 2019 | Communication Disorders, Audiology and Swallowing | Brazil | Portuguese |

| Author(s) | Sample | Comorbidity Condition | Instrument(s) | Measures | Summary of Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brinton et al. (2018) [31] | Age range: 5-10 years Group(s): n =5 DLD Gender: 2 females/ 3 males |

No |

Language skills: Edmonton Narrative Norms Instrument (ENNI) |

Narrative skills: internal response expressions in spontaneous and prompted condition. | Production and accuracy of internal plan Spontaneous condition: Expressions were appropriate. Prompted condition: high production but the accuracy decreased. Production and accuracy of emotion words: Spontaneous condition: children describe few emotions. Prompted condition: greater variety of emotion words. |

| Delgado et al. (2018) [33] | Age range: 7 -12 years Group(s): n = 6 DLD n = 6 ADHD n = 6 TD |

No |

Language skills: Metapragmatic Consciousness Assessment Test |

Metapragmatic Awareness | TD group had the highest results.DLD group had the worst outcome. Age effect in the ADHD group Significant differences between the DLD group and the TD group. |

| El Sady et al. (2013) [34] | Age range: 3 – 6 years Group(s): n = 36 DLD + ADHD n = 25 DLD Gender: 9 females /27 males 9 females/ 16 males |

Yes |

Language skills: Language testing of Arabic speaking children |

Receptive age Expressive age Semantic Syntax and phonology Pragmatics Receptive age quotient Expressive age quotient |

Significant difference in the receptive age and the receptive age quotient: DLD + ADHD children had poorer reception than DLD + no ADHD children. Hyperactivity was the most important factor affecting language in ADHD. |

| Gooch et al. (2019) [35] | Age range: 5 -8 years Group(s): n = 129 DLD n = 370 TD |

No |

Language skills: Expressive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test (EOWPVT) Receptive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test (ROWPVT) School-Age Sentence Imitation Test-English 32 (SASIT-E32) Test for Reception of Grammar (TROG) Assessment of Comprehension and Expression (ACE) Executive functions: Rapid Automatized Naming (RAN) Visual Search (Apples Task) Coding (WPPSI-III) Simple Reaction Time |

VocabularyGrammar Narrative recall and comprehension Speed of processing: |

Children with DLD score lower on Speed of Processing (SOP) than their TD peers. The DLD group have elevated symptoms of inattention/hyperactivity commonly associated with ADHD. Symptoms of inattention/hyperactivity moderate the effect of SOP on language, but SOP does not predict later language in formal schooling |

| Helland et al. (2014) [36] | Age range: 6- 12 years Group(s): n = 19 DLD n = 21 ADHD n = 19 TD Gender: 2 females/17 males3 females/ 21 males 2 females/17 males |

No |

Language skills: Children’s Communication Checklist–Second Edition (CCC-2) |

Speech, syntax, semantics, coherence, inappropriate initiation, stereotyped language, use of context, nonverbal communication, social relations, interests. | Communication impairments were as pronounced in the ADHD group as in the DLD group. The ADHD group was as impaired as the DLD group on the scale measuring semantics. Language structure was more impaired in the DLD group. The ADHD group was more impaired on the interest scale. |

| Kaganovich et al. (2021) [37] | Age range: 7-13 years Group(s): n = 18 DLD n = 18 TD Gender: 5 females/13 males7 females/ 11 males |

No |

Language skills: Photographic Expressive Language Test—2nd Edition (SPELT-II) Photographic Expressive Language Test—Preschool 2 (SPELT-P2) Core Language Score (Concepts and Following Directions, Recalling Sentences, Formulated, Sentences, Word Structure and Word Classes-2 Total (WC-2, 9–12-year-olds only), and Word Definitions (WD, 13-year-olds only). Executive Functions: Verbal working memory and nonword repetition test. Number Memory Forward. Number Memory Reversed subtests of the Test of Auditory Processing. Skills—3rd edition (TAPS-3). |

General linguistic aptitude Working memory |

Children with TD, but not children with DLD, can incorporate visual information into long- term phonemic representations |

| O’Neil et al. (2016) [38] | Age range: 4 – 8 years Group(s): n = 90 ADHD n = 60 TD |

No | Language domain of the NEPSY. Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Second Edition (WIAT-II): Word Reading, Pseudoword, Decoding, Reading Comprehension, and Spelling subtest. Vanderbilt Assessment Scale, Teacher Informant: Reading and Written Expression performance in school. |

Language (NEPSY) Reading Writing |

At 4-6 years of age, there was no significant association between the severity of pre-schoolers’ hyperactivity/impulsivity and their language skills. at 4-6 years. At 8 years, language ability mediated the pathway from preschool inattention (but not hyperactivity/impulsivity). |

| Paredes-Cartes y Moreno-Garcia (2021) [29] | Age range: 7 – 12 years Group(s): n = 47 DLD n = 48 ADHD n = 47 TD Gender: 20 females/27 males 39 females/ 9 males 19 females/ 28 males |

No |

Language skills: The Objective and Criterion-referenced Language Suite (BLOC) The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT-III) |

Language: morphology, syntax, semantics and pragmatics. Receptive vocabulary |

Significant differences were found between the three groups in semantic and pragmatic language skills. Children with ADHD had fewer problems with semantic competence than children with DLD. Pragmatic competence: ADHD group had lower scores than the DLD group and the control group. |

| Ralli et al. (2021) [39] | Age range: 8 yearsGroup(s): n = 29 DLD n = 29 TD Gender: 14 females/ 15 males 17 females/ 12 males |

No |

Language skills: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-WISC III: vocabulary scale. Athena Test: the sentence completion subtest. Executive functions: - Working Memory Test Battery for Children. - n-back task. - Flanker task. - Borella’s task. - “How many—What number task” - Semantic fluency test. Phonological fluency test. |

Expressive vocabulary Sentence completion Working memory Updating Inhibition Switching Verbal fluency Phonological fluency |

Children with DLD were outperformed by their TD peers on measures of WM capacity, updating, monitoring (mixing cost) and verbal fluency (phonological and semantic). |

| Redmond et al. (2015) [22] | Age range: 7 – 9 years Group(s): n = 19 DLD n = 19 ADHD+DLD n = 19 TD Gender: 10 females / 9 males |

Yes |

Language skills: English Nonword Repetition Task. Test of Early Grammatical Impairment (TEGI). |

Nonword repetition Sentence recall Tense marking |

No significant differences were found between the ADHD and DLD + ADHD groups. A modest positive correlation was found between the severity of ADHD symptoms and their sentence recall performance: children with higher levels of ADHD symptoms performed better than those with lower levels. |

| Staikova et al. (2013) [40] | Age range: 7 – 11 years Group(s): n = 28 ADHDn = 35 TD |

No |

Language skills: Children's Communicative Checklist, Second Edition (CCC-2). Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (CASL). Test of Pragmatic Language, Second Edition (TOPL-2) Narrative Assessment Profile: Discourse Analysis (NAP) Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals, Fourth Edition (CELF-4) |

Pragmatic language General language |

Children with ADHD had poorer pragmatic language skills relative to peers across all measures, even after controlling for general language abilities. |

| Stanford and Delage (2021) [6] | Age range: 8 years Group(s): n = 20 DLD n = 20 ADHD n = TD |

No |

Language skills: Bilan Informatisé du Langage Oral (BILO) Phonological loop. Executive functions: Conners CBRS: inattention, hyperactivity. |

Syntax selective attention, central executive, processing speed, attentional flexibility. |

Children with DLD were more sensitive than children with ADHD to visual cues (DLD > ADHD), which were more implicit than the linguistic cues and may have required more attentional resources. For linguistic cues, which required syntactic processing, the opposite pattern was true (ADHD > DLD). |

| Stanford and Delage (2020) [17] | Age range: 8 yearsGroup(s): n = 20 DLD n = 20 ADHD n = 20 TD |

No |

Language skills: Bilan Informatisé du Langage Oral (BILO). Probe test. Executive functions: Sky Search task (TEA-ch)Digit recall task (WISC-IV) Opposite Worlds task (TEA-ch) |

MorphosyntaxSelective attention Working memory Attention shifting |

Different EF and morphosyntactic profiles in children with ADHD and DLD. ADHD group: higher-order EF weakness and difficulty with the omnibus morphosyntax task. DLD group: lower- and higher-order limitations and struggled with both morphosyntax tasks. Deficits in morphosyntax are not characteristic of ADHD: their performance can mimic morphosyntactic impairment. |

| Vassiliu et al. (2022) [41] | Age range: 4 – 8 yearsGroup(s): n = 25 DLD n =29 ADHD n = 29 TD Gender: 8 females /17 males 11 females / 18 males 10 females / 19 males |

No |

Language skills: Logometro tasks |

Structural language Vocabulary: receptive and expressive Morphosyntax: expressive and receptivePragmatic language |

ADHD children face difficulties with language skills and especially with structural language: they performed significantly lower than their TD peers but significantly higher than the DLD group. In pragmatics, ADHD children performed numerically lower than any other group but no statistical significance was found. |

| Zenaro et al. (2019) [42] | Age range: 6 – 10 years Group(s): n = 20 ADHD n = 20 TD Gender: 6 females /14 males |

No |

Language skills: Frog, Where are you? |

Narrative skills | The ADHD group presented lower scores on the structural elements of “theme/ topic” and “outcome” and a narrative with a lower degree of coherence than the TD group. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).