Submitted:

13 November 2023

Posted:

13 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study population

2.2. SNP identification

2.3. Measurement of plasma OPN

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. OPN and CD44 SNPs and survival outcomes

3.2. Cumulative analysis

3.3. OPN haplotypes and clinical outcome

3.4. OPN levels and SNPs

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willers, H.; Azzoli, C.G.; Santivasi, W.L.; Xia, F. Basic mechanisms of therapeutic resistance to radiation and chemotherapy in lung cancer. Cancer J. 2013, 19, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorman, H.R.; Poschel, D.; Klement, J.D.; Lu, C.; Redd, P.S.; Liu, K. Osteopontin: A Key Regulator of Tumor Progression and Immunomodulation. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, G.F.; Lett, G.S.; Haubein, N.C. Osteopontin is a marker for cancer aggressiveness and patient survival. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 103, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Lin, D.; Yuan, J.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, H.; Sun, W.; Han, N.; Ma, Y.; Di, X.; Gao, M.; Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, S.; Gao, Y. Overexpression of osteopontin is associated with more aggressive phenotypes in human non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 4646–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.M.; Li, J.; Yan, M.X.; Liu, L.; Jia, D.S.; Geng, Q.; Lin, H.C.; He, X.H.; Li, J.J.; Yao, M. Integrative analyses identify osteopontin, LAMB3 and ITGB1 as critical pro-metastatic genes for lung cancer. PLoS One 2013, 8, e55714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.S.; You, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.F.; Wang, C.L. Osteopontin knockdown suppresses non–small cell lung cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Chin. Med. J. (Engl) 2013, 126, 1683–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štemberger, C.; Matušan-Ilijaš, K.; Avirović, M.; Bulat-Kardum, L.; Ivančić, A.; Jonjić, N.; Lučin, K. Osteopontin is associated with decreased apoptosis and αv integrin expression in lung adenocarcinoma. Acta Histochem. 2014, 116, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rud, A.K.; Boye, K.; Oijordsbakken, M.; Lund-Iversen, M.; Halvorsen, A.R.; Solberg, S.K.; Berge, G.; Helland, A.; Brustugun, O.T.; Mælandsmo, G.M. Osteopontin is a prognostic biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.S.; Kim, H.J.; Chang, J.; Ahn, C.M.; Kim, S.K. Elevated circulating level of osteopontin is associated with advanced disease state of non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2007, 57, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, P.C.; Redman, M.W.; Chansky, K.; Williamson, S.K.; Farneth, N.C.; Lara, P.N. Jr.; Franklin, W.A.; Le, Q.T.; Crowley, J.J.; Gandara, D.R.; SWOG. Lower osteopontin plasma levels are associated with superior outcomes in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy: SWOG Study S0003. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 4771–4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostheimer, C.; Bache, M.; Güttler, A.; Reese, T.; Vordermark, D. Prognostic information of serial plasma osteopontin measurement in radiotherapy of non-small-cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwinski, R.; Giglok, M.; Galwas-Kliber, K.; Idasiak, A.; Jochymek, B.; Deja, R.; Maslyk, B.; Mrochem-Kwarciak, J.; Butkiewicz, D. Blood serum proteins as biomarkers for prediction of survival, locoregional control and distant metastasis rate in radiotherapy and radio-chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimba, E.R.P.; Brum, M.C.M.; Nestal De Moraes, G. Full-length osteopontin and its splice variants as modulators of chemoresistance and radioresistance (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 54, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behbahani, R.G.; Danyaei, A.; Teimoori, A.; Neisi, N.; Tahmasbi, M.J. Breast cancer radioresistance may be overcome by osteopontin gene knocking out with CRISPR/Cas9 technique. Cancer Radiother. 2021, 25, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, A.; Nokin, M.J.; Leroi, N.; Lallemand, F.; Lambert, J.; Goffart, N.; Roncarati, P.; Bianchi, E.; Peixoto, P.; Blomme, A.; Turtoi, A.; Peulen, O.; Habraken, Y.; Scholtes, F.; Martinive, P.; Delvenne, P.; Rogister, B.; Castronovo, V.; Bellahcène, A. New role of osteopontin in DNA repair and impact on human glioblastoma radiosensitivity. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 63708–63721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.H.; Minai-Tehrani, A.; Shin, J.Y.; Park, S.; Kim, J.E.; Yu, K.N.; Hong, S.H.; Hong,, C.M.; Lee, K.H.; Beck, G.R. Jr.; Cho, M.H. Beclin1-induced autophagy abrogates radioresistance of lung cancer cells by suppressing osteopontin. J. Radiat. Res. 2012, 53, 422–432. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, T.; Ohashi, R.; Cui, R.; Tajima, K.; Yoshioka, M.; Iwakami, S.; Sasaki, S.; Shinohara, A.; Matsukawa, T.; Kobayashi, J.; Inaba, Y.; Takahashi, K. Osteopontin is involved in the development of acquired chemo-resistance of cisplatin in small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2009, 66, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Huang, Y.; Jin, X.; Zhao, W.; Hu, T.; Wu, F.; Huang, J. Osteopontin promotes cancer cell drug resistance, invasion, and lactate production and is associated with poor outcome of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Onco. Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 5933–5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morath, I.; Hartmann, T.N.; Orian-Rousseau, V. CD44: More than a mere stem cell marker. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 81, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietras, A.; Katz, A.M.; Ekström, E.J.; Wee, B.; Halliday, J.J.; Pitter, K.L.; Werbeck, J.L.; Amankulor, N.M.; Huse, J.T.; Holland, E.C. Osteopontin-CD44 signaling in the glioma perivascular niche enhances cancer stem cell phenotypes and promotes aggressive tumor growth. Cell Stem Cell. 2014, 14, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassn Mesrati, M.; Syafruddin, S.E.; Mohtar, M.A.; Syahir, A. CD44: A Multifunctional Mediator of Cancer Progression. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, S.; Karnad, A.; Freeman, J.W. The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: therapeutic implications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Han, H.; Chen, J. CD44 promotes cell proliferation in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 5627–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Vadhan, A.; Chen, P.H.; Lee, Y.L.; Chao, C.Y.; Cheng, K.H.; Chang, Y.C.; Hu, S.C.; Yuan, S.F. CD44 Promotes Lung Cancer Cell Metastasis through ERK-ZEB1 Signaling. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghobi, Z.; Movassaghpour, A.; Talebi, M.; Abdoli Shadbad, M.; Hajiasgharzadeh, K.; Pourvahdani, S.; Baradaran, B. The role of CD44 in cancer chemoresistance: A concise review. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 903, 174147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, J.; Cozzi, P.J.; Hao, J.L.; Beretov, J.; Chang, L.; Duan, W.; Shigdar, S.; Delprado, W.J.; Graham, P.H.; Bucci, J.; Kearsley, J.H.; Li, Y. CD44 variant 6 is associated with prostate cancer metastasis and chemo-/radioresistance. Prostate 2014, 74, 602–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaishi, S.; Okumura, T.; Tu, S.; Wang, S.S.; Shibata, W.; Vigneshwaran, R.; Gordon, S.A.; Shimada, Y.; Wang, T.C. Identification of gastric cancer stem cells using the cell surface marker CD44. Stem Cells 2009, 27, 1006–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiao, Z.; Wong, S.K.; Tin, V.P.; Ho, K.Y.; Wang, J.; Sham, M.H.; Wong, M.P. Lung cancer tumorigenicity and drug resistance are maintained through ALDH(hi)CD44(hi) tumor initiating cells. Oncotarget 2013, 4, 1698–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Casal, R.; Bhattacharya, C.; Ganesh, N.; Bailey, L.; Basse, P.; Gibson, M.; Epperly, M.; Levina, V. Non-small cell lung cancer cells survived ionizing radiation treatment display cancer stem cell and epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotypes. Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones-Orta, M.A.; Avendaño-Vázquez, S.E.; Aparicio-Bautista, D.I.; Coombes, J.D.; Weber, G.F.; Syn, W.K. Osteopontin splice variants and polymorphisms in cancer progression and prognosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2017, 1868, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensembl Database 103. Available online: http://www.ensembl.org/ (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Giacopelli, F.; Marciano, R.; Pistorio, A.; Catarsi, P.; Canini, S.; Karsenty, G.; Ravazzolo, R. Polymorphisms in the osteopontin promoter affect its transcriptional activity. Physiol. Genomics 2004, 20, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, J.; Lorenz, P.; Ibrahim, S.M.; Kundt, G.; Gross, G.; Kunz, M. The functional -443T/C osteopontin promoter polymorphism influences osteopontin gene expression in melanoma cells via binding of c-Myb transcription factor. Mol. Carcinog. 2009, 48, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Chen, X.; Meng, T.; Hao, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G. Genetic polymorphisms in the osteopontin promoter increases the risk of distance metastasis and death in Chinese patients with gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Q.Z.; Zhang, X.F.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, H.L.; Zhou, H.J.; Dai, C.; Sun, H.J.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, W.D.; Ren, N.; Ye, Q.H.; Qin, L.X. Osteopontin promoter polymorphisms at locus -443 significantly affect the metastasis and prognosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Deng, J.; Zhu, X.; Zheng, J.; You, Y.; Li, N.; Wu, H.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y. CD44 rs13347 C>T polymorphism predicts breast cancer risk and prognosis in Chinese populations. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, R105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, M.; Smith, N.J.; Donnelly, P. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 68, 978–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broad Institute of Harvard and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. Available online: https://www.broadinstitute.org/haploview/haploview (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Barrett, J.C.; Fry, B.; Maller, J.; Daly, M.J. Haploview: Analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, S.B.; Schaffner, S.F.; Nguyen, H.; Moore, J.M.; Roy, J.; Blumenstiel, B.; Higgins, J.; DeFelice, M.; Lochner, A.; Faggart, M.; Liu-Cordero, S.N.; Rotimi, C.; Adeyemo, A.; Cooper, R.; Ward, R.; Lander, E.S.; Daly, M. J.; Altshuler, D. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science 2002, 296, 2225–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, F.; Yu, Z.; Li, M.; Chen, S.; Ning, F. OPN Polymorphism Is Related to the Chemotherapy Response and Prognosis in Advanced NSCLC. Int. J. Genomics 2014, 2014, 846142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Li, J. Osteopontin genetic variants are associated with overall survival in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients and bone metastasis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 32, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.Y.; Lin, J.T.; Wu, C.C.; Yu, C.C.; Wu, M.S.; Lee, T.C.; Chen, H.P.; Wu, C.Y. Osteopontin promoter polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to gastric cancer. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 47, e55–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, G.; Wang, H.; Cai, Z.; Ji, H. OPN -443C>T genetic polymorphism and tumor OPN expression are associated with the risk and clinical features of papillary thyroid cancer in a Chinese cohort. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 32, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, Q.; Lu, Y.; Xu, T.; Huang, Y.; Ribas, J.; Ni, X.; Hu, G.; Huang, F.; Zhou, L.; Lu, D. SPP1 promoter polymorphisms and glioma risk in a Chinese Han population. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 55, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, Y.W.; Tu, H.F.; Wang, I.K.; Wu, C.H.; Chang, K.W.; Liu, T.Y.; Kao, S.Y. The implication of osteopontin (OPN) expression and genetic polymorphisms of OPN promoter in oral carcinogenesis. Oral Oncol. 2010, 46, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Nong, L.; Wei, Y.; Qin, S.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, Y. Association of osteopontin polymorphisms with nasopharyngeal carcinoma risk. Hum. Immunol. 2014, 75, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Lu, G.; Pan, G.; Deng, Y.; Liang, J.; Liang, L.; Liu, J.; Tang, Y.; Wei, G. A Case-Control Study of the Association Between the SPP1 Gene SNPs and the Susceptibility to Breast Cancer in Guangxi, China. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Lei, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Dong, W. Associations between the Genetic Polymorphisms of Osteopontin Promoter and Susceptibility to Cancer in Chinese Population: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0135318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Ou, S.; Chen, H. Von Hippel-Lindau gene single nucleotide polymorphism (rs1642742) may be related to the occurrence and metastasis of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Medicine 2021, 100, e27187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Ye, L.; Xu, F.H.; Schneider, M.E.; Ma, X.L.; Du, Y.X.; Zuo, X.B.; Zhou, F.S.; Chen, G.; Xie, X.S.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, H.Z.; Wu, J.F.; Du, W.D. Genetic association of osteopontin (OPN) and its receptor CD44 genes with susceptibility to Chinese gastric cancer patients. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 140, 2143–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Bi, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cao, J.; Lu, Y. The association between osteopontin and survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients: a meta-analysis of 13 cohorts. Onco. Targets Ther. 2015, 8, 3513–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winder, T.; Ning, Y.; Yang, D.; Zhang, W.; Power, D.G.; Bohanes, P.; Gerger, A.; Wilson, P.M.; Lurje, G.; Tang, L.H.; Shah, M.; Lenz, H.J. Germline polymorphisms in genes involved in the CD44 signaling pathway are associated with clinical outcome in localized gastric adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 129, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitaraf, S.M.; Mahmoudian, R.A.; Abbaszadegan, M.; Mohseni Meybodi, A.; Taghehchian, N.; Mansouri, A.; Forghanifard, M.M.; Memar, B.; Gholamin, M. Association of Two CD44 Polymorphisms with Clinical Outcomes of Gastric Cancer Patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2018, 19, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suenaga, M.; Yamada, S.; Fuchs, B.C.; Fujii, T.; Kanda, M.; Tanaka, C.; Kobayashi, D.; Fujiwara, M.; Tanabe, K.K.; Kodera, Y. CD44 single nucleotide polymorphism and isoform switching may predict gastric cancer recurrence. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 112, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tongtawee, T.; Wattanawongdon, W.; Simawaranon, T.; Kaewpitoon, S.; Kaengpenkae, S.; Jintabanditwong, N.; Tangjanyatham, P.; Ratchapol, W.; Kangwantas, K.; Dechsukhum, C.; Leeanansaksiri, W.; Kaewpitoon, N.; Matrakool, L.; Panpimanmas, S. Expression of Cancer Stem Cell Marker CD44 and Its Polymorphisms in Patients with Chronic Gastritis, Precancerous Gastric Lesion, and Gastric Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Multicenter Study in Thailand. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4384823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapcharoen, K.; Sanguansermsri, P.; Yasothornsrikul, S.; Muisuk, K.; Srikummool, M. Gene Combination of CD44 rs187116, CD133 rs2240688, NF-κB1 rs28362491 and GSTM1 Deletion as a Potential Biomarker in Risk Prediction of Breast Cancer in Lower Northern Thailand. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 2493–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Márquez-González, R.M.; Saucedo-Sariñana, A.M.; Barros-Núñez, P.; Gallegos-Arreola, M.P.; Pineda-Razo, T.D.; Marin-Contreras, M.E.; Flores-Martínez, S.E.; Sánchez-Corona, J.; Rosales-Reynoso, M.A. CD44 Genotypes Are Associated with Susceptibility and Tumor Characteristics in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2020, 250, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotz, M.; Herzog, S.A.; Pichler, M.; Smolle, M.; Riedl, J.; Rossmann, C.; Bezan, A.; Stöger, H.; Renner, W.; Berghold, A.; Gerger, A. Cancer Stem Cell Gene Variants in CD44 Predict Outcome in Stage II and Stage III Colon Cancer Patients. Anticancer Res. 2017, 37, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasmickaite, L.; Berge, G.; Bettum, I.J.; Aamdal, S.; Hansson, J.; Bastholt, L.; Øijordsbakken, M.; Boye, K.; Mælandsmo, G.M. Evaluation of serum osteopontin level and gene polymorphism as biomarkers: analyses from the Nordic Adjuvant Interferon alpha Melanoma trial. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2015, 64, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature |

All patients n (%) |

Curative treatment n (%) |

|

| Total | 307 (100) | 145 (100) | |

| Age at diagnosis (median) | < 64 years ≥ 64 years |

146 (48) 161 (52) |

84 (58) 61 (42) |

| Sex | Male Female |

239 (78) 68 (22) |

108 (74) 37 (26) |

| Histology NSCLC | SCC AC NOS |

181 (59) 51 (17) 75 (24) |

86 (59) 23 (16) 36 (25) |

| Clinical stage | I–II III–IV |

30 (10) 277 (90) |

20 (14) 125 (86) |

| Performance status | 0 1 2 |

81 (26) 199 (65) 27 (9) |

57 (39) 88 (61) 0 (0) |

| Smoking status | Never smokers Ever smokers |

19 (6) 288 (94) |

13 (9) 132 (91) |

| Chemotherapy use | No Yes |

91 (30) 216 (70) |

12 (8) 133 (92) |

| Radiation dose | < 60 Gy ≥ 60 Gy |

162 (53) 145 (47) |

- 145 (100) |

| Endpoint | SNP | Genotype | Events/n | p log-rank | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) a | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | |||||||||

| LRFS |

CD44 rs187116 |

GG GA/AA |

42/105 60/202 |

0.084 |

1.0 0.70 (0.47–1.05) |

0.083 |

1.0 0.73 (0.48–1.11) |

0.139 |

|

| MFS |

OPN rs11730582 |

TT/TC CC |

57/231 21/76 |

0.199 |

1.0 1.42 (0.86–2.34) |

0.174 |

1.0 1.63 (0.97–2.74) |

0.064 |

|

| Curative treatment subgroup | |||||||||

| OS |

OPN rs11730582 |

TT/TC CC |

72/112 23/33 |

0.274 |

1.0 1.32 (0.82–2.11) |

0.251 |

1.0 1.74 (1.06–2.86) |

0.029 |

|

| LRFS |

CD44 rs187116 |

GG GA/AA |

22/48 32/97 |

0.039 |

1.0 0.55 (0.32–0.95) |

0.033 |

1.0 0.48 (0.27–0.87) |

0.016 |

|

| MFS |

OPN rs11730582 |

TT TC/CC |

7/44 29/101 |

0.139 |

1.0 1.84 (0.80–4.21) |

0.148 |

1.0 2.21 (0.94–5.16) |

0.068 |

|

|

CD44 rs187116 |

GG GA/AA |

15/48 21/97 |

0.063 |

1.0 0.52 (0.27–1.01) |

0.054 |

1.0 0.53 (0.27–1.07) |

0.076 |

||

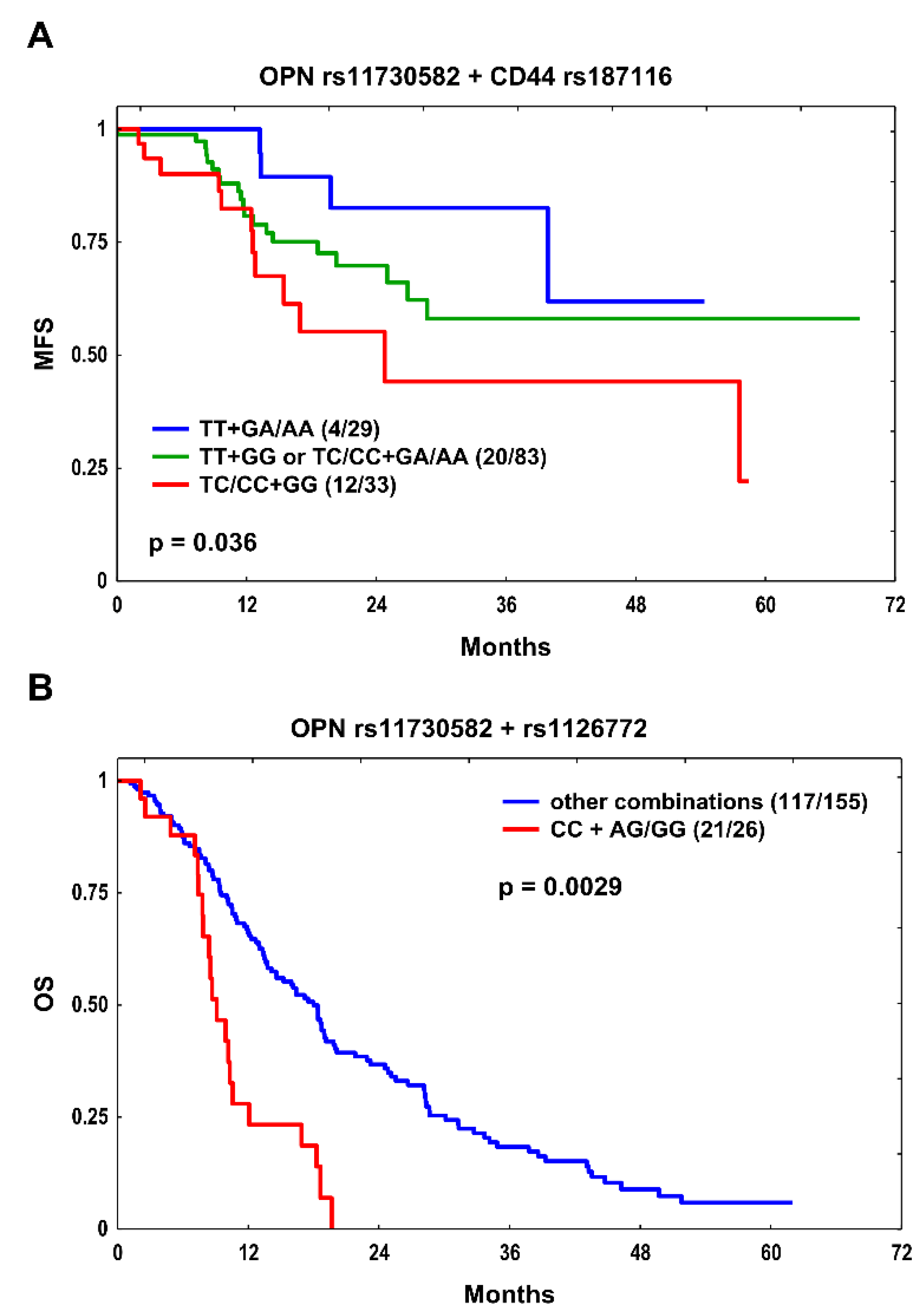

| MFS |

OPN rs11730582 + CD44 rs187116 |

TT + GA/AA TT + GG or TC/CC + GA/AA TC/CC + GG |

4/29 20/83 12/33 |

0.036 |

1.0 2.04 (0.70–5.99) 3.59 (1.15–11.18) |

0.193 0.028 |

1.0 2.36 (0.78–7.12) 4.19 (1.30–13.48) |

0.126 0.016 |

|

| SCC subgroup | |||||||||

|

OS |

OPN rs11730582 |

TT/TC CC |

101/136 37/45 |

0.027 |

1.0 1.60 (1.09–2.34) |

0.015 |

1.0 1.41 (0.94–2.11) |

0.093 |

|

| OPN rs1126772 | AA AG/GG |

92/120 46/61 |

0.034 |

1.0 1.54 (1.07–2.22) |

0.020 |

1.0 1.59 (1.08–2.33) |

0.018 |

||

| OS |

OPN rs11730582 + rs1126772 |

Other combinations CC + AG/GG |

117/155 21/26 |

0.0029 |

1.0 2.82 (1.73–4.60) |

3.3x10-5 |

1.0 2.74 (1.67–4.51 |

7x10-5 |

|

| LRFS |

OPN rs11730582 |

TT/TC CC |

48/136 17/45 |

0.131 |

1.0 1.61 (0.92–2.80) |

0.096 |

1.0 1.48 (0.82–2.66) |

0.192 |

|

| OPN rs1126772 | AA AG/GG |

44/120 21/61 |

0.133 |

1.0 1.57 (0.92–2.67) |

0.095 |

1.0 1.35 (0.75–2.42) |

0.318 |

||

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p |

| Curative treatment subgroup | ||

| OS | ||

|

OPN rs11730582 CC Histology: SCC Ever smoking |

1.66 (1.02–2.70) 2.09 (1.33–3.28) 3.11 (1.13–8.51) |

0.042 0.001 0.027 |

| LRFS | ||

|

CD44 rs187116 GA/AA Histology: SCC Clinical stage III-IV |

0.50 (0.29–0.88) 2.48 (1.40–4.40) 3.34 (1.03–10.84) |

0.016 0.002 0.044 |

| MFS | ||

| OPN rs11730582 + CD44 rs187116 combination: TC/CC + GG | 2.05 (1.02–4.12) | 0.043 |

| SCC subgroup | ||

| OS | ||

|

OPN rs1126772 AG/GG Ever smoking RT dose ≥ 60 Gy |

1.54 (1.06–2.22) 3.42 (1.07–10.86) 0.50 (0.36–0.71) |

0.022 0.037 7.7x10-5 |

|

OPN rs11730582 + rs1126772 combination: CC + AG/GG Ever smoking RT dose ≥ 60 Gy |

2.85 (1.74–4.67) 3.53 (1.11–11.17) 0.50 (0.36–0.72) |

3x10-5 0.032 8.2x10-5 |

| SNP | Haplotype | Number of copies | plog-rank | HR (95%CI) | p | HR (95% CI)a | p |

| Curative treatment subgroup | |||||||

| rs11730582–rs1126772 | C-A | OS | |||||

| 01–2 | 0.227 | 1.01.28 (0.86–1.92) | 0.229 | 1.01.81 (1.18–2.78) | 0.007 | ||

| MFS | |||||||

| 01–2 | 0.077 | 1.01.81 (0.93–3.54) | 0.082 | 1.02.02 (0.99–4.13) | 0.053 | ||

| SCC subgroup | |||||||

| rs11730582–rs1126772 | T-A | OS | |||||

| 01–2 | 0.026 | 1.00.62 (0.43–0.91) | 0.014 | 1.00.71 (0.47–1.06) | 0.098 | ||

| C-G | OS | ||||||

| 01–2 | 0.033 | 1.01.55 (1.08–2.24) | 0.019 | 1.01.61 (1.10–2.38) | 0.016 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).